Abstract

Glucocorticoids (GCs) are routinely believed to take effect through genomic mechanisms, which are also largely responsible for GCs’ side effects. Beneficial non-genomic effects of GCs have been reported as being independent of the genomic pathway. Here, we synthesized a new type of GCs, which took effect mainly via non-genomic mechanisms. Hydrocortisone was conjugated with glycine, lysine and phenylalanine to get a bigger molecular structure, which could hardly go through the cell membrane. Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory efficacy showed that hydrocortisone-conjugated glycine (HG) and lysine could inhibit neutrophil degranulation within 15 min. HG could inhibit IgE-mediated histamine release from mast cells via a non-genomic pathway, and rapidly alleviate allergic reaction. Luciferase reporter assay showed that HG would not activate the glucocorticoid response element within 30 min, which verified the rapid effects independent of the genomic pathway. The work proposes a novel insight into the development of novel GCs, and provides new tools for experimental study on non-genomic mechanisms.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00018-010-0526-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Glucocorticoids, Non-genomic, Neutrophil, Allergy, Mast cells

Introduction

Glucocorticoids (GCs) are widely used in clinical practice, including the management of inflammatory and allergic diseases. Genomic mechanisms of GCs are mediated primarily by the cytosolic glucocorticoid receptors through activation and repression of specific target genes, which normally need several hours to take effect. The ligand-activated receptor dimer activates gene expression by binding to specific DNA sequences (glucocorticoid response element, GRE) in the promoter regions of glucocorticoid-regulated genes, resulting in increased transcription of genes coding for anti-inflammatory proteins, including lipocortin-1 and neutral endopeptidase. In contrast to the regulation of these classical GREs, the repression of target genes is mediated by negative GREs (nGRE), composite GREs or by transrepression. It is assumed that transrepression of transcription factors such as AP-1 and NF-kappa B is the main mechanism by which GCs mediate their anti-inflammatory activity, whereas the side effects of GCs are mainly mediated by GR-DNA-interaction either by activation or by negative regulation of gene expression (reviewed in [1–6]). Administration by inhalation achieves an effective therapy in the airways with a concomitant low risk of unwanted local and systemic effects. However, it still could not eliminate the side effects via the same types of receptors. This discrepancy is the driving force for the intensive search for novel GCs with a better benefit–risk ratio compared to conventional GCs.

In addition to these classical “genomic” mechanisms, there is increasing recognition of alternative modalities of GCs’ action that are independent from modulating gene expression and for this reason defined as “non-genomic”, characterized by a rapid response [7, 8]. We have proposed for the first time that the member receptor-mediated rapid effects of GCs exist on mammalian neurons. Considerable attention has been focused on GCs’ non-genomic mechanisms. It has been reported that GCs could rapidly inhibit Lck and Fyn kinases in human lymphocytes to exert immunosuppressive effects via non-genomic mechanism [9, 10]. Our recent studies have shown that GCs could inhibit degranulation of mast cells and neutrophils, phagocytosis of macrophages via non-genomic mechanism, to exert immunosuppressive, anti-allergic and anti-inflammatory effects [11–14]. However, there have still been few reports about novel drugs based on the knowledge of GCs’ non-genomic effects.

Here, we synthesized a new type of GCs, which excluded the classical genomic effect, by a method of chemical modification of the traditional glucocorticoid molecule. Moreover, non-genomic effects of the new type of GCs on inflammatory and allergic reactions were investigated in vivo and in vitro. The findings provide a new way of development of novel GCs: traditional glucocorticoid molecule could be chemically modified to exhibit their pharmacological effects via non-genomic mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Structural identification of the new compounds

The 1H spectra were recorded at 500 MHz with a Bruker instrument, and reported with TMS as internal standard and CDCl3 as solvent. Chemical shifts (δ values) and coupling constant (J values) were given in ppm and Hz, respectively. ESI mass spectra were performed on an API-3000 LC-MS spectrometer.

Evaluation of degranulation of neutrophils

Isolation of neutrophils

Human neutrophils were isolated from peripheral venous blood of healthy donors, who had not received any medication for at least 2 weeks. By discontinuous percoll gradient technique as previously described [13], the final neutrophils were prepared to >97% purity by Wright’s staining and >97% viable by trypan blue exclusion.

Stimulation of neutrophils

The cells were resuspended in polypropylene tubes at 106/ml, and stimulated to degranulation by 10−6 M N-formyl-methionyl-leucylphenylalanine (fMLP) at 37°C. Right after 5 min of stimulation, the tubes were transferred into ice for 3 min and then centrifuged at 800 rpm. The supernatant was rapidly transferred into new tubes and kept at −20°C for marker assays.

Determination of myeloperoxidase release

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) was determined as a marker for neutrophils degranulation by enzymology methods [13, 15]. Assays were carried out in 96-well EIA plates. In each well, 75 μl samples of supernatant were added to an equal volume of TMB (Amresco, USA), kept at room temperature for 15 min and then stopped with 75 μl 0.18 M H2SO4. Optical density (OD) was measured at 450 nm with a reference of 405 nm on an ELx800 microplate reader.

Evaluation of allergic asthma severity

Allergic reaction model

Male Hartley guinea pigs (Second Military Medical University Central Animal Services, China) weighing 200 ± 25 g were sensitized by an injection of 0.5 ml of suspension (5 mg ovalbumin mixed with 50 mg aluminum hydroxide in saline, i.p.) plus 1 ml of suspension (10 mg ovalbumin in saline, i.m.). Then, 30 days later, animals were challenged to allergic asthma reaction with an aerosol of antigen (ovalbumin suspended in saline, 10 mg/ml) for 25 s [12]. In addition, the pulmonary function parameters were monitored continuously. Throughout our experiment, inhalations were performed by a Pari-Master nebulizer (Pari Respiratory Equipment, Germany) via a tracheal cannula. A single model of nebulizer was to control possible differences in drug delivery. All procedures were carried out in accordance with standard guidelines for the care of animals and were approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experiments of the Second Military Medical University.

Measurement of lung function

The lung function parameters, lung resistance (R L) and lung dynamic compliance (C dyn), were measured as previously described [11, 16]. After being anesthetized with urethane (500 mg/kg, i.p.) to maintain abolition of the corneal and withdrawal reflexes, the guinea pig was placed into a whole-body plethysmograph in a supine position. The trachea was cannulated just below the larynx through a tracheotomy, and a pleural cannula was inserted into the right pleural cavity. Tidal volume (V T) was derived from recordings of plethysmograph pressure detected by a pressure transducer; airflow was measured from a tracheal cannula connected to a pneumotachograph. Transpulmonary pressure was recorded using a second pressure transducer connected between the proximal end of the pleural cannula and the plethysmograph. All signals were recorded on a personal computer by using MedLab5.55 software (Nanjing MedEase Technology, China). R L and C dyn were calculated from the recordings of volume, flow, and pressure.

Measurement of histamine release from mast cells

Cell culture

The rat basophilic leukemia (RBL-2H3) mast cell line was obtained from Dr. Lin-Zhen Zhang (Changzheng Hospital, China). Monolayer cultures were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (Gibco BRL, USA) containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 45 mM sodium bicarbonate, and 5 mM l-glucose [17].

Sensitization and stimulation of mast cells

RBL-2H3 mast cells (1 × 105/ml) were sensitized with 250 ng/ml anti-dinitropheny (DNP) IgE at 37°C for 12 h, and the cells were washed to remove excess IgE, and stimulated with antigen (100 ng/ml DNP-HSA) to degranulation at 37°C [18].

Determination of histamine release

Histamine was measured fluorimetrically using the method of Kremzner and Wilson [19, 20]. In the supernatants, o-phthaldialdehyde was added directly to the sample after alkalinization with 0.4 M NaOH. The same procedure was used for the cells after extraction with 0.1 M HCl. Histamine release was expressed as a percentage of the total amount (remained in the cells plus supernatants). Spontaneous histamine release, less than 5%, was subtracted from all values.

GRE-luciferase reporter assay

Activation of GRE was test by GRE-luciferase reporter assay as previous described [21]. RBL-2H3 cells were seeded in 24-well culture plates (1 × 105/well) for 24 h. Cells were transiently transfected with 1 μg of MMTV-luc (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Normalization of transfection efficiency was done by cotransfection with 1 ng of pRL-TK Renilla reniformis luciferase plasmid (Promega). Then, 12 h after transfection, RBL-2H3 cells were cultured in the medium containing 10% FBS for 24 h, after which they were cultured in the medium supplemented with 5% charcoal-dextran-stripped calf bovine serum containing either 100 nM HH, HG or solvent control for different times. The Dual-Luciferase Reporter assay system (Promega) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were normalized for transfection efficiency by dividing firefly luciferase activity with that of Renilla luciferase.

Determination of cAMP levels in mast cells

RBL-2H3 mast cells were grown in 96-well plates. Normally, 106 cells in 1 ml of medium were seeded in each well and then were sensitized with 250 ng/ml anti-dinitropheny (DNP) IgE for 12 h. The cells were washed to remove excess IgE, then incubated with HG (10−4–10−7 M) or control for 7 min before challenge with antigen (100 ng/ml DNP-HSA). The reaction was stopped in ice. Thereafter, the cells were treated with 5% trichloroacetic acid solution, freeze-thawed three times, centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 15 min, and then the supernatants were collected for cAMP measurements. The cAMP levels were determined by using a cAMP [3H] assay system (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, MA, USA.), as described in the literature [22].

Acute toxicity studies

Kunming strain mice weighing 18–22 g were individually caged, and observed for health verification for 7 days prior to testing. For intravenous evaluation, five doses of HH, 813.0, 690.0, 588.0, 500.0 and 425.0 mg/kg body weight were administrated to five groups of ten animals (half male and half female) by tail vein injection, respectively. For intramuscular evaluation, five doses of HH, 1060.0, 901.0, 766.0, 651.0 and 535.0 mg/kg body weight were administrated to the five groups of ten animals (half male and half female) by intramuscular injection, respectively. The animals were carefully observed for any toxic effect and distribution of death rate, immediately after dosing, during the subsequent 14 days. At the end of the observational period, the animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. A thorough autopsy was carried out on all the animals for pathological examination. Median lethal dose (LD50) and 95% confidence limit were calculated according to the Bliss method [23].

Reagents and chemicals

Salts and other reagents were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise noted. fMLP were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide to a final concentration of 50 mM and 2.5 μg/μl, stored at −20°C and diluted in Krebs-Ringer phosphate buffer (KRP,130 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.27 mM MgCl2, 0.95 mM CaCl2, 5 mM glucose, 10 mM NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4, PH 7.4) just before use.

Data analysis

Each experimental point was performed in duplicate, and at least two independent experiments were carried out. Statistical analysis was performed on datasets using SAS software (SAS Institute, NC, USA). The significance of changes in the experimental variables measured was assessed by the t test for normally distributed data and the Wilcoxon test for the non-normally distributed data. A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Modification on traditional glucocorticoid molecule

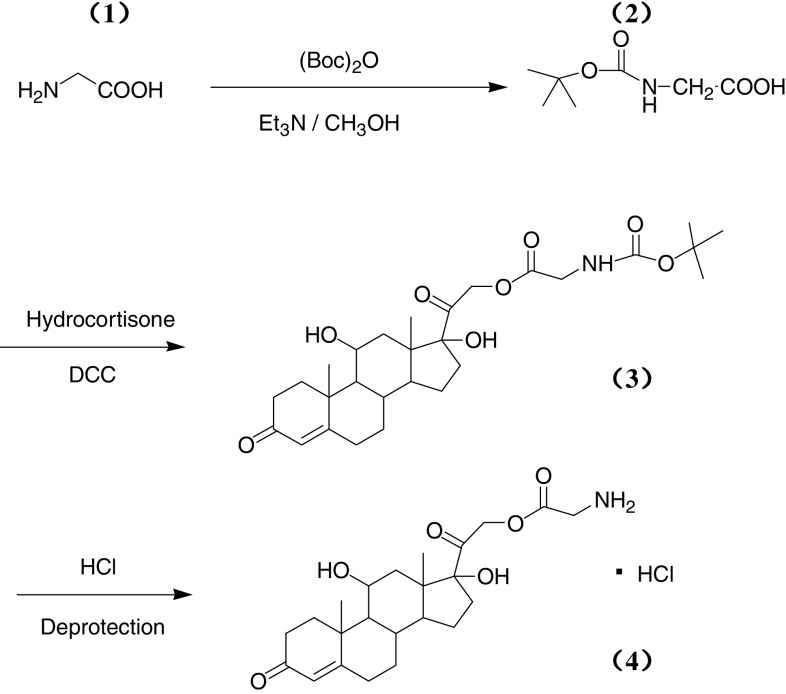

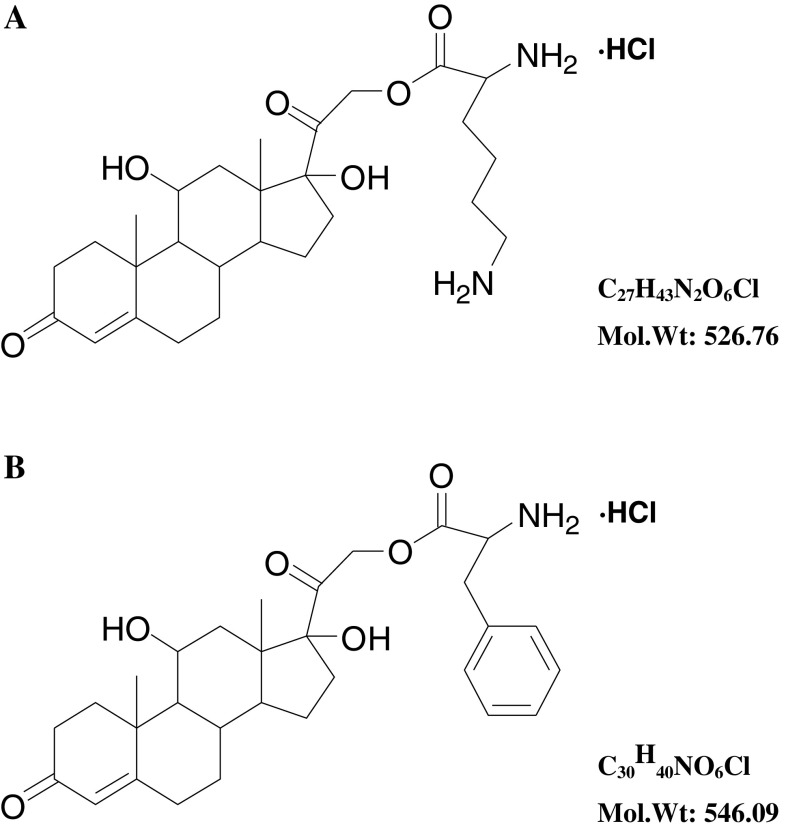

As shown in Fig. 1, N-tert-butoxycarbonyl-l-glycine (N-Boc-l-glycine) was obtained first. Glycine (1.87 g, 0.025 mol) (tert-butoxycarbonyl)2O (Boc2O, 10.90 g, 0.050 mol) and triethylamine aqueous solution (10%, 52 ml, 0.1 mol) were mixed and refluxed for 2.5 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated and the residue was treated with ice water (50 ml). PH value was adjusted to 3 with 1 M HCl. Then, the solution was extracted with ethyl acetate (50 ml × 3) and the organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuum, and the residue was crystallized from ether and petroleum (17 ml, 1:8) to get N-Boc-l-glycine as white solids (yield 91.7%). Then, N-tert-butoxycarbonyl-l-glycine-21-Hydrocortisone-ate (N-Boc-glycine-21-hydrocortisone-ate) was synthesized. Hydrocortisone (HH, 3.42 g), N-Boc-glycine (1.75 g) and N,N′- dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC, 2.15 g) were added to CH2Cl2 (100 ml) and stirred for 2 h at room temperature. The reaction mixture was filtered and the filtrate was extracted with ether. The organic layer was washed by 10% HCl and saturated Na2CO3, and then was dried over anhydrous MgSO4. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by chromatography on silica gel (hexane: ethyl: acetate, 1:1 and ethyl acetate) to make N-Boc-hydrocortisone-21-glycinate as white crystalline powder (4.19 g, 80.6%). N-Boc-hydrocortisone-21-glycinate (0.431 g, 0.83 mM) was dissolved in 10 mL CH2Cl2 and bubbling anhydrous HCl gas through the solution. The solid was precipitated from solution and removed by filtration. The process was repeated several times until no solid precipitated. The filtrate was crystallized in ether and afforded hydrocortisone-21-glycinate as white powder (0.069 g, 18.4%). Using the same method, hydrocortisone-2-lysine-ate (HL) and hydrocortisone-21-phenylalanine-ate (HP) were synthesized (Fig. 2), with lysine and phenylalanine as vectors, respectively. Structural identification of the new compounds was performed by 1H-NMR, and detailed data are shown in the Supplemental material.

Fig. 1.

Schematic presentation of the synthesis of HG. 1 Glycine, 2 N-Boc-glycine, 3 N-Boc-glycine-21-hydrocortisone-ate, and 4 Glycine-21-hydrocortisone–ate

Fig. 2.

Structural formula of HG (a) and phenylalanine (b)

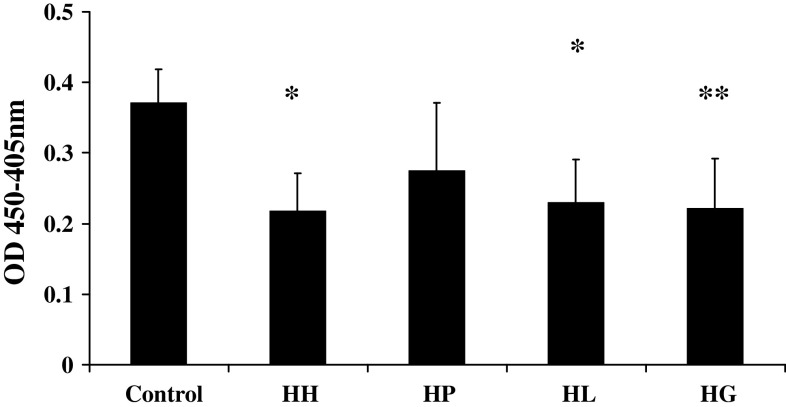

Primary evaluation of efficacy of the new type of GCs

To get a primary evaluation of the efficacy of the new type of GCs, we studied the rapid effects of the three derivatives on inflammatory reaction, with the model of human neutrophil degranulation. The human neutrophils were preincubated with HP, HL, HG or HH at 10−4 M for 7 min before fMLP challenge, respectively. After the cells were stimulated by fMLP for 5 min, the reaction was stopped by ice. Then, the marker of neutrophil degranulation, MPO release, was detected by enzymology methods. Solvent was used as control. The OD value of Control, HP, HL, HG and HH were 0.37 ± 0.05, 0.28 ± 0.10, 0.23 ± 0.06, 0.22 ± 0.05, and 0.22 ± 0.07% from four independent experiments performed in duplicate, respectively (Fig. 3). The results showed that HH (P < 0.05), HL (P < 0.05) and HG (P < 0.01) could inhibit fMLP-stimulated MPO release from human neutrophils within 15 min. There was no significant difference among HL, HG and HH groups. We chose HG as the representative of the new type of GCs in the subsequent study.

Fig. 3.

Rapid effects of the new type of GCs on human neutrophil degranulation. HH (P < 0.05), HL (P < 0.05) and HG (P < 0.01) could inhibit fMLP-stimulated MPO release from human neutrophils within 15 min. Data are expressed as means ± SE of four independent experiments performed in duplicate, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 in comparison with control group

Rapid effects of HG on allergic asthma reaction in guinea pig

To evaluate the rapid effect of the new type of GCs on allergic reaction, Hartley guinea pigs were administered HG or HH at 3 mg/ml by inhalation for 5 min before challenged to allergic reaction. The lung function parameters, lung resistance (R L) and dynamic lung compliance (C dyn), were monitored continuously. R L and C dyn reflected pulmonary function of large airway and small airway, respectively, and the attack of asthma was characterized with the increase of R L and decrease of C dyn [11, 24]. Moreover, the average maximum changes of R L (the highest value) and C dyn (the lowest value) were calculated, and expressed as ratios by comparing with R L and C dyn of the baseline in the same animal before antigen challenge, to evaluate the severity of allergic asthma. Solvent was used as control (n = 8). As shown in Table 1, inhaled HG or HH could also significantly inhibit decrease of R L and increase of C dyn in the asthma model of guinea pig within 10 min (P < 0.05). It suggested that the new type of GCs could rapidly inhibit allergic reaction, which precluded genomic-mediated responses that normally need several hours to occur. There was no significant difference between the HG and HH groups.

Table 1.

Rapid effects of HG on the changes of lung function in allergic reaction

| Group | Maximum changes of R L | Maximum changes of C dyn | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 4.41 ± 0.84 | 0.37 ± 0.06 | 8 |

| HH | 3.20 ± 0.81* | 0.60 ± 0.05* | 9 |

| HG | 2.31 ± 0.28* | 0.59 ± 0.05* | 11 |

Animals were inhaled HG or HH (3 mg/ml) for 5 min before challenged to allergic asthma by antigen, and solvent used as control. Lung functions were monitored continuously. The average maximum changes of R L (the highest value) and C dyn (the lowest value) were calculated, and expressed as ratios by comparing with R L and C dyn of the baseline in the same animal before antigen challenge, to evaluate the allergic asthma severity. Inhaled HG or HH could also significantly inhibited increase of R L and decrease of C dyn in asthma model of guinea pig within 10 min (P < 0.05).There was no significant difference between the HG and HH groups. Data are expressed as means ± SE

*P < 0.05 in comparison with control group

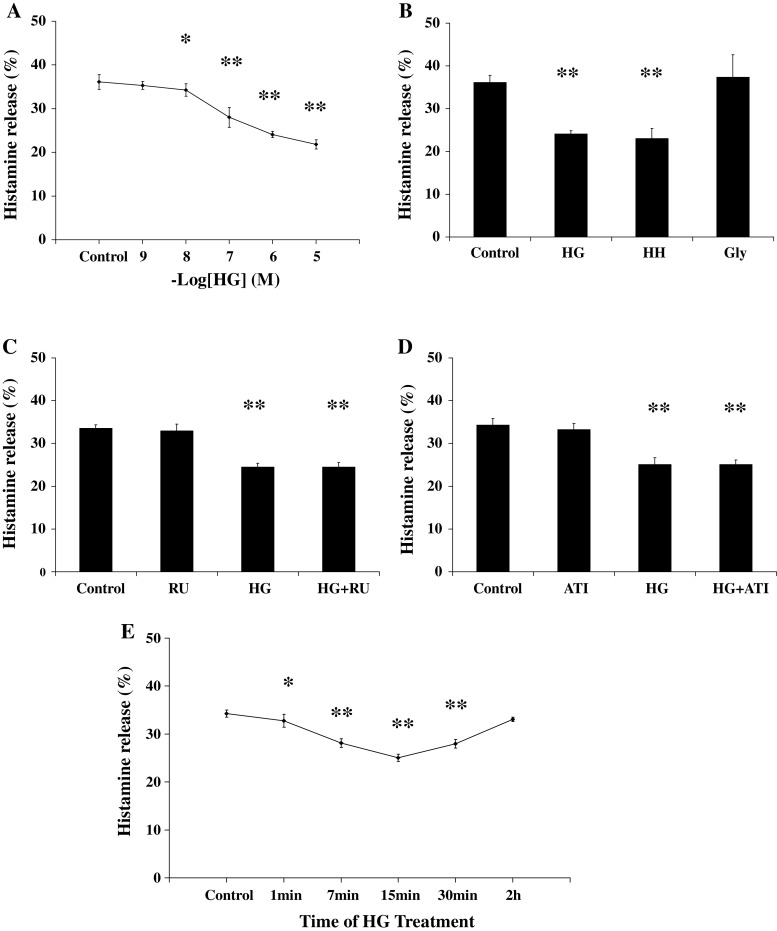

Non-genomic effects of HG on histamine release from mast cells

IgE-mediated release of inflammation mediator plays a crucial role in the attack of allergic reaction [25], and we investigated the rapid effects of the new type of GCs on IgE-mediated histamine release from mast cells in vitro. The RBL-2H3 mast cells were sensitized with anti-DNP IgE, and then incubated with HG at concentrations from 10−9 to 10−6 M for 7 min before antigen challenge. After mast cells were stimulated by antigen for 8 min, the reaction was stopped in ice. Then, histamine release was detected. Solvent was used as control. The histamine release percentage of Control, HG 10−9 M, HG 10−8 M, HG 10−7 M, HG 10−6 M and HG 10−5 M were 36.09 ± 1.70, 35.30 ± 1.07, 34.26 ± 0.73, 28.00 ± 2.26, 24.10 ± 1.41 and 21.82 ± 0.89%, respectively, from seven independent experiments (Fig. 4a). The results showed that HG at 10−8–10−5 M could inhibit IgE-mediated histamine release from RBL-2H3 mast cells within 15 min (P < 0.05). As the concentration of corticosterone increasing, the percentage of inhibition on histamine release was also gradually enhanced.

Fig. 4.

Non-genomic effects of HG on histamine release from mast cells. a Dose–response curve of HG’s rapid inhibition on histamine release of mast cells. HG could inhibit histamine release in dose-dependent manner within 15 min. b Summary of histamine release percentage of Control, HG (10−7 M), HH (10−7 M), and Gly (10−7 M). Glycine could not inhibit the histamine release itself. c Summary of histamine release percentage of Control, HG (10−7 M), RU (RU486, 10−6 M), and HG (10−7 M) + RU (10−6 M). RU486 could not block the rapid inhibitory effects of HG. d Summary of histamine release percentage of Control, ATI (Actidione, 10−4 M), HG (10−7 M), and HG (10−7 M) + ATI (10−4 M). Actidione could not block the rapid inhibitory effects of HG. e Time-course curve of HG’s inhibition on histamine release. Data are expressed as means ± SD of histamine release percentage. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 in comparison with control group

To exclude the possibility that the observed effects due to the amino acid residues, we studied whether the glycine itself could inhibit histamine release of mast cells. The sensitized RBL-2H3 mast cells were incubated with HG, HH, or glycine at 10−7 M for 7 min before antigen challenge. Solvent was used as control. As shown in Fig. 4b, Both HG and HH could inhibit antigen-induced histamine release of mast cells within 15 min. Moreover, the rapid inhibition was not found in the glycine-pretreated group, which excluded the possibility that the observed effects are due to the amino acid residues.

We carried out a second series of experiments to assess the non-genomic mechanism involved in the GCs’ rapid effects. Mifepristone (RU486) is an antagonist of classic glucocorticoid receptor, which could exclude the traditional genomic mechanism mediated by glucocorticoid receptor [12, 26, 27]. The sensitized cells were preincubated with RU486 at 10−6 M for 30 min, and then incubated with HG (10−7 M) for 7 min before antigen was added. Solvent was used as control. The histamine release percentage of Control, RU, HG, and HG + RU were 33.51 ± 0.88, 32.92 ± 1.59 24.45 ± 0.92 and 24.46 ± 1.04%, respectively, from seven independent experiments performed in duplicate (Fig. 4c). The results showed that RU486 could not block the rapid inhibitory effect of HG on IgE-mediated histamine release from mast cells. It suggested that glucocorticoid receptor pathway was not involved in rapid effects of the new type of GCs.

To confirm the non-genomic mechanisms involved in the effects of HG, we studied the influence of actidione (ATI) on the rapid effect of HG. ATI is the protein synthesis inhibitor, which could block the protein synthesis by genomic mechanism pathway [8, 26, 28]. The sensitized cells were preincubated with ATI (10−4 M) for 3 h, and then incubated with HG (10−7 M) for 7 min before antigen added. Solvent was used as control. The histamine release percentage of Control, ATI, HG, and HG + ATI were 34.31 ± 1.51, 33.23 ± 1.42, 25.06 ± 1.61, and 25.08 ± 1.10%, respectively, from seven independent experiments performed in duplicate (Fig. 4d). The results showed that ATI could not block the rapid inhibitory effects of HG on IgE-mediated histamine release from mast cells. It suggested that the rapid effect of the new type of GCs was independent from the protein synthesis, which verified the existence of the non-genomic mechanism.

We further examined the time-course of HG’s effect. The sensitized cells were incubated with HG (10−7 M) for various times before antigen was added. The histamine release percentage of GCs’ incubation by 1, 7, 15, 30 min, 2 h and Control were 32.75 ± 1.33, 28.08 ± 0.91, 25.06 ± 0.76, 27.95 ± 0.89, 33.06 ± 0.45, and 34.25 ± 0.72%, respectively, from seven independent experiments performed in duplicate (Fig. 4e). A significant decrease of histamine release was detected from 7 min of GCs’ incubation, and peaked at 15 min. However, HG’s inhibition decreased with 30 min incubation, and was weaker with 2 h incubation.

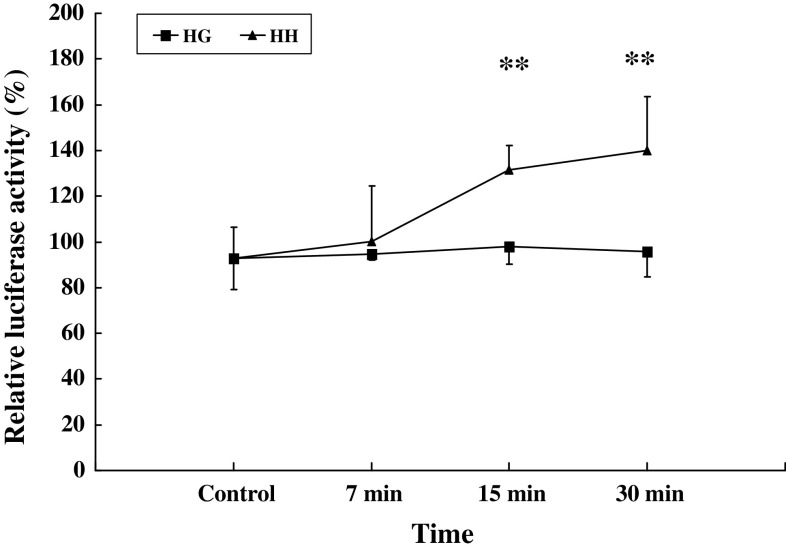

Rapid effect of HG was not mediated by classical GR pathway

GRE-luciferase reporter assay was widely used to assess the activation of the classical glucocorticoid receptor pathway. To check whether HG act via genomic mechanisms, we determined the activation of GRE by GRE-luciferase reporter assay. The sensitized RBL-2H3 cells were treated with 10−7 M HH and HG at various times. Solvent was used as control. At 7, 15 and 30 min, the induction of GRE-luciferase expression by HH were 1.00 ± 0.24, 1.32 ± 0.11, 1.40 ± 0.23, 0.93 ± 0.14, and by HG were 0.95 ± 0.03, 0.98 ± 0.08, 0.96 ± 0.11, 0.93 ± 0.14, respectively, (Fig. 5). The result showed that GRE could be partly activated by HH from 15 min, and the activation was not found in HG for 30 min, which verified that HG’s rapid effects were independent of classical glucocorticoid receptor pathway.

Fig. 5.

Rapid effect of HG and HH on activation of GRE. RBL-2H3 cells (1 × 105) were transiently co-transfected with 1 μg MMTV-Luc, 1 ng of pRL-TK Renilla reniformis luciferase plasmid as control. Transfected cells were treated with or without 100 nM HH, HG or solvent control for 7, 15 and 30 min. The ratios of firefly to R. reniformis Luc activities were calculated to correct for differences in transfection efficiency. The average ratio of the untreated control group was used to calculate the percentage of change in the reporter activity of treated groups, and results are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3 each). HH **P < 0.01 in comparison with control group

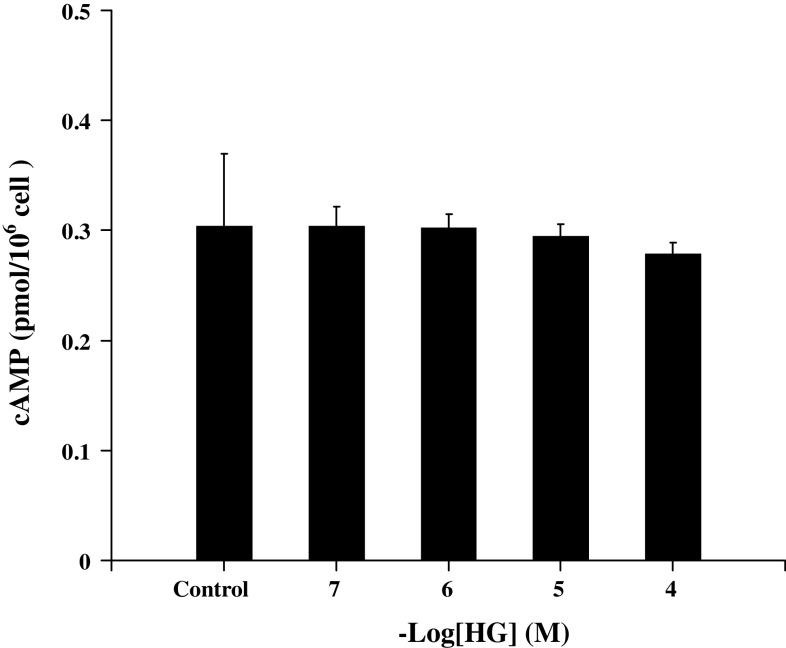

cAMP was not involved in the rapid effect of HG on mast cells

cAMP is also an important second messenger involved in the degranulation of mast cells. We also studied the rapid effect of HG on intracellular cAMP levels in mast cells. The sensitized RBL-2H3 mast cells were incubated with HG at concentrations from 10−7 to 10−4 M for 7 min before antigen challenge. Solvent was used as control. As shown in Fig. 6, there was no significant difference in cAMP levels between HG (10−4–10−7 M) pretreatment and control group. It suggested that cAMP was not the key signal in the GCs’ rapid effect on degranulation of mast cells.

Fig. 6.

Influence of HG on intracellular cAMP levels in mast cells. The sensitized mast cells were incubated with 10−4–10−7 M HG or solvent control for 7 min at 37°C, and then the reaction was terminated by ice-bath. The cAMP levels were measured by using a cAMP [3H] assay system. Data are expressed as means ± SD (n = 5 each)

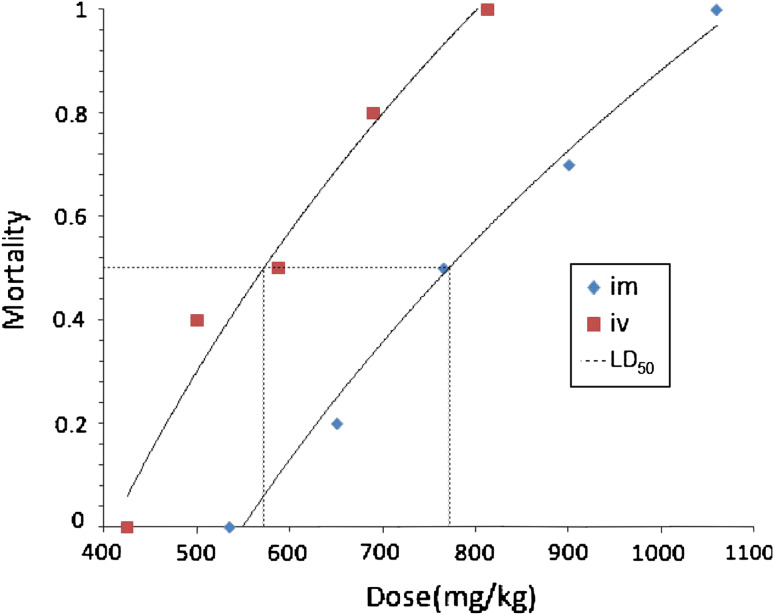

Acute toxicity studies

We examined the safety profile of HG in further detail. The acute toxicity evaluation in mice showed that there was a regular dose-dependent increase in mortality in both sexes of mice after administration. In addition to death, the toxicities included hair-floppy, inactivity and loss of weight. The autopsy of the treated animals did not reveal any macroscopic changes in major organ, such as heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney. As shown in Fig. 7, the LD50 value and 95% confidence limits of HG administrated by i.v. and i.m. were calculated as 567.8 (518.3–621.9) mg/kg and 776.5 (710.1–849.1) mg/kg, respectively, which indicated that HG was a compound with low toxicity.

Fig. 7.

Acute toxicity studies of HG on mice by i.v. and i.m. Groups of 10 mice each were administrated with different concentrations of HG by i.v. and i.m. The calculated median lethal dose (LD50) were 567.8 mg/kg and 776.5 mg/kg, respectively

Discussion

GCs are potent anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressant agents available. Over the past six decades, it has been widely assumed that GCs work solely through regulating gene expression. Nowadays, the non-genomic mechanism of GCs’ rapid action has attracted more and more attention [29–32]. It is clear that GCs can modulate immune reaction, neuronal excitability, behavior and so on, within seconds or minutes via non-genomic pathways. The non-genomic effects could be mediated by at least three mechanisms: (1) physicochemical interactions with cellular membranes (non-specific non-genomic effects); (2) cytosolic glucocorticoid receptor (cGCR)-mediated non-genomic effects; and (3) membrane-bound glucocorticoid receptor (mGCR)-mediated non-genomic effects [33–37]. We have reported that, in neurons and pituitary cells, GCs might act on putative membrane receptors, via the PTX-sensitive-G protein-PKC pathway and the PKA pathway to induce a variety of intracellular responses [38, 39].

Beneficial rapid non-genomic effects of glucocorticoid have been reported in the treatment of allergic disease. Tillmann reported acute non-genomic action of GCs in seasonal allergic rhinitis [40]. Rapid effects of GCs on immune reaction via non-genomic mechanism provide us with a new strategy for development of novel drugs [41]. Here, we propose a new approach to development of novel GCs: a traditional glucocorticoid molecule is conjugated to a macromolecule to exclude the classical genomic effect and retain the rapid non-genomic effect.

As one of the typical representatives of GCs-conjugated macromolecule, corticosterone-conjugated bovine-serum albumin (GC-BSA) has been used as a useful tool for studying non-genomic effects, which could mimick the rapid effects of GCs but could not go through the cell membrane [31, 32]. Nevertheless, GC-BSA has too high a molecular weight and too low solubility, and therefore could be used only in experimental studies but not as clinical drugs. In this study, we chose amino acids conjugated with GCs to make the products more soluble with a bigger molecular structure. In addition, amino acids as vector might ameliorate absorption, distribution, and excretion of the products. With the glycine, lysine and phenylalanine as vector, we got three new compounds: HG, HL, and HP.

To get a primary evaluation of efficacy of the new type of GCs, the rapid effects on inflammatory reaction were studied after structure identification. The results showed that HG and HL could rapidly inhibit release of inflammatory mediator from human neutrophils. Moreover, we investigated rapid non-genomic effects of HG on allergic reaction in vivo and in vitro. HG could inhibit IgE-mediated histamine release from mast cells via non-genomic pathway, and rapidly alleviate allergic asthma reaction in animal models. RU486 could not block HG’s rapid inhibition on histamine release from mast cells, and activation of GRE was not found by HG for 30 min, which suggested that HG’s rapid effect was not mediated by classical glucocorticoid receptor pathway. It was vital to clarify the signal transduction pathway involved in GCs’ rapid effect. Our previous studies have shown that GCs could significantly inhibit the raise of [Ca2+]i induced by antigen and cause a similar degree of reduction in exocytosis. By the employment of well-controlled Ca2+ stimulation generated by intracellular photolysis of caged-Ca2+, we verified modulation of Ca2+ signaling might play an key role in the non-genomic action of GCs [12]. Regrettably, the study showed that cAMP was not involved in the rapid effect of the novel GCs (HG). Further study on other signals in activation of mast cells (such as Syk) would provide more information on the non-genomic mechanism.

In our experiment, the novel GCs could take non-genomic effects at the minimum concentration 10−8 M (Fig. 4a), which is close to the GCs’ physiological concentration in stress in vivo [42, 43]. It indicates that GCs’ non-genomic effects might play an important role in modulating stress and immune response. In addition, the minimum concentration was quite low as compared to the LD50 value, about 1.46 × 10−2 M in molar terms, which is estimated from the weight per kg of acute toxicity assays (567.8 mg/kg) and the estimated blood volume per kg of mice [44] and molecular weight of HG (457.0). It also indicates that the novel GCs are relevant for possible use as drugs. Pharmacokinetics studies of the novel GCs are ongoing in our laboratory to give more information on a new formulation for treatment.

The work proposes novel insight into the development of GCs, and the synthesized derivatives, GCs conjugated amino acids, also provide us with new tools for experimental study on non-genomic mechanisms, which have better solubility compared with previous reagents. The new type of GCs is very promising as a prodrug; however, many questions remain. The huge potential of them in reducing the systemic side effects has not been fully investigated. Further studies might raise the possibility of new therapeutic strategies for inflammatory and allergic diseases.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgment

The work was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (30873077 and 30700344), Shanghai Basic Research Foundation (08JC1404900), Natural Science and Technology Major Project (2009ZX09303002), and Mental Health Program (2010).

Abbreviations

- GCs

Glucocorticoids

- GRE

Glucocorticoid response element

- HH

Hydrocortisone

- HG

Hydrocortisone-conjugated glycine

- HL

Hydrocortisone-conjugated lysine

- HP

Hydrocortisone-conjugated phenylalanine

- RU486

Mifepristone

- ATI

Actidione

- fMLP

N-Formyl-methionyl-leucylphenylalanine

- MPO

Myeloperoxidase

- RL

Lung resistance

- Cdyn

Lung dynamic compliance

- RBL-2H3 cell

Rat basophilic leukemia mast cell

- Boc

Tert-butoxycarbonyl

- MMTV-Luc

Mouse mammary tumor virus-luciferase

- cAMP

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

Footnotes

J. Zhou and M. Li contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Baschant U, Tuckermann J. The role of the glucocorticoid receptor in inflammation and immunity. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;120:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Bosscher K, Haegeman G. Minireview: latest perspectives on antiinflammatory actions of glucocorticoids. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:281–291. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stahn C, Buttgereit F. Genomic and nongenomic effects of glucocorticoids. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:525–533. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dostert A, Heinzel T. Negative glucocorticoid receptor response elements and their role in glucocorticoid action. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:2807–2816. doi: 10.2174/1381612043383601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Bosscher K, Vanden Berghe W, Haegeman G. The interplay between the glucocorticoid receptor and nuclear factor-kappaB or activator protein-1: molecular mechanisms for gene repression. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:488–522. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnes PJ. Anti-inflammatory actions of glucocorticoids: molecular mechanisms. Clin Sci (Lond) 1998;94:557–572. doi: 10.1042/cs0940557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipworth BJ. Therapeutic implications of non-genomic glucocorticoid activity. Lancet. 2000;356:87–89. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02463-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lose R, Wehling M. Nongenomic actions of steroid hormones. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:46–56. doi: 10.1038/nrm1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hua SY, Chen YZ. Membrane receptor-mediated electrophysiological effects of glucocorticoid on mammalian neurons. Endocrinology. 1989;124:687–691. doi: 10.1210/endo-124-2-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Löwenberg M, Tuynman J, Bilderbeek J, Gaber T, Buttgereit F, van Deventer S, Peppelenbosch M, Hommes D. Rapid immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids mediated through Lck and Fyn. Blood. 2005;106:1703–1710. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou J, Kang ZM, Xie QM, Liu C, Lou SJ, Chen YZ, Jiang CL. Rapid nongenomic effects of glucocorticoids on allergic asthma reaction in the guinea pig. J Endocrinol. 2003;177:R1–R4. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.177R001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou J, Liu DF, Liu C, Kang ZM, Shen XH, Chen YZ, Xu T, Jiang CL. Glucocorticoids inhibit degranulation of mast cells in allergic asthma via nongenomic mechanism. Allergy. 2008;63:1177–1185. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu L, Wang YX, Zhou J, Long F, Sun HW, Liu Y, Chen YZ, Jiang CL. Rapid non-genomic inhibitory effects of glucocorticoids on human neutrophil degranulation. Inflamm Res. 2005;54:37–41. doi: 10.1007/s00011-004-1320-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Long F, Wang YX, Liu L, Zhou J, Cui RY, Jiang CL. Rapid nongenomic inhibitory effects of glucocorticoids on phagocytosis and superoxide anion production by macrophages. Steroids. 2005;70:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borregaard N, Cowland JB. Granules of the human neutrophilic polymorphonuclear leukocyte. Blood. 1997;89:3503–3521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laude EA, Emery CJ, Suvarna SK, Morcos SK. The effect of antihistamine, endothelin antagonist and corticosteroid prophylaxis on contrast media induced bronchospasm. Br J Radiol. 1999;72:1058–1063. doi: 10.1259/bjr.72.863.10700821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arthur JF, Shen Y, Kahn ML, Berndt MC, Andrews RK, Gardiner EE. Ligand binding rapidly induces disulfide-dependent dimerization of glycoprotein VI on the platelet plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30434–30441. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701330200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jolly PS, Bektas M, Watterson KR, Sankala H, Payne SG, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Expression of SphK1 impairs degranulation and motility of RBL-2H3 mast cells by desensitizing S1P receptors. Blood. 2005;105:4736–4742. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu C, Zhou J, Zhang LD, Wang YX, Kang ZM, Chen YZ, Jiang CL. Rapid inhibitory effect of corticosterone on histamine release from rat peritoneal mast cells. Horm Metab Res. 2007;39:273–277. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kremzner LT, Wilson IB. A procedure for the determination of histamine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1961;50:365–367. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(61)90339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen YX, Li ZB, Diao F, Cao DM, Fu CC, Lu J. Up-regulation of RhoB by glucocorticoids and its effects on the cell proliferation and NF-kappaB transcriptional activity. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;101:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi YH, Yan GH, Chai OH, Zhang X, Lim JM, Kim JH, Lee MS, Han EH, Kim HT, Song CH. Inhibitory effects of Agaricus blazei on mast cell-mediated anaphylaxis-like reactions. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29:1366–1371. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bliss CI. The method of probits. Science. 1934;79:38–39. doi: 10.1126/science.79.2037.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie QM, Zeng LH, Zheng YX, Lu YB, Yang QH. Bronchodilating effects of bambuterol on bronchoconstriction in guinea pigs. Zhongguo Yao Li Xue Bao. 1999;20:651–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Broide D. New perspectives on mechanisms underlying chronic allergic inflammation and asthma in 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hafezi-Moghadam A, Simoncini T, Yang Z, Limbourg FP, Plumier JC, Rebsamen MC, Hsieh CM, Chui DS, Thomas KL, Prorock AJ, Laubach VE, Moskowitz MA, French BA, Ley K, Liao JK. Acute cardiovascular protective effects of corticosteroids are mediated by non-transcriptional activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nat Med. 2002;8:473–479. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Long F, Wang Y, Qi HH, Zhou X, Jin XQ. Rapid non-genomic effects of glucocorticoids on oxidative stress in a guinea pig model of asthma. Respirology. 2008;13:227–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roy B, Rai U. Genomic and non-genomic effect of cortisol on phagocytosis in freshwater teleost Channa punctatus: an in vitro study. Steroids. 2009;74:449–455. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di S, Maxson MM, Franco A, Tasker JG. Glucocorticoids regulate glutamate and GABA synapse-specific retrograde transmission via divergent nongenomic signaling pathways. J Neurosci. 2009;29:393–401. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4546-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghosh MC, Baatar D, Collins G, Carter A, Indig F, Biragyn A, Taub DD. Dexamethasone augments CXCR4-mediated signaling in resting human T cells via the activation of the Src kinase Lck. Blood. 2009;113:575–584. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-151803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borski RJ. Nongenomic membrane actions of glucocorticoids in vertebrates. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2000;11:427–436. doi: 10.1016/S1043-2760(00)00325-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di S, Malcher-Lopes R, Halmos KC, Tasker JG. Nongenomic glucocorticoid inhibition via endocannabinoid release in the hypothalamus: a fast feedback mechanism. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4850–4857. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-04850.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maier C, Rünzler D, Schindelar J, Grabner G, Waldhäusl W, Köhler G, Luger A. G-protein-coupled glucocorticoid receptors on the pituitary cell membrane. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3353–3361. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buttgereit F, Scheffold A. Rapid glucocorticoid effects on immune cells. Steroids. 2002;67:529–534. doi: 10.1016/S0039-128X(01)00171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Croxtall JD, Choudhury Q, Flower RJ. Glucocorticoids act within minutes to inhibit recruitment of signalling actors to activated EGF receptors through a receptor-dependent, transcription-independent mechanism. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:289–298. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartholome B, Spies CM, Gaber T, Schuchmann S, Berki T, Kunkel D, Bienert M, Radbruch A, Burmester GR, Lauster R, Scheffold A, Buttgereit F. Membrane glucocorticoid receptors (mGCR) are expressed in normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and up-regulated after in nitro stimulation and in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. FASEB J. 2004;18:70–80. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0328com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song IH, Buttgereit F. Non-genomic glucocorticoid effects to provide the basis for new drug developments. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;246:142–146. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qiu J, Wang CG, Huang XY, Chen YZ. Nongenomic mechanism of glucocorticoid inhibition of bradykinin-induced calcium influx in PC12 cells: possible involvement of protein kinase C. Life Sci. 2003;72:2533–2542. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(03)00168-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen YZ, Qiu J. Pleiotropic signaling pathways in rapid, nongenomic action of glucocorticoid. Mol Cell Biol Res Commun. 1999;2:145–149. doi: 10.1006/mcbr.1999.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tillmann HC, Stuck BA, Feuring M, Rossol-Haseroth K, Tran BM, Lösel R, Schmidt BM, Hörmann K, Wehling M, Schultz A. Delayed genomic and acute nongenomic action of glucocorticosteroids in seasonal allergic rhinitis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2004;34:67–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2004.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Löwenberg M, Stahn C, Hommes DW, Buttgereit F. Novel insights into mechanisms of glucocorticoid action and the development of new glucocorticoid receptor ligands. Steroids. 2008;73:1025–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones MT, Hillhouse EW, Burden JL. Dynamics and mechanics of corticosteroid feedback at the hypothalamus and anterior pituitary gland. J Endocrinol. 1977;73:405–417. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0730405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yeh KY. Corticosterone concentrations in the serum and milk of lactating rats: parallel changes after induced stress. Endocrinology. 1984;115:1364–1370. doi: 10.1210/endo-115-4-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davies B, Morris T. Physiological parameters in laboratory animals and humans. Pharm Res. 1993;10:1093–1095. doi: 10.1023/A:1018943613122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.