Abstract

Venom as a form of chemical prey capture is a key innovation that has underpinned the explosive radiation of the advanced snakes (Caenophidia). Small venom proteins are often rich in disulfide bonds thus facilitating stable molecular scaffolds that present key functional residues on the protein surface. New toxin types are initially developed through the venom gland over-expression of normal body proteins, their subsequent gene duplication and diversification that leads to neofunctionalisation as random mutations modify their structure and function. This process has led to preferentially selected (privileged) cysteine-rich scaffolds that enable the snake to build arrays of toxins many of which may lead to therapeutic products and research tools. This review focuses on cysteine-rich small proteins and peptides found in snake venoms spanning natriuretic peptides to phospholipase enzymes, while highlighting their three-dimensional structures and biological functions as well as their potential as therapeutic agents or research tools.

Keywords: Snake toxins, Venom peptides, Privileged frameworks, Cysteine bridges, Molecular scaffolds, Structure-activity relationships, Disulfide

Introduction

While venom in reptiles had a single, early evolution [1, 2], it is at the base of the advanced snakes that it truly became a key evolutionary innovation that underpinned the explosive radiation of this lineage [3]. Snake venom is a complex mixture of enzymes, proteins and peptides. Many of these toxin families have stable molecular scaffolds (Table 1). The toxins within the venom are a result of gene duplication of proteins or peptides typically used elsewhere in the body, with the copy being selectively expressed in the venom gland [4]. These genes are often amplified into multi-gene families with diverse neofunctionalisation followed by the deletion or conversion of some copies to non-functional or pseudogenes [5].

Table 1.

Primary structures, disulfide bridge arrangements and representative 3D structures of small snake toxins

The disulfide bridge arrangements are shown as black lines and the dotted black line represents the fifth disulfide observed in long chain neurotoxins. The number of residues located between the cysteines are indicated by numbers

While the stable, disulfide-rich molecular scaffold is preserved among the newly emergent multi-gene family, neofunctionalisation is facilitated by mutation of key residues or domains on the molecular surface. A well-studied example comprises the three-finger toxins that are found in elapids as well as various non-front-fanged lineages [6–8]. The members of this multi-gene family all have a similar pattern of protein folding consisting of three loops extending from a central hydrophobic core containing four ubiquitously conserved disulfide bonds, of the five bonds present in the plesiotypic form. Despite the similar scaffold, the subtle differences in sequence and conformation of the loops and C-terminus of this family results in a broad range of biological effects when binding to its various receptors [7].

Venom proteins and peptides target physiological processes at sites accessible by the blood-stream, inducing a myriad of toxic effects upon prey, ranging from precisely targeted toxicity to modulation of blood chemistry, the cardiac system, muscles, or neurological systems through cell death or necrosis. Structure-function investigations have elucidated how different functions are exerted by toxins with similar folds and how similar functions may be shared by structurally different toxins thus, providing tools to either determine the molecular pharmacology of different toxins or to provide lead molecules to develop therapeutic agents.

Snakes and medicine have origins in the sixth century BC with the god of medicine, Asclepius, represented by a wooden staff entwined by a snake while the antidote for snake bite and other diseases from the first century included not only more traditional remedies such as plant extracts, including opium, but also viper venoms [9]. However, the true potential of snake toxins as therapeutic agents was only realised in the last half of the 20th century when a bradykinin-potentiating peptide isolated from the Brazilian viper Bothrops jararaca was developed using a combination of structure-activity relationships, molecular design and intuition, into the small molecule ACE-inhibitor drug captopril® to treat renovascular hypertension [10]. In addition to having potential as drug leads, snake toxins have also been utilised as research tools. For example, the curaremimetic neurotoxins from the three-finger toxin family have been instrumental in the discovery, isolation, distribution and characterisation of the muscarinic and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors located at the neuromuscular junction [11].

In this review, we look at the array of small toxins identified in snake venom that range from the natriuretic peptides to the phospholipase A2 enzymes. We highlight the overall peptide and polypeptide structure and conformation (Table 1), homology to other vertebrate and mammalian peptides, the structure-function relationships between the toxin and target protein with their ensuing pharmacological effects, and whether the toxin has been further processed as a therapeutic agent or research tool.

Privileged frameworks: structure and function

Natriuretic peptides

Natriuretic peptides are synthesised as preprohormones with further processing occurring in the endoplasmic reticulum and proteolytic cleavage of the propeptide by serine proteases to produce the mature peptide [12, 13]. The mammalian natriuretic peptides (ANP, BNP and CNP) are a family of structurally similar hormones/paracrine factors primarily involved in natriuresis, diuresis and vasorelaxation as a result of cardiac wall stretch. These three forms differ largely on the relative presence (ANP and BNP) or absence (CNP) of a C-terminal tail, with the cysteine-linked loop conserved (Table 2). Recent research has identified the effects of these peptides are widespread and complex. They include regulation of blood volume, blood pressure, ventricular hypertrophy, pulmonary hypertension, fat metabolism and long bone growth in response to a number of pathological conditions [14]. A recent study showed BNP and NPR-A receptors are expressed in rat dorsal root ganglion and upregulated after peripheral tissue inflammation. Activation of the signalling pathway in nociceptive afferent neurons inhibits inflammatory pain thereby suggesting BNP as a potential drug in pain treatment [15].

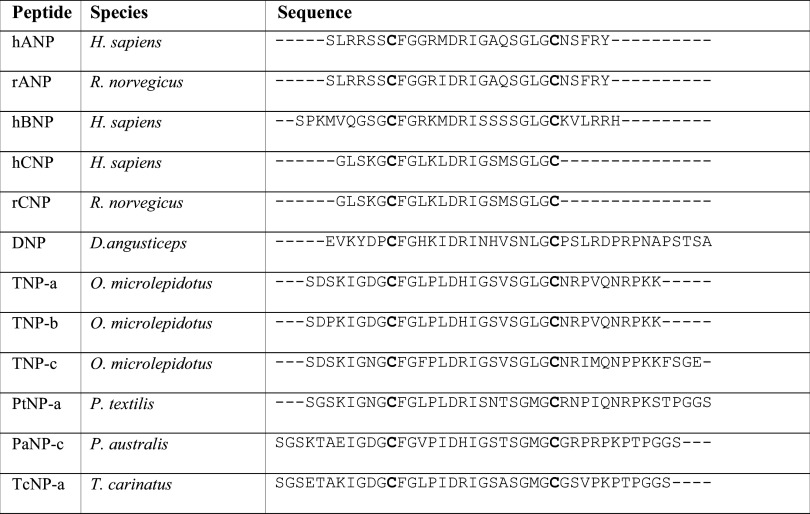

Table 2.

Natriuretic peptide sequence alignment of mammalian and snake species

Natriuretic peptides bind to three receptors in mammals, NPR-A, NPR-B and NPR-C. Both NPR-A and NPR-B are transmembrane homodimers with the intra-cellular domain consisting of a protein kinase-like domain and a guanylate cyclase domain [16]. These two receptors mediate the majority of known biological effects by catalysing the synthesis of the intra-cellular signalling molecule cGMP. All three mammalian natriuretic peptides contain the conserved sequence CFGXXXDRIXXXXGLGC and these form a 17 amino acid ring structure via a disulfide bridge of the flanking cysteine residues [17] (Table 1). This receptor selectivity is modulated by extensive interaction between natriuretic peptide and the receptor with residues Phe8, Arg14 and the C-terminal sequence of ANP and Phe7, Arg13 and Met17 of CNP important for binding to NPR-A and NPR-C, respectively [18, 19].

Natriuretic peptides were first identified as a toxin in snake venom in D. angusticeps [20]. The toxin is structurally and functionally homologous to mammalian natriuretic peptides and produces a hypotensive effect designed to aid in incapacitation of prey [21]. D. angusticeps natriuretic peptide (DNP) is a 38-residue structure that relaxes rat aortic strips precontracted with KCl and stimulated cGMP in cultured aortic myocytes and bovine aortic endothelial cells [20] with potent natriuretic and diuretic activity [22, 23]. Natriuretic peptides have been subsequently isolated from a wide range of advanced snakes including the front-fanged Elapidae and Viperidae families and also non-front genera Philodryas and Rhabdophis. While a variety of N- or C-terminal tailed and tail-less forms have been sequenced from various snake venoms, all form a tight monophyletic clade within non-venom CNP precursors [24], thus revealing that the forms possessing a C-terminal tail have secondarily evolved this tail.

To illustrate the functional diversity of snake venom natriuretic peptides, despite only subtle differences in sequences of the three natriuretic peptides TNP-a, TNP-b and TNP-c from Oxyuranus microlepidotus, a significant difference in bioactivity was noted [21]. Only TNP-c was equipotent to ANP or DNP in relaxing precontracted rat aortic rings or in binding to over-expressed NPR-A receptors. Similarly, two peptides from other venoms (PaNP-c from Pseudechis australis and PtNP-a from P. textilis) also showed quite variable activity despite displaying obvious sequence similarity. While both PaNP-c and PtNP-a inhibited angiotensin converting enzyme conversion in a dose-dependent manner, only recombinant PtNP-a showed a dose-dependent stimulation of cGMP production [25].

Both human ANP and BNP have been investigated as candidates for treatment of congestive heart failure resulting from myocardial infarction and/or hypertension [26, 27]. Carperitide, which is a synthetic form of ANP [28], was approved for use in Japan in 1995 and showed improvement in 82 % of patients with acute heart failure but adverse effects included low blood pressure and renal function disturbance [29]. Nesiritide is a recombinant form of BNP and was found to improve left ventricular function by vasodilation and natriuretic action [26], as well as improving dyspnoea and fatigue [27] in patients with congestive heart failure.

Sarafotoxins

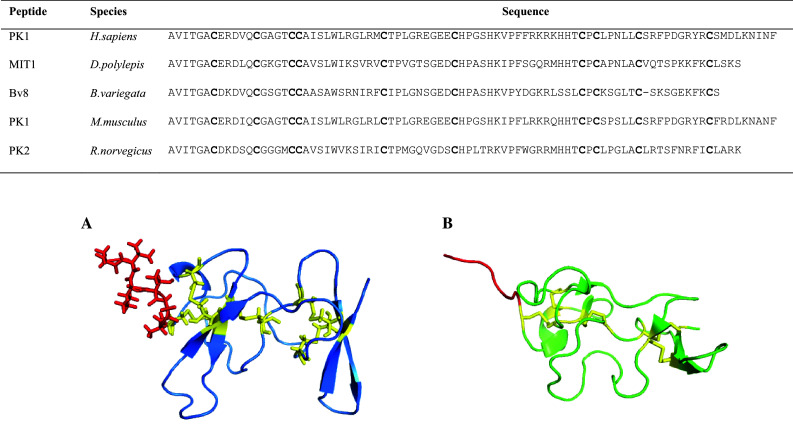

Sarafotoxins are derived from the vasoconstrictive endothelin family (ET). These hormonal (autocrine or paracrine) peptides are involved in modulation of the contraction of cardiac and smooth muscle in different tissues in vertebrates [30, 31]. The endothelin family consists of four isopeptides containing 21 amino acids (Table 1; Fig. 1) mainly synthesised by endothelial cells: ET-1, ET-2 and ET-3 in human, and vasoactive intestinal contractor (VIC) in rodents [32, 33]. Two G-protein-coupled endothelin receptors, endothelin-A (ETA) and endothelin-B (ETB), have been cloned and characterised [34, 35]. Activation of ETA by ET-1 results in vasoconstriction and cell proliferation. ETB receptors are expressed on endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells. These receptors cause vasodilation, inhibit cell growth and vasoconstriction, and mediate the clearance of ET-1 from circulation [36]. Additionally, novel bioactive 31-amino acid ETs have been described that are also vasoconstrictors though in a different manner to ET-1, -2 and -3 [37].

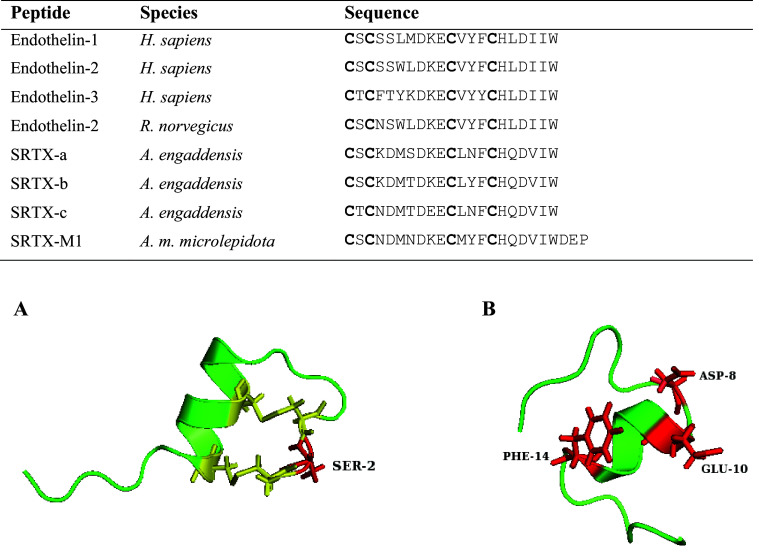

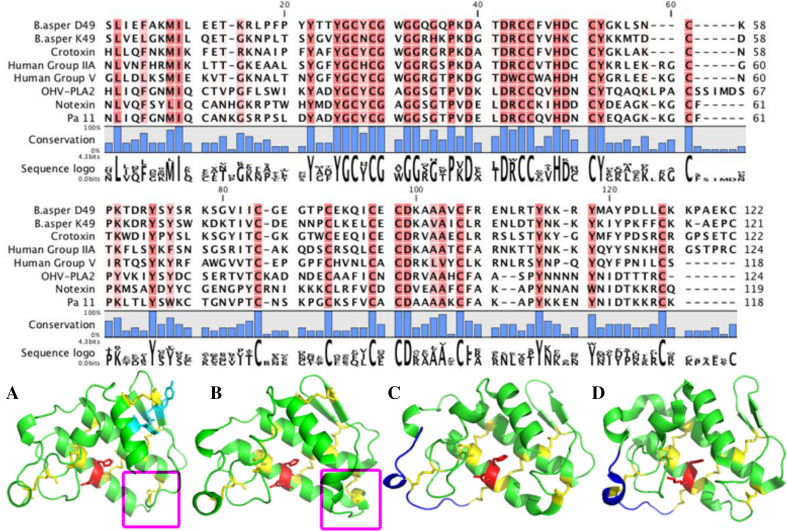

Fig. 1.

Multiple sequence alignment and three-dimensional structures of sarafotoxin and endothelin peptides. Conserved cysteines are shown in bold in the sequence alignment. Accession numbers are as follows: P05305, P20800, P14138, P23943, P13208, Q6RY98. A The NMR structure of SRTX-b from Atractaspis engaddensis (1SRB) showing the Ser2 residue important for vasoconstriction activity. B The NMR structure of human endothelin-1 (1V6R) showing Asp8, Glu10 and Phe14 important for biological activity. Functional residues are highlighted in red and disulfide bridges are depicted in yellow

Sarafotoxins (SRTXs) are toxins unique to the venoms of the enigmatic Atractaspis genus (stiletto snakes). The first SRTXs, SRTX-a, b and c, were isolated from the potent venom of Atractaspis engaddensis [38] and comprised of 21 amino acids stabilised by two conserved disulfide bonds [39, 40]. Analysis of the biological effects of A. engaddensis crude venom on heart and nerve-muscle preparations showed a predominant cardiotoxic effect, but no pre- or post-synaptic neurotoxicity [41]. Additionally, SRTXs showed various degrees of vasoconstriction effects on isolated smooth muscle systems of rabbit aorta, rat uterus and guinea pig ileum [42–44].

As with long-form endogenous ET peptides, longer SRTX isoforms were identified in A. m. microlepidota venom that contained three additional residues at the C-terminus [45]. A recent study showed long sarafotoxins are highly toxic in mice but the C-terminus extension induced decreased affinity between the long SRTX and cloned ETA/ETB receptors indicating a new receptor subtype is present or reduced affinity at the receptor sites does not affect the signalling cascade [46].

NMR resolution and molecular modelling of ET-1 and SRTX-b in solution show that the peptides adopt a disulfide-stabilised α-helical motif characterised by an extended structure of the first three or four amino acids; a β-turn from positions +5 to +8; an α-helical conformation in the sequence region Lys9-Cys15, and, absence of conformation in the C-terminus [47, 48] (Fig. 1). A sequence modification study of SRTX-b confirmed the serine at position +2 is important for vasoconstriction activity with the synthetic [Thr2]SRTX-b showing similar toxicity but reduced vasoconstriction efficacy [49] (Fig. 1). Chemical mutagenesis studies on ETs have determined the terminal amino and carboxy groups and residues Asp8, Glu10 and Phe14 are important for biological activity and efficacy of binding to the ET receptor [50] (Fig. 1). Sarafotoxins labelled with iodine demonstrated high affinity and specificity for rat atrial and brain membranes in a rapid and reversible manner. Elevated levels of ET-1 have been associated with a number of diseases including hypertension, asthma, artherosclerosis, myocardial arrhythmias and ischaemia, and renal failure as well as a number of cancers including prostate, ovarian, colorectal, bladder, breast and lung carcinomas [36]. Thus sarafotoxins may provide a source of molecular probes in identifying processes in such diseases and structure-function relationship studies between receptor subtypes and SRTX/ET ligands may provide a source of antagonist peptides.

β-Defensin peptides

Human and mammalian β-defensins are produced in epithelial cells and immune cells including monocytes, macrophages and monocyte-derived dendritic cells and are involved in the innate immune response as anti-microbials and chemokines [51]. These highly cationic and amphipathic peptides disrupt bacterial membranes through electrostatic interaction with the negatively charged bacterial membrane, resulting in loss of membrane integrity possibly by insertion of the peptide into the phospholipid layer when the critical peptide/lipid ratio is achieved [52, 53].

The majority of the research into snake venom β-defensin peptides has concentrated on the crotamine and myotoxin-α peptides from Crotalus (rattlesnake) venoms [54, 55]. The β-defensin toxin contains 42–43 residues that are stabilised by three disulfide bonds and show high sequence homology plus similar chemical and biological properties between members (Table 1; Fig. 2) [56]. Crotamine was originally isolated from the venom of the Argentinian rattlesnake Crotalus durissus terrificus [57] and is a extremely basic toxin shown to exist in two conformation states due to cis-trans isomerisation at Pro20 [58].

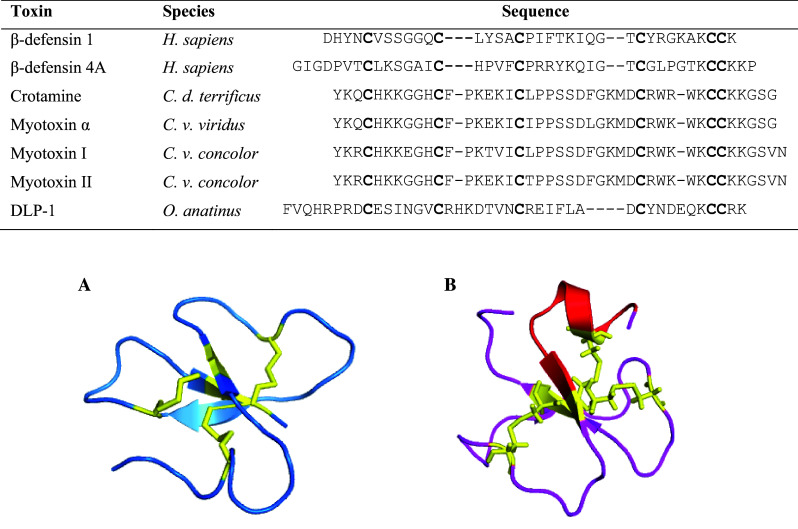

Fig. 2.

Multiple sequence alignment and three-dimensional structures of β-defensin peptides. Conserved cysteines are shown in bold in the sequence alignment. Accession numbers are as follows: P60022, O15263, P01475, P01476, P12028, P12029, P82172. A The NMR structure of human β-Defensin 1 (1KJ5). B The NMR structure of crotamine (1H50) showing the region of cationic residues (red) responsible for anti-microbial activity. Disulfide bridges are depicted in yellow

Initially, crotamine was shown to induce spastic paralysis of the hind limbs of mice, rats, rabbits and dogs. Recent studies have shown the action may not involve Na+ channels [55, 59] but may be similar in mechanism of action to myotoxin α [60]. Myotoxin α, isolated from the prairie rattlesnake, induces local skeletal muscle contracture followed by myofibril degeneration and a vacuolisation pattern similar to crotamine [61–63]. Both crotamine and myotoxin α cause strong Ca2+ release from heavy sarcoplasmic reticulum through the ryanodine receptor [64] and in the case of myotoxin α, the mechanism may also involve the 30 kDa protein [65].

NMR spectroscopy has demonstrated that crotamine structure is composed of a short N-terminal α-helix and a small anti-parallel triple-stranded β-sheet arranged in a αβ1β2β3 arrangement (Table 1) [66]. The disulfide bridge arrangement and characteristic twisted anti-parallel β-sheet fold conformation is similar to the mammalian and human antibacterial β-defensin family, which may be used to group these proteins as a superfamily (Fig. 2). The cysteine residues are paired in a 1–5, 2–4, 3–6 arrangement positioned in the centre of the molecule resulting in a hydrophobic core and compact fold [67]. Whereas the disulfide bonds are conserved, the remaining amino acid sequences show less than 30 % homology between family members [68].

Crotamine also has potent analgesic activity that involves both central and peripheral nervous system mechanisms [69]. Furthermore, the toxin shows a unique penetrating property by localising and concentrating in the cytoplasm and nucleus of different cell types and demonstrated its potential as a biotechnology tool by targeting delivery of plasmid DNA into actively proliferating cells in vivo and in vitro [70, 71]. Further analysis identified the penetration process as endocytosis with accumulation of crotamine in acidic endosomal/lysosomal vesicles of CHO-K1 cells and causing lysosome lysis at higher concentrations, leading to cell death [72].

Kunitz-type serine protease inhibitors

Serine proteases are ubiquitous in animals, plants and micro-organisms. The first X-ray structure of a kunitz-type serine protease inhibitor was that of basic pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (BPTI) which is a small, soluble, stable peptide of 58 amino acids isolated from bovine pancreas with three conserved, characteristic disulfide bridges (Table 1; Fig. 3) [73, 74]. Kunitz inhibitors bind antagonistically to the serine protease active site by an exposed binding loop in a substrate-like manner known as the ‘standard’ mechanism [75]. The mechanism involves the peptide bond of the reactive site of the inhibitor interacting with the active site of the serine peptidase [74, 76]. Schechter and Berger identified six residues (P3, P2, P1, P1′, P2′, P3′) that were involved with the interaction at the active site that mimics an ideal protease substrate [77] with the conformation of the peptide containing the reactive site described as canonical [78]. A positively charged residue (Arg or Lys) at the P1 position can be indicative of trypsin inhibition while the presence of a hydrophobic residue (Leu, Phe or Tyr) at this position is linked to chymotrypsin inhibition [74].

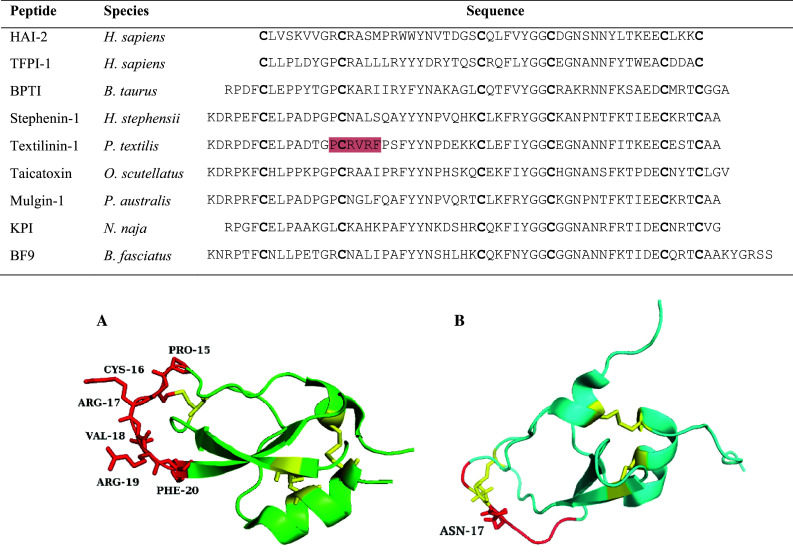

Fig. 3.

Kunitz-type serine protease inhibitor sequence alignment. The residues highlighted in red on the textilinin-1 sequence are the amino acids involved in the anatagonistic interaction with the protease active site. Conserved cysteines are shown in bold. Accession numbers are as follows: O43291, P10646, P00974, B5KF94, Q90WA1, B7S4N9, Q6ITC1, P19859, B2KTG1. 3D structures are shown for A Textilinin-1 (3BYB) and B chymotrypsin inhibitor from Bungarus fasciatus (1JC6). Textilinin-1 shows the P3–P3′ residues in red with Arg17 (P1′) typical for trypsin inhibition. The chymotrypsin inhibitor denotes the P3–P3′ residues in red but with an asparagine residue at P1′ instead of the typical hydrophobic residues of Leu, Phe and Tyr. Disulfide bridges are depicted in yellow

Kunitz-type serine protease inhibitors have been identified in the venom of a wide range of advanced snake species, particularly from the Elapidae and Viperidae families, with the majority tested thus far having non-specific antitrypsin and antichymotrypsin activity. The first kunitz-type inhibitor was isolated from the venom of Daboia russelii and was shown to inhibit kallikrein, trypsin and plasmin [79]. A novel chymotrypsin inhibitor from Bungarus fasciatus contained asparagine as the P1 residue instead of the traditional hydrophobic residue [80] (Fig. 3). A potent trypsin inhibitor isolated from the Naja naja venom had the characteristic six cysteine residues and 42 % homology with BPTI. The strong trypsin inhibition may be attributed to a charged lysine residue at the P3′ position, instead of a hydrophobic isoleucine as seen in BPTI [81] or an aromatic phenylalanine observed in the majority of Australian elapids [82]. In addition, the enzyme inhibitor from P. textilis affects blood coagulation through plasmin inhibition [83] while the protease inhibitor type from D. angusticeps does not interact with enzymes but instead binds to L-type Ca2+ channels [84].

A comprehensive cDNA study of eleven Australian elapids identified kunitz-type inhibitors in all species and multiple isoforms in most species. Sequence analysis showed homology in the cysteine residues and the C-terminus but a high degree of variability within the canonical loop region (P3–P3′). Further phylogenetic analysis clustered the Australian elapids as evolutionary distinct from the kunitz serine inhibitors previously characterised from vipers, colubrids and non-Australian elapids [82].

Textilinin-1 isolated from the venom of the P. textilis is a kunitz-type inhibitor showing a single stage, reversible mechanism specific for the serine proteases plasmin and trypsin [83]. The inhibitor contains 59 residues and demonstrates a fold similar to BPTI that is stabilised by three disulfide bonds (Table 1; Fig. 3) [85]. Determination of the crystal structure from recombinant textilinin-1 showed the molecule differs to aprotinin at the critical residues of P1 and P1′ with textilinin-1 containing arginine and valine at these sites, while aprotinin contains lysine and alanine, respectively [85]. Aprotinin potently inhibits a number of enzymes including plasmin, trypsin and kallikrein which led to its development as an anti-fibrinolytic agent to reduce blood loss in cardiac surgery [86]. However, in 2007 marketing was suspended due to a study finding the use of aprotinin increased the risk of heart attack, stroke and renal failure [87]. As textilinin-1 is more specific than aprotinin for plasmin, exhibits a reversible mechanism and reduces bleeding in a murine bleeding model by 60 % [88], it remains a lead candidate as a replacement anti-fibrinolytic agent to aprotinin [89].

Kunitz-type serine protease inhibitors interact with other toxins to form complexes. β-Bungarotoxin from Bungarus multicinctus is a neurotoxic covalently linked heterodimer consisting of a Group I PLA2 enzyme (Chain A) and a kunitz-type serine protease inhibitor (Chain B) [90]. The complex disrupts neurotransmission by binding to the presynaptic site of the neuromuscular junction while the kunitz subunit directs the interaction by binding with high affinity to a specific subclass of voltage-sensitive potassium channels [91]. Taicotoxin is an oligomeric complex isolated from Oxyuranus scutellatus venom and consists of an α-neurotoxin-like peptide; a neurotoxic PLA2 and a protease inhibitor. The complex blocks Ca2+ channels, however, the activity is lost when the protease inhibitor is removed from the complex [92]. Another such complex is MitTx, a heteromeric complex made up of a kunitz peptide and a PLA2 which acts as a powerful agonist on acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs), inducing excruciating pain [93].

Waprins

The relatively recent discovery of nawaprin from the venom of Naja nigricollis is evidence that novel protein families continue to be discovered from snake venoms [94]. Nawaprin is structurally similar to whey acidic proteins (WAPs) and hence, this snake toxin family has been termed waprins. Omwaprin is a 50-amino acid cationic waprin recently isolated from O. microlepidotus and shows 37–41 % sequence similarity to nawaprin, elafin and SLPI [95]. Functional analysis of the recombinant form displayed no anti-proteinase effect but showed selective and dose-dependent antibacterial activity against Gram-positive bacteria; omwaprin had no effect on eukaryotic membranes as demonstrated by the lack of activity on human erythrocytes [95]. Reduction and alkylation of the cysteine residues and deletion mutagenesis of the N-terminal region indicated the disulfide bridges and the cationic N-terminus are important for antibacterial function. Scanning electron microscopy indicated that the antibacterial mechanism is via membrane disruption [95] (Fig. 4).

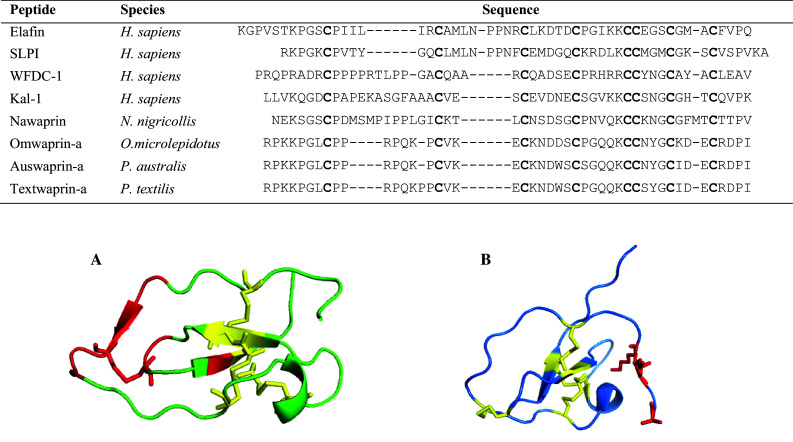

Fig. 4.

Waprin sequence alignment and X-ray structures of A human elafin and B omwaprin. Conserved cysteines are shown in bold. Accession numbers are as follows: P11957, P03973, Q9HC57, P23352, P60589, P83952, B5G6G9, B5L5P9. A Human elafin (1FLE) showing Leu20 (P5) to Leu26 (P2′) of the primary binding loop and Ser47, Cys49 and Ala52 of the adjacent hairpin loop that are in contact with the enzyme. B Omwaprin (3NGG) 3D figure highlighting the cationic N-terminus and disulfides important for antibacterial action. Disulfide bridges are depicted in yellow

Whey acidic proteins are the major whey protein found in the milk of a range of animals with the mouse type being the prototypic member of the family [96, 97]. The WAP domain consists of 40-50 amino acids with eight conserved cysteine residues forming four disulfide bonds (Table 1; Fig. 4) [98] and the inter-cysteine residues show great diversity resulting in divergent functions among the protein family. Members of this family are termed WDFC (whey/four disulfide core) proteins with the WDFC domain present in numerous proteins; not all of which are present in milk [99]. The crystal structure of the WAP elafin complexed with porcine pancreatic elastase shows the seven residues Leu20 (P5) to Leu26 (P2′) (contains the second cysteine) of the primary binding loop and Ser48, Cys49 and Ala52 of the adjacent hairpin loop are in contact with the enzyme and shows the scissile peptide bond in the primary binding site to be intact [100] (Fig. 4). Site-directed mutagenesis of secretory leucocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) determined the C-terminal WFDC domain was responsible for the anti-protease activity of trypsin, chymotrypsin and leucocyte elastase and indicated that residue Leu72 binds to the S1 site of the enzyme [101].

The spacing of the cysteine residues in elafin and SLPI is identical and are important for anti-proteinase activity; variation from this may be responsible for the lack of anti-proteinase activity observed in other mammalian WFDC proteins [102]. Therapeutically, in addition to anti-microbial roles, both elafin and SLPI inhibit HIV infection and are possible anti-infectives of the viral disease [103]. Both SLPI and elafin also show potential as aerosol drugs in reducing the chronic protease-induced inflammation associated with lung diseases such as cystic fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [104].

Three-finger toxins

The Ly-6/uPAR peptide superfamily is structurally characterised by three β-stranded loops extending from a small, globular, hydrophobic core stabilised by 10 highly conserved cysteine residues [105, 106]. Included in this diverse assemblage are the glycosylphosphatidyl inositol (GPI) anchored LYNX neuropeptides that bind to α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) in the central nervous system and have been shown in vitro and in vivo to regulate nAChR activity and prevent excess excitation [107].

The homologous three-finger toxins (3FTxs) found in the venoms of elapids, hydrophiids and colubrids typically contain three distinct β-stranded loops extending from a disulfide-rich hydrophobic core. The ancestral 10-cysteine pattern is preserved in the basal-type α-neurotoxins found in the venoms of non-front-fanged snakes and still secreted in low-levels in the front-fanged elapid snakes (Table 1) [6, 106]. Significantly, the more potent elapid α-neurotoxins have lost the second and third ancestral cysteines. The deletion of these two cysteines also led to an explosive radiation of this toxin class, with the subsequent flourishing of neurotoxic, haemotoxic and cytotoxic pharmacological activities (Table 3). The subtle differences in primary structure and conformation of the three-finger toxins are also reflected in the diversity of biological activities demonstrated by the toxins. Despite the extremely large scope and complexity of the snake 3FTx family [6, 7], only the neurotoxins and cytotoxins/cardiotoxins have been well-characterised and consequently only they will be reviewed here.

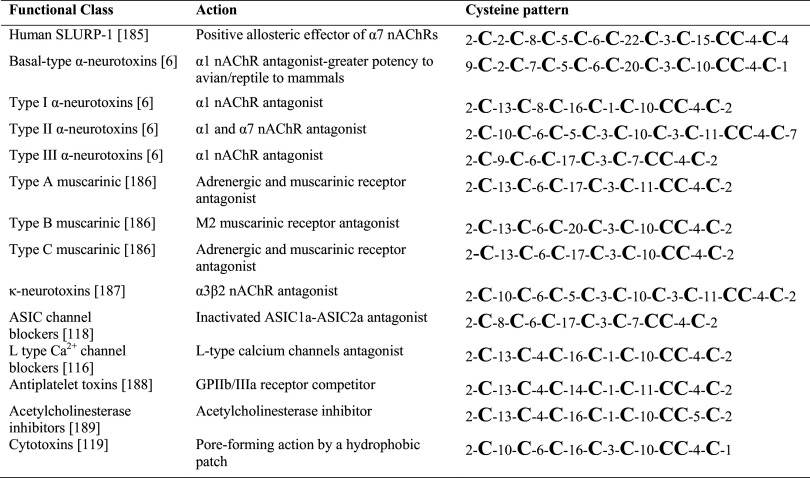

Table 3.

Bioactivity and cysteine spacing of 3ftx types

Neurotoxic three-finger toxins

The separation of the venom of B. multicinctus using zone electrophoresis on starch to investigate the ‘curare like action of the venom’ was one of the earliest identifications of three-finger toxins (3FTxs) in snake venom [108]. The main fraction, designated α-bungarotoxin, was shown to irreversibly block neuromuscular transmission via the acetylcholine receptor at the motor end plate [108]. Analysis of cobratoxin from the venom of Naja atra demonstrated the potent neuromuscular blocking properties of the toxin was reliant upon the integrity of the disulfide bonds, and hence the conformation of the molecule [109]. Both the Type I and Type II α-neurotoxins have proven invaluable in the discovery, purification and ligand interaction characterisation of the neuromuscular nAChRs [11].

The basal activity of the neurotoxic 3FTxs is binding at the α1 nAChR, with relative potency reflective of prey-specificity, and hence most plesiotypic forms are much more potent against reptiles and avians than mammals [106, 110, 111]. Secondary to the evolution of the intricate venom system of the elapid snakes, characterised by a high-pressure delivery system linked to syringe-like hollow fangs, the second and third ancestral cysteine residues were lost, with a dramatic increase of the α-neurotoxicity by the Type I α-neurotoxins (also known as the short-chain α -neurotoxins) [6, 112] (Fig. 5). Subsequent to the loss of the second and third ancestral cysteines, the α-neurotoxicity specificity was modified in one derived clade [the Type II α-neurotoxins (also known as the long-chain neurotoxin)] to have two new cysteines stabilising loop-2 and with the derived activity of an additional target; the α7 nAChRs [113].

Fig. 5.

Multiple sequence alignment and three-dimensional structures of 3FTxs. Alignment of snake venom short chain (Aa-c, Taipan-1, erabutoxin a, mambalgin-2), long chain (Bungarotoxin a, acanthopin d), muscarinic toxins (MT 7), cardiotoxins (CTX V, Toxin gamma), β-cardiotoxins (β-cardiotoxin) and mammalian 3FTxs (Lynx 1, Slurp 1) using CLC Main Workbench 6. Highly conserved residues are highlighted in green while semi-conserved residues are a lighter green. The consensus sequence is shown above the multiple sequence alignment with disulfide connectivity shown in solid red lines. The fifth disulfide observed in long chain 3FTxs is linked by a dotted red line. Ribbon models A–D represent the short-chain neurotoxin erabutoxin-a (1QKE-purple ribbon), mambalgin-2 (2MFA-orange ribbon); long-chain neurotoxin alpha-bungarotoxin (1KFH-blue ribbon); cardiotoxin analogue V (CTX V) (1CHV-green ribbon); and the water-soluble domain of human LYNX1 (2L03-light blue ribbon), respectively. The conserved disulfide bridges are shown in yellow and functional residues are shown in red; 1QKE-K27, W29, D31, F32, R33, K47; 1KFH- A7, S9, I11, R36, K38, V39, V40; 1CHV- M26, K44. The added methionine of water-soluble LYNX-1 lacking the GPI anchor is shown in black

In addition to potentiating neurotoxicity, the structural constraints brought about by the deletion of the second and third ancestral cysteines freed up the scaffold for the derivation of new neurotoxins with activities such as κ-neurotoxins targeting neuronal nicotinic receptors [114]; adrenergic/muscarinic neurotoxins targeting a wide array of adrenergic and muscarinic nAChR subtypes [115]; blockage of L-type calcium channels; and inhibition of acetylcholinesterase [116, 117]. Notably, 3FTxs known as mambalgins, isolated from the venom of Dendroaspis polylepis, show potential therapeutic value as an analgesic by blocking ASIC channels. The peptides target both primary nociceptors and central neurons through different ASIC subtypes and hence, are not only potential analgesics but are excellent tools for understanding pain [118].

Cytotoxins

The second largest group of 3FTxs are the cytotoxins (aka cardiotoxins). Structurally, cytotoxins are similar to short-chain neurotoxins; they contain four of the ancestral disulfide bonds; contain 59–62 residues and are unusually highly conserved, with approximately 90 % sequence homology [119, 120] (Fig. 5). The non-specific pore-forming action, guided by a hydrophobic patch that facilitates integration into the lipid bilayer, has resulted in documentation of a wide array of activities including effects resulting from depolarisation of cardiomyocytes and nerve cells; depolarisation and contracture of smooth and skeletal muscle; lysis of erythrocytes, necrotic cell death in foetal rat cardiomyocytes and apoptosis in cortical neurones [121–124]. Comparison of the solution structures of the potent cytotoxin CTX V to other cytotoxin isoforms from N. atra venom identified the amino acids Met26 and Lys44 are important for the lethal activity of cytotoxins [125] (Fig. 5).

While, the cardiomyocyte target or receptor involved in the cytotoxins interaction is yet to be identified, it is apparent that the cytotoxic effects are the result of the toxin damaging cells by interacting with anionic lipids on the cell membrane resulting in pore formation and increased membrane permeability [126–128].

Interestingly, an investigation using H9C2 cardiomyoblast cells and rat cardiomyocytes showed CTX A3 from the Taiwan cobra binds to the sulphatide 3′-sulphated β1-d-galactosylceramide in the plasma membrane resulting in pore formation and internalisation and disruption of the mitochondrial network [129, 130].

A divergent cytotoxin subclade called β-cardiotoxins have recently been isolated from Ophiophagus hannah venom [131]. These peptides induce a dose-dependent decrease in heart rate both in vivo and ex vivo by blocking β-adrenergic receptors. Compared to cytotoxins, they show approximately 55 % sequence homology and differ structurally within the loop regions. Adult clinical trials in the 1990s showed a reduction in mortality risk of 30–35 % using β-adrenergic receptor blockers as standard therapy for chronic heart failure instead of β-agonists [132]. β-receptor signalling research on isolated cardiomyocytes has indicated that the β1-receptor regulates cardiotoxicity (pro-apoptotic signalling) and β2-receptors are primarily involved in cardioprotection (anti-apoptotic signalling). However, research utilising β1- and β2-receptor knockout mice has shown the role of each β-adrenergic receptor subtype in regulating cardiotoxicity and cardioprotection is complex and variable, depending on the particular stressors involved and whether the stressors are acute or chronic [133]. Hence, the recently discovered β-cardiotoxins show potential as research tools for β-adrenergic receptors and as therapeutics for cardiovascular disease.

Avit proteins

A small, non-toxic protein isolated from D. polylepis just over 30 years ago was initially designated as protein A and was later found to potently contract gastrointestinal (GI) smooth muscle and produce hyperalgesia [134]. It was renamed MIT1 (mamba intestinal toxin 1) with the structure containing 80 residues stabilised by five disulfide bonds and resembles a close structural homolog to pig colipase [135] (Table 1; Fig. 6). This family of proteins are known as prokineticins (PK) or AVIT proteins and three isoforms have been identified in humans; PK1 [endocrine gland-derived vascular endothelial growth factor (EG-VEGF)], PK2 [mammalian Bv8 (mBv8)], and PK2β. The tertiary structure of MIT1 consists of a central β-sheet region supported by disulfide bridges with the secondary structure motifs composed of two three-stranded inverse β-sheets [135]. Recently, an NMR analysis of Bv8 from B. variegata was shown to be structurally similar to MIT1 [136] (Fig. 6). All of these proteins contain an identical N-terminal sequence, AVITGA, that is important for receptor binding [136] (Fig. 6). AVIT proteins bind to two mammalian receptors (PKR1 and PKR2) that are G-protein-coupled receptors with MIT1 having preferred affinity for PKR2 at least one order of magnitude higher than PK1 [137]. The physiological role of prokineticins binding to their respective receptors have been implicated in biological functions such as angiogenesis, neurogenesis, reproduction, inflammation, inflammatory pain and cancer [138]. Bv8 is a main pronociceptive mediator upregulated in neutrophils and inflammatory cells and is involved in initiating inflammatory responses and peripheral sensitisation. Blocking receptors PKR1 and PKR2 with antagonist PC1 led to pain and tissue recovery time reduction and could be a lead to chronic pain treatment [139].

Fig. 6.

Sequence alignment and 3D structures of AVIT proteins. Cysteine residues are shown in bold. Accession numbers are as follows: P58294, P25687, Q9PW66, Q14A28, Q8R413. A NMR structure of MIT1 (1IMT) highlighting the AVITGA residues in stick format (red). B NMR structure of Bv8 from B.variegata (2KRA) showing the AVITGA N-terminal region in red. Disulfide bridges are depicted in yellow

Disintegrins

Disintegrins are a domain of the snake venom metalloproteases (SVMP) and may act either as part of the complete SVMP, as post-translationally cleaved peptides from the SVMP or as selectively expressed gene products [140, 141]. These small cysteine-rich polypeptides are released in the venom by proteolytic processing of multidomain Zn2+-dependent metalloproteinases. Snake venom haemorrhagic metalloproteinases (SVMP) are found in the venoms of all advanced snakes and are classified into four classes depending upon their domain structure [142]. The ancestral state is the multidomain PIII form (60–100 kDa) that contains a metalloproteinase domain with disintegrin-like and cysteine-rich domains at the C-terminus. This toxin type is derived from the ADAM-type metalloprotease [4] and while PIII is found in all snake venom, the derived PI, PII and PIV types are unique to viper venoms.

The small cysteine-rich disintegrins were originally characterised as platelet aggregation inhibitors that are mediated through the blockage of β1 and β3 integrins and guided by a tripeptide motif (typically RGD) that binds competitively to specific integrin receptors [143]. Integrins are cell surface receptors that signal across the plasma membrane in both directions and are involved in growth, immune responses, leucocyte traffic, apoptosis, haemostasis and cancer. They recognise short peptide motifs in leucocytes as well as molecules such as laminin and collagen and RGD tripeptide specific proteins including fibronectin and vitronectin, with a key amino acid residue generally being acidic [144]. This is evident in the active inhibitory tripeptide sequences of disintegrins as each contains aspartic acid with the only exception being KTS that blocks the α1β1 integrin. The tripeptide RGD is active in most single-chain disintegrins that show different selectivity and binding affinity to the associated integrins including ligands α5β1, α8β1, αVβ1, αVβ3 and αIIbβ3 [145, 146]. Venom from Sistrurus miliarius barbouri and Gloydius ussuriensis contain medium-sized disintegrins exhibiting a KGD sequence with barbourin showing a high degree of selectivity for the αIIbβ3 integrin [147, 148]. Obtustatin from the venom of M. lebetina is a small disintegrin with a KTS motif that is a potent and selective inhibitor of the α1β1 integrin [149]. Dimeric disintegrins show greater sequence diversity of the integrin-binding motifs and include the heterodimeric EC3 from Echis carinatus with subunit B containing MLD tripeptide targeting α4β1, α4β7, α3β1, α6β1, α7β1, and α9β1 integrins; and a VGD tripeptide from the A subunit inhibiting the function of α5β1 integrins [150] (Fig. 7).

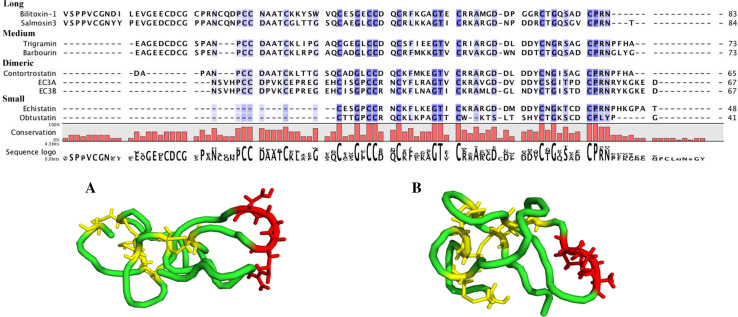

Fig. 7.

Multiple sequence alignment and three-dimensional structures of disintegrins. Alignment of snake venom long disintegrins (Bilitoxin-1, Salmosin3), medium disintegrins (Trigramin, Barbourin), dimeric disintegrins (Contortrostatin, EC3A, EC3B) and small disintegrins (Echistatin, Obtustatin) using CLC Main Workbench 6. Highly conserved residues are highlighted in purple while semi-conserved residues are a lighter purple. Sequence logo is shown below the alignment. Ribbon models A and B represent small disintegrins Echistatin (1RO3) and Obtustatin (1MPZ), respectively. Functional tripeptides are highlighted in red (Echistatin-RGD; Obtustatin-KTS) and disulfide bridges are highlighted in yellow

NMR analysis of various disintegrins reveals a mobile inhibitory loop containing the active tripeptide protruding 14–17 Å from the protein core [151, 152] (Fig. 7). The conformation of the loop, and hence, the biological activity is critically dependent on the appropriate pairing of cysteines [153]. In the case of obtustatin, the NMR solution structure shows the KTS inhibitory loop and C-terminus in close proximity and the KTS flanking residues of W20, Y28 and H27 acting as a hinge to provide overall flexibility to the loop [154].

The αIIbβ3 integrin plays a central role in platelet aggregation and has been targeted therapeutically in the form of antagonists to prevent thrombosis during percutaneous coronary intervention and high risk patients with acute coronary syndromes, such as diabetes mellitus [155]. The RGD and KGD tripeptides recognise the αIIbβ3 receptor preventing fibrinogen binding and interplatelet bridging. Hence two snake venom-derived drugs, Tirofiban (Aggrastat®) and Eptifibatide (Integrillin®), were designed as antiplatelet agents based on snake venom disintegrins. Tirofiban is based on the distance separating the side chains of Arg and Asp in the RGD sequence of echistatin [156, 157] and Eptifibatide is based on the KGD motif of barbourin isolated from Sistrurus m. barbouri venom [158]. Both drugs were beneficial in the treatment of acute coronary syndromes, especially percutaneous coronary intervention, but the emergence and success of antithrombotic P2Y12 antagonists like clopidogrel has restricted the use of these drugs in recent years [159].

A number of disintegrins from snake venom have been investigated as potential anti-angiogenesis therapeutics including RGD containing disintegrins triflavin, accutin, salmosin, contortrostatin and rhodostomin. The KTS or RTS containing disintegrins obtustatin, viperistatin, lebestatin and jerdostatin targeting the α1β1 integrin have also been shown to inhibit tumour angiogenesis. Contortrostatin, isolated from A. c. contortrix has shown the most promising results. The homodimeric RGD-disintegrin binds to an array of integrins (αIIbβ3, αVβ3, αVβ5, and α5β1) [160, 161] and therefore has potential to block a number of pathways associated with tumour development. Contortrostatin has been effective in targeting integrin associated tumour growth, angiogenesis and metastasis in breast [162, 163], ovarian [164] and prostate [165] cancer models.

Phospholipase A2

PLA2s are esterases that cleave the glycerol sn-2 acyl bond of glycerophospholipids to release lysophospholipids and fatty acids. The general structure of snake venom PLA2 enzymes is similar to mammalian enzymes and consists of three α-helices and two anti-parallel β-sheets stabilised by seven disulfides (Table 1) [166]. Snake PLA2s have been recruited twice independently into snake venoms, once into the Viperidae (Type IIA) and once into the non-front-fanged snakes & Elapidae (Type IB) (Fig. 8) [167]. The basal activity of Type I PLA2 is neurotoxicity resulting from physical damage to nerve terminals [7, 168] and this type has been mutated for a wide array of new toxicities, ranging from myotoxicity through to platelet aggregation inhibition. For example, PLA2 in the venoms of Australian elapids (particularly Pseudechis species and sea snakes) are powerfully myonecrotic releasing high amounts creatine kinase and myoglobin [169] while platelet aggregation-inhibiting Type I PLA2 enzymes are typified by those characterised from Austrelaps superbus [170]. In Type II PLA2s, Asp49 is conserved and important for catalysis on artificial substrates [171] with the basal activity of these toxins often neurotoxic but may also be myotoxic. Some Group II PLA2 enzymes have a lysine at position 49 resulting in loss of hydrolytic activity on artificial substrates and retaining non-enzymatic activities such as myotoxicity, oedema formation and anti-coagulation [172, 173] (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Multiple sequence alignment and three-dimensional structures of snake and mammalian PLA2s. Alignment of snake venom Group IA PLA2 (Notexin, Pa-11); Group IB PLA2 (OHV-PLA2); Group II PLA2 (Crotoxin basic chain, B. asper D49, B. asper K49) and mammalian sPLA2 (Human Group IIA, Human Group V) using CLC Main Workbench 6. Highly conserved residues are highlighted in red while semi-conserved residues are a lighter red. Sequence logo is shown below the alignment. Toxin nomenclature is based on Uniprot. Ribbon models are A Group IA Notexin (1AE7), red residues-H48, D49, teal residues-Y75, Y76, Y83, pink square-elapid loop; B Group IB OHV-PLA2 (1GP7), red residues-H48, D49, pink square-pancreatic loop; C Group II RVV-VD (1VIP), red residues-H48, D49; D Group II Piratoxin-II (1QLL), red residues-H48, K49. Both ribbon models C and D show the extended C-terminus in blue

The pharmacological effects induced by snake venom PLA2 enzymes are a result of mechanisms either dependent on or independent of the phospholipid hydrolytic activity, or a combination of both. These include pre- or post-synaptic neurotoxicity, cardiotoxicity, myotoxicity, platelet aggregation induction and inhibition, oedema, anti-parasitic, bactericidal, anti-coagulation, cytotoxicity and hypotension [166]. Hence, snake venom PLA2s are widely used as pharmacological tools to determine their biological and molecular role in diverse physiological processes. Pharmacological effects due to enzymatic activity are a result of membrane damage from hydrolysis of phospholipids or the released products of lysophospholipids and fatty acids that changes the local environment [166, 174]. Biological effects from enzyme-independent mechanisms include acting as an agonist or antagonist or by disrupting the protein–ligand interaction. Additionally, the venom may contain a number of PLA2 isoenzymes with distinct biological effects. This results in a myriad of pharmacological effects that can be explained by target sites located on cells or tissues that are recognised by specific pharmacological sites on the PLA2 enzyme [175]. For a detailed explanation of the ‘target model’ refer to Kini and Evans 1989 [175] and Kini review 2003 [166]. Chemical modification studies to identify the specific region of the molecule responsible for the pharmacological effect have shown only moderate success but do support the concept of separate catalytic and pharmacology sites [176].

PLA2 show tremendous promise for therapeutic use in a variety of areas. For example, Lys49 and Asp49 PLA2s isolated from Bothrops asper venom both showed similar bactericidal effects on both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria but only Asp49 displaying hydrolytic activity [177]. The membrane perturbing bactericidal effect of the Lys49 PLA2 was attributed to the cluster of basic and hydrophobic residues near the C-terminal loop of the synthetic toxin [177]. Snake venom PLA2s also have potential as anti-neoplasmic agents. Moreover, crotoxin, isolated from C. d. terrificus venom, is a cytotoxic heterodimeric, noncovalent complex consisting of an acidic subunit A and a basic subunit B. The 1:1 complex circulates undissociated until it binds to a target membrane whereby the toxin dissociates and subunit B begins a phospholipid hydrolysis of the ‘acceptor site’ leading to cell death. Subunit A may act as a chaperone in the process and also assist in target recognition. Crotoxin has produced promising results in Phase I clinical trials as an anti-cancer agent against solid tumours, with the principal side effect of neurotoxicity appearing to be manageable [178]. The cytotoxic action of crotoxin also demonstrates an autophagic mechanism in apoptosis of the human breast cell line MCF-7 cells [179]. Additionally, crotoxin shows analgesic effects on mice and rats by acting on the central nervous system but not by muscarinic or opioid receptors, and with no neuronal damage involved [180]. Interestingly, the excruciating pain caused by the bite from Micrurus tener tener is attributed to a heteromeric complex of a Kunitz-type serine protease inhibitor and a PLA2 (MitTx) acting as an agonist on acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) [93]. The highly selective and non-desensitising nature of the complex has enabled the isolation of ASICs and their association with pain sensation but, more so, has the potential to reveal other physiological pathways related to ASICs [93, 181] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Therapeutic potential examples for particular snake toxin families

| Toxin | Toxin family | Species | Function | Receptor/target | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNP-c | Natriuretic peptides | O. microlepidotus | Congestive heart failure | NPR-A | [21] |

| Crotamine | β-Defensins | C. d. terrificus | Cationic probe/molecule delivery | Cell/nucleus | [72] |

| Textlinin-1 (Q8008) | Kunitz peptides | P. textilis | Perioperative bleeding | Plasmin | [89] |

| Omwaprin | Waprins | O. microlepidotus | Antibacterial | Gram +ve bacteria | [95] |

| α-Bungarotoxin | Neurotoxic 3FTxs | B. multicinctus | Muscle and neuronal AChR | α1, α7 AChR | [190] |

| β-Cardiotoxin CTX27 | Cytotoxic 3FTxs | O. hannah | β-Adrenergic receptor blockers-heart failure | β-adrenergic receptor | [131] |

| Contortrostatin | Disintegrins | A. c. contortrix | Tumour growth, angiogenesis, metastasis | αIIbβ3, αVβ3, αVβ5, α5β1 integrins | [191] |

| Crotoxin | PLA2s | C. d. terrificus | Anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, anti-tumour, analgesic | Multiple targets | [184] |

Perspectives

In the past 20 years, the discovery and unravelling of complex snake venom has largely paralleled the technological advancements in proteomic and transcriptomic technology and separation techniques as well as the advent of matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionisation (MALDI) and electrospray as soft ionisation technologies in mass spectrometry. This review has underlined how snakes can utilise a lavish repertoire of toxin functionality through a molecular structural economy of employing privileged frameworks with the depth of diversity only beginning to be realised. Recent studies now show snake venom can typically contain several hundred components and that the high degree of variation is not only a result of the genetic makeup of a particular species, but also from post-translational modifications such as glycosylation and phosphorylation [182]. However, challenges still remain in venom complexity and identifying the less abundant components given the paucity of comprehensive snake venom sequences allocated to public databases. Compounded with the lack of genomic data, classic proteome approaches in discovering toxins often rely on alignment from established sequences. Until the snake venom content in public databases such as Uniprot is dramatically increased, there will be problems with utilising the present sequences to identify novel toxins.

Venomic methodologies incorporating next generation sequencing combined with highly sensitive and accurate mass spectrometry proteomic data from the same species (preferably from the same specimen) results in large-scale sequence data and is slowly building the collection of accurate snake toxins available in public databases. However, these sequences also need to be characterised for bioactivity and 3D structure to determine the pharmacophore; both strategies traditionally viewed as bottlenecks in the venomics pipeline [183]. High throughput screening of crude or fractionated venom and improvements in NMR are beginning to expedite the venomics process leading to better understanding of ligand-receptor interactions.

A robust database dedicated to snake venom containing sequence and structure information and classifying toxins according to parameters such as pharmocophore, taxonomy, post-translational modifications and disulfide scaffold, allows rapid and ease of access for the wider research community. Importantly, certain toxin families contain members displaying more than one pharmacophore. The heterodimeric toxin, crotoxin, displays many biological activities including neurotoxicity, cardiotoxicity and myotoxicity but has also shown immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, anti-tumour and analgesic actions [184]. Identification and characterisation of these pharmacophores, and subsequent classification on a dedicated database is one example of enhancing categorising of snake toxins to aid in future discovery of novel proteins/peptides.

A further extension of pharmacophore characterisation is the use of peptidomimetics. The epitope is infused into small secondary structure conformations to characterise the molecular basis of the ligand–receptor interaction and enhance stability or binding efficacy, but also facilitate delivery to the proposed target in physiological conditions. An example is the synthetic angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor Captopril, developed from a bradykinin-potentiating peptide from Bothrops jararaca (Brazilian pit viper) to treat cardiovascular disease and is now one of the twenty best selling drugs in the world. The characterisation of snake toxin pharmacophores is expected to increase rapidly in the next decade and peptidomimetics will play an important role in subsequent diagnostic and drug design from this research.

References

- 1.Fry BG, Vidal N, Norman JA, et al. Early evolution of the venom system in lizards and snakes. Nature. 2006;439:584–588. doi: 10.1038/nature04328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fry BG, Casewell NR, Wüster W, et al. The structural and functional diversification of the Toxicofera reptile venom system. Toxicon. 2012;60:434–448. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pyron RA, Burbrink FT. Extinction, ecological opportunity, and the origins of global snake diversity. Evolution. 2012;66:163–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fry BG. From genome to “venome”: molecular origin and evolution of the snake venom proteome inferred from phylogenetic analysis of toxin sequences and related body proteins. Genome Res. 2005;15:403–420. doi: 10.1101/gr.3228405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kordis D, Gubensek F. Adaptive evolution of animal toxin multigene families. Gene. 2000;261:43–52. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00490-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fry BG, Wüster W, Kini RM, et al. Molecular evolution and phylogeny of elapid snake venom three-finger toxins. J Mol Evol. 2003;57:110–129. doi: 10.1007/s00239-003-2461-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fry BG, Scheib H, van der Weerd L, et al. Evolution of an arsenal: structural and functional diversification of the venom system in the advanced snakes (Caenophidia) Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:215–246. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700094-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sunagar K, Jackson T, Undheim E, et al. Three-fingered RAVERs: rapid accumulation of variations in exposed residues of snake venom toxins. Toxins. 2013;5:2172–2208. doi: 10.3390/toxins5112172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menez A. The subtle beast. Snakes, from myth to medicine. London: Taylor and Francis; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camargo ACM, Ianzer D, Guerreiro JR, Serrano SMT. Bradykinin-potentiating peptides: beyond captopril. Toxicon Off J Int Soc Toxinology. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsetlin V, Utkin Y, Kasheverov I. Polypeptide and peptide toxins, magnifying lenses for binding sites in nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:720–731. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan W, Wu F, Morser J, Wu Q. Corin, a transmembrane cardiac serine protease, acts as a pro-atrial natriuretic peptide-converting enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8525–8529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150149097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu C, Wu F, Pan J, et al. Furin-mediated processing of Pro-C-type natriuretic peptide. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25847–25852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301223200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moro C, Lafontan M. Natriuretic peptides and cGMP signaling control of energy homeostasis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H358–H368. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00704.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang F-X, Liu X-J, Gong L-Q, et al. Inhibition of inflammatory pain by activating B-type natriuretic peptide signal pathway in nociceptive sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10927–10938. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0657-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potter LR, Yoder AR, Flora DR, et al. Natriuretic peptides: their structures, receptors, physiologic functions and therapeutic applications. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;191:341–366. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-68964-5_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Misono KS, Grammer RT, Fukumi H, Inagami T. Rat atrial natriuretic factor: isolation, structure and biological activities of four major peptides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;123:444–451. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)90250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He Xl, Chow DC, Martick MM, Garcia KC. Allosteric activation of a spring-loaded natriuretic peptide receptor dimer by hormone. Science. 2001;293:1657–1662. doi: 10.1126/science.1062246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogawa H, Qiu Y, Ogata CM, Misono KS. Crystal structure of hormone-bound atrial natriuretic peptide receptor extracellular domain: rotation mechanism for transmembrane signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28625–28631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313222200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schweitz H, Vigne P, Moinier D, et al. A new member of the natriuretic peptide family is present in the venom of the green mamba (Dendroaspis angusticeps) J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13928–13932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fry BG, Wickramaratana JC, Lemme S, et al. Novel natriuretic peptides from the venom of the inland taipan (Oxyuranus microlepidotus): isolation, chemical and biological characterisation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;327:1011–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee J, Kim SW. Dendroaspis natriuretic peptide administered intracerebroventricularly increases renal water excretion. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2002;29:195–197. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2002.03631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lisy O, Jougasaki M, Heublein DM, et al. Renal actions of synthetic dendroaspis natriuretic peptide. Kidney Int. 1999;56:502–508. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fry BG, Winter K, Norman JA, et al. Functional and structural diversification of the Anguimorpha lizard venom system. Mol Cell Proteomics MCP. 2010;9:2369–2390. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.001370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.St Pierre L, Flight S, Masci PP, et al. Cloning and characterisation of natriuretic peptides from the venom glands of Australian elapids. Biochimie. 2006;88:1923–1931. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshimura M, Yasue H, Morita E, et al. Hemodynamic, renal, and hormonal responses to brain natriuretic peptide infusion in patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation. 1991;84:1581–1588. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.4.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colucci WS, Elkayam U, Horton DP, et al. Intravenous nesiritide, a natriuretic peptide, in the treatment of decompensated congestive heart failure. Nesiritide Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:246–253. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007273430403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saito Y, Nakao K, Nishimura K, et al. Clinical application of atrial natriuretic polypeptide in patients with congestive heart failure: beneficial effects on left ventricular function. Circulation. 1987;76:115–124. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suwa M, Seino Y, Nomachi Y, et al. Multicenter prospective investigation on efficacy and safety of carperitide for acute heart failure in the “real world” of therapy. Circ J Off J Jpn Circ Soc. 2005;69:283–290. doi: 10.1253/circj.69.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sokolovsky M. Endothelins and sarafotoxins: physiological regulation, receptor subtypes and transmembrane signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:261–264. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90100-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yanagisawa M, Kurihara H, Kimura S, et al. A novel potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by vascular endothelial cells. Nature. 1988;332:411–415. doi: 10.1038/332411a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inoue A, Yanagisawa M, Kimura S, et al. The human endothelin family: three structurally and pharmacologically distinct isopeptides predicted by three separate genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:2863–2867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bloch KD, Hong CC, Eddy RL, et al. cDNA cloning and chromosomal assignment of the endothelin 2 gene: vasoactive intestinal contractor peptide is rat endothelin 2. Genomics. 1991;10:236–242. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90505-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Takuwa Y, et al. Cloning of a cDNA encoding a non-isopeptide-selective subtype of the endothelin receptor. Nature. 1990;348:732–735. doi: 10.1038/348732a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arai H, Hori S, Aramori I, et al. Cloning and expression of a cDNA encoding an endothelin receptor. Nature. 1990;348:730–732. doi: 10.1038/348730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawanabe Y, Nauli SM. Endothelin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:195–203. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0518-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kishi F, Minami K, Okishima N, et al. Novel 31-amino-acid-length endothelins cause constriction of vascular smooth muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;248:387–390. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kochva E, Viljoen CC, Botes DP. A new type of toxin in the venom of snakes of the genus Atractaspis (Atractaspidinae) Toxicon Off J Int Soc Toxinology. 1982;20:581–592. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(82)90052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wollberg Z, Shabo-Shina R, Intrator N, et al. A novel cardiotoxic polypeptide from the venom of Atractaspis engaddensis (burrowing asp): cardiac effects in mice and isolated rat and human heart preparations. Toxicon Off J Int Soc Toxinology. 1988;26:525–534. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(88)90232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takasaki C, Tamiya N, Bdolah A, et al. Sarafotoxins S6: several isotoxins from Atractaspis engaddensis (burrowing asp) venom that affect the heart. Toxicon Off J Int Soc Toxinology. 1988;26:543–548. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(88)90234-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weiser E, Wollberg Z, Kochva E, Lee SY. Cardiotoxic effects of the venom of the burrowing asp, Atractaspis engaddensis (Atractaspididae, Ophidia) Toxicon Off J Int Soc Toxinology. 1984;22:767–774. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(84)90159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wollberg Z, Bdolah A, Kochva E. Vasoconstrictor effects of sarafotoxins in rabbit aorta: structure-function relationships. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;162:371–376. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wollberg Z, Bousso-Mittler D, Bdolah A, et al. Endothelins and sarafotoxins: effects on motility, binding properties and phosphoinositide hydrolysis during the estrous cycle of the rat uterus. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 1992;3:41–57. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp.1992.3.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wollberg Z, Bdolah A, Galron R, et al. Contractile effects and binding properties of endothelins/sarafotoxins in the guinea pig ileum. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;198:31–36. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90558-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hayashi MAF, Ligny-Lemaire C, Wollberg Z, et al. Long-sarafotoxins: characterization of a new family of endothelin-like peptides. Peptides. 2004;25:1243–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mourier G, Hajj M, Cordier F, et al. Pharmacological and structural characterization of long-sarafotoxins, a new family of endothelin-like peptides: Role of the C-terminus extension. Biochimie. 2012;94:461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Atkins AR, Martin RC, Smith R. 1H NMR studies of sarafotoxin SRTb, a nonselective endothelin receptor agonist, and IRL 1620, an ETB receptor-specific agonist. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1995;34:2026–2033. doi: 10.1021/bi00006a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamaoki H, Kobayashi Y, Nishimura S, et al. Solution conformation of endothelin determined by means of 1H-NMR spectroscopy and distance geometry calculations. Protein Eng. 1991;4:509–518. doi: 10.1093/protein/4.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lamthanh H, Bdolah A, Creminon C, et al. Biological activities of [Thr2]sarafotoxin-b, a synthetic analogue of sarafotoxin-b. Toxicon. 1994;32:1105–1114. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(94)90394-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakajima K, Kubo S, Kumagaye S, et al. Structure-activity relationship of endothelin: importance of charged groups. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;163:424–429. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ganz T. Defensins: antimicrobial peptides of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:710–720. doi: 10.1038/nri1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shai Y. Mode of action of membrane active antimicrobial peptides. Biopolymers. 2002;66:236–248. doi: 10.1002/bip.10260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brogden KA. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:238–250. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bieber AL, Nedelkov D. Structural, biological and biochemical studies of myotoxin α and homologous myotoxins. Toxin Rev. 1997;16:33–52. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang CC, Tseng KH. Effect of crotamine, a toxin of South American rattlesnake venom, on the sodium channel of murine skeletal muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 1978;63:551–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1978.tb07811.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oguiura N, Boni-Mitake M, Rádis-Baptista G. New view on crotamine, a small basic polypeptide myotoxin from South American rattlesnake venom. Toxicon Off J Int Soc Toxinology. 2005;46:363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goncalves JM, Polson A. The electrophoretic analysis of snake venoms. Arch Biochem. 1947;13:253–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nedelkov D, O’Keefe MP, Chapman TL, Bieber AL. The role of Pro20 in the isomerization of myotoxin a from Crotalus viridis viridis: folding and structural characterization of synthetic myotoxin a and its Pro20Gly homolog. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;241:525–529. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chang CC, Hong SJ, Su MJ. A study on the membrane depolarization of skeletal muscles caused by a scorpion toxin, sea anemone toxin II and crotamine and the interaction between toxins. Br J Pharmacol. 1983;79:673–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1983.tb10004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rizzi CT, Carvalho-de-Souza JL, Schiavon E, et al. Crotamine inhibits preferentially fast-twitching muscles but is inactive on sodium channels. Toxicon Off J Int Soc Toxinology. 2007;50:553–562. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ownby CL, Cameron D, Tu AT. Isolation of myotoxic component from rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis viridis) venom. Electron microscopic analysis of muscle damage. Am J Pathol. 1976;85:149–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hong SJ, Chang CC. Electrophysiological studies of myotoxin a, isolated from prairie rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis viridis) venom, on murine skeletal muscles. Toxicon Off J Int Soc Toxinology. 1985;23:927–937. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(85)90385-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cameron DL, Tu AT. Chemical and functional homology of myotoxin a from prairie rattlesnake venom and crotamine from South American rattlesnake venom. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;532:147–154. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(78)90457-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fletcher JE, Hubert M, Wieland SJ, et al. Similarities and differences in mechanisms of cardiotoxins, melittin and other myotoxins. Toxicon Off J Int Soc Toxinology. 1996;34:1301–1311. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(96)00105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hirata Y, Nakahata N, Ohkura M, Ohizumi Y. Identification of 30 kDa protein for Ca(2+) releasing action of myotoxin a with a mechanism common to DIDS in skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1451:132–140. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(99)00082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nicastro G, Franzoni L, de Chiara C, et al. Solution structure of crotamine, a Na+ channel affecting toxin from Crotalus durissus terrificus venom. Eur J Biochem FEBS. 2003;270:1969–1979. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Torres AM, de Plater GM, Doverskog M, et al. Defensin-like peptide-2 from platypus venom: member of a class of peptides with a distinct structural fold. Biochem J. 2000;348(Pt 3):649–656. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Torres AM, Kuchel PW. The beta-defensin-fold family of polypeptides. Toxicon Off J Int Soc Toxinology. 2004;44:581–588. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mancin AC, Soares AM, Andrião-Escarso SH, et al. The analgesic activity of crotamine, a neurotoxin from Crotalus durissus terrificus (South American rattlesnake) venom: a biochemical and pharmacological study. Toxicon Off J Int Soc Toxinology. 1998;36:1927–1937. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(98)00117-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kerkis A, Kerkis I, Rádis-Baptista G, et al. Crotamine is a novel cell-penetrating protein from the venom of rattlesnake Crotalus durissus terrificus . FASEB J Off Publ Fed Am Soc Exp Biol. 2004;18:1407–1409. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1459fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nascimento FD, Hayashi MAF, Kerkis A, et al. Crotamine mediates gene delivery into cells through the binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21349–21360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604876200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hayashi MAF, Nascimento FD, Kerkis A, et al. Cytotoxic effects of crotamine are mediated through lysosomal membrane permeabilization. Toxicon Off J Int Soc Toxinology. 2008;52:508–517. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kunitz M, Northrop JH. Isolation from beef pancreas of crystalline trypsinogen, trypsin, a trypsin inhibitor, and an inhibitor-trypsin compound. J Gen Physiol. 1936;19:991–1007. doi: 10.1085/jgp.19.6.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Laskowski M, Jr, Kato I. Protein inhibitors of proteinases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1980;49:593–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.003113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Laskowski M, Jr, Qasim MA. What can the structures of enzyme-inhibitor complexes tell us about the structures of enzyme substrate complexes? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1477:324–337. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rawlings ND, Tolle DP, Barrett AJ. Evolutionary families of peptidase inhibitors. Biochem J. 2004;378:705–716. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schechter I, Berger A. On the size of the active site in proteases I. Papain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1967;27:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(67)80055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bode W, Huber R. Natural protein proteinase inhibitors and their interaction with proteinases. Eur J Biochem. 2005;204:433–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Takahashi H, Iwanaga S, Suzuki T. Isolation of a novel inhibitor of kallikrein, plasmin and trypsin from the venom of russell’s viper (Vipera russelli) FEBS Lett. 1972;27:207–210. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(72)80621-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen C, Hsu CH, Su NY, et al. Solution structure of a Kunitz-type chymotrypsin inhibitor isolated from the elapid snake Bungarus fasciatus . J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45079–45087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106182200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shafqat J, Beg OU, Yin SJ, et al. Primary structure and functional properties of cobra (Naja naja naja) venom Kunitz-type trypsin inhibitor. Eur J Biochem FEBS. 1990;194:337–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.St Pierre L, Earl ST, Filippovich I, et al. Common evolution of waprin and kunitz-like toxin families in Australian venomous snakes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:4039–4054. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8573-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Willmott N, Gaffney P, Masci P, Whitaker A. A novel serine protease inhibitor from the Australian brown snake, Pseudonaja textilis textilis: inhibition kinetics. Fibrinolysis. 1995;9:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schweitz H, Heurteaux C, Bois P, et al. Calcicludine, a venom peptide of the Kunitz-type protease inhibitor family, is a potent blocker of high-threshold Ca2+ channels with a high affinity for L-type channels in cerebellar granule neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:878–882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Millers E-KI, Trabi M, Masci PP, et al. Crystal structure of textilinin-1, a Kunitz-type serine protease inhibitor from the venom of the Australian common brown snake (Pseudonaja textilis) FEBS J. 2009;276:3163–3175. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Orchard MA, Goodchild CS, Prentice CRM, et al. Aprotinin reduces cardiopulmonary bypass-induced blood loss and inhibits fibrinolysis without influencing platelets. Br J Haematol. 1993;85:533–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1993.tb03344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mangano DT, Tudor IC, Dietzel C. The risk associated with aprotinin in cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:353–365. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Masci PP, Whitaker AN, Sparrow LG, et al. Textilinins from Pseudonaja textilis textilis. Characterization of two plasmin inhibitors that reduce bleeding in an animal model. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis Int J Haemost Thromb. 2000;11:385–393. doi: 10.1097/00001721-200006000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Earl STH, Masci PP, de Jersey J, et al. Drug development from Australian elapid snake venoms and the venomics pipeline of candidates for haemostasis: Textilinin-1 (Q8008), Haempatch™ (Q8009) and CoVase™ (V0801) Toxicon Off J Int Soc Toxinology. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kondo K, Toda H, Narita K, Lee CY. Amino acid sequence of beta 2-bungarotoxin from Bungarus multicinctus venom. The amino acid substitutions in the B chains. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1982;91:1519–1530. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a133843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kwong PD, McDonald NQ, Sigler PB, Hendrickson WA. Structure of β2-bungarotoxin: potassium channel binding by Kunitz modules and targeted phospholipase action. Structure. 1995;3:1109–1119. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00246-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Possani LD, Martin BM, Yatani A, et al. Isolation and physiological characterization of taicatoxin, a complex toxin with specific effects on calcium channels. Toxicon Off J Int Soc Toxinology. 1992;30:1343–1364. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(92)90511-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bohlen CJ, Chesler AT, Sharif-Naeini R, et al. A heteromeric Texas coral snake toxin targets acid-sensing ion channels to produce pain. Nature. 2011;479:410–414. doi: 10.1038/nature10607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Torres AM, Wong HY, Desai M, et al. Identification of a novel family of proteins in snake venoms. Purification and structural characterization of nawaprin from Naja nigricollis snake venom. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40097–40104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305322200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nair DG, Fry BG, Alewood P, et al. Antimicrobial activity of omwaprin, a new member of the waprin family of snake venom proteins. Biochem J. 2007;402:93–104. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Piletz JE, Heinlen M, Ganschow RE. Biochemical characterization of a novel whey protein from murine milk. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:11509–11516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ranganathan S, Simpson KJ, Shaw DC, Nicholas KR. The whey acidic protein family: a new signature motif and three-dimensional structure by comparative modeling. J Mol Graph Model. 1999;17:106–113–134–136. doi: 10.1016/s1093-3263(99)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hennighausen LG, Sippel AE. Mouse whey acidic protein is a novel member of the family of “four-disulfide core” proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:2677–2684. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.8.2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bingle CD. Towards defining the complement of mammalian WFDC-domain-containing proteins. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:1393–1397. doi: 10.1042/BST0391393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]