Abstract

Insect odorant binding proteins (OBPs) are the first components of the olfactory system to encounter and bind attractant and repellent odors emanating from various sources for presentation to olfactory receptors, which trigger relevant signal transduction cascades culminating in specific physiological and behavioral responses. For disease vectors, particularly hematophagous mosquitoes, repellents represent important defenses against parasitic diseases because they effect a reduction in the rate of contact between the vectors and humans. OBPs are targets for structure-based rational approaches for the discovery of new repellent or other olfaction inhibitory compounds with desirable features. Thus, a study was conducted to characterize the high resolution crystal structure of an OBP of Anopheles gambiae, the African malaria mosquito vector, in complex with N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET), one of the most effective repellents that has been in worldwide use for six decades. We found that DEET binds at the edge of a long hydrophobic tunnel by exploiting numerous non-polar interactions and one hydrogen bond, which is perceived to be critical for DEET’s recognition. Based on the experimentally determined affinity of AgamOBP1 for DEET (K d of 31.3 μΜ) and our structural data, we modeled the interactions for this protein with 29 promising leads reported in the literature to have significant repellent activities, and carried out fluorescence binding studies with four highly ranked ligands. Our experimental results confirmed the modeling predictions indicating that structure-based modeling could facilitate the design of novel repellents with enhanced binding affinity and selectivity.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00018-011-0745-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Crystal structure, Molecular modeling, AgamOBP1, DEET, Malaria

Introduction

A number of potentially lethal diseases, including encephalitis, yellow fever and malaria, are transmitted by blood-feeding insects. Amongst them, the most deadly tropical disease is malaria. According to the World Health Organization, in 2008, 247 million malaria infections were diagnosed causing the death of 863,000 people, mainly children under the age of 5 [1]. Malaria is transmitted to humans by female mosquitoes, particularly Anopheles gambiae, carrying the pathogen parasite Plasmodium falciparum in their saliva. Current research efforts are focused on the development of new drugs for the disease [2], development of vaccines against the parasite [2, 3], and mosquito vector transgenesis for the generation of mosquitoes refractive to parasite infection, multiplication and/or development [4, 5]. To date, however, the most successful approaches for control of malaria transmission have been based on methods that aimed at a reduction of the frequency of contact between the mosquito vectors and their human targets.

Second to insecticides, which represent a serious burden for the environment and human health [6, 7], and whose prolonged use results in the selection of resistant vector populations [8], mosquito repellents are the most commonly used agents for prevention of infection by keeping infected mosquitoes away from human targets and preventing an infected human from spreading the parasite to uninfected mosquitoes [9]. At present, a synthetic carboxamide discovered in 1946 [10], N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET), is the most widely used insect repellent [11], and it has proved to be effective against a broad spectrum of insects, including mosquitoes, black flies, chiggers, ticks, bedbugs and fleas [9]. Besides its repellent action, DEET has been reported to possess larvicidal and adulticidal activities against mosquitoes [12].

Surprisingly, after five decades of use, the molecular targets of DEET have remained poorly characterized making its mechanism of action a controversial matter [13]. Early behavioral studies have suggested that DEET acts on olfactory neurons (ONs) of mosquitoes and decreases their sensitivity to lactic acid [14]. Later studies have provided evidence that DEET targets the function of insect odorant receptors (ORs) and, in the case of mosquitoes, blocks an OR/co-receptor complex which is involved in the recognition of 1-octen-3-ol, a component of human sweat [15]. However, another recent study proposes that mosquitoes have the ability to smell and avoid DEET through a specific DEET-sensitive olfactory receptor neuron (ORN), housed in a trichoid sensillum, without inhibiting the reception of other chemical signals such as CO2, lactic acid or 1-octen-3-ol [16].

Parallel to the success and widespread use of DEET, a significant effort is devoted nowadays toward the discovery of new insect repellents with improved characteristics, which include reduced toxicity [17, 18] and wider activity against DEET-insensitive vectors [19] or species that develop resistance to DEET [19].

To date, the most promising new repellent product, and the only one more effective than DEET, has been butan-2-yl 2-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (Picaridin or KBR3023) developed in the mid-1990s [20, 21]. However, as with most existing repellents, animal tests showed a tendency for picaridin to cause skin irritation [22]. Additionally, all currently used repellents, including DEET, become ineffective a few hours after their application. Therefore, the need for new more effective repellents is evident.

DEET and picaridin share similar structural motifs that might be useful for the development of new repellents [23]. To date, a number of QSAR studies of carboxamides [24–26] and piperidines [27] have been employed for the development of more efficient and environmentally friendly repellents and insecticides. However, in the absence of structural data on repellents in complex with a macromolecular target, a rational structure-based design approach by necessity has yet to be realized.

The number of candidate genes for such a structure-based approach that targets the olfactory system consistently grows, especially after the completion of the genome sequences of several insect species including Drosophila melanogaster [28] and A. gambiae [29]. Several protein classes have been identified to be involved in olfactory processes, including insect olfactory receptors (ORs) and 83b sub-type receptors [30, 31], odorant binding proteins (OBPs) [32], sensory neuron membrane proteins (SNMP) [33, 34], arrestins [35] and degrading enzymes [36–39]. Despite the fact that ORs are considered as the gold standard in the quest for new insect repellents, the necessary structural information for their exploitation as targets for structure-based design is still missing. Among the other putative targets, the fact that OBPs are so far the best characterized olfactory macromolecules makes them appealing targets for structural studies.

Insect OBPs are divided into three main classes: pheromone binding proteins (PBPs), general odorant binding proteins (GOBPs), and antennal binding proteins X (ABPXs), named according to their putative binding properties (OBPs reviewed in [32]). They are small soluble proteins (10–20 kDa) found in millimolar ranges in the sensillar lymph of mosquitoes [40], and mediate the first steps in the olfactory signal transduction cascade. They are proposed to be involved in several aspects of odorant perception, including odorant solubilization, transport and delivery to olfactory receptors as well as protection against degradation by odorant degrading enzymes (ODEs) [40]. In fact, a more active role of OBPs, where the OBP-odorant complex acts as an OR activating ligand, has recently been demonstrated for the Drosophila odorant binding protein LUSH in complex with the pheromone, 11-cis vaccenyl acetate (cVA) [41].

Most importantly, OBPs are expected to make a significant contribution to the remarkable selectivity of the olfactory system. OBPs have been found to bind specifically a limited number of candidate ligands [42–46]. However, given that the number of odorants that insects can detect is considerable higher than the number of OBPs, each OBP may specifically recognize a class of structurally related odorants, and also distinguish semiochemicals of different chemical structures [47–51].

On the other hand, the ORs also demonstrate broad spectrum diversity. Functional studies revealed that, while some receptors respond to single or a small set of aromatics, others exhibit substantial lower specificity [52–55].

Provided that neither OBPs nor ORs are extremely specific, the selective odor perception is likely to be achieved through interplay between compartmentalized OBPs and ORs, as if they constitute a two-step filter, with only one or very few common ligands [56]. Their synergistic function could be accomplished if they possess binding sites of similar 3D-shapes and physicochemical properties, thus making feasible the design of OR ligands based on the OBPs binding sites. It is possible that DEET and perhaps other repellents are transported to their specific receptors only via OBPs as has been shown for other odorants.

Structurally, the majority of the OBPs, termed classic OBPs, share a common fold with six α-helices connected by loops and interlinked by three disulfide bonds. Despite their structural homology, however, they are predicted to bear binding cavities of different shapes and hydrophobic environments that are capable of reversibly binding a wide range of organic molecules and naturally occurring odorants [57].

Of the 60 OBPs encoded in the genome of the African malaria vector Anopheles gambiae, several were shown to be expressed at a high level in female antennae [58]. Specifically, for one of them, AgamOBP1, previous experiments have shown that its mRNA is significantly more abundant in female relative to male antennae and also that its abundance is reduced after a blood meal suggestive of a possible involvement in host odor detection [58]. Indole, a known oviposition attractant, was subsequently shown to be a specific ligand for AgamOBP1; in fact, RNAi-mediated silencing experiments in conjunction with electrophysiological ones demonstrated that AgamOBP1 lies at the top of the signaling cascade triggered by this chemical and the associated physiological responses—when the levels of the protein are reduced drastically, the antennal responses to indole are severely impaired [59].

These findings identify OBPs, and AgamOBP1 in particular, as potential targets for the design of novel insect repellents or attractants.

In this work, we report on the first, high-resolution structure of a mosquito OBP, AgamOBP1, in complex with the synthetic repellent DEET bound at its binding site, and propose an OBP structure-based approach for the rational design of novel insect repellents that may interfere with mosquito olfactory function. Structural analysis of the AgamOBP1–DEET complex and molecular modeling calculations with known carboxamide derivatives of DEET and piperidines reveal that AgamOBP1 is a promising molecular target for structure-based design of more efficient insect repellents. Our results and conclusions are also correlated to those obtained recently from the analysis of the crystal structure of a Culex quinquefasciatus OBP, CquiOBP1, with a Culex attractant, the major oviposition pheromone, bound to it [60].

Materials and methods

Bacterial expression and purification of recombinant protein

AgamOBP1 cDNA (AF437884) [61], was PCR-amplified and subcloned into the NdeI/XhoI site of pET22b(+) expression vector (Novagen). For protein expression, E. coli Origami B(DE3) (Novagen) competent cells were transformed with pET22b(+)-AgamOBP1 and cultured at 37°C until OD600 was 0.5–0.6. Afterwards, 1 L of cell culture was induced with 1 mM IPTG (Sigma) and grown at 37°C for 4 h. Cells were disrupted by sonication in a lysis buffer containing 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF and a mixture of protease inhibitors (Roche). The cell lysate was clarified by ultracentrifugation at 130,000g for 30 min at 4°C. The cleared supernatant was first applied to a HiTrap Q FF column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0 (buffer A) and eluted with a 0–500 mM NaCl gradient. Fractions containing the target protein, as judged by SDS-PAGE analysis, were loaded onto a Resource-Q column (GE Healthcare) and eluted with a linear gradient of 0–300 mM NaCl. The major peak of the ion-exchange step, was subsequently loaded onto a Superdex75 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer A containing 200 mM NaCl, and the peak of protein eluted was further purified by two ion-exchange purification steps on a Resource-Q column with 0–250 and 0–300 mM NaCl, respectively [62]. Highly purified protein was desalted by dialysis and concentrated to 70 mg/ml in deionized water.

1-NPN binding competition assays

The affinity of the examined ligands for AgamOBP1 was measured indirectly by competitive binding assays, which determined the displacement of the ligands from AgamOBP1 by the fluorescent probe N-phenyl-1-naphthylamine (1-NPN). Purified recombinant AgamOBP1 was mixed with different concentrations of each ligand (in methanol) and 1-NPN (in methanol) in a final volume of 200 μL 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl (containing 1.5% methanol). The final concentration of AgamOBP1 and 1-NPN in the assays was 2 μM. DEET concentration ranged from 2.5 to 20 μM while the other ligands were tested at lower concentrations (0.156–5 μM). The probe was excited at 337 nm and emission spectra were recorded between 386 and 460 nm (peak emission in the presence of AgamOBP1 is at 402–406 nm). Emission spectra were recorded on an Infinite M-200 fluorimeter (Tecan Trading, Switzerland) using black 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-One).

Kd calculations

The dissociation constant of 1-NPN (K p) was determined by fluorescence measurements of protein solutions containing 2 μΜ AgamOBP1 and various concentrations of 1-NPN (1–10 μΜ). After subtraction of the background spectra (1-NPN in buffer), the residual fluorescence intensities were transformed to concentrations of bound 1-NPN ([1-NPN]bound) by the equation [1-NPN]i ,bound = (F i/F 0) × Cap, where F i is the fluorescence at a given 1-NPN concentration, F 0 is the corresponding fluorescence at 1-NPN saturation and “Cap” is the maximum binding capacity of AgamOBP1 at 1-NPN saturation. For this calculation, “Cap” was set equal to the total protein concentration (2 μM) assuming that [protein]:[1-NPN] stoichiometry at saturation was 1:1. The [1-NPN]bound plotted versus [1-NPN]free ([1-NPN]free = ([1-NPN]total − [1-NPN]bound) concentration yielded a curve from which a K p value of 4.5 ± 0.3 μM was calculated by non-linear regression (Supplement, Fig. 1).

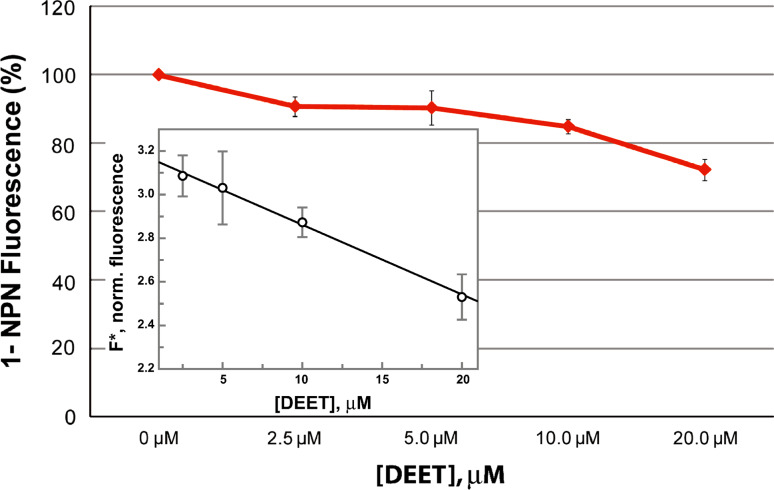

To determine the dissociation constant of DEET, the normalized fluorescence intensity F* was plotted as a function of DEET concentration (Fig. 1). By assuming mutually exclusive binding of 1-NPN and DEET to AgamOBP1 (see modeling studies), data were fitted to equation Eq. 1 [63]

|

1 |

where K L and K P are the dissociation constants of ligand (DEET) and probe (1-NPN), respectively, F* (relative fluorescence intensity/Q) is the normalized intensity, Q is a constant that depends on the sensitivity of fluorimeter and photophysical properties of free 1-NPN, γ (fluorescence enhancement) is the ratio of respective fluorescence intensities of bound and free 1-NPN. [E]T, [P]T and [L]T are the concentrations of protein, probe and DEET, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Ligand-concentration-dependent fluorescence quenching of AgamΟΒP1/1-NPN solutions. Fluorescence data obtained with 2 μΜ AgamOBP1 at constant concentration of 1-NPN (2 μM; [P]T) and various concentrations of DEET (2.5, 5, 10 and 20 μΜ; [L]T). The experiment was performed three times using duplicate wells. Inset replot of the normalized fluorescence F* (RFU/Q) versus various concentrations of DEET. A K L value of 31.3 μM for DEET can be calculated by Eq. 1 (see “Materials and methods”), assuming that DEET competes with 1-NPN for the same binding site. Normalization factor (Q) was 541.5 and fluorescent enhancement (γ) was 3.32. The dissociation constant for 1-NPN (K P) was 4.5 μΜ

The value of Q was determined by measuring the fluorescence intensity of 2 μΜ 1-NPN in pure buffer (F 1-NPNfree = [1-NPN]free × Q), whereas γ was determined by measurement of the corresponding fluorescence intensity in the presence of 2 μΜ AgamOBP1 (γ = F 1-NPNbound/F 1-NPNfree). The K d, was calculated by using a non-linear-regression data analysis program (GraFit) [64]. Similar calculations were employed for the estimation of K d values for the other chemical compounds which are under investigation in this report.

Crystallization and data collection

AgamOBP1 crystals were grown at 22°C using the hanging drop vapour diffusion technique with 35 mg/ml of protein in a buffer comprising 32% PEG 8000, 250 mM MgCl2 and 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0 [62] (Supplement, Fig. 2). For soaking experiments, preformed crystals were soaked in a solution containing 2.5 mM DEET, 0.5% methanol, 32% PEG 8000, 250 mM MgCl2 and 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0 for 5 h. Prior to data collection, crystals were transferred to fresh buffer containing 10% (v/v) glycerol as cryoprotectant and flash frozen in a nitrogen stream at 100 K. Diffraction data were collected from a single crystal on the X12 beamline at EMBL/Hamburg (λ = 0.81 Å) using a 225-mm MAR CCD detector. The crystal-to-image plate distance was 200 mm and gave a maximum resolution of 1.6 Å at the edge of the detector.

Structure determination

Integration and data reduction were performed with the programs MOSFLM [65] and SCALA of the CCP4 suite [66] and intensities were converted to amplitudes using TRUNCATE [67]. Phases were obtained with MOLREP [68] using the 2ERB structure [62] as molecular replacement model (R f/σ = 12.22, T f/σ = 27.25, Z score = 0.64).

Alternate cycles of manual building with the program COOT [69] and refinement using the maximum likelihood target function as implemented in the program REFMAC [70] improved the model phases. At this stage, water molecules were added to unidentified F o − F c map peaks >1.0σ by using the “water find” module of the program COOT. After an additional cycle of refinement and manual building, Mg2+, Cl− ions and methanol as well as DEET and PEG models were fitted into electron density and included in subsequent refinement cycles. DEET and PEG models were generated by PRODRG server [71]. The final model was generated by TLS refinement [72] within REFMAC using nine and eight TLS groups for chain A and B, respectively, to a final R factor of 0.172 (R free = 0.203). Details of data processing and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Statistics of data collection, processing and refinement of the AgamOBP1–DEET complex

| PDB ID | 3N7H |

|---|---|

| EMBL/DESY, HAMBURG X12; λ (Å) | 0.81 |

| Space group | P2 1 22 1 |

| Cell dimensions (Å), a, b, c α = β = γ = 90° | 55.9, 63.5, 68.1 |

| Resolution (Å) | 31.8–1.60 |

| Outermost shell (Å) | 1.68–1.60 |

| Reflections measured | 161,566 |

| Unique reflections (σ > 0) | 32,417 |

| R asymm | 0.080 (0.414) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.3 (98.2) |

| 〈I/σI〉 | 12.6 (3.5) |

| Redundancy | 5.0 (4.7) |

| Wilson Plot B value (Å2) | 21.5 |

| Final R bcryst (R cfree) % | 17.2 (20.3) |

| Error in coordinates by Luzzati plot (Å) | 0.17 |

| No. of water molecules in final cycle | 343 |

| r.m.s. Deviation from ideality | |

| In bond lengths (Å) | 0.009 |

| In bond angles (o) | 1.3 |

| Average B factor (Å2) | |

| Protein atoms (chain A; chain B) | 15.0; 14.1 |

| Water molecules | 27.5 |

| DEET (chain A; chain B) | 22.3; 24.9 |

| PEG (chain A; chain B) | 36.6; 42.4 |

| Ramachandran (u–w) plot | |

| Residues in most favored regions 91.4%, residues in allowed regions 8.6% | |

Values in parentheses are for the outermost shell

a R symm = ΣhΣi |I(h) − I i(h)/ΣhΣi I i(h) where I i(h) and I(h) are the ith and the mean measurements of the intensity of reflection h

b R cryst = Σh |F o − F |c/Σh F o, where F o and F c are the observed and calculated structure factors amplitudes of reflection h, respectively

c R free is equal to R cryst for a randomly selected 5% subset of reflections not used in the refinement

ROCHECK [73] was used to assess the quality of the final structure. Structural superimpositions were performed with the LSQKAB program [66]. Possible hydrogen bonds were calculated with HBPLUS [74]. Van der Waals (vdW) contacts were determined by CONTACTS of the CCP4 suite for non-hydrogen atoms separated by <4 Å. Solvent-accessible areas were calculated with NACCESS [75]. Plots of protein–ligand interactions and ligand accessibility were created with LIGPLOT [76]. Ligand-binding cavity visualized and analyzed with CAVER 2.0 [77]. Cavity volume was calculated with VOIDOO [78]. Shape complementarity between AgamOBP1 and DEET was calculated with SC [79]. All figures were created with PyMOL [80]. The coordinates of the protein complex have been deposited with the RCSB Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb) with code 3N7H.

Molecular docking

DEET and several carboxamides and piperidines were studied for their binding to AgamOBP1 using the molecular docking program AutoDock 4.0 [81]. The Lamarckian genetic algorithm (LGA) search method with default parameters (2,500,000 maximum number of energy evaluations, 27,000 maximum number of generations) was used and all ligands were treated as flexible. Docking results were both visually inspected and quantitatively evaluated based on the estimated free energy of binding (FEB), ligand efficiency (LE) and fit quality (FQ). The AutoDock empirical free energy model is able to predict binding free energies to within 2.5 kcal/mol. This is sufficient to distinguish ligands with inhibition constant in the range of millimolar, micromolar or nanomolar. Ligand efficiency can be defined as the ratio of the ligand affinity (ΔG, pK i, pIC50) divided by its molecular size. We used pK i as a measure of affinity and defined the molecular size as the number of heavy (non-hydrogen) atoms [82]. LE is a simple measure to assess the ‘goodness of fit’ of a ligand. However it is strongly dependent on molecular size and it cannot be used to compare ligands across wide size ranges. Thus, a size-independent efficiency score termed fit quality (FQ) was calculated as proposed in Bembenek et al. [83]. FQ is a scaled ligand efficiency that facilitates identification of ligands with near optimal binding (FQ scores near 1.0) and compounds of sub-optimal binding with low FQ scores.

Results and discussion

DEET-dependent 1-NPN displacement

To deduce whether the inhibition of mosquito olfactory function by DEET may also include, besides ORs, a component involving one or more OBPs, particularly AgamOBP1 whose crystallographic structure has been solved [62], we sought to examine the ability of DEET to interact with this OBP using as a measure DEET’s capacity to displace the fluorescent probe 1-NPN from AgamOBP1. This reporter system has been documented extensively for studying OBP–ligand interactions in vertebrates and insects [84–86]. Measurement of fluorescence quenching, at a constant concentration of 1-NPN (2 μM) and different concentrations of DEET, showed that DEET can displace 1-NPN from its binding site. In particular, titration with 20 μΜ DEET resulted in a ~30% reduction in the fluorescence obtained from the AgamOBP1-bound 1-NPN complex (Fig. 1). Analysis of the fluorescence data, as described in “Materials and Methods” and Fig. 1, gave a K d value of 31.3 ± 1.4 μM for DEET assuming competition with 1-NPN for the same binding site. In fact, modeling studies show that DEET and 1-NPN compete for the same binding pocket in AgamOBP1 and, although 1-NPN is located in the inner part and DEET towards the outer part of the binding pocket, coexistence in the binding pocket is most improbable (Supplement, Fig. 3).

Overview of structural features

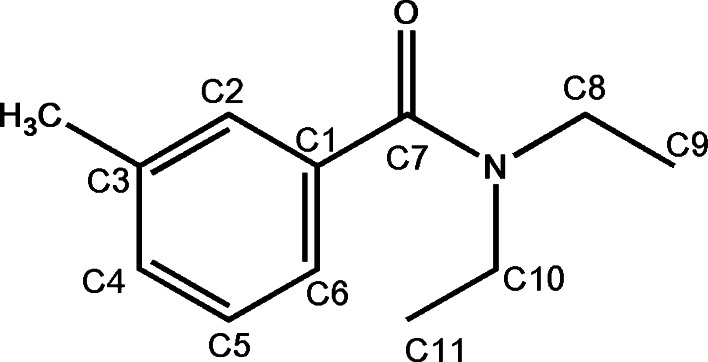

The structure of AgamOBP1 with PEG has previously been described [62]. In that structure, a PEG molecule, introduced from the crystallization condition, was found to occupy the whole length of a long tunnel, which is running through both subunits of a non-crystallographic dimer. In order to identify the presumed binding site of DEET on AgamOBP1 and its binding mode, we have determined the crystal structure of the AgamOBP1–DEET complex at 1.6 Å resolution (Table 1). The structural formula and numbering of DEET atoms are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The chemical structure of N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET) with the numbering used in the crystallographic study

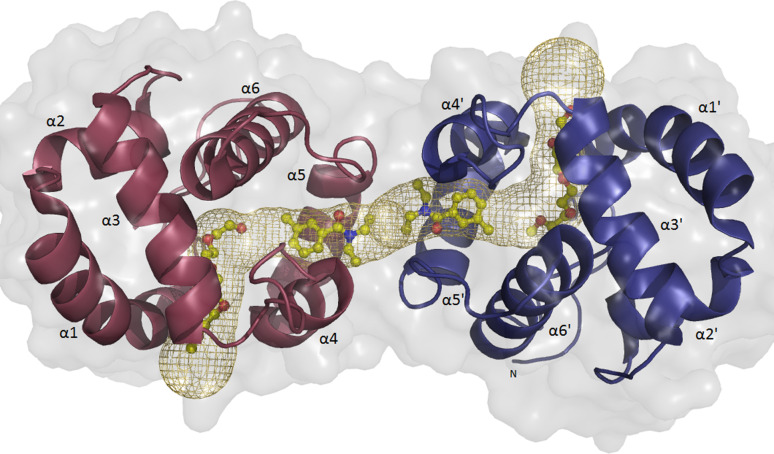

The crystal structure showed that one DEET molecule is bound to each subunit at a site located near the interface between the two monomers (Fig. 3). DEET binding results in the splitting of the continuous tunnel into two equal parts, each 28 Å long. In addition to a DEET molecule, the remaining area of each cavity is filled with a PEG molecule (5 ethylene glycol units), which is derived from the crystallization agent.

Fig. 3.

Cartoon representation of AgamOBP1 dimer with molecules of DEET and PEG bound. DEET’s binding site is located at the center of a long hydrophobic tunnel (represented as a mesh) running through the dimer interface. The tunnel is bordered by residues Leu15, Ala18, Leu19, Leu22 (from α1 helix), Ala62 (from α3/10 helix), Lys63 (residue in isolated beta-bridge), Leu73, Leu76, His77, Ser79, Leu80 (from α4 helix), Met84, Ala88, Met89 (from α5 helix), Leu96 (loop), His111, Trp114 (from α6 helix) and Phe123 from the C-terminal loop

The binding of DEET

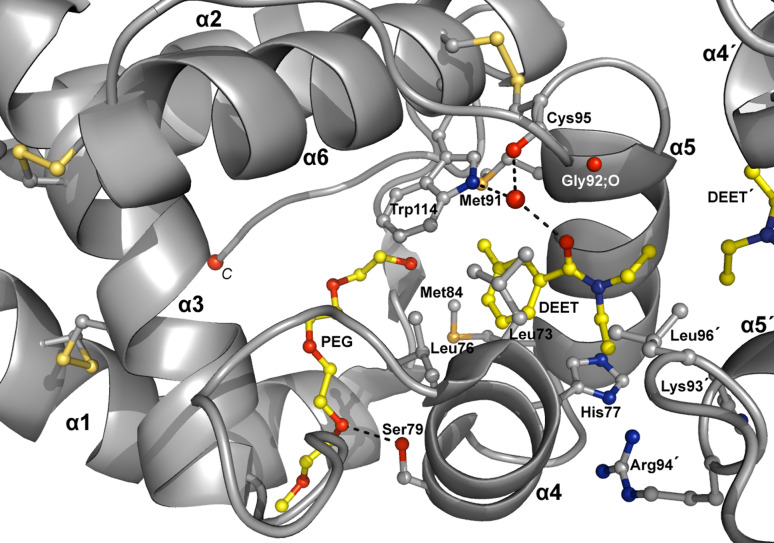

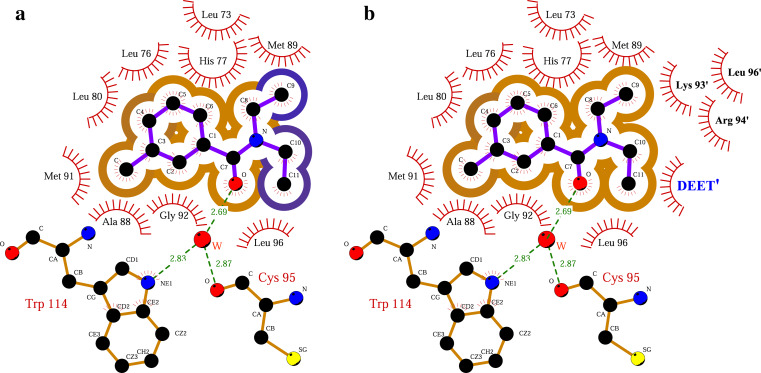

DEET’s binding pocket is formed by residues belonging to helices α4 (Leu73, Leu76, His77, Leu80), α5 (Ala88, Met89, Met91, Gly92), α6 (Trp114) and Leu96, Lys93′, Arg94′ and Leu96′, where the prime (′) refers to residues from the other molecule of the dimer (Fig. 4). DEET binds with high shape complementarity (shape correlation statistic Sc = 0.834) to this pocket and exploits numerous contacts. Upon binding, DEET makes 57 vdW interactions, mainly with non-polar protein atoms, and also one hydrogen bond from its carbonylic oxygen to a water molecule (distance 2.69 and 2.76 Å for A and B molecules, respectively), which, in turn, interacts with the NE1 nitrogen atom of the Trp114 ring and the carbonylic oxygen of Cys95 or Gly92, alternately (Fig. 4 and Table 2a). Three additional vdW interactions arise from non-polar contacts between the ethyl groups (C10, C11, C10′ and C11′) of the adjacent DEET molecules (Table 2b).

Fig. 4.

DEET and PEG (with carbon atoms coloured in yellow) form one hydrogen bond each with a water molecule and the side chain of Ser79, respectively. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed lines. The contacts between ligands and AgamOBP1 are dominated by non-polar vdW interactions. In particular, DEET makes vdW interactions with residues from α4, α5 helices and residues from the other monomer as well as with the neighboring DEET′ molecule. The three disulfide bonds are represented by bonds coloured in light orange

Table 2.

Hydrogen bonds (a) and van der Waals contacts (b) between DEET and AgamOBP1 residues

| (a) Potential hydrogen bonds | ||

|---|---|---|

| DEET atom of molecule A (B) | AgamOBP1 atom of molecule A (B) | Distance (Å) |

| O (O′) | Wat360a (Wat153 a) | 2.69 (2.76) |

| (b) van der Waals contactsb | ||

|---|---|---|

| DEET atom of molecule A | AgamOBP1 atom of molecule A (B) | Number of contacts |

| C1 | Wat360; Ala88 O | 2 |

| C2 | Ala88 C, O; Gly92 CA; Trp114 NE1; Wat360 | 5 |

| C3 | Ala88 O, CB; Trp114 CE2, CZ2 | 4 |

| C4 | Leu76 CD2, CG; Leu80 CD1; Ala88 CB | 4 |

| C5 | Leu73 O; Leu76 CB, CD2, CG; His77 CA, N, CB, CD2 | 8 |

| C6 | Leu73 O; His77 CB, CD2 | 3 |

| C | Ala88 O, CB; Met91 SD; Trp114 NE1,CD2, CE2, CZ2 | 7 |

| C7 | Gly92 CA; Wat360 | 2 |

| O | Leu73 CD1; Gly92 CA, C, O; Leu96 CD2 | 5 |

| C8 | His77 NE2, CD2, ND1, CB, CG; Met89 SD | 6 |

| C9 | Leu73 O; His77 CB, ND1, CG; (Lys93′ O; Arg94′ NH1; Leu96′ CD1) | 7 |

| C10 | Leu96 CD2; (DEET′ C11′) | 2 |

| C11 | Met89 O, CG; Leu96 CD2; (DEET′ C10′, C11′) | 5 |

| Total number of contacts | 60 |

Residues from chain B are indicated with a prime (′) and in bold type

aWat360 is in turn hydrogen bonded to Trp114 NE1 (2.83 Å), while it can donate an additional hydrogen to make a hydrogen bond either to Gly92 O (3.39 Å) or Cys95 O (2.87 Å). The corresponding distances are OW153–OGly92 = 3.25 Å and OW153–OCys95 = 2.85 Å

bVan der Waals interactions were assigned for non-hydrogen atoms separated by <4 Å

DEET binds in a conformation where the benzyl ring is inclined by 51.4° to its amide plane and 31.1° to the aromatic ring of Trp114 (Fig. 4). Upon binding to AgamOBP1 monomer, there is a total reduction of 310 Å2 in the protein’s solvent-accessible area and the greatest contribution comes from the non-polar groups which contribute 287 Å2 (92%) of this buried surface. Interestingly, on forming the complex with AgamOBP1, DEET becomes almost entirely buried. The solvent accessible surface area of the ligand is reduced from 388 Å2 in the free state to 38 Å2 in the bound state, resulting in a 90% decrease of the ligand’s accessible surface area. The non-polar atoms contribute 322 Å2 (92%) to the surface of DEET that becomes buried (Fig. 5a). In the dimer, the vdW interactions between the ethyl groups of the two DEET molecules lead to their total entrapment (99.9%) (Fig. 5b). In addition, upon binding of DEET molecules, the non-polar surface of the protein’s dimer interface is increased by 33.1 Å2 and the polar surface is reduced by 5 Å2 (1%).

Fig. 5.

LIGPLOT diagram of DEET a if bound to the monomer and b bound to the dimer. Hydrogen bonds are represented by green dashed lines and hydrophobic contacts by arcs with radiating spokes. The solvent accessibility is shown in brown or blue semi-circles for buried and highly accessible atoms, respectively. Corresponding atoms, involved in hydrophobic contacts, are represented by black circles

This analysis indicates that DEET binds more favorable in the dimeric form of AgamOBP1. Since it has been found that a monomer–dimer equilibrium exists in solution [60, 87] and considering the exceptionally high concentration of OBPs in the insect’s sensillum lymph (up to 10 mM; [88]), it is possible that the protein dimer is the molecular target of DEET under physiological conditions.

The binding of PEG

The PEG molecule is found to have entered the L-shaped tunnel of the AgamOBP1 binding site via its opening to the solvent which is delimited by helices α1, α3 and α4 and occupies the area from the entrance to the channel’s bend (Fig. 2). PEG forms 18 vdW contacts with protein atoms and one hydrogen bond to the side chain of Ser79 (distance 2.92 and 3.18 Å for A and B molecules, respectively) (Fig. 4; Supplement, Table 1). The solvent accessible surface of the bound PEG (48 Å2) is constituted by polar atoms and corresponds to 11% of the total accessible surface in the free state (435 Å2).

In its totality, the tertiary structure of AgamOBP1–DEET complex resembles the previously reported PEG-bound AgamOBP1 protein (2ERB). The overall root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the Cα and backbone atoms between AgamOBP1–DEET and 2ERB complexes is 0.209 and 0.254 Ǻ, respectively. Furthermore, no differences are observed in the positions of the amino acid side chains in the vicinity of DEET’s binding site.

Therefore, the structural data show that the AgamOBP1 binding site can accommodate ligands with diverged chemical structure (DEET and PEG) without undergoing significant conformational changes. The binding potency of DEET for AgamOBP1 appears to arise from the energetically favorable transfer of a hydrophobic molecule from the polar solvent to the hydrophobic environment of the binding site. In addition, DEET displays remarkable shape complementarity with the binding site of AgamOBP1. The ability of synthetic ligands to exhibit complementarily (an index of specificity) with physiological binding sites by inducing conformational changes is not uncommon. However, the AgamOBP1–DEET complex conforms better to “the lock and key” model. This structural information may prove to be a valuable tool in the design of novel repellents where enhanced potency and specificity are required.

Implications for structure-based design

In addition to numerous non-polar interactions and shape complementarity between the ligand and the protein, the unique hydrogen bond between the amide oxygen and a water molecule is proposed to play an important role in the ligand recognition process. The identification of such an ordered water molecule into the binding pocket could prove to be very useful tool for the design of novel compounds [89]. Multiple approaches could be pursued in order to achieve this objective. For instance, new ligands can be designed which maximize contacts with the water molecule [90]. Alternatively, the water molecule could be incorporated into the ligand’s structure leading to improved binding affinity by increasing both the number of direct protein–ligand interactions and the entropy due to the water’s displacement. Such an approach has already been proven successful for the rational design of novel HIV protease inhibitors [91]. In addition, the water molecule could be included into modeling or QSAR calculations to improve the accuracy and effectiveness of the prediction [92].

The shape of the binding pocket of DEET (Fig. 6a) suggests that larger aromatic systems (e.g., indole or naphthalene ring) may be accommodated and exploit π–π interactions with Trp114. Furthermore, attachment of aliphatic chains to the C3 and/or C4 carbon atoms of the benzene ring (meta- and/or para-substitution) could lead to novel derivatives that will utilize additional interactions with protein residues from both DEET’s and PEG’s binding sites.

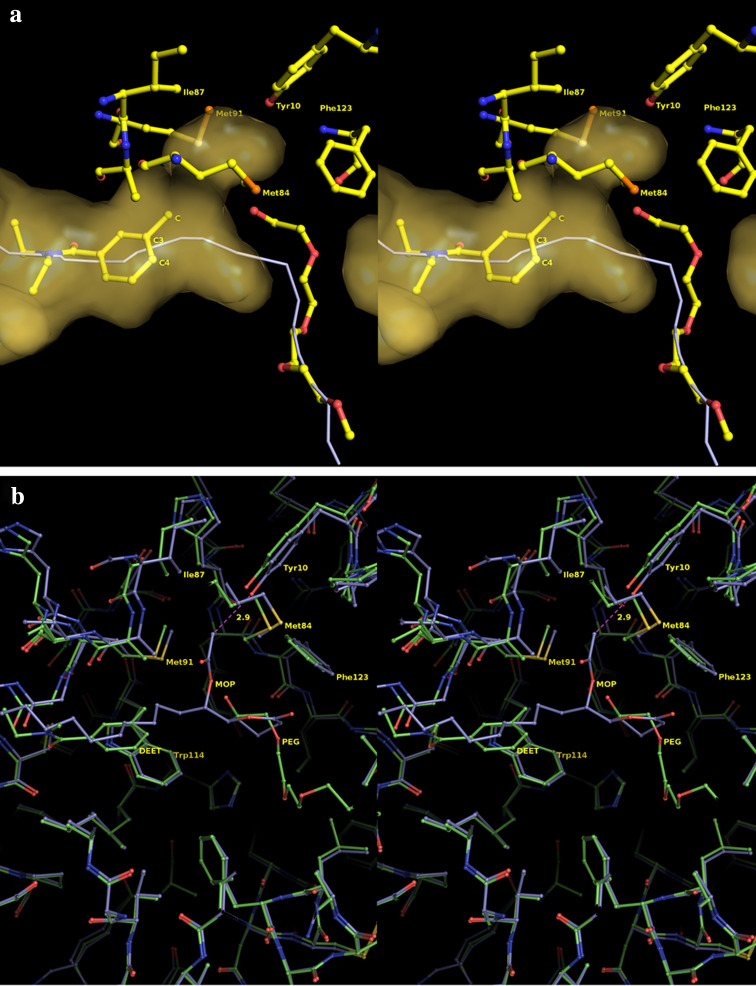

Fig. 6.

a Stereo diagram of the Connolly molecular surface (yellow) in the vicinity of DEET’s binding site. The corresponding path of the binding tunnel is represented as a white line. The existence of an empty pocket that diverges from the tunnel direction and emerges above the 3-methyl group of DEET is apparent. The shape of this cavity suggests that substitution at 3 (meta-) and 4 (para-) positions of the benzene ring could be exploited for the design of DEET analogues with improved affinity for AgamOBP1. b Stereo diagram illustrating the binding mode of DEET (green) and MOP (blue) at the binding site of AgamOBP1 and CquiOBP1 (PDB id 3OGN), respectively. The structural conservation of binding cavities is apparent. The overall root mean square deviation (RMSD) between Cα and backbone atoms of AgamOBP1–DEET and 3OGN are 0.306 and 0.308 Ǻ, respectively. MOP overlaps both with DEET and part of PEG molecule whereas its acetyl ester branch enters the extra pocket lined by residues Phe123, Ile87, Met91, Met84 and Tyr10

Importantly, the cavity analysis revealed the presence of a complementary pocket extending from the 3-methyl group of DEET towards Tyr10. This extra pocket is surrounded on either side by the side chains of Met84, Met91, Ile87 and Phe123, whereas the side chain of Tyr10 constitutes the polar bottom of the pocket with its hydroxyl moiety oriented opposite to the 3-methyl group (Fig. 6a). The shape and the nature of this side-pocket suggest that substitution of the 3-methyl group by groups bearing polar moieties might lead to DEET derivatives with enhanced affinity for AgamOBP1. Furthermore, the plane of the phenyl ring of Phe123 lies perpendicular to the plane of the aromatic ring of Tyr10 (91.3° for the A and 89.3° for the B chain of the dimer).

The occupancy of this side-pocket cavity by a polar group could lead to formation of favorable hydrogen bond to the hydroxyl group of Tyr10. Alternatively, the occupation of this side-pocket cavity by an aromatic substitute could induce the rotation of the Phe123 ring by 90° into a parallel position leading to the optimization of interactions with the ligand (two-ring stacking interactions).

Moreover, a DEET derivative comprising a long side aliphatic chain, which is extended towards the position of PEG and contains an aromatic system attached to its edge, is likely to develop additional π–π stacking interactions with the aromatic ring of Phe123 and, thus, display enhanced binding capacity.

Recently, the 3D structure of an odorant protein from Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito (CquiOBP1) in complex with the major oviposition pheromone (5R,6S)-6-acetoxy-5-hexadecanolide (MOP) has been determined [60]. AgamOBP1 exhibits 90% sequence identity with CquiOBP1, and the amino acids that define the ligand/pheromone binding site are well conserved between the two proteins. Superimposition of the AgamOBP1–DEET and CquiOBP1–MOP complex structures revealed that DEET and MOP are bound in the same hydrophobic tunnel (Fig. 6b). MOP comprises a long lipid chain, which is localized in the same position where DEET is bound, and a lactone ring, which lies opposite to Phe123 and occupies part of PEG’s binding site.

Significantly, MOP’s acetyl ester branch enters the complementary pocket and is located in hydrogen bond distance (2.95 Å) from Tyr10 proving the great importance of this extra cavity in the designing of ligands.

The structural comparison between AgamOBP1–DEET and the PEG-free CquiOBP1–MOP structures revealed that PEG did not perturb the structure of the PEG’s binding sub-cavity. Since the crystal structure of unliganded OBP1 lacks, it is difficult to conclude the effect of PEG within the cavity. However, the ability of 2.5 mM DEET or ~3.5 mM MOP to displace PEG, present in the crystallization medium at a concentration of 40 mM (32% PEG 8 K w/v) or 50 mM (20% PEG 4 K w/v), respectively, indicates the loose binding between PEG and OBP1.

The exploitation of this structural information for the design of new potent repellents and/or attractants remains to be realized.

Modeling of structurally related repellents

In a first approach to assess whether the above predictions could serve as the basis for structure-based modeling of compounds with similar structures for binding to AgamOBP1, a test set of 29 carboxamides and piperidine derivatives were studied by docking simulation. These derivatives have been characterized as physiologically relevant lead compounds with repellent properties [24, 26, 27]. To evaluate the accuracy of our methodology, DEET and 1-NPN were used as bench-mark molecules. The re-docked complex of AgamOBP1 with DEET is in good agreement with the experimentally solved one (Supplment, Fig. 4). In the case of the non-hydrated binding site, DEET moved slightly towards Trp114 to directly form a hydrogen bond with the NE1 nitrogen atom of the Trp114 imidazole.

These findings indicate that docking simulations could be used to investigate whether AgamOBP1 (and, perhaps, other structurally related OBPs as well) is a potential molecular target for novel insect repellents.

The test dataset included ten piperidine derivatives (Table 3; a/a 1–10) proposed by Katritzky et al. [27] with structural features essential for repellency of Aedes aegypti; and two carboxamides (Table 3; a/a 11, 12) with improved duration of repellency and minimum effective dosage (MED), also suggested by Katritzky et al. [26]. Additionally, we have investigated 12 carboxamides proposed by Gaudin et al. [24]. Six of them have very promising olfactory profiles (Table 3; a/a 13–18), four share improved repellency properties against three breeds of cockroach (Table 3; a/a 19–22) and two combine both characteristics (Table 3, a/a 23, 24). The remaining five ligands (Table 3; a/a 25–29) are simple or naturally occurring carboxamides known to be active against insects [24].

Table 3.

Predicted binding characteristics of potential insect repellents for AgamOBP1

| a/a | ligand | HA | FEB (kcal/mol) | K i (μM) | LE | FQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEET | 14 | −5.86 | 50.51 | 0.31 | 0.50 | |

| 1-NPN | 17 | −7.55 | 2.92 | 0.33 | 0.61 | |

| 1 | 1-(3-Cyclohexyl-1-oxopropyl)-2-ethylpiperidine | 18 | −8.19 | 0.99 | 0.33 | 0.66 |

| 2 | 1-(3-Cyclohexyl-1-oxopropyl)-2-methylpiperidine | 17 | −8.06 | 1.24 | 0.3 | 0.66 |

| 3 | 2-Ethyl-1-(1-oxo-10-undecylenyl)piperidine | 20 | −7.81 | 1.90 | 0.29 | 0.61 |

| 4 | 4-Methyl-1-(1-oxo-10-undecylenyl)piperidine | 19 | −7.64 | 2.50 | 0.29 | 0.61 |

| 5 | 4-Methyl-1-(1-oxodecyl)piperidine | 18 | −7.54 | 2.99 | 0.31 | 0.60 |

| 6 | 2-Methyl-1-(1-oxodecyl)piperidine | 18 | −7.36 | 4.04 | 0.30 | 0.59 |

| 7 | 1-(1-Oxo-10-undecylenyl)piperidine | 18 | −7.26 | 4.79 | 0.30 | 0.58 |

| 8 | 1-(1-Oxoundecyl)piperidine | 18 | −7.20 | 5.28 | 0.29 | 0.58 |

| 9 | 2-Ethyl-1-(1-oxononyl)piperidine | 18 | −7.12 | 6.05 | 0.29 | 0.57 |

| 10 | 4-Methyl-1-(1-oxooctyl)piperidine | 16 | −6.88 | 9.05 | 0.32 | 0.57 |

| 11 | (E)-N-cyclohexyl-N-ethyl-2-hexenamide | 16 | −7.34 | 4.18 | 0.34 | 0.61 |

| 12 | Hexahydro-1-(1-oxohexyl)-1H-azepine | 14 | −6.49 | 17.59 | 0.34 | 0.56 |

| 13 | N-Cyclohexyl-N,3,3-trimethylbutanamide | 15 | −6.79 | 10.50 | 0.33 | 0.57 |

| 14 | 2-Ethyl-N-methyl-N-phenylbutanamide | 15 | −6.57 | 15.40 | 0.32 | 0.55 |

| 15 | N-Cyclohexyl-N,2,2-trimethylpropanamide | 14 | −5.91 | 46.31 | 0.31 | 0.51 |

| 16 | N,N,2-Triethylhexanamide | 14 | −5.51 | 92.18 | 0.29 | 0.47 |

| 17 | (+/−)-2-Ethyl-N,N-diisopropylhexanamide | 16 | −5.37 | 114.99 | 0.25 | 0.44 |

| 18 | N,N,2-Triethylbutanamide | 12 | −4.77 | 320.17 | 0.29 | 0.44 |

| 19 | 1-(Cyclohexylcarbonyl)pyrrolidine | 13 | −6.41 | 19.90 | 0.36 | 0.57 |

| 20 | N,N-Diethylcyclohexanecarboxamide | 13 | −6.22 | 27.37 | 0.35 | 0.55 |

| 21 | N,N-Diethyl-3-phenylpropanamide | 15 | −6.49 | 17.51 | 0.32 | 0.55 |

| 22 | 1-(3,3-Dimethylbutanoyl)pyrrolidine | 12 | −5.54 | 87.18 | 0.34 | 0.51 |

| 23 | 2-Ethyl-N-isopropyl-N-methylbutanamide | 12 | −5.55 | 86.06 | 0.34 | 0.51 |

| 24 | N,N-Diallyl-2-ethylbutanamide | 14 | −5.58 | 80.64 | 0.29 | 0.48 |

| 25 | Piperine | 21 | −8.64 | 0.46 | 0.30 | 0.67 |

| 26 | Capsaicin | 22 | −7.77 | 2.00 | 0.26 | 0.60 |

| 27 | #15_Gaudin et al., 2008 | 29 | −7.97 | 1.43 | 0.20 | 0.58 |

| 28 | Pelitorine | 16 | −6.77 | 10.84 | 0.31 | 0.56 |

| 29 | Insect repellent 790 (Merck) | 14 | −5.47 | 98.31 | 0.29 | 0.47 |

HA Number of heavy atoms, FEB free energy of binding, K i inhibition constant, LE ligand efficiency, FQ fit quality

To investigate the ability of the examined ligands to bind on AgamOBP1, we used AutoDock to calculate the FEB, K i, LE and FQ values of DEET and 1-ΝPΝ conformations in the AgamOBP1 binding site. The corresponding values were −5.9 kcal/mol, 50.5 μM, 0.3 and 0.5 for DEET and −7.6 kcal.mol, 2.9 μM, 0.3 and 0.6 for 1-NPN, respectively.

The estimated FEB, LE and FQ of the docking simulations for the specific dataset are summarized in Table 3. Characteristic cases of the piperidine derivatives, which have comparable or better FEB and FQ values than DEET are 1-(3-Cyclohexyl-1-oxopropyl)-2-ethylpiperidine, 4-methyl-1-(1-oxodecyl)piperidine and 1-(1-oxo-10-undecylenyl)piperidine (a/a’s 1, 5 and 7, respectively). Similarly, typical examples from the dataset of carboxamides are hexahydro-1-(1-oxohexyl)-1H-azepine, 2-ethyl-N-methyl-N-phenylbutanamide, N,N-diethylcyclohexanecarboxamide, and piperine (a/as 12, 14, 20 and 25, respectively). The predicted binding of these ligands to AgamOBP1, which occurs in the same region of the AgamOBP1 cavity as DEET, is shown in Supplment, Fig. 5.

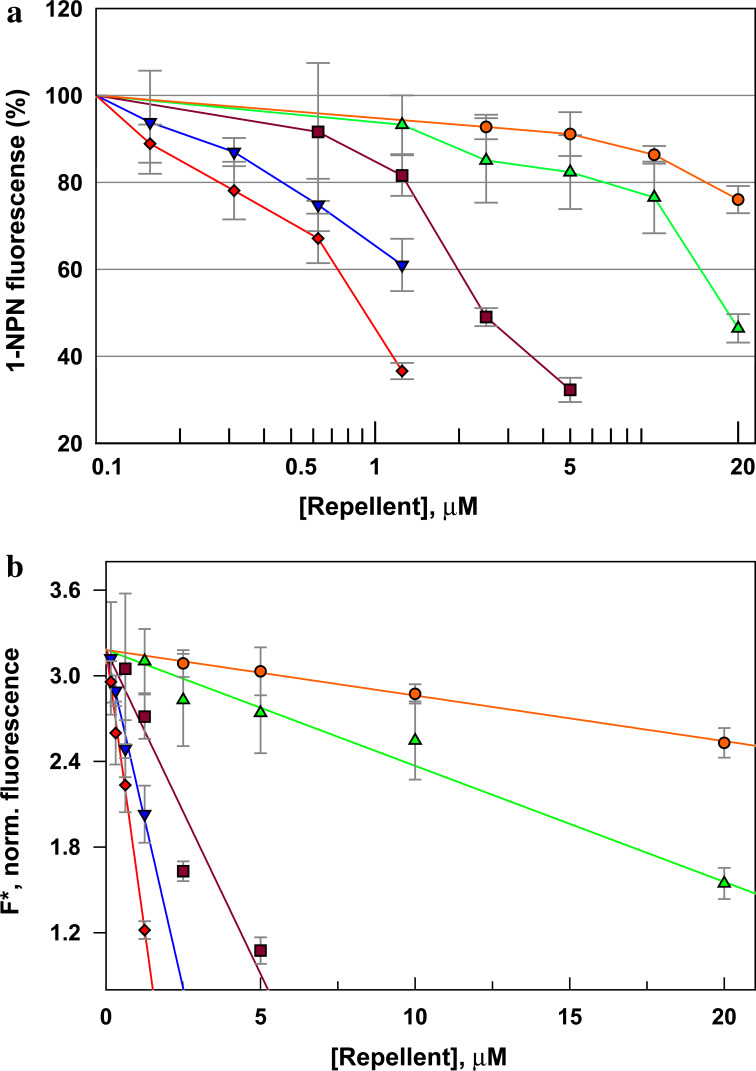

To test the validity of the modeling predictions, four of the test compounds, 1-(3-cyclohexyl-1-oxopropyl)-2-ethylpiperidine, 4-methyl-1-(1-oxodecyl)piperidine, piperine and capsaicin (a/as 1, 5, 25 and 26, respectively, in Table 3; Fig. 7), were examined experimentally for their ability to compete out the binding of 1-NPN to AgamOBP1. The results of the binding experiments showed very clearly the increased capacity of these ligands to displace 1-NPN from the AgamOBP1 cavity at much lower concentrations (nM range) compared to DEET (Fig. 8). The analysis of the fluorescence data for the four ligands revealed K d values significantly lower than the one obtained with DEET. Specifically, 4-methyl-1-(1-oxodecyl)-piperidine was the best ligand with a K d of 1.3 μM while piperine and 1-(3-cyclohexyl-1-oxopropyl)-2-ethylpiperidine gave K d values of 2.1 and 2.4 μM, respectively. The affinity of capsaicin for AgamOBP1 was sixfold lower than the other ligands (13.0 μM) but still 2.5-fold higher than DEET. The fairly good correlation coefficient between the experimental Κ d and the Autodock predicted Κ i values (R 2 = 0.867) indicates that docking simulations can facilitate the study for novel candidate ligands (Supplement, Fig. 6).

Fig. 7.

Representation of the AgamOBP1 binding pocket with DEET and PEG (yellow) superimposed with selected insect repellents. Molecular docking calculations were performed for 1-(3-cyclohexyl-1-oxopropyl)-2-ethylpiperidine (raspberry), 4-methyl-1-(1-oxodecyl)piperidine (red), piperine (blue) and capsaicin (green). These studies predicted that the binding affinities (K i) of these compounds are in the 0.5–3.0 μΜ range, indicating that carboxamide and piperidine repellents may possibly affect insects’ olfaction by interfering with AgamOBP1

Fig. 8.

Comparative fluorescence quenching of AgamOBP1/1-NPN solutions titrated with various concentrations of selected repellents. a Fluorescence data of 1.25–20 μM capsaicin (green triangle), 0.625–5 μM 1-(3-cyclohexyl-1-oxopropyl)-2-ethylpiperidine (raspberry square), 0.156–1.25 μΜ piperine (blue inverted triangle) and 0.156–1.25 μM 4-methyl-1-(1-oxodecyl)piperidine (red diamond), as compared with 2.5–20 μΜ DEET (orange circle). b Fluorescence data were treated as has been described for DEET (K d = 31.3 ± 1.4 μM) and the obtained K ds were 13.0 ± 1.4, 2.4 ± 0.5, 2.1 ± 0.1 and 1.3 ± 0.02 μM, respectively

Conclusions

Previous efforts to identify more efficient insect repellents were hindered by the absence of a known molecular target and were thus limited to only ligand-based computational approaches. The AgamOBP1–DEET structure provides the first example of a repellent recognized by an odorant binding protein and should give a significant impetus to structure-based design of novel repellents. With more than 50 OBP-encoding genes identified so far, the list of potential molecular targets for OBP-based design of novel repellents/attractants is expected to increase substantially in the very near future. Therefore, structure-based ligand design can provide promising leads with improved binding characteristics and specificity that could be further evaluated for ORs activation. This rational approach can dramatically shorten the number of ligands to be tested in subsequent behavioral or field studies providing thus a powerful tool for acceleration of novel repellents discovery.

We are currently pursuing crystallographic analyses of additional OBPs in conjunction with in silico ligand binding and design aimed at the identification of novel molecular targets and potential repellents.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the late Dr. Harald Biessmann and Dr. Marika F. Walter (Developmental Biology Center, University of California), for kindly providing the AgamOBP1 gene. This work was supported by funding provided by the European Commission for the FP7- HEALTH-2007-2.3.2.9 project “ENAROMaTIC” (GA-222927), the FP7-REGPOT-2008-1 project “EUROSTRUCT” (GA-230146) and the FP7-REGPOT-2009-1 Project “ARCADE” (GA-245866). Work at the Synchrotron Radiation Sources, MAX-lab, Lund, Sweden and EMBL Hamburg Outstation, Germany, was supported by funding provided by the European Commission for the FP7 Research Infrastructure Action “ELISA” (European Light Sources Activities).

Abbreviations

- AgamOBP1

Odorant binding protein 1 from Anopheles gambiae

- OR

Odorant receptor

- ON

Olfactory neuron

- DEET

N,N-Diethyl-m-toluamide

- 1-NPN

N-Phenyl-1-naphthylamine

- IPTG

Isopropyl-galacto-pyranoside

- MOP

(5R,6S)-6-Acetoxy-5-hexadecanolide

- TLS

Translation/libration/screw

- vdW

van der Waals

References

- 1.World Health Organization (2010) Malaria fact sheet N. 94. WHO website (online). http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs094/en/

- 2.Kar S, Kar S. Control of malaria. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9(7):511–512. doi: 10.1038/nrd3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gershon D. Malaria research tools up for the future. Nature. 2002;419(6906):4–5. doi: 10.1038/nj6906-04a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ito J, Ghosh A, Moreira LA, Wimmer EA, Jacobs-Lorena M. Transgenic anopheline mosquitoes impaired in transmission of a malaria parasite. Nature. 2002;417(6887):452–455. doi: 10.1038/417452a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim W, Koo H, Richman AM, Seeley D, Vizioli J, Klocko AD, O’Brochta DA. Ectopic expression of a cecropin transgene in the human malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae): effects on susceptibility to Plasmodium. J Med Entomol. 2004;41(3):447–455. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eskenazi B, Chevrier J, Rosas LG, Anderson HA, Bornman MS, Bouwman H, Chen AM, Cohn BA, de Jager C, Henshel DS, Leipzig F, Leipzig JS, Lorenz EC, Snedeker SM, Stapleton D. The Pine river statement: human health consequences of DDT use. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(9):1359–1367. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van den Berg H. Global status of DDT and its alternatives for use in vector control to prevent disease. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(11):1656–1663. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ranson H, Abdallah H, Badolo A, Guelbeogo WM, Kerah-Hinzoumbe C, Yangalbe-Kalnone E, Sagnon N, Simard F, Coetzee M. Insecticide resistance in Anopheles gambiae: data from the first year of a multi-country study highlight the extent of the problem. Malaria J. 2009;8:299. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore SJ, Debboun M (2007). In: Debboun M, Frances SP, Strickman D (eds) Insect repellents: principles, methods, and uses. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 3–30

- 10.Mccabe ET, Barthel WF, Gertler SI, Hall SA. Insect repellents. 3. N,N-diethylamides. J Org Chem. 1954;19(4):493–498. doi: 10.1021/jo01369a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frances SP, Cooper RD, Popat S, Beebe NW. Field evaluation of repellents containing DEET and AI3-37220 against Anopheles koliensis in Papua New Guinea. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2001;17(1):42–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xue RD, Ali A, Barnard DR. Laboratory evaluation of toxicity of 16 insect repellents in aerosol sprays to adult mosquitoes. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2003;19(3):271–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bohbot JD, Dickens JC. Insect repellents: modulators of mosquito odorant receptor activity. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(8):e12138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dogan EB, Ayres JW, Rossignol PA. Behavioural mode of action of DEET: inhibition of lactic acid attraction. Med Vet Entomol. 1999;13(1):97–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.1999.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ditzen M, Pellegrino M, Vosshall LB. Insect odorant receptors are molecular targets of the insect repellent DEET. Science. 2008;319(5871):1838–1842. doi: 10.1126/science.1153121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Syed Z, Leal WS. Mosquitoes smell and avoid the insect repellent DEET. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(36):13598–13603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805312105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robbins PJ, Cherniack MG. Review of the biodistribution and toxicity of the insect repellent N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET) J Toxicol Environ Health. 1986;18(4):503–525. doi: 10.1080/15287398609530891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corbel V, Stankiewicz M, Pennetier C, Fournier D, Stojan J, Girard E, Dimitrov M, Molgo J, Hougard JM, Lapied B (2009) Evidence for inhibition of cholinesterases in insect and mammalian nervous systems by the insect repellent DEET. BMC Biol 7:47. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-7-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Rutledge LC, Moussa MA, Lowe CA, Sofield RK. Comparative sensitivity of mosquito species and strains to repellent diethyl toluamide. J Med Entomol. 1978;14(5):536–541. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/14.5.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boeckh J, Breer H, Geier M, Hoever FP, Kruger BW, Nentwig G, Sass H. Acylated 1, 3-aminopropanols as repellents against bloodsucking arthropods. Pest Sci. 1996;48(4):359–373. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9063(199612)48:4<359::AID-PS490>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boeckh J, Hoever FP, Kruger BW, Nentwig G, Roder K (1996) N-acylated 2-(2-hydroxyethyl)-piperidines—a new class of insect and tick repellents. Abstr Pap Am Chem Soc 212:20 (Agro)

- 22.Astroff AB, Freshwater KJ, Young AD, Stuart BP, Sangha GK, Thyssen JH. The conduct of a two-generation reproductive toxicity study via dermal exposure in the Sprague-Dawley rat—a case study with KBR 3023 (a prospective insect repellent) Reprod Toxicol. 1999;13(3):223–232. doi: 10.1016/S0890-6238(99)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Natarajan R, Basak SC, Balaban AT, Klun JA, Schmidt WF. Chirality index, molecular overlay and biological activity of diastereoisomeric mosquito repellents. Pest Manag Sci. 2005;61(12):1193–1201. doi: 10.1002/ps.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaudin JM, Lander T, Nikolaenko O. Carboxamides combining favorable olfactory properties with insect repellency. Chem Biodivers. 2008;5(4):617–635. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200890058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pridgeon JW, Becnel JJ, Bernier UR, Clark GG, Linthicum KJ. Structure-activity relationships of 33 carboxamides as toxicants against female Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) J Med Entomol. 2010;47(2):172–178. doi: 10.1603/ME08265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katritzky AR, Wang ZQ, Slavon S, Dobchev DA, Hall CD, Tsikolia M, Bernier UR, Elejalde NM, Clark GG, Linthicum KJ. Novel carboxamides as potential mosquito repellents. J Med Entomol. 2010;47(5):924–938. doi: 10.1603/ME09284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katritzky AR, Wang ZQ, Slavov S, Tsikolia M, Dobchev D, Akhmedov NG, Hall CD, Bernier UR, Clark GG, Linthicum KJ. Synthesis and bioassay of improved mosquito repellents predicted from chemical structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(21):7359–7364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800571105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams MD, Celniker SE, Holt RA, et al. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster . Science. 2000;287(5461):2185–2195. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holt RA, Subramanian GM, Halpern A, et al. The genome sequence of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae . Science. 2002;298(5591):129–149. doi: 10.1126/science.1076181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato K, Pellegrino M, Nakagawa T, Nakagawa T, Vosshall LB, Touhara K. Insect olfactory receptors are heteromeric ligand-gated ion channels. Nature. 2008;452(7190):U1002–U1006. doi: 10.1038/nature06850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larsson MC, Domingos AI, Jones WD, Chiappe ME, Amrein H, Vosshall LB. Or83b encodes a broadly expressed odorant receptor essential for Drosophila olfaction. Neuron. 2004;43(5):703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou JJ. Odorant-binding proteins in insects. Vitam Horm Pheromones. 2010;83:241–272. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(10)83010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogers ME, Krieger J, Vogt RG. Antennal SNMPs (sensor neuron membrane proteins) of lepidoptera define a unique family of invertebrate CD36-like proteins. J Neurobiol. 2001;49(1):47–61. doi: 10.1002/neu.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benton R, Vannice KS, Vosshall LB. An essential role for a CD36-related receptor in pheromone detection in Drosophila . Nature. 2007;450(7167):289–293. doi: 10.1038/nature06328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Merrill CE, Riesgo-Escovar J, Pitts RJ, Kafatos FC, Carlson JR, Zwiebel LJ. Visual arrestins in olfactory pathways of Drosophila and the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(3):1633–1638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022505499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vogt RG, Riddiford LM, Prestwich GD. Kinetic-properties of a sex pheromone-degrading enzyme—the sensillar esterase of Antheraea polyphemus . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82(24):8827–8831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishida Y, Leal WS (2002) Cloning of putative odorant-degrading enzyme and integumental esterase cDNAs from the wild silkmoth, Antheraea polyphemus. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 32(12):1775–1780. doi:10.1016/S0965-1748(02)00136-4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Rybczynski R, Reagan J, Lerner MR. A pheromone-degrading aldehyde oxidase in the antennae of the moth Manduca sexta . J Neurosci. 1989;9(4):1341–1353. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-04-01341.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rogers ME, Jani MK, Vogt RG. An olfactory-specific glutathione-S-transferase in the sphinx moth Manduca sexta . J Exp Biol. 1999;202(Pt 12):1625–1637. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.12.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pelosi P. Perireceptor events in olfaction. J Neurobiol. 1996;30(1):3–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(199605)30:1<3::AID-NEU2>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laughlin JD, Ha TS, Jones DN, Smith DP. Activation of pheromone-sensitive neurons is mediated by conformational activation of pheromone-binding protein. Cell. 2008;133(7):1255–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Du GH, Prestwich GD. Protein-structure encodes the ligand-binding specificity in pheromone binding-proteins. Biochemistry. 1995;34(27):8726–8732. doi: 10.1021/bi00027a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MaÏbÈche-Coisne M, Sobrio F, Delaunay T, Lettere M, Dubroca J, Jacquin-Joly E, Nagnan-Le Meillour P. Pheromone binding proteins of the moth Mamestra brassicae: specificity of ligand binding. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;27(3):213–221. doi: 10.1016/S0965-1748(96)00088-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maida R, Krieger J, Gebauer T, Lange U, Ziegelberger G. Three pheromone-binding proteins in olfactory sensilla of the two silkmoth species Antheraea polyphemus and Antheraea pernyi . Eur J Biochem. 2000;267(10):2899–2908. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Plettner E, Lazar J, Prestwich EG, Prestwich GD. Discrimination of pheromone enantiomers by two pheromone binding proteins from the gypsy moth Lymantria dispar . Biochemistry. 2000;39(30):8953–8962. doi: 10.1021/bi000461x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wojtasek H, Leal WS. Conformational change in the pheromone-binding protein from Bombyx mori induced by pH and by interaction with membranes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(43):30950–30956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leal WS, Chen AM, Erickson ML. Selective and pH-dependent binding of a moth pheromone to a pheromone-binding protein. J Chem Ecol. 2005;31(10):2493–2499. doi: 10.1007/s10886-005-7458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tumlinson JH, Klein MG, Doolittle RE, Ladd TL, Proveaux AT. Identification of female Japanese beetle sex-pheromone—inhibition of male response by an enantiomer. Science. 1977;197(4305):789–792. doi: 10.1126/science.197.4305.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leal WS, Zarbin PHG, Wojtasek H, Kuwahara S, Hasegawa M, Ueda Y. Medicinal alkaloid as a sex pheromone. Nature. 1997;385(6613):213. doi: 10.1038/385213a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leal WS. Chemical communication in scarab beetles: reciprocal behavioral agonist-antagonist activities of chiral pheromones. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(22):12112–12115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leal WS. (R,Z)-5-(−)-(oct-1-enyl)Oxacyclopentan-2-one, the sex-pheromone of the scarab beetle Anomala cuprea . Naturwissenschaften. 1991;78(11):521–523. doi: 10.1007/BF01131404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wetzel CH, Behrendt HJ, Gisselmann G, Stortkuhl KF, Hovemann B, Hatt H. Functional expression and characterization of a Drosophila odorant receptor in a heterologous cell system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(16):9377–9380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151103998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hallem EA, Fox AN, Zwiebel LJ, Carlson JR. Olfaction—mosquito receptor for human-sweat odorant. Nature. 2004;427(6971):212–213. doi: 10.1038/427212a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carey AF, Wang GR, Su CY, Zwiebel LJ, Carlson JR. Odorant reception in the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae . Nature. 2010;464(7285):U66–U71. doi: 10.1038/nature08834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang GR, Carey AF, Carlson JR, Zwiebel LJ. Molecular basis of odor coding in the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(9):4418–4423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913392107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leal WS. Pheromone reception. Top Curr Chem. 2005;240:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tegoni M, Campanacci V, Cambillau C. Structural aspects of sexual attraction and chemical communication in insects. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29(5):257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Biessmann H, Nguyen QK, Le D, Walter MF. Microarray-based survey of a subset of putative olfactory genes in the mosquito Anopheles gambiae . Insect Mol Biol. 2005;14(6):575–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2005.00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Biessmann H, Andronopoulou E, Biessmann MR, Douris V, Dimitratos SD, Eliopoulos E, Guerin PM, Iatrou K, Justice RW, Krober T, Marinotti O, Tsitoura P, Woods DF, Walter MF. The Anopheles gambiae odorant binding protein 1 (AgamOBP1) mediates indole recognition in the antennae of female mosquitoes. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(3):e9471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mao Y, Xu XZ, Xu W, Ishida Y, Leal WS, Ames JB, Clardy J. Crystal and solution structures of an odorant-binding protein from the southern house mosquito complexed with an oviposition pheromone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(44):19102–19107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012274107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Biessmann H, Walter MF, Dimitratos S, Woods D. Isolation of cDNA clones encoding putative odourant binding proteins from the antennae of the malaria-transmitting mosquito, Anopheles gambiae . Insect Mol Biol. 2002;11(2):123–132. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2002.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wogulis M, Morgan T, Ishida Y, Leal WS, Wilson DK. The crystal structure of an odorant binding protein from Anopheles gambiae: evidence for a common ligand release mechanism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;339(1):157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kubala M, Plasek J, Amler E. Fluorescence competition assay for the assessment of ATP binding to an isolated domain of Na+, K+-ATPase. Physiol Res. 2004;53(1):109–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leatherbarrow RJ. GrafFit version 6.0. Staines: Erithakus Software; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leslie AGW (1992) Recent changes to the MOSFLM package for processing film and image plate data. Jnt CCP4/ESF-EACBM Newsl Protein Crystallogr No. 26

- 66.Collaborative Computational Project N The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50(Pt 5):760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.French S, Wilson K. Treatment of Negative Intensity Observations. Acta Crystallogr Sect A. 1978;34:517–525. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J Appl Crystallogr. 1997;30:1022–1025. doi: 10.1107/S0021889897006766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schuttelkopf AW, van Aalten DM. PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein–ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(Pt 8):1355–1363. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904011679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Painter J, Merritt EA. TLSMD web server for the generation of multi-group TLS models. J Appl Crystallogr. 2006;39:109–111. doi: 10.1107/S0021889805038987. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Laskowski RA, Macarthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. Procheck—a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. doi: 10.1107/S0021889892009944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mcdonald IK, Thornton JM. Satisfying hydrogen-bonding potential in proteins. J Mol Biol. 1994;238(5):777–793. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hubbard SJ, Thornton JM (1993) NACCESS Computer Program. Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University College London

- 76.Wallace AC, Laskowski RA, Thornton JM. Ligplot—a program to generate schematic diagrams of protein ligand interactions. Protein Eng. 1995;8(2):127–134. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Medek P, Benes P, Sochor J. Computation of tunnels in protein molecules using Delaunay triangulation. J Wscg. 2007;15(1–3):107–114. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kleywegt GJ, Jones TA. Detection, delineation, measurement and display of cavities in macromolecular structures. Acta Crystallogr Sect D-Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:178–185. doi: 10.1107/S0907444993011333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lawrence MC, Colman PM. Shape complementarity at protein–protein interfaces. J Mol Biol. 1993;234(4):946–950. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.DeLano WL. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. Palo Alto: DeLano; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Halliday RS, Huey R, Hart WE, Belew RK, Olson AJ. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J Comput Chem. 1998;19(14):1639–1662. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(19981115)19:14<1639::AID-JCC10>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kuntz ID, Chen K, Sharp KA, Kollman PA. The maximal affinity of ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(18):9997–10002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.9997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bembenek SD, Tounge BA, Reynolds CH. Ligand efficiency and fragment-based drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2009;14(5–6):278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhou JJ, Zhang GA, Huang W, Birkett MA, Field LM, Pickett JA, Pelosi P. Revisiting the odorant-binding protein LUSH of Drosophila melanogaster: evidence for odour recognition and discrimination. FEBS Lett. 2004;558(1–3):23–26. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)01521-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marie AD, Veggerby C, Robertson DHL, Gaskell SJ, Hubbard SJ, Martinsen L, Hurst JL, Beynon RJ. Effect of polymorphisms on ligand binding by mouse major urinary proteins. Protein Sci. 2001;10(2):411–417. doi: 10.1110/ps.31701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ban LP, Zhang L, Yan YH, Pelosi P. Binding properties of a locust’s chemosensory protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;293(1):50–54. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Leal WS, Barbosa RMR, Xu W, Ishida Y, Syed Z, Latte N, Chen AM, Morgan TI, Cornel AJ, Furtado A. Reverse and conventional chemical ecology approaches for the development of oviposition attractants for culex mosquitoes. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(8):e3045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pelosi P, Zhou JJ, Ban LP, Calvello M. Soluble proteins in insect chemical communication. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63(14):1658–1676. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5607-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Anderson AC. The process of structure-based drug design. Chem Biol. 2003;10(9):787–797. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Powers RA, Morandi F, Shoichet BK. Structure-based discovery of a novel, noncovalent inhibitor of AmpC beta-lactamase. Structure. 2002;10(7):1013–1023. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(02)00799-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lam PY, Jadhav PK, Eyermann CJ, Hodge CN, Ru Y, Bacheler LT, Meek JL, Otto MJ, Rayner MM, Wong YN, et al. Rational design of potent, bioavailable, nonpeptide cyclic ureas as HIV protease inhibitors. Science. 1994;263(5145):380–384. doi: 10.1126/science.8278812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pastor M, Cruciani G, Watson KA. A strategy for the incorporation of water molecules present in a ligand binding site into a three-dimensional quantitative structure–activity relationship analysis. J Med Chem. 1997;40(25):4089–4102. doi: 10.1021/jm970273d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.