Abstract

The cytogenetic hypothesis that common fragile sites (cFSs) are hotspots of cancer breakpoints is increasingly supported by recent data from whole-genome profiles of different cancers. cFSs are components of the normal chromosome structure that are particularly prone to breakage under conditions of replication stress. In recent years, cFSs have become of increasing interest in cancer research, as they not only appear to be frequent targets of genomic alterations in progressive tumors, but also already in precancerous lesions. Despite growing evidence of their importance in disease development, most cFSs have not been investigated at the molecular level and most cFS genes have not been identified. In this review, we summarize the current data on molecularly characterized cFSs, their genetic and epigenetic characteristics, and put emphasis on less-studied cFS genes as potential contributors to cancer development.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00018-014-1723-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Fragile sites, Molecular mapping, Fragilome, cFS genes, NBEA, SPIDR, DPYD

Introduction

Fragile sites have been cytogenetically defined as non-random chromosomal regions exhibiting gaps or breaks on metaphase chromosomes when cells are cultured under conditions of mild replication stress. Based on their frequency in the population, fragile sites have been divided into two major groups: rare fragile sites (rFSs), with a heterozygote frequency of less than 5 % in the human population, and common fragile sites (cFSs), found in chromosomes of all individuals. Instability of rFS alleles can either be attributed to expansions of CGG/CCG trinucleotide repeats or AT-rich minisatellite repeats, whereas cFS loci are part of the normal chromosome structure [1]. Due to their recombinogenic nature, cFSs are frequently affected by genomic aberrations in cancer cells, which may already occur during the premalignant stages [2, 3]. cFSs are thought to represent difficult-to-replicate genomic regions, where fragility results from unreplicated stretches of DNA in mitotic chromosomes [4]. The exact number of human cFSs is still unknown, as 89 cFSs identified in early cytogenetic studies [5] are currently listed in the NCBI genome database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/), whereas recent cytogenetic data indicate about 200 fragile regions in the genome [6]. Unlike cytogenetic screening, molecular cFS mapping has proven to be a very time-consuming process, reflected by the fact that, despite several methodological approaches, only a relatively small proportion of cFSs in the human genome have been identified at the DNA sequence level.

This article provides an overview of the mapping techniques used to characterize cFSs at the molecular level and summarizes published data on the genomic location of cFS sequences. We also analyze the genetic and epigenetic characteristics of molecularly mapped cFSs and highlight less-studied cFS genes that may represent novel targets for cancer research.

Mapping cFS sequences: a laborious challenge

Although non-random chromosomal fragility was first observed when culturing cells under low levels of folic acid to induce breakage at folate-sensitive rFSs, the vast majority of cFSs can be more efficiently activated by low doses of aphidicolin, an inhibitor of DNA polymerases α, δ, and ε [7]. While rFSs can directly be mapped by comparing genomic sequences of carriers with non-carriers through positional cloning, this approach is not suitable for mapping cFSs, since they represent intrinsic chromosomal components of all individuals. Over the past decades, several techniques have been developed and successfully applied to detect cFS sequences (Fig. 1 and Table S1):

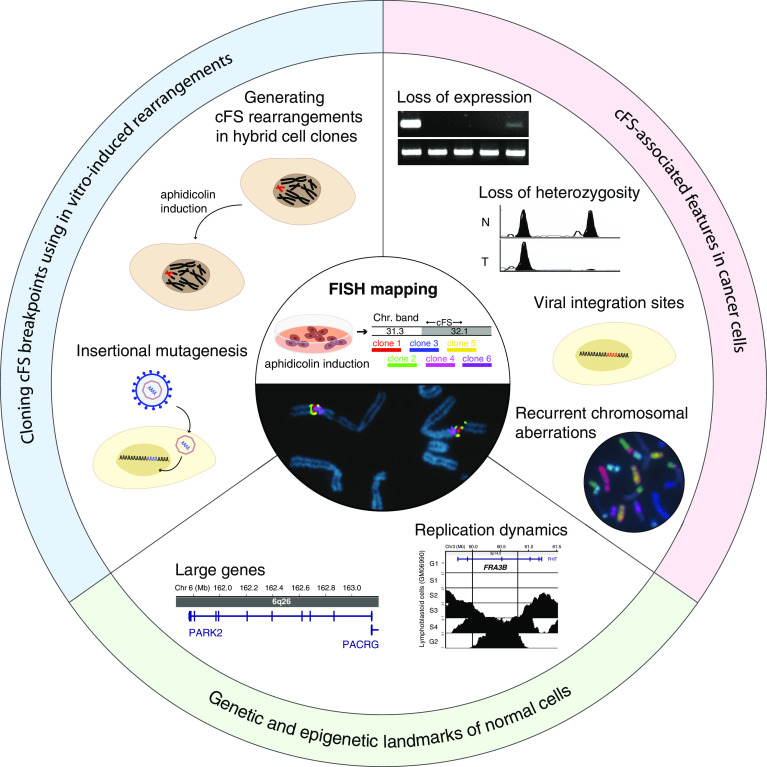

Fig. 1.

Strategies of cFS identification. Cloning cFS breakpoints using in vitro-induced rearrangements (blue segment): following induction of cFS breakage by low concentrations of aphidicolin in somatic cell hybrids containing a single human chromosome (red), cell clones are analyzed for the presence of genetic markers along the human chromosome, enabling the localization of breakpoints within the generated rearrangements. Induced cFS breaks can be targeted using insertional mutagenesis with different DNA vectors, allowing direct cloning of human DNA sequences flanking the vector integration sites. cFS-associated features in cancer cells (red segment): definition of the regions exhibiting recurrent loss of expression (LOE) and loss of heterozygosity (LOH) within chromosomal bands containing cFSs can be useful to narrow down cFS regions. Cloning viral integration sites, mainly of HPV in cervical tumors, has been implemented for pinpointing several cFS sequences. Mapping breakpoints of recurrent genomic alterations, including gross chromosomal deletions, translocations, and amplifications, which can be visualized by FISH painting methods, is also suitable to locate cFSs. Genetic and epigenetic landmarks of normal cells (green segment): two features in normal cells, large genes and a V-shaped replication timing pattern graphically representing Repli-Seq data have been used to search for cFSs. FISH-based mapping as a final step of cFS delineation (center): image demonstrating the principle of cFS mapping using six-color FISH

Cloning cFS breakpoints using in vitro-induced rearrangements

One of the earliest methods designed to identify fragile site sequences involves generating non-random rearrangements in interspecific somatic cell hybrids using replication stress-inducing chemicals [8, 9]. Initially, mapping the resulting aberration breakpoints relied on building physical genomic maps encompassing the sequences of interest, as the first human genome assembly only became available in 2000. The first YAC and cosmid clone-based contig maps have been constructed for FRA3B, the most fragile cFS in human lymphocytes [10–12].

On the basis of the recombinogenic nature of cFSs and evidence that exogenous DNA tends to be integrated at these loci upon replication stress [13], insertional mutagenesis has been employed as an effective tool for cloning cFS sequences. Following the identification of human DNA sequences flanking a pSV2neo marker integrated at FRA3B [14], several other cFS sequences have been successfully isolated by cloning integration sites of pSV2neo [15, 16], as well as MLV retroviral vectors used in gene therapy trials [17].

Alterations in cancer cells as indicators for cFS instability

In various tumor types, loss of heterozygosity (LOH) has been reported to coincide with chromosomal bands containing cFSs. On the basis of this association, chromosomal regions with a high frequency of LOH examined in different cancers have pointed to the genomic sequences spanning FRA7G [18] and FRA9E [19]. Similarly, genes located within cFS regions recurrently exhibiting loss of expression (LOE) in ovarian cancer have revealed the genomic sequences of several cFSs [20].

The hypothesis that cFSs represent preferred targets for viral integration stems from cytogenetic observations indicating that human papilloma virus (HPV) integration sites in cervical tumors coincide with chromosomal bands harboring cFSs [21], which was later confirmed at the molecular level when cloning a human HPV16 integration site within FRA3B [22]. Several HPV16 and HPV18 integration sites in tumor cells have since been cloned, revealing the genomic locations of 18 cFSs [23–25]. Similarly, a simian virus 40 (SV40) integration site cloned in human fibroblasts allowed the identification of FRA7H at 7q32.3 [26].

The correlation between in vitro-induced chromosomal breaks at cFSs and cancer breakpoints has long been recognized and provided the basis for identifying cFS sequences through mapping recurrent genomic alterations in cancer cells. For instance, papillary thyroid carcinoma-specific translocations involving the RET oncogene have been shown to result from recombination events within FRA10C and FRA10G [27]. Moreover, the genomic locations of several cFSs [28–31] have been identified in breakpoint regions flanking duplicated or amplified sequences arising from breakage-fusion-bridge (BFB) cycles in cancer cell lines.

Genetic and epigenetic landmarks facilitate cFS localization

Once the first cFSs had been molecularly mapped, it became apparent that they frequently reside at large genes spanning hundreds of kilobases of genomic DNA. On grounds of this association, chromosomal regions containing very large genes have been examined for chromosomal instability, revealing that as many as one-third of cFSs may be associated with genes spanning over 500 kb [32].

Another approach developed to determine cFS sequences stems from an analysis of replication dynamics along FRA3B [33], where a replication timing pattern reflecting long-traveling forks was observed in lymphocytes and suggested to represent an epigenetic landmark of cFSs. A genome-wide search for similar replication timing patterns using publicly available Repli-Seq data [34] led to the identification of two genomic regions at 3q13.3 and 1p31.1, harboring the most fragile cFSs in fibroblasts [35], suggesting that this approach facilitates the identification of at least the most unstable cFS sequences.

FISH-based mapping as a final step of cFS delineation

Whichever of the above methods is used to localize cFSs at the molecular level, in vitro induction of chromosomal breakage by mild replication stress and subsequent mapping of individual breaks on metaphase chromosomes using FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization) probes remains vital for validating and delineating fragile sequences. As a direct approach, FISH-based mapping was first applied to identify YAC clones spanning FRA3B [10, 11], and has since become the most widely used mapping method, as demonstrated by the majority of molecularly characterized cFSs to date (Table S1). Although mapping cFS sequences remains an extensive and time-consuming procedure requiring hybridization experiments with numerous DNA probes, technical advances in recent years have improved labeling and microscopic methods. Simultaneous hybridization of up to six DNA probes labeled with different fluorescence-conjugated nucleotides, first used to identify FRA13A [36], does not only accelerate molecular mapping, but also ensures the precise definition of contiguous fragile sequences, allowing to distinguish between very close cFSs, such as those at 2p24 [37] or at 8p11-q11 [38].

The genomic landscape of molecularly mapped cFSs

Although cFSs were discovered nearly five decades ago, uncovering the molecular basis of their fragility has remained challenging. Identifying cFS sequences is imperative for understanding their molecular characteristics and role in cellular processes associated with genomic alterations in both normal and cancer cells.

To create an overview of molecularly identified cFS sequences, we reviewed published cFS data representing 72 mapped cFS regions (Table S1), and subdivided them into four categories according to their mapping status:

1. Fine-mapped cFSs comprise all of those sites where fragility has been delineated to a limited genomic sequence using contiguous DNA probes, enabling the identification of the boundaries to non-cFS sequences.

2. Defined cFSs represent sites, at which only the cores of fragility have been defined using contiguous DNA probes, but not the boundaries to non-cFS sequences.

3. Identified cFS regions include chromosomal regions spanning up to several megabases known to contain cFSs, which were identified using widely spaced DNA probes.

4. Pinpointed cFS regions are sites that have been located using a single DNA probe.

Fine-mapped cFSs

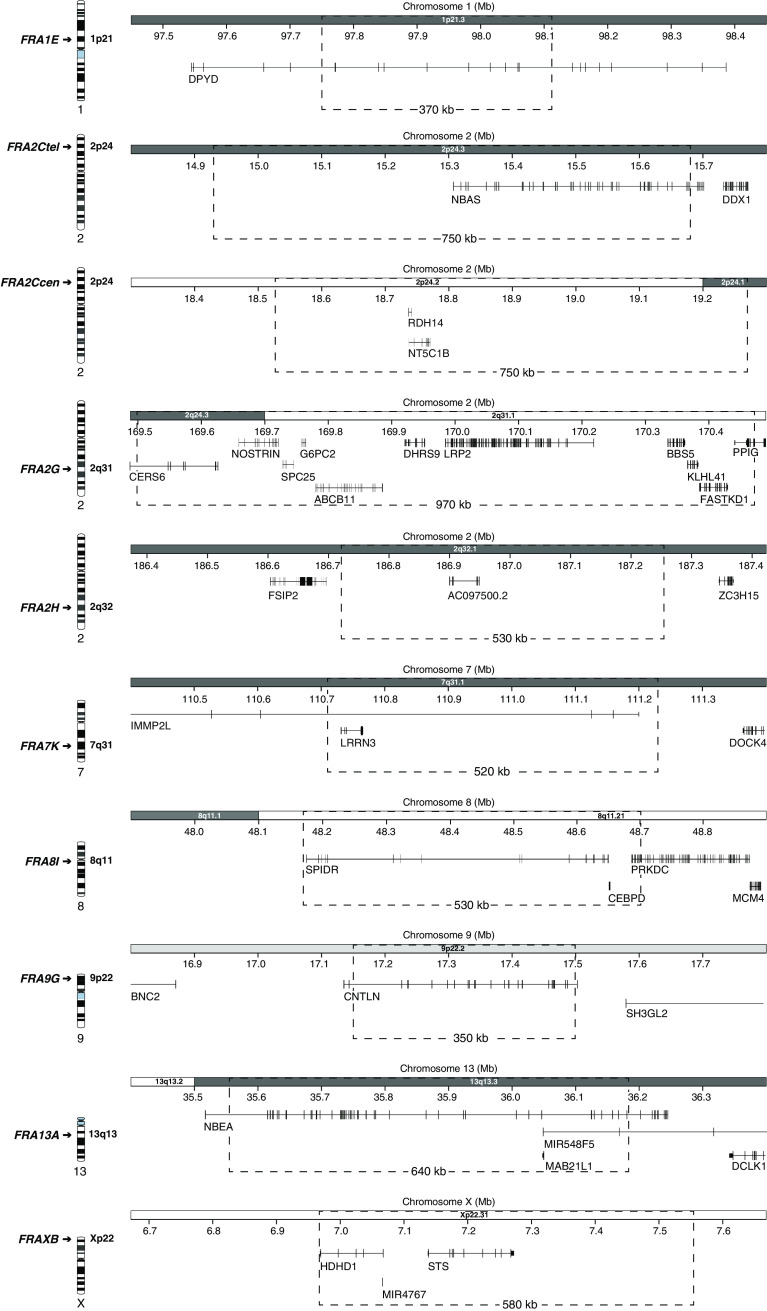

A careful review of the available data reveals that only nine cFSs [36–44] can be considered to be fine-mapped at BAC (~150 kb) resolution level (Fig. 2 and Table 1), having been characterized in either peripheral blood or Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-transformed lymphocytes using FISH with contiguous DNA probes. In all cases, cFS breakage has been induced by low levels of aphidicolin, except for FRA2G, where DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole), a non-intercalating AT-binding compound, was used. Six of these sites (i.e., FRA1E, FRA2C, FRA2G, FRA2H, FRA13A and FRAXB) have been included in the NCBI genome database, while the remaining three, FRA7K, FRA8I and FRA9G have been identified in subsequent studies. Thanks to six-color FISH, FRA2C could be identified as two distinct cFSs (FRA2Ctel and FRA2Ccen) within 2p24 that are indistinguishable at the cytogenetic level [37]. Similarly, molecular mapping of FRA8I [38], a cFS previously assigned to the near-centromeric region at 8p11/q11 [6], revealed that there are in fact two cFSs flanking the chromosome 8 centromere, one on 8p11.21 and another on 8q11.2. The length of fine-mapped cFS sequences ranges between 350 kb (FRA9G) and 970 kb (FRA2G), suggesting a mean length of about 600 kb. According to the integrated cytogenetic map [45] provided by the UCSC [46] and Ensembl [47] genome browsers, six of them are located within G-positive bands (Gpos), while two of them, FRA2Ccen and FRA2G, span junctions between G-positive and G-negative bands, and the remaining two, FRA8I and FRAXB, are situated within G-negative bands (Gneg) (Table 1). These data differ from estimations at the cytogenetic level, predicting cFSs to be predominantly located within G-negative bands [48, 49]. Besides FRA2H, which encompasses a long non-coding RNA gene, all molecularly characterized cFSs contain protein-coding genes. In good agreement with previous observations [32, 50], the majority of these sites map to large genes over 300 kb (Fig. 2 and Table 1), ranging from 319 kb (CERS6 at FRA2G) to 899 kb (IMMP2L at FRA7K).

Fig. 2.

Transcriptional map of fine-mapped cFS regions. Chromosome ideograms on the left indicate the cytogenetic position of each cFS. The genomic coordinates and corresponding chromosome bands are shown on the x-axis; dotted frames indicate the boundaries and size (kb) of each cFS. Displayed genes represent RefSeq genes according to the UCSC genome browser (GRCh37/hg19)

Table 1.

Genetic and epigenetic features of molecularly characterised common fragile sites (~150 kb resolution level)

| cFS | Chr. band | Class of chr. bandb | Extent of genomic region (bp) GRCh37/hg19 | cFS size (kb) | Extent of core region (bp) GRCh37/hg19 | Core size (kb) | GC (%)c | Total repeats (%)c | SINE (%)c | LINE (%)c | Length of AT (≥400 bp) | AT/TA ≥24 units (cFS core) | Flexibility peaks/100 kbd | Replication timinge | Acetylation coverage (%)f | Genes ≥300 kb (cFS core) | Ref.g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRA1E | 1p21.3 | Gpos75 | 1:97,749,961-98,119,925 | 370 | 1:97,817,963-98,003,396 | 190 | 35.6 | 45.9 | 8.3 | 26.0 | – | – | 5.9 | S4-G2 | 0 | DPYD | [39] |

| FRA2Ctel | 2p24.3 | Gpos75 | 2:14,931,569-15,681,340 | 750 | 2:15,072,320-15,456,140 | 380 | 40.7 | 46.4 | 10.5 | 20.3 | 851 | – | 6.3 | S3 | 0 | NBAS | [37] |

| FRA2Ccen | 2p24.2-24.1 | Gneg-Gpos75 | 2:18,526,759-19,270,431 | 750 | 2:18,776,343-19,108,740 | 330 | 38.4 | 45.5 | 9.1 | 25.4 | 1,115 | – | 15.0 | S4-G2 | 0 | – | [37] |

| FRA2G a | 2q24.3-31.1 | Gpos75-Gneg | 2:169,498,510-170,471,920 | 970 | 2:169,948,495-170,471,920 | 520 | 39.5 | 42.8 | 15.3 | 19.9 | 3,176 | – | 2.5 | S2-S3 | 0.3 | – | [40] |

| FRA2H | 2q32.1 | Gpos75 | 2:186,717,985-187,251,137 | 530 | 2:186,781,768-187,125,789 | 340 | 35.2 | 58.3 | 4.9 | 34.4 | – | – | 9.3 | S3-S4 | 0 | – | [41] |

| FRA3B | 3p14.2 | Gneg | N/A | N/A | 3:60,481,958-60,658,590 | 180 | 38.6 | 44.1 | 9.0 | 24.6 | – | – | 4.0 | S4-G2 | 0 | FHIT | [51] |

| FRA7 K | 7q31.1 | Gpos75 | 7:110,712,186-111,230,808 | 520 | 7:110,712,186-110,965,523 | 250 | 35.3 | 35.6 | 7.6 | 19.4 | 675 | – | 4.3 | S4-G2 | 0.6 | IMMP2L | [42] |

| FRA7G | 7q31.2 | Gneg | N/A | N/A | 7:115,848,000-116,140,000 | 290 | 37.8 | 45.0 | 7.9 | 23.6 | – | – | 13.0 | S1-S3 | 6.1 | – | [18] |

| FRA7H | 7q32.3 | Gneg | N/A | N/A | 7:130,502,776-130,663,775 | 160 | 41.8 | 43.6 | 15.5 | 19.4 | – | – | 2.5 | G1-S2 | 32.9 | – | [26] |

| FRA8I | 8q11.21 | Gneg | 8:48,172,122-48,700,294 | 530 | 8:48,292,154-48,700,295 | 410 | 41.4 | 54.1 | 16.5 | 33.0 | – | 30 × AT | 1.0 | G1-S3 | 1.0 | SPIDR | [38] |

| FRA9G | 9p22.2 | Gpos25 | 9:17,148,368-17,497,086 | 350 | 9:17,148,368-17,497,086 | 350 | 36.4 | 60.9 | 8.2 | 40.6 | – | – | 5.4 | S3-S4 | 0 | CNTLN | [43] |

| FRA13A | 13q13.3 | Gpos75 | 13:35,546,088-36,182,897 | 640 | 13:35,819,413-36,012,004 | 190 | 35.0 | 53.7 | 5.0 | 41.0 | – | – | 4.7 | S4-G2 | 0 | NBEA | [36] |

| FRA16D | 16q23.1 | Gpos75 | N/A | N/A | 16:78,420,359-78,731,553 | 310 | 42.7 | 36.1 | 17.4 | 6.5 | – | 36 × AT | 2.4 | S4-G2 | 0 | WWOX | [54] |

| FRAXB | Xp22.31 | Gneg | X:6,968,144-7,547,752 | 580 | X:6,968,144-7,425,274 | 460 | 41.0 | 36.5 | 9.8 | 10.4 | – | – | 9.2 | S4-G2 | 5.7 | – | [44] |

aMode of induction: DAPI

bCytoband classification system [45] based on staining intensity (Gpos100, Gpos75, Gpos50, Gpos25, Gneg); available from UCSC (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) and Ensembl genome browsers (http://www.ensembl.org/)

cInterspersed repeat composition of cFS core sequences identified using RepeatMasker (http://www.repeatmasker.org/) with default settings. Genomic means of SINE and LINE according to class of cytoband [45]: Gpos75 (10.7 ± 3.1 % SINE, 22.9 ± 4.1 % LINE); Gpos25 (18.5 ± 7.7 % SINE, 18.1 ± 5.7 % LINE); Gneg (15.7 ± 6.6 % SINE, 19.2 ± 6.6 % LINE)

dDNA flexibility in cFS core regions estimated using TwistFlex (13.7° helix twist angle, default settings; http://margalit.huji.ac.il/TwistFlex/). Mean DNA flexibility (peaks/100 kb) in G-bands: 3.3 (non-cFSs)/ 5.7 (cFSs); R-bands: 1.8 (non-cFSs)/ 3.4 (cFSs) [68]

eCell cycle phases of replication at cFSs in GM06990 human lymphoblastoid cells (ENCODE/UW Repli-Seq data from UCSC Genome Browser)

fCoverage of H3K9 acetylation domains along cFS core sequences in GM12878 human lymphoblastoid cells; ENCODE ChIP-seq data (Broad Histone) from UCSC Genome Browser. Estimated acetylation level of human genome: 11.88 % [89]

gReferences for cFS mapping data

Defined cFSs

Of the first five molecularly characterized cFSs, including the two best-studied cFSs, FRA3B and FRA16D, only the core regions of fragility have been fine-mapped (Table 1, Table S1). In case of FRA3B, examining aphidicolin-induced breaks in somatic cell hybrids and in metaphase chromosomes from peripheral blood lymphocytes using FISH, the core of instability has been delineated to a region of over 500 kb encompassing introns four and five of the FHIT gene [10–12, 14, 51]. Using similar approaches, the core sequences of FRA7G [52], FRA7H [26] and FRA16D [53, 54] have been determined, as well as a genomic region at FRA6F exhibiting an almost consistent level of fragility extending over about 1 Mb [55]. Efforts have been made to identify the entire sequences of FRA3B, FRA7G and FRA16D [56–58], however, using probes spaced at hundreds of kilobases, these analyses have not defined the boundaries to non-cFSs.

Identified cFS regions

The majority of cFSs (33 sites) have been mapped using BAC probes spaced at several megabases across large genomic distances (Table S1) in different cell types, including lymphocytes [15, 16, 19, 20, 25, 28, 30, 59–63], fetal lung fibroblasts [35, 50], as well as colorectal and breast epithelial cells [50, 64]. With a mean size of over 5.3 Mb, ranging from 1.33 Mb (FRAXL) to 14.65 Mb (FRA5E) [50], fragile regions mapped this way are about nine times larger than the mean of fine-mapped cFSs. It is thus likely that recurrent fragility along genomic regions of several megabases reflects the presence of additional unidentified cFSs. For instance, the FRA5E region reported to span 14.65 Mb on 5p15.1–5p13.3 [50] actually appears to encompass three cFSs: FRA5H (5p15), FRA5E (5p14) and FRA5A (5p13), as revealed by classical cytogenetic analysis [6]. Similarly, FRA1R at 1q41 and FRA1H at 1q42 are clearly distinguishable as a region of fragility within a G-positive and another within a G-negative band, but have been reported as a single cFS, FRA1H, spanning 10.6 Mb of genomic DNA [60]. Therefore, although molecular probes have been applied to locate these cFSs, the mapping accuracy is comparable or at times even inferior to high-resolution G-banding analyses, providing evidence for cFSs within the analyzed chromosomal regions, but not specifying the extent of fragile sequences.

Pinpointed cFS regions

An additional set of genomic regions has been investigated for cFS fragility in aphidicolin-treated lymphocytes using a single DNA probe (Table S1) to mark HPV16 and HPV18 integration sites in cervical carcinomas [23–25], large genes [32, 65–67] or cancer alterations [27, 29, 68, 69]. As a result, breakpoint-spanning probes have indicated the genomic positions of FRA1B, FRA6C, FRA10G, FRA16C and FRA17B. However, the use of only a single DNA probe has been insufficient to confirm the presence of cFSs at the majority of examined regions.

Genomic, epigenetic or transcriptional peculiarities: which factors determine cFS fragility?

cFS fragility has been extensively studied, highlighting several common characteristics. Different models have been proposed emphasizing the role of particular genomic, epigenetic and transcriptional characteristics in cFS fragility (see B. Kerem’s and M. Debatisse’s chapter in this issue). To estimate how common these features occur within cFSs, we analyzed the cFS core sequences harboring more than 60 % of breaks within fine-mapped and defined cFSs (Table 1). The length of the 14 investigated core regions (4.530 kb overall) ranges between 161 kb (FRA7H) and 523 kb (FRA2G).

The DNA sequence as a primary cause of cFS instability

The hypothesis that the DNA sequence itself is a primary cause of cFS instability is supported by experimental data suggesting that human cFS sequences remain fragile at ectopic locations when exposed to replication stress, as demonstrated by stably transfecting BAC clones corresponding to cFS sequences into non-cFS regions [70]. Likewise, yeast cells containing human cFS sequences on extra chromosomes have been shown to exhibit increased fragility following aphidicolin induction [71]. Several genomic features, including G-band assignments, GC content, enrichments in certain repeat classes or sequence motifs as well as DNA flexibility have been associated with cFSs. The majority of analyzed cFS core sequences (ten out of 14) have a lower GC content than the genome-wide mean (41 %) [72], ranging between 34.97 % (FRA13A) and 40.7 % (FRA2Ctel), and can thus be considered AT-rich (Table 1). Although cFS fragility has been associated with a high density of specific repetitive motifs, the total mean content of interspersed repeat elements (46.5 %) resembles the genomic mean of approximately 45 %. Moreover, in contrast to in silico predictions at cytoband resolution level [73], the analyzed core regions are SINE/Alu poor with mean of 10.4 % (genomic mean: 13.1 %), except for FRA16D, showing an enrichment in SINEs (17.39 %). Most notable, however, is the mean LINE content (23.97 %), which is higher than the genomic mean (20.42 %), and especially elevated in the FRA2H, FRA8I, FRA9G and FRA13A core regions (ranging between 32.07 and 40.75 %), indicating abundance in LINEs rather than in SINEs. Evidence that LINEs are directly involved in generating genomic alterations in cancer cells has been reported for FRA2H [41] and FRA3B [74]. Concerning the genetic nature of cFS instability, it is thought that cFS sequences are not uniformly unstable, but contain a high density of sequence motifs that are particularly prone to forming unusual DNA structures [75]. In the presence of replication stress, several DNA motifs, including LINE and LTR elements [76], AT-rich sequences [68], AT/TA and A/T microsatellites [77], potentially promote secondary structure formation, which may result in replication fork stalling or collapse, and ultimately in incomplete DNA replication and breakage. For instance, long stretches of perfect AT repeats (>24 units) have been suggested to cause FRA16D fragility [77, 78], however, our analysis of the set of molecularly mapped cFSs indicates that this feature is not common, since apart from FRA16D only FRA8I appears to harbor such a sequence motif.

A greater density of DNA flexibility peaks at cFSs relative to non-cFSs, measured by variations in the twist angle between adjacent base pairs, has been proposed as a shared feature of cFSs [26]. Although several cFSs have been confirmed to be enriched in potentially highly flexible sequences [4], this does not apply to all cFSs [79]. As the mean flexibility of genomic sequences can be estimated as four flexibility islands/100 kb [68], four out of 14 (28.6 %) cFS cores (i.e., FRA2Ccen, FRA2H, FRA7G, and FRAXB) are more than 2.5-fold enriched in flexibility peaks. Overall, about half of the analyzed cFS core sequences are characterized by increased DNA flexibility, while some even display low flexibility levels.

Replication timing as a primary cause of cFS instability

It is widely accepted in the literature that late completion of DNA replication is a basic feature of cFSs and primary cause of their instability (see A. Franchitto’s chapter in this issue). The two most active cFSs in lymphocytes, FRA3B and FRA16D, are constitutively late-replicating genomic regions, where induced replication stress (e.g., aphidicolin treatment) results in further delay and failure to complete replication prior to entering mitosis [80–82]. A comparison of ENCODE Repli-Seq profiles of GM06990 cells [34] along genomic regions containing cFSs shows that 57 % of cFS regions (eight out of 14), are constitutively late replicated with replication being initiated during late S-phase and extending into G2 (Table 1 and Fig. S1). However, replication does not appear to be initiated very late at all cFSs, as demonstrated by Repli-Seq profiles along the remaining six cFSs, including the previously characterized FRA7G [58], FRA7H [83] and FRA2G [40] cFSs. Although such regions are early-to-mid replicated under normal growth conditions, they are much slower in completing replication upon aphidicolin-induced stress than non-cFS regions, which, in turn, may cause unreplicated DNA sequences to accumulate at these loci. In addition, regions of transition between early and late replicating domains have been associated with susceptibility to genetic damage at some fragile sites, including the FRA10B rFS [84] and the FRA6E cFS [85]. However, Repli-Seq profiles of the 14 analyzed cFSs show that only FRA8I encompasses an early/late replication transition zone (Fig. S1), indicating that this is not a common characteristic.

Density and activation of replication origins modify cFS stability

Recently, a molecular cause for the specific sensitivity of cFSs to replication stress has been surveyed by analyses of replication dynamics at three cFS regions, FRA3B, FRA6E, and FRA16C [33, 85–87]. Measuring fork rates along with mapping replication origins and arrested forks using DNA combing or nascent strand mapping techniques, two different mechanisms have been proposed that link replication parameters with cFS breakage. First, Ozeri-Galai and colleagues showed that slow fork progression and frequent stalling at long AT-rich sequences (>400 bp) are attributes of FRA16C, even under normal growth conditions, which are further increased in response to replication stress [87]. Consequently, the inability to compensate for such perturbed fork movement by activating additional origins was suggested to account for replication delay and fragility along cFSs. In line with this model, single long AT-rich sequences ranging between 675 bp in FRA7K and 3,176 bp in FRA2G (Table 1) are located within the core regions of four cFSs (28.6 %), however, whether replication dynamics at these loci resemble those at FRA16C remains to be investigated. A second model arises from the natural paucity of initiation events identified within a 700 kb region encompassing FRA3B, where replication forks travel long distances from flanking regions before merging in late S-phase or G2-phase [33]. A combination of late replication completion and paucity of initiation events has been suggested as a key feature of cFSs determined by cell-type-specific replication programmes. Although V-shaped Repli-Seq profiles, representing late-replicating regions flanked by early-to-late replicating transition zones [34], have been experimentally confirmed and led to the identification of two cFSs in fibroblasts [35], this type of replication pattern does not appear to be common, as of the 14 molecularly mapped cFSs, only FRA3B, FRA16D and FRA2Ccen exhibit such a profile in lymphoblastoid cells (Fig. S1).

Histone hypoacetylation contributes to cFS instability

A link between epigenetic marks and cFS fragility has been demonstrated by comparing chromatin modification patterns in six human cFSs with those in flanking non-cFS regions [88]. Using a ChIP-on-chip assay, histone acetylation levels at cFSs were found to be significantly lower than the estimated acetylation level of the human genome (11.88 %) [89], implying a more compact chromatin structure than in non-cFS regions. Moreover, this study revealed that treatment with deacetylase inhibitors reduces cFS breakage, suggesting that chromatin hypoacetylation contributes to high sensitivity to DNA replication stress. Consistent with this observation, a computational analysis of ENCODE ChIP-Seq profiles shows a lack of or reduction in histone acetylation levels within the 14 cFS cores (Table 1 and Fig. S2), except for FRA7H, which has previously been noted to be hyperacetylated [88]. Overall, histone hypoacetylation appears to be a characteristic epigenetic pattern of the majority of cFSs, possibly interfering with replication dynamics and/or DNA repair processes, thus driving cFS instability under replication stress.

Concomitant transcription and replication of large genes as a source of cFS fragility

cFSs have long been associated with large genes in the human genome [32], which has recently been further confirmed by genome-wide cFS profiling in different cell types [50], although the biological basis of this association remains unclear. Among the molecularly mapped core regions, 57 % (eight out of 14) partially encompass or lie within genes larger than 300 kb (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Active transcription and replication at three of these genes (>800 kb), FHIT, IMMP2L, and WWOX, have been shown to spatially and temporally overlap, causing the transcription and replication machineries to collide and generate DNA breaks [90]. Whether this mechanism may also cause fragility at DPYD (843 kb) and NBEA (730 kb), two other late-replicating cFS genes of similar size, remains to be investigated. Contradicting this hypothesis, a study investigating several large cFS genes revealed that there was no correlation between transcriptional activity and frequency of breakage [50], indicating that this model may only apply to a rather limited number of cFS genes.

Overall, multiple (epi)genetic features and transcriptional peculiarities have been suggested to underlie the unstable nature of cFS loci. However, all of these characteristics are generally abundant in the genome and do not seem obligatory for cFS fragility. Based on current knowledge, it is thus plausible to assume that cFSs are a heterogeneous group of genomic loci, where fragility is determined by varying combinations of different DNA sequence and epigenetic features, rather than by any particular signature shared by all cFS loci.

cFS genes and cancer: finding contributors to tumor development

Early cytogenetic observations implying that chromosomal bands harboring cFSs are hotspots of cancer breakpoints [48, 91] have in recent years been supported by whole-genome array CGH profiles of different cancer types [92, 93]. Without a comprehensive fragilome map of the human genome, we can only estimate to what extent cancer breakpoints fall within cFSs. Despite judging from a relatively small portion of molecularly mapped cFSs, there is evidently a link between recurrent cancer alterations and cFSs [94]. Moreover, damage at cFSs has been shown to occur among the earliest genetic events in oncogenesis, since already detectable in precancerous lesions [2, 3]. Both of these facts have put cFSs in context of clinical oncology research, raising the question of which cFS genes could drive or contribute to tumor development. In many malignancies, the genomic integrity of cFS genes is compromised through various types of chromosomal rearrangements, leading either to copy number alterations (i.e., deletions, duplications and amplifications) detectable by array CGH (Fig. 3a–c), or to juxtaposition of chromosomal segments (i.e., inversions, insertions and translocations), which may be visualized using FISH painting methods (Fig. 3d). However, a high frequency of genomic alterations alone is insufficient to determine whether affected genes contribute to tumorigenesis. For instance, MACROD2, a putative cFS gene, has been shown to be exclusively affected by intronic deletions that do not alter gene expression, despite exhibiting one of the highest rates of focal deletions (<10 Mb) in cancer genomes [64]. Hence, cFS genes need to be studied individually to clarify whether or not they contribute to tumor development. Prominent examples indicating that inactivation of cFS genes may provide a selective growth advantage to cancer cells include FHIT (FRA3B), WWOX (FRA16D) and PARK2 (FRA6E), which encompass the most frequently deleted loci in various tumor genomes and have been shown to act as tumor suppressor genes [95–97]. Furthermore, testin (TES) [98] and caveolin-2 (CAV2) [99], two genes located within the core region of FRA7G, have been shown to elicit tumor suppressor activity. Recently, three other molecularly confirmed cFS genes, NBEA, SPIDR and DPYD, have emerged as potential cancer susceptibility genes undergoing further investigation.

Fig. 3.

The main types of recurrent cFS rearrangements in cancer. a Hemizygous deletions at cFSs. Loss of genetic material at FRA2H in HDC-133 nm colorectal cancer cells revealed by array CGH analysis (left) and validated by FISH (right), showing that genomic loss at FRA2H results from a hemizygous deletion (del) in one of the chromosome 2 homologues, as demonstrated by the absence of the red hybridization signal. b Duplications at cFSs. Copy number gain at FRA16D detected by array CGH in the NGP neuroblastoma cell line (left) originating from an intrachromosomal duplication in one of the chromosome 16 homologues displaying a double pink signal (dup) in metaphase spreads (right). c Amplifications at cFSs. FRA2C sequences partially overlap with MYCN amplicons in neuroblastoma cell lines on array CGH plots (left), corresponding to the high-level amplifications detected by FISH (left): homogeneously staining region (HSR) on a derivative chromosome in LA–N-2 cells, and extrachromosomal double minutes (DMs) in LA–N-5 metaphase spreads. d Translocations at cFSs. Multicolor FISH (mFISH) analysis revealing a derivative chromosome identified as a t(7;8;11) translocation in Caco-2 colorectal cancer cells (left). One of the translocation breakpoints in chromosome 8 maps within FRA8I, as confirmed by the absence of the red hybridization signal on a derivative chromosome using two FISH probes (right). Dotted frames indicate cFS boundaries; genomic coordinates are shown on the x-axis, the log2 ratio of test to reference DNA on the y-axis. Arrowheads on array plots indicate the genomic position of the BAC probes used for FISH validation. Arrows highlight derivative chromosomes with cFS aberrations, n marks apparently normal copies of chromosome homologues

NBEA, a cancer candidate gene

The neurobeachin (NBEA) gene at FRA13A encodes a multidomain A-kinase anchor protein (ACAP) that has been shown to play a major role in the regulation of synaptic transmission [100]. In concordance with its role in neuronal cells, NBEA has been recognized as a candidate gene for idiopathic autism [101, 102]. While it remains unclear whether NBEA aberrations may drive cancer development, consistently decreased NBEA RNA expression has been observed in endometrial [103] and oropharyngeal cancers [104]. Moreover, NBEA has been identified as a target of recurrent interstitial deletions resulting in reduced expression in multiple myelomas, and has thus been suggested as a candidate tumor suppressor gene for this tumor type [105]. Besides reduced expression of normal transcripts, recurrent translocation events resulting in a highly expressed PVT1-NBEA chimeric gene have been reported in multiple myeloma [106].

SPIDR, a new player in maintenance of genomic integrity

The SPIDR (scaffolding protein involved in DNA repair) gene within FRA8I encodes a newly identified protein, which serves as scaffolding protein for BLM and RAD51, two key DNA-processing enzymes in the homologous DNA recombination pathway, mediating their assembly at DNA lesions [107]. This function implies that SPIDR is an important player in DNA damage repair and maintenance of chromosomal integrity, whose impaired activity may contribute to genomic instability in cancer cells. Supporting this assumption, focal recombination events disrupting the genomic integrity of SPIDR (KIAA0146) have been identified in a subset of colorectal cancer cell lines [38]. Additionally, a reanalysis of published data [108] revealed that SPIDR is a translocation partner of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene (IGH) in recurrent t(8;14)(q11;q32) translocations in a subtype of B cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia, suggesting involvement in the pathogenesis of hematological malignancies.

DPYD, a predictor of patient risk and therapy outcome

The dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPYD) gene at FRA1E encodes DPD, a pyrimidine catabolic enzyme, which catalyses the initial and rate-limiting step of a metabolic pathway involved in the degradation of uracil and thymine. Although genomic alterations of DPYD are not rare in cancer cells, as recently demonstrated by alterations of DPYD coding sequences in more than 40 % of investigated triple-negative breast cancer specimens [109], their contribution to cancer development is unknown. In pharmacogenomics, the DPYD status in both normal and cancer cells is an important factor, as DPD is responsible for the degradation of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), an antineoplastic drug commonly used in cancer therapy. While germline mutations or large intragenic DPYD rearrangements associated with DPD deficiency carry an increased risk of 5-FU toxicity in cancer patients [110], DPYD rearrangements accompanied by low DPD expression in tumor cells have been associated with a beneficial effect of 5-FU-based chemotherapy and better patient outcome, probably due to slower degradation of the administered drug [109, 111]. Thus, the intrinsic genomic instability of DPYD appears to be a useful molecular marker for assessing the risk of 5-FU toxicity and predicting clinical outcome.

cFS instability in cancer may not only cause critical aberrations within cFS genes, but may also trigger amplifications of neighboring proto-oncogenes via two different mechanisms: for instance, intrachromosomal MET amplification via BFB cycles has been shown to frequently originate from breaks at FRA7G [58, 112], while extrachromosomal MYCN amplifications have been demonstrated to arise from extra replication rounds at the flanking sequences of FRA2Ctel and FRA2Ccen [37]. Another likely scenario to be investigated is that breakage at distant cFSs may also set the boundaries of large hemizygous genomic areas encompassing tumor suppressor genes, and therefore represent one of the ‘hits’ predicted by Knudson’s two-hit hypothesis of tumorigenesis.

Conclusions

Since fragile sites were first described as a cytogenetic peculiarity in an individual nearly 50 years ago [113], the study of this chromosomal phenomenon has evolved into a broad research field investigating the cellular mechanisms of genomic instability in both normal and cancer cells. In the past years, major advances have been made in uncovering the molecular pathways maintaining cFS stability and understanding the function and impact of FHIT and WWOX, the most fragile genes in tumorigenesis. However, the major weakness of fragile site research appears to be our limited knowledge about the location and extent of genomic sequences encompassing cFSs. Hence, up to date, only approximately 5 % of cFSs have been characterized at the molecular level, emphasizing the urgent need for developing new genome-wide screening approaches to uncover the full repertoire of cFSs in the human genome. A fragilome map will provide a platform for investigating the molecular basis of cFS instability and in turn enable the identification of high-risk genes that may represent suitable therapeutic targets in clinical trials.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Helmholtz-Russia Joint Research Groups (HRJRG-006), the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung Neuroblastom Genom Forschungs Netzwerk (BMBF NGFNPlus #01GS0896), and the European Union (ASSET #259348, FP7).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lukusa T, Fryns JP. Human chromosome fragility. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1779(1):3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorgoulis VG, Vassiliou LV, Karakaidos P, Zacharatos P, Kotsinas A, Liloglou T, Venere M, Ditullio RA, Jr, Kastrinakis NG, Levy B, Kletsas D, Yoneta A, Herlyn M, Kittas C, Halazonetis TD. Activation of the DNA damage checkpoint and genomic instability in human precancerous lesions. Nature. 2005;434(7035):907–913. doi: 10.1038/nature03485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halazonetis TD, Gorgoulis VG, Bartek J. An oncogene-induced DNA damage model for cancer development. Science. 2008;319(5868):1352–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.1140735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durkin SG, Glover TW. Chromosome fragile sites. Annu Rev Genet. 2007;41:169–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.042007.165900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger R, Bloomfield CD, Sutherland GR. Report of the committee on chromosome rearrangements in neoplasia and on fragile sites. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1985;40(1–4):490–535. doi: 10.1159/000132181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mrasek K, Schoder C, Teichmann AC, Behr K, Franze B, Wilhelm K, Blaurock N, Claussen U, Liehr T, Weise A. Global screening and extended nomenclature for 230 aphidicolin-inducible fragile sites, including 61 yet unreported ones. Int J Oncol. 2010;36(4):929–940. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glover TW, Berger C, Coyle J, Echo B. DNA polymerase alpha inhibition by aphidicolin induces gaps and breaks at common fragile sites in human chromosomes. Hum Genet. 1984;67(2):136–142. doi: 10.1007/BF00272988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glover TW, Stein CK. Chromosome breakage and recombination at fragile sites. Am J Hum Genet. 1988;43(3):265–273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang ND, Testa JR, Smith DI. Determination of the specificity of aphidicolin-induced breakage of the human 3p14.2 fragile site. Genomics. 1993;17(2):341–347. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilke CM, Guo SW, Hall BK, Boldog F, Gemmill RM, Chandrasekharappa SC, Barcroft CL, Drabkin HA, Glover TW. Multicolor FISH mapping of YAC clones in 3p14 and identification of a YAC spanning both FRA3B and the t(3;8) associated with hereditary renal cell carcinoma. Genomics. 1994;22(2):319–326. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boldog FL, Waggoner B, Glover TW, Chumakov I, Le Paslier D, Cohen D, Gemmill RM, Drabkin HA. Integrated YAC contig containing the 3p14.2 hereditary renal carcinoma 3;8 translocation breakpoint and the fragile site FRA3B. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1994;11(4):216–221. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870110403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paradee W, Wilke CM, Wang L, Shridhar R, Mullins CM, Hoge A, Glover TW, Smith DI. A 350-kb cosmid contig in 3p14.2 that crosses the t(3;8) hereditary renal cell carcinoma translocation breakpoint and 17 aphidicolin-induced FRA3B breakpoints. Genomics. 1996;35(1):87–93. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rassool FV, McKeithan TW, Neilly ME, van Melle E, Espinosa R, 3rd, Le Beau MM. Preferential integration of marker DNA into the chromosomal fragile site at 3p14: an approach to cloning fragile sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(15):6657–6661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rassool FV, Le Beau MM, Shen ML, Neilly ME, Espinosa R, 3rd, Ong ST, Boldog F, Drabkin H, McCarroll R, McKeithan TW. Direct cloning of DNA sequences from the common fragile site region at chromosome band 3p14.2. Genomics. 1996;35(1):109–117. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fechter A, Buettel I, Kuehnel E, Savelyeva L, Schwab M. Common fragile site FRA11G and rare fragile site FRA11B at 11q23.3 encompass distinct genomic regions. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46(1):98–106. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fechter A, Buettel I, Kuehnel E, Schwab M, Savelyeva L. Cloning of genetically tagged chromosome break sequences reveals new fragile sites at 6p21 and 13q22. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(11):2359–2367. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bester AC, Schwartz M, Schmidt M, Garrigue A, Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Cavazzana-Calvo M, Ben-Porat N, Von Kalle C, Fischer A, Kerem B. Fragile sites are preferential targets for integrations of MLV vectors in gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2006;13(13):1057–1059. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang H, Qian J, Proffit J, Wilber K, Jenkins R, Smith DI. FRA7G extends over a broad region: coincidence of human endogenous retroviral sequences (HERV-H) and small polydispersed circular DNAs (spcDNA) and fragile sites. Oncogene. 1998;16(18):2311–2319. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callahan G, Denison SR, Phillips LA, Shridhar V, Smith DI. Characterization of the common fragile site FRA9E and its potential role in ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 2003;22(4):590–601. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denison SR, Becker NA, Ferber MJ, Phillips LA, Kalli KR, Lee J, Lillie J, Smith DI, Shridhar V. Transcriptional profiling reveals that several common fragile-site genes are downregulated in ovarian cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;34(4):406–415. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Popescu NC, DiPaolo JA. Preferential sites for viral integration on mammalian genome. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1989;42(2):157–171. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(89)90084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilke CM, Hall BK, Hoge A, Paradee W, Smith DI, Glover TW. FRA3B extends over a broad region and contains a spontaneous HPV16 integration site: direct evidence for the coincidence of viral integration sites and fragile sites. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5(2):187–195. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thorland EC, Myers SL, Persing DH, Sarkar G, McGovern RM, Gostout BS, Smith DI. Human papillomavirus type 16 integrations in cervical tumors frequently occur in common fragile sites. Cancer Res. 2000;60(21):5916–5921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorland EC, Myers SL, Gostout BS, Smith DI. Common fragile sites are preferential targets for HPV16 integrations in cervical tumors. Oncogene. 2003;22(8):1225–1237. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferber MJ, Thorland EC, Brink AA, Rapp AK, Phillips LA, McGovern R, Gostout BS, Cheung TH, Chung TK, Fu WY, Smith DI. Preferential integration of human papillomavirus type 18 near the c-myc locus in cervical carcinoma. Oncogene. 2003;22(46):7233–7242. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mishmar D, Rahat A, Scherer SW, Nyakatura G, Hinzmann B, Kohwi Y, Mandel-Gutfroind Y, Lee JR, Drescher B, Sas DE, Margalit H, Platzer M, Weiss A, Tsui LC, Rosenthal A, Kerem B. Molecular characterization of a common fragile site (FRA7H) on human chromosome 7 by the cloning of a simian virus 40 integration site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(14):8141–8146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gandhi M, Dillon LW, Pramanik S, Nikiforov YE, Wang YH. DNA breaks at fragile sites generate oncogenic RET/PTC rearrangements in human thyroid cells. Oncogene. 2010;29(15):2272–2280. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ciullo M, Debily MA, Rozier L, Autiero M, Billault A, Mayau V, El Marhomy S, Guardiola J, Bernheim A, Coullin P, Piatier-Tonneau D, Debatisse M. Initiation of the breakage-fusion-bridge mechanism through common fragile site activation in human breast cancer cells: the model of PIP gene duplication from a break at FRA7I. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11(23):2887–2894. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.23.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zimonjic DB, Durkin ME, Keck-Waggoner CL, Park SW, Thorgeirsson SS, Popescu NC. SMAD5 gene expression, rearrangements, copy number, and amplification at fragile site FRA5C in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Neoplasia. 2003;5(5):390–396. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(03)80041-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reshmi SC, Huang X, Schoppy DW, Black RC, Saunders WS, Smith DI, Gollin SM. Relationship between FRA11F and 11q13 gene amplification in oral cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46(2):143–154. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bester AC, Kafri M, Maoz K, Kerem B. Infection with retroviral vectors leads to perturbed DNA replication increasing vector integrations into fragile sites. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2189. doi: 10.1038/srep02189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith DI, Zhu Y, McAvoy S, Kuhn R. Common fragile sites, extremely large genes, neural development and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2006;232(1):48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Letessier A, Millot GA, Koundrioukoff S, Lachages AM, Vogt N, Hansen RS, Malfoy B, Brison O, Debatisse M. Cell-type-specific replication initiation programs set fragility of the FRA3B fragile site. Nature. 2011;470(7332):120–123. doi: 10.1038/nature09745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hansen RS, Thomas S, Sandstrom R, Canfield TK, Thurman RE, Weaver M, Dorschner MO, Gartler SM, Stamatoyannopoulos JA. Sequencing newly replicated DNA reveals widespread plasticity in human replication timing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(1):139–144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912402107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Tallec B, Dutrillaux B, Lachages AM, Millot GA, Brison O, Debatisse M. Molecular profiling of common fragile sites in human fibroblasts. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18(12):1421–1423. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Savelyeva L, Sagulenko E, Schmitt JG, Schwab M. The neurobeachin gene spans the common fragile site FRA13A. Hum Genet. 2006;118(5):551–558. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-0083-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blumrich A, Zapatka M, Brueckner LM, Zheglo D, Schwab M, Savelyeva L. The FRA2C common fragile site maps to the borders of MYCN amplicons in neuroblastoma and is associated with gross chromosomal rearrangements in different cancers. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(8):1488–1501. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brueckner LM, Hess EM, Schwab M, Savelyeva L. Instability at the FRA8I common fragile site disrupts the genomic integrity of the KIAA0146, CEBPD and PRKDC genes in colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2013;336(1):85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hormozian F, Schmitt JG, Sagulenko E, Schwab M, Savelyeva L. FRA1E common fragile site breaks map within a 370kilobase pair region and disrupt the dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene (DPYD) Cancer Lett. 2007;246(1–2):82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Limongi MZ, Pelliccia F, Rocchi A. Characterization of the human common fragile site FRA2G. Genomics. 2003;81(2):93–97. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(03)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brueckner LM, Sagulenko E, Hess EM, Zheglo D, Blumrich A, Schwab M, Savelyeva L. Genomic rearrangements at the FRA2H common fragile site frequently involve non-homologous recombination events across LTR and L1(LINE) repeats. Human genetics. 2012;131(8):1345–1359. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Helmrich A, Stout-Weider K, Matthaei A, Hermann K, Heiden T, Schrock E. Identification of the human/mouse syntenic common fragile site FRA7K/Fra12C1–relation of FRA7K and other human common fragile sites on chromosome 7 to evolutionary breakpoints. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(1):48–54. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sawinska M, Schmitt JG, Sagulenko E, Westermann F, Schwab M, Savelyeva L. Novel aphidicolin-inducible common fragile site FRA9G maps to 9p22.2, within the C9orf39 gene. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46(11):991–999. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arlt MF, Miller DE, Beer DG, Glover TW. Molecular characterization of FRAXB and comparative common fragile site instability in cancer cells. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;33(1):82–92. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Furey TS, Haussler D. Integration of the cytogenetic map with the draft human genome sequence. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(9):1037–1044. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, Haussler D. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12(6):996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flicek P, Amode MR, Barrell D, Beal K, Billis K, Brent S, Carvalho-Silva D, Clapham P, Coates G, Fitzgerald S, Gil L, Giron CG, Gordon L, Hourlier T, Hunt S, Johnson N, Juettemann T, Kahari AK, Keenan S, Kulesha E, Martin FJ, Maurel T, McLaren WM, Murphy DN, Nag R, Overduin B, Pignatelli M, Pritchard B, Pritchard E, Riat HS, Ruffier M, Sheppard D, Taylor K, Thormann A, Trevanion SJ, Vullo A, Wilder SP, Wilson M, Zadissa A, Aken BL, Birney E, Cunningham F, Harrow J, Herrero J, Hubbard TJ, Kinsella R, Muffato M, Parker A, Spudich G, Yates A, Zerbino DR, Searle SM. Ensembl 2014. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D749–D755. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hecht F. Fragile sites, cancer chromosome breakpoints, and oncogenes all cluster in light G bands. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1988;31(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(88)90005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fungtammasan A, Walsh E, Chiaromonte F, Eckert KA, Makova KD. A genome-wide analysis of common fragile sites: what features determine chromosomal instability in the human genome? Genome Res. 2012;22(6):993–1005. doi: 10.1101/gr.134395.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Le Tallec B, Millot GA, Blin ME, Brison O, Dutrillaux B, Debatisse M. Common fragile site profiling in epithelial and erythroid cells reveals that most recurrent cancer deletions lie in fragile sites hosting large genes. Cell reports. 2013;4(3):420–428. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zimonjic DB, Druck T, Ohta M, Kastury K, Croce CM, Popescu NC, Huebner K. Positions of chromosome 3p14.2 fragile sites (FRA3B) within the FHIT gene. Cancer Res. 1997;57(6):1166–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang H, Qian C, Jenkins RB, Smith DI. Fish mapping of YAC clones at human chromosomal band 7q31.2: identification of YACS spanning FRA7G within the common region of LOH in breast and prostate cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1998;21(2):152–159. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(199802)21:2<152::aid-gcc11>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ried K, Finnis M, Hobson L, Mangelsdorf M, Dayan S, Nancarrow JK, Woollatt E, Kremmidiotis G, Gardner A, Venter D, Baker E, Richards RI. Common chromosomal fragile site FRA16D sequence: identification of the FOR gene spanning FRA16D and homozygous deletions and translocation breakpoints in cancer cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(11):1651–1663. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.11.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mangelsdorf M, Ried K, Woollatt E, Dayan S, Eyre H, Finnis M, Hobson L, Nancarrow J, Venter D, Baker E, Richards RI. Chromosomal fragile site FRA16D and DNA instability in cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60(6):1683–1689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morelli C, Karayianni E, Magnanini C, Mungall AJ, Thorland E, Negrini M, Smith DI, Barbanti-Brodano G. Cloning and characterization of the common fragile site FRA6F harboring a replicative senescence gene and frequently deleted in human tumors. Oncogene. 2002;21(47):7266–7276. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Becker NA, Thorland EC, Denison SR, Phillips LA, Smith DI. Evidence that instability within the FRA3B region extends four megabases. Oncogene. 2002;21(57):8713–8722. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hellman A, Zlotorynski E, Scherer SW, Cheung J, Vincent JB, Smith DI, Trakhtenbrot L, Kerem B. A role for common fragile site induction in amplification of human oncogenes. Cancer Cell. 2002;1(1):89–97. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krummel KA, Roberts LR, Kawakami M, Glover TW, Smith DI. The characterization of the common fragile site FRA16D and its involvement in multiple myeloma translocations. Genomics. 2000;69(1):37–46. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rozier L, El-Achkar E, Apiou F, Debatisse M. Characterization of a conserved aphidicolin-sensitive common fragile site at human 4q22 and mouse 6C1: possible association with an inherited disease and cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23(41):6872–6880. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Curatolo A, Limongi ZM, Pelliccia F, Rocchi A. Molecular characterization of the human common fragile site FRA1H. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46(5):487–493. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pelliccia F, Bosco N, Rocchi A. Breakages at common fragile sites set boundaries of amplified regions in two leukemia cell lines K562—Molecular characterization of FRA2H and localization of a new CFS FRA2S. Cancer Lett. 2010;299(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bosco N, Pelliccia F, Rocchi A. Characterization of FRA7B, a human common fragile site mapped at the 7p chromosome terminal region. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;202(1):47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ma K, Qiu L, Mrasek K, Zhang J, Liehr T, Quintana LG, Li Z. Common fragile sites: genomic hotspots of DNA damage and carcinogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(9):11974–11999. doi: 10.3390/ijms130911974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rajaram M, Zhang J, Wang T, Li J, Kuscu C, Qi H, Kato M, Grubor V, Weil RJ, Helland A, Borrenson-Dale AL, Cho KR, Levine DA, Houghton AN, Wolchok JD, Myeroff L, Markowitz SD, Lowe SW, Zhang M, Krasnitz A, Lucito R, Mu D, Powers RS. Two distinct categories of focal deletions in cancer genomes. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhu Y, McAvoy S, Kuhn R, Smith DI. RORA, a large common fragile site gene, is involved in cellular stress response. Oncogene. 2006;25(20):2901–2908. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McAvoy S, Ganapathiraju S, Perez DS, James CD, Smith DI. DMD and IL1RAPL1: two large adjacent genes localized within a common fragile site (FRAXC) have reduced expression in cultured brain tumors. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2007;119(3–4):196–203. doi: 10.1159/000112061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McAvoy S, Zhu Y, Perez DS, James CD, Smith DI. Disabled-1 is a large common fragile site gene, inactivated in multiple cancers. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47(2):165–174. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zlotorynski E, Rahat A, Skaug J, Ben-Porat N, Ozeri E, Hershberg R, Levi A, Scherer SW, Margalit H, Kerem B. Molecular basis for expression of common and rare fragile sites. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(20):7143–7151. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7143-7151.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Debacker K, Winnepenninckx B, Ben-Porat N, FitzPatrick D, Van Luijk R, Scheers S, Kerem B, Frank Kooy R. FRA18C: a new aphidicolin-inducible fragile site on chromosome 18q22, possibly associated with in vivo chromosome breakage. J Med Genet. 2007;44(5):347–352. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.044628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ragland RL, Glynn MW, Arlt MF, Glover TW. Stably transfected common fragile site sequences exhibit instability at ectopic sites. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47(10):860–872. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Casper AM, Rosen DM, Rajula KD. Sites of genetic instability in mitosis and cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1267:24–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W, Funke R, Gage D, Harris K, Heaford A, Howland J, Kann L, Lehoczky J, LeVine R, McEwan P, McKernan K, Meldrim J, Mesirov JP, Miranda C, Morris W, Naylor J, Raymond C, Rosetti M, Santos R, Sheridan A, Sougnez C, Stange-Thomann N, Stojanovic N, Subramanian A, Wyman D, Rogers J, Sulston J, Ainscough R, Beck S, Bentley D, Burton J, Clee C, Carter N, Coulson A, Deadman R, Deloukas P, Dunham A, Dunham I, Durbin R, French L, Grafham D, Gregory S, Hubbard T, Humphray S, Hunt A, Jones M, Lloyd C, McMurray A, Matthews L, Mercer S, Milne S, Mullikin JC, Mungall A, Plumb R, Ross M, Shownkeen R, Sims S, Waterston RH, Wilson RK, Hillier LW, McPherson JD, Marra MA, Mardis ER, Fulton LA, Chinwalla AT, Pepin KH, Gish WR, Chissoe SL, Wendl MC, Delehaunty KD, Miner TL, Delehaunty A, Kramer JB, Cook LL, Fulton RS, Johnson DL, Minx PJ, Clifton SW, Hawkins T, Branscomb E, Predki P, Richardson P, Wenning S, Slezak T, Doggett N, Cheng JF, Olsen A, Lucas S, Elkin C, Uberbacher E, Frazier M, Gibbs RA, Muzny DM, Scherer SE, Bouck JB, Sodergren EJ, Worley KC, Rives CM, Gorrell JH, Metzker ML, Naylor SL, Kucherlapati RS, Nelson DL, Weinstock GM, Sakaki Y, Fujiyama A, Hattori M, Yada T, Toyoda A, Itoh T, Kawagoe C, Watanabe H, Totoki Y, Taylor T, Weissenbach J, Heilig R, Saurin W, Artiguenave F, Brottier P, Bruls T, Pelletier E, Robert C, Wincker P, Smith DR, Doucette-Stamm L, Rubenfield M, Weinstock K, Lee HM, Dubois J, Rosenthal A, Platzer M, Nyakatura G, Taudien S, Rump A, Yang H, Yu J, Wang J, Huang G, Gu J, Hood L, Rowen L, Madan A, Qin S, Davis RW, Federspiel NA, Abola AP, Proctor MJ, Myers RM, Schmutz J, Dickson M, Grimwood J, Cox DR, Olson MV, Kaul R, Raymond C, Shimizu N, Kawasaki K, Minoshima S, Evans GA, Athanasiou M, Schultz R, Roe BA, Chen F, Pan H, Ramser J, Lehrach H, Reinhardt R, McCombie WR, De La Bastide M, Dedhia N, Blocker H, Hornischer K, Nordsiek G, Agarwala R, Aravind L, Bailey JA, Bateman A, Batzoglou S, Birney E, Bork P, Brown DG, Burge CB, Cerutti L, Chen HC, Church D, Clamp M, Copley RR, Doerks T, Eddy SR, Eichler EE, Furey TS, Galagan J, Gilbert JG, Harmon C, Hayashizaki Y, Haussler D, Hermjakob H, Hokamp K, Jang W, Johnson LS, Jones TA, Kasif S, Kaspryzk A, Kennedy S, Kent WJ, Kitts P, Koonin EV, Korf I, Kulp D, Lancet D, Lowe TM, McLysaght A, Mikkelsen T, Moran JV, Mulder N, Pollara VJ, Ponting CP, Schuler G, Schultz J, Slater G, Smit AF, Stupka E, Szustakowski J, Thierry-Mieg D, Thierry-Mieg J, Wagner L, Wallis J, Wheeler R, Williams A, Wolf YI, Wolfe KH, Yang SP, Yeh RF, Collins F, Guyer MS, Peterson J, Felsenfeld A, Wetterstrand KA, Patrinos A, Morgan MJ, de Jong P, Catanese JJ, Osoegawa K, Shizuya H, Choi S, Chen YJ, International human genome sequencing C Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409(6822):860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tsantoulis PK, Kotsinas A, Sfikakis PP, Evangelou K, Sideridou M, Levy B, Mo L, Kittas C, Wu XR, Papavassiliou AG, Gorgoulis VG. Oncogene-induced replication stress preferentially targets common fragile sites in preneoplastic lesions. A genome-wide study. Oncogene. 2008;27(23):3256–3264. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mimori K, Druck T, Inoue H, Alder H, Berk L, Mori M, Huebner K, Croce CM. Cancer-specific chromosome alterations in the constitutive fragile region FRA3B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(13):7456–7461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dillon LW, Burrow AA, Wang YH. DNA instability at chromosomal fragile sites in cancer. Curr Genomics. 2010;11(5):326–337. doi: 10.2174/138920210791616699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Labib K, Hodgson B. Replication fork barriers: pausing for a break or stalling for time? EMBO Rep. 2007;8(4):346–353. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shah SN, Opresko PL, Meng X, Lee MY, Eckert KA. DNA structure and the Werner protein modulate human DNA polymerase delta-dependent replication dynamics within the common fragile site FRA16D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(4):1149–1162. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang H, Freudenreich CH. An AT-rich sequence in human common fragile site FRA16D causes fork stalling and chromosome breakage in S. cerevisiae. Mol Cell. 2007;27(3):367–379. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Helmrich A, Stout-Weider K, Hermann K, Schrock E, Heiden T. Common fragile sites are conserved features of human and mouse chromosomes and relate to large active genes. Genome Res. 2006;16(10):1222–1230. doi: 10.1101/gr.5335506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Le Beau MM, Rassool FV, Neilly ME, Espinosa R, 3rd, Glover TW, Smith DI, McKeithan TW. Replication of a common fragile site, FRA3B, occurs late in S phase and is delayed further upon induction: implications for the mechanism of fragile site induction. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7(4):755–761. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.4.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang L, Darling J, Zhang JS, Huang H, Liu W, Smith DI. Allele-specific late replication and fragility of the most active common fragile site, FRA3B. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8(3):431–437. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Palakodeti A, Han Y, Jiang Y, Le Beau MM. The role of late/slow replication of the FRA16D in common fragile site induction. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2004;39(1):71–76. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hellman A, Rahat A, Scherer SW, Darvasi A, Tsui LC, Kerem B. Replication delay along FRA7H, a common fragile site on human chromosome 7, leads to chromosomal instability. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(12):4420–4427. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.12.4420-4427.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Handt O, Baker E, Dayan S, Gartler SM, Woollatt E, Richards RI, Hansen RS. Analysis of replication timing at the FRA10B and FRA16B fragile site loci. Chromosome Res. 2000;8(8):677–688. doi: 10.1023/a:1026737203447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Palumbo E, Matricardi L, Tosoni E, Bensimon A, Russo A. Replication dynamics at common fragile site FRA6E. Chromosoma. 2010;119(6):575–587. doi: 10.1007/s00412-010-0279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Palakodeti A, Lucas I, Jiang Y, Young DJ, Fernald AA, Karrison T, Le Beau MM. Impaired replication dynamics at the FRA3B common fragile site. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19(1):99–110. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ozeri-Galai E, Lebofsky R, Rahat A, Bester AC, Bensimon A, Kerem B. Failure of origin activation in response to fork stalling leads to chromosomal instability at fragile sites. Mol Cell. 2011;43(1):122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jiang Y, Lucas I, Young DJ, Davis EM, Karrison T, Rest JS, Le Beau MM. Common fragile sites are characterized by histone hypoacetylation. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(23):4501–4512. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Koch CM, Andrews RM, Flicek P, Dillon SC, Karaoz U, Clelland GK, Wilcox S, Beare DM, Fowler JC, Couttet P, James KD, Lefebvre GC, Bruce AW, Dovey OM, Ellis PD, Dhami P, Langford CF, Weng ZP, Birney E, Carter NP, Vetrie D, Dunham I. The landscape of histone modifications across 1% of the human genome in five human cell lines. Genome Res. 2007;17(6):691–707. doi: 10.1101/gr.5704207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Helmrich A, Ballarino M, Tora L. Collisions between replication and transcription complexes cause common fragile site instability at the longest human genes. Mol Cell. 2011;44(6):966–977. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yunis JJ, Soreng AL, Bowe AE. Fragile sites are targets of diverse mutagens and carcinogens. Oncogene. 1987;1(1):59–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bignell GR, Greenman CD, Davies H, Butler AP, Edkins S, Andrews JM, Buck G, Chen L, Beare D, Latimer C, Widaa S, Hinton J, Fahey C, Fu B, Swamy S, Dalgliesh GL, Teh BT, Deloukas P, Yang F, Campbell PJ, Futreal PA, Stratton MR. Signatures of mutation and selection in the cancer genome. Nature. 2010;463(7283):893–898. doi: 10.1038/nature08768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Beroukhim R, Mermel CH, Porter D, Wei G, Raychaudhuri S, Donovan J, Barretina J, Boehm JS, Dobson J, Urashima M, Mc Henry KT, Pinchback RM, Ligon AH, Cho YJ, Haery L, Greulich H, Reich M, Winckler W, Lawrence MS, Weir BA, Tanaka KE, Chiang DY, Bass AJ, Loo A, Hoffman C, Prensner J, Liefeld T, Gao Q, Yecies D, Signoretti S, Maher E, Kaye FJ, Sasaki H, Tepper JE, Fletcher JA, Tabernero J, Baselga J, Tsao MS, Demichelis F, Rubin MA, Janne PA, Daly MJ, Nucera C, Levine RL, Ebert BL, Gabriel S, Rustgi AK, Antonescu CR, Ladanyi M, Letai A, Garraway LA, Loda M, Beer DG, True LD, Okamoto A, Pomeroy SL, Singer S, Golub TR, Lander ES, Getz G, Sellers WR, Meyerson M. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature. 2010;463(7283):899–905. doi: 10.1038/nature08822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dereli-Oz A, Versini G, Halazonetis TD. Studies of genomic copy number changes in human cancers reveal signatures of DNA replication stress. Mol Oncol. 2011;5(4):308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Saldivar JC, Shibata H, Huebner K. Pathology and biology associated with the fragile FHIT gene and gene product. J Cell Biochem. 2010;109(5):858–865. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lewandowska U, Zelazowski M, Seta K, Byczewska M, Pluciennik E, Bednarek AK. WWOX, the tumour suppressor gene affected in multiple cancers. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;60(Suppl 1):47–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Poulogiannis G, McIntyre RE, Dimitriadi M, Apps JR, Wilson CH, Ichimura K, Luo F, Cantley LC, Wyllie AH, Adams DJ, Arends MJ. PARK2 deletions occur frequently in sporadic colorectal cancer and accelerate adenoma development in Apc mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(34):15145–15150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009941107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhu J, Li X, Kong X, Moran MS, Su P, Haffty BG, Yang Q. Testin is a tumor suppressor and prognostic marker in breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2012;103(12):2092–2101. doi: 10.1111/cas.12020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lee S, Kwon H, Jeong K, Pak Y. Regulation of cancer cell proliferation by caveolin-2 down-regulation and re-expression. Int J Oncol. 2011;38(5):1395–1402. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nair R, Lauks J, Jung S, Cooke NE, de Wit H, Brose N, Kilimann MW, Verhage M, Rhee J. Neurobeachin regulates neurotransmitter receptor trafficking to synapses. J Cell Biol. 2013;200(1):61–80. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201207113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Savelyeva L, Sagulenko E, Schmitt JG, Schwab M. Low-frequency common fragile sites: link to neuropsychiatric disorders? Cancer Lett. 2006;232(1):58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Volders K, Nuytens K, Creemers JW. The autism candidate gene Neurobeachin encodes a scaffolding protein implicated in membrane trafficking and signaling. Curr Mol Med. 2011;11(3):204–217. doi: 10.2174/156652411795243432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.McAvoy S, Ganapathiraju SC, Ducharme-Smith AL, Pritchett JR, Kosari F, Perez DS, Zhu Y, James CD, Smith DI. Non-random inactivation of large common fragile site genes in different cancers. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2007;118(2–4):260–269. doi: 10.1159/000108309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gao G, Kasperbauer JL, Tombers NM, Wang V, Mayer K, Smith DI. A selected group of large common fragile site genes have decreased expression in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2014;53(5):392–401. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.O’Neal J, Gao F, Hassan A, Monahan R, Barrios S, Kilimann MW, Lee I, Chng WJ, Vij R, Tomasson MH. Neurobeachin (NBEA) is a target of recurrent interstitial deletions at 13q13 in patients with MGUS and multiple myeloma. Exp Hematol. 2009;37(2):234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nagoshi H, Taki T, Hanamura I, Nitta M, Otsuki T, Nishida K, Okuda K, Sakamoto N, Kobayashi S, Yamamoto-Sugitani M, Tsutsumi Y, Kobayashi T, Matsumoto Y, Horiike S, Kuroda J, Taniwaki M. Frequent PVT1 rearrangement and novel chimeric genes PVT1-NBEA and PVT1-WWOX occur in multiple myeloma with 8q24 abnormality. Cancer Res. 2012;72(19):4954–4962. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wan L, Han J, Liu T, Dong S, Xie F, Chen H, Huang J. Scaffolding protein SPIDR/KIAA0146 connects the Bloom syndrome helicase with homologous recombination repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(26):10646–10651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220921110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Akasaka T, Balasas T, Russell LJ, Sugimoto KJ, Majid A, Walewska R, Karran EL, Brown DG, Cain K, Harder L, Gesk S, Martin-Subero JI, Atherton MG, Bruggemann M, Calasanz MJ, Davies T, Haas OA, Hagemeijer A, Kempski H, Lessard M, Lillington DM, Moore S, Nguyen-Khac F, Radford-Weiss I, Schoch C, Struski S, Talley P, Welham MJ, Worley H, Strefford JC, Harrison CJ, Siebert R, Dyer MJ. Five members of the CEBP transcription factor family are targeted by recurrent IGH translocations in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL) Blood. 2007;109(8):3451–3461. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-041012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gross E, Meul C, Raab S, Propping C, Avril S, Aubele M, Gkazepis A, Schuster T, Grebenchtchikov N, Schmitt M, Kiechle M, Meijer J, Vijzelaar R, Meindl A, van Kuilenburg AB. Somatic copy number changes in DPYD are associated with lower risk of recurrence in triple-negative breast cancers. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(9):2347–2355. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.van Kuilenburg AB, Meijer J, Mul AN, Hennekam RC, Hoovers JM, de Die-Smulders CE, Weber P, Mori AC, Bierau J, Fowler B, Macke K, Sass JO, Meinsma R, Hennermann JB, Miny P, Zoetekouw L, Vijzelaar R, Nicolai J, Ylstra B, Rubio-Gozalbo ME. Analysis of severely affected patients with dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency reveals large intragenic rearrangements of DPYD and a de novo interstitial deletion del(1)(p13.3p21.3) Hum Genet. 2009;125(5–6):581–590. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0653-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kobunai T, Ooyama A, Sasaki S, Wierzba K, Takechi T, Fukushima M, Watanabe T, Nagawa H. Changes to the dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene copy number influence the susceptibility of cancers to 5-FU-based drugs: data mining of the NCI-DTP data sets and validation with human tumour xenografts. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(4):791–798. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Miller CT, Lin L, Casper AM, Lim J, Thomas DG, Orringer MB, Chang AC, Chambers AF, Giordano TJ, Glover TW, Beer DG. Genomic amplification of MET with boundaries within fragile site FRA7G and upregulation of MET pathways in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2006;25(3):409–418. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Dekaban A. Persisting clone of cells with an abnormal chromosome in a woman previously irradiated. J Nucl Med. 1965;6(10):740–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.