Abstract

The transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) superfamily of proteins and their receptors are crucial developmental factors for all metazoan organisms. Cystine-knot (CK) motif is a spatial feature of the TGFβ superfamily of proteins whereas the extra-cellular domains (ectodomains) of their respective receptors form three-fingered protein domain (TFPD), both stabilized by tight cystine networks. Analyses of multiple sequence alignments of these two domains encoded in various genomes revealed that the cystines forming the CK and TFPD folds are conserved, whereas the remaining polypeptide patches are diversified. Orthologues of the human TGFβs and their respective receptors expressed in diverse vertebrates retain high sequence conservation. Examination of 3D structures of various TGFβ factors bound to their receptors have revealed that the CK and TFPD domains display several similar spatial traits suggesting that these two different protein folds might have been acquired from a common ancestor.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00018-011-0643-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cystine knot, Cystine network, Three-fingered protein domain, TGFβ, Growth factors, Ly6

Introduction

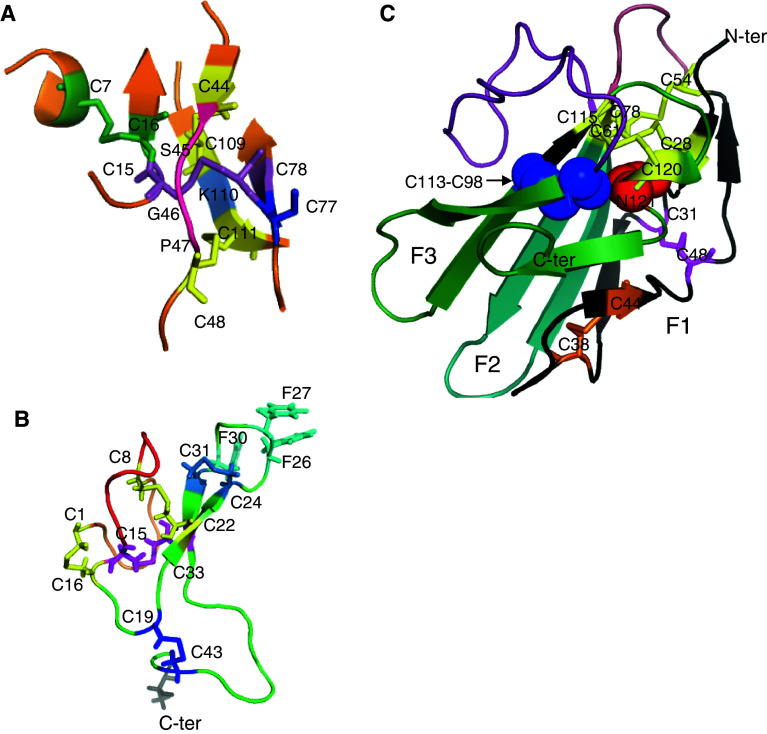

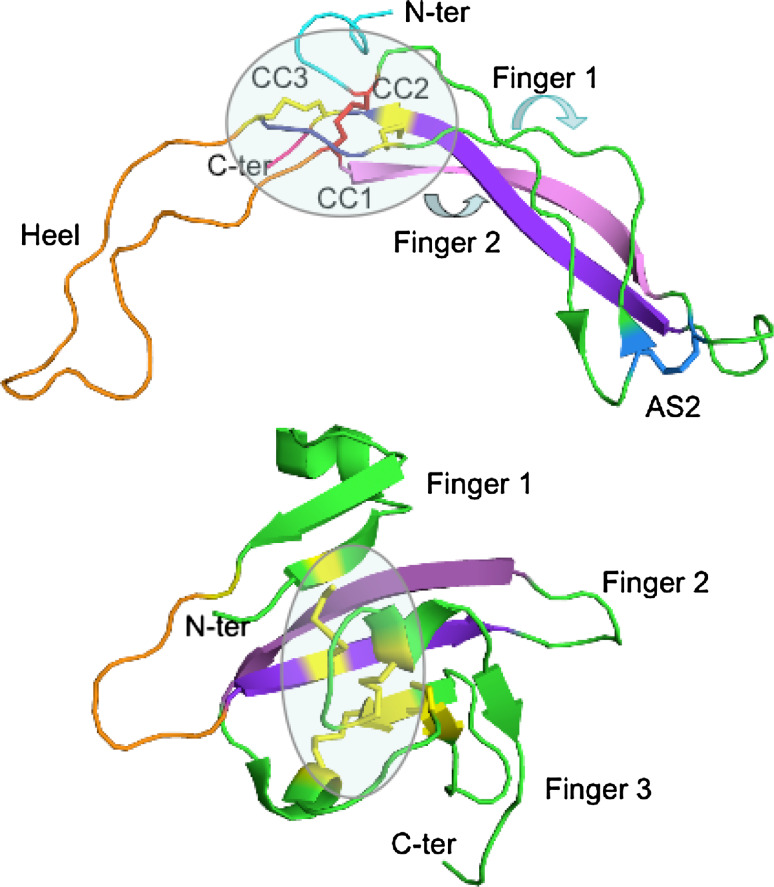

Members of the transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) superfamily of proteins [1] are crucial morphogens secreted during various developmental stages of all metazoan organisms and are key factors in the genesis of some diseases [1, 2]. Although the diverse TGFβ superfamily members and their antagonists [3] may have from 6–12 Cys residues, only six of them are highly conserved and essential to the unique spatial configuration of the disulfide (SS) bonds, also known as the cystine knot (CK) motif [4]. A great majority of the TGFβs, and some of their antagonists, contain one Cys residue able to form an intermolecular disulfide bond that gives rise to homo- and heterodimers [1]. A typical CK spatial motif is shown in Fig. 1a where two of the three intramolecular SS bonds make a macrocycle (cyclic peptide formed via two disulfide bridges) consisting of 8–10 amino acid (AA) residues [5, 6], which is wide enough so that the third disulfide passes through the macrocycle (CK spatial hallmark). Several other groups of proteins contain the CK motif [3], including some cyclic peptides produced by certain types of plants [9, 10].

Fig. 1.

CK, ICK, and TFPD spatial motifs extracted from the structure of TGFβ3 bound to TGFβ-IIR/TGFβ-IR ternary complex (2PYJ.pdb) [7], the human agouti-related protein (1HYK.pdb) [8], and the X-ray structure of the human TGFβ-RII ectodomain/TGF-β3 complex (1KTZ) [16], respectively. a The presented CK spatial motif is an eight-member cycle formed with C44 linked to C48 via S45-G46-P47 triad (red) whereas C48 forms an SS bond with C111 (yellow) that is linked to C109 via K110 (light blue) and which form an SS bond with C44 (yellow); the SS bond C15–C78 (violet) passes through the cycle (knotted SS bond). The additional SS bond (C7–C16) prolongs the ‘knotted SS bond’ (SS_KB) while C77 (blue) may form an intermolecular SS bond (homo- or heterodimer); b the ICK spatial motif in the structure of the human agouti-related protein forms a cystine stack made with the following three SS bonds: C1–C16 and C8–C22 (yellow) surrounding the threading SS bond formed with C15–C33 (violet); C1 is linked to C8 with the sequence VRLHES (wheat) whereas C8 is linked to C16 with the sequence LGQQV (orange) while the remaining two other SS bonds (C19–C43 and C24–C31 in blue) are outside the ICK motif; c the tight Cys network at the base of the palm is made of three SS bonds (C28–C61, C54–C78, and C115–C120, yellow sticks) and C113–C98 (blue sphere) which is at a distance longer than 7.5 Å from to the three SS bonds; C31–C48 (pink sticks) and C38–C44 (orange sticks are in Finger 1c and do not contribute to the stability of the principal Cys network; there is highly conserved N residue (N121, red sphere) in all the TFPDs [12]

Inhibitor cystine knot (ICK) [4] is a spatial feature of some short polypeptides produced by diverse plants and venomous invertebrates [10]. It has been shown that the ICK-like motif is a feature of the 3D structures of several human proteins, namely cocaine and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) [11], or the agouti signaling protein (ASIP) [8] that binds to melanocortin-1 receptor (G protein-coupled receptor, GPCR). ASIP and its homologue, agouti-related protein, are endogenous antagonists of melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH). The ICK motif differs, however, from the CK motif present in the TGFβ superfamily of proteins since there is different spatial connectivity of the S–S bonds [4], namely in the ICK fold, one of the disulfide bonds threads through the entire molecule and creates a cruciform-like spatial stack with the remaining two disulfides being in a short van der Waals distance from each other (see Fig. 1b).

A great majority of the TGFβ superfamily members interact with the extracellular domain (ECD) of their receptors which display the three-fingered protein domain (TFPD) fold [12] that has been first established from X-ray structures of neurotoxins isolated from venoms of sea snakes [13, 14]. Figure 1c shows the X-ray structure of the ECD of TGFβ-RII (TFP domain) bound to TGFβ3 [15]. Each TFPD contains a tight Cys network, known also as the palm, from which emerge three fingers (F1–F3) roughly pointing in the same direction. Only three SS bonds (yellow sticks) are in a short van der Waals distance from each other whereas the fourth SS bond (blue sphere) is outside the network. The palm is stabilized by a tight interaction cluster of AA residues being at the N- and C-terminal region with its highly conserved glutamine (red sphere) at the C-terminus of the TFPD [15]. Although proteins consisting of the CK and ICK folds are expressed in plants [9, 10], cone snails (conotoxins), spiders’ venom glands, and in higher animals [16], proteins consisting of the TFPD fold were only found in diverse metazoan organisms [17]. Some viral genomes, however, encode the proteins that have the TFPD fold. Namely the genome of Saimiriine herpes virus 2 contains a coding segment for homologue of CD59 [17], whereas the VHv1.1 protein (CK fold) is expressed by polydnaviruses injected by the Campoletis sonorensis wasp to Heliothis virescences larvae [18].

BLAST searches of the non-redundant protein sequence database assembled at the National Centre of Biotechnology Information (NCBI) [19] revealed that TGFβ-like proteins are encoded in different genomes including mammals, diverse sea animals, and various invertebrates such as the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, and the fly Drosophila melanogaster. Analyses of different combinations of multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) of various members of the TGFβ superfamily of proteins and their respective receptors encoded in different genomes, and comparisons made between bi-dimensional intramolecular interaction maps generated from the 3D structures of complexes comprising the ectodomains of various TFPDs [10] and their functional ligands, have revealed that these two domains have several similar spatial traits that may indicate their common ancestral source. Some functional features and interaction patterns of the TGFβs are also discussed.

Materials and methods

Databases used and data processing

The databases assembled in the NCBI (http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) [19] were used. The non-redundant GenBank coding sequences database (NrG_CSD) containing more than 12,000,000 entries was searched with the BLAST program [20] against all 36 paralogues of the human TGFβ1 (NP_000651) and seven homologues of the human Cerberus 1 (NP_005445). BLAST searches performed at a low stringency did not pull out all the human homologues of TGFβ1 from the Human Genomic Database (see supplemental data, Blast.out) that is due to relatively low overall sequence similarity in his superfamily of proteins. Each pack of sequences found with the BLAST program were downloaded from the NCBI server in the GenPept format and processed as described below.

The human genomic database (37794 sequences; 17092924 AA residues; April 2009) [19] was used in searches for cysteine sequence motifs. The genomic database was converted by a home-made database processing program (author AG) into two files, namely one containing some fundamental sequence attributes such as nominal molecular mass (kDa), pI and overall hydrophobicity, whereas the other one stored the sequences. A suite of Fortran 77 programs was written for rapid searches of the transformed databases for the presence of diverse sequence motifs comprising Cys residues. Analyses of cysteine residues distribution occurring in the MSAs of various CK motif-containing proteins suggested that the following patterns could be used for searching the genomic databases: in the {CC} parentheses is shown the main motif from which upstream and downstream Cys residues are spaced with given number of AA residues (a), where (a) is any of the 20 natural amino acids. (1) TGFβ-like proteins: [C(19-30a){C(3a)C}(29-37a)C(a)C)] whereas [C(11-14a){CC}(27-30a)C(2-4a)C] and [C(23-26a){C(3a)C}(23-27a)C(1a)C] motifs were used for pulling out the sequences of left-right determination factors (LEFTY_A and LEFTY_B), and myostatin, persephin, norrin, and GDF11, respectively; (2) α-glycoprotein hormone, luteinizing hormone (LH), chorionic gonadotropin (CG), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSHβ) [C(12-16a){C(1a)C}(3a)C(7a)C]; (3) bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) [C(27-29a){C(3a)C}(31-33a)C(31-33a)C]; 4) [C(1-3a){C(a)C}(12-14a)C(14-16a)C] trapped the Cys-rich domains of Jagged-1 and -2, chordin and chordin-like proteins, collagen IIA, SCO-spondin and thrombospondins-1 and -2; 5) [C(3-4a){CC}(13-14a)C(16-17a)C] was used for homologues of Slit-1; [C(8-10a){C(3a)C}(15-22a)C(3a)C] pulled out the CK motifs of BMP antagonists and mucin-like protein; [C(5a){C(2a)C}(1a)C(6-7a)C] or [C(20-27a){C(5a)C}(3-6a)C(1a)C] was used for searching CK motif of vascular endothelial and platelet-derived growth factors (VEGF and PDGF); [C(4-6a){C3aC}C(10-15a)C(3a)C] was used for pulling out BMP antagonists, mucins with CK motif, WNT1-inducible proteins, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), VEGF and several other proteins (Cys_Motif file in supplemental data). Cys-Motif searches supply more false-positives than the BLAST searches since they are based solely on limited information supplied by Cys residue distribution in the polypeptide sequence. The Cys-Motif searches are more flexible than the BLAST program since they may supply similar sequence distribution of Cys residues in different superfamilies of proteins that cannot be achieved with the BLAST program.

Global sequence attributes and functional relatedness of proteins

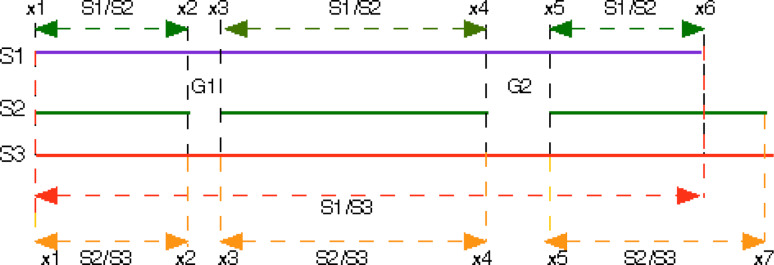

The Datapro program [21] was used to create databases containing sequences extracted from the GenPept files downloaded from the NCBI server [19]. An executable of ClustalW2 for Macintosh was downloaded from ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/software/clustalw2/2.0.10/[22]. Packs of sequences downloaded from various BLAST searches [20] of the NrG_CSD [19] were aligned with the sequences of the CK domains extracted from several X-ray structures, namely 1M4U.pdb, 2ARV.pdb, 2GYZ.pdb, 3HH2.pdb. Corrto1 analyses of multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) revealed that the BLAST searches supplied a large number of sequences whose sequence similarity scores (IDs) for the CK domains were equal to 100%. Those redundant sequences were removed with Corrto1 while Corrto5 as used to trim the long sequences. Packs with unique sequences containing either CK or TFPD motifs were aligned with the ClustalW2 program using Blosum30 AA exchange matrix and gap penalty 10, and the resulting MSAs were analyzed with the Poly-analysis of Sequence Quota (Pola-SQ) program [21]. The Pola_SQ algorithm employs seven fundamental sequence attributes, namely conservation level of consensus sequence, the pI, the overall hydrophobicity (HI), amino acid composition (AAC), Pearson correlation coefficients of hydrophobicity and bulkiness plots, and sequence similarity scores (IDs). These attributes are calculated as shown in Fig. 2, namely if an MSA consist of three sequences s1, s2, and s3 and contains two gaps G1 and G2 then we make comparison between s1 with s2 using the fragments delimited by x1 to x2, x3 to x4, and x5 to x6. For comparison of s1 with s3, we take the sequence length shown with the orange arrows whereas if comparing s2 with s3 we take the fragments delimited from x1 to x2, x3 to x4 and x5 to x7 (yellow arrow).

Fig. 2.

Schema illustrating analyses of sequence attributes in multiple sequence alignment (MSA)

The Pola_SQ objective Fij function was formulated in Eq. (1)

|

1 |

where Cij is the conservation level of the consensus sequence calculated with the Multx program (Cijs may vary from 0 to 1) [21]. Rmsdij is the global root-mean square difference of the AACs, ΔpI is difference in the global pIs, ΔH is difference in the overall global hydrophobicity HIs (vary from 0 to 100%), CCFh and CCFb are the correlation coefficients for hydrophobicity and bulkiness profiles (the CCFh and CCFb may vary from −1 to 1), respectively. The IDij is the global sequence similarity score computed by ClustalW2. P1, P2, and P3 are user-chosen cut-offs for the Rmsd of AAC, pI, and HI changes, respectively. As it was previously discussed [21] the following values for the cut-offs were used in our study: P1 = 1.25, P2 = 2.0, and P3 = 5.0. The following scaling down factors were used, A1 = 0.25, A2 = 0.1, A3 = 0.05 [21]. Since the IDs are expressed in percentage, those values were multiplied by A4 = 0.01. A1, A2, A3, and A4 are merely the scaling factors that keep the Fij values below 1.0. The threshold for the target function (Fij) was in the range of 10–25% of the best match in each of the proteins’ cluster.

MSAs consisting of different numbers of the CK and TFP domains (from 150 to 500 sequences) were analyzed with the following strategy: (1) using each of the entries in given MSA, let us say containing N sequences, the program established N series of clusters containing sequences that were ordered according to the decreasing IDs and the similarities of their attributes (F ij values). For example, clusters of sequences were extracted using two different criteria, namely according to descending values of the Fij function and IDs, e.g., with the following thresholds: the IDs ≥ 25% and F ij > 0.2; (2) the Pola_SQ algorithm generates gradient maps of AA substitutions for the chosen set of clustered sequences that are hierarchically arranged from the top one containing the least number of AA substitutions to the most differentiated sequence (gradient) within given ranges of the F ijs and IDs; (3) this step was followed with analyses of the information entropy (I e) graphs and physico-chemical characteristics of the clustered sequences. Calculation of hydrophobicity profiles of aligned sequences and their HI indexes were made with the hydrophobicity scales as recently described [23].

Structural analyses

The coordinates of X-ray and NMR-structures were obtained from the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (RCSB, http://www.rcsb.org) [22]. The Cordan_Pr program was used for analyses of intramolecular and intermolecular atomic contacts derived from X-ray established structures of diverse TFPDs, CKs, and ICKs that had a reasonable resolution (better than 3.5 Å) [25]. Distance matrices were generated using different distance cut-offs and dividing the intramolecular interactions into: (1) (apolar atom)–(apolar atom); (2) (apolar atom)–(polar atom); (3) (polar atom)–(polar atom). Disulfide bond clusters were computed using the procedure previously described [12]. Briefly, the SS cluster is formed if the van der Waals distances between at least two pairs of sulfur atoms in two cystines is shorter than 7.5 Å. Structures were drawn with the PyMol program [26]. I e values computed from different MSAs and intermolecular distances computed from several X-ray structures containing TFP or CK domains were used for sorting out AAs into these that could have functional aspects (recognition profile derived from ligand–receptor interaction patterns) and those that are fundamental for structural integrity of protein.

Software availability

All the programs presented here were written in standard Fortran 77. They were executed on a mainframe computer working under the Unix system, on a Power Macintosh G4 with the OX10.3 version of the operating system, and a PC Windows station. The precompiled versions of Cys_Motif, Datapro, Corrto1, Corrto5, IDs and PolaSQ for the MacOS and Widows platforms accompanied by a manual and several input and output modules can be obtained from the author. The CPU time for an analysis of a MSA containing 500 sequences does not exceed more than 2 min on a Powerbook G4. The programs were compiled using the Absoft F95 compiler (version 9.0) for the Macintosh and PC Windows series of computers.

Results and discussion

Diverse proteins encoded in the human genome contain Cys-sequence motifs similar to that of the archetypal CK domain

A great majority of human proteins contain from one to several dozen Cys residues (Fig. S1 in the supplemental data). Human genomic database was searched with the Cys_motif program using diverse lengths of amino acid patches between the chosen Cys residue frameworks. For example, searching with a Cys motif taken from the human TGFβ2 (NP_003229), the program pulled out most of its paralogues as well as WNT1-inducible factors (CCN proteins), some members of the Schlafen family of proteins and several other hits. Searching with the Cys motif present in the human Gremlin 1 protein, the program pulled out the remaining human antagonists of the TGFβs and several other proteins. The CK spatial motif is a part of several other human proteins ranging from small hormones such as glycoprotein α subunit to large multi-domain proteins. Small human CK motif-containing proteins are TSHβ (NP_000540), LH (NP_000885), CG (NP_000728), GPHα-related hormone (NP_570125) and FSHβ (NP_082111). Several multidomain proteins contain putative CK motif, namely some mucins, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF, NP_001892), vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF, NP_001020537), platelet-derived growth factors (PDGF, NP_002598) [3], and a series of WNT1-inducible-signaling pathway protein 1 (NP_003873), also known as CCN family of proteins (WISP-3, WISP-1, CYR61, CTGF and NOV) [27]. Some large proteins have similar sequence distribution of Cys residues as that in the CK domain, namely Jagged-1 and -2 (NP_000205, NP_660142) [28], slit isoforms from 1 to 3 (NP_003052, NP_004778, NP_003053), some collagens and chordin-like proteins [3]. Whether these proteins have true CK motifs or similar Cys motifs such as von Willebrand domains C and D (VWC and VWD) could be verified when X-ray and NMR structures become available. The VWC and VWD folds, however, have different connectivity and spatial configurations of Cys residues than the CK, ICK, or TFPD folds. Three molecular structures illustrating fundamental structural differences between the CK and VWC domains are shown in supplemental data, namely homodimer of the Spätzle protein from D. melanogaster (CK domain, 3E07.pdb, Fig. S2A in the supplemental data) [29], chordin-like Cys-rich repeat from the N-terminus of Collagen IIA (VWC fold, 1U5 M.pdb, Fig. S2B) [30] and Crossveinless-2 bound to BMP2 (VWC fold, 3BK3.pdb, Fig. S2C), respectively [31, 32].

The TGFβ family of proteins and their antagonists encoded in the human genome

Table 1 summarizes several nominal sequence attributes of the human proteins belonging to the TGFβ superfamily and some of their antagonists whereas Table S1 (supplemental data) contains the amended list of the human proteins containing from one to three TFPDs [17]. The archetypal TGFβ-like CK domain has about 11 kDa with fully conserved spatial configuration of the three SS bonds. Some of the CK domains of the TGFβ family of proteins are highly hydrophobic, namely those of BMP3, GDF1, GDF7, and inhibin βC. Likewise, highly hydrophobic are two antagonists of the TGFβs, namely Dante and Cerberus 1. In contrast, some TGFβs and their antagonists are hydrophilic such as GDF9, Neurturin, Gremlin 1, and Gremlin 2. The differentiated hydropobicity (HIs) and pI values of the CK domains of this series of proteins were probably optimized for proper stability of the ternary complexes with their respective receptors and inhibitory proteins.

Table 1.

Fundamental sequence attributes of some human proteins containing CK motif

| No. | Protein | Gene | Accession | PDB | Chromosome | NAA | CK-domain | pI | HI | m (kDa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGFβ superfamily of proteins | ||||||||||

| 1 | BMP2 | BMP2 | NP_001191 | 3bk3,1es7 | 20p12 | 396 | 295–396 | 5.9 (9.1) | 40.2 (31.1) | 11.4 (44.7) |

| 2 | BMP3 | BMP3 | NP_001192 | 2qcq | 4q21 | 472 | 369–472 | 7.9 (9.9) | 51.0 (30.7) | 11.6 (53.4) |

| 3 | BMP4 | BMP4 | NP_001193 | 14q22-q23 | 408 | 307–408 | 4.9 (8.8) | 45.1 (30.4) | 11.4 (46.6) | |

| 4 | BMP5 | BMP5 | NP_066551 | 6p12.1 | 454 | 352–454 | 7.1 (9.0) | 43.7 (33.9) | 11.7 (51.7) | |

| 5 | BMP6 | BMP6 | NP_001709 | 2r52,2qcw | 6p24-p23 | 513 | 411–513 | 7.6 (8.0) | 39.8 (32.4) | 11.7 (57.2) |

| 6 | BMP7 | BMP7/OP-1 | NP_001710 | 1m4u | 20q13 | 431 | 329–431 | 6.4 (7.7) | 40.8 (35.5) | 11.7 (49.3) |

| 7 | BMP8A | BMP8A | NP_861525 | 1lxi | 1p34.2 | 402 | 300–402 | 7.8 (8.8) | 44.7 (40.0) | 11.6 (44.8) |

| 8 | BMP8B | BMP8B | NP_001711 | 1p35-p32 | 402 | 300–402 | 7.0 (8.3) | 48.5 (41.0) | 11.6 (44.8) | |

| 9 | BMP10 | BMP10 | NP_055297 | 2p14 | 424 | 322–424 | 8.1 (4.7) | 43.7 (32.1) | 11.7 (48.1) | |

| 10 | BMP15 | BMP15 | NP_005439 | Xp11.2 | 393 | 290–392 | 7.6 (9.3) | 44.7 (34.4) | 11.8 (45.0) | |

| 11 | GDF1 | GDF1 | NP_001483 | 19p12 | 372 | 266–372 | 7.9 (9.1) | 53.3 (50.0) | 11.6 (39.5) | |

| 12 | GDF2/BMP9 | GDF2/BMP9 | NP_057288 | 10q11.22 | 429 | 326–429 | 7.0 (6.0) | 44.2 (33.3) | 11.7 (47.3) | |

| 13 | GDF3 | GDF3 | NP_065685 | 12p13.1 | 364 | 263–364 | 5.8 (7.8) | 44.1 (44.8) | 11.7 (41.4) | |

| 14 | GDF5 | GDF5/BMP14 | NP_000548 | 3evs,1wag | 20q11.2 | 501 | 399–501 | 4.9 (10.2) | 43.7 (27.3) | 11.8 (55.4) |

| 15 | GDF6 | GDF6/BMP13 | NP_001001557 | 8q22.1 | 455 | 353–455 | 5.1 (9.0) | 42.7 (28.4) | 11.6 (50.1) | |

| 16 | GDF7 | GDF7/BMP12 | NP_878248 | 2p24.1 | 450 | 348–450 | 4.8 (10.0) | 50.5 (40.7) | 11.6 (47.0) | |

| 17 | GDF8/Myostatin | GDF8/MSTN | NP_005250 | 3evs | 2q32.2 | 375 | 280–375 | 8.2 (6.3) | 37.5 (34.4) | 11.0 (42.8) |

| 18 | GDF9 | GDF9 | NP_005251 | 1zkz | 5q31.1 | 454 | 352–454 | 7.6 (9.2) | 24.3 (33.9) | 11.9 (51.4) |

| 19 | GDF10/BMP3A | GDF10 | NP_004953 | 10q11.22 | 478 | 375–478 | 7.5 (9.8) | 50.0 (34.1) | 11.6 (53.1) | |

| 20 | GDF11/BMP11 | GDF11/BMP11 | NP_005802 | 12q13.2 | 407 | 312–407 | 8.4 (7.8) | 29.2 (33.9) | 11.1 (45.1) | |

| 21 | GDF15 | GDF15/PLAB | NP_004855 | 19p13.11 | 308 | 209–308 | 7.5 (9.9) | 39.0 (32.1) | 11.1 (34.1) | |

| 22 | Activin βE | INHBE | NP_113667 | 12q13.3 | 350 | 246–350 | 6.0 (9.4) | 36.2 (36.6) | 11.6 (38.6) | |

| 23 | Inhibin α | INHA | NP_002182 | 3b4v,1s4y | 2q33-q36 | 366 | 261–366 | 7.6 (7.9) | 50.0 (41.8) | 11.6 (34.0) |

| 24 | Inhibin βA | INHBA | NP_002183 | 2b0u,2arp | 7p15-p13 | 426 | 320–426 | 7.5 (7.9) | 31.8 (31.7) | 12.1 (47.4) |

| 25 | Inhibin βB | INHBB | NP_002184 | 2cen-q13 | 407 | 302–407 | 5.0 (7.9) | 47.2 (36.4) | 11.9 (45.1) | |

| 26 | Inhibin βC | INHBC | NP_005529 | 12q13.1 | 352 | 246–352 | 5.3 (6.7) | 55.1 (45.5) | 11.7 (38.2) | |

| 27 | TGFβ1 | TGFB1 | NP_000651 | 19q13.1 | 390 | 292–390 | 8.4 (8.5) | 41.4 (36.2) | 11.3 (44.3) | |

| 28 | TGFβ2 | TGFB2 | NP_003229 | 1q41 | 414 | 316–414 | 7.8 (8.5) | 39.4 (30.9) | 11.3 (47.8) | |

| 29 | TGFβ3 | TGFB3 | NP_003230 | 1tgk,2pjy | 14q24 | 412 | 314–412 | 7.5 (7.9) | 33.3 (28.6) | 11.2 (47.3) |

| 30 | Nodal | NODAL | NP_060525 | 10q22.1 | 347 | 246–347 | 7.9 (6.7) | 31.4 (36.0) | 11.8 (39.6) | |

| 31 | Anti-Mullerian hormone | AMH | NP_000470 | 19p13.3 | 560 | 461–560 | 8.2 (7.0) | 44.0 (47.0) | 10.9 (59.2) | |

| 32 | LEFTY_A | LEFTY2 | NP_003231 | 1q42.1 | 366 | 262–354 | 8.1 (8.5) | 35.5 (38.5) | 10.5 (40.9) | |

| 33 | LEFTY_B | LEFTY1 | NP_066277 | 1q42.1 | 366 | 262–354 | 7.9 (8.2) | 31.2 (36.3) | 10.5 (40.9) | |

| 34 | GDNF | GDNF | NP_000505 | 2v5e,3fub | 5p13.1-p12 | 211 | 117–211 | 7.0 (9.3) | 31.6 (28.0) | 10.7 (23.7) |

| 35 | Neurturin | NTN | NP_004549 | 19p13.3 | 197 | 102–197 | 8.2 (11.4) | 28.1 (35.0) | 11.1 (22.4) | |

| 36 | Persephin | PSPN | NP_004149 | 19p13.3 | 156 | 65–155 | 8.7 (9.5) | 33.0 (37.2) | 9.9 (16.6) | |

| 37 | Artemin-2I | ARTN | NP_476501 | 2gyz | 1p33-p32 | 237 | 139–236 | 10.8 (12.2) | 31.6 (38.0) | 10.7 (24.5) |

| Several antagonists of TGFβs containing CK domain | ||||||||||

| 1 | Gremlin 1 | GREM1 | NP_037504 | 15q13-q15 | 184 | 92–182 | 9.5 (9.7) | 17.6 (19.0) | 10.7 (20.7) | |

| 2 | Gremlin 2 | GREM2/PRDC | NP_071914 | 1q43 | 168 | 71–161 | 8.8 (9.4) | 18.7 (26.2) | 10.7 (19.3) | |

| 3 | Cerberus 1 | CER1 | NP_005445 | 9p23-p22 | 267 | 160–245 | 7.5 (7.6) | 52.3 (33.3) | 9.4 (30.1) | |

| 4 | Dante | COCO/DAND5 | NP_689867 | 19p13.13 | 189 | 99–189 | 9.7 (10.1) | 54.9 (52.9) | 9.9 (20.2) | |

| 5 | Norrin | NDP | NP_000257 | Xp11.4 | 129 | 37–132 | 9.2 (8.8) | 31.3 (34.6) | 11.0 (15.0) | |

| 6 | Sclerostin | SOST | NP_079513 | 17q11.2 | 213 | 78–171 | 10.4 (9.5) | 30.9 (23.0) | 10.6 (24.0) | |

| 7 | USAG1 | SOSTDC1 | NP_056279 | 2k8p/2kd3 | 7p21.1 | 206 | 73–169 | 9.4 (10.1) | 30.9 (28.6) | 11.0 (23.3) |

| 8 | NST | NBL1 | NP_005371 | 1p36.13 | 180 | 32–123 | 5.3 (5.0) | 35.9 (31.1) | 10.1 (19.3) | |

BMP bone morphogenetic protein, GDF growth/differentiation factor, TGF transforming growth factor, GDNF glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor, LEFTY_A endometrial bleeding associated factor, LEFTY_B left–right determination factor B, USAG-1 uterine sensitization-associated gene 1.Only selected PDB codes were included, Naa number of amino acid residues, pI piezoelectric point, HI overall hydrophobicity

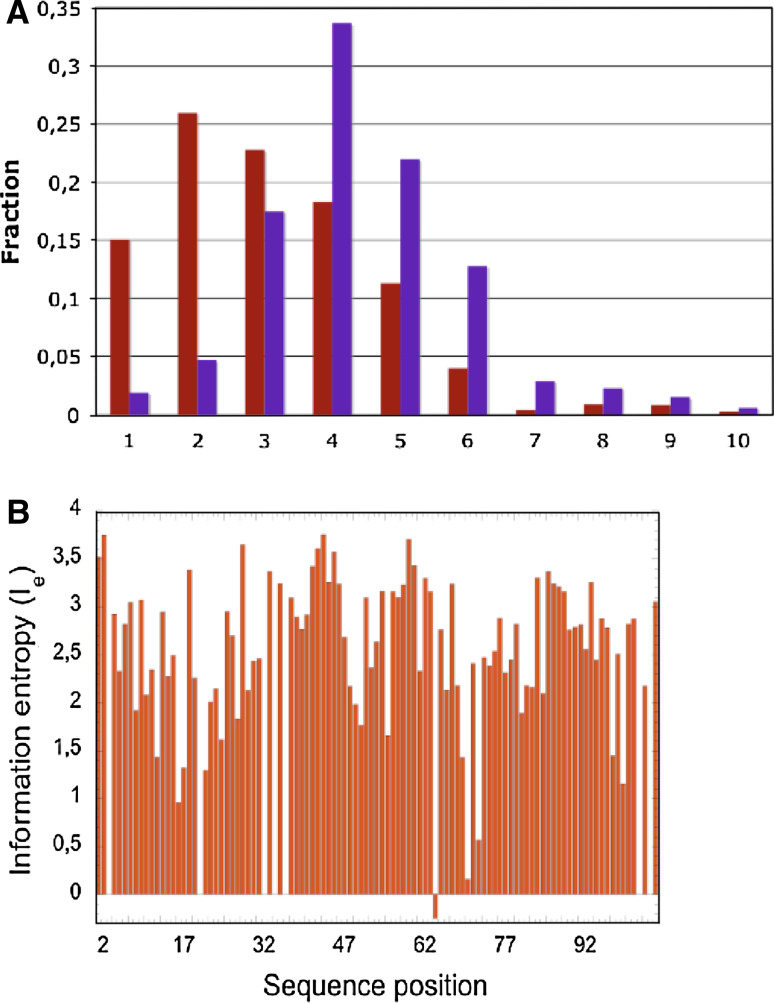

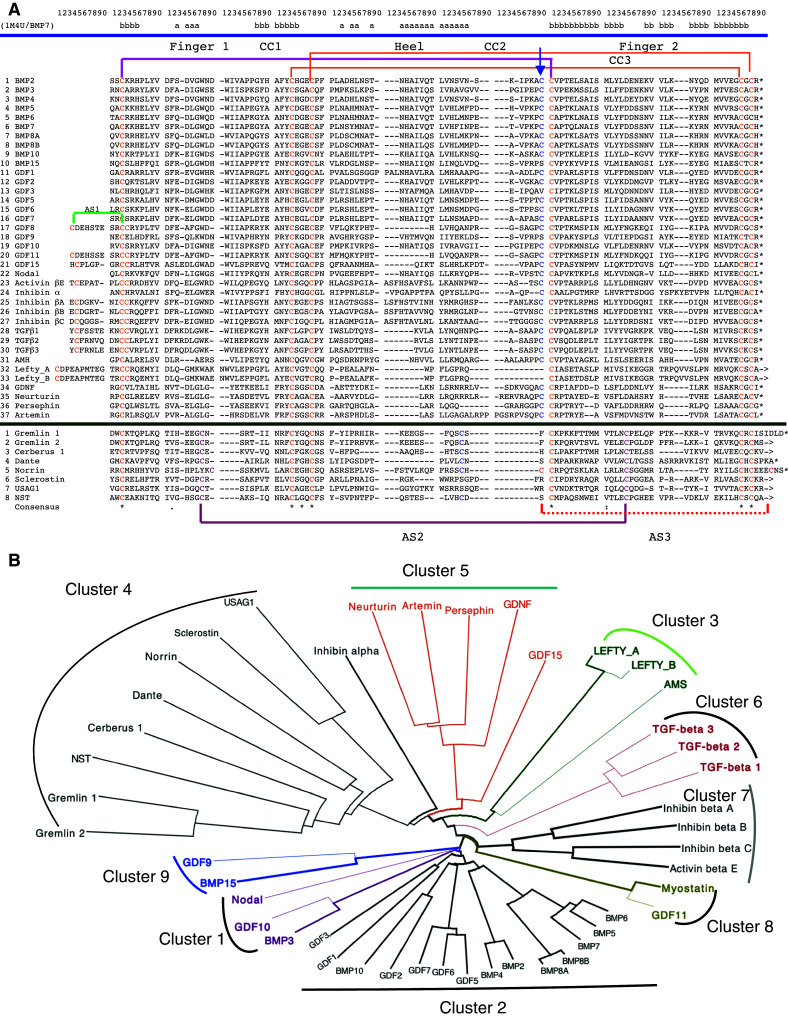

Figure 3a shows MSA containing the sequences of the CK domains of the human TGFβ superfamily of proteins and some of their antagonists (MSA45), whereas their dendrogram containing several distinct branches is shown in Fig. 3b. In the MSA45, all the Cys residues forming the ‘macrocycle’ are in yellow, except the one that gives rise to the intermolecular S–S bond that is indicated with a blue arrow at the top of the MSA. One of the Cys residues of the SS bond (red line) passing through the ‘macrocycle’ formed of the remaining two SS bonds (yellow lines) flanks the Cys residue forming intermolecular SS bond (blue arrow). Some members of the TGFβs contain an additional SS bond at the N-terminus (S1b, green line) that prolongs the knotted SS bond (SS_KB, see Fig. 1a). The CK domains of the TGFβ antagonists have only some of the Cys residues aligned with those of the TGFβ factors. Moreover, some of them have nine or more Cys residues that probably rigidify the CK fold. For example, the SS bond AS2 is common to all eight antagonists (deep violet line) and it tightens up the tips of fingers 1 and 2. The putative AS3 bond (red dotted line) occurs only in Norrin and its experimental evidence is missing. Analysis of the distribution of sequence similarity scores (IDs) (Fig. 4a) and information entropy graph derived from the MSA45 (Fig. 4b) show that only the sequence positions occupied by the Cys residues forming the CK motif have high conservation levels. In consequence, the average ID of MSA45 is 26.5%, whereas it reaches 40% in the MSA449 that contains sequences with a lesser functional diversity.

Fig. 3.

a Multiple alignment of 37 sequences of the CK domains of the human TGFβ superfamily of proteins and 8 of their antagonists. b Dendrogram of the human TGFβ superfamily of proteins and their antagonists; the dendrogram was made with dendroscope [31]

Fig. 4.

a Distribution of the IDs in the MSA45 (brown bars) and MSA449 (violet bars). b Information entropy (Ie) calculated from the MSA45. One should note that Ie = 0 for fully conserved sequence positions whereas Ies > 1.0 signify that given sequence position display heterogeneous AAC. Negative values were automatically assigned to sequence positions having less than 50% residue occupancy

The dendrogram reveals some basic functional relatedness within the TGFβ superfamily of proteins. Firstly, from the principal node created by BMP15 and GDF9 (cluster 9) emerges a small cluster containing Nodal, BMP3, and GDF10 (cluster 1), which is linked to a large cluster comprising the multiple isoforms of BMPs and GDFs (cluster 2). Secondly, from the principal node emerges a small cluster containing myostatin and GDF11 (cluster 8) and two other small clusters containing the inhibin group of proteins (cluster 7) and the three isoforms of the TGFβs (cluster 6). Thirdly, there is a group comprising two other clusters, namely the cluster comprising GDNF, GDF15, and related neurotrophic factors (cluster 5), which, via inhibin-α, is connected to the cluster of the antagonists of the various members of TGFβs (cluster 4). Fourthly, a small cluster composed of LEFTY_A, LEFTY_B, and AMH (cluster 3) is linked to the ensemble of clusters 4, 5, and 6. GDNF and the related factors in the cluster bind to the ectodomain of the glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor family receptor α3 (GFRα3) that is formed of α-helical segments.

Conservation of common sequence traits in the TGFβ superfamily of proteins expressed in disparate organisms

BLAST searches and Pola_SQ analyses revealed that several sequences having the signature of the TGFβs are encoded in the genomes of various invertebrates (the nematode C. elegans and the insect D. melanogaster) and disparate marine organisms including the chordate Ciona intestinalis, which is a reasonable system for exploring the evolutionary origin of its small genome from which all vertebrates probably sprouted. Persephin, Neurturin and Artemin were found only at the vertebrates [32], whereas a distant putative orthologue of the vertebrate GDNF (XP_002126873) is encoded in the C.insetinalis genome. Several packs containing from 150 to 450 sequences of the TGFβ superfamily of proteins encoded in different genomes were aligned with the ClustalW2 program, namely MSA282 and MSA449 accompanied by Ie graphs are in the supplemental data (Res1_sum and Res2_sum files). Also, several hundreds of ectodomains (TFPDs) of TGFβ receptors encoded in various genomes were aligned, namely MSA286 containing TFPDs expressed in different organisms is in the supplemental data (Res3_sum file). Information entropy (Ie) graphs calculated for the above two superfamilies of proteins showed that only some Cys residues are highly conserved.

Analyses of the above MSAs were made with the Pola_SQ program. Firstly, the program created groups of functionally related proteins that sustain the relationships shown in the dendrogram for the human TGFβs (Fig. 3b). This is due to the fact that the CK domains in each of the clusters retain high conservation level of their fundamental physico-chemical sequence attributes, such as hydrophobicity, pI, or distribution of bulk AAs along the polypeptide chain. For example, the three human isoforms TGFβ1, TGFβ2, and TGFβ3 clustered only with their orthologues expressed in diverse organisms whereas human myostatin was clustered with the CK domain of GDF11 expressed in various species (Res1_sum file in the supplemental data); several other examples of conservation of physico-chemical attributes of sequences are shown in Res2_sum file in the supplemental data. Secondly, orthologues of the human TGFβs superfamily of proteins encoded in different vertebrate genomes are highly conserved. For example, the CK domain of the human TGFβ3 (NP_003230) has from 97 to 98% of sequence similarity to those expressed in rat (NP_037306), pig (NP_999363), and chicken (NP_990785). Similar levels of conservation were calculated for the other orthologues of the TGFβs encoded in the genomes of these four organisms. Moreover, a TGFβ1-like sequence is also encoded in the genome of deer poxvirus W-848-83 (YP_227538) [35]. Since the sequences of the mammalian orthologues of the TGFβs retain a relatively high conservation level, is it then possible that an excess of those growth factors (morphogens) in the ingested food could be crucial in initiation of tumoral transformation of some cells lining the basement of the digestive system. It has been shown that the human BMP2 and BMP4 can functionally substitute their Drosophila homologue (encoded by the dpp gene) in fly embryogenesis [36]. Thirdly, the gradient maps of AA substitutions in functionally related clusters of proteins created by Pola_SQ show that some sequence positions are highly conserved (Fig. S3 in supplemental data). For example, in the X-ray structure of the ternary complex comprising the human TGFβ1 bound to an assembly of TGFβ-RII/TGFβ-RI (3KFD.pdb) [37], the residues W30 and W32 in the first finger and Y90, V92, K97, and I101 in the second finger of the TGFβ1 are crucial for complex formation. These residues are almost fully conserved in MSA20T containing 20 orthologues of the human TGFβ1 expressed in disparate organisms such as humans and Xenopus laevis; the MSA20T was extracted from MSA282 with the Pola_SQ algorithm (Fig. S3 is in the supplemental data). The AAs conserved in TGFβ1 are also well conserved in its two closely related isoforms, namely TGFβ2 and TGFβ3 encoded in various genomes. Moreover, multiple other sequence positions in the MSA20T and MSA282 have relatively low Ie values (supplemental data), which implies that they could be crucial to the CK fold and its interaction with different combinations of receptors. Fig. S4 (supplemental data) illustrates the structure of the human TGFβ1 taken from the 3KFD.pdb file with the indicated AAs that interacts with the receptor (TGFβ-RII and TGFβ-RI). Cordan_Pr made analyses revealed that hydrophobic (side chain)-(side chain) constitute the majority of intermolecular interactions in this complex (Inter.dis is in supplemental data). Fourthly, similar results supplied Pola_SQ analyses of the ectodomains (TFPDs) of different BMP, TGFβ and activin receptors expressed in various organisms.

2D distribution of secondary structures in the archetypal CK spatial motifs

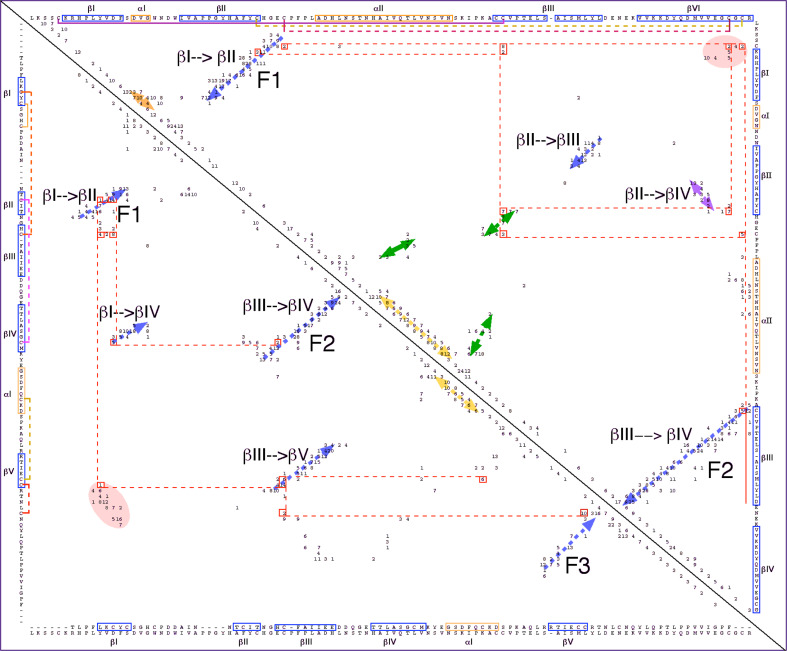

Figure 5 shows a 2D map of intramolecular interaction patterns in the two CK domains, namely BMP7 bound to its antagonist Noggin [38] (upper panel), and the human Artemin (lower panel) bound to its receptor GFRα3 [39], respectively. The aligned sequences of BMP7 and Artemin are shown in the lower axis of Fig. 5; there is a low overall sequence similarity (ID = 17%) for these two CK domains. Two long fingers formed by anti-parallel β-sheets (blue arrows perpendicular to the diagonal) are spaced by an α-helix (yellow arrow parallel to the diagonal) that is often called ‘the heel’ (Fig. S5 in the supplemental data). The fingers are well aligned on the 2D map whereas α-helical segments are slightly displaced from each other due to a small difference in sequence length of these two domains. There is a small interaction cluster between the N- and C-termini for each of the domains indicated as salmon ovals at the upper and lower corners, respectively. Such interaction clusters are typical features of all the TFPDs [12]. Several other scattered interaction clusters of the C-terminal β-strand and β2 (pink arrow) occupy quasi-similar positions in both triangles. Interaction clusters between the sequence segments linking α1 with β2 (light blue ovals) are in similar positions in both triangles. The interaction clusters between the sequence segment that is localized N-terminal to β3 with α-helix 2 (brown arrows) has only in BMP7 an additional cluster due to interactions between α2 and the C-terminal part of β-strand II (green arrow, upper panel) (1M4U.pdb). Despite a considerable structural similarity of these two CK domains, they are bound to the ectodomains that display different folds, namely TFPD (BMP7) and α-helical domain of GFRα3 (Artemin).

Fig. 5.

Bi-dimensional map of BMP7 (1M4U.pdb) bound to Noggin [36] (upper panel) and human Artemin bound to its receptor GFRα3 (2GYZ.pdb) [37] (lower panel). The sequence similarity score for hBMP7/Artemin is ID = 17%. β-strands are shown as blue arrows whereas α-helices positioned near the diagonal are shown as yellow arrows

Inspections of several other 2D images of the diverse CKs have revealed that there are some differences in this group of folds. For example, the 2D map of VEGF bound to its second extracellular IGG-like domain of the FMS-like tyrosine kinase 1 (1FLT.pdb) [40] (Fig. S6A in the supplemental data) shows that even if the two long fingers and N- to C-terminus interaction clusters occupy similar positions in the fold space, there are several marked changes with respect to the above 2D images, namely there is no α-helical segment (the heel) linking the two fingers and some additional short β-strands add some diversity to the fold. The right uppermost part of Fig. S6A is similar to the typical CK fold in the TGFβs. In contrast, the 2D intramolecular interaction map displayed by Noggin (1M4U.pdb, Fig. S6B in the supplemental data) does not have the interaction cluster between the N-terminal and C-terminal segments of its CK domain. Even if an eight-membered knot of the TGFβ superfamily of proteins and a ten-membered knot of Noggin have the same topology of their fingers, finger 1 (F1) of the latter is flanked by a long α-helical region that induces other types of intramolecular interactions than those in a typical CK domain of the TGFβs.

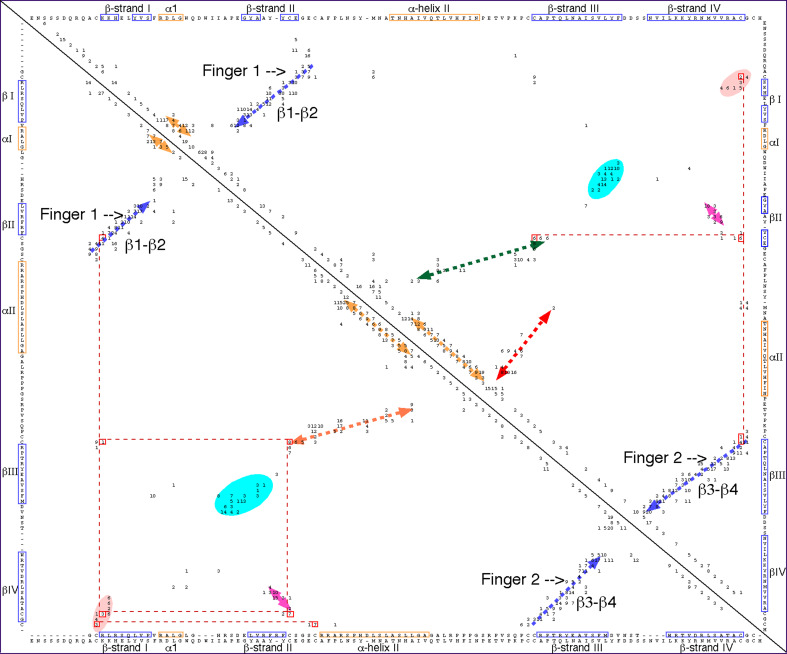

Comparison of the two fold spaces: CK and TFPD

Figure 6 shows a 2D image summarizing diverse interaction clusters in BMP2 (CK spatial motif, upper panel) bound to BMP receptor type IA (BMP-RIA1, 2H64.pdb) displaying the TFPD fold [41]; the entire structure of the ternary complex involving also activin receptor IIB (ActR_IIB) is shown in Fig. S7 (supplemental data). Although there is no sequence similarity between both domains (ID = 5%), we used ClustalW2-made sequence alignment as a guiding element in placing the secondary structure in the 2D image (the Cordan_2D program). Both fingers 1 and 3 of the TFPD fold (lower panel) are well aligned with fingers 1 and 2 (CK fold) in the upper panel. Likewise, the clusters comprising interactions between the N- and C-termini are positioned at similar coordinates (salmon ovals at the corner of each triangle). There is a small 2D shift between the positions of the α-helices that is due to the fact that the sequence length is not equal in these two structures. The major difference in both triangles is due to the presence of finger 2 in the TFPD (lower panel) that is replaced by α-helical segment and several scattered interaction clusters in the CK fold (green arrows) and interaction cluster from parallel β-sheet (βII->βIV, violet arrow). One should keep in mind that in a typical TFPD fold, the three fingers point roughly in the same direction, whereas in the CK fold, the two β-strand-made fingers are longer and wind about each other while the helix (the heel) linking these two segments points in the opposite direction (Fig. S7 in the supplemental data). Our analyses suggest that these two different folds have several common spatial traits that could have been acquired from their common ancestor.

Fig. 6.

2D map of intramolecular interaction clusters in BMP2 (upper panel) bound to BMP-RIA1 (lower panel) (2H64.pdb) [41]

Structural difference between the ICK and CK folds

The human agouti signaling protein (AISP) [8] has five SS bonds in its ICK fold having only 39 AAs while the CART protein [11] has three SS bonds. Due to the fact that these structures are smaller than the archetypal CK or TFPD folds of the TGFβs and the ECDs of their receptors, the interaction clusters are densely packed on the 2D maps (Figs. S8a and S8b in the supplemental data). The ICK folds have different intramolecular interaction patterns as compared to typical CK fold. The archetypal CK domain contains three disulfide bridges forming the conserved spatial feature (knot) in which interactions between the disulfide passing through the ring formed with the remaining two disulfides are relatively strong; distances between sulfur atoms are within 4.2–5.6 Å. There is no pairwise short-range interaction (d ≤ 7.5Å) between the disulfides forming the ring of the CK spatial motif. Some of the CK domains, however, contain more than three nominal SS bridges. For example, the glycoprotein hormone α chain contains six SS bonds, whereas the FSHβ subunit (1XWD.pdb) [42] has five disulfides and forms non-covalent dimer with the former that binds to the extracellular domain of the follitropin receptor (GPCR) [3]. In both subunits, only the SS bonds forming the CK motif have short-distance (d ≤ 5Å) interactions between their sulfur atoms, whereas the other SS bonds do not interact with each other. More variable interaction patterns are formed between the disulfides forming the diversified ICK spatial motif, namely the distances between the sulfur atoms may vary from 3.2 to 7.5 Å.

Conclusions

The CK domain present in numerous metazoan proteins interacts with a variety of targets, namely with the TFPD ectodomains of the TGFβ superfamily of receptors [1, 3, 4, 12], co-receptor Cripto-1 [42] that also regulates canonical WNT signaling [43], some GPCRs [25, 44, 45], α-helical GFRα3 [39], and the low-density lipoprotein-receptor gene family LRP5, LRP6, and LRP4 [46, 47] that links Dickkopf1 and USAG1 (Wise protein) with WNT and BMP signaling pathways [43, 48]. The CK domains of the TGFβ factors bind to diverse extracellular proteins such as the eight TGFβ antagonists (Table 1) and other antagonists, namely follistatin-like 1 and follistatin-related gene (FLRG, follistatin-like 3) [49], Noggin, and bone morphogenetic protein and activin membrane-bound inhibitor (BAMBI) [50], Twisted gastrulation [51], and VWC repeats of the chordin-like proteins, e.g., Ventroptin (NP_001137453, also know as Neuralin) [3]. It is likely that this list is far from complete since the CK motif may be also present in the Sco-spondin family of proteins [52] and in many proteins whose functions remain unknown (Cys_Motif in the supplemental data). Sequence attributes-based fine clustering of protein sequences followed with quantification of AA substitutions in a given subgroup within a multigene superfamily of functionally related proteins could be useful for the detection of the residues that are crucial for the fold and its interaction with biologically relevant targets. The I e graphs derived from the MSAs of functionally related factors of the TGFβs and the ectodomains of their principal receptors show that some of the sequence positions are highly conserved (Figs. S3 and S4 in the supplemental data).

Several different folds consist of β-structure-rich fingers that are tightened up by distinct Cys–Cys networks. For example, Interleukin-17 (Il-17; NP_443104) has its spatial arrangement of fingers similar to that of the archetypal CK domain, but the fingers are tightened up by only two SS bonds at the ‘heel’ of the molecule (1JPY.pdb) while there is no third SS bond that would pass through the macro-cycle formed by the two SS bridges (Fig. S9A in the supplemental data). This implies that the key element of the CK domain is missing in the Il-17 fold [53]. Even if several other groups of proteins contain fingered structures that are rich in β-strands, such as Dickkopf1 (Dkk1) (Fig. S9B in the supplemental data) [54] or the Argos protein [55], but all those folds are stabilized by distinct spatial configurations of SS networks. Moreover, intramolecular interaction patterns are different in these three folds than in the CK and TFPD folds. So far, only one intriguing structural similarity between the agglutinin fold and that of the TFPD fold of a snake neurotoxin has been discussed [56].

The CK and TFPD folds have different Cys-Cys connectivity that implies different spatial configurations of their cystine networks, but our analyses indicate that these folds have several common spatial traits. Firstly, both folds have the interaction cluster between the N and C terminal domains. Secondly, both folds have two fingers well aligned in the 2D intramolecular interaction maps. Thirdly, both domains have a tightly packed network of disulfide bridges (see Fig. 7). The central finger in the TFPD fold points in the same direction as the remaining two fingers, whereas in the CK fold, α-helix forming ‘heel’, a spatial equivalent of the central finger of the TFPD, points in the opposite direction than the two long fingers. Although origins of primordial TFPD and CK domains remain enigmatic, it is tempting to speculate that they had a common ancestor or that one of them was derived from the other. Another possibility is that they were derived from two different folds and co-evolved since then [59, 60]. Taking into consideration the first hypothesis, a primordial TFPD could have been created via reshuffling the exons coding for the CK domain that would involve reorganization of the Cys-Cys connectivity. Sequencing of genomic segments from diverse species revealed that various TGFβ genes have several coding regions but some organisms have non-standard distribution of exons and introns, namely the gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) TGFβ1 gene [61] has five exons with the last exon splitting the β-structure of the C-terminal finger (F2) (see supplemental data). Moreover, the CK domains of diverse proteins have a strong natural tendency to form dimers. Evolutionary pressure could have retained this tendency by creating a primordial TFPD fold that could bind the CK fold from which the former was derived in an invertebrate organism at a low level of development. This could be formed via inversion of the coding direction of the three exons 3, 4, and 5 as proposed in Fig. S10 (in supplemental data). The BAMBI receptor (TFPD fold) with a short transmembrane domain but no kinase domain attached to it binds diverse members of the TGFβs [50]. The primordial BAMBI-like TFPD would have to undergo fusion with and a kinase domain that should give rise to an activin-like receptor. BAMBI-like genes are encoded at different metazoans such as the invertebrates Saccoglossus kowalevskii (GI:90659973), the insect Tribolium castaneum (GI:270014280), and ending on mammals (H. sapiens, NP_036474.1, GI:6912534).

Fig. 7.

The structure of murine Sclerostin (upper panel, 2KD3.pdb) [53] and Activin receptor IIB (lower panel, 1S4Y.pdb) [54] showing spatial positioning of the fingers, a flexible ‘heel’ loop while the disulfide networks are shown in shaded ellipses

Diverse proteins containing the CK domain are crucial developmental factors (morphogens) for a myriad of metazoan organisms [1, 62–65]. Fine characterization of temporal and spatial dynamics of locally secreted gradients of morphogens, their receptors, antagonists, and diverse signaling factors embedded in the extracellular matrix could unravel the hidden ‘modus vivendi’ of intercellular communication networks. Understanding the different molecular mechanisms and biological functions generated by gradients of diverse morphogens including the TGFβ superfamily of proteins could be beneficiary to future pharmacological strategies applied to developmental [62, 65, 66] and regenerative medicine [67, 68], stem cell expansion and induced pluripotency [69], medical diagnostics and anticancer therapy [70, 71], as well as in controlling developmental stages of tumors [72] and their metastases [73].

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to SIMOPRO/iBiTecS/DSV/CEA for financial support.

Abbreviations

- TGFβ

Transforming growth factor

- GDF

Growth/differentiation factor

- GDNF

Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor

- AMH

Anti-Mullerian hormone

- PDGF

Platelet-derived growth factor

- LEFTY_A

Endometrial bleeding associated factor

- LEFTY_B

Left–right determination factor B

- PLGF

Placental growth factor

- CTGF

Connective tissue growth factor

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- CG

Chorionic gonadotropin hormone

- DAN

Differential screening-selected gene aberrative in neuroblastoma

- FSHβ

Follicle-stimulating hormone

- ActRIB

Activin receptor type IB

- ALK

Activin receptor-like kinase

- BMP

Bone morphogenetic protein

- BMPR

BMP receptor

- ASIP

Agouti signaling protein

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- TFPD

Three-fingered protein domain

- CK

Cystine knot

- ICK

Inhibitor cystine knot

- ECD

Ectodomain

- MSA

Multiple sequence alignment

References

- 1.Chang H, Brown CW, Matzuk MM. Genetic analysis of the mammalian transforming growth factor-β superfamily. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:787–823. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massagué J, Blain SW, Lo RS. TGFβ signaling in growth control, cancer, and heritable disorders. Cell. 2000;103:295–309. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vitt UA, Hsu SY, Hsueh AJ. Evolution and classification of cystine knot-containing hormones and related extracellular signaling molecules. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:681–694. doi: 10.1210/me.15.5.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isaacs NW. Cystine knots. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1995;5:391–395. doi: 10.1016/0959-440X(95)80102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avsian-Kretchmer O, Hsueh AJ. Comparative genomic analysis of the eight-membered ring cystine knot-containing bone morphogenetic protein antagonists. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:1–12. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gracy J, Le-Nguyen D, Gelly JC, Kaas Q, Heitz A, Chiche L. KNOTTIN: the knottin or inhibitor cystine knot scaffold in 2007. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D314–D319. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groppe J, Hinck CS, Samavarchi-Tehrani P, Zubieta C, Schuermann JP, Taylor AB, Schwarz PM, Wrana JL, Hinck AP. Cooperative assembly of TGFβ superfamily signaling complexes is mediated by two disparate mechanisms and distinct modes of receptor binding. Mol Cell. 2008;29:157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolin KA, Anderson DJ, Trulson JA, Thompson DA, Wilken J, Kent SB, Gantz I, Millhauser GL. NMR structure of a minimized human agouti-related protein prepared by total chemical synthesis. FEBS Lett. 1999;451:125–131. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00553-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craik DJ, Mylne JS, Daly NL. Cyclotides: macrocyclic peptides with applications in drug design and agriculture. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:9–16. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0159-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henriques ST, Craik DJ. Cyclotides as templates in drug design. Drug Discov Today. 2010;15:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ludvigsen S, Thim L, Blom AM, Wulff BS. Solution structure of the safety factor, CART, reveals new functionality of a well-known fold. Biochemistry. 2001;40:9082–9088. doi: 10.1021/bi010433u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galat A, Gross G, Drevet P, Sato A, Ménez A. Conserved structural determinants in three-fingered protein domains. FEBS J. 2008;275:3207–3225. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsernoglou D, Petsko GA. The crystal structure of a post-synaptic neurotoxin from sea snake at Å resolution. FEBS Lett. 1976;68:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(76)80390-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Low BW, Preston HS, Sato A, Rosen LS, Searl JE, Rudko AD, Richardson JS. Three-dimensional structure of erabutoxin b neurotoxic protein: inhibitor of acetylcholine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:2991–2994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.9.2991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenwald J, Fischer WH, Vale WW, Choe S. Three-finger toxin fold for the extracellular ligand-binding domain of the type II activin receptor serine kinase. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:18–22. doi: 10.1038/4887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hart PJ, Deep S, Taylor AB, Shu Z, Hinck CS, Hinck AP. Crystal structure of the human TβR2 ectodomain–TGFβ3 complex. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:203–208. doi: 10.1038/nsb766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galat A. The three-fingered protein domain of the human genome. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3481–3493. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8473-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Einerwold J, Jaseja M, Hapner K, Webb B, Copié V. Solution structure of the carboxyl-terminal cysteine-rich domain of the VHv1.1 polydnaviral gene product: comparison with other cystine knot structural folds. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14404–14412. doi: 10.1021/bi011499s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wheeler DL, Church DM, Edgar R, Federhen S, Helmberg W, Madden TL, Pontius JU, Schuler GD, Schriml LM, Sequeira E, Suzek TO, Tatusova TA, Wagner L. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information: update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D35–D40. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altschul SF, Wootton JC, Gertz EM, Agarwala R, Morgulis A, Schäffer AA, Yu YK. Protein database searches using compositionally adjusted substitution matrices. FEBS J. 2005;272:5101–5109. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04945.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galat A. Function-dependent clustering of orthologues and paralogues of cyclophilins. Proteins Struct Funct Bioinformatics. 2004;56:808–820. doi: 10.1002/prot.20156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. ClustalW and ClustalX version 2. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galat A. On transversal hydrophobicity of some proteins and their modules. J Chem Inf Model. 2009;49:1821–1830. doi: 10.1021/ci9001316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berman HM, Henrick K, Nakamura H, Markley JL. The worldwide Protein Data Bank (wwPDB): ensuring a single, uniform archive of PDB data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D301–D303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galat A. Functional drift of sequence attributes in the FK506-binding proteins (FKBPs) J Chem Inf Mod. 2008;48:1118–1130. doi: 10.1021/ci700429n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeLano WL (2002) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. San Carlos, CA, USA, DeLano Scientific, http://pymol.sourceforge.net/ (accessed Jan 27, 2006)

- 27.Walsh CT, Stupack D, Brown JH. G protein-coupled receptors go extracellular: RhoA integrates the integrins. Mol Interv. 2008;8:165–173. doi: 10.1124/mi.8.4.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi K, Ahn YH, Gibbons DL, Tran HT, Creighton CJ, Girard L, Minna JD, Qin FX, Kurie JM. Distinct biological roles for the notch ligands Jagged-1 and Jagged-2. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:17766–17774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.003111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoffmann A, Funkner A, Neumann P, Juhnke S, Walther M, Schierhorn A, Weininger U, Balbach J, Reuter G, Stubbs MT. Biophysical characterization of refolded Drosophila Spatzle, a cystine knot protein, reveals distinct properties of three isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32598–35609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801815200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Leary JM, Hamilton JM, Deane CM, Valeyev NV, Sandell LJ, Downing AK. Solution structure and dynamics of a prototypical chordin-like cysteine-rich repeat (von Willebrand Factor type C module) from collagen IIA. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53857–53866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409225200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang JL, Huang Y, Qiu LY, Nickel J, Sebald W. von Willebrand factor type C domain-containing proteins regulate bone morphogenetic protein signaling through different recognition mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20002–20014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700456200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang JL, Qiu LY, Kotzsch A, Weidauer S, Patterson L, Hammerschmidt M, Sebald W, Mueller TD. Crystal structure analysis reveals how the Chordin family member crossveinless 2 blocks BMP-2 receptor binding. Dev Cell. 2008;14:739–750. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huson DH, Richter DC, Rausch C, Dezulian T, Franz M, Rupp R. Dendroscope: an interactive viewer for large phylogenetic trees. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:460. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Airaksinen MS, Holm L, Hatinen T. Evolution of the GDNF family ligands and receptors. Brain Behav Evol. 2006;68:181–190. doi: 10.1159/000094087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Afonso CL, Delhon G, Tulman ER, Lu Z, Zsak A, Becerra VM, Zsak L, Kutish GF, Rock DL. Genome of Deerpox virus. J Virol. 2005;79:966–977. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.966-977.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Padgett RW, Wozney JM, Gelbart WM. Human BMP sequences can confer normal dorsal-ventral patterning in the Drosophila embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2905–2909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Radaev S, Zou Z, Huang T, Lafer EM, Hinck AP, Sun PD. Ternary complex of transforming growth factor-β1 reveals isoform-specific ligand recognition and receptor recruitment in the superfamily. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14806–14814. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.079921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Groppe J, Greenwald J, Wiater E, Rodriguez-Leon J, Economides AN, Kwiatkowski W, Affolter M, Vale WW, Belmonte JC, Choe S. Structural basis of BMP signalling inhibition by the cystine knot protein Noggin. Nature. 2002;420:636–642. doi: 10.1038/nature01245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang X, Baloh RH, Milbrandt J, Garcia KC. Structure of artemin complexed with its receptor GFRα3: convergent recognition of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factors. Structure. 2006;14:1083–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiesmann C, Fuh G, Christinger HW, Eigenbrot C, Wells JA, de Vos AM. Crystal structure at 1.7 Å resolution of VEGF in complex with domain 2 of the Flt-1 receptor. Cell. 1997;91:695–704. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80456-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weber D, Kotzsch A, Nickel J, Harth S, Seher A, Mueller U, Sebald W, Mueller TD. A silent H-bond can be mutationally activated for high-affinity interaction of BMP2 and activin type IIB receptor. BMC Struct Biol. 2007;7:6–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Castro NP, Rangel MC, Nagaoka T, Salomon DS, Bianco C. Cripto-1: an embryonic gene that promotes tumorigenesis. Future Oncol. 2010;6:1127–1142. doi: 10.2217/fon.10.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rey JP, Ellies DL. Wnt modulators in the biotech pipeline. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:102–114. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fan QR, Hendrickson WA. Structure of human follicle-stimulating hormone in complex with its receptor. Nature. 2005;433:269–277. doi: 10.1038/nature03206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luo CW, Dewey EM, Sudo S, Ewer J, Hsu SY, Honegger HW, Hsueh AJ. Bursicon, the insect cuticle-hardening hormone, is a heterodimeric cystine knot protein that activates G protein-coupled receptor LGR2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2820–2825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409916102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahn Y, Sanderson BW, Klein OD, Krumlauf R. Inhibition of Wnt signaling by Wise (Sostdc1) and negative feedback from Shh controls tooth number and patterning. Development. 2010;137:3221–3231. doi: 10.1242/dev.054668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choi HY, Dieckmann M, Herz J, Niemeier A. Lrp4, a novel receptor for Dickkopf 1 and sclerostin, is expressed by osteoblasts and regulates bone growth and turnover in vivo. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lintern KB, Guidato S, Rowe A, Saldanha JW, Itasaki N. Characterization of wise protein and its molecular mechanism to interact with both Wnt and BMP signals. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:23159–23168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.025478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Florio P, Gabbanini M, Borges LE, Bonaccorsi L, Pinzauti S, Reis FM, Boy Torres P, Rago G, Litta P, Petraglia F. Activins and related proteins in the establishment of pregnancy. Reprod Sci. 2010;17:320–330. doi: 10.1177/1933719109353205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gazzerro E, Canalis E. Bone morphogenetic proteins and their antagonists. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2006;7:51–65. doi: 10.1007/s11154-006-9000-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zakin L, Carrie A, Metzinger EY, Chang C, Coffinier EM, de Robertis Development of the vertebral morphogenetic field in the mouse: interactions between crossveinless-2 and twisted gastrulation. Dev Biol. 2008;323:6–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meiniel O, Meiniel A. The complex multidomain organization of SCO-spondin protein is highly conserved in mammals. Brain Res Rev. 2007;53:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hymowitz SG, Filvaroff EH, Yin JP, Lee J, Cai L, Risser P, Maruoka M, Mao W, Foster J, Kelley RF, Pan G, Gurney AL, de Vos AM, Starovasnik MA. IL-17 s adopt a cystine knot fold: structure and activity of a novel cytokine, IL-17F, and implications for receptor binding. EMBO J. 2001;20:5332–5334. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen L, Shao Y, Huang J, Zheng J. Structural insight into the mechanisms of Wnt signaling antagonism by Dkk. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23364–23370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802375200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klein DE, Stayrook SE, Shi F, Narayan K, Lemmon MA. Structural basis for EGFR ligand sequestration by Argos. Nature. 2008;453:1271–1275. doi: 10.1038/nature06978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Drenth J, Low BW, Richardson JS, Wright CS. The toxin-agglutinin fold. A new group of small protein structures organized around a four-disulfide core. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:2652–2655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Andreeva A, Murzin AG. Structural classification of proteins and structural genomics: new insights into protein folding and evolution. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2010;66(Pt 10):1190–1197. doi: 10.1107/S1744309110007177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bryan PN, Orban J. Proteins that switch folds. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20:482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tafalla C, Aranguren R, Secombes CJ, Castrillo JL, Novoa B, Figueras A. Molecular characterisation of sea bream (Sparus aurata) transforming growth factor β1. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2003;14:405–421. doi: 10.1006/fsim.2002.0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weidauer SE, Schmieder P, Beerbaum M, Schmitz W, Oschkinat H, Mueller TD. NMR structure of the Wnt modulator protein sclerostin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;380:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Greenwald J, Vega ME, Allendorph GP, Fischer WH, Vale W, Choe S. A flexible activin explains the membrane-dependent cooperative assembly of TGFβ family receptors. Mol Cell. 2004;15:485–489. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Edson MA, Nagaraja AK, Matzuk MM. The mammalian ovary from genesis to revelation. Endocr Rev. 2009;30:624–712. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moussian B, Söding J, Schwarz H, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Retroactive, a membrane-anchored extracellular protein related to vertebrate snake neurotoxin-like proteins, is required for cuticle organization in the larva of Drosophila melanogaster . Dev Dyn. 2005;233:1056–1063. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hijazi A, Masson W, Augé B, Waltzer L, Haenlin M, Roch F. Boudin is required for septate junction organisation in Drosophila and codes for a diffusible protein of the Ly6 superfamily. Development. 2009;136:2199–2209. doi: 10.1242/dev.033845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Walsh DW, Godson C, Brazil DP, Martin F. Extracellular BMP-antagonist regulation in development and disease: tied up in knots. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:244–256. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hashimoto M, Hamada H. Translation of anterior-posterior polarity into left-right polarity in the mouse embryo. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20:433–437. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lévesque M, Gatien S, Finnson K, Desmeules S, Villiard E, Pilote M, Philip A, Roy S. Transforming growth factor: beta signaling is essential for limb regeneration in axolotls. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brockes JP, Kumar A. Comparative aspects of animal regeneration. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:525–549. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vallier L, Mendjan S, Brown S, Chng Z, Teo A, Smithers LE, Trotter MW, Cho CH, Martinez A, Rugg-Gunn P, Brons G, Pedersen RA. Activin/nodal signalling maintains pluripotency by controlling nanog expression. Development. 2009;136:1339–1349. doi: 10.1242/dev.033951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kolmar H. Engineered cystine-knot miniproteins for diagnostic applications. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2010;10:361–368. doi: 10.1586/erm.10.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin L, Gardsvoll H, Huai Q, Huang M, Ploug M. Structure-based engineering of species selectivity in the interaction between urokinase and its receptor: implication for preclinical cancer therapy. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10982–10992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.093492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Polyak K, Haviv I, Campbell IG. Co-evolution of tumor cells and their microenvironment. Trends Genet. 2009;25:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nguyen DX, Bos PD, Massagué J. Metastasis: from dissemination to organ-specific colonization. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:274–284. doi: 10.1038/nrc2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.