Abstract

It is today acknowledged that aging is associated with a low-grade chronic inflammatory status, and that inflammation exacerbates age-related diseases such as osteoporosis, Alzheimer’s disease, atherosclerosis and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Vascular calcification is a complication that also occurs during aging, in particular in association with atherosclerosis and T2DM. Recent studies provided compelling evidence that vascular calcification is associated with inflammatory status and is enhanced by inflammatory cytokines. In the present review, we propose on one hand to highlight the most important and recent findings on the cellular and molecular mechanisms of vascular inflammation in atherosclerosis and T2DM. On the other hand, we will present the effects of inflammatory mediators on the trans-differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cell and on the deposition of crystals. Since vascular calcification significantly impacts morbidity and mortality in affected individuals, a better understanding of its induction and development will pave the way to develop new therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: Vascular smooth muscle cells, Chondrocytes, TNF-α, IL-1β, Inflammasome

Introduction

Paradoxically, whereas aging provokes a drop in bone formation [1], it is associated with vascular calcification (VC) [2, 3]. For instance, it was reported that post-menopausal women with the highest degree of aortic calcification had the lowest bone mineral density [4]. More generally, independent studies showed that in both men and women older than 50, the progression of aortic calcification was positively associated with the rate of decline in bone mineral density and with osteoporotic fractures [5]. One hypothesis to explain this relationship is that the two processes share a common etiology. As will be discussed in the last chapter of this manuscript, a potential shared etiology is inflammation [6].

Vascular calcification accompanies at least two common age-related diseases: atherosclerosis and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). During atherosclerosis, calcification develops in the arterial intima, whereas medial calcification is a hallmark of T2DM. In both diseases, vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) play an important role in the formation of crystals. VSMCs indeed form in large arteries a bone-like tissue, which can result from endomembranous or endochondral ossification [7, 8], and eventually lead to a mature tissue, containing bone marrow [9]. As will be discussed in depth in the next chapters, arterial calcification is clearly associated with the mortality risk in individuals with atherosclerosis and diabetes. For instance, a large population-based cohort aged 30–89 years followed for more than 30 years showed a strong relationship between increasing severity of aortic arch calcification in women and men in middle age and risk of death [2]. In this study, aortic arch calcification was present in 1.9 % of men and 2.6 % of women, and was independently associated with older age. After adjustment for age, aortic arch calcification was associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease in men and women, and with a 1.46-fold increased risk of ischemic stroke among women [2]. In this worrying context, deciphering the mechanisms involved in the initiation and development of calcification in these diseases appears crucial.

Many excellent reviews have been published on the mechanisms of VC. Our aim here is to focus on the role of age-related inflammation in the initiation of this process. Indeed, aging is linked to a chronic, low grade, pro-inflammatory state. This association between aging and inflammation has been referred to as “inflammaging” [10]. Inflammaging has been demonstrated in elderly individuals by the increase in the circulating levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) [11] and of cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-6 [12, 13]. Inflammaging may be conditioned in each individual by life exposition to various stimulators of inflammation, including infections and trauma [14], by psychological stress during aging or even prenatal and early life [15, 16], or by fat accumulation during aging [17–19]. A lack of clear resolution may explain that chronic inflammation accompanies aging. Although inflammatory markers are only increased 2- to 4-fold and thus far from the increases of acute inflammation [20], inflammaging is considered as the most common and important driving force of age-related pathologies, such as atherosclerosis, T2DM and osteoporosis [21]. Inflammation is likely to play a significant role in the development of VC. In a cohort free of clinically apparent cardiovascular disease, CRP levels were associated with coronary artery calcification in both men and women [22]. In addition, several recent convincing articles have demonstrated the role of inflammatory mediators in VC in vitro and in vivo. In this article, after a brief resume of the cellular and molecular mechanisms of ossification, we will focus on VC, beginning with atherosclerosis plaque calcification, and following with that of T2DM. We will deliberately not mention vascular calcification associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Indeed, although inflammation likely plays a role in the development of calcification in CKD patients, calcification is also strongly linked to dysregulated mineral metabolism characterized by long term elevation of serum phosphate levels as well as transient bouts of hypercalcemia, which is not the case in atherosclerosis and T2DM [23].

Endochondral and intramembranous ossification

During bone development and repair, two types of ossification can be encountered. In long bones, endochondral ossification involves the chondrocyte-mediated formation of a cartilaginous calcified template that is subsequently replaced by bone [7]. In contrast, flat bones develop through membranous ossification, which directly relies on the activity of osteoblasts.

Chondrocyte differentiation during endochondral ossification

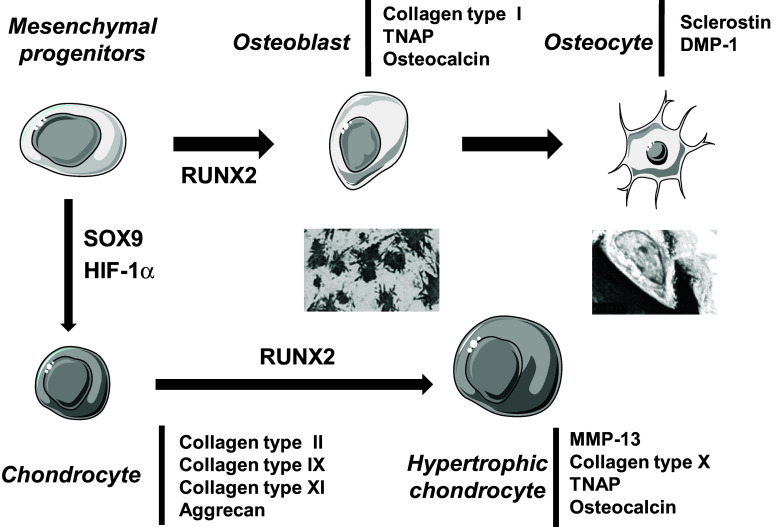

The transcription factor SOX9 appears to play crucial roles in mesenchymal cell condensations and chondrocyte differentiation. Inactivation of SOX9 in limb buds using the Cre/loxP recombination system before the appearance of chondrogenic mesenchymal condensations results in the complete absence of condensations and subsequent cartilage formation [24]. In addition, SOX9 drives the production of an extracellular matrix (ECM) enriched in collagen type II, IX and XI, and glycosaminoglycans (Fig. 1) [7]. During chondrogenesis, in absence of growth plate vascularization, proliferative and differentiated chondrocytes experience hypoxia [25]. Hypoxia activates hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α), which is involved in several processes. Firstly, HIF-1α is necessary for chondrocyte survival during hypoxia [25]. HIF-1α is also required for the expression of chondrocyte markers such as type II collagen [26]. Furthermore, HIF-1α induces the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, which in turn, activates metaphyseal vascular invasion [25]. Following early chondrocyte differentiation, hypertrophic differentiation takes place under the control of the transcription factor RUNX2. RUNX2 expression increases with maturation of chondrocytes, which is severely disturbed in RUNX2-deficient mice [27]. Forced expression of RUNX2 in immature chondrocytes induces type X collagen and matrix metalloprotease-13 expression, tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP) activity and extensive matrix mineralization (Fig. 1) [28]. Eventually, mineralized cartilage vascularization leads to cartilage resorption and new bone apposition.

Fig. 1.

Transcription factors and markers involved in osteoblast or chondrocyte differentiation from mesenchymal progenitors. DMP dentin matrix protein, HIF hypoxia inducible factor, MMP matrix metalloprotease, TNAP tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase

Osteoblast differentiation in endomembranous ossification

In endomembranous ossification, osteoblasts differentiate from mesenchymal progenitors under the control of RUNX2, which notably stimulates the expression of a type I collagen rich matrix (Fig. 1) [29]. Then, osteoblasts express TNAP, which, like in cartilage, induces collagen mineralization [30, 31]. Finally, more mature osteoblasts secrete osteocalcin, a hormone regulating insulin levels and sensitivity [32]. A weak proportion of osteoblasts eventually become surrounded by the matrix they have calcified and give rise to osteocytes, the bone-resident cells. Among other markers, osteocytes secrete sclerostin, an inhibitor of several bone anabolic Wnt growth factors, and dentin matrix protein-1, a molecule controlling phosphatemia [33].

Molecular mechanisms of mineralization

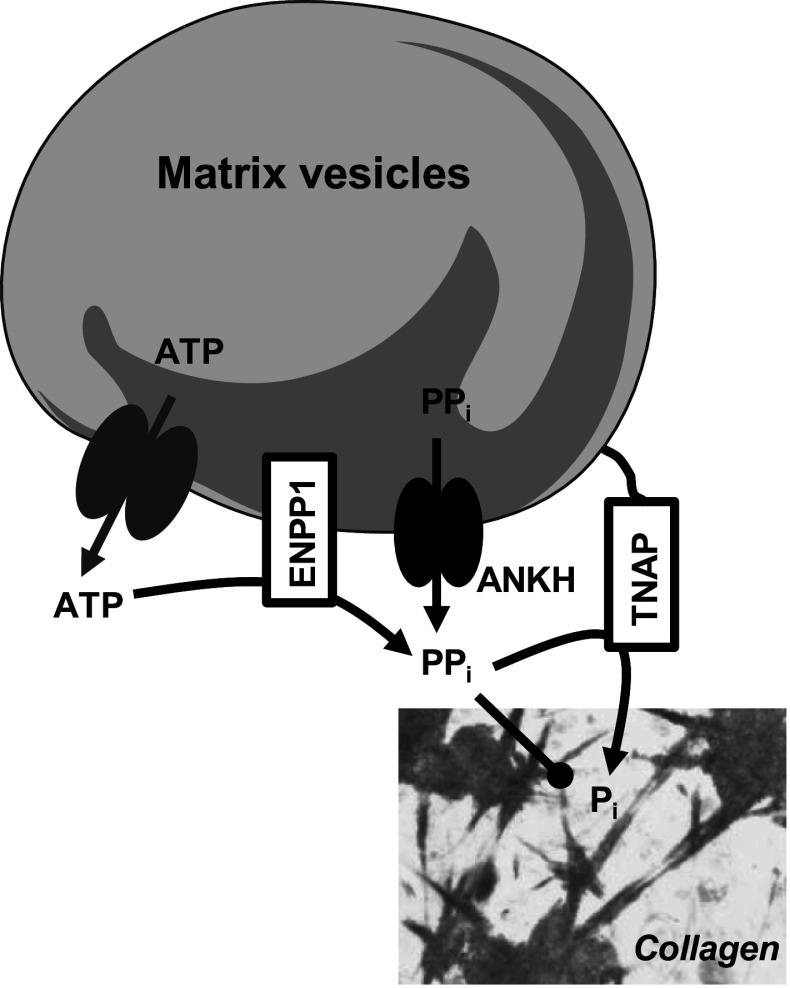

Initiation of mineralization is likely governed by cell-derived matrix vesicles (MVs) [34, 35]. In the cartilage growth plate, their diameter ranges from 30 nm to 1 μm, with an average of approximately 200 nm [34]. It is believed that MVs initiate mineralization in cooperation with collagen fibrils, and that once the first calcium phosphate crystals have coalesced to form the mineralization front, the next steps occur essentially by crystal multiplication, independently of MVs. The membrane of MVs is markedly enriched with glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored TNAP compared with the cell membrane from which they originate [36]. In humans, TNAP is probably the protein that plays the most important role in inducing mineralization. Loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding TNAP leading to hypophosphatasia were first documented in 1988 [37], and since then about 260 mutations have been reported [38]. The most severe form of hypophosphatasia manifests in utero with dramatic hypomineralization, and causes death at, or soon after, birth. It has been shown that TNAP stimulates crystal formation by hydrolyzing the mineralization inhibitor inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) (Fig. 2) [30, 31, 39]. PPi is produced in the ECM by ankylosis protein homolog (ANKH) and ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase phosphodiesterase 1 (ENPP1). ANKH is a transmembrane protein that exports PPi. Mutations in ANKH result in two distinct diseases associated with excessive mineralization: craniometaphyseal dysplasia [40, 41] and familial calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease [42, 43]. ENPP1 is a membranous protein that hydrolyses ATP in the ECM to generate PPi. Mutations in the ENPP1 gene are responsible for generalized arterial calcification in infancy (GACI) or idiopathic infantile arterial calcification [44, 45]. Calcification of large and medium-sized arteries and stenosis due to myointimal proliferation are significant features of the GACI phenotype and most affected children die in early infancy [46]. Causes of death are myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, persistent arterial hypertension, or multi-organ failure [47]. In cartilage and bone, crystal formation resulting from decreased PPi levels occurs in association with collagen fibrils and consist in a non-stoichiometric, calcium-deficient, carbonated apatite, whose composition vary with the age of crystals. In particular, aging of crystals is characterized by loss of acidic phosphate groups and incorporation of carbonate ions [48].

Fig. 2.

Induction of tissue mineralization by matrix vesicles. ANKH ankylosis protein homolog, ENPP1 ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase phosphodiesterase 1, PP i inorganic pyrophosphate, TNAP tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase

Inflammation and vascular calcification in atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is an age-related disease. In humans, the early atherosclerotic lesions can usually be found in the aorta in the first decade of life. They consist of subendothelial accumulations of cholesterol-engorged macrophages, called “foam cells” (type I lesions) [49]. Then “fatty streak” lesions (type II lesions) are observed in the coronary arteries in the second decade and in the cerebral arteries in the third or fourth decades. Fatty streaks are not clinically significant, but are the precursors of intermediate lesions characterized by the accumulation of lipid-rich necrotic debris and VSMCs (type III lesions). Advanced atherosclerotic lesions can also be subdivided into three main histologically characteristic types: IV, V, and VI [50]. In type IV lesions, a dense accumulation of extracellular lipid occupies an extensive but well-defined region of the intima, enclosed by a “fibrous cap” consisting of VSMCs and ECM. This type of extracellular lipid accumulation is known as the lipid core. Type V lesions are defined as lesions in which prominent new fibrous connective tissue has formed. Morbidity and mortality from atherosclerosis is largely due to type IV and type V lesions in which disruptions of the lesion surface, hematoma or hemorrhage, and thrombotic deposits have developed [50]. Type IV or V lesions with one or more of these additional features are classified as type VI and may also be referred to as complicated lesions.

Calcification is a hallmark of atherosclerosis [9]. Coronary arterial calcification is indeed part of the development of atherosclerosis, occurs almost exclusively in atherosclerotic arteries, and is absent in the normal vessel wall [50, 51]. It has been estimated that over 70 % atherosclerotic plaques observed in the aging population are calcified [52]. Early calcifications are usually noted in stage III specimens, with intermediate and solid calcifications becoming increasingly prominent within advanced plaques, especially stages V and VI [53, 54]. The prevalent sites of calcification are located in the deeper regions of the intima and the atheroma [53].

The role of coronary calcification in plaque rupture has long been controversial [55–57]. Not all individuals with high coronary calcification develop myocardial infarction, and some cases of myocardial infarction occur in the absence of high levels of coronary arterial calcification [58]. Although there is a positive correlation between the site and the amount of coronary artery calcium and the percent of coronary luminal narrowing at the same anatomic site, the relation is nonlinear and has large confidence limits [59]. It has been proposed that atherosclerotic plaque proceeds through progressive stages where instability and rupture can be followed by calcification, perhaps to provide stability to an unstable lesion [60]. That is, patients who have calcified plaque are also more likely to have non-calcified or “soft” plaque that is prone to rupture and acute coronary thrombosis [61]. On the other hand, a recently growing body of evidence indicates that the direct assessment of coronary artery calcium can provide independent and incremental prognostic information over and above the traditional Framingham risk score. A number of recent publications have indeed reported on the incremental prognostic value of coronary artery calcification (CAC) in large series of patients including asymptomatic self-referred and population cohorts [62–66]. The American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association expert consensus proposed that measurement of CAC is reasonable for cardiovascular risk assessment in asymptomatic adults at intermediate risk (10–20 % 10-year risk), and low-to-intermediate risk (6–10 % 10-year risk) [67]. Early detection of CAC will allow to initiate lipid-lowering therapy and lifestyle modifications [68].

Actually, recent data indicate that two types of calcification may be distinguished in the atherosclerotic plaque. Microcalcifications may form first, consisting of crystals measuring less than 50 µm in diameter, often as small as a single calcified macrophage, and invisible in micro-computed tomography [69]. These microcalcifications have been mentioned in several intravascular imaging studies as a coronary calcification pattern that is extremely difficult to detect. Interestingly, macrophages have been reported to release mineralization-competent structures resembling to MVs and exosomes [70]. It is therefore possible that some microcrystals may precipitate independently on VSMCs, in association with inflammatory cells recruited in the intima. It has been proposed that the rupture of a plaque may be triggered by the explosive growth of small voids in the tissue in the vicinity of closely clustered microcalcifications [71]. In this model, the microcalcifications per se would not be dangerous, in contrary to their spacing and location in the cap relative to the location of the minimum cap thickness [71]. Vulnerable plaques therefore tend to be those with less extensive calcium deposits frequently seen in a spotty distribution [72], a finding supported by intravascular ultrasound studies of patients with acute coronary syndromes [73].

Subsequently to the formation of microcrystals, a propagation phase follows, due to the phenotypic conversion of VSMCs leading to ossification [74]. Indeed, human calcified plaques have been found to express mRNA of several markers of chondrocytes and/or osteoblasts such as RUNX2, TNAP and osteocalcin [75]. Similarly, in the apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE) −/− mouse model of atherosclerosis, calcified cartilage is formed in advanced plaques [76, 77]. In these mice, VSMCs are likely responsible for calcification since VSMC-specific RUNX2 deficiency prevents plaque calcification [78]. VSMCs are characterized by phenotypic plasticity that allows them to de-differentiate into mesenchymal precursors and/or trans-differentiate into chondrocytes. Interestingly, SM22 −/− mice develop medial chondrogenesis after carotid denudation with a fall in VSMC markers such as myocardin transcription factor and α-smooth muscle actin and concomitant enhanced expression of SOX9 and type II collagen [79]. In atherosclerotic plaques, VSMC-derived chondrocytes appear to release MVs [80] as do normal mineralizing chondrocytes. Their diameter ranges from 100 to 700 nm, and is therefore roughly the same as that of chondrocytes-derived MVs [34]. They are also enriched in TNAP [80]. Finally, like in growth plate cartilage, the crystals formed in human atherosclerotic plaques consist of a carbonated apatite [81].

Both microcalcifications and cartilage-like tissue formation may be triggered by inflammatory signals. In humans, focal arterial inflammation, as quantified by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose/positron emission tomography (PET), was suggested to precede calcification within the same locations [82]. In this study, it is however, possible that microcalcifications were present earlier but were not detected. 18F-fluoride PET recently allowed the identification of macrophage infiltration and active microcalcification at the sites of plaque rupture [83]. Microcalcification may be induced by inflammation in more than one way, as discussed below. Additionally, osteogenesis in atherosclerotic plaques was also reported to associate with inflammation in ApoE −/− mice as revealed by in vivo imaging [84].

Role of tumor necrosis factor-α

Inflammatory mechanisms play a central role in mediating all phases of atherosclerosis, from initial recruitment of circulating leukocytes to the arterial wall to eventual rupture of the unstable plaque [85]. Many cytokines likely participate in atherosclerosis, including TNF-α, IL-1α and IL-1β, IL-4, interferon-γ (IFN-γ) [86]. Among these cytokines, TNF-α might be particularly important. TNF-α is predominantly expressed by macrophages in the plaque and mice deficient in both ApoE and TNF-α exhibit a 50 % reduction in aorta lesion size after 10 weeks of Western-style diet feeding [87, 88]. Among the multiple effects exerted by TNF-α at different atherosclerosis stages, which are likely to impact calcification indirectly, direct effects of TNF-α on crystal formation seem to occur. TNF-α indeed activates VSMCs to form calcium deposits (Table 1) [89–97]. TNF-α may exert its effects by stimulating the release of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-2, a potent bone anabolic factor [98]. TNF-α may also enhance BMP-2 activity by reducing the levels of its inhibitor, matrix Gla protein (MGP), in VSMCs [98, 99]. In parallel, TNF-α activates NF-κB to decrease expression of ANKH and reduce PPi export [100]. Moreover, TNF-α decreases extracellular PPi levels through TNAP activation [89]. Collectively, these effects of TNF-α likely contribute to activate VSMC trans-differentiation and trigger mineralization of the ECM (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Chronological presentation of the most important reports of the effects of inflammatory cytokines on VSMC trans-differentiation and calcification in vitro

| Cytokine | Cell source | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | Bovine VSMCs | The first report that TNF-α stimulates TNAP and calcium deposition in VSMCs. Mechanisms appear to involve PKA | [90] |

| TNF-α and OSM | Human VSMCs | THP-1 macrophages activate VSMCs to produce TNAP and mineralize through the secretion of TNF-α and OSM | [91] |

| IL-4 | Human VSMCs | Stimulates calcium deposition through RUNX2 | [97] |

| TNF-α | Mouse aortic myofibroblasts | Stimulates TNAP through canonical Wnt signaling | [154] |

| TNF-α | Rat VSMCs |

Increases Msx2, RUNX2 and BMP-2 expression Stimulates TNAP and calcium deposition |

[92] |

| TNF-α | Human VSMCs |

Increases Msx2, RUNX2, osterix and BSP expression Stimulates TNAP and calcium deposition through NF-κB and Msx2 |

[93] |

| TNF-α and IL-1β | Human VSMCs | Stimulates TNAP through PPARγ inhibition | [89] |

| TNF-α | Human VSMCs | Increases calcium deposition through NF-κB-mediated decrease in ANKH expression and PPi export | [100] |

| TNF-α | Mouse aortic myofibroblasts | Increases calcium deposition through TNFR1, reactive oxygen species and Msx2 | [95] |

| TNF-α | Rat aortic rings and hVSMCs | Increases BMP-2 and calcium deposition | [94] |

| TNF-α and IL-6 | Mouse VSMCs |

TNF-α decreases MGP expression TNF-α increases RUNX2, TNAP and calcium deposits IL-6 amplifies TNF-α effects on calcium deposition |

[99] |

| TNF-α | Mouse MOVAS | Stimulates calcium deposition through PKA and ATF4 | [96] |

| Inflammasome | Mouse VSMCs | Inflammasome inhibition prevents calcium deposition | [120] |

Fig. 3.

Induction and pro-calcifying effects of inflammatory cytokines in atherosclerosis and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Arrows references and words in brown concern atherosclerosis; arrows, references and words in blue concern more specifically T2DM, and arrows, references and words appearing in black concern cytokine effects on VSMC “trans-differentiation” and mineralization, which are likely to concern both atherosclerosis and T2DM

Role of IL-1 and the inflammasome

IL-1α and IL-1β are expressed in human atherosclerotic plaques, particularly by macrophages and endothelial cells [101]. In mouse, IL-1 receptor I deficiency [102], as well as overexpression of the IL-1 receptor antagonist IL-1Ra [103, 104], lead to less atherosclerosis. Conversely, IL-1Ra-deficient mice display exacerbated atherosclerosis [104, 105], and spontaneous aortitis [106, 107]. Several molecules have been reported to activate IL-1 release, through or independently from inflammasome activation. The inflammasome is a multiprotein complex that promotes IL-1β secretion after its cleavage by caspase-1. Cholesterol crystals, which form early during atherogenesis [108], stimulate macrophages to release IL-1β through inflammasome activation [108, 109], and IL-1α independently of it [110]. Fatty acids also likely contribute to generate vascular inflammation. In ApoE −/− mice fed a high-cholesterol diet, four fatty acids (palmitic acid, stearic acid, oleic acid and arachidonic acid) represented two-thirds of the fatty acid pool found in atherosclerotic plaques [111]. Of these, oleic acid induced IL-1α production independently from inflammasome activation [111]. Another report showed that palmitic acid triggers the release of IL-1β through AMP kinase inhibition and inflammasome activation [112]. Sphingolipids are also important inflammatory players in atherosclerosis that might increase IL-1 secretion [113]. Enhanced uptake of sphingolipid rich lipoproteins has been proposed, but increased local sphingolipid synthesis in the atherosclerotic plaque has also been observed and considered as a contributing mechanism [113]. Degradation of sphingomyelin on the LDL particle surface can promote aggregation by ceramide–ceramide interactions, thus promoting initiation of atherosclerosis [114, 115]. In ApoE-knockout mice, deficiency of acid sphingomyelinase, which generates ceramide from sphingomyelin, decreases early foam cell lesion areas by up to 50 % [114]. Interestingly, ceramide in particular activates the inflammasome to release IL-1β [116]. The inflammasome seems therefore to be a central component in the inflammation induced by cholesterol crystals, fatty acids and sphingolipids. Although like TNF-α, IL-1β likely exacerbates the whole development of atherosclerotic plaques and not specifically calcification, it may also directly stimulate calcification in VSMCs as TNF-α does. Indeed, in vitro studies reported that IL-1β stimulates TNAP activity and calcification in VSMCs [89, 117]. In addition, several inflammasome activators have been shown to enhance calcification. For instance, palmitic acid induces calcification in human VSMCs [118, 119]. Proposed mechanisms include reactive oxygen species generation [119], and the stimulation of BMP-2 expression [118]. Finally, it was recently reported that inhibition of inflammasome prevents calcification in cultured VSMCs [120].

Inflammatory cytokines are induced by apoptosis and necrosis

The presence of apoptotic macrophages and VSMCs in atherosclerotic plaques has been confirmed by a number of studies [121]. Apoptotic indices are low in early lesions, but increase in frequency as lesions develop, in both the necrotic core and fibrous cap. Macrophage and VSMC apoptosis is induced by oxidized LDL [122], or oxysterols [123]. Interestingly, whereas in vascular aging VSMC apoptosis doesn’t induce inflammation, it does in atherosclerosis. This is because the clearance of apoptotic bodies is impaired in atherosclerotic plaques [124], where apoptotic cells are subject to secondary necrosis [125]. Necrotic cells release the alarmin IL-1α, which likely contributes to initiate calcification. Alternatively, uncleared apoptotic bodies themselves may represent a nidus for calcification, with charged phosphatidylserine-bearing membranes able to nucleate crystals [126]. Moreover, whereas living cells carefully separate calcium (in the sarcoplasm and the mitochondria) from Pi (in the cytoplasm), both ions may be incorporated into apoptotic bodies, and contribute to the formation of crystals. In cultures of VSMCs [126], and interestingly also in cultures of chondrocytes [127], inhibition of apoptosis by the broad-range caspase inhibitor ZVAD-FMK reduces the extent of mineralization. Since this inhibitor blocks caspase-1, it would be interesting to determine whether it acts through inhibition of apoptosis and/or that of the inflammasome [120]. Finally, crystals may activate a vicious cycle associating apoptosis and inflammation. Indeed, crystals induce apoptosis in VSMCs, after phagocytosis and dissolution in lysosomes [128], and activate macrophages to secrete more TNF-α and IL-1β [129].

Inflammatory cytokines are induced by VSMC senescence

During aging, cell senescence is likely to induce VMSC trans-differentiation and calcification. Replicative senescence of VMSCs enhances their trans-differentiation and calcification [130]. Senescence can result from lamin A accumulation in the nucleus due to abnormal maturation; and it was proposed that lamin A interferes with DNA damage repair signaling [131]. The most sever form of laminopathy due to mutations in the gene encoding lamin A is the Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HPGS) [132]. Patients with HPGS suffer premature aging, including premature atherosclerosis and calcification [133–135], leading to myocardial infarction or stroke at an age of 13 years [132, 136–138]. Prelamin A accumulates in calcifying VSMCs in vivo and its overexpression in vitro promotes trans-differentiation and calcification [139]. Liu et al. [139] reported that prelamin A accumulation induces DNA damage, that in turn triggers the secretion of pro-mineralizing factors. Interestingly, DNA damage induces the secretion of IL-6, whereas inhibition of the DNA damage response inhibits IL-6 secretion by VSMCs, suggesting that senescence exerts paracrine pro-inflammatory effects. Finally, the factors that drive prelamin A accumulation in aging VSMCs remain to be identified.

Inflammation and vascular calcification associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus

Like atherosclerosis, T2DM is an age-related disease with a chronic pro-inflammatory state [140]. In T2DM, chronic elevation of circulating nutrients such as glucose and free fatty acids contributes to the induction of inflammatory processes observed within various tissues, including pancreatic islets and the vascular wall [140, 141]. T2DM is associated with calcification of the media [9]. In 4553 subjects studied in a 20-year longitudinal study, calcification was shown to first appear in the feet and develop proximally [142]. In this study, diabetic patients with medial arterial calcification, compared with diabetic patients without medial arterial calcification, had 5.5-fold the rate of amputations [142]. Moreover, in another study of 1059 patients with T2DM, femoral arterial calcification was also found to predict lower limb amputation [143]. Even more worrying, compared to the general population, patients with diabetes tend to have more atherosclerotic plaques on coronary computed tomography angiography than patients without diabetes, notably more calcified plaques [144, 145], and are significantly more likely to develop coronary heart disease [142, 146, 147]. In adults with diabetes, measurement of CAC has recently been considered helpful for cardiovascular risk assessment in asymptomatic adults with diabetes [67].

Like in atherosclerotic plaques, it would seem that VC associated with T2DM recapitulates endochondral ossification. Studies of human medial calcification in T2DM and aging showed that the VSMCs lose the expression of calcification inhibitors, such as MGP, and begin to express differentiation markers of chondrocytes such as type II collagen [148]. Moreover, histological examination of femoral arteries from two patients with long-term T2DM revealed the presence of type II collagen in foci of cartilaginous metaplasia, providing evidence for endochondral ossification [149]. In addition, in low-density lipoprotein receptor mutant (Ldlr −/−) mice, T2DM accelerated cartilage formation and calcification in the aorta [150].

Role of TNF-α and IL-1β in medial calcification in T2DM

Cytokine stimulation of VSMCs probably plays an important role in calcification associated with T2DM. It is well-known that in humans, glucose induces the secretion of several inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and IL-6 [151]. Hyperglycemia is likely to induce vascular inflammation. Indeed, in mouse, overexpression of GLUT1 in VSMC induces arterial wall inflammation [152]. In human and rodent VSMCs also, glucose induces the secretion of TNF-α [153]. As we mentioned above, TNF-α is able to induce calcification in cultures of VSMC [89, 90], and in vivo, the TNF-α inhibitor infliximab has been shown to prevent medial calcification in ldlr −/− diabetic mice, without reducing obesity, hypercholesterolemia and hyperglycaemia [154]. However, the fact that only 30 % of calcium deposits were prevented in the latter study suggests that other inflammatory factors are involved in the pro-calcifying effects of glucose. IL-1β may be one of these inflammatory factors, although in vivo studies have only reported yet that IL-1β worsens T2DM in general but not vascular calcification specifically. Evidence of its importance in the progression of metabolic disorders comes from the encouraging results of a phase 3 clinical trial with T2DM patients treated with the IL-1Ra anakinra [155]. Several articles have highlighted the role of IL-1β in the development of insulin resistance. Mice deficient in NLRP3 (NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3), which lack inflammasome-dependent release of IL-1β show improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity [156, 157]. Accordingly, caspase-1 inhibition increases insulin sensitivity [158]. Activators of the inflammasome-mediated release of IL-1β in T2DM include glycemia, ceramides, and islet amyloid polypeptide [159]. Glucose itself stimulates the release of IL-1β from pancreatic β-cells [160]. Recently, glucose has been shown to enhance the levels of thioredoxin-interacting protein, a protein that interacts with the NLRP3 inflammasome to trigger IL-1β secretion [156].

Glucose treatment of VSMCs has been shown to accelerate calcification, and up-regulate expression of osteoblast/chondrocyte markers (Fig. 3). For instance, bovine VSMCs incubated with high levels of glucose expressed more RUNX2 and osteocalcin, displayed higher alkaline phosphatase activity and mineralization capacity compared to cells cultured in normal glucose levels [161]. In addition, in culture of human aortic smooth muscle cell, glucose increased the expression of BMP-2 and RUNX2 [162]. Furthermore, in rat VSMCs also, high glucose levels increased alkaline phosphatase activity, mineralization and osteocalcin expression [163, 164]. Finally, medial calcification appears to relate to the degree of glycemic control [165]. Collectively, these data showing that (1) glucose induces inflammation in VSMCs, (2) activates the inflammasome-dependent release of IL-1β, (3) IL-1β stimulates VSMC to calcify, and (4) inflammasome inhibition prevents calcification suggest that glucose may stimulate calcification in part through IL-1β activation.

Can we reconcile the opposite role of inflammation on vascular calcification and bone formation?

Inflammation may thus be a leading cause of VC [166]. Both CRP and inflammatory cytokines are associated with increased CAC [22, 166, 167]. On the opposite, inflammation is a well-recognized inhibitors of bone formation [1]. For instance, using a cohort of 168 randomly selected men and women with a mean age of 63 years, Ding and collaborators reported that higher levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and CRP are associated with increased bone loss over 3 years of follow-up [168]. An inverse association between CRP levels and bone mineral density has also been observed in a sample of 2807 elderly females [169]. Moreover, in healthy individuals above 40, CRP levels represent a strong risk predictor of nontraumatic fractures, and its predictive significance extend to levels commonly regarded as low grade inflammation [170]. In the Geelong Osteoporosis study, the fracture risk was increased 24–32 % for each SD increase in CRP levels in elderly women [171]. Finally, in healthy individuals over 70, Cauley and collaborators have shown that in addition to CRP levels, high serum levels of inflammatory markers IL-6, TNF-α, and TNF receptors, can also predict a higher incidence of non-traumatic fractures [172]. These effects of inflammation are probably due to increased bone resorption and decreased bone formation [1]. In cultured osteoblasts, TNF-α and IL-1β inhibit the expression of collagen type I, which is expressed early during differentiation, and the secretion of osteocalcin, a marker of mature cells [173]. The inhibition of collagen may account for a great part in the inhibition of bone formation, since collagen is the most abundant protein in bone, where it represents the framework for crystal deposition. In osteoblasts, TNF-α inhibitory effects are due to decreased expression of RUNX2 [173], and increased Smurf1-mediated RUNX2 degradation [174]. The molecular effects of IL-1β on osteoblasts have been much less investigated but it seems that in human osteoblasts, IL-1β has the same effects on RUNX2 activity and on collagen and osteocalcin expression [173].

Concerning the effects of inflammation on endochondral ossification, it is well-known that children with chronic inflammatory diseases experience impaired longitudinal growth rate as compared to healthy ones. In cultured whole rat metatarsal bones, both IL-1β and TNF-α impair metatarsal longitudinal growth, decrease the proliferation of growth plate chondrocytes, and increase chondrocyte apoptosis [175]. In cultured chondrocytes, both cytokines decrease TNAP activity and mineralization [89]. Strikingly, whereas inflammasome may be involved in the induction of VC [120], its activation in vivo causes growth retardation and osteopenia [176].

Therefore, whereas TNF-α and IL-1β seem to accelerate VC in atherosclerosis and T2DM, they are potent inhibitors of osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation and mineralization. These contradictory effects are also observed in ankylosing spondylitis (AS), an inflammatory disease that affects the axial skeleton and the peripheral joints, where excessive tendon and ligament ossification accompanies systemic bone loss [177]. In AS, these opposite patterns of ossification may be reconciled by the observation that ossification proceeds in locations where inflammation has resolved [178]. That resolution of inflammation is a prerequisite for ossification is also a condition for bone fracture healing. Indeed, a necessary early inflammation phase takes place during bone repair, whereas inflammation slows bone formation later on [179]. One can therefore hypothesize that inflammation plays an activating role in the initiation of ossification and VC by promoting the expression of osteogenic growth factors, and that these factors efficiently stimulate mineralization when and where inflammation has resolved. In vascular cells, TNF-α and/or IL-1β increase the levels of BMP-2 and osteogenic Wnt family members [98, 154]. Atherosclerosis and T2DM are chronic low-grade inflammatory diseases, during which periods of inflammation are separated by periods of resolution. It is therefore conceivable that active calcification proceeds when inflammation has resolved under the action of BMP and Wnt factors.

In conclusion, the data reviewed here indicate that atherosclerosis and T2DM, two age-related diseases with an inflammatory character, develop vascular calcification in response to inflammatory signals. Efforts to determine the nature and role of these signals in vascular calcification in vivo are therefore warranted.

Abbreviations

- ANKH

Ankylosis protein homolog

- BMP

Bone morphogenetic protein

- CAC

Coronary artery calcification

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- ENPP1

Ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase phosphodiesterase 1

- FDG

Fluorodeoxyglucose

- GACI

Generalized arterial calcification in infancy

- HIF

Hypoxia inducible factor

- HPGS

Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome

- IFN

Interferon

- IL-1Ra

Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist

- MGP

Matrix Gla protein

- MMP

Matrix metalloprotease

- MVs

Matrix vesicles

- NLRP3

NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- PPi

Inorganic pyrophosphate

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- VSMCs

Vascular smooth muscle cells

- TNAP

Tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

References

- 1.Lencel P, Magne D. Inflammaging: the driving force in osteoporosis? Med Hypotheses. 2011;76:317–321. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iribarren C, Sidney S, Sternfeld B, Browner WS. Calcification of the aortic arch: risk factors and association with coronary heart disease, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease. JAMA. 2000;283:2810–2815. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.21.2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witteman JC, Kannel WB, Wolf PA, Grobbee DE, Hofman A, D’Agostino RB, Cobb JC. Aortic calcified plaques and cardiovascular disease (the Framingham Study) Am J Cardiol. 1990;66:1060–1064. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90505-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulz E, Arfai K, Liu X, Sayre J, Gilsanz V. Aortic calcification and the risk of osteoporosis and fractures. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4246–4253. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naves M, Rodríguez-García M, Díaz-López JB, Gómez-Alonso C, Cannata-Andía JB. Progression of vascular calcifications is associated with greater bone loss and increased bone fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:1161–1166. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0539-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sage AP, Tintut Y, Demer LL. Regulatory mechanisms in vascular calcification. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:528–536. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magne D, Julien M, Vinatier C, Merhi-Soussi F, Weiss P, Guicheux J. Cartilage formation in growth plate and arteries: from physiology to pathology. Bioessays. 2005;27:708–716. doi: 10.1002/bies.20254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shao JS, Cai J, Towler DA. Molecular mechanisms of vascular calcification: lessons learned from the aorta. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1423–1430. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000220441.42041.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doherty TM, Fitzpatrick LA, Inoue D, Qiao JH, Fishbein MC, Detrano RC, Shah PK, Rajavashisth TB. Molecular, endocrine, and genetic mechanisms of arterial calcification. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:629–672. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franceschi C, Capri M, Monti D, Giunta S, Olivieri F, Sevini F, Panourgia MP, Invidia L, Celani L, Scurti M, Cevenini E, Castellani GC, Salvioli S. Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ballou SP, Lozanski FB, Hodder S, Rzewnicki DL, Mion LC, Sipe JD, Ford AB, Kushner I. Quantitative and qualitative alterations of acute-phase proteins in healthy elderly persons. Age Ageing. 1996;25:224–230. doi: 10.1093/ageing/25.3.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brüünsgaard H, Pedersen BK. Age-related inflammatory cytokines and disease. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2003;23:15–39. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8561(02)00056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruunsgaard H, Andersen-Ranberg K, Hjelmborg J, Pedersen BK, Jeune B. Elevated levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha and mortality in centenarians. Am J Med. 2003;115:278–283. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00329-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finch CE, Crimmins EM. Inflammatory exposure and historical changes in human life-spans. Science. 2004;305:1736–1739. doi: 10.1126/science.1092556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Preacher KJ, MacCallum RC, Atkinson C, Malarkey WB, Glaser R. Chronic stress and age-related increases in the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9090–9095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1531903100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veenema AH, Reber SO, Selch S, Obermeier F, Neumann ID. Early life stress enhances the vulnerability to chronic psychosocial stress and experimental colitis in adult mice. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2727–2736. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pedersen M, Bruunsgaard H, Weis N, Hendel HW, Andreassen BU, Eldrup E, Dela F, Pedersen BK. Circulating levels of TNF-alpha and IL-6-relation to truncal fat mass and muscle mass in healthy elderly individuals and in patients with type-2 diabetes. Mech Ageing Dev. 2003;124:495–502. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(03)00027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sepe A, Tchkonia T, Thomou T, Zamboni M, Kirkland JL. Aging and regional differences in fat cell progenitors—a mini-review. Gerontology. 2011;57:66–75. doi: 10.1159/000279755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tilg H, Moschen AR. Adipocytokines: mediators linking adipose tissue, inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:772–783. doi: 10.1038/nri1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krabbe KS, Pedersen M, Bruunsgaard H. Inflammatory mediators in the elderly. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:687–699. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franceschi C, Bonafè M. Centenarians as a model for healthy aging. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:457–461. doi: 10.1042/bst0310457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Kupka MJ, Manning WJ, Clouse ME, D’Agostino RB, Wilson PW, O’Donnell CJ. C-reactive protein is associated with subclinical epicardial coronary calcification in men and women: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2002;106:1189–1191. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000032135.98011.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shanahan CM, Crouthamel MH, Kapustin A, Giachelli CM. Arterial calcification in chronic kidney disease: key roles for calcium and phosphate. Circ Res. 2011;109:697–711. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.234914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akiyama H, Chaboissier MC, Martin JF, Schedl A, de Crombrugghe B. The transcription factor Sox9 has essential roles in successive steps of the chondrocyte differentiation pathway and is required for expression of Sox5 and Sox6. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2813–2828. doi: 10.1101/gad.1017802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schipani E, Ryan HE, Didrickson S, Kobayashi T, Knight M, Johnson RS. Hypoxia in cartilage: HIF-1alpha is essential for chondrocyte growth arrest and survival. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2865–2876. doi: 10.1101/gad.934301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfander D, Cramer T, Schipani E, Johnson RS. HIF-1alpha controls extracellular matrix synthesis by epiphyseal chondrocytes. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1819–1826. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inada M, Yasui T, Nomura S, Miyake S, Deguchi K, Himeno M, Sato M, Yamagiwa H, Kimura T, Yasui N, Ochi T, Endo N, Kitamura Y, Kishimoto T, Komori T. Maturational disturbance of chondrocytes in Cbfa1-deficient mice. Dev Dyn. 1999;214:279–290. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199904)214:4<279::AID-AJA1>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Enomoto H, Enomoto-Iwamoto M, Iwamoto M, Nomura S, Himeno M, Kitamura Y, Kishimoto T, Komori T. Cbfa1 is a positive regulatory factor in chondrocyte maturation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8695–8702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fakhry M, Hamade E, Badran B, Buchet R, Magne D. Molecular mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation towards osteoblasts. World J Stem Cells. 2013;5:136–148. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v5.i4.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hessle L, Johnson KA, Anderson HC, Narisawa S, Sali A, Goding JW, Terkeltaub R, Millan JL. Tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase and plasma cell membrane glycoprotein-1 are central antagonistic regulators of bone mineralization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9445–9449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142063399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murshed M, Harmey D, Millán JL, McKee MD, Karsenty G. Unique coexpression in osteoblasts of broadly expressed genes accounts for the spatial restriction of ECM mineralization to bone. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1093–1104. doi: 10.1101/gad.1276205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee NK, Sowa H, Hinoi E, Ferron M, Ahn JD, Confavreux C, Dacquin R, Mee PJ, McKee MD, Jung DY, Zhang Z, Kim JK, Mauvais-Jarvis F, Ducy P, Karsenty G. Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism by the skeleton. Cell. 2007;130:456–469. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonewald LF. The amazing osteocyte. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:229–238. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson HC. Vesicles associated with calcification in the matrix of epiphyseal cartilage. J Cell Biol. 1969;41:59–72. doi: 10.1083/jcb.41.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buchet R, Pikula S, Magne D, Mebarek S. Isolation and characteristics of matrix vesicles. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1053:115–124. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-562-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morris DC, Masuhara K, Takaoka K, Ono K, Anderson HC. Immunolocalization of alkaline phosphatase in osteoblasts and matrix vesicles of human fetal bone. Bone Miner. 1992;19:287–298. doi: 10.1016/0169-6009(92)90877-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss MJ, Cole DE, Ray K, Whyte MP, Lafferty MA, Mulivor RA, Harris H. A missense mutation in the human liver/bone/kidney alkaline phosphatase gene causing a lethal form of hypophosphatasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7666–7669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.20.7666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whyte MP. Physiological role of alkaline phosphatase explored in hypophosphatasia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1192:190–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thouverey C, Bechkoff G, Pikula S, Buchet R. Inorganic pyrophosphate as a regulator of hydroxyapatite or calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate mineral deposition by matrix vesicles. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nürnberg P, Thiele H, Chandler D, Höhne W, Cunningham ML, Ritter H, Leschik G, Uhlmann K, Mischung C, Harrop K, Goldblatt J, Borochowitz ZU, Kotzot D, Westermann F, Mundlos S, Braun HS, Laing N, Tinschert S. Heterozygous mutations in ANKH, the human ortholog of the mouse progressive ankylosis gene, result in craniometaphyseal dysplasia. Nat Genet. 2001;28:37–41. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reichenberger E, Tiziani V, Watanabe S, Park L, Ueki Y, Santanna C, Baur ST, Shiang R, Grange DK, Beighton P, Gardner J, Hamersma H, Sellars S, Ramesar R, Lidral AC, Sommer A, Raposo do Amaral CM, Gorlin RJ, Mulliken JB, Olsen BR. Autosomal dominant craniometaphyseal dysplasia is caused by mutations in the transmembrane protein ANK. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:1321–1326. doi: 10.1086/320612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pendleton A, Johnson MD, Hughes A, Gurley KA, Ho AM, Doherty M, Dixey J, Gillet P, Loeuille D, McGrath R, Reginato A, Shiang R, Wright G, Netter P, Williams C, Kingsley DM. Mutations in ANKH cause chondrocalcinosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:933–940. doi: 10.1086/343054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams CJ, Zhang Y, Timms A, Bonavita G, Caeiro F, Broxholme J, Cuthbertson J, Jones Y, Marchegiani R, Reginato A, Russell RG, Wordsworth BP, Carr AJ, Brown MA. Autosomal dominant familial calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease is caused by mutation in the transmembrane protein ANKH. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:985–991. doi: 10.1086/343053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rutsch F, Ruf N, Vaingankar S, Toliat MR, Suk A, Höhne W, Schauer G, Lehmann M, Roscioli T, Schnabel D, Epplen JT, Knisely A, Superti-Furga A, McGill J, Filippone M, Sinaiko AR, Vallance H, Hinrichs B, Smith W, Ferre M, Terkeltaub R, Nürnberg P. Mutations in ENPP1 are associated with ‘idiopathic’ infantile arterial calcification. Nat Genet. 2003;34:379–381. doi: 10.1038/ng1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruf N, Uhlenberg B, Terkeltaub R, Nürnberg P, Rutsch F. The mutational spectrum of ENPP1 as arising after the analysis of 23 unrelated patients with generalized arterial calcification of infancy (GACI) Hum Mutat. 2005;25:98. doi: 10.1002/humu.9297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moran JJ. Idiopathic arterial calcification of infancy: a clinicopathologic study. Pathol Annu. 1975;10:393–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nitschke Y, Rutsch F. Genetics in arterial calcification: lessons learned from rare diseases. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2012;22:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Magne D, Pilet P, Weiss P, Daculsi G. Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopic investigation of the maturation of nonstoichiometric apatites in mineralized tissues: a horse dentin study. Bone. 2001;29:547–552. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00609-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lusis AJ. Atherosclerosis. Nature. 2000;407:233–241. doi: 10.1038/35025203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stary HC, Chandler AB, Dinsmore RE, Fuster V, Glagov S, Insull W, Rosenfeld ME, Schwartz CJ, Wagner WD, Wissler RW. A definition of advanced types of atherosclerotic lesions and a histological classification of atherosclerosis. A report from the Committee on Vascular Lesions of the Council on Arteriosclerosis, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1995;92:1355–1374. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature. 1993;362:801–809. doi: 10.1038/362801a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mintz GS, Popma JJ, Pichard AD, Kent KM, Satler LF, Chuang YC, Ditrano CJ, Leon MB. Patterns of calcification in coronary artery disease. A statistical analysis of intravascular ultrasound and coronary angiography in 1155 lesions. Circulation. 1995;91:1959–1965. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.7.1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jeziorska M, McCollum C, Woolley DE. Calcification in atherosclerotic plaque of human carotid arteries: associations with mast cells and macrophages. J Pathol. 1998;185:10–17. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199805)185:1<10::AID-PATH71>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roijers RB, Dutta RK, Cleutjens JP, Mutsaers PH, de Goeij JJ, van der Vusse GJ. Early calcifications in human coronary arteries as determined with a proton microprobe. Anal Chem. 2008;80:55–61. doi: 10.1021/ac0706628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Doherty TM, Asotra K, Fitzpatrick LA, Qiao JH, Wilkin DJ, Detrano RC, Dunstan CR, Shah PK, Rajavashisth TB. Calcification in atherosclerosis: bone biology and chronic inflammation at the arterial crossroads. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11201–11206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932554100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang H, Virmani R, Younis H, Burke AP, Kamm RD, Lee RT. The impact of calcification on the biomechanical stability of atherosclerotic plaques. Circulation. 2001;103:1051–1056. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.8.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alexopoulos N, Raggi P. Calcification in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:681–688. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Greenland P, Bonow RO, Brundage BH, Budoff MJ, Eisenberg MJ, Grundy SM, Lauer MS, Post WS, Raggi P, Redberg RF, Rodgers GP, Shaw LJ, Taylor AJ, Weintraub WS, Harrington RA, Abrams J, Anderson JL, Bates ER, Grines CL, Hlatky MA, Lichtenberg RC, Lindner JR, Pohost GM, Schofield RS, Shubrooks SJ, Stein JH, Tracy CM, Vogel RA, Wesley DJ, Tomography ACoCFCECTFAAWCtUtECDoEBC, Prevention SoAIa and Tomography SoCC (2007) ACCF/AHA 2007 clinical expert consensus document on coronary artery calcium scoring by computed tomography in global cardiovascular risk assessment and in evaluation of patients with chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Clinical Expert Consensus Task Force (ACCF/AHA Writing Committee to Update the 2000 Expert Consensus Document on Electron Beam Computed Tomography). Circulation 115:402–426 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Tanenbaum SR, Kondos GT, Veselik KE, Prendergast MR, Brundage BH, Chomka EV. Detection of calcific deposits in coronary arteries by ultrafast computed tomography and correlation with angiography. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63:870–872. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Falk E, Shah PK, Fuster V. Coronary plaque disruption. Circulation. 1995;92:657–671. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rumberger JA, Simons DB, Fitzpatrick LA, Sheedy PF, Schwartz RS. Coronary artery calcium area by electron-beam computed tomography and coronary atherosclerotic plaque area. A histopathologic correlative study. Circulation. 1995;92:2157–2162. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.8.2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Taylor AJ, Bindeman J, Feuerstein I, Cao F, Brazaitis M, O’Malley PG. Coronary calcium independently predicts incident premature coronary heart disease over measured cardiovascular risk factors: mean three-year outcomes in the Prospective Army Coronary Calcium (PACC) project. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:807–814. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arad Y, Goodman KJ, Roth M, Newstein D, Guerci AD. Coronary calcification, coronary disease risk factors, C-reactive protein, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events: the St. Francis Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Greenland P, LaBree L, Azen SP, Doherty TM, Detrano RC. Coronary artery calcium score combined with Framingham score for risk prediction in asymptomatic individuals. JAMA. 2004;291:210–215. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kondos GT, Hoff JA, Sevrukov A, Daviglus ML, Garside DB, Devries SS, Chomka EV, Liu K. Electron-beam tomography coronary artery calcium and cardiac events: a 37-month follow-up of 5635 initially asymptomatic low- to intermediate-risk adults. Circulation. 2003;107:2571–2576. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000068341.61180.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vliegenthart R, Oudkerk M, Hofman A, Oei HH, van Dijck W, van Rooij FJ, Witteman JC. Coronary calcification improves cardiovascular risk prediction in the elderly. Circulation. 2005;112:572–577. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.488916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Greenland P, Alpert JS, Beller GA, Benjamin EJ, Budoff MJ, Fayad ZA, Foster E, Hlatky MA, Hodgson JM, Kushner FG, Lauer MS, Shaw LJ, Smith SC, Taylor AJ, Weintraub WS, Wenger NK, Jacobs AK, Anderson JL, Albert N, Buller CE, Creager MA, Ettinger SM, Guyton RA, Halperin JL, Hochman JS, Nishimura R, Ohman EM, Page RL, Stevenson WG, Tarkington LG, Yancy CW, Foundation ACoC and Association AH 2010 ACCF/AHA guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:e50–e103. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Budoff MJ, Malpeso JM. Is coronary artery calcium the key to assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults? J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2011;5:12–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vengrenyuk Y, Carlier S, Xanthos S, Cardoso L, Ganatos P, Virmani R, Einav S, Gilchrist L, Weinbaum S. A hypothesis for vulnerable plaque rupture due to stress-induced debonding around cellular microcalcifications in thin fibrous caps. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14678–14683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606310103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.New SE, Goettsch C, Aikawa M, Marchini JF, Shibasaki M, Yabusaki K, Libby P, Shanahan CM, Croce K, Aikawa E. Macrophage-derived matrix vesicles: an alternative novel mechanism for microcalcification in atherosclerotic plaques. Circ Res. 2013;113:72–77. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Maldonado N, Kelly-Arnold A, Vengrenyuk Y, Laudier D, Fallon JT, Virmani R, Cardoso L, Weinbaum S. A mechanistic analysis of the role of microcalcifications in atherosclerotic plaque stability: potential implications for plaque rupture. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303:H619–H628. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00036.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Burke AP, Taylor A, Farb A, Malcom GT, Virmani R. Coronary calcification: insights from sudden coronary death victims. Z Kardiol. 2000;89(Suppl 2):49–53. doi: 10.1007/s003920070099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ehara S, Kobayashi Y, Yoshiyama M, Shimada K, Shimada Y, Fukuda D, Nakamura Y, Yamashita H, Yamagishi H, Takeuchi K, Naruko T, Haze K, Becker AE, Yoshikawa J, Ueda M. Spotty calcification typifies the culprit plaque in patients with acute myocardial infarction: an intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2004;110:3424–3429. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148131.41425.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.New SE, Aikawa E. Molecular imaging insights into early inflammatory stages of arterial and aortic valve calcification. Circ Res. 2011;108:1381–1391. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.234146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tyson KL, Reynolds JL, McNair R, Zhang Q, Weissberg PL, Shanahan CM. Osteo/chondrocytic transcription factors and their target genes exhibit distinct patterns of expression in human arterial calcification. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:489–494. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000059406.92165.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rattazzi M, Bennett BJ, Bea F, Kirk EA, Ricks JL, Speer M, Schwartz SM, Giachelli CM, Rosenfeld ME. Calcification of advanced atherosclerotic lesions in the innominate arteries of ApoE-deficient mice: potential role of chondrocyte-like cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1420–1425. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000166600.58468.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rosenfeld ME, Polinsky P, Virmani R, Kauser K, Rubanyi G, Schwartz SM. Advanced atherosclerotic lesions in the innominate artery of the ApoE knockout mouse. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2587–2592. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.12.2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sun Y, Byon CH, Yuan K, Chen J, Mao X, Heath JM, Javed A, Zhang K, Anderson PG, Chen Y. Smooth muscle cell-specific runx2 deficiency inhibits vascular calcification. Circ Res. 2012;111:543–552. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.267237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shen J, Yang M, Jiang H, Ju D, Zheng JP, Xu Z, Liao TD, Li L. Arterial injury promotes medial chondrogenesis in Sm22 knockout mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;90:28–37. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tanimura A, McGregor DH, Anderson HC. Calcification in atherosclerosis. I. Human studies. J Exp Pathol. 1986;2:261–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schmid K, McSharry WO, Pameijer CH, Binette JP. Chemical and physicochemical studies on the mineral deposits of the human atherosclerotic aorta. Atherosclerosis. 1980;37:199–210. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(80)90005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Abdelbaky A, Corsini E, Figueroa AL, Fontanez S, Subramanian S, Ferencik M, Brady TJ, Hoffmann U, Tawakol A. Focal arterial inflammation precedes subsequent calcification in the same location: a longitudinal FDG-PET/CT study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:747–754. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Joshi NV, Vesey AT, Williams MC, Shah AS, Calvert PA, Craighead FH, Yeoh SE, Wallace W, Salter D, Fletcher AM, van Beek EJ, Flapan AD, Uren NG, Behan MW, Cruden NL, Mills NL, Fox KA, Rudd JH, Dweck MR, Newby DE. (18)F-fluoride positron emission tomography for identification of ruptured and high-risk coronary atherosclerotic plaques: a prospective clinical trial. Lancet. 2013;6736(13):61754–61757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61754-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Aikawa E, Nahrendorf M, Figueiredo JL, Swirski FK, Shtatland T, Kohler RH, Jaffer FA, Aikawa M, Weissleder R. Osteogenesis associates with inflammation in early-stage atherosclerosis evaluated by molecular imaging in vivo. Circulation. 2007;116:2841–2850. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.732867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Libby P. Inflammation and cardiovascular disease mechanisms. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:456S–460S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.456S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kleemann R, Zadelaar S, Kooistra T. Cytokines and atherosclerosis: a comprehensive review of studies in mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:360–376. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Brånén L, Hovgaard L, Nitulescu M, Bengtsson E, Nilsson J, Jovinge S. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2137–2142. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000143933.20616.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ohta H, Wada H, Niwa T, Kirii H, Iwamoto N, Fujii H, Saito K, Sekikawa K, Seishima M. Disruption of tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene diminishes the development of atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 2005;180:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lencel P, Delplace S, Pilet P, Leterme D, Miellot F, Sourice S, Caudrillier A, Hardouin P, Guicheux J, Magne D. Cell-specific effects of TNF-α and IL-1β on alkaline phosphatase: implication for syndesmophyte formation and vascular calcification. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1434–1442. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2011.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tintut Y, Patel J, Parhami F, Demer LL. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha promotes in vitro calcification of vascular cells via the cAMP pathway. Circulation. 2000;102:2636–2642. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.21.2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shioi A, Katagi M, Okuno Y, Mori K, Jono S, Koyama H, Nishizawa Y. Induction of bone-type alkaline phosphatase in human vascular smooth muscle cells: roles of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and oncostatin M derived from macrophages. Circ Res. 2002;91:9–16. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000026421.61398.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Villa-Bellosta R, Levi M, Sorribas V. Vascular smooth muscle cell calcification and SLC20 inorganic phosphate transporters: effects of PDGF, TNF-alpha, and Pi. Pflugers Arch. 2009;458:1151–1161. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0688-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee HL, Woo KM, Ryoo HM, Baek JH. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha increases alkaline phosphatase expression in vascular smooth muscle cells via MSX2 induction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:1087–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Guerrero F, Montes de Oca A, Aguilera-Tejero E, Zafra R, Rodríguez M, López I. The effect of vitamin D derivatives on vascular calcification associated with inflammation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:2206–2212. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lai CF, Shao JS, Behrmann A, Krchma K, Cheng SL, Towler DA. TNFR1-activated reactive oxidative species signals up-regulate osteogenic Msx2 programs in aortic myofibroblasts. Endocrinology. 2012;153:3897–3910. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Masuda M, Miyazaki-Anzai S, Levi M, Ting TC, Miyazaki M. PERK-eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP signaling contributes to TNFα-induced vascular calcification. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000238. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hofbauer LC, Schrader J, Niebergall U, Viereck V, Burchert A, Hörsch D, Preissner KT, Schoppet M. Interleukin-4 differentially regulates osteoprotegerin expression and induces calcification in vascular smooth muscle cells. Thromb Haemost. 2006;95:708–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ikeda K, Souma Y, Akakabe Y, Kitamura Y, Matsuo K, Shimoda Y, Ueyama T, Matoba S, Yamada H, Okigaki M, Matsubara H. Macrophages play a unique role in the plaque calcification by enhancing the osteogenic signals exerted by vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;425:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Deuell KA, Callegari A, Giachelli CM, Rosenfeld ME, Scatena M. RANKL enhances macrophage paracrine pro-calcific activity in high phosphate-treated smooth muscle cells: dependence on IL-6 and TNF-α. J Vasc Res. 2012;49:510–521. doi: 10.1159/000341216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhao G, Xu MJ, Zhao MM, Dai XY, Kong W, Wilson GM, Guan Y, Wang CY, Wang X. Activation of nuclear factor-kappa B accelerates vascular calcification by inhibiting ankylosis protein homolog expression. Kidney Int. 2012;82:34–44. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Frostegård J, Ulfgren AK, Nyberg P, Hedin U, Swedenborg J, Andersson U, Hansson GK. Cytokine expression in advanced human atherosclerotic plaques: dominance of pro-inflammatory (Th1) and macrophage-stimulating cytokines. Atherosclerosis. 1999;145:33–43. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chamberlain J, Francis S, Brookes Z, Shaw G, Graham D, Alp NJ, Dower S, Crossman DC. Interleukin-1 regulates multiple atherogenic mechanisms in response to fat feeding. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Devlin CM, Kuriakose G, Hirsch E, Tabas I. Genetic alterations of IL-1 receptor antagonist in mice affect plasma cholesterol level and foam cell lesion size. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:6280–6285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092324399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Merhi-Soussi F, Kwak BR, Magne D, Chadjichristos C, Berti M, Pelli G, James RW, Mach F, Gabay C. Interleukin-1 plays a major role in vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis in male apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:583–593. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Isoda K, Sawada S, Ishigami N, Matsuki T, Miyazaki K, Kusuhara M, Iwakura Y, Ohsuzu F. Lack of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist modulates plaque composition in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1068–1073. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000127025.48140.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Matsuki T, Isoda K, Horai R, Nakajima A, Aizawa Y, Suzuki K, Ohsuzu F, Iwakura Y. Involvement of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the development of T cell-dependent aortitis in interleukin-1 receptor antagonist-deficient mice. Circulation. 2005;112:1323–1331. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.564658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nicklin MJ, Hughes DE, Barton JL, Ure JM, Duff GW. Arterial inflammation in mice lacking the interleukin 1 receptor antagonist gene. J Exp Med. 2000;191:303–312. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.2.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, Sirois CM, Vladimer G, Bauernfeind FG, Abela GS, Franchi L, Nuñez G, Schnurr M, Espevik T, Lien E, Fitzgerald KA, Rock KL, Moore KJ, Wright SD, Hornung V, Latz E. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 2010;464:1357–1361. doi: 10.1038/nature08938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Rajamäki K, Lappalainen J, Oörni K, Välimäki E, Matikainen S, Kovanen PT, Eklund KK. Cholesterol crystals activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in human macrophages: a novel link between cholesterol metabolism and inflammation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Freigang S, Ampenberger F, Spohn G, Heer S, Shamshiev AT, Kisielow J, Hersberger M, Yamamoto M, Bachmann MF, Kopf M. Nrf2 is essential for cholesterol crystal-induced inflammasome activation and exacerbation of atherosclerosis. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:2040–2051. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Freigang S, Ampenberger F, Weiss A, Kanneganti TD, Iwakura Y, Hersberger M, Kopf M. Fatty acid-induced mitochondrial uncoupling elicits inflammasome-independent IL-1α and sterile vascular inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:1045–1053. doi: 10.1038/ni.2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wen H, Gris D, Lei Y, Jha S, Zhang L, Huang MT, Brickey WJ, Ting JP. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:408–415. doi: 10.1038/ni.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hornemann T, Worgall TS. Sphingolipids and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2013;226:16–28. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Devlin CM, Leventhal AR, Kuriakose G, Schuchman EH, Williams KJ, Tabas I. Acid sphingomyelinase promotes lipoprotein retention within early atheromata and accelerates lesion progression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1723–1730. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.173344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Marathe S, Choi Y, Leventhal AR, Tabas I. Sphingomyelinase converts lipoproteins from apolipoprotein E knockout mice into potent inducers of macrophage foam cell formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2607–2613. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.12.2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kolliputi N, Galam L, Parthasarathy PT, Tipparaju SM, Lockey RF. NALP-3 inflammasome silencing attenuates ceramide-induced transepithelial permeability. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:3310–3316. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Parhami F, Basseri B, Hwang J, Tintut Y, Demer LL. High-density lipoprotein regulates calcification of vascular cells. Circ Res. 2002;91:570–576. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000036607.05037.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kageyama A, Matsui H, Ohta M, Sambuichi K, Kawano H, Notsu T, Imada K, Yokoyama T, Kurabayashi M. Palmitic acid induces osteoblastic differentiation in vascular smooth muscle cells through ACSL3 and NF-κB, novel targets of eicosapentaenoic acid. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Brodeur MR, Bouvet C, Barrette M, Moreau P. Palmitic acid increases medial calcification by inducing oxidative stress. J Vasc Res. 2013;50:430–441. doi: 10.1159/000354235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wen C, Yang X, Yan Z, Zhao M, Yue X, Cheng X, Zheng Z, Guan K, Dou J, Xu T, Zhang Y, Song T, Wei C, Zhong H. Nalp3 inflammasome is activated and required for vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2242–2247. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bennett M, Yu H, Clarke M. Signalling from dead cells drives inflammation and vessel remodelling. Vascul Pharmacol. 2012;56:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Björkerud B, Björkerud S. Contrary effects of lightly and strongly oxidized LDL with potent promotion of growth versus apoptosis on arterial smooth muscle cells, macrophages, and fibroblasts. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:416–424. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ares MP, Pörn-Ares MI, Moses S, Thyberg J, Juntti-Berggren L, Berggren P, Hultgårdh-Nilsson A, Kallin B, Nilsson J. 7beta-hydroxycholesterol induces Ca(2+) oscillations, MAP kinase activation and apoptosis in human aortic smooth muscle cells. Atherosclerosis. 2000;153:23–35. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Schrijvers DM, De Meyer GR, Kockx MM, Herman AG, Martinet W. Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages is impaired in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1256–1261. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000166517.18801.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kono H, Rock KL. How dying cells alert the immune system to danger. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:279–289. doi: 10.1038/nri2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Proudfoot D, Skepper JN, Hegyi L, Bennett MR, Shanahan CM, Weissberg PL. Apoptosis regulates human vascular calcification in vitro: evidence for initiation of vascular calcification by apoptotic bodies. Circ Res. 2000;87:1055–1062. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.11.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Magne D, Bluteau G, Faucheux C, Palmer G, Vignes-Colombeix C, Pilet P, Rouillon T, Caverzasio J, Weiss P, Daculsi G, Guicheux J. Phosphate is a specific signal for ATDC5 chondrocyte maturation and apoptosis-associated mineralization: possible implication of apoptosis in the regulation of endochondral ossification. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1430–1442. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.8.1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ewence AE, Bootman M, Roderick HL, Skepper JN, McCarthy G, Epple M, Neumann M, Shanahan CM, Proudfoot D. Calcium phosphate crystals induce cell death in human vascular smooth muscle cells: a potential mechanism in atherosclerotic plaque destabilization. Circ Res. 2008;103:e28–e34. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.181305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Nadra I, Mason JC, Philippidis P, Florey O, Smythe CD, McCarthy GM, Landis RC, Haskard DO. Proinflammatory activation of macrophages by basic calcium phosphate crystals via protein kinase C and MAP kinase pathways: a vicious cycle of inflammation and arterial calcification? Circ Res. 2005;96:1248–1256. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000171451.88616.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Nakano-Kurimoto R, Ikeda K, Uraoka M, Nakagawa Y, Yutaka K, Koide M, Takahashi T, Matoba S, Yamada H, Okigaki M, Matsubara H. Replicative senescence of vascular smooth muscle cells enhances the calcification through initiating the osteoblastic transition. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1673–H1684. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00455.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Liu B, Wang J, Chan KM, Tjia WM, Deng W, Guan X, Huang JD, Li KM, Chau PY, Chen DJ, Pei D, Pendas AM, Cadiñanos J, López-Otín C, Tse HF, Hutchison C, Chen J, Cao Y, Cheah KS, Tryggvason K, Zhou Z. Genomic instability in laminopathy-based premature aging. Nat Med. 2005;11:780–785. doi: 10.1038/nm1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Eriksson M, Brown WT, Gordon LB, Glynn MW, Singer J, Scott L, Erdos MR, Robbins CM, Moses TY, Berglund P, Dutra A, Pak E, Durkin S, Csoka AB, Boehnke M, Glover TW, Collins FS. Recurrent de novo point mutations in lamin A cause Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Nature. 2003;423:293–298. doi: 10.1038/nature01629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Salamat M, Dhar PK, Neagu DL, Lyon JB. Aortic calcification in a patient with hutchinson-gilford progeria syndrome. Pediatr Cardiol. 2010;31:925–926. doi: 10.1007/s00246-010-9711-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]