Abstract

The acquisition of genomic instability is a triggering factor in cancer development, and common fragile sites (CFS) are the preferential target of chromosomal instability under conditions of replicative stress in the human genome. Although the mechanisms leading to CFS expression and the cellular factors required to suppress CFS instability remain largely undefined, it is clear that DNA becomes more susceptible to breakage when replication is impaired. The models proposed so far to explain how CFS instability arises imply that replication fork progression along these regions is perturbed due to intrinsic features of fragile sites and events that directly affect DNA replication. The observation that proteins implicated in the safe recovery of stalled forks or in engaging recombination at collapsed forks increase CFS expression when downregulated or mutated suggests that the stabilization and recovery of perturbed replication forks are crucial to guarantee CFS integrity.

Keywords: Genome instability, Replication fork arrest, Replication checkpoint, Werner syndrome protein, Common fragile sites

Introduction

Common fragile sites (CFS) are normal components of the human genome unusually prone to DNA breakage [1]. They have been proposed to be susceptible to DNA instability in cancer cells, and mutation at these loci may have a causative role in cancer development [2]. Although a direct involvement of CFS in cancer has not yet been recognized, a correlation between fragile regions and chromosomal aberrations found in tumor cells has been previously reported [3–6]. The majority of the chromosomal abnormalities occurring in cancer cells may originate from defective DNA replication. Given the large size of the mammalian genomes, DNA replication is a process that is tightly monitored; however, several challenges can threaten genome integrity by interfering with progression, stability, and proper resumption of replication after fork arrest [7]. Thus, defects of DNA replication or failure to restart stalled forks can lead to accumulation of mutations and genomic aberrations [7]. In the human genome, CFS are difficult-to-replicate regions particular sensitive to replication stress leading to frequent events of fork stalling. Mounting evidence suggests that several proteins of the replication stress response influence CFS stability, corroborating the hypothesis that the fragility of these regions derives from stalled forks or incomplete replication. Therefore, maintenance of genome stability at these loci relies on an accurate response to replication stress. The link between replication defects and CFS instability will be discussed, giving details on the mechanisms operating in eukaryotic cells to promote replication fork integrity and how they can contribute to maintaining CFS stability.

Multiple factors underlying CFS instability

CFS are loci generally stable in normal cells cultured under standard growth conditions, which display gaps and breaks on metaphase chromosomes upon low levels of replication stress (see B. Kerem, this issue). Although CFS are defined as sites, they are large genomic regions, spanning hundreds to thousands of kilobases, which possess common features but show often different chromosome localizations in different cell types or tissues [8]. All the inducers of CFS can potentially stop elongation of DNA replication, thus only concentrations that partially inhibit replication without arresting the cell cycle can lead to CFS expression [9, 10]. About 80 CFS have been identified so far, but not all are expressed at the same frequency and may present different cell-type-specific sensitivity [11, 12].

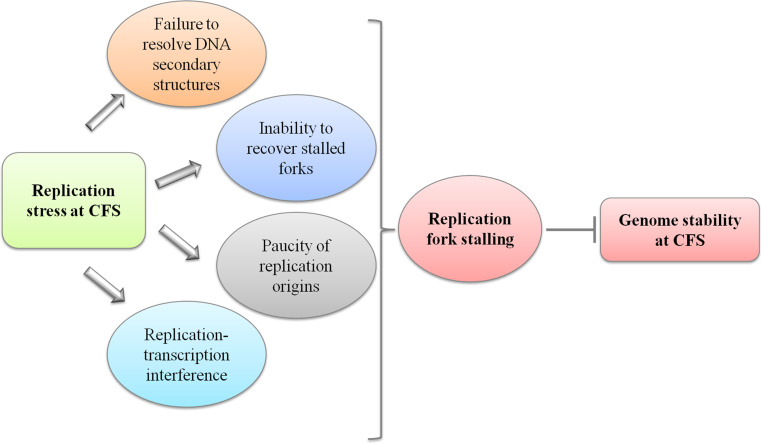

While the molecular basis of CFS instability still remains elusive, several factors may contribute to the fragility of these regions (Fig. 1). Computational studies proposed that AT-rich sequences of CFS may perturb DNA replication because of their ability to adopt complex secondary structures, which could confer on these sites the tendency of fork stalling or replication elongation perturbation [13, 14]. An indirect evidence that such sequences may perturb DNA replication because of their potential ability to adopt complex structures has been provided by in vivo studies in a yeast system [15]. In that study, an AT-rich region within the fragile site, FRA16D, was predicted to have high flexibility and to form cruciform DNA, determined replication fork stalling, and increased chromosome breakage, mimicking what might happen at human CFS, also independently from replication stress. This is the first demonstration that links a sequence element within a CFS with replication fork arrest and chromosome breakage;, however, the most convincing, but yet indirect, proof that intrinsic features of a CFS sequence are associated with breakage at fragile regions is provided by the observation that a stable ectopic integration of FRA3B into non-fragile loci recapitulates the CFS-like phenotype [16]. Interestingly, this hypothesis has been proven by electron microscopy analysis in human cells transfected with FRA16B-containing constructs. That study revealed a propensity of the FRA16B replication fork template to promote spontaneous fork reversal and DNA polymerase pausing at specific sites within the FRA16B region, suggesting that the secondary structure-forming ability of FRA16B contributes to its fragility by stalling DNA replication [17]. Overall, these observations confirm that generation of stable secondary structures may be a general mechanism accounting for the fragility of CFS during DNA replication.

Fig. 1.

General scheme of the potential sources of replication stress at CFS. Multiple factors can threaten DNA replication contributing to replication perturbation, and all the proposed causes implicate the requirement of a replication recovery mechanism to avoid CFS instability

Apart from an involvement of DNA secondary structures in determining CFS instability, a role for replication origin density has been described, and the idea that CFS expression is epigenetically defined has been proposed [12]. According to that study, fragility of the human FRA3B fragile site in lymphoblastoid cells, but not in fibroblasts, is due to a scarcity of initiation events, which forces forks coming from flanking regions to cover long distances to finish replication. Treatment of the cells with aphidicolin, an inhibitor of replicative DNA polymerases and the most potent inducer of CFS expression at low doses [1], leads to reduction of replication fork velocity. Consequently, replication along CFS risks remaining partial, resulting in unreplicated regions which show a remarkable propensity to breakage respect to the rest of the genome [12]. Moreover, it has also been proposed that commitment to fragile site instability in different cell types depends on the same paucity of origins, but different chromosomal regions are committed [11]. Thus, the scarcity of origins within FRA3B in combination with it being a late-replicating region could be responsible for the incomplete replication of the site at G2/M, leading to its elevated susceptibility to breakage.

Of interest, a direct demonstration of fork stalling along an endogenous human fragile site has been provided [18]. Indeed, along the human FRA16C region, high levels of fork stalling close to the AT-rich sequences are observed, clearly indicating that replication is intrinsically perturbed. Moreover, although replication stress further enhances fork stalling, most of the origins are already activated under unperturbed conditions, thus CFS are not able to compensate for replication stress resulting in wide unreplicated regions more sensitive to breakage [18]. Consistent with that study, the analysis of the replication dynamics of FRA6E, that contains long AT-rich sequences, also showed a slower replication rate along the site, a shorter inter-origins distance, and a higher frequency of replication fork arrest with respect to the rest of the genome [19]. These studies suggest that both paucity of replication origins and fork arrest can contribute to the destabilization of the FRA16C and FRA6E regions.

More recently, collision between replication and transcription complexes has also been considered a potential source of CFS instability, due to the ability of stable R-loops to impede replication fork progression [20]. Since not all the fragile sites co-localize with very large genes, this mechanism can only explain the fragility of some of them. Furthermore, a study suggests that replication forks travel similarly along CFS and are genome-wide, leading to the conclusion that R-loop formation cannot be the prevalent way to affect fork movement [11].

Collectively, all these findings clearly indicate that, although distinct replication features may explain the instability of different fragile sites, replication fork progression along these loci is perturbed, and raise the possibility that maintenance of genome stability depends on an accurate response to replication stress.

Proteins of the ATR-pathway play a crucial role in the maintenance of CFS stability

DNA breakage at CFS is considered a symptom of replication stress [21, 22]. Supporting the hypothesis that instability at CFS derives from stalled forks or incomplete replication, several proteins of the replication stress response influence CFS expression. To deal with problems encountered during S-phase, cells are equipped with specialized pathway: the replication checkpoint, which is a complex and coordinated network under the control of the ATR kinase [23, 24]. The main function of the ATR-dependent checkpoint is to monitor S-phase completion. In the case of replication stress, its activation leads to inhibition of origin firing, cell cycle arrest, stabilization, and then restart of stalled forks, and prevention of the entry into mitosis until the DNA has been completely replicated [25]. Notably, CFS stability appears to depend on checkpoint activity. A first correlation between the replication checkpoint and CFS has been provided by the observation that ATR disruption or hypomorphic mutation dramatically and specifically affects the fragility of CFS, even in the absence of aphidicolin [26, 27]. Interestingly, the fact that ATR deficiency alone results in CFS expression clearly suggests that replication fork stalling may occur spontaneously at these regions, and that many causes can arrest replication forks during the normal replication. Altogether, these findings demonstrate that ATR plays an important function in response to fork stalling arising at CFS. In the same way, inactivation of Mec1, the yeast ATR homolog, elicits persistent fork stalling at the replication slow zones, an example of fragile sites in yeast, leading to chromosome breaks at these loci [28]. The model that explains how ATR prevents instability at CFS proposes that in normal cells fragile sites are single-stranded (ssDNA), unreplicated, regions derived from stalled or collapsed forks upon replication stress. When some of the ssDNA regions escape checkpoint, CFS are expressed [27].

As a logical extension of previous findings, several factors of the ATR-pathway and ATR substrates have been shown to contribute to CFS stability (Table 1) [29, 30]. Among them, CHK1 is a key kinase whose phosphorylation serves as a signal for the activation of the ATR-dependent checkpoint [31]. Post-translational modifications of CHK1 play a role in suppressing late replication origin firing and maintain fork integrity [32–34]. Reduced CHK1 activity has been associated with accumulation of ssDNA [35], impaired replication fork progression [33], and increased fork stalling [34]. Interestingly, upon replication perturbation at CFS, both CHK1 and CHK2 were activated, but only depletion of CHK1 induces CFS expression [36]. The elevated chromosome instability observed in the absence of CHK1 might be explained by its proposed role in maintaining replication fork integrity upon replication stress, and the high CFS expression may be due to loss of replication checkpoint function after fork stalling.

Table 1.

Proteins of the ATR-pathway involved in the maintenance of CFS stability

| Protein | Description of the function | References |

|---|---|---|

| CHK1 | Apical kinase, deputed to the ATR-pathway activation | Durkin and Glover [9] |

| HUS1 | Member of the 9.1.1 complex, promotes phosphorylation of ATR-substrates | Zhu and Weiss [38] |

| CLASPIN | Upstream regulator of CHK1 activation | Focarelli et al. [37] |

| SMC1 | Component of the cohesion complex, contributes to the replication checkpoint activation | Musio et al. [41] |

| WRN | RecQ helicase family member, ATR-target implicated in replication fork recovery | Pirzio et al. [49]; Shah et al. [93] |

Downregulation of two other upstream regulators of CHK1 activation in response to replication stress significantly affects CFS stability: Claspin and HUS1, a component of the RAD9/RAD1/HUS1 (9.1.1) complex [37, 38]. After replication stress, the phosphorylation ATR-dependent Claspin allows the interaction with CHK1 and its subsequent activation. Studies from the yeast model suggest that the Claspin homolog Mrc1 may be involved in the stabilization of the replisome, by counteracting fork stalling at DNA secondary structures [39]. Loss of Mrc1 causes fork collapse, accumulation of ssDNA, and then Rad9 activation to trigger checkpoint signaling and allow efficient restart of DNA synthesis [39]. It is plausible that, as reported in yeast, in human cells Claspin could contribute to dealing with the potential DNA secondary structures formed at CFS, which would hinder replication fork progression leading to fork collapse. Furthermore, since, in response to replication arrest, RAD9 regulates the S-phase checkpoint activation by mediating CHK1 phosphorylation [40], loss of HUS1, which leads to the disruption of the whole complex, might result in the loss of the checkpoint signal and then of the correct restart of DNA synthesis.

Besides its role in sister chromatid cohesion, the structural maintenance of chromosomes 1 (SMC1) is phosphorylated in an ATR-dependent manner under conditions of replication stress, and has been implicated in the maintenance of CFS integrity [41]. Notably, SMC1 shows a preferential binding affinity for DNA secondary structures and a strong preference for AT-rich sequences [42]. Thus, SMC1 might contribute to the activation of the ATR-checkpoint upon replication perturbation at CFS, probably allowing error-free recovery of DNA replication [40, 41].

Interestingly, maintenance of CFS stability requires the collaboration of ATR and another of their targets, the Werner syndrome protein, WRN [43–45]. Indeed, WRN, a member of the RecQ family of DNA helicases, appears to be essential for fruitful rescue from replication fork arrest [46–48], and it is the first protein involved in this process to be correlated with instability at CFS [49].

Therefore, if replication checkpoint functions are somewhat impaired, then the entire pathway is probably inactivated and recovery of stalled forks compromised. As a consequence, fork collapse and the inability to accurately replicate through fragile sites might occur.

Mechanisms of replication fork recovery

As anticipated earlier on, replication through CFS may occur less smoothly than in other non-fragile regions of chromosomes. Thus, more replication forks could become delayed and stall resulting in more need for recovery. Even though fork stalling could be easily overcome by passive replication from a convergent fork because of the redundancy in number of potential replication origins, higher eukaryotes, including mammalian cells, also possess several independent mechanisms that allow restart of replication from stalled forks. Such replication fork recovery mechanisms are particularly important whenever passive replication is not possible, for instance in the absence of nearby origins, as it could occur at some CFS, or at telomeres and when there are replication fork barriers, such as in the rDNA. In all those instances, completion of replication is expected to depend on the ability to stabilise stalled forks and activate their recovery.

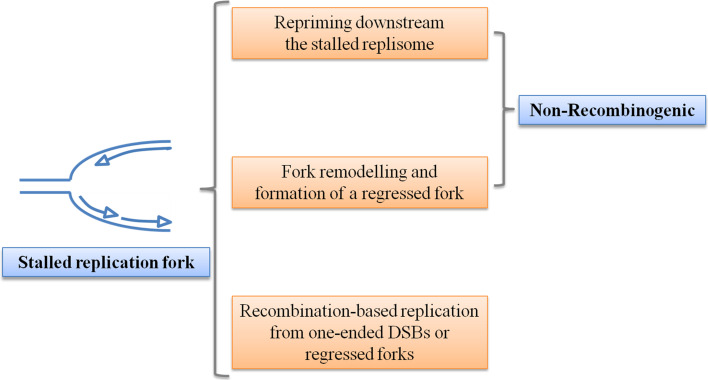

As a rule of thumb, mechanisms involved in replication fork recovery can be grouped in two: those depending on direct restart of the fork and those being recombination-dependent (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Pathways by which DNA replication can reinitiate after replication fork arrest. Upon stalling of a replication fork, DNA synthesis can be reinitiated through three different mechanisms (from top to bottom): replication can be restarted by repriming downstream of the site of stalling; alternatively, specialized enzymes, such as DNA translocases and helicases, are recruited to remodel the DNA at stalled forks to produce a regressed fork, which is used to protect ssDNA at the site of fork stalling and to restore a functional replication fork; finally, replication can be resumed using recombination from either collapsed forks, after production of one-ended DSBs, or from the regressed replication fork (see text for details). Perturbation of replication at CFS most probably engages a non-recombinogenic pathway of fork restart

The direct restart of the fork has been originally demonstrated in bacteria, and requires the PriA and PriC proteins [50, 51]. Even if homologs of PriA and PriC have not been found in eukaryotes, indirect evidence of the presence of a similar mechanisms in higher eukaryotes does exist. Using Xenopus extracts, it has been demonstrated that Polα primase, which is essential for initiation and elongation of DNA synthesis, can also be recruited at ssDNA regions formed after replication fork stalling through a mechanism that requires it [52]. Whether the Polα primase can also be recruited at ssDNA regions accumulating after fork arrest in human cells is not known; however, a very recent paper demonstrated that loss of MCM10 leads to replication stress and CFS instability [53]. Interestingly, Polα primase interacts with MCM10 during initiation and elongation [54]. Furthermore, whether MCM10-dependent stabilization of CFS, that are difficult-to-replicate loci in humans, is directly related to the loss of Polα primase-mediated fork restart or rather is simply a consequence of impaired leading-strand synthesis is currently unknown. However, at least in WRN-deficient cells, perturbation of replication at CFS leads very rapidly to accumulation of ssDNA gaps [55], which could imply that stalled forks become inactive in the absence of WRN, possibly requiring downstream re-initiation of replication. Whether or not Polα primase is involved in direct replication resumption in human cells, restart of DNA synthesis after replication forks arrest has been envisaged to occur.

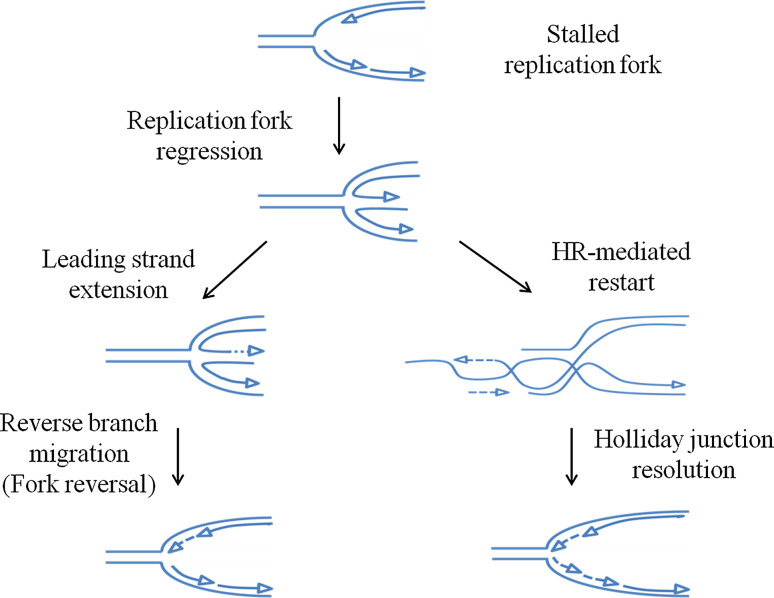

Intriguingly, the ability to promptly restart replication at stalled forks has been shown to rely on a DSB-independent, and perhaps recombination-independent, function of RAD51 [56]. How RAD51 exerts this function is unclear, but one possibility is that RAD51 may shield ssDNA formed at stalled forks, contributing to their stabilization in a structure that allows resumption of the DNA synthesis once the cause of the stalling is eliminated. As for direct restart mediated by Polα primase, it is not known if RAD51-mediated fork stabilization is implicated in fork restart at CFS as it seems to be after genome-wide fork arrest. Both Polα primase-mediated or RAD51-dependent fork restart could take place without the need of extensive fork remodeling. However, direct recombination-independent fork resumption more likely involves processing of the stalled fork by dedicated enzymes to form an intermediate that more easily supports replisome restoration. In bacteria, this intermediate is the regressed fork or chicken foot that is formed through the RecG-mediated extrusion and pairing of nascent strands [57, 58]. The outcome of this reaction is protection of ssDNA and formation of a structure that is equivalent to a Holliday junction (HJ), which can be further processed to restore a fork-like intermediate where the replisome can be reassembled or repositioned (Fig. 3). The regressed fork is a very versatile structure because, if further remodeling to restore a fork fails, it can be used for recombination-based fork recovery.

Fig. 3.

The replication fork regression is a versatile intermediate for replication restart. A stalled replication fork is characterized by formation of a ssDNA region ahead of the fork as a consequence of helicase–polymerase uncoupling. The need for stabilize and protect ssDNA determines the engagement of DNA translocases and/or helicases at the fork to regress the replisome, leading to extrusion of the nascent DNA strands and their pairing. The four-way DNA structure that forms, which is called the regressed fork or chicken foot, can be further reversed by branch migrating activities to restore a forked DNA or engaged in recombination-mediated replication restart. In this latter event, resolution of the D-loop formed behind the fork is required to support replisome reassembly

In bacteria, replication fork regression and reversal catalyzed by RecG is primarily used to replicate past an UV-induced DNA lesion, providing, at the same time, a dsDNA context to the lesion for nucleotide-excision repair. Whether fork regression does occur in higher eukaryotes, and in human cells in particular, is still uncertain, and it is still debated whether regressed forks are physiological or rather pathological structures accumulated because of a defective replication checkpoint, as has been proposed in yeast [59]. However, recent reports evidenced that regressed forks can also be observed in checkpoint-proficient human cells, especially after treatment with low doses of the TopoI inhibitor camptothecin, and in a number higher than expected for a pathological event [60]. The existence of regressed forks in human cells has stressed the search for a RecG homolog. A true RecG homolog has not yet been found in human cells; however, different enzymes seems to have, at least in vitro, the ability to regress stalled forks or to promote their reversal. For instance, fork regression can be carried out, at least in vitro, by the HTLF and SMARCAL1 translocases, by the WRN and BLM RecQ helicases, and by the FANCM protein [61–64]. Most of these proteins, such as WRN, BLM, and SMARCAL1, also have the ability to perform the fork restoration through reversal of regressed forks, thus regenerating the junction onto which replisome can be reassembled or where it can be repositioned for recovery of DNA synthesis. Strikingly, even though SMARCAL1 seems to be the ideal candidate for the regression and reversal of stalled forks in vitro [65], another RecQ member, RecQ1, has been nicely demonstrated to be essential for the fork reversal in human cells, in vivo, upon stimulation of fork reversal by low doses of camptothecin [66]. The presence of such a plethora of RecG orthologs in human cells suggests that replication fork reversal is crucial for the restart of stalled forks, and that the process is probably tightly regulated and with several alternatives. Indeed, at least SMARCAL1 and WRN seem to be regulated by ATR after replication arrest induced by HU [43, 67], and are found in a common complex [68].

Notably, restoration of a Y-like structure for replisome reloading can also be obtained by exonucleolytic degradation of the extruded nascent strands (Fig. 3). Kilobases-long degradation of nascent strands after replication fork perturbation has been reported in yeast and human cells, but as a pathological consequence of loss of checkpoint or recombination-mediated fork stabilisation, and would be mediated by EXO1 or MRE11 [69–71]. In contrast, and although speculative, it is unknown whether limited degradation at reversed forks is required for further fork remodeling and reversal. Stretches of ssDNA at the extruded DNA filaments of regressed forks have been observed by electronic microscopy under unperturbed replication or DNA damage [66, 70], suggesting that exonucleolytic degradation at regressed forks may indeed take place after fork arrest. However, the actual mechanism and the identity of the exonuclease(s) involved are still missing. Nevertheless, should degradation at regressed forks be a common event after fork restart, then it is likely that Exo1 and MRE11 are involved. Both EXO1 and MRE11 are 5′-3′ exonucleases, even though MRE11 has been reported to also induce 3′-5′ degradation, because it can nick-in the dsDNA and trim back from the nick. However, since 5′- or 3′- overhangs at the extruded nascent strands are probably equally represented in the population of regressed forks, other exonucleases with 3′-5′ polarity could be involved and work in parallel with MRE11 or EXO1. From this point of view, the most suitable enzyme to carry out the 3′-5′ degradation at the extruded strands of regressed forks might be the WRN protein, as its exonuclease and helicase activities have been proposed to act cooperatively during fork regression in vitro [72], and it interacts with MRE11 [73].

Does replication fork reversal occur at perturbed replication forks travelling through CFS? The nature of experiments required to directly clarify this point is challenging; however, the observed enrichment of RECQ1, a protein involved in reversal of regressed forks, at a subset of CFS [74], might be indicative of the formation of such structures after replication arrest at those loci. Restoration of a replication fork can also be accomplished by recombination. Requirement of recombination-mediated fork recovery is strikingly confined in human cells to specific circumstances, that is when other mechanisms fail or when a one-ended DSB is formed, for instance by replication through a ssDNA nick or gap. According to the classical model of break-induced replication (BIR) [75, 76], the one-ended DSB is trimmed to produce the substrate for the loading of recombination proteins, such as RAD52 and RAD51, and the subsequent strand invasion of the intact sister chromosome, providing the template DNA for replisome reloading and DNA extension. Recent studies using Xenopus extracts showed that not all the replisome components detach after formation of the one-ended DSB, but only the GINS helicase and Polymerase ε, which are reloaded through a mechanism requiring MRE11 and RAD51 [77]. Interestingly, recombination-mediated fork restart may also take place in the absence of a DSB. Indeed, as shown for replication fork barriers in yeast, RAD51-dependent strand invasion can start after fork regression and resection of the extruded arm. This mechanism would result in the formation of a D-loop, which can support reassembly of the replisome. The D-loop itself would undergo dissolution by the BLM/TopIII dissolvosome or endonucleolytic cleavage by the MUS81/EME1 resolvase, as occurs when the checkpoint is not functional [78].

Another recombination-mediated pathway that does not rely on formation of DSBs is the gap-filling or post-replication repair, which is thought to occur in response to the unreplicated gaps left behind stalled replication forks. The possibility of trying to complete replication passively from adjacent origins, typical of higher eukaryotes, suggests that this pathway may be prominent and substantially contribute to genome stability in vertebrates. According to most recent data, RAD51 can also be crucial for accurate post-replication repair, shielding such ssDNA gaps from being targeted by MRE11 and used for more error-prone mechanisms [70]. It is worth noting that, even though recombination-based replication is useful to overcome loss of viability next to replication stress, it is a mutagenic pathway. Indeed, the replisome assembled during BIR stimulates accumulation of large frameshifts, and may contribute to the generation of gross chromosomal rearrangements [79–81]. Similarly, template-switching initiated at unreplicated gaps behind the fork might introduce chromosomal rearrangements if occurring at inverted repeats. Moreover, accumulation of too many branched recombination intermediates, as a consequence of the attempt to perform post-replication gap repair at unreplicated regions, could stimulate, in G2 or early mitosis, endonucleolytic cleavage by resolvases such as MUS81, thus contributing to CFS expression [82–84].

The replication fork recovery mechanisms and the stability of CFS: lessons from the WRN RecQ helicase

As outlined above, several mechanisms have been put forward to explain fragility of CFS and the current view is that not all CFS are equivalent, and that multiple molecular causes underlie their fragility, included stalling or pausing of replication forks. In spite of the abundance of replication fork recovery mechanisms, as described in the previous section, it is likely that not all of them act when replication forks stall at CFS. Indeed, it is still unclear what happens to forks stalled at CFS and which pathways are preferentially engaged, even though data from analysis of CFS expression in cells deficient of given pathways have been illuminating. Perhaps, the two pieces of evidence clearly demonstrating that replication forks may stall at CFS and that CFS stability relies on correct replication fork recovery are the observed enhanced expression of CFS in cells deficient of the WRN RecQ helicase or knocked-down for the RAD51 recombinase [49, 85, 86].

WRN is one of the five human RecQ helicases and has been extensively linked to replication fork recovery [87]. It is a target of ATR/ATM and interacts with several checkpoint factors, such as the 9.1.1 complex [43, 88], which are recruited at stalled forks (for a review, see [7]). Loss of WRN results in reduced ability to replicate after DNA damage or replication arrest [43, 89] and increases chromosome damage. Even though WRN has also been shown to carry out a function during recombinational repair of DSBs [90], the primary function at perturbed forks seems to be unrelated to recombination [47] and is probably more linked to fork remodeling. Despite that WRN is both an exonuclease and an helicase, the helicase function is sufficient to ensure CFS stability [49]. Given the specific requirement of the WRN helicase activity for regulating CFS stability, and the high propensity of CFS to adopt DNA secondary structures during DNA replication [13, 14], it is possible that the helicase activity of WRN is necessary to the unwinding of these structures in order to facilitate replication fork progression or support fork restart. Indeed, WRN is involved in replication resumption after fork arrest induced by DNA damage or nucleotide depletion by HU [43, 91], and supports replication at CFS (Franchitto, unpublished). WRN could act in preventing the replisome disassembly or in the removal of DNA secondary structures that impede fork progression by its helicase activity, and its function could be regulated by the replication checkpoint. This is in agreement with the proposed coordinated action of WRN and DNA polymerase delta in the replication of DNA substrates containing G4-tetraplex structures [92, 93]. Since WRN deficiency recapitulates ATR defects in terms of CFS instability, it is likely that the ATR-mediated stabilization of stalled forks may be basically carried out through phosphorylation and regulation of WRN by ATR.

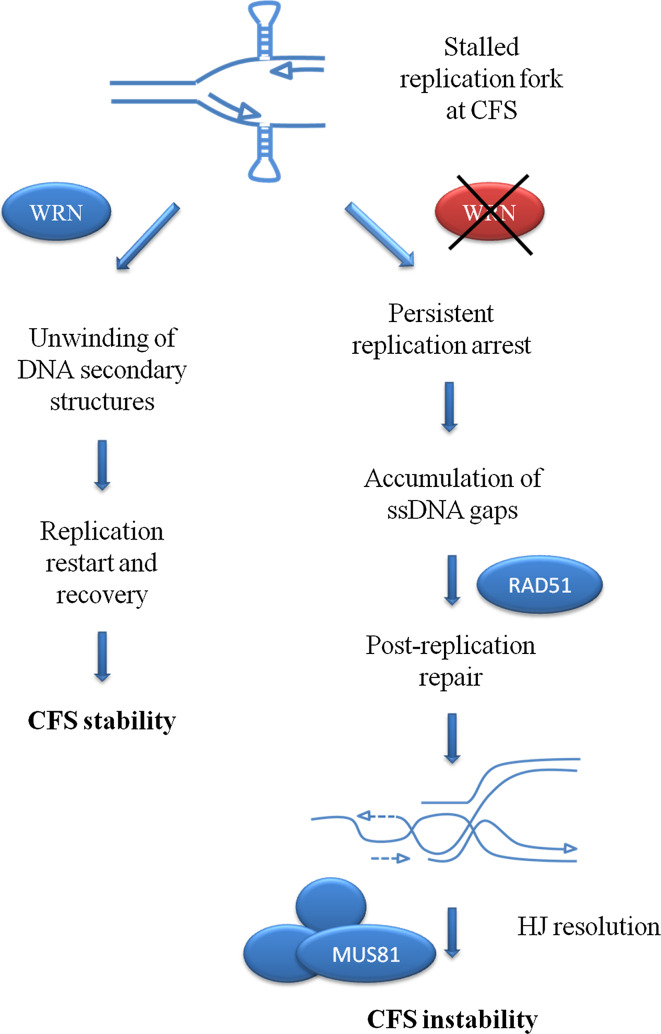

If the crucial role of WRN in maintaining integrity of CFS is to allow fork restart, the function of RAD51 seems unlikely to correlate with repair of DSBs after fork collapse. Indeed, perturbation of replication at CFS does not produce detectable DSBs at early time-points [55], arguing against the occurrence of fork collapse and requirement of BIR. Rather, RAD51 could function to protect fork stalled at CFS from exonucleolytic degradation, as shown after nucleotide depletion [70, 71], or to perform the post-replication gap repair behind the fork when replication resumption at CFS failed. Unfortunately, RAD51 depletion in human cells results in genome-wide accumulation of DSBs making it difficult to assess directly whether loss of RAD51-mediated protection at fork specifically induces breaks at CFS [55, 94, 95]. However, loss of WRN-mediated fork restart at CFS strikingly induces RAD51 dependency for viability [55]. This phenotype, uncovered using WRN-deficient cells, together with the observation that loss of WRN results in a strong accumulation of ssDNA gaps but not DSBs after perturbation of replication at CFS [55], would be consistent with the requirement of RAD51 to complete replication of regions at CFS, suggesting that RAD51 is important for CFS integrity but especially for a backup role after replication. This post-replicative role for RAD51 would be consistent with the observed requirement of HJ resolvases, such as MUS81, in the generation of chromosome breaks at CFS [82–84]. Accordingly, the presence of unreplicated DNA at CFS would stimulate template switching, leading to accumulation of branched recombination intermediates in late G2 or early mitosis that are targeted by MUS81 or similar resolvases. Thus, the contribution of WRN to CFS stability can be outlined in the model proposed in Fig. 4, where the engagement of an alternative recombination-based pathway to rescue replication at unreplicated CFS, and its possible role for the development of DNA breaks in mitosis is also described.

Fig. 4.

Proposed model of the WRN RecQ helicase function for the replication restart at CFS. Formation of DNA secondary structures (depicted as hairpins) at a subset of CFS may hinder the progression of the replisome inducing a transient replication arrest. The WRN RecQ helicase, in cooperation with the replication checkpoint, is recruited at the fork stalling site to help in removal of the roadblock and possibly in the restoration of an active replisome, either directly or after fork regression. In the absence of WRN, the fork stalling becomes permanent because the DNA secondary structures cannot be unwound, resulting in regions of unreplicated DNA. In late S or G2, the unreplicated regions are targeted by RAD51-mediated recombination to be replicated. Extensive requirement of this backup mechanism, as probably occurs in the absence of WRN or other factors involved in replication restart at CFS, leads to accumulation of recombination intermediates that have to be resolved before mitosis. Resolution of these intermediates by resolvases such as MUS81 contributes to generate chromosome breaks and gaps at CFS, which are commonly observed in metaphase cells

Conclusions

Taking into account all data concerning the possible mechanisms that govern the stability of fragile regions, it appears plausible that problems encountered during S-phase are the causative factors of genome instability at CFS. However, despite several models having been proposed to explain the molecular basis of the instability at CFS, a clear link between replication process and DNA breakage at these loci is still under investigation. Interestingly, CFS are known to be naturally difficult-to-replicate regions. A growing body of evidence suggests that CFS instability may depend on intrinsic features of fragile regions or events that directly affect DNA replication.

Given that CFS have been demonstrated to represent the very first regions at which mutations arise after oncogene activation, and that it is widely accepted that most gross chromosomal rearrangements accumulating in solid tumors originate from fragile sites, it is evident relevant to understanding the mechanisms underlying fragility at these regions. A key role seems to be played by the ability of cells to stabilize and recover perturbed replication forks. If incorrectly handled, stalled forks could disrupt duplication of DNA at CFS, possibly resulting in the formation of large DNA unreplicated regions, which could pose a serious threat to genome stability. As a consequence, more detailed information on how cells defend themselves against this threat may come from a better elucidation of mechanisms safeguarding replication forks against degeneration into chromosomal instability at CFS. Given the importance of the maintenance of CFS during cancer development, the contribution of replication fork recovery mechanisms to CFS expression will not be long in coming.

Acknowledgments

Research in the authors’ laboratories is supported by grants from the Association for International Cancer Research to P.P., and from the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) to P.P. and A.F.

References

- 1.Glover TW, Berger C, Coyle J, Echo B. DNA polymerase alpha inhibition by aphidicolin induces gaps and breaks at common fragile sites in human chromosomes. Hum Genet. 1984;67(2):136–142. doi: 10.1007/BF00272988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glover TW, Arlt MF, Casper AM, Durkin SG. Mechanisms of common fragile site instability. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14 Spec No. 2:R197–R205. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hecht F, Glover TW. Cancer chromosome breakpoints and common fragile sites induced by aphidicolin. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1984;13(2):185–188. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(84)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mangelsdorf M, Ried K, Woollatt E, Dayan S, Eyre H, Finnis M, Hobson L, Nancarrow J, Venter D, Baker E, Richards RI. Chromosomal fragile site FRA16D and DNA instability in cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60(6):1683–1689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mimori K, Druck T, Inoue H, Alder H, Berk L, Mori M, Huebner K, Croce CM. Cancer-specific chromosome alterations in the constitutive fragile region FRA3B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(13):7456–7461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yunis JJ, Soreng AL. Constitutive fragile sites and cancer. Science. 1984;226(4679):1199–1204. doi: 10.1126/science.6239375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Branzei D, Foiani M. The checkpoint response to replication stress. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009;8(9):1038–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Debatisse M, Le Tallec B, Letessier A, Dutrillaux B, Brison O. Common fragile sites: mechanisms of instability revisited. Trends Genet. 2012;28(1):22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durkin SG, Glover TW. Chromosome fragile sites. Annu Rev Genet. 2007;41:169–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.042007.165900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lukusa T, Fryns JP. Human chromosome fragility. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1779(1):3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Tallec B, Dutrillaux B, Lachages AM, Millot GA, Brison O, Debatisse M. Molecular profiling of common fragile sites in human fibroblasts. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18(12):1421–1423. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Letessier A, Millot GA, Koundrioukoff S, Lachages AM, Vogt N, Hansen RS, Malfoy B, Brison O, Debatisse M. Cell-type-specific replication initiation programs set fragility of the FRA3B fragile site. Nature. 2011;470(7332):120–123. doi: 10.1038/nature09745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mishmar D, Rahat A, Scherer SW, Nyakatura G, Hinzmann B, Kohwi Y, Mandel-Gutfroind Y, Lee JR, Drescher B, Sas DE, Margalit H, Platzer M, Weiss A, Tsui LC, Rosenthal A, Kerem B. Molecular characterization of a common fragile site (FRA7H) on human chromosome 7 by the cloning of a simian virus 40 integration site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(14):8141–8146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zlotorynski E, Rahat A, Skaug J, Ben-Porat N, Ozeri E, Hershberg R, Levi A, Scherer SW, Margalit H, Kerem B. Molecular basis for expression of common and rare fragile sites. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(20):7143–7151. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7143-7151.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang H, Freudenreich CH. An AT-rich sequence in human common fragile site FRA16D causes fork stalling and chromosome breakage in S. cerevisiae . Mol Cell. 2007;27(3):367–379. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ragland RL, Glynn MW, Arlt MF, Glover TW. Stably transfected common fragile site sequences exhibit instability at ectopic sites. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47(10):860–872. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burrow AA, Marullo A, Holder LR, Wang YH. Secondary structure formation and DNA instability at fragile site FRA16B. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(9):2865–2877. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozeri-Galai E, Bester AC, Kerem B. The complex basis underlying common fragile site instability in cancer. Trends Genet. 2012;28(6):295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palumbo E, Matricardi L, Tosoni E, Bensimon A, Russo A. Replication dynamics at common fragile site FRA6E. Chromosoma. 2010;119(6):575–587. doi: 10.1007/s00412-010-0279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helmrich A, Ballarino M, Tora L. Collisions between replication and transcription complexes cause common fragile site instability at the longest human genes. Mol Cell. 2011;44(6):966–977. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartkova J, Horejsi Z, Koed K, Kramer A, Tort F, Zieger K, Guldberg P, Sehested M, Nesland JM, Lukas C, Orntoft T, Lukas J, Bartek J. DNA damage response as a candidate anti-cancer barrier in early human tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;434(7035):864–870. doi: 10.1038/nature03482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorgoulis VG, Vassiliou LV, Karakaidos P, Zacharatos P, Kotsinas A, Liloglou T, Venere M, Ditullio RA, Jr, Kastrinakis NG, Levy B, Kletsas D, Yoneta A, Herlyn M, Kittas C, Halazonetis TD. Activation of the DNA damage checkpoint and genomic instability in human precancerous lesions. Nature. 2005;434(7035):907–913. doi: 10.1038/nature03485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abraham RT. Cell cycle checkpoint signaling through the ATM and ATR kinases. Genes Dev. 2001;15(17):2177–2196. doi: 10.1101/gad.914401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zou L, Elledge SJ. Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science. 2003;300(5625):1542–1548. doi: 10.1126/science.1083430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Budzowska M, Kanaar R. Mechanisms of dealing with DNA damage-induced replication problems. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2009;53(1):17–31. doi: 10.1007/s12013-008-9039-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casper AM, Durkin SG, Arlt MF, Glover TW. Chromosomal instability at common fragile sites in Seckel syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(4):654–660. doi: 10.1086/422701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casper AM, Nghiem P, Arlt MF, Glover TW. ATR regulates fragile site stability. Cell. 2002;111(6):779–789. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cha RS, Kleckner N. ATR homolog Mec1 promotes fork progression, thus averting breaks in replication slow zones. Science. 2002;297(5581):602–606. doi: 10.1126/science.1071398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dillon LW, Burrow AA, Wang YH. DNA instability at chromosomal fragile sites in cancer. Curr Genomics. 2010;11(5):326–337. doi: 10.2174/138920210791616699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franchitto A, Pichierri P. Understanding the molecular basis of common fragile sites instability: role of the proteins involved in the recovery of stalled replication forks. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(23):4039–4046. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.23.18409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao H, Piwnica-Worms H. ATR-mediated checkpoint pathways regulate phosphorylation and activation of human Chk1. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(13):4129–4139. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4129-4139.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lopes M, Cotta-Ramusino C, Pellicioli A, Liberi G, Plevani P, Muzi-Falconi M, Newlon CS, Foiani M. The DNA replication checkpoint response stabilizes stalled replication forks. Nature. 2001;412(6846):557–561. doi: 10.1038/35087613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maya-Mendoza A, Petermann E, Gillespie DA, Caldecott KW, Jackson DA. Chk1 regulates the density of active replication origins during the vertebrate S phase. EMBO J. 2007;26(11):2719–2731. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petermann E, Caldecott KW. Evidence that the ATR/Chk1 pathway maintains normal replication fork progression during unperturbed S phase. Cell Cycle. 2006;5(19):2203–2209. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.19.3256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Syljuasen RG, Sorensen CS, Hansen LT, Fugger K, Lundin C, Johansson F, Helleday T, Sehested M, Lukas J, Bartek J. Inhibition of human Chk1 causes increased initiation of DNA replication, phosphorylation of ATR targets, and DNA breakage. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(9):3553–3562. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.9.3553-3562.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Durkin SG, Arlt MF, Howlett NG, Glover TW. Depletion of CHK1, but not CHK2, induces chromosomal instability and breaks at common fragile sites. Oncogene. 2006;25(32):4381–4388. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Focarelli ML, Soza S, Mannini L, Paulis M, Montecucco A, Musio A. Claspin inhibition leads to fragile site expression. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009;48(12):1083–1090. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu M, Weiss RS. Increased common fragile site expression, cell proliferation defects, and apoptosis following conditional inactivation of mouse Hus1 in primary cultured cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(3):1044–1055. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-10-0957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katou Y, Kanoh Y, Bando M, Noguchi H, Tanaka H, Ashikari T, Sugimoto K, Shirahige K. S-phase checkpoint proteins Tof1 and Mrc1 form a stable replication-pausing complex. Nature. 2003;424(6952):1078–1083. doi: 10.1038/nature01900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dang T, Bao S, Wang XF. Human Rad9 is required for the activation of S-phase checkpoint and the maintenance of chromosomal stability. Genes Cells. 2005;10(4):287–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2005.00840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Musio A, Montagna C, Mariani T, Tilenni M, Focarelli ML, Brait L, Indino E, Benedetti PA, Chessa L, Albertini A, Ried T, Vezzoni P. SMC1 involvement in fragile site expression. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(4):525–533. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akhmedov AT, Frei C, Tsai-Pflugfelder M, Kemper B, Gasser SM, Jessberger R. Structural maintenance of chromosomes protein C-terminal domains bind preferentially to DNA with secondary structure. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(37):24088–24094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.24088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ammazzalorso F, Pirzio LM, Bignami M, Franchitto A, Pichierri P. ATR and ATM differently regulate WRN to prevent DSBs at stalled replication forks and promote replication fork recovery. EMBO J. 2010;29(18):3156–3169. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Otterlei M, Bruheim P, Ahn B, Bussen W, Karmakar P, Baynton K, Bohr VA. Werner syndrome protein participates in a complex with RAD51, RAD54, RAD54B and ATR in response to ICL-induced replication arrest. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 24):5137–5146. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pichierri P, Rosselli F, Franchitto A. Werner’s syndrome protein is phosphorylated in an ATR/ATM-dependent manner following replication arrest and DNA damage induced during the S phase of the cell cycle. Oncogene. 2003;22(10):1491–1500. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baynton K, Otterlei M, Bjoras M, von Kobbe C, Bohr VA, Seeberg E. WRN interacts physically and functionally with the recombination mediator protein RAD52. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(38):36476–36486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303885200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pichierri P, Franchitto A, Mosesso P, Palitti F. Werner’s syndrome protein is required for correct recovery after replication arrest and DNA damage induced in S-phase of cell cycle. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12(8):2412–2421. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.8.2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sakamoto S, Nishikawa K, Heo SJ, Goto M, Furuichi Y, Shimamoto A. Werner helicase relocates into nuclear foci in response to DNA damaging agents and co-localizes with RPA and Rad51. Genes Cells. 2001;6(5):421–430. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pirzio LM, Pichierri P, Bignami M, Franchitto A. Werner syndrome helicase activity is essential in maintaining fragile site stability. J Cell Biol. 2008;180(2):305–314. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200705126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heller RC, Marians KJ. The disposition of nascent strands at stalled replication forks dictates the pathway of replisome loading during restart. Mol Cell. 2005;17(5):733–743. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heller RC, Marians KJ. Replication fork reactivation downstream of a blocked nascent leading strand. Nature. 2006;439(7076):557–562. doi: 10.1038/nature04329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van C, Yan S, Michael WM, Waga S, Cimprich KA. Continued primer synthesis at stalled replication forks contributes to checkpoint activation. J Cell Biol. 2010;189(2):233–246. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miotto B, Chibi M, Xie P, Koundrioukoff S, Moolman-Smook H, Pugh D, Debatisse M, He F, Zhang L, Defossez PA. The RBBP6/ZBTB38/MCM10 axis regulates DNA replication and common fragile site stability. Cell Rep. 2014;7(2):575–587. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhu W, Ukomadu C, Jha S, Senga T, Dhar SK, Wohlschlegel JA, Nutt LK, Kornbluth S, Dutta A. Mcm10 and And-1/CTF4 recruit DNA polymerase alpha to chromatin for initiation of DNA replication. Genes Dev. 2007;21(18):2288–2299. doi: 10.1101/gad.1585607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murfuni I, De Santis A, Federico M, Bignami M, Pichierri P, Franchitto A. Perturbed replication induced genome wide or at common fragile sites is differently managed in the absence of WRN. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33(9):1655–1663. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Petermann E, Woodcock M, Helleday T. Chk1 promotes replication fork progression by controlling replication initiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(37):16090–16095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005031107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Singleton MR, Scaife S, Wigley DB. Structural analysis of DNA replication fork reversal by RecG. Cell. 2001;107(1):79–89. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00501-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whitby MC, Vincent SD, Lloyd RG. Branch migration of Holliday junctions: identification of RecG protein as a junction specific DNA helicase. EMBO J. 1994;13(21):5220–5228. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sogo JM, Lopes M, Foiani M. Fork reversal and ssDNA accumulation at stalled replication forks owing to checkpoint defects. Science. 2002;297(5581):599–602. doi: 10.1126/science.1074023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ray Chaudhuri A, Hashimoto Y, Herrador R, Neelsen KJ, Fachinetti D, Bermejo R, Cocito A, Costanzo V, Lopes M. Topoisomerase I poisoning results in PARP-mediated replication fork reversal. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(4):417–423. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Betous R, Mason AC, Rambo RP, Bansbach CE, Badu-Nkansah A, Sirbu BM, Eichman BF, Cortez D. SMARCAL1 catalyzes fork regression and Holliday junction migration to maintain genome stability during DNA replication. Genes Dev. 2012;26(2):151–162. doi: 10.1101/gad.178459.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ciccia A, Nimonkar AV, Hu Y, Hajdu I, Achar YJ, Izhar L, Petit SA, Adamson B, Yoon JC, Kowalczykowski SC, Livingston DM, Haracska L, Elledge SJ. Polyubiquitinated PCNA recruits the ZRANB3 translocase to maintain genomic integrity after replication stress. Mol Cell. 2012;47(3):396–409. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gari K, Decaillet C, Stasiak AZ, Stasiak A, Constantinou A. The Fanconi anemia protein FANCM can promote branch migration of Holliday junctions and replication forks. Mol Cell. 2008;29(1):141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Machwe A, Xiao L, Groden J, Orren DK. The Werner and Bloom syndrome proteins catalyze regression of a model replication fork. Biochemistry. 2006;45(47):13939–13946. doi: 10.1021/bi0615487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Betous R, Couch FB, Mason AC, Eichman BF, Manosas M, Cortez D. Substrate-selective repair and restart of replication forks by DNA translocases. Cell Rep. 2013;3(6):1958–1969. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berti M, Ray Chaudhuri A, Thangavel S, Gomathinayagam S, Kenig S, Vujanovic M, Odreman F, Glatter T, Graziano S, Mendoza-Maldonado R, Marino F, Lucic B, Biasin V, Gstaiger M, Aebersold R, Sidorova JM, Monnat RJ, Jr, Lopes M, Vindigni A. Human RECQ1 promotes restart of replication forks reversed by DNA topoisomerase I inhibition. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20(3):347–354. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bansbach CE, Betous R, Lovejoy CA, Glick GG, Cortez D. The annealing helicase SMARCAL1 maintains genome integrity at stalled replication forks. Genes Dev. 2009;23(20):2405–2414. doi: 10.1101/gad.1839909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Betous R, Glick GG, Zhao R, Cortez D. Identification and characterization of SMARCAL1 protein complexes. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e63149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cotta-Ramusino C, Fachinetti D, Lucca C, Doksani Y, Lopes M, Sogo J, Foiani M. Exo1 processes stalled replication forks and counteracts fork reversal in checkpoint-defective cells. Mol Cell. 2005;17(1):153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hashimoto Y, Ray Chaudhuri A, Lopes M, Costanzo V. Rad51 protects nascent DNA from Mre11-dependent degradation and promotes continuous DNA synthesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(11):1305–1311. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schlacher K, Christ N, Siaud N, Egashira A, Wu H, Jasin M. Double-strand break repair-independent role for BRCA2 in blocking stalled replication fork degradation by MRE11. Cell. 2011;145(4):529–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Machwe A, Karale R, Xu X, Liu Y, Orren DK. The Werner and Bloom syndrome proteins help resolve replication blockage by converting (regressed) holliday junctions to functional replication forks. Biochemistry. 2011;50(32):6774–6788. doi: 10.1021/bi2001054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Franchitto A, Pichierri P. Werner syndrome protein and the MRE11 complex are involved in a common pathway of replication fork recovery. Cell Cycle. 2004;3(10):1331–1339. doi: 10.4161/cc.3.10.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lu X, Parvathaneni S, Hara T, Lal A, Sharma S. Replication stress induces specific enrichment of RECQ1 at common fragile sites FRA3B and FRA16D. Mol Cancer. 2013;12(1):29. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Llorente B, Smith CE, Symington LS. Break-induced replication: what is it and what is it for? Cell Cycle. 2008;7(7):859–864. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.7.5613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Malkova A, Ira G. Break-induced replication: functions and molecular mechanism. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2013;23(3):271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hashimoto Y, Puddu F, Costanzo V. RAD51- and MRE11-dependent reassembly of uncoupled CMG helicase complex at collapsed replication forks. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(1):17–24. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Murfuni I, Basile G, Subramanyam S, Malacaria E, Bignami M, Spies M, Franchitto A, Pichierri P. Survival of the replication checkpoint deficient cells requires MUS81-RAD52 function. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(10):e1003910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Deem A, Keszthelyi A, Blackgrove T, Vayl A, Coffey B, Mathur R, Chabes A, Malkova A. Break-induced replication is highly inaccurate. PLoS Biol. 2011;9(2):e1000594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hicks JK, Chute CL, Paulsen MT, Ragland RL, Howlett NG, Gueranger Q, Glover TW, Canman CE. Differential roles for DNA polymerases eta, zeta, and REV1 in lesion bypass of intrastrand versus interstrand DNA cross-links. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(5):1217–1230. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00993-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mizuno K, Miyabe I, Schalbetter SA, Carr AM, Murray JM. Recombination-restarted replication makes inverted chromosome fusions at inverted repeats. Nature. 2013;493(7431):246–249. doi: 10.1038/nature11676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Naim V, Wilhelm T, Debatisse M, Rosselli F. ERCC1 and MUS81-EME1 promote sister chromatid separation by processing late replication intermediates at common fragile sites during mitosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(8):1008–1015. doi: 10.1038/ncb2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ying S, Minocherhomji S, Chan KL, Palmai-Pallag T, Chu WK, Wass T, Mankouri HW, Liu Y, Hickson ID. MUS81 promotes common fragile site expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(8):1001–1007. doi: 10.1038/ncb2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Murfuni I, Nicolai S, Baldari S, Crescenzi M, Bignami M, Franchitto A, Pichierri P. The WRN and MUS81 proteins limit cell death and genome instability following oncogene activation. Oncogene. 2013;32(5):610–620. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schwartz M, Zlotorynski E, Goldberg M, Ozeri E, Rahat A, le Sage C, Chen BP, Chen DJ, Agami R, Kerem B. Homologous recombination and nonhomologous end-joining repair pathways regulate fragile site stability. Genes Dev. 2005;19(22):2715–2726. doi: 10.1101/gad.340905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vernole P, Muzi A, Volpi A, Terrinoni A, Dorio AS, Tentori L, Shah GM, Graziani G. Common fragile sites in colon cancer cell lines: role of mismatch repair, RAD51 and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. Mutat Res. 2011;712(1–2):40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pichierri P, Ammazzalorso F, Bignami M, Franchitto A. The Werner syndrome protein: linking the replication checkpoint response to genome stability. Aging (Albany NY) 2011;3(3):311–318. doi: 10.18632/aging.100293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pichierri P, Nicolai S, Cignolo L, Bignami M, Franchitto A. The RAD9-RAD1-HUS1 (9.1.1) complex interacts with WRN and is crucial to regulate its response to replication fork stalling. Oncogene. 2012;31(23):2809–2823. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sidorova JM, Li N, Folch A, Monnat RJ., Jr The RecQ helicase WRN is required for normal replication fork progression after DNA damage or replication fork arrest. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(6):796–807. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.6.5566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Prince PR, Emond MJ, Monnat RJ., Jr Loss of Werner syndrome protein function promotes aberrant mitotic recombination. Genes Dev. 2001;15(8):933–938. doi: 10.1101/gad.877001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sidorova JM, Kehrli K, Mao F, Monnat R., Jr Distinct functions of human RECQ helicases WRN and BLM in replication fork recovery and progression after hydroxyurea-induced stalling. DNA Repair (Amst) 2013;12(2):128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kamath-Loeb AS, Loeb LA, Johansson E, Burgers PM, Fry M. Interactions between the Werner syndrome helicase and DNA polymerase delta specifically facilitate copying of tetraplex and hairpin structures of the d(CGG)n trinucleotide repeat sequence. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(19):16439–16446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100253200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shah SN, Opresko PL, Meng X, Lee MY, Eckert KA. DNA structure and the Werner protein modulate human DNA polymerase delta-dependent replication dynamics within the common fragile site FRA16D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(4):1149–1162. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sonoda E, Sasaki MS, Buerstedde JM, Bezzubova O, Shinohara A, Ogawa H, Takata M, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Takeda S. Rad51-deficient vertebrate cells accumulate chromosomal breaks prior to cell death. EMBO J. 1998;17(2):598–608. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Takata M, Sasaki MS, Tachiiri S, Fukushima T, Sonoda E, Schild D, Thompson LH, Takeda S. Chromosome instability and defective recombinational repair in knockout mutants of the five Rad51 paralogs. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(8):2858–2866. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.8.2858-2866.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]