Abstract

The retrograde transport of endosomes within axons proceeds with remarkable uniformity despite having to navigate a discontinuous microtubule network. The mechanisms through which this navigation is achieved remain elusive. In this report, we demonstrate that access of SxIP motif proteins, such as BPAG1n4, to the microtubule plus end is important for the maintenance of processive and sustained retrograde transport along the axon. Disruption of this interaction at the microtubule plus end significantly increases endosome stalling. Our study thus provides strong insight into the role of plus-end-binding proteins in the processive navigation of cargo within the axon.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00018-014-1611-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: BPAG1n4, Axonal transport, Endosomes, Microtubules, Dynein

Introduction

Neurons are extremely reliant on cargo transport as a consequence of their highly polarized morphology. Disruption of axonal transport has devastating consequences, and has been implicated in many neurodegenerative diseases [1, 2]. Within the axon, microtubules (MTs) are polarized with their plus ends directed distally, and their minus ends directed towards the soma. No single MT extends from the soma to neurite tip; instead, discontinuous segments are staggered along the length of the axon. As a consequence of this complex architecture, processive axonal transport must involve efficient switching of motor-cargo complexes between individual MT tracks as they navigate the length of the axon. Despite the vital importance of the axonal transport system, little is known about the mechanisms that regulate inter-MT switching of cargo along discontinuous tracks. In this study, we reveal that in addition to their activities as regulators of MT dynamics, SxIP motif-containing plus-end-binding proteins (+TIPs) also play a critical role in the maintenance of processive (i.e., smooth, unidirectional and sustained) retrograde transport along the axon.

+TIPs represent a diverse group of proteins that specifically accumulate at growing MT plus ends. As their name implies, the end-binding (EB1) family proteins preferentially assemble at plus ends, and the localization of many +TIPs is dependent on EB1 [3–5]. There are two major families of +TIPs. The first family that includes CLIPs and p150Glued contains (cytoskeleton-associated protein glycine-rich) CAP-Gly domains. The second family contains basic and serine-rich regions, characterized by a short SxIP peptide motif [6–8]. +TIPs function as regulators of MT dynamics, and as such are critical for diverse cellular functions including chromosome segregation, cell polarization, and migration [3]. Recent studies in melanophores, fungus, and in neurons have implicated the CAP-Gly domain +TIPs, CLIP-170, and p150Glued as being involved in cargo loading and in the initiation of retrograde transport at the cell periphery and at the distal neurite. However, the plus-end association of p150Glued is not necessary for the maintenance of processive transport along the axon [9–13].

BPAG1n4, a gigantic 600-kDa protein, is essential for retrograde axonal transport by virtue of its interactions with dynactin, via p150Glued, and with endosomes, via the transmembrane protein retrolinkin. Loss of BPAG1 severely disrupts retrograde transport, and results in massive sensory neurodegeneration [14, 15]. Interestingly, the carboxyl (C)-terminus of BPAG1n4 contains highly conserved SxIP motifs [6, 8, 16]. The ability of BPAG1n4 to interact independently with the three major components of the transport system makes it ideally placed to coordinate retrograde axonal transport. Its SxIP motif-containing C-terminus makes an ideal probe with which to investigate the role of these +TIPs in axonal transport. In this report, using single-molecule labeling coupled with live imaging to track individual endosomes, we provide evidence indicating that access of SxIP motif-containing +TIPs such as BPAG1n4 to EB1 family proteins at the MT plus end is important for processive retrograde endosome transport. This study implicates +TIPs in the maintenance of processive retrograde transport along the axon, and may provide insight into a mechanistic model for cargo switching between individual MTs during axonal transport.

Materials and methods

Plasmids and cloning

Cloning of BPAG1n4 constructs has been previously described [16]. The domain structures of BPAG1n4 and expression constructs that are used in this study are schematically shown in Fig. S1. Two GST-EBBD constructs were used: (1) GST-EBBD contains the identical insert to that in GFP-EBBD; (2) GST-EBBDmin retains the entire SxIP motif region with some of the upstream flanking sequences deleted in GST/GFP-EBBD to facilitate solubility for bacterial expressions. The MBP-EB1 construct (pMAL-EB1) for bacterial expression was a gift from W. J. Nelson (Stanford University) [17]. pMAL-EB1c∆8, pRFPN1-EB1c∆8, and pEGFPN1-EB1c∆8 (amino acids 191–260) were generated by PCR amplification [6].

Primary antibodies used

Rabbit anti-BPiso4 [14], mouse anti-MBP (New England Biolabs), mouse anti-p150Glued and mouse anti-EB1 (BD transduction), rat anti-EB3 (Absea), mouse and rabbit anti-GFP (Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-actin (Cytoskeleton).

Cell culture and transfections

Cos-7 and Hek-293T cells were cultured in DMEM medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum. Plasmids were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Microscopy

All imaging was performed on a Leica fluorescent inverted microscope DMI6000B using a 100× HCX PLAPO objective with a numerical aperture of 1.47. A QImaging Retiga EXi Fast 1394 camera was used. Cos-7 cells for live imaging experiments were cultured in glass-bottomed cell culture dishes, and imaged 12–14 h post transfection. Live-cell imaging was performed in a temperature (37 °C) and CO2 (5 %) controlled chamber. Each cell was imaged for 1–2 min with a frame acquired every 2 s. MetaMorph (v7.7) was used for acquisition and analysis. Images were prepared for presentation in MetaMorph and Adobe Photoshop.

ImmunoEM

ImmunoEM was performed as previously described [14, 15]. Briefly, wild-type mice were killed by intravenous perfusion with 2 % PFA and 0.05 % glutaraldehyde. The dissected samples of sciatic nerves were postembedded, and antibody incorporations on ultrathin sections were visualized with 18-nm anti-rabbit and 6-nm anti-mouse gold conjugated particles (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). After staining with uranyl acetate, followed by lead citrate, the sections were analyzed under an electron microscope (model CM10; Philips). Primary antibodies used: Rat anti-EB3 (Absea) and Rabbit anti-BPiso4 [14].

Protein production and in vitro binding assays

Recombinant protein production, binding assays, and immuno-precipitations (IPs) were performed as previously described [16]. For IP, rabbit anti-GFP was used and membranes were blotted with mouse anti-GFP and mouse anti-EB1 to check endogenous protein levels and pull down. All experiments were repeated three or more times. For the BPAG1 pulldown and competition assay, MBP or MBP-EB1 was immobilized on amylose beads and then blocked at 4 °C, with 0.2 % BSA in MBP-binding buffer (20 mM HEPES/10 % glycerol/1 mM DTT/100 mM NaCl/0.5 % Nonidet P-40/0.25 mM KCl). After blocking, the immobilized protein (MBP or MBP-EB1) was incubated with mouse brain lysate (50 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1 % NP-40, 0.5 % sodium deoxycholate, 0.1 % SDS, 50 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 0.5 mM PMSF) for 2 h. After washing, the EB1-bound BPAG1n4 was eluted by SDS sample buffer and detected by blotting with anti BPAG1n4 antibody [14]. For the competition assay, bound MBP-EB1 was preincubated with either bacterially expressed GST or bacterially expressed GST-EBBD for 1 h before being incubated with brain lysate. In addition, purified GST or GST-EBBD was added to the brain lysate, such that they constituted <2 % of the total protein sample. Proteins were analyzed using SDS-PAGE, and either stained using Coomassie Brilliant Blue R250 (ThermoScientific), or analyzed by Western blotting, as appropriate. As before, band intensities were determined using ImageJ software. For quantification, the intensity of the BPAG1n4 band was first normalized to the appropriate MBP-EB1 band. EB1 binding was defined as 1 in the absence of any competition, and binding in the presence of GST or GST-EBBD was expressed as a fraction of that binding. Statistical significance was analyzed by one-sample t test in GraphPad Prism 6.0.

Lentivirus cloning and production

The GFP fusion BPAG1n4 constructs previously described in Kapur et al. [16] were excised from the pEGFP-C2 backbone with Mfe1/Nhe1 and subcloned into EcoR1/Xba1 sites in the FUGW vector [18] (a gift from C. Garner, Stanford University), replacing the original EGFP cassette in FUGW. Mfe1 and Nhe1 are mutually compatible with EcoR1 and Xba1, respectively. EB1c∆8-GFP was similarly excised from the pEGFP-N1 backbone and cloned into FUGW. Lentivirus was produced as previously described [15, 18]. A three-plasmid vector system comprising a shuttle plasmid, (FUGW,FUGW-SxIP or FUGW-MTBD) and two packaging plasmids (pCMV∆R 8.9 and pHCMV VSVg) were transfected in HEK293T cells (grown in DMEM +10 % FBS). Transfections were conducted on confluent cell cultures with CalFectin reagent (SigmaGen Laboratories) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The medium was replaced with Neurobasal medium supplemented with B27 and Glutamax (Invitrogen) 12 h after transfection. Two days after transfection, the virus containing medium was collected, passed through a 0.45-μm filter to remove cell debris, and then frozen at −80 °C. This viral supernatant was used to infect dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons.

Microfluidic chambers

Microfluidic chambers used in these experiments are original designs from our lab manufactured at the Stanford Nanofabrication Facility, essentially as described previously [19]. The chamber design allows for cell bodies to be grown in one compartment while axons are directed to another adjacent compartment through embedded microgrooves. In addition, fluidic isolation can be created between the cell body and axonal compartments by maintaining a slightly higher liquid level in the cell body compartment. This prevents the diffusion of analytes from the distal axon compartment to the cell body compartment. Briefly, blueprints produced using computer-aided design software (L Edit v12, Tanner EDA Software tools) were used to make high-resolution 20,000 d.p.i. transparency masks for photolithography. Masks were used to pattern 100-mm silicon wafers for master templates beginning with SU8-2005 to create 5-μm features (microgrooves), followed by SU8-2050 for 100-μm features (cell body and distal axon chambers). Finally, polydimethylsiloxane (Sylgard 184 Elastomer; Dow Corning) molds produced using the master template were cut to final dimensions and used as microfluidic chambers. Microfluidic chambers were placed onto poly-d-lysine-coated coverslips for neuronal culture.

Dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neuron culture and lentiviral infection

DRG neurons were dissected from embryonic (E16-E17) Sprague–Dawley rats and dissociated in 0.25 % trypsin (Invitrogen). Dissociated neurons were then incubated in 100–200 μl of the appropriate lentivirus supernatant for 15 min, and plated in the cell body compartment of microfluidic chambers in Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum and 50 ng/ml nerve growth factor (NGF). Twelve hours after plating, the medium was replaced with serum-free Neurobasal medium supplemented with B27, Glutamax (Invitrogen) and 50 ng/ml NGF. Lentiviral infection rates were approximately 95–100 %. Axons generally crossed the microgrooves within 5–6 days. Transport imaging experiments were performed on DIV 6–7.

Live imaging of axonal transport

Biotinylated transferrin (Invitrogen) and quantum dot-655 (Invitrogen) were conjugated overnight at 4 °C in a 20:1 molar ratio. Transferrin-QD conjugate (Tf-QD) was added to the axon chamber at a final concentration of 150nM, and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min before imaging. For the taxol experiment, 10 μM taxol (Cytoskeleton) was added, and chambers were immediately imaged for up to 5 min after addition of drug. For all transport, we captured 4-min-long movies, with a frame acquired every 2 s. On average, 5–8 movies were taken per microfluidic chamber, and a minimum of three independent microfluidic chambers were imaged per condition. Out of each microfluidic chamber, 50–60 Tf-QDs were tracked using the Track Points feature in Metamorph. Only quantum dots that could be tracked for six or more frames were further analyzed. Post-analysis was performed in Microsoft Excel. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 6.0. Either a Student’s t test or a one-way ANOVA with a Dunnett’s post-test was used to calculate statistical significance when comparing two datasets or more than two datasets respectively. A paused quantum dot was defined as one moving less than 0.5 μm/s, that is, a quantum dot with <1 μm absolute displacement between two consecutive frames. A moving quantum dot was defined as any showing continuous displacement not interrupted by a pause, that is, a quantum dot that showed >1 μm displacement between consecutive frames. For example, the status of a quantum dot at any given frame (x) of the movie can be calculated as: IF (AND(ABS(R(x) − R(x-1)) < 1, ABS(R(x) − R(x + 1) < 1), “paused”, “moving”), where R(x) is the displacement of the quantum dot at frame (x) from the origin, R(x − 1) is the displacement from origin in the previous frame, and R(x + 1) is the absolute displacement from origin in the next frame. Average speed was calculated based on the final displacement of the quantum dot from its origin at the last point measured, and includes periods of anterograde motion and pauses. The active moving velocity was calculated frame by frame and only included quantum dots during periods of active movement, and ignored times in which a quantum dot was paused. For a frame in which a quantum dot was determined to be moving (x), moving velocity was calculated by: ABS(R(x) − R(x − 1))/t, where R(x) is the displacement of the quantum dot at frame (x) from the origin, and R(x − 1) is the displacement from the origin in the previous frame, and t is the time interval in seconds between the two frames. This value was calculated for every frame in which the quantum dot was in motion, and averaged to give an average moving velocity for the trajectory of an individual quantum dot.

Results

The SxIP motif at the C-terminus of BPAG1n4 behaves as a +TIP in neurons

The SxIP motif is well recognized as an EB1-binding motif, and it underlies the localization of numerous +TIPs including APC, STIM1, and CLASP proteins to the MT plus end in an EB1-dependent manner [6, 8]. We have previously shown that the C-terminus of BPAG1n4 contains a calcium-regulated EB1-binding domain (EBBD) that consists of SxIP motifs [16] (Fig. S1). Growing evidence suggests that the MT plus ends play a major role in the initial recruitment of cargo and the initiation of transport at the periphery in both neurons and non-neuronal cells [9–11, 13]. We questioned whether the SxIP motif-containing +TIPs may play a role in long-range axonal transport. To address this, we expressed the SxIP motif-containing EBBD in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons using lentiviral vectors. GFP-EBBD has been previously reported to function as a +TIP in Cos-7 cells, where it tracks MT plus ends with dynamics similar to those previously reported for EB1 and EB3 [16]. In virally transduced DRG neurons, dynamic GFP-EBBD comets, characteristic of +TIPs, move longitudinally throughout the axon (Fig S2C, Video S1). This mimics the reported localization and behavior of EB1 in neurons and reveals that the SxIP motif domain can also function as a +TIP in DRG neurons [20].

Endogenous BPAG1n4 interacts with members of the EB1 family

Using an in vitro binding assay, we have previously demonstrated a direct interaction between the SxIP motif-containing C-terminal domain of BPAG1n4 and EB1 [16]. Here, we further confirmed that GFP-EBBD co-immunoprecipitated endogenous EB1 from 293T cells, and that GST-EBBD could interact directly with both EB1, and its brain enriched family member EB3 (Fig S2A, B). We next assessed whether the presence of the SxIP motif was sufficient to mediate an interaction between EB1 family proteins and endogenous BPAG1n4. We examined the interaction between endogenous BPAG1n4 and purified EB1 in vitro. Maltose-binding protein-conjugated EB1 (MBP-EB1), but not MBP alone, precipitated BPAG1n4 from mouse brain (Fig. 1a, n = 3). Next, we investigated the localization of endogenous BPAG1n4 using immuno-EM co-labeling. Previous ultrastructural studies have reported that the majority of BPAG1n4 localizes to vesicle-like structures distributed along MTs and that this interaction is mediated via retrolinkin [14, 15]. From four independent co-labeling trials, we observed that approximately 15–20 % of the BPAG1n4 particles co-localize with EB3 at MT plus ends (Fig. S2D). This suggests that the interaction between BPAG1n4 and EB1 family proteins is likely to be transient, consistent with a role in the dynamic process of axonal transport.

Fig. 1.

Expression of the EBBD impairs the retrograde transport of endosomes in DRG neurons. a EB1 interacts with endogenous BPAG1n4. MBP-EB1 (lane 4), but not MBP (lane 3) can pull down full-length, endogenous BPAG1n4 from wild-type mouse brain lysate. BPAG1n4 can be clearly detected in wild-type mouse brain lysate (input, lane 1), but not in brain lysate from a BPAG1 knockout mouse (lane 2), n = 3. b GST-EBBD competes with full-length BPAG1n4 for binding to EB1. MBP-EB1 was immobilized on beads and used to pull down BPAG1n4 from brain lysate in the presence of either GST alone (lane 2) or GST-EBBD (lane 1). The presence of GST-EBBD results in significantly reduced binding of BPAG1n4 to MBP-EB1 (n = 3, p < 0.01, one-sample t test). BPAG1n4 band intensities were normalized to MBP-EB1 levels, and binding in the presence of GST was set to equal to 1. Representative Tf-QDs in c GFP and d GFP-EBBD-expressing neurons. Tf-QD position is marked by a white arrow. d A second Tf-QD is marked by a white arrowhead. Note the lack of processive motion in d. Scale bar 5 μm. e Expression of EBBD impairs retrograde axonal transport. Comparison of Tf-QD distance versus time trajectories in GFP (green) and GFP-EBBD-expressing neurons (blue). Fifty endosome trajectories are shown from a representative GFP and GFP-EBBD microfluidic chambers each. Note the clear separation of the populations. Student’s t test, n = 5 independent microfluidic chambers (50–60 trajectories per chamber), ± is SEM. f Quantification of average speed of Tf-QDs in GFP and GFP-EBBD-expressing neurons. GFP = 1.174 ± 0.147 μm/s, EBBD = 0.589 ± 0.098 μm/s. g Quantification of the % time spent paused. GFP = 15.08 ± 2.37 %, EBBD = 42.40 ± 5.41 %. h Quantification of moving velocity of Tf-QD-containing endosomes. GFP = 1.54 ± 0.1 μm/s, EBBD = 1.24 ± 0.08 μm/s

Expression of the isolated EBBD impairs the retrograde transport of endosomes

The interactions between +TIPs are transient and competitive, and indeed, studies have shown that the SxIP motif-containing +TIPs reciprocally compete for binding to EB1, as they use the same binding site at the EB homology domains [3, 8]. As a robust EB1-binding partner, we anticipated that the expression of the EBBD should interfere with and disrupt access of endogenous SxIP motif-containing +TIPs, such as BPAG1n4, to EB1 at the MT plus end. Indeed, competition experiments using glutathione-S-transferase-conjugated EBBD (GST-EBBD) revealed that the EBBD could compete with endogenous full-length BPAG1n4 for binding to EB1. We found that addition of GST-EBBD but not GST alone dramatically reduced the amount of BPAG1n4 that was pulled down from mouse brain lysate by purified MBP-EB1 (Fig. 1b, n = 3, one-sample t test). Expression of the SxIP domain (EBBD) would thus allow us to assess the role of these dynamic EB1-binding interactions in axonal transport.

To examine retrograde axonal transport, we used quantum-dot conjugated transferrin (Tf-QD), which undergoes receptor-mediated endocytosis and is transported towards the cell body. Previous studies have shown that loss of BPAG1 severely impairs the retrograde transport of transferrin in DRG neurons [14]. In order to eliminate background caused by diffusion and interference from surface-bound Tf-QDs, we cultured DRG neurons in microfluidic chambers. Microfluidic chambers allow for the separation of neuronal cell bodies from distal axons in fluidically isolated compartments, enabling us to follow individually labeled endosomes while also ensuring that all transport is initiated at the distal axon [19]. We found that the transport of Tf-QD-containing endosomes was severely impaired in GFP-EBBD overexpressing neurons in comparison to control neurons expressing GFP only (Fig. 1c–h, Video S2, n = 5 independent microfluidic chambers per condition, 50–60 quantum dots tracked per chamber, for a total of 250–300 axonal transport trajectories for each condition). Tf-QDs in GFP-expressing neurons exhibited processive, almost exclusively unidirectional, retrograde motion with infrequent short pauses, which is similar to the reported behavior of other endosomal cargoes in neurons (Fig. 1c) [21, 22]. In contrast, Tf-QDs in GFP-EBBD-expressing neurons advance much less processively, stalling and sometimes reversing direction for brief periods (Fig. 1d). Expression of GFP-EBBD resulted in a significant decrease in the average speed of Tf-QD labeled endosomes as compared to GFP control (Fig. 1f, p < 0.05, Student’s t test). Average speed is calculated as the total displacement over time, a measurement that includes periods of active movement and time spent paused, thus changes in either the moving speed or pausing behavior may contribute to the observed reduction of average speed in GFP-EBBD-expressing neurons. We did not observe a significant change in moving velocity, which calculates the velocity of endosomes only when they are in active motion (Fig. 1h, p > 0.05, Student’s t test), suggesting that the intrinsic activity of the dynein/dynactin motor complex remains largely intact. In contrast, we observed a significant increase in the percent of time Tf-QDs spent paused in GFP-EBBD-expressing neurons. In GFP-expressing control neurons, TF-QD endosomes spend approximately 10–15 % of their time paused. Strikingly, endosomes in GFP-EBBD-expressing neurons are paused for approximately 43 % of the time, a significant increase compared to control (Fig. 1g, p < 0.01, Student’s t test). Together, our data demonstrate that expression of the SxIP domain (EBBD) severely impairs the processivity of retrograde endosome transport in DRG neurons. This pattern suggests that the recruitment of SxIP motif-containing proteins by the EB1 family at the MT plus end is essential for maintaining processive and sustained retrograde axonal transport.

Dynamic MT plus ends are important for processive retrograde transport

As EB1 family proteins only track growing MT plus ends, treatment of cells with drugs that alter MT dynamics, such as taxol, abolish the binding of +TIPs to the ends of MTs. Treatment with either low levels of these drugs, or for brief time periods has been reported to result in the dissociation of +TIPs without significant changes in the MT polymer mass, or motor activity or distribution [9, 20, 23]. Indeed, experiments on motor activity have traditionally been performed on taxol stabilized microtubules. In addition, studies have found that taxol induced changes in motor protein distribution occur on the order of hours or days of taxol treatment [24, 25]. We confirmed that treatment with 10 μM taxol abolished the plus-end tracking of GFP-EBBD within seconds, without dramatically altering the MT network (data not shown) [20]. To determine whether these changes in MT dynamics, resulting in the loss of EB1 family proteins from the MT plus end, affected the ability of DRG neurons to retrogradely transport Tf-QDs, we examined the transport of Tf-QDs in DRG neurons before and up to 5 min after the addition of taxol. We found that treatment with 10 μM taxol severely impaired the processivity of Tf-QD-containing endosomes (Fig. 2a, b, n = 6 microfluidic chambers). Immediately after addition of taxol, a significant reduction in the average speed of endosomes was observed (Fig. 2c, p < 0.01, Student’s paired t test), resulting from a significant increase in the percent of time an endosome spent stalled (Fig. 2d, p < 0.01, Student’s paired t test). Surprisingly, we observed a small but significant change in the moving velocity of Tf-QDs in the taxol-treated neurons (Fig. 2e, p < 0.05, Student’s paired t test). There are two possible explanations for this decreased moving velocity. The first is that taxol treatment is indeed having direct effect on the motor activity. This seems extremely unlikely to occur within the brief time period of our experiment. Alternatively, and more plausible, is that our acquisition time of one frame every second masks some very brief, cryptic pauses, or partially overlaps with a pause and thus results in a reduction in moving velocity. It may also mask rapid transient reversals in the direction of motion, which would also result in an apparent reduction in the moving velocity. This would suggest that in situations where the frequency of pausing exceeds the acquisition time threshold, the calculated moving velocity is not an entirely accurate representation of the instantaneous velocity of the motor. The rapid and significant decrease of Tf-QD motility caused by taxol indicates that MT dynamics are important for the maintenance of processive retrograde axonal transport, and bolsters our hypothesis that EB1-binding proteins at dynamic MT plus end play a key role in regulating processive transport of endosomes.

Fig. 2.

Taxol treatment disrupts the retrograde axonal transport of endosomes. Representative Tf-QDs in untreated (a) and taxol-treated neurons (b). Tf-QD position is marked by a white arrow. b A second Tf-QD is marked by a white arrowhead. Note the lack of processive motion in b. Images in b were taken 1–2 min after the addition of taxol. Scale bar 5 μm. Student’s paired t test, n = 6 independent microfluidic chambers, ± is SEM. c Quantification of the average speed of Tf-QDs in untreated and taxol-treated neurons. Pre-taxol 1.649 ± 0.15 μm/s, post-taxol 1.161 ± 0.13 μm/s. d Quantification of the % time spent paused by Tf-QDs in untreated and taxol-treated neurons. Pre-taxol 7.53 ± 1.84 %, post-taxol 17.55 ± 3.10 %. e Quantification of the moving velocity of Tf-QDs in untreated and taxol-treated neurons. Pre-taxol 1.945 ± 0.11 μm/s, post-taxol 1.654 ± 0.11 μm/s

Expression of MT-lattice-binding domains is not sufficient to impair retrograde axonal transport

In addition to strongly binding to EB1 at the MT plus ends, SxIP peptides have been reported to very weakly associate with the MT lattice [6]. We did not observe any appreciable localization of GFP-EBBD to the MT lattice in virally transduced DRG neurons (Fig. S2C, Video S1). However, to eliminate the possibility that the observed transport phenotype was simply a result of over-stabilization of the MT lattice, and not a result of specific binding to EB1 at the plus end, we investigated the effect caused by expression of a classical MT-lattice-binding domain, the GAR domain of BPAG1n4 [16, 26]. Previously, studies have demonstrated that expression of the BPAG1n4 MT-binding domain (MTBD), containing the GAR motif, mediates interaction with the MT lattice while displaying no specific plus-end binding [16, 26]. The GAR domain has been reported to bind to microtubules with an affinity of 0.6 μM, which is similar to that reported for classical MAPs [26]. In DRG neurons, GFP-MTBD was strongly expressed and localized throughout the cell and along the distal axon (Figs. S3A, S4A). However, the transport of Tf-QD-containing endosomes in GFP-MTBD-overexpressing neurons was not significantly affected (Fig. S3B-E, Video S2, n = 5 independent chambers, 50–60 quantum dots tracked per chamber, 250–300 trajectories per condition, p > 0.05, Student’s t test). Despite the fact that GFP-MTBD and GFP-EBBD are expressed at largely similar levels (Fig. S4), the lack of a significant defect in retrograde axonal transport upon the expression of GFP-MTBD suggests that MT plus-end association of the SxIP domain (EBBD), rather than any possible lattice association, underlies the observed transport defect.

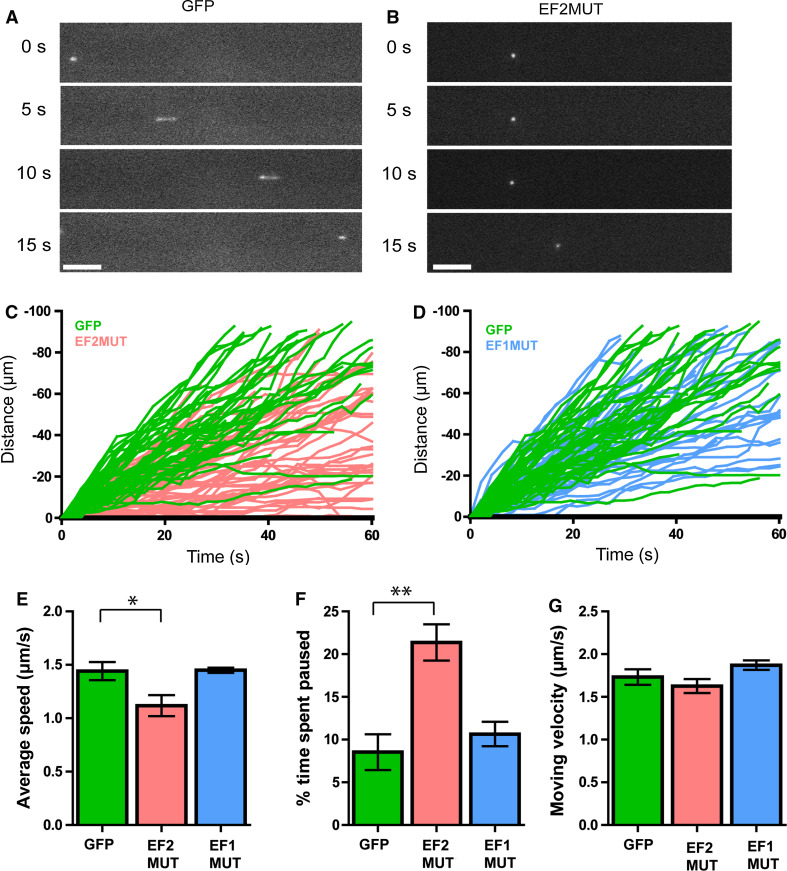

We have previously found that there is a rapid, calcium-regulated switch between MT plus-end interaction and lattice binding in the C-terminus of BPAG1n4 (BP4tail), and that mutations of the EF-hands abolish this switch [16]. Interestingly, point mutations in EF-hand 1 result in lattice binding (EF1MUT), while mutations in EF-hand 2 result in plus-end interaction (EF2MUT) [16]. To further confirm the importance of plus-end interaction for axonal transport, we took advantage of the differing localizations of these otherwise identical constructs. Both EF1MUT and EF2MUT constructs contain both GAR (MTBD) and SxIP (EBBD) motifs, respectively, and differ only at three residues in the EF hands. We found that while expression of the plus-end-localizing EF2MUT significantly impaired the transport of Tf-QDs in DRG neurons, expression of the lattice-binding EF1MUT had no such effect (Fig. 3, n = 5 independent chambers for each condition, 50–60 quantum dots tracked per chamber, 250–300 trajectories per condition, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test). This further suggests that the interaction of BPAG1n4 or other SxIP motif proteins with the MT plus end is a key step in the maintenance of processive axonal transport.

Fig. 3.

Expression of plus-end localizing EF2MUT, but not of lattice-binding EF1MUT alters endosomal transport. Representative Tf-QDs in GFP (a) or GFP-BP4tail EF2MUT (EF2MUT) expressing neurons (b). Note the lack of processive motion in b Scale bar 5 μm. c Expression of the EF2MUT impairs retrograde axonal transport. Comparison of the trajectories of Tf-QD-containing endosomes in GFP-expressing neurons (green) and GFP-BP4tail EF2MUT-expressing neurons (pink). Sixty endosome traces are shown for each condition from representative microfluidic chambers. Note the clear separation of the two populations. d Expression of EF1MUT does not significantly impair retrograde axonal transport. Comparison of the trajectories of Tf-QD-containing endosomes in GFP-expressing neurons (green) and GFP-BP4tail EF1MUT-expressing neurons (blue). Sixty endosome traces are shown for each condition from representative microfluidic chambers. Comparison of GFP, EF2MUT, and EF1MUT-expressing neurons. Data are mean ±SEM from five independent microfluidic chambers each (n = 5), with approximately 50–60 endosomes tracked per chamber. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post test. e Quantitative measurement of the average speed of Tf-QDs in GFP (green), GFP-BP4tail EF2MUT (pink), and GFP-BP4tail EF1MUT (blue) expressing DRG neurons. GFP 1.441 ± 0.085 μm/s, EF2MUT 1.118 ± 0.098, EF1MUT 1.448 ± 0.0.024 μm/s, p < 0.05 for GFP vs. EF2MUT. f Quantitative measurement of the average percentage of time spent paused. GFP 8.52 ± 2.095 %, EF2MUT 21.37 ± 2.127 %, EF1MUT 10.64 ± 1.431 %. p < 0.01 for GFP vs. EF2MUT. g Quantitative measurement of the average moving velocity of Tf-QD during periods of active motion. GFP 1.731 ± 0.090 μm/s, EF2MUT 1.626 ± 0.081 μm/s, EF1MUT 1.871 ± 0.055 μm/s. p > 0.05 for both conditions

Surprisingly, expression of the wild-type Ca2+ regulated BP4tail, which localizes to the MT plus in baseline conditions [16], does not significantly alter the retrograde transport of Tf-QD-containing endosomes (Fig. S5, p > 0.05, Student’s t test). Thus, despite the fact that the preferential localization and behavior of BP4tail mimics that of the EBBD and EF2MUT, they have drastically different effects on retrograde axonal transport. Given that the only major difference between BP4tail and EF2MUT is their ability to respond to Ca2+ signals [16], our results suggest that the Ca2+-driven switch in BPAG1n4 may govern the processivity of retrograde transport. This suggests the tantalizing possibility that Ca2+ may regulate the interaction of BPAG1n4 with the MT plus end as a means of controlling the dynamics of endosomal transport.

Disruption of the interaction between SxIP motif proteins and EB1 at the MT plus end is sufficient to impair endosome transport

The two major +TIP families, the CAP-Gly domain proteins and the SxIP motif proteins, interact with different, but overlapping sites on the EB1 molecule [3]. Thus, we considered the possibility that steric hindrance caused by the isolated SxIP motif domain (EBBD) could potentially interfere with the binding of CAP-Gly domain proteins, such as p150Glued and CLIP-170, to EB1. However, recent studies have found that while the plus-end localization of p150Glued and CLIP-170 is important for cargo loading or the initiation of transport at the distal neurite and synapse, it does not appear to participate in the maintenance of transport along the axon. This suggests that disruption of p150Glued binding with EB1, as a result of EBBD expression, is unlikely to underlie the observed defect in endosomal transport along the axon [10, 11, 13]. To further exclude this possibility, we turned to a construct that would allow us to more specifically discriminate between the roles of these two families of +TIPs. Honnappa et al. [6] have previously described an EB1 peptide that can bind to SxIP motifs, but not CAP-Gly domains (EB1C∆8). Expression of this C-terminal EB1 fragment should specifically disrupt the interaction between EB1 and SxIP motif +TIPs, without affecting CAP-Gly domain proteins. In addition, as EB1C∆8 lacks MT-binding domains, it avoids the confound of MT over-stabilization associated with overexpression of EB1 or EB3.

We first confirmed that EB1C∆8 could indeed interact with SxIP motifs, but not with CAP-Gly domains. Using an in vitro binding assay, we found that both MBP-EB1 and MBP-EB1C∆8 could pull down GST-EBBDmin, but not GST alone (Fig. 4a, n = 3). We used the slightly smaller GST-EBBDmin construct, as GST-EBBD is the same size as MBP- EB1C∆8, making it difficult to visualize the pull down on a Coomassie-stained gel. In contrast, only MBP-EB1, but not MBP-EB1C∆8, could pull down endogenous p150Glued (Fig. 4b, n = 3). The plus-end tracking of GFP-EBBD was disrupted in cells co-expressing EB1C∆8-RFP, but not in cells co-expressing RFP alone, suggesting that this EB1 peptide could indeed disrupt the interaction of SxIP motif proteins with EB1 at the plus end (n = 15, Video S3). We next investigated the effect of EB1C∆8-GFP expression on the transport of Tf-QD-containing endosomes in DRG neurons. Expression of EB1C∆8 severely impaired the retrograde transport of Tf-QDs, resulting in significantly reduced average speeds and increased stalling, as indicated by the increase in pausing time (Fig. 4c–e, n = 4 independent microfluidic chambers each, 50–60 Tf-QDs tracked per chamber for a total of 200–240 trajectories per condition, p < 0.01, Student’s t test). As in taxol-treated neurons, we also observed a small but significant decrease in the moving speed of endosomes (Fig. 4f, p < 0.01, Student’s t test). These findings indicate that disruption of SxIP motif +TIPs is sufficient to impair endosomal transport along the axon, and lends additional support for our hypothesis that the SxIP motif +TIPs have a central role in the maintenance of processive endosomal transport.

Fig. 4.

Expression of the C-terminal EB1 peptide EB1C∆8 impairs endosome transport. a EB1C∆8 binds to SxIP motif-containing EBBDmin. Both MBP-EB1 (lane 5) and MBP- EB1C∆8 (lane 6) pull down GST-EBBDmin, but not GST alone (lanes 2, 3). GST-EBBDmin was used instead of GST-EBBD to allow resolution from the MBP- EB1C∆8 band, which runs at approximately the same size as GST-EBBD. b EB1C∆8 does not interact with p150Glued. MBP-EB1 (lane 3) but not MBP- EB1C∆8 (lane 4) pulls down endogenous p150Glued. c Expression of EB1C∆8 impairs retrograde axonal transport. Comparison of Tf-QD distance versus time trajectories in GFP (green) and GFP-EB1C∆8-expressing neurons (orange). Fifty endosome trajectories are shown from representative microfluidic chambers. Note the separation of the populations. Student’s t test, n = 5 independent microfluidic chambers, ± is SEM. d Quantification of average speed of Tf-QDs in GFP and GFP- EB1C∆8-expressing neurons. GFP 1.370 ± 0.04 μm/s, GFP-EB1C∆8 0.8276 ± 0.66 μm/s. e Quantification of the % time spent paused. GFP 7.192 ± 1.352, GFP-EB1C∆8 24.35 ± 3.476 %. f Quantification of moving velocity of Tf-QD-containing endosomes. GFP 1.652 ± 0.03 μm/s, GFP-EB1C∆8 1.312 ± 0.05 μm/s. g, h A hypothetical model of the role of the SxIP motif protein BPAG1n4 in the coordination of axonal transport at plus ends. Briefly, endosome-bound BPAG1n4 interacts with EB1 through its SxIP domain at the MT plus end. This interaction brings the motor-cargo complex into proximity to the new MT, allowing switching. Preventing this interaction through overexpression of the isolated SxIP domain (EBBD) may lead to increased stalling. This model is not drawn to scale

Discussion

Efficient coordination of the axonal transport system is imperative for neuronal function and survival. BPAG1n4 plays an essential role in retrograde axonal transport by virtue of its direct interactions with the dynein/dynactin motor complex, through p150Glued, and with endosomes, via retrolinkin [14, 15]. However, the role of its C-terminal MT plus-end-binding domain (SxIP) in retrograde axonal transport has remained uncharacterized. In this study, we propose a new role for the SxIP motif-containing +TIPs such as BPAG1n4 in the maintenance of processive, i.e., smooth and unidirectional, retrograde axonal transport of endosomes.

Previous work has shown that the C-terminal domain of BPAG1n4 (EBBD) interacts directly with the +TIP EB1 [16]. Here, we show that endogenous BPAG1n4 interacts with EB1 at the microtubule plus end, placing it in the ideal location to co-ordinate retrograde axonal transport. We provide evidence that disruption of the interaction between EB1 and SxIP motif-containing proteins such as BPAG1n4, severely impairs the retrograde axonal transport of Tf-QD-containing endosomes, resulting in significantly increased endosome pausing and stalling. Both expression of an isolated SxIP motif domain (GFP-EBBD) that blocks the interaction of BPAG1n4 with EB1 as well as treatment with low concentrations of taxol, a drug that alters microtubule dynamics and results in EB1 dissociation from the MT plus end, severely impair retrograde axonal transport. Notably, expression of EB1C∆8-GFP, an EB1 peptide capable of interacting with SxIP motif +TIPs but not with the CAP-Gly domain-containing +TIP p150Glued, also resulted in impaired processive transport along the axon, further bolstering the importance of the accessibility of EB1 to SxIP motif proteins in the maintenance of transport along the axon. In contrast, recent studies have found that the plus-end localization of the CAP-Gly-containing +TIPs such as p150Glued, while important for cargo loading at the neurite tip or synapse, is not involved in the maintenance of processive axonal transport [10, 11, 13]. Together, this suggests that SxIP motif +TIPs may play a distinct role from the CAP-Gly domain-containing +TIPs such as p150Glued, and that the regulation of axonal transport requires the co-ordination of +TIPs playing separate, but complementary roles.

In contrast to our work on endosomal transport, a recent study reported that knockdown of EB1 and EB3 in DRG neurons did not impair the retrograde flux of LAMP1-positive lysosomes [13]. Numerous explanations are likely to underlie this apparent discrepancy. First, it is possible that lysosomes and endosomes utilize different mechanisms for regulating their transport. Indeed, lysosomes do not move as processively as endosomes; not only do lysosomes pause often, but they also frequently reverse direction [22]. Secondly, retrograde flux measures the number of cargo traversing a particular point over time, a population measure, while we have examined the dynamic behavior of individual cargo, for minutes and over longer distances, which is possibly a more sensitive measure. There are many other differences in our systems, including the use of exogenous cargo (Tf-QDs) versus the expression of a tagged protein (LAMP1-RFP), and the use of a microfluidic system, which ensures that transport is only initiated at the distal axon and not along the shaft of the axon so that all endosomes observed have traveled relatively equivalent distances. This discrepancy highlights the complexity of the mechanisms that regulate transport of cargoes through the neuron.

While intermittent pausing is a characteristic feature of retrograde endosomal transport in neurons, the molecular events that cause cargo pausing are unknown. One possible cause is the presence of an obstacle on the MT track. In vitro studies show that dynein motors pause or reverse direction when they encounter a patch of bound tau on a MT [27]. It has been speculated that pausing may also be associated with switching between two MT tracks [28, 29]. As axons are longer than any individual MT, endosomes must switch MT tracks quite often during transport. MT plus ends present an ideal scaffold for the coordinated transfer of endosomes from one MT to another, and +TIPs are well suited to play a role in facilitating this process.

The question remains as to the involvement of the SxIP-containing +TIPs in axonal transport. At least two potential (non-mutually exclusive) roles in this process are primarily apparent. First, it is possible that fine control of MT dynamics is required for the plus end to “capture” cargo from another MT. Indeed, we observed that treatment of DRG neurons with taxol, disrupting MT dynamics, impaired the processivity of endosome transport. However, it has been observed that the disruption of some +TIPs can alter MT dynamics, without causing a corresponding change in cargo trafficking [9]. In addition, we found that the expression of GFP-EBBD did not significantly alter MT dynamics as tip-tracking reflecting MT growth rates was similar to that reported in the literature [16, 20], suggesting that changes in MT lattice dynamics may not underlie the effect of GFP-EBBD expression on axonal transport. A second possibility is that a specific interaction between an SxIP motif protein and the motor-cargo complex may be required. A +TIP at the MT plus end may interact with a cargo receptor, recruiting the cargo onto the MT; alternatively, a cargo-associated SxIP motif protein may interact with EB1 at the plus end, which would also help load the complex onto a new MT. One likely candidate is BPAG1n4. Previous studies have shown that BPAG1n4 plays an essential role in retrograde axonal transport, and indeed, loss of BPAG1 severely disrupts the retrograde transport of transferrin in DRG neurons [14]. Based on our findings, we propose a conceptual model for the role of BPAG1n4 in endosomal transport (Fig. 4g, h). We suggest that during retrograde transport, when endosomes reach the minus-end of a MT, or encounter an obstacle, they attempt to switch to another MT track. In DRG neurons, the endosome-bound BPAG1n4 may contact EB1 family proteins at dynamic MT plus ends, bringing the dynein motor into close proximity with the new MT, allowing track switching and resumed transport. Disruption of this interaction impairs switching of the endosome to a new track, and results in a prolonged pause. This may not be the only mechanism for track switching or navigating around an obstacle, and thus delayed pause resolution may occur. While endosomes in control neurons also pause, these pauses are less frequent and of shorter duration. It is possible that endosomes in control neurons also pause whenever they switch MTs, and we simply do not have the time resolution to observe these brief navigations.

This model does not preclude a role for other SxIP motif +TIPs. Indeed, as BPAG1n4 is primarily expressed in sensory neurons [14], it is likely that other SxIP-containing +TIPs such as its homologue ACF-7, could play a role in other neuronal types. Future studies will be required to investigate the potential targets.

Our findings thus establish the MT plus end as an important location for the maintenance of processive retrograde axonal transport over long distances. We provide the first evidence implicating an interaction between the EB1 family and SxIP motif-containing +TIPs such as BPAG1n4 in the coordination of endosomal transport. Future research is warranted to determine the contributions of individual SxIP motif proteins, including full-length spectraplakins, in the maintenance of processive axonal transport in various cell types where they are endogenously expressed.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 (TIFF 20806 kb)

Supplementary material 2 (TIFF 30485 kb)

Supplementary material 3 (TIFF 15880 kb)

Supplementary material 4 (TIFF 24199 kb)

Supplementary material 5 (TIFF 15519 kb)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank W. J. Nelson for sharing constructs and S. A. Leal-Ortiz and C. C. Garner for assistance with lentivirus production. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01), March of Dimes foundation, and Stanford Graduate fellowship (M.K.).

Footnotes

M. Kapur, M. T. Maloney contributed equally.

References

- 1.Hirokawa N, Niwa S, Tanaka Y. Molecular motors in neurons: transport mechanisms and roles in brain function, development, and disease. Neuron. 2010;68:610–638. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Vos KJ, Grierson AJ, Ackerley S, Miller CCJ. Role of axonal transport in neurodegenerative diseases. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:151–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.061307.090711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akhmanova A, Steinmetz MO. Tracking the ends: a dynamic protein network controls the fate of microtubule tips. Nat Rev Mol Cell. 2008;9:309–322. doi: 10.1038/nrm2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixit R, et al. Microtubule plus-end tracking by CLIP-170 requires EB1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:492–497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807614106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Vaart B, et al. SLAIN2 links microtubule plus end-tracking proteins and controls microtubule growth in interphase. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:1083–1099. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201012179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Honnappa S, et al. An EB1-binding motif acts as a microtubule tip localization signal. Cell. 2009;138:366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li S, et al. Crystal structure of the cytoskeleton-associated protein glycine-rich (CAP-Gly) domain. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48596–48601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208512200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slep KC, et al. Structural determinants for EB1-mediated recruitment of APC and spectraplakins to the microtubule plus end. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:587–598. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200410114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lomakin AJ, et al. CLIP-170-dependent capture of membrane organelles by microtubules initiates minus-end directed transport. Dev Cell. 2009;17:323–333. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lloyd TE, et al. The p150Glued CAP-Gly domain regulates initiation of retrograde transport at synaptic termini. Neuron. 2012;74:344–360. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moughamian AJ, Holzbaur ELF. Dynactin is required for transport initiation from the distal axon. Neuron. 2012;74:331–343. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuster M, et al. Controlled and stochastic retention concentrates dynein at microtubule ends to keep endosomes on track. EMBO J. 2011;30:652–664. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moughamian AJ, Osborn GE, Lazarus JE, Maday S, Holzbaur ELF. Ordered recruitment of dynactin to the microtubule plus-end is required for efficient initiation of retrograde axonal transport. J Neurosci. 2013;33:13190–13203. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0935-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J-J, et al. BPAG1n4 is essential for retrograde axonal transport in sensory neurons. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:223–229. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200306075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu J-J, et al. Retrolinkin, a membrane protein, plays an important role in retrograde axonal transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2223–2228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602222104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapur M, et al. Calcium tips the balance: a microtubule plus end to lattice binding switch operates in the carboxyl terminus of BPAG1n4. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:1021–1029. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barth AIM, Siemers KA, Nelson WJ. Dissecting interactions between EB1, microtubules and APC in cortical clusters at the plasma membrane. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:1583–1590. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.8.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lois C, Hong EJ, Pease S, Brown EJ, Baltimore D. Germline transmission and tissue-specific expression of transgenes delivered by lentiviral vectors. Science. 2002;295:868–872. doi: 10.1126/science.1067081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor AM, et al. A microfluidic culture platform for CNS axonal injury, regeneration and transport. Nat Method. 2005;2:599–605. doi: 10.1038/nmeth777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stepanova T, et al. Visualization of microtubule growth in cultured neurons via the use of EB3-GFP (end-binding protein 3-green fluorescent protein) J Neurosci. 2003;23:2655–2664. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02655.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cui B, et al. One at a time, live tracking of NGF axonal transport using quantum dots. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13666–13671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706192104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lalli G, Schiavo G. Analysis of retrograde transport in motor neurons reveals common endocytic carriers for tetanus toxin and neurotrophin receptor p75NTR. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:233–239. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mimori-Kiyosue Y, Shiina N, Tsukita S. The dynamic behavior of the APC-binding protein EB1 on the distal ends of microtubules. Curr Biol. 2000;10:865–868. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00600-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammond JW, et al. Posttranslational modifications of tubulin and the polarized transport of Kinesin-1 in neurons. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:572–583. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-01-0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakata T, Yorifuji H. Morphological evidence of the inhibitory effect of taxol on fast axonal transport. Neurosci Res. 1999;35:113–122. doi: 10.1016/S0168-0102(99)00074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun D, Leung CL, Liem RK. Characterization of the microtubule binding domain of microtubule actin crosslinking factor (MACF): identification of a novel group of microtubule associated proteins. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:161–172. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dixit R, Ross JL, Goldman YE, Holzbaur ELF. Differential regulation of dynein and kinesin motor proteins by tau. Science. 2008;319:1086–1089. doi: 10.1126/science.1152993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mudrakola HV, Zhang K, Cui B. Optically resolving individual microtubules in live axons. Structure. 2009;17:1433–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross JL, Shuman H, Holzbaur ELF, Goldman YE. Kinesin and dynein-dynactin at intersecting microtubules: motor density affects dynein function. Biophys J. 2008;94:3115–3125. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.120014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1 (TIFF 20806 kb)

Supplementary material 2 (TIFF 30485 kb)

Supplementary material 3 (TIFF 15880 kb)

Supplementary material 4 (TIFF 24199 kb)

Supplementary material 5 (TIFF 15519 kb)