Abstract

Root nodule (RN) symbiosis has a unique feature in which symbiotic bacteria fix atmospheric nitrogen. The symbiosis is established with a limited species of land plants, including legumes. How RN symbiosis evolved is still a mystery, but recent findings on legumes genes that are necessary for RN symbiosis may give us a clue.

Keywords: Root nodule symbiosis, Arbuscular mycorrhiza symbiosis, Actinorhiza symbiosis, Legumes, Lotus japonicus, Medicago truncatula, Nitrogen fixation, Infection threads

Introduction

Legumes (Leguminosae, Fabaceae) are widespread species that comprise the third largest family of flowering plants [1]. Symbiosis between legumes and soil bacteria, collectively called rhizobia, is one of the most prominent beneficial plant—microbe interactions. In nodules, rhizobia fix atmospheric nitrogen to provide host plants nitrogen compounds. Root nodule (RN) symbiosis, however, is not the only form of plant—microbe interaction that accomplishes nitrogen-fixing symbiosis. Actinorhiza symbiosis, for instance, is established between Frankia bacteria and more than 200 plant species in the Eurosid I (Fabid) clade, to which legumes also belong [2]. Not all legumes have RN symbiosis. Common legumes, soybean, pea, common bean, alfalfa, etc., are all crop plants and belong to Papilionoideae, in which 90% of genera show nodulation, whereas in Caesalpinioideae, only around 5% are found to be nodulators [3]. The mode of infection is also variable in legumes [4], as in actinorhiza plants [5]. These facts, along with the phylogeny in Eurosid I, make it difficult to understand the origin of RN symbiosis.

Recent progress in molecular genetics of model legumes, i.e., Lotus japonicus and Medicago truncatula, promotes our understanding of molecular mechanisms of RN symbiosis [6]. Almost 30 symbiotic genes have been identified so far through forward genetics approaches, and more by reverse genetics. These genes have homologs in legumes and non-legumes, which makes it reasonable to compare function and structure among homologs in order to evaluate the phylogeny and evolution of nodulation. In fact, there are many reviews that have been published describing origin of nodulation based on gene function/phylogeny [7–15].

Here, we are going to focus on functional and evolutionary aspects of RN symbiosis. Not all symbiotic genes will be described, however, partly due to the fact that their non-symbiotic closest homologs are not characterized in detail, or their function is too diverse to compare (e.g., hormone signaling). Nevertheless, we hope this review will give readers insight into how plants have invented nodules, which are effective machines for nitrogen fixation.

Genes involved in perception of the symbiotic signal from bacteria

The symbiotic interaction between legumes and rhizobia is initiated by exchange of symbiotic signals from both sides. Lysin motif-containing receptor-like kinases (LysM-RLKs) are thought to perceive symbiotic signals secreted from rhizobia, lipochitin oligosaccharides (Nod factors; NFs) [16]. These putative NF receptors have been identified in several legume species, i.e., NFR1 and NFR5 in L. japonicus [17, 18] and corresponding orthologs in M. truncatula (HCL and NFP [19–21]) and pea (SYM37 and SYM10 [18, 22]). In M. truncatula, and in pea as well, both of which are in the inverted repeat-lacking clade (IRLC) [23], NFR1 orthologs HCL and SYM37 are genetically involved in a later stage of the interaction, dispensable in the earliest recognition of NFs [21, 22]. Since NFP does not show kinase activity in vitro, it is hypothesized that NFP forms a heterodimer with other LysM-RLKs [20]. The LysM domain of NFR5 determines recognition of specific NFs [24].

Among plant LysM-RLKs, CERK1 in Arabidopsis thaliana is essential for chitin signaling and induction of the plant innate immunity against fungal pathogens [25, 26]. CERK1 is presumed to perceive fungal chitin leading to a pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP)-triggered immunity response [25]. Furthermore, a plasma membrane glycoprotein CEBiP (Chitin elicitor-binding protein) in rice, which contains two extracellular LysM motifs, plays a role in chitin perception and signal transduction [27]. In addition, rice CERK1 (OsCERK1) is important for chitin signaling, likely to form hetero/homo oligomers between CEBiP [28]. Therefore, it appears that the LysM domain in plants is able to recognize chitin and chitin derivatives such as NFs.

It has been shown that LysM–RLKs have experienced further duplication and diversification in legumes, resulting in some LysM–RLKs that have acquired the function to perceive NFs from rhizobia, to establish symbiotic association [29]. Of the synteny among legumes and non-legumes, tandem duplication of NFR5 and its orthologs is conserved in legumes and poplar, but not in A. thaliana and rice, indicating that NFR5 evolution by tandem duplication has occurred in the Eurosid I clade, possibly prior to evolution of nodulation. On the contrary, gene duplication of NFR1 and its orthologs is recognized only in legumes [29]. Since LysM–RLKs are present in non-legumes, it is likely that some of the legume LysM–RLKs are involved in processes such as fungal pathogen infection, rather than the rhizobial symbiotic infection. During the evolutionary process of RN symbiosis, some LysM–RLKs are supposed to be diverged from biological defense responses to endosymbiosis. Another possibility is that some LysM–RLKs are involved in arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM) symbiosis, possibly perception of symbiotic signals from mycorrhiza. Interestingly, the M. truncatula Lyr1 gene, which is the closest paralog of Nfp in M. truncatula, is up-regulated by AM colonization of roots [30].

Genes also required by arbuscular mycorrhiza

Downstream of the Nod factor receptors, it has been demonstrated that several genes are required for generating and decoding calcium spiking, a distinctive physiological response in root hair cells detected after NF perception, and are essential for the establishment of RN symbiosis. In addition, these genes are also a prerequisite for AM symbiosis in legume plants. Therefore, it has been regarded that the intracellular signal transduction pathway is shared between RN and AM symbioses in legume plants, termed the common symbiosis (sym) pathway, and component genes in the common sym pathway are called common sym genes [13]. In the common sym pathway of L. japonicus, SYMRK, a leucine-rich-repeat receptor-like kinase [31], CASTOR and POLLUX, ion channels [32], NUP133, NUP85, and NENA, nucleoporins [33–35] have been demonstrated to be required for the induction of calcium spiking. Besides these genes, CCaMK, a calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase, which interacts with and phosphorylates CYCLOPS [36], is a putative decoder of calcium spiking leading to the establishment of RN and AM symbioses [37]. These common sym genes are also present in non-legumes such as rice, and have been shown to be essential for AM symbiosis. Additionally, some of them are conserved in symbiotic function between legume and non-legume species [38–41]. Common sym orthologs in rice, except for SYMRK, have conserved domain structures between rice and L. japonicus, and restore both RN and AM symbiosis defects in the corresponding L. japonicus mutants. On the contrary, SYMRK has undergone different evolutionary history [14]. SYMRK homologs are widely present in land plants [40]. Whereas the putative SYMRK kinase domain is well conserved among species, the extracellular domain varies its composition. SYMRK proteins in the Eurosid I and II clades have the N-terminal extracellular region and three leucine-rich repeats (LRRs), and function both in AM and RN symbioses. Interestingly, plants in Eurosid II clade do not establish RN symbiosis, so that SYMRK has been likely to be predisposed of the function for RN symbiosis. Rice and tomato, however, have different composition in SYMRK extracellular domain, which has only two LRRs. These SYMRK proteins are only functional in AM symbiosis, not in RN symbiosis [40]. Since AM symbiosis is widely accommodated in land plants, RN symbiosis has been documented to have its evolutionary origin in more ancient AM symbiosis and to have evolved by recruiting and remodeling the pre-existed common sym genes of AM symbiosis [11]. Particularly, the evolution of the SYMRK gene may be critical for mediating the recruitment of the common sym pathway from the pre-existing AM symbiosis pathway [14].

Transcription regulators downstream of the common sym

Downstream of the common sym pathway, the intracellular signal transduction pathway is split into RN or AM symbiosis-specific pathway. In the RN symbiosis-specific pathway, two GRAS proteins, NSP1 and NSP2, have been isolated and characterized as essential and specific components for RN symbiosis [42–45]. Although nsp1 and nsp2 mutants display neither infection thread (IT) growth nor RN primordium development, AM symbiosis remains intact. GRAS-domain transcription factors represent an important plant-specific transcription regulator family, and are known to play key roles in diverse biological processes, such as root development, phytohormone signal transduction, and meristem development and maintenance. The name stands for three family members, GAI, RGA, and SCR. Bioinformatic analyses show that around 30 plant species from more than 20 genera contain GRAS genes, and at least 60 and 33 GRAS genes have been identified in rice (Oryza sativa) and A. thaliana, respectively [46]. The GRAS protein family can be divided into eight subfamilies, DELLA, HAM, LISCL, PAT1, LS, SCR, SHR, and SCL3. GRAS proteins basically consist of several conserved motifs, LHRI (leucine heptad repeat I), VHIID, LHRII (leucine heptad repeat II), PFYRE, and SAW. RN symbiosis-specific GRAS proteins, NSP1, and NSP2 homologs are widely present in non-legumes, such as rice, Nicotiana benthamiana, and A. thaliana including lower plants Selaginella moellendorffii and Physcomitrella patens [44, 47]. Recently, we have shown that rice homologs of NSP1 and NSP2 perfectly restore the defects in RN symbiosis of the corresponding L. japonicus nsp1 and nsp2 mutants. These cross-species complementation analyses revealed that NSP1 and NSP2 homologs in a non-legume (rice) have been conserved in their functions beyond a legume (L. japonicus) [47]. However, the function of NSP1 and NSP2 in rice has remained elusive so far. In another model legume, M. truncatula, NSP1, and NSP2 have been shown to form a complex that is indispensable for RN symbiosis [48]. The amino acid sequence of the NSP2 interaction domain (LHRI) with NSP1 is highly conserved in NSP2 homologs through legume and non-legume species [47]. It is thus likely that the NSP1–NSP2 complex has some functions even in non-legumes. Along the course of the establishment of RN symbiosis in legumes, the NSP1–NSP2 complex may have been recruited for the signal transduction that is specific in RN symbiosis. As described above, the common sym genes are functionally conserved in a non-legume, rice, presumably because of their roles in establishing AM symbiosis. To date, some of the GRAS genes have been found to be up-regulated during AM symbiosis in L. japonicus and M. truncatula [30, 49]. Therefore, it is intriguing to hypothesize that GRAS family proteins including the NSP1–NSP2 complex are also required for the establishment of AM symbiosis. To address this hypothesis, the double mutant nsp1nsp2 may be helpful in order to perform genetic analyses to elucidate the relationship between the NSP1–NSP2 complex and AM symbiosis.

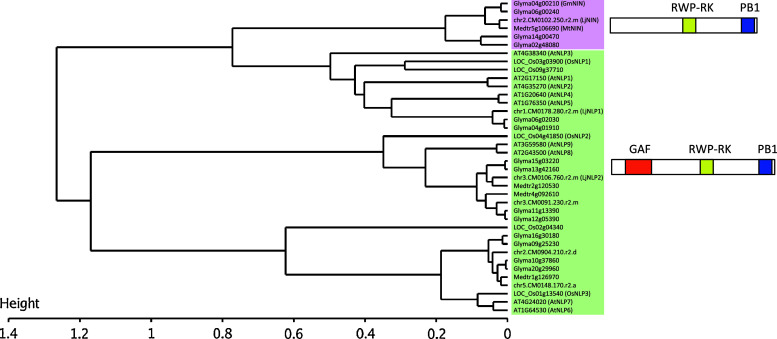

In the RN symbiosis-specific pathway, besides NSP1 and NSP2, NIN, a putative transcription factor, is also required for infection of rhizobia in root epidermis as well as for nodule organogenesis in root cortex. The nin mutants display excess root hair deformation in response to rhizobial inoculation or NF application, but neither IT growth nor RN primordium development were induced as well as nsp1 and nsp2 mutants [50]. NIN-like proteins (NLPs) are found widely among higher plants such as in A. thaliana (non-RN, non-AM species), rice, including many other species that do not develop nitrogen-fixing nodules. In NLPs, an RWP-RK domain (PF02042), whose function has been predicted to be DNA binding and dimerization, is well conserved [50, 51]. Therefore, NLPs have been presumed as transcription regulators. In addition, NLPs contain a GAF domain (PF01590) at the N terminus, which is similar to that found in phytochromes [52], cGMP-specific phosphodiesterases [53], and NifA in Azotobacter vinelandii [54]. Moreover, at the C terminus, NLPs contain a PB1 domain (PF00564), which is a protein–protein interaction domain enabling heterodimerization between the PB1 domain containing proteins [55]. Although almost all NLPs carry three of these domains (GAF, RWP-RK, and PB1), proteins in the clade including NIN (Glyma02g48080, Glyma14g00470, Glyma04g00210, Glyma06g00240, chr2.CM0102.390.nc/LjNIN, Medtr5g106690/MtNIN), lack the first conserved GAF domain (Fig. 1). In this scenario, Schauser et al. [51] pointed out the notable feature of legume NIN proteins, that is, loss of the GAF domain (domains I and II), rather than gain of structural elements, confers NIN proteins the ability to be involved in RN symbiosis. To clarify whether NLPs in non-legumes are functionally conserved for RN symbiosis, we recently carried out cross-species complementation analyses of rice NIN homolog into nin mutants of L. japonicus. In rice, there are three NLPs, and OsNLP1 is the closest one to NIN [51]. We found that OsNLP1 is not functional in L. japonicus for RN symbiosis [47], strengthening the idea that NIN has undergone specific evolution for RN symbiosis.

Fig. 1.

Clustering of NLP proteins. NLP proteins in legumes, A. thaliana and rice were clustered. Protein sequences were retrieved from Phytozome (http://www.phytozome.net/) and miyakogusa.jp (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/lotus/). Clustering was performed by SALAD Database (http://salad.dna.affrc.go.jp/salad/en/). Gene names in parentheses are according to publications [51, 128, 129]

In A. thaliana, nine NLP genes have been identified. Among them, A. thaliana NLP7 has been well characterized [56]. Regardless of nitrate supplying, nlp7 mutants show typical nitrogen-starved phenotypes. Nitrate-related genes such as nitrate assimilation genes and nitrate-induced genes are compromised in nlp7 mutants. NLP7 could thus be an important regulator involved in several nitrate-dependent processes, and given the important role of nitrate as a signal for plant growth, legumes might recruit NLPs for regulation of nodule formation in response to nitrate condition.

Regulation of nodule numbers

Although RN symbiosis is beneficial for host plant growth in nitrogen supply, excessive nodule formation could be detrimental, since nitrogen-fixing rhizobia in nodules consume a considerable amount of carbon fixed by photosynthesis. To cope with this problem, legumes utilize a negative feedback regulation for nodule formation [57–60]. This regulation is known as autoregulation of nodulation (AON). AON is inferred to consist of two long-distance signals, i.e., the root-derived signals and the shoot-derived signals. The root-derived signal is generated in roots by response to rhizobial infection subsequently translocated to shoots. On the other hand, the shoot-derived signal is generated in shoots and translocated to roots for restriction of excessive nodule formation. The AON defective mutant of L. japonicus, har1, displays an excessive nodule formation phenotype, called hyper-nodulation. The causal gene, HAR1 in L. japonicus and its orthologs in other legumes, encodes an LRR receptor-like kinase, which shows highest similarity to A. thaliana CLV1 [61–64]. CLV1 and its rice ortholog FON1 are specifically expressed in the shoot apical meristem and have been widely recognized as a critical factor for regulating the size of the shoot apical meristem [65, 66]. In contrast, the legume homolog, HAR1 is widely expressed in various organs, except for the shoot apex. To date, closer homologs of CLV1 than HAR1 have not been found in legume genome sequences. Therefore, the regulatory mechanism of the shoot apical meristem in legumes may differ from that in non-legumes. Synteny between the genomic region of the HAR1 ortholog SUNN in M. truncatula and that of CLV1 is not conserved [67]. This suggests that CLV1 is not the ortholog of the legume HAR1 orthologs. It is thus conceivable that HAR1 orthologs in legumes have gained different functions from that of CLV1 and have evolved distinctively in legumes to produce the shoot-derived signal for regulation of excessive nodule formation by receiving the root-derived signal. Another possibility is that the common ancestor of A. thaliana and legumes might have two CLV1 homologs, but one (which corresponds to HAR1) had been lost in A. thaliana [68]. Another gene controlling AON in L. japonicus, KLAVIER, shows similar functions to CLV1, in which deleterious mutation shows stem fasciation and bifurcation of pistils, which are also seen in clv1 mutants of A. thaliana [69]. KLAVIER has recently been cloned, which encodes another LRR receptor-like kinase, showing highest similarity with A. thaliana RPK2 [70]. RPK2 is important for meristem maintenance, in addition to CLV1 [71].

The unique gene controlling nodule formation

ENOD40 is induced at a very early stage of nodule initiation [72, 73]. ENOD40 was first identified in soybean [72, 74], and thereafter its homologs were identified from a number of legumes. ENOD40 is initially induced in the root pericycle within a few hours after inoculation with rhizobia. Its expression is subsequently extended to the dividing cortical cells. Over-expression of ENOD40 has been shown to exhibit extensive induction of spontaneous cortical cell division in transgenic Medicago truncatula roots [73]. Following nodule initiation, ENOD40 expression persists abundantly in the peripheral cells of vascular bundles in mature nodules [72, 74]. Therefore, the function of ENOD40 in nodule development has been implicated in triggering cortical cell division during nodule initiation and in later stages of nodule development and/or maintenance of nodule symbiosis between legumes and rhizobia. Moreover, ENOD40 expression is also detected in several non-symbiotic tissues such as roots, leaves, and flower buds [75, 76]. In addition to ENOD40 genes in legumes, Gultyaev and Roussis [77] reported that at least 39 species from 13 families in non-legumes have ENOD40 homologs. These facts indicate that in addition to symbiotic functions, ENOD40 has other common function(s) in plants and it may also have been evolutionarily recruited from another developmental mechanism into nodule development. Among non-legume ENOD40 homologs, rice ENOD40 (OsENOD40) is characterized well. In rice, expression of OsENOD40 is detected only in stems. Within the stem, presence of OsENOD40 is confined to parenchyma cells surrounding the protoxylem during the early developmental stages of lateral vascular bundles that conjoin an emerging leaf. Intriguingly, the expression pattern of OsENOD40 promoter–GUS fusion in nodules in transgenic soybean hairy roots is also detected only in peripheral cells of nodule vascular bundles in a similar way as that of soybean ENOD40 promoter–GUS fusion. Therefore, rice ENOD40 promoter activity is essentially the same as that of soybean ENOD40. Kouchi et al. [75] suggested that OsENOD40 and legume ENOD40 share common, if not identical, functions in differentiation and/or function of vascular bundles.

Common features of infection thread development

Root hairs and pollen tubes, as well as trichomes, have common features that show polar cell expansion called “tip growth”. The tip growth of plant cells is strictly regulated by the spatio-temporal accommodations of cytoskeleton organization, vesicle trafficking, and signaling by small GTPases [78]. The tip growth is a mode of polarized cell expansion in which cell wall extension and the incorporation of new cell wall material are focused at a single site on the cell surface [79]. This is an ancient process and is common in fungi, algae, and lower plants, as well as in higher plants [80].

In RN symbiosis of many, but not all legumes, rhizobia typically penetrate into host cells through plant-derived tubular structures in root hairs, ITs. The development of ITs shows an atypical tip growth in that the growing tip invaginates the cell. At the tip of the developing IT, new IT membrane and wall is progressively synthesized. In the ingrowth of the IT, rhizobial invasion is achieved toward the base of the epidermis [81]. ITs are then guided into the root cortex through pre-infection threads (PITs) [82]. Eventually, rhizobia are released into host cells through an endocytosis-like event, where they remain surrounded by host-derived membrane (i.e., peribacteroid membrane (PBM), see later section) in nodule cells [83].

The Nap1 and Pir1 genes of L. japonicus have recently been characterized as components of the SCAR/WAVE complex, and regulate rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton [84]. Rearrangement of the cytoskeleton is important for biotic interaction in plants such as RN and AM symbioses [85]. By the inhibition of rearrangements of cytoskeleton in root hair cells, the IT growth is aborted in nap1 and pir1 mutants. Thereby, nap1 and pir1 mutants cause severe inhibition of rhizobial infection, leading to the formation of ineffective nodules without colonization that take the form of bumps on roots, or small, well-formed nodules that are white due to lack of leghemoglobin expression. In most cases, rhizobia are unable to penetrate into the nap1 and pir1 nodule primordia, but instead, remain to be accumulated within root hair cells or the first cortical cell layer [84]. Thus, during rhizobial penetration, Nap1 and Pir1 have essential roles in the establishment of symbiotic intracellular accommodation. In addition, nap1 and pir1 mutants cause non-symbiotic phenotypes such as diminished root hair development and aberrant trichome formation [84]. Therefore Nap1 and Pir1 are inferred to regulate actin rearrangements of diverse phenomena in polar tip growth of plant cells.

The symbiotic mutant crinkle of L. japonicus also exhibits abnormal nodulation and alterations in root hairs, trichomes, and pollen tubes. Defective nodulation in crinkle mutants is due to aberrant IT growth. ITs are mostly arrested at the base of the epidermis, leading to the formation of bumps as in nap1 and pir1 mutants [86]. Therefore, the Crinkle gene is necessary for the proper development of ITs from epidermis to cortex. Beside the symbiotic phenotypes, crinkle mutants exhibit swollen root hairs at the base, crinkly trichomes, as well as poor pollen tube growth. The crinkle mutation also affects expansion of microspore and vacuolation of tapetal cells. Particularly, crinkle pollen showed disrupted actin organization [87]. From phenotypic characterization of crinkle mutants, it is also strongly suggested that the Crinkle gene is involved in the organization of cytoskeleton, vesicle trafficking, and/or signaling regulated by small GTPases, which are required for plant cell expansion and control cell shape and ultimately body plan.

In the context of these facts, however, AM symbiosis remains intact in nap1, pir1, and crinkle mutants. This is the common feature of IT aberrant-developing mutants. Recently, further IT mutants of L. japonicus such as cerberus [88], alb1 [89], and itd [90] have been characterized, showing that the causal genes are prerequisite for the uptake of rhizobia into root hairs and the IT growth, but not for the establishment of AM symbiosis. It is therefore possible that there is functional differentiation of genetic programs between rhizobial and mycorrhizal infection processes. In addition, nap1, pir1, and itd mutants show the induction of calcium spiking by NF application [84, 90]. Therefore, although the common sym pathway with calcium spiking is required for IT-dependent rhizobial infection, it is presumed that the common sym pathway per se is insufficient for IT-dependent rhizobial infection to host plants. Recently, it was shown that the gain-of-function CCaMK, which is a putative decoder of calcium spiking in the common sym pathway, is sufficient to induce nodule organogenesis (i.e., spontaneous nodulation), but not for IT-dependent rhizobial infection without NFR1 and NFR5 [91, 92]. Therefore, it is strongly suggested that intracellular infection of rhizobia through ITs requires another signaling pathway derived from the NF receptors, besides the common sym pathway involving calcium spiking [91, 92]. This signaling pathway is likely to regulate key components such as Nap1, Pir1, and Crinkle genes, which have roles in (re)arrangement of cytoskeleton for IT-dependent rhizobial infection to host plants. During evolution of RN symbiosis, legumes (and possibly actinorhiza plants) have recruited the common mechanism required for tip growth to the symbiosis-specific structure, ITs.

Regulation of nitrogen fixation in host plants

In “advanced” legumes, concomitantly with the IT growth in root epidermis, cell division is induced in root cortex to develop nodules. Rhizobia are released by endocytosis from ITs into nodule cells, enclosed by a symbiosis-specific membrane, the PBM, which is plant origin [93]. Rhizobia with PBM are termed symbiosomes. Rhizobia in the symbiosomes differentiate into bacteroids, which are morphologically and physiologically distinct from free-living rhizobia, and finally nitrogen fixation takes place in mature nodules. Up to now, several host genes have been demonstrated to be key components for nitrogen fixation in nodules. Among them, some genes are presumably recruited for the fulfillment of efficient nitrogen fixation activity by rhizobia during co-evolution of legume–rhizobia interaction.

Plant hemoglobins (Hbs) are widely found in land plants, in which two major types of Hbs, symbiotic (leghemoglobin, Lb) and non-symbiotic (nsHb), have been identified, which have evolved from a common ancestor [94]. Lbs are root-nodule-specific oxygen-binding heme proteins of legumes, and have been thought to play roles of both keeping low oxygen concentration in the infected cells of nodules and facilitating oxygen supply to the bacteroids for their aerobic respiration. RNAi knockdown of Lbs in L. japonicus resulted in almost complete loss of nitrogen-fixation activity, indicating an indispensable role of Lbs to support rhizobial nitrogen fixation [95]. nsHbs in legume and non-legume plants have been thought to play roles of modulating levels of nitric oxide (NO) and regulating a number of NO-dependent processes in various plant tissues [96]. In RN symbiosis, it has been shown that nsHbs play a role in scavenging NO for preventing legumes from invoking defense response by rhizobial infection [97, 98]. Furthermore, in infected cells of nodules, nsHbs play a role in elimination of NO for the augmentation of nitrogenase activity [98]. In addition, it has been shown that the plant hormone cytokinin mediates the expression of A. thaliana and rice nsHb genes [99]. Therefore, expression of Lb genes is also likely to be regulated by cytokinin, which plays important roles in RN symbiosis [100]. It is noteworthy that symbiotic Hbs in the actinorhiza plant Casuarina glauca and the caesalpinioid legume Chamaecrista fasciculata (which may have evolved nodulation independently from model papilionoid legumes) show functionally intermediate properties between Lbs and class-2 nsHbs [101, 102], indicating Lbs evolved before legume diversification. The symbiotic Hb in non-legume Parasponia andersonii, which establishes RN symbiosis with Bradyrhizobium spp., has a root-nodule-specific promoter and has evolved from class-1 nsHbs [103, 104], so that recruitment of nsHbs to symbiotic Hbs has occurred multiple times.

The Fen1 gene in L. japonicus, of which deleterious mutations show ineffective nitrogen-fixing nodules, has been identified as homocitrate synthase (HCS), which catalyzes a biosynthesis of homocitrate [105]. It is well known that homocitrate is a component of the iron–molybdenum cofactor in nitrogenase, by which nitrogen fixation takes place [106, 107]. Bacterial NifV genes also encode HCS and have been identified from various diazotrophs as an essential component of nitrogenase for nitrogen fixation [108, 109]. Although stem nodulators such as Bradyrhizobium spp. BTAi1 and ORS278 and Azorhizobium caulinodans ORS571, as well as actinorhiza nodulators Frankia have NifV homologs, most of rhizobia do not (http://genome.kazusa.or.jp/rhizobase/). Therefore, the function of FEN1 gene is presumed as the root-nodule-specific HCS in the host plants, which compensates for the lack of the NifV gene in rhizobia by supplying homocitrate to bacteroids from the host cells. At the molecular level, this compensatory mechanism is interpreted as an integral co-operation between the host plants and rhizobia for symbiotic nitrogen fixation [105]. Furthermore, the finding of FEN1 raises an important issue in considering the co-evolution of RN symbiosis. The FEN1 protein shows a high similarity to 2-isopropylmalate synthase (IPMS) identified in A. thaliana [110]. Although HCS and IPMS are different enzymes, they have similar structures and catalyze similar reactions, the transfer of an acyl group from acetyl-CoA to a 2-oxo acid for generating the alkyl group on the 2-oxo acid. However, FEN1 has an activity of HCS instead of IPMS. It is therefore conceivable that the Fen1 gene has been recruited from pre-existing housekeeping IPMS genes of the host plants during the co-evolution of RN symbiosis for the establishment of efficient nitrogen fixation with rhizobia. Although HCS is an essential component of the nitrogenase complex, HCS is not required for metabolic activities in planta. Thus, HCS could have gained the specific role of compensation for the lack of NifV in rhizobia. FEN1 provides us new insight into the co-evolution of metabolic pathways in the legume–rhizobia interaction.

In RN symbiosis, precise regulation of differentiation into bacteroids is a prerequisite for persistent nitrogen-fixation activity [111]. Recently, nodule-specific cysteine-rich (NCR) peptides were shown to be the host legume factors for the establishment of RN symbiosis. NCR peptides are members of a large cysteine cluster protein (CCP) family [112]. The CCP family is widely distributed in land plants such as Poaceae, Brassicaceae, Solanaceae, and Fabaceae [113]. Although some CCPs have signaling roles [114, 115], CCPs are mainly thought to have antimicrobial activities [113, 116]. Beside nodule-specific CCPs (i.e., NCRs) in M. truncatula, seed-specific and non-specific CCPs have been identified in legumes such as M. truncatula and soybean [112]. In M. truncatula, it has been revealed that NCRs directly promote bacteroid differentiation by induction of DNA endoreduplication [117]. Dnf1 in M. truncatula, of which mutant plants exhibit ineffective nitrogen-fixation nodules, was identified as a subunit of a signal peptidase complex specifically expressed in nodules [118]. In the dnf1 mutant nodules, bacteroid differentiation and symbiosome development are blocked, and the localization of a NCR peptide is perturbed [117]. Thus, in M. truncatula, it is likely that the host plant effectors regulate bacteroid differentiation and symbiosome development by targeting NCR peptides through the nodule-specific protein secretory pathway. NCRs are most similar to defensin-type antimicrobial peptides, which are known to inhibit cell division [119]. Therefore, the NCR gene family might have been adopted for RN symbiosis as the host plant effectors for determining the cell fate of rhizobia.

From the standpoint of co-evolution of genes in RN symbiosis, it is noteworthy that NCR genes have only been found in the IRLC legumes, such as Medicago, Pisum, and Galega species [120–122]. NCR genes form an exceptionally large family consisting of more than 300 genes in the M. truncatula genome [120, 123], and most NCR genes are clustered as multiple genes at a single locus [122]. Hence, the rapid diversification of the NCR gene family is likely due to local duplication. On the other hand, in non-IRLC legumes, such as L. japonicus and soybean, no NCR genes have yet been found. In the microsynteny between L. japonicus and M. truncatula, the flanking genomic regions of NCR genes were conserved, but NCR genes themselves were not found in the syntenic regions of L. japonicus [122]. Therefore, Alunni et al. [122] estimated that the NCR gene family should have appeared between 51 and 25 million years ago, which corresponds to the estimated times of the appearance of the most recent common ancestor of IRLC and non-IRLC legumes, and the separation of IRLC legumes, respectively [124].

Conclusions

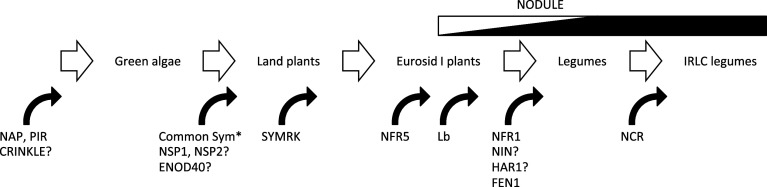

How root nodules evolved is still an enigma. Still, monophyletic origin of the predisposition for nitrogen-fixing nodule [125] indicates that in addition to recruiting pre-exiting genes, evolution of key genes such as those encoding receptors and transcription regulators, and successive co-option of the gene network [126] might commonly contribute the invention of this novel versatile organ (Fig. 2). In addition, successive evolution for improvement of nodule function, represented by proteins such as FEN1 and NCR, is still underway. It is challenging to understand how legumes have recruited portions of the gene networks required for AM symbiosis. In order to reveal the connection between RN and AM symbioses, it is necessary to identify a set of genes solely involved in AM symbiosis. Recent legume genomics and molecular genetics have contributed tremendously to the progress of understanding the molecular mechanism of RN symbiosis, but it is becoming increasingly critical for understanding the origin of nodule evolution to investigate RN symbiosis not only in legumes but also in actinorhiza plants [127]. Recent rapid progress in sequencing techniques will provide information on these non-model genomes.

Fig. 2.

Evolution of genes involved in RN symbiosis. Estimated steps of gene evolution that is sufficient in function for RN symbiosis are shown. Except for SYMRK, all of the Common Sym proteins in rice examined so far are functional for RN symbiosis in L. japonicus (asterisk). NSP1, NSP2, and ENOD40 are not yet identified in green algae. Evolution of NIN and/or HAR1 for RN symbiosis might predate legume speciation

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jeff J. Doyle (Cornell University) for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Shusei Sato (Kazusa DNA Research Institute) and Takeshi Izawa (National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences) for NLP clustering. This work was supported by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (Rice Genome Project Grant PMI-0001 to M.H.).

References

- 1.Doyle JJ, Luckow MA. The rest of the iceberg. Legume diversity and evolution in a phylogenetic context. Plant Physiol. 2003;131:900–910. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.018150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swensen SM, Mullin BC. Phylogenetic relationships among actinorhizal plants. The impact of molecular systematics and implications for the evolution of actinorhizal symbioses. Physiol Plant. 1997;99:565–573. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sprent JI. Nodulation in Legumes. Kew: Royal Botanic Gardens; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sprent JI, James EK. Legume evolution: where do nodules and mycorrhizas fit in? Plant Physiol. 2007;144:575–581. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.096156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wall LG. The actinorhizal symbiosis. J Plant Growth Regul. 2000;19:167–182. doi: 10.1007/s003440000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oldroyd GE, Downie JA. Coordinating nodule morphogenesis with rhizobial infection in legumes. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:519–546. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doyle JJ. Phylogeny of the legume family: an approach to understanding the origins of nodulation. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1994;25:325–349. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pawlowski K, Bisseling T. Rhizobial and actinorhizal symbioses: what are the shared features? Plant Cell. 1996;8:1899–1913. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doyle JJ. Phylogenetic perspectives on nodulation: evolving views of plants and symbiotic bacteria. Trends Plant Sci. 1998;3:473–478. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gualtieri G, Bisseling T. The evolution of nodulation. Plant Mol Biol. 2000;42:181–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kistner C, Parniske M. Evolution of signal transduction in intracellular symbiosis. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:511–518. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(02)02356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szczyglowski K, Amyot L. Symbiosis, inventiveness by recruitment? Plant Physiol. 2003;131:935–940. doi: 10.1104/pp.017186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parniske M. Arbuscular mycorrhiza: the mother of plant root endosymbioses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:763–775. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Markmann K, Parniske M. Evolution of root endosymbiosis with bacteria: how novel are nodules? Trends Plant Sci. 2009;14:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Held M, Hossain MS, Yokota K, Bonfante P, Stougaard J, Szczyglowski K. Common and not so common symbiotic entry. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:540–545. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spaink HP. Specific recognition of bacteria by plant LysM domain receptor kinases. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:201–204. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radutoiu S, Madsen LH, Madsen EB, Felle HH, Umehara Y, Gronlund M, Sato S, Nakamura Y, Tabata S, Sandal N, Stougaard J. Plant recognition of symbiotic bacteria requires two LysM receptor-like kinases. Nature. 2003;425:585–592. doi: 10.1038/nature02039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madsen EB, Madsen LH, Radutoiu S, Olbryt M, Rakwalska M, Szczyglowski K, Sato S, Kaneko T, Tabata S, Sandal N, Stougaard J. A receptor kinase gene of the LysM type is involved in legume perception of rhizobial signals. Nature. 2003;425:637–640. doi: 10.1038/nature02045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Limpens E, Franken C, Smit P, Willemse J, Bisseling T, Geurts R. LysM domain receptor kinases regulating rhizobial Nod factor-induced infection. Science. 2003;302:630–633. doi: 10.1126/science.1090074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arrighi JF, Barre A, Ben Amor B, Bersoult A, Soriano LC, Mirabella R, de Carvalho-Niebel F, Journet EP, Gherardi M, Huguet T, Geurts R, Denarie J, Rouge P, Gough C. The Medicago truncatula lysin motif-receptor-like kinase gene family includes NFP and new nodule-expressed genes. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:265–279. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.084657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smit P, Limpens E, Geurts R, Fedorova E, Dolgikh E, Gough C, Bisseling T. Medicago LYK3, an entry receptor in rhizobial nodulation factor signaling. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:183–191. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.100495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhukov V, Radutoiu S, Madsen LH, Rychagova T, Ovchinnikova E, Borisov A, Tikhonovich I, Stougaard J. The pea Sym37 receptor kinase gene controls infection-thread initiation and nodule development. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2008;21:1600–1608. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-12-1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doyle JJ, Doyle JL, Ballenger JA, Dickson EE, Kajita T, Ohashi H. A phylogeny of the chloroplast gene rbcL in the Leguminosae: taxonomic correlations and insights into the evolution of nodulation. Am J Bot. 1997;84:541–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radutoiu S, Madsen LH, Madsen EB, Jurkiewicz A, Fukai E, Quistgaard EM, Albrektsen AS, James EK, Thirup S, Stougaard J. LysM domains mediate lipochitin-oligosaccharide recognition and Nfr genes extend the symbiotic host range. EMBO J. 2007;26:3923–3935. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miya A, Albert P, Shinya T, Desaki Y, Ichimura K, Shirasu K, Narusaka Y, Kawakami N, Kaku H, Shibuya N. CERK1, a LysM receptor kinase, is essential for chitin elicitor signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19613–19618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705147104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wan J, Zhang XC, Neece D, Ramonell KM, Clough S, Kim SY, Stacey MG, Stacey G. A LysM receptor-like kinase plays a critical role in chitin signaling and fungal resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008;20:471–481. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.056754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaku H, Nishizawa Y, Ishii-Minami N, Akimoto-Tomiyama C, Dohmae N, Takio K, Minami E, Shibuya N. Plant cells recognize chitin fragments for defense signaling through a plasma membrane receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11086–11091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508882103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimizu T, Nakano T, Takamizawa D, Desaki Y, Ishii-Minami N, Nishizawa Y, Minami E, Okada K, Yamane H, Kaku H, Shibuya N. Two LysM receptor molecules, CEBiP and OsCERK1, cooperatively regulate chitin elicitor signaling in rice. Plant J. 2010;64:204–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang XC, Wu X, Findley S, Wan J, Libault M, Nguyen HT, Cannon SB, Stacey G. Molecular evolution of lysin motif-type receptor-like kinases in plants. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:623–636. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.097097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gomez SK, Javot H, Deewatthanawong P, Torres-Jerez I, Tang Y, Blancaflor EB, Udvardi MK, Harrison MJ. Medicago truncatula and Glomus intraradices gene expression in cortical cells harboring arbuscules in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. BMC Plant Biol. 2009;9:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stracke S, Kistner C, Yoshida S, Mulder L, Sato S, Kaneko T, Tabata S, Sandal N, Stougaard J, Szczyglowski K, Parniske M. A plant receptor-like kinase required for both bacterial and fungal symbiosis. Nature. 2002;417:959–962. doi: 10.1038/nature00841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Imaizumi-Anraku H, Takeda N, Charpentier M, Perry J, Miwa H, Umehara Y, Kouchi H, Murakami Y, Mulder L, Vickers K, Pike J, Downie JA, Wang T, Sato S, Asamizu E, Tabata S, Yoshikawa M, Murooka Y, Wu GJ, Kawaguchi M, Kawasaki S, Parniske M, Hayashi M. Plastid proteins crucial for symbiotic fungal and bacterial entry into plant roots. Nature. 2005;433:527–531. doi: 10.1038/nature03237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanamori N, Madsen LH, Radutoiu S, Frantescu M, Quistgaard EM, Miwa H, Downie JA, James EK, Felle HH, Haaning LL, Jensen TH, Sato S, Nakamura Y, Tabata S, Sandal N, Stougaard J. A nucleoporin is required for induction of Ca2+ spiking in legume nodule development and essential for rhizobial and fungal symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:359–364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508883103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saito K, Yoshikawa M, Yano K, Miwa H, Uchida H, Asamizu E, Sato S, Tabata S, Imaizumi-Anraku H, Umehara Y, Kouchi H, Murooka Y, Szczyglowski K, Downie JA, Parniske M, Hayashi M, Kawaguchi M. NUCLEOPORIN85 is required for calcium spiking, fungal and bacterial symbioses, and seed production in Lotus japonicus . Plant Cell. 2007;19:610–624. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.046938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Groth M, Takeda N, Perry J, Uchida H, Draxl S, Brachmann A, Sato S, Tabata S, Kawaguchi M, Wang TL, Parniske M. NENA, a Lotus japonicus Homolog of Sec13, is required for rhizodermal infection by Arbuscular Mycorrhiza fungi and rhizobia but dispensable for cortical endosymbiotic development. Plant Cell. 2010;22:2509–2526. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.069807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yano K, Yoshida S, Muller J, Singh S, Banba M, Vickers K, Markmann K, White C, Schuller B, Sato S, Asamizu E, Tabata S, Murooka Y, Perry J, Wang TL, Kawaguchi M, Imaizumi-Anraku H, Hayashi M, Parniske M. CYCLOPS, a mediator of symbiotic intracellular accommodation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20540–20545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806858105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tirichine L, Imaizumi-Anraku H, Yoshida S, Murakami Y, Madsen LH, Miwa H, Nakagawa T, Sandal N, Albrektsen AS, Kawaguchi M, Downie A, Sato S, Tabata S, Kouchi H, Parniske M, Kawasaki S, Stougaard J. Deregulation of a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase leads to spontaneous nodule development. Nature. 2006;441:1153–1156. doi: 10.1038/nature04862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Godfroy O, Debelle F, Timmers T, Rosenberg C. A rice calcium- and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase restores nodulation to a legume mutant. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2006;19:495–501. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen C, Gao M, Liu J, Zhu H. Fungal symbiosis in rice requires an ortholog of a legume common symbiosis gene encoding a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:1619–1628. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.109876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Markmann K, Giczey G, Parniske M. Functional adaptation of a plant receptor-kinase paved the way for the evolution of intracellular root symbioses with bacteria. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e68. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Banba M, Gutjahr C, Miyao A, Hirochika H, Paszkowski U, Kouchi H, Imaizumi-Anraku H. Divergence of evolutionary ways among common sym genes: CASTOR and CCaMK show functional conservation between two symbiosis systems and constitute the root of a common signaling pathway. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008;49:1659–1671. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smit P, Raedts J, Portyanko V, Debelle F, Gough C, Bisseling T, Geurts R. NSP1 of the GRAS protein family is essential for rhizobial nod factor-induced transcription. Science. 2005;308:1789–1791. doi: 10.1126/science.1111025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalo P, Gleason C, Edwards A, Marsh J, Mitra RM, Hirsch S, Jakab J, Sims S, Long SR, Rogers J, Kiss GB, Downie JA, Oldroyd GE. Nodulation signaling in legumes requires NSP2, a member of the GRAS family of transcriptional regulators. Science. 2005;308:1786–1789. doi: 10.1126/science.1110951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heckmann AB, Lombardo F, Miwa H, Perry JA, Bunnewell S, Parniske M, Wang TL, Downie JA. Lotus japonicus nodulation requires two GRAS domain regulators, one of which is functionally conserved in a non-legume. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:1739–1750. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.089508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murakami Y, Miwa H, Imaizumi-Anraku H, Kouchi H, Downie JA, Kawaguchi M, Kawasaki S. Positional cloning identifies Lotus japonicus NSP2, a putative transcription factor of the GRAS family, required for NIN and ENOD40 gene expression in nodule initiation. DNA Res. 2006;13:255–265. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsl017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hirsch S, Oldroyd GE. GRAS-domain transcription factors that regulate plant development. Plant Signal Behav. 2009;4:698–700. doi: 10.4161/psb.4.8.9176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yokota K, Soyano T, Kouchi H, Hayashi M. Function of GRAS proteins in root nodule symbiosis is retained in homologs of a non-legume, rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51:1436–1442. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hirsch S, Kim J, Munoz A, Heckmann AB, Downie JA, Oldroyd GE. GRAS proteins form a DNA binding complex to induce gene expression during nodulation signaling in Medicago truncatula . Plant Cell. 2009;21:545–557. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guether M, Balestrini R, Hannah M, He J, Udvardi MK, Bonfante P. Genome-wide reprogramming of regulatory networks, transport, cell wall and membrane biogenesis during arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in Lotus japonicus . New Phytol. 2009;182:200–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schauser L, Roussis A, Stiller J, Stougaard J. A plant regulator controlling development of symbiotic root nodules. Nature. 1999;402:191–195. doi: 10.1038/46058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schauser L, Wieloch W, Stougaard J. Evolution of NIN-like proteins in Arabidopsis, rice, and Lotus japonicus . J Mol Evol. 2005;60:229–237. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aravind L, Ponting CP. The GAF domain: an evolutionary link between diverse phototransducing proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:458–459. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rybalkin SD, Rybalkina IG, Shimizu-Albergine M, Tang XB, Beavo JA. PDE5 is converted to an activated state upon cGMP binding to the GAF A domain. EMBO J. 2003;22:469–478. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Little R, Dixon R. The amino-terminal GAF domain of Azotobacter vinelandii NifA binds 2-oxoglutarate to resist inhibition by NifL under nitrogen-limiting conditions. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28711–28718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301992200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ponting CP, Ito T, Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT, Inagaki F, Sumimoto H. OPR, PC and AID: all in the PB1 family. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:10. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)02006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Castaings L, Camargo A, Pocholle D, Gaudon V, Texier Y, Boutet-Mercey S, Taconnat L, Renou JP, Daniel-Vedele F, Fernandez E, Meyer C, Krapp A. The nodule inception-like protein 7 modulates nitrate sensing and metabolism in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2009;57:426–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nutman PS. Host-factors influencing infection and nodule development in leguminous plants. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1952;139:176–185. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1952.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pierce M, Bauer WD. A rapid regulatory response governing nodulation in soybean. Plant Physiol. 1983;73:286–290. doi: 10.1104/pp.73.2.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kosslak RM, Bohlool BB. Suppression of nodule development of one side of a split-root system of soybeans caused by prior inoculation of the other side. Plant Physiol. 1984;75:125–130. doi: 10.1104/pp.75.1.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Malik NS, Bauer WD. When does the self-regulatory response elicited in soybean root after inoculation occur? Plant Physiol. 1988;88:537–539. doi: 10.1104/pp.88.3.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Krusell L, Madsen LH, Sato S, Aubert G, Genua A, Szczyglowski K, Duc G, Kaneko T, Tabata S, de Bruijn F, Pajuelo E, Sandal N, Stougaard J. Shoot control of root development and nodulation is mediated by a receptor-like kinase. Nature. 2002;420:422–426. doi: 10.1038/nature01207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nishimura R, Hayashi M, Wu GJ, Kouchi H, Imaizumi-Anraku H, Murakami Y, Kawasaki S, Akao S, Ohmori M, Nagasawa M, Harada K, Kawaguchi M. HAR1 mediates systemic regulation of symbiotic organ development. Nature. 2002;420:426–429. doi: 10.1038/nature01231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Searle IR, Men AE, Laniya TS, Buzas DM, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Carroll BJ, Gresshoff PM. Long-distance signaling in nodulation directed by a CLAVATA1-like receptor kinase. Science. 2003;299:109–112. doi: 10.1126/science.1077937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oka-Kira E, Kawaguchi M. Long-distance signaling to control root nodule number. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2006;9:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clark SE, Williams RW, Meyerowitz EM. The CLAVATA1 gene encodes a putative receptor kinase that controls shoot and floral meristem size in Arabidopsis. Cell. 1997;89:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80239-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suzaki T, Sato M, Ashikari M, Miyoshi M, Nagato Y, Hirano HY. The gene FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER1 regulates floral meristem size in rice and encodes a leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase orthologous to Arabidopsis CLAVATA1. Development. 2004;131:5649–5657. doi: 10.1242/dev.01441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schnabel E, Journet EP, de Carvalho-Niebel F, Duc G, Frugoli J. The Medicago truncatula SUNN gene encodes a CLV1-like leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase that regulates nodule number and root length. Plant Mol Biol. 2005;58:809–822. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-8102-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morillo SA, Tax FE. Functional analysis of receptor-like kinases in monocots and dicots. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2006;9:460–469. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oka-Kira E, Tateno K, Miura K, Haga T, Hayashi M, Harada K, Sato S, Tabata S, Shikazono N, Tanaka A, Watanabe Y, Fukuhara I, Nagata T, Kawaguchi M. klavier (klv), a novel hypernodulation mutant of Lotus japonicus affected in vascular tissue organization and floral induction. Plant J. 2005;44:505–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miyazawa H, Oka-Kira E, Sato N, Takahashi H, Wu GJ, Sato S, Hayashi M, Betsuyaku S, Nakazono M, Tabata S, Harada K, Sawa S, Fukuda H, Kawaguchi M. The receptor-like kinase KLAVIER mediates systemic regulation of nodulation and non-symbiotic shoot development in Lotus japonicus . Development. 2010;137:4317–4325. doi: 10.1242/dev.058891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kinoshita A, Betsuyaku S, Osakabe Y, Mizuno S, Nagawa S, Stahl Y, Simon R, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Fukuda H, Sawa S. RPK2 is an essential receptor-like kinase that transmits the CLV3 signal in Arabidopsis. Development. 2010;137:3911–3920. doi: 10.1242/dev.048199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kouchi H, Hata S. Isolation and characterization of novel nodulin cDNAs representing genes expressed at early stages of soybean nodule development. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;238:106–119. doi: 10.1007/BF00279537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Charon C, Johansson C, Kondorosi E, Kondorosi A, Crespi M. enod40 induces dedifferentiation and division of root cortical cells in legumes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8901–8906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang WC, Katinakis P, Hendriks P, Smolders A, de Vries F, Spee J, van Kammen A, Bisseling T, Franssen H. Characterization of GmENOD40, a gene showing novel patterns of cell-specific expression during soybean nodule development. Plant J. 1993;3:573–585. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1993.03040573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kouchi H, Takane K, So RB, Ladha JK, Reddy PM. Rice ENOD40: isolation and expression analysis in rice and transgenic soybean root nodules. Plant J. 1999;18:121–129. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Takeda N, Okamoto S, Hayashi M, Murooka Y. Expression of LjENOD40 genes in response to symbiotic and non-symbiotic signals: LjENOD40–1 and LjENOD40–2 are differentially regulated in Lotus japonicus . Plant Cell Physiol. 2005;46:1291–1298. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gultyaev AP, Roussis A. Identification of conserved secondary structures and expansion segments in enod40 RNAs reveals new enod40 homologues in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3144–3152. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cole RA, Fowler JE. Polarized growth: maintaining focus on the tip. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2006;9:579–588. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Smith LG. Cytoskeletal control of plant cell shape: getting the fine points. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2003;6:63–73. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(02)00012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Geitmann A, Emons AM. The cytoskeleton in plant and fungal cell tip growth. J Microsc. 2000;198:218–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.2000.00702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gage DJ, Margolin W. Hanging by a thread: invasion of legume plants by rhizobia. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000;3:613–617. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.van Brussel AA, Bakhuizen R, van Spronsen PC, Spaink HP, Tak T, Lugtenberg BJ, Kijne JW. Induction of pre-infection thread structures in the leguminous host plant by mitogenic lipo-oligosaccharides of Rhizobium . Science. 1992;257:70–72. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5066.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brewin NJ. Plant cell wall remodelling in the rhizobium–legume symbiosis. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2004;23:293–316. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yokota K, Fukai E, Madsen LH, Jurkiewicz A, Rueda P, Radutoiu S, Held M, Hossain MS, Szczyglowski K, Morieri G, Oldroyd GE, Downie JA, Nielsen MW, Rusek AM, Sato S, Tabata S, James EK, Oyaizu H, Sandal N, Stougaard J. Rearrangement of actin cytoskeleton mediates invasion of Lotus japonicus roots by Mesorhizobium loti . Plant Cell. 2009;21:267–284. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.063693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Takemoto D, Hardham AR. The cytoskeleton as a regulator and target of biotic interactions in plants. Plant Physiol. 2004;136:3864–3876. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.052159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tansengco ML, Hayashi M, Kawaguchi M, Imaizumi-Anraku H, Murooka Y. crinkle, a novel symbiotic mutant that affects the infection thread growth and alters the root hair, trichome, and seed development in Lotus japonicus. Plant Physiol. 2003;131:1054–1063. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.017020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tansengco ML, Imaizumi-Anraku H, Yoshikawa M, Takagi S, Kawaguchi M, Hayashi M, Murooka Y. Pollen development and tube growth are affected in the symbiotic mutant of Lotus japonicus, crinkle. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;45:511–520. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yano K, Shibata S, Chen WL, Sato S, Kaneko T, Jurkiewicz A, Sandal N, Banba M, Imaizumi-Anraku H, Kojima T, Ohtomo R, Szczyglowski K, Stougaard J, Tabata S, Hayashi M, Kouchi H, Umehara Y. CERBERUS, a novel U-box protein containing WD-40 repeats, is required for formation of the infection thread and nodule development in the legume–rhizobium symbiosis. Plant J. 2009;60:168–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yano K, Tansengco ML, Hio T, Higashi K, Murooka Y, Imaizumi-Anraku H, Kawaguchi M, Hayashi M. New nodulation mutants responsible for infection thread development in Lotus japonicus . Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2006;19:801–810. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lombardo F, Heckmann AB, Miwa H, Perry JA, Yano K, Hayashi M, Parniske M, Wang TL, Downie JA. Identification of symbiotically defective mutants of Lotus japonicus affected in infection thread growth. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2006;19:1444–1450. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Madsen LH, Tirichine L, Jurkiewicz A, Sullivan JT, Heckmann AB, Bek AS, Ronson CW, James EK, Stougaard J. The molecular network governing nodule organogenesis and infection in the model legume Lotus japonicus . Nat Commun. 2010;1:1–12. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hayashi T, Banba M, Shimoda Y, Kouchi H, Hayashi M, Imaizumi-Anraku H. A dominant function of CCaMK in intracellular accommodation of bacterial and fungal endosymbionts. Plant J. 2010;63:141–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Udvardi MK, Day DA. Metabolite transport across symbiotic membranes of legume nodules. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1997;48:493–523. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Garrocho-Villegas V, Gopalasubramaniam SK, Arredondo-Peter R. Plant hemoglobins: what we know six decades after their discovery. Gene. 2007;398:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ott T, van Dongen JT, Gunther C, Krusell L, Desbrosses G, Vigeolas H, Bock V, Czechowski T, Geigenberger P, Udvardi MK. Symbiotic leghemoglobins are crucial for nitrogen fixation in legume root nodules but not for general plant growth and development. Curr Biol. 2005;15:531–535. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dordas C. Nonsymbiotic hemoglobins and stress tolerance in plants. Plant Sci. 2009;176:433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shimoda Y, Nagata M, Suzuki A, Abe M, Sato S, Kato T, Tabata S, Higashi S, Uchiumi T. Symbiotic rhizobium and nitric oxide induce gene expression of non-symbiotic hemoglobin in Lotus japonicus . Plant Cell Physiol. 2005;46:99–107. doi: 10.1093/pci/pci001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shimoda Y, Shimoda-Sasakura F, Kucho K, Kanamori N, Nagata M, Suzuki A, Abe M, Higashi S, Uchiumi T. Overexpression of class 1 plant hemoglobin genes enhances symbiotic nitrogen fixation activity between Mesorhizobium loti and Lotus japonicus . Plant J. 2009;57:254–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hunt PW, Watts RA, Trevaskis B, Llewelyn DJ, Burnell J, Dennis ES, Peacock WJ. Expression and evolution of functionally distinct haemoglobin genes in plants. Plant Mol Biol. 2001;47:677–692. doi: 10.1023/a:1012440926982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Frugier F, Kosuta S, Murray JD, Crespi M, Szczyglowski K. Cytokinin: secret agent of symbiosis. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Guldner E, Godelle B, Galtier N. Molecular adaptation in plant hemoglobin, a duplicated gene involved in plant–bacteria symbiosis. J Mol Evol. 2004;59:416–425. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-2632-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gopalasubramaniam SK, Kovacs F, Violante-Mota F, Twigg P, Arredondo-Peter R, Sarath G. Cloning and characterization of a caesalpinoid (Chamaecrista fasciculata) hemoglobin: the structural transition from a nonsymbiotic hemoglobin to a leghemoglobin. Proteins. 2008;72:252–260. doi: 10.1002/prot.21917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Franche C, Diouf D, Laplaze L, Auguy F, Frutz T, Rio M, Duhoux E, Bogusz D. Soybean (lbc3), Parasponia, and Trema hemoglobin gene promoters retain symbiotic and nonsymbiotic specificity in transgenic Casuarinaceae: implications for hemoglobin gene evolution and root nodule symbioses. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1998;11:887–894. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sturms R, Kakar S, Trent J, 3rd, Hargrove MS. Trema and Parasponia hemoglobins reveal convergent evolution of oxygen transport in plants. Biochemistry. 2010;49:4085–4093. doi: 10.1021/bi1002844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hakoyama T, Niimi K, Watanabe H, Tabata R, Matsubara J, Sato S, Nakamura Y, Tabata S, Jichun L, Matsumoto T, Tatsumi K, Nomura M, Tajima S, Ishizaka M, Yano K, Imaizumi-Anraku H, Kawaguchi M, Kouchi H, Suganuma N. Host plant genome overcomes the lack of a bacterial gene for symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Nature. 2009;462:514–517. doi: 10.1038/nature08594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hoover TR, Robertson AD, Cerny RL, Hayes RN, Imperial J, Shah VK, Ludden PW. Identification of the V factor needed for synthesis of the iron-molybdenum cofactor of nitrogenase as homocitrate. Nature. 1987;329:855–857. doi: 10.1038/329855a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hoover TR, Imperial J, Ludden PW, Shah VK. Homocitrate is a component of the iron–molybdenum cofactor of nitrogenase. Biochemistry. 1989;28:2768–2771. doi: 10.1021/bi00433a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hoover TR, Imperial J, Ludden PW, Shah VK. Homocitrate cures the NifV-phenotype in Klebsiella pneumoniae . J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1978–1979. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1978-1979.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zheng L, White RH, Dean DR. Purification of the Azotobacter vinelandii nifV-encoded homocitrate synthase. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5963–5966. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5963-5966.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.de Kraker JW, Luck K, Textor S, Tokuhisa JG, Gershenzon J. Two Arabidopsis genes (IPMS1 and IPMS2) encode isopropylmalate synthase, the branchpoint step in the biosynthesis of leucine. Plant Physiol. 2007;143:970–986. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.085555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Oke V, Long SR. Bacteroid formation in the rhizobium–legume symbiosis. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:641–646. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)00035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Graham MA, Silverstein KA, Cannon SB, VandenBosch KA. Computational identification and characterization of novel genes from legumes. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:1179–1197. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.037531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Silverstein KA, Graham MA, Paape TD, VandenBosch KA. Genome organization of more than 300 defensin-like genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:600–610. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.060079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Schopfer CR, Nasrallah ME, Nasrallah JB. The male determinant of self-incompatibility in Brassica . Science. 1999;286:1697–1700. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Okuda S, Tsutsui H, Shiina K, Sprunck S, Takeuchi H, Yui R, Kasahara RD, Hamamura Y, Mizukami A, Susaki D, Kawano N, Sakakibara T, Namiki S, Itoh K, Otsuka K, Matsuzaki M, Nozaki H, Kuroiwa T, Nakano A, Kanaoka MM, Dresselhaus T, Sasaki N, Higashiyama T. Defensin-like polypeptide LUREs are pollen tube attractants secreted from synergid cells. Nature. 2009;458:357–361. doi: 10.1038/nature07882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Silverstein KA, Graham MA, VandenBosch KA. Novel paralogous gene families with potential function in legume nodules and seeds. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2006;9:142–146. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Van de Velde W, Zehirov G, Szatmari A, Debreczeny M, Ishihara H, Kevei Z, Farkas A, Mikulass K, Nagy A, Tiricz H, Satiat-Jeunemaitre B, Alunni B, Bourge M, Kucho K, Abe M, Kereszt A, Maroti G, Uchiumi T, Kondorosi E, Mergaert P. Plant peptides govern terminal differentiation of bacteria in symbiosis. Science. 2010;327:1122–1126. doi: 10.1126/science.1184057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wang D, Griffitts J, Starker C, Fedorova E, Limpens E, Ivanov S, Bisseling T, Long S. A nodule-specific protein secretory pathway required for nitrogen-fixing symbiosis. Science. 2010;327:1126–1129. doi: 10.1126/science.1184096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Brogden KA. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:238–250. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mergaert P, Nikovics K, Kelemen Z, Maunoury N, Vaubert D, Kondorosi A, Kondorosi E. A novel family in Medicago truncatula consisting of more than 300 nodule-specific genes coding for small, secreted polypeptides with conserved cysteine motifs. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:161–173. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.018192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wojciechowski MF, Lavin M, Sanderson MJ. A phylogeny of legumes (Leguminosae) based on analysis of the plastid matK gene resolves many well-supported subclades within the family. Am J Bot. 2004;91:1846–1862. doi: 10.3732/ajb.91.11.1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Alunni B, Kevei Z, Redondo-Nieto M, Kondorosi A, Mergaert P, Kondorosi E. Genomic organization and evolutionary insights on GRP and NCR genes, two large nodule-specific gene families in Medicago truncatula . Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2007;20:1138–1148. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-9-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Fedorova M, van de Mortel J, Matsumoto PA, Cho J, Town CD, VandenBosch KA, Gantt JS, Vance CP. Genome-wide identification of nodule-specific transcripts in the model legume Medicago truncatula . Plant Physiol. 2002;130:519–537. doi: 10.1104/pp.006833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lavin M, Herendeen PS, Wojciechowski MF. Evolutionary rates analysis of Leguminosae implicates a rapid diversification of lineages during the tertiary. Syst Biol. 2005;54:575–594. doi: 10.1080/10635150590947131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Morgan DR, Swensen SM, Mullin BC, Dowd JM, Martin PG. Chloroplast gene sequence data suggest a single origin of the predisposition for symbiotic nitrogen fixation in angiosperms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2647–2651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Monteiro A, Podlaha O. Wings, horns, and butterfly eyespots: how do complex traits evolve? PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e37. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Pawlowski K, Newton WE. Nitrogen-fixing actinorhizal symbioses. Berlin Heidelberg New York: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Marsh JF, Rakocevic A, Mitra RM, Brocard L, Sun J, Eschstruth A, Long SR, Schultze M, Ratet P, Oldroyd GE. Medicago truncatula NIN is essential for rhizobial-independent nodule organogenesis induced by autoactive calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:324–335. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.093021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Libault M, Farmer A, Brechenmacher L, Drnevich J, Langley RJ, Bilgin DD, Radwan O, Neece DJ, Clough SJ, May GD, Stacey G. Complete transcriptome of the soybean root hair cell, a single-cell model, and its alteration in response to Bradyrhizobium japonicum infection. Plant Physiol. 2010;152:541–552. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.148379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]