Abstract

Introduction

Thyroid hormones affect growth, development, and metabolism of vertebrates, and are considered the major regulators of their homeostasis. On the other hand, elevated circulating levels of thyroid hormones are associated with modifications in the whole organism (weight loss and increased metabolism and temperature) and in several body regions. Indeed, tachycardia, atrial arrhythmias, heart failure, muscle weakness and wasting, bone mass loss, and hepatobiliary complications are commonly found in hyperthyroid animals and humans.

Results

Most thyroid hormone actions result from influences on transcription of T3-responsive genes, which are mediated through nuclear receptors. However, there is significant evidence that tissue oxidative stress underlies some dysfunctions produced by hyperthyroidism.

Discussion

During the last decades, increasing interest has been turned to the use of antioxidants as therapeutic agents in various diseases and pathophysiological disorders believed to be mediated by oxidative stress. In particular, because elevated circulating levels of thyroid hormones are associated with tissue oxidative injury, more attention has been paid to explore the application of antioxidants as therapeutic agents in thyroid related disorders.

Conclusions

At present, vitamin E is among the most commonly consumed dietary supplements due to the belief that it, as an antioxidant, may attenuate morbidity and mortality. This is due to the results of numerous scientific studies, which demonstrate that vitamin E has a primary function to destroy peroxyl radicals, thus protecting polyunsaturated fatty acids biological membranes from oxidative damage. However, results are also available indicating that protective vitamin E effects against oxidative damage can be obtained even through different mechanisms.

Keywords: Vitamin E, Thyroid hormone, Oxidative stress, Tissue injury

Introduction

It is now widely accepted that the oxygen utilization by aerobic organisms results in production of free radicals, which can initiate chain reactions eventually leading to cell structural and functional alterations [1]. Indeed, various processes occurring in mitochondria [2] and other cellular sites, including endoplasmic reticulum [3], peroxisomes [4] or cytosol [5], lead to partial oxygen reduction and formation of oxygen free radicals and other reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS include superoxide anion radical ( ), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radical (·OH). Of these, ·OH is the most reactive and can be generated by the reaction of H2O2 with iron (or copper) ions (the Fenton reaction).

), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radical (·OH). Of these, ·OH is the most reactive and can be generated by the reaction of H2O2 with iron (or copper) ions (the Fenton reaction).

ROS, and in particular ·OH, can attack polyunsaturated fatty acids in the biomembrane (causing a chain of peroxidative reactions) proteins and enzymes (damaging functional properties), and nucleic acids (causing strand breaks and altered bases) [6, 7].

In most (if not all) mammalian cells, another free radical, containing nitrogen and named nitric oxide (NO·), is synthesized from l-arginine by NO synthases (NOS) [8]. NO· is relatively unreactive, but may be converted to a number of more reactive derivatives, known collectively as reactive nitrogen species (RNS). Thus, reacting with superoxide, NO· produces peroxynitrite (ONOO−), a powerful oxidant, able to damage many biological molecules and decompose releasing small amounts of hydroxyl radicals [9].

To neutralize the oxidative effects of reactive metabolites of oxygen, aerobic organisms are endowed with a system of antioxidant defenses [10]. When free radical generation exceeds the antioxidant capacity of cells, oxidative stress develops [11]. Numerous experimental researches indicate that this phenomenon is related to the development of many pathological conditions, including atherosclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, and Parkinson and Alzheimer diseases [7]. A role of oxidative stress has also been suggested for the ageing process [12]. Moreover, the idea is widely shared that some complications of hyperthyroidism are due to thyroid-hormone-induced oxidative stress in target tissues [13–15].

Because antioxidant compounds can counteract the ROS effects, a good antioxidant nutritional status to diminish tissue oxidative damage in a wide range of diseases is recommended. Furthermore, there is considerable interest in the therapeutic use of antioxidants, which may involve the use of naturally occurring or synthetic antioxidants.

At present, vitamin E is among the most commonly consumed dietary supplements due to the belief that it provides health benefits against diseases associated with oxidative damage, even though results of some studies do not seem to encourage the use of vitamin E indiscriminate supplementation [16].

The present review, after briefly examining vitamin E characteristics and mechanisms underlying its antioxidant action, focuses on benefits of its administration in attenuating oxidative damage and altered function observed in hyperthyroid tissues.

Vitamin E

The term vitamin E was introduced in 1922 by Evans and Bishop [17] to describe a dietary factor in animal nutrition necessary for normal reproduction. After feeding female rats accidentally with rancid fat, they observed a deficiency syndrome in which fetal resorption was the more characteristic symptom. From the fact that adding fresh salad to the diets of the rats reversed the symptoms, they concluded that plants contained a specific protective factor.

The multiple nature of the vitamin began to appear in 1936, when two compounds with vitamin E activity, designated as α- and β-tocopherol, were isolated and characterized from germ oil [18]. In the following years, two additional tocopherols, γ- and δ-tocopherol [19, 20], as well as the tocotrienols [21] were isolated from edible plant oils, so that today a total of four tocopherols and four tocotrienols are known to occur in nature. About in the same years, other studies showed that the presence of rancid fat in the experimental diets fed to rats and chickens was the causative agent of various pathologies in these animals and that these abnormalities could be cured by wheat germ oil concentrates that contained tocopherols [22].

Human vitamin E deficiency symptoms began to be reported in the 1960s [23] studying patients with lipoprotein abnormalities and subsequently in fat malabsorption syndromes. However, it was not clear the extent to which various symptoms could be attributed to lack of vitamin because the patients had malabsorption of other nutrients, especially long-chain fatty acids. In the early 1980s [24], reports of humans with vitamin E deficiency symptoms without fat malabsorption began to appear in the literature. These patients had a peripheral neuropathy characterized as a dying back of the large-caliber axons in the sensory nerves [25]. In 1968, the American Food and Nutrition Board officially recognized the essential nature of vitamin E. However, yet today the in vivo mechanism of vitamin E action remains to be understood. For example, some researchers propose that the major vitamin function, if not the only function, is that of a peroxyl radical scavenger protecting the integrity of tissues and playing an important role in life processes [26]. However, vitamin E seems to be able to exert a protective effect against oxidative damage even through different mechanisms. Moreover, some authors support that vitamin E possess functions that are independent of its antioxidant, radical scavenging ability [27].

Antioxidant action of vitamin E

In 1982, Burton and collaborators [28] claimed that they had obtained the first proof that vitamin E is the major lipid-soluble, chain-breaking antioxidant in human blood plasma. Tocopherols and tocotrienols inhibit lipid peroxidation thanks to their ability to scavenge lipid peroxyl ( ) radicals faster than these radicals can react with adjacent fatty acid side chains. Although the efficacy of tocotrienols in membranes may be higher than that of tocopherols [29], uptake and distribution of tocotrienols after oral ingestion are lower of those of α-tocopherol.

) radicals faster than these radicals can react with adjacent fatty acid side chains. Although the efficacy of tocotrienols in membranes may be higher than that of tocopherols [29], uptake and distribution of tocotrienols after oral ingestion are lower of those of α-tocopherol.

α-Tocopherol (α-TocH) inhibits lipid peroxidation by scavenging peroxyl radical intermediates in the chain reaction to form the corresponding organic hydroperoxides (LOOH) and the α-tocopheryl radical (α-Toc·) [30]:

|

It is generally accepted that in lipid bilayers and biomembranes, α-tocopherol is oriented with the chroman head group toward the surface and the hydrophobic phytyl side chain buried within the hydrocarbon region. The aromatic ring lies in the proximity of the carbonyls groups of the fatty acid chains [31], and therefore the phenolic hydroxyl group lies near the surface region of the bilayer. To explain how LOO· can reach the phenolic hydroxyl group, it has been hypothesized that LOO·, which has a large dipole moment, is rather hydrophilic and floats towards the bilayer surface.

There are several reasons for the high effectiveness of α-tocopherol in breaking the chain of peroxidative reactions. Firstly, the α-tocopheryl radical, although not completely unreactive, is much less efficient than peroxyl radicals in attacking fatty acid side chains, so that the overall effect of α-tocopherol is to slow the chain reaction of lipid peroxidation [32]. The effectiveness of the α-tocopherol action is also due to possibility that it reacts with a further peroxyl radical to give non-radical product.

|

The observation that biologically important hydrogen donors are able in vitro to reduce tocopheryl radical back to tocopherol, has suggested that physiological mechanisms may exist for regenerating tocopherol.

Studies on isolated membranes and lipoproteins have shown that the ascorbate can reduce tocopheryl radical [32]. Indirect evidence that this regeneration also happens in vivo has been found showing that cigarette smokers have faster vitamin E turnover that can be normalized by vitamin C supplementation [33]. Moreover, there is limited evidence that reduced glutathione (GSH) can do so in some membrane systems [34].

Ubiquinol (CoQH2) can regenerate α-tocopherol from its radical in lipoproteins and membranes [35]:

|

Because in biological membranes only one tocopherol molecule is present for every 1,000 PUFA molecules [36], the regeneration of α-tocopherol by other antioxidants can explain how a small amount of vitamin E can suppress lipid oxidation in membranes.

On the other hand, it has been proposed that vitamin E might have a protective role in the membrane by acting as a structural component [37, 38]. The structural “antioxidant” role of vitamin E, as distinct from its free radical scavenging role, does not necessarily depend on the presence of the free hydroxyl group even though for this role vitamin E molecules associate specifically with the acyl chains of polyunsaturated fatty acids in the membrane.

Available information suggests that vitamin E’s protective effect against oxidative damage can also be due in part to down-regulation of mitochondrial ROS generation. Indeed, it has been shown that α-tocopherol is able to scavenge superoxide radicals [39]:

|

It has also been proposed that the superoxide radical itself might play a role in the repair of α-tocopheryl radical [40]:

|

The idea that such an effect can also happen in vivo is supported by finding that following α-tocopherol-administration the rate of  release by submitochondrial particle from mouse liver and skeletal muscle is inversely related to their α-tocopherol content [41] and rate of H2O2 release by intact mitochondria from rat liver and skeletal muscle is lowered by vitamin E supplementation in a dose-dependent fashion [42].

release by submitochondrial particle from mouse liver and skeletal muscle is inversely related to their α-tocopherol content [41] and rate of H2O2 release by intact mitochondria from rat liver and skeletal muscle is lowered by vitamin E supplementation in a dose-dependent fashion [42].

Thyroid hormone-induced oxidative stress

Thyroid hormones, of which T3 is the major active form, exert a multitude of physiological effects affecting the growth, development, and metabolism of vertebrates [43], so that can be considered major regulators of their homeostasis. On the other hand, elevated circulating levels of thyroid hormones are associated with tissue oxidative injury. Indeed, despite some disagreeing reports, most of the available data indicates that an experimentally induced hyperthyroid state causes oxidative damage of target tissues altering pro-oxidant-antioxidant balance characteristics of euthyroid tissues [15].

The literature concerning the effects of thyroid hormone on ROS and RNS production is poor, but there is convincing evidence for an increased radical production in hyperthyroid state.

Changes in ROS and RNS production

Fernández et al. [44] found that T3 administration for three consecutive days led to a progressive and significant enhancement in rat liver NOS activity, an effect that was reversed upon hormone withdrawal.

Subsequent studies showed that thyroid hormone induced up-regulation of NOS gene expression in rat hypothalamus [45] and NO· overproduction by human vascular endothelium [46] and rat phagocytic cells [47]. Furthermore, indirect evidence was also provided that NO· production increased in hyperthyroid heart [48, 49].

Several papers have shown that hyperthyroidism induces an increase in mitochondrial ROS generation. Swaroop and Ramasarma [50] found a stimulation of H2O2 generation following treatment of euthyroid rats with a single dose or three daily doses of T4.

Subsequently, it was found that liver submitochondrial particles from T3-treated rats exhibited an enhanced rate of succinate or NADH-supported  production, and succinate-supported H2O2 production in the absence and in the presence of antimycin-A (AA), a mitochondrial respiration inhibitor [51]. Interestingly, it was also found that thyroid hormone, which increases the number of liver peroxisomes [52], increased the rate of urate-supported AA-insensitive H2O2 generation by preparations of submitochondrial particles [51], suggesting a peroxisome role in hyperthyroid state-linked enhancement in liver ROS production.

production, and succinate-supported H2O2 production in the absence and in the presence of antimycin-A (AA), a mitochondrial respiration inhibitor [51]. Interestingly, it was also found that thyroid hormone, which increases the number of liver peroxisomes [52], increased the rate of urate-supported AA-insensitive H2O2 generation by preparations of submitochondrial particles [51], suggesting a peroxisome role in hyperthyroid state-linked enhancement in liver ROS production.

The rate of H2O2 release by liver [53], skeletal muscle (gastrocnemius) [54], and heart [55] intact mitochondria from rats made hyperthyroid by 10-day T3 administration to hypothyroid rats, was evaluated using complex I and complex II-linked substrates (succinate and pyruvate plus malate, respectively). Thus, it was found that, with all substrates, the rate of H2O2 release by liver and heart mitochondria increased in both basal (state 4) and ADP-stimulated (state 3) respiration, while that by muscle mitochondria increased only during basal respiration.

Reactive oxygen species production by the mitochondrial respiratory chain in brown adipose tissue (BAT) from hyperthyroid animals has not been determined. However, an increase in UCP1 following T3, but not T4, treatment has been reported [56, 57]. This result suggests that mitochondrial ROS production may be not increased by T3 treatment, thus providing an explanation for the finding that T3, unlike T4, does not induce oxidative stress in BAT [56].

There are only two papers dealing with microsomal ROS production in hyperthyroidism. The first reported an increased rate of NADPH-supported generation of superoxide radical by microsomal fractions from rat liver after two (30 %) to seven (67 %) days of treatment of euthyroid rats with T3 [58]. This report was in agreement with concomitant elevation in microsomal NADPH oxidase activity which had been shown to be associated with  production [59]. The T3-induced increase in the rate of NADPH-dependent H2O2 production by liver microsomes was confirmed by subsequent work [60]. In the same work, the rates of H2O2 production by monoamine oxidase were not found to be significantly modified by T3 or T4 treatment [60].

production [59]. The T3-induced increase in the rate of NADPH-dependent H2O2 production by liver microsomes was confirmed by subsequent work [60]. In the same work, the rates of H2O2 production by monoamine oxidase were not found to be significantly modified by T3 or T4 treatment [60].

Kupffer cell involvement in thyroid hormone-induced oxidative stress

Although most of the increased ROS and RNS production observed in liver of hyperthyroid rats occurs at the parenchymal cell level, several reports indicate that a substantial contribution is supplied by Kupffer cells. Indeed, a significant portion of the T3-induced increase in both liver lipid peroxidation and NOS activity is abolished by gadolinium chloride (GdCl3) inactivation of Kupffer cells [44, 61]. It has also been shown that T3 administration to rats produces transient activation of hepatic nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) [62], a redox-sensitive factor responsible for the transcriptional activation of cytokine-encoding genes. It appears that such an activation involves a role for T3-induced free-radical activity in Kupffer cells because it is decreased by in vivo treatment with α-tocopherol and N-acetylcysteine and abolished by GdCl3 treatment. Moreover, livers from hyperthyroid rats with enhanced NF-κB DNA binding activity show induced messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of the NF-κB-responsive genes for tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [62], a cytokine known to stimulate ROS generation [63]. The rapid increase in ROS production after T3 administration appears to be responsible, in rat liver, of the translocation, from the cytosol to the nucleus, of the cytoprotective nuclear transcription factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), which in turn can be responsible for the upregulation of antioxidant proteins and phase 2 detoxifying enzymes [64]. In turn, the early increase in TNF-α production may contribute to the late NF-κB activation considering that TNF-α promotes the phosphorylation of both the inhibitory IκB proteins, allowing their degradation [65], and NF-κB p65 subunit, which stimulates the transcriptional activity of NF-κB [66]. However, the transient increment in the circulating levels of TNF-α [62] suggests that the establishment of a dangerous positive feedback loop is avoided. This can be due to the late effect of T3 on the expression of the NF-κB responsive gene for interleukin (IL)-10 [62], which is able to preserve expression of the inhibitory IκB protein [67].

It is worth noting that the relationship between thyroid hormones and immune cells is complex. Indeed, while in Kupffer cells, proinflammatory activities increase in hyperthyroidism, those of monocytes and macrophages decrease [68]. Moreover, for many immune cells, no clear correlation has been found between thyroid hormone levels and the effects observed on the immune responses [68].

Changes in antioxidant defense system

The effects of thyroid hormone on antioxidant status have been extensively investigated in rat tissues, but it needs to underline that although thyroid hormone can directly control levels of enzymes with antioxidant activity or regulate scavenger content, reported changes could not be the cause, but the consequence of the oxidative stress. Moreover, in total, the thyroid hormone-induced changes in the various antioxidants do not offer a coherent pattern [15]. On the other hand, even with more consistent data, measurements of selected antioxidants should provide limited information regarding the total antioxidant status of the tissue. Indeed, this approach does not permit a complete appraisal of the synergistic cooperation of the various antioxidant systems. Therefore, an appropriate approach to determine the thyroid hormone-induced changes in antioxidant defense system effectiveness should be to challenge tissues with specific free radicals in vitro. Studies performing such experiments showed that whole antioxidant capacity (CA) underwent significant decrease in liver [69, 70] and heart [70], but not in gastrocnemius muscle [70] from hyperthyroid rats.

The above results indicate that the changes in the individual components of the tissue antioxidant defense system strongly reduce the global efficacy of such a system in liver and heart, but not in gastrocnemius muscle from hyperthyroid rats. However, they do not exclude the possibility that the efficacy of the antioxidant system is reduced in other muscles, since it is known that red, but not white, skeletal muscles, are sensitive to thyroid hormones [71, 72]. Indeed, thyroid hormone increases lipid peroxidation in soleus, a red muscle prevalently composed of slow-twitch oxidative glycolitic fibers (type I), but not in extensor digitorum longus (EDL) [73, 74] a white muscle prevalently composed of fast-twitch glycolitic fibers (type IIb). Furthermore, lipid peroxidation is increased by the hormone in rat gastrocnemius [70, 75], a mixed-fiber muscle also containing fast-twitch oxidative glycolytic fibers (type IIa), but is decreased in the white portion of such a muscle [76]. It is conceivable that the lack of changes of whole antioxidant capacity of gastrocnemius is due to a balance of the differential responses evoked by thyroid hormone in the different types of fibers.

Tissue susceptibility to oxidants

The results concerning ROS production and antioxidant capacity suggest that the oxidative damage displayed by hyperthyroid tissues can be a consequence of increased free radical activity and reduced effectiveness of the antioxidant defense systems. However, this does not provide information on sensitivity of the hyperthyroid tissues to oxidative processes. Indeed, other thyroid-state-linked changes in biochemical characteristics of the tissues can modify their susceptibility to oxidants and the extent of the oxidative damage they suffer following oxidative challenge.

Lipid peroxidation is initiated after hydrogen abstraction from polyunsaturated fatty acids by ·OH radicals, and it is known that lipid susceptibility to peroxidative processes increases as a function of the number of double bonds of their fatty acids.

Thyroid hormone ability to influence the lipid composition in rat tissues is well known [77], so it is expected that lipid peroxidation can be modified in hyperthyroid tissues subjected to oxidative attack. In fact, it was found that the in vitro induction of an index of lipid peroxidation, such as TBARS, by tert-butyl hydroperoxide, H2O2, or FeSO4/ascorbic acid in brain from hyperthyroid rats was very high when compared to euthyroid rats [78]. Conversely, no difference was found between euthyroid and hyperthyroid preparations from adult rat testis [79]. Using FeSO4/ascorbic acid, it was found that sensitivity to in vitro lipid peroxidation was increased in skeletal [80] and cardiac [81] muscles, and decreased in liver [82] from T4-treated mice. Sensitivity of mouse liver to in vitro lipid peroxidation, as well as endogenous lipid peroxidation levels, correlated well with fatty acid composition. Indeed, highly unsaturated 20:4n-6 and 20:3n-3 fatty acids, unsaturation and peroxidizability indexes, as well as double-bond index decreased in T4-treated mice [82].

The content of high and low molecular Fe2+ complexes, which promote the conversion of H2O2 into ·OH radicals via the Fenton reaction [83–85], can also affect tissue susceptibility to ROS-induced damage. The extent of oxidative changes occurring under conditions leading to increased in vivo ROS production was evaluated by measuring the levels of light emission resulting from in vitro exposure to H2O2 of biological preparations. The relationship between light emission and homogenate concentration was supplied by the equation:  , in which the parameters a and b were dependent on the concentrations of substances able to induce and inhibit, respectively, the H2O2-induced luminescent reaction [86]. Using such a technique, it was established that susceptibility to oxidative challenge is higher in hyperthyroid than in euthyroid tissues, including liver [69, 70], heart [70], and muscle [70], because of higher a values and lower b values. In the whole, these results are consistent with the increase in cytochrome content [87] and the decrease in antioxidant capacity [70] found in hyperthyroid tissues.

, in which the parameters a and b were dependent on the concentrations of substances able to induce and inhibit, respectively, the H2O2-induced luminescent reaction [86]. Using such a technique, it was established that susceptibility to oxidative challenge is higher in hyperthyroid than in euthyroid tissues, including liver [69, 70], heart [70], and muscle [70], because of higher a values and lower b values. In the whole, these results are consistent with the increase in cytochrome content [87] and the decrease in antioxidant capacity [70] found in hyperthyroid tissues.

Does hypothyroidism induce oxidative stress?

Although hypothyroidism has long been thought to protect tissues against free radical damage [88–90], some results suggest that hypothyroidism is associated with increased oxidative damage. However, it occurs to underline that, whereas for men, except one disagreeing report [91], there is substantial accord on hypothyroidism-induced increase in plasma markers of oxidative stress [92–94], for animals conflicting results are available. Thus, hypothyroidism obtained by thyroidectomy was associated with decreased oxidative stress in rat heart [95] and kidney [96]. Conversely, when hypothyroidism was elicited in rats by administration of anti-thyroid drugs, lipid peroxidation was found to be increased in amygdala [97] and hippocampus [97, 98], increased [99] and unchanged in cerebellum, striatum, motor cortex [97], and cerebral cortex [99]. Lipid peroxidation was also found increased in serum [98–100], plasma, and red blood cells [101], whereas it was found increased in liver [101, 102], heart and skeletal muscle [101], unchanged in the same tissues [70], and decreased in liver and heart [103]. Protein-bound carbonyls, a marker of protein oxidative damage, were found decreased in liver, heart, and skeletal muscle [103], whereas increased DNA oxidative damage was found in serum and aorta [100]. In hypothyroid mouse, no change in lipid peroxidation was found in liver [82] and heart [81], whereas a decrease in oxidative damage was found in heart mitochondrial DNA [81].

Because methimazole, the most widely used anti-thyroid drug in Europe and North America, causes several undesirable side effects, some works compared the effects of thyroidectomy and methimazole on cell damage and tissue oxidative damage. Thus, it was found that methimazole (but not thyroidectomy) caused cell damage in the spleen, heart, liver, lung, and kidney [104]. Moreover, cell damage was found to be associated with an increase of oxidative-stress markers in spleen [105] and liver [106].

Oxidative stress-linked dysfunction of hyperthyroid tissues

It is well known that elevated circulating levels of thyroid hormones are associated with modifications in the whole organism (weight loss and increased metabolism and temperature) and in several body compartments. Indeed, low plasma lipid levels, tachycardia, atrial arrhythmias, heart failure, muscle weakness, and wasting are commonly found in the hyperthyroid animals. Plasma membrane [107], endoplasmic reticulum [108], and mitochondria [109] have been considered as potential cellular sites of thyroid hormone action. However, it is now generally accepted the idea that most of the actions of thyroid hormone results from influences on transcription of T3-responsive genes, which are mediated through nuclear thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) [110].

Thyroid hormone receptors are members of the nuclear receptor superfamily and function as T3-inducible transcription factors. There are two subtypes of nuclear receptors, TRα and TRβ, which are encoded by two different genes and can selectively mediate some specific thyroid hormone responses [111]. Studies on mutant mice have shown that TRα mediates T3 effects on heart rate and modulates body temperature, whereas TRβ mediates the cholesterol-lowering and TSH-suppression effects of T3 [111].

It is worth noting that the idea that oxidative stress underlies dysfunctions produced by hyperthyroidism is not in contrast with the mediation of T3 action through nuclear events. Indeed, it is conceivable that some of the biochemical changes favoring the establishment of the oxidative stress (increase in NOS activity, mitochondrial levels of autoxidizable electron carriers, and unsaturation degree of lipids) are due to a stimulation of the expression of specific genes initiated through T3 binding to nuclear receptors. Thyroid hormone induces up-regulation of NOS gene expression in rat hypothalamus [45] and it is conceivable that this also happens in other tissues in which T3-induced NO· overproduction has been shown [44, 46, 49].

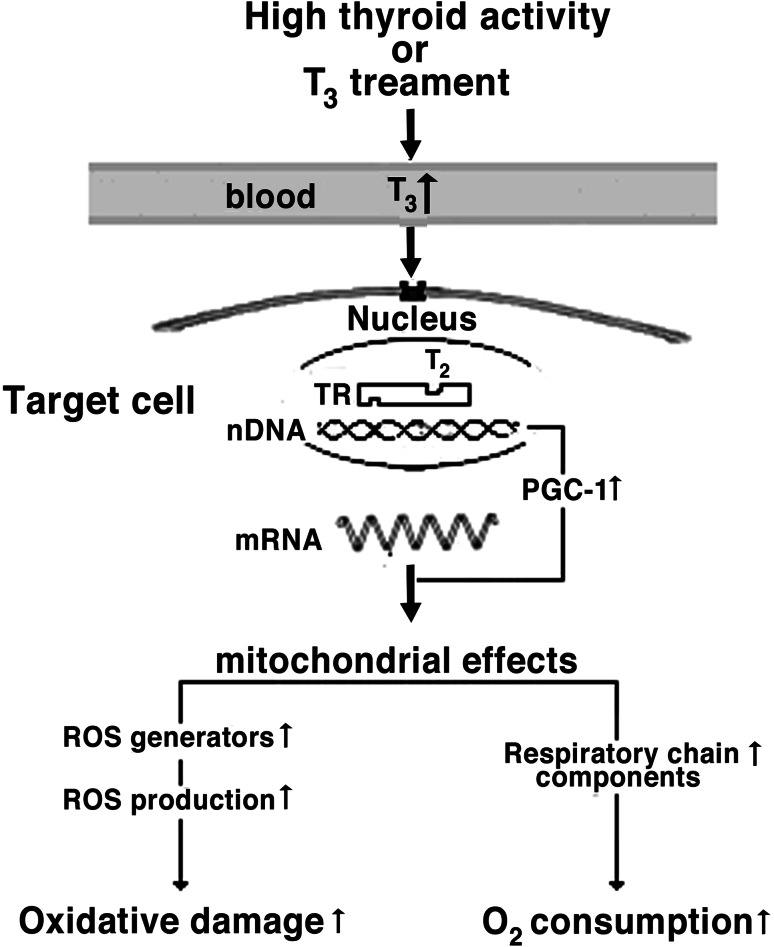

Triiodothyronine increases tissue respiration and oxidative damage, enhancing mitochondrial oxygen consumption and ROS production, changes which are likely linked to the higher mitochondrial content of respiratory chain components including autoxidizable electron carriers [15]. The respiratory apparatus expression is controlled by nuclear regulatory proteins including nuclear respiratory factors 1 and 2 (NRF-1 and NRF-2), and the peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator (PGC-1). NRF-1 and NRF-2 are transcriptional factors involved in the transcriptional control of many genes regulating mitochondrial function and biogenesis [112]. PGC-1 is a transcriptional coactivator, whose expression is stimulated by T3 [113], powerfully induces mRNA for NRF-1 and NRF-2 and binds to and coactivates NRF-1, and increases its transcriptional activity on target genes, including promoter for mitochondrial transcription factor A (mtTFA), a direct regulator of mitochondrial replication and transcription [114] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pathway of cell oxidative damage elicited by T3 treatment. Following thyroid hormone treatment, T3 binds to thyroid hormone receptors (TRs), which stimulate expression of nuclear and mitochondrial (not shown) genes. Among T3-regulated genes, a pivotal role is played by peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor coactivator alpha (PGC-1), which enters the nucleus and activates the expression of components of respiratory chain. This leads, together with increased O2 consumption, to accelerated ROS production and cell oxidative damage. Up arrow increased, down arrow decreased

To date, there is increasing direct evidence for a relationship between ill effects of hyperthyroidism and oxidative stress in some tissues. Moreover, in some cases, indirect evidence results from the demonstration that the antioxidant supplementation is able to reduce both tissue oxidative damage and dysfunction.

Liver injury

Thyroid hormones play a major role in hepatic lipid homeostasis. Indeed, they increase the expression of apolipoprotein A1 [115], an important component of high-density lipoprotein. They also increase the expression of low-density lipoproteins (LDL) receptors on the hepatocyte membranes [115] and the activity of lipid-lowering liver enzymes [116], resulting in a reduction in LDL levels. These effects are beneficial in delaying the onset of atherosclerosis. On the other hand, serious hepatobiliary complications, including centrilobular hepatic necrosis, intrahepatocytic cholestasis, and cirrhosis are associated with untreated hyperthyroidism [117].

It is not clear if the features seen in hyperthyroid liver are secondary to the systemic effects of thyroid hormones or result from their direct toxic effects on the liver. However, the finding that T3-induced liver oxidative stress was associated with significant increases in efflux of GSH, lactate dehydrogenase, and proteins from the liver into the sinusoidal space [118] suggested that thyroid hormone may destabilize hepatic plasma membranes, possibly via the enhancement in lipid and protein oxidation.

A study dealing with the effects of vitamin E treatment on liver mitochondrial fractions from hyperthyroid rats showed that the vitamin reduces lipid peroxidation and increases whole antioxidant capacity in homogenates and mitochondria [69]. Furthermore, it attenuates the alterations in the percentage content of the different mitochondrial subpopulations in the hepatic tissue [69]. Subsequent studies demonstrated that vitamin E supplementation reduced biochemical, morphological, and functional changes induced by T4 treatment [119]. Indeed, it prevented the increases in serum transaminase activity and liver lipid peroxidation and alleviated the hepatocyte proliferation and the decrease in sinusoidal space observed in hyperthyroid rats. Moreover, it prevented the increases in mitochondrial state 4 respiration found with complex I-linked substrates.

The energy released during state 4 is used to restore the proton gradient dissipated by mechanisms which induce the leak of protons back in the mitochondrial matrix bypassing ATP synthase. It is long known that the inner mitochondrial membrane is partially permeable to protons [120], but the molecular mechanisms of the proton leak are still matter of debate. However, it is widely accepted that there are two important pathways of proton leak: a basal proton conductance of the mitochondrial membrane and an inducible proton conductance mediated by specific leak proteins [121]. These include adenine nucleotide translocator (ANT) [122] and uncoupling proteins (UCPs) [123], found in brown adipose tissue and in other tissues.

The thyroid hormone-induced increase in ANT content [124] in liver mitochondria could explain the increase in state 4 respiration. However, another explanation, involving free radical production, is possible. Thyroid hormone increases both mitochondrial ROS production [51, 54, 125] and NO· production [44] in hepatic tissue. Moreover, both superoxide radical [126] and peroxynitrite [127], the product of reaction between  and NO·, increase H+ mitochondrial leak by a mechanism which seems to involve lipid peroxidation.

and NO·, increase H+ mitochondrial leak by a mechanism which seems to involve lipid peroxidation.

In this light, it is readily understandable how vitamin E, which inhibits lipid peroxidation by scavenging peroxyl radicals, can prevent the increase in state 4 induced by thyroid hormone. It is interesting that the protective effects against oxidative processes and mitochondrial dysfunction were greater in response to concomitant supplementation with vitamin E and curcumin, an anti-inflammatory agent, which, as inhibitor of arachidonic acid metabolism [128], can also inhibit the arachidonic acid cascade, which is activated by thyroid hormone-induced imbalance of Ca2+ homeostasis [129] and leads to ROS production [130]. More recent work suggests that the effectiveness of concomitant supplementation with vitamin E and curcumin is also due to their effects on antioxidant gene expression in hyperthyroid rat liver [131].

Information on the effects of other antioxidants on thyroid hormone-induced liver oxidative damage is poor. However, it has been found that melatonin [132, 133], the major secretory product of the pineal gland provided with free radical scavenging properties, and caffeic acid phenylethyl ester [134], an active component of propolis provided with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, reduce lipid peroxidation, whereas vitamin C is not effective in preventing DNA damage in hyperthyroid rat [135].

Potentiation of xenobiotic hepatotoxicity

It is well established that the hepatotoxicity of a variety of substances, such as lindane [136], halothane [137], isoflurane and enflurane [138], carbon tetrachloride [139], and chloroform [140], which seems to be linked to the development of an oxidative stress condition, is enhanced by hyperthyroid state.

The mechanism for liver toxicity of anesthetic agents, such as isoflurane, enflurane, and halothane, in hyperthyroid state has been scarcely investigated. Conversely, more information is available on possible mechanisms of thyroid hormone potentiation of the hepatotoxicity of lindane, a substance used as an insecticide and disinfectant in agriculture, which also enters in the composition of some lotions, creams, and shampoos against parasites. Lindane was found to induce liver microsomal cytochrome P450 system and enhance microsomal superoxide [141] and cytosolic NO· [142] generation. Lindane also increased lipid peroxidation and altered some antioxidant mechanisms of the hepatocyte, including decreased SOD and CAT activities [140]. These changes related to oxidative stress were dose [143] and time [141] dependent, and coincided with the onset and progression of morphological lesions [141]. Studies concerning thyroid hormone effects on lindane hepatotoxicity showed that combined lindane-T3 administration increased ROS production [136, 143], and GSH [136] and α-tocopherol [144] depletion in an extent exceeding the sum of the effects elicited by the separate treatments, concomitantly with extensive liver necrosis. On the whole, these data support the view that the increased liver susceptibility to lindane intoxication in hyperthyroidism depends on potentiation of tissue oxidative stress. This effect may be conditioned by an enhanced respiratory burst activity due to Kupffer cell hyperplasia and polymorphonuclear leukocyte infiltration [136], in addition to the increased ROS production in parenchymal cells.

Potentiation of ischemia–reperfusion injury

Although restoration of blood flow is necessary to salvage ischemic tissues, additional insult may occur during reoxygenation and contribute to ischemia–reperfusion injury [145]. Studies on free radical production and protective effect of various antioxidants in ischemia–reperfusion systems have suggested that tissue dysfunction during reperfusion results from free radical generation and oxidative damage [146]. Therefore, ischemia–reperfusion constitutes a model of oxidative injury adequate to test the capability of hyperthyroid tissues to face an oxidative challenge.

Studies on rat liver showed that hyperthyroid tissue subjected to ischemia–reperfusion exhibited elevation in the TBARS/GSH ratio and sinusoidal lactate dehydrogenase efflux largely exceeding the sum of effects elicited by hyperthyroidism or ischemia-reflow alone [147]. These results indicate that the concurrence of the hepatic mechanisms underlying thyroid hormone-induced oxidative stress and ischemia–reperfusion exacerbates liver injury, which appears to be mediated by potentiation of the pro-oxidant state of the organ.

Thyrotoxic myopathy

Thyrotoxic myopathy is a well-known example of tissue damage due to the action of thyroid hormones. Although such a syndrome was long thought to be extremely rare [148], it commonly occurs in hyperthyroid patients. It has been reported [149] that the examination of 54 unselected patients revealed clinical myopathy in 44 while electromyographic studies detected abnormalities in nearly all of them. Prevailing symptoms include muscle weakness and wasting, difficulty in climbing stairs, rising from a chair, or brushing hair [150]. Histochemically, there is atrophy of both fiber types [151] and some patients have an increased frequency of type 2 fibers [152].

In rodents, thyrotoxic myopathy is characterized by similar morphological [153, 154], biochemical [153], and functional [155] alterations, including fiber atrophy and conversion of fibers from type 1 to type 2 [156]. The muscle atrophy was attributed to increased protein catabolism by thyroid hormones, with increased lysosomal activity and release of amino acids [157, 158]. The weakness was attributed to a combination of factors including reduced membrane excitability and a lower power of contraction due to an increased rate of relaxation [151, 152].

Skeletal muscle myopathy induced by hyperthyroidism appears to limit exercise tolerance. The idea that impaired exercise tolerance can be due to decreased left ventricular function is not supported by the observation that cardiac output [159] and skeletal muscle blood flow [160] are elevated during exercise in the hyperthyroid state. Impaired exercise capacity was also related to the decrease in muscle oxidative capacity dependent on tissue atrophy and accelerated protein catabolism [159]. However, it is unlikely that the protein loss contributes in relevant measure to the weakness of hyperthyroid muscles, being that their strength decreased by 40–100 % and the mass only by the 20 % [161].

A mechanism underlying thyrotoxic myopathy was suggested by Asayama and Kato [12], which, analyzing various muscular injury models in which ROS are supposed to play a role, showed that mitochondrial function and glutathione–dependent antioxidant systems are important for the maintenance of the structural and functional integrity of muscular tissues. Because hyperthyroid muscles show similar biochemical changes which are prevented, at least partly, by the suppression of oxidative metabolism and vitamin E administration, it was proposed that ROS contribute to the muscular injury caused by thyroid hormones [12]. However, it is necessary to note that although lipid peroxidative damage may partly account for the muscle alterations found in hyperthyroidism, no direct evidence for a muscular dysfunction mediated by ROS in hyperthyroid animals was reported. Furthermore, the demonstration reported by Asayama et al. [162] that vitamin E administration decreased lipid peroxidation in hyperthyroid muscles was not accompanied by the determination of the vitamin effect on functionality of hyperthyroid muscle.

Subsequently, attempts were made to find the molecular basis for contractile dysfunction in hyperthyroidism. Thus, it was shown that T3 treatment elicited a decrease in the relative content of myosin heavy chain (MHC) in myofibrillar proteins and a greater increase in carbonyl content in MHC than in myofibrillar protein extracts [163]. Because MHC comprises sulfhydryl (SH)-containing cysteine residues critical for contractile function, it is conceivable that it exhibits high susceptibility to oxidation and that the decrease of its content reduces force production in hyperthyroid muscles. The relationship between susceptibility to myofibrillar oxidation and contractile dysfunction was supported by observations showing that exogenous administration of carvedilol, a β-blocker provided with antioxidant activity, prevented both phenomena [164].

Sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) plays a central role in the excitation–contraction coupling process regulating intracellular free Ca2+ concentration and its impaired function has been implicated in force depression induced by exhaustive exercise [165]. However, although protein oxidation accounts, at least in part, for the decay in SR function [166], such a decay does not seem to be implicated in decline in contractile function of hyperthyroid muscles [167] because hyperthyroidism results in increases in SR Ca2+ release and uptake rates.

Effects of prolonged exercise on function of hyperthyroid muscle

Despite the limited direct evidence of free radical generation during exercise, there is an abundance of literature providing indirect support that oxidative stress occurs during prolonged aerobic exercise when muscle oxygen consumption is markedly increased [168]. Moreover, there is little doubt that vitamin E is essential for normal cell function during exercise. Davies and collaborators [169] found that vitamin E deficiency exacerbated muscle free radical production and enhanced lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial dysfunction in exhaustively exercised rats. Conversely, dietary supplementation of vitamin E increased tissue resistance to exercise-induced lipid peroxidation [170].

Because acute long-term exercise leads to oxidative stress condition, it can be used to test the idea that thyroid hormone decreases the effectiveness of muscle tissue in preventing oxidative alterations and functional derangement. Moreover, it can also supply evidence that the concomitance of conditions that increase the potential for oxidative stress may have synergistic effects enhancing the probability of muscle injury and dysfunction. Accordingly, the involvement of an increased ROS production and oxidative damage on function of hyperthyroid skeletal muscle was studied determining the effect of prolonged swimming and severe hyperthyroidism on rat gastrocnemius muscle [171]. Thus, it was found that both treatments induced increases in indices of oxidative damage such hydroperoxides and protein-bound carbonyls. On the other hand, exercise induced higher oxidative damage and respiratory capacity reduction in hyperthyroid than in euthyroid skeletal muscle. Furthermore, the fall in tissue function was associated with reduced exercise endurance capacity. Because impaired cell function can result from mitochondrial dysfunction, the changes induced by exercise in oxygen consumption of skeletal muscle mitochondria from euthyroid and hyperthyroid rats were evaluated [172].

Thus, it was shown that, following exercise, respiration of muscle mitochondria from hyperthyroid rats increased during state 4 and decreased during state 3 with both complex I- and complex II-linked substrates, while cytochrome oxidase activity was not affected. Conversely, in euthyroid muscles, mitochondrial respiration was reduced only during succinate-sustained state 3 and in lesser measure than that found in hyperthyroid preparations. The observation that exercise modified respiration of the muscular tissue in a similar way [171] without affecting its mitochondrial protein content showed that the impairment of the mitochondrial respiration was responsible for the changes observed in whole tissue oxygen consumption.

It is conceivable that the increase in state 4 respiration induced by thyroid hormone or exercise in the skeletal muscle may be due, like in the liver, to a lipid peroxidation-mediated increase in proton leak. Conversely, differently from liver, it is possible to exclude an involvement of ANT because in skeletal muscle ANT expression is not affected by both thyroid hormone [173] and acute exercise [174]. Moreover, UCP1 homologue could contribute to increased mitochondrial proton conductance because its expression is up-regulated in skeletal muscle by both thyroid hormone [175] and exercise [174]. The fall observed in state 3 respiration can be due to a direct action of ROS and/or RNS. Indeed, damage to respiratory chain components by ROS [176] and inhibition of mitochondrial function by peroxynitrite [177] have been reported. The decline of the respiration rate in preparations from hyperthyroid exercised rats is likely to involve peroxynitrite, which during exercise could be formed in greater amount from the reaction of NO· with O·−2and cause irreversible inhibition of many mitochondrial components different of cytochrome aa3 [178].

Alterations of cardiac function

Although thyroid hormone plays an important role in the regulation of heart mechanical and electrophysiological properties, disorders of the thyroid gland produce alterations in cardiac function, including tachycardia and other arrhythmias.

Heart electrical activity

It is long known that thyroid hormone stimulates basic metabolic rate and metabolism of carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins [179] and increases cardiac electrical performance [180] and heart rate [181] in response to the demand placed on the heart for greater tissue perfusion.

About four decades ago, intracellular electrode recording from rabbit sinoatrial node cells [182] demonstrated that thyroid hormone can affect heart rate by direct modulation of action potential duration (APD) in pacemakers cells. Thyroid hormone-induced increase in heart rate requires APD shortening in atrial and ventricular fibers in order to allow full electrical and mechanical recovery. Records of the action potential from atrial cells of rabbit [183] and ventricular preparations from some mammalian species, such as rabbit [184], guinea-pig [185, 186], and rat [187], showed that these results can be obtained by thyroid hormone-induced alterations in membrane currents, which are species- and cell-dependent.

Sharp and collaborators [184], on the basis of pharmacological interventions, suggested that accentuation of a transient K+ current was responsible for the early fast phase of repolarization in ventricular muscle from hyperthyroid rabbits. This view was supported by studies using the whole cell, suction electrode voltage-clamp method, which showed that the transient outward current (I t) was altered quite dramatically in ventricular myocytes from hyperthyroid rabbits [188]. In striking contrast, the same current was not affected in atrial cells taken from the same heart [188]. The dependence of the current on stimulation rate was also changed so that it persisted at high rates of stimulation, which normally suppress it. Subsequently, while in ventricular myocytes an increase in current magnitude, a change in rate dependence, and a reduced temperature sensitivity were found, in atrial myocytes there was no change in any of these features of I t [189]. Moreover, the study of the other major currents (L-type calcium current and the inwardly rectifying potassium current I K1) showed that in rabbit ventricular myocytes I t is unique in its sensitivity to hyperthyroid conditions [190].

The size and the rate dependence of the transient and steady-state outward potassium (I ss) currents were also investigated in ventricular myocytes isolated from rats in different thyroid states [190]. In hypothyroid cells, I t was reduced in size, with no significant change in I ss, while the rate dependence of both currents, was greatly enhanced resulting in a much larger attenuation with increasing stimulation rates. These effects of the hypothyroidism were reversed by physiological T3 replacement, while under hyperthyroid conditions no significant changes were observed in the amplitude and time course of recovery of I t. I ss amplitude was increased but no changes were found in its rate dependence.

The direct measurement of the membrane current on guinea pig ventricular myocytes showed that I t, at a membrane potential of 50 mV, was bigger in hyperthyroid myocytes, but of similar amplitude in hypo- and euthyroid myocytes [186]. Furthermore, in hypothyroid and hyperthyroid myocytes, I Ca was smaller and bigger, respectively, than in euthyroid myocytes. Although the I Ca increase may reduce the repolarization rate by providing an inward current, the related increase in intracellular Ca2+ may induce Ca-activated K+ [191] or non-specific currents [192]. Subsequent work, using the patch-clamp technique, showed that hyperthyroidism led to an APD shortening and delayed rectifier K+ current increase greater in the right than in the left atrium, which can contribute to the propensity for atrial arrhythmia in hyperthyroid heart [193].

In light of the cellular effects of the thyroid hormones, it was also suggested that the electrophysiological alterations seen in hyperthyroid state were induced via synthesis of proteins that are part of ion channels [186]. This idea was supported by the finding that thyroid hormone increased K+ channel gene expression in rat ventricle [194], and atrium [195], and protein expression levels of Kv1.5 and Kv2.1 in murine atria [193] and decreased the L-type calcium channel expression in rat atrium [195].

The changes in membrane currents could not be dependent on a direct action of thyroid hormone, but be mediated through alterations of factors able to affect membrane currents. The in vitro effects of free radicals on cardiac electrophysiology have been widely studied [196–199], whereas little information is available on electrophysiological modifications related to the accelerated production of ROS in vivo. However, it was shown that procedures increasing free radical production, such as hydroperoxide administration [200], physical exercise [201], and cold exposure [202], were associated with APD shortening in rat ventricular muscle fibers.

The ROS involvement in the thyroid hormone-induced modifications in electrical properties of the sarcolemmal membrane, suggested by the similarity between the changes in action potential configuration seen in hyperthyroidism and the aforementioned conditions, was demonstrated by the ability of vitamin E to attenuate the alterations in heart rate and ventricular APD in hyperthyroid rats [203]. The recovery of APD remained incomplete after administration of higher doses of vitamin E [204], indicating that the electrophysiological effects of thyroid hormone were in part mediated by other nuclear or extranuclear mechanisms. Furthermore, it was also found that the administration of antioxidants such as vitamin E and N-acetylcysteine reduced both lipid peroxidation levels and APD changes. Conversely, the diet addition of cholesterol decreased lipid peroxidation but did not modify the APD. This finding indicates that the antioxidant-sensitive shortening of APD is independent of lipid peroxidation. Because vitamin E is able to prevent the loss of protein thiols due to oxidative attack [205], it was suggested that the effect of the vitamin on membrane currents was due to protection of sulphydryl-containing ion channel proteins [204]. The phenolic group of the vitamin, lain near the surface of the bilayer, could both protect protein thiol groups against free radical attack and be regenerated by water soluble reducing agents such as glutathione [34]. If so, the protective action of N-acetylcysteine should be due to its ability to increase efficiency of the vitamin system maintaining high GSH concentrations [206]. The idea that antioxidant-sensitive shortening of APD is independent of lipid peroxidation is also supported by several electrophysiological studies. The specific changes in ionic currents, shown in myocyte membranes after exposure to free radical generating systems [197, 207], are not consistent with a phenomenon, such as the peroxidation of the lipid phase of the membrane, which has been found to interfere with the normal selective permeability [208, 209]. In this context, it is interesting that specific changes in I ca,L and I K have been found in guinea pig ventricular myocytes either isolated from hyperthyroid animals [186, 188] or exposed to free radical generating system consisting of xanthine/hypoxanthine [210].

Potentiation of ischemia–reperfusion heart injury

Although restoration of blood flow is necessary to salvage ischemic heart, oxidative stress, due to a ROS generation, occurs during reoxygenation and contributes to ischemia–reperfusion injury [146]. In light of high incidence and mortality of cardiac disease, it is understandable that several experimental studies have been performed to address the possibility that antioxidant supplementation provides protection against ischemic-reperfusion injury. Such studies showed the protective effects on isolated hearts of several antioxidants, including vitamin E [211], flavonoids [212], and melatonin [213]. However, further studies are needed to establish whether the antioxidants have therapeutic benefit in ischemic heart disease patients.

The ischemia–reperfusion was used as a model of oxidative injury to test the possibility that thyroid hormone-induced biochemical changes also reduce the effectiveness of myocardial tissue to prevent oxidative alterations [214].

Thus, it was shown that during reperfusion following 20-min ischemia, hyperthyroid hearts displayed a significant tachycardia. Furthermore, they exhibited lower recovery of left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP) and maximal rate of developing left ventricular pressure (dP/dtmax), associated with more extensive peroxidative processes compared to euthyroid hearts. The tachycardic response and the increase in lipid peroxidation were prevented by treatment of hyperthyroid rats with vitamin E. This suggested that the tachycardic response to reperfusion following chronic T3 treatment was associated with a reduced capability of the heart to face oxidative stress. The high susceptibility to ischemia–reperfusion of hyperthyroid hearts was associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, H2O2 production, and oxidative damage higher than those shown in mitochondria from euthyroid hearts [215].

Subsequently, the role of nitric oxide in the mitochondrial derangement associated with the functional response to ischemia–reperfusion of hyperthyroid rat hearts was investigated [49]. Evidence for NO· involvement in reperfusion-induced dysfunction of hyperthyroid hearts was found determining heart response to ischemia–reperfusion, with and without Nω-nitro-l-arginine (l-NNA), a NOS inhibitor. Indeed, perfusion with the NOS inhibitor prevented tachicardic response to ischemia–reperfusion of hyperthyroid hearts, thus increasing their inotropic recovery up to the euthyroid level. Moreover, l-NNA also decreased mitochondrial H2O2 production and oxidative damage, and increased respiration and tolerance to swelling, thus confirming the role of mitochondria in ischemia–reperfusion damage.

Osteoporosis

Linear growth and skeletal maturation occur during fetal and childhood development and continue until epiphyseal fusion occurs, a process resulting from endochondral ossification in the epiphyseal growth plates of long bones.

In adults, the mechanical integrity of the skeleton is maintained by a process called bone remodeling in which old bone is locally removed by osteoclasts and replaced with newly formed bone by osteoblasts [216]. Remodeling enables bone to adapt to mechanical stress and to repair micro-damage, thus maintaining its strength, whereas its alterations are responsible for most metabolic bone diseases, including osteoporosis and the reduction in bone mineral density.

The rate at which given sites undergo remodeling is known as the bone formation rate, or activation frequency, and is the major factor that determines total bone turnover.

The major regulators of development and childhood growth include growth hormone (GH), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), glucocorticoids (GC), and thyroid hormones.

Physiological concentrations of thyroid hormones are essential for skeletal development and growth during childhood and the maintenance of bone mass, so that alterations in thyroid status result in growth abnormalities, bone loss, and increased fracture risk [217].

Thyrotoxicosis in children advances bone age and accelerates skeletal development, resulting in early cessation of growth and short stature due to premature fusion of the growth plates. In severe cases, early closure of the cranial sutures may also result in craniosynostosis [218, 219].

Reconstruction of the bone remodeling sequence in hyperthyroid patients indicates that bone resorption and formation are both accelerated, so that the remodeling cycle is shortened. The duration of the resorption and formation phases are reduced by 60 and 30 %, respectively, whereas the frequency of initiation of bone remodeling is increased. The reduction of remodeling duration and the negative balance between resorption and formation, result in a net loss of about 10 % of mineralized bone per cycle, with ultimately a reduction in bone mineral density and a predisposition to fractures [220]. Calcium kinetic studies in hyperthyroid patients have shown that intestinal calcium and phosphate absorption is reduced, while urinary, fecal, and dermal calcium excretion is increased [221]. Thus, thyrotoxicosis induces a condition of negative calcium balance and this negative balance may also contribute to the increased fracture risk. In addition, levels of biochemical markers of both bone formation and bone resorption are elevated in thyrotoxicosis and generally correlate with thyroid hormone concentrations [217, 222, 223].

Mechanisms of thyroid hormone action

Despite the numerous investigations dealing with thyroid hormone and skeleton, the cellular basis of T3 action in bone remains incompletely understood. A number of studies involving the genetic alteration of TR isoforms in mice have provided considerable insight into the activity of these receptors in the bone. These studies suggest that TRα is the predominant isoform in bone and is the essential receptor regulating bone development [224, 225]. However, they do not allow to distinguish whether skeletal defects result from the systemic consequences of TR disruption or from local actions of T3 in skeletal cells. Thyroid hormones regulate activities of numerous signaling pathways that influence the skeleton including the GH/IGF-1 and sex steroid axes as well as various growth factors and cytokines that regulate bone cell differentiation and function [226]. On the other hand, thyroid hormone has been reported to directly stimulate bone resorption in organ culture [227] and regulate gene expression in various cell culture systems [228]. Thus, it is possible that skeletal responses to thyroid hormones are largely secondary to direct effects of thyroid hormones in non-skeletal cells, or they result from T3 direct action of thyroid hormones in bone cells. For example, it has been suggested that T3 indirectly stimulates osteoclastic bone resorption through the release of soluble mediators from osteoblasts [229]. In fact, T3 directly stimulates the production of IL-6, and also IL-1-induced IL-6 production in osteoblast-lineage cells. However, despite the many potential T3-target genes identified in osteoblasts, little information is available regarding mechanisms by which their expression is modulated.

ROS involvement in bone resorption

To the best of our knowledge, the eventual involvement of ROS in thyroid hormone-induced bone loss has not been investigated. This lack is amazing in light of the reported effect of ROS on bone resorption.

Oxygen-derived free radicals, such as the superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide, have been shown to be involved in the formation and activation of osteoclasts, the cells responsible for bone resorption [230, 231]. Free radical-induced oxidative stress in humans has been shown to have a negative effect on bone mineral density [232], suggesting that free radicals may disturb the balance between bone formation and resorption.

Osteoclasts generate superoxide, which is necessary for bone resorption [230, 231]. In turn, superoxide contributes to the degradation of bone matrix proteins, such as osteocalcin, increasing the capacity of osteoclasts to resorb bone [231].

The observation that osteoclastic superoxide generation is inhibited by diphenyleneiodonium, a specific inhibitor of the NADPH oxidase, a common enzyme system producing superoxide in white cell phagocytes, suggested that such a system is also present and active in osteoclasts [233]. The phagocytic NADPH oxidase system consists of cytosolic factors (p47phox, p67phox, Rac1/2, and p40phox) and a membrane-bound cytochrome b558 containing two subunits, gp91phox and p22phox [234]. In resting cells, the enzyme is dormant, and its components are distributed between the cytosol and the plasma membrane. When cells are activated, the cytosolic components migrate to the membrane where they associate with the membrane-bound cytochrome b558 and become the catalytically active NADPH oxidase [234]. A study designed to quantify the level of gp91phox, which represents the catalytic subunit of NADPH oxidase, showed that the amount of gp91phox present in the osteoclast exceeds that in the white blood cell, suggesting that the NADPH oxidase complex is present in large amounts in osteoclasts [235]. However, in studies of p91 knockout mice, osteoclasts were found to generate normal amounts of superoxide [236]. Examining murine osteoclasts for an alternative to the p91-containing oxidase, the presence of a p91-like protein (Nox 4) was demonstrated, which explains the ability of osteoclasts from p91 knockout mice to resorb bone normally [236].

It has also been reported that oxidative stress increases bone resorption through activation of nuclear factor-kappa B, which normally regulates osteoclast differentiation and, thus, bone resorption and remodeling [237].

The link between increased oxidative stress and reduced bone mineral density has been supported by studies showing the effects of antioxidant vitamins on bone and cartilage tissues in various species animals and in humans. α-Tocopherol prevented osteoclast formation and bone loss in elderly men through indirect inhibition of receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) expression in osteoblasts and direct suppression of c-Fos expression in osteoclast precursors [238]. Ascorbic acid and ascorbic acid 2-phosphate, a long-acting vitamin C derivative, affect proliferation and differentiation of human osteoblast-like cells [239]. An observational study of 533 randomly selected nonsmoking postmenopausal women showed that the duration of use of antioxidant supplements, including vitamins C and E, negatively correlated with age-adjusted and weight-adjusted serum C-telopeptide, the marker of bone resorption, thus suggesting that antioxidant vitamins may suppress bone resorption in humans [240].

Ferric nitrilotriacetate (FeNTA), a substance first used to induce diabetes in rats [241], has also been used to study free radical damage to the liver and kidney [242, 243]. It was shown that it is able to damage bone and impair bone growth in rats [244, 245] and these damages were believed to be mediated by the free radicals generated by iron. This view was supported by studies using vitamin E mixtures extracted from palm oil. Palm olein (which is the refined, bleached, and deodorized palm oil used for cooking) contains 196 ppm α-tocopherol, 201 ppm α-tocotrienol, 372 ppm β-tocotrienol and 96 ppm γ-tocotrienol [246]. Early study showed that vitamin E extracted from palm oil was protective against FeNTA-induced impairment of bone calcification in growing rats [247]. Subsequent study demonstrated that a palm tocotrienol mixture (α-tocotrienol 30.7 %, γ-tocotrienol 55.2 % and δ-tocotrienol 14.1 %) offered better protection than α-tocopherol against FeNTA-induced damage of rat bone [248]. The study also demonstrated that the tocotrienol mixture was better than pure α-tocopherol in protecting bone against FeNTA-induced elevation of cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6, known to play a major role in the bone remodeling process [249, 250].

Mechanisms underlying thyroid hormone action on bone resorption

The above results indicates that the  production by NADPH oxidase is responsible for bone resorption in euthyroid condition. It is conceivable that the acceleration of bone resorption in hyperthyroidism can be due to an excessive

production by NADPH oxidase is responsible for bone resorption in euthyroid condition. It is conceivable that the acceleration of bone resorption in hyperthyroidism can be due to an excessive  production by thyroid hormone-induced increase in NADPH oxidase activity. Actually, in the literature, such an effect is not reported, but there is evidence that thyroid hormone is able to increase NADPH oxidase activity in other cell types. Indeed, thyroid hormone-dependent increase of the enzyme activity associated with enhanced

production by thyroid hormone-induced increase in NADPH oxidase activity. Actually, in the literature, such an effect is not reported, but there is evidence that thyroid hormone is able to increase NADPH oxidase activity in other cell types. Indeed, thyroid hormone-dependent increase of the enzyme activity associated with enhanced  production were found in rat liver microsomal fraction [58], and polymorphonuclear leukocytes [251]. Moreover, increased expression of NADPH oxidase was found in heart homogenates from hyperthyroid rats [252]. In cardiomyocyte culture treated with T3, increases in cell growth and

production were found in rat liver microsomal fraction [58], and polymorphonuclear leukocytes [251]. Moreover, increased expression of NADPH oxidase was found in heart homogenates from hyperthyroid rats [252]. In cardiomyocyte culture treated with T3, increases in cell growth and  and H2O2 concentrations were also found, which returned to normal levels when the culture was treated with Trolox [252].

and H2O2 concentrations were also found, which returned to normal levels when the culture was treated with Trolox [252].

The involvement of NADPH oxidase in bone resorption also allows proposing an alternative mechanism to explain the inhibitor effect of vitamin E. Such a mechanism should be based on the possibility that α-tocopherol has additional antioxidant effects by inhibiting ROS generation by NADPH oxidase. Although the effect of vitamin E on osteoclast NADPH oxidase has not been determined, the mechanism is supported by the results of studies performed on other cellular types. An in vitro study [253] revealed that vitamin E treatment inhibited  production by monocytes by impairing the assembly of NADPH oxidase, the enzyme responsible for generating the respiratory burst. Vitamin E inhibited p47phox translocation to the membrane and also impaired phosphorylation of p47phox resulting from a decreased activity of protein kinase C (PKC) [253]. These results were consistent with the observation that vitamin E decreased monocyte

production by monocytes by impairing the assembly of NADPH oxidase, the enzyme responsible for generating the respiratory burst. Vitamin E inhibited p47phox translocation to the membrane and also impaired phosphorylation of p47phox resulting from a decreased activity of protein kinase C (PKC) [253]. These results were consistent with the observation that vitamin E decreased monocyte  release and monocyte-mediated lipid oxidation via inhibition of PKC [254], an enzyme that is involved in NADPH-oxidase activation and can phosphorylate p47phox [255]. The inhibition of PKC activity was not directly due to the antioxidant capacity of vitamin E but required its integration into the cell membrane where it could interact with PKC [253].

release and monocyte-mediated lipid oxidation via inhibition of PKC [254], an enzyme that is involved in NADPH-oxidase activation and can phosphorylate p47phox [255]. The inhibition of PKC activity was not directly due to the antioxidant capacity of vitamin E but required its integration into the cell membrane where it could interact with PKC [253].

Lifelong consumption of antioxidant-rich diet (acid ascorbic and α-tocopherol) reduced hypertension and oxidative stress in renal tissue from spontaneously hypertensive rats [256]. Antioxidant-rich diet appeared to attenuate oxidative stress, not only by fortifying antioxidant defense capacity but also by lowering NADPH oxidase.

Subsequent studies on the effects of vitamin E derived from palm oil on bone turnover in thyrotoxic rats showed that palm vitamin E reduced bone resorption to a greater extent than bone formation in thyrotoxic rats, suggesting a net reduction in bone loss [257]. The action of palm vitamin E was attributed to its antioxidant properties. Moreover, the observation that survival rates were also significantly increased in thyrotoxic rats given palm vitamin E suggested the role of free radicals in the overall morbidity and mortality in thyrotoxicosis.

Palm vitamin E supplementation significantly lowered serum alkaline phosphatase activity, a marker of bone formation, and serum tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase activity, a marker of bone resorption. The reduction in tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase activity was greater than that of alkaline phosphatase, suggesting a net increase in bone formation.

Conclusions

At present, available data indicate that some complications of hyperthyroidism are due to thyroid-hormone-induced oxidative stress in target tissues. Furthermore, the indisputable conclusion resulting from examination of the current literature is that vitamin E supplementation is able to attenuate oxidative stress. On the other hand, the role of vitamin E in the various tissue dysfunctions found in hyperthyroidism requires further study using animals made experimentally hyperthyroid and patients with thyroid disorders.

References

- 1.Chance B, Sies H, Boveris A. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:527–605. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turrens JF, Alexandre A, Lehninger AL. Ubisemiquinone is the electron donor for superoxide formation by complex III of heart mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;237:408–414. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staats DA, Lohr DP, Colby HD. Effects of tocopherol depletion on the regional differences in adrenal microsomal lipid peroxidation and steroid metabolism. Endocrinology. 1988;123:975–980. doi: 10.1210/endo-123-2-975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhaunsi GS, Gulati S, Singh AK, Orak JK, Asayama K, Singh I. Demonstration of Cu–Zn superoxide dismutase in rat liver peroxisomes. Biochemical and immunochemical evidence. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:6870–6873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw S, Jayatilleke E. Ethanol-induced iron mobilization, role of acetaldehyde-aldehyde oxidase generated superoxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 1990;9:11–17. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90044-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kehrer JP. Free radicals as mediators of tissue injury and disease. Crit Rev Toxycol. 1993;23:21–48. doi: 10.3109/10408449309104073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free radicals in biology and medicine. 3. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knowles RG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide synthases in mammals. Biochem J. 1994;298:249–258. doi: 10.1042/bj2980249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radi R, Cassina A, Hodara R, Quijana C, Castro L. Peroxynitrite reactions and formation in mitochondria. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:1451–1464. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)01111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu BP. Cellular defenses against damage from reactive oxygen species. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:139–162. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sies H. Oxidative stress, oxidants and antioxidants. London: Academic Press; 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sohal RS, Mockett RJ, Orr WC. Mechanisms of aging, an appraisal of the oxidative stress hypothesis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:575–586. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00886-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asayama K, Kato K. Oxidative muscular injury and its relevance to hyperthyroidism. Free Radic Biol Med. 1990;8:293–303. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90077-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Videla LA. Energy metabolism, thyroid calorigenesis, and oxidative stress, Functional and cytotoxic consequences. Redox Rep. 2000;5:265–275. doi: 10.1179/135100000101535807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venditti P, Di Meo S. Thyroid hormone-induced oxidative stress. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:414–434. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5457-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dotan Y, Lichtenberg D, Pinchuk I. No evidence supports vitamin E indiscriminate supplementation. BioFactors. 2009;35:469–473. doi: 10.1002/biof.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans HM, Bishop KS. On the existence of a hitherto unrecognized dietary factor essential for reproduction. Science. 1922;56:650–651. doi: 10.1126/science.56.1458.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans HM, Emerson OH, Emerson GA. The isolation from wheat germ oil of an alcohol, α-tocopherol, having the properties of vitamin E. J Biol Chem. 1936;113:319–332. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emerson OH, Emerson GA, Evans HM. The chemistry of vitamin E, tocopherols from various sources. J Biol Chem. 1937;122:99–107. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stern MH, Robeson CD, Weisler L, Baxter JG. Delta-tocopherol; isolation from soybean oil and properties. J Am Chem Soc. 1947;69:869–874. doi: 10.1021/ja01196a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pennock JF, Hemming FW, Kerr JD. A reassessment of tocopherol in chemistry. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1964;17:542–548. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(64)90062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolf G. The discovery of the antioxidant function of vitamin E, the contribution of Henry A. Mattil. J Nutr. 2005;135:363–366. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kayden HJ, Silber R, Kossmann CE. The role of vitamin E deficiency in the abnormal autohemolysis of acanthocytosis. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1965;78:334–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burck U, Goebel HH, Kuhlendahl HD, Meier C, Goebel KM. Neuromyopathy and vitamin E deficiency in man. Neuropediatrics. 1981;12:267–278. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1059657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sokol RJ. Vitamin E deficiency and neurological disorders. In: Packer L, Fuchs J, editors. Vitamin E in health and disease. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1993. pp. 815–849. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Traber MG, Atkinson J. Vitamin E, antioxidant and nothing more. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:4–15. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Azzi A, Gysin R, Kempná P, Munteanu A, Negis Y, Villacorta L, Visarious T, Zingg J-M. Vitamin E mediates cell signalling and regulation of gene expression. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1031:86–95. doi: 10.1196/annals.1331.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burton GW, Joyce A, Ingold KU. First proof that vitamin E is major lipid-soluble, chain-breaking antioxidant in human blood plasma. Lancet. 1982;8293:327. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(82)90293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]