Abstract

Aim

This study aimed to clarify the association between treatment status (untreated or treated) at the start of community mental health outreach services and service intensity.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study was conducted using the Tokorozawa City mental health outreach service users' data. Treatment status at the start of service (exposure variable) and the service intensity (outcome variables) were taken from clinical records. Poisson regression and linear regression analyses were conducted. The frequency of medical or social service use 12 months after service initiation was also calculated. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry (No. A2020‐081).

Results

Of 89 people, 37 (42%) were untreated. Family members in the untreated group were more likely to be targets or recipients of services than in the treated group (b = 0.707, p < 0.001, Bonferroni‐adjusted p < 0.001). Compared to the treated group, the untreated group received fewer services themselves (b = −0.290, p = 0.005), and also fewer services by telephone (b = −0.252, p = 0.012); by contrast, they received more services at the health center (b = 0.478, p = 0.031) and for family support (b = 0.720, p = 0.024), but these significant differences disappeared after Bonferroni adjustment. At least 11% of people in the untreated group were hospitalized and 35% were outpatients 12 months after service initiation.

Conclusion

Family involvement may be a key service component for untreated people. The service intensity with and without treatment may vary by service location.

Keywords: community mental health, outreach, service intensity, treatment discontinuation, untreated

INTRODUCTION

Community support for people with untreated mental health problems is a global issue. While the use of mental health services has increased over the decades, many people (even those with a diagnosis of mental illness) are still not engaged with such services including any treatment. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 Whereas some people with untreated symptoms go into remission without treatment, others experience persistent or worsening symptoms and have a poor long‐term prognosis. 5 For example, according to systematic reviews, a longer duration of untreated status was associated with more severe positive and negative symptoms by psychosis 6 , 7 and poorer social functioning. 7 , 8 In addition, even once connected to a mental health service, people often discontinue treatment, resulting in a poor prognosis and recurrence. 9

There are several reasons that people with mental health problems do not connect to mental health services, including self‐stigma 10 , 11 and lack of awareness of the need for support. 12 In addition, while untreated people often seek help from family members, 13 mental health service utilization is lower when one or more family members have untreated mental health problems. 14 , 15 Therefore, relevant interventions need to include services both for people with mental health problems, either untreated or with interrupted treatment, and their families.

Community mental health outreach teams in the local public sector play a role in reaching out to untreated populations. 16 These teams are typically multidisciplinary and deliver various types of services to people in their homes, public spaces, or other settings. 16 , 17 Such services include connecting people to existing medical and social resources in the community, as well as treating psychiatric symptoms and providing assistance with daily living and with decision‐making about treatment and other issues. 16 According to systematic reviews, several models of community mental health outreach are effective in reducing the duration and frequency of psychiatric hospital admissions, 18 , 19 alleviating psychiatric symptoms, 18 , 20 and achieving other outcomes. The best‐known community mental health outreach model may be Assertive Community Treatment (ACT), which targets only people with severe mental illness. 18 , 19 It has been reported that services are more prevalent in patients with more severe mental illness, 21 such as schizophrenia. Other models that do not limit the target population to people with severe mental illness have been developed in a variety of ways based on national and regional health systems. 16 For example, there are community outreach services specifically for homeless and rural populations. 16 While the effectiveness of community mental health outreach has been reported by many studies worldwide, actual services may vary widely between countries.

In Japan, which has the highest number of psychiatric beds in the world, 22 community mental health outreach services have been spreading over the past two decades. Most of these are visiting nurse services. Also, a very small number of ACT and other programs for people with severe mental illness have been implemented in Japan, and have shown positive results in reducing psychiatric symptoms 23 and hospitalization 24 , 25 , 26 or improving functioning. 23 , 24 , 27 In particular, the services of medical support for psychiatric symptoms and assistance with daily living tasks were more common in previous studies of outreach focused mainly on people with a psychiatric diagnosis (severe mental illness) who discontinued or did not receive long‐term treatment. 26 , 27 However, these services seldom provide services to people with undiagnosed mental health problems. In addition, many existing services are provided not by the community public health sector, but by individual medical facilities of private corporations in the Japanese medical insurance system that focus on treating people already diagnosed with a psychiatric illness. In other words, the sustainability and dissemination of care for people with undiagnosed mental health problems may be limited, and service engagement among such people remains an issue in Japan.

To address this unmet community need, a community mental health outreach team was established in 2015 by a local public organization in Tokorozawa City, Japan, to provide support to a wide variety of people with untreated mental health issues, including youth, people with social withdrawal, and those who have difficulty seeking help. Led by the local government rather than a medical institution, the team is able to conduct outreach activities targeting people with untreated mental health problems, as in other countries. 16 However, it is unclear how such services are provided. Thus far, no studies thus far have examined the actual support provided by outreach services for people with untreated mental health problems in Japan. Services provided by the outreach team may differ between untreated and treated cases. Understanding the outreach service for people with untreated mental health problems would help in developing efficient and sustainable support systems. Therefore, we aimed to clarify the association between treatment conditions (having been treated or not) at the start of outreach services and service intensity in Japan, using data from the community mental health outreach service in Tokorozawa City. In this study, service intensity included the number and minutes of services needed, service type, service location, and service recipient.

METHODS

Study design and settings

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using the service and clinical data of individuals who started using services provided by the Tokorozawa City mental health outreach team between October 1, 2015, and March 31, 2020. Participants' demographic and clinical characteristics (including treatment conditions as an exposure variable) were obtained from clinical records at the start of outreach services. As outcome variables, data on service intensity were obtained from clinical data recorded in electronic charts up to March 31, 2020. Additionally, data on the use of medical and social services up to 12 months after the start of outreach services were obtained from subsequent assessment records. The data management process to ensure data quality was as follows. Two of the outreach staff members served as data managers, supporting other staff members with filling in incomplete or missing data and performing data anonymization. Next, the research members created the study dataset and discussed data collection with the outreach staff. This process ensured the quality of the data.

Tokorozawa City is located near Tokyo, and has a population of approximately 340,000. Its mental health outreach team was established on October 1, 2015, and consists of multidisciplinary professionals, including a doctor, nurses, psychologists, social workers, and occupational therapists. While each service user is typically assigned a primary care professional—often referred to as a case manager—multiple team members are involved for each user. The outreach team members share information closely by meeting every weekday morning and occasionally reviewing all cases. They receive training by mental health professionals on an irregular basis and learn a variety of skills to enhance the quality of their services. Thus, depending on the case, a variety of techniques that take advantage of the expertise of each profession (e.g., family support, 28 cognitive‐behavioral therapy, 29 and recovery model 30 ) is employed. While the Tokorozawa Outreach Team had not previously undergone a fidelity review, a supervisor with prior experience in ACT fidelity review supported the team building when the team launched.

The team provides a transit‐type service aimed at transitioning outreach service users to other medical and social resources in the community. The team provides primary care and also specialized treatment based on service users' needs. For people who are untreated at the start of outreach services, transition support is provided to connect them to hospitals if they need specialized treatment, such as medication. In practice, however, some untreated people have difficulty connecting with other medical or social services. In such cases, the outreach team supports their community life, instead of other community resources. It is also possible that outreach service users' problems may be fully or partially resolved without connecting them to other resources. This outreach team does not limit the duration of services for each user. Although the frequency of service use by each user varies, the team has provided services 24 h a day, 365 days a year to a variety of individuals who require support. There is no financial burden on users since the costs of the outreach service are covered by the Tokorozawa City budget.

Participants

A total of 113 people started using services provided by the Tokorozawa City mental health outreach team between October 1, 2015, and March 31, 2020. Most users of the outreach services start availing of them through referrals from the Tokorozawa City Health Center. The Tokorozawa City Health Center offers consultation for cases of mental health problems to citizens, families, schools and other related organizations, and other departments of the municipal government. The Tokorozawa City Mental Health Consultation Department screens these cases and refers them to the outreach team when social workers are unable to handle the case alone. As a result, the outreach team has to manage the more challenging cases, such as those of patients with schizophrenia who tend to be isolated from the community. No exclusion criteria were established. All data were obtained by reading and transcribing existing clinical records. Informed consent was not required since the study did not involve any invasion or intervention. Instead, necessary information about the study was posted on the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry's website and in the Tokorozawa City Health Center to ensure that study participants had the opportunity to refuse participation. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry (No. A2020‐081).

Measures

Treatment status at the start of outreach service use

The records at the start of service use contained information about treatment status (having been treated or not). Untreated refers to both pharmacologically untreated and nonpharmacologically untreated. In addition, in this study, “untreated” was defined as no treatment or treatment discontinuation among people with any of the following life problems caused by psychiatric symptoms (A–C):

(A) Serious continuous problems in fulfilling social roles (e.g., employment, school attendance, sheltered workshop attendance, and housework) for more than 6 months.

(B) Serious problems in carrying out tasks necessary for community life (e.g., those related to nutrition, hygiene, money, safety, human relations, document management, and transportation) by themselves.

(C) Being withdrawn at home for more than 6 months without going to work or school and having little contact with people other than family members as a life problem caused by psychiatric symptoms.

Having these life problems was included in the induction criteria for this outreach team service use. The records at the start of service use were entered by the outreach staff based on the user's situation.

Service intensity

Service intensity refers to the frequency or duration of service contacts that a service user receives over a certain period of time. Information on the intensity of outreach services was taken from clinical data recorded in electronic charts. While the target population of this study was people who started using the outreach service after October 1, 2015, we used service data from November 2018 and later, when electronic medical records were implemented. No data on service use were available prior to the introduction of electronic records.

On the electronic records, outreach staff entered information about the minutes of services for each service. Thus, service intensity data on the number and minutes of services was available. To assess service intensity outcomes (number of services per month), we used data according to the following variables:

-

(1)

Service locations: Service locations were divided into three categories: telephone, service at the health center with the community mental health outreach team, and service outside of the health center, such as at service users' homes and schools.

-

(2)

Service targets or recipients: The family members of the service users and other key persons may also be recipients of the outreach services. This study addressed the number of outreach services provided to the following four types of targets or recipients: service users themselves, service users' family members, related organizations, and absence. If the services were simultaneously provided to the service users themselves and their family members, both were considered as recipients. If the outreach staff could not meet the service users themselves and therefore provided services through their family member, only the latter was regarded as the recipient. In rare cases, the family members of the service user may also be registered as service users if they require outreach support as service users rather than as family members. We also used the “absence” category if staff members could not provide services when they visited service users or family.

-

(3)

Service types related to medical treatment: Outreach services related to medical treatment included the following five types: hospital visits, consultations, house calls, hospitalizations, and hospital discharges.

To assess service intensity outcomes (minutes of services per month), we used data according to the following variables:

-

(1)

Service locations: Service locations were divided into three categories: telephone, service at the health center with the community mental health outreach team, and service outside of the health center, such as at service users' homes and schools.

-

(2)

Service types: Each outreach service was divided into the following 10 types: assistance with daily living tasks, family support, services for psychiatric symptoms, services for physical health, crisis services, consultation on medical treatment, services related to employment or school attendance, social services, services related to interpersonal relations, and services related to information sharing.

Use of medical or social services 12 months after starting outreach services

Data on the use of medical or social services 12 months after the start of outreach services were obtained from subsequent assessment records. We obtained information on whether the service users were psychiatric inpatients, psychiatric outpatients, using psychiatric day care or short care, or using social services.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Data from assessment records at the start of outreach services contained the following variables: sex, age, living situation, problems in daily life, psychiatric consultation history, diagnosis based on the ICD‐10 classification, hospitalization in the past 12 months, mental disability certificate, and disability pension.

Statistical analysis

First, demographic and clinical characteristics between treated and untreated groups were compared using the t‐test or Fisher's exact test. Second, to examine the associations between treatment status at the start of outreach services (untreated or treated) and service intensity, regression analyses were conducted for each service data outcome. Outcomes involving discrete quantities (i.e., service locations, service targets or recipients, and service types to medical treatment) were considered to follow a Poisson distribution; therefore, Poisson regression analyses were conducted. On the other hand, a lognormal distribution was observed in continuous quantity outcomes (i.e., service locations and service types); therefore, linear regression analyses were conducted for each service use outcome after adding 1 to each data and logarithmic transformation, since log transformation is not possible when data contain 0. All regression analyses were adjusted for sex, age, and schizophrenia diagnosis, since it has been reported that service intensity is higher among patients with more severe mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia. 21 For multiple comparisons, we calculated Bonferroni‐adjusted p‐values considering the number of tests. The number and prevalence of medical or social service use 12 months after the start of outreach service are also shown with descriptive statistics in each group. Data with no missing values for variables used in the Poisson regression analysis were included in all analyses. Statistical significance was set at 0.05. All analyses were conducted using R statistical software (Version 4.0.3, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing). The packages “readxl” and “dplyr” were used for data preprocessing.

RESULTS

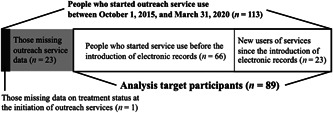

Of 113 people who started outreach service use between October 1, 2015, and March 31, 2020, 89 were included in the current analysis, after excluding those missing outreach service data (n = 23) or data on treatment status at the initiation of outreach services (n = 1) (Figure 1). Of these 89 individuals, 37 (42%) were not receiving medical treatment at the start of outreach service use, while 52 (58%) were (Table 1). Sixty‐two percent of individuals lived with family: 70% of the untreated group and 56% of the treated group were living with their families. Many participants had life problems caused by psychiatric symptoms, for instance serious problems fulfilling social roles (untreated: 84%; treated: 83%), serious problems carrying out tasks (untreated: 87%; treated: 73%), and being withdrawn at home (untreated: 70%; treated: 54%). Psychiatric consultation history (untreated: 76%; treated: 96%, p = 0.001), diagnosis (untreated: 65%; treated: 96%, p < 0.001), mental disability certificate (untreated: 11%; treated: 58%, p < 0.001), and disability pension (untreated: 14%; treated: 34%, p = 0.016) were less frequent in the untreated group than in the treated group, with significant differences between the two groups. Twenty‐four (65%) people in the untreated group and 42 (81%) in the treated group were receiving support prior to the introduction of electronic medical records. Approximately 27 months of service data per person were included in the analysis (untreated group: average 28.4 ± 8.5 months; treated group: average 26.5 ± 10.9 months).

Figure 1.

Study participants.

Table 1.

Participants' demographic and clinical characteristics at the start of community mental health outreach service use in Japan (n = 89).

| Outreach service users (n = 89) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| People who were not receiving medical treatment (n = 37) | People who were receiving medical treatment (n = 52) | p‐valuea | |||

| n (Mean) | % (SD) | n (Mean) | % (SD) | ||

| Sex (male) | 19 | 51 | 27 | 52 | >0.999 |

| Age, years (Mean ± SD) | M = 47.4 | SD = 14.7 | M = 44.1 | SD = 15.5 | 0.310 |

| Living situation | 0.370 | ||||

| Living alone | 11 | 30 | 19 | 37 | |

| Living with family | 26 | 70 | 29 | 56 | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7 | |

| Life problems caused by psychiatric symptoms | |||||

| A. Serious problems in fulfilling social rolesb | 31 | 84 | 43 | 83 | 0.521 |

| B. Serious problems in carrying out tasksc | 32 | 87 | 38 | 73 | 0.567 |

| C. Being withdrawn at homed | 26 | 70 | 28 | 54 | 0.364 |

| Psychiatric consultation history | 0.001 | ||||

| Have | 28 | 76 | 50 | 96 | |

| Not have | 7 | 19 | 0 | 0 | |

| Missing | 2 | 5 | 2 | 4 | |

| Diagnosis based on the ICD‐10 classification | |||||

| Have been diagnosed | 24 | 65 | 50 | 96 | <0.001 |

| Mental disorders due to known physiological conditions (F0) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | |

| Mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use (F1) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Schizophrenia, schizotypal, delusional, and other non‐mood psychotic disorders (F2) | 16 | 43 | 25 | 48 | |

| Mood [affective] disorders (F30–F31) | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | |

| Mood [affective] disorders (F32–F39) | 2 | 5 | 13 | 25 | |

| Anxiety, dissociative, stress‐related, somatoform, and other nonpsychotic mental disorders (F4) | 3 | 8 | 3 | 6 | |

| Behavioral syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors (F5) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Disorders of adult personality and behavior (F6) | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Intellectual disabilities (F7) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Pervasive and specific developmental disorders (F8) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Epilepsy and recurrent seizures (G4) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Unknown/undiagnosed | 13 | 35 | 1 | 2 | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Hospitalization in the past 12 months | 0.086 | ||||

| Have been hospitalized | 6 | 16 | 18 | 35 | |

| Have not been hospitalized | 27 | 73 | 31 | 60 | |

| Missing | 4 | 11 | 3 | 6 | |

| Mental disability certificate | <0.001 | ||||

| Have | 4 | 11 | 30 | 58 | |

| Not have | 32 | 87 | 22 | 42 | |

| Missing | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Disability pension | 0.016 | ||||

| Have received | 5 | 14 | 20 | 34 | |

| Have not received | 32 | 87 | 32 | 62 | |

T‐test or Fisher's exact test were used.

Serious continuous problems in fulfilling social roles (e.g., employment, school attendance, sheltered workshop attendance, and housework) for more than 6 months.

Serious problem in carrying out tasks necessary for community life (e.g., those related to nutrition, hygiene, money, safety, human relations, document management, and transportation) by himself/herself.

Being withdrawn at home for more than 6 months without going to work or school and having little contact with people other than family members.

Tables 2 and 3 show the associations between treatment status at the start of outreach services and each service intensity outcome. In the analysis using the number of services as the outcome, family members were more likely to be targets or recipients of services in the untreated group than in the treated group (b = 0.707, p < 0.001). This significant difference remained after Bonferroni adjustment (Bonferroni‐adjusted p < 0.001). On the other hand, service users themselves were less likely to be targets or recipients of services in the untreated group than in the treated group (b = −0.290, p = 0.005), and those in the untreated group received fewer services by telephone than those in the treated group (b = −0.252, p = 0.012). These significant differences, however, disappeared after Bonferroni adjustment. There was also no significant difference in the intensity of services related to medical treatment (i.e., services associated with hospital visits, consultations, house calls, hospitalizations, and hospital discharges).

Table 2.

The associations between treatment status at start of outreach service and each service intensity outcome (number of services per month) (n = 89).a

| People who were not receiving medical treatment (n = 37) | People who were receiving medical treatment (n = 52) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Coefficient | 95% CI | p‐value | Adjusted p‐valueb | ||

| Service locations | |||||||||

| Telephone | 4.2 | 3.6 | 5.5 | 6.4 | −0.252 | −0.451 | −0.057 | 0.012 | 0.301 |

| Service at the health center | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.621 | −0.050 | 1.306 | 0.070 | >0.999 |

| Service outside of the health center (e.g., users' home) | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 0.195 | −0.065 | 0.454 | 0.140 | >0.999 |

| Service targets or recipients | |||||||||

| Service users themselves | 4.0 | 2.6 | 5.4 | 6.4 | −0.290 | −0.494 | −0.090 | 0.005 | 0.122 |

| Service users' family members | 1.8 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 0.707 | 0.334 | 1.087 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Related organizations | 1.5 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 0.137 | −0.227 | 0.497 | 0.458 | >0.999 |

| Absence | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.473 | −3.522 | 11.802 | 0.564 | >0.999 |

| Service types related to medical treatment | |||||||||

| Hospital visits | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.141 | −0.774 | 1.033 | 0.755 | >0.999 |

| Consultations | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.227 | −0.742 | 1.190 | 0.640 | >0.999 |

| House calls | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.329 | −1.477 | 2.116 | 0.704 | >0.999 |

| Hospitalizations | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.075 | −0.642 | 0.768 | 0.834 | >0.999 |

| Hospital discharges | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.243 | −5.345 | 5.684 | 0.907 | >0.999 |

Poisson regression analyses were conducted for each outcome of service use to determine the associations between treatment conditions at start of outreach service and service intensity. All regression analyses were adjusted for sex, age, and schizophrenia diagnosis.

We calculated Bonferroni‐adjusted p‐values considering the number of test.

Table 3.

The associations between treatment status at start of outreach service and each service intensity outcome (minutes of services per a month) (n = 89).a

| People who were not receiving medical treatment (n = 37) | People who were receiving medical treatment (n = 52) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Coefficient | 95% CI | p‐value | Adjusted p‐valueb | ||

| Service locations | |||||||||

| Telephone | 9.3 | 3.8 | 8.3 | 4.6 | 0.166 | −0.031 | 0.363 | 0.103 | >0.999 |

| Service at the health center | 40.8 | 23.2 | 31.8 | 21.2 | 0.478 | 0.052 | 0.903 | 0.031 | 0.768 |

| Service outside of the health center (e.g., users' home) | 54.3 | 21.8 | 53.3 | 22.6 | −0.050 | −0.373 | 0.273 | 0.763 | >0.999 |

| Service types | |||||||||

| Assistance with daily living tasks | 46.7 | 63.1 | 36.4 | 59.3 | 0.303 | −0.351 | 0.956 | 0.366 | >0.999 |

| Family support | 22.0 | 33.5 | 10.5 | 19.5 | 0.720 | 0.108 | 1.333 | 0.024 | 0.590 |

| Services for psychiatric symptoms | 91.0 | 97.8 | 68.0 | 63.1 | 0.073 | −0.447 | 0.593 | 0.784 | >0.999 |

| Services for physical health | 8.6 | 22.1 | 6.2 | 11.2 | −0.030 | −0.531 | 0.471 | 0.907 | >0.999 |

| Crisis services | 1.4 | 3.1 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 0.258 | −0.005 | 0.521 | 0.058 | >0.999 |

| Consultation on medical treatment | 4.5 | 6.8 | 5.9 | 10.0 | −0.138 | −0.575 | 0.299 | 0.537 | >0.999 |

| Services related to employment or commuting to school | 9.8 | 21.0 | 11.3 | 20.7 | −0.004 | −0.574 | 0.567 | 0.990 | >0.999 |

| Social services | 8.0 | 11.9 | 6.8 | 13.1 | 0.213 | −0.286 | 0.712 | 0.405 | >0.999 |

| Services related to interpersonal relationship | 26.0 | 26.8 | 26.2 | 33.1 | 0.238 | −0.376 | 0.851 | 0.450 | >0.999 |

| Information sharing | 3.1 | 3.9 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 0.026 | −0.287 | 0.338 | 0.873 | >0.999 |

To determine the associations between treatment conditions at start of outreach service and service intensity, linear regression analyses were conducted for each outcome of service use after adding 1 to each data and logarithmic transformation. All regression analyses were adjusted for sex, age, and schizophrenia diagnosis.

We calculated Bonferroni‐adjusted p‐values considering the number of test.

In the analysis using the minutes of services as the outcome, people with untreated mental health problems at the start of services (untreated group) received more hours of service at health centers than the treated group (b = 0.478, p = 0.031). Compared to the treated group, the untreated group received more intense family support (b = 0.720, p = 0.024). These significant differences, however, disappeared after Bonferroni adjustment. No significant differences were found in other outcomes.

Table 4 shows the frequencies of medical or social service use 12 months after the start of outreach services, stratified by treatment status at outreach service initiation. In the untreated group, 45% had received any medical or social services (hospitalization: 11%; outpatient: 35%; psychiatric day care or short care: 0%; social service: 3%). In the treated group, 89% had received any medical or social services (hospitalization: 12%; outpatient: 75%; psychiatric day care or short care: 15%; social service: 21%).

Table 4.

The frequencies of medical or social service use 12 months after the start of outreach services, stratified by treated status at outreach service initiation (n = 89).

| People who were not receiving medical treatment (n = 37) | People who were receiving medical treatment (n = 52) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Hospitalization | ||||

| Yes | 4 | 10.8 | 6 | 11.5 |

| No | 32 | 86.5 | 43 | 82.7 |

| Missing | 1 | 2.7 | 3 | 5.8 |

| Outpatient | ||||

| Yes | 13 | 35.1 | 39 | 75.0 |

| No | 24 | 64.9 | 10 | 19.2 |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 5.8 |

| Psychiatric day care or short care | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 15.4 |

| No | 37 | 100.0 | 41 | 78.8 |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 5.8 |

| Social service | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 2.7 | 11 | 21.2 |

| No | 36 | 97.3 | 38 | 73.1 |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 7.7 |

| Any medical or social servicesa | ||||

| Yes | 17 | 45.9 | 46 | 88.5 |

| No | 20 | 54.1 | 3 | 5.8 |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 5.8 |

Any medical or social services was “Yes,” if “Hospitalization,” “Outpatient,” “Psychiatric day care or short care,” or “Social service” was “Yes.”

DISCUSSION

This study investigated the association between treatment status (treated or not) at the start of outreach services and service intensity, using data from a community mental health outreach service in Japan. The findings suggest that family members in the untreated group were more likely to be targets or recipients of services than those in the treated group. Additionally, compared to previously treated people, those with untreated mental health problems received fewer services for service users themselves, and also fewer services by telephone; by contrast, they received more services at the health center and more services for family support, although these significant differences disappeared after Bonferroni adjustment.

Key findings of this study relate to family support. Nearly three quarters of study participants with untreated mental health issues were living with their families. Family members in the untreated group received more frequent services than those in the treated group. Also, family support was the only service type that differed significantly in terms of the number of minutes between the two groups. The untreated group received significantly more intense services for family support, although these significant differences disappeared after Bonferroni adjustment. There are three possible reasons why the outreach team spent more time on family support and family members were more likely to be targets or recipients of services in the untreated group than in the treated group. First, the family itself might need support. Untreated people often seek help from family members, 13 but they too might have untreated mental health problems. 14 In such cases, the outreach team plays a direct role in the care of family members. For example, the team accompanies family members to see their doctor or provides psychoeducation when they have psychological problems. Second, support might be provided through family members since users often do not want to receive services directly. Indeed, 70% of untreated people had been withdrawn at home for more than 6 months. Also, service users themselves were less likely to be targets or recipients of services in the untreated group than in the treated group, although this significant difference disappeared after Bonferroni adjustment. Given the difficulty in providing direct services to the users, the outreach team may instead provide services to their families. In fact, some staff members have practiced evidence‐based family support 28 and provided support not only to the service users themselves, but also to the family unit. Third, the untreated group was also significantly less likely than the treated group to have a history of psychiatric consultation and a diagnosis of mental illness. Untreated conditions might be caused by self‐stigma and lack of awareness of the need for support. 10 , 11 In these cases, it is important to involve the family in the support. A Japanese ACT study showed that family support contributed to improved outcomes in service users. 23 Outreach services involving family members may be especially needed to help people with untreated mental health problems, particularly in Japan.

This study also found that the service intensity with and without treatment varied by service location. People with untreated mental health problems received more hours of service at the health center and fewer services by telephone compared to those who were previously treated, although these significant differences disappeared after Bonferroni adjustment. The longer service time at the health center in the untreated group might be due to a larger number of services in which family members were targets or recipients in the untreated group compared to the treated group. The untreated group might have received more intense services at the health center instead of at home or by telephone in cases where the family members received services separately from the service users themselves.

This study showed no significant differences between the treated and untreated groups regarding service types other than family support (i.e., services for daily living tasks, psychiatric symptoms, physical health, crisis, consultation on medical treatment, employment or school attendance, social services, interpersonal relations, and information sharing). Possible reasons might be that individuals in both groups have serious problems in fulfilling social roles (e.g., employment, school attendance, sheltered workshop attendance, and housework) and in carrying out tasks necessary for community life (e.g., those related to nutrition, hygiene, money, safety, human relations, document management, and transportation). In other words, daily living needs for outreach services might have been common, regardless of treatment conditions.

The percentage of outpatients 12 months after the initiation of services in the untreated group was less than half that in the treated group in this study. According to guidance on community mental health services by the World Health Organization, however, community outreach service was preferred in connection with other community resources. 16 There are two possible explanations. Fewer people may have needed immediate medical treatment in the untreated group than in the treatment group. Each person in need of medical treatment, however, might have received more support related to utilizing or transitioning to other mental health services than people in the treatment group. On the other hand, for the other half of people not connected to other medical or social services, outreach teams may have played a primary support role, including providing specialized care. The study covered an average of 27 months of service data per person in both groups. The results suggest that cases may sometimes take more than 2 years before transitioning to other medical or social services. However, many outreach services conducted by the local government in Japan are only offered for a maximum of 6 months. 31 Such cases might require long‐term involvement by outreach teams. In summary, the community outreach team may have used two different practices depending on the target. More detailed research, including an analysis of support plans, is needed to clarify this issue.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the current study is that it examined the association between treatment status at the start of outreach services and service intensity, whereas most relevant research has focused on outcomes. Additionally, while outreach services in Japan are provided mainly by medical institutions or are targeted only to people with severe mental disorders, the data in this study were collected from an outreach team associated with the local government that targeted a wide variety of people, including those who were undiagnosed. In other words, this study evaluated pioneering efforts related to service provision in Japan. The findings will serve as a foundation for further research and will facilitate providing community support to the untreated.

This study has several limitations. First, the service data used in the analysis were incomplete. Sixty‐five percent of people in the untreated group and 81% of those in the treated group had no early service data available for analysis because they had received service prior to the introduction of electronic records. We addressed this issue by calculating monthly averages rather than the total number or hours of services provided. Second, this study used data from only one community mental health outreach team because in Japan there are few such teams other than ACTs. In addition, about half of the study participants had schizophrenia. This may be because most of the outreach users were referred by the Tokorozawa City Health Center. Outreach service content is inherently influenced by the medical and social resources of each community, which limits the generalizability of the study results. Third, the sample size was small due to incomplete data and the use of data from only one community mental health outreach team, which may have resulted in inadequate statistical power. Fourth, “untreated” was defined as no treatment or treatment discontinuation among people with life problems caused by psychiatric symptoms. We were not able to examine service intensity for untreated people who did not have these problems. Fifth, other potential confounding factors may exist. For example, we did not consider the times of onset and durations of untreated conditions, or the reasons for not receiving treatment. The small sample size in this study precluded consideration of diagnoses other than schizophrenia. In addition, some service‐type outcomes may be correlated, but the influence of having received other services was not considered. Therefore, it was not possible to determine the direct effects of being untreated or the mechanisms that influence service intensity. Sixth, we could not consider changes in support over time. Seventy percent of the people in the untreated group were withdrawn, and in these cases the support targets may have been other people (e.g., their family members), especially until they built a relationship with the outreach team staff. To disseminate outreach services to people who have untreated mental health problems in Japan, further quantitative research involving the analysis of serial data, interviews with the outreach team, and examination of typical cases is needed to clarify the details of such services.

CONCLUSION

This study found that family members were more likely to be targets or recipients of services in the untreated group than in the treated group. Compared to previously treated people, those with untreated mental health problems received fewer services themselves, and also fewer services by telephone; by contrast, they received more services at the health center and for family support. Further research, however, is needed to describe services in more detail, such as changes in their content over time.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION STATEMENT

Mai Iwanaga was primarily responsible for the study design, and also conducted the statistical analysis and wrote the draft of the manuscript. Sosei Yamaguchi critically revised the manuscript. Sosei Yamaguchi, Sayaka Sato, Kiyoaki Nakanishi, Erisa Nishiuchi, Michiyo Shimodaira, Yugan So, Kaori Usui, and Chiyo Fujii managed and organized the data collection. All authors contributed to the study design and interpretation of the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

ETHICS APPROVAL STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry [No. A2020‐081].

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

Prior to initiating the study, we created an official webpage informing participants about the intended use of service record data related to their background characteristics and to services provided. In addition, the opportunity to refuse participation was guaranteed.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

N/A

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Health and Labour Sciences Research Grant: “Development of implementation methods and systems for early intervention of mental health services in individual communities” (No. 19GC1015) (Takahiro Nemoto) and “Development of a mental health service system for comprehensive case management in psychiatric institutions” (No. 22GC0301) (Sosei Yamaguchi).

Iwanaga M, Yamaguchi S, Sato S, Nakanishi K, Nishiuchi E, Shimodaira M, et al. Service intensity of community mental health outreach among people with untreated mental health problems in Japan: A retrospective cohort study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci Rep. 2023;2:e138. 10.1002/pcn5.138

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Not all data are freely accessible because no informed consent was given by the participating agencies for open data sharing. However, the data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, following approval by the Research Ethics Committee at the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry.

REFERENCES

- 1. Scott KM, Jonge P, Stein DJ, Kessler RC. Mental disorders around the world: Facts and figures from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Borges G, Aguilar‐Gaxiola S, Andrade L, Benjet C, Cia A, Kessler RC, et al. Twelve‐month mental health service use in six countries of the Americas: a regional report from the World Mental Health Surveys. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;29:e53. 10.1017/S2045796019000477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Husky MM, Olfson M, He J, Nock MK, Swanson SA, Merikangas KR. Twelve‐month suicidal symptoms and use of services among adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:989–996. 10.1176/appi.ps.201200058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kido Y, Kawakami N. Sociodemographic determinants of attitudinal barriers in the use of mental health services in Japan: findings from the World Mental Health Japan Survey 2002‐2006. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;67:101–109. 10.1111/pcn.12008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Henriksen CA, Stein MB, Afifi TO, Enns MW, Lix LM, Sareen J. Identifying factors that predict longitudinal outcomes of untreated common mental disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66:163–170. 10.1176/appi.ps.201300564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boonstra N, Klaassen R, Sytema S, Marshall M, De Haan L, Wunderink L, et al. Duration of untreated psychosis and negative symptoms‐‐a systematic review and meta‐analysis of individual patient data. Schizophrenia Research. 2012;142:12–19. 10.1016/j.schres.2012.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Penttilä M, Jääskeläinen E, Hirvonen N, Isohanni M, Miettunen J. Duration of untreated psychosis as predictor of long‐term outcome in schizophrenia: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:88–94. 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.127753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Díaz‐Caneja CM, Pina‐Camacho L, Rodríguez‐Quiroga A, Fraguas D, Parellada M, Arango C. Predictors of outcome in early‐onset psychosis: a systematic review. NPJ Schizophr. 2015;1:14005. 10.1038/npjschz.2014.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kane JM, Kishimoto T, Correll CU. Non‐adherence to medication in patients with psychotic disorders: epidemiology, contributing factors and management strategies. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(3):216–226. 10.1002/wps.20060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tomczyk S, Schmidt S, Muehlan H, Stolzenburg S, Schomerus G. A prospective study on structural and attitudinal barriers to professional help‐seeking for currently untreated mental health problems in the community. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2020;47(1):54–69. 10.1007/s11414-019-09662-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stolzenburg S, Freitag S, Schmidt S, Schomerus G. Associations between causal attributions and personal stigmatizing attitudes in untreated persons with current mental health problems. Psychiatry Res. 2018;260:24–29. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stolzenburg S, Freitag S, Evans‐Lacko S, Speerforck S, Schmidt S, Schomerus G. Individuals with currently untreated mental illness: causal beliefs and readiness to seek help. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;28:446–457. 10.1017/s2045796017000828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tomczyk S, Schomerus G, Stolzenburg S, Muehlan H, Schmidt S. Who is seeking whom? A person‐centred approach to help‐seeking in adults with currently untreated mental health problems via latent class analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(8):773–783. 10.1007/s00127-018-1537-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Villatoro AP, Aneshensel CS. Family influences on the use of mental health services among African Americans. J Health Soc Behav. 2014;55:161–180. 10.1177/0022146514533348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Prokofyeva E, Martins SS, Younès N, Surkan PJ, Melchior M. The role of family history in mental health service utilization for major depression. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(2):461–466. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organization . Guidance on community mental health services: promoting person‐centred and rights‐based approaches. 2021. [cited 2022 Dec 19]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025707

- 17. Henderson P, Fisher NR, Ball J, Sellwood W. Mental health practitioner experiences of engaging with service users in community mental health settings: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative evidence. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2020;27(6):807–820. 10.1111/jpm.12628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vijverberg R, Ferdinand R, Beekman A, van Meijel B. The effect of youth assertive community treatment: a systematic PRISMA review. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):284. 10.1186/s12888-017-1446-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dieterich M, Irving CB, Bergman H, Khokhar MA, Park B, Marshall M. Intensive case management for severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;1(1):Cd007906. 10.1002/14651858.CD007906.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Savaglio M, O'Donnell R, Hatzikiriakidis K, Vicary D, Skouteris H. The impact of community mental health programs for Australian youth: a systematic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2022;25:573–590. 10.1007/s10567-022-00384-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen S, Barnett PG, Sempel JM, Timko C. Outcomes and costs of matching the intensity of dual‐diagnosis treatment to patients' symptom severity. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;31:95–105. 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. OECD . A new benchmark for mental health system: tackling the social and economic costs of mental ill‐health. 2021. [cited 2022 Dec 19]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/health/a-new-benchmark-for-mental-health-systems-4ed890f6-en.htm

- 23. Sono T, Oshima I, Ito J, Nishio M, Suzuki Y, Horiuchi K, et al. Family support in assertive community treatment: an analysis of client outcomes. Community Ment Health J. 2012;48:463–470. 10.1007/s10597-011-9444-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kido Y, Kawakami N, Kayama M. Comparison of hospital admission rates for psychiatric patients cared for by multidisciplinary outreach teams with and without peer specialist: a retrospective cohort study of Japanese Outreach Model Project 2011‐2014. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019090. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nishio M, Ito J, Oshima I, Suzuki Y, Horiuchi K, Sono T, et al. Preliminary outcome study on assertive community treatment in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;66:383–389. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2012.02348.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kayama M, Kido Y, Setoya N, Tsunoda A, Matsunaga A, Kikkawa T, et al. Community outreach for patients who have difficulties in maintaining contact with mental health services: longitudinal retrospective study of the Japanese outreach model project. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:311. 10.1186/s12888-014-0311-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tsunoda A, Kido Y, Kayama M. Japanese outreach model project for patients who have difficulty maintaining contact with mental health services: comparison of care between higher‐functioning and lower‐functioning groups. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2018;15:181–191. 10.1111/jjns.12183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fadden G, Heelis R. The Meriden Family Programme: lessons learned over 10 years. J Ment Health. 2011;20:79–88. 10.3109/09638237.2010.492413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJJ, Sawyer AT, Fang A. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: a review of meta‐analyses. Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36:427–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Warner R. Recovery from schizophrenia and the recovery model. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22:374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. WHO MiNDbank: More Inclusiveness Needed in Disability and Development . Plan for developing outreach services in mental health. 2011. [cited 2023 Jul 12]. Available from: https://extranet.who.int/mindbank/item/767

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not all data are freely accessible because no informed consent was given by the participating agencies for open data sharing. However, the data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, following approval by the Research Ethics Committee at the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry.