Abstract

Drug resistance continues to be a stumbling block in achieving better cure rates in several cancers. Doxorubicin is commonly used in treatment of a wide range of cancers. The aim of this study was to look into the mechanisms of how low ambient pH may contribute to down-regulation of apoptotic pathways in a gastric tumour cell line. Low pH culture conditions were found to dramatically prolong cell survival after doxorubicin treatment, an effect that was in part reversed by co-incubation with the specific p38 mitoge-activated protein kinase (MAP kinase) inhibitor SB203580, only mildly inhibited by blockade of the multi-drug resistance 1 (MDR1) transporter, but completely abolished by siRNA-mediated knockdown of the heat shock protein 27 (HSP27). In conclusion, acidic pH causes less accumulation of cytotoxic drug in the nucleus of adeno gastric carcinoma (AGS) cells and HSP27-dependent decrease in FasR-mediated gastric epithelial tumour cell apoptosis.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00018-010-0503-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: HSP27, Apoptosis, MAPKAP2, p38, Doxorubicin, AGS cells

Introduction

A tumour microenvironment is significantly different from that of the normal tissue. Due to metabolic changes and a chaotic vasculature, marked fluctuations in glucose, lactate, acidic pH and oxygen tension are seen [1]. Many regions within tumours are found to be transiently or chronically hypoxic. Cells respond to periods of hypoxia by converting from aerobic respiration to glycolysis, which in turn produces lactic acid and causes tumour acidosis [2–5]. The increased reliance on glycolysis to produce energy in many aggressive tumours occurs even in the presence of sufficient oxygen [1, 6, 7].

Although the total incidence of gastric cancer has decreased worldwide in last few years, it still remains second to that of lung cancer for deaths occurring worldwide [8]. Furthermore, in spite of recent advances achieved in the diagnosis and treatment of gastric cancer, chemotherapy remains the last hope for the survival of patients with advanced gastric cancer. Doxorubicin is one of the most extensively used drugs as a single agent and in combination therapy [9, 10].

In gastric tumour development, exposure to low pH occurs early in tumour progression, and the resistance of the malignant cells to the low intragastric pH is particularly surprising. The normal gastric mucosa needs intricate protective mechanisms against gastric acid [11], which are absent in gastric tumour cells. Therefore, other mechanisms likely mediate the resistance to ambient low pH, possibly those shared with tumour cells in general [12–16]. However, this issue has not so far been studied.

Small heat shock protein (sHSP) HSP27 has been well studied for its function as molecular chaperone [17, 18]. In mammalian cells, most HSP27 exist as large oligomeric forms, which are rapidly phosphorylated during cellular stress via the p38 MAPK/MK2 pathway [19–21], and then are present in small molecular weight dimers. These small molecular weight dimers have been implicated in the prevention of apoptosis induced by Fas death receptor (CD95 or APO-1), growth factor deprivation, hydrogen peroxide, sodium nitrate, hyperthermia, UV radiation and anticancer drugs [22].

We speculated that p38-mediated phosphorylation of HSP27 may occur in gastric tumour cells, and that this may play a role in prevention of cell death induced by agents known to up-regulate CD95, such as helicobacter infection [23], cytokines [24], cytotoxic agents [25, 26], or hypoxic conditions [27–29]. We therefore cultured cells from the well-studied AGS gastric epithelial tumour cell line and studied the effect of acid exposure on cellular stress response pathways and induction of pro-apoptotic events, nuclear doxorubicin retention (induction of the MDR1 phenotype), doxorubicin-mediated FasR (CD95) up-regulation, and on the cells behaviour to cell death induction by doxorubicin.

Materials and methods

Materials

The fetal calf serum and penicillin/streptomycin were from PAA (Pasching, Austria). Specific p38 inhibitor SB203580, actinomycin-D, and doxorubicin were from Cabiochem–Novabiochem Corp. (La Jolla, CA, USA). Antibodies against p38, MK2, phospho-MK2 (Thr222) Phospho-Ser82 HSP27-specific, Caspase-3, Caspase-8 and BID were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Anti-p38α was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Caspase-3 (Pro-Caspase) antibody was purchased from assay designs. Anti-HSP27 antibody was purchased from R & D Systems (Wiesbaden-Nordenstadt, Germany). β-Actin antibody was purchased from Abcam, Germany. Anti-FasR (CD95)-APC antibody for FACS and immunocytochemistry was purchased from Ebioscience, Germany. Hybond-ECL PVDF membrane and ECL kit were purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Buckinghamshire, UK). siRNA against HSP27, Hs_HSPB1_1 HP Validated siRNA (SI00300496) and control siRNA AllStars Negative Control siRNA (SI03650318) was purchased from Qiagen (Germany). Lipofectamine 2000 was purchased from Invitrogen, Germany.

Cell culture

Human gastric cancer cells AGS (ATCC) were cultured in 25-cm2 (Greiner, Nürtingen, Germany) culture flasks. Approximately 2 × 106 cells were used per flask containing RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), streptomycin (100 μg/mL) and penicillin (100 IU/mL). Flasks were incubated at 37°C in air enriched with 5% CO2 and humidified incubator.

Cell lysis and western blots

Approximately 1 × 106 cells were plated in a 6-well plate. Cells were serum deprived for 48 h, later 24 h (because it turned out to make no difference), and then treated with low pH (pH 6.0) media for different time point. Cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS in a 6-well plate, scraped, and resuspended in 100 μl of ice-cold RIPA buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl at pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM Na3VO4, 50 mM NaF, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 10% protease inhibitor mixture). After incubating on ice for 10 min, lysates were centrifuged (16,000g for 10 min at 4°C), and the supernatant was transferred into a new tube. Protein concentration was determined using a Bradford assay (Bio-Rad).

Western Blot analysis

Equal amounts of protein were boiled for 5 min in 4× SDS-Laemmli sample buffer (40% glycerol, 4% SDS, 4% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.4 M Tris–HCl at pH 6.7 and 2 mg/ml bromphenol blue) and then separated by 10 or 15% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto Hybond ECL PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked 1 h in 0.01% Tween 20-PBS (TPBS) containing 5% powered skim milk and then incubated with primary antibody (dilution in accordance to manufacture recommendations) overnight at 4°C. Then membranes were washed three times with TPBS and incubated for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (dilution 1:10,000 in blocking solution), washed three times with TPBS, and developed with a chemiluminiscence ECL kit.

Cell proliferation

Approximately 2 × 106 cells were plated in 25-cm2 culture flask. Cells were serum-deprived after 24 h and treated with 2 μM doxorubicin either with normal or low pH media (pH 6.7). To test the possibility that doxorubicin-induced cell death involves the p38 MAP Kinase pathway, the low pH cells were exposed to a cocktail of doxorubicin and SB203580 (5 μM). Cells were counted after 48 h of treatment. Similar experiments were performed in the presence of both doxorubicin (2 μM) and verapamil 10 μM at normal and low pH condition. Two different pH conditions were used for western blot analysis and cell proliferation assay. For western blot analysis, very low pH (pH 6.0) was used to see the effect of low pH on phosphorylation of p38 and downstream pathways in a short incubation time. This low pH, however, was not optimal for long-term culture. We found pH 6.7 an optimal value for longer survival, but nevertheless an effect of acidosis on phosphorylation of p38 and downstream pathway was seen.

siRNA knockdown of HSP27 and cell survival assay

Double-stranded siRNA molecules with a two-base overhang at the 3′-end of the antisense strand corresponding to HSP27, was purchased from Qiagen. HSP27 mRNA target sequence was: 5′-(GGA CGA GCA UGG CUA CAU C)dTdT-3′. AllStars Negative Control siRNA was used as a control. Then, 2 × 104 cells were plated in a 24-well plate 1 day before the transfection. The next day, cells were washed and changed with 400 μl of the antibiotic-free medium. Transfection was performed as per manufactures instructions using commercially available Lipofectamine 2000. After 24 h, the cells were washed and incubated with serum-free doxorubicin (2 μM)-containing medium for 48 h. The number of surviving cells counted at the end of 48 h using trypan blue.

Semi-quantitative reverse transcription PCR

Expression of FasR mRNA in doxorubicin treated cells kept under normal and low pH condition was determined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. A sample of 2 × 106 cells were plated in 25-cm2 culture flask. Cells were serum-deprived after 24 h and treated with 2 μM doxorubicin either with normal or low pH media (pH 6.7). Total RNA was extracted using NuceoSpin RNA II kit from Macherey–Nagel as per manufacturer’s instructions. Then, 3 μg of total RNA was used for the cDNA synthesis using Superscript III RT from Gibco as per manufacturer’s instructions. Primers for human FasR were taken from the previous publication by Komada et al. [30]. FasR forward primer was 5′-CACTTCGGAGGATTGCTCAACA-3′ and reverse primer was 5′-TATGTTGGCTCTTCAGCGCTA-3′ which yielded a single band of 1,166 bp. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was performed as described previously in Rossmann et al. [31] and Histone3, family A (H3F3A) was used as an internal control. Primers for Histone3 were deduced from the published sequence (NM_002107.3) (forward primer: 5′-CCACTGAACTTCTGATTCGC-3′, reverse primer: 5′-GCGTGCTAGCTGGATGTCTT-3′). The PCR product was around 215 bp. The ethidium bromide gel pictures were digitalized by KODAK Digital Science Image Station 440CF and their optical density was measured by TotalLab software (Nonlinear Dynamics, England).

FACS analysis

Up-regulation of the FasR (CD95) was estimated by FACS-analysis of the cells by treating the cells with 2 μM concentration of doxorubicin for 3 h after depriving the cell with serum at different pH condition. Staining of the cells for the FasR was done as per company recommendations, unstained and isotype control cell were analyzed for the control.

Confocal microscopy

To measure the amount of doxorubicin in the AGS cells, cells were incubated in the presence of doxorubicin (2 μM) and co-incubated with doxorubicin (2 μM) and verapamil (10 μM). After 8 h of incubation at physiological pH and at lower pH, cells were washed with PBS just before the image was taken, and incubated in 37°C PBS while imaging. Images were collected using Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope with a ×40 water immersion lens. Doxorubicin fluorescence was excited with an argon laser at 488 nm, and the emission was collected through a 530-nm long-pass filter. The same confocal settings (excitation, laser power, detector gain, and pinhole size) were used to image the cells at physiological pH (7.2) and cells at acidic pH (6.7). Data acquisition and image analysis was performed using Leica software. Cell images were analyzed as mean doxorubicin fluorescent intensity in a circular region of interest around the nucleus. Multiple fields containing many cells/field were imaged in each experiment. Results were obtained from analyzing images from three experiments.

Microfluorometric determination of intracellular pH

Fluorescence microscopy for determination of pHi was performed exactly as described previously [32, 33] using the fluorescent dye BCECF, by perfusing the cells with perfusion buffer of different pH and subsequent calibration with the high-K+/nigericin method. In brief, cells were loaded with BCECF dye at 37°C and perfused with solution of different pH. The base line pH was achieved by pefusing cells with a solution of pH 7.2. After the baseline have been achieved cell were perfused with a solution of pH 6.0 and intracellular pH was determined for another 15 min. For 45 min and 2 h time points, cells were incubated in the perfusion solution for that long and then pH was determined. Similarly, cells cultured at physiological pH for 24 and 48 h were directly taken for the pH measurement (Table 1).

Table 1.

Intracellular pH of the cells during incubation with medium of different pH for different time points

| Medium pH | Incubation time | Extra-cellular pH | Cellular pH |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6.0 | 3 min | 6.0 | 6.64 ± 0.05 |

| 6.0 | 15 min | 6.0 | 6.54 ± 0.09 |

| 6.0 | 45 min | 6.0 | 6.60 ± 0.07 |

| 6.0 | 2 h | 6.0 | 6.67 ± 0.10 |

| 6.7 | 24 h | 6.81 ± 0.06 | 6.94 ± 0.07 |

| 6.7 | 48 h | 6.87 ± 0.08 | 6.97 ± 0.05 |

| 7.2 | N. A. | 7.25 ± 0.38 | 7.08 ± 0.03 |

While incubation with medium of pH 6.0, cellular pH decreases minimum to a value of 6.54 within the 15 min and then it started recovering. Long time incubation with medium of pH 6.7 shows differences both in extracellular pH as well as in intracellular pH. Extracellular pH was 0.1–0.2 units higher than the starting pH, and cellular pH was 0.1–0.2 units higher than the extracellular pH

Statistics

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM from three or more experiments, and they were statistically evaluated by Student’s t test. Differences were considered significant when p < 0.05.

Results

Acidic pH can prevent AGS cell death due to doxorubicin exposure in a p38 MAP-kinase-dependent fashion

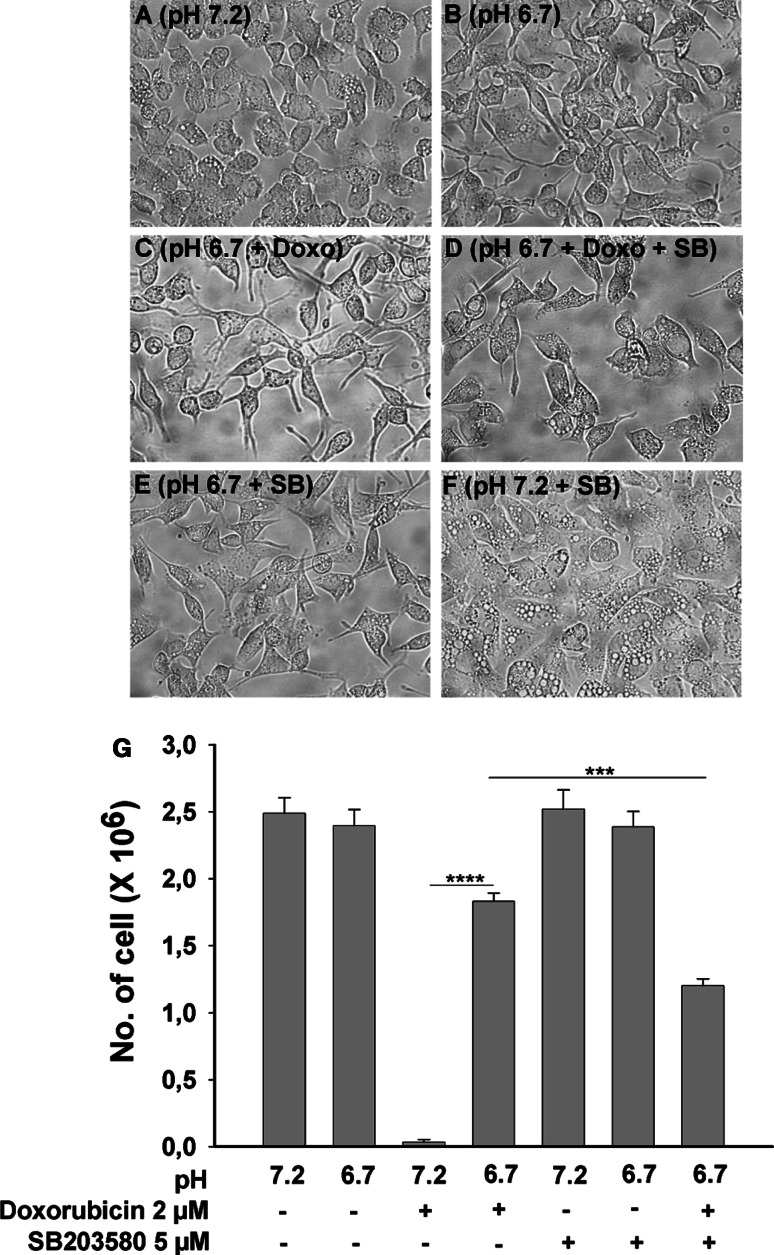

A period of 48 h of serum deprivation at pH 7.2 caused AGS-cells to develop some intracellular vacuoles, and this vacuolar phenotype was strongly enhanced by co-incubation with the specific p38 inhibitor SB203580 (5 μM) (Fig. 1a, f), suggesting that the inhibition of the p38 MAP kinase was detrimental to the cells (even though the p38 phosphorylation level was found to be quite low under these conditions, see Fig. 6, below). The formation of vacuoles was completely prevented by culturing the cells at a pH of 6.7 (Fig. 1b–e), but the actual cell number was similar in both conditions (Fig. 1g). AGS cells treated with 2 μM concentration of doxorubicin for 48 h at normal pH (pH 7.2) did not survive (Fig. 1g), while cells which were treated with same concentration of doxorubicin at low pH (pH 6.7) condition showed significantly better survival (Fig. 1c, g). Co-incubation with the specific p38 MAP-kinase inhibitor SB203580 (5 μM) [34] partially prevented the acid-induced survival benefit (Fig. 1d, g). Interestingly, these experiments demonstrate that even mild acidosis prevents doxorubicin-induced cell death in part via the p38 MAP-kinase pathway.

Fig. 1.

Low ambient pH rescues AGS cells from doxorubicin-induced cell death. Morphology of the cells cultured under various conditions. 2 × 106 AGS cell were cultured in serum free condition for 48 h. Cells cultured at physiological pH (pH 7.2) showed some vacuolization (a), which was not present at pH 6.7 (b), seen much more pronounced in the presence of SB203580 (f), and was largely prevented by concomitant incubation at pH 6.7 (e). In the presence of doxorubicin, cells did not survive at pH 7.2 (g), whereas a large number of cells remained viable after 48 h in 2 μM doxorubicin at pH 6.7 (c,g). Co-incubation with SB203580 along with doxorubicin induced significantly higher number of cell death as compared to doxorubicin alone at pH 6.7 (d, g). g Bars indicate the total number of cells left after 48 h of culture. Results are ± SEM. *Significant low no. of cells between the two groups connected via horizontal line: ***<0.0001 and ****<0.00001

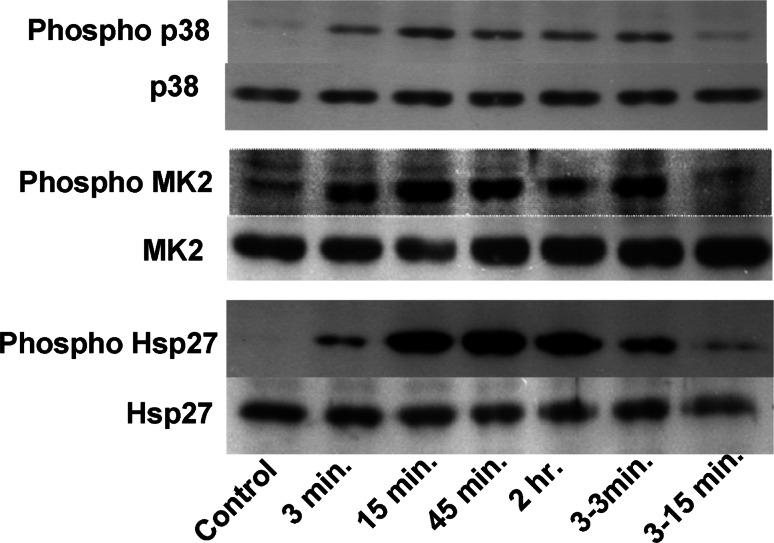

Fig. 6.

Incubation at low pH results in a rapid and sustained phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase, the downstream target MK2, and HSP27. Time kinetics for AGS cells were exposed to acid (pH 6.0) for the indicated time periods and phospho-p38, phosphr MK2 and phosphoHSP27 levels was measured by western blot. Total p38, MK2 and HSP27 was taken as loading control, and demonstrated that acid exposure did not change the amount of these proteins. The time kinetics experiment shows that even in the presence of stimuli the level of phosphorylated kinase comes down after 45 min. A short exposure of stimuli for 3 min did not have a long-lasting effect (3–3 min and 3–15 min). Level of increased phosphorylated kinase was down to the level of control after 15 min when stimulus was taken off after 3 min

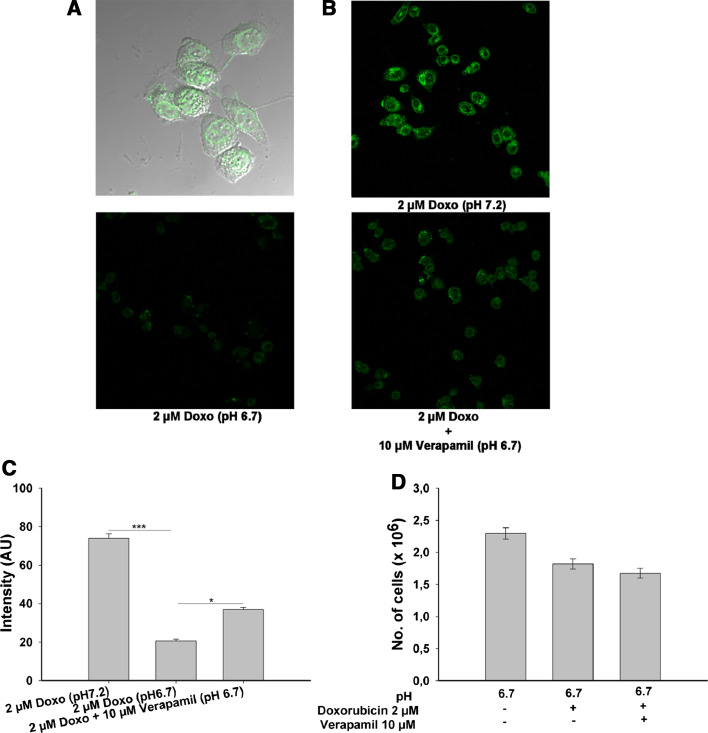

Low pH condition decreases the accumulation of doxorubicin in AGS cells

It has been shown that low pH can increase the transport rate of the MDR1 gene product P-gp in rat prostrate cancer cells (AT1) [34]. P-gp is responsible for resistance in many cancer against the anti-cancer drugs due to export of the chemotherapeutic agents [35–37]. We measured the amount of doxorubicin retained in the nucleus of the AGS cells cultured at physiological (pH 7.2) and low pH condition (pH 6.7) after the 8 h of the incubation. A significant difference between the two groups was found; cells incubated at pH 7.2 retained significantly higher amounts of doxorubicin as compared to cell at pH 6.7 (Fig. 2b, c). Further, co-incubation with the verapamil (inhibitor of MDR1 gene product, p-glycoprotien) significantly increases the doxorubicin retention under low pH condition (Fig. 2b, c). Doxorubicin was exclusively retained in the nucleus (Fig. 2a), as shown by merge picture of doxorubicin (green) and differential interference contrast picture of AGS cells. These results demonstrate that in AGS cells, acidic pH conditions leads to decreased intracellular doxorubicin concentrations.

Fig. 2.

Intracellular doxorubicin concentration in cells incubated at physiological and low ambient pH. Overlay of transmission picture of cells and nuclei shows that most of the doxorubicin (green) is retained in the nucleus (a). The doxorubicin retention was significantly higher at pH 7.2 than at low pH, and co-incubation with 10 μM verapamil significantly increased the doxorubicin retention at lower pH (b). c Mean intensity from 35 nuclei in the various groups. d Despite significantly higher intracellular doxorubicin concentration, upon co-incubation with 10 μM verapamil along with 2 μM doxorubicin did not affect cell survival. Results are ± SEM. *Significant high amount of doxorubicin in the nuclei of cells connected via horizontal line: *<0.01 and ***<0.001

Acidic pH can prevent cell death due to doxorubicin exposure in the presence of verapamil

Since co-incubation with verapamil significantly increased the retention of doxorubicin in the nucleus of the cells cultured at low pH condition, we wondered how this will affect the cell survival. There were no differences in the cell survival when cells were incubated with doxorubicin alone or co-incubated with a mixture of doxorubicin and verapamil (Fig. 2d). This favours the notion that the up-regulation of doxorubicin export by P-gp is not the only acid-induced mechanism that protects AGS cells from cell death.

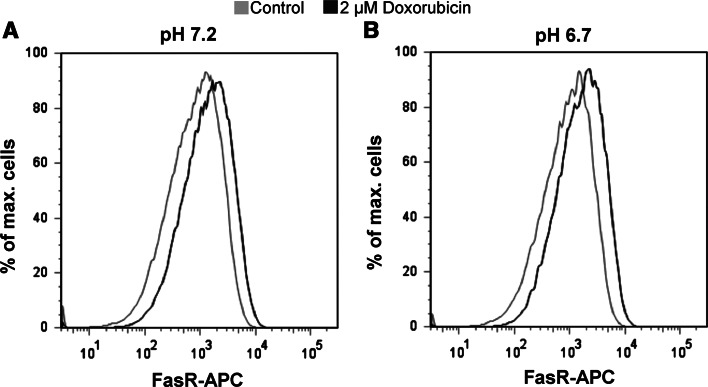

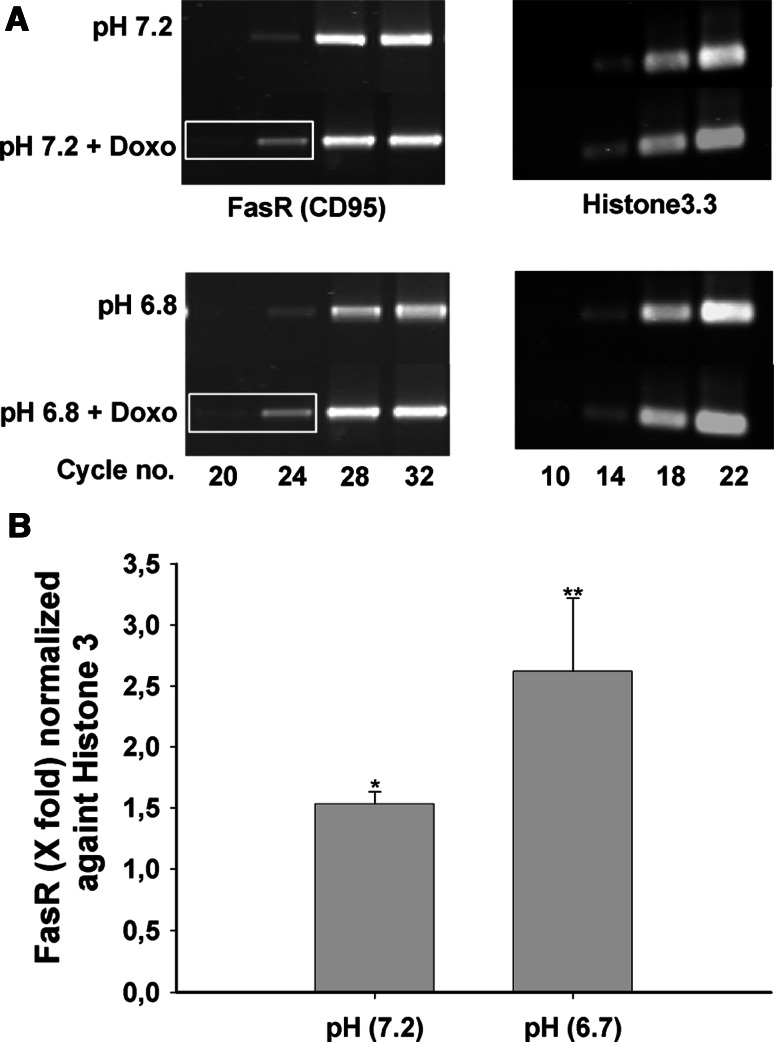

Doxorubicin induced the expression of Fas-receptor (FasR or CD95) both at mRNA and protein level

Doxorubicin-induced apoptosis has been reported to occur via CD95 (APO-1/Fas) receptor/ligand system [25, 26]. We tested whether CD95 is up-regulated in AGS cells treated with 2 μM doxorubicin both on the mRNA and protein level. After 3 h of incubation with 2 μM doxorubicin, significant up-regulation of Fas-R protein level was detected both at pH 7.2 and pH 6.7 in doxorubicin (2 μM)-treated cells as compared to non-treated cells (Fig. 4a, b). We also saw a significant upregulation at mRNA level (Fig. 3a, b). The up-regulation in the FasR protein after the doxorubicin treatment was further confirmed by immunocytochemistry (Supplementary Fig. 1a and b).

Fig. 4.

Up-regulation of FasR expression by doxorubicin in AGS cells. a The left panel shows the histogram of FasR-APC of the cells processed at the pH 7.2. The cells which were treated with the doxorubicin for 3 h (black curve) show clearly more cells which were APC positive as compared to the control cells (grey curve). b Similar results were obtained when cells were processed at the acidic pH (pH 6.7)

Fig. 3.

Up-regulation of FasR expression by doxorubicin in AGS cells. a The left panel shows the semiquantitative PCR for the FasR, with distinctly stronger bands at cycle no. 20 and 24 in the presence compared to the absence of 2 μM doxorubicin. The same up-regulation was seen when the cells were incubated at pH 6.7. Right panel shows the Histone3 band. b Densitometry calculation from cycle 24 of FasR and cycle 18 from the Histone3 show 1.5- and 2.6-fold difference at pH 7.2 and pH 6.7, respectively. Results are ± SEM. *Significantly higher value as compared to the control cells which did not get doxorubicin treatment: *≤0.01 and **≤0.001

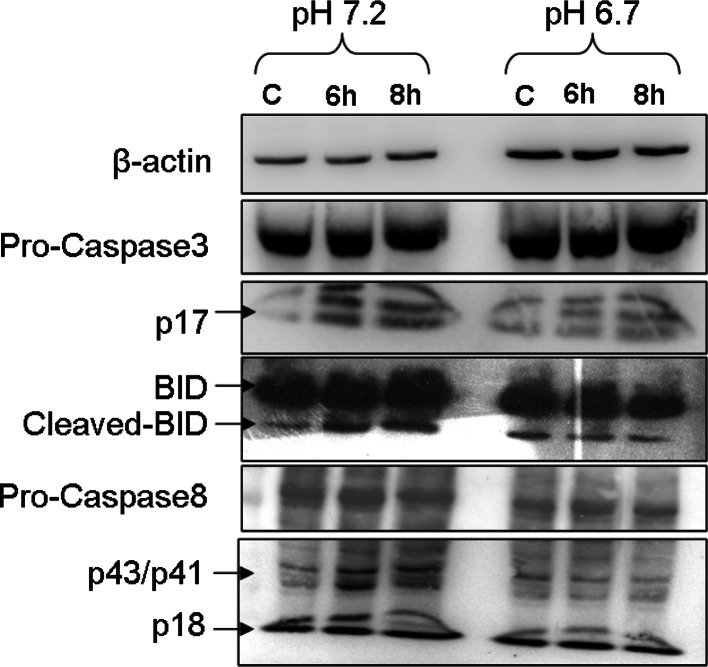

Doxorubicin induced the activation of Caspase-8, Caspase-3 and BID at pH 7.2

Since incubation of doxorubicin induced upregulation of FasR, we next looked for activation of different caspases. Activation of Caspase-8, Caspase-3 and BID was assessed by detecting the cleaved version of the above-mentioned proteins. Some caspase activity was present in the control condition (serum-deprivation at pH 7.2) (Fig. 5). Doxorubicin exposure resulted in an increase of the cleaved products for caspase-3 (p17), of cleaved BID, and of the caspase-8 cleavage products p41/p43 (less clear for p18) after doxorubicin incubation at pH 7.2 but not at pH 6.7 (Fig. 5). These results indicate that, despite similar FasR induction by doxorubicin at both incubation pH values, the subsequent activation of apoptotic pathways was prevented by the low pH. Doxorubicin induced strong DNA fragmentation at pH 7.2 in a time-dependent manner, underlining the induction of apoptosis by incubating the cells with 2 μM doxorubicin (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 5.

Doxorubicin induces activation of BID, Caspase-8 and -3. The uppermost row show the expression of β-actin as a loading control. The third row from the top clearly shows that there is more activated caspase-3 protein as compared to the control in pH 7.2 group. At the same time, this up-regulation in activated caspase-3 upon doxorubicin treatment was much greater as compared to the cells at the acidic pH (pH 6.7). The total caspase-3 level remains more or less the same (second row). The bottom two rows indicate the expression to total and activated (cleaved) caspase-8. The total protein remains more or less same and at the same time there was not that much difference in the activated caspase-8 (p18) expression. The other cleaved version of caspase-8 looks a little bit elevated at pH 7.2, while the expression of all the three bands looks very similar to pH 6.7. Expression of total BID protein remains more or less same in all the six lanes. The cleaved (activated) version shows a small amount of up-regulation only when incubated at pH 7.2

Acidic pH results in p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation in AGS cells

In AGS cells, exposure to low pH (pH 6.0) caused rapid and long-lasting p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation (Fig. 6, first lane). The phosphorylation level of p38 is increased as early as 3 min post-exposure, and is short lived when acid exposure is discontinued. During chronic acid exposure, p38 phosphorylation level declines but stays elevated above the baseline at 2 h post-exposure. A similar time course was seen for the phosphorylation of the downstream target of p38, MAP kinase 2 (MK2). The experiments show that, in AGS cells, acid exposure causes a rapid phosphorylation of p38 as well as of the downstream target MK2.

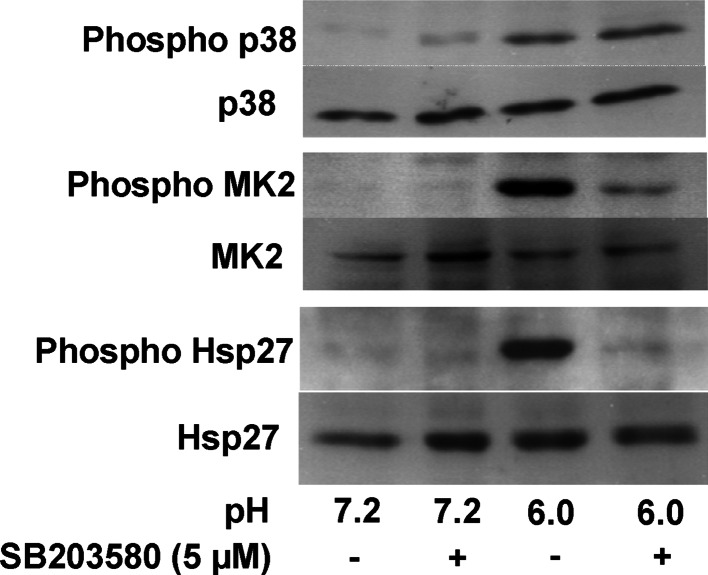

Acidic pH results in rapid and prolonged phosphorylation of the heat shock protein 27

Chronic exposure to acidic ambient pH (pH 6.0) caused rapid and prolonged phosphorylation of the heat shock protein HSP27 in AGS cells, whereas a short acid pulse resulted in a transient phosphorylation (Fig. 6, third lane). Acid-induced phosphorylation of HSP27, and MK2 were completely inhibited by co-incubation with the specific p38 inhibitor SB203580 (Fig. 7), suggesting that both HSP27 and MK2 phosphorylation are downstream events of p38 activation. Phosphorylation state of p38 was not affected from the incubation with SB203580. This indicates that acidic pH induces phosphorylation of HSP27 in a p38/MK2-specific way, as has been reported previously [19–21].

Fig. 7.

Acid-induced phosphorylation of HSP27 is p38 dependent. AGS cells were incubated at pH 7.2 and 6.0 for 10 min in the absence and presence of SB203580, a specific inhibitor of p38 MAP Kinase. The presence of SB203580 did not alter acid-induced phosphorylation of p38, but strongly reduced that of MK2 and HSP27

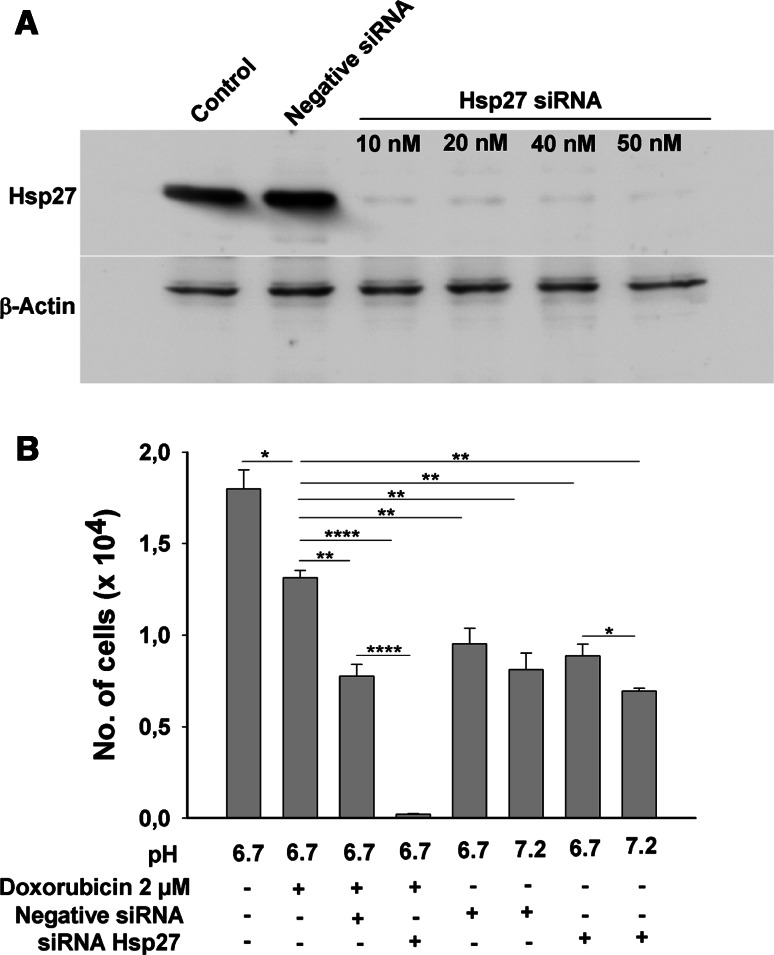

siRNA-mediated knockdown of HSP27 have negative effect on cell survival

To investigate the involvement of HSP27 phosphorylation in the acid-mediated protection against doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in AGS cells, siRNA-mediated down-regulation of HSP27 protein was performed, and 50 nM concentration of siRNA was able to knock down ~80% of the total protein (Fig. 8a). Cells were then cultured at low pH in serum-free condition with 2 μM concentration of doxorubicin, with and without siRNA treatment for 48 h. The transfection reagent per se had a negative effect on cell survival. However, control and “Allstars Negative” siRNA-treated cells could survive better in the presence of 2 mM doxorubicin than the siRNA HSP27-treated cells, which all died (Fig. 8b, left bars). This indicates a direct involvement of HSP27 in prevention of apoptosis against doxorubicin. In the absence of doxorubicin treatment, the cells transfected with siRNA for HSP27 had significantly better survival at normal and at low pH (Right bars).

Fig. 8.

siRNA knockdown of HSP27 abolishes acid-conveyed resistance against doxorubicin-induced cell death. a A concentration of 50 nM siRNA against the HSP27 was able to knock down ~80% of the total HSP27, whereas “Allstars Negative” siRNA had no effect on cellular HSP27 content. β-Actin was taken as loading control which is the same in all the lanes. b Furthermore, in the cell survival experiments (similar to Fig. 1), the cells transfected with negative siRNA had better survival as compared to that of siRNA HSP27-transfected cells. Results are ± SEM. *Significant low no. of cells between the two groups connected via horizontal line.:*<0.01, **<0.001 and ****<0.00001

Discussion

In this paper, we have investigated the role of HSP27 in the protection against doxorubicin-induced cell death by low ambient pH (pH 6.7) in gastric epithelial tumour cells. Incubation at low pH conveyed a strong survival benefit during incubation with 2 μM doxorubicin as compared to the cells incubated at physiological pH (pH 7.2), which was partially reversed by co-incubation with the specific inhibitor of p38 MAP kinase pathway (SB203580, 5 μM) and completely reversed by siRNA-mediated knockdown of HSP27. A second phenomenon which likely contributes to the survival benefit in low ambient pH was a decrease in doxorubicin concentration during culture in low compared to normal pH, which was partially reversed by verapamil and therefore likely due to up-regulation of doxorubicin export via MDR1 (P-glycoprotein), as has been described for rat prostate cancer cells (AT1) [34]. However, we could not verify an inverse correlation between doxorubicin content in the nucleus and cell survival, which may be due to the fact that other low pH-induced factors play a larger role compared to P-gp up-regulation in this cancer cell line.

There is ample evidence for a low extracellular pH in the vicinity of tumour cell masses [4, 5]. This low pH is secondary to up-regulation of glycolysis, likely as a result of active selection processes providing growth advantage to tumour cells. The environmental acidosis facilitates tumour invasion through destruction of adjacent normal populations, degradation of the extracellular matrix and promotion of angiogenesis [2, 3]. In gastric cancers, tumour cells are additionally exposed to the low luminal pH. The adenogastric carcinoma cell line (AGS) showed a strongly increased tolerance to doxorubicin exposure in acidic pH (6.7) as compared to physiological pH (7.2), and this increased tolerance was partially reversed by co-incubation with p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580. Serum deprivation alone had a detrimental effect on the microscopic appearance of the cells with increased number of vacuoles, which was enhanced by co-incubation with the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580, and completely prevented by low ambient pH. Taken together, the results suggested that low ambient pH provide a p38-dependent cell survival benefits both during doxorubicin exposure and serum deprivation.

Resistance against chemotherapeutic agents in tumour cells has been linked to up-regulation of the gene encoding the P-glycoprotein MDR1 due to transcriptional mechanism(s) [35, 36]. A recent study by Sauvant et al. [34] in rat prostate cancer cell (AT1) provided evidence for a p38- and ERK-dependent increase in MDR1-mediated transport rate, resulting in an increase in daunorubicin (a similar drug as doxorubicin) excretion and reduced cellular toxicity. We also found evidence for decreased intracellular doxorubicin concentrations when cells are cultured at low ambient pH. Since this effect was partially reversed by the MDR1 transport inhibitor verapamil [38], it was likely that MDR1 is involved in doxorubicin excretion in AGS cells as well. To our surprise, verapamil did not reduce cell viability as well under these conditions. This suggested to us that another protective mechanism is additionally activated by low ambient pH.

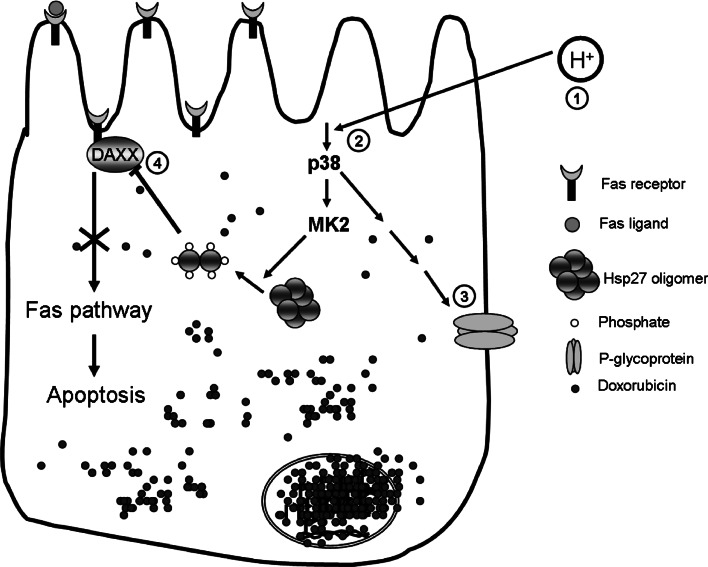

Doxorubicin can induce apoptosis via FasR/FasL system [25, 26]. Up-regulation of FasR expression upon doxorubicin exposure was seen in AGS cells both on the mRNA and protein level (Figs. 3, 4, Supplementary Fig. 1). We hypothesised that low pH activates a pathway which can prevent apoptosis via FasR/FasL system. HSP27 exist in large oligomeric forms in many of the mammalian cells and serves as a molecular chaperone [17, 18]. Cellular stress induces HSP27 phosphorylation via p38/MK2, upon which HSP27 is present predominantly in dimers [19–21]. This dimeric form has been shown to prevent apoptosis induced via FasR/FasL system by sequestering the DAXX molecule, important for the downstream signal transduction [39, 40]. We tested this hypothesis in AGS cells and found that incubation at low pH induced rapid and sustained phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase as well as of the downstream targets MK2 and HSP27. These phosphorylation steps were pathway-specific as, in the presence of specific inhibitor of p38, SB203580, the downstream phosphorylation steps were abolished (Fig. 7). During long exposure times to low pH, phosphorylation levels of p38 and MK2 increased to a maximum at about 15 min followed by decrease to a basal value at around 2 h. Thus, low ambient pH induces p38 phosphorylation, as has been found for esophageal cancer cells [41], and this phosphorylation was found to be one essential event in the antiapoptotic effect of low ambient pH. We then investigated whether HSP27 is directly involved in the prevention of doxorubicin-induced apoptosis by low ambient pH. We used siRNA-mediated knockdown of HSP27 and assessed the effect on doxorubicin-induced apoptosis. Data analysis was complicated by the fact that (1) the transfection procedure per se reduced cell viability and (2) HSP27 knockdown reduced cell viability in the serum-free conditions (which also initiate cell death, albeit at a much lower rate than doxorubicin treatment), and this is consistent with the anti-apoptotic effect of this protein in general [42]. Nevertheless, it became clear that the protective effect of low ambient pH on cell survival during doxorubicin exposure was completely ablated by HSP27 knockdown, indicating a direct involvement of HSP27 in the prevention of doxorubicin-induced apoptosis by low ambient pH. Since low ambient pH lead to HSP27 phosphorylation, we conclude that this is a critical step necessary for HSP27-mediated protection against doxorubicin-induced apoptosis by low ambient pH (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Working hypothesis of low pH induced resistance of AGS cells against doxorubicin toxicity. Intracellular acidosis activates p38 MAP kinase pathway here p38 which phosphorylates HSP27 via MK2. Phospho-HSP27 can block the apoptosis by preventing the interaction of DAXX to the FasR and may have other as yet unrecognized protective functions. In addition, doxirubicin accumulation in AGS cells is strongly reduced at low ambient pH, and this is in part mediated via P-glycoprotein (MDR1)

The mode of doxorubicin-induced cell death is controversially discussed. In a recent publication, Miyata et al. [43] showed that doxorubicin-induced death of cardiomyocytes can occur in an apoptosis-independent manner. While they also found a significant up-regulation of FasR as well as FasL, Fas signaling appeared to induce cell death via induction of inflammation and fibrosis and through generation of reactive oxygen species. Gastric tumour cells have not been previously studied in this respect. We also found significant increase in both mRNA (Fig. 3) as well as protein (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 1) of FasR after doxorubicin treatment, but in addition did see the induction of apoptotic events at pH 7.2 which were not observed at pH 6.7. One substantial difference between our study and that by Mitaya may be the use of gastric tumour cells, which behave both heterogenously in their time pattern of FasR up-regulation (see Supplementary Fig. 2) and time to apoptosis, and, as a population, require a relatively long time until 100% death rate, even at pH 7.2, considering the early time point at which we detected pro-apoptotic events. Of course, we cannot exclude the induction of other, apoptosis-independent, pathways by doxorubicin as has been proposed in the previous article [43].

AGS cells showed an elevated level of caspase activation even in the absence of doxorubicin, which could be due to serum deprivation or due to some intrinsic properties of this cell line. Nevertheless, doxorubicin treatment further increased pro-apoptotic events such as caspase cleavage at pH 7.2 but not at pH 6.7, and clearly resulted in DNA laddering, another indication for apoptosis activation.

In summary, we have shown that low ambient pH promotes survival of gastric epithelial tumour cells during doxorubicin exposure, and that this protective effect is in part mediated via p38/MK2-dependent HSP27 phosphorylation. Our data also indicate that HSP27 knockdown completely abrogated the protective effect of low ambient pH, making HSP27 an interesting target to overcome acidosis-induced chemoresistance. Other acidosis-induced events are likely involved, the elucidation of which deserves further study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgesellschaft (SFB621-C9, and Se460/9-5 and 9-6) and from the Volkswagen Stiftung (all to U.S.), a stipend from the MD/PhD program “Molecular Medicine” of the Hannover Biomedical Research School to Anurag Kumar Singh. We thank Prof. Matthias Gaestel for thorough reading of the manuscript and his critical suggestions. We would like to extend our thanks to Dr. Basant Kumar Thakur and Katja Vosskuhl for technical help. We thank Dr. Ralf Gerhard for proving us BID, Caspase-3 and Caspase-8 antibody.

Abbreviations

- MDR

Multi-drug resistance

- MAP kinase

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- HSP

Heat shock protein

- AGS

Adeno gastric carcinoma

References

- 1.Semenza GL, Artemov D, Bedi A, Bhujwalla Z, Chiles K, Feldser D, Laughner E, Ravi R, Simons J, Taghavi P, Zhong H. ‘The metabolism of tumours’: 70 years later. Novartis Found Symp. 2001;240:251–260. doi: 10.1002/0470868716.ch17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gatenby RA, Gawlinski ET. A reaction-diffusion model of cancer invasion. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5745–5753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gatenby RA, Gawlinski ET. The glycolytic phenotype in carcinogenesis and tumor invasion: insights through mathematical models. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3847–3854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffiths JR. Are cancer cells acidic? Br J Cancer. 1991;64:425–427. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shrode LD, Tapper H, Grinstein S. Role of intracellular pH in proliferation, transformation, and apoptosis. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1997;29:393–399. doi: 10.1023/A:1022407116339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaupel P, Kallinowski F, Okunieff P. Blood flow, oxygen and nutrient supply, and metabolic microenvironment of human tumors: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6449–6465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warburg O. The metabolism of tumors. London: Constable; 1930. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Smigal C, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:106–130. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kulig J, Kolodziejczyk P, Sierzega M, Bobrzynski L, Jedrys J, Popiela T, Dadan J, Drews M, Jeziorski A, Krawczyk M, Starzynska T, Wallner G. Adjuvant chemotherapy with etoposide, adriamycin and cisplatin compared with surgery alone in the treatment of gastric cancer: a phase III randomized, multicenter, clinical trial. Oncology. 2010;78:54–61. doi: 10.1159/000292360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scartozzi M, Galizia E, Verdecchia L, Berardi R, Antognoli S, Chiorrini S, Cascinu S. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer: across the years for a standard of care. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8:797–808. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.6.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen A, Flemström G. Gastroduodenal mucus bicarbonate barrier: protection against acid and pepsin. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C1–C19. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00102.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams AC, Collard TJ, Paraskeva C. An acidic environment leads to p53 dependent induction of apoptosis in human adenoma and carcinoma cell lines: implications for clonal selection during colorectal carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 1999;18:3199–3204. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ober SS, Pardee AB. Intracellular pH is increased after transformation of Chinese hamster embryo fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:2766–2770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.9.2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLean LA, Roscoe J, Jorgensen NK, Gorin FA, Cala PM. Malignant gliomas display altered pH regulation by NHE1 compared with nontransformed astrocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C676–C688. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.4.C676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez-Zaguilan R, Lynch RM, Martinez GM, Gillies RJ. Vacuolar-type H(+)-ATPases are functionally expressed in plasma membranes of human tumor cells. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:C1015–C1029. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.4.C1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gottlieb RA, Giesing HA, Zhu JY, Engler RL, Babior BM. Cell acidification in apoptosis: granulocyte colony-stimulating factor delays programmed cell death in neutrophils by up-regulating the vacuolar H(+)-ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5965–5968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welsh MJ, Gaestel M. Small heat-shock protein family: function in health and disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;851:28–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lelj-Garolla B, Mauk AG. Self-association and chaperone activity of Hsp27 are thermally activated. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8169–8174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freshney NW, Rawlinson L, Guesdon F, Jones E, Cowley S, Hsuan J, Saklatvala J. Interleukin-1 activates a novel protein kinase cascade that results in the phosphorylation of Hsp27. Cell. 1994;78:1039–1049. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90278-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rouse J, Cohen P, Trigon S, Morange M, Alonso-Llamazares A, Zamanillo D, Hunt T, Nebreda AR. A novel kinase cascade triggered by stress and heat shock that stimulates MAPKAP kinase-2 and phosphorylation of the small heat shock proteins. Cell. 1994;78:1027–1037. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90277-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stokoe D, Engel K, Campbell DG, Cohen P, Gaestel M. Identification of MAPKAP kinase 2 as a major enzyme responsible for the phosphorylation of the small mammalian heat shock proteins. FEBS Lett. 1992;313:307–313. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81216-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garrido C, Gurbuxani S, Ravagnan L, Kroemer G. Heat shock proteins: endogenous modulators of apoptotic cell death. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286:433–442. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montecucco C, Rappuoli R. Living dangerously: how Helicobacter pylori survives in the human stomach. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:457–466. doi: 10.1038/35073084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie K. Interleukin-8 and human cancer biology. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2001;12:375–391. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(01)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friesen C, Herr I, Krammer PH, Debatin KM. Involvement of the CD95 (APO-1/FAS) receptor/ligand system in drug-induced apoptosis in leukemia cells. Nat Med. 1996;2:574–577. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakamura T, Ueda Y, Juan Y, Katsuda S, Takahashi H, Koh E. Fas-mediated apoptosis in adriamycin-induced cardiomyopathy in rats: in vivo study. Circulation. 2000;102:572–578. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim MJ, Lim HS, Yoo YB, Lee YI, Hahm DH, Lee HJ, Jung KW, Kim JW, Yoe SM, Chung DC, Chang YP. Expression of CD95 and CD95L on astrocytes in the CA1 area of the immature rat hippocampus after hypoxia-ischemia injury. Comp Med. 2007;57:581–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu T, Laurell C, Selivanova G, Lundeberg J, Nilsson P, Wiman KG. Hypoxia induces p53-dependent transactivation and Fas/CD95-dependent apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:411–421. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yaniv G, Shilkrut M, Lotan R, Berke G, Larisch S, Binah O. Hypoxia predisposes neonatal rat ventricular myocytes to apoptosis induced by activation of the Fas (CD95/Apo-1) receptor: Fas activation and apoptosis in hypoxic myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;54:611–623. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00264-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Komada Y, Inaba H, Zhou Y, Zhang X, Tanaka S, Azuma E, Sakurai M. mRNA expression of Fas receptor (CD95)-associated proteins (Fas-associated phosphatase-1/FAP-1, Fas-associating protein with death domain/FADD, and receptor-interacting protein/RIP) in human leukaemia/lymphoma cell lines. Br J Haematol. 1997;99:325–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.3903204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rossmann H, Bachmann O, Vieillard-Baron D, Gregor M, Seidler U. Na+/HCO3 − cotransport and expression of NBC1 and NBC2 in rabbit gastric parietal and mucous cells. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1389–1398. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70503-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bachmann O, Sonnentag T, Siegel WK, Lamprecht G, Weichert A, Gregor M, Seidler U. Different acid secretagogues activate different Na+/H+ exchanger isoforms in rabbit parietal cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G1085–G1093. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.5.G1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossmann H, Sonnentag T, Heinzmann A, Seidler B, Bachmann O, Vieillard-Baron D, Gregor M, Seidler U. Differential expression and regulation of Na(+)/H(+) exchanger isoforms in rabbit parietal and mucous cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G447–G458. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.2.G447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sauvant C, Wirth C, Gekle M, Thews O. Acidosis induces multi-drug resistance in rat prostrate cancer cells (AT1) is mediated by ERK and p38. Acta Physiol. 2007;189:o05–o06. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fardel O, Lecureur V, Guillouzo A. The P-glycoprotein multidrug transporter. Gen Pharmacol. 1996;27:1283–1291. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(96)00081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldstein LJ. MDR1 gene expression in solid tumours. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:1039–1050. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuwano M, Toh S, Uchiumi T, Takano H, Kohno K, Wada M. Multidrug resistance-associated protein subfamily transporters and drug resistance. Anticancer Drug Des. 1999;14:123–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shen F, Chu S, Bence AK, Bailey B, Xue X, Erickson PA, Montrose MH, Beck WT, Erickson LC. Quantitation of doxorubicin uptake, efflux, and modulation of multidrug resistance (MDR) in MDR human cancer cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:95–102. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.127704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charette SJ, Landry J. The interaction of HSP27 with Daxx identifies a potential regulatory role of HSP27 in Fas-induced apoptosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;926:126–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Charette SJ, Lavoie JN, Lambert H, Landry J. Inhibition of Daxx-mediated apoptosis by heat shock protein 27. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7602–7612. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.20.7602-7612.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Souza RF, Shewmake K, Pearson S, Sarosi GA, Jr, Feagins LA, Ramirez RD, Terada LS, Spechler SJ. Acid increases proliferation via ERK and p38 MAPK-mediated increases in cyclooxygenase-2 in Barrett’s adenocarcinoma cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G743–G748. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00144.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Havasi A, Li Z, Wang Z, Martin JL, Botla V, Ruchalski K, Schwartz JH, Borkan SC. Hsp27 inhibits Bax activation and apoptosis via a PI3 kinase-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12305–12313. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801291200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyata S, Takemura G, Kosai K, Takahashi T, Esaki M, Li L, Kanamori H, Maruyama R, Goto K, Tsujimoto A, Takeyama T, Kawaguchi T, Ohno T, Nishigaki K, Fujiwara T, Fujiwara H, Minatoguchi S. Anti-Fas gene therapy prevents doxorubicin-induced acute cardiotoxicity through mechanisms independent of apoptosis. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:687–698. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.