Abstract

Microglial cells contribute to normal function of the central nervous system (CNS). Besides playing a role in the innate immunity, they are also involved in neuronal plasticity and homeostasis of the CNS. While microglial cells get activated and undergo phenotypic changes in different disease contexts, they are far from being the “villains” in the CNS. Mounting evidence indicates that microglial dysfunction can exacerbate the pathogenesis of several diseases in the CNS. Several molecular mechanisms tightly regulate the production of inflammatory and toxic factors released by microglia. These mechanisms involve the interaction with other glial cells and neurons and the fine regulation of signaling and transcription activation pathways. The purpose of this review is to discuss microglia activation and to highlight the molecular pathways that can counteract the detrimental role of microglia in several neurologic diseases. Recent work presented in this review support that the understanding of microglial responses can pave the way to design new therapies for inflammatory diseases of the CNS.

Keywords: Central nervous system, Therapies, Neurologic diseases

Introduction

Microglial cells are known as the resident macrophages of the central nervous system (CNS). Contrary to the other glial cells, they share the same cell lineage with other tissue macrophages such as liver Kupffer cells and lung alveolar macrophages [1]. Besides microglia, the population of CNS macrophages comprises also the perivascular, meningeal and choroid plexus macrophages [2]. All of these cells are pivotal players in inflammation, a complex physiological response aimed at restoring homeostasis upon injury by infectious or toxic agents.

The use of two-photon microscopy enabled the observation of microglial cells in their natural environment in vivo and started a new era of functional studies both in physiological and pathological conditions [3–6]. Live cell imaging reveals highly motile microglial processes that seem to continuously monitor their local microenvironment [4, 7]. This observation definitely changed the previous notion of a “resting” microglial phenotype in normal adult CNS. The last 5 years have become a golden age for the study of microglial cells: the discovery of progenitors in the yolk sac (YS) elucidated their origin [8], in vivo evidences of direct contacts between microglia processes and synaptic terminals supported their role in brain homeostasis and neuronal plasticity [9, 10] and finally genetic manipulation allowed microglia-specific gene deletion without affecting other bone marrow-derived cells in adult mice [11]. The research of molecular mechanisms and specific factors that determine how microglia affect neuronal development, plasticity, damage and repair has now been launched.

Although microglial reactivity to external stimuli may be reparative, if uncontrolled leads to an exacerbated release of pro-inflammatory and toxic factors. This uncontrolled response in the presence of other damaging cues results in detrimental effects on the CNS. In fact, there is compelling evidence for a role of microglial inflammatory response in the pathophysiology of several diseases including CNS infections, ischemic stroke [12], multiple sclerosis (MS), neurodegenerative diseases, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases (AD/PD/HD) (reviewed in [13] ), and psychiatric disorders (reviewed in [14]). The focus on pathological conditions partially contributed to some “conspiracy” against microglia for several years. However, different types of microglial activation with both beneficial and deleterious outcomes for neurons fed the controversy around the role of microglia activation in CNS diseases. There is now a general consensus that uncontrolled inflammation, in which microglial responses have a damaging impact, has to be hampered in the brain. Along the years, several factors that inhibit microglial pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic responses have been identified. Mechanisms that result from interactions of microglia with other cells such as neurons and astrocytes and the detailed regulation of microglial signaling and transcription processes are being elucidated. Can this knowledge be translated to new therapeutic strategies that control microglial-mediated inflammation, preventing deleterious effects? In this review we focus on molecular mechanisms and pathways that regulate microglial inflammatory and neurotoxic response. Importantly, we further discuss therapies for inflammatory diseases of the CNS based on these mechanisms.

Origin and differentiation of microglia

For a long time, the origin and differentiation of microglial cells was a topic of debate and controversy. Recently, microglial progenitors were identified in the YS by studies that tracked myeloid cells throughout embryonic development [1, 8, 15].

In adult mice, hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) residing in the bone marrow give rise to the myeloid lineage, including blood monocytes. Upon migration to organs and tissues, blood monocytes become macrophages [16]. Irradiation chimerism experiments supported the hypothesis that microglial cells could derive from hematopoietic stem cells within the bone marrow or in blood circulation [17, 18]. However, it was demonstrated that disruption of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) or irradiation of the brain are required for bone marrow-derived cells or a subset of monocytes to infiltrate the brain and differentiate into brain macrophages [17, 19, 20].

The presence of microglial precursors in the YS before definitive hematopoiesis indicates that microglia exist independently of hematopoietic stem cells. Instead, they derive from primitive myeloid progenitors [8]. Recent investigations found microglial cells in the embryo between 8.5 and 9.5 days post-conception (dpc) after the activation of Runt-related transcription factor-1 (Runx-1), a transcription factor that regulates myeloid cell differentiation and proliferation [8]. In another study, the authors identified a pre-macrophagic and erythromyeloid progenitor that gives rise to microglial cells [15]. Additionally, microglial differentiation does not require Myb, a critical transcription factor that controls hematopoietic cell lineage differentiation [1]. Contrary to monocytes, microglial cells are absent in mice lacking Pu.1 transcription factor [15] or the macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor (CSF1R) [8, 21].

Interestingly, we and others found that an hematopoietic cell marker, CD34 [22], Sca-1 [23], and Runx1 [24] are up-regulated in activated adult microglia. Whether this is a sign of microglial plasticity or it is important for microglial activation remains to be addressed.

Microglial activation phenotypes

Microglia cells react to homeostatic changes in the CNS or to damage signals upon brain injury. Activation of the microglia displays a range of responses that include morphological alterations, migration to the site of injury and proliferation (microgliosis), and increased expression of several factors, including immune mediators. Moreover, microglial cells may transform into highly phagocytic cells removing dead cells, accumulated debris, protein aggregates, bacterial and viral pathogens [25]. The recruitment of blood monocytes in response to brain injury further influences the activation of resident macrophages and the inflammatory response in the CNS. It is impossible to establish a unique pattern of microglial response, which may be specific for the type of injury. Although changes in morphological features of microglia or increase in microglia cell number are observed in several pathological conditions, microglial function or phenotype cannot be inferred based solely on these traits. Finally, microglial function is highly dependent on the balance between neuroprotective and neurotoxic factors that they produce in response to injury.

A variety of signals were shown to induce a response by microglia (reviewed in [25]) including factors released by neurons (e.g., ATP and neurotransmitters), leakage products from necrotic cells (e.g., RNA and DNA), plasma constituents (thrombin and fibrinogen) and abnormally folded proteins (i.e., amyloid-β (Aβ) and α-synuclein [26]). The whole panoply of membrane and intracellular receptors activated by these signals determine the final functional characteristics of microglia. Importantly, microglial activation is not a simple on/off mechanism; microglia and brain macrophages have a remarkable plasticity and may acquire different phenotypes. These phenotypes may play a beneficial or destructive role in original damage resolution depending on the stimuli and the environment they encounter. Moreover, they can be reversible and influenced by systemic inflammation caused by infection (reviewed in [27]). Noteworthy, in the same tissue different populations of microglia under different activation phenotypes can be found. The classical pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic phenotype, known as M1, and the alternate anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype involved in the resolution of the inflammation, phagocytosis and tissue repair are the two extremes of a broad scale of macrophagic responses (reviewed in [28]). These two polarized activation states (M1 and M2), initially defined for peripheral macrophages treated with different agents in vitro, are also identified in microglia. Exposure of microglial cell cultures to stimuli such as bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) [29, 30], TNF-α [31], IFNγ [32], necrotic neurons [33], oligomers of Aβ [34] and α-synuclein [26, 35] induces the M1 phenotype. M1 is phenotypically characterized by activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (ERK1/2 and p38) [30], expression of major histocompatibility complex type II cell surface glycoprotein (MHCII), secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-12) and production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). In addition, up-regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS or NOS2), glutaminase and inducible cyclooxygenase (COX-2) leads to an increase of nitric oxide (NO), glutamate and prostaglandins, respectively. Most of these factors released by microglia are neurotoxic for neuronal cell cultures. It is a matter of ongoing debate whether an M1 type of microglial activation in vivo is the cause of neurodegeneration or a consequence of neuronal cell damage, which can activate microglia, further increasing neurotoxicity. In this case, a self-perpetuating cycle of microglial activation and neurodegeneration may contribute to several diseases of the CNS (reviewed in [36]). However, neurodegeneration triggered by microglial inflammatory response is best demonstrated by the paradigm of microglia activation by the bacterial endotoxin LPS. Infusion of LPS into substantia nigra in rodents induces microglial classical activation through toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 followed by death of dopaminergic neurons, which is used as a model of PD [37].

On the other hand, the alternative M2 phenotype is neuroprotective and can be induced in primary microglial cells by the cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 (secreted in vivo by Th2 lymphocytes) [38]. It is characterized by the expression of heparin-binding lectin (Ym1), cysteine-rich protein FIZZ-1 and Arginase 1 by microglia [38]. In vitro, IL-4 was found to decrease iNOS activity, superoxide and TNF-α production in LPS- and TNF-α-activated microglia along with the rescue of neurons from neurotoxicity [39, 40]. IL-4 also increases the phagocytic activity of microglia, namely the uptake of oligomeric Aβ species through the scavenger receptor CD36 [41]. Also in cell cultures, IL-13 and IL-10 (an anti-inflammatory cytokine produced by macrophages) increase microglial secretion of activin-A, a neuroprotective TGFβ superfamily member that also promotes oligodendrocyte differentiation [42]. In mice, under physiological conditions, microglia express higher levels of Ym1 and anti-inflammatory cytokine (IL-4 and TGFβ), compared to other macrophages. This observation indicates that brain microenvironment, namely microglial–neuronal cross talk, skews microglial phenotype toward M2 [43].

In spite of the frequent association of neurodegenerative diseases with a classical and chronic activation of microglia, it is more likely that there is a continuum or a hybrid M1 and M2 mixed phenotype as shown in brain samples from AD patients and transgenic mouse models of this disease [44]. Similarly, in MS, a demyelinating disease that also induces chronic inflammation in the CNS, both M1 and M2 markers are expressed by macrophages present in MS lesions [43, 45]. Microglia may also undergo a transition from M1 to M2 phenotype along the course of the disease. This is the case in the remyelination process that follows a demyelinating insult in the mouse corpus callosum induced by lysolecithin [42].

Mechanisms and pathways that control microglial-mediated inflammation

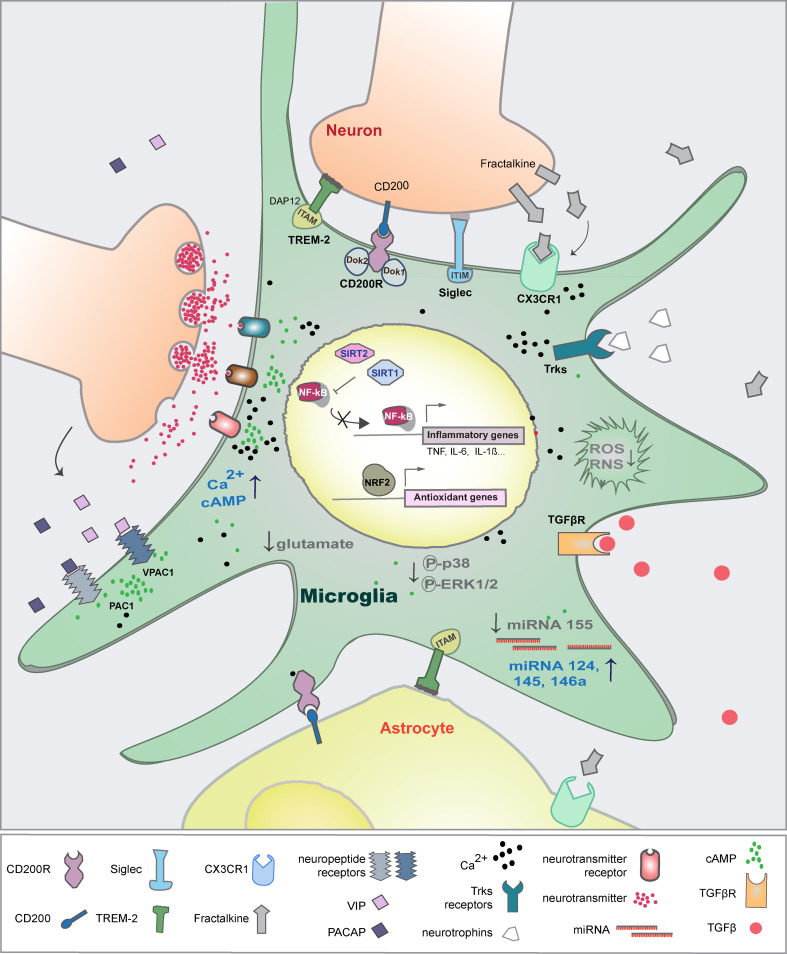

Microglia and other CNS macrophages express a variety of receptors that detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released during tissue injury. Among these receptors, the TLRs and the Nod-like receptors (NLRs) activate MAPK signaling pathways, NF-κB-dependent transcription and caspase-1 that induce inflammatory mediators (reviewed in [46]). However, microenvironmental factors, either involving direct interaction of microglia with neuronal cells and astrocytes or with soluble factors, activate receptors that trigger signaling pathways counteracting the inflammatory and neurotoxic microglial responses. The course of microglia activation can be changed effectively by the direct regulation of gene transcription by NF-κB and NRF2 transcription factors or post-transcriptionally by miRNAs and the histone acetylation machinery (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Physiological mechanisms that control microglial-mediated inflammation. Microglial cells communicate with neurons and astrocytes through direct cell-to-cell interaction and through soluble factors. These external factors inhibit the production of neurotoxic factors and the transcription of inflammatory genes. In parallel, internal mechanisms also regulate signaling and gene transcription that restrain overactivation of microglia

Ultimately, the microglial response results from the activation of various signaling pathways that regulate expression of both pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators.

In this review, we focus on the mechanisms that were shown to inhibit the pro-inflammatory M1 properties of microglia and its neurotoxicity.

TREM-2

Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells (TREM) proteins belong to the immunoglobulin ‘superfamily’. They have no intrinsic signaling motif and require the DNAX-activating protein 12 kDa (DAP12) adaptor for intracellular signaling. TREM proteins have different functions. While TREM-1 is an amplifier of the inflammatory response, TREM-2 inhibits inflammatory responses induced by TLR ligands in macrophages [47].

TREM-2 is exclusively expressed by microglia in the brain, although the levels differ within the whole population [48, 49]. Its expression decreases in microglia upon stimulation with LPS and IFNγ [48]. TREM-2 binds to bacteria and astrocytes [50] and so far Hsp60 is its only ligand identified at the surface of astrocytes and neuroblastoma cells [51]. Triggering of TREM-2 in primary murine microglia induces ERK1/2 phosphorylation, cytoskeleton rearrangements and increased phagocytosis [49]. Moreover, overexpression of TREM-2 promotes phagocytosis of apoptotic neurons by microglia in a DAP12-dependent manner. Similarly, exposure of a microglial cell line to Hsp60 stimulates bacterial phagocytosis through TREM-2 [51]. In contrast, knock-down of TREM-2 impairs clearance of apoptotic neurons and increases the expression of TNF-α and iNOS [49]. This impairment of microglial function may explain the inflammatory response and axonal loss observed in patients with sclerosing leukoencephalopathy (PLOSL)/Nasu–Hakola disease, whose TREM-2 and DAP12 genes present loss-of-function mutations [52, 53]. Recent epidemiologic studies also found that a missense mutation in TREM-2 gene is linked to increased susceptibility to late-onset AD (reviewed in [54]).

In MS and in experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE), an animal model of MS, TREM-2 activation is necessary for microglial phagocytic activity and recovery. The removal of myelin debris in lesions [55, 56] by microglia allows oligodendrocyte precursor recruitment and regenerative remyelination [57].

Siglecs

Siglecs (sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins), like TREM-2, are a subgroup of the Ig superfamily that also contain an amino-terminal Ig-like variable (V-set Ig-like) domain and different numbers of Ig-like constant region type 2 (C2-set Ig-like) domains (reviewed in [58, 59]). Siglecs recognize sialic acid bound to surface glycans, glycolipids or glycoproteins. CD33-related Siglecs are a subset that are mostly expressed by cells of the immune system. CD33-related Siglecs have one or more cytosolic immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs).

Siglec-11 is a CD33-related Siglec that binds to 2, 8-linked polysialic acids and is only found in primates [60]; a shorter splicing variant of Siglec-11 is expressed by microglia [61]. Triggering of Siglec-11 in murine microglia leads to a decrease in phagocytosis of apoptotic neurons and prevents induction of IL-1β and iNOS by LPS. In co-cultures of neurons and microglia, Siglec-11 expressed by microglia binds to polysialylated neuronal cell adhesion molecule (PSA-NCAM) and protects neurons toward microglial toxicity [61]. Similarly to Siglec-11, Siglec-E is expressed in murine microglia and inhibits phagocytosis of neuronal debris, the associated oxidative burst and the pro-inflammatory response [62]. The recognition of sialic acids on the neuronal glycocalyx seems to signal cellular integrity inhibiting microglia activation under physiological conditions.

Despite the neuroprotective function of siglecs, CD33 (Siglec-3) was recently linked to AD [63]. It was shown that its expression is increased in AD cases and contributes to AD pathology likely by preventing the uptake of Aβ by microglial cells.

CD200-receptor (CD200R)

CD200R is another membrane glycoprotein of the Ig superfamily that is highly expressed by myeloid cells. Unlike other inhibitory receptors, CD200R does not contain an ITIM and interacts with the adaptor kinases Dok1 and Dok2 [64].

In the CNS, microglial cells express CD200R, while its ligand, CD200, is expressed on the membrane of neurons and astrocytes [65]. CD200 expression is induced by IL-4 in primary cortical neurons [66] and in primary microglia CD200R expression is reduced upon activation with LPS [67]. Pre-treatment of microglia with CD200 fused to the IgG Fc region (CD200Fc), an agonist of CD200R, inhibits induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-α) by Aβ. This effect, which involves the phosphorylation of Dok2, is prevented by silencing Dok2 in microglia [68]. Moreover, the anti-inflammatory effect was mimicked when neurons were used as a source of CD200 [66].

CD200-deficient mice confirm the role of CD200R-CD200 in controlling microglial inflammatory response. In these animals microglia display several changes associated with a reactive phenotype, including aggregates of microglial cells with less ramified and shorter processes and increased CD11b and CD45 expression [69].

Interestingly, increased pro-inflammatory response by microglia in MS may also be due to a reduced CD200-CD200R signaling. Indeed, expression of both CD200 and CD200R is decreased in EAE animal models [70], while transgenic mice overexpressing neuronal CD200 show reduced activated and infiltrating monocytes concomitantly with decreased disease severity [71]. Koning et al. [72] observed increased CD200 expression in reactive astrocytes within chronic active plaque centers of CNS samples from MS patients. Therefore, during the remission phase, also astrocytes may be signaling to restore an immune-suppressive environment.

A decrease in the expression of CD200-CD200R signaling may be an additional mechanism for increased M1 activated microglia in AD. Patients suffering from AD show significantly lower expression of CD200, mainly in the hippocampus [73].

CX3C chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1)

CX3CR1 is a conventional Gi/o-coupled seven-transmembrane receptor that leads to the activation of phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-dependent signaling pathway and to an increase in calcium (Ca2+) influx. In the CNS, CX3CR1 is highly expressed by microglia but is also detected in astrocytes. The ligand, CX3CL1, also known as fractalkine, is expressed by a particular type of neuron [74]. The knock-in mice in which one CX3CR1 allele was replaced by GFP is a very useful tool to track microglia in vivo and study microglial function by two-photon microscopy [75]. The resultant decreased expression of CX3CR1 does not seem to change microglial phenotype or cell numbers [11]. Fractalkine is synthesized as a transmembrane protein without signaling motifs which can be cleaved by metalloproteinases ADAM17/TACE and released to the extracellular space [76]. While CX3CL1 is expressed constitutively by neurons, astrocytes express it if activated by pro-inflammatory cytokines [77]. Fractalkine induces an increase in intracellular levels of Ca2+, ERK1/2 phosphorylation and protein kinase B/AKT activation in microglia, while it inhibits TNF-α secretion by LPS-activated microglia [77]. Moreover, the neurotoxicity caused by microglia is enhanced by pre-blocking fractalkine in hippocampal neurons [78]. The neuroprotective effect of fractalkine in co-cultures of microglia and neurons was also associated with induction of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) in microglia, an enzyme shown before to decrease ROS [79].

Ransohoff and collaborators were the first to demonstrate that deletion of CX3CR1 leads to an increase of the microglial response to LPS in vivo. Microglia isolated from CX3CR1-deficient mice injected with LPS secrete higher levels of IL-1β and are neurotoxic [80]. Others showed that CX3CR1-deficient mice express increased levels of IL-1β even without any challenge, which is associated with cognitive impairment and decreased neurogenesis. This phenotype could be rescued by an antagonist of IL-1R [81].

It is still debated whether activation of endogenous CX3CR1 signaling in microglia is neuroprotective or neurotoxic in different neurologic diseases. In agreement with a protective role, CX3CR1 knockout mice have an earlier onset and more severe EAE symptoms with overexpression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in CNS tissues, accumulation of brain dendritic cells and more pronounced demyelination and neuronal damage [82]. On the other hand, the levels of both CX3CL1 and CX3CR1 are increased in dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord in EAE, and are also correlated with the neuropathic pain observed in MS patients [83].

The role of CX3CL1-CX3CR1 signaling is even more controversial in AD. Bilateral microinjection of Aβ1-40 fibrils into the hippocampal CA1 area of rats results in significant up-regulation of CX3CR1 mRNA and protein expression, which is related to synaptic dysfunction and cognitive impairment [84]. In agreement, a study using two-photon microscopy, revealed that deletion of CX3CR1 in 3xTgAD mice prevents neuronal loss and microglia migration [6]. In addition, suppression of CX3CR1 signaling by CX3CR1 small interfering RNA in rats injected with Ab1-40 fibrils blunts microglial activation and IL-1β expression, restores basal glutamatergic strength and long-term potentiation (LTP) together with improved cognitive function [84]. Conversely, in mice overexpressing human amyloid precursor protein (APP), ablation of CX3CR1 decreases Aβ deposition [85], but enhances tau pathology and worsens memory and cognitive functions [86].

CD45

CD45 is a receptor-like transmembrane glycoprotein with a tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) in its cytoplasmatic domain. There are several alternative splicing variants of CD45 with both inhibitory and activating effects in leukocyte cell signaling (reviewed in [87]). The regulation of CD45 phosphatase activity and its ligands is poorly characterized. CD45 is expressed at lower levels by microglia compared to other populations of brain macrophages or blood-derived inflammatory macrophages, making it a useful marker to distinguish these populations by flow cytometry [88]. However, CD45 can also be up-regulated in parenchymal microglia during CNS inflammation caused by viral infection and also in AD [89, 90].

CD45 inhibits microglial inflammatory and cytotoxic response induced by Aβ peptides [91]. Activated CD45-deficient microglial cells co-cultured with neurons produce higher levels of TNF-α and NO and consequently are more neurotoxic when co-cultured with neurons. TNF-α is also increased in a mouse model of AD deficient for CD45. Conversely, cross-linking of CD45 inhibits microglia activation both in Aβ and LPS-stimulated microglia [91]. This effect is linked to decreased phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and neurotoxicity. Cross-linking of a CD45 isoform (CD45RB) also enhances Aβ phagocytosis and inhibits activation of MAPK pathway, IL-6 and TNF-α production induced by LPS [92]. The siglec CD22 secreted by neuronal cells was identified as a potential ligand of CD45 that inhibits TNF-α secretion by microglia [93]. Though it is not known how CD45 modulates microglial activity, it is worth mentioning that DAP12, which is fundamental for microglial signaling, is hyperphosphorylated in CD45-null NK cells [94].

Neurotransmitters, neuropeptides and neurotrophins with an anti-inflammatory role

Neurotransmitters

Although neurotransmitters are packed in synaptic vesicles, in vivo studies using two-photon microscopy revealed a physical interaction between microglial processes and pre- and post synapses, which suggest that neurotransmitters may encounter and bind to receptors in microglia [9]. This further supports a role for neuronal factors in microglial activity, namely by regulation of the inflammatory response. Although there is a lack of in vivo evidence, studies in cell cultures suggest that several neurotransmitters can control inflammation and neurotoxicity by activated microglia.

Neurotransmitter receptors were originally found in neurons, but they are also expressed by microglia. Glutamate is an excitatory amino acid that binds to ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGLuRs) and metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluRs). Group III mGlu receptors (mGlu4a, mGlu6 and mGlu8) that interact with Gi/o-proteins are expressed by rat primary microglia [95]. Activation of Group III mGlu receptors are coupled to inhibition of adenylate cyclase with decreased production of cAMP in microglia. Agonists of Group III mGlu receptors block apoptosis induced either by LPS or Aβ peptides in microglia. Moreover, these agonists protect neurons against LPS-induced microglial toxicity. It is still unclear whether this effect is due to a decrease in neurotoxic molecules or an increase in neuroprotective factors produced by microglia [95].

GABA, a neurotransmitter that decreases neuronal excitability, is generated by neurons and astrocytes (GABAergic cells) and interacts with GABAA and GABAB receptors, which are present in human adult microglia (GABAceptive cells) [96].

Treatment of IFNγ/LPS-activated human adult microglia with GABA or GABAA and GABAB receptor agonists reduces IL-6 and TNF-α secretion and phosphorylation levels of p38 MAPK and NF-κB. These effects are associated with decreased neurotoxicity induced by conditioned medium from stimulated microglia [96]. Similar to what occurs in other types of cells, the GABAAR in microglia is likely to exert its function through increased influx of Cl− [97].

Loss of acetylcholine (Ach) and norepinephrine (NE) is associated with neurodegenerative diseases, including AD and PD [98, 99], and may contribute to an increase in the inflammatory response. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) are ligand-gated ion channels and heteropentamers constituting two α subunits and either of β, δ, γ subunits [99]. The α7nAChR is expressed by murine and rat microglia. Agonists of this receptor increase cytosolic levels of Ca2+ due to the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores [100]. Ach and nicotine inhibit TNF-α release induced by LPS and the levels of phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPKs in microglia [101]. In addition, these neurotransmitters increase PGE2 in microglia, which may act as an anti-inflammatory factor [102].

Rat microglia express mRNA encoding α1A, α2A, β1 and β2 adrenergic receptors (AR). Intracellular cAMP levels are increased by AR agonists including NE, which leads to diminished levels of the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6. NE increases cAMP levels in microglial cells mainly through β2 AR [103] concomitantly with a decrease in the levels of iNOS and IL1β in LPS-activated microglia [104].

Neuropeptides

Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and its related neuropeptide pituitary adenylyl cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) are up-regulated in neurons upon injury and have both neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory functions [105]. These two peptides bind to G-protein-linked seven-transmembrane domain receptors; murine microglia express the VIP receptor 1 (VPAC1) and the PACAP receptor (PAC1) [106]. VIP and PACAP decrease the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL1β and TNF-α by LPS-activated microglia [107]. VIP also restrains the Aβ-induced microglial neurotoxicity. These inhibitory effects were shown to involve increases in cAMP and protein kinase A (PKA), which results in inhibition of p38 MAPK, ERK1/2 pathways and of NF-κB translocation to the nucleus [108].

Neurotrophins

Neurotrophins can be produced by neurons or glia. Microglial cells express brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), Neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) and nerve growth factor (NGF) as well as its receptors, Trks tyrosine kinase receptors (A, B and C) and the p75 neurotrophin receptor [109, 110]. Binding of neurotrophins to their receptors induces sustained increase in intracellular Ca2+ in microglia. BDNF binds to the truncated TrkB receptor and triggers an increase in intracellular Ca2+ in microglia through the store-operated calcium entry (SOCE). This effect is independent of TrkB receptor tyrosine kinases activation, but requires phospholipase C (PLC) activity [111]. While BDNF binds to the truncated TrkB receptor, NGF and NT3 preferentially bind to TrkA and TrkC receptors. Neurotrophins were shown to suppress both constitutive and LPS-induced NO production by rat microglia [112]. Pre-treatment of a microglial cell line with NT-3 inhibits both NO and TNF-α production [113]. Similarly, pretreatment of microglia with BDNF also significantly suppressed the release of NO from activated microglia [111].

TGF-β

There are three different TGF-β isoforms (TGF-β1, -β2 and -β3) that can bind to heteromeric serine/threonine receptors composed of two type I (TGF-βR1) and two type II (TGF-βR2) subunits [114]. TGF-β1 is highly expressed in the normal adult brain. Primary microglial cells express the different TGF-β isoforms, but TGF-β1 is expressed at higher levels. As they also express TGF-β receptors, an autocrine response to TGF-β by microglia is possible [115]. Inhibition of TGF-β signaling leads to an increase in IL-6 secretion and iNOS activity and to a decrease in Arginase 1 and Ym1, markers of alternative M2 activation. The anti-inflammatory function of TGF-β1 was further demonstrated in in vitro models. Studies in mesencephalic neuron–glia mixed cultures show that TGF-β1 protects dopaminergic neurons against LPS-induced toxicity through inhibition of TNF-α and ROS production by microglia. TGF-β1 suppresses ERK1/2 activation pathway which prevents phosphorylation of NADPH oxidase subunit p47phox and its translocation to the membrane to produce ROS [116].

TGF-β1 induces CX3CR1 expression in microglia likely due to enhanced transcription of the CX3CR1 gene. However, the physiological relevance of this finding remains unclear [117].

In agreement with the in vitro results, mice lacking TGF-β1 show altered microglial morphology such as loss of arborization and shorter processes, increased proliferation and expression of the membrane proteins MHC class I and complement receptor 3 (CR3). However, from these results it is difficult to conclude whether microglia activation is due to lack of TGF-β or a consequence of the axonal dystrophy and demyelination observed in these mice [118, 119].

Transcriptional regulation of microglia activation

Transcriptional regulation of pro-inflammatory genes involves the cross talk between several signal transduction pathways (MAPKs and STATs), transcription factors—AP-1, NF-κB, Pu.1, interferon regulatory factors (IRFs), cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB)—and histones’ modifications (reviewed in [120, 121]). Moreover the transcription factor NERF2, which controls the redox state of microglial cells, also regulates NF-kB-dependent transcription. Recently, the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression by microRNAs and desacetylases has shown further levels of regulation of specific pathways of microglial activation.

The nuclear factor NF-κB pathway

NF-κB activation triggered by TLRs or aging in microglia plays a fundamental role in inflammation of the CNS [122, 123]. The NF-κB protein family members, i.e., RelA/p65, RelB, c-Rel, p50 (NF-κB1) and p52 (NF-κB2), bind to DNA κB sites in promoters and enhancers of target genes either as homodimers or as heterodimers (reviewed in [124]). p65, c-Rel and RelB possess C-terminal transactivation domains (TADs) that enable transcription initiation are probably the most well-studied members. In a non-activated stated, NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm through binding to IκB proteins. External stimuli, such as TLRs ligands, activate the canonical NF-κB activation pathway. Once it is activated, the IκB kinase complex (IKK) phosphorylates the IκB proteins, leading to its ubiquitination and degradation through the proteasome [46]. Released NF-κB dimers can then translocate into the nucleus, bind specific DNA sequences and promote transcription of target genes. Termination of the transcriptional response requires resynthesis of IκB proteins and removal of active NF-κB dimers from the DNA. NF-κB activity depends on several steps: IKK complex activity, NF-κB inhibition by IκB proteins and binding of NF-κB proteins to the promoters of target genes. Post-translational modifications (PTMs) targeting NF-κB subunits, including acetylation and phosphorylation, also regulate transcription of a wide variety of target genes [124].

Inhibition of NF-κB-dependent gene transcription is normally associated with anti-inflammatory mechanisms in microglia. Deletion of IKKβ in the myeloid lineage, including brain macrophages, reduces microglial activation and neuronal loss in models of excitotoxicity and ischemic brain injury [125]. Yet, it was only very recently that NF-κB was specifically targeted in microglial cells by using Cre recombinase driven by the CSF1R promoter. By increasing the expression of IKKβ subunit in microglial cells, an M1 type of microglia activation was induced in the spinal cord accompanied by motor neuron cell death, similarly to the pathology of ALS. Accordingly, heterozygous deletion of IKKβ in microglia in a transgenic mouse model of ALS (SOD1-G93A) inhibited microglial pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic phenotypes, which was translated to a significant increase of 20 days in mouse survival [126].

Nuclear erythroid 2-related receptor (NRF2)

Microglial production of ROS is mediated by nonphagocyte or phagocyte membrane NADPH oxidases, NOX1 and NOX2, respectively [127]. In microglia, as in other cells, ROS are signaling molecules that activate NF-κB-dependent transcription of iNOS and pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 [128].

Normally, NRF2 is sequestered in the cytoplasm by the regulatory protein Keap1. In response to oxidative stress, Keap1 acts as first sensor and upon oxidation releases NRF2. It accumulates in the nucleus and activates transcription of genes containing the antioxidant response element (ARE) sequence, which include genes coding for phase II detoxification enzymes. NRF2-deficient mice show microglia activation and increased expression of iNOS, IL-6 and TNF-α in response to LPS [129]. Conversely, pharmacological up-regulation of NRF2 restores oxidative homeostasis, which attenuates microglia activation and inflammation [129]. A similar effect is attained by overexpression of NRF2 in a microglial cell line activated with LPS. There is induction of the phase II detoxifying antioxidant enzymes and inhibition of p38 MAPK and NF-κB [130].

Gene expression regulation by micro RNAS (miRNAs)

MiRNAs are produced in the nucleus in an unprocessed form and then transported to the cytoplasm where they are cleaved by the RNAse III Dicer. This shorter mRNA of approximately 22 nucleotides gives rise to a mature form of miRNA, which is part of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) that binds target sequences on the mRNA. This results in instability or degradation of the mRNA that prevents translation into protein and silences the expression of genes [131]. Therefore, miRNAs can regulate several cellular mechanisms at the post-transcriptional level and therefore offer an additional level of control of microglial activation.

Similar to other macrophages, activation of a microglial cell line with LPS induces the expression of miRNA-155. The suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS-1) was identified as a target of miRNA-155. Inhibition of miRNA155 prevents the expression of M1-activation markers, such as production of NO, TNF-α and IL-6 in LPS-treated microglia [132]. The increase of miRNA-155 by M1-activated microglia was confirmed in a study that compared differential expression of miRNAs between M1 (LPS treated), M2 (IL-4 treated) and resting primary microglia [38]. The authors found that miRNA-155 and miRNA-145 are the most up-regulated miRNAs in LPS and IL4 stimulated microglia, respectively. miRNA-155 targets the signal transducer and activators of transcription (STAT)-3 pathway associated with pro-inflammatory phenotype, whereas miRNA-145 targets the IL4/STAT-6 signaling pathway.

Dysregulation of miRNAs expression in microglia is shown in neurodegenerative diseases. Namely, the induction of miR-365 and miR-125b correlates with increased expression of TNF-α in microglia obtained from a transgenic mouse model of ALS [133]. On the other hand, miRNA-146a, which is up-regulated in AD-affected brains and in human microglial cells stimulated with Aβ peptide and TNF-α, decreases inflammation-related proteins, such as IRAK-1, a component of TLR-signaling. Altogether, these data suggest that induction of miRNAs in microglia may regulate both inflammatory and anti-inflammatory function of microglial cells in a disease context.

Interestingly, miRNA-124 is selectively expressed by non-activated microglia (CD45lowMHC class II−) and not by other tissue macrophages [134]. Expression of miRNA-124 in microglia can be induced by the CNS microenvironment, namely through interaction with neuronal cells. Actually, miRNA-124 has a role in restraining microglia activation since knock-down of this miRNA leads to increase in morphologically activated cells. miRNA-124 expression is down-regulated in activated microglia (CD45int−hiMHC class II+) upon an M1 type of activation in the onset of EAE, a mouse model of MS. The role of miRNA-124 in driving the state of macrophage activation is further demonstrated by overexpressing miRNA-124 in bone marrow-derived macrophages. Increase of this miRNA is sufficient to reduce the expression of TNF-α and iNOS and to up-regulate TGF-β and markers of M2 type of activation (Arginase 1 and FIZZ1). miRNA-124 seems to control the inflammatory response by targeting the transcription factor CEBPα, whose levels directly correlate with an M1 type of macrophage activation [134].

Deacetylases

Histone acetylation affects chromatin remodeling and is crucial for transcriptional gene regulation [135]. Activation of histone acetyl transferases (HAT) leads to the transfer of acetyl groups from acetyl-CoA to lysine residues of histone tails, causing electrostatic repulsion from nucleosome histones and DNA, which results in chromatin decondensation. This enables the binding of transcription-regulating factors and RNA pol-II activation. In opposition, recruitment of histone deacetylases (HDAC) to promoters, by different repressors of gene transcription, promotes chromatin compaction and gene silencing. Besides the direct role in gene transcription, both HAT and HDACs regulate the activity of several transcription factors, including NF-kB [136].

The assumption that chromatin hyperacetylation increases gene expression suggests that HDAC inhibitors (HDACi) activate gene transcription. Surprisingly, two different HDACi (SAHA and ITF2357) reduce the expression of IL-1β, iNOS and COX-2, both in glial cell cultures and upon injection of LPS into the mouse striatum [137]. The HDAC inhibitor SAHA blocks the production of the neurotoxic metabolite, 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HK) that results from the kynurenine pathway (KP) of tryptophan degradation. This decrease was observed in microglia derived from a transgenic mouse model of HD and in vivo in this same model or in wild-type mice injected with LPS [137]. The authors suggest that activated microglia could have altered gene transcription, which could be restored by the HDAC inhibitors [138].

Sirtuins (Sirts) also belong to the superfamiliy of HDAC enzymes and are categorized as class III HDAC, which are dependent on nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) as a co-factor [139]. Sirt1, 2 and 6 inhibit NF-κB transcriptional activity [140–142]. Sirt1 and 2 deacetylate the lysine 310 in the Re1A/p65subunit of NF-κB repressing NF-κB-regulated gene transcription [141, 142]; deacetylation of histone H3 by Sirt6 releases NF-κB from the gene promoter region [140].

In primary microglia, an increase of Sirt1 expression prevents NF-κB-dependent activation in cells treated with Aβ, which decreases microglial neurotoxicity toward cortical neurons [143].

Recently, we found that Sirt2 regulates microglial-mediated inflammation and neurotoxicity in mice. Sirt2-deficient mice show increased levels of IL-6 and TNF-α, and formation of peroxynitrite as a result of ROS and NO production, when injected with LPS in the cortex. Sirt2 further inhibits microglial neurotoxicity both in vitro and in mice. Curiously, decrease in Sirt1 protein levels did not affect ROS or NO production suggesting that these two Sirts may have distinct targets in microglia, differently affecting activation pathways. We suggest that Sirt2 effect is through deacetylation of NF-κB, though other substrates of Sirt2 may also be involved. We identified upstream regulation of Sirt2 through phosphorylation at S331 residue. When non-phosphorylated at S331, Sirt2 deaceylase activity is increased [144], which correlates with lower levels of acetylated NF-kB in microglia. We propose p35/CDKs as a putative kinase of Sirt2, since it can phosphorylate the protein in vitro and is abundantly expressed in the CNS, though this has to be demonstrated. Sirt2 is the most expressed Sirt in the brain and its activity may prevent excessive microglial activation during aging and in inflammatory conditions [145].

Modulation of microglia inflammatory response

In the last few years, studies with experimental models of neurologic diseases approached the potential of targeting inflammation in the CNS to prevent or ameliorate these types of diseases. Anti-inflammatory therapies were boosted to clinical trials due to the encouraging results in experimental studies, the polymorphisms found in human genes involved in inflammatory pathways and to the epidemiological studies that showed a lower risk of AD and PD in patients without dementia who take non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Unfortunately, the clinical trials have been disappointing so far, which has led to a rethink and claim for new strategies. Due to the microglial properties of phagocytosis and migration to the site of injury, these cells have been tested as specific targets [42] and vehicles for drug delivery [146] in several CNS disorders.

NSAIDs

The canonical molecular targets of classical NSAIDs (i.e., aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac and sulindac) are cyclooxygenases 1 and 2 (COX-1 and COX-2). COX-1 is constitutively expressed in most tissues, including microglia, while COX-2 is the main isoform expressed in inflammatory processes [147]. In this context, Fanet et al. [148] showed that celecoxib, a specific inhibitor of COX-2, attenuates systemic LPS-induced brain inflammation and white matter injury in the neonatal rats This effect was associated with a reduction in the number of activated microglia and astrocytes, decreased levels of IL-1β and TNF-α secretion and inhibition of phosphorylated-p38 MAPK. Moreover, a chronic dose of ibuprofen was shown to reduce AD pathology in Tg2576 transgenic mouse model of AD, such as activated microglia, IL-1β release, neurite dystrophy and amyloid plaques [149]. Despite the epidemiological studies showing that patients without dementia who take NSAIDs for long periods of time seem to have a reduced risk of developing AD [150] and PD [151], clinical trials using COX-2 inhibitors resulted in a negative disease outcome [152]. The administration of rofecoxib, a selective inhibitor of COX-2, during 12 months did not have any effect in slowing dementia in AD patients [153]. This could be either by off target effects of NSAIDs or because some of the inflammatory reactions may be protective rather than deleterious. An alternative explanation for this failure may be the fact that inflammation occurs in the initial phase of AD, while the participants in the clinical trials are most often in an advanced stage of the disease. The epidemiological studies indicate the need for 2 or more years of NSAIDs before the onset of the disease [153].

Minocyline

Minocycline is a second-generation semi-synthetic tetracycline analog that has been in use for over 30 years [154]. Firstly approved for acne vulgaris and rheumatoid arthritis [155], minocycline is a highly lipophilic molecule capable of crossing the BBB [156], which enables test it in the treatment of several experimental models of CNS diseases [157]. Minocycline and related tetracyclines have beneficial anti-inflammatory activity [158] and neuroprotective effects in several brain injury models [159, 160]. These neuroprotective effects are due to anti-apoptotic and anti-oxidant properties in addition to the inhibition of glial (astrocytic/microglial) reactivity and release of inflammatory mediators [161, 162].

In AD, treatment of young transgenic AD mice with minocycline reduces iNOS and COX-2 expression [163], protects hippocampal neurogenesis [164] and improves cognitive performance [165]. Furthermore, the down-regulation of inflammatory markers correlates with a reduction in APP levels. The NF-κB inhibition by minocycline also leads to the inhibition of β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) [163]. Nevertheless, if mice receive minocycline after Aβ deposition had begun, suppression of microglial activation did not improve cognitive performance [165].

In relapsing–remitting EAE, minocyline treatment before or at the onset of disease inhibits microglial activation and concomitantly decreases inflammation and demyelination [166]. More recently, Nikodemova and colleagues showed that minocycline suppressed microglial activation through inhibition of IRF-1 and PKCα/βII [167]. Experimental studies in mouse models of PD, HD and stroke indicate both beneficial and deleterious effects of minocylcine, which in part can be explained by the variety in the protocols used and also by the toxicity of minocycline [168].

So far, the human trials of minocycline treatment show positive results for acute stroke and MS, but adverse effects in ALS [168]. In MS it was demonstrated that minocycline reduced relapse rate and local brain atrophy and active lesions detected by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [169–171].

Development of new therapies that selectively target inflammation in the brain

The understanding of the molecular mechanisms regulating microglial activation further encourages studies that evaluate the target of specific molecules in experimental models of inflammatory diseases of the CNS. Peripheral administration of CD200Fc [172], inhibitors of miRNA-155 [173] and miRNA-124 containing liposomes [134] slows the progression of EAE. These studies show a reduction in the expression of microglial inflammatory markers, though the effect may also rely on inhibition of T cell responses in peripheral lymphoid organs. Therefore, other important innate mechanisms such as control of infectious agents may be affected by these therapies, which is a major concern.

Several approaches have been used to specifically target microglia in the CNS such as viral delivery or direct injection of immune modulators into the brain. Interestingly, miRNA-9 (miR-9)-regulated lentiviral vectors enable robust transgene expression in resident microglia in the rodent brains, since these cells, as opposed to other brain cells, do not express miRNA-9 [174]. This has yet to be proven as a good vector to express modulators of microglial function.

TNF-α is a key pro-inflammatory cytokine, which can mediate tissue damage. Anti-TNF-α medications are used to treat diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, but they may exacerbate the disease in MS patients through unknown mechanisms [175]. Increased TNF-α levels are often observed in neurological disorders including ischemia [176], MS [177] and AD [178], but whether TNF-α signaling actively contributes to or limits neuronal injury in these disorders is still controversial. TNF-α can be produced in a membrane form that binds to TNF receptor I and TNF receptor II, while a soluble form of TNF binds to TNF receptor I. In experimental models of stroke and demyelinating diseases, TNF receptor II was found to be protective [179]. In contrast, TNF receptor I may play a deleterious role, since its deletion in APP23 transgenic mice (AD mouse model) reduces Aβ pathology, microglial activation, BACE1 activity, neuronal cell loss and memory deficits [180]. Accordingly, the soluble form of TNF-α is responsible for loss of dopaminergic neurons in experimental models of PD [181]. Notably, delivery of a dominant-negative TNF-α gene to the substantia nigra that selectively blocks soluble TNF-α prevents progressive loss of neurons and microglia activation [182].

The transcription factor NF-κB is a pivotal molecule in microglial inflammatory response as we discuss here. Intranasal infusion of anti-NF-κB peptides (Tat-NBD) leads to efficient delivery to the CNS and reduced brain atrophy in a mouse model of infection-sensitized neonatal hypoxic–ischemic (HI) brain injury. The protection is associated with NF-κB inhibition.

Binding of CD200 on the neuronal surface to CD200R in microglia inhibits the production of several inflammatory factors, as described in this review. The intrahippocampal delivery of CD200Fc (CD200R agonist) attenuates microglial response induced by LPS or aging as shown by decreased levels of pro-inflammatory factors (MHC class II, MCP-1 and IP-10) and also the impairment of long-term potentiation (LTP) [183].

Microglial phagocytic abilities have also been explored to selectively uptake quantum dots conjugated with potential bioactive molecules. These were successfully tested in mice by stereotaxic injection into the brain [184]. In addition, different microglia phenotypes can be distinctly depleted into the lysolecithin (LPC)-induced model of MS [42]. Selective depletion of M1 microglia was achieved by stereotaxic injection in the corpus callosum of gadolinium chloride, while M2 microglia depletion occurred following injection of mannosylated clodronate liposomes (MCLs), which bind the mannose receptor overexpressed in the M2 phenotype. In this study, the authors showed that M2 microglia are required for oligodendrocyte differentiation into CNS remyelination, while M1 pro-inflammatory microglia are involved in oligodendrocyte progenitors proliferation.

The BBB is an obstacle to CNS therapy and a serious bottleneck in drug development for CNS diseases. Although microglial cells have a different precursor compared to HSC-derived macrophages, in adulthood, and upon irradiation, undefined bone marrow-derived myeloid precursor cells can migrate into the CNS and become resident perivascular macrophages and occasionally microglia [18, 185]. Surprisingly, these blood-derived macrophages have a beneficial role in neurodevelopment disorders such as in Rett syndrome [186].

Moreover, the bone marrow-derived myeloid precursor cells are preferentially recruited to sites of neuronal degeneration [185]. In 2001, Priller and colleagues used transplantation of GFP-tagged bone marrow cells to characterize the spatiotemporal kinetics of CNS cell engraftment into the CNS [185]. The authors showed that GFP-expressing cells were detected in perivascular and leptomeningeal sites as early as 2 weeks after transplant expressing microglial markers (i.e., F4/80, Iba1, low CD45). Interestingly, the same authors observed that upon an ischemic injury, a massive infiltration of GFP-labeled round-shaped cells was confined to the ischemic lesions and differentiated later into microglia cells. These data support that circulating bone marrow-derived cells can be used as effective gene therapy vectors delivering microglial modulators into the CNS and avoid intracranial surgery. Moreover, the use of promoters specific for microglia would ideally lead to expression only in the CNS. In addition, immortalized microglia cells transfected with the LacZ gene could be detected in the rat brain 48 h after intra-arterial injection [187], confirming that microglia could be used to transport a transgene into the brain. Recently, genetically engineered embryonic stem cell-derived microglia intravenously transplanted to EAE mice were shown to migrate to the inflammatory CNS lesions [146]. Most attractively, it was demonstrated that when these cells were genetically modified to express NT-3, mice recovered from EAE, further supporting microglia as suitable therapeutic vehicles. Less differentiated myeloid precursor cells expressing TREM-2, intravenously injected, also migrate to the spinal cord demyelinating lesions and contribute to removing myelin debris and limiting inflammation, thereby ameliorating the signs of disease in EAE [56].

Conclusions and future perspectives

A deleterious inflammatory response with destructive effects in the CNS is a hallmark of several neurologic disorders. Microglial cells together with blood-derived macrophages mediate CNS inflammation. So far, clinical trials have been unable to show the efficacy of anti-inflammatory therapies in this type of disease. Should we give up the anti-inflammatory approach or should we readdress these therapies in the light of increasing knowledge of the circuits underlying microglia activation and regulation? One of the difficulties in translating basic knowledge to the clinics is the use of adequate animal models to test new strategies. At the moment, groups use different models making it difficult to compare results. Better and uniform experimental models, namely of neurodegenerative diseases, are required. Importantly, therapies should be tested on animals after neuron loss is triggered, which would mimic what happens in humans when they are diagnosed with diseases such as AD and PD.

Many of the animal models in use for neurodegenerative diseases are transgenic for human genes, which are expressed under viral promoters or just in neurons. Although most of these models reproduce the microglial pro-inflammatory type of activation, they miss other pathological features of human diseases. Another key aspect that can be missing is the better elucidation of the molecular pathways by which innate immune cells may be beneficial (rather than detrimental) to the CNS. Further understanding of the mechanisms and kinetics of microglial responses in each particular disease will help to define a critical pathway and window for therapeutic intervention.

Specific modifiers of deacetylases, such as Sirts, or miRNAs that can rapidly change microglial activity could be strong candidates if they could be exclusively delivered to microglia.

It is encouraging that nowadays it is already possible to distinguish and abolish specific microglial cell populations or target signaling and transcriptional pathways that are pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic. In the last few years, bone marrow-derived cells emerged as a promising vehicle to deliver anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective molecules to the CNS. We expect that all these new findings will be translated into clinical trials in the forthcoming years.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Oldriska Chutna, Pedro Antas and Maria Salomé Gomes for critical editing and reading of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Schulz C, et al. A lineage of myeloid cells independent of Myb and hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 2012;336(6077):86–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1219179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aloisi F, Ria F, Adorini L. Regulation of T-cell responses by CNS antigen-presenting cells: different roles for microglia and astrocytes. Immunol Today. 2000;21(3):141–147. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01512-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eichhoff G, Brawek B, Garaschuk O. Microglial calcium signal acts as a rapid sensor of single neuron damage in vivo . Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813(5):1014–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, Helmchen F. Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo . Science. 2005;308(5726):1314–1318. doi: 10.1126/science.1110647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davalos D, et al. Fibrinogen-induced perivascular microglial clustering is required for the development of axonal damage in neuroinflammation. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1227. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuhrmann M, et al. Microglial Cx3cr1 knockout prevents neuron loss in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(4):411–413. doi: 10.1038/nn.2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davalos D, et al. ATP mediates rapid microglial response to local brain injury in vivo . Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(6):752–758. doi: 10.1038/nn1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ginhoux F, et al. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science. 2010;330(6005):841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1194637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wake H, et al. Resting microglia directly monitor the functional state of synapses in vivo and determine the fate of ischemic terminals. J Neurosci. 2009;29(13):3974–3980. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4363-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schafer DP, et al. Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron. 2012;74(4):691–705. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parkhurst CN, et al. Microglia promote learning-dependent synapse formation through brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Cell. 2013;155(7):1596–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yrjanheikki J, et al. Tetracyclines inhibit microglial activation and are neuroprotective in global brain ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(26):15769–15774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frank-Cannon TC, et al. Does neuroinflammation fan the flame in neurodegenerative diseases? Mol Neurodegener. 2009;4:47. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blank T, Prinz M. Microglia as modulators of cognition and neuropsychiatric disorders. Glia. 2013;61(1):62–70. doi: 10.1002/glia.22372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kierdorf K, et al. Microglia emerge from erythromyeloid precursors via Pu.1- and Irf8-dependent pathways. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(3):273–280. doi: 10.1038/nn.3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hume DA. The mononuclear phagocyte system. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18(1):49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mildner A, et al. Microglia in the adult brain arise from Ly-6ChiCCR2+ monocytes only under defined host conditions. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(12):1544–1553. doi: 10.1038/nn2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simard AR, Rivest S. Bone marrow stem cells have the ability to populate the entire central nervous system into fully differentiated parenchymal microglia. FASEB J. 2004;18(9):998–1000. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1517fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ajami B, et al. Local self-renewal can sustain CNS microglia maintenance and function throughout adult life. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(12):1538–1543. doi: 10.1038/nn2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ransohoff RM. Microgliosis: the questions shape the answers. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(12):1507–1509. doi: 10.1038/nn1207-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, et al. IL-34 is a tissue-restricted ligand of CSF1R required for the development of Langerhans cells and microglia. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(8):753–760. doi: 10.1038/ni.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wirenfeldt M, et al. Reactive microgliosis engages distinct responses by microglial subpopulations after minor central nervous system injury. J Neurosci Res. 2005;82(4):507–514. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pais TF, Chatterjee S. Brain macrophage activation in murine cerebral malaria precedes accumulation of leukocytes and CD8+ T cell proliferation. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;163(1–2):73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Logan TT, Villapol S, Symes AJ. TGF-beta superfamily gene expression and induction of the Runx1 transcription factor in adult neurogenic regions after brain injury. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e59250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanisch UK, Kettenmann H. Microglia: active sensor and versatile effector cells in the normal and pathologic brain. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(11):1387–1394. doi: 10.1038/nn1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Codolo G, et al. Triggering of inflammasome by aggregated alpha-synuclein, an inflammatory response in synucleinopathies. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e55375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz M, et al. Microglial phenotype: is the commitment reversible? Trends Neurosci. 2006;29(2):68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinez FO, Helming L, Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages: an immunologic functional perspective. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:451–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chao CC, et al. Activated microglia mediate neuronal cell injury via a nitric oxide mechanism. J Immunol. 1992;149(8):2736–2741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhat NR, et al. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p38 subgroups of mitogen-activated protein kinases regulate inducible nitric oxide synthase and tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene expression in endotoxin-stimulated primary glial cultures. J Neurosci. 1998;18(5):1633–1641. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01633.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takeuchi H, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces neurotoxicity via glutamate release from hemichannels of activated microglia in an autocrine manner. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(30):21362–21368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600504200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meda L, et al. Activation of microglial cells by beta-amyloid protein and interferon-gamma. Nature. 1995;374(6523):647–650. doi: 10.1038/374647a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pais TF, et al. Necrotic neurons enhance microglial neurotoxicity through induction of glutaminase by a MyD88-dependent pathway. J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:43. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maezawa I, et al. Amyloid-beta protein oligomer at low nanomolar concentrations activates microglia and induces microglial neurotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(5):3693–3706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.135244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang W, et al. Aggregated alpha-synuclein activates microglia: a process leading to disease progression in Parkinson’s disease. FASEB J. 2005;19(6):533–542. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2751com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Block ML, Zecca L, Hong JS. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(1):57–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tufekci KU, Genc S, Genc K. The endotoxin-induced neuroinflammation model of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2011;2011:487450. doi: 10.4061/2011/487450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freilich RW, Woodbury ME, Ikezu T. Integrated expression profiles of mRNA and miRNA in polarized primary murine microglia. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e79416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao W, et al. Protective effects of an anti-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-4, on motoneuron toxicity induced by activated microglia. J Neurochem. 2006;99(4):1176–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chao CC, Molitor TW, Hu S. Neuroprotective role of IL-4 against activated microglia. J Immunol. 1993;151(3):1473–1481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shimizu E, et al. IL-4-induced selective clearance of oligomeric beta-amyloid peptide(1-42) by rat primary type 2 microglia. J Immunol. 2008;181(9):6503–6513. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miron VE, et al. M2 microglia and macrophages drive oligodendrocyte differentiation during CNS remyelination. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(9):1211–1218. doi: 10.1038/nn.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ponomarev ED, et al. CNS-derived interleukin-4 is essential for the regulation of autoimmune inflammation and induces a state of alternative activation in microglial cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27(40):10714–10721. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1922-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colton CA, et al. Expression profiles for macrophage alternative activation genes in AD and in mouse models of AD. J Neuroinflammation. 2006;3:27. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-3-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vogel DY, et al. Macrophages in inflammatory multiple sclerosis lesions have an intermediate activation status. J Neuroinflammation. 2013;10:35. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-10-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hanamsagar R, Hanke ML, Kielian T. Toll-like receptor (TLR) and inflammasome actions in the central nervous system. Trends Immunol. 2012;33(7):333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klesney-Tait J, Turnbull IR, Colonna M. The TREM receptor family and signal integration. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(12):1266–1273. doi: 10.1038/ni1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmid CD, et al. Heterogeneous expression of the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2 on adult murine microglia. J Neurochem. 2002;83(6):1309–1320. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takahashi K, Rochford CD, Neumann H. Clearance of apoptotic neurons without inflammation by microglial triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2. J Exp Med. 2005;201(4):647–657. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Daws MR, et al. Pattern recognition by TREM-2: binding of anionic ligands. J Immunol. 2003;171(2):594–599. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stefano L, et al. The surface-exposed chaperone, Hsp60, is an agonist of the microglial TREM2 receptor. J Neurochem. 2009;110(1):284–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chouery E, et al. Mutations in TREM2 lead to pure early-onset dementia without bone cysts. Hum Mutat. 2008;29(9):E194–E204. doi: 10.1002/humu.20836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kondo T, et al. Heterogeneity of presenile dementia with bone cysts (Nasu-Hakola disease): three genetic forms. Neurology. 2002;59(7):1105–1107. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.7.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiang T, et al. TREM2 in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;48(1):180–185. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8424-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Napoli I, Neumann H. Protective effects of microglia in multiple sclerosis. Exp Neurol. 2010;225(1):24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takahashi K, et al. TREM2-transduced myeloid precursors mediate nervous tissue debris clearance and facilitate recovery in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. PLoS Med. 2007;4(4):e124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olah M, et al. Identification of a microglia phenotype supportive of remyelination. Glia. 2012;60(2):306–321. doi: 10.1002/glia.21266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Crocker PR, Paulson JC, Varki A. Siglecs and their roles in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(4):255–266. doi: 10.1038/nri2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pillai S, et al. Siglecs and immune regulation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:357–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Angata T, et al. Cloning and characterization of human Siglec-11. A recently evolved signaling molecule that can interact with SHP-1 and SHP-2 and is expressed by tissue macrophages, including brain microglia. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(27):24466–24474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202833200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Y, Neumann H. Alleviation of neurotoxicity by microglial human Siglec-11. J Neurosci. 2010;30(9):3482–3488. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3940-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Claude J, et al. Microglial CD33-related Siglec-E inhibits neurotoxicity by preventing the phagocytosis-associated oxidative burst. J Neurosci. 2013;33(46):18270–18276. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2211-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Griciuc A, et al. Alzheimer’s disease risk gene CD33 inhibits microglial uptake of amyloid beta. Neuron. 2013;78(4):631–643. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mihrshahi R, Barclay AN, Brown MH. Essential roles for Dok2 and RasGAP in CD200 receptor-mediated regulation of human myeloid cells. J Immunol. 2009;183(8):4879–4886. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wright GJ, et al. Lymphoid/neuronal cell surface OX2 glycoprotein recognizes a novel receptor on macrophages implicated in the control of their function. Immunity. 2000;13(2):233–242. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lyons A, et al. CD200 ligand receptor interaction modulates microglial activation in vivo and in vitro: a role for IL-4. J Neurosci. 2007;27(31):8309–8313. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1781-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dentesano G, et al. Inhibition of CD200R1 expression by C/EBP beta in reactive microglial cells. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:165. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lyons A, et al. Dok2 mediates the CD200Fc attenuation of Abeta-induced changes in glia. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:107. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hoek RM, et al. Down-regulation of the macrophage lineage through interaction with OX2 (CD200) Science. 2000;290(5497):1768–1771. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hernangomez M, et al. CD200–CD200R1 interaction contributes to neuroprotective effects of anandamide on experimentally induced inflammation. Glia. 2012;60(9):1437–1450. doi: 10.1002/glia.22366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chitnis T, et al. Elevated neuronal expression of CD200 protects Wlds mice from inflammation-mediated neurodegeneration. Am J Pathol. 2007;170(5):1695–1712. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Koning N, et al. Distribution of the immune inhibitory molecules CD200 and CD200R in the normal central nervous system and multiple sclerosis lesions suggests neuron–glia and glia–glia interactions. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68(2):159–167. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181964113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Walker DG, et al. Decreased expression of CD200 and CD200 receptor in Alzheimer’s disease: a potential mechanism leading to chronic inflammation. Exp Neurol. 2009;215(1):5–19. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Harrison JK, et al. Role for neuronally derived fractalkine in mediating interactions between neurons and CX3CR1-expressing microglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(18):10896–10901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wolf Y, et al. Microglia, seen from the CX3CR1 angle. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:26. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Garton KJ, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme (ADAM17) mediates the cleavage and shedding of fractalkine (CX3CL1) J Biol Chem. 2001;276(41):37993–38001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Maciejewski-Lenoir D, et al. Characterization of fractalkine in rat brain cells: migratory and activation signals for CX3CR-1-expressing microglia. J Immunol. 1999;163(3):1628–1635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zujovic V, et al. Fractalkine modulates TNF-alpha secretion and neurotoxicity induced by microglial activation. Glia. 2000;29(4):305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Noda M, et al. Fractalkine attenuates excito-neurotoxicity via microglial clearance of damaged neurons and antioxidant enzyme heme oxygenase-1 expression. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(3):2308–2319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.169839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cardona AE, et al. Control of microglial neurotoxicity by the fractalkine receptor. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(7):917–924. doi: 10.1038/nn1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rogers JT, et al. CX3CR1 deficiency leads to impairment of hippocampal cognitive function and synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2011;31(45):16241–16250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3667-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Garcia JA, et al. Regulation of adaptive immunity by the fractalkine receptor during autoimmune inflammation. J Immunol. 2013;191(3):1063–1072. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhu W, et al. Elevated expression of fractalkine (CX3CL1) and fractalkine receptor (CX3CR1) in the dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: implications in multiple sclerosis-induced neuropathic pain. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:480702. doi: 10.1155/2013/480702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu J, et al. Suppression of central chemokine fractalkine receptor signaling alleviates amyloid-induced memory deficiency. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34(12):2843–2852. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee S, et al. CX3CR1 deficiency alters microglial activation and reduces beta-amyloid deposition in two Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(5):2549–2562. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cho SH, et al. CX3CR1 protein signaling modulates microglial activation and protects against plaque-independent cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(37):32713–32722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.254268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Saunders AE, Johnson P. Modulation of immune cell signalling by the leukocyte common tyrosine phosphatase, CD45. Cell Signal. 2010;22(3):339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ford AL, et al. Normal adult ramified microglia separated from other central nervous system macrophages by flow cytometric sorting. Phenotypic differences defined and direct ex vivo antigen presentation to myelin basic protein-reactive CD4+ T cells compared. J Immunol. 1995;154(9):4309–4321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sedgwick JD, et al. Isolation and direct characterization of resident microglial cells from the normal and inflamed central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(16):7438–7442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Masliah E, et al. Immunoreactivity of CD45, a protein phosphotyrosine phosphatase. Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;83(1):12–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00294425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tan J, et al. CD45 opposes beta-amyloid peptide-induced microglial activation via inhibition of p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Neurosci. 2000;20(20):7587–7594. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07587.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhu Y, et al. CD45RB is a novel molecular therapeutic target to inhibit Abeta peptide-induced microglial MAPK activation. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(5):e2135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]