Abstract

Exogenous and endogenous genotoxic agents, such as ionizing radiation and numerous chemical agents, cause DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), which are highly toxic and lead to genomic instability or tumorigenesis if not repaired accurately and efficiently. Cells have over evolutionary time developed certain repair mechanisms in response to DSBs to maintain genomic integrity. Major DSB repair mechanisms include non-homologous end joining and homologous recombination (HR). Using sister homologues as templates, HR is a high-fidelity repair pathway that can rejoin DSBs without introducing mutations. However, HR execution without appropriate guarding may lead to more severe gross genome rearrangements. Here we review current knowledge regarding the factors and mechanisms required for accomplishment of accurate HR.

Keywords: MRN complex, BRCA1, BRCA2, D-loop, Double Holliday junction

Introduction

During the life of any single cell, the genome is continually challenged by a plethora of endogenous and exogenous factors, including free radicals generated from cellular metabolism, ultraviolet light from the sun, and ionizing radiation (IR) [1, 2]. Arising from endogenous (e.g., replication-associated errors and T- and B cell development) and exogenous (e.g., IR and chemotherapeutic agents) sources, double-strand breaks (DSB) are one of the most dangerous of all types of DNA damage because it results in physical cleavage of the DNA backbone [3–7].

Unrepaired or misrepaired DNA damage can result in cell senescence, apoptosis or tumorigenesis. Consequently, cells have evolved numerous highly efficient DNA repair pathways to sense and repair the various types of DNA damage to maintain genomic integrity and stability [8–10]. Two major pathways responsible for DSB repair in eukaryotic cells are non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway and homologous recombination (HR) pathway [11, 12]. Defects in either pathway cause genome instability and promote tumorigenesis [12, 13]. Although it is generally believed that NHEJ is an error-prone pathway and HR is an error-free pathway, mounting evidences implicated that this view is too simplistic [14–18]. Thus, selection of the appropriate pathway is essential and is highly regulated in mammalian cells to maintain genomic stability [19–22]. It is widely accepted that DSBs that occur in the S phase due to collapsed replication forks and in the G2 phase are repaired mainly by HR, while NHEJ functions throughout the cell cycle [23–26]. However, the precise mechanism by which cells select a specific pathway to fix DSBs is not yet known, although some proteins that function in the early steps of both pathways may play key roles in this decision [27, 28].

Briefly, HR uses a sequence similar or identical to the broken DNA as a template, which makes HR the most accurate repair pathway for DSBs. To ensure accuracy, multiple factors are involved [29, 30]. We will discuss those pivotal proteins and steps involved in HR to clarify how cells execute this tightly controlled DNA repair mechanism.

NHEJ or HR? Make a decision

Non-homologous end joining is a relatively simple and straightforward, DSB repair pathway that ligates two DNA ends without requiring an accessible homologous DNA segment [12, 31, 32]. Canonical NHEJ (C-NHEJ) is initiated by the recognition and binding of the broken DSB ends by the Ku70/Ku80 protein complex, followed by the recruitment of the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) [33–35]. Once bound to the broken ends, DNA-PKcs is activated and then phosphorylates itself and other targets, such as Artemis, which exerts nuclease activity to trim the DNA ends [36–39]. Finally, the DNA ligase complex, including DNA ligase IV, X-ray-cross-complementation group 4 (XRCC4), and XRCC4 like factor (XLF)/Cernunnos, is recruited to seal the DNA break [40–49]. A special DNA ligase that is conserved in all eukaryotes but is not essential for DNA replication, DNA ligase IV, is the core C-NHEJ enzyme that catalyzes the final step in joining the ends of the two DNA strands [50]. In addition to the extensively studied C-NEHJ pathway, another alternative NHEJ (Alt-NHEJ) pathway has been uncovered recently [14, 51]. Studies have shown that Alt-NHEJ can ligate DNA ends in the absence of C-NHEJ factors [14, 51]. Interestingly, although the NHEJ pathway is considered to be an inherently mutagenic process, due to the lack of homologous templates, studies in different species suggested that the C-NHEJ is not an intrinsically error-prone pathway and the accuracy of the repair is dictated by the structure of DNA substrates, but not by the C-NHEJ machinery [14]. In contrast to C-NHEJ, Alt-NHEJ-mediated end-joining is an error-prone event and often results in increased risks of chromosome rearrangements [52, 53].

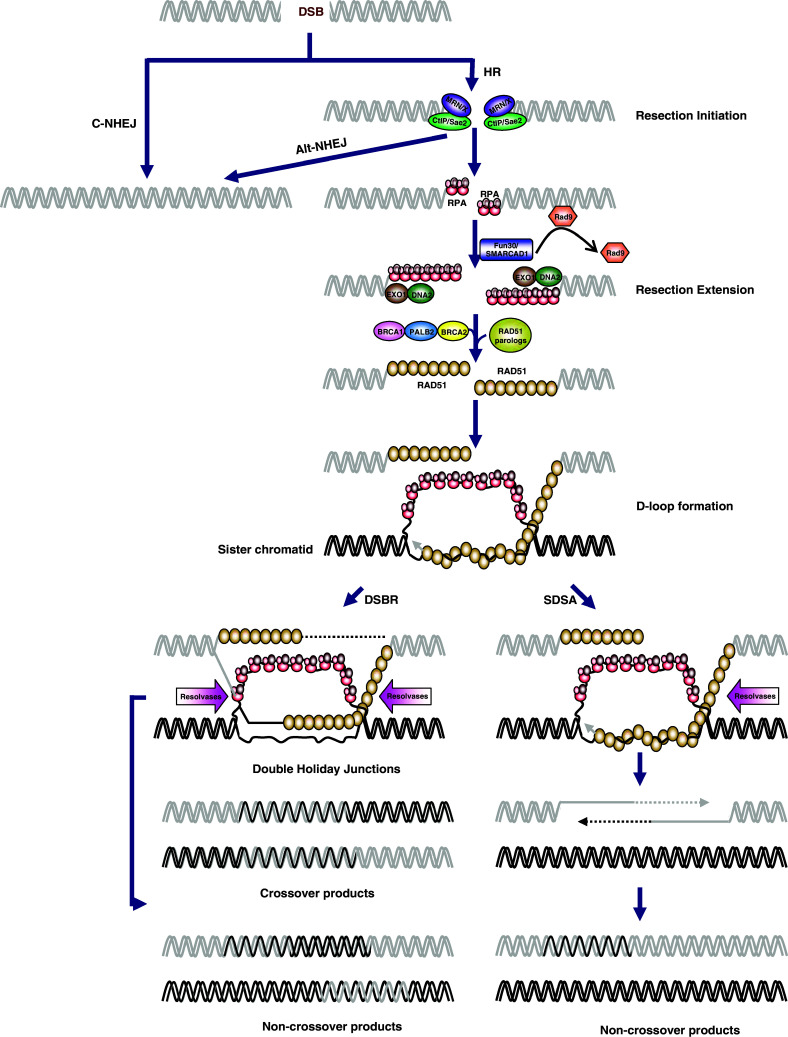

Compared with NHEJ, HR requires the generation of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) intermediates, which are used for homology searching and pairing (Fig. 1) [11, 13]. The sister chromatid is typically used as the template in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle after replication of the DNA [11]. Thus, HR is generally considered to be an error-free pathway in mammalian cells. However, HR is believed to be restricted to particular phases in higher eukaryotes to maintain accuracy, as spurious HR between paternal and maternal chromosomes leads to loss of heterozygosity [15–17, 25]. In general, HR is initiated by 5′-end resection, which generates an extended 3′ single-strand overhang (ssDNA) that then is recognized and subsequently coated by replication protein A (RPA) to remove the secondary structure and protect the ssDNA tail [11, 54]. After RPA binding, RAD51 displaces RPA to form a nucleoprotein filament (presynaptic filament) with the 3′ overhangs at a ratio of one monomer of RAD51 per three nucleotides [11, 54]. The filament then searches for and aligns with its homologous DNA sequence on the sister chromatid to form an intermediate, called a D-loop [11, 54]. After the strand invasion and alignment catalyzed by RAD51 and several other proteins, the D-loop expands and then captures the second 3′ ssDNA overhang generated by resection of the opposite end of the DSB, resulting in the formation of a double Holliday junction (dHJ) [11, 54]. The dHJ can be dissolved or cleaved to yield double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) products. In the process of cleavage, both non-crossover products and crossover products are generated [11, 54]. However, evidence demonstrates that DSB repair is rarely associated with crossovers in somatic cells, which suggests that the high-fidelity dissolution pathway is the major choice in HR repair [11, 54]. An alternative HR model, known as synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA), does not involve Holliday junctions and results in only non-crossover products (Fig. 1) [55].

Fig. 1.

Models of double-strand break repair. Upon induction of DSBs, the broken DNA ends are either coated by Ku complex which initiates the canonical non-homologous end-joining (C-NHEJ) pathway or MRN/X complex which processes the DNA ends into short 3′-single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) tails. The first step of resection by MRN/X complex could trigger either the alternative end-joining (Alt-NHEJ) pathway or homologous recombination (HR) pathway. In HR pathway, the short ssDNA tails that are initially coated by the replication protein A (RPA) complex can be further resected into longer ssDNA tails. In a subsequent step, recombination mediator proteins such as BRCA2 and RAD51 paralogs catalyze the replacement of RPA with RAD51, resulting in the formation of ssDNA-RAD51 nucleoprotein filament. The ssDNA-RAD51 nucleoprotein filament then catalyzes strand invasion into homologous duplex DNA, leading to the formation of D-loop. After DNA synthesis primed by the invading strand, the repair can bifurcate into two alternative sub-pathways referred to as synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA) and double-strand break repair (DSBR). In SDSA, the extended D-loop can be dissolved by specialized DNA helicases and the newly synthesized strand is annealed to the ssDNA tail on the other break end, which is followed by gap-filling DNA synthesis and ligation. The repair products from SDSA are always non-crossover. In DSBR, the second DSB end is captured to form an intermediate with two Holliday junctions, called double Holliday junction (dHJ). dHJ a central intermediate of HR that can be processed to yield crossover or non-crossover recombination products

Although there are differences in fidelity and template requirements, both DSB repair pathways play important roles in maintaining genomic stability in mammalian cells [19]. However, the exact mechanism by which the choice between NHEJ and HR is made remains unclear, although only the appropriate selection results in optimal repair [19, 56]. Non-homologous end joining has long been believed to be the predominant pathway for DSB repair, as it is not restricted in certain cell cycle phases. Observations in several species suggest that HR is active in mainly the late S and G2 phases [57]. This is consistent with the requirement for sister chromatids in HR, which exist only in the S/G2 phase, after DNA synthesis. Moreover, several HR proteins are regulated in a cell cycle-dependent manner. For example, the abundance of the C-terminal binding protein interacting protein (CtIP) is cell cycle regulated, with low CtIP protein in G1 phase and the highest amount observed during S and G2 phases [58]. In addition, CtIP/Sae2 activation is also regulated by the cyclin-dependent protein kinases (CDKs) [59–61]. Besides the cell cycle, the repair mechanism used (HR or NHEJ) also depends on substrate complexity [56]. A frank DSB could be repaired by either NHEJ or HR, while a collapsed replication fork is typically repaired by the HR machinery [56]. Mechanically, the choice of repair pathway may be controlled by the proteins involved in the early stages of both pathways, followed by recruitment of HR- or NHEJ-specific proteins to complete the repair process [56]. A series of studies published recently suggested that tumor suppressor p53-binding protein 1 (53BP1) and tumor suppressor breast cancer 1 (BRCA1) determine whether the HR or NHEJ pathway is used through DNA-end resection control; we will discuss the details in the subsequent section [25, 62].

DNA end resection: the initiation of homologous recombination

When DSBs occur in the S or G2 phase, a process called DNA end resection can be activated, which processes the DSB ends to generate 3′ overhang ssDNA tails [63, 64]. The generation of 3′ ssDNA by end resection not only provides a platform to recruit the proteins that participate in DSB repair but also inhibits NHEJ and triggers HR-mediated DSB repair [65]. The MRN (MRX in yeast) complex (comprised of MRE11, RAD50 and NBS1/Xrs2), CtIP (Sae2 in yeast), Exonuclease 1 (EXO1), nuclease/helicase DNA2, and multiple chromatin remodeling factors are involved in this process [66]. However, if cells are in the G1 phase and lack a homologous duplex DNA template, the presence of Ku70/80 and other proteins prevents resection and, together with the MRN complex, mediates NHEJ pathway initiation.

MRN/X complex

The MRE11, RAD50, and NBS1 (MRN) complex in mammals and fission yeast, and Mre11, Rad50, and Xrs2 (MRX) complex in budding yeast, are the first group of proteins to respond to DSBs [67–70]. When DSBs occur, the MRN complex, comprised of NBS12RAD502MRE11, is recruited to the DNA damage site and carries out at least three functions to initiate DNA repair [71, 72]. First, the MRN complex is capable of sensing the broken DNA end. Second, the MRN complex recruits and activates ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and other pivotal proteins (i.e., tat-interactive protein 60 kDa [TIP60], acetyltransferase, and p53-binding protein 1 [53BP1]) to trigger the DNA damage response (DDR) [73–79]. The DDR includes several programs in different cellular contexts, including cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, senescence, and DNA repair [75, 80, 81]. Third, the MRN complex is critical for DNA resection to generate free ssDNA tails, which are required for HR [68].

MRE11 is the core of the MRN complex; both the ATM activation and end resection functions of the MRN complex require MRE11 activity [75, 82]. MRE11 is a highly conserved protein comprised of an N-terminal phosphoesterase domain and two distinct C-terminal DNA-binding domains. In vitro experiments revealed that MRE11 exhibits a number of enzyme activities, including Mn2+-dependent dsDNA 3′-5′ exonuclease, ssDNA endonuclease, DNA annealing and unwinding [83, 84]. In DNA resection, MRE11 couples with RAD50 to bind to DNA and process the broken DNA end [71]. Structural studies revealed that MRE11 is dimerized through its conserved N-terminal domain [85, 86]. However, although DNA binding and protein dimerization can stabilize each other in this case, dimerization is not required for its nuclease activity, which suggests that the dimerization may not be essential for the end resection directly, but may contribute to other functions, such as assembly of the MRN complex [86]. The early embryonic lethality observed in MRE11-depleted mice implicates that it functions in an essential process [87]. In addition, cells containing nuclease-defective MRE11 suffer growth defects and chromosomal abnormalities and are sensitive to DNA-damaging agents [88]. Furthermore, in vivo experiments in mice, tissue culture, and structural analysis suggest that the nuclease activity of MRE11 is not required for ATM activation but is essential for proper end resection [89]. Interestingly, ATM activation depends on the presence of ssDNA oligonucleotides, although evidence suggests that these ssDNAs do not have to be produced by MRE11 itself. Paradoxically, DNA repair by HR requires exposure of a 3′ overhang ssDNA created by a 5′–3′ exonuclease, while the observed exonuclease activity of MRE11 is opposite and unlikely to perform this role [89, 90]. Notably, a two-step mechanism for MRE11′s role in DSB resection has been proposed recently [91]. In the first step, MRE11 makes the initial single-strand nick through its endonuclease activity to direct repair toward HR [91]. In a second step, MRE11 digests 3′–5′ toward the DNA end through its 3′–5′ exonuclease activity to generate 3′ overhangs [91].

NBS1 is considered to be a regulator in the MRN complex; the complete disruption of NBS1 in mice is lethal, while heterozygotes develop a wide variety of tumors that affect several organs [92–95]. Human NBS1 mutations are responsible for Nijmegen breakage syndrome (NBS), a rare autosomal recessive hereditary disorder that imparts an increased predisposition to the development of malignancies [96]. Cells derived from NBS patients share similar phenomena as ATM mutant cells, including hypersensitivity to IR, chromosomal fragility, and abnormal cell cycle checkpoint regulation [97, 98]. Although the function of NBS1 in HR and end resection is not fully understood, much information suggests that NBS1 plays a critical regulatory role in MRN complex function, even though it lacks DNA-binding and enzymatic activities [85]. NBS1 contains dual phosphopeptide-binding motifs, a Forkhead-associated domain (FHA domain), and a tandem BRCA C-terminal domain (BRCT domain). NBS1 binds to γ-H2AX after DSBs and then recruits MRE11 and RAD50 to the broken DNA [99, 100]. As a result, NBS1 depletion abolishes MRE11 and RAD50 nuclear translocation to DNA damage sites.

RAD50 is a member of the structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) protein family [94, 101]. Like other SMC members, RAD50 contains a long coiled-coil domain, and dimerization of two RAD50s through the coiled-coil domain is essential for MRN complex formation [102, 103]. Separated by the coiled-coil domain, two ATPase motifs are present in both RAD50 termini. Both the N- and C-terminal ATPase motifs have both ATPase and adenylated kinase activities and are required for HR. Briefly, by binding to the DNA duplex through its ATPase motifs and holding the broken ends together using its coiled-coil arms, RAD50 is critical for the DNA-binding and DSB-end-tethering function of the MRN complex [104–106].

CtIP/Sae2

C-terminal binding protein interacting protein was characterized initially as a transcriptional cofactor; it was subsequently shown to be a protein with multiple functions involved in various cellular processes, including cell cycle regulation, transcription regulation, and DSB end resection [107–110]. C-terminal binding protein interacting protein is the human homolog of yeast Sae2, another nuclease whose roles are redundant with those of Mre11 in yeast [111]. However, the observation that CtIP lacks nuclease activity makes MRE11 the only nuclease identified to date that initiates end resection in mammalian cells [111, 112]. Exclusively in S/G2 phase, CtIP localizes to DNA damage sites after DSBs occur and physically interacts with MRN [112–114]. Interestingly, CtIP recruitment to DSBs is delayed compared with the MRN complex [110]. Based on observations that CtIP is phosphorylated before recruitment by ATM, and the fact that ATM activation depends on the MRN complex, the MRN complex may indirectly facilitate CtIP recruitment. Furthermore, the MRN complex counterpart in yeast, the MRX complex, interacts with the chromatin remodeling complexes RSC and INO80 to overcome DNA end barriers for CtIP binding [115, 116]. Although CtIP recruitment requires the MRN complex, emerging evidence suggests that the function of MRN in end resection requires CtIP participation. In vitro experiments revealed that purified recombinant human CtIP protein could stimulate MRE11-RAD50 complex nuclease activity, suggesting that CtIP may redirect MRN function from DNA damage sensing to end resection. The depletion of CtIP results in attenuated recruitment of RPA and ATR to damage sites and reduced HR frequency. Double knockdown of CtIP and MRE11 reduces HR frequency to the same degree as CtIP depletion alone, which is consistent with the concept that CtIP and the MRN complex function in the same pathway.

EXO1/DNA2

As discussed above, MRE11 lacks the 5′-3′ exonuclease activity required to generate the long 3′ssDNA overhangs necessary for RPA binding [66]. Other 5′-3′ exonucleases (e.g., EXO1, DNA2) likely contribute to the extension of DNA end resection, and a two-step model has been proposed for DSB end resection [66]. The MRN/X complex and CtIP/Sae2 initiate DSB resection by removing the first 50–100 nucleotides from the DNA 5′ termini, followed by further resection to generate long 3′ss DNA tails, which are catalyzed by EXO1 exonuclease and DNA2 helicase/endonuclease [66, 117].

Exonuclease 1 is a conserved exonuclease in eukaryotes that was initially identified in Schizosaccharomyces pombe (S. pombe) [118–120]. Exonuclease 1 over-expression suppresses the DNA repair defect of MRX-complex-depleted yeast cells, suggesting that Exo1 can perform some functions of the MRX complex [121]. However, genetic experiments in yeast indicated that Exo1 is not the only activity shared with Mre11, which led to the identification of another nuclease involved in this process, DNA2 [122]. It is now believed that the second step of end resection is performed by two parallel pathways: one pathway depends on EXO1 and the other on DNA2, facilitated by the DNA helicase sgs1 in yeast and its human counterpart, Bloom syndrome protein (BLM) [90, 124–126].

Chromatin remodelers

Genomic DNA is wrapped around histone proteins to form highly condensed DNA-protein fibers that are covered by multiple factors [127]. To overcome the natural barriers that restrict access to DNA, multiple histone-modifying and chromatin-remodeling proteins are recruited to modify the structure of chromatin and hence facilitate DNA repair [128–130]. After development of DSBs, phosphorylation and subsequent acetylation events occur in histone H2A over a large region of the DNA break site to allow recruitment of chromatin unwinding and remodeling complexes [131–138]. Chromatin remodeling complexes use the energy from ATP hydrolysis to induce multiple chromatin changes, including disruption of DNA-histone contacts and repositioning of nucleosomes, which in turn allow repair protein access [115]. Several chromatin remodeling proteins, such as RSC, INO80, SWR1, and SWI/SNF, are reportedly involved in this process to overcome the barrier to repair proteins represented by the tight chromatin structure [139–144].

Recently, two groups independently reported a new ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler in budding yeast, Fun30 (SMARCAD1 in humans) [145, 146]. Fun30 is a member of a highly conserved Etl1 subfamily of Snf2 nucleosome remodeling factors and is implicated in gene silencing. Although Fun30 deletion renders cells hypersensitive to CPT, and its overexpression results in genomic instability, direct evidence of its function in DSB repair was lacking [145, 146]. Based on the observations that Fun30 localizes to DSBs and Fun30 depletion in yeast causes similar extended resection defects as Exo1/Sgs1/Dna2 mutants, but only mild defects in the initial resection step, Fun30 likely participates in DNA end resection extension [145–147]. Fun30-depleted mutants consistently fail to repair DSBs by SSA, an alternative repair pathway that requires extensive resection [145, 146].

This raised the question of whether Fun30 directly or indirectly affects end resection [145, 146]. Evidence supporting the hypothesis that Fun30 directly affects end resection includes: Fun30 is recruited and spreads at DSBs with the same kinetics as other resection extension factors; Fun30 co-immunoprecipitates with Exo1, Dna2, and RPA; and resection enzymes fail to spread further from the break site after recruitment [145, 146]. Meanwhile, evidence against the possibility that Fun30 is indirectly involved in long-range resection includes: no significant changes in transcript accumulation of end resection factors, and no nucleosome position changes are observed [145, 146].

Briefly, the hypothesis was raised that Fun30 functions with either Exo1 or Sgs1 pathways to overcome the resection barrier formed by Rad9-bound chromatin to allow the resection extension step in yeast (Fig. 1) [127, 145, 146]. Rad9 is a checkpoint adaptor protein and binds to methylated K79 residue of histone H3 through its Tudor domain. Histone-bound Rad9 inhibits DNA end resection at both DSBs and uncapped telomeres [148]. Consistently, Fun30 is less important for resection in the absence of Rad9 and either histone H3K79 methylation or γ-H2A, which are essential for Rad9 recruitment [145, 146]. Importantly, the ATPase activity of Fun30 is required for efficient resection [145, 146].

However, other chromatin remodelers, like the previously identified INO80, RSC, and SWR1, are also reportedly associated with resection, suggesting that their functions in end resection are partially redundant [149, 150]. Questions have been raised regarding why many chromatin remolding factors are involved in end resection, and how they collaborate to complete the resection efficiently. It is possible that more chromatin remodelers remain to be identified, and it will be interesting to determine if those chromatin remodelers or others are required for recovery after repairs are complete, for chromatin repacking, and their mechanisms of regulation in this dynamic process.

53BP1/Rif1/PTIP/BRCA1

53BP1 is rapidly localized to the DNA damage site after DSB occurs, and its function in checkpoint regulation was the first noticed [151–154]. Moreover, 53BP1 stimulates NHEJ in specific contexts, including BRCA1-deficient cells, class switch recombination, long-range V(D)J recombination, and fusion of dysfunctional telomeres [155–161]. The ability of 53BP1 to promote NHEJ is explained in part by its ability to block 5′ end resection at DSBs [31, 158, 162].

BRCA1, a tumor suppressor that plays multiple roles in DSB repair, positively regulates end resection by forming a complex with CtIP and MRN [58, 108, 163–166]. Double-strand breaks resection is consistently impaired in the absence of BRCA1, although this may not be due entirely to the lack of the BRCA1-CtIP-MRN complex (BRCA C complex), since cells containing the CtIP mutation, which are incapable of binding BRCA1, have normal resections at DSBs [165, 167–169]. This model explains why the two major mechanisms, HR and NHEJ, are restricted to different phases of the cell cycle. In G1 phase, 53BP1 negatively regulates resection in cells, while BRCA1 promotes 53BP1 removal in S phase to allow resection [22, 56, 158, 170].

Regarding the mechanisms underlying this process, two 53BP1-associated proteins, Rap1-interacting factor 1 (Rif1) and Pax2 transactivation domain interaction protein (PTIP), were recently reported to bind to different 53BP1 sites [171–175]. Rif1 was initially identified as part of the telomeric complex in budding yeast and acts downstream of 53BP1 to inhibit resection in mammalian cells [176]. Indeed, previous results suggested the possibility of Rif1 involvement in DSB responses and the association between Rif1 and 53BP1. In 2004, Silverman et al. reported that Rif1 foci colocalize with 53BP1 foci upon DNA damage, and Rif1 foci formation is dependent on the existence of 53BP1, not other DNA repair proteins [177]. Furthermore, Rif1 depletion in three tumor cell lines resulted in increased sensitivity to IR treatment [177]. BRCA1 is normally present but does not accumulate at DSB sites in G1 cells; if 53BP1 or Rif1 is deleted, BRCA1 forms foci at DSBs in G1 and hence promotes HR [175, 178, 179].

Pax2 transactivation domain interaction protein is known for its role in transcription initiation and was suggested to function in both HR and NHEJ [180–182]. Through its BRCT domains, PTIP interacts directly with phosphorylated 53BP1 upon DNA damage [183]. Similar to Rif1 deletion, PTIP loss also results in increased end resection [184]. In contrast to the only partial contribution of Rif1 to HR defects in BRCA1-deficient cells, PTIP ablation completely rescues HR in BRCA1-deficient cells [161]. Although the exact relationship among 53BP1, Rif1, and PTIP requires further investigation, all three are likely components of a complex that directs cells into the NHEJ pathway instead of the HR pathway [161]. Thus, emerging evidence suggests that DNA end resection is important in the selection between HR and NHEJ, and the on–off switch is mediated at least in part by the controversial roles of 53BP1/Rif1/PTIP or BRCA1.

Presynaptic filament assembly and D-loop formation: central events in homologous recombination

After DNA end resection, the exposed ssDNA overhang long chain is coated with heterotrimeric replication protein A (RPA) [185]. Replaced by RAD51 recombinase, the nucleoprotein filament invades and pairs with intact homologous donor DNA to form a D-loop structure [186].

RAD51

Two recombinases, RAD51 and DMC1, which mediate the process of pairing and strand exchange, exist in eukaryotes [186–189]. While RAD51 is required for both mitotic and meiotic HR, DMC1 is specifically expressed during, and functions in, meiosis [187, 190, 191]. Human RAD51 shares 30 % identity with its bacterial counterpart, RecA, which forms the critical nucleoprotein filament in the SOS response [192–194]. The core domains conserved among the RecA/RAD51 family proteins include two conserved nucleotide-binding motifs, Walker A and B, which are involved in ATP binding and hydrolysis activities [190, 192, 195]. In vitro experiments confirmed that mammalian RAD51 forms a helical nucleoprotein filament and further catalyzes homologous paring and strand exchange [196]. Its function in this step involves three stages. First, RAD51 displaces RPA to form the presynaptic filament [192, 197]. Second, it catalyzes strand invasion and D-loop formation [198, 199]. Finally, RAD51 dissociates from DNA to expose the 3′end required for DNA synthesis [11].

However, RAD51 loading onto ssDNA is a relatively slow process and must be facilitated by several partners to ensure efficiency and correction. First, DNA–RAD51 affinity is weaker than that of DNA–RPA, which means that RAD51 alone cannot displace bound RPA [200–202]. Second, RAD51 has a propensity to bind to dsDNA, which could inhibit presynaptic filament formation; however, this is important during strand invasion, in which RAD51-dsDNA filaments with both invading and donor DNA strands are formed [196, 203]. Increasing evidence suggests that certain recombination mediators, including the tumor suppressor breast cancer susceptibility gene 2 (BRCA2), RAD51 paralogs, and partner and localizer of BRCA2 (PALB2), are required to overcome the inhibitory effect of RPA and ensure RAD51-ssDNA filament formation and invasion [11, 204].

In addition to the recombinant mediators mentioned above that will be discussed in detail later, multiple post-translational modifications are required to regulate RAD51 activity, such as phosphorylation and SUMOylation [205, 206]. One observation suggested that depletion of SUMO E3 ligase MMS21 disrupts RAD51 foci formation, and another that RAD51 is phosphorylated at Ser-14 by casein kinase (CK2) in a DNA damage-responsive manner, which leads to its direct binding to NBS1 [207, 208].

BRCA2

As a tumor suppressor gene that is frequently mutated in breast, ovarian, and other cancers, the link between BRCA2 and HR was first recognized after its identification as a RAD51 interaction partner; subsequent overwhelming evidence suggested BRCA2 to be a mediator in HR [209–213]. Schematically, BRCA2 is a large protein that contains a DNA-binding domain (DBD) that binds to both ssDNA and dsDNA, and eight BRC repeats that bind to RAD51 [210, 214–217]. BRCA2-deficient cells are defective in RAD51 foci formation and homologous repair [212, 218–220]. Initial knowledge of BRCA2 was derived mostly from studies of its orthologs in other species, such as Brh2 in Ustilago maydis and BRC-2 in Caenorhabditis elegans; the full-length BRCA2 protein was purified recently [221–226]. In U. maydis, Brh2 was found to bind to DNA at the resected DSB ends, where both dsDNA and ssDNA exist [222, 227]. These findings, coupled with biochemical data using purified human BRCA2, which showed that BRCA2 could indeed catalyze many steps of the RPA to RAD51 transition, suggested that BRCA2 mediates RAD51 filament formation at the appropriate ssDNA sites and prevents it from binding to dsDNA [195, 226, 228, 229].

RAD51 paralogs

Five canonical RAD51 paralogs have been identified in mammalian cells: RAD51B, RAD51C, RAD51D, XRCC2, and XRCC3 [230, 231]. All five paralogs share 20–30 % amino acid identity and all are essential for cell viability and DSB repair by HR [230, 231]. They are believed to form several functional complexes in cells, including the RAD51B/C/D-XRCC2, RAD51C-XRCC2, RAD51B-RAD51C, RAD51C-XRCC3, RAD51C-RAD51D, and RAD51/D-XRCC2 complexes [230, 231].

The canonical RAD51 paralogs play essential roles in HR and the maintenance of genomic stability. Although the precise molecular mechanisms by which RAD51 paralogs regulate HR remain unclear, evidence indicates that they are involved in both the early and later stages of HR [232–235]. From the beginning, RAD51 paralogs were thought to assist RAD51 in HR initiation [231]. The yeast RAD51 paralogs, Rad55, and Rad57, form a heterodimer to augment Rad51 nucleoprotein filament stabilization and facilitate the strand invasion reaction [236, 237]. Further research demonstrated that on a RAD51 paralog-deficient background, RAD51 foci are abolished in response to IR [231]. As reported, RAD18 is recruited to IR-induced DSBs through recognition and binding to ubiquitinated proteins at the break site [231]. Through its interaction with RAD51C, one of the five RAD51 paralogs, RAD18, transmits DNA damage signals to initiate HR [238, 239]. The function of another RAD51 paralog, XRCC3, is not limited to HR initiation but is extended to later stages, such as HR intermediate formation and resolution, possibly together with RAD51C [240–242].

Interestingly, studies from our and other group have indicated that human Shu complex may represent a non-canonical “RAD51 paralog”, which functions to facilitate the action of RAD51 and may be required for other HR processes [243, 244]. The Shu complex, comprised of Shu1, Shu2, Psy3, and Csm2, was first identified in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. cerevisiae) in a genetic screen to identify top3 suppressors [244–248]. Further studies in S. pombe revealed that Rdl1 and Sws1 are putative Psy3 and Shu2 homologs, respectively, and that they associate with Rlp1 together to form the whole complex [244]. Mutations of any Shu complex members in either budding or fission yeast result in increased sensitivity to the DNA alkylating agent methyl metanesulfonate (MMS) and cross-linking agents [245–247]. Interestingly, mutations in all subunits of the Shu complex in yeast do not cause additive effects different from that of a single mutant, which indicates that these proteins function in the same pathway [245–247]. As a highly conserved protein in eukaryotes, hSWS1 was the first identified human Shu complex component, and hSWS1 ablation reduces the number of RAD51 foci [244]. The original hSWS1 study suggested that XRCC2-RAD51D acts together with hSWS1 to function as a human Shu complex [244]. However, in our attempt to isolate the whole human Shu complex in human cells, hSWS1-associated protein 1 (SWSAP1) was found in a tight complex with SWS1, despite the low sequence similarity between SWSAP1 and its yeast counterparts [243]. Evidence of a direct interaction between SWS1 and SWSAP1, in addition to SWS1 and SWSAP1 interdependence for stability, indicates that they are in a physiological protein complex [243]. Although both SWS1 and SWSAP1 bind to RAD51 paralogs, we questioned the notion of a SWS1-XRCC2-RAD51D complex based on TAP purification findings and false observations of the interdependence between hSWS1 and RAD51 or RAD51 paralogs [243]. Although the precise function of the Shu complex in HR remains unclear, several phenomena, such as SWS1 or SWSAP1 depletion abolishing RAD51 foci formation, suggest that the human Shu complex affects the efficiency and/or timing of HR repair.

PALB2/BRCA1

PALB2 was originally identified as a BRCA2-associated protein that is crucial for BRCA2 function [249, 250]. Interacting with ~ 50 % of cellular BRCA2 through its C-terminal domain, PALB2 is believed to be critical for BRCA2 recruitment after development of DSBs [249, 250]. Several BRCA2 mutations identified in breast cancer patients result in loss of PALB2-binding ability, and a mutation of PALB2 itself was also identified in breast cancer patients [250–255]. PALB2-knockdown cells phenocopy BRCA2 deficiency and exhibit reduced HR frequency, MMC sensitivity, and intra-S-phase checkpoint defects. Further evidence suggested that the binding between PALB2 and BRCA2 is essential for RAD51 loading onto RPA-bound ssDNA and for RAD51-coated nucleoprotein filament formation.

BRCA1 is another tumor suppressor gene that is frequently mutated in different cancers and functions in multiple DNA repair pathways, including HR, NHEJ, single-strand annealing (SSA), and checkpoint regulation. Although previous studies have shown that BRCA1 and BRCA2 coexist within the same biochemical complex, exactly how this complex is assembled remains unclear [218, 256, 257]. Interestingly, recent studies showed that PALB2 can serve as a molecular bridge between BRCA1 and BRCA2 [218, 256, 257]. Through the interaction with BRCA1 by its N-terminal domain and with BRCA2 by its C-terminal domain, PALB2 connects BRCA1 and BRCA2, and the BRCA1-PALB2 association seems to be a prerequisite for BRCA2 and RAD51 loading to the DNA damage site after DSB [256–258].

DSS1

Deleted in split-hand/split foot syndrome (DSS1) was originally identified as one of three candidate genes for an inherited congenital malformation syndrome and then found to interact with BRCA2 [259, 260]. Although the precise mechanism of DSS1 in HR is unclear, the following evidence supports its role in BRCA2 functioning: (1) approximately half of endogenous BRCA2 associates with DSS1, and the majority of DSS1 in cells interacts with BRCA2; (2) BRCA2 point mutants, which are incapable of DSS1 binding, are found in cancer; and (3) depletion of DSS1 results in BRCA2 destabilization [259, 261–263]. Studies performed in U. maydis also revealed that Dss1 interacts with Brh2 and regulates the Brh2-DNA interaction [264].

dHJ dissolution: ensuring accuracy

Besides the D-loop, double Holliday Junction (dHJ) is another key recombination intermediate in HR, which is a mobile junction between four strands of DNA [265, 266]. This structure can be cleaved to yield either crossover or non-crossover products or be dissolved to produce exclusively non-crossover products [266]. In mitotically proliferating cells, the primary mechanism for dHJ processing involves the BTR (BLM-TopoIIIα-RMI1/2) complex, which catalyzes nonnucleolytic dissolution of dHJ [267, 268]. In addition to the dissolution pathway, dHJ can also be nucleolytically processed by structure-selective endonucleases [269–271]. To date, three endonucleases in human cells have been implicated in this cleavage process, namely MUS81-EME1, GEN1, and SLX1 [272–283]. Notably, SLX4, a scaffolding protein, associates with both MUS81 and SLX1 and has been implicated in enhancing the activity of these two nucleases [278, 279, 284, 285].

BLM/BTR complex

Bloom syndrome protein is a member of the RecQ family of DNA helicases and probably the most extensively studied RecQ helicase in humans [286, 287]. BLM gene mutations cause a rare autosomal recessive genetic disorder, called Bloom syndrome (BS), first described in 1954, that is characterized by sun sensitivity, increased susceptibility to infections and diabetes, and a predisposition to a broad array of cancers [267, 288, 289]. Cells derived from BS patients display a marked increase in chromosomal abnormalities, defective response to replication stress, and a highly elevated frequency of sister-chromatid exchanges (SCEs) [267]. The frequent crossover in cells from BS patients suggested a function in ensuring HR accuracy [267]. Biochemically, BLM helicase is an ATP-dependent 3′-5′ DNA helicase capable of unwinding several DNA structures, including dsDNA substrates, G-quartet, D-loop, and dHJ DNA [286]. However, BLM alone is a poorly processive helicase and it forms large, functionally important protein complexes with other HR proteins [267].

The BTR complex, the most well-studied functional BLM complex, comprised of BLM, TopoIIIα, RMI1 (RecQ-mediated genome instability protein 1, BLAP75), and RMI2 (RecQ mediated genome instability protein 2, BLAP18), is a conserved protein complex that regulates HR in favor of non-crossover products via dHJ dissolution [290–293]. TopoIIIα is a type-I topoisomerase that functions to relieve the torsional stress that arises from DNA supercoiling by breaking the DNA backbone and then passing intact DNA through the opening before refilling the break [294, 295]. A linkage between TopoIIIα and DNA helicases was first observed in yeast and E. coli; an association between TopoIIIα and BLM was subsequently demonstrated in human cells [291, 296, 297]. The observation that deleting the TopoIIIα-interaction domain from BLM results in elevated SCEs indicates that the anti-crossover function of BLM requires TopoIIIα involvement [291, 298].

RMI1 and RMI2, are two other proteins identified in human cells that also associate with BLM [292]. Together with TopoIIIα, the BLM-TopoIIIα-RMI1-RMI2 (BTR) complex is highly organized and is referred to as the BLM dissolvasome [267, 299]. Evidence demonstrated that RMI1 could stabilize the whole BTR complex, since it interacts with both BLM and TopoIIIα, and RMI1 depletion affects their protein levels.

RMI2, first identified as a RMI1-binding partner in human cells, binds to RMI1 through the oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding (OB) fold interaction [293]. The association between RMI2 with BLM and Topo IIIα is through RMI1, and RMI2 depletion in cells results in BTR complex destabilization and increased SCE [267].

SPIDR/FIGNL1

Upon DSBs, BLM localizes to the DNA damage site to form discrete foci and perform its dHJ dissolution function. Mounting evidence suggests that BLM may also be involved in other HR steps, such as end resection and D-loop formation [125, 300–304]. However, how BLM is recruited to DNA damage sites and how it collaborates with other proteins to mediate HR remain largely unexplored. Although it is known that DNA repair proteins, such as FANCM, RMI1 and TopoIIIα, contribute to BLM recruitment, we identified a new scaffolding protein involved in DNA repair (SPIDR) and demonstrated that it directly interacted with and mediated BLM foci formation [305, 306]. Multiple regulatory mechanisms may reveal the importance of BLM in DNA repair. Interestingly, SPIDR also binds to RAD51 and contributes to RAD51 recruitment after DSB, which allows it to act as a bridge between RAD51 and BLM, ensuring tight regulation between the early and late HR steps, and maximizing HR repair efficiency [306]. While other HR proteins, such as the BRCA proteins, also affect RAD51 foci formation, they have opposite effects on SCE frequency [307, 308]. Depletion of SPIDR results in an elevated SCE rate, whereas lack of BRCA1/2 leads to a reduction in the SCE frequency [305]. A simple explanation for this phenomenon is that although the overall HR efficiency is reduced in SPIDR-deficient cells, most residual HR intermediates resolve into crossover products, which leads in turn to elevated SCE frequency [305]. Almost simultaneously with our identification of SPIDR, Yuan et al. [308] found that a novel RAD51 binding partner, fidetin-like 1 (FIGNL1), is recruited to DSBs and is involved in homologous recombination repair. Although FIGNL1 interacts with RAD51 through a conserved RAD51-binding domain, FIGNL1 recruitment to DNA damage sites depends on H2AX rather than RAD51 [308]. Interestingly, the authors reported that FIGNL1 also interacts with SPIDR and suggested the existence of a new protein complex consisting of FIGNL1, SPIDR, and other uncharacterized components that accomplish unique functions in HR [308]. The exact underling mechanism of how SPIDR and FIGNL1 are involved in HR appears complex and needs further investigation.

Summary

Double-strand breaks arise from a number of endogenous and exogenous agents that cause interruptions in the continuity of the DNA double helix and are potentially lethal and highly genotoxic. NHEJ and HR are the two major mechanisms that safeguard genome integrity in eukaryotic cells upon occurrence of DSBs. Although it is generally believed that HR is an error-free repair pathway while NHEJ is error-prone, loss of precise HR regulation may lead to undesirable DNA rearrangements, since the required genetic information exchange between different DNA duplexes is potentially dangerous. For this reason, HR is highly regulated to ensure proper repair and protect against genome instability.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to colleagues whose work could not be cited due to space limitations. We would like to thank all our colleagues in the Huang laboratory for insightful discussions. This work was supported in part by National Program for Special Support of Eminent Professionals, National Basic Research Program of China Grants 2012CB944402 and 2013CB911003, National Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholar, National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 31071243, Zhejiang University K.P. Chao’s High Technology Development Foundation, and the China’s Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities. Ting Liu is a member of Feng lab and supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China grant (31171347 and 31090360) and MOST Grants 2012CB966600 and 2013CB945303.

Contributor Information

Ting Liu, Email: liuting518@zju.edu.cn.

Jun Huang, Phone: 86-571-88981391, Email: jhuang@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.van Gent DC, Hoeijmakers JH, Kanaar R. Chromosomal stability and the DNA double-stranded break connection. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2(3):196–206. doi: 10.1038/35056049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiloh Y, Lehmann AR. Maintaining integrity. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(10):923–928. doi: 10.1038/ncb1004-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schar P. Spontaneous DNA damage, genome instability, and cancer–when DNA replication escapes control. Cell. 2001;104(3):329–332. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bredemeyer AL, Sharma GG, Huang CY, Helmink BA, Walker LM, Khor KC, Nuskey B, Sullivan KE, Pandita TK, Bassing CH, Sleckman BP. ATM stabilizes DNA double-strand-break complexes during V(D)J recombination. Nature. 2006;442(7101):466–470. doi: 10.1038/nature04866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang CY, Sharma GG, Walker LM, Bassing CH, Pandita TK, Sleckman BP. Defects in coding joint formation in vivo in developing ATM-deficient B and T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 2007;204(6):1371–1381. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malu S, Malshetty V, Francis D, Cortes P. Role of non-homologous end joining in V(D)J recombination. Immunol Res. 2012;54(1–3):233–246. doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8329-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alt FW, Zhang Y, Meng FL, Guo C, Schwer B. Mechanisms of programmed DNA lesions and genomic instability in the immune system. Cell. 2013;152(3):417–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Setlow RB. Repair deficient human disorders and cancer. Nature. 1978;271(5647):713–717. doi: 10.1038/271713a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hakem R. DNA-damage repair; the good, the bad, and the ugly. EMBO J. 2008;27(4):589–605. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson SP, Bartek J. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature. 2009;461(7267):1071–1078. doi: 10.1038/nature08467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.San Filippo J, Sung P, Klein H. Mechanism of eukaryotic homologous recombination. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:229–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061306.125255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lieber MR. The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:181–211. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.093131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heyer WD, Ehmsen KT, Liu J. Regulation of homologous recombination in eukaryotes. Annu Rev Genet. 2010;44:113–139. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-051710-150955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Betermier M, Bertrand P, Lopez BS. Is non-homologous end-joining really an inherently error-prone process? PLoS Genet. 2014;10(1):e1004086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hicks WM, Kim M, Haber JE. Increased mutagenesis and unique mutation signature associated with mitotic gene conversion. Science. 2010;329(5987):82–85. doi: 10.1126/science.1191125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deem A, Keszthelyi A, Blackgrove T, Vayl A, Coffey B, Mathur R, Chabes A, Malkova A. Break-induced replication is highly inaccurate. PLoS Biol. 2011;9(2):e1000594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iraqui I, Chekkal Y, Jmari N, Pietrobon V, Freon K, Costes A, Lambert SA. Recovery of arrested replication forks by homologous recombination is error-prone. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(10):e1002976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mizuno K, Miyabe I, Schalbetter SA, Carr AM, Murray JM. Recombination-restarted replication makes inverted chromosome fusions at inverted repeats. Nature. 2013;493(7431):246–249. doi: 10.1038/nature11676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sonoda E, Hochegger H, Saberi A, Taniguchi Y, Takeda S. Differential usage of non-homologous end-joining and homologous recombination in double strand break repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5(9–10):1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richardson C, Jasin M. Coupled homologous and nonhomologous repair of a double-strand break preserves genomic integrity in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(23):9068–9075. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.9068-9075.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kasparek TR, Humphrey TC. DNA double-strand break repair pathways, chromosomal rearrangements and cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22(8):886–897. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daley JM, Sung P. 53BP1, BRCA1 and the choice between recombination and end joining at DNA double-strand breaks. Mol Cell Biol. 2014 doi: 10.1128/MCB.01639-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Branzei D, Foiani M. Regulation of DNA repair throughout the cell cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(4):297–308. doi: 10.1038/nrm2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brandsma I, Gent DC. Pathway choice in DNA double strand break repair: observations of a balancing act. Genome Integr. 2012;3(1):9. doi: 10.1186/2041-9414-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapman JR, Taylor MR, Boulton SJ. Playing the end game: DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice. Mol Cell. 2012;47(4):497–510. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karanam K, Kafri R, Loewer A, Lahav G. Quantitative live cell imaging reveals a gradual shift between DNA repair mechanisms and a maximal use of HR in mid S phase. Mol Cell. 2012;47(2):320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothkamm K, Kruger I, Thompson LH, Lobrich M. Pathways of DNA double-strand break repair during the mammalian cell cycle. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(16):5706–5715. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5706-5715.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Symington LS, Gautier J. Double-strand break end resection and repair pathway choice. Annu Rev Genet. 2011;45:247–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.West SC. Molecular views of recombination proteins and their control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4(6):435–445. doi: 10.1038/nrm1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ciccia A, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol Cell. 2010;40(2):179–204. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bunting SF, Callen E, Wong N, Chen HT, Polato F, Gunn A, Bothmer A, Feldhahn N, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Cao L, Xu X, Deng CX, Finkel T, Nussenzweig M, Stark JM, Nussenzweig A. 53BP1 inhibits homologous recombination in Brca1-deficient cells by blocking resection of DNA breaks. Cell. 2010;141(2):243–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis AJ, Chen DJ. DNA double strand break repair via non-homologous end-joining. Transl Cancer Res. 2013;2(3):130–143. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-676X.2013.04.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blunt T, Finnie NJ, Taccioli GE, Smith GC, Demengeot J, Gottlieb TM, Mizuta R, Varghese AJ, Alt FW, Jeggo PA, Jackson SP. Defective DNA-dependent protein kinase activity is linked to V(D)J recombination and DNA repair defects associated with the murine scid mutation. Cell. 1995;80(5):813–823. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90360-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sipley JD, Menninger JC, Hartley KO, Ward DC, Jackson SP, Anderson CW. Gene for the catalytic subunit of the human DNA-activated protein kinase maps to the site of the XRCC7 gene on chromosome 8. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(16):7515–7519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hartley KO, Gell D, Smith GC, Zhang H, Divecha N, Connelly MA, Admon A, Lees-Miller SP, Anderson CW, Jackson SP. DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit: a relative of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and the ataxia telangiectasia gene product. Cell. 1995;82(5):849–856. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90482-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma Y, Pannicke U, Schwarz K, Lieber MR. Hairpin opening and overhang processing by an Artemis/DNA-dependent protein kinase complex in nonhomologous end joining and V(D)J recombination. Cell. 2002;108(6):781–794. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma Y, Schwarz K, Lieber MR. The Artemis:DNA-PKcs endonuclease cleaves DNA loops, flaps, and gaps. DNA Repair (Amst) 2005;4(7):845–851. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goodarzi AA, Yu Y, Riballo E, Douglas P, Walker SA, Ye R, Harer C, Marchetti C, Morrice N, Jeggo PA, Lees-Miller SP. DNA-PK autophosphorylation facilitates Artemis endonuclease activity. EMBO J. 2006;25(16):3880–3889. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Burg M, van Dongen JJ, van Gent DC. DNA-PKcs deficiency in human: long predicted, finally found. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;9(6):503–509. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3283327e41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teo SH, Jackson SP. Identification of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA ligase IV: involvement in DNA double-strand break repair. EMBO J. 1997;16(15):4788–4795. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schar P, Herrmann G, Daly G, Lindahl T. A newly identified DNA ligase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae involved in RAD52-independent repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Genes Dev. 1997;11(15):1912–1924. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.15.1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson TE, Grawunder U, Lieber MR. Yeast DNA ligase IV mediates non-homologous DNA end joining. Nature. 1997;388(6641):495–498. doi: 10.1038/41365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Critchlow SE, Bowater RP, Jackson SP. Mammalian DNA double-strand break repair protein XRCC4 interacts with DNA ligase IV. Curr Biol. 1997;7(8):588–598. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grawunder U, Zimmer D, Fugmann S, Schwarz K, Lieber MR. DNA ligase IV is essential for V(D)J recombination and DNA double-strand break repair in human precursor lymphocytes. Mol Cell. 1998;2(4):477–484. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grawunder U, Zimmer D, Leiber MR. DNA ligase IV binds to XRCC4 via a motif located between rather than within its BRCT domains. Curr Biol. 1998;8(15):873–876. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00349-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahnesorg P, Smith P, Jackson SP. XLF interacts with the XRCC4-DNA ligase IV complex to promote DNA nonhomologous end-joining. Cell. 2006;124(2):301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zha S, Alt FW, Cheng HL, Brush JW, Li G. Defective DNA repair and increased genomic instability in Cernunnos-XLF-deficient murine ES cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(11):4518–4523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611734104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andres SN, Modesti M, Tsai CJ, Chu G, Junop MS. Crystal structure of human XLF: a twist in nonhomologous DNA end-joining. Mol Cell. 2007;28(6):1093–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Y, Chirgadze DY, Bolanos-Garcia VM, Sibanda BL, Davies OR, Ahnesorg P, Jackson SP, Blundell TL. Crystal structure of human XLF/Cernunnos reveals unexpected differences from XRCC4 with implications for NHEJ. EMBO J. 2008;27(1):290–300. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chistiakov DA, Voronova NV, Chistiakov AP. Ligase IV syndrome. Eur J Med Genet. 2009;52(6):373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frit P, Barboule N, Yuan Y, Gomez D, Calsou P. Alternative end-joining pathway(s): bricolage at DNA breaks. DNA Repair (Amst) 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mine-Hattab J, Rothstein R. Increased chromosome mobility facilitates homology search during recombination. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(5):510–517. doi: 10.1038/ncb2472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dion V, Kalck V, Horigome C, Towbin BD, Gasser SM. Increased mobility of double-strand breaks requires Mec1, Rad9 and the homologous recombination machinery. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(5):502–509. doi: 10.1038/ncb2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sung P, Klein H. Mechanism of homologous recombination: mediators and helicases take on regulatory functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(10):739–750. doi: 10.1038/nrm2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bordeianu G, Zugun-Eloae F, Rusu MG. The role of DNA repair by homologous recombination in oncogenesis. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. 2011;115(4):1189–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kakarougkas A, Jeggo PA. DNA DSB repair pathway choice: an orchestrated handover mechanism. Br J Radiol. 2014 doi: 10.1259/bjr.20130685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barlow JH, Lisby M, Rothstein R. Differential regulation of the cellular response to DNA double-strand breaks in G1. Mol Cell. 2008;30(1):73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu X, Baer R. Nuclear localization and cell cycle-specific expression of CtIP, a protein that associates with the BRCA1 tumor suppressor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(24):18541–18549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909494199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huertas P, Cortes-Ledesma F, Sartori AA, Aguilera A, Jackson SP. CDK targets Sae2 to control DNA-end resection and homologous recombination. Nature. 2008;455(7213):689–692. doi: 10.1038/nature07215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Langerak P, Russell P. Regulatory networks integrating cell cycle control with DNA damage checkpoints and double-strand break repair. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;366(1584):3562–3571. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huertas P, Jackson SP. Human CtIP mediates cell cycle control of DNA end resection and double strand break repair. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(14):9558–9565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808906200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Panier S, Boulton SJ. Double-strand break repair: 53BP1 comes into focus. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(1):7–18. doi: 10.1038/nrm3719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Longhese MP, Bonetti D, Manfrini N, Clerici M. Mechanisms and regulation of DNA end resection. EMBO J. 2010;29(17):2864–2874. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mimitou EP, Symington LS. DNA end resection–unraveling the tail. DNA Repair (Amst) 2011;10(3):344–348. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huertas P. DNA resection in eukaryotes: deciding how to fix the break. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(1):11–16. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mimitou EP, Symington LS. DNA end resection: many nucleases make light work. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009;8(9):983–995. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ohta K, Nicolas A, Furuse M, Nabetani A, Ogawa H, Shibata T. Mutations in the MRE11, RAD50, XRS2, and MRE2 genes alter chromatin configuration at meiotic DNA double-stranded break sites in premeiotic and meiotic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(2):646–651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.D’Amours D, Jackson SP. The Mre11 complex: at the crossroads of dna repair and checkpoint signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3(5):317–327. doi: 10.1038/nrm805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Trujillo KM, Roh DH, Chen L, Van Komen S, Tomkinson A, Sung P. Yeast xrs2 binds DNA and helps target rad50 and mre11 to DNA ends. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(49):48957–48964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309877200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lukas C, Melander F, Stucki M, Falck J, Bekker-Jensen S, Goldberg M, Lerenthal Y, Jackson SP, Bartek J, Lukas J. Mdc1 couples DNA double-strand break recognition by Nbs1 with its H2AX-dependent chromatin retention. EMBO J. 2004;23(13):2674–2683. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hopfner KP, Karcher A, Craig L, Woo TT, Carney JP, Tainer JA. Structural biochemistry and interaction architecture of the DNA double-strand break repair Mre11 nuclease and Rad50-ATPase. Cell. 2001;105(4):473–485. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00335-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Costanzo V, Robertson K, Bibikova M, Kim E, Grieco D, Gottesman M, Carroll D, Gautier J. Mre11 protein complex prevents double-strand break accumulation during chromosomal DNA replication. Mol Cell. 2001;8(1):137–147. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Falck J, Petrini JH, Williams BR, Lukas J, Bartek J. The DNA damage-dependent intra-S phase checkpoint is regulated by parallel pathways. Nat Genet. 2002;30(3):290–294. doi: 10.1038/ng845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Uziel T, Lerenthal Y, Moyal L, Andegeko Y, Mittelman L, Shiloh Y. Requirement of the MRN complex for ATM activation by DNA damage. EMBO J. 2003;22(20):5612–5621. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee JH, Paull TT. Direct activation of the ATM protein kinase by the Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 complex. Science. 2004;304(5667):93–96. doi: 10.1126/science.1091496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sun Y, Jiang X, Xu Y, Ayrapetov MK, Moreau LA, Whetstine JR, Price BD. Histone H3 methylation links DNA damage detection to activation of the tumour suppressor Tip60. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(11):1376–1382. doi: 10.1038/ncb1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chailleux C, Tyteca S, Papin C, Boudsocq F, Puget N, Courilleau C, Grigoriev M, Canitrot Y, Trouche D. Physical interaction between the histone acetyl transferase Tip60 and the DNA double-strand breaks sensor MRN complex. Biochem J. 2010;426(3):365–371. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee JH, Goodarzi AA, Jeggo PA, Paull TT. 53BP1 promotes ATM activity through direct interactions with the MRN complex. EMBO J. 2010;29(3):574–585. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yuan J, Chen J. MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 complex dictates DNA repair independent of H2AX. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(2):1097–1104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.078436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grenon M, Gilbert C, Lowndes NF. Checkpoint activation in response to double-strand breaks requires the Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3(9):844–847. doi: 10.1038/ncb0901-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee JH, Paull TT. ATM activation by DNA double-strand breaks through the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 complex. Science. 2005;308(5721):551–554. doi: 10.1126/science.1108297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Haber JE. The many interfaces of Mre11. Cell. 1998;95(5):583–586. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81626-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Paull TT, Gellert M. The 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity of Mre 11 facilitates repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Mol Cell. 1998;1(7):969–979. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Furuse M, Nagase Y, Tsubouchi H, Murakami-Murofushi K, Shibata T, Ohta K. Distinct roles of two separable in vitro activities of yeast Mre11 in mitotic and meiotic recombination. EMBO J. 1998;17(21):6412–6425. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.van den Bosch M, Bree RT, Lowndes NF. The MRN complex: coordinating and mediating the response to broken chromosomes. EMBO Rep. 2003;4(9):844–849. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Williams RS, Moncalian G, Williams JS, Yamada Y, Limbo O, Shin DS, Groocock LM, Cahill D, Hitomi C, Guenther G, Moiani D, Carney JP, Russell P, Tainer JA. Mre11 dimers coordinate DNA end bridging and nuclease processing in double-strand-break repair. Cell. 2008;135(1):97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Buis J, Wu Y, Deng Y, Leddon J, Westfield G, Eckersdorff M, Sekiguchi JM, Chang S, Ferguson DO. Mre11 nuclease activity has essential roles in DNA repair and genomic stability distinct from ATM activation. Cell. 2008;135(1):85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Theunissen JW, Kaplan MI, Hunt PA, Williams BR, Ferguson DO, Alt FW, Petrini JH. Checkpoint failure and chromosomal instability without lymphomagenesis in Mre11(ATLD1/ATLD1) mice. Mol Cell. 2003;12(6):1511–1523. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00455-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stracker TH, Petrini JH. The MRE11 complex: starting from the ends. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12(2):90–103. doi: 10.1038/nrm3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mimitou EP, Symington LS. Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing. Nature. 2008;455(7214):770–774. doi: 10.1038/nature07312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shibata A, Moiani D, Arvai AS, Perry J, Harding SM, Genois MM, Maity R, van Rossum-Fikkert S, Kertokalio A, Romoli F, Ismail A, Ismalaj E, Petricci E, Neale MJ, Bristow RG, Masson JY, Wyman C, Jeggo PA, Tainer JA. DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice is directed by distinct MRE11 nuclease activities. Mol Cell. 2014;53(1):7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dong Z, Zhong Q, Chen PL. The Nijmegen breakage syndrome protein is essential for Mre11 phosphorylation upon DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(28):19513–19516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Paull TT, Gellert M. Nbs1 potentiates ATP-driven DNA unwinding and endonuclease cleavage by the Mre11/Rad50 complex. Genes Dev. 1999;13(10):1276–1288. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Luo G, Yao MS, Bender CF, Mills M, Bladl AR, Bradley A, Petrini JH. Disruption of mRad50 causes embryonic stem cell lethality, abnormal embryonic development, and sensitivity to ionizing radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(13):7376–7381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kang J, Bronson RT, Xu Y. Targeted disruption of NBS1 reveals its roles in mouse development and DNA repair. EMBO J. 2002;21(6):1447–1455. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.6.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Williams BR, Mirzoeva OK, Morgan WF, Lin J, Dunnick W, Petrini JH. A murine model of Nijmegen breakage syndrome. Curr Biol. 2002;12(8):648–653. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00763-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhu J, Petersen S, Tessarollo L, Nussenzweig A. Targeted disruption of the Nijmegen breakage syndrome gene NBS1 leads to early embryonic lethality in mice. Curr Biol. 2001;11(2):105–109. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tauchi H, Kobayashi J, Morishima K, van Gent DC, Shiraishi T, Verkaik NS, vanHeems D, Ito E, Nakamura A, Sonoda E, Takata M, Takeda S, Matsuura S, Komatsu K. Nbs1 is essential for DNA repair by homologous recombination in higher vertebrate cells. Nature. 2002;420(6911):93–98. doi: 10.1038/nature01125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Stracker TH, Morales M, Couto SS, Hussein H, Petrini JH. The carboxy terminus of NBS1 is required for induction of apoptosis by the MRE11 complex. Nature. 2007;447(7141):218–221. doi: 10.1038/nature05740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Williams RS, Dodson GE, Limbo O, Yamada Y, Williams JS, Guenther G, Classen S, Glover JN, Iwasaki H, Russell P, Tainer JA. Nbs1 flexibly tethers Ctp1 and Mre11-Rad50 to coordinate DNA double-strand break processing and repair. Cell. 2009;139(1):87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hopfner KP, Tainer JA. Rad50/SMC proteins and ABC transporters: unifying concepts from high-resolution structures. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13(2):249–255. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.van Noort J, van Der Heijden T, de Jager M, Wyman C, Kanaar R, Dekker C. The coiled-coil of the human Rad50 DNA repair protein contains specific segments of increased flexibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(13):7581–7586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1330706100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lichten M. Rad50 connects by hook or by crook. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12(5):392–393. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0505-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Paull TT. New glimpses of an old machine. Cell. 2001;107(5):563–565. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00591-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.de Jager M, van Noort J, van Gent DC, Dekker C, Kanaar R, Wyman C. Human Rad50/Mre11 is a flexible complex that can tether DNA ends. Mol Cell. 2001;8(5):1129–1135. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hopfner KP, Craig L, Moncalian G, Zinkel RA, Usui T, Owen BA, Karcher A, Henderson B, Bodmer JL, McMurray CT, Carney JP, Petrini JH, Tainer JA. The Rad50 zinc-hook is a structure joining Mre11 complexes in DNA recombination and repair. Nature. 2002;418(6897):562–566. doi: 10.1038/nature00922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Schaeper U, Subramanian T, Lim L, Boyd JM, Chinnadurai G. Interaction between a cellular protein that binds to the C-terminal region of adenovirus E1A (CtBP) and a novel cellular protein is disrupted by E1A through a conserved PLDLS motif. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(15):8549–8552. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yu X, Wu LC, Bowcock AM, Aronheim A, Baer R. The C-terminal (BRCT) domains of BRCA1 interact in vivo with CtIP, a protein implicated in the CtBP pathway of transcriptional repression. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(39):25388–25392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.39.25388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wong AK, Ormonde PA, Pero R, Chen Y, Lian L, Salada G, Berry S, Lawrence Q, Dayananth P, Ha P, Tavtigian SV, Teng DH, Bartel PL. Characterization of a carboxy-terminal BRCA1 interacting protein. Oncogene. 1998;17(18):2279–2285. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.You Z, Shi LZ, Zhu Q, Wu P, Zhang YW, Basilio A, Tonnu N, Verma IM, Berns MW, Hunter T. CtIP links DNA double-strand break sensing to resection. Mol Cell. 2009;36(6):954–969. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sartori AA, Lukas C, Coates J, Mistrik M, Fu S, Bartek J, Baer R, Lukas J, Jackson SP. Human CtIP promotes DNA end resection. Nature. 2007;450(7169):509–514. doi: 10.1038/nature06337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Takeda S, Nakamura K, Taniguchi Y, Paull TT. Ctp1/CtIP and the MRN complex collaborate in the initial steps of homologous recombination. Mol Cell. 2007;28(3):351–352. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Limbo O, Chahwan C, Yamada Y, de Bruin RA, Wittenberg C, Russell P. Ctp1 is a cell-cycle-regulated protein that functions with Mre11 complex to control double-strand break repair by homologous recombination. Mol Cell. 2007;28(1):134–146. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chen L, Nievera CJ, Lee AY, Wu X. Cell cycle-dependent complex formation of BRCA1.CtIP.MRN is important for DNA double-strand break repair. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(12):7713–7720. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710245200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tsukuda T, Fleming AB, Nickoloff JA, Osley MA. Chromatin remodelling at a DNA double-strand break site in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2005;438(7066):379–383. doi: 10.1038/nature04148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Liang B, Qiu J, Ratnakumar K, Laurent BC. RSC functions as an early double-strand-break sensor in the cell’s response to DNA damage. Curr Biol. 2007;17(16):1432–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Yeeles JT, Dillingham MS. The processing of double-stranded DNA breaks for recombinational repair by helicase-nuclease complexes. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9(3):276–285. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Szankasi P, Smith GR. A role for exonuclease I from S. pombe in mutation avoidance and mismatch correction. Science. 1995;267(5201):1166–1169. doi: 10.1126/science.7855597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lieber MR. The FEN-1 family of structure-specific nucleases in eukaryotic DNA replication, recombination and repair. BioEssays. 1997;19(3):233–240. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Tishkoff DX, Boerger AL, Bertrand P, Filosi N, Gaida GM, Kane MF, Kolodner RD. Identification and characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae EXO1, a gene encoding an exonuclease that interacts with MSH2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(14):7487–7492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tsubouchi H, Ogawa H. Exo1 roles for repair of DNA double-strand breaks and meiotic crossing over in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11(7):2221–2233. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.7.2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zhu Z, Chung WH, Shim EY, Lee SE, Ira G. Sgs1 helicase and two nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 resect DNA double-strand break ends. Cell. 2008;134(6):981–994. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Symington LS. Role of RAD52 epistasis group genes in homologous recombination and double-strand break repair. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66(4):630–670. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.4.630-670.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Nimonkar AV, Ozsoy AZ, Genschel J, Modrich P, Kowalczykowski SC. Human exonuclease 1 and BLM helicase interact to resect DNA and initiate DNA repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(44):16906–16911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809380105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Niu H, Chung WH, Zhu Z, Kwon Y, Zhao W, Chi P, Prakash R, Seong C, Liu D, Lu L, Ira G, Sung P. Mechanism of the ATP-dependent DNA end-resection machinery from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2010;467(7311):108–111. doi: 10.1038/nature09318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Chen H, Symington LS. Overcoming the chromatin barrier to end resection. Cell Res. 2013;23(3):317–319. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Unal E, Arbel-Eden A, Sattler U, Shroff R, Lichten M, Haber JE, Koshland D. DNA damage response pathway uses histone modification to assemble a double-strand break-specific cohesin domain. Mol Cell. 2004;16(6):991–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.van Attikum H, Gasser SM. The histone code at DNA breaks: a guide to repair? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(10):757–765. doi: 10.1038/nrm1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Altaf M, Saksouk N, Cote J. Histone modifications in response to DNA damage. Mutat Res. 2007;618(1–2):81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Rogakou EP, Pilch DR, Orr AH, Ivanova VS, Bonner WM. DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(10):5858–5868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kusch T, Florens L, Macdonald WH, Swanson SK, Glaser RL, Yates JR, 3rd, Abmayr SM, Washburn MP, Workman JL. Acetylation by Tip60 is required for selective histone variant exchange at DNA lesions. Science. 2004;306(5704):2084–2087. doi: 10.1126/science.1103455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Downs JA, Allard S, Jobin-Robitaille O, Javaheri A, Auger A, Bouchard N, Kron SJ, Jackson SP, Cote J. Binding of chromatin-modifying activities to phosphorylated histone H2A at DNA damage sites. Mol Cell. 2004;16(6):979–990. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Thiriet C, Hayes JJ. Chromatin in need of a fix: phosphorylation of H2AX connects chromatin to DNA repair. Mol Cell. 2005;18(6):617–622. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Chowdhury D, Keogh MC, Ishii H, Peterson CL, Buratowski S, Lieberman J. Gamma-H2AX dephosphorylation by protein phosphatase 2A facilitates DNA double-strand break repair. Mol Cell. 2005;20(5):801–809. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Shogren-Knaak M, Ishii H, Sun JM, Pazin MJ, Davie JR, Peterson CL. Histone H4-K16 acetylation controls chromatin structure and protein interactions. Science. 2006;311(5762):844–847. doi: 10.1126/science.1124000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Keogh MC, Kim JA, Downey M, Fillingham J, Chowdhury D, Harrison JC, Onishi M, Datta N, Galicia S, Emili A, Lieberman J, Shen X, Buratowski S, Haber JE, Durocher D, Greenblatt JF, Krogan NJ. A phosphatase complex that dephosphorylates gammaH2AX regulates DNA damage checkpoint recovery. Nature. 2006;439(7075):497–501. doi: 10.1038/nature04384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Yuan J, Adamski R, Chen J. Focus on histone variant H2AX: to be or not to be. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(17):3717–3724. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Neely KE, Hassan AH, Brown CE, Howe L, Workman JL. Transcription activator interactions with multiple SWI/SNF subunits. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(6):1615–1625. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.6.1615-1625.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.van Attikum H, Fritsch O, Hohn B, Gasser SM. Recruitment of the INO80 complex by H2A phosphorylation links ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling with DNA double-strand break repair. Cell. 2004;119(6):777–788. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]