Abstract

Short peptides derived from intracellular proteins and presented on MHC class I molecules on the cell surface serve as a showcase for the immune system to detect pathogenic or malignant alterations inside the cell, and the sequencing and analysis of the presented peptide pool has received considerable attention over the last two decades. In this review, we give a comprehensive presentation of the methods employed for the large-scale qualitative and quantitative analysis of the MHC class I ligandome. Furthermore, we focus on insights gained into the underlying processing pathway, especially involving the roles of the proteasome, the TAP complex, and the peptide specificities and motifs of MHC molecules. The identification of post-translational modifications in MHC ligands and their implications for processing are also considered. Finally, we review the correlations of the ligandome to the proteome and the transcriptome.

Keywords: Major histocompatibility complex, HLA ligandome, Mass spectrometry, Peptide motifs, Post-translational modifications, Proteasome, Transporter associated with antigen processing

Introduction

Approximately 500,000 major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules are expressed on almost all nucleated cells in mammals [1, 2], although expression levels may vary considerably depending on tissue distribution and cell condition. All of these glycoproteins share a common invariant β2 microglobulin chain and a highly polymorphic heavy chain and display a short peptide, usually between eight and 11 amino acids long, in a binding groove. The MHC ligandome of a cell, i.e., the presented peptides in their entirety, consists of more than 10,000 different molecules and is thus highly complex. Presenting self and foreign peptides to T cells, MHC molecules act as the structural basis for the cellular immune response. Generally, MHC class I molecules interact with CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (CTL), whereas MHC class II molecules, expressed on professional antigen-presenting cells (APC), activate upon successful recognition CD4+ helper T cells (Th). The main source of MHC class I ligands are the substrates of proteasomal degradation that takes place in the cytosol as well as the nucleus [3], involving proteins from all intracellular compartments. Prior to presenting a ligand on the cell surface, however, the MHC class I molecule and its ligand have to complete intricate processing steps and meet in the loading process in the endoplasmatic reticulum (ER), where they interact with specialized proteins, including the chaperones calreticulin, ERp57, tapasin, and the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP). The role of all these proteins is to ascertain that immature MHC class I molecules become associated with a stabilizing peptide. The binding groove of the MHC molecule then determines the repertoire of presented peptides mainly through interactions with their anchor residues. Since the advent of large-scale MHC ligandome analysis allowing for the identification of thousands of MHC ligands, valuable insights have been gained into this crucial intracellular pathway and its machinery. We will review here the methodical background of ligandome analysis and the influence it has had on the understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

Qualitative and quantitative analysis of the ligandome: classical and modern methods

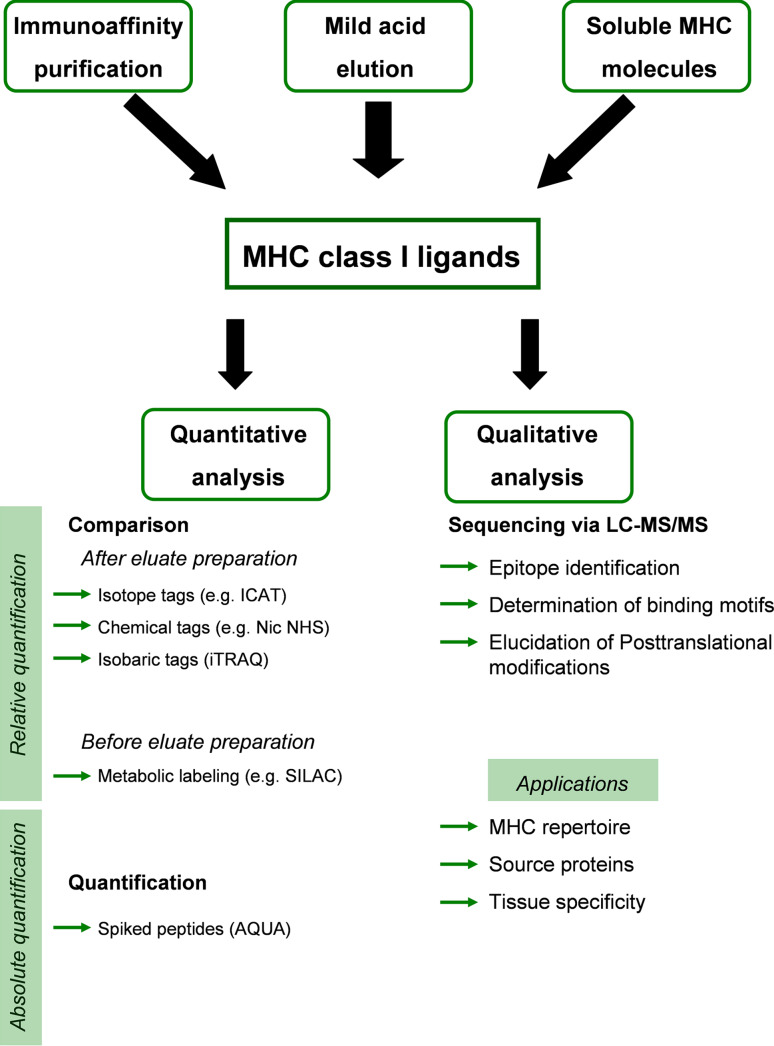

Numerous strategies for qualitative and quantitative analysis of MHC class I presented peptides have been described in the past 20 years (Fig. 1). One of the early methods for identifying natural MHC ligands has been the elution of peptides from the surface of viable cells by mild acid [4]. The considerable advantage of this technique is that it allows for the repeated elution of ligands from the very same cells and thus increases the available sample size. However, the method suffers from the high amount of contaminating peptides that are also present in the elution supernatants and do not originate from MHC molecules. One study employing β2m-reconstituted Fen cells treated with interferon α reported that only 40% of peptides sequences identified corresponded to specific MHC class I ligands [5].

Fig. 1.

Flowchart illustrating the different approaches for large-scale analysis of MHC class I ligands. The purified ligands can then be further analyzed quantitatively or qualitatively. The qualitative evaluation of MHC class I ligands is nowadays almost exclusively done via LC-MS/MS. The spectra obtained from the mass spectrometer data can reveal epitopes, binding motifs, and post-translational modifications of the peptides. The quantitative analysis can be performed either by comparing the relative mass changes of a labeled control peptide with the corresponding natural ligand, or by spiking of labeled peptides into the sample for an absolute quantification

In the more targeted immunoaffinity purification approach [6], cells are treated with non-denaturing detergents, like the zwitter-ionic CHAPS or the non-ionic NP-40, and MHC molecules are precipitated by applying the lysate to an affinity column to which a monoclonal antibody specific for a certain MHC class or allotype has been coupled. Ligands are then eluted with strong acid (e.g., trifluoroacetic acid) and separated from proteins according to size. While the composition of the peptide mixture thus becomes considerably more specific, the detergent used for lysis constitutes another source of contamination. CHAPS has a defined molecular weight of 614 Da, but NP-40 consists of heterogenous compounds with different molecular weights and is therefore not compatible with analysis by mass spectrometry. Novel acid-labile anionic surfactants (ALS) are rapidly degraded at low pH conditions and are therefore more suitable for subsequent mass spectrometric analysis [7]. The use of serial affinity columns with different MHC-specific antibodies allows for the separation of ligands from different MHC classes or allotypes and renders this approach far more versatile than the mild acid elution formerly described. This is essential for the detailed analysis of primary tissue samples displaying a complete set of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules. Nevertheless, the peptide repertoire might be influenced by the antibody used due to conformational shifts altering the binding affinities [8, 9], and the supply of MHC ligands from each sample is limited to the amount present at the time of lysis.

A further method for large-scale analysis of MHC ligands involves the use of soluble MHC molecules [10]. This approach is based on the transfection of cells with MHC molecules lacking the transmembrane domain. Assembled MHC–peptide complexes are secreted into the culture medium and can easily be purified by immunoprecipitation. Despite the fact that amounts of ligands in the milligram range can thus be obtained, one should keep in mind that using recombinant technologies might change the quality of purified MHC ligands and that ligands of the transfected allele are bound to be presented in unphysiologically high amounts, thus distorting profoundly the spectrum of the ligandome [11]. Obviously, this method is also not applicable to the analysis of HLA ligands from primary tissue or cell line samples. Keeping this in mind, immunoaffinity chromatography of natural MHC is the method of choice when analyzing primary samples, such as biopsies from cancer patients [12].

The sequencing of MHC ligands has mainly been performed by two methods, namely Edman degradation [13] and mass spectrometry (MS). While Edman degradation is a time-consuming method of rather low sensitivity but high accuracy, the use of mass spectrometry marked a technical breakthrough in high-throughput identification of MHC ligands [14]. For the generation of detectable ions from proteins and peptides, the most suitable strategies are electrospray ionization (ESI) and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI). Both techniques can be applied in combination with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) systems, but ESI enables the direct online injection of the fractionated peptides and is therefore simpler and quicker. The use of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)–ESI–tandem MS (MS/MS) is nowadays the state-of-the-art technology by enabling the fast identification of several hundreds of MHC ligands in one experimental approach [14, 15]. In this setup, a complex sample is first separated by HPLC, and the eluted analytes are then directly subjected to soft ionization by an ESI device, followed by fragmentation in a collision chamber by collision-induced dissociation (CID) and a subsequent recording with regard to their m/z ratio and intensity. The obtained fragmentation spectra are characteristic for the peptide sequences and can be analyzed by manual interpretation in combination with algorithms (MASCOT, BLAST) and sequence databases [16]. Modern instruments and software are capable of fully automated analysis.

Despite the fact that hundreds of ligands can be identified with this technique, there are nevertheless limitations due to differences in the abundance of peptides regarding the total MHC ligandome. Low-abundant ligands are hardly observed as a consequence of the overriding detection of higher concentrated molecules and the detection limits of the instrument. To identify epitopes from low-abundant proteins, like e.g., viral proteins, the predict-calibrate-detect strategy is an important MS-based technique. With this strategy, one can screen a protein of choice for MHC ligands by first predicting epitope candidates (e.g., using the database SYFPEITHI at http://www.syfpeithi.de), then synthesizing calibrant peptides and measuring their retention times in the HPLC system. This enables the assignment of sequences to signals from the analyte with identical retention times and m/z ratios, even if sequencing by fragmentation is not feasible [17, 18].

While being a powerful method to identify large numbers of MHC ligands, simple mass spectrometric analysis does have the drawback of being an only qualitative rather than quantitative method. No information on the frequency of analyzed ions can be gained from peak intensities alone. However, several techniques have been established that allow for an absolute or relative quantification of signals detected in MS. This is crucial for comparing the ligandome of different tissues, different individuals, or healthy tissue with samples from tumors or inflammation sites, and a prerequisite for applying information about ligandomes to diagnostics or immunotherapy.

Generally, peptide quantification in MS is achieved by differential labeling of peptides from two or more samples and analysis in the same LC/MS run. If the chemical properties of differentially labeled peptide pairs are highly similar after labeling, signal intensities in this case will be a measure of abundance. Labeling can be performed at several stages during ligand purification and in many different ways. A classical example is the introduction of isotope-coded affinity tags (ICAT) to cystein residues [19]. Here, isolated peptides and controls are modified with the heavy or the light ICAT reagent, respectively, and analyzed with MS. A disadvantage of this method is that the large ICAT tag influences fragmentation spectra, complicating peptide identification, and only cysteine-containing peptides are modified and analyzed.

Reactive substances for the N-termini of peptides circumvent this problem by introducing exactly one tag into each peptide. Numerous reagents have been applied, such as phenyl isocyanates [20], O-methylisourea [21], acetylation [22], or nicotinoyloxy succinimide (Nic-NHS) in mass-coded abundance tagging (MCAT) [22–24]. Nicotinylation has the advantage of high sensitivity in the final identification due to the fact that the modification maintains and strengthens the charge state of the peptides. Classically, this approach starts with guanidylation of lysine side chains to ensure the selectivity of the reaction. After desalting, one sample is treated with the light isoform 1H4-N-nicotinoyloxy succinimide (1H4-Nic), and the other sample is incubated with the deuterated heavy isoform 2D4-Nic [22]. Equimolar mixing of the heavy and light labeled peptide pools enables the detection of co-eluting peptide pairs in an LC-MS run. Due to the four hydrogen atoms in the tag, the signals are separated by 4 Da on the m/z scale. By calculating the ratio of the intensities of the peak pairs, the relative expression of HLA ligands in both samples can then be determined.

An alternative method to isotope labels and determining mass differences is the isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) system [25], which employs isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification. Peptides from different sources are not distinguished by a mass shift but rather by specific reporter ions in the fragmentation spectra. It adds an innovative concept to the MCAT chemistry mentioned previously, and there are up to eight different MS/MS reporter ions available to quantify protein expression [26] in one single analysis, increasing analytical throughput.

Another fascinating method for labeling depends on metabolic incorporation of stable isotopes rather than on chemical modification, also called stable isotope labeling in cell culture (SILAC) [27]. In this approach, amino acids bearing stable isotopes are introduced into the growth media of living cells and are then incorporated into newly synthesized polypeptides. Commonly, arginine and lysine are chosen for labeling, and up to three different weight isomers can be applied. A major advantage of this method lies in the fact that the labeling is already present before sample preparation, allowing for early mixing of samples and the exclusion of errors due to differences in handling. It is excellently applicable to tryptic digests, where resulting peptides canonically contain exactly one basic residue at the C terminus, but not so well suited for the analysis of MHC ligands that can contain several labeled amino acids giving rise to different mass shifts, or none at all, preventing comparison. Neither is the method applicable to the analysis of primary patient tissue, since labeling cannot be performed in humans.

It should be noted that all of the strategies mentioned above allow only for the relative quantification of samples among each other, and not for the determination of absolute peptide levels. This can be achieved in some cases, however, by combining differential isotope labeling with the predict-calibrate-detect system, resulting in the absolute quantification approach (AQUA) [28, 29]. Here, known amounts of synthetic peptides that have been labeled are spiked into the mixture before it is analyzed. The amount, and accordingly the copy numbers of the sample peptide, can then be calculated from the absolute amounts of AQUA peptide added. Since calibrants need to be identified and synthesized, this method is in fact considerably targeted but also limited to a small number of peptides, which prevents large-scale quantification analysis, and can only be applied to MHC ligands of known identity.

Apart from the large variety of labeling approaches, efforts have been made to establish label-free methods for quantification. The application of any labeling method will run the risk of losing low-abundant molecules from the sample due to the labeling process, or else incur the considerable costs of SILAC labeling. Additionally, labeling is constricted by the limited set of different weight forms available, which requires that in comparisons of large sample numbers one or more samples be used as cross-references in several measurements. The underlying principle is to achieve a normalization of peptide concentrations by correlating the integrated total ion count with the previously determined total peptide amount [22]. However, different samples need to be analyzed sequentially, preventing high-throughput analyses and posing problems for the normalization.

MHC class I processing: what do the ligands tell us?

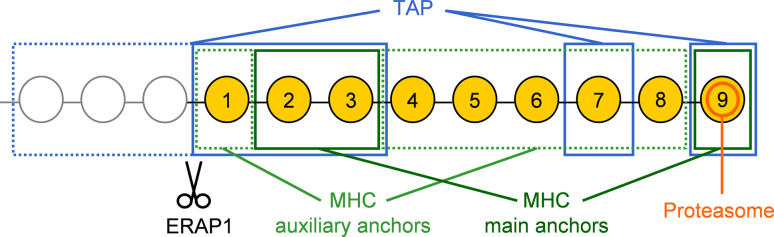

MHC class I peptides are usually generated in a complex process involving steps in the cytosol, translocation of intermediates into the ER, and final trimming of future ligands there. The specificities of several proteins involved in the process are amenable to MHC ligandome analysis (Fig. 2). Generally, ligands are derived from products of the proteasome, the main enzyme of protein degradation in the cytosol (reviewed in detail by Sijts and Kloetzel in this issue). The complete 26S proteasome is made up of a 19S regulator and the 20S proteolytic subunit, which itself consists of four heteroheptameric rings (two rings of 7 α and two of 7 β subunits each) [30]. The proteolytic activity is conveyed by three of the β subunits, each possessing a unique cleavage specificity: β1 cleaves after acidic residues (caspase-like activity), β2 after basic residues (trypsin-like activity), and β5 after hydrophobic residues (chymotrypsin-like activity) [31]. It is well established that the C-terminus of MHC ligands is determined by the proteasome [32] (Fig. 2), and ligandome analysis has confirmed that all MHC peptide motifs are compatible with the proteasomal cleavage specificities. While no motifs of human MHC allotypes are known that would allow for acidic residues at the C-terminus, either hydrophobic or basic residues are required by all allotypes. Furthermore, so-called immunoproteasomes with a different subunit composition are formed under the influence of interferon γ (IFNγ) or tumor necrosis factor (TNF) [33]. The three catalytic subunits are replaced by LMP2, MECL1, and LMP7, respectively. Numerous studies have shown that immunoproteasomes enable the presentation of ligands poorly produced by proteasomes [34], and their cleavage specificity is altered to enhance the chymotryptic activity while virtually abrogating the caspase-like activity [35]. Hence pro-inflammatory conditions lead to the production of peptide precursors with even more suitable C-terminal residues.

Fig. 2.

Amino acid positions of relevance in peptide motifs that are accessible by the analysis of the HLA ligandome, using nonamers as example. The C-terminus of ligands results from proteasomal cleavage. Positions of main and auxiliary binding anchors for MHC molecules differ among allotypes, main anchors being most frequently positions 2 and 9. TAP can transport longer peptides than suitable for MHC binding, in which case ERAP1 cleaves surplus N-terminal amino acids. Residues relevant for TAP binding are the three N-terminal amino acids of the transported peptide as well as the antepenultimate and the C-terminal ones

Nonetheless, proteasomal products mostly range in size from 2–25 amino acids [36, 37], and the majority do not have the correct length for MHC binding. Longer peptides can be digested at the N-terminus by various cytosolic proteases, like LAP [38], PSA, BLMH [39], or TPPII [40], before being transported to the ER by the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) complex (reviewed by van Endert in this issue). This is a heterodimer consisting of TAP1 and TAP2 that actively translocates peptides into the ER and has a length preference of 8–13 amino acids, although peptides of up to 40 residues can be transported with low efficiency [41, 42]. TAP has a strong preference for hydrophobic or basic residues at the C-terminal position, reflecting the cleavage specificity of proteasomes and especially immunoproteasomes, and hydrophobic residues in position 2 and 3, while proline and acidic residues in the first three positions are strongly detrimental for transport [43].

Final MHC class I assembly and peptide binding occurs in the peptide loading complex (PLC) in the ER. Tapasin and several other ER-resident chaperones are crucial for this process. Tapasin binds TAP and is then linked to a cysteine residue at the active site of the thiol oxidoreductase ERp57 [44, 45]. This heterodimer then recruits MHC class I molecules and calreticulin to the PLC [46] that receives the peptides translocated by TAP and mediates MHC loading. The final truncation of the peptides is performed by endoplasmatic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 (ERAP1) [47] (reviewed by van Endert in this issue).

An alternate pathway for the processing of MHC class I peptides was analyzed by MS-based experiments of peptides presented by TAP-deficient cells. Signal sequence-derived peptides can circumvent the TAP defect by entering the ER during co-translational protein translocation by the signal peptidase complex (SPase complex) [48, 49]. The majority of the TAP-independent ligands first described were restricted to HLA-A*02. Recently, it has first been shown that an MHC molecule other than HLA-A*02:01, namely B*51:01, preferentially binds signal peptide-derived ligands in TAP-deficient cells [50] and hence signal sequence-derived peptides are not restricted to presentation by a specific HLA allotype. Additionally, peptides derived from mature protein chains were characterized that may have been generated partially by the proteasome.

The TAP-independent MHC ligandome is of special interest because many viruses and tumors specifically inhibit TAP function to evade detection by the immune system. Furthermore, there are MHC class I ligands that are poor TAP substrates and therefore might require other pathways for gaining access to their MHC molecules [43, 51–53].

The MHC peptide motifs: structural keystones of cellular immunity

In addition to being polygenic, HLA genes are also the most polymorphic genes known. For MHC class I complexes, this diversity is entirely due to the different heavy chains that associate with the invariant β2 microglobulin. Nearly 3,400 class I alleles are presently known (1,001 for HLA-A, 1,605 for HLA-B, and 690 for HLA-C; http://www.ebi.ac.uk/imgt/hla/stats.html, April 2010), and the numbers are increasing steadily. Since each heavy chain isoform possesses an allele-specific peptide motif, the combination of polygenicity and polymorphism ensures that each individual will be able to present a broad range of peptides, and—even more importantly—populations will consist of individuals presenting different peptide spectra. Thus it is impossible for pathogens to acquire specific mutations protecting them against immune recognition in all individuals of a population. While this staggering diversity bears testimony to the immunological arms race between the immune system and its pathogenic foes, it also presents a challenge to immunotherapeutic approaches based on HLA class I ligands.

When the polymorphism of HLA molecules was first analyzed, antibodies were used to differentiate between allotypes, which were grouped into serotypes. The peptide-binding motifs of the most important serotypes were determined more than 15 years ago, with one human and three mouse allotypes defined in 1991 [54]. Edman degradation was employed in the beginning, mostly to determine general motifs out of peptide mixtures after reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP–HPLC) fractionation, although sometimes the sequencing of an individual ligand could be achieved. The inherent limitations of RP-HPLC in separation and Edman degradation in sensitivity could be overcome by the introduction of mass spectrometry (MS) into the field [14]. This constituted a major breakthrough that allowed for the large-scale sequencing of MHC ligands and the refinement of binding motifs. More than 10 years ago, our group established the SYFPEITHI database (http://www.syfpeithi.de) [55] containing published ligands and peptide motifs of a wide variety of MHC alleles. We assume that a confident motif can be extracted from about 50 confirmed ligands, and this number has now been reached for a large number of serotypes (Fig. 3), although there are still molecules lacking any reported ligands.

Fig. 3.

Number of reported ligands for each HLA allotype. Ligands from the SYFPEITHI database and unpublished data of our group were considered. Allotypes with more than 50 ligands, for which confident peptide motifs can be derived, are highlighted

Generally, MHC class I molecules possess six binding pockets (named A–F) in their peptide-binding groove, which are highly polymorphic in size, shape, and electrochemical properties. The most important of these are the pockets binding the main anchor residues [54, 56], which basically define the binding motif [57]. Very often these are located at position 2 and the C-terminus of the peptide, although exceptions at position 3 in HLA-A*01 [58] or position 5 in HLA-B*08, H2-Kb, and -Db [54] appear in important allotypes as well. Additionally, secondary anchors [59] can stabilize the MHC-peptide binding and also influence the specificity of the allele (Fig. 2).

Sequence differences between MHC allotypes that are serologically indistinguishable have been discovered very early [60], but the sequencing of HLA class I subtypes began in earnest with the introduction of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to the field [61]. Soon, a huge variety of alleles had been identified, and it appeared highly desirable to group them into clusters according to common properties. The serological distinctions supplied an obvious guideline, but significant differences in the binding motifs were discovered even between subtypes of the same serotype, e.g., for HLA-A*02 [62, 63]. Especially with a view to the possible simplification of immunotherapeutic approaches, the suggestion has been made to group HLA molecules into supertypes according to similar binding specificities [64]. This supertype system was revised and updated by the same group a few years ago [65]. In addition to the sequencing of natural ligands and peptide-binding assays, the majority of binding motifs were predicted by the comparison of the amino acids thought to account for the specificity of two binding pockets, B and F. These are imputed to bind the main anchor residues at position 2 and the C-terminus of the ligand, respectively.

The pivotal point of the HLA supertype model consists in the suggestion that peptides known to be presented on one member of a supertype should very probably be ligands on other members as well, thus enabling single antigenic epitopes to elicit immune responses in a large part of an HLA-polymorphic population. We have subjected this model to extensive analysis concerning the putative HLA-B44 supertype [66], consisting of the alleles HLA-B*18, B*37, B*40, B*41, B*44, B*45, B*47, B*49, and B*50. A total of 670 natural ligands were eluted from HLA molecules after immunoprecipitation and sequenced by mass spectrometry, covering all nine alleles of the supertype. Of these 670 ligands, only 25 were presented by more than one HLA molecule, and none were presented by more than three members of the supertype. In contrast, when comparing different sources positive for HLA-B*18:01, pairwise overlaps of 51 and 80% were observed among the ligandomes. These results were confirmed by label-free data-dependent ion selection (DDIS) experiments with three different B-LCL cell lines, and also by the analysis of cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) epitopes that were found to be largely restricted to carriers of single specific alleles of the supertype. Thus, the extent of epitope overlap in the B44 supertype was found to be lower than 3%. Apart from different auxiliary anchors, the binding motifs also differ in the main anchor residues. For example, while all motifs require a negative charge in position 2, HLA-B*37 and B*47 prefer aspartic acid, while all other alleles bind exclusively glutamic acid. The anchor residues at the C-terminus also vary, ranging from small aliphatic residues in HLA-B*41 to large aromats in HLA-B*18.

While the overlap is thus very limited in the B44 supertype, preliminary results of ours concerning the A3 supertype hint at a possibly larger overlap between molecules of this group. For instance, HLA-A*11 and A*03 were found to share 24% of their ligands, but the overlap to other members of the group (A*31, A*66, A*68) has nevertheless been less than 10%. Accordingly, recent epidemiological studies have yielded ambiguous results concerning the association of HLA supertypes with immune responses. One group studying the cytokine profile of children after vaccination against rubella virus [67] has found correlations between the intensity of some types of cytokine releases and some HLA supertypes (A1, A2, and A3), while correlations between some supertypes and HIV control have also been reported [68]. However, another study analyzing the selection pressures imposed by HLA class I molecules on human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epitopes [69] has found no uniform effects of supertypes but rather substantially different evasive mutations favored by the presence of each allele.

These results appear to point out that supertypes as defined largely by peptide-binding experiments may or may not be groups of molecules with actually similar ligandomes, since in vitro peptide binding does not guarantee for actual processing and presentation on the living cell. Even if the binding motifs of two molecules appear to be very similar, the peptides that are in fact found on them ex vivo can have a very scant overlap, and their immunological effects might be rather different. Large-scale MHC ligandome analysis is indispensable for providing insights into the preferentially processed and presented peptide spectra of HLA molecules. Thus, recent attempts to identify promiscuous MHC class I epitopes based mainly on binding constants of candidate peptides [70] might meet limited success on several putative supertypes.

Post-translational modifications

The vast majority of MHC class I ligands are canonical short peptides consisting of only between 8 and 10 amino acids [71]. Nevertheless, it has been known for a long time that some ligands can contain modified amino acids. An acetylated epitope from myelin basic protein was reported over 20 years ago [72]. In the meantime, a large number of different post-translational modifications (PTMs) have been identified for ligands of both MHC class I and class II [73]. For class I ligands, PTMs described up to now include O-linked glycosylation [74], acetylation [72], phosphorylation of serine or threonine [75], deamidation after deglycosylation [76], methylation [77], and cysteinylation [78]. Although in some cases such modified peptides have been identified by analyzing the specificities of T cell lines [72, 79], the standard method for sequencing has been mass spectrometric analysis after HPLC separation. Since peptides with PTMs constitute only a small fraction of the ligandome, the application of enrichment strategies for glycopeptides [80, 81] and phosphopeptides [82, 83] has greatly facilitated their isolation and identification.

The presence of PTMs in MHC ligands provides crucial insights into the antigen-presentation pathway. First of all, the modified amino acids obviously do not generally block the degradation, transport, and peptide-loading processes, since otherwise no such peptides could be presented. In some N-glycosylated proteins, the enzymatic deamidation of the glycan-bearing asparagine to aspartate is a necessary precondition for the presentation on MHC class I [76, 84, 85]. This reaction is catalyzed by the cytosolic enzyme peptide-N-glycanase, so the proteins have to be transported from the ER to the cytosol in their glycosylated form and there be deglycosylated prior to proteasomal degradation. In this process, an epitope with a novel primary sequence is created, and one study has shown that the presentation of the non-deamidated epitope is possible if glycosylation is defective [86]. Thus the glycosylation status can be rendered directly perceptible at the ligandome level.

Furthermore, certain PTMs can enhance the presentation of the peptides carrying them. For example, it has been shown that phosphopeptides with suboptimal secondary anchor residues can be presented on HLA-A*02 because of stabilizing effects of the phosphate moiety [87]. Analysis of crystal structures has revealed that a phosphate group in position 4 can compensate for weaker interactions in the binding pockets while being oriented towards the interface of interaction with the T cell receptor, and thus has been labeled a “phosphate surface anchor”. Phosphopeptides as MHC ligands are especially interesting since phosphorylation in most cases is not a constitutive modification, but is rather intricately regulated. The presence or absence of the PTM thus creates the possibility for the immune system to recognize changes in phosphorylation status caused by inflammation, infection, or oncogenesis. Until now, about 90% of phosphorylation sites in MHC class I ligands have consisted of serines, with the rest being made up of threonines [75, 87–89], which reflects the frequency of phosphorylation sites in the cell. In spite of the eminent role tyrosine phosphorylation plays in intracellular signal transduction, no peptides containing phosphotyrosines have been found as MHC ligands yet, and the search for them is an important and intriguing field that promises to yield crucial information for targeted immunotherapeutic approaches, since it has already been demonstrated that cytotoxic T cells can discriminate between phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated peptides in vivo [75, 88, 90]. Mostly these studies have been carried out on HLA-A*02, and the data are in good accord with the crystal structures [87] showing the phosphate moieties oriented towards the T cell receptor. Furthermore, large-scale mass spectrometric analysis of the phospholigandome of cell lines from melanoma and ovarian carcinoma [88] has revealed several phosphopeptides presented on cancer cell lines but not on the EBV-transformed lymphoblast line JY. These results were confirmed by our finding of a B*35-restricted phosphopeptide presented in a primary renal tumor, but not on the corresponding healthy tissue [89], demonstrating that phosphorylated ligands are presented in a tumor-specific manner. These findings highlight the important implications that the study of MHC ligands with PTMs has for immunotherapeutic approaches. In the case of a glycosylated MHC class II-restricted epitope derived from type II collagen, it has already been established that differences in the PTM of the peptide is a critical factor in pathogenesis [91]. In normal cartilage the ligand is O-glycosylated, while in arthritic patients the modification was partially missing, presumably triggering immune responses by self-reactive T cells.

Another fascinating aspect of phospholigandome analysis consists in the fact that several ligands have been found whose phosphorylation sites have hitherto been unknown [89] and in some cases are even the first sites described from the respective proteins. Thus the search for peptides with PTMs can reveal even more general insights into wider fields of cell biology.

Apart from chemical modification of single amino acids, another unique class of PTMs consists in the phenomenon of epitope splicing [92, 93]. In this process, discontinuous peptide segments are joined by transpeptidation in the proteasome, whereby intervening segments of up to 40 amino acids can be excised [94]. The resulting peptide is eventually displayed on MHC molecules. This process can even result in epitopes whose segments have been spliced in reverse order [95], hinting at the possibility that the process is flexibly regulated and might even produce epitopes spliced from different proteins. However, no spliced epitopes have hitherto been identified in large-scale ligandome analysis, and thus the biological relevance of the splicing process can not be fully assessed yet.

Degradome versus transcriptome

Since the MHC ligandome is the main “readout” by which cytotoxic T lymphocytes monitor the status of infection and cellular metabolism, it is a crucial requirement for immunotherapy to know the cellular sources of MHC ligands. A systemic analysis of the sources of B*18:01 restricted MHC class I ligands by sequencing over 200 peptides by MS identified proteins from almost all compartments of the cell [96], suggesting that class I presented peptides represent a general and exhaustive summary of the proteomic content of the cell. Other groups report that even cell-surface proteins and secreted proteins are equally efficient sources of antigenic peptides as cytosolic or nuclear proteins [97].

As most precursors of MHC ligands are produced by the proteasome, it should be expected that the ligandome will reflect the products of the cellular degradation scheme, the degradome. This notion suggests that ligands will primarily originate from two sources, namely on the one hand proteins with a short life cycle and rapid turnover, and on the other hand, from defective ribosomal products (DRiPs) [97, 98]. These are prematurely terminated or misfolded polypeptides that are dysfunctional and are slated for immediate proteasomal degradation (see also the review by Dolan et al. in this issue). In any case, the HLA ligandome will thus be more strongly correlated not so much with the existing cellular proteome, but rather with protein turnover, and hence also with the mRNA transcriptome.

Accordingly, a comparison of the turnover kinetics of MHC peptides and proteins by SILAC experiments using soluble MHC class I molecules revealed that only a limited correlation (about 6%) exists between the amount of presented MHC peptides and the relative amount of the proteins of origin in the same cell [99]. This supports the assumption that many of these MHC ligands emerged from fastly degrading proteins or DRiPs and therefore MHC-bound peptides represent rather the degradome than the proteome of the cells.

To investigate the relationships between the transcriptome and the HLA ligandome, our group quantitatively analyzed MHC ligand densities by large-scale ESI–LC–MS/MS and the corresponding levels of RNA in renal cell carcinomas and autologous normal kidney tissue, respectively [100]. We found no strict correlation between mRNA levels and the corresponding MHC class I ligandome (r = 0.32) after evaluating 273 peptide pairs, thus concluding that analyzing mRNA expression profiles leads to quite different interpretations than analyzing the MHC class I ligandome. In comparison, a more recent study has reported a moderate correlation between mRNA levels and MHC class I presentation (r = 0.63), evaluating only 47 peptide pairs in normal and neoplastic mouse thymocytes [101]. The authors propose that the class I repertoire is influenced by highly abundant mRNA transcripts and suggest that the stronger correlation in their analysis may be caused by the use of quantitative real-time PCR to estimate transcript levels rather than microarrays. Another study has recently evaluated published data of human MHC ligands with respect to the localization of the proteins of origin and their mRNA levels as available in gene-expression databases [102]. Published ligands originated mainly in intracellular proteins, as opposed to secreted or membrane proteins. Also, 41% of proteins with the 2.5% highest mRNA concentrations contained MHC ligands, compared to only 3.2% for the lowest concentrations. These data, however, do not take into account donor- and tissue-specific differences, which might play an important role.

These conflicting results show that the relationship of the mRNA transcriptome and the MHC ligandome is yet far from being elucidated. Immunotherapeutic approaches, e.g., against tumor cells, depend on reliable data about differences in the ligandome between healthy and diseased, so parameters that can easily be determined, like mRNA levels, are highly desirable. Nevertheless, it is not established yet altogether whether such readouts are in fact available, and which they are.

Conclusions

Although the MHC ligandome is no quantitative reflection of the protein content of cells, it is the level at which the immune system monitors alterations in cellular metabolism and possibly pathological processes and hence of paramount importance in immunotherapy. LC–MS/MS is today the method of choice for analyzing the MHC ligandome, and even though the huge complexity of peptide repertoires allows only the identification of a small fraction of presented peptides, substantial developments in MS instrumentation have occurred since the early days of the field, and are to be expected to continue to yield ever-increasing amounts of information from single experiments. Studies of post-translationally modified peptides that are usually low-abundant are bound to profit especially from progress in sensitivity. Advances in quantification methods could pave the road to large-scale comparative ligandome quantification, contributing largely to our knowledge of the complex relationships of the transcriptome, proteome, degradome, and ligandome of cells. Taken together, the analysis of the ligandome is an important ingredient for a comprehensive understanding of cellular processes leading to dysfunction and disease.

References

- 1.Rammensee HG, Falk K, Rötzschke O. Peptides naturally presented by MHC class I molecules. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:213–244. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.001241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevanović S, Schild H. Quantitative aspects of T cell activation—peptide generation and editing by MHC class I molecules. Semin Immunol. 1999;11(6):375–384. doi: 10.1006/smim.1999.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reits EA, Benham AM, Plougastel B, Neefjes J, Trowsdale J. Dynamics of proteasome distribution in living cells. EMBO J. 1997;16(20):6087–6094. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.20.6087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Storkus WJ, Zeh HJ, 3rd, Salter RD, Lotze MT. Identification of T-cell epitopes: rapid isolation of class I-presented peptides from viable cells by mild acid elution. J Immunother Emphasis Tumor Immunol. 1993;14(2):94–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torabi-Pour N, Nouri AM, Saffie R, Oliver RT. Comparative study between direct mild acid extraction and immunobead purification technique for isolation of HLA class I-associated peptides. Urol Int. 2002;68(1):38–43. doi: 10.1159/000048415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Bleek GM, Nathenson SG. Isolation of an endogenously processed immunodominant viral peptide from the class I H-2 Kb molecule. Nature. 1990;348(6298):213–216. doi: 10.1038/348213a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu YQ, Gilar M, Lee PJ, Bouvier ES, Gebler JC. Enzyme-friendly, mass spectrometry-compatible surfactant for in-solution enzymatic digestion of proteins. Anal Chem. 2003;75(21):6023–6028. doi: 10.1021/ac0346196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bluestone JA, Jameson S, Miller S, Dick R., 2nd Peptide-induced conformational changes in class I heavy chains alter major histocompatibility complex recognition. J Exp Med. 1992;176(6):1757–1761. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solheim JC, Carreno BM, Smith JD, Gorka J, Myers NB, Wen Z, Martinko JM, Lee DR, Hansen TH. Binding of peptides lacking consensus anchor residue alters H-2Ld serologic recognition. J Immunol. 1993;151(10):5387–5397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prilliman K, Lindsey M, Zuo Y, Jackson KW, Zhang Y, Hildebrand W. Large-scale production of class I bound peptides: assigning a signature to HLA-B*1501. Immunogenetics. 1997;45(6):379–385. doi: 10.1007/s002510050219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Purcell AW, Gorman JJ. The use of post-source decay in matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation mass spectrometry to delineate T cell determinants. J Immunol Methods. 2001;249(1–2):17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinschenk T, Gouttefangeas C, Schirle M, Obermayr F, Walter S, Schoor O, Kurek R, Loeser W, Bichler KH, Wernet D, Stevanović S, Rammensee HG. Integrated functional genomics approach for the design of patient-individual antitumor vaccines. Cancer Res. 2002;62(20):5818–5827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edman P. A method for the determination of amino acid sequence in peptides. Arch Biochem. 1949;22(3):475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunt DF, Henderson RA, Shabanowitz J, Sakaguchi K, Michel H, Sevilir N, Cox AL, Appella E, Engelhard VH. Characterization of peptides bound to the class I MHC molecule HLA-A2.1 by mass spectrometry. Science. 1992;255(5049):1261–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.1546328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aebersold R, Goodlett DR. Mass spectrometry in proteomics. Chem Rev. 2001;101(2):269–295. doi: 10.1021/cr990076h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pascolo S, Schirle M, Gückel B, Dumrese T, Stumm S, Kayser S, Moris A, Wallwiener D, Rammensee HG, Stevanović S. A MAGE-A1 HLA-A A*0201 epitope identified by mass spectrometry. Cancer Res. 2001;61(10):4072–4077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schirle M, Keilholz W, Weber B, Gouttefangeas C, Dumrese T, Becker HD, Stevanović S, Rammensee HG. Identification of tumor-associated MHC class I ligands by a novel T cell-independent approach. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30(8):2216–2225. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2000)30:8<2216::AID-IMMU2216>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gygi SP, Rist B, Gerber SA, Turecek F, Gelb MH, Aebersold R. Quantitative analysis of complex protein mixtures using isotope-coded affinity tags. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17(10):994–999. doi: 10.1038/13690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mason DE, Liebler DC. Quantitative analysis of modified proteins by LC–MS/MS of peptides labeled with phenyl isocyanate. J Proteome Res. 2003;2(3):265–272. doi: 10.1021/pr0255856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cagney G, Emili A. De novo peptide sequencing and quantitative profiling of complex protein mixtures using mass-coded abundance tagging. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20(2):163–170. doi: 10.1038/nbt0202-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemmel C, Weik S, Eberle U, Dengjel J, Kratt T, Becker HD, Rammensee HG, Stevanović S. Differential quantitative analysis of MHC ligands by mass spectrometry using stable isotope labeling. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22(4):450–454. doi: 10.1038/nbt947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Münchbach M, Quadroni M, Miotto G, James P. Quantitation and facilitated de novo sequencing of proteins by isotopic N-terminal labeling of peptides with a fragmentation-directing moiety. Anal Chem. 2000;72(17):4047–4057. doi: 10.1021/ac000265w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt A, Kellermann J, Lottspeich F. A novel strategy for quantitative proteomics using isotope-coded protein labels. Proteomics. 2005;5(1):4–15. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross PL, Huang YN, Marchese JN, Williamson B, Parker K, Hattan S, Khainovski N, Pillai S, Dey S, Daniels S, Purkayastha S, Juhasz P, Martein S, Bartlet-Jones M, He F, Jacobson A, Pappin DJ. Multiplexed protein quantitation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using amine-reactive isobaric tagging reagents. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3(12):1154–1169. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400129-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choe L, D’Ascenzo M, Relkin NR, Pappin D, Ross P, Williamson B, Guertin S, Pribil P, Lee KH. 8-plex quantitation of changes in cerebrospinal fluid protein expression in subjects undergoing intravenous immunoglobulin treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. Proteomics. 2007;7(20):3651–3660. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ong SE, Blagoev B, Kratchmarova I, Kristensen DB, Steen H, Pandey A, Mann M. Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture, SILAC, as a simple and accurate approach to expression proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1(5):376–386. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200025-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desiderio DM, Kai M. Preparation of stable isotope-incorporated peptide internal standards for field desorption mass spectrometry quantification of peptides in biologic tissue. Biomed Mass Spectrom. 1998;10(8):471–479. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200100806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerber SA, Rush J, Stemman O, Kirschner MW, Gygi SP. Absolute quantification of proteins and phosphoproteins from cell lysates by tandem MS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(12):6940–6945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832254100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finley D. Recognition and processing of ubiquitin-protein conjugates by the proteasome. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:477–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081507.101607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groettrup M, Kirk CJ, Basler M. Proteasomes in immune cells: more than peptide producers? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(1):73–78. doi: 10.1038/nri2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammer GE, Kanaseki T, Shastri N. The final touches make perfect the peptide-MHC class I repertoire. Immunity. 2007;26(4):397–406. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aki M, Shimbara N, Takashina M, Akiyama K, Kagawa S, Tamura T, Tanahashi N, Yoshimura T, Tanaka K, Ichihara A. Interferon-gamma induces different subunit organizations and functional diversity of proteasomes. J Biochem. 1994;115(2):257–269. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van den Eynde BJ, Morel S. Differential processing of class-I-restricted epitopes by the standard proteasome and the immunoproteasome. Curr Opin Immunol. 2001;13(2):147–153. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00197-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toes RE, Nussbaum AK, Degermann S, Schirle M, Emmerich NP, Kraft M, Laplace C, Zwinderman A, Dick TP, Müller J, Schönfisch B, Schmid C, Fehling HJ, Stevanović S, Rammensee HG, Schild H. Discrete cleavage motifs of constitutive and immunoproteasomes revealed by quantitative analysis of cleavage products. J Exp Med. 2001;194(1):1–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nussbaum AK, Dick TP, Keilholz W, Schirle M, Stevanović S, Dietz K, Heinemeyer W, Groll M, Wolf DH, Huber R, Rammensee HG, Schild H. Cleavage motifs of the yeast 20S proteasome beta subunits deduced from digests of enolase 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(21):12504–12509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kisselev AF, Akopian TN, Woo KM, Goldberg AL. The sizes of peptides generated from protein by mammalian 26 and 20 S proteasomes. Implications for understanding the degradative mechanism and antigen presentation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(6):3363–3371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beninga J, Rock KL, Goldberg AL. Interferon-gamma can stimulate post-proteasomal trimming of the N terminus of an antigenic peptide by inducing leucine aminopeptidase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(30):18734–18742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stoltze L, Schirle M, Schwarz G, Schröter C, Thompson MW, Hersh LB, Kalbacher H, Stevanović S, Rammensee HG, Schild H. Two new proteases in the MHC class I processing pathway. Nat Immunol. 2000;1(5):413–418. doi: 10.1038/80852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reits E, Neijssen J, Herberts C, Benckhuijsen W, Janssen L, Drijfhout JW, Neefjes J. A major role for TPPII in trimming proteasomal degradation products for MHC class I antigen presentation. Immunity. 2004;20(4):495–506. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Momburg F, Roelse J, Hämmerling GJ, Neefjes JJ. Peptide size selection by the major histocompatibility complex-encoded peptide transporter. J Exp Med. 1994;179(5):1613–1623. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koopmann JO, Post M, Neefjes JJ, Hämmerling GJ, Momburg F. Translocation of long peptides by transporters associated with antigen processing (TAP) Eur J Immunol. 1996;26(8):1720–1728. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Endert PM, Riganelli D, Greco G, Fleischhauer K, Sidney J, Sette A, Bach JF. The peptide-binding motif for the human transporter associated with antigen processing. J Exp Med. 1995;182(6):1883–1895. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dick TP, Bangia N, Peaper DR, Cresswell P. Disulfide bond isomerization and the assembly of MHC class I-peptide complexes. Immunity. 2002;16(1):87–98. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00263-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peaper DR, Wearsch PA, Cresswell P. Tapasin and ERp57 form a stable disulfide-linked dimer within the MHC class I peptide-loading complex. EMBO J. 2005;24(20):3613–3623. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wearsch PA, Cresswell P. Selective loading of high-affinity peptides onto major histocompatibility complex class I molecules by the tapasin-ERp57 heterodimer. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(8):873–881. doi: 10.1038/ni1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saric T, Chang SC, Hattori A, York IA, Markant S, Rock KL, Tsujimoto M, Goldberg AL. An IFN-gamma-induced aminopeptidase in the ER, ERAP1, trims precursors to MHC class I-presented peptides. Nat Immunol. 2002;3(12):1169–1176. doi: 10.1038/ni859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Henderson RA, Michel H, Sakaguchi K, Shabanowitz J, Appella E, Hunt DF, Engelhard VH. HLA-A2.1-associated peptides from a mutant cell line: a second pathway of antigen presentation. Science. 1992;255(5049):1264–1266. doi: 10.1126/science.1546329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wei ML, Cresswell P. HLA-A2 molecules in an antigen-processing mutant cell contain signal sequence-derived peptides. Nature. 1992;356(6368):443–446. doi: 10.1038/356443a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weinzierl AO, Rudolf D, Hillen N, Tenzer S, van Endert P, Schild H, Rammensee HG, Stevanović S. Features of TAP-independent MHC class I ligands revealed by quantitative mass spectrometry. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38(6):1503–1510. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neisig A, Roelse J, Sijts AJ, Ossendorp F, Feltkamp MC, Kast WM, Melief CJ, Neefjes JJ. Major differences in transporter associated with antigen presentation (TAP)-dependent translocation of MHC class I-presentable peptides and the effect of flanking sequences. J Immunol. 1995;154(3):1273–1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Daniel S, Brusic V, Caillat-Zucman S, Petrovsky N, Harrison L, Riganelli D, Sinigaglia F, Gallazzi F, Hammer J, van Endert PM. Relationship between peptide selectivities of human transporters associated with antigen processing and HLA class I molecules. J Immunol. 1998;161(2):617–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fruci D, Lauvau G, Saveanu L, Amicosante M, Butler RH, Polack A, Ginhoux F, Lemonnier F, Firat H, van Endert PM. Quantifying recruitment of cytosolic peptides for HLA class I presentation: impact of TAP transport. J Immunol. 2003;170(6):2977–2984. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Falk K, Rötzschke O, Stevanović S, Jung G, Rammensee HG. Allele-specific motifs revealed by sequencing of self-peptides eluted from MHC molecules. Nature. 1991;351(6324):290–296. doi: 10.1038/351290a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rammensee HG, Bachmann J, Emmerich NP, Bachor OA, Stevanović S. SYFPEITHI: database for MHC ligands and peptide motifs. Immunogenetics. 1999;50(3–4):213–219. doi: 10.1007/s002510050595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saper MA, Bjorkman PJ, Wiley DC. Refined structure of the human histocompatibility antigen HLA-A2 at 2.6 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1991;219(2):277–319. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90567-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rammensee HG, Friede T, Stevanović S. MHC ligands and peptide motifs: first listing. Immunogenetics. 1995;41(4):178–228. doi: 10.1007/BF00172063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.DiBrino M, Tsuchida T, Turner RV, Parker KC, Coligan JE, Biddison WE. HLA-A1 and HLA-A3 T cell epitopes derived from influenza virus proteins predicted from peptide binding motifs. J Immunol. 1993;151(11):5930–5935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ruppert J, Sidney J, Celis E, Kubo RT, Grey HM, Sette A. Prominent role of secondary anchor residues in peptide binding to HLA-A2.1 molecules. Cell. 1993;74(5):929–937. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90472-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cowan EP, Jordan BR, Coligan JE. Molecular cloning and DNA sequence analysis of genes encoding cytotoxic T lymphocyte-defined HLA-A3 subtypes: the E1 subtype. J Immunol. 1985;135(4):2835–2841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hill AV, Allsopp CE, Kwiatkowski D, Anstey NM, Greenwood BM, McMichael AJ. HLA class I typing by PCR: HLA-B27 and an African B27 subtype. Lancet. 1991;337(8742):640–642. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92452-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barouch D, Friede T, Stevanović S, Tussey L, Smith K, Rowland-Jones S, Braud V, McMichael A, Rammensee HG. HLA-A2 subtypes are functionally distinct in peptide binding and presentation. J Exp Med. 1995;182(6):1847–1856. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sudo T, Kamikawaji N, Kimura A, Date Y, Savoie CJ, Nakashima H, Furuichi E, Kuhara S, Sasazuki T. Differences in MHC class I self peptide repertoires among HLA-A2 subtypes. J Immunol. 1995;155(10):4749–4756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sidney J, Grey HM, Kubo RT, Sette A. Practical, biochemical and evolutionary implications of the discovery of HLA class I supermotifs. Immunol Today. 1996;17(6):261–266. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80542-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sidney J, Peters B, Frahm N, Brander C, Sette A. HLA class I supertypes: a revised and updated classification. BMC Immunol. 2008;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hillen N, Mester G, Lemmel C, Weinzierl AO, Müller M, Wernet D, Hennenlotter J, Stenzl A, Rammensee HG, Stevanović S. Essential differences in ligand presentation and T cell epitope recognition among HLA molecules of the HLA-B44 supertype. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38(11):2993–3003. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ovsyannikova IG, Vierkant RA, Pankratz VS, O’Byrne MM, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. HLA haplotype and supertype associations with cellular immune responses and cytokine production in healthy children after rubella vaccine. Vaccine. 2009;27(25–26):3349–3358. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lazaryan A, Song W, Lobashevsky E, Tang J, Shrestha S, Zhang K, Gardner LI, McNicholl JM, Wilson CM, Klein RS, Rompalo A, Mayer K, Sobel J, Kaslow RA. Human leukocyte antigen class I supertypes and HIV-1 control in African Americans. J Virol. 2010;84(5):2610–2617. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01962-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.John M, Heckerman D, James I, Park LP, Carlson JM, Chopra A, Gaudieri S, Nolan D, Haas DW, Riddler SA, Haubrich R, Mallal S. Adaptive interactions between HLA and HIV-1: highly divergent selection imposed by HLA class I molecules with common supertype motifs. J Immunol. 2010;184(8):4368–4377. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alexander J, Bilsel P, del Guercio MF, Marinkovic-Petrovic A, Southwood S, Stewart S, Ishioka G, Kotturi MF, Botten J, Sidney J, Newman M, Sette A. Identification of broad binding class I HLA supertype epitopes to provide universal coverage of influenza A virus. Hum Immunol. 2010;71(5):468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rammensee HG, Bachmann J, Stevanovic S. MHC ligands and peptide motifs. Heidelberg: Springer; 1997. p. 450. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zamvil SS, Mitchell DJ, Moore AC, Kitamura K, Steinman L, Rothbard JB. T-cell epitope of the autoantigen myelin basic protein that induces encephalomyelitis. Nature. 1986;324(6094):258–260. doi: 10.1038/324258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Engelhard VH, Altrich-Vanlith M, Ostankovitch M, Zarling AL. Post-translational modifications of naturally processed MHC-binding epitopes. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18(1):92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Haurum JS, Høier IB, Arsequell G, Neisig A, Valencia G, Zeuthen J, Neefjes J, Elliott T. Presentation of cytosolic glycosylated peptides by human class I major histocompatibility complex molecules in vivo. J Exp Med. 1999;190(1):145–150. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zarling AL, Ficarro SB, White FM, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Engelhard VH. Phosphorylated peptides are naturally processed and presented by major histocompatibility complex class I molecules in vivo. J Exp Med. 2000;192(12):1755–1762. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Skipper JC, Hendrickson RC, Gulden PH, Brichard V, Van Pel A, Chen Y, Shabanowitz J, Wolfel T, Slingluff CL, Jr, Boon T, Hunt DF, Engelhard VH. An HLA-A2-restricted tyrosinase antigen on melanoma cells results from posttranslational modification and suggests a novel pathway for processing of membrane proteins. J Exp Med. 1996;183(2):527–534. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.2.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yagüe J, Vázquez J, López de Castro JA. A post-translational modification of nuclear proteins, N(G), N(G)-dimethyl-Arg, found in a natural HLA class I peptide ligand. Protein Sci. 2000;9(11):2210–2217. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.11.2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Meadows L, Wang W, den Haan JM, Blokland E, Reinhardus C, Drijfhout JW, Shabanowitz J, Pierce R, Agulnik AI, Bishop CE, Hunt DF, Goulmy E, Engelhard VH. The HLA-A*0201-restricted H-Y antigen contains a posttranslationally modified cysteine that significantly affects T cell recognition. Immunity. 1997;6(3):273–281. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xu Y, Gendler SJ, Franco A. Designer glycopeptides for cytotoxic T cell-based elimination of carcinomas. J Exp Med. 2004;199(5):707–716. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gerard C. Purification of glycoproteins. Methods Enzymol. 1990;182:529–539. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)82042-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Calvano CD, Zambonin CG, Jensen ON. Assessment of lectin and HILIC based enrichment protocols for characterization of serum glycoproteins by mass spectrometry. J Proteomics. 2008;71(3):304–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Neville DC, Rozanas CR, Price EM, Gruis DB, Verkman AS, Townsend RR. Evidence for phosphorylation of serine 753 in CFTR using a novel metal-ion affinity resin and matrix-assisted laser desorption mass spectrometry. Protein Sci. 1997;6(11):2436–2445. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560061117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dunn JD, Reid GE, anb Bruening ML. Techniques for phosphopeptide enrichment prior to analysis by mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2010;29(1):29–54. doi: 10.1002/mas.20219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hudrisier D, Riond J, Mazarguil H, Oldstone MB, Gairin JE. Genetically encoded and post-translationally modified forms of a major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted antigen bearing a glycosylation motif are independently processed and co-presented to cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(51):36274–36280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mosse CA, Hsu W, Engelhard VH. Tyrosinase degradation via two pathways during reverse translocation to the cytosol. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;285(2):313–319. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Altrich-VanLith ML, Ostankovitch M, Polefrone JM, Mosse CA, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Engelhard VH. Processing of a class I-restricted epitope from tyrosinase requires peptide N-glycanase and the cooperative action of endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 and cytosolic proteases. J Immunol. 2006;177(8):5440–5450. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mohammed F, Cobbold M, Zarling AL, Salim M, Barrett-Wilt GA, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Engelhard VH, Willcox BE. Phosphorylation-dependent interaction between antigenic peptides and MHC class I: a molecular basis for the presentation of transformed self. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(11):1236–1243. doi: 10.1038/ni.1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zarling AL, Polefrone JM, Evans AM, Mikesh LM, Shabanowitz J, Lewis ST, Engelhard VH, Hunt DF. Identification of class I MHC-associated phosphopeptides as targets for cancer immunotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(40):14889–14894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604045103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Meyer VS, Drews O, Günder M, Hennenlotter J, Rammensee HG, Stevanović S. Identification of natural MHC class II presented phosphopeptides and tumor-derived MHC class I phospholigands. J Proteome Res. 2009;8(7):3666–3674. doi: 10.1021/pr800937k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Andersen MH, Bonfill JE, Neisig A, Arsequell G, Sondergaard I, Valencia G, Neefjes J, Zeuthen J, Elliott T, Haurum JS. Phosphorylated peptides can be transported by TAP molecules, presented by class I MHC molecules, and recognized by phosphopeptide-specific CTL. J Immunol. 1999;163(7):3812–3818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dzhambazov B, Holmdahl M, Yamada H, Lu S, Vestberg M, Holm B, Johnell O, Kihlberg J, Holmdahl R. The major T cell epitope on type II collagen is glycosylated in normal cartilage but modified by arthritis in both rats and humans. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35(2):357–366. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hanada K, Yewdell JW, Yang JC. Immune recognition of a human renal cancer antigen through post-translational protein splicing. Nature. 2004;427(6971):252–256. doi: 10.1038/nature02240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vigneron N, Stroobant V, Chapiro J, Ooms A, Degiovanni G, Morel S, Van der Bruggen P, Boon T, Van den Eynde BJ. An antigenic peptide produced by peptide splicing in the proteasome. Science. 2004;304(5670):587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1095522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dalet A, Vigneron N, Stroobant V, Hanada K, Van den Eynde BJ. Splicing of distant peptide fragments occurs in the proteasome by transpeptidation and produces the spliced antigenic peptide derived from fibroblast growth factor-5. J Immunol. 2010;184(6):3016–3024. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Warren EH, Vigneron NJ, Gavin MA, Coulie PG, Stroobant V, Dalet A, Tykodi SS, Xuereb SM, Mito JK, Riddell SR, Van den Eynde BJ. An antigen produced by splicing of noncontiguous peptides in the reverse order. Science. 2006;313(5792):1444–1447. doi: 10.1126/science.1130660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hickman HD, Luis AD, Buchli R, Few SR, Sathiamurthy M, VanGundy RS, Giberson CF, Hildebrand WH. Toward a definition of self: proteomic evaluation of the class I peptide repertoire. J Immunol. 2004;172(5):2944–2952. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yewdell JW, Nicchitta CV. The DRiP hypothesis decennial: support, controversy, refinement and extension. Trends Immunol. 2006;27(8):368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yewdell JW, Antón LC, Bennink JR. Defective ribosomal products (DRiPs): a major source of antigenic peptides for MHC class I molecules? J Immunol. 1996;157(5):1823–1826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Milner E, Barnea E, Beer I, Admon A. The turnover kinetics of major histocompatibility complex peptides of human cancer cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5(2):357–365. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500241-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Weinzierl AO, Lemmel C, Schoor O, Müller M, Krüger T, Wernet D, Hennenlotter J, Stenzl A, Klingel K, Rammensee HG, Stevanović S. Distorted relation between mRNA copy number and corresponding major histocompatibility complex ligand density on the cell surface. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6(1):102–113. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600310-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fortier MH, Caron E, Hardy MP, Voisin G, Lemieux S, Perreault C, Thibault P. The MHC class I peptide repertoire is molded by the transcriptome. J Exp Med. 2008;205(3):595–610. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Juncker AS, Larsen MV, Weinhold N, Nielsen M, Brunak S, Lund O. Systematic characterisation of cellular localisation and expression profiles of proteins containing MHC ligands. PLoS One. 2009;4(10):e7448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]