Abstract

The choroid plexuses (CP) release numerous biologically active enzymes and neurotrophic factors, and contain a subpopulation of neural progenitor cells providing the capacity to proliferate and differentiate into other types of cells. These characteristics make CP epithelial cells (CPECs) excellent candidates for cell therapy aiming at restoring brain tissue in neurodegenerative illnesses, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD). In the present study, using in vitro approaches, we demonstrated that CP were able to diminish amyloid-β (Aβ) levels in cell cultures, reducing Aβ-induced neurotoxicity. For in vivo studies, CPECs were transplanted into the brain of the APP/PS1 murine model of AD that exhibits advanced Aβ accumulation and memory impairment. Brain examination after cell implantation revealed a significant reduction in brain Aβ deposits, hyperphosphorylation of tau, and astrocytic reactivity. Remarkably, the transplantation of CPECs was accompanied by a total behavioral recovery in APP/PS1 mice, improving spatial and non-spatial memory. These findings reinforce the neuroprotective potential of CPECs and the use of cell therapies as useful tools in AD.

Keywords: Choroid plexus, Alzheimer’s disease, Transgenic mice, Cell implants, Amyloidosis, Memory

Introduction

The accumulation of amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) is believed to be a major factor in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology. In the course of Late Onset AD (LOAD), there is no amyloid protein precursor (APP) increased synthesis but rather an Aβ decreased clearance [1]. Studying the mechanisms of Aβ clearance is, therefore, very important to understand AD. Both amyloid plaques and soluble Aβ oligomers are believed to have neurotoxic effects [2]. Delivery of neurotrophic molecules to the central nervous system (CNS) is a potential treatment strategy for preventing the neuronal loss accompanying many neurological disorders. Specifically, cell implants that deliver neurotrophic factors to the brain may be one approach for repairing the Aβ-injured brain, as validated in numerous laboratory studies [3–6]. Initial clinical trials of cell transplantation therapy for AD have also been developed [7–9]. One interesting source of transplantable cells is choroid plexuses (CP), which produce and secrete a wide range of neurotrophins and other cell survival factors [10, 11], and thus might provide a novel way of delivering potentially therapeutic factors for AD. Interestingly, in LOAD, CP-significant changes are numerous: epithelial atrophy, fibrosis, and thickened basement membranes suggesting an alteration of several functions. Additionally, CP have been reported to produce several key enzymes involved in Aβ production, metabolism, and alternate processing, such as insulin degrading enzyme, endothelin-converting enzyme-1, neprilysin, and alpha-secretase [12]. In this regard, several studies point to neprilysin as one of the prominent Aβ-degrading proteases within the brain [4, 13, 14]. The role of Aβ degradation in the clearance of Aβ peptide is becoming more broadly understood and appreciated. Thus, CP could support a dual therapeutic function for AD treatment.

In the last decade, several studies involving CP transplants in experimental models of lesions have been shown to produce a robust regeneration and neuroprotection proximal to the grafted tissue [15–18]. Moreover, very recently, we have revealed the neurogenic capacity of CP and their implication in AD [19]. In the present work, we propose a novel way for potential release of therapeutic factors using CP epithelial cells (CPECs) transplanted into the brains of APP/PS1 transgenic mice. As proof-of-concept, we tested this technology as a therapeutic approach for the treatment of AD using an in vitro model, showing the ability to reduce Aβ-induced neuronal death. Transplantation of CPEC in vivo reduced Aβ-like pathology in APP/PS1 transgenic mice, and resulted in significant behavioral recovery of memory.

Materials and methods

Cell cultures

CP epithelial cell cultures were prepared as described previously [20]. CP were dissected from 3- to 5-day-old Wistar rats (Charles River) for in vitro assays, or C57BL6 mice (Charles River) for in vivo implants. Briefly, CP from the fourth ventricle and lateral ventricles were rapidly dissected and then enzymatically digested with 1 mg/ml pronase (Sigma) and 12.5 μg/ml DNase I (Boehringer, Mannheim) for 20 min at 37 °C. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 1,000 rpm for 5 min, and the pellets were resuspended in culture media. Rat CPEC were seeded on two-chamber culture wells, using a Transwell® system (0.4 μm pore size, HD; Millipore), previously coated with 10 μg/ml laminin (Sigma), with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Lonza) containing 10 % fetal bovine serum (Lonza), 2 mM glutamine (Sigma), 100 U/ml penicillin (Lonza), and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Lonza). Rat and mouse CPEC were also characterized by immunocytochemistry assays using antibodies anti-pancytokeratin as epithelial cell marker [21]. Barrier properties of the monolayer were determined by its electrical resistance and permeability characteristics as described [20].

Primary neuronal cultures from the cerebral cortex were performed as previously described [22] from Wistar rat embryos (Charles River) on prenatal day 17. Three experimental models were established depending on the type of cells and medium used: (1) protocol A: cultures were grown in Neurobasal® medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and kept at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO2 for 7 days prior to experimentation; (2) protocol B: cortical neuronal cultures grown in CP conditioned medium; and (3) protocol C: cortical neuronal cultures were co-cultured with CPEC in a Transwell® system (Millipore) to investigate the influence of CPECs on neuronal viability. In all experiments, primary neurons were grown on coated plates with 10 μg/ml poly-lysine (Sigma). Then, cells were serum-starved for 2 h and 10 μM Aβ1–42 (AnaSpec) was added to the culture for 48 h to study Aβ-induced neurotoxicity. Cells were either fixed for immunocytochemical assay or homogenized for immunoblot determination.

SK-N-MC cells, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (HTB10), were cultured in modified Eagle’s medium, supplemented with 10 % fetal calf serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 0.01 % sodium piruvate (Lonza), and 50 μg/ml gentamicin (Lonza). SK-N-MC cells stably expressing the human isoform APP695 (SK-APP cell line D1; SK-APP-D1) were generated by transfection of SK-N-MC cells with a pCDNA3-APP expression vector, kindly provided by the Mayo Clinic. Briefly, a pellet of 4 × 106 cells was resuspended in 100 μl of Nucleofector® solution V (Lonza), mixed with 15 μg of pCDNA3-APP plasmid, and subjected to nucleofection. Following the electroporation, the cells were seeded into the growth medium supplemented with the selection antibiotic geneticin (Gibco). SK-APP-D1 cell line was co-cultured with CPEC on two-chamber culture wells, according to protocol C, to investigate the influence of CPECs on the regulation of Aβ levels. 10 μM Phosphoramidon (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added to the co-cultures to inhibit neprilysin enzymatic activity [4]. 24 and 48 h later, cell were lysed, and conditioned medium was collected, centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 5 min to remove suspended cells, tenfold concentrated in presence of protease inhibitors cocktail, and stored at -80 °C.

Animals and experimental design

Male 9-month-old APP/PS1 mice, B6.Cg-Tg (APPSwe, PSEN1dE9)/J, (Jackson Laboratory) were used as a model of AD amyloidosis. Age-matched non-transgenic male littermates were used as controls. For surgical procedures, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and received a bilateral hippocampal injection of 1 × 106 mouse CPEC collected in buffer saline. The stereotaxic coordinates for graft placement were calculated from bregma: −3.3 posterior, −2 lateral, and 3.5 ventral. Cells, in a volume of 5 μl (10 μl per mouse), were injected at 1 μl/min with a 10-μl syringe (Hamilton). Control mice were stereotaxically injected with buffer saline vehicle. Animals were sacrificed 4 weeks after the injections, deeply anesthetized with isoflurane, and transcardially perfused either with saline for biochemical analysis, or 4 % paraformaldehyde (Sigma) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4 for immunohistochemical analysis. All animals were handled and cared for according to the Council Directive 2010/63/UE of 22 September 2010.

Behavioral testing was performed in APP/PS1 mice transfected with CPEC or vehicle, and their wild-type littermates. After adaptation to human handling, APP/PS1 mice were tested for memory and exploration behavior in the T-maze, and the novel object recognition test (ORT), as previously described [6]. In the T-maze, a behavioral test of spatial memory, the number of alternations and errors (entries to previously visited arms), and the time to complete each session were recorded. In the ORT, the recognition index, defined as the ratio of the time spent exploring the novel object over the time spent exploring both objects, was used to measure non-spatial memory.

Immunoassays

Western blot (WB) assay was performed as described previously [20]. Briefly, cells and tissue were homogenized in 50 mM Tris–HCl (ph 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 % NP-40 and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Then, total proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (Biorad) and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Biorad). Primary antibodies used included: rabbit anti-neprilysin (1:500; Millipore), mouse anti-GFAP (as astrocyte marker, 1:1,000; Sigma), mouse anti-Aβ (1:1,000, MBL; Nagoya, Japan), rabbit anti-APP (1:1,000; Sigma), mouse anti-Hpf-tau (1:1,000, AT-8; Innogenetics), mouse anti-GSK3β (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-pSer-GSK3β (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology), and mouse anti-β-actin (1:20,000; Sigma). Secondary HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse and donkey anti-rabbit antibodies were used (1:20,000; Bio-Rad). DAPI (1:10,000; Sigma) was used to stain nuclei. Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ software (NIH). Levels of Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 were quantified by sandwich ELISAs (Wako, Osaka, Japan) from cellular lysates and conditioned media collected. Cell death quantification of neurons was detected with a Cell Death Detection ELISAPLUS kit (Roche Applied Science).

For immunocytochemistry, cells were fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PB (pH 7.4), and incubated overnight at 4 °C with mouse anti-β-III-tubulin (as neuronal marker, 1:1,000; Promega). After incubation with donkey anti-mouse IgG 488 (1:1,000; FluoProbes), β-III-tubulin+ cells were counted under the ×20 objective using a fluorescent Nikon microscope.

Fixed brains were cut on a vibratome (Leica) at 40 μm, collected in cold PB 0.1 M, and incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4 °C. The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-Aβ (1:500, MBL), mouse anti-GFAP (1:500; Sigma), and mouse anti-pancytokeratin (as CPEC marker, 1:500; Sigma). Primary antibody staining was revealed using the avidin–biotin complex method (VECTASTAIN Elite ABC Kit; Vector Laboratories) and DAB chromogenic reaction (Vector Laboratories), or fluorescence-conjugated anti-mouse IgG 488 (1:1,000; FluoProbes). To detect Aβ deposits, brain sections from APP/PS1 mice were pre-incubated with 88 % formic acid. Aβ+ area was analyzed stereologically, as described previously [20], and plaque burden was expressed as percentage of brain area stained with Aβ. Pictures were taken using light microscopy (Zeiss microscope) at a magnification of ×20, and semiquantitative analysis of the labeled signal was performed using NIH Image J software.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analyses were performed using a two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Comparisons between two groups were done with Student’s t test. All calculations were made using SPSS v.15.0 software. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Effects of CPEC in Aβ-induced neurotoxicity

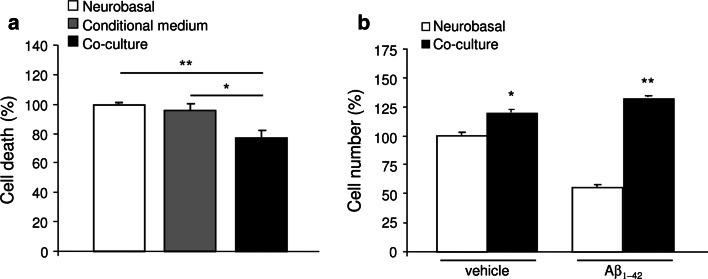

A significant reduction in cell death was observed in the co-culture system (p < 0.05 vs. conditioned medium, and p < 0.01 vs. Neurobasal medium; Fig. 1a) 48 h after cultured neurons were exposed to the three experimental protocols. Counting the number of neuronal β-III-tubulin+ cells in the culture corroborated this finding, indicating that using the co-culture system increases the neuronal cell percentage (p < 0.05; Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Neuronal survival and proliferation by CPEC cultures. a Reduced cell death was observed in primary neuronal cells co-cultured with CPEC measured by ELISA. b Number of neuronal β-III-tubulin+ cells was increased in both treated with vehicle (left histogram), and treated with 10 μM Aβ1–42 (right histogram) neuronal cultures co-cultured with CPEC. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. n = 3 independent experiments

We next determined whether the transplanted CP cells were able to prevent Aβ-induced neurotoxicity. When Aβ1–42 was added in the co-culture system, the reduction of neuron number mediated by Aβ in Neurobasal medium was abolished, resulting in an increase of the number of neuronal cells (p < 0.05; Fig. 1b).

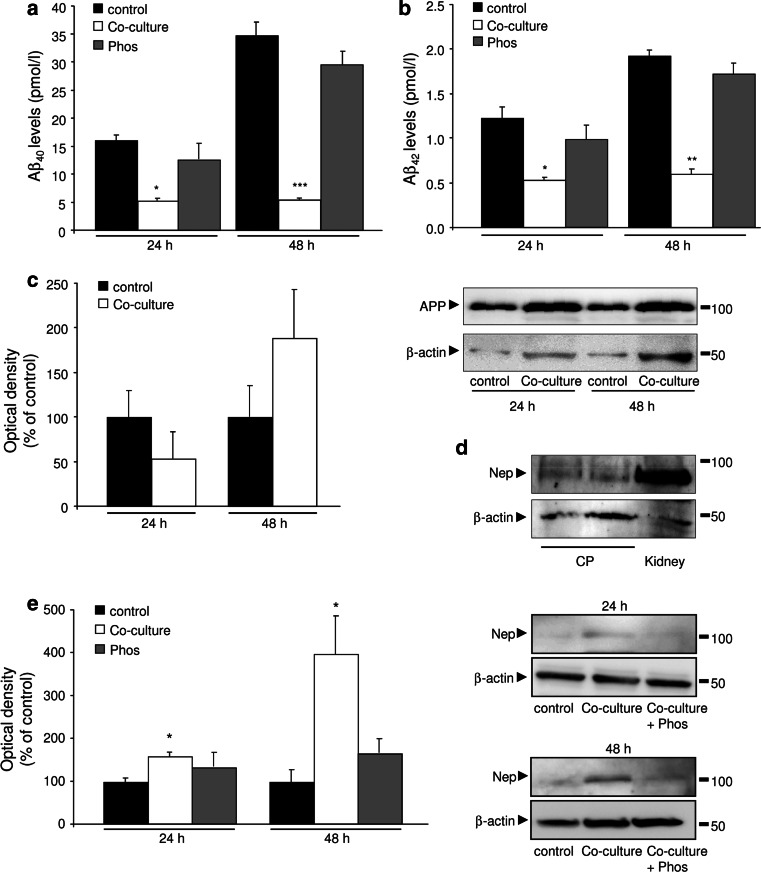

Then, we evaluated if CPEC could also have a role in the regulation of Aβ levels, using an in vitro culture system. Thus, we co-cultured SK-N-MC neuroblastoma cells and stably expressing APP (SK-APP-D1 cells) with CPEC. Cells were allowed to grow to confluence, and media were collected for Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 ELISA determinations. SK-APP-D1 showed an increase in the Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 secreted levels in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2a, b). When SK-APP-D1 cells were co-cultured with CPEC, Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 levels were drastically diminished in the media: a 65 % (p < 0.01; Fig. 2a), and 85 % (p < 0.001; Fig. 2a) reduction in Aβ1–40, and a 57 % (p < 0.05; Fig. 2b), and 68 % (p < 0.001; Fig. 2b) reduction in Aβ1–42, at 24 and 48 h after cell seeding, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Clearance of Aβ peptides by CPEC cultures. a, b SK-APP-D1 cells were co-cultured with CPEC, and conditioned media were analyzed for Aβ1–40 (a), and Aβ1–42 (b) levels by ELISA. c SK-APP-D1 cellular lysates from the co-culture experiments were probed by WB for APP. d Neprilysin WB of cellular lysates from CPEC. Kidney tissue was used as positive control. e Neprilysin expression measured by WB was increased in SK-APP-D1 cells co-cultured with CPEC, and inhibited by phosphoramidon. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. CP choroid plexus, Nep neprilysin, Phos phosphoramidon. n = 3 independent experiments

To investigate the mechanism by which CPEC decrease Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 levels, we examined the APP expression in SK-APP-D1 cells. We found no significant differences in APP expression in SK-APP-D1 cells, after co-culture with CPEC (Fig. 2c). Whereas Aβ1–40 levels were undetected in SK-APP-D1 cellular lysates, no changes were observed in Aβ1–42 expression at 24 and 48 h after co-culture with CPEC (data not shown). In order to clarify the possible mechanism involved in the reduction of Aβ levels, we investigated the expression of neprilysin. Firstly, we confirmed neprilysin expression in the CPEC (Fig. 2d). Then, we found a neprilysin overexpression in SK-APP-D1 cells 48 h after co-culture with CPEC, and this was inhibited by phosphoramidon, a neprilysin inhibitor (Fig. 2e). Phosphoramidon was also able to block the CPEC-induced reduction in the levels of Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 secreted from SK-APP-D1 co-cultured cells (Fig. 2a, b). Taken together, these data suggest that CPEC provoke a reduction in Aβ levels mainly enhancing its neprilysin-induced extracellular Aβ degradation.

Effects of CPEC transplantation in APP/PS1 mice

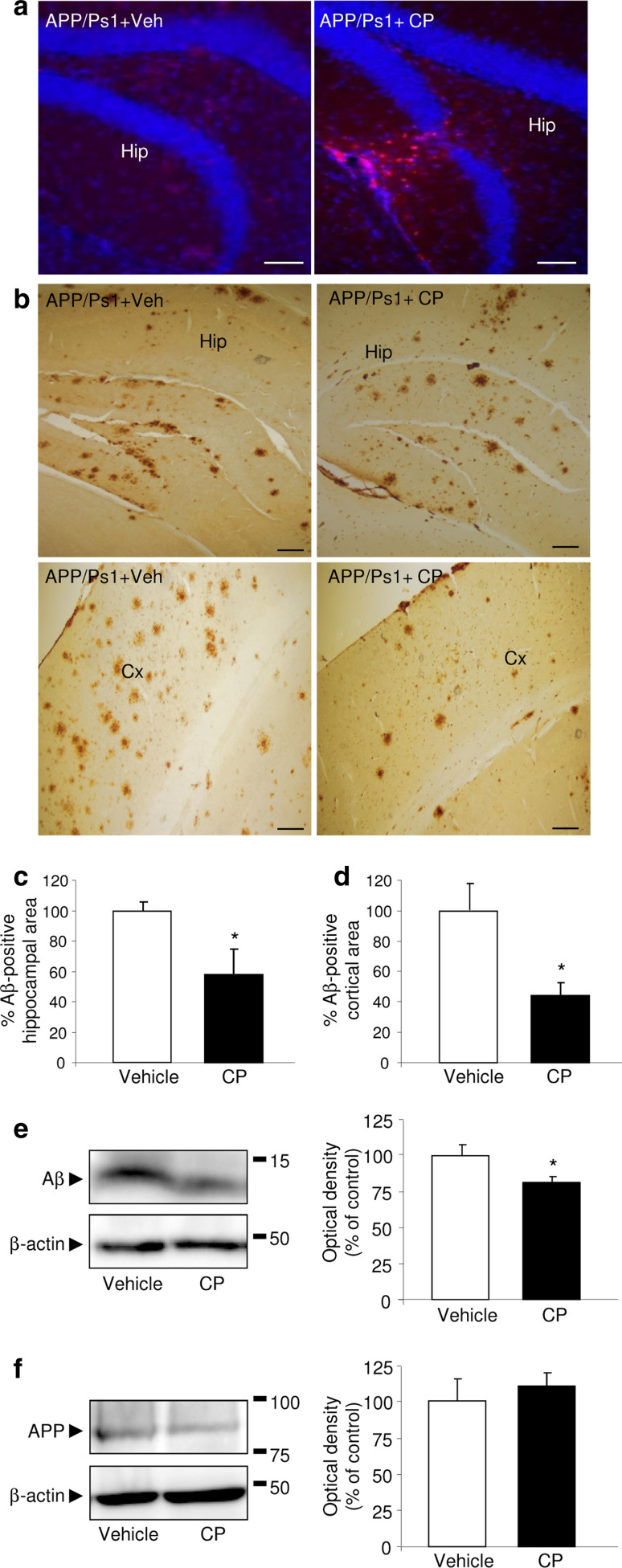

One month after CPEC transplantation, APP/PS1 mice exhibited pancytokeratin immunoreactivity at the graft site, consistent with the presence of CPEC (Fig. 3a). Next, we observed that engraftment of CPEC significantly attenuated Aβ accumulation in both the cerebral frontal cortex and hippocampus (Fig. 3b). Stereological analysis revealed a significant decrease in the percentage of Aβ+ plaque compared with the vehicle-treated APP/PS1 mice (p < 0.05, Fig. 3c, d).

Fig. 3.

Reduction in Aβ accumulation after CPEC transplantation. a Grafted CPEC were immunoreactive for pancytokeratin (red) in the hippocampus (Hip). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar 20 μm. b Representative images show Aβ deposits in the hippocampus (Hip, upper panels) and cerebral frontal cortex (Cx, bottom panel) in APP/PS1 mice engrafted with CPEC. Scale bar 20 μm. c, d Stereological quantification of Aβ burden in hippocampus (c) and cerebral cortex (d) from APP/PS1 mice engrafted with CPEC or vehicle is shown. e, f Representative WB and quantitative analysis showing a decrease in Aβ expression (e), whereas APP levels (f) remained unchanged in hippocampal lysates of APP/PS1 mice after CPEC transplantation. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, n = 8 mice per group. Veh vehicle, CP choroid plexus

We also used WB to determine Aβ levels in the hippocampus of APP/PS1 mice. After CPEC implantation, hippocampal Aβ levels were reduced compared to those seen in vehicle-treated APP/PS1 mice (p < 0.05; Fig. 3e). In contrast, we did not observe any difference in APP expression in the hippocampal region between the two groups (Fig. 3f).

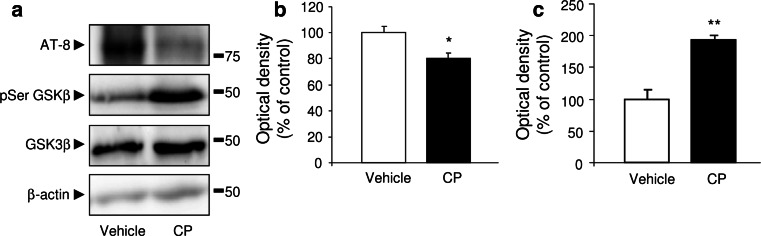

Given the beneficial role of CPEC engraftment in Aβ accumulation, we attempted to determine a possible role of these cell implants in tau hyperphosphorylation in APP/PS1 mice. Hpf-tau levels were significantly reduced in the hippocampus in APP/PS1 mice after CPEC implantations (p < 0.05; Fig. 4a, b), associated with a marked increase in the phosphorylated GSK3β (Ser9), the inactive form (p < 0.01; Fig. 4a, c).

Fig. 4.

Reduction in phosphorylation of Tau after CPEC transplantation. a Hpf-tau levels were reduced, and pSer-GSK3β expression was increased in hippocampus of APP/PS1 mice engrafted with CPEC. b, c Densitometry histograms confirmed these data related to Hpf-tau (b), and pSer-GSK3β (c) expression. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 8 mice per group. Veh vehicle, CP choroid plexus

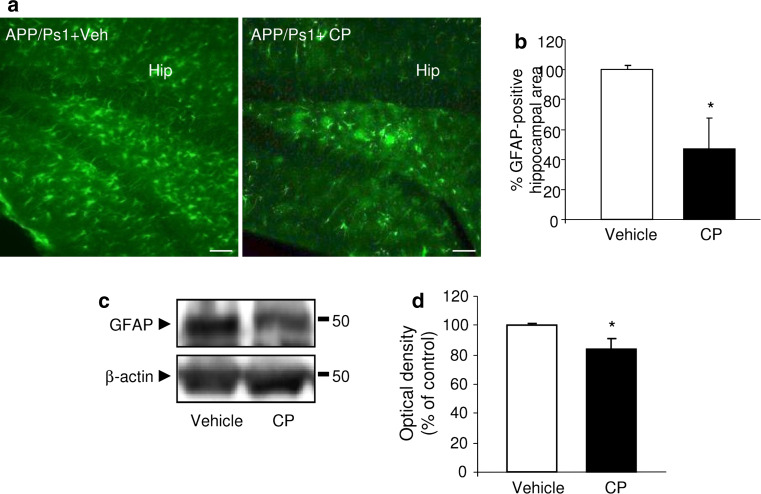

To determine if the engrafted CPEC were able to reduce astrocytosis, we investigated astrocyte GFAP labeling. We observed a reduction in GFAP immunostaining in the hippocampal area, corresponding with the site of cell implantation (Fig. 5a). These results were confirmed by stereological analysis of GFAP immunoreactivity, which showed a 50 % decrease in the astrocytic volume in APP/PS1 mice after CPEC engraftment (p < 0.05; Fig. 5b). The change in the astrocytic reactivity was also confirmed by WB analysis of GFAP (Fig. 5c). A marked reduction in GFAP expression was observed in the hippocampus of APP/PS1 mice when measured at 4 weeks postimplantation (p < 0.05; Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5.

Reduction in astrocytic reactivity in APP/Ps1 mice after CPEC transplantation. a Fluorescent GFAP signal showed fewer activated astrocytes in the hippocampus (Hip) of APP/PS1 mice following CPEC transplantation than in vehicle-treated control group. Scale bar 20 μm. b Quantification of GFAP volume in the hippocampus confirmed this CPEC transplantation effect. c, d Representative WB of GFAP expression (c) in hippocampal lysates of APP/PS1 mice, and densitometric quantification of the GFAP protein levels (d) of APP/PS1 mice after CPEC transplantation. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, n = 8 mice per group. Veh vehicle, CP choroid plexus

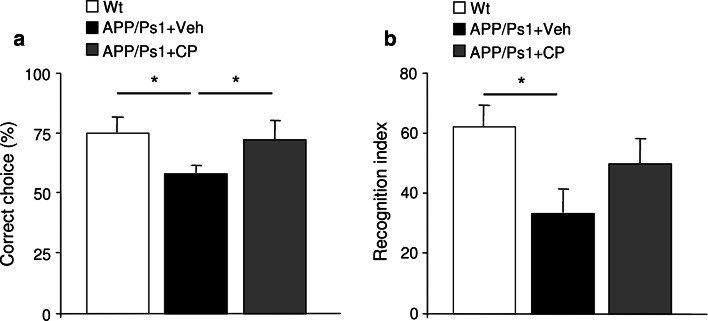

The APP/PS1 murine model of AD is well known to develop Aβ-associated cognitive deterioration with increasing age [23]. We examined the impact of choroid plexus epithelial cell grafting on cognitive functions using the T-maze and ORT to test spatial and non-spatial memory functions, respectively. Four weeks after treatment, spontaneous alternations from CPEC implanted, vehicle-treated, and control animals were quantified from T-maze analyses. CPEC-implanted APP/PS1 mice demonstrated improved cognitive performance represented by a significant increase in spontaneous alternations compared to vehicle-treated mice (p < 0.05; Fig. 6a). In the ORT, APP/PS1 mice spent significantly less time with the novel object compared to non-transgenic mice (p < 0.05; Fig. 6b), whereas in CPEC-implanted-APP/PS1 mice, retention was recovered (Fig. 4b), indicating a better performance in their memory process.

Fig. 6.

Behavioral cognition in APP/Ps1 mice after CPEC transplantation. a Spontaneous alternation, measured as correct choice, was restored in APP/PS1 mice after CPEC transplantation. b In the novel-object recognition test, APP/PS1 mice showed a significant decline in performance. In APP/PS1 mice engrafted with CPEC, the ratio exploring the novel object was enhanced. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, n = 8 mice per group. WT wild-type, Veh vehicle, CP choroid plexus

Discussion

In this study, we described in vivo and in vitro neuroprotective effects of CPEC implants as a viable and therapeutic approach in AD. When CPEC were engrafted into APP/PS1 transgenic mice, a significant reduction in Aβ accumulation was observed surrounding the graft site in the hippocampus, as well as distal to the graft, in the cerebral cortex. Prominent AD neuropathological features, including tau hyperphosphorylation and astrogliosis, were also reduced. Finally, CPEC-implanted APP/PS1 mice showed an improvement in memory when compared with the vehicle-treated APP/PS1 mice.

Previous studies have demonstrated that CPEC can release numerous enzymes and biologically active neurotrophic factors known to decreased brain Aβ accumulation [4, 6, 24], some of which are down-regulated in AD [6, 20, 25, 26]. Enzymatic degradation is thought to play an integral role in the removal of Aβ, and CP play a crucial role in this process by producing several Aβ-degrading enzymes [12]. In view of our data, we suggest that CP provoked an important reduction of Aβ-induced neurotoxicity, associated with diminished Aβ presence in the medium. These decreased Aβ levels could be the consequence of a reduction in Aβ secretion from APP processing, and an enhanced Aβ degradation. Aβ clearance can also occur via transcytosis across CP removing Aβ from the medium, reinforcing the crucial role of CP in the development of AD pathology. In addition, we cannot exclude the presence of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters in the CP, participating in the elimination of endogenous metabolites [27–30]. APP processing can be modulated by different mechanisms, including but not limited to an altered APP expression. In vitro, we found that intracellular APP and Aβ1–42 expression were unchanged, whereas Aβ1–40 levels were undetected, suggesting that CPEC were mainly modulating Aβ degradation as opposed to its production. Unaltered APP expression was also confirmed in CPEC-implanted APP/PS1 mice. Although the regulatory mechanisms mediating neprilysin activity in the brain remain unclear, here we found that co-culture with CPEC resulted in elevated neprilysin levels in SK-APP-D1 cells, improving the degradation of Aβ on the cell surface, according with the role of this transmembrane protein [31]. In view of our findings, we suggest that CPEC upregulated neprilysin-mediated degradation of Aβ extracellular on the cell surface. Additionally, neprilysin from CPEC may be contributing to degrade extracellular Aβ peptides. As a result, CPEC-transplanted APP/PS1 mice display a significant reduction in plaque burden. Given the central role of Aβ in tau hyperphosphorylation [32–34] and astrocyte activation [35, 36] in AD, the significant decrease in these hallmarks seen in CPEC-implanted APP/PS1 mice can be attributed to its inhibition of Aβ accumulation. Removal of Aβ deposits has been extensively explored in transgenic AD models, and development of treatments has focused on increasing Aβ clearance [20, 37, 38]. However, immunization strategies in AD patients reduce amyloid brain levels, but no major therapeutic benefits have been observed. CP also represent a multifactorial option based on the ability to produce a nutritive ‘‘cocktail’’ of neurotrophic factors [10]. Indeed, CP appear to possess an inherent anti-inflammatory function independent of Aβ [39]. By demonstrating that CPEC transplantation efficiently reverses Aβ-induced neuropathology, this study brings new insights into the physiological role of CP in brain function, and the development of new cell-based therapeutic strategies to promote neuroprotection in AD. However, further studies will be necessary to identify the pharmacological basis of the neuroprotective effects achieved by CPEC transplantation.

Our behavioral experiments demonstrated that spatial and non-spatial memory was severely impaired in APP/PS1, and was restored after the transplantation of CPEC. As reported, excessive Aβ accumulation is associated with disturbed cognitive function in the AD mouse model [40]. The beneficial effect of CPEC implantation on cognitive improvement in APP/PS1 mice is likely attributable to the combined effects of decreased toxic Aβ levels, Hpf-tau, and astrocytic inflammation. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that this cell-mediated therapy improves the learning and memory in an alternative manner, because very recently we have demonstrated that CPEC possess cell proliferation and differentiation capabilities [19], and Itokazu et al. [41] has shown that neural progenitor cells exist among CPEC in the rat.

In the last decade, neuroprotection induced by growth factors in AD has been extensively studied [6, 20, 42, 43]. Most of these reports, however, have been focused on the use of a single recombinant growth factor, an approach that might be insufficient due to the fact that the impaired function of growth factor observed in AD may affect an important number of them. One interesting alternative, which avoids systemic side effects, involves the use of cell therapy using primary cells which do not represent a significant tumorigenicity risk. We report here that CPEC implantation may act as a neuroprotective agent in AD. We have established a novel therapeutic strategy based on cell-based delivery of growth factors and cell replacement therapy. The present study offers evidence that CPEC are able to degrade Aβ, providing a cell therapy-mediated technology to attenuate Aβ-associated neuropathology and memory deficits in the APP/PS1 transgenic AD mouse model.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (FIS 09-01636), Fundación Investigación Médica Mutua Madrileña (2008/93; 2010/0004), Fundación Ramón Areces, Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (SAF2010-15558), and CIBERNED (BESAD-P.2010). We thank Isabel Sastre for technical assistance, and Agnieszka Krzyzanowska, PhD, for the careful revision of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Mawuenyega KG, Sigurdson W, Ovod V, Munsell L, Kasten T, et al. Decreased clearance of CNS beta-amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2010;330:1774. doi: 10.1126/science.1197623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, et al. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416:535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emerich DF, Winn SR, Hantraye PM, Peschanski M, Chen EY, et al. Protective effect of encapsulated cells producing neurotrophic factor CNTF in a monkey model of Huntington’s disease. Nature. 1997;386:395–399. doi: 10.1038/386395a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hemming ML, Patterson M, Reske-Nielsen C, Lin L, Isacson O, et al. Reducing amyloid plaque burden via ex vivo gene delivery of an Abeta-degrading protease: a novel therapeutic approach to Alzheimer disease. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia P, Youssef I, Utvik JK, Florent-Bechard S, Barthelemy V, et al. Ciliary neurotrophic factor cell-based delivery prevents synaptic impairment and improves memory in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7516–7527. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4182-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spuch C, Antequera D, Portero A, Orive G, Hernandez RM, et al. The effect of encapsulated VEGF-secreting cells on brain amyloid load and behavioral impairment in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Biomaterials. 2010;31:5608–5618. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuszynski MH, Thal L, Pay M, Salmon DP, U HS, et al. A phase 1 clinical trial of nerve growth factor gene therapy for Alzheimer disease. Nat Med. 2005;11:551–555. doi: 10.1038/nm1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eriksdotter-Jonhagen M, Linderoth B, Lind G, Aladellie L, Almkvist O, et al. Encapsulated cell biodelivery of nerve growth factor to the Basal forebrain in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2012;33:18–28. doi: 10.1159/000336051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wahlberg LU, Lind G, Almqvist PM, Kusk P, Tornoe J, et al. Targeted delivery of nerve growth factor via encapsulated cell biodelivery in Alzheimer disease: a technology platform for restorative neurosurgery. J Neurosurg. 2012;117:340–347. doi: 10.3171/2012.2.JNS11714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stopa EG, Berzin TM, Kim S, Song P, Kuo-LeBlanc V, et al. Human choroid plexus growth factors: what are the implications for CSF dynamics in Alzheimer’s disease? Exp Neurol. 2001;167:40–47. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alvira-Botero X, Carro EM. Clearance of amyloid-beta peptide across the choroid plexus in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Aging Sci. 2010;3:219–229. doi: 10.2174/1874609811003030219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crossgrove JS, Smith EL, Zheng W. Macromolecules involved in production and metabolism of beta-amyloid at the brain barriers. Brain Res. 2007;1138:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwata N, Tsubuki S, Takaki Y, Shirotani K, Lu B, et al. Metabolic regulation of brain Abeta by neprilysin. Science. 2001;292:1550–1552. doi: 10.1126/science.1059946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leissring MA, Farris W, Chang AY, Walsh DM, Wu X, et al. Enhanced proteolysis of beta-amyloid in APP transgenic mice prevents plaque formation, secondary pathology, and premature death. Neuron. 2003;40:1087–1093. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00787-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borlongan CV, Thanos CG, Skinner SJ, Geaney M, Emerich DF. Transplants of encapsulated rat choroid plexus cells exert neuroprotection in a rodent model of Huntington’s disease. Cell Transpl. 2008;16:987–992. doi: 10.3727/000000007783472426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emerich DF, Thanos CG, Goddard M, Skinner SJ, Geany MS, et al. Extensive neuroprotection by choroid plexus transplants in excitotoxin lesioned monkeys. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;23:471–480. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borlongan CV, Skinner SJ, Geaney M, Vasconcellos AV, Elliott RB, et al. Intracerebral transplantation of porcine choroid plexus provides structural and functional neuroprotection in a rodent model of stroke. Stroke. 2004;35:2206–2210. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000138954.25825.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wise AK, Fallon JB, Neil AJ, Pettingill LN, Geaney MS, et al. Combining cell-based therapies and neural prostheses to promote neural survival. Neurotherapeutics. 2011;8:774–787. doi: 10.1007/s13311-011-0070-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolos M, Spuch C, Ordonez-Gutierrez L, Wandosell F, Ferrer I, et al. Neurogenic effects of beta-amyloid in the choroid plexus epithelial cells in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:10. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1300-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carro E, Trejo JL, Gomez-Isla T, LeRoith D, Torres-Aleman I. Serum insulin-like growth factor I regulates brain amyloid-beta levels. Nat Med. 2002;8:1390–1397. doi: 10.1038/nm1202-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartek J, Bartkova J, Kyprianou N, Lalani EN, Staskova Z, et al. Efficient immortalization of luminal epithelial cells from human mammary gland by introduction of simian virus 40 large tumor antigen with a recombinant retrovirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3520–3524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alvira-Botero X, Perez-Gonzalez R, Spuch C, Vargas T, Antequera D, et al. Megalin interacts with APP and the intracellular adapter protein FE65 in neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2010;45:306–315. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trinchese F, Liu S, Battaglia F, Walter S, Mathews PM, et al. Progressive age-related development of Alzheimer-like pathology in APP/PS1 mice. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:801–814. doi: 10.1002/ana.20101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antequera D, Vargas T, Ugalde C, Spuch C, Molina JA, et al. Cytoplasmic gelsolin increases mitochondrial activity and reduces Abeta burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;36:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emerich DF, Schneider P, Bintz B, Hudak J, Thanos CG. Aging reduces the neuroprotective capacity, VEGF secretion, and metabolic activity of rat choroid plexus epithelial cells. Cell Transplant. 2007;16:697–705. doi: 10.3727/000000007783465145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vargas T, Ugalde C, Spuch C, Antequera D, Moran MJ, et al. Abeta accumulation in choroid plexus is associated with mitochondrial-induced apoptosis. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:1569–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghersi-Egea JF, Strazielle N. Choroid plexus transporters for drugs and other xenobiotics. J Drug Target. 2002;10:353–357. doi: 10.1080/10611860290031859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Lange EC. Potential role of ABC transporters as a detoxification system at the blood-CSF barrier. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56:1793–1809. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhongsatiern J, Ohtsuki S, Tachikawa M, Hori S, Terasaki T. Retinal-specific ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABCR/ABCA4) is expressed at the choroid plexus in rat brain. J Neurochem. 2005;92:1277–1280. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujiyoshi M, Ohtsuki S, Hori S, Tachikawa M, Terasaki T. 24S-hydroxycholesterol induces cholesterol release from choroid plexus epithelial cells in an apical- and apoE isoform-dependent manner concomitantly with the induction of ABCA1 and ABCG1 expression. J Neurochem. 2007;100:968–978. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hama E, Shirotani K, Iwata N, Saido TC. Effects of neprilysin chimeric proteins targeted to subcellular compartments on amyloid beta peptide clearance in primary neurons. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30259–30264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401891200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilcock DM, Gharkholonarehe N, Van Nostrand WE, Davis J, Vitek MP, et al. Amyloid reduction by amyloid-beta vaccination also reduces mouse tau pathology and protects from neuron loss in two mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2009;29:7957–7965. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1339-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang HC, Jiang ZF. Accumulated amyloid-beta peptide and hyperphosphorylated tau protein: relationship and links in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16:15–27. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rebeck GW, Hoe HS, Moussa CE. Beta-amyloid1-42 gene transfer model exhibits intraneuronal amyloid, gliosis, tau phosphorylation, and neuronal loss. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7440–7446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.083915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuoka Y, Picciano M, Malester B, LaFrancois J, Zehr C, et al. Inflammatory responses to amyloidosis in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1345–1354. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64085-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rozemuller AJ, van Gool WA, Eikelenboom P. The neuroinflammatory response in plaques and amyloid angiopathy in Alzheimer’s disease: therapeutic implications. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2005;4:223–233. doi: 10.2174/1568007054038229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schenk D, Barbour R, Dunn W, Gordon G, Grajeda H, et al. Immunization with amyloid-beta attenuates Alzheimer-disease-like pathology in the PDAPP mouse. Nature. 1999;400:173–177. doi: 10.1038/22124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gasparini L, Gouras GK, Wang R, Gross RS, Beal MF, et al. Stimulation of beta-amyloid precursor protein trafficking by insulin reduces intraneuronal beta-amyloid and requires mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2561–2570. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02561.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsumoto N, Taguchi A, Kitayama H, Watanabe Y, Ohta M, et al. Transplantation of cultured choroid plexus epithelial cells via cerebrospinal fluid shows prominent neuroprotective effects against acute ischemic brain injury in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 2010;469:283–288. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen G, Chen KS, Knox J, Inglis J, Bernard A, et al. A learning deficit related to age and beta-amyloid plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2000;408:975–979. doi: 10.1038/35046031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Itokazu Y, Kitada M, Dezawa M, Mizoguchi A, Matsumoto N, et al. Choroid plexus ependymal cells host neural progenitor cells in the rat. Glia. 2006;53:32–42. doi: 10.1002/glia.20255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Capsoni S, Giannotta S, Cattaneo A. Nerve growth factor and galantamine ameliorate early signs of neurodegeneration in anti-nerve growth factor mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12432–12437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192442999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nagahara AH, Merrill DA, Coppola G, Tsukada S, Schroeder BE, et al. Neuroprotective effects of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in rodent and primate models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 2009;15:331–337. doi: 10.1038/nm.1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]