Abstract

The intracellular prolyl peptidase DPP9 is implied to be involved in various cellular pathways including amino acid recycling, antigen maturation, cellular homeostasis, and viability. Interestingly, the major RNA transcript of DPP9 contains two possible translation initiation sites, which could potentially generate a longer (892 aa) and a shorter version (863 aa) of DPP9. Although the endogenous expression of the shorter DPP9 form has been previously verified, it is unknown whether the longer version is expressed, and what is its biological significance. By developing specific antibodies against the amino-terminal extension of the putative DPP9-long form, we demonstrate for the first time the endogenous expression of this longer isoform within cells. Furthermore, we show that DPP9-long represents a significant fraction of total DPP9 in cells, under steady-state conditions. Using biochemical cell fractionation assays in combination with immunofluorescence studies, we find the two isoforms localize to separate subcellular compartments. Whereas DPP9-short is present in the cytosol, DPP9-long localizes preferentially to the nucleus. This differential localization is attributed to a classical monopartite nuclear localization signal (K(K/R)X(K/R)) in the N-terminal extension of DPP9-long. Furthermore, we detect prolyl peptidase activity in nuclear fractions, which can be inhibited by specific DPP8/9 inhibitors. In conclusion, a considerable fraction of DPP9, which was previously considered as a purely cytosolic peptidase, localizes to the nucleus and is active there, raising the intriguing possibility that the longer DPP9 isoform may regulate the activity or stability of nuclear proteins, such as transcription factors.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00018-014-1591-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: DPP9, DPP8, Prolyl peptidases, Nuclear localization signal

Introduction

Proteolytic enzymes that constitute 1–5 % of the human genome are involved in various important cellular pathways such as protein degradation, antigen maturation, and signaling. While many peptidases are redundant in their activity and selectivity, only a few can cleave a peptide bond following a proline residue because of its rigid ring structure (URL: http://merops.sanger.ac.uk; [1, 2]). Members of the S9B/DPPIV family are serine amino peptidases with the unique ability to cleave off N-terminal dipeptides from proteins/peptides having a proline residue at position 2 (XaaP). Four active members of this family are known so far: the two membrane-bound cell-surface members dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPPIV) and the Fibroblast activation protein alpha (FAP), as well as the two soluble members DPP8 and DPP9 (reviewed in [3–6]). Dimerization is a common feature for members of the S9B/DPPIV family [6–11] and is essential for enzymatic activity [12–16].

The most intensively studied member of this family is DPPIV, which was shown to function in the maintenance of glucose homeostasis (reviewed in [17]). The physiological roles of the two intracellular members of this family, DPP8 and DPP9 (ca. 60 % amino acid identity), are only emerging. Both peptidases are ubiquitously expressed on mRNA levels in various organs and tissues and cell lines [18–22]. Changes in the levels of these peptidases appear to be critical for cell survival, as both overexpression or application of DPP8/9 inhibitors lead to cell death in several cell lines [23–25]. Recently, it was shown that knock-in mice with a serine to alanine mutation in the active site of DPP9 die 8–24 h after birth. This publication demonstrates that DPP9 activity is essential for neonatal survival, whereby the reason leading to death of the mice is not known [26].

In a recent degradomics screen with DPP8/DPP9 overexpressing cells, peptides originating from Adenylate kinase 2 and Calreticulin were identified as novel candidate substrates for DPP8/DPP9, suggesting that DPP8 and/or DPP9 may have a role in cellular homeostasis and energy metabolism [27]. Silencing experiments show that DPP9 and not DPP8 is rate-limiting for the hydrolysis of proline-containing peptides in the cytosol suggesting that DPP9 may have a house-keeping role for amino acid homeostasis [28]. The first identified endogenous substrate of DPP9 was the tumor-related epitope RU134–42. Its hydrolysis by DPP9 results in its limited presentation on MHC class I molecules to the immune system linking DPP9 to the MHC class I antigen presentation pathway [28–30].

DPP9 is regulated on multiple levels. Recent data show that DPP9 interacts with SUMO1, and that SUMO1 acts as an allosteric regulator of this peptidase [31]. Additionally, DPP9 appears to be regulated on mRNA and protein levels. For example, DPP9 protein levels are increased upon differentiation of monocytes to macrophages [24]. Increases in mRNA levels of DPP9 are detected in inflamed lungs and chronic lymphocytic leukemia [32, 33].

In addition, several transcripts of DPP9 were reported, however their physiological roles are currently unknown. Interestingly, the major DPP9 RNA transcript of 4.4 kb contains two possible translation initiation sites, which could generate a longer version (892 aa) and a shorter version (863 aa) of DPP9 [8, 19, 20]. In recent years, it was a matter of debate whether both DPP9 isoforms, long and short, are expressed on protein level in cells and whether they are active. The shorter version of DPP9 was initially identified by Olsen and Wagtmann [20]. Cloning and expression of this short DPP9 version (863 aa) in mammalian cell culture verified that DPP9-short is active and is localized to the cytosol [19, 21]. Importantly, DPP9-short was recently purified from bovine testes, confirming the endogenous expression of this short DPP9 isoform [34]. Bjelke et al. [8] were the first to express a recombinant variant of the longer DPP9 form in insect cells (892 aa), and show that it is active. Surprisingly, in their study, the authors reported that the shorter DPP9 variant was inactive, suggesting that the N-terminal extension would affect the enzymatic activity of the peptidase. Clearly, a systematic comparison of both DPP9 forms is missing. Moreover, it is not known whether an endogenous long DPP9 isoform is at all expressed in cells and if so, whether it would differ from the shorter DPP9 version for example in activity or localization.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and transfection

HeLa P4 cells [35] were cultured at 37 °C and 5 % CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were transfected at a confluency of 50–60 % using the calcium phosphate method and were analyzed 48 h after transfection. The total amount of DNA used for transfection depended on the relative surface area of culture dishes used in the respective experiment. For cells grown on 15-cm culture dishes, 60 μg of DNA was transfected, and for other dish sizes, the amount was scaled according to the surface area. For control, cells were transfected without DNA (Mock). For down-regulation of DPP9 and DPP8, HeLa cells were transfected with the following siRNA oligonucleotides (Invitrogen) essentially as previously described [28]: DPP9-1 (UGCACUUUCUACAGGAAUA) DPP9-2 (GCCACCAAGGUUUAUCCAA), DPP9-3 (GGAUCAAUGUUCAUGACAU), DPP9-4 (GGAGAAGCUUCUCGCUGAA) and DPP8 (UGACGCCACUAAUUAUCUA). For control, cells were transfected with a non-targeting siRNA oligonucleotide. Cells were analyzed 72 h after transfection. Total cell extracts using total buffer (please see text below) were prepared and the protein content was measured.

Antibodies

For Western blotting, the following antibodies and dilutions were applied: mouse anti-β-tubulin (#ab7792, 1:2,000), rabbit anti-DPP9 (#ab42080, 1:1,000), rabbit anti-DPP8 (#ab42077, 1:1,000), and rabbit anti-POP (#ab58988, 1:1,000) were purchased from Abcam. Rabbit Anti-DPPIV (CD26) (#sc9153, 1:500) was purchased from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Antibodies against rabbit LaminA/C (#2032; 1:1,000) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Rabbit anti-VDAC (voltage-dependent anion channel) was a kind gift from Prof. Dr. Peter Rehling (1:2,000). Goat anti-DPP9-long antibodies were produced for us by GenScript, against a peptide corresponding to the N-terminal extension of DPP9-long (RKVKKLRLDKENTGSWRSFSLNSEGAER) (1:1,000). Horseradish peroxidase-coupled donkey-anti-goat (1:5,000), donkey-anti-mouse (1:10,000) or donkey-anti-rabbit (1:10,000–1:20,000) immunoglobulin G (Dianova GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) were used as secondary antibodies. The enhanced chemiluminescence system (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) was used for visualization of proteins on the membranes. For immunofluorescence studies, rabbit anti-DPP9 (ab42080; 1:70) and rabbit anti-DPP8 (ab42077; 1:50) from Abcam were used. Additional antibodies for immunofluorescence: rabbit anti-HA (H6908; 1:400) and mouse anti-FLAG (F1804; 1:400) from Sigma, goat anti-RanBP-2 (1:1,000)—a kind gift from Prof. Dr. Frauke Melchior. Secondary antibodies for immunofluorescence: donkey anti-mouse Alexa-Fluor-488, donkey anti-goat Alexa-Fluor-488 and donkey-anti-rabbit Alexa-Fluor-594, all at a dilution of 1:500; purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, Oregon, USA).

Inhibitors

The DPP8/9-specific inhibitor 1G244 was purchased from AK Scientific (Union City, CA, USA), first described in [36].

Plasmids

For production of recombinant DPP9-long protein: DPP9-long was subcloned into a pFASTBacHT plasmid (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) essentially as previously described for DPP9-short [31]. For transfection into HeLa cells: HA- or FLAG-tagged DPP9-long and -short forms were cloned into pcDNA3.1 vector (using the BamHI and NotI restriction sites). Single, double, and triple point mutations, and the NLS-deletion were introduced using primers for site-directed mutagenesis. The DPP9-short mutant containing the NLS at its N-terminus was generated using a 5` DPP9-short primer with the NLS elongation (MRKVKKLRL) and DPP9-short plasmid as template. The PCR fragment was cloned into pcDNA3.1 (using BamHI and NotI restriction sites). All plasmids were sequenced before usage.

Recombinant protein expression and purification

Recombinant DPP9-long and DPP9-short were expressed in SF9 insect cells and purified essentially as described in [31].

Indirect immunofluorescence and microscopy

HeLa cells were grown on Poly-l-lysin-coated coverslips. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were fixed with 4 % formaldehyde in PBS (phosphate buffered saline) containing 10 μg/ml Hoechst 33,258 (Molecular Probes) for staining of the nuclei. Subsequently, cells were permeabilized with 0.2 % Triton-X-100 in PBS, washed, and blocked for 10 min in blocking buffer (2 % BSA (bovine serum albumin) in PBS). Cells were then treated with primary antibodies (concentrations described in antibody section) for 90 min at 37 °C. Following a PBS wash, cells were then incubated for 45 min at room temperature with the respective secondary antibodies. After careful washing with PBS and water, cells were mounted in fluorescent mounting medium (DAKO). Control samples were treated with secondary antibody only, to estimate background staining. Cells were analyzed and images were taken using a LSM 510-Meta confocal microscope, oil immersion objective 63 × /1.3 (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc., USA). For z-stacks, serial images were taken at every 0.5 μm z-stacks. Images were processed using the LSM image Browser (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc., USA) and Adobe Photoshop.

For quantification of subcellular localization of DPP9-long and -short, cells were grouped into the following three categories: N>C (stronger signals in the nucleus), N=C (equal signal intensities in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm), and C>N (stronger signals in the cytosol). Quantification was essentially performed as described in [37]. In short, graphs are a result of at least two independent experiments, each in duplicates, and each single experiment contained more than 340 cells. Cells that were counted showed similar expression levels of the respective DPP9 protein being counted.

Subcellular fractionation

Subcellular fractionation was essentially performed as described in [38, 39]. To allow the analysis of these subcellular fractions by Western blotting and also for peptidase activity, protease inhibitors were omitted. In short, HeLa cells grown on a 15-cm culture dish were trypsinized, washed with PBS, and centrifuged at 600 × g, at 4 °C for 8 min. For analysis of total cellular proteins: one-third of the cell pellet was resuspended in ice-cold Total buffer [50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1 % IGEPAL, 0.5 % Na-deoxycholate, 0.1 % SDS, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and benzonase (1 U/ml; Sigma)], incubated at 4 °C for 1 h and centrifuged at 600 × g, 4 °C for 6 min. For subcellular fractionation, the residual two-thirds of the cell pellet was resuspended in ice-cold hypotonic buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 % Triton-X-100, 1 mM DTT), incubated on ice for 10 min and centrifuged at 600 × g, at 4 °C for 6 min. The supernatant comprising the cytosol-enriched fraction was collected. The remaining pellet was washed once in hypotonic buffer and then resuspended in Membrane buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 % IGEPAL and 1 mM DTT). After 15-min incubation on ice, the sample was centrifuged at 600 × g, at 4 °C for 6 min and the resulting supernatant was collected. This step is important in order to obtain pure nuclei fractions without contamination of other membrane organelles. The supernatant contains membrane-bound organelle proteins. The remaining pellet was then washed once in Membrane buffer and resuspended in Total buffer. After 1-h incubation at 4 °C, samples were centrifuged at 600 × g, at 4 °C for 6 min, the resulting supernatant comprising the nuclear fraction was collected. Protein content of the various fractions was measured and the fractions were either used for kinetic assays (see below) or were boiled in SDS sample buffer for Western-blot analysis.

Size exclusion chromatography

Purified recombinant (200 nM) DPP9-long or DPP9-short in TB buffer (if not stated otherwise) were loaded on an analytical Superdex 200 column (General Electric, Fairfield, CT, USA) for size exclusion chromatography. The UV absorbance at A280 nm was measured and 0.5-ml fractions were collected. For control, Bio-Rad’s (Hercules, CA, USA) gel filtration standard in TB buffer were loaded. Output data of the gel filtration were exported and elution profiles were generated using GraphPad Inc. Prism software with ml on x-axis and mAU (A280 nm) on the y-axis.

Kinetic assays

Kinetic assays were essentially performed as described in [31]. In short, for determination of K cat and K m, 12.5 nM purified recombinant DPP9 (short or long) was incubated with varying concentrations of XaaPro-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (XP-AMC) in TB buffer (20 mM HEPES/KOH, pH 7.3, 110 mM potassium acetate, 2 mM magnesium acetate, 0.5 mM EGTA) supplemented with 0.02 % Tween 20, 1 mM DTT. DPP9-long activity in the different fractionation buffers (hypotonic buffer, membrane buffer, Total buffer) containing various detergents was analyzed by pre-incubating 25 nM recombinant DPP9-long in the respective fractionation buffer for 4 h (this is the equivalent time needed for fractionation). Next, DPP9 was diluted in TB buffer including 1 mM DTT, resulting in a 12.5-nM final concentration per reaction and cleavage of various concentrations of GP-AMC was assayed. To determine the Ki of the DPP8/9-specific inhibitor 1G244 (AK Scientific) in the different fractionation buffers, 12.5 nM of DPP9-long was incubated as described above in the different buffers. Following incubation, varying concentrations of 1G244 were added (0, 10, 100, and 1,000 nM). To measure DPP activity of the different subcellular fractions, 5 μg protein extract was incubated with varying concentrations of GP-AMC. For assays in the presence of 1G244, 5 μg of protein extract was incubated with 1 μM 1G244 for 30 min on ice before the addition of various concentrations of GP-AMC. In all cases, fluorescence release was measured using the Appliskan microplate fluorimeter (Thermo Scientific) with 380-nm (excitation) and 480-nm (emission) filters and SkanIt software and analyzed using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Each experiment was performed at least three times, in triplicates.

Results

DPP9-long is expressed in HeLa cells

DPP9 pre-mRNA consists of 22 exons containing two putative translation initiation sites, one at exon three, generating a longer (892 aa) and one at exon four generating a shorter (863 aa) DPP9 variant (Fig. 1a). Consequently, the two versions of DPP9 would differ in their amino terminus, where the longer DPP9 isoform contains an additional stretch of 29 residues (Fig. 1b and supplementary Fig. S1A for full alignment). Currently, it is unknown whether the endogenous DPP9-long form (DPP9-l) is at all expressed in cells on protein level. To address this question, we developed specific antibodies targeting the N-terminal extension present only in DPP9-l (Fig. 1c). First, we confirmed that the anti-DPP9-l antibody indeed recognizes recombinant DPP9-l, but not recombinant DPP9-short (DPP9-S), by immunoblotting against both proteins which were cloned, expressed and purified from Sf9 insect cells (Fig. 1d, e, upper gel). Since the two forms differ in only in 3.3 kDa, they are recognized as a single band by the DPP9 (total) antibody (Fig. 1e, lower gel).

Fig. 1.

DPP9-long form is expressed in HeLa cells. a Scheme of exon–intron structure of DPP9 showing the ATG for the long and short versions. b Protein sequence alignment of the short and long versions of DPP9. c Epitopes of antibodies used in this study. d Coomassie staining of various amounts of recombinant DPP9-l and DPP9-S, expressed and purified from Sf9 insect cells. e Defined concentrations of recombinant (rec.) DPP9-S and DPP9-l were separated on SDS PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting either with anti-DPP9 (long) antibody (upper gel) or with the DPP9 (total) antibody (lower gel). f Defined concentrations of recombinant (rec.) DPP9-l and total HeLa cell extracts were separated on SDS PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with DPP9 (long) antibodies. g Total cell extract (10 μg per lane) from HeLa cells silenced for DPP9 using four different siRNAs were separated on SDS PAGE and analyzed with the DPP9 (long) antibody. Cells treated with non-targeting siRNA were used for control. Tubulin was blotted as a loading control. This assay was performed at least three times, shown is a representative blot

To test whether DPP9-l is indeed expressed in cells at steady state, different amounts of HeLa cell extracts and defined concentrations of recombinant DPP9-l for normalization of the antibody were subjected to immunoblotting with DPP9-l antibodies (Fig. 1f). Importantly, as shown in Fig. 1f, the DPP9 (long) antibody recognizes a major band, corresponding in size to DPP9-l (ca. 100 kDa, estimated MW 102 kDa) (Fig. 1f) and additional higher molecular weight bands. To test whether these bands indeed correspond to DPP9, we down-regulated the peptidase in HeLa cells using four alternative DPP9 siRNA oligonucleotides, and a non-targeting siRNA oligonucleotide for control. Analysis of these cell lysates with the DPP9 (long) antibody shows that the intensity of these bands is reduced upon DPP9 silencing, demonstrating that they correspond to DPP9-l (Fig. 1g). A similar pattern was also observed with the DPP9 (total) antibody (Supplementary Fig. S1B). The nature of these higher molecular bands is currently not known, but may represent modification of the peptidase. Taken together, these results show for the first time that the DPP9-L protein is indeed expressed and present on protein level in HeLa cells.

DPP9-l is an active peptidase

Until now there are several contradictory reports regarding the activity of both DPP9 forms, and a systematic comparison between their catalytic properties is missing. Therefore, as a starting point, we compared the activity of recombinant DPP9-l and DPP9-S, expressed and purified from insect cells. This was done by measuring the release of fluorescent AMC from various DPP model substrates Xaa-Pro-AMC (XP-AMC). Results from this analysis validate that both enzymes are active and comparable in their kinetic properties (Fig. 2a). Since DPP9-S is known to form dimers, we asked whether DPP9-l behaves in a similar manner by comparing the elution profile of both enzymes on size exclusion chromatography. In line with previously published results [8, 11, 31], DPP9-S eluted from the gel filtration column in a single peak corresponding in size to a dimer (Fig. 2b). Importantly, the elution profile of recombinant DPP9-l was identical to that of DPP9-S, corresponding in size to a DPP9-l dimer. Taken together, we conclude that recombinant DPP9-l and DPP9-S are similar in their biochemical properties and enzymatic activity in vitro.

Fig. 2.

DPP9-l is active. a Table summarizing the calculated K cat, K m, and K cat /K m results for the cleavage of several DPP9 substrates by 12.5 nM recombinant DPP9-S and DPP9-l. Assays were performed in triplicates and repeated at least three times. Values were calculated using non-linear regression (GraphPad Inc. Prism software). b Elution profiles of 200 nM recombinant DPP9-l and DPP9-S on a gel exclusion chromatography, using analytical Superdex S200. As size standard, Bio-Rad’s gel filtration standard was used. Profiles were generated using GraphPad Inc. Prism software with ml on the x-axis and UV absorbance (mAU 280 nm) on the y-axis. This experiment was repeated three times, shown is a representative. c Scheme of HA-tagged DPP9-l and DPP9-S constructs used for overexpression in HeLa cells for subsequent immunofluorescences, subcellular fractionation experiments, and cleavage-activity assays. d DPP activity was measured from HeLa cell extracts (5 μg) expressing HA-tagged DPP9-l or DPP9-S. The experiment was performed in triplicates, including error bars. e Western blots of lysates (10 μg) from HeLa cells overexpressing HA-tagged DPP9-S or DPP9-l developed with DPP9 (total) antibodies to detect both isoforms, or DPP9 (long) antibodies to detect only DPP9-l. Tubulin was used as loading control. Shown are the blots for the corresponding activity assays shown in d

Next, we cloned HA-tagged versions of DPP9-l and DPP9-S for expression in HeLa cells (Fig. 2c). Following transfection, cells were lysed in the absence of protease inhibitors (Fig. 2d, e) and tested for prolyl peptidase activity by measuring the cleavage of GP-AMC. Overexpression of either DPP9-S or DPP9-l, which was confirmed by Western blotting, clearly increased the capacity of the lysates to hydrolyze GP-AMC in comparison to lysates from mock-transfected cells (Fig. 2d, e), demonstrating that both DPP9 forms are active in lysates.

DPP9-l mainly localizes to the nucleus

Having shown that both DPP9-l and DPP-S are active both as recombinant enzymes and in transfected lysates, next we compared their cellular localization. To this end, cells were transfected with the tagged versions of the long or short isoform (scheme of constructs in Fig. 2c) and analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence using antibodies against the HA tag. Surprisingly, we found that in contrast to DPP9-S, which as expected localized to the cytosol, DPP9-l was mostly in the nucleus (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 2a for controls). Furthermore, when cells were transfected simultaneously with N-terminal FLAG-tagged DPP9-l and N-terminal HA-tagged DPP9-S, the two pools of DPP9-S and DPP9-l were clearly localized in two separate compartments, where the long form was in the nucleus, and the short in the cytosol (Fig. 3b). Next, we quantified the subcellular localization of DPP9-S and DPP9-l by grouping transfected cells into three categories as follows: (1) Stronger signals in the nucleus (N>C). (2) Equal signal intensities in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm (N=C) or (3) Stronger signals in the cytosol (C>N) (Fig. 3c). While DPP9-S was excluded from the nucleus, showing a clear cytosolic signal, DPP9-l mainly localized to the nucleus, where ca. 95 % of DPP9-l transfected cells showed clearly a stronger signal in the nucleus than in the cytosol (Fig. 3c; Table 1). The preferential nuclear localization of DPP9-l was also tested biochemically by cellular fractionation assays of cells transfected with either DPP9 form. To test for successful nuclear preparation, fractions were blotted against Lamin A/C, whereas tubulin was assayed as a cytosolic marker (Fig. 3d). In line with the immunofluorescence results shown above, DPP9-l but not DPP9-S was detected in the nuclear fraction (N) using the DPP9 (total) antibody (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Fig. 2B for corresponding activity).

Fig. 3.

DPP9-l localizes to the nucleus and is active there. a HeLa cells transfected with HA-tagged DPP9-l or DPP9-S were subjected to indirect immunofluorescence using confocal microscopy for detection of the HA tag. Simultaneously cells were also analyzed for endogenous RanBP2 as a marker protein for the nuclear rim. Hoechst staining was applied to visualize the nucleus. Assays were performed at least three independent times. Shown is a representative image. For control, cells were stained only with secondary antibody (Supplementary Fig. S2A). b HA-tagged DPP9-S and FLAG-tagged DPP9-l were simultaneously overexpressed in HeLa cells and subjected to indirect immunofluorescence, detecting the HA tag and the FLAG tag as described in a. c Chart showing the subcellular distribution of DPP9-l and DPP9-S. For quantification of subcellular localization, transfected cells were grouped into the following three categories: N>C (stronger signals in the nucleus), N=C (equal signal intensities in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm), and C>N (stronger signals in the cytosol). Quantification was performed from at least two independent experiments, from at least four slides with more than 400 cells expressing the respective DPP9 protein being counted using the HA antibody for detection. d DPP9-l or DPP9-S-transfected HeLa cells were subjected to subcellular fractionation (T totals, C cytosolic fraction, M membranous fraction, and N nuclear fraction) followed by Western-blot analysis of 10 μg of each fraction using the commercial Abcam DPP9 (total) antibody. Lamin A/C was used as a marker for the nuclear fraction, tubulin as a marker for the cytosolic fraction. Note that no protease inhibitors were used during the fractionation procedure to enable subsequent DPP9 activity measurements in the various fractions (Supplementary Fig. S2B). The faster migrating band of Lamin A/C represents a degradation product of this protein due to the lack of protease inhibitors. Shown is one representative result of at least three independent experiments. e 3D stack of a nucleus of a HeLa cell overexpressing the long form of DPP9. Serial confocal images (every 0.5 μm) of a Z-stack with merge signals are shown. RanBP2 is used as a marker for the nuclear rim showing that DPP9-l is localized within the nucleus. f DPP9-l is localized within the nucleus and not at the outer nuclear rim. DPP9-l-overexpressing HeLa cells were fixed and permeabilized by 0.01 % Digitonin so that the nuclear membrane stayed intact. Cells were subjected to indirect immunofluorescence, detecting the HA tag. Protein localizations were analyzed as described in a. g HeLa cells transfected with HA-tagged DPP9-l were analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence using the commercial antibody (DPP9 total), which detects both DPP9 forms. Simultaneously, cells were also analyzed for endogenous RanBP2 as a marker protein for the nuclear rim. Hoechst staining was applied to visualize the nucleus. Assays were performed at least three independent times. Shown is a representative image. h HA-tagged DPP9-l was mutated in the start methionine of DPP9-S and replaced by an Alanine (DPP9-l M30A). The localization of this mutant in HeLa-overexpressing cells was analyzed as in g

Table 1.

Subcellular localization of DPP9-S, DPP9-l, and various DPP9 mutants

| Nucleus > cytosol (%) | Nucleus = cytosol (%) | Cytosol > nucleus (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DPP9-l | 94.6 ± 7.9 | 5.4 ± 8.0 | 0 ± 0.1 |

| DPP9-l ΔNLS | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 100 ± 0 |

| DPP9-l K5AK6AR8A | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 0 ± 0 | 99.8 ± 0.3 |

| DPP9-l R2AK3A | 94.9 ± 7.6 | 3.9 ± 6.2 | 1.2 ± 1.4 |

| DPP9-l R8A | 4.4 ± 6.1 | 36.8 ± 30.6 | 58.8 ± 32.7 |

| DPP9-l R2A | 96.3 ± 4.6 | 1.6 ± 1.5 | 2.0 ± 5.2 |

| DPP9-S | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 100 ± 0 |

| DPP9-S + NLS | 92.5 ± 18.6 | 5.8 ± 13.9 | 1.7 ± 4.7 |

For quantification of subcellular localization, transfected cells were grouped into the following three categories: N>C (stronger signals in the nucleus), N=C (equal signal intensities in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm) and C>N (stronger signals in the cytosol). Quantification was performed from at least two independent experiments, from at least four slides with more than 340 cells expressing the respective DPP9 protein being counted

We further analyzed the nuclear localization of DPP9-l and tested whether it is present within the nucleus or alternatively on the outside, associated with the nuclear rim. Therefore, HA-DPP9-l-overexpressing cells were subjected to immunofluorescence using simultaneously antibodies against the nuclear rim protein RanBP2 and the HA tag. 3D stacks of magnified nuclei of positively transfected cells showed that neither of the proteins co-localize (Fig. 3e). Furthermore, fixed HA-DPP9-l-overexpressing cells were permeabilized with Digitonin instead of Triton-X-100. This procedure results in the permeabilization of the plasma membrane but keeps the nuclear membrane intact. Consequently, proteins within the nucleus will not be visualized, since antibodies cannot enter this compartment. As shown in Fig. 3f, following the digitonin treatment, no nuclear DPP9-l signals were detected in cells expressing HA-DPP9-l, while RanBP2 was still visible at the nuclear rim (Fig. 3f). Taken together, these results show that DPP9-l is indeed a nuclear protein.

Since the construct for DPP9-l overexpression also contains the start methionine for translation initiation of DPP9-S, we asked whether the short form is translated simultaneously in cells transfected with the HA-DPP9-l construct, due to a leaky scanning mechanism. To test this, we subjected DPP9-transfected HeLa cells to indirect immunofluorescence by using the commercial (DPP9 total) antibody detecting both isoforms (Fig. 3g). No significant difference was found between detection with HA or with commercial antibodies: ca. 91.4 % of the DPP9-L-transfected cells had stronger signals in the nucleus compared to the cytosol, and ca. 8.6 % of the cells showed equal signal intensities in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm. Furthermore, to avoid possible simultaneous DPP9-S translation, we generated a DPP9-l mutant, in which the start methionine of DPP9-S at position 30 in the DPP9-l construct was mutated to an alanine (M30A). Cells were then transfected with this DPP9-l M30A construct and subjected to indirect immunofluorescence using again the DPP9 (total) antibody (Fig. 3h). Similar results were obtained as with the DPP9-l construct (Fig. 3a, h): 91.5 % of DPP9-l M30A-transfected cells displayed stronger signals in the nucleus compared to the signals in the cytosol, and at about 8.5 % of the cells showed equal signal intensities in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm. These results suggest that DPP9-S is not translated at the same time as DPP9-l, arguing against leaky scanning.

The N-terminal elongation of DPP9-l contains a functional NLS

How is the separation in the cellular localization of DPP9-l and DPP9-S formed? Two scenarios can explain the formation of these two pools. In one scenario, both forms enter the nucleus, but DPP9-S has a stronger nuclear export signal (NES) thus enriching the protein in the cytosol. In an alternative model, only DPP9-l enters the nucleus due to the presence of a nuclear localization signal (NLS), which is missing in the short form. If the separation in the localization of the two DPP9 isoforms is due to a stronger export of the DPP9-S variant from the nucleus, then inhibition of nuclear export should lead to accumulation of DPP9-S in this compartment. We tested this hypothesis by treating cells with leptomycin B (LMB), a well-characterized inhibitor of the main export factor CRM1 (exportin 1). Also after this treatment, DPP9-S was not detected in the nucleus (supplementary Fig. S2C), arguing against a strong export of this form but instead suggesting that DPP9-S does not enter this compartment.

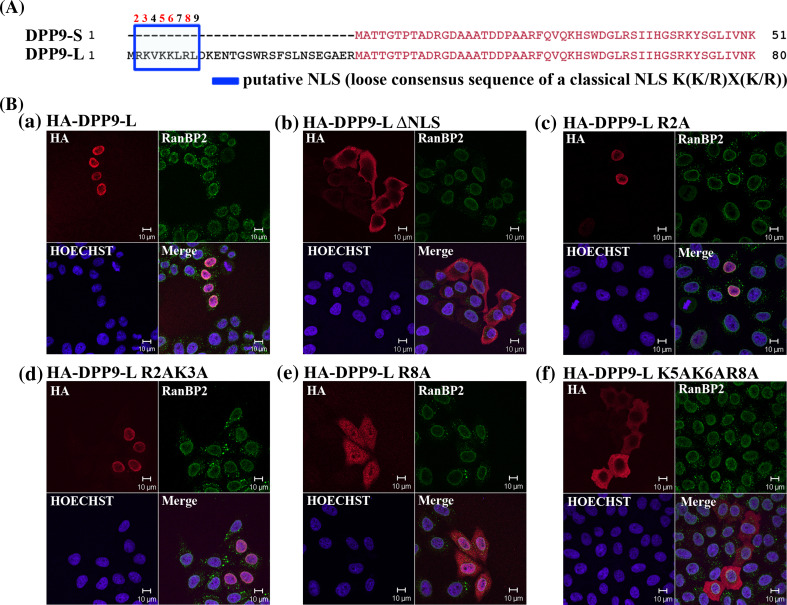

Next, we screened for an NLS in DPP9-l using the cNLS mapper program, which predicts importin α-dependent nuclear localization signals [40]. Using this program we identified a putative classical monopartite NLS: 2-RKVKKLRL-9 (consensus sequence = K(K/R)X(K/R), which is located in the amino terminal extension of DPP9-l (Fig. 4a). To test whether this putative NLS is functional in targeting DPP9-l to the nucleus, we constructed a DPP9-l deletion mutant lacking this putative NLS. Wild-type DPP9-l and the DPP9-LΔNLS mutant were transfected into cells and tested for their subcellular localization by indirect immunofluorescence. As shown in Fig. 4b, deletion of this putative NLS completely abolishes the nuclear localization of DPP9-l, demonstrating that the sequence RKVKKLRL is indeed essential to target this protein into the nucleus (Fig. 4Ba, b; Table 1 for quantification).

Fig. 4.

The N-terminal elongation of DPP9-L contains a functional nuclear localization sequence (NLS). a Protein sequence alignment of the N-termini of DPP9-S and DPP9-l with the NLS RKVKKLRL boxed in blue. b The NLS including the three for nuclear localization essential basic amino acids K5K6R8 targets DPP9-l to the nucleus. HA-tagged DPP9-l and various DPP9-l NLS mutants were overexpressed in HeLa cells and subjected to indirect immunofluorescence, detecting the HA tag and simultaneously RanBP2, a marker protein for the nuclear rim. Nuclei were visualized by Hoechst. Shown is a representative image from at least three independent experiments

To identify which residues within this NLS are important for nuclear import, several DPP9-l mutants in the NLS sequence were constructed and analyzed for cellular localization. We found that mutation of arginine at position 2 and lysine at position 3 to an alanine, had only a minor effect on the localization of DPP9-l, thus excluding these residues as necessary to target DPP9-l into the nucleus (Fig. 4Bc, d; Table 1). On the other hand, a single mutation of arginine at position 8 into an alanine resulted in a changed localization pattern of DPP9-L, which was now predominantly localized to the cytosol (Fig. 4Be; Table 1). Moreover, simultaneous mutation of the three basic residues at position 5, 6, and 8 of the NLS (K5K6R8) to an alanine, strongly shifted the localization of this mutant into the cytosol (Fig. 4Bf; Table 1). Taken together, we conclude that three basic residues lysine 5, lysine 6, and arginine 8 are essential for the localization of DPP9-L to the nucleus (Fig. 4B; Table 1).

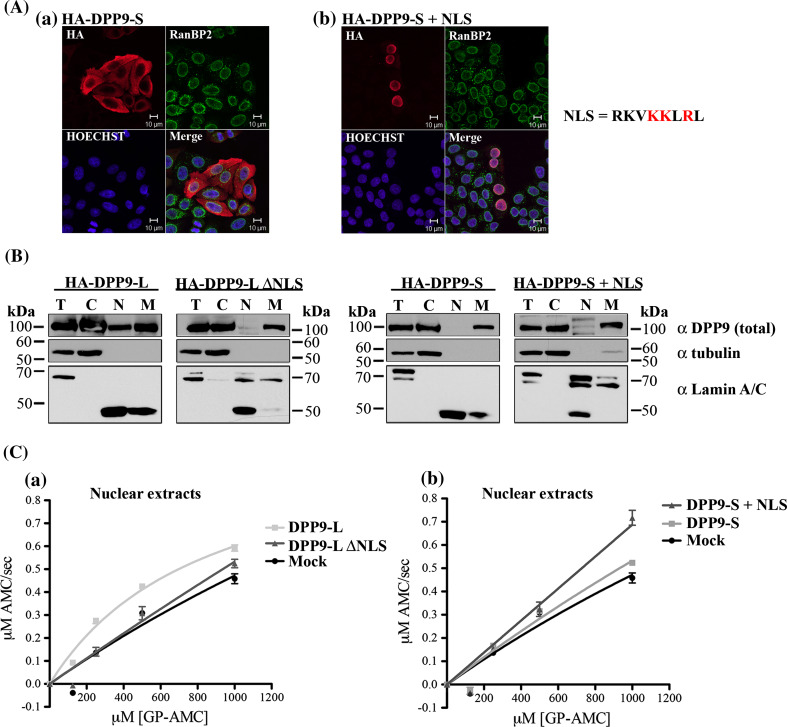

To further test whether the RKVKKLRL is a functional NLS, this sequence was fused directly to the N-terminus of DPP9-S, and its subcellular localization was first investigated by immunofluorescence (Fig. 5a). As shown in Fig. 5a, fusion of the RKVKKLRL sequence to the amino terminus of DPP9-S + NLS is sufficient to determine a nuclear localization for this construct. Quantification of these assays estimate that ca. 92 % of the monitored cells had stronger signals of DPP9-S + NLS in the nucleus than in the cytosol (Fig. 5a; Table 1). The importance of this NLS for localization of DPP9 in the nucleus, was also tested by subcellular fractionation assays. Consistent with the immunofluorescence data, DPP9-l and DPP9-S + NLS were detected in nuclear extracts of HeLa cells overexpressing these constructs, whereas DPP9-S and DPP9-lΔNLS were absent from the nuclear fractions (Fig. 5b, full scans in supplementary Fig. S3A&B). Furthermore, we tested whether targeting of DPP9 to the nucleus results in higher DPP activity in this compartment by measuring the GP-AMC hydrolysis. Nuclear extracts prepared from HeLa cells expressing DPP9-l or DPP9-S + NLS exhibited a higher AMC release compared to nuclear fractions prepared from DPP9-S or DPP9-lΔNLS expressing cells (Fig. 5c). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the amino terminus of DPP9-l contains a NLS that is essential to target the protein into the nucleus, where it can also be active.

Fig. 5.

The NLS sequence RKVKKLRL is sufficient to target DPP9 to the nucleus, where it is active. a HA-tagged DPP9-S (HA-DPP9-S) and DPP9-S fused to the NLS of long (RKVKKLRL) at its N-terminus (HA-DPP9-S + NLS) were overexpressed in HeLa cells and subjected to indirect immunofluorescence, detecting the HA tag and simultaneously RanBP2, a marker protein for the nuclear rim. Nuclei were visualized by Hoechst. Shown is a representative image from at least three independent experiments. b HeLa cells were transfected with the corresponding constructs and subjected to subcellular fractionation (T totals, C cytosolic fraction, N nuclear fraction, and M membranous fraction). A total of 10 μg of each fraction was analyzed by Western blotting using the commercial Abcam DPP9 (total) antibody. The nature of the slower migrating bands (ca. 120 kDa) interacting with the DPP9 antibody may represent putative modification of DPP9. Lamin A/C was used as a marker for the nuclear fraction, tubulin as a marker for the cytosolic fraction. The faster migrating band of Lamin A/C represents a degradation product of this protein. Note that protease inhibitors were omitted from the fractionation procedure to enable subsequent DPP9 activity measurements in the various fractions. Shown is a representative of at least three independent experiments (full scans in supplementary Fig. S3). c A total of 10 μg of HeLa nuclear fractions from (B) was analyzed for GP-AMC hydrolysis. The experiment was performed at least three times, each time in triplicates. Shown is a representative Michaelis–Menten analysis, including error bars

Subcellular localization and activity of DPP8 and DPP9: prolyl peptidase activity is not restricted to the cytosol

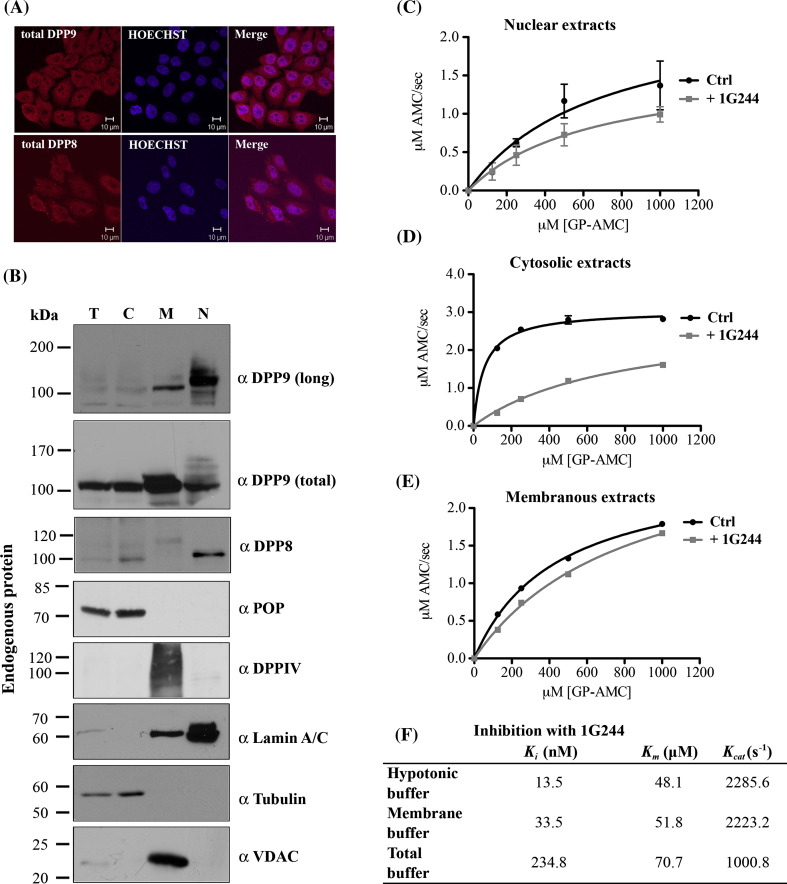

Having shown the nuclear localization of DPP9-l in overexpressing cells, next we asked whether this reflects the localization of endogenous DPP9 to this compartment. First we investigated the intracellular localization of endogenous DPP9 by immunofluorescence microscopy. Using the commercial DPP9 (total) antibody that recognizes both forms, we detect a positive signal for DPP9 both in the cytosol and nucleus (Fig. 6a). Next, we examined subcellular fractions of untransfected cells for the localization of endogenous DPP9 by Western blotting with the DPP9 (total) antibody (Fig. 6b). To control integrity and purity of the fractionation assay, we blotted for tubulin as a cytosolic marker, Lamin A/C as a nuclear marker and VDAC (voltage-dependent anion channel) as a membranous marker (Fig. 6b, full scan in supplementary Fig. S4A). In these assays, consistent with the immunofluorescence images, we find that endogenous DPP9 is not restricted to the cytosol, but a significant proportion of DPP9 is also found in fractions corresponding to membranous proteins and the nuclear proteins (Fig. 6b). Since this cell fractionation protocol does not separate the different membrane organelles, the nature of the membrane fraction containing DPP9 is currently unknown. However, Western blotting of these samples with the DPP9 (long) antibody show that DPP9-l is highly enriched in the nuclear fraction and only scarcely detected in fractions corresponding to the cytosol or membrane/membranous organelles (Fig. 6b), showing a similar distribution as the nuclear marker Lamin A/C. These results suggest that DPP9 found in the cytosolic and membranous fractions does not include DPP9-l, which is concentrated to the nucleus.

Fig. 6.

Endogenous DPP9-long localizes to the nucleus and is active there. a Localization of endogenous DPP9 and DPP8 in HeLa cells was analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence using the Abcam commercial antibodies targeting the catalytic domains of these peptidases: α DPP9 (total) (#ab42080) and α DPP8 (#ab42077). Nuclei were visualized by Hoechst staining. Shown is a representative of at least three independent experiments. b HeLa cells were subjected to subcellular fractionation and 10 μg of each fraction were analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies for members of the DPPIV family: α DPP9 (long), Abcam α DPP9 (total) (#ab42080), α DPP8 (#ab42077) and α DPPIV. Fractions were labeled as follows: T totals, C cytosolic fraction, M membranous fraction, and N nuclear fraction. Fractions were also analyzed for the related enzyme prolyl oligopeptidase: α POP. The following antibodies were used as markers: Lamin A/C for the nuclear fraction, tubulin for the cytosolic fraction and VDAC (voltage-dependent anion channel) for the membranous fraction. Shown are representative blots of at least three independent experiments. c–e DPP activity in the subcellular fractions. All Michaelis–Menten assays were performed at least three times in triplicates. Shown are graphs including error bars. c Hydrolysis of GP-AMC by 5 μg nuclear extracts in the presence or absence of the DPP8/9-specific inhibitor 1G244. d 5 μg of cytosolic extracts were analyzed as in c. e 5 μg of membranous extracts were tested as in c. f Table summarizing the activity of recombinant DPP9-l incubated in the different fractionation buffers: hypotonic buffer (cytosolic fraction), membrane buffer (membranous fraction) and total buffer (nuclear fraction). The table summarizes the effect of the buffers on DPP9 activity (K m and K cat) and inhibition (K i) by 1G244. All assays were performed in triplicates and were repeated at least three times

For control, we further tested these cellular fractions for other members of the DPPIV family: DPP8 and DPPIV, as well as for a related cytosolic enzyme: prolyl oligopeptidase (POP) [41]. In agreement with previous publications, we detect POP in the cytosolic fraction (Fig. 6b). As expected, DPPIV was found in the fraction corresponding to membranous proteins, together with the membrane marker VDAC (Fig. 6b). Unexpectedly, however, we find that DPP8 is not exclusively localized to the cytosol but rather that a considerable proportion of this peptidase is detected in the nuclear fraction (Fig. 6b and full scans in supplementary Fig. S4B, C). This observation is supported by immunofluorescence images of untransfected HeLa cells (Fig. 6a).

The finding that overexpressed DPP9-l is active in the nucleus does not necessarily mean that the endogenous DPP9-l behaves in a similar manner. An alternative possibility is that nuclear localization of DPP9-l sequesters the enzyme to inhibitory complexes within the nucleus, which are overloaded in the case of overexpression studies. Therefore we investigated whether we can detect DPP activity in the nuclear fractions of untransfected HeLa cells. In line with our previous observations, we measured prolyl peptidase activity not only in cytosolic fractions but also in fractions containing membranous proteins, and importantly, also in nuclear fractions (Fig. 6c–e). To test whether GP-AMC hydrolysis in the nuclear fractions can indeed be attributed to DPP9, we performed cleavage-activity assays in the presence of the DPP8/9-specific inhibitor 1G244 and compared the activity to mock-treated samples (Fig. 6c) [36]. A DPP8/9 inhibitor was used in this assay since there are no available inhibitors that differentiate between DPP8 and DPP9 due to their high homology. Importantly, the addition of 1G244 to nuclear extracts leads to a reduced hydrolysis of GP-AMC in this compartment (Fig. 6c), suggesting that DPP9 and possibly also DPP8 are active in the nucleus. Of note, the nuclear extracts were prepared in a buffer that contains high detergent concentrations (1 % IGEPAL, 0.5 % Na-deoxycholate and 0.1 % SDS). These detergents affect the folding of DPP9 and most importantly, reduce the activity of DPP9 by affecting both the K m and K cat values (Fig. 6f and supplementary Fig. S4D&E). Consequently, the measured activity in the nuclear fraction may be underestimated compared to the activity measured in the cytosolic and membrane fractions. Furthermore, the K i of 1G244 is increased more than 15 times compared to its value in the buffer for cytosol preparation (Fig. 6f), which may be the reason for the lower inhibition of DPP activity in the nuclear extracts compared to the cytosolic fractions (Fig. 6c, d). Taken together, these results show for the first time that in addition to their cytosolic localization ([19] [18]), DPP8 and DPP9 are also localized to a great extent in the nucleus and are active in this compartment.

Discussion

The DPP9 pre-mRNA contains two translation initiation sites, which potentially could generate two DPP9 variants differing in their amino terminus: a long (892 aa) and a short (863 aa) DPP9 isoform. Up to date only the expression of the short DPP9 protein was verified in cells, and it was unclear whether the longer form is biologically relevant.

Using antibodies that specifically recognize the N-terminal extension present only in the longer form, we show the endogenous expression of DPP9-l on protein level. Biochemical examination reveals that similar to other members of the DPP family [6–11, 42], DPP9-l also forms dimers and is active, with comparable cleavage characteristics to the shorter DPP9 variant. Taken together, these results show for the first time that the endogenous pool of DPP9 protein in cells is composed of at least two different versions: DPP9-S and DPP9-l, which share similar biochemical properties.

Surprisingly, immunofluorescence microscopy images of DPP9-overexpressing cells reveal that the two versions of DPP9 are differentially distributed within the cell. Whereas DPP9-S is cytosolic, DPP9-l is localized to the nucleus. We further studied endogenous DPP9 biochemically by cell fractionation assays, which were then analyzed with two different antibodies, one specific for DPP9-l and a second antibody, which binds to the catalytic domain thus recognizing both forms. Using this strategy, we verify that endogenous DPP9 is found not only in the cytosol but also in membranous and nuclear fractions. Using the specific antibodies against DPP9-l, we show that it does not represent the major DPP9 form in the cytosol or membrane fractions, but is highly enriched in the nuclear fraction. Moreover, our data also demonstrate that nuclear DPP9 represents a considerable proportion of the endogenous DPP9 pool in cells.

The differential localization of DPP9-l and DPP9-S is accomplished by a classical monopartite NLS (K(K/R)X(K/R)) in the N-terminal extension of DPP9-l. Localization studies with various mutants revealed three basic residues at positions 5, 6, and 8 (K5K6R8) as essential for nuclear localization of DPP9-l. Furthermore, this NLS is sufficient to target non-nuclear DPP9-S to the nucleus, where it can execute its enzymatic activity. Experiments with the CRM-1 inhibitor leptomycin B show that DPP9-S does not accumulate in the nucleus, arguing against a second unknown internal NLS in DPP9 or a stronger NES in DPP9-S. In conclusion, here we show that the N-terminal extension of DPP9-l does not affect the activity of this variant, but instead its cellular localization, since it contains an NLS that targets the long form to the nucleus.

How are the two different DPP9 forms generated within the cell? One possibility is that the two forms are produced from one single transcript, with two alternative translation initiation sites, in a process termed leaky scanning. The use of alternative start codons to generate various protein variants is a conserved feature in eukaryotes [43]. Examples for leaky scanning were reported for several proteins including human-insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) [44] and human neuropeptide Y [45]. Importantly, leaky scanning occurs if the upstream ATG is arranged within a poor match for a Kozak consensus, allowing the translation to initiate also from a second down-stream start codon (for review see [46]). However, the first AUG codon encoding for DPP9-l is arranged within a strong context, meaning a purine (G/A) at position −3 and a G at position +4, arguing against this possibility. Moreover, if indeed the two variants DPP9-S and DPP9-l would be produced from leaky scanning, than cells over-expressing the DPP9-l construct should express both the short and the long form of DPP9. If this were the case, then the two forms should be detected with the antibody against the catalytic domain (DPP9-total). However, we found that cells overexpressing DPP9-l do not show equal nuclear and cytosolic staining in immunofluorescences using the DPP9 total antibody. On the contrary, cells overexpressing DPP9-l showed a strong nuclear localization in immunofluorescence studies with the total-DPP9 antibody, similar to the pattern seen with the HA antibody detecting DPP9-l only. In addition, the cellular localization of the DPP9-l M30A construct, which is mutated in the second translation initiation codon, is similar to that of cells expressing DPP9-l. Taken together, these results suggest that DPP9-S and DPP9-l are probably not generated by leaky scanning.

Interestingly, cell fractionation assays and immunofluorescence data suggest that DPP8 is also located to the nucleus. However, in contrast to DPP9, analysis of the DPP8 sequence with the cNLS mapper program does not predict an NLS at the amino terminus of the protein but instead a putative bipartite NLS in all DPP8 isoforms (data not shown). Previously, DPPIV was also reported to localize to the nucleus in human cancer cells such as cultured malignant T cell lines [47, 48]. This translocation however is different from that observed for DPP9, and presumably does not involve an NLS, but instead caveolin-dependent endocytosis of DPPIV and a yet not further analyzed mechanism into the nucleus. Whether DPP8 is imported into the nucleus via the predicted bipartite NLS present in DPP8 or whether it is imported by a different mechanism similar to DPPIV remains to be shown.

Importantly, in line with the microscopy images and biochemical data, we detect DPP enzymatic activity in the nuclear fraction. This activity can be partially inhibited with a specific DPP8/9 inhibitor 1G244, verifying that these enzymes are indeed active within the nucleus. The finding that some DPP activity remains in the nucleus in the presence of 1G244 may be explained by the fact that the inhibitor is less efficient under the buffer conditions of the nuclear extracts, as measured by an increase in K i. The reduced efficiency of the inhibitor probably leads to an underestimation of the DPP8&9 prolyl peptidase activity in the nucleus. Moreover, in contrast to malignant T cell lines [47, 48], Western-blot analysis of HeLa nuclear fractions suggests that DPPIV does not contribute to the major DPP activity in this fraction. Thus, although we cannot exclude that other unknown enzymes may contribute to prolyl peptidase activity in the nucleus, our results show for the first time the nuclear localization and activity of DPP9 (and DPP8) in this compartment.

A fascinating question that rises from this work concerns the biological functions of DPP9 and DPP8 in the nucleus. So far, no nuclear candidate substrates for these peptidases are known. The only endogenous DPP9 substrate known so far is the RU134–41 antigen, which is stabilized in the cytosol upon DPP9 silencing, linking DPP9 to the MHC class I pathway [28]. Recently, a large degradome screen from cells overexpressing DPP9 or DPP8 was performed, leading to the identification of several cytosolic candidate substrates [27]. Peptides corresponding to these substrates were further shown to be cleaved in vitro by recombinant DPP8 and DPP9 [27]. However, the screen was performed on cytosolic extracts with cells overexpressing DPP9-S, therefore these candidates do not appear to be relevant for nuclear DPP8 and DPP9. An intriguing hypothesis is that DPP8 and DPP9 regulate the activity or stability of nuclear proteins, such as transcription factors. Future work will address this question by screening for endogenous DPP9 and DPP8 substrates as well as interacting partners in the nucleus.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Daniela Justa-Schuch is partially funded by a grant from the Niedersächsisch-israelische Gemeinschaftsvorhaben VWZN2626 and a fellowship from the Goettingen Center for Molecular Biosciences. Ruth Geiss-Friedlander is supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft 2234/1-1. We are thankful to Sven Dennerlein for providing us purified mitochondria as a source for the VDAC-positive control. We are very grateful to Ralph Kehlenbach for stimulating discussions; we also thank Ralph Kehlenbach and Esther Pilla for critical reading of the manuscript. R.G-F thanks Blanche Schwappach and Ivo Feussner for their generous support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

- AMC

7-Amino-4-methylcoumarin

- NLS

Nuclear localization signal

- DPP

Dipeptidyl peptidase

- MHC

Major histocompatibility complex

- SUMO

Small ubiquitin-like modifier

- HA

Human influenza hemagglutinin

- RanBP2

Ran-binding protein 2

References

- 1.Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Bateman A. MEROPS: the database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D343–D350. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vanhoof G, Goossens F, De Meester I, et al. Proline motifs in peptides and their biological processing. FASEB J. 1995;9:736–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenblum JS, Kozarich JW. Prolyl peptidases: a serine protease subfamily with high potential for drug discovery. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:496–504. doi: 10.1016/S1367-5931(03)00084-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu DM, Yao TW, Chowdhury S, et al. The dipeptidyl peptidase IV family in cancer and cell biology. FEBS J. 2010;277:1126–1144. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang H, Chen Y, Keane FM, Gorrell MD. Advances in understanding the expression and function of dipeptidyl peptidase 8 and 9. Mol Cancer Res. 2013;11:1487–1496. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engel M, Hoffmann T, Wagner L, et al. The crystal structure of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD26) reveals its functional regulation and enzymatic mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5063–5068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0230620100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rasmussen HB, Branner S, Wiberg FC, Wagtmann N. Crystal structure of human dipeptidyl peptidase IV/CD26 in complex with a substrate analog. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;10:19–25. doi: 10.1038/nsb882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bjelke JR, Christensen J, Nielsen PF, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidases 8 and 9: specificity and molecular characterization compared with dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Biochem J. 2006;396:391–399. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aertgeerts K. Structural and kinetic analysis of the substrate specificity of human fibroblast activation protein. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19441–19444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500092200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee HJ, Chen YS, Chou CY, et al. Investigation of the dimer interface and substrate specificity of prolyl dipeptidase DPP8. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38653–38662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603895200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang HK, Tang HY, Hsu SC, et al. Biochemical properties and expression profile of human prolyl dipeptidase DPP9. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;485:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park JE, Lenter MC, Zimmermann RN, et al. Fibroblast activation protein, a dual specificity serine protease expressed in reactive human tumor stromal fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36505–36512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chien CH, Huang LH, Chou CY, et al. One site mutation disrupts dimer formation in human DPP-IV proteins. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52338–52345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406185200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung KM, Cheng JH, Suen CS, et al. The dimeric transmembrane domain of prolyl dipeptidase DPP-IV contributes to its quaternary structure and enzymatic activities. Protein Sci. 2010;19:1627–1638. doi: 10.1002/pro.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chien CH, Tsai CH, Lin CH, et al. Identification of hydrophobic residues critical for DPP-IV dimerization. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7006–7012. doi: 10.1021/bi060401c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitman MR, Menz RI, Abbott CA. Hydrophilic residues surrounding the S1 and S2 pockets contribute to dimerisation and catalysis in human dipeptidyl peptidase 8 (DP8) Biol Chem. 2010;391:959–972. doi: 10.1515/BC.2010.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drucker DJ. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibition and the treatment of type 2 diabetes preclinical biology and mechanisms of action. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1335–1343. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abbott CA, Yu DM, Woollatt E, et al. Cloning, expression and chromosomal localization of a novel human dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP) IV homolog, DPP8. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:6140–6150. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ajami K, Abbott CA, McCaughan GW, Gorrell MD. Dipeptidyl peptidase 9 has two forms, a broad tissue distribution, cytoplasmic localization and DPIV-like peptidase activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1679:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olsen C, Wagtmann N. Identification and characterization of human DPP9, a novel homologue of dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Gene. 2002;299:185–193. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)01059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qi SY, Riviere PJ, Trojnar J, et al. Cloning and characterization of dipeptidyl peptidase 10, a new member of an emerging subgroup of serine proteases. Biochem J. 2003;373:179–189. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu DM, Ajami K, Gall MG, et al. The in vivo expression of dipeptidyl peptidases 8 and 9. J Histochem Cytochem. 2009;57:1025–1040. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2009.953760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu C, Tilan JU, Everhart LM, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidases as survival factors in Ewing sarcoma family of tumors: implications for tumor biology and therapy. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:27494–27505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.224089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matheeussen V, Waumans Y, Martinet W, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidases in atherosclerosis: expression and role in macrophage differentiation, activation and apoptosis. Basic Res Cardiol. 2013;108:1236–1244. doi: 10.1007/s00395-013-0350-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu DM, Wang XM, McCaughan GW, Gorrell MD. Extraenzymatic functions of the dipeptidyl peptidase IV-related proteins DP8 and DP9 in cell adhesion, migration and apoptosis. FEBS J. 2006;273:2447–2460. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gall MG, Chen Y, de Ribeiro AJ, et al. Targeted inactivation of dipeptidyl peptidase 9 enzymatic activity causes mouse neonate lethality. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e78378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson CH, Indarto D, Doucet A, et al. Identifying natural substrates for dipeptidyl peptidase 8 (DP8) and DP9 using terminal amine isotopic labelling of substrates, TAILS, reveals in vivo roles in cellular homeostasis and energy metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:13936–13949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.445841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geiss-Friedlander R, Parmentier N, Möller U, et al. The cytoplasmic peptidase DPP9 is rate-limiting for degradation of proline-containing peptides. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:27211–27219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.041871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vigneron N, Van den Eynde BJ. Insights into the processing of MHC class I ligands gained from the study of human tumor epitopes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:1503–1520. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0658-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Endert P. Post-proteasomal and proteasome-independent generation of MHC class I ligands. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:1553–1567. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0662-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pilla E, Möller U, Sauer G, et al. A novel SUMO1-specific interacting motif in dipeptidyl peptidase 9 (DPP9) that is important for enzymatic regulation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:44320–44329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.397224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schade J, Stephan M, Schmiedl A, et al. Regulation of expression and function of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DP4), DP8/9, and DP10 in allergic responses of the lung in rats. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56:147–155. doi: 10.1369/jhc.7A7319.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sulda ML, Abbott CA, Macardle PJ, et al. Expression and prognostic assessment of dipeptidyl peptidase IV and related enzymes in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10:180–189. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.2.12168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dubois V, Lambeir AM, Vandamme S, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 9 (DPP9) from bovine testes: identification and characterization as the short form by mass spectrometry. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:781–788. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Charneau P, Mirambeau G, Roux P, et al. HIV-1 reverse transcription. A termination step at the center of the genome. J Mol Biol. 1994;241:651–662. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu JJ, Tang HK, Yeh TK, et al. Biochemistry, pharmacokinetics, and toxicology of a potent and selective DPP8/9 inhibitor. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waldmann I, Spillner C, Kehlenbach RH. The nucleoporin-like protein NLP1 (hCG1) promotes CRM1-dependent nuclear protein export. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:144–154. doi: 10.1242/jcs.090316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holden P, Horton WA. Crude subcellular fractionation of cultured mammalian cell lines. BMC Res Notes. 2008;2:243. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pejanovic N, Hochrainer K, Liu T, et al. Regulation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) transcriptional activity via p65 acetylation by the chaperonin containing TCP1 (CCT) PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kosugi S, Hasebe M, Tomita M, Yanagawa H. Systematic identification of cell cycle-dependent yeast nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins by prediction of composite motifs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:10171–10176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900604106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brandt I, Scharpé S, Lambeir AM. Suggested functions for prolyl oligopeptidase: a puzzling paradox. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;377:50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen YS, Chien CH, Goparaju CM, et al. Purification and characterization of human prolyl dipeptidase DPP8 in Sf9 insect cells. Protein Expr Purif. 2004;35:142–146. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2003.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bazykin GA, Kochetov AV. Alternative translation start sites are conserved in eukaryotic genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:567–577. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leissring MA, Farris W, Wu X, et al. Alternative translation initiation generates a novel isoform of insulin-degrading enzyme targeted to mitochondria. Biochem J. 2004;383:439–446. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaipio K, Kallio J, Pesonen U. Mitochondrial targeting signal in human neuropeptide Y gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;337:633–640. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kozak M. Pushing the limits of the scanning mechanism for initiation of translation. Gene. 2002;299:1–34. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)01056-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamada K, Hayashi M, Madokoro H, et al. Nuclear Localization of CD26 Induced by a Humanized Monoclonal Antibody Inhibits Tumor Cell Growth by Modulating of POLR2A Transcription. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e62304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamada K, Hayashi M, Du W, et al. Localization of CD26/DPPIV in nucleus and its nuclear translocation enhanced by anti-CD26 monoclonal antibody with anti-tumor effect. Cancer Cell Int. 2009;9:17. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-9-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.