Abstract

The hypothalamus is a neural structure critical for expression of motivated behaviours that ensure survival of the individual and the species. It is a heterogeneous structure, generally recognised to have four distinct regions in the rostrocaudal axis (preoptic, supraoptic, tuberal and mammillary). The tuberal hypothalamus in particular has been implicated in the neural control of appetitive motivation, including feeding and drug seeking. Here we review the role of the tuberal hypothalamus in appetitive motivation. First, we review evidence that different regions of the hypothalamus exert opposing control over feeding. We then review evidence that a similar bi-directional regulation characterises hypothalamic contributions to drug seeking and reward seeking. Lateral regions of the dorsal tuberal hypothalamus are important for promoting reinstatement of drug seeking, whereas medial regions of the dorsal tuberal hypothalamus are important for inhibiting this drug seeking after extinction training. Finally, we review evidence that these different roles for medial versus lateral dorsal tuberal hypothalamus in promoting or preventing reinstatement of drug seeking are mediated, at least in part, by different populations of hypothalamic neurons as well as the neural circuits in which they are located.

Keywords: Relapse, Extinction, Orexin, Reward, Satiety, Neuropeptides

Introduction

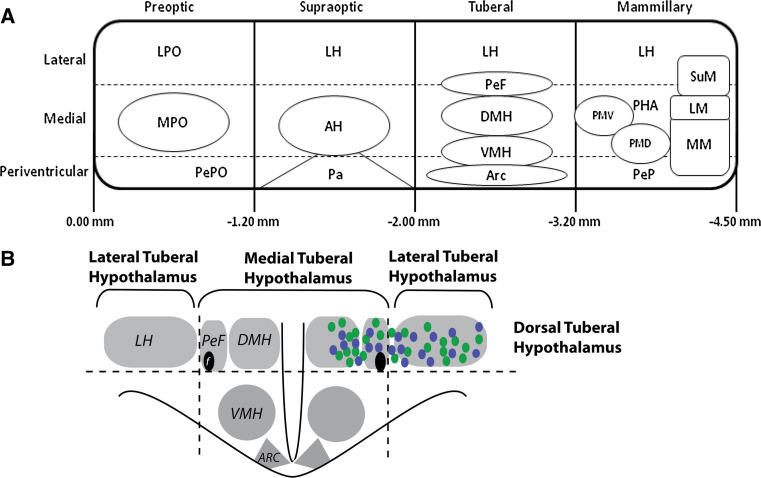

The hypothalamus is a functionally heterogeneous structure that is critical for expression of three basic classes of motivated behaviour: ingestive, defensive and reproductive behaviours, necessary for survival of the individual and the species [1]. The hypothalamus is located in the ventral section of the diencephalon [2]. It is a heterogeneous structure, divided into four rostrocaudal regions: preoptic (approximately 0.00 to −1.20 mm from the bregma), supraoptic (approximately −1.20 to −2.00 mm from the bregma), tuberal (approximately −2.00 to −3.20 mm from the bregma) and mammilary (approximately −3.20 to −4.50 mm from the bregma) (Fig. 1a) [1, 2]. There are three distinct longitudinal zones in the medial lateral plane (periventricular, medial and lateral). The periventricular zone contains a series of nuclei that comprise the neuroendocrine system. Swanson [1] proposed that the medial zone is organised into a series of distinct cell groups forming ‘behavioural control columns’ for expression of complex, coordinated motivated behaviours. The lateral zone is less differentiated, but believed to be important for behavioural state and arousal mechanisms [1]. The focus of this review is on the tuberal hypothalamus and its control over appetitively motivated behaviours. The tuberal hypothalamus has dorsal and ventral regions. The main nuclei in the dorsal region are the dorsomedial hypothalamus (DMH), perifornical hypothalamus (PeF) and lateral hypothalamus (LH). In the ventral region, the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) and arcuate (ARC) are the main nuclei (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Highly simplified schematic outlining the anatomical organisation of the hypothalamus. a Schematic representation of the four rostrocaudal regions and three mediolateral zones of the hypothalamus. This figure is adapted from Fig. 1 of [2]. A large number of the subnuclei of the preoptic and supraoptic regions are omitted for clarity, as they are not discussed within the text of this review. Numbers represent mm from the bregma. b Schematic of a coronal section of the tuberal hypothalamus depicting the anatomical organisation of the tuberal hypothalamus discussed within this review. Blue circles represent the distribution of orexin neurons, and green circles represent the distribution of MCH neurons. ARC arcuate nucleus, AH anterior hypothalamic nucleus, DMH dorsomedial nucleus, f fornix, LH lateral hypothalamus, LM, lateral mammillary nucleus, LPO lateral preoptic area, MM medial mammillary nucleus, MPO medial preoptic nucleus, Pa paraventricular nucleus, PeF perifornical nucleus, PeP, posterior periventricular, PePO preoptic periventricular nucleus, PHA posterior hypothalamic area, PMD dorsal premammillary nucleus, PMV ventral premammillary nucleus, SuM, supramammillary nucleus, VMH ventromedial nucleus

The hypothalamus was among the first brain regions implicated in reward and appetitive motivation. Early studies employing intracranial self-stimulation showed that rats would readily learn to press a lever to obtain brief focal electrical stimulation of hypothalamus [3]. Similarly, lesion studies showed that destruction of hypothalamic tissue caused profound changes in appetitive (e.g., feeding, drinking, sex) motivational states (e.g., [4]). However, concerns with the specificity of the techniques used in these early studies combined with the discovery of the catecholamines and development of pharmacologic tools to target them shifted attention away from the hypothalamus and towards the role of dopamine and the striatum. In recent years, attention has returned to the role of the hypothalamus in appetitively motivated behaviour. This has been due to at least three developments. The first was elegant molecular and genetic studies allowing a precise understanding of the role of specific hypothalamic regions and molecular signaling pathways in regulation of feeding and body weight [5]. The second was the discovery of several novel neuropeptide families expressed in the hypothalamus and subsequently implicated in reward and drug seeking [6]. The third was increased understanding of the complex neurocircuitry in which the hypothalamus sits [1]. Consequently, there is now significantly improved understanding of the role of the hypothalamus in appetitive motivation.

Here we review evidence linking the hypothalamus to appetitive motivation and the seeking of drug rewards. We focus on the tuberal hypothalamus because this is the hypothalamic region important for appetitive motivation [2]. We first review evidence implicating the hypothalamus in the regulation of feeding. We then review evidence implicating the hypothalamus in regulation of drug seeking. The common underlying theme is that distinct regions of the tuberal hypothalamus make functionally distinct contributions to these behaviours. Lateral regions of the tuberal hypothalamus are important for promoting appetitive motivation and drug seeking, whereas medial regions are important for inhibiting such motivation and drug seeking. These distinct contributions are mediated, at least in part, by different populations of hypothalamic neurons as well as the neural circuits in which they are located.

In this review we use the term ‘reward’ to refer to outcomes (e.g. food, sex and drugs of abuse) that are positive reinforcers (i.e. animals will work to obtain them). We use the term ‘appetitive motivation’ to refer generally to the processes that direct behaviour towards obtaining a reward. We use the term ‘drug seeking’ to describe the seeking of drug, illicit and licit, rewards. We use the term ‘reward seeking’ more broadly to describe seeking of drug and/or non-drug rewards.

Hypothalamus mediates bi-directional control over feeding

Early studies

A series of studies in the early 1950s provided the first evidence that discrete regions in the brain are important for motivated behaviour. Anand and Brobeck [7] studied the effects of electrolytic hypothalamic lesions on feeding behaviour in cats and rats. They demonstrated that lesions of the lateral hypothalamus (LH) abolished feeding whereas lesions of the medial hypothalamus caused animals to eat excessively. This functional dichotomy led to the influential ‘dual-center’ theory of hypothalamic control of motivated behaviour [4]. The central thesis was that the overall influence of the hypothalamus on motivated behaviour was the result of competition between excitatory influences of lateral nuclei and inhibitory influences of the medial nuclei. Feeding, for example, was considered a motivationally excitatory event mediated by the LH. Satiety, on the other hand, was considered a motivationally inhibitory event mediated by medial hypothalamic nuclei, potentially via direct inhibition of LH.

These early lesion studies were followed by intra-cranial self-stimulation (ICSS) experiments showing that LH supports robust self-stimulation in rats [8]. Importantly, LH stimulation sites that supported ICSS were also shown to elicit feeding [9, 10]. This was the first line of evidence indicating that LH may be important for motivation more generally, rather than just feeding. It was later shown that LH stimulation-induced behaviour, such as feeding, could be modified. For example, Valenstein et al. [11] reported that LH stimulation could elicit drinking when food was removed and a waterspout made available. Drinking behaviour emerged during LH stimulation and persisted when food was made available again. Thus, the behavioural consequences of LH stimulation were variable if the conditions permitted. Finally, in a review of the LH stimulation literature at the time, Wise [12] noted that LH stimulation influences behaviour by increasing motivation rather than simply increasing activity in motor systems. For example, LH stimulation had no effect on the animal when it was tested in an environment where eating was inappropriate, such as an environment that elicits fear.

The role of the medial hypothalamus (MH) as an inhibitor of LH-mediated motivated behaviour was also revealed in the early self-stimulation literature. Stimulation of the MH decreased both the LH ICSS and LH stimulation-induced feeding [9, 10]. Porrino et al. [13] provided an elegant demonstration of MH inhibition of LH self-stimulation. They implanted rats with bilateral electrodes in both LH and MH, and arranged that LH self-stimulation was preceded by stimulation of MH. It was found that prior stimulation of MH, at inter-pulse intervals of up to 15 s, decreased the rate of LH self-stimulation. Interestingly, there was a difference between dorsal and ventral MH. Ventral MH stimulation decreased LH ICSS at small inter-pulse intervals (0.1–1 s), while dorsal MH stimulation decreased LH ICSS at the larger inter-pulse intervals (2–20 s). These data indicate that although the ventral and dorsal medial hypothalamus exerts inhibitory control over LH, the exact mechanism of such control may differ between them. Regardless, these data indicate that increased activity in both the ventral and dorsal MH can serve to decrease LH-dependent behaviours.

It is important to note that these historical lesion and stimulation data provided early signs that the LH and MH control complex motivational states and are not simply a neural ‘feeding centers’. Moreover, although the techniques used in many of these early studies have been superseded, many findings have been validated by modern techniques. For example, stimulation of LH neurons by infusions of the excitatory amino-acid NMDA, which has no effect on fibers of passage, increases food intake [14], whereas cell-body-specific lesions of the LH decrease feeding [15, 16]. Furthermore, the discovery of the neural substrates of leptin-mediated feeding inhibition (see [5] for review), and the discovery of orexigenic and anorexigenic neuropeptides have greatly increased our understanding of the hypothalamic control over feeding. Remarkably, modern molecular neuroscience is converging on a similar understanding to that promoted by early lesion and self-stimulation studies.

Molecular evidence linking hypothalamus to feeding

The discovery of leptin as a satiety signal greatly increased our understanding of the neural mechanisms of feeding. Leptin regulates energy intake via a negative feedback system, which is mediated in large part by the hypothalamic ARC. Leptin receptor mRNA expression is most dense in the medial tuberal hypothalamic nuclei ARC, VMH and DMH [17]. Two distinct populations of neurons are found within the medial and lateral ARC. Medial ARC neurons promote feeding, and are identified by their expression of neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti-related peptide (AgRP) [5]. In these neurons, leptin receptor activation increases signaling cascades that inhibit cellular activity [18, 19]. Lateral ARC neurons inhibit feeding, and are identified by their expression of cocaine and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) and α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (αMSH) [5]. Kristensen et al. [20] showed that CART expression, specifically in ARC neurons, is significantly decreased in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice compared to wild-type littermates. Furthermore, intravenous (i.v.) administration of leptin increases c-Fos expression in CART/αMSH ARC neurons [21]. In summary, leptin can decrease feeding by both inhibiting NPY ARC neurons and activating CART ARC neurons. Importantly, this role for ARC is dependent on modulating activity at downstream targets.

ARC neurons mediate their effects on feeding via projections to other regions of the hypothalamus, including dense projections to both the medial and lateral dorsal tuberal hypothalamus (e.g. [22, 23]). This anatomical organisation has led to the proposal that ARC is the nodal point in the hypothalamic regulation of energy balance [24]. In this model, ARC acts as a sensory structure that detects energy levels in the blood stream (i.e. leptin) and communicates this information to other regions of the hypothalamus. This role for ARC as a primary sensory structure that in turns projects to regions in the tuberal hypothalamus (i.e. DMH, PeF and LH) suggests that tuberal hypothalamic neurons are second-order neurons in the “bottom-up” (i.e. from the periphery) control of feeding [24]. This is important, because as reviewed below, these same tuberal hypothalamic neurons can be activated to regulate drug and reward seeking in a “top-down” manner from cortical regions.

VMH, located in the ventral part of the tuberal hypothalamus (Fig. 1b), is critical for the inhibition of feeding, or satiety (see [5] for review). However, there is also evidence that DMH (Fig. 1b), located in the dorsal tuberal hypothalamus, is also important for satiety expression. One line of evidence comes from study of the satiety factors cholecystokinin (CCK) and CART. Continuous i.p. infusion of CCK-8 (the octapeptide of CCK), via indwelling catheters, reduces meal sizes [25], whereas i.c.v. infusion of CART dose-dependently reduces feeding [20, 26]. The satiety-inducing effects of CCK are dependent on DMH. For example, DMH lesions abolish CCK-induced inhibition of feeding [27], and intra-DMH infusion of CCK reduced food intake for up to 24 h [28]. Finally, CCK [28, 29] and CART [26] increase c-Fos expression in the DMH and periventricular hypothalamus (PVH).

Surprisingly, intra-DMH infusions of CART increase feeding [30]. One possible explanation is that i.c.v. CART infusions may disinhibit DMH, potentially via activation of neurons in the arcuate nucleus (ARC), whereas intra-DMH infusion of CART directly inhibits DMH neurons. The CART receptor has not been cloned; however in vitro experiments indicate it is a G-protein coupled receptor that signals via Gi/o, supporting an inhibitory post-synaptic effect [31]. As such, intra-DMH infusion of CART may increase feeding via inhibition of DMH neurons. Indeed, there is some evidence that pharmacological manipulations of medial hypothalamic neurons can remove an inhibitory control over feeding. Will et al. [32] demonstrated that functional inactivation of DMH, via muscimol, increased high fat feeding. Thus, pharmacological experiments investigating the neural mechanisms of satiety have identified the medial hypothalamus as a structure that exerts inhibitory control over feeding.

The promotion of feeding by LH is best demonstrated by the presence of orexigenic neuropeptide expression. The neuropeptide orexin is expressed primarily in dorsal tuberal hypothalamic (both medial and lateral) neurons [33, 34]. The prepro-orexin gene encodes two peptides, orexin A and orexin B [33], also known as hypocretin A and hypocretin B [34]. Sakurai et al. [33] were the first to demonstrate that i.c.v. infusion of both orexin A and orexin B dose-dependently increases food intake in rats. Furthermore, Sakurai et al. [33] showed that 48-h food deprivation increases hypothalamic prepro-orexin mRNA. Another orexigenic peptide, melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH), is also expressed in the dorsal tuberal hypothalamus, as well as the dorsally adjacent zona incerta [35]. Qu et al. [36] demonstrated that i.c.v. infusion of MCH potently induces feeding in mice, indicating MCH also promotes feeding. Interestingly, orexin and MCH are expressed in distinct populations of neurons in the hypothalamus [23]. These pharmacological studies provide evidence that neuropeptides expressed in LH promote feeding.

The orexin system is also important for arousal, maintaining alertness and preventing transition into sleep [37]. Consistent with a role in arousal, narcolepsy is associated with deficits in the orexin system [38–40], and orexin neurons are more active during periods of arousal such as wakefulness [41] or after injections of the stimulant amphetamine [42]. The multiple functions of orexin may be a consequence of the fact that orexin neurons are expressed in both the lateral and medial dorsal hypothalamus [34, 43]. Evidence for functionally distinct populations of orexin neurons based on their anatomical location (medial or lateral) has been demonstrated (see [44]) and will be discussed in detail below.

In summary, modern molecular neuroscience has strongly implicated the tuberal hypothalamus in regulation of feeding. Of particular importance here are findings that the lateral dorsal (i.e. LH) and medial dorsal (MDH) regions of the tuberal hypothalamus exert opposing influences on feeding. Neurons in the lateral dorsal regions promote feeding, whereas neurons in the medial dorsal regions appear to promote satiety and/or inhibit feeding. This dichotomy in the control of feeding is revealed by the actions or orexigengic neuropeptides such as orexin and MCH as well as the anorexigenic actions of neuropeptides such as CART and CCK. This work not only confirms the findings from early studies on hypothalamic ICSS, it also suggests a model of the function of hypothalamic contributions to motivated behaviour with lateral regions promoting, and medial regions inhibiting, appetitive motivation. In the following sections we review the evidence that precisely such an organisation characterises tuberal hypothalamic contributions to drug seeking.

The hypothalamus and drug seeking

In models of drug seeking, animals, typically rats, are trained to respond for a drug reward so that emission of a particular behaviour (e.g. lever pressing) is reinforced via delivery of a drug reward (e.g. intravenous cocaine or delivery of alcohol to a drinking cup). Under these conditions, responding increases. Responding can then be extinguished by arranging that the behaviour no longer produces the drug reward. This extinction does not permanently erase the drug-seeking response. Evidence from a variety of recovery phenomena such as reinstatement, spontaneous recovery and renewal [45, 46], suggests that the original association remains largely intact after extinction training [45–47]. Consequently, extinction is thought to involve new learning that masks, or inhibits, the original drug-seeking response [48]. Thus, in these models, animals can express low levels of drug seeking due to the active inhibition of drug seeking imposed by prior extinction training or they can express high levels of drug seeking due to reinstatement caused by presentations of drug-associated stimuli, stressors or the drug itself. In this section we review the accumulating evidence that the hypothalamus is important for promoting drug seeking during reinstatement as well as for inhibiting drug seeking after extinction.

Promotion of drug seeking by lateral hypothalamus

Hypothalamic neurons, especially those in the LH, are responsive to drug-associated stimuli and critical for the expression of drug-seeking behaviours, including drug seeking elicited by associated stimuli. As reviewed above in Sect. 2.2, there are two important neuropeptide systems in LH that contribute to the promotion of feeding: orexin and MCH. This section will review some of the key evidence supporting the claim that LH does not just mediate the primary reinforcing effect of rewards such as food or drugs of abuse. Rather, the LH also mediates the behavioural impact of drug-associated stimuli whose motivational significance is learned.

Studies using immunohistochemical detection of the immediate early gene c-Fos as a marker of activity have provided correlative evidence that LH is important for the reinstatement of drug and reward seeking. LH neurons are recruited by drug-associated stimuli. For example, cue-induced reinstatement of alcohol seeking [49], and context-induced reinstatement of sucrose [50], alcoholic beer [51] and cocaine [52] seeking all increase c-Fos expression in LH neurons. In a recent study, Marchant, Hamlin and McNally [53] reported that functional inactivation of LH via infusions of the GABA agonists baclofen and muscimol abolished context-induced reinstatement of both sucrose and alcoholic beer seeking. Thus, activity in the LH is causally related to context-induced reinstatement of alcoholic beer and sucrose seeking. It remains to be shown whether LH is also causally important for context-induced reinstatement of drug seeking for an intravenous reward such as cocaine. However, given that Hamlin et al. [52] showed increased c-Fos expression in the LH is associated with reinstatement of cocaine seeking, this possibility is likely.

The orexin system is important for the reinstatement of extinguished drug seeking in animal models of relapse. Systemic administration of SB 334867 prevents cue-induced reinstatement of extinguished alcohol [54] and cocaine seeking [55], as well as attenuating context-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking [56]. The orexin system has also been implicated in stress-induced reinstatement of drug seeking. I.c.v infusions of SB 334867 block footshock-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking [57]. Reinstatement of both alcohol and sucrose seeking by Yohimbine, an α-2 adrenoreceptor antagonist that induces a stress-like state, is also blocked by prior administration of SB 334867 [58]. These studies show that orexin activity is also important for drug seeking that is elicited by drug-associated stimuli, or stressors.

Interestingly, it has also been shown that i.c.v. infusions of orexin increased ICSS thresholds, indicating that orexin may also mediate stressful or aversive motivational states [57]. This is perhaps inconsistent with the idea that the orexin system mediates reward. However, Harris et al. [44] have argued that MDH orexin neurons are functionally distinct from LH orexin neurons; specifically MDH orexin neurons are important for arousal. Indeed, MDH orexin neurons have different afferent inputs [59], and efferent outputs [60] to LH orexin neurons, indicating they may have different functions. We will review further evidence that MDH orexin neurons mediate functions different from that of LH in Sect. 3.2 below.

In an influential study, Harris et al. [44] demonstrated a role for the LH orexin neurons in drug-seeking behaviour. Using a conditioned place preference (CPP) model, they showed that tests for morphine, cocaine or food CPP were associated with increased c-Fos expression in LH orexin neurons. Importantly, this effect was anatomically restricted to LH orexin neurons. There was no difference in the percentage of orexin neurons expressing c-Fos in the medially adjacent dorsal tuberal hypothalamus (i.e. MDH: including both DMH and PeF). Activation of LH orexin neurons, by infusion of the Y4 receptor agonist rat pancreatic polypeptide, reinstated extinguished morphine CPP. This effect was blocked by systemic administration of the orexin 1 receptor (OX1R) antagonist SB 334867. Finally, intra-VTA infusion of orexin-A reinstated extinguished morphine CPP, suggesting that LH orexin neurons mediate CPP via projections to VTA. These results demonstrated for the first time an important role specifically for orexin neurons in the LH in mediating drug reward and drug seeking.

Additional studies have demonstrated an important role for LH orexin neurons in drug seeking in different experimental paradigms. Increased c-Fos expression in LH orexin neurons is associated with context-induced reinstatement of alcoholic beer seeking [51], and the level of responding during reinstatement is positively correlated with the percentage of orexin neurons expressing c-Fos. Interestingly, there was no specific activation of LH orexin neurons during context-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking [52] or sucrose seeking [50]. Activation of LH orexin neurons during context-induced reinstatement appears to be specific to alcoholic beer seeking. A similar finding was reported recently by Jupp et al. [61] who showed that systemic injection of SB 334867 reduced the motivational properties of alcohol but not sucrose. In contrast to these results is the finding that systemic injection of SB 334867 attenuates context-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking [56]. However, Hamlin et al. [52] reported that after cocaine self-administration, simply handling rats and placing them in a test chamber increased c-Fos expression in orexin neurons in both PeF and DMH. Thus, systemic administration of SB 334867 may block the arousal elicited by return to the testing chamber and so prevent reinstatement of cocaine seeking indirectly.

Consistent with the idea that orexigenic LH peptides are important for drug seeking, Chung et al. [62] recently demonstrated a role for MCH in drug seeking. Using whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiology, they found that bath applied MCH increases spike firing only in the presence of dopamine D1-like receptor (D1R) and D2-like receptor (D2R) agonists, indicating that MCH depends on dopamine to increase the activity of AcbSh neurons. MCH is also important for the behavioural responses to cocaine. For example, i.c.v. administration of MCH potentiated cocaine-induced locomotor activity. Finally, Chung et al. [62] demonstrated that the MCH system is also important for reinstatement of extinguished cocaine seeking. Both cue- and cocaine-induced, but not stress-induced, reinstatements are blocked by i.c.v. administration of the MCH1R antagonist TPI1361-17. Thus the MCH system is important for the behavioural effects of cocaine as well as reinstatement of extinguished cocaine seeking. Further work is needed to specifically link these effects to LH MCH neurons. However, it does provide further evidence of the overlap between orexigenic mechanisms and drug seeking.

Inhibition of drug seeking by the medial hypothalamus

As reviewed above, orexigenic neural mechanisms in the lateral hypothalamus are co-opted by drugs of abuse and are important mediators of drug-seeking behaviour. As was reviewed in Sect. 2.2, an important conclusion from early intracranial self-stimulation experiments and more recent molecular neuroscience studies is that the lateral and medial dorsal regions of the tuberal hypothalamus exert opposing influences on appetitive motivation. The demonstration that hypothalamic orexigenic mechanisms are important for drug seeking raises the possibility that medial dorsal hypothalamic anorexigenic mechanisms may inhibit drug seeking. One approach to testing this possibility is by studying the mechanisms that inhibit drug seeking after extinction training, the behaviour that is observed during an extinction test mediated by an active process of response inhibition [48]. Thus, an extinction test has the ability to provide an understanding of the neural substrates of this response inhibition.

Recently, we provided evidence that MDH is important for extinction expression, which is defined as the expression of an extinguished reward-seeking response [63]. In this study, rats were initially trained to respond to 4% alcoholic beer. After 7 days of self-administration training, rats were given extinction training for 4 days. They were tested for extinction expression the next day. Intra-MDH infusion of CART, an inhibitory neuropeptide [31], dose-dependently prevented the expression of extinction and so reinstated responding. A similar result was found in rats that were originally trained to respond to sucrose, indicating a more general role for MDH in mediating extinction expression. These results suggest that selective inhibition of MDH, by CART, abolished the expression of extinction and thus reinstated extinguished reward seeking.

An alternative explanation of these results is that intra-MDH infusion of CART non-selectively increased drug and reward seeking. As such, we completed a series of control experiments to test this interpretation. We first demonstrated that intra-MDH infusion of CART only changed the responding in rats that expressed extinction. There was no effect on responding when rats were tested for context-induced reinstatement or in rats that were not initially trained to respond for any reward. This indicates that intra-MDH infusion of CART reinstated reward seeking by selectively inhibiting extinction expression. Furthermore, we found that intra-LH infusion of CART had no effect on extinguished responding, demonstrating anatomical specificity of this effect. Collectively, these data provide evidence that MDH is a structure that mediates extinction expression by exerting inhibitory control over reward seeking after extinction training.

Hypothalamic bi-directional control over drug seeking is mediated by specific neural circuitry

The evidence reviewed above suggests functional differences between the LH and MDH in drug seeking. LH is important in promoting reinstatement or relapse to drug seeking, whereas MDH is important for inhibiting drug seeking and hence in promoting abstinence. These opposing roles in promoting versus inhibiting drug seeking can be linked to the neural circuits in which the LH and MDH are located.

Hypothalamic circuitry promoting drug and reward seeking

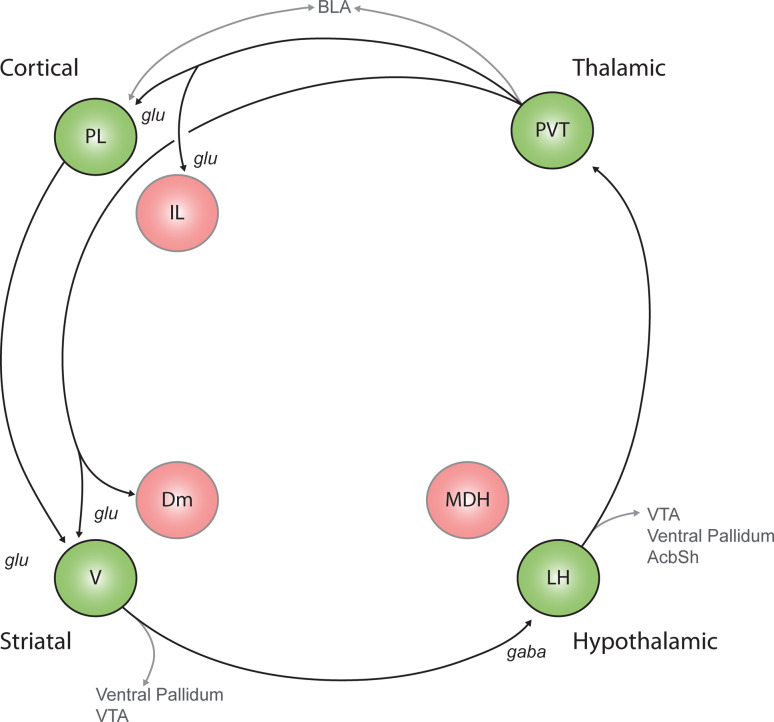

In this section we review some of the major afferents of the dorsal tuberal hypothalamus and the evidence for their involvement in promoting and inhibiting drug seeking (Fig. 2). We focus on afferents that have been implicated in drug seeking and appetitively motivated behaviour.

Fig. 2.

A model depicting the neural circuitry associated with reinstatement of extinguished drug and reward seeking. The promotion of reward seeking is proposed to be mediated in large part by a circuit comprising the prelimbic prefrontal cortext (PL), ventral nucleus accumbens shell (V), lateral hypothalamus (LH) and paraventricular thalamus (PVT). We are proposing that the continued activation of this cortical-striatal-hypothalamic-thalamic-cortical “loop” is important for drug seeking during reinstatement. Multiple outputs from this loop, such as to the ventral pallidum and brainstem, enable expression of behaviour. Functional inhibition of all of these structures attenuates reinstatement of reward seeking, indicating that each node of this circuit is required to promote reward seeking. Evidence for direct V→LH and PVT→V pathways is reviewed in Sect. 3.1. Connections with this circuit and other structures implicated in these behaviours are displayed in grey. AcbSh nucleus accumbens shell, BLA basolateral amygdala, Dm dorsomedial accumbens shell, glu glutamate, IL infralimbic prefrontal cortex, MDH medial dorsal hypothalamus, VTA ventral tegmental area

Reward-related LH afferent projections

LH is anatomically placed to mediate motivated behaviours via afferent projections from structures including AcbSh [59, 64], PFC, the lateral septum, VTA [59] and amygdala [65, 66].

Cortical→striatal→hypothalamic

LH is unique among hypothalamic structures because it is the only structure to receive input from the striatum. Striatal projections to the LH primarily arise from the medial AcbSh, but also include some projections from the lateral AcbSh and Accumbens Core (AcbCo) [67, 68]. There is emerging evidence suggesting that AcbSh is important for drug seeking, particularly in the context-induced reinstatement model. Context-induced reinstatement of both sucrose and alcoholic beer seeking is associated with increased c-Fos expression specifically in ventral (AcbShV) AcbSh neurons [50, 51]. The reinstatement specific c-Fos expression in AcbShV is blocked by systemic administration of the D1R antagonist SCH 23390 [50, 51]. Furthermore, intra-AcbSh infusion of SCH 23390 blocks context-induced reinstatement of heroin [69] and alcohol [70] seeking, and intra-AcbSh infusion of the mGluR agonist LY 372968 blocks context-induced reinstatement of heroin [71] and sucrose [72] seeking. Finally, AcbShV neurons that are active during context-induced reinstatement project directly to LH [53]. Thus, context-induced reinstatement of reward seeking is associated with activation of a direct AcbShV→LH pathway.

There is additional evidence for AcbSh regulation over other LH-dependent reward behaviour. Consistent with overlap in the neural mechanisms of drug seeking and feeding, AcbSh-mediated feeding behaviours depend on LH. Maldonado-Irizarry et al. [73] made the initial discovery that blockade of AMPA and kainate receptors in the medial AcbSh caused rats to eat voraciously. This effect was specific to the medial AcbSh, because AcbCo infusions had no effect on feeding. Furthermore, intra-AcbSh infusions of GABA receptor agonists also increase feeding in a similar manner [74]. To test whether this effect was dependent on LH, Maldonado-Irizarry et al. [73] concurrently inactivated LH, via muscimol infusions, prior to intra-AcbSh DNQX infusions, and found that this attenuated DNQX-induced feeding, while not changing locomotor activity. These findings suggest an important role for AcbSh GABAergic medium spiny neurons (MSN) in the control of feeding.

AcbSh GABAergic MSN appears to control feeding by exerting tonic inhibition over a glutamatergic interneuron in LH. Stratford et al. [75] demonstrated that LH infusions of GABA receptor antagonists at the tuberal hypothalamic level had no effect on feeding, indicating AcbSh does not directly inhibit LH. However, LH infusion of the NMDA receptor antagonist AP5 blocked AcbSh inactivation induced feeding, suggesting that AcbSh projections to LH mediate feeding via an intermediate glutamatergic projection. There is some anatomical support for this. Sano and Yokoi [76] used a genetic approach to label MSN projection neurons in the entire striatum. They found that MSN projections terminate primarily in the preoptic/supraoptic region of LH, which contains glutamatergic neurons but is anterior to all orexin and MCH neurons. This pattern of connectivity has also been demonstrated by Thompson and Swanson [77]. It implies that inactivation of AcbSh neurons releases inhibitory control over glutamatergic projections to the tuberal LH. Regardless of the specific mechanism, functional inactivation of AcbSh increases activity in LH neurons. Stratford et al. [75] found that c-Fos expression in LH was greatly increased by AcbSh inactivation. Millan et al. [78] reported similar findings in a drug self-administration paradigm. Functional inactivation of AcbSh, which reinstated extinguished alcoholic beer seeking, also increased the expression of c-Fos in LH neurons. Furthermore, concurrent inactivation of LH blocked AcbSh-inactivation induced reinstatement.

Taken together, these findings suggest that an AcbSh→LH pathway is critical for drug and reward seeking. They also suggest that this pathway involves at least two distinct populations of hypothalamic neurons: (1) glutamatergic neurons in the more anterior preoptic/supraoptic LH, which receive direct input from AcbSh, and (2) neuropeptidergic neurons located more caudally in the LH, which receive input from the anterior LH glutamatergic neurons.

The importance of cortical projections to AcbSh in controlling reinstatement behaviour is yet to be specifically tested. Cortical projections to the striatum are remarkably topographical [79]. Cortical innervation of medial AcbSh arises mainly from infralimbic prefrontal cortex (IL or vmPFC), but also includes prelimbic prefrontal cortex (PL or dmPFC) [79–81]. There are surprisingly few studies examining the role of the PFC→AcbSh pathway in drug seeking. Other cortical-striatal circuits have been demonstrated as important for reinstatement of drug seeking. For example, functional inactivation of dmPFC or AcbCo blocks reinstatement of cocaine seeking elicited by cocaine prime [82] or footshock stress [83]. AcbCo is thought to mediate drug seeking via projections to ventral pallidum [82, 84]. The importance of this cortical-striatal-pallidal pathway in drug seeking is well documented [85]. However, there is less evidence that a PFC→AcbSh pathway is important for drug seeking. Given the importance of AcbSh in drug-seeking behaviour, more experimental data on this circuit are warranted.

Amygdalo→hypothalamic

Basolateral amygdala (BLA) is important for attributing motivational value to conditioned stimuli [86, 87], and bilateral lesions of BLA attenuate cue-potentiated feeding [86, 88]. BLA may mediate this effect via its effects on LH. The posterior BLA sends direct projections to LH [65, 66], and Petrovich et al. [89] demonstrated that disconnection of BLA and LH abolished potentiation of feeding elicited by a food-associated stimulus. In addition, Petrovich et al. [65] reported that presentation of the food-paired stimulus increased immediate early gene expression in BLA and orbitomedial PFC neurons projecting to LH. Thus, cue-potentiated feeding appears to be mediated by activation of a direct BLA→LH pathway.

BLA is important for drug-seeking behaviour. For example, context-induced reinstatement of sucrose [50], alcoholic beer [51] and cocaine [52] seeking are each associated with increased c-Fos expression in BLA. These increases are not blocked by systemic administration of SCH 23390 [50–52]. BLA is critical for context-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking because functional inactivation blocks reinstatement [90]. Furthermore, opioid signalling in BLA is also important because intra-BLA infusion of naloxone dose-dependently attenuates context-induced reinstatement of alcohol seeking [91]. BLA may mediate drug seeking via projections to PFC. Fuchs et al. [90] conducted disconnection experiments to determine whether serial connections between BLA and PL are important for context-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. They found that both contra- and ipsilateral inactivation of BLA and dmPFC attenuated reinstatement. The finding that ipsilateral inactivation blocks reinstatement complicates interpretation, but does suggest functional interaction between BLA and dmPFC in context-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. However, a causal role for the BLA→LH pathway in drug seeking is yet to be demonstrated.

Cortical→hypothalamic

To date there have been few studies examining cortical control of LH-mediated behaviours. Medial prefrontal cortex serves a critical role in the reinstatement of drug seeking and the learned control over feeding (e.g. [82]). As reviewed above, Petrovich et al. [65] showed that projections from vmPFC to LH are activated by a cue that potentiates feeding in sated rats. Petrovich et al. [92] have also shown that lesions of vmPFC block the ability of a food-associated context to promote feeding, indicating this cortical region is important. However, to date there are no functional disconnection studies demonstrating a causal relationship for cortical projections to LH in the promotion of feeding or drug seeking.

Summary

The LH is well positioned anatomically to mediate appetitively motivated behaviours such as drug seeking and feeding. The AcbSh→LH and BLA→LH projections are the only pathways implicated in these behaviours by both functional neuroanatomical and pharmacological intervention. The involvement of an AcbSh→LH pathway in drug seeking is particularly notable. The striatum and nucleus accumbens in particular have long been associated with appetitive motivation and drug seeking. The evidence reviewed here identifies LH as a critical target of accumbens-mediated drug seeking.

LH efferent projections

Reward and arousal related efferent projections from LH include VTA [60], PFC [93], lateral habenula and locus coeruleus (LC) [94]. LH also sends projections to the midline thalamus including the paraventricular thalamus (PVT) [95, 96].

Hypothalamic→thalamic→cortical/striatal

The hypothalamus projects extensively to the midline thalamic nuclei [97], including PVT. Hypothalamic-thalamic projections are thought to be an important way in which information from the hypothalamus reaches the cortex [1, 97]. Hypothalamic neurons expressing different peptides appear to synapse onto single PVT neurons projecting to AcbSh [98], and PVT neurons are activated by hypothalamic peptides [99]. Both orexin and CART neurons from the tuberal hypothalamus project to PVT [95, 96]. PVT has been proposed to function as an interface between the hypothalamus and cortical-striatal projections (e.g. [100]). For example, single PVT neurons send collateral axons to both PFC and AcbSh [101]. Efferent projections from PVT include PFC, medial AcbSh and BLA [102–105], and these are thought to be glutamatergic [106]. Interestingly, these structures have all been implicated in reward-related behaviours. Thus, increased activity of PVT neurons may serve to coordinate activity in cortical, striatal and amygdala structures during drug-seeking behaviours.

Recent understanding of PVT function has been extended to include drug-seeking behaviours. Dayas et al. [49] demonstrated activity in PVT neurons is associated with reinstatement of alcohol seeking. In this experiment, rats were trained to respond to ethanol in the presence of a discriminative stimulus (S+), while another stimulus (S-) was paired with unavailability of ethanol. After extinction, in the absence of any stimuli, reinstatement could be induced by presentation of S+, and this reinstatement was associated with increased c-Fos expression in PVT. Moreover, PVT lesions prevent context-induced reinstatement of alcoholic beer seeking, showing that PVT contributes to reinstatement across different drug reinforcers and models of reinstatement [107].

PVT may promote drug seeking via glutamatergic projections to PFC, BLA and AcbSh [102–106]. PVT projections to AcbSh modulate dopamine release in AcbSh. Using fast-scan cyclic voltammetry, Parsons, Li and Kirouac [108] reported that stimulation of PVT in an anaesthetised rat causes increased oxidation currents in AcbSh, indicative of dopamine release. Remarkably, this occurs after lidocaine inactivation of VTA, indicating that PVT activity can modulate dopamine release in AcbSh independently of dopamine neuron firing [108]. Given the importance of AcbSh dopamine for drug and reward seeking [69, 70], activation of this pathway is one potential mechanism for reinstatement of drug seeking behaviour. This possibility is supported by the finding that AcbSh projecting PVT neurons are recruited during context-induced reinstatement of reward seeking [107]. These findings suggest that PVT projections to AcbSh are important for drug seeking.

Alternatively, the PVT→AcbSh pathway may promote drug seeking by acting on cholinergic interneurons in AcbSh. There is evidence that thalamo-striatal projections innervate striatal cholinergic interneurons [109, 110]. Optogenetic activation of cholinergic interneurons suppresses activity in MSN output neurons and attenuates expression of cocaine CPP [111]. Given that a decrease in MSN activity is associated with consummatory behaviour [112–114], and that functional inactivation of AcbSh can also reinstate extinguished drug and reward seeking [78, 115], activation of AcbSh cholinergic interneurons by PVT may be another mechanism by which PVT promotes drug and reward seeking. PVT projects extensively to the prefrontal cortex [102, 103]; however, the role of a PVT-cortical pathway in drug seeking is yet to be demonstrated.

The contribution of specific hypothalamic neuropeptide projections to PVT in drug-seeking behaviours is unclear. There are dense orexin terminal fibres in PVT [96], and OX1R and orexin 2 receptor (OX2R) expression is high there [116, 117]. Given the importance of orexin in drug-seeking paradigms (e.g. [44, 118, 119]), orexin signalling in PVT may be important for drug seeking. However, there is no evidence to support this. Indeed, a recent study by James et al. [120] found that blockade of OX1R in PVT had no effect on cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. Moreover, orexin signalling in PVT may generate an aversive motivational state [121–123] and antagonism of OX2R in PVT blocks conditioned place aversion produced by naloxone-precipitated morphine withdrawal [124]. In summary, increasing evidence supports a role for PVT in reinstatement of extinguished drug seeking. However, a role of the specific LH→PVT pathway is yet to be shown.

Hypothalamic→brainstem

LH projections to the midbrain and hindbrain include VTA, periaqueductal grey, parabrachial nucleus and nucleus of the solitary tract [125]. Of these, projections to the VTA are well studied and of significant interest given the widely accepted role of the VTA in appetitive motivation and learning. LH orexin neurons project to the VTA [60], and mRNA for the orexin receptors is expressed in VTA neurons [116, 117]. Orexin acts post-synaptically to increase cell firing in VTA neurons that express both dopamine and GABA [126]. Intra-VTA infusion of orexin increases dopamine dialysate levels in accumbens [127], indicating that LH-induced activation of orexin receptors in VTA has the potential to increase dopamine signaling in AcbSh. Furthermore, intra-VTA infusion of the OX1R antagonist SB 334867 attenuates morphine CPP [127] and attenuates locomotor sensitization associated with repeated cocaine administration [128]. Thus, VTA is an important target of LH projections.

The LH→VTA orexin pathway is also important for generating the context-drug reward associations that arise in CPP preparations. Harris et al. [119] first demonstrated that bilateral excitotoxic lesions of the LH prior to training prevent the development of morphine CPP, indicating that LH is necessary for the formation of morphine CPP. Harris et al. [119] then showed that unilateral excitotoxic LH lesions, combined with contralateral intra-VTA infusion of SB 334867, blocked acquisition of morphine CPP. Currently there is only a single study implicating this pathway in reinstatement of extinguished drug seeking. James et al. [120] found that blockade of OX1R in VTA prevented cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking.

Summary

The LH is an important site of convergence of cortical, amygdaloid and ventral striatal inputs. LH neurons, in turn, project extensively to the PVT and VTA. With afferents from the ventral striatum, and efferents to the PVT, which in turn projects to the cortex and striatum, the LH is an important node in corticostriatal-thalamic loops that control appetitive motivation and drug seeking. This position is further reinforced by the finding that LH neurons project to the VTA to influence dopamine neurons. Dopamine serves an important role in modulating information flow through corticostriatal-thalamic loops and has been posited to facilitate the translation of activity in these loops into behavioural actions (e.g. [129]). Although much more work is needed, the evidence reviewed here suggests that the LH is a critical component of the neural networks maintaining motivation and promoting action.

Hypothalamic circuitry inhibiting drug seeking

The extinction of drug seeking is an active process that inhibits drug seeking. The neural mechanisms of this inhibition are beginning to be elucidated (e.g. [130, 131]). In this section we will review evidence for the existence of a circuitry involving MDH that actively inhibits drug seeking after extinction training (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

A model depicting the neural circuitry associated with the expression of extinction of drug and reward seeking. The key feature of this model is that this circuit inhibits reward seeking via inhibition of activity in the cortical-striatal-hypothalamic-thalamic-cortical loop promoting reinstatement. The extinction circuit converges onto the reward-seeking circuit at two points, the lateral hypothalamus (LH) and paraventricular thalamus (PVT). Evidence for direct Dm→LH and MDH→PVT pathways is reviewed in Sect. 3.2. The AcbSh nucleus accumbens shell, BLA basolateral amygdala, Dm dorsomedial accumbens shell, glu glutamate, IL infralimbic prefrontal cortex, LHa lateral hypothalamus anterior, MDH medial dorsal hypothalamus, VTA ventral tegmental area

Cortical→striatal→hypothalamic

The IL region of prefrontal cortex is important for expression of extinction of drug seeking. This evidence comes primarily from studies employing pharmacological manipulations. Peters et al. [115] demonstrated that functional inactivation of IL via infusions of baclofen and muscimol prevented expression of extinction and so reinstated extinguished cocaine seeking. Peters et al. [115] also showed that pharmacological stimulation of IL, via infusions of the glutamate agonist AMPA, attenuates cocaine-primed reinstatement. These findings demonstrate that activity in the IL is sufficient to inhibit drug seeking. IL is also important for the consolidation of extinction of drug seeking. LaLumiere, Niehoff and Kalivas [132] demonstrated that functional inactivation of IL after extinction training sessions impaired retention of extinction. Finally, Ovari and Leri [133] demonstrated that functional inactivation of the IL robustly reinstated extinguished heroin CPP. Together, these studies suggest that IL may be an important site for the inhibition of drug seeking after extinction training.

However, recent findings suggest that the role of the IL in drug seeking is more complex. Bossert et al. [134] reported that context-induced reinstatement of heroin seeking was associated with neuronal activation in IL. Bossert et al. [134] then showed that selective inactivation of these activated neurons could prevent context-induced reinstatement. This finding, in contrast to those reported above, implicates the IL in expression of reinstatement. The reason for the discrepancies between studies showing IL contributions to extinction versus reinstatement remains unclear. One potential account for this is the finding that there are distinct populations of IL neurons projecting to distinct regions of the ventral striatum (see below).

AcbSh is important for the expression of extinction. Peters et al. [115] reported that functional inactivation of AcbSh prevented expression of extinction and so reinstated extinguished cocaine seeking. This effect has been replicated in rats that were initially trained to respond to 4% alcoholic beer [78], indicating that AcbSh mediates extinction across different reinforcers. Peters et al. [115] also provided evidence that cortical-striatal circuitry is important for the inhibition of cocaine seeking. They reported that disconnection of the IL→AcbSh pathway inhibited expression of extinction of cocaine seeking. However, ipsilateral IL-AcbSh infusions had the same effect [115], which potentially limits conclusions regarding the role of a direct IL→AcbSh pathway in extinction expression.

Extinction training has been linked with plasticity of glutamatergic receptor expression in AcbSh. Sutton et al. [135] demonstrated that extinction of cocaine, but not sucrose, seeking caused a transient upregulation of the AMPA receptor subunits, GluR1 and GluR2/3, compared to rats in abstinent conditions. Furthermore, the level of extinction expression was positively correlated with GluR1 expression. This difference was also evident in a reinstatement experiment, whereby rats with the highest extinction-induced GluR1 expression levels showed lowest levels of cue-induced reinstatement. Sutton et al. [135] also showed that viral-mediated overexpression of both GluR1 and GluR2 subunits in AcbSh reduced cocaine seeking and reduced stress-induced reinstatement. These findings provide evidence for a role of AcbSh glutamate signalling in extinction expression. Finally, extinction-related plasticity in glutamatergic systems is not limited to AcbSh. Knackstedt et al. [136] have shown that extinction of cocaine seeking results in changes in Homer1b/c and mGluR5 expression in AcbCo. Taken together, these findings suggest that the actions of glutamate in AcbSh may be critical for the inhibition of drug seeking.

Indeed, there is evidence that a glutamatergic projection from the BLA to AcbSh is important for the expression of extinction of drug seeking. Millan and McNally [137] showed that infusions of the AMPA receptor antagonist NBQX into the AcbSh prevented the expression of extinction. This effect was dose-dependent and specific to extinction because the infusions had no effect in rats tested under a progressive ratio schedule. It was then demonstrated that disconnection of posterior BLA from AcbSh, via infusions of baclofen and muscimol into the BLA in one hemisphere and NBQX into the contralateral AcbSh, disrupted expression of extinction. This shows that a BLA→AcbSh glutamatergic pathway mediates expression of extinction.

The LH is an important target of AcbSh projections during the expression of extinction of drug seeking. As reviewed in Sect. 4.1.1.1, pharmacological inhibition of AcbSh increases feeding in an LH-dependent manner (see [138] for review). Recently, Millan et al. [78] reported a similar effect in a drug-seeking paradigm. The expression of extinction of alcoholic beer seeking was abolished when AcbSh was inactivated. Furthermore, this reinstatement was associated with an increase in c-Fos expression in hypothalamic neurons, including LH orexin neurons. In a final experiment, Millan et al. [78] demonstrated that functional inactivation of LH blocks AcbSh-inactivation-induced reinstatement. This evidence is consistent with other evidence demonstrating that the expression of extinction is associated specifically with recruitment of a direct dorsomedial (Dm) AcbSh→LH pathway [53]. Thus, increased activation of an AcbShDm→LH pathway is associated with the expression of extinction of alcoholic beer seeking.

The results of Marchant et al. [53] indicate that an AcbShV→LH pathway is recruited during reinstatement of drug seeking, whereas an AcbShDm→LH pathway is recruited during extinction expression. Therefore, there are anatomically distinct populations of LH projecting AcbSh neurons (i.e. dorsomedial or ventral) that are differentially recruited during test for either reinstatement (AcbShV) or extinction (AcbShDm). There is anatomical evidence that these subregions of AcbSh sit within different circuits. For example, AcbShDm only receives cortical input from IL [77], whereas AcbShV receives projections from PL and IL [80]. Whilst IL also projects to AcbShV, there is some evidence that single IL neurons do not project to both AcbShV and AcbShDm. Injections of different retrograde tracers into AcbShDm and AcbShV in the same rat reveals retrograde labelled neurons in IL, but very few neurons are double labelled (Fig. 1d of Ref. [77]). Thus, it is possible that distinct populations of IL neurons project to either AcbShDm or AcbShV, placing them in different sub-circuits. Furthermore, while AcbShV projects to VTA, AcbShDm to VTA projections are sparse [77].

In summary, there is evidence for parallel, but anatomically and functionally distinct AcbSh→LH pathways controlling expression of reinstatement (AcbShV→LH) and extinction (AcbShDm→LH) that may be controlled by distinct populations of IL neurons. These findings identify LH as an important point of convergence between the neural circuits that initiate drug seeking to promote relapse and the neural circuits that inhibit drug seeking to promote abstinence. Understanding the nature of any interactions that occur in LH between these two circuits remains an important area for future investigation.

Cortical→hypothalamic→thalamic

Recent evidence suggests that expression of extinction is associated with activation of a direct cortical→hypothalamic pathway. Marchant et al. [63] demonstrated that IL neurons projecting to MDH are recruited during the expression of extinction of alcoholic beer seeking. To the best of our knowledge this is the first evidence for activation in a specific cortical-hypothalamic pathway (i.e. IL→MDH) that is recruited during extinction expression. Marchant et al. [63] further demonstrated evidence for an efferent pathway from MDH that is active during extinction expression, identifying increased activation in both DMH and PeF neurons (i.e. MDH) that project to PVT specifically in rats tested for extinction. In both cases, increased activation in these pathways was seen in rats tested for extinction compared to those tested with reinstatement. Thus, increased activity in these pathways is selectively associated with reduced behavioural output in this paradigm.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that extinction expression is associated with recruitment of both IL→MDH and MDH→PVT pathways. It is tempting to predict that there is a direct IL→MDH→PVT pathway mediating extinction expression; however, in the absence of transynaptic tracing (e.g., [139]), it is not possible to determine whether the same MDH neurons receive IL inputs and project to PVT during extinction expression, resulting in a direct IL→MDH→PVT extinction pathway, or whether separate MDH neurons contribute to these pathways.

In a final set of experiments, Marchant et al. [63] provided indirect evidence that the MDH→PVT pathway is causally important for extinction expression. Using triple-label immunofluorescence, they demonstrated that over half of the MDH→PVT ‘extinction’ neurons expressed the opioid pro-peptide prodynorphin. Prodynorphin is the precursor to the opioid peptide dynorphin, a kappa opioid receptor (κOR) preferring ligand [140]. Expression of κOR mRNA is high in PVT [141, 142], as such Marchant et al. [63] tested whether κOR signalling in PVT is sufficient to induce extinction and so inhibit reinstatement of alcoholic beer seeking. They found that intra-PVT infusion of the κOR agonist U50488 significantly attenuated context-induced reinstatement. Because κOR activation leads to hyperpolarisation of the post-synaptic neuron via Gi/o signalling [140], this manipulation likely blocked reinstatement by inhibition of PVT neurons. Consistent with this, excitotoxic lesions of PVT block context-induced reinstatement [107]. Furthermore, intra-PVT infusion of CART, which is expected to be inhibitory [31], also blocks cocaine-primed reinstatement of extinguished cocaine seeking [143].

These findings support the conclusion that extinction expression may be mediated by pathways that exert inhibitory control over PVT, and that one such pathway is the MDH→PVT dynorphin pathway. It is worth noting that these studies suggest that cortical→striatal→hypothalamic and cortical→hypothalamic→thalamic pathways are recruited as a consequence of extinction training to actively inhibit drug seeking, but are not necessarily recruited during extinction learning. For example, in many of the studies reviewed here, manipulations that prevented the expression of extinction of drug seeking had no effect on the initial learning of extinction. Such dissociation in the brain mechanisms for the acquisition versus expression of learning is relatively common and suggests that distinct neural circuits are important for acquiring new learning versus using that learning to influence behaviour.

Summary

The past 15 years has seen a renewed interest in the role of the hypothalamus in appetitively motivated behaviour. Elegant molecular studies have identified the hypothalamic neuropeptides, cell signaling mechanisms and intra-hypothalamic pathways critical for the control of feeding. More recently, this has been extended to studies of the brain mechanisms of drug seeking. We have argued here that the hypothalamus is an important part of the neural circuitry that promotes as well as inhibits drug seeking. It sits as a key node in a corticostriatal-hypothalamic thalamic loop important for the control of appetitive motivation and initiation of drug seeking, and as a key node in a cortical-hypothalamic-thalamic loop for the inhibition of drug seeking. The actions of hypothalamic-derived neuropeptides such as orexin and dynorphin are essential to modulating activity in these loops and hence in promoting versus inhibiting drug seeking.

There is extensive evidence that LH is important for appetitive behaviours, encompassing feeding, drug reward and reinstatement of drug seeking induced by associated stimuli. The common element in these studies is that LH is important for promoting approach behaviour directed towards a reward. The function of LH therefore may be to generate the motivation necessary for reward seeking, rather than specific behavioural responses required to obtain the goal. The demonstration that hypothalamic orexigenic mechanisms mediate reinstatement of drug seeking provides a rationale for expecting that antagonism of orexigenic processes would inhibit drug seeking. As was reviewed above, there is evidence to support this claim. Thus, the continued activation of a cortical-striatal-hypothalamic-thalamic-cortical “loop” is important for initiating and maintaining drug seeking during reinstatement. The corollary of this finding is that endogenous neural substrates mediating anorexigenic functions can also inhibit drug and reward seeking. Whilst the evidence supporting this claim is less comprehensive, we have reviewed the emerging evidence that some endogenous anorexigenic structures mediate the inhibition of drug seeking observed during an extinction test. In particular, we propose that MDH may be important for inhibiting the motivation necessary for drug seeking, particularly during the expression of extinction of drug seeking.

Integration of the behavioural, neural circuitry, pharmacological and molecular data reviewed here supports our proposal that medial and lateral regions of the dorsal tuberal hypothalamus exert opposing effects on drug seeking. The lateral region of the dorsal tuberal hypothalamus promotes drug seeking, whereas the medial region of the dorsal tuberal hypothalamus inhibits drug seeking. This proposal is reminiscent of the dual-center theory of feeding [4]. Interestingly a similar dissociation of functions has been demonstrated in the context of aggressive behaviours. Specifically, ‘defensive rage’, withdrawal behaviour, is mediated by MDH, while ‘predatory attack’, approach behaviour, is mediated by LH [144]. Ultimately, a more parsimonious explanation of the function of the dorsal tuberal hypothalamus in motivated behaviour may be that the medial and lateral regions of the dorsal tuberal hypothalamus promote approach to (lateral) versus withdrawal from (medial) biologically significant events.

Acknowledgments

The preparation of this manuscript was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (510199; 630406). GPM is an Australian Research Council QEII Fellow (DP0877430).

Contributor Information

Nathan J. Marchant, Email: nathan.marchant@nih.gov

Gavan P. McNally, Email: g.mcnally@unsw.edu.au

References

- 1.Swanson LW. Cerebral hemisphere regulation of motivated behavior. Brain Res. 2000;886(1–2):113–164. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)02905-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simerly RB. Anatomical substrates of hypothalamic integration. In: George P, editor. The rat nervous system. 3. Burlington: Academic Press; 2004. pp. 335–368. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olds J, Milner P. Positive reinforcement produced by electrical stimulation of septal area and other regions of rat brain. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1954;47(6):419–427. doi: 10.1037/h0058775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stellar E. The physiology of motivation. Psychol Rev. 1954;61(1):5–22. doi: 10.1037/h0060347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elmquist JK, Elias CF, Saper CB. From lesions to leptin: hypothalamic control of food intake and body weight. Neuron. 1999;22(2):221–232. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiLeone RJ, Georgescu D, Nestler EJ. Lateral hypothalamic neuropeptides in reward and drug addiction. Life Sci. 2003;73(6):759–768. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(03)00408-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anand BK, Brobeck JR. Hypothalamic Control of Food Intake in Rats and Cats. Yale J Biol Med. 1951;24(2):123–140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olds J, Travis RP, Schwing RC. Topographic organization of hypothalamic self-stimulation functions. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1960;53:23–32. doi: 10.1037/h0039776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Margules DL, Olds J. Identical “feeding” and “rewarding” systems in the lateral hypothalamus of rats. Science. 1962;135(3501):374–375. doi: 10.1126/science.135.3501.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoebel BG, Teitelbaum P. Hypothalamic control of feeding and self-stimulation. Science. 1962;135(3501):375–377. doi: 10.1126/science.135.3501.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valenstein ES, Cox VC, Kakolewski JW. Reexamination of the role of the hypothalamus in motivation. Psychol Rev. 1970;77(1):16–31. doi: 10.1037/h0028581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wise RA. Lateral hypothalamic electrical stimulation: does it make animals ‘hungry’? Brain Res. 1974;67(2):187–209. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porrino LJ, Coons EE, MacGregor B. Two types of medial hypothalamic inhibition of lateral hypothalamic reward. Brain Res. 1983;277(2):269–282. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90934-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stanley BG, Willett VL, 3rd, Donias HW, Dee MG, 2nd, Duva MA. Lateral hypothalamic NMDA receptors and glutamate as physiological mediators of eating and weight control. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1996;270(2):R443–R449. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.2.R443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grossman SP, Grossman L. Iontophoretic injections of kainic acid into the rat lateral hypothalamus: Effects on ingestive behavior. Physiol Behav. 1982;29(3):553–559. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(82)90281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stricker EM, Swerdloff AF, Zigmond MJ. Intrahypothalamic injections of kainic acid produce feeding and drinking deficits in rats. Brain Res. 1978;158(2):470–473. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90692-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elmquist JK, Bjorbaek C, Ahima RS, Flier JS, Saper CB. Distributions of leptin receptor mRNA isoforms in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1998;395(4):535–547. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19980615)395:4<535::AID-CNE9>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bjørbæk C, Elmquist JK, Frantz JD, Shoelson SE, Flier JS. Identification of SOCS-3 as a potential mediator of central leptin resistance. Mol Cell. 1998;1(4):619–625. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faouzi M, Leshan R, Bjornholm M, Hennessey T, Jones J, Munzberg H. Differential accessibility of circulating leptin to individual hypothalamic sites. Endocrinology. 2007;148(11):5414–5423. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kristensen P, Judge ME, Thim L, Ribel U, Christjansen KN, Wulff BS, Clausen JT, Jensen PB, Madsen OD, Vrang N, Larsen PJ, Hastrup S. Hypothalamic CART is a new anorectic peptide regulated by leptin. Nature. 1998;393(6680):72–76. doi: 10.1038/29993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elias CF, Lee C, Kelly J, Aschkenasi C, Ahima RS, Couceyro PR, Kuhar MJ, Saper CB, Elmquist JK. Leptin activates hypothalamic cart neurons projecting to the spinal cord. Neuron. 1998;21(6):1375–1385. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80656-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elias CF, Saper CB, Maratos-Flier E, Tritos NA, Lee C, Kelly J, Tatro JB, Hoffman GE, Ollmann MM, Barsh GS, Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Elmquist JK. Chemically defined projections linking the mediobasal hypothalamus and the lateral hypothalamic area. J Comp Neurol. 1998;402(4):442–459. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19981228)402:4<442::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broberger C, Lecea LD, Sutcliffe JG, Hökfelt T. Hypocretin/Orexin- and melanin-concentrating hormone-expressing cells form distinct populations in the rodent lateral hypothalamus: relationship to the neuropeptide Y and agouti gene-related protein systems. J Comp Neurol. 1998;402(4):460–474. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19981228)402:4<460::AID-CNE3>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sawchenko PE. Toward a new neurobiology of energy balance, appetite, and obesity: the anatomists weigh in. J Comp Neurol. 1998;402(4):435–441. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19981228)402:4<435::AID-CNE1>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.West DB, Fey D, Woods SC. Cholecystokinin persistently suppresses meal size but not food intake in free-feeding rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1984;246(5):R776–R787. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.246.5.R776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vrang N, Tang-Christensen M, Larsen PJ, Kristensen P. Recombinant CART peptide induces c-Fos expression in central areas involved in control of feeding behaviour. Brain Res. 1999;818(2):499–509. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)01349-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellinger LL, Bernardis LL. Suppression of feeding by cholecystokinin but not bombesin is attenuated in dorsomedial hypothalamic nuclei lesioned rats. Peptides. 1984;5(3):547–552. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(84)90085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen J, Scott KA, Zhao Z, Moran TH, Bi S. Characterization of the feeding inhibition and neural activation produced by dorsomedial hypothalamic cholecystokinin administration. Neuroscience. 2008;152(1):178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobelt P, Paulitsch S, Goebel M, Stengel A, Schmidtmann M, van der Voort IR, Tebbe JJ, Veh RW, Klapp BF, Wiedenmann B, Tache Y, Monnikes H. Peripheral injection of CCK-8S induces Fos expression in the dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus in rats. Brain Res. 2006;1117(1):109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abbott CR, Rossi M, Wren AM, Murphy KG, Kennedy AR, Stanley SA, Zollner AN, Morgan DG, Morgan I, Ghatei MA, Small CJ, Bloom SR. Evidence of an orexigenic role for cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript after administration into discrete hypothalamic nuclei. Endocrinology. 2001;142(8):3457–3463. doi: 10.1210/en.142.8.3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rogge G, Jones D, Hubert GW, Lin Y, Kuhar MJ. CART peptides: regulators of body weight, reward and other functions. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(10):747–758. doi: 10.1038/nrn2493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Will MJ, Franzblau EB, Kelley AE. Nucleus accumbens mu-opioids regulate intake of a high-fat diet via activation of a distributed brain network. J Neurosci. 2003;23(7):2882–2888. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02882.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Kozlowski GP, Wilson S, Arch JRS, Buckingham RE, Haynes AC, Carr SA, Annan RS, McNulty DE, Liu W-S, Terrett JA, Elshourbagy NA, Bergsma DJ, Yanagisawa M. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and g protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92(4):573–585. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X, Foye PE, Danielson PE, Fukuhara C, Battenberg EL, Gautvik VT, Bartlett FS, 2nd, Frankel WN, van den Pol AN, Bloom FE, Gautvik KM, Sutcliffe JG. The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(1):322–327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bittencourt JC, Presse F, Arias C, Peto C, Vaughan J, Nahon J-L, Vale W, Sawchenko PE. The melanin-concentrating hormone system of the rat brain: an immuno and hybridization histochemical characterization. J Comp Neurol. 1992;319(2):218–245. doi: 10.1002/cne.903190204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qu D, Ludwig DS, Gammeltoft S, Piper M, Pelleymounter MA, Cullen MJ, Mathes WF, Przypek R, Kanarek R, Maratos-Flier E. A role for melanin-concentrating hormone in the central regulation of feeding behaviour. Nature. 1996;380(6571):243–247. doi: 10.1038/380243a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saper CB, Scammell TE, Lu J. Hypothalamic regulation of sleep and circadian rhythms. Nature. 2005;437(7063):1257–1263. doi: 10.1038/nature04284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thannickal TC, Moore RY, Nienhuis R, Ramanathan L, Gulyani S, Aldrich M, Cornford M, Siegel JM. Reduced number of hypocretin neurons in human narcolepsy. Neuron. 2000;27(3):469–474. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00058-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin L, Faraco J, Li R, Kadotani H, Rogers W, Lin X, Qiu X, de Jong PJ, Nishino S, Mignot E. The sleep disorder canine narcolepsy is caused by a mutation in the hypocretin (orexin) receptor 2 gene. Cell. 1999;98(3):365–376. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81965-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chemelli RM, Willie JT, Sinton CM, Elmquist JK, Scammell T, Lee C, Richardson JA, Williams SC, Xiong Y, Kisanuki Y, Fitch TE, Nakazato M, Hammer RE, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M. Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: molecular genetics of sleep regulation. Cell. 1999;98(4):437–451. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81973-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Estabrooke IV, McCarthy MT, Ko E, Chou TC, Chemelli RM, Yanagisawa M, Saper CB, Scammell TE. Fos expression in orexin neurons varies with behavioral state. J Neurosci. 2001;21(5):1656–1662. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01656.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fadel J, Bubser M, Deutch AY. Differential activation of orexin neurons by antipsychotic drugs associated with weight gain. J Neurosci. 2002;22(15):6742–6746. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06742.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peyron C, Tighe DK, van den Pol AN, de Lecea L, Heller HC, Sutcliffe JG, Kilduff TS. Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J Neurosci. 1998;18(23):9996–10015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09996.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harris GC, Wimmer M, Aston-Jones G. A role for lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons in reward seeking. Nature. 2005;437(7058):556–559. doi: 10.1038/nature04071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bouton ME. Context, ambiguity, and unlearning: sources of relapse after behavioral extinction. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(10):976–986. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01546-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bouton ME. Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learn Mem. 2004;11(5):485–494. doi: 10.1101/lm.78804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rescorla RA. Experimental extinction. In: Mowrer RM, Klein SB, editors. Handbook of contemporary learning theories. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 119–154. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bouton ME, Westbrook RF, Corcoran KA, Maren S. Contextual and temporal modulation of extinction: behavioral and biological mechanisms. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(4):352–360. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dayas CV, McGranahan TM, Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F. Stimuli linked to ethanol availability activate hypothalamic CART and orexin neurons in a reinstatement model of relapse. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(2):152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hamlin AS, Blatchford KE, McNally GP. Renewal of an extinguished instrumental response: neural correlates and the role of D1 dopamine receptors. Neuroscience. 2006;143(1):25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hamlin AS, Newby J, McNally GP. The neural correlates and role of D1 dopamine receptors in renewal of extinguished alcohol-seeking. Neuroscience. 2007;146(2):525–536. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hamlin AS, Clemens KJ, McNally GP. Renewal of extinguished cocaine-seeking. Neuroscience. 2008;151(3):659–670. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marchant NJ, Hamlin AS, McNally GP. Lateral hypothalamus is required for context-induced reinstatement of extinguished reward seeking. J Neurosci. 2009;29(5):1331–1342. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5194-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lawrence AJ, Cowen MS, Yang H-J, Chen F, Oldfield B. The orexin system regulates alcohol-seeking in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148(6):752–759. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aston-Jones G, Smith RJ, Moorman DE, Richardson KA. Role of lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons in reward processing and addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Supplement 1):112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith RJ, Tahsili-Fahadan P, Aston-Jones G. Orexin/hypocretin is necessary for context-driven cocaine-seeking. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58(1):179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boutrel B, Kenny PJ, Specio SE, Martin-Fardon R, Markou A, Koob GF, de Lecea L. Role for hypocretin in mediating stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(52):19168–19173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507480102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Richards JK, Simms JA, Steensland P, Taha SA, Borgland SL, Bonci A, Bartlett SE. Inhibition of orexin-1/hypocretin-1 receptors inhibits yohimbine-induced reinstatement of ethanol and sucrose seeking in Long-Evans rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;199(1):109–117. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1136-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]