Abstract

Oxysterol-binding protein/OSBP-related proteins (ORPs) constitute a conserved family of sterol/phospholipid-binding proteins with lipid transporter or sensor functions. We investigated the spatial occurrence and regulation of the interactions of human OSBP/ORPs or the S. cerevisiae orthologs, the Osh (OSBP homolog) proteins, with their endoplasmic reticulum (ER) anchors, the VAMP-associated proteins (VAPs), by employing bimolecular fluorescence complementation and pull-down set-ups. The ORP–VAP interactions localize frequently at distinct subcellular sites, shown in several cases to represent membrane contact sites (MCSs). Using established ORP ligand-binding domain mutants and pull-down assays with recombinant proteins, we show that ORP liganding regulates the ORP–VAP association, alters the subcellular targeting of ORP–VAP complexes, or modifies organelle morphology. There is distinct protein specificity in the effects of the mutants on subcellular targeting of ORP–VAP complexes. We provide evidence that complexes of human ORP2 and VAPs at ER–lipid droplet interfaces regulate the hydrolysis of triglycerides and lipid droplet turnover. The data suggest evolutionarily conserved, complex ligand-dependent functions of ORP–VAP complexes at MCSs, with implications for cellular lipid homeostasis and signaling.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00018-014-1786-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: BiFC, Membrane contact site, OSBP, Oxysterol, VAMP-associated protein

Introduction

Oxysterol-binding protein (OSBP) is a cytoplasmic protein that displays affinity for a number of oxysterols [1, 2], cholesterol [3] and phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate (PI4P) [4]. Families of proteins homologous to OSBP, designated OSBP-related proteins (ORPs), are present throughout the eukaryotic kingdom. In mammals including humans the gene/protein family consists of 12 members [5–7] while in yeast S. cerevisiae there are seven OSBP homolog (Osh) proteins [8]. Observations in a number of cell models and organisms have identified ORPs as lipid transporters or mediators of lipid signals that regulate an unforeseen variety of cellular processes. However, the molecular mechanisms of their action have remained poorly understood [9–11].

A majority of the mammalian ORPs and three of the yeast Osh proteins have the capacity to associate with endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membranes either via a short sequence motif designated two phenylalanines in an acidic tract (FFAT) [12, 13] or a carboxy-terminal membrane-spanning segment that targets the ER [14, 15]. The FFAT motifs interact specifically with VAPs, type II integral membrane proteins of the ER which are in yeast called Scs2p and -22p [16–19]. The VAPs have been assigned functions as regulators of membrane trafficking, lipid metabolism and transport, microtubule organization, and the unfolded protein response [20]. Of note, a point mutation (P506S) in human VAPB that is defective in binding OSBP [21], results in late-onset spinal muscular atrophy or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [22, 23]. Most ORPs carry an amino-terminal region containing a pleckstrin homology (PH) domain that binds phosphoinositides and targets distinct non-ER organelle membranes [9]. Prompted by the dual (ER and non-ER) membrane targeting capacity, several ORPs have been suggested to localize and function at sites of close contact (10–30 nm distance) between ER and other organelles, designated membrane contact sites (MCSs) [24–31].

Membrane contact sites have gained increasing attention, as a number of their molecular constituents have been identified and the understanding of their function has begun to emerge. These structures have established roles in lipid syntheses and inter-organelle transport, control of Ca2+ fluxes, and in a number of signaling processes [28, 32–36]. Relevant to the functional section of the present study, cytoplasmic lipid droplets (LD) responsible for neutral lipid storage form intimate contacts with the ER. They are often found partially wrapped in sheets of ER membrane [37, 38]. Adipophilin [38] and the triglyceride-synthesizing FATP1/acyl-CoA synthetase–DGAT2/diacylglycerol acyltransferase complex [39] were reported to specifically distribute to these contact zones, suggesting their central role in the synthesis of LD triglycerides. Moreover, continuities of the ER bilayer and the LD limiting monolayer were reported to deliver TG synthesizing enzymes to the LD surface [40–42]. A number of protein complexes responsible for organelle tethering at distinct MCSs have been identified [43–50]. However, the role of ORP/Osh proteins at MCSs has not been systematically addressed.

In the present study, we investigate the spatial occurrence of protein–protein interactions between the human and yeast ORP/Osh proteins and their ER receptors, the VAPA/B and Scs2/22 proteins. We provide evidence that the interactions occur in several cases at distinct sites which represent MCSs, and that ORP liganding controls the ORP–VAP interactions and the subcellular targeting of the ORP–VAP complexes. As a specific focus, we provide evidence for a function of human ORP2–VAP complexes that localize at the ER–LD interface, in cellular triglyceride metabolism.

Experimental procedures

Plasmids

The plasmids used in this study are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Plasmids for Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) in mammalian cells were constructed by PCR amplification of full-length OSBPL1A (ORP1L), OSBPL2 (ORP2), OSBP2 (ORP4L), OSBPL5 (ORP5), OSBPL6 (ORP6), OSBPL7 (ORP7), OSBPL8 (ORP8), OSBPL9 (ORP9L), OSBPL10 (ORP10), OSBPL11 (ORP11) and OSBP cDNAs and insertion into a Venus-based BiFC vector [51] as C-terminal fusions with the Vn (aa 1–172) fragment. The human VAPA and -B cDNAs were correspondingly amplified and C-terminal fusions with the Vc (aa 154–238) generated.

Full-length yeast OSH1, OSH2 and OSH3 were PCR amplified from genomic yeast DNA and cloned into an EYFP-based BiFC vector [52] as C-terminal fusions with the Yn (aa 1–172) fragment. Similarly, full-length SCS2 and SCS22, lacking the intron, were cloned as C-terminal fusions with the Yc (aa 173–238) fragment.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the FFAT motifs and generation of sterol-binding deficient 4-aa deletions were performed using QuikChange® XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). Similarly, inositol-phosphate-binding cleft triple point mutations [4, 53] were generated of ORP2(H178A, H179A, K423A) and ORP4L(H628A, H629A, K834A). These mutants are in the text called ORP2(mPIP) and ORP4L(mPIP). All constructs were verified by sequencing with a cycle-sequencing kit (BigDye3.1) and an automated ABI3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems/Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA).

Antibodies

The anti-GFP was obtained from Dr. Jussi Jäntti (Institute of Biotechnology, Finland). The rabbit anti-ORP2 was described in [55], and anti-VAPA, and -B were from M.A. De Matteis (Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine, Naples, Italy). Anti-β-actin and ERGIC-53/p58 antibodies were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and the GM130 antibody from BD Bioscience (San Jose, CA, USA). The fluorescent secondary antibodies (fAlexa Fluor-594 goat anti-rabbit and fAlexa Fluor-594 goat anti-mouse) were from Molecular Probes/Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Recombinant protein production

For bacterial production of ORP2, full-length ORP2 cDNA was cloned into the vector pFOLD-His6 (J. Peränen, Institute of Biotechnology, Helsinki, Finland) and the protein produced in E. coli BL21(DE3). Expression was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG at 18 °C over night. Cells were collected and resuspended in 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, complete Protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). After addition of Triton X-100 to a final concentration of 0.5 %, the cells were kept on ice for 10 min, lysed by sonication, and NaCl was added to a final concentration of 0.5 M. Lysates were centrifuged (10 min 12,000 rpm, 4 °C), and the N-terminally tagged ORP2 was purified from the supernatant using Ni-NTA Agarose (Invitrogen). GST and GST–VAPA were produced as described in [54].

In vitro ORP2–VAPA-binding assay

ORP2 was bound with oxysterol overnight at 4 °C by mixing 0.5 μM protein with 6 μM 22(R)OHC or 25OHC, or same volume of EtOH in a total volume of 80 μl of binding buffer (20 mM HEPES, 200 mM NaCl and 1 mM DTT). VAPA-GST or GST was added to the reaction (0.5 μM) together with 0.01 % Triton X-100, followed by a 2-h incubation at room temperature with gentle mixing. The complexes were combined with 20 μl glutathione Sepharose (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) for 1 h at room temperature with gentle mixing. Unbound proteins were removed by washing four times (20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl and 0.01 % Triton X-100). The GST-bound protein complexes were eluted into 10 μl of reducing Laemmli sample buffer (LSB) by heating for 5 min at 100 °C, subjected to SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue.

Cell culture

The human hepatoma cell line HuH7 was cultured in Eagle’s minimal essential medium with Earle’s salts (EMEM, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco/Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin.

Pull-down assays

HuH7 cells were grown in 2 cm wells at 37 °C to about 70 % confluence and transfected with VnORP plasmids using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The next day, the cells were washed and resuspended in 1 ml lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 10 % glycerol, 0.5 % Triton X-100, 0.5 % Na-deoxycholate, Protease inhibitor cocktail, Roche Diagnostics). Cell breakage was achieved by 20× shearing in lysis buffer, 15 min rotation at +4 °C, and followed by 5 min centrifugation at 13,000 rpm in a microcentrifuge to remove unbroken cells. The obtained lysates were incubated with 10 µg GST-VAPA or GST for 45 min at room temperature, after which 30 µl of Glutathione-Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare) beads were added and additional 30 min incubation at room temperature was performed. The beads were then washed three times with lysis buffer, resuspended in 40 µl LSB and boiled for 5 min.

For Western blot analysis, proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Bound antibodies were visualized with the ECL detection system (Thermo Scientific). Each pull-down was performed at least three times. Quantifications were performed using ImageJ 1.42 and normalization to the amount of ORP in the lysate and to the GST-VAPA pulled down. The significance of the differences observed in pull-down efficiency was determined with the Student’s t test (two-tailed, independent).

Immunofluorescence staining

After cell fixation (4 % paraformaldehyde in PBS), aldehyde groups were blocked (50 mM NH4Cl/PBS, 15 min) and cells were permeabilized (0.1 % Triton X-100/PBS, 10 min). Unspecific binding was blocked (10 % FBS/PBS, 45 min), followed by incubation with the primary antibody in 5 % FBS/PBS, 45 min at 37 °C. After washing with PBS (3 × 5 min), the cells were incubated with the Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies in 5 % FBS/PBS, 45 min at 37 °C. The cells after washing with PBS were mounted in Mowiol (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA)—1,4-diazabicyclo-[2.2.2]octane (50 mg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich).

Fluorescence microscopy of HuH7 cells

HuH7 cells were grown at 37 °C to about 70 % confluence and transfected with the BiFC plasmids and the cotransfection marker using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen). After 24-h incubation, cells were either directly visualized or fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). On-demand nuclei were stained for 5 min with Hoechst (2 μg/ml) in PBS before mounting. Fluorescence signals were observed using a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope with an ECPlnN 40×/0.75 DICII objective and Colibri laser. Images were recorded with the Axio Vision Rel. 4.8.1 software (Carl Zeiss Imaging Solutions GmbH, Oberkochen, Germany). The exposure time for the Bimolecular Fluorescence complementation of Venus was 1–5 s and of the cotransfection marker mCherry-VAPs 0.5–1 s. For quantification of the signal intensity low magnification original images obtained with the same microscope and the same exposure time were used and whole cell signal intensities were analyzed. The BiFC interaction intensities were quantified using ImageJ 1.42 by measuring the image mean gray value of the total BiFC signal and normalizing it to the intensity of the cotransfection marker. For each condition, the signals in at least 100 cells were quantified. Colocalization efficiencies were analyzed using the JACoP plugin of ImageJ 1.42 and a minimum of 25 cells per condition. Fluorescent particle size and number were calculated with ImageJ 1.42 in a minimum of 20 cells per condition. Statistical significances were determined with the Student’s t test (two-tailed, independent). Image panels were prepared using Adobe Photoshop7 software.

Visualization of lipid droplets (LD) in HuH7 cells

HuH7 cells were grown to about 70 % confluence and transfected with the ORP2 and VAPA BiFC plasmids using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen) or silenced with ORP2–VAPA–VAPB siRNAs (see below). After 24-h incubation, LD were labeled with Bodipy-C12 (Molecular Probes, Mountain View, CA, USA) in serum-free medium for 1 h. Cells were washed, chased for 6 h with fresh medium containing different amounts of vehicle, 22(R)OHC or 25OHC in ethanol, and fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde in PBS. LD particle size and number were analyzed using ImageJ Analyze Particles. LD distribution was measured by plotting the profile (ImageJ) over a same length straight line starting from the center of the nucleus to about half way to the cell edge. Eight lines in 45° distance were analyzed per cell.

Transmission electron microscopy

HuH7 cells were grown to about 70 % confluence and transfected with empty vectors (control) or the ORP2(wt, ΔELSK) and VAPA BiFC plasmids using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen). After an overnight incubation, cells were fixed with 2 % glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M Na-cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4), embedded, sectioned for cell monolayers as described previously [56], and studied with a Jeol EX1200 II TEM (Jeol Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) operating at 80 kV. Images were acquired with ES500W, model 782, CCD camera (Gatan Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA). LD–ER contact sites were quantified by measuring the LD–ER membrane contact length, normalizing it to the LD circumference, and counting free LDs. A minimum of 50 LDs were analyzed per condition.

RNA interference

Silencing of ORP2, VAPA, and VAPB in HuH7 cells was carried out using the Silencer Select™ (Invitrogen/Ambion) siRNAs s19149 (ORP2), s17626 (VAPA), and s17624 (VAPB), which were transfected for a total of 48 h with the Interferin reagent (Polyplus, Illkirch, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The protein levels in the cells were assessed by Western blotting with VAPA, VAPB, ORP2 and β-actin antibodies.

Assays for triglyceride (TG) synthesis and degradation

Impacts of the ORP2–VAPA BiFC complexes or ORP2, VAPA, and VAPB silencing on TG synthesis or degradation in HuH7 cells were assayed by pulse labeling with [3H]oleic acid essentially as described in [57]. In short, the ORP2, VAPA and/or VAPB were either knocked-down or overexpressed in cells cultured in 12 wells as specified above. To examine the TG synthesis [3H]oleic acid [3.5 μCi per well (64 nM, 54.6 Ci/mmol), PerkinElmer, Boston, MA, USA] was added to the cells for 1.5 and 3 h, after which cells were washed two times with PBS and scraped into 2 % NaCl. When assaying the TG degradation, the cells were incubated overnight with [3H]oleic acid (3.5 μCi per well), washed three times with EMEM and once with PBS, and the 0 time point samples were collected. TG hydrolysis was induced by adding chase medium (antibiotic free EMEM with 5 % delipidated serum). After a 6-h chase, cells were scraped into 2 % NaCl, lipids were extracted using the Bligh and Dyer [58] method and [3H]TGs separated by thin layer chromatography (TLC). The radioactivity in TGs was assayed by liquid scintillation counting of scraped TLC spots and normalized to total cellular protein (BCA assay, Thermo Scientific/Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA).

Fluorescence microscopy of yeast cells

Yeast cells were grown as described previously [59]. For fluorescence microscopy, yeast cells Y1/NY179 (MATa leu2–3,112 ura3–52 [60]) were transformed with the BiFC plasmids and cultured in SC-ura-leu medium at the permissive temperature (30 °C). Cells were observed at OD600 0.8–1 using a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope with an ECPlnN 63×/1.4 Oil DICII objective and Colibri laser. Images were recorded with the Axio Vision Rel. 4.8.1 software (Carl Zeiss Imaging Solutions GmbH). The exposure time for the Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation of YFP was 3 s. Quantifications of the signal intensities were done with the original images obtained with the same microscope and the same exposure time. The interaction intensities were quantified by measuring the mean gray value of a same-sized box surrounding the cells using ImageJ 1.42. For each condition, the signals in at least 30 cells were quantified. The significance of the results was evaluated with Student’s t test (two-tailed, independent). Image panels were prepared using Adobe Photoshop7 software.

Results

FFAT motif containing ORPs interacts with VAP proteins at specific subcellular sites

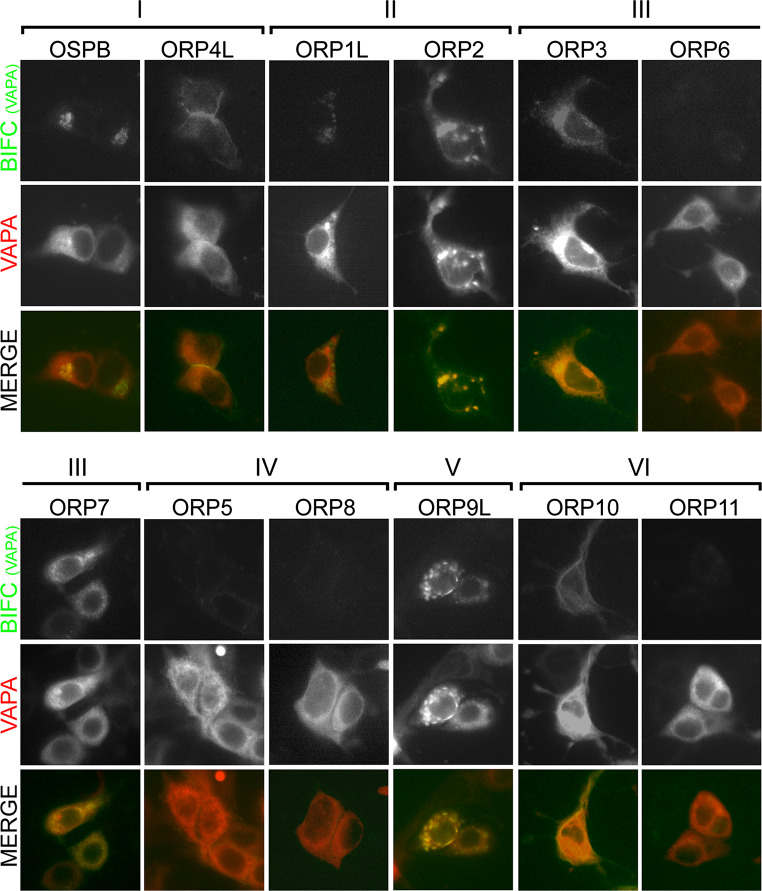

Eight out of the twelve human ORP proteins contain a FFAT motif, which mediates interactions with the type II integral ER proteins VAPA and VAPB [13]. To investigate the spatial occurrence of these interactions, we employed the Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) technique, which allows the visualization of protein proximity in living cells, with the fluorescence intensity varying according to the protein interaction strength [61]. HuH7 cells were transfected with N-terminal Venus fragment fused to the ORPs (VnORP) and C-terminal Venus fragment fused to the VAPs (VcVAP), and the BiFC fluorescence arising upon ORP–VAP interaction was monitored. Similar BiFC interactions with VAPA and VAPB were observed for the FFAT motif containing ORPs: OSBP, ORP4L, ORP1L, ORP2, ORP3, ORP7 and ORP9L (Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. S1). At the same time no significant BiFC interaction was observed for ORP5, -6, -8 and -11, of which only ORP6 contains a FFAT motif. The lack of detectable ORP6–VAP BiFC interaction is most likely due to the very low-expression levels of ORP6 achieved in the transfected HuH7 cells (data not shown). Surprisingly, the non-FFAT motif containing ORP10 showed a clear BiFC signal with VAPA and -B. However, this interaction appeared to be indirect, as it could not be reproduced in pull-down experiments (data not shown). Additionally, it was noted that most ORPs interact with VAP proteins at distinct, restricted locations within the cell, and not evenly throughout the ER like the mCherry-VAPA employed as a cotransfection marker (Fig. 1). Further evidence for the specificity of the BiFC interactions observed was provided by the fact that mFFAT motif point mutants of the ORPs, which showed severely reduced VAPA binding in pull-down assays (Fig. 2a, b), also displayed drastically reduced BiFC signals as compared to the wild-type (wt) ORPs (Fig. 3). Collectively, these data show that specific interactions of FFAT motif containing ORPs with VAP proteins occur at distinct sites specified by the ORP partner.

Fig. 1.

FFAT motif containing ORPs interact with VAPA at specific intracellular sites. Fluorescence imaging of HuH7 cells expressing different VnORP constructs in combination with VcVAPA and mCherry-VAPA (transfection marker). The BiFC signals indicating physical interaction/proximity between the ORPs and VAPA are shown in the top row, and merge of the BiFC and mCherry-VAPA fluorescence in the bottom row. The Roman numerals at the top refer to the ORP subfamilies [7]

Fig. 2.

The ORP–VAPA interaction strength is negatively regulated by oxysterol binding. a Oxysterol-binding deficient 4-aa deletion mutant ORP proteins (ELSK, ELSR, DLTK) show enhanced interaction with VAPA. HuH7 cells expressing different VnORP constructs were lysed and subjected to GST-VAPA pull-down. Cell lysates and pull-downs were analyzed by western blotting with anti-GFP antibodies. The GST-VAPA band was visualized as an unspecific band cross-reacting with the secondary antibody. The VAP-binding deficient ORP(mFFAT) mutants were used as negative controls. b Quantification of three repeats in a. Shown are averages and standard deviations; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.005. c ORP2 binding to VAPA in vitro is reduced by 22(R)OHC. Vehicle or 5 µM 22(R)OHC pretreated ORP2 (0.4 µM) was mixed with equal amounts GST-VAPA(658–724) or GST and subjected to pull-down with GSH-Sepharose. Bound proteins were separated on SDS–PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. GST served as a negative control. d Quantification of four repeats in c. Shown are averages and standard deviations; **p < 0.01

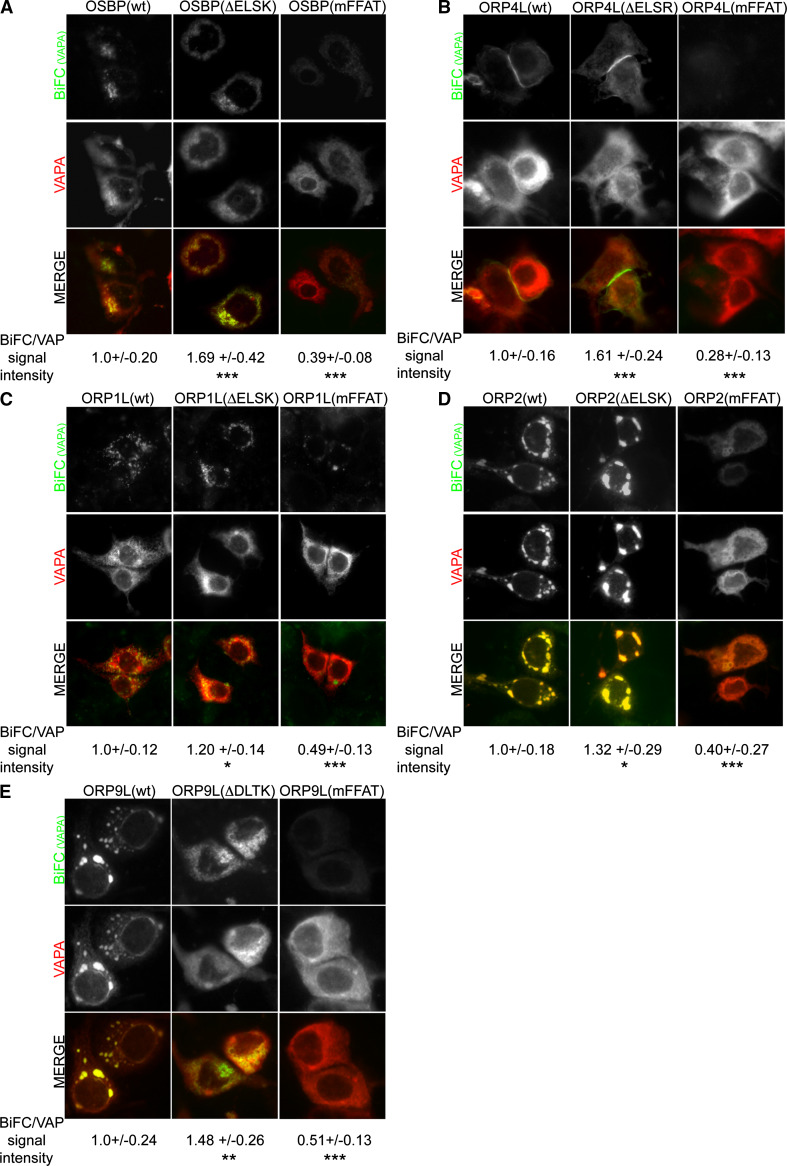

Fig. 3.

The ORP–VAPA BiFC interaction strength and localization are modulated by oxysterol binding to ORPs. Fluorescence imaging of HuH7 cells expressing different mutant VnORP constructs [OSBP (a), ORP4L (b), ORP1L (c), ORP2 (d) and ORP9L (e)] in combination with VcVAPA and mCherry-VAPA. BiFC signal intensities were analyzed in a minimum of 100 cells per condition and normalized to the cotransfection marker mCherry-VAPA. Shown are BiFC signal intensity averages and standard deviations; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.005

The ORP–VAPA interaction strength is negatively regulated by sterol binding

Like OSBP, many ORPs bind to oxysterols and/or cholesterol as their ligands [30, 57, 62–64]. The effect of this sterol binding on ORP–VAP interactions was investigated using previously established sterol-binding deficient ORP mutants, which have a four-amino acid deletion (ΔELSK, ΔELSR, or ΔDLTK) in the ligand-binding domain [30, 62, 64, 65]. Analyses of the ORP–VAPA interaction strength by pull-down assays showed that VAPA pulled down 29–110 % more of the sterol-binding deficient ORP mutants as compared to the respective wt ORPs (Fig. 2a, b). This phenomenon was observed for all VAPA-interacting ORPs of the subfamilies I, II and V [7], suggesting a conserved negative regulation of ORP–VAPA interactions by sterol liganding.

To investigate whether the sterol dependence of ORP–VAP interaction results from direct binding of oxysterol to the ORP, we produced ORP2 and VAPA for in vitro pull-down assays with purified proteins. ORP2 was preloaded with the high-affinity ligand 22(R)hydroxycholesterol [22(R)OHC, K d 1.4 × 10−8 M] [57] or treated with the vehicle (ethanol), followed by pull-down with beads coated with GST-VAPA or GST. The 22(R)OHC preincubation reduced the efficiency of ORP2 pull-down by VAPA significantly, by 60 % (Fig. 2c, d), while preincubation with the low-affinity ligand 25OHC (K d 3.9 × 10−6 M) [63] had in similar experiments no significant effect (data not shown). These findings demonstrate that binding of an oxysterol ligand directly reduces the affinity of ORP2 for VAPA.

The ORP–VAPA BiFC interaction in live cells is modulated by oxysterol binding

To investigate whether sterol ligand binding to ORPs also controls their interaction with VAPA in live cells, we employed the BiFC technique in HuH7 cells. Consistent with the pull-down results (Fig. 2), a significant enhancement of VAPA BiFC interaction was observed for all of the sterol-binding deficient (ΔELSK, ΔELSR, ΔDLTK) ORP mutants studied, OSBP, ORP4L, ORP1L, ORP2, and ORP9L (Fig. 3).

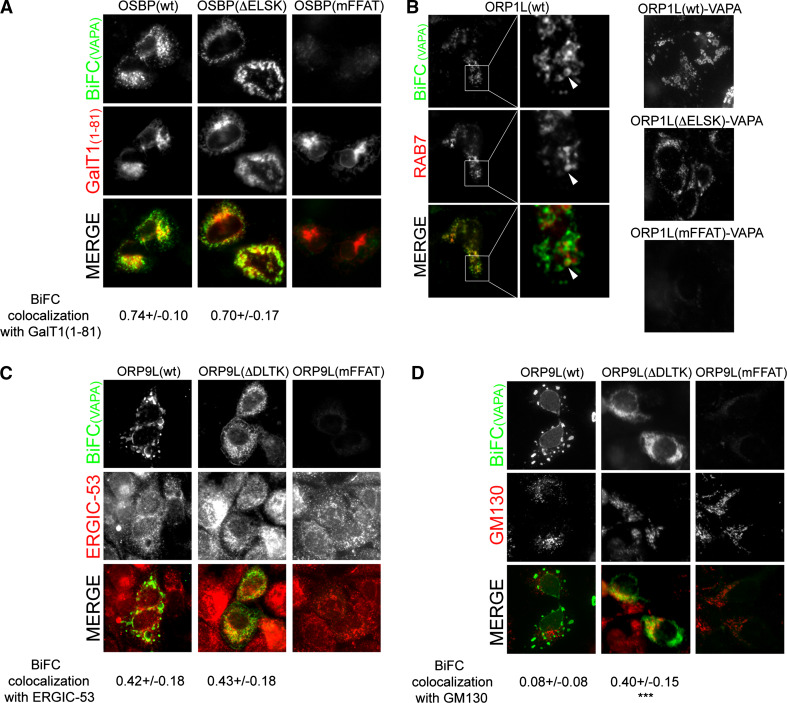

Interestingly, we noted that the ligand-bound status of the ORP proteins did not only affect the VAPA BiFC interaction strength, but also the ORP–VAPA BiFC interaction site in some cases. The OSBP–VAPA interaction site, which colocalized with the Golgi complex marker GalT1(1–81), appeared more widely distributed/scattered with the non-sterol-binding OSBP(ΔELSK) mutant than with the wt OSBP, reflecting apparent fragmentation of the Golgi (Figs. 3a, 4a) [66–67]. Also the ORP1L–VAPA interaction site surrounding Rab7-positive LEs changed in appearance, the ORP1L(ΔELSK)–VAPA BiFC-positive ring structures being smaller than for the wt ORP1L (Figs. 3c, 4b) [30]. However, the most dramatic distribution change was observed for ORP9L. While the ORP9L(wt)–VAPA BiFC interaction site appeared as prominent dots, blobs and perinuclear lines, the ORP9L(ΔDLTK)–VAPA interaction site had a Golgi-like appearance with an additional reticular ER aspect (Fig. 3e). Colocalization studies with the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment marker ERGIC53 (Fig. 4c) and the Golgi complex marker GM130 (Fig. 4d) revealed that (1) the morphology of these organelles themselves was unaffected by the ORP9L–VAPA BiFC construct expression and (2) confirmed that ORP9L(ΔDLTK)–VAPA BiFC interaction occurs, in addition to the ER, at the Golgi complex, while that of wild-type ORP9L and VAPA did not coincide with GM130 (Fig. 4c, d). Quantification of the colocalization revealed a marked increase in the overlap of ORP9L(ΔDLTK)–VAPA complexes with GM130 as compared to ORP9L(wt)–VAPA, while no difference was detected in their colocalization with ERGIC53. The ORP9L(wt)–VAPA interaction sites displayed intense fluorescence of the cotransfection marker mCherry-VAPA, suggesting that they represent modified ER structures arising upon expression of the ORP9L and VAPA BiFC constructs.

Fig. 4.

The ORP–VAPA BiFC interaction site is dependent on sterol binding. a Fluorescence imaging of HuH7 cells expressing the indicated VnOSBP constructs and VcVAPA. The Golgi complex was visualized by cotransfecting mCherry-GalT1(1–81). Colocalization efficiencies were analyzed in a minimum of 20 cells per condition. Shown are averages with standard deviations. b Fluorescence imaging of HuH7 cells expressing VnORP1L, VcVAPA and RFP-Rab7. Arrowheads point at a Rab7-positive endosome encircled by ORP1L-VAPA BiFC signal. Further BiFC images of ORP1L(wt)–VAPA and the indicated mutants are shown on the right. c Fluorescence imaging of HuH7 cells expressing the indicated VnORP9L constructs and VcVAPA. The ER–Golgi intermediate compartment was stained with anti ERGIC-53/p58 antibody. Colocalization efficiencies were analyzed in a minimum of 25 cells per condition. Shown are averages with standard deviations. d Oxysterol-binding deficient ORP9L(ΔDLTK)–VAPA complexes colocalize with the Golgi complex. Experiment was performed as in c, except that the Golgi complex was stained with anti GM130 antibody. **p < 0.005

Mutations in the inositol-phosphate-binding cleft of the ORP2 and ORP4L ORDs do not enhance VAP binding

The ligand-binding pocket in the ORD of ORPs can, besides sterols, binds a phosphoinositide (PI4P), as shown for yeast Osh3p [68], Osh4p [53] and human OSBP [4]. Structural analyses and point mutations in ORD residues conserved throughout the eukaryotic kingdom have delineated an inositol-phosphate-binding cleft [4, 53]. We generated in ORP2 and ORP4L a PIP-binding deficient triple point mutation (mPIP) established in the earlier studies, and compared the interaction of the mutant and wild-type proteins with VAPA by employing pull-down and BiFC assays similar to those applied for the sterol-binding deficient and mFFAT mutant proteins above. The pull-down assays revealed a significant reduction of ORP4L(mPIP) binding to VAPA as compared to the wt protein, and the corresponding mutation in ORP2 showed a similar trend (Supplementary Fig. S2A, B). Likewise, analysis of BiFC signal intensities with VAPA in transfected cells revealed a reducing trend, which, however, did not reach statistical significance, for the ORP2 and ORP4L mPIP mutants (Supplementary Fig. S2C, D).

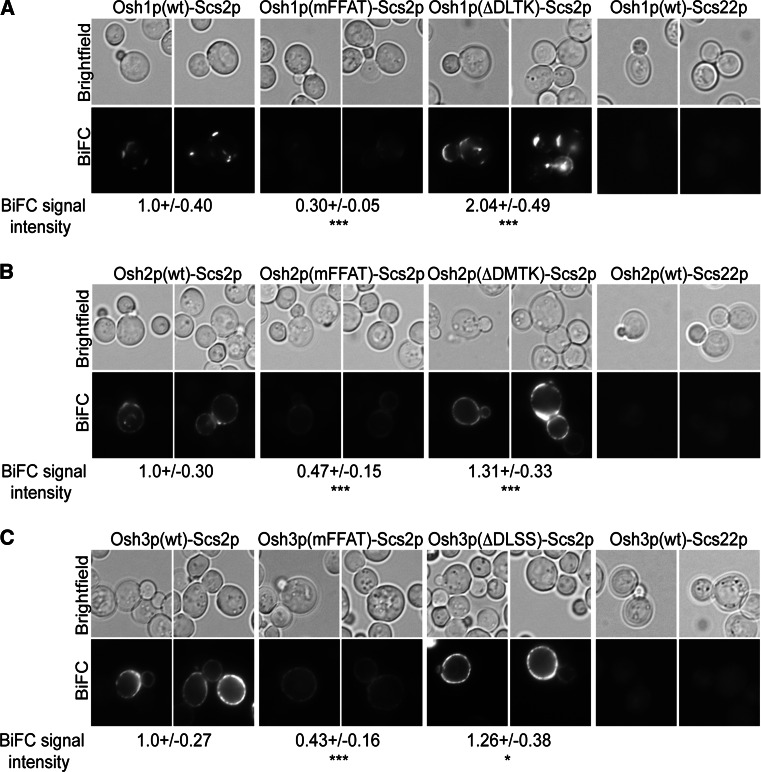

Interactions of the yeast Osh proteins with Scs2p occur at specific subcellular sites and are regulated by sterol binding

In the yeast S. cerevisiae there are seven OSBP homologs (Osh) proteins. Of these, Osh1p, Osh2p and Osh3p possess a FFAT motif suggesting that they interact with the yeast VAP orthologs Scs2p and -22p [10]. We employed the BiFC technique to examine the localization of the Osh1p–3p–Scs2p/22p interaction sites in living cells. The Osh1p–Scs2p BiFC interaction localized to dotty structures and short lines representing nucleus–vacuole junctions (NVJs) as revealed by vacuole staining with FM4–64 (data not shown), similar to the localization previously reported for GFP-Osh1p (Fig. 5a; [25]). Both the Osh2p–Scs2p and Osh3p–Scs2p BiFC signals localized to patches at the plasma membrane. The Osh2p–Scs2p signal was in occasional cells and also detected on intracellular structures representing the nuclear envelope (Fig. 5b). Mutation of the FFAT motif in the Osh proteins resulted in a marked reduction of the Osh1p–3p(mFFAT)–Scs2p BiFC, confirming the specificity of the signals (Fig. 5). Interestingly, no BiFC was observed for Osh1p, -2p or -3p with Scs22p, the Scs2p homolog in yeast (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The yeast Osh proteins interact with Scs2p at specific intercellular sites and are regulated by sterol binding. Fluorescence imaging of wt yeast cells (Y1) expressing a YnOsh1p(wt, mFFAT or ΔDLTK), b YnOsh2p(wt, mFFAT or ΔDMTK) and c YnOsh3p(wt, mFFAT or ΔDLSS) together with YcScs2p/22p. BiFC signal intensities were analyzed in a minimum of 30 cells per condition. Shown are signal intensity averages and standard deviations; *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.005

To understand the effect of ORD ligand binding on the yeast Osh1–3 proteins, we generated the corresponding four amino acid deletions (ΔDLTK, ΔDMTK, ΔDLSS), which have been shown to reduce sterol binding by several mammalian ORPs [30, 62, 64, 65]. Similarly to the mammalian ORPs, Osh1p–3p(ΔDLTK, ΔDMTK, ΔDLSS) showed a 26–104 % increase in BiFC signal with Scs2p (Fig. 5). Additionally, the Osh1p(ΔDLTK)–Scs2p interaction site shifted towards the growing bud and septum in yeast (Fig. 5a). These results suggest a conserved functional impact of ORD ligand binding by the Osh/ORP proteins in yeast and mammals.

ORP2–VAPA complexes associate with and wrap lipid droplets (LD) in ER membranes in an oxysterol-dependent manner

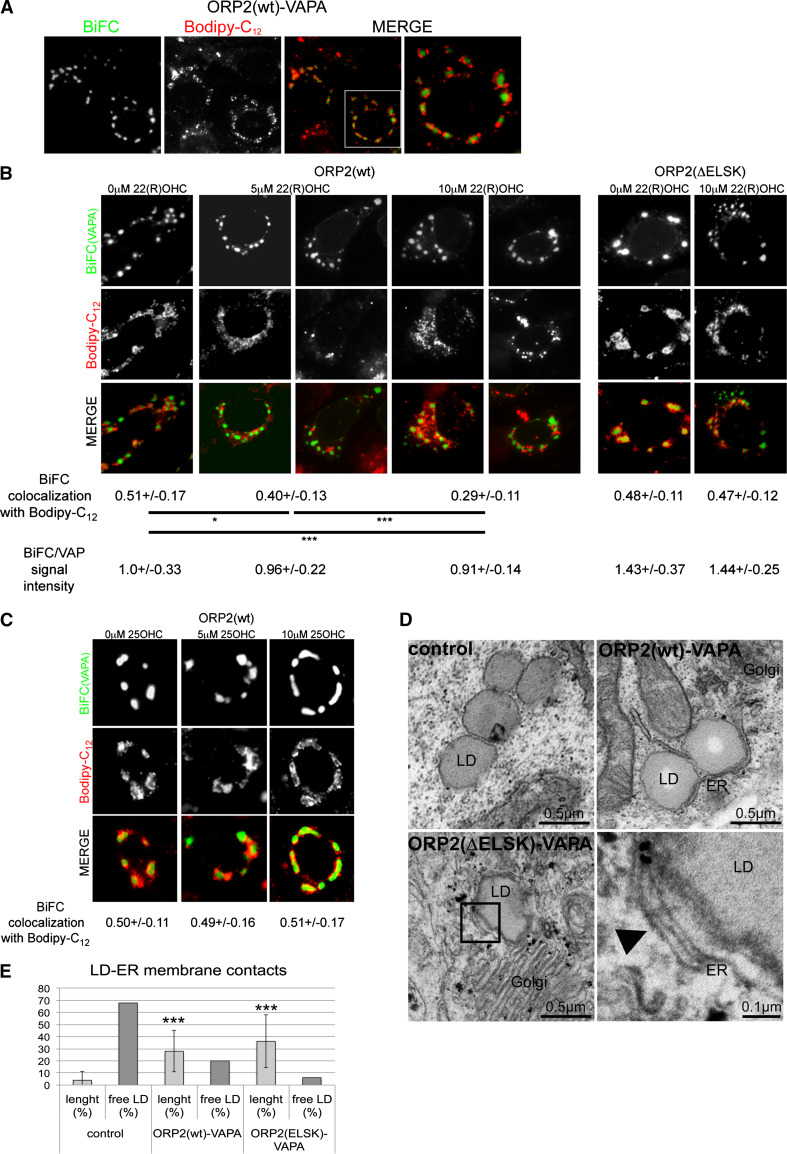

ORP2 has previously been shown to bind 22(R)OHC with high affinity and to reside on the surface of LD [57]. Contrary to this ORP2 localization observed when the protein was overexpressed alone, the ORP2–VAPA BiFC interaction site did not decorate LD, but was rather found on mCherry-VAPA-positive (ER) patches surrounded by LD clusters (Figs. 1, 6a). This finding suggests that the ORP2–VAPA BiFC interaction site represents ER domains that make specific contacts with LD.

Fig. 6.

ORP2–VAPA complexes wrap lipid droplets in ER membranes in an oxysterol-dependent manner. a Fluorescence imaging of HuH7 cells expressing VnORP2 in combination with VcVAPA. Lipid droplets were stained with Bodipy-C12. The rightmost panel shows a high-magnification view of a cell indicated with a white frame. b Fluorescence imaging of HuH7 cells expressing VnORP2(wt or ΔELSK) in combination with VcVAPA. Lipid droplets were stained with Bodipy-C12. The effect of sterol binding was assayed by treating the cells with the vehicle (ethanol) or 5 or 10 µM 22(R)OHC. Colocalization efficiencies were analyzed in a minimum of 25 cells per condition. Additionally, the ORP2–VAPA BiFC signal intensities were analyzed in a minimum of 100 cells per condition, which were cotransfected with mCherry-VAPA (for normalization of the BiFC signal) and treated as above. Shown are colocalization and BiFC signal intensity averages and standard deviations; *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.005. c Experiment was performed as in b, except that 25OHC was used. d Transmission electron microscopy images of HuH7 cells expressing either the empty vectors (control) or VnORP2(wt or ΔELSK) in combination with VcVAPA. In the case of ORP2(ΔELSK), double wrapping of a lipid droplet (LD) with ER membranes is indicated by the arrowhead in the high-magnification inset. e Quantification of LD–ER membrane contacts in d. Shown are averages and standard deviations of the relative total length of LD–ER membrane contacts and the amount of free LDs of a total of 50 LDs analyzed per condition; ***p < 0.005

Addition of 5 or 10 µM 22(R)OHC released in a dose-dependent fashion the LD from the ORP2–VAPA BiFC-positive structures within 6 h, as shown by reduced Pearson correlation coefficient for colocalization of the BiFC and the LD stain (Fig. 6b, left panel, 5 and 10 µM). After oxysterol treatment, an increased proportion of the LDs was seen free in the cytoplasm. It is plausible that the reduction of colocalization is due to detachment of ORP2 from the lipid droplet surface [57]. To further confirm this we carried out BiFC experiments using the sterol-binding deficient ORP2(ΔELSK) mutant. The colocalization of the ORP2(ΔELSK)–VAPA BiFC signal with the LD stain was unaffected by 22(R)OHC, strongly supporting the view that sterol ligand binding to ORP2 induces release of the LDs from the ORP2–VAPA interaction sites (Fig. 6b, right panel). Furthermore, the capacity of ORP2(wt)–VAPA BiFC complexes to cluster LDs was unaffected by the addition of 25OHC (Fig. 6c), an oxysterol with a low, micromolar affinity for ORP2 [63]. Of note, 24-h incubation with 10 µM 22(R)OHC also resulted in a marked (33 %) reduction of ORP2–VAPA BiFC signal intensity, consistent with the notion that oxysterol liganding dampens the ORP–VAP interaction (data not shown). Collectively, these results suggest that the ORP2–VAPA interaction sites represent membrane contacts between LD and the ER and that these contact sites are negatively regulated by the high-affinity ORP2 ligand 22(R)OHC.

To visualize the ultrastructure of the putative ER–LD contact sites, we performed transmission electron microscopy of HuH7 cells transfected with the empty vector (control) or the ORP2 and VAPA BiFC constructs. In control cells, LDs were mainly observed free in the cytosol and only seldom in association with ER membranes (32 %, Fig. 6d, e, control). In ORP2(wt)–VAPA-transfected cells, LDs were mainly seen in association with the ER (80 %), fully consistent with the BiFC observation that ORP2–VAPA complexes cluster LDs at ER sites (Fig. 6d, e, ORP2(wt)–VAPA). Upon ORP2(ΔELSK)–VAPA BiFC construct expression, about 10 % of LDs were found wrapped by two layers of ER, suggesting that ORP2(ΔELSK)–VAPA BiFC complexes not only enhance ER–LD contact site formation but can also promote piling of ER cisternae on top of each other (Fig. 6d, ORP2(ΔELSK)–VAPA and arrowhead). EM observation of the ORP2–VAPA (Fig. 6D) and ORP9L–VAPA (Supplementary Fig. S3)-expressing cells with patch- or blob-like ER structures observed under fluorescence microscopy failed to detect liquorice-roll-like or extensively stacked organized smooth ER (OSER) structures or cubic phase-like membranes. The EM findings thus suggest that the brightly stained fluorescent structures rather represent ER tubules and sheets, which sometimes appear swollen (ORP9L–VAPA; Supplementary Fig. S3). The BiFC-positive ER structures induced by ORP2– and ORP9L–VAPA are most likely exaggerated by overexpression of the ORP–VAP complexes, but we surmise that their functional properties resemble those of the ER domains that in untransfected cells harbor the endogenous ORP–VAP complexes.

ORP2–VAPA complexes cause accumulation of lipid droplet clusters close to the nucleus

Prompted by the observation that LDs were found clustered around the ORP2–VAPA BiFC-positive structures, we quantified the number of LDs in cells transfected with the empty BiFC vectors (control), or the VAPA together with ORP2(wt) or ORP2(ΔELSK) BiFC constructs. This analysis revealed that both ORP2(wt)–VAPA and ORP2(ΔELSK)–VAPA complexes induced a significant reduction in the number of individual LD clusters per cell (Fig. 7a, b). As also evident upon visual inspection of the LDs (Fig. 7a), the size of the LD clusters observed in the cells was increased. While this was a tendency in cells expressing ORP2(wt) and VAPA BiFC constructs, it reached statistical significance in ORP2(ΔELSK)–VAPA-transfected cells (Fig. 7c). While the LDs were evenly dispersed throughout the control cells, they were in ORP2(wt or ΔELSK)–VAPA-expressing cells organized as a ring around the nucleus, associated with the BiFC signal sites (Fig. 7a, d). The above findings, together with the EM observations (Fig. 6d), are consistent with the view that ORP2–VAP BiFC complexes induce the accumulation of LD clusters at specific ER sites where ORP2 bound to VAP bridges between the ER and the LDs. Cells expressing the inositol-phosphate-binding cleft mutant (mPIP) of ORP2 displayed ORP2–BiFC-positive structures which were somewhat more dispersed than the wt ORP2–VAPA elements, the mean distance from the nucleus being slightly higher than for wt ORP2. The ORP2(mPIP)–VAPA structures had LDs associated with their surface, with no difference in total LD area observed between the mutant and wt ORP2–VAPA (Supplementary Fig. S4). One putative explanation for the morphologic difference of the wt and mPIP ORP2–VAPA BiFC elements could be a reduced affinity of ORP2(mPIP) for VAPA (see Supplemental Fig. S2).

Fig. 7.

ORP2–VAPA overexpression causes lipid droplet cluster accumulation and inhibits TG hydrolysis. a Fluorescence imaging of HuH7 cells expressing either the empty vectors (control) or VnORP2(wt or ΔELSK) in combination with VcVAPA. Lipid droplets (LD) were stained with Bodipy-C12 and the nuclei with Hoechst. b The amount of separate LD clusters is decreased in ORP2(wt or ΔELSK)–VAPA-expressing cells. LD cluster number was analyzed in a minimum 20 cells per condition. Shown are averages and SEM. ***p < 0.005. c The total LD area is increased in ORP2(wt or ΔELSK)–VAPA-expressing cells. LD total area was analyzed in a minimum of 20 cells per condition. Shown are averages and SEM. *p < 0.05. d The LD distribution is altered in ORP2(wt or ΔELSK)–VAPA-expressing cells. LD distribution was analyzed in a minimum of 10 cells per condition. The center of the nucleus was used to define the cell center. Shown are averages and SEM. e Triglyceride synthesis (labeling with [3H]oleic acid) is not affected by ORP2–VAPA overexpression. Shown are averages and SEM of three replicates repeated twice. f ORP2–VAPA overexpression blocks [3H]TG hydrolysis upon 6-h lipid starvation. Shown are averages and SEM of three replicates repeated twice

ORP2–VAPA complexes inhibit triglyceride (TG) hydrolysis

To investigate, by employing a biochemical approach, the putative impacts of ORP2–VAPA complexes on TG metabolism at lipid droplets, we carried out in HuH7 cells a series of experiments in which the effects of ORP2–VAPA overexpression on the synthesis and hydrolysis of [3H]oleate-labeled TGs were measured. In these experiments, employing a low concentration of radioactive oleate the rationale was to assess effects on TG synthesis under basal culture conditions (no fatty acyl loading, which overrides subtle regulatory mechanisms, was employed). During a 3-h time course of [3H]oleate labeling of the newly synthesized TG, the ORP2(wt) and ORP2(ΔELSK) BiFC constructs coexpressed with VAPA had no effect on [3H]TG synthesis (Fig. 7e). However, when the cellular TG were labeled overnight with [3H]oleate, followed by a 6-h incubation in medium containing delipidated serum to stimulate TG hydrolysis (which is hardly detectable under basal culture conditions), the ORP2(wt) and ORP2(ΔELSK) BiFC constructs caused a significant inhibition of [3H]TG hydrolysis, whereas the mFFAT mutant defective in VAPA interaction had no effect (Fig. 7f). These findings suggest that ORP2–VAPA complexes may couple the LDs to a region in the cell where TG synthesis can occur, while TG hydrolysis is inhibited, and is well in line with the observation that lipid droplets appear to grow/accumulate in these cells (Fig. 7c). Although the ORP2(ΔELSK) mutation enhances the VAP interaction of ORP2 and the mutant couples the LD to ER elements at least as (or more) efficiently than the wt protein, the biochemical assays for HuH7 cell TG metabolism revealed no significant differences between the wt protein and this mutant. We find it plausible that the overexpressed ORP2(wt)–VAPA complexes which are, furthermore, stabilized by interaction of the Venus fragments [61], have such a strong impact that no additional mutant effect can be detected.

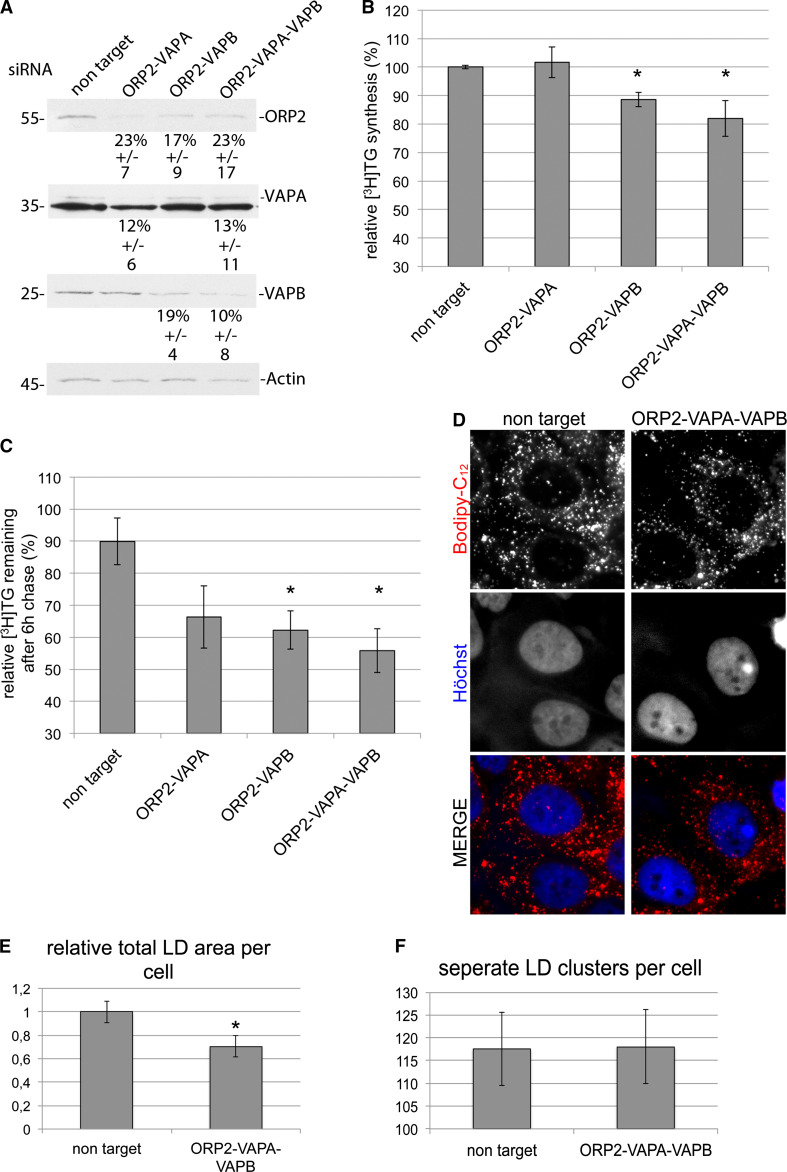

ORP2–VAP silencing reduces the synthesis and enhances the hydrolysis of TGs

We next moved on to investigate the involvement of the endogenous HuH7 cell ORP2 and VAPA/B in the synthesis and hydrolysis of [3H]TGs by employing an RNAi approach. ORP2, VAPA or VAPB knock-down resulted in a marked reduction of the endogenous proteins as determined by Western analysis (Fig. 8a). While ORP2–VAPA knock-down had no effect on [3H]TG synthesis, silencing of ORP2–VAPB reduced [3H]TG synthesis significantly by 11 %. Triple silencing of ORP2–VAPA–VAPB further reduced [3H]TG synthesis (by 18 %, Fig. 8b). This finding supports the notion that also endogenous ORP2–VAP complexes couple LDs to ER domains where TG synthesis is facilitated. In line with the overexpression results (Fig. 7f), double knock-down of ORP2–VAPA or ORP2–VAPB resulted in a 26 or 31 % enhancement of [3H]TG hydrolysis, respectively (Fig. 8c). The effect was even further enhanced (38 %) by triple silencing of ORP2–VAPA–VAPB (Fig. 8c).

Fig. 8.

ORP2–VAP silencing reduces TG synthesis and enhances TG degradation. a A representative western blot showing the silencing efficiencies of ORP2, VAPA and VAPB. The % indicates relative amounts of the remaining proteins in three independent experiments. The strong band visible underneath VAPA represents an unknown protein cross-reactive with the VAPA antibody. b Triglyceride synthesis (labeling with [3H]oleic acid) is reduced in ORP2–VAP-silenced cells. Shown are averages and SEM of three replicates repeated twice. c [3H]TG hydrolysis is enhanced in ORP2–VAP-silenced cells. Shown are averages and SEM of three replicates repeated three times. d Fluorescence imaging of HuH7 cells silenced with non-target or ORP2–VAPA–VAPB siRNAs. Lipid droplets (LD) were stained with Bodipy-C12 and nuclei with Hoechst. e The total LD area is decreased in ORP2–VAPA–VAPB-silenced cells. LD total area was analyzed in a minimum of 20 cells per condition. Shown are averages and SEM. *p < 0.05. f The number of separate LD clusters is not affected by ORP2–VAPA–VAPB silencing. LD cluster number was analyzed in a minimum 20 cells per condition. Shown are averages and SEM

Staining of the LDs with Bodipy-C12 revealed that silencing of ORP2–VAPA–VAPB did not significantly affect the macroscopic distribution of the LDs in the cell (Fig. 8d). In line with the [3H]TG analysis, the total LD area was reduced by about 30 %, while the number of LD clusters was unaffected (Fig. 8e, f). The above findings provide evidence that the endogenous hepatocellular ORP2 and VAP proteins act to regulate the turnover of lipid droplet TG. It appears that ORP2–VAP complexes positively regulate TG synthesis, while they inhibit TG hydrolysis. The BiFC and EM results suggest that this function is mediated by ORP2–VAP complexes coupling LDs to specific sites at the ER where TGs are synthesized, while in cells with reduced amounts of ORP2–VAP proteins the LD are free to move to regions where TG hydrolysis is facilitated.

Discussion

In the present study, we provide evidence that the complexes of FFAT motif containing human and S. cerevisiae ORPs with their ER anchors, the VAP/Scs2 proteins, concentrate at spatially restricted subcellular locations and are subject to regulation by ORD liganding of the ORPs. Most of the ORPs studied bind sterols within their ORD. However, it is important to note that certain family members are likely unable to bind sterols, as suggested by structural/biochemical data on yeast Osh3p [68], Osh6p [69], and by a homology model of human ORP3 [70]. A deletion of four amino acids in the ligand-binding domain lid structure, to abolish sterol binding, enhanced the interaction between the ORP proteins studied and VAPA. Additionally to the sterol binding, most or all ORPs were suggested to share the capacity to accommodate optionally a phosphoinositide (PIP) within their ORD [4, 53, 68]. We mutagenized three conserved residues in the inositol-phosphate-binding cleft of human ORP2 and ORP4L to generate a defect in PIP binding [4, 53]. Unlike the sterol-binding deficient mutants of these proteins, the PIP-binding mutants failed to display an enhancement of VAP interaction; instead, ORP4L(mPIP) had a reduced VAP-binding capacity and ORP2(mPIP) showed a similar trend. The result suggests that in these two sterol-binding ORPs, the effect of the 4-aa deletion is truly due to a defect in sterol interaction and not a hypothetical PIP-binding defect. This conclusion is supported by the recent data of Liu and Ridgway [71], who showed that the 4-aa deletion mutant of ORP9L does not disturb PI4P binding by this protein. Moreover, the results obtained with the mPIP mutants indicate that the ORP–VAP interaction may be stimulated by sterol depletion and, if anything, inhibited by depletion of PIP. This would be consistent with the functional model of Mesmin et al. [4] suggesting bidirectional (exchange type) transport of cholesterol and PI4P between ER and trans-Golgi membranes by OSBP.

Our BiFC and EM results suggest that the ORP–VAP interaction sites in several cases represent membrane contacts (MCSs), at which ER membranes are closely apposed with other organelle limiting membranes. Using the complex of ORP2 with VAPs as an example, we provide functional evidence for a role of ORP–VAP complexes and the MCSs at which the complexes are localized, in the control of cellular lipid metabolism, in this case in the synthesis and hydrolysis of triglycerides stored in cytoplasmic lipid droplets.

In most cases, our BiFC analysis reflects a direct interaction of the ORP and VAP partners, as evidenced by pull-down experiments. The only exception is the BiFC signal observed for VAPs and ORP10, which lacks a FFAT motif. Emission of BiFC signal is reported to occur when the fluorescent protein fragments are spaced at a maximum distance of 10 nm [61]. The ORP10–VAP BiFC signal was observed on microtubules, for which both ORP10 [72, 73] and VAPs [19, 74] show affinity. One can envision that the two proteins pack on the surface of microtubules at a proximity close enough to produce a BiFC signal. While the ER labeled by the cotransfection marker mCherry-VAPA extends throughout the cellular cytoplasmic compartment, many of the ORP–VAP BiFC signals concentrated in spatially restricted locations. Good examples of this are the Golgi-like distributions of OSBP(wt)–VAPA BiFC and ORP9L(ΔDLTK)–VAPA BiFC, the ORP1L–VAPA signal focused at ER elements encircling late endosomes, the ORP4L–VAPA BiFC focusing at cell–cell contacts, and the ORP2–VAPA BiFC localizing at patch- or blob-like modified ER structures to which LD were attached. Why do the BiFC signals in several cases show such a restricted distribution? One potential explanation is that targeting of the different ORPs to distinct non-ER organelles via the PH domain regions (OSBP, ORP1L, ORP4L, ORP9L; [75–77]) or determinants present on the OSBP-related ligand-binding (ORD) domain (ORP2, which lacks a PH domain; [7]), determines the location of the ORP–VAP interaction, possibly contributing to the formation of a MCS, as our data on ORP2 and VAPA at the ER–LD interface indicate. On the other hand, one can envision that a pre-existing MCS may concentrate ORPs at the interface of two compartments due to increased avidity of ORP binding at such sites via dual interactions with VAPs at the ER and phosphoinositides in the cognate non-ER membrane [78].

What is the functional role of ORP–VAP complexes at MCSs? MCSs have in different cell types a number of documented functions, mainly in the synthesis or intra-organelle transport of lipids or as sites controlling calcium fluxes [28, 33, 35, 36]. By simultaneous binding of VAPs and the late endosomal GTPase Rab7 human ORP1L was shown to generate ER–LE junctions which control the motility and distribution of the LE, also with impacts on the transport of endocytosed cholesterol [26, 30]. The present data are fully in line with these observations, demonstrating ORP1L–VAP BiFC at ER structures encircling Rab7-positive LE. The smaller size of the ring-like BiFC signals of ORP1L(ΔELSK)–VAPA is consistent with a scattered distribution of LE and lack of LE clustering in cells expressing this sterol-binding deficient mutant ORP [30] or a mutant lacking the entire ORD [26]. OSBP has been demonstrated to regulate ceramide transporter (CERT) activity at ER–trans-Golgi contacts, thus controlling in a sterol- and PI4P-specific manner the synthesis of sphingomyelin [65, 79]. Moreover, the most recent findings suggest a function of OSBP as a bidirectional transporter of cholesterol and PI4P at ER–trans-Golgi MCSs [4]. Of note, our BiFC analysis localized OSBP–VAP complexes to perinuclear Golgi membranes, in agreement with a function in lipid transport at the ER–Golgi interface. This was observed in the absence of oxysterol treatment, suggesting that the endogenous sterol ligands of OSBP together with PI4P are sufficient to maintain part of the OSBP–VAP complexes at a Golgi (or ER–Golgi MCS) location. Fragmentation of the Golgi was observed in cells expressing the sterol-binding deficient OSBP(ΔELSK)–VAP complexes. Similarly, Perry and Ridgway [65] showed this mutant to distribute to punctate peripheral and perinuclear structures where it colocalized with VAP, but the identity of structures was not clear. We find it likely that the non-sterol-bound OSBP mutant induces Golgi fragmentation (as evidenced by colocalization of the dispersed OSBP(ΔELSK)–VAP structures with GalT) as a result of (1) disturbed cholesterol transport to Golgi membranes [4, 65, 80] and/or (2) an elevated affinity for VAP at the ER membranes which may mediate attachment of Golgi elements to ER sites. Of note, Mesmin et al. [4] demonstrated by EM extensive interdigitation of ER membranes with the juxtanuclear Golgi in cells expressing OSBP in the presence of 25OHC. This most likely reflects enhanced Golgi targeting of OSBP–VAP complexes in the presence of the oxysterol ligand, but is not indicative of enhanced OSBP–VAP interactions.

Related to OSBP, ORP9L was identified as a cholesterol transfer protein associated with ER and Golgi membranes, which regulates Golgi structure/integrity and transport functions [62]. ORP9L(wt)–VAP complexes are observed at large, apparently abnormal ER elements while the sterol-binding deficient ΔDLTK mutant associates with normal-appearing ER and Golgi membranes; no Golgi fragmentation as with OSBP(ΔELSK)–VAP was evident. We find it plausible that the ORP9L(ΔDLTK) with elevated affinity for VAPA adopts an altered conformation which allows it to distribute in normal-appearing ER membranes and putative ER-Golgi MCSs. Thus, there seems to be a distinct difference in the sterol regulation of OSBP–VAP and ORP9L–VAP complexes. While both VAP interactions seem to be enhanced by the sterol-binding deficient mutants, the effects on organelle targeting and Golgi integrity are different: For OSBP, both the wt protein and the ΔELSK–VAP complexes colocalize with the trans-Golgi marker, either in a juxtanuclear or a scattered location, while the ORP9L(wt)–VAP complexes fail to target the Golgi, and ORP9L(ΔDLTK)–VAP does not disturb the integrity of the Golgi complex.

ORP4L–VAP complexes were strikingly concentrated at cell–cell contacts, the BiFC signal being intensified with the ORP4L(ΔELSR) mutant. ORP4L is essential for the proliferation and survival of several cell types, suggesting a crucial but as yet poorly understood signaling function [81, 82]. We, therefore, find it likely that the ORP4L–VAP complex is involved in the assembly or function of signaling machineries at ER–PM junctions underneath cell–cell contacts. Collectively, the observations on the sterol-binding deficient ORP mutants illustrate the regulatory potential of sterol liganding on the localization and function of ORP–VAP complexes.

In yeast, four ORP family proteins (Osh2p, -3p, -6p and-7p) were previously localized at ER–PM contact zones [27]. In addition, Osh1p was shown to target the nucleus–vacuole junction (NVJ; [24, 25]). Interestingly, yeast Osh3p and the VAP orthologs Scs2p and Scs22p were shown to control the activity of an ER enzyme, the phosphoinositide phosphatase Sac1p, on its PI4P substrate at the plasma membrane [31], as well as of the methyltransferase Opi3p which converts phosphatidylethanolamine into phosphatidylcholine in the PM [29]. Moreover, Schulz et al. [27] showed evidence that Osh4p, a yeast protein comprising an ORD only (with no PH domain), is able to simultaneously bind ER and plasma membrane vesicles by employing two distinct protein surfaces. Our findings on Osh2p and -3p–Scs2p complexes are consistent with the morphologic observations of Schulz et al. [27] but add the crucial information that the two Osh proteins associate with PM patches in complex with Scs2p, thus suggesting that the patches involve a protein–protein bridge between the ER and the PM. The Osh1p(wt)–Scs2p BiFC signal was observed at NVJ and dotty structures which most likely represent the Golgi at which Osh1p was previously shown to localize [24, 25]. Intriguingly, the Osh1p(ΔDLTK)–Scs2p complexes were deviated to the growing bud and the septum, sites at which secretory vesicle transport is directed [83], suggesting that non-sterol-bound Osh1p may have a function in polarized secretion, similar to Osh4p [84]. We could not detect significant interaction of the Osh proteins with Scs22p. This finding suggests that, while the human ORPs interact with both VAPA and -B isoforms, the functions of yeast Scs2p and -22p have diverged, Scs2p acting as the predominant ER anchor of the Osh proteins. In previous studies addressing the function of Scs2p and -22p in the context of Osh proteins, Loewen et al. [13] and Tavassoli et al. [29] employed a Δscs2 strain in which the targeting/function of Osh2p and Osh3p, respectively, was markedly defective, consistent with a major role of Scs2p as a partner of the Osh. Moreover, a functional distinction between the two genes was reported by Loewen and Levine [85], who observed that SCS2 was the dominant gene in the regulation of Opi1p, a transcriptional repressor controlling phospholipid biosynthesis.

The data suggesting a function of ORP2–VAP complexes in TG metabolism at the ER–LD interfaces provide important clues to ORP–VAP function at MCSs. In BiFC, pairing of the fluorescent protein fragments increases the stability of the complex of interacting fusion proteins. Therefore, the technique cannot be employed for dynamic studies on protein complex assembly and disassembly [61]. The ORP2–VAPA complexes detected are most likely stabilized by the BiFC fusion partners, which may have resulted in overestimation of the effects of the proteins on TG metabolism. However, our RNAi experiments strongly suggest that also the endogenous cellular ORP2 in complex with VAPs regulates LD neutral lipid turnover, putatively by controlling the distribution of LDs between ER domains mediating TG synthesis and other locations that rather favor their hydrolysis. This notion is consistent with the observation that central TG biosynthetic enzymes are distributed at ER sites that engulf LD [39], and that close contacts and continuities between ER and LDs mediate the transfer of TG synthesizing enzymes between the two organelles [40–42]. The present findings cannot be directly compared with the data of Hynynen et al. [57], who employed a different cell model (A431 epidermoid carcinoma cells) and targeted ORP2 alone with RNAi. Although there are distinct differences in the results of the two studies, both support a functional role of ORP2 complexes in the control of cellular TG metabolism. Future work is warranted to elucidate the roles of ORP2–VAP complexes in hepatocyte fatty acid oxidation or routing for very low-density lipoprotein assembly, as well as in adipocyte lipid storage.

Although the present study revealed differences among the ORP family members in ORD ligand-dependent subcellular targeting of the ORP-VAP complexes, evidencing for functional diversity within the family, it also unveiled certain common features, such as the enhancement of VAP interaction by ORD ligand-binding deficient mutants. Our results indicate that this is the case for sterol liganding of the ORPs known to bind sterols, but also for yeast Osh3p, which is apparently unable to bind sterols [68]. To assess the functional role of PIP binding by the ORD, we mutagenized the inositol-phosphate-binding cleft of ORP2 and ORP4L, revealing results distinct from the sterol-binding deficient mutants. This suggests that the sterol and PIP binding have different regulatory effects on ORP–VAP function, and is consistent with the bidirectional sterol/PI4P transport model suggested for OSBP by Mesmin et al. [4]. Why should ORP–VAP interactions be potentiated in the absence of bound sterol ligand, as suggested by our experiments with the sterol-binding deficient ORP mutants and pull-down assay with purified proteins? One plausible explanation may be the need to enhance communication between the ERs, responsible for most lipid synthetic processes, with other organelles in cells subject to lipid/sterol depletion. Under such conditions increased inter-organelle communication may secure sufficient organelle lipid supply from the ER, enhanced signal transmission, and organelle functionality.

In conclusion, the present data suggest evolutionarily conserved, complex ligand-dependent functions of ORP–VAP complexes at MCSs, with implications for cellular lipid homeostasis and signaling.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Fig. S1 FFAT motif containing ORPs interact with VAPB at specific sites in the cell. Fluorescence imaging of HuH7 cells expressing different VnORP constructs in combination with VcVAPB and mCherry-VAPB. The BiFC signals indicating physical interaction/proximity of the ORPs and VAPB are shown in the top row, and merge of the BiFC and mCherry-VAPB fluorescence in the bottom row. (TIFF 10164 kb)

Supplementary Fig. S2 Impact of inositol-phosphate-binding cleft mutations (mPIP) on the ORP–VAPA interaction. (A) HuH7 cells expressing the indicated wt or mPIP VnORP2 and VnORP4L constructs were lysed and subjected to GST-VAPA pull-down. Cell lysates and pull-downs were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-GFP antibodies. The GST-VAPA band was visualized as an unspecific band cross-reacting with the secondary antibody. (B) Quantification of three repeats of the experiment in (A). Shown are averages and standard deviations; *p < 0.05. (C and D) Fluorescence imaging of HuH7 cells expressing wt or mutant VnORP constructs [ORP4L (C), ORP2 (D)] in combination with VcVAPA and mCherry-VAPA. BiFC signal intensities were analyzed in a minimum of 100 cells per condition and normalized to the cotransfection marker mCherry-VAPA. Shown are BiFC signal intensity averages and standard deviations. (TIFF 43630 kb)

Supplementary Fig. S3 Electron microscopic analysis of cells expressing the VnORP9L and VcVAPA. (A) Transmission electron microscopy images of HuH7 cells expressing either the empty vectors (control) or VnORP9 in combination with VcVAPA. (B) Quantification of the thickness of ER sheets/tubules in control and ORP9L-VAPA-expressing cells. Shown are averages and SEM of 20 ER samples analyzed per condition; ***p < 0.005. (TIFF 43631 kb)

Supplementary Fig. S4 Impact of the ORP2 inositol-phosphate-binding cleft mutant (mPIP) on the distribution and total area of lipid droplets (LD). HuH7 cells expressing the indicated wt or mPIP VnORP2 and VcVAPA (BiFC), with the LD (Bodipy-C12) and nuclei (DAPI) co-stained. (A) Fluorescence microscopy images displaying the three channels and their merge. (B) Quantification of total LD area in a minimum of 20 cells per condition. Shown are averages and standard deviations. (C). The LD distribution in ORP2(wt)– and ORP2(mPIP)–VAPA-expressing cells. LD distribution was analyzed in a minimum of 10 cells per condition. The center of the nucleus was used to define the cell center. Shown are averages and SEM. (TIFF 43632 kb)

Acknowledgments

Liisa Arala, Eeva Jääskeläinen and Riikka Kosonen are thanked for skillful technical assistance, Prof. M. A. De Matteis (Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine, Naples, Italy) for the rabbit VAPA and -B antibodies, and Dr. I. Kaverina (Vanderbilt Univ., Nashville, TN, USA) for the mCherry-GalT1(1–81) construct. We thank Eija Jokitalo and the Electron Microscopy Unit (Institute of Biotechnology, Helsinki, Finland) for assistance with the transmission electron microscopy. The study was supported by the Academy of Finland (Grant 257409 to M.W.-B.), the Finnish Concordia Fund (H. K.), the Sigrid Juselius Foundation, the Novo Nordisk Foundation, the Liv ovh Hälsa Foundation, the Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, and the Magnus Ehrnrooth Foundation (V. M. O.). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

- BiFC

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation

- EM

Electron microscopy

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- FFAT

Two phenylalanines in an acidic tract

- GST

Glutathione-S-transferase

- LD

Lipid droplet

- MCS

Membrane contact site

- OHC

Hydroxycholesterol

- ORD

OSBP-related ligand-binding domain

- ORP

OSBP-related protein

- OSBP

Oxysterol-binding protein

- Osh

OSBP homolog (in yeast)

- PI4P

Phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate

- PIP

Phosphoinositide

- PM

Plasma membrane

- TG

Triglyceride

- VAMP

Vesicle-associated membrane protein

- VAP

VAMP-associated protein

References

- 1.Dawson PA, Ridgway ND, Slaughter CA, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. cDNA cloning and expression of oxysterol-binding protein, an oligomer with a potential leucine zipper. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:16798–16803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor FR, Saucier SE, Shown EP, Parish EJ, Kandutsch AA. Correlation between oxysterol binding to a cytosolic binding protein and potency in the repression of hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:12382–12387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang PY, Weng J, Anderson RG. OSBP is a cholesterol-regulated scaffolding protein in control of ERK 1/2 activation. Science. 2005;307:1472–1476. doi: 10.1126/science.1107710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mesmin B, Bigay J, Moser von Filseck J, Lacas-Gervais S, Drin G, Antonny B. A four-step cycle driven by PI(4)P hydrolysis directs sterol/PI(4)P exchange by the ER-Golgi tether OSBP. Cell. 2013;155:830–843. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anniss AM, Apostolopoulos J, Dworkin S, Purton LE, Sparrow RL. An oxysterol-binding protein family identified in the mouse. DNA Cell Biol. 2002;21:571–580. doi: 10.1089/104454902320308942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaworski CJ, Moreira E, Li A, Lee R, Rodriguez IR. A family of 12 human genes containing oxysterol-binding domains. Genomics. 2001;78:185–196. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lehto M, Laitinen S, Chinetti G, Johansson M, Ehnholm C, Staels B, Ikonen E, Olkkonen VM. The OSBP-related protein family in humans. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:1203–1213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beh CT, Cool L, Phillips J, Rine J. Overlapping functions of the yeast oxysterol-binding protein homologues. Genetics. 2001;157:1117–1140. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.3.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olkkonen VM, Li S. Oxysterol-binding proteins: sterol and phosphoinositide sensors coordinating transport, signaling and metabolism. Prog Lipid Res. 2013;52:529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raychaudhuri S, Prinz WA. The diverse functions of oxysterol-binding proteins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:157–177. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ridgway ND. Oxysterol-binding proteins. Subcell Biochem. 2010;51:159–182. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-8622-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaiser SE, Brickner JH, Reilein AR, Fenn TD, Walter P, Brunger AT. Structural basis of FFAT motif-mediated ER targeting. Structure. 2005;13:1035–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loewen CJ, Roy A, Levine TP. A conserved ER targeting motif in three families of lipid binding proteins and in Opi1p binds VAP. EMBO J. 2003;22:2025–2035. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du X, Kumar J, Ferguson C, Schulz TA, Ong YS, Hong W, Prinz WA, Parton RG, Brown AJ, Yang H. A role for oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 5 in endosomal cholesterol trafficking. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:121–135. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201004142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan D, Mäyränpää MI, Wong J, Perttilä J, Lehto M, Jauhiainen M, Kovanen PT, Ehnholm C, Brown AJ, Olkkonen VM. OSBP-related protein 8 (ORP8) suppresses ABCA1 expression and cholesterol efflux from macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:332–340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705313200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kagiwada S, Hosaka K, Murata M, Nikawa J, Takatsuki A. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae SCS2 gene product, a homolog of a synaptobrevin-associated protein, is an integral membrane protein of the endoplasmic reticulum and is required for inositol metabolism. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1700–1708. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.7.1700-1708.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishimura Y, Hayashi M, Inada H, Tanaka T. Molecular cloning and characterization of mammalian homologues of vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated (VAMP-associated) proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;254:21–26. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skehel PA, Armitage BA, Bartsch D, Hu Y, Kaang BK, Siegelbaum SA, Kandel ER, Martin KC. Proteins functioning in synaptic transmission at the sensory to motor synapse of Aplysia. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1379–1385. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00149-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skehel PA, Fabian-Fine R, Kandel ER. Mouse VAP33 is associated with the endoplasmic reticulum and microtubules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1101–1106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lev S, Ben Halevy D, Peretti D, Dahan N. The VAP protein family: from cellular functions to motor neuron disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:282–290. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moustaqim-Barrette A, Lin YQ, Pradhan S, Neely GG, Bellen HJ, Tsuda H. The amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 8 protein, VAP, is required for ER protein quality control. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:1975–1989. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishimura AL, Al-Chalabi A, Zatz M. A common founder for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis type 8 (ALS8) in the Brazilian population. Hum Genet. 2005;118:499–500. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-0031-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishimura AL, Mitne-Neto M, Silva HC, Richieri-Costa A, Middleton S, Cascio D, Kok F, Oliveira JR, Gillingwater T, Webb J, Skehel P, Zatz M. A mutation in the vesicle-trafficking protein VAPB causes late-onset spinal muscular atrophy and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:822–831. doi: 10.1086/425287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kvam E, Goldfarb DS. Nvj1p is the outer-nuclear-membrane receptor for oxysterol-binding protein homolog Osh1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . J Cell Sci. 2004;117:4959–4968. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levine TP, Munro S. Dual targeting of Osh1p, a yeast homologue of oxysterol-binding protein, to both the Golgi and the nucleus–vacuole junction. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1633–1644. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.6.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rocha N, Kuijl C, van der Kant R, Janssen L, Houben D, Janssen H, Zwart W, Neefjes J. Cholesterol sensor ORP1L contacts the ER protein VAP to control Rab7-RILP-p150 Glued and late endosome positioning. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:1209–1225. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200811005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulz TA, Choi MG, Raychaudhuri S, Mears JA, Ghirlando R, Hinshaw JE, Prinz WA. Lipid-regulated sterol transfer between closely apposed membranes by oxysterol-binding protein homologues. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:889–903. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200905007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stefan CJ, Manford AG, Emr SD. ER-PM connections: sites of information transfer and inter-organelle communication. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25:434–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tavassoli S, Chao JT, Young BP, Cox RC, Prinz WA, de Kroon AI, Loewen CJ. Plasma membrane–endoplasmic reticulum contact sites regulate phosphatidylcholine synthesis. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:434–440. doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vihervaara T, Uronen RL, Wohlfahrt G, Björkhem I, Ikonen E, Olkkonen VM. Sterol binding by OSBP-related protein 1L regulates late endosome motility and function. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:537–551. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0470-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stefan CJ, Manford AG, Baird D, Yamada-Hanff J, Mao Y, Emr SD. Osh proteins regulate phosphoinositide metabolism at ER-plasma membrane contact sites. Cell. 2011;144:389–401. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elbaz Y, Schuldiner M. Staying in touch: the molecular era of organelle contact sites. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:616–623. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helle SC, Kanfer G, Kolar K, Lang A, Michel AH, Kornmann B. Organization and function of membrane contact sites. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:2526–2541. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klecker T, Bockler S, Westermann B (2014) Making connections: interorganelle contacts orchestrate mitochondrial behavior. Trends Cell Biol (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Levine T, Loewen C. Inter-organelle membrane contact sites: through a glass, darkly. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toulmay A, Prinz WA. Lipid transfer and signaling at organelle contact sites: the tip of the iceberg. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:458–463. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blanchette-Mackie EJ, Dwyer NK, Barber T, Coxey RA, Takeda T, Rondinone CM, Theodorakis JL, Greenberg AS, Londos C. Perilipin is located on the surface layer of intracellular lipid droplets in adipocytes. J Lipid Res. 1995;36:1211–1226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robenek H, Hofnagel O, Buers I, Robenek MJ, Troyer D, Severs NJ. Adipophilin-enriched domains in the ER membrane are sites of lipid droplet biogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4215–4224. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu N, Zhang SO, Cole RA, McKinney SA, Guo F, Haas JT, Bobba S, Farese RV, Jr, Mak HY. The FATP1–DGAT2 complex facilitates lipid droplet expansion at the ER-lipid droplet interface. J Cell Biol. 2012;198:895–911. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201201139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soni KG, Mardones GA, Sougrat R, Smirnova E, Jackson CL, Bonifacino JS. Coatomer-dependent protein delivery to lipid droplets. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1834–1841. doi: 10.1242/jcs.045849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilfling F, Thiam AR, Olarte MJ, Wang J, Beck R, Gould TJ, Allgeyer ES, Pincet F, Bewersdorf J, Farese RV, Jr, Walther TC. Arf1/COPI machinery acts directly on lipid droplets and enables their connection to the ER for protein targeting. Elife. 2014;3:e01607. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilfling F, Wang H, Haas JT, Krahmer N, Gould TJ, Uchida A, Cheng JX, Graham M, Christiano R, Frohlich F, Liu X, Buhman KK, Coleman RA, Bewersdorf J, Farese RV, Jr, Walther TC. Triacylglycerol synthesis enzymes mediate lipid droplet growth by relocalizing from the ER to lipid droplets. Dev Cell. 2013;24:384–399. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Brito OM, Scorrano L. Mitofusin 2 tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Nature. 2008;456:605–610. doi: 10.1038/nature07534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Giordano F, Saheki Y, Idevall-Hagren O, Colombo SF, Pirruccello M, Milosevic I, Gracheva EO, Bagriantsev SN, Borgese N, De Camilli P. PI(4,5)P(2)-dependent and Ca(2+)-regulated ER-PM interactions mediated by the extended synaptotagmins. Cell. 2013;153:1494–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kornmann B, Currie E, Collins SR, Schuldiner M, Nunnari J, Weissman JS, Walter P. An ER–mitochondria tethering complex revealed by a synthetic biology screen. Science. 2009;325:477–481. doi: 10.1126/science.1175088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Manford AG, Stefan CJ, Yuan HL, Macgurn JA, Emr SD. ER-to-plasma membrane tethering proteins regulate cell signaling and ER morphology. Dev Cell. 2012;23:1129–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Srikanth S, Jew M, Kim KD, Yee MK, Abramson J, Gwack Y. Junctate is a Ca2+-sensing structural component of Orai1 and stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:8682–8687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200667109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takeshima H, Komazaki S, Nishi M, Iino M, Kangawa K. Junctophilins: a novel family of junctional membrane complex proteins. Mol Cell. 2000;6:11–22. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y, Deng X, Mancarella S, Hendron E, Eguchi S, Soboloff J, Tang XD, Gill DL. The calcium store sensor, STIM1, reciprocally controls Orai and CaV1.2 channels. Science. 2010;330:105–109. doi: 10.1126/science.1191086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuan JP, Kiselyov K, Shin DM, Chen J, Shcheynikov N, Kang SH, Dehoff MH, Schwarz MK, Seeburg PH, Muallem S, Worley PF. Homer binds TRPC family channels and is required for gating of TRPC1 by IP3 receptors. Cell. 2003;114:777–789. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00716-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou Y, Li S, Mäyränpää MI, Zhong W, Back N, Yan D, Olkkonen VM. OSBP-related protein 11 (ORP11) dimerizes with ORP9 and localizes at the Golgi-late endosome interface. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:3304–3316. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Skarp KP, Zhao X, Weber M, Jäntti J. Use of bimolecular fluorescence complementation in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Methods Mol Biol. 2008;457:165–175. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-261-8_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Saint-Jean M, Delfosse V, Douguet D, Chicanne G, Payrastre B, Bourguet W, Antonny B, Drin G. Osh4p exchanges sterols for phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate between lipid bilayers. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:965–978. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201104062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laitinen S, Lehto M, Lehtonen S, Hyvärinen K, Heino S, Lehtonen E, Ehnholm C, Ikonen E, Olkkonen VM. ORP2, a homolog of oxysterol binding protein, regulates cellular cholesterol metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:245–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lehto M, Hynynen R, Karjalainen K, Kuismanen E, Hyvärinen K, Olkkonen VM. Targeting of OSBP-related protein 3 (ORP3) to endoplasmic reticulum and plasma membrane is controlled by multiple determinants. Exp Cell Res. 2005;310:445–462. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seemann J, Jokitalo EJ, Warren G. The role of the tethering proteins p115 and GM130 in transport through the Golgi apparatus in vivo. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:635–645. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.2.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hynynen R, Suchanek M, Spandl J, Back N, Thiele C, Olkkonen VM. OSBP-related protein 2 is a sterol receptor on lipid droplets that regulates the metabolism of neutral lipids. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:1305–1315. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800661-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sherman F. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:3–21. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94004-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Novick P, Field C, Schekman R. Identification of 23 complementation groups required for post-translational events in the yeast secretory pathway. Cell. 1980;21:205–215. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kerppola TK. Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) analysis as a probe of protein interactions in living cells. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:465–487. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ngo M, Ridgway ND. Oxysterol binding protein-related Protein 9 (ORP9) is a cholesterol transfer protein that regulates Golgi structure and function. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1388–1399. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-09-0905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Suchanek M, Hynynen R, Wohlfahrt G, Lehto M, Johansson M, Saarinen H, Radzikowska A, Thiele C, Olkkonen VM. The mammalian OSBP-related proteins (ORP) bind 25-hydroxycholesterol in an evolutionarily conserved pocket. Biochem J. 2007;405:473–480. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]