Abstract

Since their discovery, cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) have provided a novel, efficient, and non-invasive mode of transport for various (bioactive) cargos into cells. Despite the ever-growing number of successful implications of the CPP-mediated delivery, issues concerning their intracellular trafficking, significant targeting to degradative organelles, and limited endosomal escape are still hindering their widespread use. To overcome these obstacles, we have utilized a potent photo-induction technique with a fluorescently labeled protein cargo attached to an efficient CPP, TP10. In this study we have determined some key requirements behind this induced escape (e.g., dependence on peptide-to-cargo ratio, time and cargo), and have semi-quantitatively assessed the characteristics of the endosomes that become leaky upon this treatment. Furthermore, we provide evidence that the photo-released cargo remains intact and functional. Altogether, we can conclude that the photo-induced endosomes are specific large complexes-condensed non-acidic vesicles, where the released cargo remains in its native intact form. The latter was confirmed with tubulin as the cargo, which upon photo-induction was incorporated into microtubules. Because of this, we propose that combining the CPP-mediated delivery with photo-activation technique could provide a simple method for overcoming major limitations faced today and serve as a basis for enhanced delivery efficiency and a subsequent elevated cellular response of different bioactive cargo molecules.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00018-013-1416-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: CPP, Protein transduction domain, PTD, Photo-induction, Effective delivery, Endosomal release, Degradation, Stability

Introduction

The membrane barrier of the cell can be insurmountable for a number of currently used therapeutic agents (peptides, proteins, siRNA, etc.) causing a failure in the execution of their inherent activity. The plasma membrane barrier can, however, be overcome by combining the bioactive cargo molecule to a potent transport vehicle, for example a peptidic carrier called cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) that efficiently facilitates the internalization of the cargo into the cell. A vast potential lies in the use of CPPs as delivery vectors as their ability to elevate the efficiency of internalization of different cargos has been long recognized [1–4]. However, despite the accumulating data on effective delivery, many questions still remain unanswered, for example, questions concerning the intracellular fate, endosomal confinement and stability of the CPP-cargo complexes, the span of bioactivity of the cargo inside the cell, all of which hinder the efficiency of transport and subsequent effect(s).

Limitations in “effective” delivery arise, for instance, from the fact that the uptake occurs mostly by the induction of endocytosis, entrapping the CPP-cargo complexes after internalization inside membrane-enclosed vesicles [5–8]. The ability of CPPs and their cargo complexes to overcome this restraint has been determined to be the limiting step in CPP-mediated delivery by a number of reports [9–12]. Additionally, these intracellular vesicles primarily follow the path to become lysosomes as a number of different groups have shown that CPPs either alone or with a cargo tend to end up in acidic vesicles [13–15]. Therefore, most of the complexes are destined for degradation after internalization, leading to a decrease in the potential effects of the cargo molecule.

Photochemical internalization, or simply “photo-induction”, is a technology that uses light in combination with photosensitizers localized in the endo/lysosomal membranes to evoke light-induced rupture of the vesicle membranes [16, 17]. This method enables an efficient release of the endosome-entrapped material to enter the cytoplasm and reach its intracellular target(s). In many cases, light-induced endosomal leakage is achieved with chemical derivates that submerge into the vesicle membrane and rupture the lipid bilayer upon laser/light illumination [18, 19]. However, due to their possible toxicity and damage to the treated cells, the use of other, less harmful, reagents should be considered.

We have discovered that a cell-penetrating peptide TP10 in complex with a hydrophobic fluorescent dye (such as Alexa Fluor 633 or Texas Red) is able to promote an efficient endosomal escape of a protein cargo upon a brief illumination. This occurs in around 90 % of cells (with excitation at 545-580 nm) and does not require an additional chemical photosensitizer. TP10 was used primarily due to its high transport efficiency [20], its amphipathic nature and ability to interact with cellular membranes [21–23].

We also report here that this photo-induced escape occurs only at certain conditions (with an elevated CPP concentration and a prolonged (6 h) intracellular trafficking time) and in certain endosomes. Despite the requirement for a longer (6 h) intracellular trafficking time that would usually lead to the targeting of the endosomal material to lysosomes, we present semi-quantitative data that the endosomes that are induced to become leaky upon the light excitation are not acidic lysosomes, but instead possess a near-neutral pH. We also analyzed the degradation profiles of different protein cargo molecules and established that the cargo remains in its native form for at least 12 h inside the cells. We confirmed this with a functional assay where tubulin as the cargo molecule was incorporated into intracellular microtubular structures after photo-induced release from the endosomal confinement. Altogether, these results demonstrate that TP10 is a potent non-toxic carrier for protein cargos and with the assistance of the photo-induction method, it could perhaps also be developed to an in vivo drug delivery system.

Materials and methods

Cells

Wild-type Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO wt) were cultivated in humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO2 at 37 °C in Ham’s F12 medium (PAA Laboratories GmbH, Austria). Culture medium was supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) (PAA Laboratories, Austria), 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco, Invitrogen, UK).

Peptides and complexes

Peptide synthesis

The peptide-backbone of TP10 was assembled using an ABI 433A peptide synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA), using tBoc-strategy, HOBt/TBTU-activation and a MBHA-linker at 0.1-mmol scale. For selective labeling, we introduced an Fmoc side-chain protected lysine at pos 7, rendering the resin-bound fully protected intermediate product boc-AGYLLGK(Fmoc)INLKALAALAKKIL-MBHA-Resin (standard tBoc protective groups not abbreviated). The Fmoc group was removed by piperidine treatment, and the side-chain was labeled by 3 eq of FAM ((5,6)carboxyfluorescein) using DIPC-activation. The N-terminal Boc group was then removed using TFA, and biotinylated using 3 eq of biotin dissolved in DMSO activated with DIEA/TBTU. After coupling, the resin was subjected to an additional piperidine treatment to remove unwanted dimerization at the unprotected hydroxyl moiety on fluorescein. The peptide was finally cleaved with HF for 30 min at 0 °C using 10 % para-thiocresol as scavengers, extracted with diethyl ether and lyophilized. The final product (biotin-AGYLLGK-(FAM)-INLKALAALAKKIL-amide) was purified on a Supelco Discovery HS C18-10 reversed-phase HPLC column (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and the purity was verified as >98 % by analytical HPLC using C-18 reversed-phase column (Supelco, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and a prOTOF 2000 MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Amino acids, resin and coupling reagents were purchased from NeoMPS (Strasbourg, France), and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Formation of TP10b(N)-cargo complexes

To form complexes, N-terminally biotinylated TP10 (TP10b(N)) was mixed with 500 nM Alexa Fluor 633-labeled Streptavidin (SA) (Invitrogen, UK), Texas Red-labeled Neutravidin (NA) (Invitrogen, UK) or FITC- or Texas Red-labeled avidin in 3:1, 5:1, or 8:1 molar ratio in minimal volume of deionized water 5 min prior to application to cells.

Photo-induced endosomal escape

An amount of 8–10 × 103 CHO cells were seeded onto eight-well chamber slides (Lab-Tek, #155411, Nalge Nunc International, NY) 2 days before the experiment. On the day of the experiment, cells were incubated with complexes of either FAM-TP10b(N)-SA-Alexa Fluor 633, TP10b(N)-SA-Alexa Fluor 633, TP10b(N)-NA-Texas Red or TP10b(N)-avidin-Texas Red with or without 2 mg/ml dextran-TRITC (4 kDa) for 1 h at 37 °C in serum-free (sf) Ham’s F12, washed five times with PBS containing 0.5 mg/ml heparin to decrease the amount of non-internalized complexes from plasma membrane [24], and chased in serum-supplemented media for an additional 1, 3, 6, 12, or 24 h. Live cells were then imaged at 37 °C with an Olympus IX81 inverted microscope equipped with the FluoView 1000 confocal system (Olympus, Japan) using either a 60× water- [in endosomal escape experiments with excitation at 545–580 nm (with a mercury lamp)] or a 100× oil-immersion objective (for LysoSensor and Annexin experiments, and all excitation with a 635-nm laser) and excitation at 488 nm (for FAM, Alexa Fluor 488), at 559 nm (for Texas Red and TRITC) and 635 nm (for Alexa Fluor 633). Photo-induction was carried out with either a mercury lamp at 545–580 nm filter settings for 10 s to 1 min or 635-nm laser (10 % laser power) for 1 min. Accompanying release of dextran from the leaky endosomes was visualized after 635 or 559-nm laser induction. Images of cells were captured after photo-induction as described above. Obtained images were analyzed with Olympus FV1000 software FV10-ASW version 2.1a (Olympus, Japan) and processed with Adobe Photoshop CS4.

Toxicity of photo-induction treatment

CHO cells were seeded and incubated with complexes as described above. Thirty minutes before imaging and photo-induction, annexin V-Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, UK) in 1:100 dilution was added to serum-containing F12, where cell were visualized in. Imaging and photo-induction was carried out as described above. For induction of apoptosis and annexin V-binding, 10 μM staurosporine (3 h) was included as a positive control. Percentages of annexin V-positive cells were done by visual counting, and data was collected and analyzed in Microsoft Excel.

For MTT assay, cells were treated as described above. After photo-induction, the medium was changed and cells were left overnight in full medium. Cells were incubated with MTT (final concentration 0.5 mg/ml) in full medium for 4 h and precipitate was dissolved in equal volume of 20 % SDS in 0.02 M HCl overnight at RT. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm by spectrophotometry (Genios, Tecan, Austria) and data analyzed with Microsoft Excel.

Analysis of acidity of leaky endosomes

Cells were seeded and treated as described above. An amount of 2 μM LysoSensor (detectable at pH 4.5–6) (Invitrogen, UK) was added to the incubation medium 2 h before imaging and photo-induction treatment. The intensity of LysoSensor signal was measured in endosomes detected as leaky upon photo-induction and in strongly acidic (with high intensity) vesicles (lysosomes) with Olympus FV1000 software FV10-ASW version 2.1a. Data was analyzed with the statistical program R and MS Excel.

Estimation of TP10b(N)-cargo complexes degradation

Pulse-chase experiment

A total of 2.5 × 105 CHO wt cells per well were seeded onto six-well plates (Greiner BioOne, Germany) (for degradation assay) 1 day before the experiment. The next day, the cells were incubated with CPP-cargo complexes in serum-free F12 for 1 h as described above. Cells were then washed five times with PBS containing 0.5 mg/ml heparin. The medium was then changed to fresh serum-free Ham’s F12 and incubated at 37 °C for an additional 2, 5, 11, 23, or 47 h [for TP10b(N)-cargo degradation assays] or 0, 3, 6, 20, and 48 h [for FAM-TP10b(N)-cargo degradation assays].

Non-denaturing and denaturing condition fractions of TP10b(N)-cargo complexes

CHO wt cells, incubated as described above, were (after chase period) washed twice with PBS, trypsinized for 15 min at 37 °C to digest the remaining plasma membrane-bound peptide-cargo complexes from the cell exterior, and then collected. One milliliter of non-denaturing buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH6.8, 10 % (w/v) sucrose, Bromophenol Blue) was added per 50 mg of pellet, centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 rpm with a table top centrifuge, and supernatant removed. Cytosolic and soluble endosomal material is obtained this way. Supernatant contained the soluble fraction of complexes, which was validated with WB using antibodies against ROCK1 (goat polyclonal IgG ROCK1 (c-19), sc-6055, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA; dilution 1:200) (Online Resource 1). The rest of the material was dissolved by adding 1 ml 4× SDS-sample buffer (containing also β-mercaptoethanol) per 50 mg of cell pellet and sonicated 10 min at the highest intensity (cycle: 1-min pulse, 30-s pause) (Bioruptor, Diagenode, Belgium). This fraction contained membrane-bound material, which was validated with WB using antibodies against Caveolin-1 [cat no 610059, BD Transduction Laboratories, Belgium; 1:250 dilution)] (Online Resource 1).

Quantification of protein cargo and peptides in cell lysates

Samples in non-denaturing conditions and denaturing conditions were separated in 10 % SDS-PAGE [25, 26]. Band intensities were measured with Typhoon Trio (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA ) using the manufacturer’s recommendations for FAM/FITC or Alexa Fluor 633 signal. Signal intensities were normalized by ImageQuant to ng of cargo (avidin or SA) using fixed amounts of TP10b(N)-cargo complexes as external controls. Data was analyzed with MS Excel.

Functional assay with tubulin

Cells were seeded as described above. Complexes containing 500 nM tubulin-TRITC (Cytoskeleton, Inc., Denver, CO, USA), 1/3 amount (160 nM) SA-Alexa Fluor 633 and 4 μM TP10b(N) were left to form for 45 min at RT [complexes form due to electrostatic interactions between positively charged peptide and negatively charged tubulin (pI ~ 5.2)], added to cells in serum-free medium for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were then washed five times with PBS containing 0.5 mg/ml heparin, incubated in full medium for 3 h, imaged, incubated another 3 h, and then photo-induced as described above. Cells were then incubated another 3 h at 37 °C to allow tubulin-TRITC to be incorporated into microtubules. Tubulin-TRITC inside cells was imaged as described above using a 559-nm laser for excitation. Images were processed with Adobe Photoshop CS4.

Results

Photo-induction facilitates the endosomal escape of CPP-protein complexes

One of the major concerns in CPP-mediated cargo delivery is their endocytic uptake into cells, which results in their capture to endocytic vesicles. From there, their release into the cytosol is hampered by the endosomal membrane leading to decreased effects of the cargo molecule inside the cell. Even though some reports claim that CPPs can penetrate the lipid bilayer [27–30], this does not occur with CPP attached to a protein cargo larger than 50 amino acids in length [31]. The inability of large CPP-protein complexes to penetrate lipid membranes was confirmed in Fig. 1a, where no cytosolic staining can be observed. However, in order to bring about the effects of the cargo inside the treated cells, this release needs to be evoked.

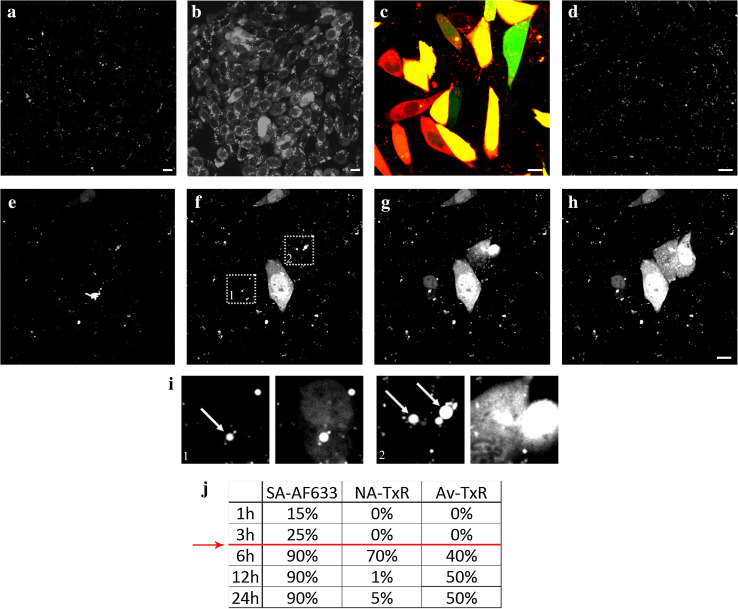

Fig. 1.

Photo-induction leads to an effective release of endosome-entrapped CPP-protein complexes. CHO cells were pulsed with 4 μM unlabeled (all, except c) or FAM-labeled (c, green) N-terminally biotinylated TP10 (TP10b(N)) complexed with 500 nM streptavidin (SA)-Alexa Fluor(AF) 633 (white in a, b, d–i; red in c) for 1 h and chased for additional 6 h (a–c, e–i) or 24 h (d). d Even after 24 h the complexes are still found inside endosomes, if not induced to escape. Photo-induction was carried out at 545–580 nm for 10 s (b, c) or with a 635-nm laser excitation for 1 min (e–h). e–h Image sequence of photo-induction with a 635-nm laser. i Close-ups from selected areas 1 and 2 in f illustrate the large intensely fluorescent endosomes (indicated by arrows) that are induced to become leaky upon light excitation. j Percentages of diffusely stained cells pulsed (1 h) and chased (indicated times) with TP10b(N) complexes with SA-AF633, neutravidin(NA)-Texas Red (TxR) or avidin (Av)-TxR after photo-induction at 545–580 nm. Red line indicates the time threshold for effective photo-induction. Bar 10 μm

As light may provide additional energy for the escape as shown before for CPPs alone [16, 32], we tested different microscope settings and treatment conditions to determine the optimal settings for photo-induced endosomal escape of the CPP-protein complexes. Cells were pulsed for 1 h with N-terminally biotinylated TP10 (TP10b(N)) complexed with 500 nM streptavidin (SA) labeled with Alexa Fluor 633, using different peptide-to-cargo ratios (3:1, 5:1, or 8:1) and chase times (1, 3, 6, 12, or 24 h). Despite having only four binding sites for biotin, we have established by native-PAGE that SA can indeed bind excess peptide (even at an 8:1 peptide-to-cargo ratio) with high efficiency (Online Resource 2). Photo-induction was carried out with either a mercury lamp at 545–580 nm (from here on referred to as excitation at 545–580 nm) or a 635-nm laser excitation.

When cells treated with CPP-protein complexes were subjected to excitation at 545–580 nm, visible bright flashes of endosome-entrapped complexes were detectable in the microscope (Online Resource 3), leading to a cytosolic diffuse distribution of the labeled complexes in almost all of cells in the viewing area (Fig. 1b). Since the complexes are visible in the microscope, we suspect that even though the used mercury lamp excitation range does not reach the maximum excitation of Alexa Fluor 633, there is enough absorption at the used shorter wavelengths that passes the filter to allow excitation, visualization, and photochemical induction of the dye. This highly efficient photo-induction also occurred with double-labeled complexes (FAM-labeled TP10b(N) with SA-Alexa Fluor 633) (Fig. 1c). However, no cytosolic release was evident in cells that did not receive the light impulse, even if the chase time was increased to 24 h (Fig. 1d).

As the mercury lamp excitation (even at the used longer wavelengths) might cause stress and photo-toxicity in the treated cells, we further tested the efficiency of escape of the CPP-cargo complexes after a 1-min, 635-nm laser impulse. Because the laser excitation is carried out as a continuous line-to-line scanning of the sample (instead of a steady energy impulse created by the mercury lamp), and the wavelength used is longer (635 nm, instead of a 545–580-nm range), the energy input per cell is at least several folds lower. The efficiency of the endosomal escape was markedly lower than with excitation at 545–580 nm, but not entirely absent as up to 10–15 % of cells showed cytoplasmic signal after laser excitation. A time series of a 1-min, 635-nm laser induction is seen in movie Online Resource 4 and different snapshots from the same movie are presented in Fig. 1e–h. The endosomes that become leaky upon the light-induction appear to be very large and strongly fluorescent, as seen in Fig. 1i (indicated by arrows). This implies that the endosomes that contain a high concentration of the CPP-cargo complexes are the most affected by the applied photo-induction treatment.

In parallel with SA as the cargo molecule, we also tested the photo-induction efficiency with different protein cargos—neutravidin (NA) and avidin (Av), labeled with Texas Red (TxR). NA and Av were chosen to yield additional information on the significance of the charge (or the isoelectric point (pI)) of the cargo molecule on the photo-induction efficiency. We discovered that despite some cytosolic release in case of all the used cargos, there is a negative correlation of escape efficiency to the charge of the cargo—the more positively charged the cargo the less efficient is the photo-induced release from the endosomes (Fig. 1j, Online Resources 5 (arrows), 6). Regardless of the recorded higher percentage of cells displaying cytosolic staining after 12 and 24 h chase in case of Av compared to NA in Fig. 1j and Online Resource 6, the intensity of the diffuse signal inside the cytoplasm of photo-induced cells was markedly higher with TP10b(N)-NA- than with -avidin-complexes (Online Resource 5).

Additionally, different chase times were analyzed, revealing that at least 6 h was needed for the complexes to “prepare” the endosome for a photo-induced destabilization (Fig. 1j (red line), Online Resource 5). Moreover, the photo-induction only occurs when a higher peptide-to-cargo ratio (8:1) was used (Online Resource 6), hinting that having excess peptide is one of the prerequisites for an efficient endosomal escape.

Next, we assessed whether the endosomes that become leaky during the photo-induction are releasing only the complexes to the cytosol or also other material entrapped inside of them. For this, we co-incubated the cells with 4 μM TP10b(N) complexed with SA-Alexa Fluor 633 and 2 mg/ml dextran-TRITC for 1 h, chased for additional 6 h and conducted a 635-nm laser induction in order to bring about the photo-induced endosomal escape. Some of the cells that displayed the diffuse signal from the complexes also had a detectable cytosolic staining of the dextran-TRITC (Online Resource 7). This suggests that not only the complexes are escaping from the endosomes but also other material that is entrapped inside the same endosomes is released upon an effective photo-induction process. However, CPP seems to be a compulsory element in this phenomenon, as similar photo-induction of dextran-TRITC with a 559-nm laser did not create the same effects (Online Resource 7).

Photo-induction is not toxic to cells

Because light may cause photo-toxicity and photo-damage to live cells upon extended imaging [33], we next tested how harmful the photo-induction is for the treated cells. To investigate this, we pulsed the cells with 4 μM TP10b(N) complexed with 500 nM SA-Alexa Fluor 633 (8:1 ratio) and chased for an additional 6 h before subjecting them to the photo-induction. Annexin V-Alexa Fluor 488 was used to visualize apoptotic/necrotic cells before and after photo-induction (Fig. 2). All the cells that had gained a detectable amount of annexin V onto their membrane were registered as annexin V-positive, regardless of the intensity of the signal. As a positive control, 10 μM staurosporine was used, inducing binding of annexin V to all cells.

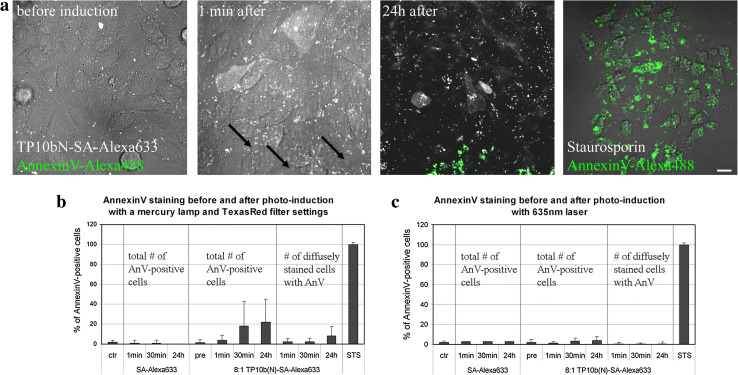

Fig. 2.

Photo-induction at 545–580 nm, but not with 635-nm laser, causes some cells to become apoptotic. CHO cells were pulsed with 4 μM TP10b(N) complexed with 500 nM SA-Alexa Fluor 633 (white) (a–c) or with 500 nM SA-Alexa Fluor 633 alone (b, c) for 1 h and chased for additional 6 h. Exposure of phosphatidylserine to the plasma membrane of treated cells before and after photo-induction at 545–580 nm was detected with annexin V-Alexa Fluor 488 (green in a). Arrows in a indicate cell blebbing. As a positive control 10 μM staurosporine was used. Bar 20 μm. b, c Quantification of the number of annexin V-positive cells before and after photo-induction at 545–580 nm for 10 s (b) or with 635-nm laser excitation for 1 min (c), untreated cells (ctr) were used as negative control

The excitation at 545–580 nm resulted in the blebbing of some adjacent cells in the viewing area immediately after photo-induction (Fig. 2a). Annexin V-staining also implies that some of the light-induced as well as surrounding cells acquire characteristic apoptotic/necrotic signals, such as the exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS) on the outer leaflet of the membrane. Up to 20 % of all the cells in the photo-induced area eventually (after 24 h of photo-induction) gained the annexin V staining, however, it is noteworthy that only around 10 % of the cells that were detected as having a diffuse staining of complexes inside the cytoplasm were annexin V-positive. All the percentages of annexin V-positive cells before and after excitation at 545-580 nm are presented in Fig. 2b.

We also tested the photo-damage of the 635-nm laser excitation and discovered that even though up to 5 % of cells acquired the annexin V staining, the level of affected cells was not higher than the cells not exposed to the laser light (Fig. 2c and Online Resource 8).

As dead cells might detach from the dish, resulting in an underestimation of cell death after photo-induction treatment, we also conducted a long-term MTT assay to assure that the light treatment does not harm the cells. For this, we treated the cells as described above, photo-induced either with excitation at 545–580 nm or laser light at 635 nm, incubated them overnight, and measured the viability with MTT assay. The results confirm that the excitation method used here is not toxic to cells, since around 85 and 90 % of cells were viable after treatment with 545–580-nm or 635-nm light, respectively (Online Resource 8).

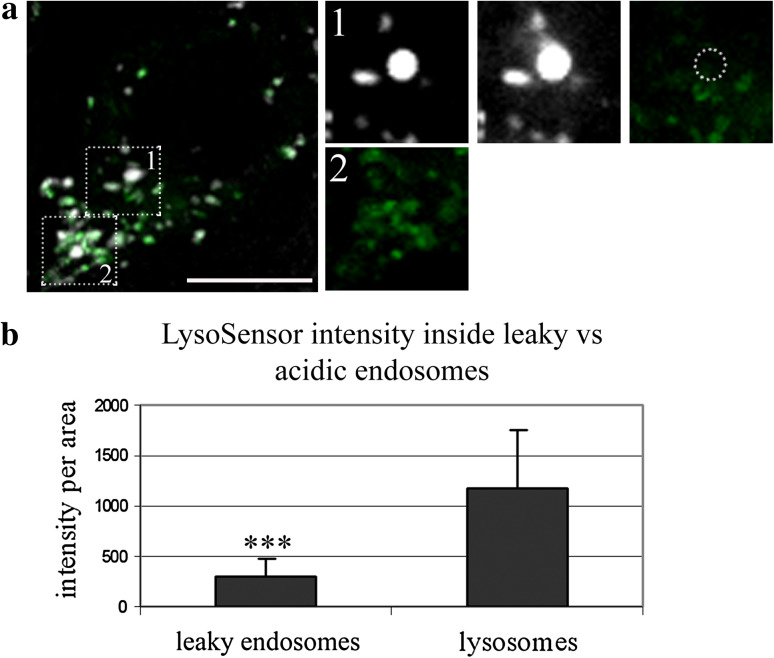

Endosomes that become leaky upon photo-induction are not acidic

As the photo-induced endosomal escape occurs mainly after 6 h of chase period and a prolonged intracellular trafficking inside endosomes may target their contents (such as our CPP-protein complexes) to low-pH degradative organelles, it is crucial to assess the pH of the endosomes that become leaky upon the photo-induction treatment. To analyze this, we treated the cells as described above using an 8:1 peptide-to-cargo ratio and 6 h of chase time. Two hours before photo-induction, cells were incubated with a pH-sensitive probe LysoSensor, which has a variable fluorescence emission intensity depending on the pH of the environment, being highly fluorescent under acidic, but less intense in near-neutral conditions (Online Resource 9). The 635-nm laser was used for photo-induction due to the photo-bleaching of the LysoSensor upon longer mercury lamp exposure times (even when a 545–580-nm filter was used).

A cell, where a characteristic large intense endosome containing TP10b(N)-SA-Alexa Fluor 633 complexes is about to become leaky during the photo-induction treatment, is depicted in Fig. 3a. The intensity of the LysoSensor inside this endosome is relatively low compared to the typical lysosomes of the same cell (Fig. 3a, inserts 1 and 2). Quantification of the LysoSensor signal intensities inside the leaky endosomes and acidic endosomes/lysosomes revealed that the difference is significant (Fig. 3b). This indicates that the complexes are released from endosomes that have not (yet) acquired a low pH. Thus, since the CPP-protein complexes are photo-induced to escape from non-acidic endosomes, the complexes, and, most of all, the cargo molecules might still be intact and functional after their release into the cytosol.

Fig. 3.

Large intensely fluorescent endosomes that become leaky upon photo-induction are not as acidic as lysosomes. a TP10b(N)-SA-Alexa Fluor 633 complexes (white) are found in endosomes marked with pH-sensitive LysoSensor dye (green). A large intensely fluorescent endosome becoming leaky upon photo-induction is indicated in the upper area, and the sequence of endosomal leakage and the LysoSensor signal inside the same endosome are shown in the upper panel of images on the right. The edges of the leaky endosome are marked as a dotted circle in the far right image. The LysoSensor signal in lysosomes of the same cell is highlighted in the lower area; its close-up is on the bottom right image on the right. b Quantification of the LysoSensor signal intensity in leaky and strongly acidic endosomes; p value <0.001 (n = 67). p values <0.001 are marked with triple asterisks. Bar 10 μm

The cargo remains intact inside the cells for at least 12 h

In order to act on its cellular target(s), the transported cargo needs to remain bioactive inside the cells after internalization. As we discovered above, the endosomes becoming leaky upon photo-induction were not acidic. Therefore, we aimed to further evaluate the integrity of the CPP-protein complexes inside the cells. For this, we conducted a degradation estimation assay where we pulsed the cells with 1.5, 2.5, or 4 μM TP10b(N) complexed with 500 nM SA-Alexa Fluor 633 (corresponding to 3:1, 5:1, or 8:1 peptide-to-cargo ratios) for 1 h, washed extensively with heparin-containing PBS to remove any externally bound complexes, and chased for an additional 3, 6, 12, 24, or 48 h. Cells were then subjected to a 15-min trypsin treatment to digest peptides from the cell exterior, then lysed first at (i) non-denaturing conditions to obtain a soluble fraction of the CPP-cargo complexes; and, second, the remaining pellet was dissolved in (ii) denaturing conditions to dismantle the rest of the complexes from the membrane-bound material (from hereon referred to as the membrane-bound fraction). The successful fractionation of the soluble and the membrane-bound cellular components with this method was confirmed with Western blot using ROCK and Caveolin-1 for visualization of soluble and membrane-bound proteins respectively (Online Resource 1). All samples with TP10b(N)-SA-complexes were applied to SDS-PAGE for protein separation and complexes were visualized in gel by exciting the fluorophore attached to the protein cargo.

A representative image from the degradation assay along with the different sizes of the remaining CPP-cargo complexes after given chase times are shown in Fig. 4a. As demonstrated already[34, 35], a higher amount of peptide in complex with the cargo leads to a more efficient internalization of the complexes. However, the analysis of the degradation pattern of the protein cargo has usually been overlooked.

Fig. 4.

Protein cargo in complex with CPP remains intact inside the cells for at least 12 h. CHO cells were pulsed with 1.5, 2.5, or 4 μM TP10b(N) complexed with SA-Alexa Fluor 633 (resulting in 3:1, 5:1, and 8:1 peptide-to-cargo ratios, respectively) for 1 h and chased for the additional time. The soluble fractions of the treated cells were applied to a 10 % SDS-PAGE and the fluorescence signal was visualized. LC marks loading control, which is TP10b(N)-SA complexes in an 8:1 ratio without cells (a). The cargo bands from different lanes were analyzed together as intact (>17 kDa, black) and degraded (≤17 kDa, gray) (b) or separately (c). The ratio of 8:1 gave the highest internalization efficiency as well as displayed the best preservation of the cargo molecule. Additionally, most of the protein cargo remained intact (in a tetrameric form) for at least 12 h. d Fluorescence signals of dual-labeled complexes (FAM-TP10b(N)-SA-Alexa Fluor 633) were also visualized by SDS-PAGE and the intensities of both signals were plotted over time to depict the degradation kinetics of the whole CPP-cargo complex. The peptide deserts the complex rather quickly, nonetheless, a fairly large amount of the peptide is still present in cells after 7 h of incubation

A closer analysis of the breakdown of the SA cargo revealed the formation of four distinct SA products, which were present at all used peptide-to-cargo ratios—the 72- and the 55-kDa product (the SA tetramers) constituting the pool of intact cargo (Fig. 4b), and the two disassociation and/or degradation products, the fractions of SA with a size around 17 and 11 kDa, representing possibly the SA monomer and the further degraded products, respectively. The loading control (LC in Fig. 4a), which only contains TP10b(N)-SA-Alexa Fluor 633 complexes in an 8:1 ratio (without cells), reveals that most of the product sizes are also present when the complexes are not added to the cells, i.e., on their own. From this, we speculate that the 72-kDa product, which is not present without the peptide (Online Resource 10), is perhaps an SA tetramer that has up to eight CPPs (each around 2 kDa in size) bound to it. Correspondingly, the ~55 kDa one contains possibly an SA tetramer with up to four CPPs (bound via biotin) and less, seen as the upper and lower part of the band, respectively.

Quantification of the intact and degraded products showed that the SA cargo remains intact (in its tetrameric form) inside the cells for at least 12 h, reaching around 550 ng of SA (1.1 ng SA/μg cell pellet) when cells were incubated with an 8:1 peptide-to-cargo ratio (Fig. 4c). Additionally, the difference in delivered and preserved SA tetramer is ~4.4–10-fold in favor of the higher (8:1) peptide-to-cargo ratio when compared to other peptide-to-cargo ratios used. Moreover, the amount of cargo still bound to CPPs after prolonged periods of time is profoundly higher at an 8:1 ratio. The amount of intact cargo peaks around 12 h from whereon it is slowly but steadily subjected to degradation, observed as a decrease in the intensity of first the higher molecular weight bands and then the smaller ones.

A similar analysis was carried out with the membrane-bound fraction of TP10b(N)-SA complexes, where the results were essentially the same (Online Resource 11), even though the levels of membrane-bound complexes were much lower than that of the non-membrane bound ones. Moreover, as the photo-induction treatment may also cause the release of endosomal enzymes into the cytosol and thus promote a faster degradation of the cargo, we analyzed the cargo integrity after photo-induction as well. We determined that this does not affect the cargo degradation and similar results to non-photo-induced cells were observed (Online Resource 11d).

We also conducted the same experiment with avidin-FITC as the model for highly positively charged cargo molecule. FITC instead of a Texas Red label was used due to difficulties in visualizing the latter in the polyacrylamide gel. We found that avidin, unlike SA, displayed strong interactions with some cellular contents despite the presence of denaturing SDS in the polyacrylamide gel, and gave rise to an excessive smear on the upper side of the gel (Online Resource 12). As aggregation presumably shields the peptide and the cargo from the degradative enzymes, this portion of the complexes was defined here as a part of the “intact” complexes (in Online Resource 12b). Additionally, no strong correlation between the complex internalization and stability on the used peptide-to-cargo ratio were observed as with SA, as 5:1 ratio gave almost a similar amount of intact cargo levels and similar degradation kinetics as 8:1 ratio. Furthermore, while the total amount of intact (≥67 kDa) cargo reaching the cells (Online Resource 12; 650 ng, corresponding to 1.3 ng avidin/μg cell pellet) was similar to the levels with TP10b-SA (Fig. 4b), the amount of tetrameric protein in the soluble fraction was almost ten times lower 60 ng of avidin (Online Resource 12) compared to 550 ng of SA (Fig. 4c) at 12 h and 8:1 ratio.

TP10b(N)-avidin-FITC complexes were also found in aggregates in the membrane-bound fractions (Online Resource 13), depicting possibly a strong association of the complexes with the membrane components. Since aggregates do not form without the cells (Online Resource 13d), it can be concluded that the initiation of the complex aggregation is evoked by their interaction with plasma membrane components, probably heparan sulfate proteoglycans [36].

Next we analyzed the integrity of the peptide in the complex. For this, we used double-labeled complexes (FAM-labeled TP10b(N) with SA-Alexa Fluor 633) in an 8:1 peptide-to-cargo ratio and the same degradation assay as described above. Most of the peptide in the soluble fraction was not bound to the cargo protein. Since the separating gel contained SDS, it is plausible that the peptide detached from the protein cargo in the denaturing conditions of the SDS-containing gel (Online Resource 14). Nevertheless, the total amount of the peptide still present inside the cells stays above 60 % for at least 10 h (t 1/2 is ~20 h) (Fig. 4d), giving it enough time to participate in the photo-induced endosomal escape process.

Photo-inducted tubulin is readily incorporated into tubular structures

In order to validate that the cargo released upon photo-induction is indeed intact and functional, we used tubulin as a functional cargo molecule. Tubulin was chosen because it has similar pI (~5.2) and size (55 kDa) to SA, which was the most efficient cargo in our experiments. Moreover, tubulin is a cytosolic protein, which means it needs not to be targeted further to specific cellular compartment and its incorporation to microtubules can be observed directly via the fluorescent label attached to the protein. Additionally, as the polymerization of tubulin requires the presence of GTP, the microtubules may only form inside the cells where the pool of GTP is available.

Even though tubulin was labeled with TRITC fluorophore, we could not observe efficient photo-induction with TP10b(N)-tubulin-TRITC complexes alone (Fig. 5a). Nonetheless, around 15–20 % of cells possessed fluorescent microtubules (data not shown), indicating that TP10b(N) was, to some extent, able to transport the functional cargo to the cytosol even without photo-induction.

Fig. 5.

Tubulin, as a functional cargo, is efficiently incorporated into tubular structures after photo-induction treatment. CHO cells were pulsed with 4 μM TP10b(N) complexed with 500 nM tubulin-TRITC (white, pseudocolor) and 160 nM (1/3 amount) SA-Alexa Fluor 633 (not shown) for 1 h, chased for an additional 6 h and photo-induced at 545–580 nm. Tubulin-TRITC-positive tubular structures (indicated with arrows) were visualized 3 h after photo-induction. Bar 20 μm

To achieve an efficient photo-induction and increase the release of the functional tubulin into cytosol, we added 160 nM (1/3 amount) SA-Alexa Fluor 633 into the solution along with 500 nM tubulin-TRITC to TP10b(N). Tubulin that had been released from the endosomes during photo-induction was efficiently incorporated into tubular structures (usually 3–5 μm in length) in more than 50 % of the treated cells (Fig. 5b). Hence, at least a two–threefold increase in the released functional cargo was accomplished with the photo-induction technique. Moreover, our results corroborate our previous hypothesis that the cargo liberated from the endosome upon photo-induction remains intact and functional.

Discussion

Limitations in effective delivery have hampered the use of several bioactive drugs [37–39], demanding for the development of new approaches to overcome the faced hurdle(s). The use of cell-penetrating peptides has proven to strongly elevate the amount of drugs delivered into the target cells both in vitro and in vivo [1–3], confirming thus their high potential in defeating at least some of the problems associated with poor delivery. However, despite the numerous success stories, key issues concerning the intracellular trafficking, stability, and cytosolic release of the CPP-cargo complexes have not been fully understood.

As stated above, one of the biggest challenges in the field of CPP-mediated cargo delivery today is overcoming the limited escape of the complexes from the entrapping endosomes, as this confinement results in the failure of the cargo to function in other compartments of the cells. In light of this, we applied a photo-induction approach in combination with a potent CPP and a fluorophore, and demonstrated here that this method is not only highly efficient but also non-toxic, yielding an endosomal escape of an intact and functional cargo molecule. Despite the recent recognition that photo-induction can be efficiently applied in case of some CPPs [16, 32, 40] or CPP-photosensitizer conjugates [18, 19], this is the first demonstration of some of the specific conditions that have to be met to evoke such a release with a CPP as the transporter. Furthermore, we have characterized the endosomes that are forced to become leaky upon this treatment. As these aspects are prerequisites for an efficient endosomal release, we believe that our findings are significant for the further development of the CPP-mediated drug delivery system.

In order to pinpoint the optimal conditions for the photo-induced endosomal escape, we used fluorescently labeled streptavidin (SA) in complex with N-terminally biotinylated TP10 (TP10b(N)) in varying peptide-to-cargo ratios. N-terminally, instead of the widely used side-chain-biotinylated TP10, was used due to observed higher photo-induced escape (unpublished data). As SA and other avidin-like molecules possess four biotin binding pockets in their native tetrameric form, the 3:1 ratio depicts the situation where all the CPP is incorporated into the complexes leaving no free peptide in the solution. Correspondingly, in a 5:1 and 8:1 ratio, there is presumably an increasing amount of excess peptide associated with the complex via electrostatic (peptide-to-cargo) and/or hydrophobic (peptide-to-peptide and/or protein) interactions. Indeed, we have established by native-PAGE that despite having only four binding sites for biotin, SA can bind excess peptide (even at 8:1 peptide-to-cargo ratio) with high efficiency (Online Resource 2). Since effective photo-induction occurs only at a higher (8:1) peptide-to-cargo ratio, the excess peptide must play a vital role in membrane remodeling. For example, it can assist in the clustering of the complexes and peptides into specific sites at the endosomal membrane and create a local imbalance at the lipid bilayer, as suggested before [41]. Moreover, it could be speculated that this clustering also brings the fluorophore to close proximity of the endosomal membrane, which would then reinforce the destabilization of the endosomal membrane upon an energy impulse, such as the mercury lamp irradiation or laser excitation (Fig. 1, Online Resources 3, 4).

We further demonstrated that the membrane destabilization takes place in certain complexes-condensed endosomes only (Fig. 1e–i) and that these endosomes need a time-dependent maturation before the photo-induction phenomenon can be evoked by the combined action of the CPP and the fluorophore. We propose that one of the key factors guiding the endosomal escape is the time-dependent accumulation of the complexes into large vesicles packing a high amount of the CPP-cargo complexes (Fig. 1i). The consequent high local intravesicular peptide concentration has been shown to strongly modify the arrangement of lipids [42–44] and may thus be one of the prerequisite conditions preceding the endosomal membrane destabilization event.

Another factor explaining the time-dependence of the photo-induced endosomal escape might be the specific lipid composition that is required for the better membrane binding and its concomitant destabilization by the CPP. It has been demonstrated recently that a known CPP Tat can destabilize liposomes that comprise an anionic lipid bis(monoacylglycero)phosphate (BMP) highly enriched in the membrane of intraluminal vesicles of the multivesicular bodies, but not the vesicles resembling the plasma membrane composition [45]. Also, the influence of the membrane associating behavior of Penetratin and TP10 on the molecular nature of lipids, showing a higher affinity towards negatively charged phospholipids, has been demonstrated before [46, 47]. Hence, a number of CPPs exhibit a preference for specific lipid(s) for interaction, and upon binding to these, an increased membrane destabilization may be achieved. Therefore, during the massive lipid sorting and conversion on the endosomal membranes during the sorting, trafficking, and maturation of endosomes [48], a lipid composition may be reached that could in turn induce a more pronounced membrane association of the peptide and the complexes. Furthermore, more mature late endosomal membranes have been shown to incorporate a high proportion of anionic phospholipids [49], which may assist in better clustering of TP10 onto the membrane due to the electrostatic interactions and facilitate the subsequent membrane disturbance leading to the observed effects of endosomal escape. However, the question of whether the mechanism of destabilization involves the formation of a transient pore [41, 47] or the induction of non-lamellar lipid structures, such as a transition to inverted hexagonal [50–52] or a cubic phase [52], remains to be explored.

Yet another factor contributing to the efficiency of the endosomal escape seems to be the characteristics, e.g., the charge (or isoelectric point (pI)) of the cargo molecule. We showed that the most prominent cytosolic release occurs in case of SA, while the release of avidin as the cargo molecule is quite trivial (Fig. 1, Online Resources 2, 6). This could be explained by many possibilities.

First, avidin, possessing a high positive charge (due to abundant glycosylation), remains extensively associated with the plasma membrane components inside the complexes-containing endosomes (Online Resources 12, 13). Moreover, these dense aggregates of avidin (that are formed only in the presence of membrane-associated cellular material (Online Resource 13d) (likely by anchoring of the CPP-avidin complex to the negatively charged extracellular material/matrix)) stay relatively intact for at least 12 h inside cells (Online Resources 12, 13). This suggests that even if the photo-induction and subsequent membrane destabilization were to be successful, the agglomerate could still (i) be membrane bound via, e.g., the proteoglycans or (ii) be possibly just too bulky to exit the endosome and enter the cytoplasm. Thus, even though the intense aggregation (upon association with e.g., the anionic proteoglycans) may protect the cargo and also the peptide from fast degradation, our results imply that it may also restrain either the enhanced membrane destabilization or the endosomal leakage of the complex. Furthermore, the results with NA, possessing a relatively neutral charge (pI ~ 6.3, higher than SA, but lower than avidin), demonstrated an intermediate outcome in both aggregation and in photo-induced endosomal escape (Online Resources 15, 6), speak in favor of our argument.

Alternatively, due to the repulsive forces between the cationic CPP and the basic avidin (pI ~ 10.5), the clustering of complexes and unbound CPPs into specific locale at the endosomal membrane might be less efficient than with SA. This, in turn, would possibly create fewer opportunities to reach the threshold peptide/lipid/fluorophore ratio that is required for the membrane destabilization event. Another possibility could be that the differences in photo-induction efficiencies may arise from the varying abilities of the different cargo molecules to bind the positively charged peptide. That is, the negatively charged SA (pI ~ 5–6) is able to bind more peptide via electrostatic forces than avidin (pI ~ 10.5), resulting in more unbound peptide in the latter case. Because of limited interaction between the free peptide and the peptide-avidin complexes, they may be taken up by cells via different routes, which could lead to their capture in different intracellular vesicles. In this scenario, there might not be enough peptide inside the vesicle to cluster the complexes together and induce the membrane destabilization upon photo-induction.

Another interesting aspect rose with NA as the cargo, when efficient photo-induction was only accomplished after 6 h chase, minimizing to almost nothing after longer timepoints (Fig. 1j). The cause of this limited photo-induction window (that was not observed with neither SA nor avidin) may arise from the differences in the binding and packing of the peptide to the cargo, and subsequently the peptide’s exposure to degradative enzymes and therefore also its ability to evoke the photo-induced escape. We speculate that due to its strong negative charge, SA binds the peptide with high affinity resulting in a dense packing of the peptide around the cargo, protecting the peptide from degradation. Avidin, on the other hand, may protect the peptide from early degradation due to shielding of the peptide with its glycosyl-chains. NA, however, binds peptide with lower affinity (due to its higher pI compared to SA) and does not possess extending (possibly protective) chains, therefore, the peptide in complex with NA may be more susceptible to degradative enzymes and lose its ability to promote efficient endosomal escape faster.

Despite the fact that endosomal maturation is usually accompanied by a drop of pH inside the lumen of the vesicles, we discovered that the endosomes that become leaky upon the photo-induction treatment exhibit a relatively neutral intravesicular pH (pH ~ 6) regardless of a prolonged 6 h intracellular trafficking (Fig. 3). The delay in the acidification process might enable the peptide to accumulate in the membrane as well as bring the cargo with the accompanying fluorophore in close vicinity to the lipid bilayer. Thereon, when the light impulse is applied, the combination of already somewhat destabilized membrane is possibly subjected to local lipid peroxidation due to the formation of reactive oxygen species from the excited fluorophore’s electron, as suggested before [32]. Our own results support this possibility as the treatment of cells with α-tocopherol (vitamin E), a potent antioxidant, hindered the photo-induction efficiency in a dose-dependent manner (H. Räägel, unpublished data). On the other hand, inside endosomes where the acidification process is not hampered, the peptide might be rapidly degraded, the complex compromised, and the necessary clustering jeopardized causing no such effect to be evoked. The question, however, as to whether the CPPs themselves assist in hindering the drop in pH, e.g., by (i) destabilizing the endosomal membrane via formation of transient pores [47] and thus preventing the concentration of protons inside these vesicles, or (ii) via deactivating the proton pumps by interfering with their activity, still remains unanswered. Additionally, some endocytic pathways, for example the caveolin-mediated endocytosis [53, 54], may lead to the collection of endosome-confined material into neutral intracellular vesicles, and as the uptake of TP10-protein complexes depends highly on the presence of caveolin-mediated pathway, as shown in experiments with caveolin1-depleted and knock-out cells [6], this possibility should be analyzed further.

Irrespective of the mechanism, we have previously shown that CPP-protein complexes form a subpopulation of endosomes that are not subjected to the decrease of pH in the endosomal environment even up to 12 h of chase period [55]. Thus, these same large non-acidic endosomes packed with a high amount of the complexes could be the ones that are becoming leaky and releasing the cargo into the cytosol. Since SA tends to remain in its native tetrameric form inside the cells for at least 12 h (Fig. 4), this could as well be the case. To further support this speculation, we performed an experiment with a biofunctional cargo protein where we showed that tubulin released from the endosomes remains intact and was efficiently incorporated into tubular structures inside the treated cells.

It would be an interesting (but also a demanding) challenge to further monitor and characterize the specific endosomes responsible for the photo-induced endosomal escape, for instance, to determine the major route of endocytosis contributing to the formation of these large non-acidic photo-inducible endosomes. As we have previously speculated that caveolin-mediated endocytosis may play a significant role in the creation of these large near-neutral vesicles packed with CPP-protein complexes [55], this will be the next step in our investigation. Yet the contribution of different lipids to the submersion of the peptide into the endosomal membrane introduces another interesting aspect to the study. Furthermore, the applicability of this technique for in vivo use should be determined to define (i) the efficacy of photo-induction in tissue conditions as well as (ii) the maximum depth of successful endosomal escape there. The wavelength used for in vivo photo-induction depends highly on the target and application. Most of the photodynamic therapies (PDT) use longer-wavelength (>630-nm) laser applications [56, 57] due to deeper penetration ability [58] and lower tissue scattering and absorption of the used light at those wavelengths. For these reasons, longer wavelengths should be preferred. However, when only surface (e.g., skin) treatments are desired, the more efficient (545–580 nm) excitation would be a better choice. Hopefully, future experiments will help to elaborate on these issues.

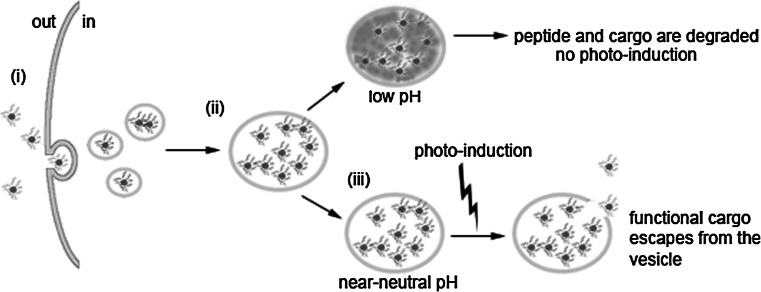

In conclusion, we report here some of the key determinants for an effective photo-induced endosomal escape of CPP-protein complexes, which are depicted in Fig. 6. First, excess peptide associating with the cargo is required for the cytosolic release of the cargo molecule. Second, a prolonged intracellular trafficking “prepares” the endosome for destabilization by gathering enough complexes (and peptide) and becoming a large, non-acidic vesicle with a predisposition to leakiness. Since leakage occurs from non-acidic endosomes, the cargo remains intact and bioactive/functional inside the cytosol of the treated cells. Due to a relatively feasible application of the photo-induction technique, we propose that this method in combination with the CPP-mediated delivery could be an efficient and harmless way to elevate the amount of bioactive cargo reaching its intracellular targets and serve as an alternative strategy in parallel to endosomolytic peptide sequences. Moreover, it allows a spatially restricted and thus a relatively selective approach to effective drug delivery.

Fig. 6.

Model for photo-induced endosomal escape. The cargo protein in complex with excess peptide (i) enters the cell via endocytosis and over time concentrates to larger intracellular vesicles (ii). Inside vesicles that do not acidify, the peptide is able to remodel the endosomal membrane leading to its destabilization upon photo-induction (iii). This results in the escape of the cargo into cytosol, where it is intact and functional

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 4 (MPEG 18752 kb)

Supplementary material 5 (TIFF 11617 kb)

Supplementary material 8 (TIFF 21155 kb)

Supplementary material 11 (TIFF 8186 kb)

Supplementary material 12 (TIFF 6409 kb)

Supplementary material 13 (TIFF 2800 kb)

Supplementary material 14 (TIFF 7591 kb)

Supplementary material 15 (TIFF 2407 kb)

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by grants from the Estonian Science Foundation (ESF 7058 and 8705) and the Estonian Ministry of Education and Research (0182691s05, 0180019s11, and 0180027s08). Ü. L. was also supported by the Swedish Research Council (VR-NT); by the Center for Biomembrane Research, Stockholm; by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg’s Foundation; by the EU through the European Regional Development Fund through the Center of Excellence in Chemical Biology, Estonia. H. R. was supported by Olev and Talvi Maimets Stipend (Foundation of the University of Tartu) and Artur Lind Stipend (Estonian Genome Foundation). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

- TP10

Transportan 10, a shortened analogue of transportan (TP)

- TP10b(N)

N-terminally biotinylated TP10

- SA

Streptavidin

- NA

Neutravidin

- Av

Avidin

- TxR

Texas Red

Contributor Information

Helin Räägel, Email: raagel@mpi-cbg.de.

Margus Pooga, Phone: +372-7-375049, FAX: +372-7-420286, Email: mpooga@ebc.ee.

References

- 1.Mäe M, Langel Ü. Cell-penetrating peptides as vectors for peptide, protein and oligonucleotide delivery. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6(5):509–514. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Järver P, Mäger I, Langel Ü. In vivo biodistribution and efficacy of peptide mediated delivery. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31(11):528–535. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris MC, Deshayes S, Heitz F, Divita G. Cell-penetrating peptides: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutics. Biol Cell. 2008;100(4):201–217. doi: 10.1042/BC20070116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Margus H, Padari K, Pooga M. Cell-penetrating peptides as versatile vehicles for oligonucleotide delivery. Mol Ther. 2012;20(3):525–533. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fotin-Mleczek M, Fischer R, Brock R. Endocytosis and cationic cell-penetrating peptides–a merger of concepts and methods. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11(28):3613–3628. doi: 10.2174/138161205774580778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Säälik P, Padari K, Niinep A, Lorents A, Hansen M, Jokitalo E, Langel Ü, Pooga M. Protein delivery with transportans is mediated by caveolae rather than flotillin-dependent pathways. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20:877–887. doi: 10.1021/bc800416f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Räägel H, Säälik P, Pooga M. Peptide-mediated protein delivery-which pathways are penetrable? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1798(12):2240–2248. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lundberg M, Wikström S, Johansson M. Cell surface adherence and endocytosis of protein transduction domains. Mol Ther. 2003;8(1):143–150. doi: 10.1016/S1525-0016(03)00135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abes S, Williams D, Prevot P, Thierry A, Gait MJ, Lebleu B. Endosome trapping limits the efficiency of splicing correction by PNA-oligolysine conjugates. J Control Release. 2006;110(3):595–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner JJ, Ivanova GD, Verbeure B, Williams D, Arzumanov AA, Abes S, Lebleu B, Gait MJ. Cell-penetrating peptide conjugates of peptide nucleic acids (PNA) as inhibitors of HIV-1 Tat-dependent trans-activation in cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(21):6837–6849. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wadia JS, Stan RV, Dowdy SF. Transducible TAT-HA fusogenic peptide enhances escape of TAT-fusion proteins after lipid raft macropinocytosis. Nat Med. 2004;10(3):310–315. doi: 10.1038/nm996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guterstam P, Madani F, Hirose H, Takeuchi T, Futaki S, El-Andaloussi S, Gräslund A, Langel Ü. Elucidating cell-penetrating peptide mechanisms of action for membrane interaction, cellular uptake, and translocation utilizing the hydrophobic counter-anion pyrenebutyrate. Biochemica et Biophysica Acta. 2009;1778:2509–2517. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Taei S, Penning NA, Simpson JC, Futaki S, Takeuchi T, Nakase I, Jones AT. Intracellular traffic and fate of protein transduction domains HIV-1 TAT peptide and octaarginine. Implications for their utilization as drug delivery vectors. Bioconjug Chem. 2006;17(1):90–100. doi: 10.1021/bc050274h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Padari K, Säälik P, Hansen M, Koppel K, Raid R, Langel Ü, Pooga M. Cell transduction pathways of transportans. Bioconjug Chem. 2005;16(6):1399–1410. doi: 10.1021/bc050125z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abes S, Moulton HM, Clair P, Prevot P, Youngblood DS, Wu RP, Iversen PL, Lebleu B. Vectorization of morpholino oligomers by the (R-Ahx-R)4 peptide allows efficient splicing correction in the absence of endosomolytic agents. J Control Release. 2006;116(3):304–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maiolo JR, 3rd, Ottinger EA, Ferrer M. Specific redistribution of cell-penetrating peptides from endosomes to the cytoplasm and nucleus upon laser illumination. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126(47):15376–15377. doi: 10.1021/ja044867z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selbo PK, Weyergang A, Hogset A, Norum OJ, Berstad MB, Vikdal M, Berg K. Photochemical internalization provides time- and space-controlled endolysosomal escape of therapeutic molecules. J Control Release. 2010;148(1):2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shiraishi T, Nielsen PE. Photochemically enhanced cellular delivery of cell-penetrating peptide-PNA conjugates. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(5):1451–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang JT, Giuntini F, Eggleston IM, Bown SG, Macrobert AJ. Photochemical internalisation of a macromolecular protein toxin using a cell-penetrating peptide-photosensitiser conjugate. J Control Release. 2012;157(2):305–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Andaloussi S, Johansson H, Magnusdottir A, Järver P, Lundberg P, Langel Ü. TP10, a delivery vector for decoy oligonucleotides targeting the Myc protein. J Control Release. 2005;110(1):189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yandek LE, Pokorny A, Florén A, Knoelke K, Langel Ü, Almeida PF. Mechanism of the cell-penetrating peptide transportan 10 permeation of lipid bilayers. Biophys J. 2007;92(7):2434–2444. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.100198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunkin CM, Pokorny A, Almeida PF, Lee HS. Molecular dynamics studies of transportan 10 (Tp10) interacting with a POPC lipid bilayer. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115(5):1188–1198. doi: 10.1021/jp107763b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Säälik P, Niinep A, Pae J, Hansen M, Lubenets D, Langel Ü, Pooga M. Penetration without cells: membrane translocation of cell-penetrating peptides in the model giant plasma membrane vesicles. J Control Release. 2011;153(2):117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holm T, Johansson H, Lundberg P, Pooga M, Lindgren M, Langel Ü. Studying the uptake of cell-penetrating peptides. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(2):1001–1005. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Makarava N, Baskakov IV. The same primary structure of the prion protein yields two distinct self-propagating states. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(23):15988–15996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800562200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El Moustaine D, Perrier V, Van Ba Acquatella-Tran I, Meersman F, Ostapchenko VG, Baskakov IV, Lange R, Torrent J. Amyloid features and neuronal toxicity of mature prion fibrils are highly sensitive to high pressure. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(15):13448–13459. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.192872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ter-Avetisyan G, Tünnemann G, Nowak D, Nitschke M, Herrmann A, Drab M, Cardoso MC. Cell entry of arginine-rich peptides is independent of endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(6):3370–3378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805550200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rydström A, Deshayes S, Konate K, Crombez L, Padari K, Boukhaddaoui H, Aldrian G, Pooga M, Divita G. Direct translocation as major cellular uptake for CADY self-assembling peptide-based nanoparticles. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e25924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bode SA, Thevenin M, Bechara C, Sagan S, Bregant S, Lavielle S, Chassaing G, Burlina F. Self-assembling mini cell-penetrating peptides enter by both direct translocation and glycosaminoglycan-dependent endocytosis. Chem Commun (Camb) 2012;48(57):7179–7181. doi: 10.1039/c2cc33240j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rothbard JB, Jessop TC, Lewis RS, Murray BA, Wender PA. Role of membrane potential and hydrogen bonding in the mechanism of translocation of guanidinium-rich peptides into cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126(31):9506–9507. doi: 10.1021/ja0482536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tünnemann G, Martin RM, Haupt S, Patsch C, Edenhofer F, Cardoso MC. Cargo-dependent mode of uptake and bioavailability of TAT-containing proteins and peptides in living cells. FASEB J. 2006;20(11):1775–1784. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5523com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Srinivasan D, Muthukrishnan N, Johnson GA, Erazo-Oliveras A, Lim J, Simanek EE, Pellois JP. Conjugation to the cell-penetrating peptide TAT potentiates the photodynamic effect of carboxytetramethylrhodamine. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dixit R, Cyr R. Cell damage and reactive oxygen species production induced by fluorescence microscopy: effect on mitosis and guidelines for non-invasive fluorescence microscopy. Plant J. 2003;36(2):280–290. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munoz-Morris MA, Heitz F, Divita G, Morris MC. The peptide carrier Pep-1 forms biologically efficient nanoparticle complexes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;355(4):877–882. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eiriksdottir E, Mäger I, Lehto T, El Andaloussi S, Langel Ü. Cellular internalization kinetics of (luciferin-)cell-penetrating peptide conjugates. Bioconjug Chem. 2010;21(9):1662–1672. doi: 10.1021/bc100174y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ziegler A, Nervi P, Dürrenberger M, Seelig J. The cationic cell-penetrating peptide CPP(TAT) derived from the HIV-1 protein TAT is rapidly transported into living fibroblasts: optical, biophysical, and metabolic evidence. Biochemistry. 2005;44(1):138–148. doi: 10.1021/bi0491604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jain RK. Barriers to drug delivery in solid tumors. Sci Am. 1994;271(1):58–65. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0794-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tannock IF, Lee CM, Tunggal JK, Cowan DS, Egorin MJ. Limited penetration of anticancer drugs through tumor tissue: a potential cause of resistance of solid tumors to chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(3):878–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foldvari M, Babiuk S, Badea I. DNA delivery for vaccination and therapeutics through the skin. Curr Drug Deliv. 2006;3(1):17–28. doi: 10.2174/156720106775197493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gillmeister MP, Betenbaugh MJ, Fishman PS. Cellular trafficking and photochemical internalization of cell-penetrating peptide linked cargo proteins: a dual fluorescent labeling study. Bioconjug Chem. 2011;22(4):556–566. doi: 10.1021/bc900445g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Almeida PF, Pokorny A. Mechanisms of antimicrobial, cytolytic, and cell-penetrating peptides: from kinetics to thermodynamics. Biochemistry. 2009;48(34):8083–8093. doi: 10.1021/bi900914g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang HW. Molecular mechanism of antimicrobial peptides: the origin of cooperativity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758(9):1292–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Herce HD, Garcia AE. Molecular dynamics simulations suggest a mechanism for translocation of the HIV-1 TAT peptide across lipid membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(52):20805–20810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706574105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herce HD, Garcia AE, Litt J, Kane RS, Martin P, Enrique N, Rebolledo A, Milesi V. Arginine-rich peptides destabilize the plasma membrane, consistent with a pore formation translocation mechanism of cell-penetrating peptides. Biophys J. 2009;97(7):1917–1925. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang ST, Zaitseva E, Chernomordik LV, Melikov K. Cell-penetrating peptide induces leaky fusion of liposomes containing late endosome-specific anionic lipid. Biophys J. 2010;99(8):2525–2533. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salamon Z, Lindblom G, Tollin G. Plasmon-waveguide resonance and impedance spectroscopy studies of the interaction between penetratin and supported lipid bilayer membranes. Biophys J. 2003;84(3):1796–1807. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74987-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anko M, Majhenc J, Kogej K, Sillard R, Langel U, Anderluh G, Zorko M. Influence of stearyl and trifluoromethylquinoline modifications of the cell-penetrating peptide TP10 on its interaction with a lipid membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1818(3):915–924. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gruenberg J. Lipids in endocytic membrane transport and sorting. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15(4):382–388. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(03)00078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kobayashi T, Beuchat MH, Chevallier J, Makino A, Mayran N, Escola JM, Lebrand C, Cosson P, Gruenberg J. Separation and characterization of late endosomal membrane domains. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(35):32157–32164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202838200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cardoso AM, Trabulo S, Cardoso AL, Lorents A, Morais CM, Gomes P, Nunes C, Lucio M, Reis S, Padari K, Pooga M, Pedroso de Lima MC, Jurado AS. S4(13)-PV cell-penetrating peptide induces physical and morphological changes in membrane-mimetic lipid systems and cell membranes: implications for cell internalization. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1818(3):877–888. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alves ID, Goasdoue N, Correia I, Aubry S, Galanth C, Sagan S, Lavielle S, Chassaing G. Membrane interaction and perturbation mechanisms induced by two cationic cell-penetrating peptides with distinct charge distribution. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1780(7–8):948–959. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mishra A, Lai GH, Schmidt NW, Sun VZ, Rodriguez AR, Tong R, Tang L, Cheng J, Deming TJ, Kamei DT, Wong GC. Translocation of HIV TAT peptide and analogues induced by multiplexed membrane and cytoskeletal interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(41):16883–16888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108795108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parton RG, Richards AA. Lipid rafts and caveolae as portals for endocytosis: new insights and common mechanisms. Traffic. 2003;4(11):724–738. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nabi IR, Le PU. Caveolae/raft-dependent endocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2003;161(4):673–677. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Räägel H, Säälik P, Hansen M, Langel Ü, Pooga M. CPP-protein constructs induce a population of non-acidic vesicles during trafficking through endo-lysosomal pathway. J Control Release. 2009;139(2):108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang Z. A review of progress in clinical photodynamic therapy. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2005;4(3):283–293. doi: 10.1177/153303460500400308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morton CA, McKenna KE, Rhodes LE. Guidelines for topical photodynamic therapy: update. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(6):1245–1266. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Juzeniene A, Juzenas P, Ma LW, Iani V, Moan J. Effectiveness of different light sources for 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy. Lasers Med Sci. 2004;19(3):139–149. doi: 10.1007/s10103-004-0314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 4 (MPEG 18752 kb)

Supplementary material 5 (TIFF 11617 kb)

Supplementary material 8 (TIFF 21155 kb)

Supplementary material 11 (TIFF 8186 kb)

Supplementary material 12 (TIFF 6409 kb)

Supplementary material 13 (TIFF 2800 kb)

Supplementary material 14 (TIFF 7591 kb)

Supplementary material 15 (TIFF 2407 kb)