Abstract

β-amyloid (Aβ) can promote neurogenesis, both in vitro and in vivo, by inducing neural progenitor cells to differentiate into neurons. The choroid plexus in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is burdened with amyloid deposits and hosts neuronal progenitor cells. However, neurogenesis in this brain tissue is not firmly established. To investigate this issue further, we examined the effect of Aβ on the neuronal differentiation of choroid plexus epithelial cells in several experimental models of AD. Here we show that Aβ regulates neurogenesis in vitro in cultured choroid plexus epithelial cells as well as in vivo in the choroid plexus of APP/Ps1 mice. Treatment with oligomeric Aβ increased proliferation and differentiation of neuronal progenitor cells in cultured choroid plexus epithelial cells, but decreased survival of newly born neurons. These Aβ-induced neurogenic effects were also observed in choroid plexus of APP/PS1 mice, and detected also in autopsy tissue from AD patients. Analysis of signaling pathways revealed that pre-treating the choroid plexus epithelial cells with specific inhibitors of TyrK or MAPK diminished Aβ-induced neuronal proliferation. Taken together, our results support a role of Aβ in proliferation and differentiation in the choroid plexus epithelial cells in Alzheimer’s disease.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00018-013-1300-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Choroid plexus, Amyloid, Neurogenesis, Transgenic mice, Alzheimer’s disease patients

Introduction

Neurogenesis is produced in a number of areas in the postnatal mammalian brain, primarily in the subventricular zone of the lateral ventricles, the olfactory bulb, and the granular cell layer of the hippocampus. Nevertheless, over the last decade it has been suggested that choroid plexus epithelial cells show proliferation and differentiation potential, hosting neural progenitor cells [1–3]. However, published results to date do not provide any definitive findings, and there is some skepticism over the potency of choroid plexus neurogenesis.

The choroid plexus is a specialized ependymal structure, its epithelial cells being of the same origin as ventricular subependymal cells. It is important to note that the subependymal or subventricular zone of the lateral ventricles is one of the three main brain areas where neurogenesis is still detectable in old age [4–6]. The discovery of a de novo production of neurons has introduced the possibility of a new form of plasticity that could sustain memory processes. A growing body of evidence supports the view that promotion of adult neurogenesis improves pattern separation and spatial memory [7, 8]. In contrast, a decline in neurogenesis may underlie cognitive impairments associated with aging and disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [9, 10]. Although seemingly contradictory results have been reported in both murine and human studies [11], preserving or potentiating the production of new neurons has been regarded as a potential therapeutic strategy to delay or halt AD-linked cognitive decline. Furthermore, understanding the mechanisms of changes in neurogenesis observed at the initial and later stages of AD will contribute to the development of early AD biomarkers and reveal insights into the pathogenesis of AD.

The neuropathological characterization of AD involves a progressive deposition of β-amyloid protein (Aβ) protein in the brain parenchyma, often accompanied by Aβ deposition in cerebral blood vessels [12, 13] and choroid plexus [14, 15]. At the blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier, choroid plexus plays a critical role in the support of neuronal function by clearing Aβ [15–19].

β-amyloid protein oligomers are thought to be an important source of neurotoxicity in AD [20–23], and this insult can influence the cognitive outcome [24]. Paradoxically, Aβ can also promote neurogenesis, both in vitro and in vivo, by inducing neural progenitor cells to differentiate into neurons [25, 26]. All of these findings suggest that Aβ can be modulating neural progenitor cell population in the choroid plexus.

To approach this question, we studied the effect of Aβ on the proliferation and differentiation of choroid plexus epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo. In the present study, we investigated the impact of Aβ-induced neurogenesis in the choroid plexus in AD. Thus, we studied the choroid plexus from rat primary cell cultures, double transgenic APP/Ps1 mice, and AD patients. We also characterized the possible signaling mechanisms by which Aβ exerts its effects on neurogenesis.

Materials and methods

Animals

We used the double-transgenic APP/PS1 mice, B6.Cg-Tg (APPSwe, PSEN1dE9)/J mouse line (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA: stock no. 005864), which expresses human APP (Swedish mutation) and presenilin 1 with a deletion in exon 9 (APP/PS1). Both the APP/PS1 and the control non-transgenic littermates used were 12 months old. Animals were perfused transcardially either with saline buffer—for biochemical analysis—or 4 % paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PB (pH 7.4)—for immunohistochemical analysis. Animal care and handling was in accordance with Spanish legislation (Spanish Royal Decree 1201/2005 BOE published October 21, 2005) and the guidelines of the European Commission for the accommodation and care of laboratory animals (revised in Appendix A of the Council of Europe Convention ETS123) and according to the Council Directive 2010/63/UE of September 22, 2010. The use of wild-type and transgenic animals was an absolute requirement for this project; however, experiments were designed to minimize the use of animals. All transgenic mice and non-transgenic littermates were group-housed in standard cages with fiber bedding, under a 12/12 h light/dark cycle and with ad libitum access to food and water.

BrdU administration and quantification of BrdU-positive cells

The 12-month-old double transgenic APP/PS1 mice and control mice were intraperitoneally injected with BrdU (50 μg/kg, Sigma) once a day for 7 days, and were killed 28 days later. To estimate the total number of BrdU-positive cells in the brain, we performed DAB staining for BrdU in adjacent sections in a one-six series of every animal, from bregma 1 mm, to the caudal end from bregma to 1 mm. The BrdU-positive cells in the choroid plexus were counted to estimate the total number of BrdU-positive cells in the entire choroid plexus as reported in previous studies [27, 28]. To determine the fate of dividing cells, all BrdU-positive cells across 4–6 sections per mouse were analyzed by confocal microscopy for co-expression with NeuN. The number of double-positive cells was expressed as a percentage of BrdU-positive cells.

Human samples

Choroid plexus samples from human autopsies were obtained from the Institute of Neuropathology Brain Bank IDIBELL-Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge (Hospitalet de Llobregat, Spain), and from Service of Pathology and Neuropathology, and Neurological Tissues Biobank of Vigo-Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo (Vigo, Spain), after the approval of the local ethics committee. Subjects were selected on the basis of post-mortem diagnosis of AD according to the neurofibrillary pathology and β-amyloid plaques [29]. Control cases were considered those with no neurological symptoms and with no lesions in the neuropathological examination. The time between death and processing was between 2 and 12 h. Choroid plexus samples from AD-related pathology (n = 11, stages V–VI), and age-matched controls (n = 7), were homogenized for immunoblot determination.

Immunoblotting

Proteins were isolated from brain tissue by standard methods, and Western-blot assay was performed as described previously [16]. Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ software (NIH). Primary antibodies used included: goat anti-DCX (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA), rabbit anti-calbindin (1:5,000 Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA), mouse anti-NeuN (1:5,000, Millipore), and mouse anti-β-actin (1:20,000, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Immunohistochemistry

Mice brains were cut on a vibratome (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) at 40 μm, collected in cold 0.1 M PB, and incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4 °C. All primary antibodies were diluted in PB 0.1 M containing 0.5 % BSA and 0.5 % Triton X-100. For BrdU labeling, brain sections were pre-treated with 2 N HCl at 37 °C for 30 min before incubation with primary antibody. Human brains were cut with a microtome, and 2-μm-thick sections were processed free-floating for immunohistochemistry. The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-BrdU (1:20,000, Hybridoma Bank), rat anti-BrdU (1:400, Chemicon), goat anti-DCX (1:250, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit anti-calbindin (1:5,000 Millipore), and mouse anti-NeuN (1:500 Millipore). After overnight incubation, primary antibody staining was revealed using the avidin–biotin complex method (VECTASTAIN Elite ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and DAB chromogenic reaction (Vector Laboratories, Inc), or fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies: donkey anti-mouse IgG 488 (1:1,000; FluoProbes, Interchim), donkey anti-rat IgG 488 (1:1,000; FluoProbes, Interchim), chicken anti-goat IgG-Alexa 647 (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen), and DAPI nuclear staining (Sigma). Images were captured using a Zeiss LSM510 Meta scanning laser confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems).

Quantitative-PCR (qPCR)

RNA from the choroid plexus was extracted using the RNAspin mini kit (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA). The DNA of the samples was obtained from 1 μg of RNA with a high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) using the PCR program recommended by the manufacturer. DCX, calbindin, and GAPDH primers used were from Applied Biosystems. All samples were diluted 1:2 and run in triplicate. Standard curves for DCX, calbindin, and GAPDH with concentrations 1, 0.5, 0.25, and 0.125 μg were used to quantify DCX, calbindin mRNA. GAPDH was used as an internal control. Universal Taqman master mix from Applied Biosystems was used. Results were analyzed with the 7500 system SDS software (Applied Biosystems).

Cell culture and treatments

Choroid plexus cells from Wistar rats on postnatal day 3–5 (P3–P5) were prepared as described by Carro et al. [16]. Cells were grown 7 days before the treatment at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO2. Then, and after being serum starved for 2 h, the cells were incubated with fresh DMEM containing BrdU (50 μg/ml, Sigma), and the different reagents: Aβ1–42 (5 μM; AnaSpec, Inc., San Jose, CA), genistatin (1 μM, Sigma), LY294002 (20 μM, Calbiochem), and PD098059 (20 μM, Calbiochem). After 24 h, the media were replaced with fresh media with or without Aβ1–42 and the inhibitors, and incubated for 48 h, and 2 and 4 weeks.

Immunocytochemistry

Cell proliferation and differentiation were carried out in 24-well chamber slides. Cells were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.4). For BrdU labeling, fixed cells were pre-treated with 2 N HCl at 37 °C for 30 min, blocked in 0.1 M PB containing 2 % bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at room temperature, and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-BrdU (1:20,000, Hybridoma Bank), rat anti-BrdU (1:400, Chemicon), goat anti-doublecortin (DCX; 1:250, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse anti-NeuN (1:500, Millipore), mouse anti-GFAP (1:1,000; Sigma), rabbit anti-transthyretin (1:300, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), and rabbit anti-calbindin (1:5,000 Millipore). After overnight incubation, primary antibody staining was revealed using fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies: donkey anti-mouse IgG 488 (1:1,000; FluoProbes, Interchim), donkey anti-rat IgG 488 (1:1,000; FluoProbes, Interchim), chicken anti-goat IgG-Alexa 647 (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) and Texas Red goat anti-rabbit (1:1,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA).

Cell proliferation was determined by performing immunocytochemistry for BrdU and counting the number of BrdU-labeled cells in each well under the 20× objective using a fluorescent Nikon microscope. Cell differentiation was determined by performing double labeling immunocytochemistry for BrdU and the neuronal markers DCX and NeuN, or the glial marker GFAP, and the procedure was performed as described for BrdU detection.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences between groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance. Post hoc comparisons between two groups were done with Student’s t test. All calculations were made using SPSS v15.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Cell proliferation and differentiation in choroid plexus in APP/PS1 mice

To determine whether amyloidogenic environment could modulate cell proliferation in the choroid plexus in vivo, APP/PS1 mice (12 months of age) were evaluated. This age was selected based on several previous studies that have demonstrated an increase in hippocampal cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the progressive stage of an AD phenotype [30, 31]. Cells incorporating BrdU were found in the choroid plexus of both control and APP/PS1 mouse groups (Fig. 1a). However, the number of BrdU+ nuclei in the choroid plexus epithelial cells was significantly higher in APP/PS1 than in control mice (p < 0.01, Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Cell proliferation in the choroid plexus of APP/PS1 mice. a Representative BrdU+ nuclei in the choroid plexus of control (left) and APP/PS1 (right) mice. b Quantitative analysis showing higher number of BrdU+ nuclei in the choroid plexus of APP/PS1 mice compared with control non-transgenic mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01, n = 7 mice per group. LV lateral ventricle; CP choroid plexus. Scale bar = 20 μm

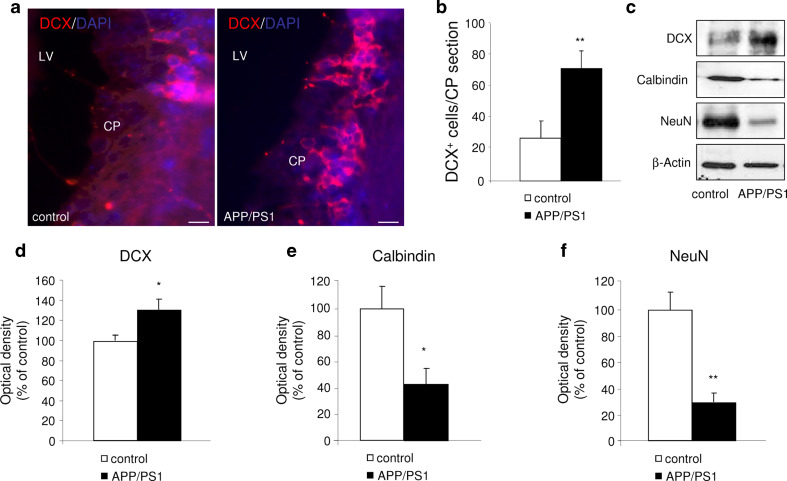

Cell proliferation in the choroid plexus of APP/PS1 mice was also confirmed by staining with DCX, the marker of immature neurons. Representative photomicrographs of DCX labeling are shown in Fig. 2a. The number of DCX+ cells in the choroid plexus was significantly higher in APP/PS1 mice than in control mice (p < 0.01, Fig. 2b), supporting the hypothesis that an amyloidogenic environment stimulates proliferation of immature neurons in the choroid plexus. This finding was corroborated by measurement of DCX protein levels by Western blot. Immunoblotting analysis revealed a significant enhancement in DCX expression in choroid plexus from APP/PS1 mice compared to control mice (p < 0.05, Fig. 2c, d). Expression of mature neuronal markers was also tested. In contrast to DCX expression, 12-month-old APP/PS1 showed a significant reduction in calbindin (p < 0.05, Fig. 2c, e), and NeuN (p < 0.01, Fig. 2c, f) expression in the choroid plexus, compared to control mice. We also analyzed the genes encoding for these proteins. The present study confirmed the presence of mRNA for DCX and calbindin in the choroid plexus, as previously described [32], and we describe here for the first time their expression in APP/PS1 mice. Interestingly, the expression of genes encoding DCX and calbindin was unchanged in 12-month-old APP/Ps1 mice compared to age-matched control mice (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b).

Fig. 2.

Cell differentiation in the choroid plexus of APP/PS1 mice. a Photomicrographs show fluorescent DCX (red) staining of choroid plexus epithelial cells in control (left) and APP/PS1 (right) mice. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars = 20 μm. b The histogram revealed higher number of DCX+ cells in the choroid plexus from APP/PS1 mice compared with control group. c Representative immunoblots showed the expression of DCX, calbindin, and NeuN in the choroid plexus homogenates of control and APP/PS1 mice. d Western-blot analysis showed that DCX expression was enhanced, whereas both calbindin (e) and NeuN expression (f) were reduced in the choroid plexus of APP/PS1 mice compared with control mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 4–7 mice per group. LV lateral ventricle; CP choroid plexus. Scale bar = 20 μm

To determine the extent of differentiation of survived BrdU-labeled cells, the brain sections from BrdU-treated APP/PS1 and control mice were processed for double-label immunohistochemistry with antibodies against BrdU and NeuN (Fig. 3a). Quantitative analysis showed that the number of BrdU-positive cells co-labeled with NeuN in the choroid plexus was significantly decreased in APP/PS1 mice compared to control mice (p < 0.05, Fig. 3b), representing an average of 3 % BrdU-positive cells colocalized with NeuN in control mice and less than 1 % in APP/PS1 mice. Taken together, our results support the hypothesis that an amyloidogenic environment initially might stimulate neurogenesis, but in due course survival of these newborn neurons would be reduced. In support of this last suggestion, apoptotic cell death was observed in choroid plexus from APP/PS1 mice [19].

Fig. 3.

Reduced neurogenic capacity in the choroid plexus of APP/PS1 mice. a Representative confocal microscopic image showing colocalization of BrdU (green) and NeuN (red) in the choroid plexus epithelial cells. White arrow indicates one double-labeled cell, and white asterisk indicates one NeuN+ cell. b Quantitative analysis showed a reduction in the number of BrdU-labeled cells double labeled for NeuN in the choroid plexus from APP/PS1 mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, n = 5 mice per group. LV lateral ventricle; CP choroid plexus. Scale bar = 20 μm

Expression of neuronal markers in choroid plexus in AD patients

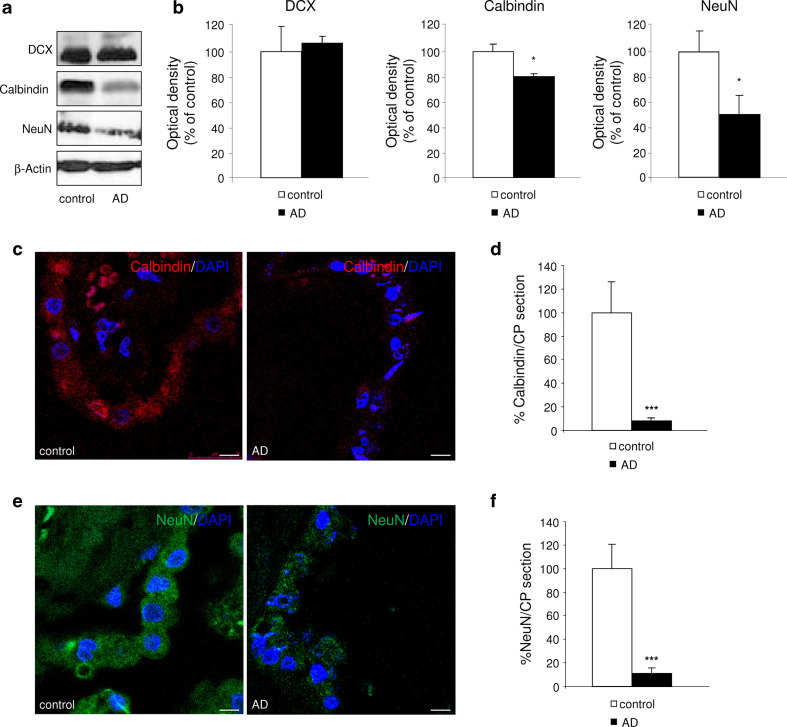

To verify the effect of amyloidogenic pathology on the expression of neuronal markers in choroid plexus from AD patients, this tissue was extracted from autopsies. With the help of Western blotting, we observed that, while DCX expression was unchanged in choroid plexus of AD patients compared to controls, a significant reduction in calbindin (p < 0.05), and NeuN expression (p < 0.05) was seen in the choroid plexus extracted from AD patients (Fig. 4a, b). These findings were confirmed by immunohistochemistry, showing a dramatic decreased in the immunoreactivity of calbindin (p < 0.001, Fig. 4c, d), and NeuN (p < 0.001, Fig. 4e, f)-positive cells in AD choroid plexus.

Fig. 4.

Amyloidogenic effects on the neuronal marker expression in human choroid plexus. a Representative immunoblots showed the expression of DCX, calbindin, and NeuN in the choroid plexus homogenates from autopsy samples from control and AD patients. b Western-blot analysis showed that DCX expression was unchanged, whereas both calbindin and NeuN expression were reduced in the choroid plexus from AD autopsy subjects compared with control group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, n = 4–6 human autopsies per group. Representative confocal microscopic images showing c calbindin and e NeuN in human choroid plexus. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Quantitative analysis showed a dramatic reduction in the immunoreactivity of d calbindin, and f NeuN signals in choroid plexus from AD subjects. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001, n = 4 human autopsies per group. Scale bar = 10 μm

Effects of Aβ1–42 on cell proliferation and differentiation in choroid plexus cultures

Cultured choroid plexus epithelial cells were incubated with Aβ1–42 for 48 h, and 2 and 4 weeks. Cellular proliferation, identified by BrdU reactivity, was vastly observed in choroid plexus epithelial cells cultured for 48 h and 2 weeks (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). Analyses of the number of BrdU-labeled cells revealed an inverse time–response relationship between Aβ1–42 and cell proliferation. Statistical analysis showed that the number of BrdU-labeled cells was significantly increased following Aβ1–42 treatment for 48 h, whereas 2 and 4 weeks after Aβ1–42 elicited no significant effects (p < 0.05, Fig. 5a, b).

Fig. 5.

Aβ1–42 stimulates BrdU incorporation in cultured choroid plexus epithelial cells. a BrdU-labeled choroid plexus epithelial cells in control (left) and Aβ1–42-treated cultured groups (right) at 48 h. b Quantitative analysis revealed an increase in BrdU-labeled cells after Aβ1–42 treatment for 48 h. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05. n = 3 independent experiments

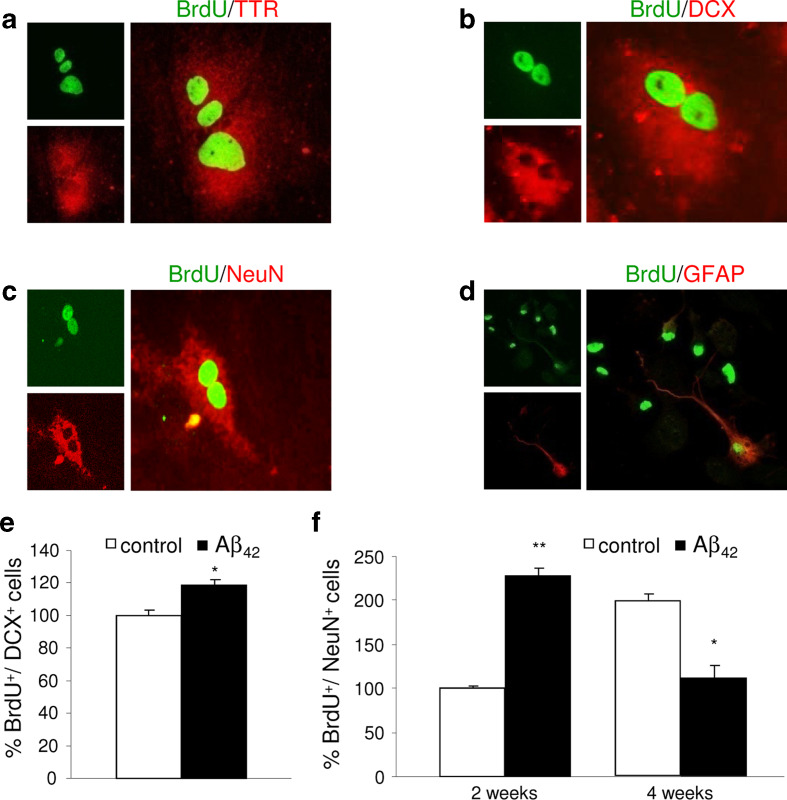

Next, we investigated differentiation potential of cultured choroid plexus epithelial cells. Analysis of colocalization using confocal microscopy indicated that choroid plexus epithelial cell cultures primarily contained transthyretin-labeled cells (Fig. 6a) but also cells of neuronal lineage, as demonstrated by the expression of phenotypic markers: DCX (Fig. 6b), NeuN (Fig. 6c), and GFAP (Fig. 6d).

Fig. 6.

Representative microscopic images showing colocalization of BrdU labeling (green) with immunoreactivity for phenotypic markers (red): a transthyretin (TTR), b doublecortin (DCX), c NeuN, and d GFAP. e Quantitative analysis indicating that the percentage of BrdU+ and DCX+ double-positive cells was increased by Aβ1–42 treatment for 48 h. f Quantitative analysis showed an increased percentage of BrdU+ and NeuN+ double-positive cells in choroid plexus epithelial cells treated for 2 weeks with Aβ1–42, whereas, this percentage was reduced after 4 weeks of treatment. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. n = 3 independent experiments

To determine whether Aβ1–42 affects cell differentiation in cultured choroid plexus epithelial cells, percentages of phenotypic markers were counted. Treatment with Aβ1–42 resulted in significant changes in the percentages of BrdU-labeled cells that were positive for neuronal markers. Forty-eight-hour Aβ1–42 treatment resulted in an increase number of DCX-positive cells that incorporated BrdU (p < 0.05, Fig. 6e). After long-term Aβ1–42 treatments, NeuN-positive cells were evaluated. Double staining indicated that number of cells expressing BrdU and NeuN was significantly increased after 2 weeks of Aβ1–42 treatment (p < 0.01, Fig. 6f), whereas this effect was inverted 4 weeks later (p < 0.05, Fig. 6g), suggesting a reduction in the survival of newly neuronal cells. This hypothesis is supported by a previous study where after exposure to Aβ1–42, caspase-3 and caspase-9 expressions, and apoptotic cell death increased in choroid plexus cell cultures [19].

Neurogenic effects of Aβ1–42 in choroid plexus cultures through TyrK/MAPK pathway

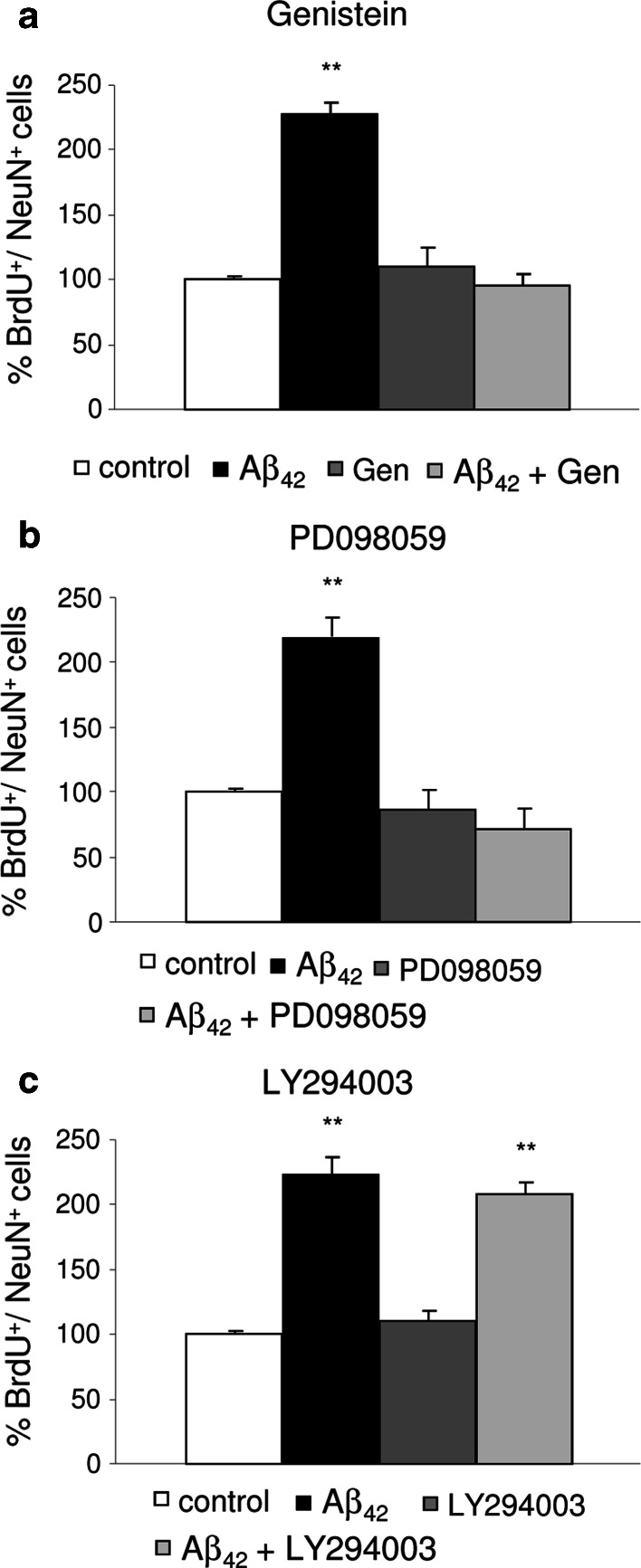

To evaluate the possible signal transduction pathways involved in Aβ-induced neurogenesis, we used several inhibitors of pathways known to be involved in neurogenesis in other systems. These molecules included genistein, an inhibitor of tyrosine kinases (TyrK); PD098059, a selective mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) inhibitor; and LY294002, a selective inhibitor of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K).

Choroid plexus epithelial cells were simultaneously treated with oligomeric Aβ1–42 and genistein for 2 weeks. At 1 μM concentration, genistein did not change the number of neurons observed versus controls. When Aβ1–42 was added in the presence of genistein, the previously observed increase of neurons mediated by Aβ, (Fig. 6f), was abolished (p < 0.01, Fig. 7a). Similarly, treatment with the MAPK inhibitor PD098059 did not induce any change in total neurons in the culture but was able to inhibit the Aβ1–42-induced increase in neurons (p < 0.01, Fig. 7b). In contrast, LY294002 was unable to inhibit Aβ1–42-induced neurogenesis (p < 0.01, Fig. 7c).

Fig. 7.

Signaling pathways involved in the neurogenic effect of Aβ1–42 in cultured choroid plexus epithelial cells. a A blockade of Aβ1–42-induced neurogenic effects, considered as percentage of BrdU+ and NeuN+ double-positive cells, was observed with genistein, and with b PD098059, whereas no blockade was found with LY294002. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01. n = 3 independent experiments

Discussion

In the present study, our findings suggest that, both in cell cultures and in vivo, choroid plexus epithelial cells show cell proliferation and differentiation capability, and Aβ is able to modulate these neurogenic effects. We investigated neurogenesis in the choroid plexus in the context of amyloidosis using three experimental approaches: (1) choroid plexus cultures treated with oligomeric Aβ1–42, (2) double transgenic APP/PS1 mice, (3) and AD patient autopsies. APP/PS1 mice generate several-fold more of the highly amyloidogenic Aβ1–42 compared to Aβ1–40 and thus develop cerebral amyloidosis in hippocampus as early as 8 to 12 weeks [33].

Previous studies have described that choroid plexus epithelial cells had the capacity to proliferate and differentiate into other type of cells [1, 2, 34], based, at least in part, on the existence of a subpopulation of neural progenitor cells within the choroid plexus [3]. The proliferation of choroid plexus epithelial cells was reported in an experimental model of ischemic brain injury in the rat: BrdU-positive cells in the choroid plexus expressed GFAP and NeuN [2, 34]. The increase in the number of the BrdU-positive cells indicates that choroid plexus epithelial cells have the ability to proliferate when stimulated. It can be suggested that these cells have the ability to proliferate in response to certain injury-related stimuli. It is likely that the neural progenitor cells among choroid plexus epithelial cells are involved in proliferation following injury to the central nervous system.

It has been shown that several pathological conditions (ischemia, epilepsy, and trauma) seem to upregulate neural stem cell activity in the classical brain areas where neurogenesis is detectable in adult age, such as subventricular zone and dentate gyrus (for review, see Kuhn et al., [35]). These findings suggest that neural stem cell populations might be affected in AD. Thus, we investigated whether Aβ would modulate proliferation, survival, and differentiation of those neural progenitors cell within choroid plexus.

Numerous studies reported that the choroid plexus is considered an important source of trophic factors (for review, see Alvira-Botero and Carro, [15]), including several growth factors that are potent modulators of neurogenesis, such as nerve growth factor (NGF), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), [27, 36–38], which may support neural progenitor cells within the choroid plexus by paracrine fashion. It is also known that in other brain areas, amyloid deposits stimulate the local accumulation of several growth factors, including BDNF and VEGF, which possess strong regulatory capacity for neurogenesis [39, 40]. The neurogenic effect of the Aβ peptide on hippocampal neuronal stem cells has also been reported [25]. In light of these findings, Aβ could be stimulating neural progenitor cells within the choroid plexus through prompting endogenous growth factor actions. This proliferation and differentiation stimulus in an amyloidogenic environment may also represent an endogenous neural replacement response to neurodegeneration and dysfunction. Indeed, in both AD patients and APP/PS1 mice, cell death in the choroid plexus has been reported [19]. As the APP/PS1 strain shows increased neurogenesis in the progressive stage of AD [30], it may reproduce the neurogenesis that is characteristic of AD patients [41].

In this study, we observed enhanced cell proliferation in the choroid plexus of APP/PS1 mice, compared to control mice. APP/PS1 mice overexpress APP but additionally express mutated PS1, and generate several-fold more of the highly amyloidogenic Aβ1–42 compared to Aβ1–40 and thus develop cerebral amyloidosis in hippocampus as early as 8 to 12 weeks. We detected an up-regulation of DCX-positive immature neurons and a reduction in mature neurons. This could be due to a dysfunction in the maturation processes or that the mature neurons undergo cell death. In vitro, we have observed that newly proliferative cells in the choroid plexus cultures differentiated into neurons, observed as an increased number of DCX-positive immature and NeuN-positive mature neurons by 2 weeks after Aβ treatment. However, many of these newly born neurons die shortly after differentiation, and drastically diminished 4 weeks in vitro. This suggests that the neurons do mature but undergo cell death. This agrees with previous findings from our group where we found an increase in cell death in choroid plexus of APP/PS1 mice [19].

Furthermore, both our in vivo and in vitro findings are consistent with the study by Li et al. [42], in which intracerebroventricular infusion of Aβ25–35 stimulated proliferation of progenitor cells in the hippocampal dentate gyrus of adult male mice, but a large population of the newborn cells proceeded to die in the second week after birth, a critical period for neurite growth. We suggest that these neurons might fail to obtain the sufficient quantity of neurotrophic factors, and would die by a process of programmed cell death. In agreement with this hypothesis, levels of neurotrophic factors are decreased in AD brains, including insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I), BDNF, and VEGF [43–46]. We also reported Aβ-induced cell death in the choroid plexus from AD patients and APP/PS1 mice [19].

The work by López-Toledano and Shelanski [25] suggested a dependence of the neurogenic effect of Aβ on the state of aggregation of this peptide. According to this study, a possible interpretation of our data is that in earlier stages of AD, when the excess of Aβ is enough to form oligomeric but not fibrillar aggregates, the oligomers could activate a compensatory mechanism to replace lost or damaged neurons by increasing the differentiation of neuronal progenitors into new neurons [47, 48]. By later stages, Aβ deposits in choroid plexus are formed and become massive, and the balance could shift to fibrillar Aβ that could be more neurotoxic [19].

The impairment of neurogenesis observed with the aid of BrdU studies has been confirmed by quantitative Western-blot analysis of DCX, calbindin, and NeuN content, as immature and mature neuronal markers, respectively, in choroid plexus from APP/PS1 mice. This alternative approach for assessing neurogenesis in choroid plexus was also used in the subventricular-olfactory bulb system [49]. We also analyzed neurogenesis in choroid plexus from postmortem human brains by Western-blot and immunohistochemistry methods, as reported in the hippocampus of senile and presenile AD patients [41, 50]. Our results suggest that a micro-environment with chronic amyloid deposition can lead to a significant decrease in neurogenesis, consistent with data from our experiments with postmortem AD brains where a reduced expression of these markers in the choroid plexus has been observed.

One of the principal observations in this study was that neurogenic effects of Aβ in choroid plexus epithelial cells involved regulation of TyrK/MAPK signaling. The inhibition of neurogenesis by genistein suggests that tyrosine kinases are involved in this process. These kinases include the classical neurotrophin receptors that are essential in nervous system development (for review, see Chao et al. [51]). Recently, we have described the presence of p75NTR, a receptor for neurotrophins such as NGF and BDNF, in the choroid plexus [52]. We examined two signaling pathways downstream of TyrK. Inhibition of the PI3K system did not affect neurogenesis. In contrast, inhibition of the MAPK pathway blocked neurogenesis. The MAPK pathway has been implicated in the regulation of cell growth and proliferation, in differentiation, and in apoptosis [53, 54]. Numerous studies have described Aβ-induced activation of MAPK. In vivo injection of Aβ induces the activity of p38 MAPK in rat [55], and chronic exposure of human microglia to Aβ1-42 led to enhanced p38 MAPK expression [56]. All of these findings reinforce the implication of MAPK activation in the pathogenesis of AD, previously reported [57].

In summary, our present findings indicate that Aβ regulates the proliferation and differentiation of neural progenitor cells in the choroid plexus. However, our results suggest that amyloidogenic environment tends to down-regulate neurogenesis. Analysis of signaling pathways in vitro suggest that Aβ may stimulate the proliferation of newly born neurons through a mechanism that is dependent on MAPK activation. This study supports a novel role of choroid plexus in the processes of AD neuropathology, providing new insights into the mechanisms of neurogenic regulation.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (FIS 09-01636), Fundación Investigación Médica Mutua Madrileña (2008/93; 2010/0004), and CIBERNED (BESAD-P.2010) awarded to E. Carro. F. Wandosell was additionally supported from Direccion General de Ciencia y Tecnologia-DGCYT (SAF2009-12249-C02-01), EU-FP7-2009-CT222887, Fundación Ramón Areces, and CIBERNED (BESAD-P.2010). C. Spuch was supported by programmes from Xunta de Galicia (INCITE2009, and “Isidro Parga Pondal”). We thank Agnieszka Krzyzanowska, PhD, for the careful revision of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kitada M, Chakrabortty S, Matsumoto N, Taketomi M, Ide C. Differentiation of choroid plexus ependymal cells into astrocytes after grafting into the pre-lesioned spinal cord in mice. Glia. 2001;36:364–374. doi: 10.1002/glia.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Y, Chen J, Chopp M. Cell proliferation and differentiation from ependymal, subependymal and choroid plexus cells in response to stroke in rats. J Neurol Sci. 2002;193:137–146. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(01)00657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Itokazu Y, Kitada M, Dezawa M, Mizoguchi A, Matsumoto N, Shimizu A, Ide C. Choroid plexus ependymal cells host neural progenitor cells in the rat. Glia. 2006;53:32–42. doi: 10.1002/glia.20255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luskin MB. Restricted proliferation and migration of postnatally generated neurons derived from the forebrain subventricular zone. Neuron. 1993;11:173–189. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90281-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiasson BJ, Tropepe V, Morshead CM, van der Kooy D. Adult mammalian forebrain ependymal and subependymal cells demonstrate proliferative potential, but only subependymal cells have neural stem cell characteristics. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4462–4471. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04462.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doetsch F, Caille I, Lim DA, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Subventricular zone astrocytes are neural stem cells in the adult mammalian brain. Cell. 1999;97:703–716. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80783-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sahay A, Scobie KN, Hill AS, O’Carroll CM, Kheirbek MA, Burghardt NS, Fenton AA, Dranovsky A, Hen R. Increasing adult hippocampal neurogenesis is sufficient to improve pattern separation. Nature. 2011;472:466–470. doi: 10.1038/nature09817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stone SS, Teixeira CM, Devito LM, Zaslavsky K, Josselyn SA, Lozano AM, Frankland PW. Stimulation of entorhinal cortex promotes adult neurogenesis and facilitates spatial memory. J Neurosci. 2011;31:13469–13484. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3100-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clelland CD, Choi M, Romberg C, Clemenson GD, Jr, Fragniere A, Tyers P, Jessberger S, Saksida LM, Barker RA, Gage FH, Bussey TJ. A functional role for adult hippocampal neurogenesis in spatial pattern separation. Science. 2009;325:210–213. doi: 10.1126/science.1173215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazarov O, Mattson MP, Peterson DA, Pimplikar SW, van Praag H. When neurogenesis encounters aging and disease. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:569–579. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winner B, Kohl Z, Gage FH. Neurodegenerative disease and adult neurogenesis. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33:1139–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rensink AA, de Waal RM, Kremer B, Verbeek MM. Pathogenesis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2003;43:207–223. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selkoe DJ. Cell biology of protein misfolding: the examples of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1054–1061. doi: 10.1038/ncb1104-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dietrich MO, Spuch C, Antequera D, Rodal I, De Yebenes JG, Molina JA, Bermejo F, Carro E. Megalin mediates the transport of leptin across the blood–CSF barrier. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:902–912. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alvira-Botero X, Carro EM. Clearance of amyloid-beta peptide across the choroid plexus in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Aging Sci. 2010;3:219–229. doi: 10.2174/1874609811003030219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carro E, Trejo JL, Gomez-Isla T, Leroith D, Torres-Aleman I. Serum insulin-like growth factor I regulates brain amyloid-beta levels. Nat Med. 2002;8:1390–1397. doi: 10.1038/nm1202-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zlokovic BV. Clearing amyloid through the blood–brain barrier. J Neurochem. 2004;89:807–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antequera D, Vargas T, Ugalde C, Spuch C, Molina JA, Ferrer I, Bermejo-Pareja F, Carro E. Cytoplasmic gelsolin increases mitochondrial activity and reduces Abeta burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;36:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vargas T, Ugalde C, Spuch C, Antequera D, Moran MJ, Martin MA, Ferrer I, Bermejo-Pareja F, Carro E. Abeta accumulation in choroid plexus is associated with mitochondrial-induced apoptosis. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:1569–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416:535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lesne S, Koh MT, Kotilinek L, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Yang A, Gallagher M, Ashe KH. A specific amyloid-beta protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature. 2006;440:352–357. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shankar GM, Bloodgood BL, Townsend M, Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ, Sabatini BL. Natural oligomers of the Alzheimer amyloid-beta protein induce reversible synapse loss by modulating an NMDA-type glutamate receptor-dependent signaling pathway. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2866–2875. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4970-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koffie RM, Meyer-Luehmann M, Hashimoto T, Adams KW, Mielke ML, Garcia-Alloza M, Micheva KD, Smith SJ, Kim ML, Lee VM, Hyman BT, Spires-Jones TL. Oligomeric amyloid beta associates with postsynaptic densities and correlates with excitatory synapse loss near senile plaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4012–4017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811698106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.López-Toledano MA, Shelanski ML. Neurogenic effect of beta-amyloid peptide in the development of neural stem cells. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5439–5444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0974-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calafiore M, Copani A, Deng W. DNA polymerase-β mediates the neurogenic effect of β-amyloid protein in cultured subventricular zone neurospheres. J Neurosci Res. 2012;90:559–567. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antequera D, Portero A, Bolos M, Orive G, Hernández RM, Pedraz JL, Carro E. Encapsulated VEGF-secreting cells enhance proliferation of neuronal progenitors in the hippocampus of AβPP/Ps1 mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;29:187–200. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-111646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pérez-González R, Antequera D, Vargas T, Spuch C, Bolós M, Carro E. Leptin induces proliferation of neuronal progenitors and neuroprotection in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24:17–25. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-102070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braak H, Braak E. Temporal sequence of Alzheimer’s disease-related pathology. In: Peters A, Morrison JH, editors. Cerebral cortex. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press; 1999. pp. 475–512. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu Y, He J, Zhang Y, Luo H, Zhu S, Yang Y, Zhao T, Wu J, Huang Y, Kong J, Tan Q, Li XM. Increased hippocampal neurogenesis in the progressive stage of Alzheimer’s disease phenotype in an APP/Ps1 double transgenic mouse model. Hippocampus. 2009;19:1247–1253. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Esteras N, Bartolomé F, Alquézar C, Antequera D, Muñoz U, Carro E, Martín-Requero A. Altered cell cycle-related gene expression in brain and lymphocytes from a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease [amyloid precursor protein/presenilin 1 (PS1)] Eur J Neurosci. 2012;36:2609–2618. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marques F, Sousa JC, Coppola G, Gao F, Puga R, Brentani H, Geschwind DH, Sousa N, Correia-Neves M, Palha JA. Transcriptome signature of the adult mouse choroid plexus. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2011;8:1–11. doi: 10.1186/2045-8118-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borchelt DR, Ratovitski T, van Lare J, Lee MK, Gonzales V, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Price DL, Sisodia SS. Accelerated amyloid deposition in the brains of transgenic mice coexpressing mutant presenilin 1 and amyloid precursor proteins. Neuron. 1997;19:939–945. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80974-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emerich DF, Skinner SJ, Borlongan CV, Thanos CG. A role of the choroid plexus in transplantation therapy. Cell Transplant. 2005;14:715–725. doi: 10.3727/000000005783982576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuhn HG, Palmer TD, Fuchs E. Adult neurogenesis: a compensatory mechanism for neuronal damage. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;251:152–158. doi: 10.1007/s004060170035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu W, Cheng S, Xu G, Ma M, Zhou Z, Liu D, Liu X. Intranasal nerve growth factor enhances striatal neurogenesis in adult rats with focal cerebral ischemia. Drug Deliv. 2011;18:338–343. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2011.557785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee J, Duan W, Mattson MP. Evidence that brain-derived neurotrophic factor is required for basal neurogenesis and mediates, in part, the enhancement of neurogenesis by dietary restriction in the hippocampus of adult mice. J Neurochem. 2002;82:1367–1375. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jin K, Zhu Y, Sun Y, Mao XO, Xie L, Greenberg DA. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) stimulates neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11946–11950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182296499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burbach GJ, Hellweg R, Haas CA, Del Turco D, Deicke U, Abramowski D, Jucker M, Staufenbiel M, Deller T. Induction of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in plaque-associated glial cells of aged APP23 transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2421–2430. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5599-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tarkowski E, Issa R, Sjögren M, Wallin A, Blennow K, Tarkowski A, Kumar P. Increased intrathecal levels of the angiogenic factors VEGF and TGF-beta in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23:237–243. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(01)00285-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jin K, Peel AL, Mao XO, Xie L, Cottrell BA, Henshall DC, Greenberg DA. Increased hippocampal neurogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:343–347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2634794100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li L, Xu B, Zhu Y, Chen L, Sokabe M, Chen L. DHEA prevents Aβ25-35-impaired survival of newborn neurons in the dentate gyrus through a modulation of PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling. Neuropharmacology. 2010;59:323–333. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steen E, Terry BM, Rivera EJ, Cannon JL, Neely TR, Tavares R, Xu XJ, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Impaired insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and signaling mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease—is this type 3 diabetes? J Alzheimer Dis. 2005;7:63–80. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-7107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagahara AH, Merrill DA, Coppola G, Tsukada S, Schroeder BE, Shaked GM, Wang L, Blesch A, Kim A, Conner JM, Rockenstein E, Chao MV, Koo EH, Geschwind D, Masliah E, Chiba AA, Tuszynski MH. Neuroprotective effects of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in rodent and primate models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 2009;15:331–337. doi: 10.1038/nm.1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moloney AM, Griffin RJ, Timmons S, O’Connor R, Ravid R, O’Neill C. Defects in IGF-1 receptor, insulin receptor and IRS-1/2 in Alzheimer’s disease indicate possible resistance to IGF-1 and insulin signalling. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:224–243. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spuch C, Antequera D, Portero A, Orive G, Hernández RM, Molina JA, Bermejo-Pareja F, Pedraz JL, Carro E. The effect of encapsulated VEGF-secreting cells on brain amyloid load and behavioral impairment in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Biomaterials. 2010;31:5608–5618. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dahlgren KN, Manelli AM, Stine WB, Jr, Baker LK, Krafft GA, LaDu MJ. Oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid-beta peptides differentially affect neuronal viability. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32046–32053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim HJ, Chae SC, Lee DK, Chromy B, Lee SC, Park YC, Klein WL, Krafft GA, Hong ST. Selective neuronal degeneration induced by soluble oligomeric amyloid beta protein. FASEB J. 2003;17:118–120. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0987fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang C, McNeil E, Dressler L, Siman R. Long-lasting impairment in hippocampal neurogenesis associated with amyloid deposition in a knock-in mouse model of familial Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2007;204:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boekhoorn K, Joels M, Lucassen PJ. Increased proliferation reflects glial and vascular-associated changes, but not neurogenesis in the presenile Alzheimer hippocampus. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;24:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chao MV. Neurotrophins and their receptors: a convergence point for many signalling pathways. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:299–309. doi: 10.1038/nrn1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spuch C, Carro E. The p75 neurotrophin receptor localization in blood–CSF barrier: expression in choroid plexus epithelium. BMC Neurosci. 2011;12:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-12-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang L, Karin M. Mammalian MAP kinase signalling cascades. Nature. 2001;410:37–40. doi: 10.1038/35065000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rohe M, Carlo AS, Breyhan H, Sporbert A, Militz D, Schmidt V, Wozny C, Harmeier A, Erdmann B, Bales KR, Wolf S, Kempermann G, Paul SM, Schmitz D, Bayer TA, Willnow TE, Andersen OM. Sortilin-related receptor with A-type repeats (SORLA) affects the amyloid precursor protein-dependent stimulation of ERK signaling and adult neurogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:14826–14834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710574200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Giovannini MG, Scal C, Prosperi C, Bellucci A, Vannucchi MG, Rosi S, Pepeu G, Casamenti F. Beta-amyloid-induced inflammation and cholinergic hypofunction in the rat brain in vivo: involvement of the p38MAPK pathway. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;11:257–274. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Franciosi S, Ryu JK, Choi HB, Radov L, Kim SU, McLarnon JG. Broad-spectrum effects of 4-aminopyridine to modulate amyloid beta1-42-induced cell signaling and functional responses in human microglia. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11652–11664. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2490-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhu X, Rottkamp CA, Hartzler A, Sun Z, Takeda A, Boux H, Shimohama S, Perry G, Smith MA. Activation of MKK6, an upstream activator of p38, in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2001;79:311–318. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.