Abstract

Recent work on the MACPF/CDC superfamily of pore-forming proteins has focused on the structural analysis of monomers and pore-forming oligomeric complexes. We set the family of proteins in context and highlight aspects of their function which the direct and exclusive equation of oligomers with pores fails to explain. Starting with a description of the distribution of MACPF/CDC proteins across the domains of life, we proceed to show how their evolutionary relationships can be understood on the basis of their structural homology and re-evaluate models for pore formation by perforin, in particular. We furthermore highlight data showing the role of incomplete oligomeric rings (arcs) in pore formation and how this can explain small pores generated by oligomers of proteins belonging to the family. We set this in the context of cell biological and biophysical data on the proteins’ function and discuss how this helps in the development of an understanding of how they act in processes such as apicomplexan parasites gliding through cells and exiting from cells.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00018-012-1153-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: MACPF domain, Cholesterol-dependent cytolysins, Pore, Membrane interactions, Membrane damage

Introduction

This review will discuss lipid membrane interactions by an important and conserved protein superfamily, MACPF/CDC proteins. These proteins have important roles in bacterial pathogenesis and the immune system and most of the observed effects are mediated by membrane interactions and the formation of transmembrane pores. We will describe various effects of MACPF/CDC proteins on membranes and associated physiological consequences. The membrane attack complex/perforin (MACPF) domain proteins are defined on the basis of their sequence similarity to the common domain present in proteins of the immune system, e.g., some proteins contributing to the membrane attack complex (MAC) and perforin (PFN) [1]. The determination of MACPF domain structures showed that this family is structurally homologous to cholesterol-dependent cytolysins (CDCs) [2–4] and the whole superfamily is now collectively referred to as the MACPF/CDC family of pore-forming proteins [5].

MACPF/CDC domain proteins and their distribution

CDCs are predominately found in genera of Gram-positive bacteria, such as Clostridium, Streptococcus, Listeria, Bacillus, Arcanobacteria, etc. Their primary function is to damage host cellular membranes by forming transmembrane pores [6, 7]. CDCs are multidomain proteins that exhibit 40–70 % identical residues. They were originally considered to be composed of four domains, which possess particular functions in their pore-forming mechanism (see discussion below) (Fig. 1a). CDCs attach to membranes by their C-terminal domain 4 (D4), which in most cases is able to recognize cholesterol [8], but which in the case of intermedilysin (ILY) from Streptococcus intermedius binds its protein receptor, CD59 [9]. Protein oligomerization at the plane of the membrane is enabled primarily through contacts involving domain 1 (D1), while domain 3 (D3) provides for the formation of the transmembrane β-barrel out of a set of α-helices during pore formation and domain 2 (D2) is a linking structure that provides the necessary flexibility required for the final pore-forming oligomer to be completed [10, 11]. The CDCs’ membrane interactions are thus mediated by D4 and in part by D3. The four-domain architecture is conserved in all CDCs, with the notable exception of lectinolysin from Streptococcus mitis, which contains an additional fucose-binding lectin domain at the N-terminus [12]. However, the original definition of four domains within the CDC structure is thrown into question by the resolution of MACPF protein structures (Fig. 1b) as this shows that what were called domains 1 and 3 should in fact be seen as a single functional unit with a fold conserved throughout the tree of life (see below). The equivalent regions to CDC “domains” 1 and 3 within the MACPF/CDC superfamily domain have instead been termed the upper and lower segments of that structure, between which a hinge sits mediating conformational changes associated with activity [13]. The MACPF/CDC domain adopts a more open conformation about this hinge in the case of C8α than in, for example, the CDC perfringolysin (PFO) from Clostridium perfringens (Fig. 1a) or perforin (see below) [13].

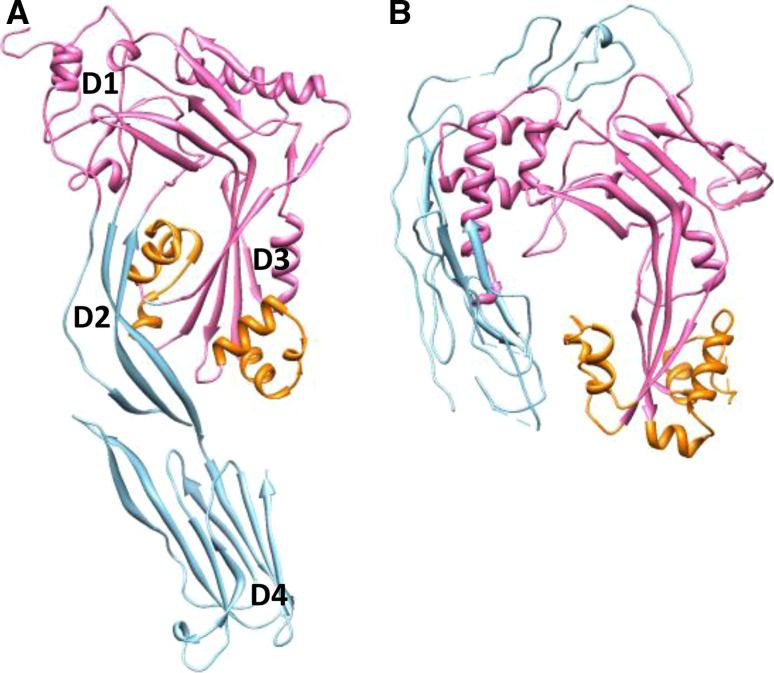

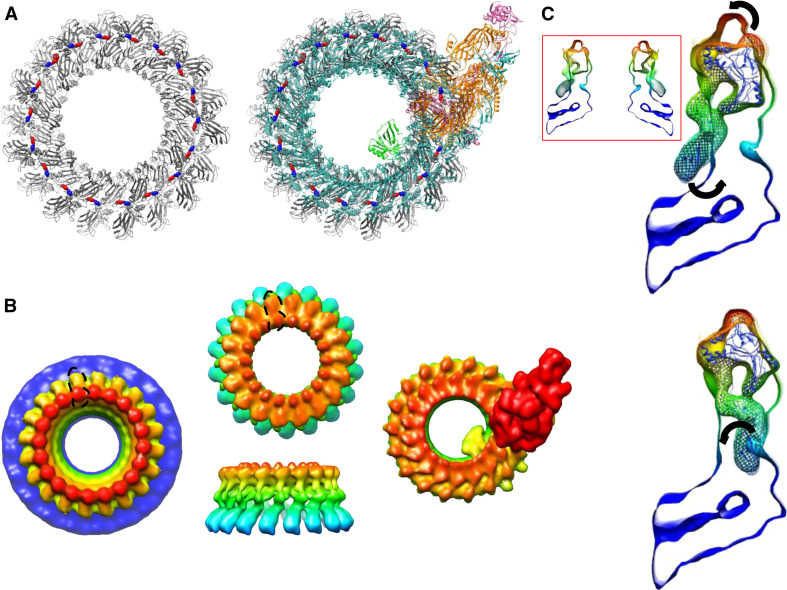

Fig. 1.

Structure of CDC and MACPF proteins. a Crystal structure of PFO [125] in which the four originally identified domains are labeled D1–D4, but with the MACPF/CDC domain colored pink against the blue of the linking (D2) and C-terminal (D4) domains. The helical regions refolding to form a β sheet are colored orange. b Crystal structure of C8α [13, 34, 35] colored in a way matching PFO: canonical MACPF domain (pink), helices contributing to pore formation (orange)

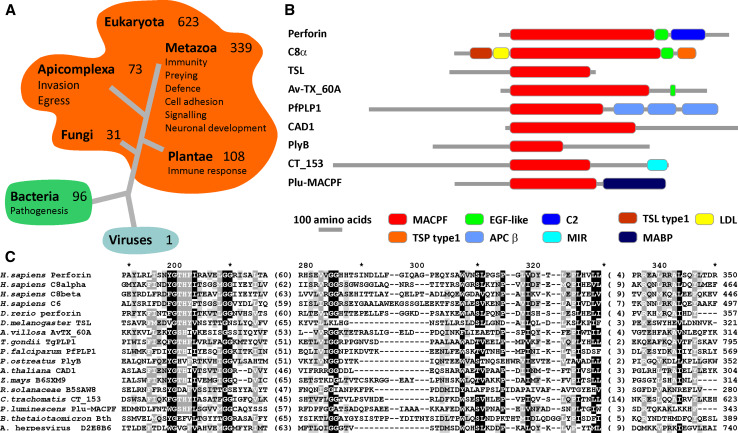

The distribution and functions of MACPF domain-containing proteins is very broad and highly intriguing. The MACPF protein family (PF01823) contains 720 sequences according to the current version of Pfam [14]. The majority of the sequences are present in metazoans, but they may be found also in prokaryotes and one sequence was found in anguillid herpesvirus 1 [15] (Fig. 2a). Some organisms possess several MACPF genes, the most extreme example being amphioxus (Branchiostoma floridae), which contains 29 MACPF genes [16]. In prokaryotes, most of the MACPF domain proteins come from Chlamydia, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidia and it has been proposed that bacteria acquired genes coding MACPF proteins by horizontal gene transfer [17, 18]. This would mean that while some bacteria have acquired MACPF proteins in relatively recent evolutionary periods by transfer, others which express the homologous CDCs have preserved these proteins from ancient evolutionary origins. In general, there is only one MACPF domain per protein and it is usually associated with other protein domains, which may provide membrane targeting and specificity (Fig. 2b). The domain architecture of MACPF-containing proteins is much simpler in bacteria, which contain a different selection of associated domains than found in metazoans. Furthermore, the MACPF domain in bacteria is almost exclusively located N-terminally to other domains.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of MACPF domains. a The distribution of MACPF sequences (PF01823) according to the PFAM database. The associated functions of proteins that contain MACPF domains are also listed when known. b The domain architecture of several examples is presented in the alignment in c, as defined in Pfam. c Alignment of the most conserved part of the MACPF domain. The numbering above the alignment is according to PFN. The numbers in brackets denote the length of the segment that is not conserved between the sequences

In contrast to prokaryotes, some metazoan protein sequences possess two or even three MAPCF domains. There appears to be weak sequence conservation among the family, as the most conserved positions are glycine residues in the middle of the MACPF domain, at the hinge between the upper and lower segments [13] and in PFN at residues number 229 and 230 together with some residues nearby (Fig. 2c). One or the other of these glycines are also conserved in CDC members of the superfamily—in anthrolysin from Bacillus anthracis (ALY) the first and in PFO and ILY the second—but could only be identified by structural superposition (see below) [2, 3]. The most studied and understood role of MACPF proteins is in the immune system, where they help in removing unwanted cells from organisms such as those that have been mitogenically transformed, virally infected, or that are themselves invading microorganisms [19, 20]. MACPF domain proteins have also been proposed to have a role in preying [21], defense [22], signaling [23], cell adhesion, and neuronal development [24, 25], etc. MACPF proteins are well represented in apicomplexans, where they facilitate parasite invasion and egress from tissues [26] (see below). Some pathogenic bacteria use MACPF domains in pathogenesis [2, 17], while in plants MACPF-containing proteins have a role in pathogen-induced plant responses [27] (Fig. 2a). Cell membranes are central to all of the biological functions connected with MACPF domain proteins and it seems that the large majority of MACPF sequences interact with them.

When the structures of the first MACPF domain proteins were determined [2–4], it became apparent that this domain is similar to what was designated domains 1 and 3 of the CDCs (see details below) (Fig. 1) and it was inferred that the mechanism of pore formation would proceed in a similar way to that found in the CDCs [28, 29]. This proposition was later confirmed for human PFN by structural and functional studies [30, 31]. Similar to the CDCs, the initial membrane interactions of MACPF proteins are enabled by small domains placed C-terminally to the MACPF domain, or by additional subunits [29]. In PFN, this is achieved by the C2 domain [32]. In other cases there are other domains that may be used to attach to the cell surface by binding to sugars, i.e., an MIR domain, Jacalin-like lectin domain, MABP, etc. (Fig. 2b). However, many of the proteins do not contain associated domains, such as in torso-like protein from Drosophila melanogaster (Fig. 2b) and it remains to be determined whether these proteins and those that do not possess membrane-binding domains interact with the membranes at all to exert their physiological role, perhaps by associating with other subunits as in the complement C9 association with the C5b-8 complex [13, 33–35], and the bi-component pleurotolysin [36].

MACPF domain structures and implications for pore formation

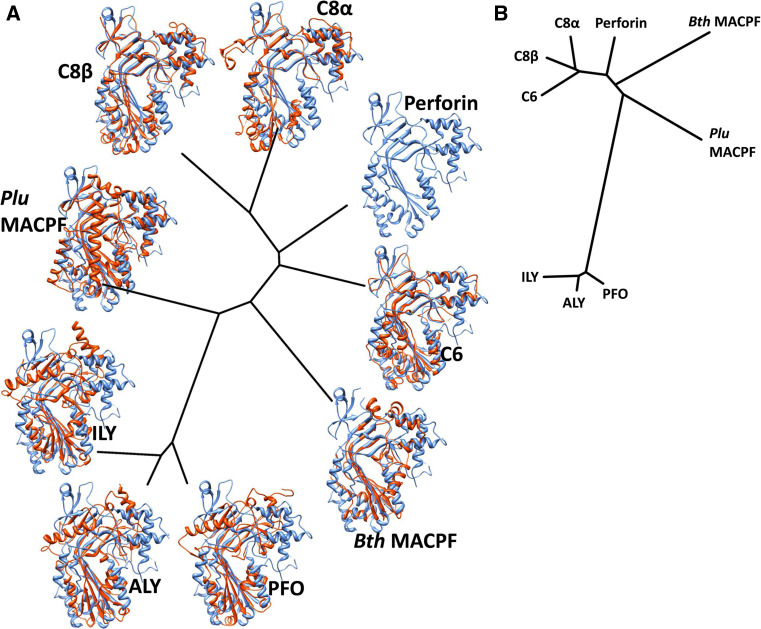

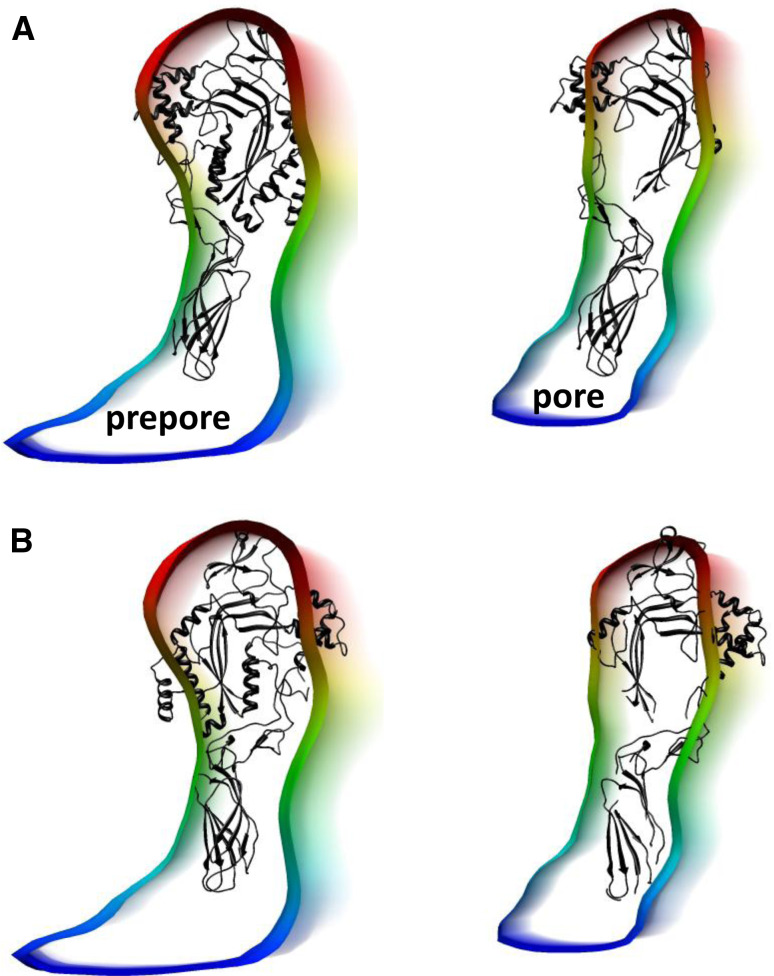

A structural superposition and phylogenetic analysis of known MACPF structures shows how very closely their folds compare, and maps the differences in structure according to a distribution matching the organismal distribution of the proteins (Fig. 3a). In Table S1 (see Supplementary Information, available online), we list the root mean square deviations and number of equivalences observed between each pairwise superposition performed. On a prokaryotic branch to the phylogeny lie the CDC structures, on a eukaryotic branch the cluster of mammalian MACPF structures (C6, C8α and β and PFN), and between them the two prokaryotic MACPFs with determined structures. It is notable that PFN is found between C6 and the C8 pair, which have been shown [13, 33, 35] to form pores in the same orientation as the CDCs [6, 10, 11]. The assembly of complement proteins C5b-9 creates an arc-shaped assembly [13, 34], displaying the same kind of inherent curvature observed for the CDC pneumolysin (PLY) from Streptococcus pneumoniae [6, 10, 11] and inferred from crystal structures [33, 35]. Because a hinge point has been identified between the upper and lower segments of the MACPF/CDC domain and different family members adopt different degrees of openness about this hinge [13, 34], we also performed the phylogenetic analysis using the upper segment only (Fig. 3b, Table S2—see Supplementary Information, available online), although the degree of openness found is presumably an evolved feature of the structures itself. Nevertheless, this showed a broadly similar appearance to the tree constructed using all of each MACPF/CDC domain except that the positions of PFN and C6 were altered, the bacterial MACPFs seemed more distant and the CDCs more distant still. In some ways, this makes a more compelling case for the similarity of mechanism and pore assembly of all MACPF and CDC proteins.

Fig. 3.

Structural phylogenetic tree of determined CDC and MACPF structures. a The structures were superimposed and the pairwise all-pairs root mean square deviations were computed using SHP [40, 126] from which evolutionary distances were derived. The tree representation was generated using the programs FITCH and DRAWTREE as part of the PHYLIP package [127]. Structures were displayed using CHIMERA [38] with the PFN structure in blue and each fitted structure in orange. See Table S1 (Supplementary Information, available online) for RMSDs and numbers of structurally equivalent residues. b As a, for the upper segment [13] of each domain only. See Table S2 for RMSDs and numbers of structurally equivalent residues

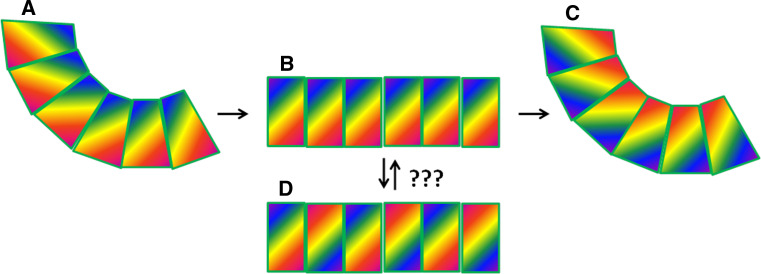

When the structure of atomic PFN was reported, it was, however, modeled based on fits of the structure in alternative conformations, into a cryo-electron microscopy (EM) model of the pore in a 180° rotated orientation to that found in the CDCs and complement proteins [37]. The difference in correlation coefficient reported for the alternative fits was, however, very modest (0.57 vs. 0.51 computed using Chimera [38]). There appeared to be a fundamental problem with this conclusion: the MACPF/CDC family has manifestly conserved two key mechanisms within their domain fold that all family members share, oligomerization into a ring and the targeting of membranes within which the vast majority (if not all) contribute to the formation of a pore. We have just shown that the domains themselves are closely conserved and that PFN is much more similar to C6 and C8α and β (whichever way the phylogeny is constructed) than any of the mammalian proteins is to the CDCs; given that complement proteins are known to use the same subunit arrangement to generate a pore-forming oligomer as the CDCs do, one would expect PFN to as well. Oligomerization into a ring requires, to a first approximation, a sector shape to the subunit so that curvature and ring closure can be achieved with a greater surface area per subunit present at the outer edge of the oligomer to that presented at its inner face (Fig. 4). If PFN had evolved to have curvature in the opposite direction then one would hardly expect its structure to phylogenetically align between C8α and C6 (Fig. 3a), or to cluster with them so far from the bacterial CDCs in the alternative tree (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, molecular evolution is a gradual process, which is why it provides a basis for phylogeny, whether by sequential comparison as in the paradigmatic work on 16S rRNA sequences [39] or by structural analysis as in the systematic recent work done on viruses [40–44]. To evolve from curvature in one direction to curvature in another requires an intermediate with no curvature which would have had no function since PFN function, like that of other MACPFs and CDCs, depends on oligomerization into a ring (Fig. 4). It therefore could not have been selected for, and would have resulted in PFN occupying a far more distant structural relationship to C6 and C8α and β than it actually does. Thus, the close structural homology between PFN and the complement proteins makes the model for pore formation proposed by Law et al. [37] unlikely to be correct.

Fig. 4.

Schematic of gradual evolution from oligomerization with one curvature to oligomerization with another. The sector shapes represent subunits within a curved oligomer such as that formed by CDCs, complement and PFN. CDCs and complement show the lefthand curvature (a); it is proposed [37] that PFN adopts the righthand curvature (c). This would require an essentially no-curvature intermediate (b) which would be inactive and unselectable. It could also have the property of mixed oligomerization (d), which might seem unlikely for a protein, but perhaps no more so than such a switch in handedness of oligomerization such as that proposed between CDCs and complement, and PFN

In order to investigate further the oligomerization of CDCs, complement, and PFN, we made a direct comparison of the structures proposed and performed some additional fits to the cryo-EM map of the pore form of PFN [37]. The first evidence of a specific interaction between PFN subunits within oligomers was of a salt bridge formed between residues Arg213 and Glu343 [30]. Our structural superposition (Fig. 3) shows us that the equivalent residues in C6 are Arg335 and Ala467, in C8α they are Lys302 and Gln432, and in C8α they are Asp281 and Glu414, and consulting the model of the MAC built by Aleshin, Liddington, and colleagues [13], we find that this point of interaction between subunits is maintained in their structure, the relevant residues on adjacent subunits being directly in contact. By superposition we built an 18-subunit model of PFN (an observed stoichiometry) using the template provided by the MAC (Fig. 5a), which is shown compared to the MAC model itself. Although this is a theoretical model, its basis in high-resolution crystal structures makes it highly robust. To enable a direct comparison between this model and the published cryo-EM reconstruction of PFN, we computed an electron density map that shows similar features to the PFN map (Fig. 5b), however, we find that the C2 domain of PFN is splayed out from the oligomeric ring in a way that is not observed in the cryo-EM map, such that the individual C2 domains are not in contact with each other. If this domain rotated towards the center of the ring about a hinge between it and the MACPF domain then this difference between the MAC-based model and the cryo-EM map would be lost. It has already been shown [37] that flexibility occurs about this region, and in Fig. 5c we show how the fit of the PFN model based on the MAC to the cryo-EM reconstruction is greatly improved by rotating the PFN model but could clearly be improved still further by a rotation at the MACPF-C2 domain intersection hinge [37].

Fig. 5.

Oligomerization of MACPF/CDC proteins. a Left structure of a perforin pore based on the complement membrane attack complex (MAC) inferred from crystallographic studies of C6 and C8 [13, 34, 35] using the model constructed by Aleshin and colleagues. This model preserves the salt bridge identified in PFN oligomers [30]; the location of the Arg213 side chain is colored blue, and that of the Glu343 side chain red. Right The same model with the MAC superimposed. b Left The PFN cryo-EM map determined by Law et al. [37], colored by height; center top and side views of a surface representation of a map computed for the PFN pore model based on the MAC (a); the similar morphology of a single PFN subunit found in this model compared to the cryo-EM map is outlined with a broken black line in each case; right a surface representation of the MAC model. c Top a comparison of the cryo-EM map [37] (solid surface) and the PFN model based on the MAC structure (mesh) with the PFN structure shown within as a ribbon, arrows representing flexible movements that would improve the fit; bottom rotation of the PFN model provides an improved fit and additional intramolecular flexibility as indicated would improve it still further

Another insight from the cryo-EM reconstruction reported by Law et al. was that the PFN pore does not have the same doubled-over appearance as the CDC pore, and this is echoed in findings we made in which we were able to identify pre-pore and pore-forming conformations of PFN oligomerized on membranes [31] (Fig. 6). This lack of a collapse is presumably due to the absence in PFN of the elongated thin β-sheeted domain that links the CDCs’ pore-forming domain to their membrane-binding domain. As shown in Fig. 6, the capturing of pre-pore and pore states of the molecule does highlight the likely orientation of PFN in the same orientation as the CDCs, because the subunit conformation is much more similar in the pre-pore form than the pore form to the conformation of the isolated protein found in its crystal structure [37] (as also in the CDCs [6, 10, 11, 31]). The published data on pre-pore and pore forms of PFN are not discussed in a recent review [45], but we include them here because they provide important additional details about the mechanism of pore formation (and its similarity to that of CDCs) and assist in identification of the correct orientation for the protein subunit in the functional pore.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of prepore and pore subunit profiles. a Prepore (left) and pore (right) subunit profiles as reported previously [31] fitted with the PFN crystal structure with (left, prepore) and without (right, pore) TMH regions of the MACPF/CDC domain. b As a for the orientation proposed by Law et al. [37]

Formation of membrane pores

An essential starting point for understanding the basis of pore formation by proteins from the MACPF/CDC superfamily is the realization that the word “pore” is a functional description and not a structural one. Thus, pores through membranes may be formed during electroporation [46] or membrane fusion [47, 48] and may consist of structures comprising exclusively protein [49] or a matrix of protein and lipid [50, 51] or a protein annulus that opens and closes to the lipid bilayer interior by turns [52]. If one confuses the structures observed by the application of biophysical imaging techniques such as cryo-electron microscopy [53, 54] and X-ray crystallography [49, 55] as necessarily providing an exclusive definition of the mechanism of pore formation, then it can seem impossible to accommodate well-attested functional data within a mechanistic paradigm. For example, α-toxin from Staphylococcus aureus may have been solved as a crystallographic heptameric oligomer [49], which forms a membrane pore, but there is good evidence from atomic force microscopy that in addition to heptamers α-toxin also forms hexameric oligomers [56], which functional data suggest also form pores [57] (the possibility that the AFM data are artefactual notwithstanding). While the structure of two-component staphylococcal hemolysin was reported as an octameric oligomer [58], hexamers [59] and perhaps even heptamers [60] were shown to form pores, though a stable bicomponent oligomer presumably requires a balanced set of equivalent interactions. There are ample functional data from single-channel conductance measurements, imaging and pore blockage/lysis protection assays, which show that MACPF/CDC superfamily proteins can form pores of a range of sizes among which are some that cannot be accounted for by the complete oligomeric rings of subunits visualized by electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy (see below and Fig. 7a), despite the limited variation observed in inter-subunit rotational angle and thus in diameter [6, 10, 11, 31, 37]. Any model for pore formation that does not explain such data must be considered to be inadequate. Rather, while oligomeric rings of subunits do form pores [6, 10, 11, 31], this cannot exhaust descriptions of how pores can be formed by the MACPF/CDCs.

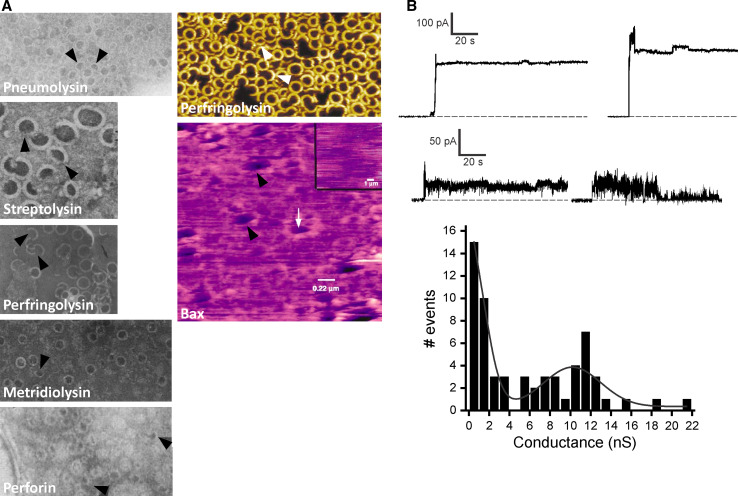

Fig. 7.

Diversity of MACPF/CDC pores. a Images of pores formed by proteins by negative stain electron microscopy for PLY [53], SLO [65], PFO [54], metridiolysin from the sea anemone Metridium senile [67] and PFN [70] and by atomic force microscopy (AFM) for PFO [63] and for the apoptotic protein Bax [95]. Arc pores or other forms of proteolipid complexes are shown by arrowheads. Reprinted from references [53] with permission from The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, [54, 67, 70, 95] with permission from Elsevier, [65] with permission from American Society for Microbiology and with permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd [63]. b Examples of diverse PFN pores formed in 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycerophosphocholine. Large pores with conductance more than 5 nS (above) and small with conductance below 1 nS (below) are shown. The current was measured at a constant voltage of +40 mV. The buffer used was 100 mM KCl, 20 mM HEPES, 100 μM CaCl2, pH 7.4. Conductance histogram of 61 step-like increases recorded from 53 independent single-channel experiments shows two peaks at approximately 500 and 10,000 pS (below)

The detailed molecular mechanism of CDC-mediated pore formation is well established at the single subunit level. Scanning mutagenesis, which places fluorescently labeled amino acids sequentially, has been used to identify in the CDC PFO the positioning of residues within the hydrophobic membrane or polar aqueous environments, revealing that two β-hairpins are formed from α-helices in D3 to produce a pore [61] (Fig. 1). This refolding produces a continuous β-sheet slab that extends from the top of the molecule into the membrane, where it is thought to form a β-barrel similar to porins and α-toxin [49]. Cryo-EM reconstruction of PLY oligomers indicated that the CDC subunit is oriented with the refolded portion of the structure facing towards the center of the ring-shaped pore [10, 11]. Using PFO mutants containing two strategically inserted cysteines that reversibly inhibit the pore forming step, the mechanism underlying the conformational change was found to involve a discrete pre-pore to pore transition similar to that of α-toxin [62]. In the pre-pore state, the oligomers assume a conformation observed in the aqueous phase. During pore formation, a doubling over of the molecule brings the CDC within striking distance of the membrane, enabling membrane puncture [11, 63]. The mechanical basis for the refolding appears to rely on a strong homotypic affinity of the subunits leading to their multimerization into the pre-pore and pore structures [62–64].

Electron microscopy has been the primary technique used to view (and define) the oligomeric pores of CDCs that presumably cause lysis, e.g., of PLY [53], Streptococcus pyogenes streptolysin (SLO) [65] and PFO [54]. However, both ring-shaped and arc-shaped oligomers have been identified (Fig. 7a) [53, 65], thus either or both structures may be responsible for the observed hemolytic activity. Indeed, since pores have been visually identified by their pattern of negative staining, it remains unclear whether accumulated stain reflects the presence of an authentic pore, or instead a stained superstructure located above the membrane that resembles a pore. Our understanding is further complicated by the possibility that incomplete oligomers imaged through EM could be generated from rings disrupted during sample preparation. However, many MACPF/CDCs have been observed to form both these structures and identical pore morphologies have been noted for related proteins from animals as well as from prokaryotes [53, 65–69] (Fig. 7a). Why should one think these structures are not artefacts caused by mechanical disruption of ring-shaped oligomers during preparation for microscopy? Firstly, in many cases the apparently pore-forming arcs are observed within continuous membrane sheets as for example quite clearly in the cases of PLY and SLO in Fig. 7a. Membranes are much more liable to tearing, for example, than CDC oligomers, so if the CDC oligomer resides within a complete fragment of membrane, it is unreasonable to suggest that it has been damaged. Secondly, the atomic-force microscopy (AFM) imaging of pores formed by PFO showed that that the technique does not disrupt oligomers, at least [63]. As we have rehearsed elsewhere [6], this conclusion can be drawn from the fact that PFO pores which form in a native-like fashion in which pre-pore transition to a pore occurs at a kinetically determined time are ~50 % incomplete when imaged by AFM. If, however, the pore formation is arrested at the pre-pore stage with an engineered locking disulphide bridge, then when the lock is reduced pores form, but they are essentially 100 % complete when imaged by AFM. It is not the imaging method that determines whether complete or incomplete (arc) oligomers form pores, but the kinetics of oligomerization of the proteins in the first place.

Like CDCs, MACPF proteins form incomplete arc-shaped oligomers (Fig. 7a). These structures have the appearance of pores and, as seen with CDCs, exist within otherwise continuous membrane sheets. Indeed, the presence of “incompletely polymerized tubules” [70] and “incomplete rings” [71] was noted in the original papers describing PFN. Moreover, such structures have even been observed in myocardial tissue from an individual suffering from acute myocarditis [72]. The MAC is the functional pore formed by complement and although heterogeneous in size and usually ring-shaped, arc morphologies are also formed by these proteins [73, 74]. In addition, the limited complex C5b-8 without having any complete ring structure has been shown to have pore-forming activity at high concentrations [75]. The pore-forming activity of MACPF/CDCs has been much-studied in planar lipid membranes. In several studies, the co-presence of small pores, i.e., slow current increases with unresolved transitions, and big pores viewed as sudden jumps in current were observed. Again, in a recent study using purified native human PFN, it was shown that two populations of pores were formed: small pores (conductance less than 2 nS) were always associated with high noise and exhibited an unstable character, while larger pores (conductance above 2 nS) were usually associated with low noise (Fig. 7b) [31]. The mode of pore opening was highly dependent on the membrane composition, which may suggest a lipid component to the pore itself. The gradual increase in ionic current with associated small pores has been described for the MACPF/CDCs sphaericolysin [76], PLY [77, 78], a CDC listeriolysin (LLO) from Listeria monocytogenes [79] and PFN [31, 80–83]. Cryo-EM data also revealed the co-presence of pores with variable diameter on the surface of large unilamellar vesicles [31]. Planar lipid membrane observations are thus in agreement with EM data and suggest that different pore forming mechanisms and architectures exist, at least with the lipid compositions used.

The standard pre-pore to pore model of membrane insertion by CDCs, extended by homology to MACPF proteins, cannot fully account for the strikingly varied biophysical and biological behavior displayed by these molecules. Smaller oligomers appear to form smaller pores [66], but the limited variation in the curvature of MACPF/CDC rings suggests these might derive from arcs. Also, in a seemingly implausible outcome for a membrane-inserted conduit predicted to have a diameter of ~35 nm, certain MACPF proteins and CDCs allow only calcium influx [84–87] and smaller pores can be shut by zinc ions, with a diameter of ~0.1 nm [78, 88]. Although the molecular events that modulate the broad range of pore diameters generated by CDCs and MACPF proteins remain unclear [17, 71, 80, 84, 89], such observations might be reconciled by accepting that the pre-pore state itself could be an arc or a ring and thus that either could form a pore [6, 63, 66]. The use of alternative imaging methods that distinguish these pore states as well as techniques for probing their functionality are clearly needed to address these important issues, but recent cell biology data [89–91] are clearly in agreement with the biophysical data showing a very wide range of different pore sizes.

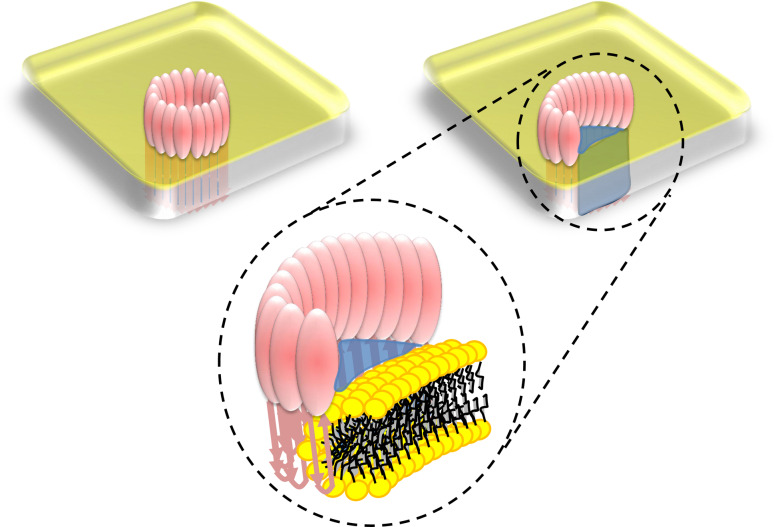

As proposed 27 years ago, if arcs are functional pores then the channel should be lined by a mixture of protein and lipid [65] (Fig. 8). Cellular electroporation provides us with a model system to describe how phospholipid headgroups can be arranged to form a “toroidal” pore by continuous arrangements of lipids. In electroporation the membrane is stimulated with an electrical field to form a highly curved surface in which the lipid headgroups face each other around a central aqueous column [46, 92] offering proof of principle that phospholipids may indeed undergo re-arrangement through the depth of the lipid bilayer. Proteins that participate in viral fusion and apoptosis as well as certain pore-forming proteins and anti-bacterial peptides are predicted to form toroidal pores [50, 51, 93–98]. The normal planar lamellar architecture disfavors a highly curved surface for the plasma membrane in such pores. However, peptides or proteins absorbed to it could destabilize the bilayer by stretching or disruption of the lipid packing so that it forms such an arrangement. Although reliable investigative methodology is still emerging to study toroidal pores, structural information is available describing the arrangement of lipids and protein in a toroidal pore formed by the peptide derived from the pro-apoptotic protein Bax. Applying X-ray diffraction to a membrane containing brominated lipid headgroups clearly shows that Bax peptide induces pores lined with phospholipid headgroups [51]. An equivalent lipid arrangement occurs during membrane fusion, where again a proteo-lipid assembly is central [47, 48]. The toroidal lipid structures generated by Bax, antibacterial peptides, and in fusion pores will differ markedly in structure from those formed by CDCs or MACPF proteins. For Bax and fusion pores, the peptide is distributed around the pore circumference. For CDCs and MACPF proteins arciform pores, one side would consist of protein and the other of lipid headgroups. Another concern is that the edges of the β-sheet that CDCs insert in the bilayer will have hydrogen bonding requirements. Energetics may be satisfied, however, by lipid headgroups and aqueous counter ions. In addition, in a recently determined structure of the pore-forming protein lysenin in complex with sphingomyelin [99] we observed how an acyl chain can line the edge of a β-sheet held in place by ring stacking-like interactions with two tyrosines. Similar interactions at the open ends of MACPF/CDC arcs could explain their stabilization in the membrane. Consulting our structural superposition (Fig. 3) we find that there are between 2 (PFN, PFO and C8α) and 8 (C8β) tyrosine or phenylalanine residues in TMH1 (3: ILY, ALY, C6; 5: Bth; 6: Plu) and between 1 (PFN, ILY, C6, C8α and C8β) and 3 (PFO, Plu, ALY, Bth) in TMH2, which suggests a selected difference between the two. It is well known that aromatic amino acid side chains are found at the headgroup-tail interface of membrane proteins but these examples include Phe and Tyr residues throughout the TMH regions and in any case the ring stacking-type interactions observed in the lysenin-sphingomyelin crystal structure may in fact snapshot the interactions such aromatic paddles enjoy with the bilayer. The presence of this residue distribution suggests that a lipid-protein interface experienced by MACPF/CDC proteins could be stabilized by the same kind of interactions relating lysenin to the sphingomyelin acyl chain and that this may be more associated with TMH1 than TMH2. The idea that CDCs form arc-defined pores is not novel, but remains a neglected area of study that warrants renewed pursuit. While the toroidal pores directly observed to date [51, 95] would have a different architecture to those formed by MACPFs and CDCs (Fig. 8), they do show that such arrangements of lipids can be induced by proteins in membranes, with major functional implications as shown below.

Fig. 8.

How might arcs form pores? Top left shows a schematic for a ring of MACPF/CDC subunits forming a pore, with TMHs inserted below the ring sitting atop the yellow-colored membrane surface. Top right shows a similar representation for an incomplete ring (an arc of subunits) in which the pore (blue fluid) is formed at the interface between the protein oligomer and the yellow-colored membrane. Below shows a detailed view of the pore formed by an arc with the lipids in a toroidal arrangement, as originally proposed for CDCs by Sucharit Bhakdi and colleagues [65], and as found in Bax- [51] and electrically formed pores [46, 92]

Biological roles of MACPF/CDC proteins

The obvious function of large pores formed by MACPF/CDCs is cell lysis, resulting in the death of target cells. The large size of the pore may also suggest that they can be used for molecular transport. In CDCs, a translocation of NAD glycohydrolase into keratinocytes was shown to be enabled by SLO [100], but no other examples are known.

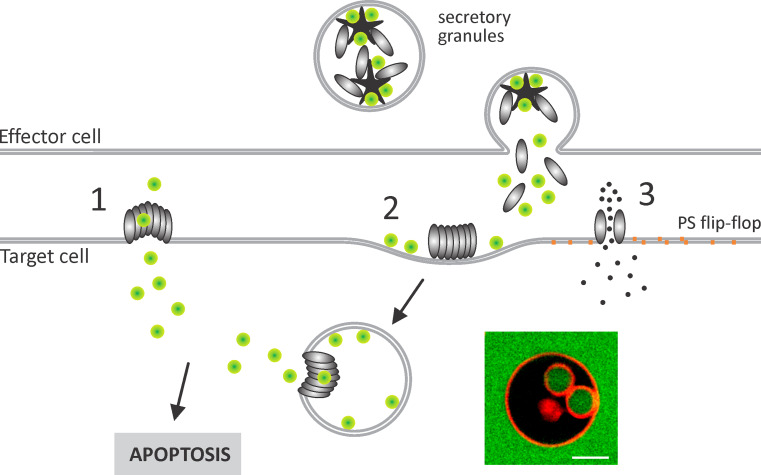

The transport role is, however, clear for PFN, where its main role is in the delivery of cytotoxic proteases known as granzymes, particularly granzyme B (GrB), to the cytosol of the target cells where they induce apoptosis [19]. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) or natural killer cells recognize target cells and form an immunological synapse; secretory granules then fuse with the plasma membrane and allow the release of PFN and other toxic molecules into the synapse. PFN is then able to interact with the plasma membrane of target cells, which is clearly one of the sites where GrB translocation may occur (Fig. 9). Large pores formed by PFN were thoroughly described in many model lipid systems and they were long considered as the primary entrance site of GrB to the cytosol of target cells [1, 70]. However, large beta-barrel pores have not yet been imaged in physiological conditions at the site of attack. PFN membrane interactions and pore-forming activity is dependent upon calcium ion concentration [32, 101] and pH [101], which are not exactly known for the immunological synapse. Also, the local concentration of PFN may vary substantially and all of these factors can affect the interaction of PFN with the target membranes and subsequent pore formation. However, PFN pores were shown to induce transient calcium ion influx into the target cells after exposure to sublytic concentrations of PFN [89, 102] or under CTL attack [89], which further complicates an understanding of the kinetics of events at the immunological synapse. Calcium influx can trigger a membrane-damage response, which by fusing of intracellular vesicles rapidly reseals the damaged membrane and thus limits the damage due to pore formation (for details see the review by Pipkin and Lieberman [84]). There is, therefore, a time window in which GrB can be delivered into the cells. It was also recently shown that a 5-min pulse of PFN and GrB was sufficient for induction of apoptosis [102], and additionally, small PFN pores were shown to induce phosphatidylserine flip-flop and this correlated with subsequent GrB-induced apoptosis. It was proposed that GrB may simply translocate through PFN structures that enable flip-flop [102].

Fig. 9.

Transfer of GrB into the cytosol of target cells. GrB (green circles) is stored together with PFN (gray ovals) in the secretory granules of the effector cells where it is bound to serglycin (star-like shape). Upon target cell recognition, secretory granules are fused with the plasma membrane and the contents are released in the immunological synapse. GrB transfer into the cytosol of the target cells may occur at the level of the plasma membrane through barrel-stave (1) or smaller pores that may contain a lipid component (3). In the “endosomolysis” model (2), GrB is released from giant endosomes, gigantosomes, by the aid of PFN. Endocytosis is facilitated by the cell response due to calcium (black dots) influx through small PFN pores (3) and by active engagement of PFN. Small PFN pores also induce rapid flip-flop of phosphatidylserine (orange squares), as shown for the upper leaflet on the right side of the pore. The fluorescent image shows internal vesicles that resemble gigantosomes in cells, formed in the GUV in the presence of PFN [106]

GrB was also found to undergo endosome-directed endocytosis. PFN, co-endocytosed with GrB, subsequently created an endosomolytic milieu that facilitates the movement of the protease to the cytosol [103–105] (Fig. 9). This second model for transfer of GrB into the cells, the so-called endosomolysis model, has gained more experimental support in recent years. Entry of calcium into the cells and consequent damaged-membrane response led to enhanced endocytosis of PFN and GrB [89–91]. Large endosomes, termed gigantosomes, which are formed as a result, contain both PFN and GrB and PFN pores in gigantosomes then subsequently allow gradual release of GrB [91]. It was also shown that PFN can induce endocytic-like events in model membranes. PFN induced rapid formation of invaginations and internal vesicles in giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) (Fig. 9) and other model lipid systems, such as large unilamellar vesicles and planar lipid bilayers, and in Jurkat cells [106]. The invaginations were induced by calcium-dependent binding of PFN and its clustering on the surface of the membrane. The resulting internal vesicles contained fluorescent markers, and also Alexa-labeled GrB, which were added to the surrounding medium. The formation of internal vesicles was rapid and completed within minutes, and thus perfectly in the line with the timescale of events observed in a cellular context. On the contrary, the diffusion of GrB and other fluorescent probes of similar size through pores formed in the primary vesicle was much slower [31, 106].

The experiments in model lipid systems thus agree well with the endosomolysis model and indicate that PFN is actively engaged in the endocytotic process through membrane interactions, in addition to pore formation. Which of the two routes for GrB is operable thus depends greatly on the conditions within the immunological synapse, amounts of PFN that are in the contact with the membrane, and the plasma membrane dynamics after the encounter with PFN [107]. Changes in membrane morphology are not an unusual result of protein binding to one of the membrane leaflets, as highlighted by the ability of some eukaryotic proteins to affect membrane curvature and induce formation of internal or external vesicles in membranes independent of cellular endocytotic mechanisms [108–110]. Indeed, the CDC PLY also affects membrane curvature as a consequence of membrane binding [111]. The interaction of MACPF/CDCs with the membranes may thus in general change membrane morphology and may be relevant also for other biological processes where they are involved.

The complex role MACPF/CDC proteins can have for the biology of their producing organisms is highlighted by apicomplexan parasites. The PFN-like proteins (PLPs) produced by apicomplexan parasites were first identified by sequence analysis and have quickly been found to have major importance in their life cycles. The malarial parasite Plasmodium goes through a series of developmental forms in its life cycle, which makes use of two hosts: a mammalian one in which the primary replicative stages are in the liver and in erythrocytes (the symptomatic stage of the disease), and an insect host in which replication occurs in the midgut [112]. Cell invasion has two forms: traversal and infection. Traversal is rapid and the parasite simply passes through the cytosol, before appearing to exit without damaging the cell; infection is slow and results in the parasite residing in a parasitophorous vacuole (PV). Traversal is thought to be the mode of movement into the mosquito gut wall and probably also its salivary glands [113, 114]; it is known to be the mode of movement through the epidermis, avoiding macrophages [115, 116], and in initial movement into the liver [117–119]. The basis of traversal was unknown until recently, but now the Plasmodium PLPs (the PPLPs) have been pinpointed as the proteins responsible. PPLP1 is critical for cell traversal—importantly in the dermis, where it allows evasion of leukocyte macrophages [115]. PPLP2 is expressed in the merozoite stage of the life cycle [120], while PPLP3 knockout prevents midgut wall invasion and the mutant parasites remain instead attached to the epithelium [121]. PPLP4 is known to also be expressed in the ookinete [122, 123]. A PPLP5 knockout has the same phenotype as the PPLP3 knockout. The similar phenotypes for PPLPs 3 and 5 show that they either act together within a complex, or sequentially on the same pathway, but they cannot compensate for each other [113, 114]. In the apicomplexan Toxoplasma an essential role for one of the two apparent PLPs in its genome (TgPLP1) was found at the egress of tachyzoites from cells [124]. So, Plasmodium and Toxoplasma parasites utilize MACPF proteins during their life cycles. In their case the pores could explain their ability to apparently glide directly into and out of cells [115, 124]. This could best happen through an inherently transitory pore, and not by a general disruption caused by one or many ring pores which are individually far too narrow for a sporozoite or tachyzoite to pass through. Likewise, we would argue that Listeria species could translocate through small proteo-lipid pores in membranes via their CDC, LLO [85, 86] and so promote the maintenance of plasma membrane integrity after passage. In all these roles, an extensible pore diameter provided by an arc–lipid interface would be highly advantageous, providing flexibility and versatility in membrane penetration while at the same time only transiently disturbing the integrity of the targeted cell or subcompartment.

Conclusions

Structural biology approaches to the study of pore-forming proteins from the MACPF/CDC family have proved immensely informative, giving snapshots of the monomeric structures at high resolution by X-ray crystallography and of the pore-forming complexes at lower resolution by electron microscopy and other techniques. At the same time, functional studies using cell biological and biophysical techniques have underscored the diverse way in which the proteins function. Our review draws together data from the various techniques being used and shows how their combination is necessary to allow an accurate understanding of the diverse ways in which these proteins function. That function was transparently a priceless evolutionary discovery: it has exerted a conserving selective pressure from the last common ancestor of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Homo sapiens, at least.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Tilen Praper for the work performed with planar lipid bilayers and Robert Liddington and Alexander Aleshin for discussion and for providing the model of the complement membrane attack complex. R.J.C.G. is a Royal Society University Research Fellow and the Oxford Division of Structural Biology is part of the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics, Wellcome Trust Core Award Grant Number 090532/Z/09/Z.M.D.S. would like to thank the Nanosmart project from the Provincia Autonoma di Trento for support. G. A. would like to thank the Slovenian Research Agency for support.

Abbreviations

- ALY

Anthrolysin

- Bth

Bacillus thetaiotaomicron MACPF protein

- CDCs

Cholesterol-dependent cytolysins

- CTL

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes

- EM

Electron microscopy

- GrB

Granzyme B

- ILY

Intermedilysin

- LLO

Listeriolysin

- MACPF

Membrane attack complex/perforin

- MAC

Membrane attack complex

- PFN

Perforin

- PFO

Perfringolysin

- PLY

Pneumolysin

- PLPs

Perforin-like proteins

- Plu

Photorhabdus luminescens MACPF protein

- PPLPs

Plasmodium perforin-like proteins

- PV

Parasitophorous vacuole

- SLO

Streptolysin

- TMH

Trans-membrane hairpin (present in the soluble forms of CDC/MACPFs as α-helices)

Contributor Information

Robert J. C. Gilbert, Phone: +44-1865-287535, FAX: +44-1865-287547, Email: gilbert@strubi.ox.ac.uk

Gregor Anderluh, Phone: +386-1-4760261, FAX: +386-1-4760300, Email: gregor.anderluh@ki.si.

References

- 1.Tschopp J, Masson D, Stanley KK. Structural/functional similarity between proteins involved in complement- and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-mediated cytolysis. Nature. 1986;322:831–834. doi: 10.1038/322831a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosado CJ, Buckle AM, Law RH, Butcher RE, Kan WT, Bird CH, Ung K, Browne KA, Baran K, Bashtannyk-Puhalovich TA, Faux NG, Wong W, Porter CJ, Pike RN, Ellisdon AM, Pearce MC, Bottomley SP, Emsley J, Smith AI, Rossjohn J, Hartland EL, Voskoboinik I, Trapani JA, Bird PI, Dunstone MA, Whisstock JC. A common fold mediates vertebrate defense and bacterial attack. Science. 2007;317:1548–1551. doi: 10.1126/science.1144706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hadders MA, Beringer DX, Gros P. Structure of C8alpha-MACPF reveals mechanism of membrane attack in complement immune defense. Science. 2007;317:1552–1554. doi: 10.1126/science.1147103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slade DJ, Lovelace LL, Chruszcz M, Minor W, Lebioda L, Sodetz JM. Crystal structure of the MACPF domain of human complement protein C8 alpha in complex with the C8 gamma subunit. J Mol Biol. 2008;379:331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.03.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosado CJ, Kondos S, Bull TE, Kuiper MJ, Law RHP, Buckle AM, Voskoboinik I, Bird PI, Trapani JA, Whisstock JC, Dunstone MA. The MACPF/CDC family of pore-forming toxins. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:1765–1774. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01191.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert RJ. Inactivation and activity of cholesterol-dependent cytolysins: what structural studies tell us. Structure. 2005;13:1097–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hotze EM, Tweten RK. Membrane assembly of the cholesterol-dependent cytolysin pore complex. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1818:1028–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrand AJ, LaChapelle S, Hotze EM, Johnson AE, Tweten RK. Only two amino acids are essential for cytolytic toxin recognition of cholesterol at the membrane surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:4341–4346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911581107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giddings KS, Zhao J, Sims PJ, Tweten RK. Human CD59 is a receptor for the cholesterol-dependent cytolysin intermedilysin. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:1173–1178. doi: 10.1038/nsmb862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilbert RJ, Jimenez JL, Chen S, Tickle IJ, Rossjohn J, Parker M, Andrew PW, Saibil HR. Two structural transitions in membrane pore formation by pneumolysin, the pore-forming toxin of Streptococcus pneumoniae . Cell. 1999;97:647–655. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80775-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tilley SJ, Orlova EV, Gilbert RJ, Andrew PW, Saibil HR. Structural basis of pore formation by the bacterial toxin pneumolysin. Cell. 2005;121:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farrand S, Hotze E, Friese P, Hollingshead SK, Smith DF, Cummings RD, Dale GL, Tweten RK. Characterization of a streptococcal cholesterol-dependent cytolysin with a Lewis y and b specific lectin domain. Biochemistry. 2008;47:7097–7107. doi: 10.1021/bi8005835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aleshin AE, Schraufstatter IU, Stec B, Bankston LA, Liddington RC, DiScipio RG. Structure of complement C6 suggests a mechanism for initiation and unidirectional, sequential assembly of membrane attack complex (MAC) J Biol Chem. 2012;287:10210–10222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.327809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Punta M, Coggill PC, Eberhardt RY, Mistry J, Tate J, Boursnell C, Pang N, Forslund K, Ceric G, Clements J, Heger A, Holm L, Sonnhammer EL, Eddy SR, Bateman A, Finn RD. The Pfam protein families database. Nuc Acids Res. 2012;40:D290–D301. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Beurden SJ, Bossers A, Voorbergen-Laarman MH, Haenen OL, Peters S, Abma-Henkens MH, Peeters BP, Rottier PJ, Engelsma MY. Complete genome sequence and taxonomic position of anguillid herpesvirus 1. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:880–887. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.016261-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang S, Yuan S, Guo L, Yu Y, Li J, Wu T, Liu T, Yang M, Wu K, Liu H, Ge J, Huang H, Dong M, Yu C, Chen S, Xu A. Genomic analysis of the immune gene repertoire of amphioxus reveals extraordinary innate complexity and diversity. Genome Res. 2008;18:1112–1126. doi: 10.1101/gr.069674.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ponting CP. Chlamydial homologues of the MACPF (MAC/perforin) domain. Curr Biol. 1999;9:R911–R913. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)80102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu Q, Abdubek P, Astakhova T, Axelrod HL, Bakolitsa C, Cai X, Carlton D, Chen C, Chiu HJ, Clayton T, Das D, Deller MC, Duan L, Ellrott K, Farr CL, Feuerhelm J, Grant JC, Grzechnik A, Han GW, Jaroszewski L, Jin KK, Klock HE, Knuth MW, Kozbial P, Krishna SS, Kumar A, Lam WW, Marciano D, Miller MD, Morse AT, Nigoghossian E, Nopakun A, Okach L, Puckett C, Reyes R, Tien HJ, Trame CB, van den Bedem H, Weekes D, Wooten T, Yeh A, Zhou J, Hodgson KO, Wooley J, Elsliger MA, Deacon AM, Godzik A, Lesley SA, Wilson IA. Structure of a membrane-attack complex/perforin (MACPF) family protein from the human gut symbiont Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron . Acta Crystall Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2010;66:1297–1305. doi: 10.1107/S1744309110023055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voskoboinik I, Smyth MJ, Trapani JA. Perforin-mediated target-cell death and immune homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:940–952. doi: 10.1038/nri1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Podack ER, Deyev V, Shiratsuchi M. Pore formers of the immune system. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;598:325–341. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-71767-8_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oshiro N, Kobayashi C, Iwanaga S, Nozaki M, Namikoshi M, Spring J, Nagai H. A new membrane-attack complex/perforin (MACPF) domain lethal toxin from the nematocyst venom of the Okinawan sea anemone Actineria villosa . Toxicon. 2004;43:225–228. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiens M, Korzhev M, Krasko A, Thakur NL, Perovic-Ottstadt S, Breter HJ, Ushijima H, Diehl-Seifert B, Muller IM, Muller WE. Innate immune defense of the sponge Suberites domuncula against bacteria involves a MyD88-dependent signaling pathway. Induction of a perforin-like molecule. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27949–27959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504049200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens LM, Frohnhofer HG, Klingler M, Nusslein-Volhard C. Localized requirement for torso-like expression in follicle cells for development of terminal anlagen of the Drosophila embryo. Nature. 1990;346:660–663. doi: 10.1038/346660a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams NC, Tomoda T, Cooper M, Dietz G, Hatten ME. Mice that lack astrotactin have slowed neuronal migration. Development. 2002;129:965–972. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.4.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng C, Heintz N, Hatten ME. CNS gene encoding astrotactin, which supports neuronal migration along glial fibers. Science. 1996;272:417–419. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5260.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kafsack BF, Carruthers VB. Apicomplexan perforin-like proteins. Commun Integr Biol. 2010;3:18–23. doi: 10.4161/cib.3.1.9794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morita-Yamamuro C, Tsutsui T, Sato M, Yoshioka H, Tamaoki M, Ogawa D, Matsuura H, Yoshihara T, Ikeda A, Uyeda I, Yamaguchi J. The Arabidopsis gene CAD1 controls programmed cell death in the plant immune system and encodes a protein containing a MACPF domain. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005;46:902–912. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lukoyanova N, Saibil HR. Friend or foe: the same fold for attack and defense. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:51–53. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderluh G, Lakey JH. Disparate proteins use similar architectures to damage membranes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:482–490. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baran K, Dunstone M, Chia J, Ciccone A, Browne KA, Clarke CJ, Lukoyanova N, Saibil H, Whisstock JC, Voskoboinik I, Trapani JA. The molecular basis for perforin oligomerization and transmembrane pore assembly. Immunity. 2009;30:684–695. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Praper T, Sonnen A, Viero G, Kladnik A, Froelich CJ, Anderluh G, Dalla Serra M, Gilbert RJ. Human perforin employs different avenues to damage membranes. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:2946–2955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.169417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Voskoboinik I, Thia MC, Fletcher J, Ciccone A, Browne K, Smyth MJ, Trapani JA. Calcium-dependent plasma membrane binding and cell lysis by perforin are mediated through its C2 domain: a critical role for aspartate residues 429, 435, 483, and 485 but not 491. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8426–8434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413303200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aleshin AE, Discipio RG, Stec B, Liddington RC. Crystal structure of C5b-6 suggests a structural basis for priming the assembly of the membrane attack complex (MAC) J Biol Chem. 2012;287:19642–19652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.361121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hadders MA, Bubeck D, Roversi P, Hakobyan S, Forneris F, Morgan BP, Pangburn MK, Llorca O, Lea SM, Gros P. Assembly and regulation of the membrane attack complex based on structures of C5b6 and sC5b9. Cell Rep. 2012;1:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lovelace LL, Cooper CL, Sodetz JM, Lebioda L. Structure of human C8 protein provides mechanistic insight into membrane pore formation by complement. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:17585–17592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.219766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tomita T, Noguchi K, Mimuro H, Ukaji F, Ito K, Sugawara-Tomita N, Hashimoto Y. Pleurotolysin, a novel sphingomyelin-specific two-component cytolysin from the edible mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus, assembles into a transmembrane pore complex. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:26975–26982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402676200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Law RH, Lukoyanova N, Voskoboinik I, Caradoc-Davies TT, Baran K, Dunstone MA, D’Angelo ME, Orlova EV, Coulibaly F, Verschoor S, Browne KA, Ciccone A, Kuiper MJ, Bird PI, Trapani JA, Saibil HR, Whisstock JC. The structural basis for membrane binding and pore formation by lymphocyte perforin. Nature. 2010;468:447–451. doi: 10.1038/nature09518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comp Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woese CR. Interpreting the universal phylogenetic tree. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8392–8396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riffel N, Harlos K, Iourin O, Rao Z, Kingsman A, Stuart D, Fry E. Atomic resolution structure of Moloney murine leukemia virus matrix protein and its relationship to other retroviral matrix proteins. Structure. 2002;10:1627–1636. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(02)00896-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bamford DH, Grimes JM, Stuart DI. What does structure tell us about virus evolution? Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;15:655–663. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Graham SC, Bahar MW, Cooray S, Chen RA, Whalen DM, Abrescia NG, Alderton D, Owens RJ, Stuart DI, Smith GL, Grimes JM. Vaccinia virus proteins A52 and B14 Share a Bcl-2-like fold but have evolved to inhibit NF-kappaB rather than apoptosis. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000128. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bahar MW, Graham SC, Stuart DI, Grimes JM. Insights into the evolution of a complex virus from the crystal structure of vaccinia virus D13. Structure. 2011;19:1011–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ji X, Sutton G, Evans G, Axford D, Owen R, Stuart DI. How baculovirus polyhedra fit square pegs into round holes to robustly package viruses. EMBO J. 2010;29:505–514. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dunstone MA, Tweten RK. Packing a punch: the mechanism of pore formation by cholesterol-dependent cytolysins and membrane attack complex/perforin-like proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2012;22:342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teissie J, Golzio M, Rols MP. Mechanisms of cell membrane electropermeabilization: a minireview of our present (lack of ?) knowledge. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1724:270–280. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Almers W. Fusion needs more than SNAREs. Nature. 2001;409:567–568. doi: 10.1038/35054637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kielian M, Rey FA. Virus membrane-fusion proteins: more than one way to make a hairpin. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:67–76. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song L, Hobaugh MR, Shustak C, Cheley S, Bayley H, Gouaux JE. Structure of staphylococcal alpha-hemolysin, a heptameric transmembrane pore. Science. 1996;274:1859–1866. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Basanez G, Sharpe JC, Galanis J, Brandt TB, Hardwick JM, Zimmerberg J. Bax-type apoptotic proteins porate pure lipid bilayers through a mechanism sensitive to intrinsic monolayer curvature. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49360–49365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qian S, Wang W, Yang L, Huang HW. Structure of transmembrane pore induced by Bax-derived peptide: evidence for lipidic pores. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:17379–17383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807764105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsukazaki T, Mori H, Fukai S, Ishitani R, Mori T, Dohmae N, Perederina A, Sugita Y, Vassylyev DG, Ito K, Nureki O. Conformational transition of Sec machinery inferred from bacterial SecYE structures. Nature. 2008;455:988–991. doi: 10.1038/nature07421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morgan PJ, Hyman SC, Byron O, Andrew PW, Mitchell TJ, Rowe AJ. Modeling the bacterial protein toxin, pneumolysin, in its monomeric and oligomeric form. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25315–25320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Olofsson A, Hebert H, Thelestam M. The projection structure of Perfringolysin O (Clostridium perfringens [theta]-toxin) FEBS Lett. 1993;319:125–127. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mueller M, Grauschopf U, Maier T, Glockshuber R, Ban N. The structure of a cytolytic alpha-helical toxin pore reveals its assembly mechanism. Nature. 2009;459:726–730. doi: 10.1038/nature08026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fang Y, Cheley S, Bayley H, Yang J. The heptameric prepore of a staphylococcal alpha-hemolysin mutant in lipid bilayers imaged by atomic force microscopy. Biochemistry. 1997;36:9518–9522. doi: 10.1021/bi970600j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smart OS, Coates GM, Sansom MS, Alder GM, Bashford CL. Structure-based prediction of the conductance properties of ion channels. Faraday Discuss. 1998;111:185–199. doi: 10.1039/a806771f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamashita K, Kawai Y, Tanaka Y, Hirano N, Kaneko J, Tomita N, Ohta M, Kamio Y, Yao M, Tanaka I. Crystal structure of the octameric pore of staphylococcal gamma-hemolysin reveals the beta-barrel pore formation mechanism by two components. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:17314–17319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110402108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Comai M, Dalla Serra M, Coraiola M, Werner S, Colin DA, Monteil H, Prevost G, Menestrina G. Protein engineering modulates the transport properties and ion selectivity of the pores formed by staphylococcal gamma-haemolysins in lipid membranes. Mol Microbiol. 2002;44:1251–1267. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sugawara-Tomita N, Tomita T, Kamio Y. Stochastic assembly of two-component staphylococcal gamma-hemolysin into heteroheptameric transmembrane pores with alternate subunit arrangements in ratios of 3:4 and 4:3. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:4747–4756. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.17.4747-4756.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shatursky O, Heuck AP, Shepard LA, Rossjohn J, Parker MW, Johnson AE, Tweten RK. The mechanism of membrane insertion for a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin: a novel paradigm for pore-forming toxins. Cell. 1999;99:293–299. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81660-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hotze EM, Wilson-Kubalek EM, Rossjohn J, Parker MW, Johnson AE, Tweten RK. Arresting pore formation of a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin by disulfide trapping synchronizes the insertion of the transmembrane beta-sheet from a prepore intermediate. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8261–8268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009865200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Czajkowsky DM, Hotze EM, Shao Z, Tweten RK. Vertical collapse of a cytolysin prepore moves its transmembrane beta-hairpins to the membrane. EMBO J. 2004;23:3206–3215. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harris RW, Sims PJ, Tweten RK. Kinetic aspects of the aggregation of Clostridium perfringens theta- toxin on erythrocyte membranes. A fluorescence energy transfer study. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:6936–6941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bhakdi S, Tranum-Jensen J, Sziegoleit A. Mechanism of membrane damage by streptolysin-O. Infect Immun. 1985;47:52–60. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.1.52-60.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Palmer M, Harris R, Freytag C, Kehoe M, Tranum-Jensen J, Bhakdi S. Assembly mechanism of the oligomeric streptolysin O pore: the early membrane lesion is lined by a free edge of the lipid membrane and is extended gradually during oligomerization. EMBO J. 1998;17:1598–1605. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bernheimer AW, Avigad LS, Kim K. Comparison of metridiolysin from the sea anemone with thiol-activated cytolysins from bacteria. Toxicon. 1979;17:69–75. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(79)90257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harris JR, Adrian M, Bhakdi S, Palmer M. Cholesterol-streptolysin O interaction: an EM study of wild-type and mutant streptolysin O. J Struct Biol. 1998;121:343–355. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1998.3989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Harris JR, Lewis RJ, Baik C, Pokrajac L, Billington SJ, Palmer M. Cholesterol microcrystals and cochleate cylinders: attachment of pyolysin oligomers and domain 4. J Struct Biol. 2011;173:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Young JD, Hengartner H, Podack ER, Cohn ZA. Purification and characterization of a cytolytic pore-forming protein from granules of cloned lymphocytes with natural killer activity. Cell. 1986;44:849–859. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Podack ER, Dennert G. Assembly of two types of tubules with putative cytolytic function by cloned natural killer cells. Nature. 1983;302:442–445. doi: 10.1038/302442a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Young LH, Joag SV, Zheng LM, Lee CP, Lee YS, Young JD. Perforin-mediated myocardial damage in acute myocarditis. Lancet. 1990;336:1019–1021. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92486-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bhakdi S, Tranum-Jensen J. On the cause and nature of C9-related heterogeneity of terminal complement complexes generated on target erythrocytes through the action of whole serum. J Immunol. 1984;133:1453–1463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bhakdi S, Tranum-Jensen J. C5b-9 assembly: average binding of one C9 molecule to C5b-8 without poly-C9 formation generates a stable transmembrane pore. J Immunol. 1986;136:2999–3005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zalman LS, Muller-Eberhard HJ. Comparison of channels formed by poly C9, C5b-8 and the membrane attack complex of complement. Mol Immunol. 1990;27:533–537. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(90)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.From C, Granum PE, Hardy SP. Demonstration of a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin in a noninsecticidal Bacillus sphaericus strain and evidence for widespread distribution of the toxin within the species. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;286:85–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Korchev YE, Bashford CL, Pasternak CA. Differential sensitivity of pneumolysin-induced channels to gating by divalent cations. J Membr Biol. 1992;127:195–203. doi: 10.1007/BF00231507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.El-Rachkidy RG, Davies NW, Andrew PW. Pneumolysin generates multiple conductance pores in the membrane of nucleated cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;368:786–792. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bavdek A, Kostanjšek R, Antonini V, Lakey JH, Dalla Serra M, Gilbert RJ, Anderluh G. pH dependence of listeriolysin O aggregation and pore-forming ability. FEBS J. 2011;279:126–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bashford CL, Menestrina G, Henkart PA, Pasternak CA. Cell damage by cytolysin. Spontaneous recovery and reversible inhibition by divalent cations. J Immunol. 1988;141:3965–3974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Podack ER, Young JD, Cohn ZA. Isolation and biochemical and functional characterization of perforin 1 from cytolytic T-cell granules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:8629–8633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Young JD, Nathan CF, Podack ER, Palladino MA, Cohn ZA. Functional channel formation associated with cytotoxic T-cell granules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:150–154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.1.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Young JD, Podack ER, Cohn ZA. Properties of a purified pore-forming protein (perforin 1) isolated from H-2-restricted cytotoxic T cell granules. J Exp Med. 1986;164:144–155. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.1.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pipkin ME, Lieberman J. Delivering the kiss of death: progress on understanding how perforin works. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Birmingham CL, Canadien V, Kaniuk NA, Steinberg BE, Higgins DE, Brumell JH. Listeriolysin O allows Listeria monocytogenes replication in macrophage vacuoles. Nature. 2008;451:350–354. doi: 10.1038/nature06479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shaughnessy LM, Hoppe AD, Christensen KA, Swanson JA. Membrane perforations inhibit lysosome fusion by altering pH and calcium in Listeria monocytogenes vacuoles. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:781–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gekara NO, Westphal K, Ma B, Rohde M, Groebe L, Weiss S. The multiple mechanisms of Ca2+ signalling by listeriolysin O, the cholesterol-dependent cytolysin of Listeria monocytogenes . Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:2008–2021. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Menestrina G, Bashford CL, Pasternak CA. Pore-forming toxins: experiments with S. aureus alpha-toxin, C. perfringens theta-toxin and E. coli haemolysin in lipid bilayers, liposomes and intact cells. Toxicon. 1990;28:477–491. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(90)90292-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Keefe D, Shi L, Feske S, Massol R, Navarro F, Kirchhausen T, Lieberman J. Perforin triggers a plasma membrane-repair response that facilitates CTL induction of apoptosis. Immunity. 2005;23:249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Thiery J, Keefe D, Saffarian S, Martinvalet D, Walch M, Boucrot E, Kirchhausen T, Lieberman J. Perforin activates clathrin- and dynamin-dependent endocytosis, which is required for plasma membrane repair and delivery of granzyme B for granzyme-mediated apoptosis. Blood. 2010;115:1582–1593. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-246116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Thiery J, Keefe D, Boulant S, Boucrot E, Walch M, Martinvalet D, Goping IS, Bleackley RC, Kirchhausen T, Lieberman J. Perforin pores in the endosomal membrane trigger the release of endocytosed granzyme B into the cytosol of target cells. Nature Immunol. 2011;12:770–777. doi: 10.1038/ni.2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Weaver JC. Molecular basis for cell membrane electroporation. Ann New York Acad Sci. 1994;720:141–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb30442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sobko AA, Kotova EA, Antonenko YN, Zakharov SD, Cramer WA. Effect of lipids with different spontaneous curvature on the channel activity of colicin E1: evidence in favor of a toroidal pore. FEBS Lett. 2004;576:205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Anderluh G, Dalla Serra M, Viero G, Guella G, Maček P, Menestrina G. Pore formation by equinatoxin II, a eukaryotic protein toxin, occurs by induction of nonlamellar lipid structures. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45216–45223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Epand RF, Martinou JC, Montessuit S, Epand RM, Yip CM. Direct evidence for membrane pore formation by the apoptotic protein Bax. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;298:744–749. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02544-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Valcarcel CA, Dalla Serra M, Potrich C, Bernhart I, Tejuca M, Martinez D, Pazos F, Lanio ME, Menestrina G. Effects of lipid composition on membrane permeabilization by sticholysin I and II, two cytolysins of the sea anemone Stichodactyla helianthus . Biophys J. 2001;80:2761–2774. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76244-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dalla Serra M, Tejuca Martínez M (2001) Pore-forming toxins. eLS John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0002655.pub2

- 98.Anderluh G, Lakey JH. Proteins membrane binding and pore formation. New York: Springer; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Colibus L, Sonnen AFP, Morris KJ, Siebert CA, Abrusci P, Plitzko J, Hodnik V, Leippe M, Volpi E, Anderluh G, Gilbert RJC. Structures of lysenin reveal a shared evolutionary origin for pore-forming proteins and a novel mode of sphingomyelin recognition. Structure. 2012;20:1498–1507. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Madden JC, Ruiz N, Caparon M. Cytolysin-mediated translocation (CMT): a functional equivalent of type III secretion in Gram-positive bacteria. Cell. 2001;104:143–152. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Praper T, Beseničar MP, Istinič H, Podlesek Z, Metkar SS, Froelich CJ, Anderluh G. Human perforin permeabilizing activity, but not binding to lipid membranes, is affected by pH. Mol Immunol. 2010;47:2492–2504. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Metkar SS, Wang B, Catalan E, Anderluh G, Gilbert RJ, Pardo J, Froelich CJ. Perforin rapidly induces plasma membrane phospholipid flip-flop. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24286. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pinkoski MJ, Hobman M, Heibein JA, Tomaselli K, Li F, Seth P, Froelich CJ, Bleackley RC. Entry and trafficking of granzyme B in target cells during granzyme B-perforin-mediated apoptosis. Blood. 1998;92:1044–1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Froelich CJ, Orth K, Turbov J, Seth P, Gottlieb R, Babior B, Shah GM, Bleackley RC, Dixit VM, Hanna W. New paradigm for lymphocyte granule-mediated cytotoxicity. Target cells bind and internalize granzyme B, but an endosomolytic agent is necessary for cytosolic delivery and subsequent apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29073–29079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.29073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shi L, Mai S, Israels S, Browne K, Trapani JA, Greenberg AH. Granzyme B (GraB) autonomously crosses the cell membrane and perforin initiates apoptosis and GraB nuclear localization. J Exp Med. 1997;185:855–866. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.5.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Praper T, Sonnen AF, Kladnik A, Andrighetti AO, Viero G, Morris KJ, Volpi E, Lunelli L, Dalla Serra M, Froelich CJ, Gilbert RJ, Anderluh G. Perforin activity at membranes leads to invaginations and vesicle formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(52):21016–21021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107473108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Stewart SE, D’Angelo ME, Bird PI. Intercellular communication via the endo-lysosomal system: translocation of granzymes through membrane barriers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1824:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Romer W, Berland L, Chambon V, Gaus K, Windschiegl B, Tenza D, Aly MR, Fraisier V, Florent JC, Perrais D, Lamaze C, Raposo G, Steinem C, Sens P, Bassereau P, Johannes L. Shiga toxin induces tubular membrane invaginations for its uptake into cells. Nature. 2007;450:670–675. doi: 10.1038/nature05996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wollert T, Wunder C, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Hurley JH. Membrane scission by the ESCRT-III complex. Nature. 2009;458:172–177. doi: 10.1038/nature07836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Farsad K, Ringstad N, Takei K, Floyd SR, Rose K, De CP. Generation of high curvature membranes mediated by direct endophilin bilayer interactions. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:193–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bonev BB, Gilbert RJ, Andrew PW, Byron O, Watts A. Structural analysis of the protein/lipid complexes associated with pore formation by the bacterial toxin pneumolysin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:5714–5719. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Miller LH, Baruch DI, Marsh K, Doumbo OK. The pathogenic basis of malaria. Nature. 2002;415:673–679. doi: 10.1038/415673a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ecker A, Pinto SB, Baker KW, Kafatos FC, Sinden RE. Plasmodium berghei: plasmodium perforin-like protein 5 is required for mosquito midgut invasion in Anopheles stephensi . Exp Parasitol. 2007;116:504–508. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ecker A, Bushell ES, Tewari R, Sinden RE. Reverse genetics screen identifies six proteins important for malaria development in the mosquito. Mol Microbiol. 2008;70:209–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06407.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Amino R, Giovannini D, Thiberge S, Gueirard P, Boisson B, Dubremetz JF, Prevost MC, Ishino T, Yuda M, Menard R. Host cell traversal is important for progression of the malaria parasite through the dermis to the liver. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]