Abstract

Recent studies have shown that neural crest-derived progenitor cells can be found in diverse mammalian tissues including tissues that were not previously shown to contain neural crest derivatives, such as bone marrow. The identification of those "new" neural crest-derived progenitor cells opens new strategies for developing autologous cell replacement therapies in regenerative medicine. However, their potential use is still a challenge as only few neural crest-derived progenitor cells were found in those new accessible locations. In this study, we developed a protocol, based on wnt1 and BMP2 effects, to enrich neural crest-derived cells from adult bone marrow. Those two factors are known to maintain and stimulate the proliferation of embryonic neural crest stem cells, however, their effects have never been characterized on neural crest cells isolated from adult tissues. Using multiple strategies from microarray to 2D-DIGE proteomic analyses, we characterized those recruited neural crest-derived cells, defining their identity and their differentiating abilities.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00018-010-0558-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Neural crest, Bone marrow, wnt1, BMP2, Multipotent progenitors

Introduction

The neural crest cells (NCC) constitute a multipotent cell population arising, during embryonic development, from the lips of the neural plate at the closure of the neural tube and migrating throughout the embryo [1]. They participate in the development of a variety of tissues including the skeleton, pigment cells, the circulatory system, endocrine glands, and the peripheral nervous system [2]. At the onset of migration, NCC are an heterogeneous mixture of cell populations with extensive proliferative and developmental potential. Later, post-migratory NCC appear fate-restricted, highly committed, or unipotent. However, few long-term pluripotent progenitors derived from the embryonic NC persist in adulthood [3]. These rare cells have the capacity for both self-renewal and generation of multiple differentiated progeny in vitro and they are therefore bona fide stem cells. They persist in several NC-derived tissues in both embryo and postnatal animal and represent an enticing source of stem cells with potentials for therapeutic applications.

Self-renewing, multipotent neural crest stem cells (NCSC) were originally isolated by Stemple and Anderson [4] from pre-migratory neural crest. Multiple factors have been described that affect either self-renewal and/or multipotency of NCSC [5]. Among those factors, BMP2 has been characterized to promote neuronal autonomic development at the expense of glial cell fate [6]. Similarly, the acquisition of a glial phenotype is controlled by Neuregulin-1 [7] and Notch1 activation [8]. Moreover, it has been shown that BMP2 and wnt1 factors play an important role in the maintenance and proliferation of multipotent NCSC [9].

Recently, NCSC have been isolated from unexpected location, i.e., adult hair follicles [10], adult skin [11], and adult bone marrow [12]. These findings raised hope for new cell therapy applications in neurodegenerative disorders, based on the potential diversification of NCSC, their accessible locations, and their possible use in autologous grafts. However, only a few NCSC were found in those accessible locations making their potential use more challenging.

In this study, we analyzed the effect of BMP2 and wnt1 on NCSC enrichment from adult bone marrow cells. Cultivating those cells in the presence of wnt1 and BMP2, we observed a significantly increased number of nestin-positive cells (presumptive NCSC) after one passage. When placed in co-culture with cerebellar granule neurons (CGN), those cells showed a greater capacity to differentiate into Tuj1-positive cells compared to untreated cells. Clonal analyses confirmed the neural crest origin of these nestin/Sox10/p75NTR-positive cells as well as their ability to differentiate into adipocytes, osteocytes, melanocytes, smooth muscle, glia, and neurons. Interestingly, two types of neural crest-derived progenitors, gliogenic, and neurogenic, have been characterized. A proteomic comparison of those progenitors pointed to the differential expression of glycolytic enzymes as one major consequence of their preferential way of differentiation.

Materials and methods

Animal care

wnt1-Cre/R26R-LACZ double transgenic mice [13, 14] were used as positive control to confirm the neural crest origin of wnt1 and BMP2 selected cells. Transgenic GFP C57BL/6 mice (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove http://www.jacksonimmuno.com) were used for CGN cultures. Wild-type C57BL/6 mice (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were used for bone marrow stromal cell culture. Mice were bred at the University of Liège Central Animal facility and euthanized in accordance with the rules set by the local animal ethics committee as well as the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences.

Bone marrow stromal cell (BMSC) culture

Bone marrow from adult (8 to 15-week-old) mice was obtained from femoral and tibial bones by aspiration and was resuspended in 5 ml of MesenCult Medium (StemCells Technologies, http://www.stemcell.com/). After 24 h, non-adherent cells were removed. When the bone marrow stromal cells became confluent, they were resuspended using 0.05% trypsin–EDTA (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, http://www.invitrogen.com) and then sub-cultured (750,000 cells/5 ml).

Clonal selection

Bone marrow stromal cells were placed in a 96-well plate (Nunc) at a dilution of 0.7 cell/well, in MesenCult Medium (Stem Cells Technologies) supplemented with wnt1 (10 ng/ml, PeproTech, Rocky Hill, http://www.peprotech.com) and BMP2 (10 ng/ml, PeproTech). When cells reached confluency, they were dissociated with Trypsin–EDTA (0.05%) and sub-cultured at 150,000 cells/ml. The same protocol was applied to NCSC clone (from wnt1/R26R-LacZ transgenic mice) except that only MesenCult Medium was used without wnt1 and BMP2 supplement.

Preparation and culture of mouse cerebellar granule neurons

Mouse CGN cultures were prepared from 3-day-old green C57BL/6 mice (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), according to Lefebvre et al. [15]. Green mice express green fluorescent protein (GFP) under control of the β-actin promoter [16]. Briefly, cerebella were removed and freed of meninges. They were then minced into small fragments and incubated at 37°C for 25 min in 0.25% trypsin and 0.01% DNAse (w/v, in a cation-free solution). Fragments were then washed with minimum essential medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with glucose (final concentration 6 g 1−1), insulin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com; 5 μg ml−1) and pyruvate (Invitrogen; 1 mM). The potassium concentration was increased to 25 mM, while the sodium concentration was decreased in an equimolar amount (MEM-25HS). The dissociation was achieved mechanically by up-and-down aspirations in a 5-ml plastic pipette. The resulting cell suspension was then filtered on a 15-μm nylon sieve. Cells were then counted and diluted to a final concentration of 2.5 × 106 ml−1. The cell suspension was plated on a substrate previously coated with polyornithine (0.1 mg ml−1). The cells were cultured for 24 h before any other experimental procedure was performed.

Preparation of NSC

C57BL/6 mice embryos (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratory) were used as a source of NSC. The day of conception was determined by the presence of a vaginal plug (embryonic day 0). E16 striata were isolated and triturated in DEM/F12 (Invitrogen) with a sterile Pasteur pipette. The cell suspension was filtered with a 70-μM-pore filter and viable cells were estimated by trypan blue exclusion. The cells were plated (1 × 106 cells/75-cm2 tissue culture flask) in DEM/F12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with epidermal growth factor (EGF, 20 ng ml−1, Sigma), B27 (Invitrogen). When the size of neurosphere reached approximately 50 cells, they were dissociated to a single cell suspension by trituration and replated in fresh culture medium.

Immunocytofluorescence

Briefly, cell cultures were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, then blocked with 10% normal donkey serum (NDS) and/or 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 45 min. Anti-Sox10 (1:200; ABR), anti-nestin (1:300; Novus Biological), anti-GFAP (1:1,000; Chemicon), anti-Tuj1 (1:1,000; Covance), anti-SMA (1:400; Sigma) and anti-p75LNTR (1:100; Chemicon) were used for 2 h at RT. FITC- or rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) were incubated for 1 h at RT and finally counterstained with Vectashield HardSet Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, http://www.vectorlabs.com). Preparations were observed using an Olympus laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, http://www.olympus-global.com). The fraction of positive cells was determined by counting ten non-overlapping microscopic fields for each coverslip (with a minimum of three coverslips per experiments) in at least three separate experiments (n represent the number of independent experiments).

Functional characterization

Several protocols have been used to analyze the differentiation abilities of bone marrow NCC into smooth muscle cells, adipocytes, osteocyte, and melanocytes. Smooth muscle differentiation: cells were incubated in DMEM/F12 supplemented with B-27 (Invitrogen), 5% chicken embryo extract and TGF-β (1 nM, PeproTech). Adipogenic differentiation: differentiation was induced by treatment with Mesencult medium containing 1-methyl-3-isobutylxanthine (0.5 mM, Sigma), dexamethasone (1 μM, Sigma), bovine insulin (0.01 mg ml−1), indomethacin (0.2 mM, Sigma). Cells were placed in the above adipocyte induction medium for 21 days. The differentiation was evaluated by accumulation of lipid vacuoles and staining with Oil Red O (Sigma) following fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde. Melanocyte formation was obtained after 10 days in MEM containing 10% FBS, 50 ng ml−1 murine stem cell factor (mSCF, PeproTech) and 100 nM endothelin-3 (Sigma). Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and were incubated for 5 h at 37°C in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% 3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-l-alanine (l-Dopa) (Sigma). For osteogenic induction, cells were cultivated in StemXVivo Osteogenic media (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, http://www.rndsystems.com). Osteogenic differentiation was measured using p-nitrophenyl phosphate, a substrate for alkaline phosphatase (Sigma). Level of alkaline phosphatase activity was detected by development of soluble yellow reaction product that can be measured at 405 nm using Thermo Labsystems Multiskan Ascent 354 spectrophotometer (Lab Recyclers, Gaithersburg, http://www.labrecyclers.com).

RNA extraction, RT-PCR, and quantitative RT-PCR analyses

Total RNA was prepared using the RNeasy total RNA purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, http://www.qiagen.com). cDNA synthesis was carried out using Moloney-murine leukemia virus (MMLV) Reverse transcriptase (Promega) and random hexamer primers (Promega), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCR was carried out using standard protocols with Quantitec SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen). The PCR mix contained SYBR Green Mix, 0.5 μM primers (Table 1), 1 ng DNA template and nuclease-free water to final volumes of 25 μl. PCR were performed on a RotorGene RG-3000 instrument (Corbett-Qiagen) and analyzed with Rotorgene Software (Corbett-Qiagen). The percentage of gene expression by clones was normalized as a function of GAPDH gene expression and compared to the gene expression value of clone 4 that was considered as 100%. Each gene analysis was realized on three different samples with two runs/sample (providing six PCR analyses per target gene).

Table 1.

Quantitative RT-PCR primers

| Gene name | Forward | Reverse | T m |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oct4 | CCAATCAGCTTGGGCTAGAG | CCTGGGAAAGGTGTCCTGTA | 58 |

| Nanog | GAGTGTGGGTCTTCCTGGTC | GAGGCAGGTCTTCAGAGGAA | 54 |

| Rex1 | CCTGCACACAGAAGAAAGCA | TCAGTCTGTCGAGGGCTCTT | 52 |

| P75NTR | GCATTGTGGTAGGCCAGACC | CCTGAAAGTCACTCCATCCC | 54 |

| CXCR4 | GCCATGGCTGACTGGTACTT | TGGAGTGTGACAGCTTGGAG | 51 |

| ID2 | CTCCAAGCTCAAGGAACTGG | ATGCTGATGTCCGTGTTCAG | 56 |

| Wnt1 | GTGCCCCCTCTCCCCGTGACCTCTC | GGCTGAAACCCCCGGCACAATAAAT | 61 |

| Mash1 | GGCTCAACTTCAGTGGCTTC | TCGGAGGAGTAGGACGAAAC | 52 |

| Snail1 | GAGGACAGTGGCAAAAGCTC | AGGACATTCGGGAGAAGGTT | 56 |

| Twist1 | ACGACAGCCTGAGCAACAG | GCAGGACCTGGTACAGGAAG | 55 |

| Notch1 | TTACAGCCACCATCACAGCCACACC | TGCCCTCGGACCAATCAGA | 58 |

| MSI1 | CGAGCTCGACTCCAAAACAAT | AGCTTTCTTGCATTCCACCA | 55 |

| Pax3 | GCCAATCAACTGATGGCTTT | CATTCGAAGGAATGGTGCTT | 53 |

| Pax6 | AGTTCTTCGCAACCTGGCTA | GGAGCTGATGGAGTTGGTGT | 54 |

| Sox1 | AACCCCAAGATGCACAACTC | TAGCCCAGCCGTTGACAT | 54 |

| Nestin | GGATACAGCTTTATTCAAGG | CAGCCGCTGAAGTTCACTCT | 54 |

| Hes1 | CTACCCCAGCCAGTGTCAAC | AAGCGGGTCACCTCGTTCAT | 55 |

| NeuroD2 | GCAAGGTGGTGCCCTGCTACTC | GCGACAGACCCTTGCACAGAGTC | 58 |

| Sox2 | TAGCACTTGTTGCCAGAACG | AAGCCGCTCTTCTCTTTTCC | 54 |

Microarray analysis

The RNA quality was assessed by the Experion automated electrophoresis system using the RNA StdSens Analysis Kit (Bio-Rad, Nazareth, http://www.Bio-Rad.com). Four micrograms of total RNA were labeled using the GeneChip Expression 3′-Amplification One-Cycle Target Labeling Kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, http://www.affymetrix.com) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The cRNA was hybridized to Mouse Genome Expression set 430 2.0 GeneChip (Affymetrix) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, double-stranded cDNA was synthesized from 4 μg of total RNA primed with a poly-(dT)-T7 oligonucleotide. The cDNA was used in an in vitro transcription reaction in the presence of T7 RNA polymerase and biotin-labeled modified nucleotides 16 h at 37°C. Biotinylated cRNA was purified and then fragmented (35–200 nucleotides) together with hybridization controls and hybridized to the microarrays for 16 h at 45°C. Using Fluidics Station (Affymetrix), the hybridized biotin-labeled cRNA was revealed by successive reactions with streptavidin R-phycoerythrin conjugate, biotinylated anti-streptavidin antibody, and streptavidin R-phycoerythrin conjugate. The arrays were finally scanned with an Affymetrix/Hewlett-Packard GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G. The data were generated with the MAS 5.0 algorithm included GeneChip Operating Software (GCOS). Values obtained for PBS treatment condition have been considered as baseline for pair-wise comparison with OVA-induced experimental conditions. The probe sets have been filtered on signal log ratio (>0.6 for up-regulated and < –0.6 for down-regulated transcripts) and on p value associated with the change status 0.001 for up-regulated probe sets, >0.999 for down-regulated probe sets). Lists of differentially expressed genes obtained from clone 1, clone 4, and NCSC clone form adult bone marrow are shown in Supplementary Data Table S1–S3. To determine which pathways were significantly regulated, lists of differentially expressed (up- and downregulated) genes were uploaded in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (IPA 6.0; Ingenuity Systems; http://www.ingenuity.com).

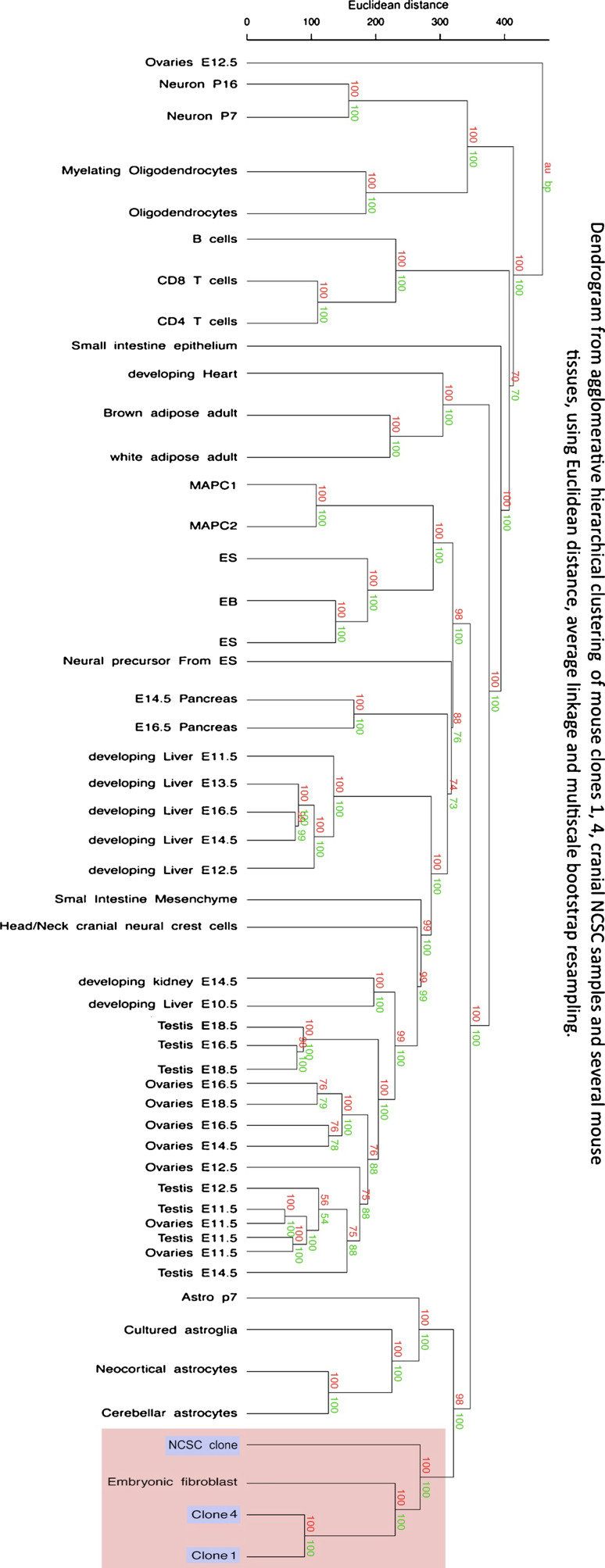

Dendrogram

Expression array data of clone 1, clone 4 and NCSC clone were used in an unsupervised analysis comparing them with several expression array data available from the Gene Expression Omnibus database http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/. All samples from GEO datasets have been processed on Affymetrix Mouse Genome Expression Set 430 GeneChips. Normalization and data filtering were performed using BRB-Array Tools software version 3.8.1 developed by Dr. Richard Simons and the BRB-Array Tools Development Team; http://linus.nci.nih.gov./BRB-ArrayTools.html. We used the GCRMA algorithm as normalization step. Quartiles of each expression arrays were compared in a box-plot view. Medians, first, and third quartiles were similar in each case (data not shown). This similarity allowed the comparison of the 118 arrays in the same analysis process. Background noise has been removed with the “Log Intensity variation” function of “BRB-Array Tools” at a p value > 0.05. The package “pvclust” from R-cran (Team, R. D. C., R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, 2009) was used on the remaining filtered genes to build and test the architecture of each cluster of samples. “pvclust” is used for assessing the uncertainty in hierarchical cluster analysis. For each cluster in hierarchical clustering, p values are calculated via multiscale bootstrap resampling. This indicates how strong the cluster is supported by data. “pvclust” provides two types of p values: AU (Approximately Unbiased) p value in red and BP (Bootstrap Probability) value in green. AU p value, which is computed by multiscale bootstrap resampling, is a better approximation to unbiased p value than BP value computed by normal bootstrap resampling. We choose the most commonly used “Euclidean distance” as dissimilarity metric and three different methods of linkage (single, complete, average) to obtain dendrogram structures. The relevance of dendrogram architecture was then tested by data permutations. We set the multiscale bootstrap resampling argument of “pvclust” at 1,000 permutations of genes to test those dendrograms. Only the “average linkage” method showed the best stable structure (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Dendrogram generated after agglomerative hierarchical clustering using Euclidean distance, average linkage and multiscale bootstrap resampling. 118 expression array data sets were included in an unsupervised analysis with hierarchical clustering of samples. All replicates were merged under the same denomination when possible. The dendrogram was build with the Euclidean distance as dissimilarity metric and the average linkage method for definition of the structure. Values on the edges of the clustering are p values (%). Red values are AU p values, and green values are BP values. AU (Approximately Unbiased) p values were computed by multiscale bootstrap resampling. BP (Bootstrap Probability) values were computed by normal bootstrap resampling. R-cran “pvclust” package was used for assessing the uncertainty of this hierarchical cluster analysis for 1,000 permutations of genes. Those values indicated how strongly the cluster was supported by the data and consequently strongly confirmed the same embryonic origin of clone 1, clone 4 and NCSC clone isolated from Wnt1-CRE/R26R double transgenic mice

Western blotting

Proteins were extracted from clone 1 and 4. Cells were harvested in 1% SDS supplemented with phosphatase inhibitors 1:20 (ActiveMotif, Rixensart Belgium) and Complete proteases inhibitors cocktail (Roche, Brussels, Belgium). Protein concentrations were quantified by the RC/DC Protein Assay (Bio-Rad) based on classical Lowry method. Equivalent amounts of extracted proteins were separated by electrophoresis on a 10% polyacrylamide gel (Nupage, Invitrogen) at 200 V and transferred to PVDF membrane (Roche) using NuPage transfer buffer. After blocking in 0.1% purified casein (Tropix, Bedford, MA, USA) for 1 h, the membrane was incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C and then with a secondary antibody conjugated with peroxidase for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactive signals were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (SuperSignal WestPico, Pierce, Brussels, Belgium). Primary antibodies used were: rabbit anti-aldolase (1/1,000, cell signaling), mouse anti-beta-actin (1/2,500, Sigma), goat anti-PGAM1/4 (1/200, Santa Cruz), goat anti-LDH-A (1/200, Santa Cruz), goat anti-pyruvate kinase (1/1,000, Chemicon), goat anti-TIM (1/1,000, Santa Cruz), goat anti-PGK1 (1/1,000, Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-G6PDH (1/500, Abcam). Bound primary antibody was detected using HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (raised in mouse, rabbit, or goat, 1/3,000, Sigma).

2D-DIGE analyses and mass spectrometry

Clone 1 and 4 proteins were extracted in a lysis buffer containing 7 M urea (GE Healthcare), 2 M thiourea (GE Healthcare), 30 mM Tris, pH 8.5 (GE Healthcare) and 2% ASB14 (Sigma). The supernatant containing the extracted proteins was precipitated (2D Clean-Up Kit, GE Healthcare) and protein amounts were determined using RC/DC Protein Assay (Bio-Rad). Each 25 μg of sample protein was labeled with 200 pMol of CyDyes (GE Healthcare), either Cy3 or Cy5 and left for 30 min in the dark. The labeling reaction was stopped by adding 10 mM lysine for 10 min at 4°C. The internal standard was prepared by mixing equal quantities of all the experimental samples and was labeled with Cy2. Then all the samples within the experiment were mixed in pairs together with 25 μg of the internal standard and were separated by isoelectric focusing using pH 3–11 (24 cm) IPG strips and Ettan IPGphor focusing system (GE Healthcare) in the first dimension. The following electrophoresis steps were successively applied: 8 h of rehydration, 1 h at 500 V, 1 h at 1,000 V (gradient), 3 h at 8,000 V (gradient), and 8 h 45 min at 8,000 V (step-and-hold). Before initiating the second dimension step, proteins in IPG strips were reduced for 15 min in an equilibration buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.8, 6 M urea, 30% glycerol, 2% SDS) containing 1% DTT and then were alkylated in the same equilibration buffer containing 5% iodoacetamide. IPG strips were placed on top of classical 12.5% SDS-PAGE gel and the electrophoretic migration was conducted in an Ettan Dalt apparatus (GE Healthcare) at 2.5 W/gel for 30 min and then 25 W for 4 h. After scanning the gels with a Typhoon 9400 Laser Scanner (GE Healthcare) at three different wavelengths corresponding to the different CyDyes, 2D gel analysis software (DeCyder version 6.5, GE Healthcare) was used for spot detection, gel matching, and spot quantification relative to the corresponding spot in the internal standard. Protein spots that showed a significant variation in their abundance of at least 1.5-fold (Student t test, p < 0.05) by BVA (Biological Variation Analysis) were automatically picked from the gels with the Ettan Spot Picker (GE Healthcare) and subjected to automatic tryptic digestion (PROTEINEER dp automated digester, Bruker Daltonics, Germany). Gel pieces were washed three times in 50 mM NH4HCO3 followed by 50% ACN/50 mM NH4HCO3. Two other washes were carried out with 100% ACN to dehydrate the gels. In-gel digestion was performed with freshly activated trypsin (recombinant porcine trypsin, proteomics grade, Roche) at a concentration of 10 ng l−1 in 50 mM NH4HCO3/5% ACN. After rehydration of the gel pieces at 8°C for 60 min, tryptic digestion was carried out at 30°C for 4 h. The resulting digested peptides were extracted with 1% TFA for 30 min at 20°C with occasional shaking. A volume of 3 μl of protein digest was adsorbed for 3 min on Prespotted AnchorChip plates with CHCA as a matrix using the PROTEINEER dp automat. Then the spots were briefly desalted with 10 mM dihydrogenoammonium phosphate in 0.1% TFA. MS fingerprints of the samples were acquired using the Ultraflex II MALDI-TOF-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics) in the mass range: 700–3,500 Da). The PMFs were searched against the NCBI database. The variable and fixed modifications were methionine oxidation and cysteine carbamylation, respectively, with a maximum number of missed cleavages of 1. Mass precision tolerance error was set to 100 ppm. Peaks with the highest intensities, obtained in TOF/MS mode, were next analyzed by LIFT MS/MS. Proteins were identified with the Biotools 3.0 software (Bruker) using the Mascot (Matrix Science) search engine (www.matrixscience.com).

Results

We previously demonstrated that nestin-positive mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) isolated from adult bone marrow were able to differentiate into excitable neurons, when co-cultured with mouse CG neurons [17]. We also demonstrated that Sox10 transcription factors, as well as Frizzled (wnt receptor), were up-regulated in nestin-positive MSC compared with nestin-negative MSC, suggesting a possible role for these genes in the acquisition of a responsiveness to neural fate-inducing signals in a nestin-positive MSC population. Noteworthy, only nestin-positive bone marrow cells, which are also Sox10 and p75NTR-positive [17], were able to differentiate into functional neural cells. Knowing that neural crest-derived cells (NCC) can be isolated from adult bone marrow, it has been suggested that nestin/Sox10/p75NTR-positive bone marrow cells could be NCC.

wnt1 and BMP2 effect on nestin/Sox10/p75NTR-positive cell proliferation

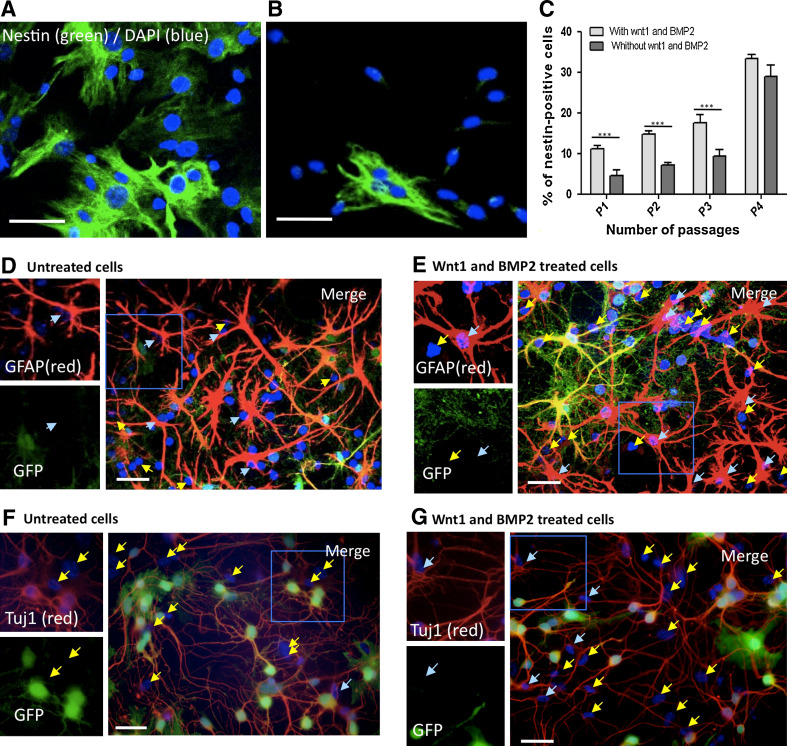

As wnt1 and BMP2 have been described as two factors supporting neural crest stem cell (NCSC) proliferation and maintenance [18], we analyzed the effect of those factors on bone marrow stromal cell cultures. Given the fact that there is no specific NCSC marker and according to our previous results, we first used nestin expression to follow potential NCSC from adult bone marrow. We cultivated bone marrow stromal cells (from passage 0) in the presence of wnt1 and BMP2 and analyzed the impact of those factors on nestin-positive cell population. Interestingly, the number of nestin-positive cells was significantly increased after 1 passage (Fig. 1a–c) compared to control condition (absence of wnt1 and BMP2 in culture medium). Wnt1 and BMP2 effect was significant for the first three passages then dropped after passage 4. We co-cultivated those wnt1- and BMP2-treated cells with CG neurons (as previously described [17]) and evaluated their ability to differentiate into neurons or glia as compared with untreated cells. Interestingly, the number of GFAP-positive cells remained unchanged in both conditions (about 40% GFAP-positive cells, Fig. 1d untreated cells, Fig. 1e wnt1- and BMP2-treated cells), however, we did observe a drastic effect on the number of Tuj1-positive cells as only few Tuj1-positive cells were observed in absence of factors (less than 1%, Fig. 1f), while around 10% Tuj1-positive cells were observed in presence of wnt1 and BMP2 (Fig. 1g).

Fig. 1.

BMP2 and Wnt1 increase the number of nestin-positive cells in cultured adult bone marrow cells. a–c Immunofluorescent labeling for nestin (green) and dapi (blue) of passage 1 Wnt1- and BMP2-stimulated cells (a) and untreated cells (b). c Comparison of the percentage of nestin-positive cells in presence or absence of Wnt1 and Bmp2. Stromal cells isolated from bone marrow have been cultivated in the presence of 10 ng/ml Wnt1 and BMP2 factors. After 1 passage, the number of nestin-positive cells significantly increased compared to the control condition (without Wnt1 and BMP2). Student’s t test, p < 0.0001, n = 3. This effect disappeared after four passages, as no significant differences could then be observed. Student’s t test, p > 0.05, n = 3. d–g Stimulated and unstimulated cells were co-cultured for 5 days with GFP-positive CGN (green). GFAP (red) was equally expressed under both conditions (d untreated; e treated), while Tuj1-positive cells (red) could only be observed in Wnt1 and BMP2 treated cells (f untreated; g treated). Absence of GFP expression confirmed the bone marrow origin of some Tuj1-expressing cells in g. Nuclei were counterstained with Dapi (blue). Blue arrows show neural expression markers by presumptive neural crest-derived cells (Tuj1- or GFAP-positive, but GFP-negative cells), while yellow arrows show undifferentiated stromal cells (Tuj1- or GFAP-, and GFP-negative). Scale bars 30 μM. Significant differences are indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001

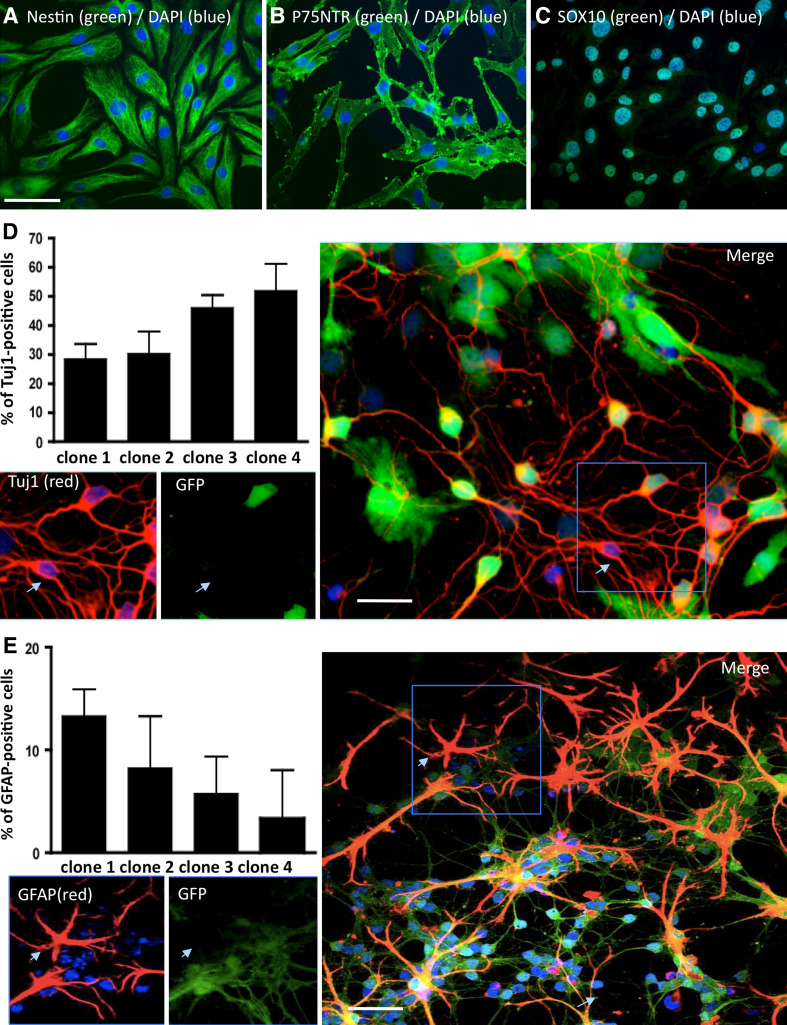

Clonal analyses of presumptive bone marrow NCSC

As nestin-positive cells (presumptive NCSC) were still a minority population (up to 30% at passage 4, even when cells were treated with BMP2 and wnt1, Fig. 1c) of adult bone marrow stromal cells, we could not perform any accurate characterization. We thus proceeded to clonal analyses to better characterize those wnt1/BMP2-treated cells. When 0.7 bone marrow stromal cell were seeded per well, in 96-well plates, 1.2% of cells were able to proliferate in growth medium supplemented with wnt1 and BMP2. Obtained clones were all nestin- (Fig. 2a), p75NTR- (Fig. 2b) and Sox10-positive cells (Fig. 2c), indicating that these clones grown in presence of wnt1 and BMP2 could be neural crest-derived cells. Selecting four clones, we analyzed their abilities to differentiate into glial and neuronal cells when maintained in co-culture with CGN. Interestingly, all clones were able to differentiate into neuronal cells (Tuj1-positive cells, Fig. 2d) and glial cells (GFAP-positive cells, Fig. 2e), however the percentages of differentiation were repeatedly different from one clone to another as some clones were more gliogenic and other were more neurogenic (Graphs, Fig. 2d–e).

Fig. 2.

Clonal screening of nestin-positive bone marrow stromal cells. BMSC were diluted at clonal density (0.7 cell/well in 96-wells plates), in the presence of Wnt1 and BMP2. In those culture conditions, 1.2% of the cells proliferated as clonal culture. All clones were nestin-positive (a), p75NTR-positive (b) and Sox10-positive (c). Four clones were selected and co-cultured for 5 days with GFP-positive CGN (green). Tuj1 (red, d) and GFAP (red, e)-positive, GFP-negative cells were quantified. All clones were able to differentiate into GFAP- and Tuj1-positive cells, but the percentages of expression of these two markers varied from one clone to another. Nuclei were counterstained with Dapi (blue). Arrows show neural expression markers by clonally generated cells. Scale bars 30 μM

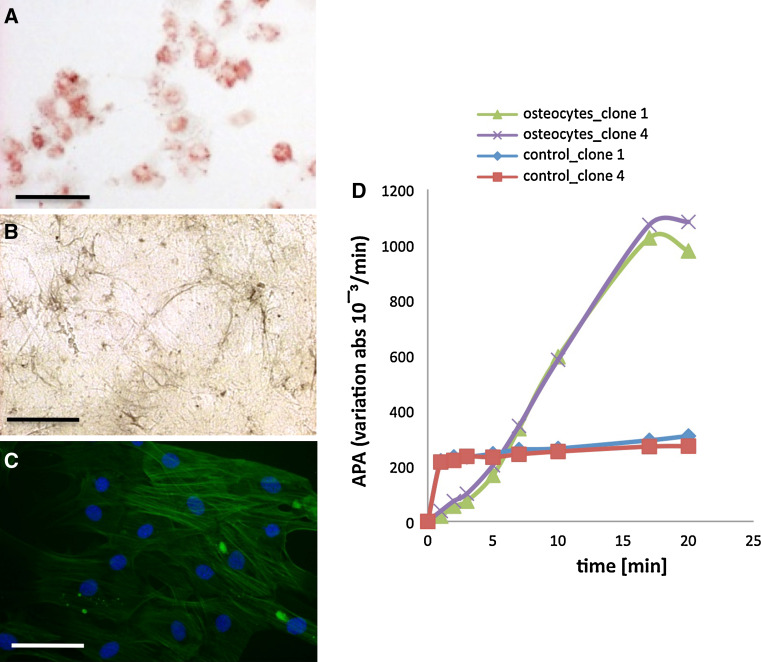

Clone 1 and clone 4 are multipotent progenitors

We then decided to further characterize the two most differing clones: clone 1 as gliogenic clone and clone 4 as neurogenic clone. Beside their ability to differentiate into glial and neuronal cells, we characterized their ability to differentiate into different types of mature cells classically obtained from neural crest or MSC. Clone 1 and 4 have thus been cultivated in specific differentiating media and were able to differentiate into adipocytes (Fig. 3a), melanocytes (Fig. 3b), smooth muscle (Fig. 3c) and osteocytes (Fig. 3d). No difference was observed between clones in their ability to differentiate into several mature cell types.

Fig. 3.

Functional characterization of selected Wnt1/BMP2 treated clones of BMSC. The differentiation potential of clone 1 and 4 was analyzed. Those clones were able to differentiate into adipocytes (oil red O coloration, a), melanocytes (l-Dopa colorimetric test, b), smooth muscle (SMA green, nuclei counterstained with Dapi-blue, c) and osteocytes (alkaline phosphatase activity, d) Scale bars 30 μm (a, c), 50 μM (b)

Confirmation of the neural crest origin

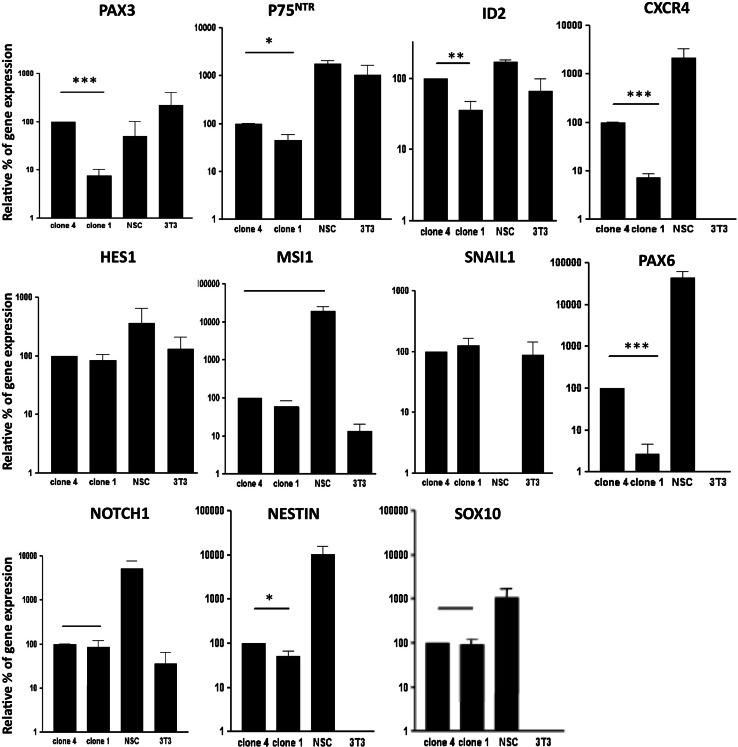

Although, selecting factors wnt1 and BMP2 would favor NCSC maintenance and proliferation, we were still unsure that clone 1 and 4 were neural crest-derived cells, even if they were nestin/Sox10/p75NTR-positive. We consequently performed microarray analyses comparing clone 1, clone 4, and a NCSC clone obtained from bone marrow isolated from double transgenic mice wnt1/CRE-R26R [13, 14]. Clone 1, 4, and wnt1/CRE-R26R NCSC clone expressed around 20,000 genes with 328 genes that were significantly different between clones 1 and 4; and 3,598 (clone 1) and 3,966 (clone 4) genes differentially expressed from wnt1/CRE-R26R NCSC clone. Looking at genes that are classically described for NCSC, we found that all clones expressed a good level of NCSC genes while embryonic stem cells (ES) genes or neural stem cell (NSC) genes were not well represented. Those results were confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR, analyzing expression of specific genes classically expressed by ES (like oct4, rex1, and nanog), by NSC (like nestin, notch1, msl1, pax3, pax6, sox1, hes1, and sox2) and by NCSC (like cxcr4, p75 NTR , sox10, twist1, mash1, id2, wnt1, snail1, ngn1 and foxd3). As observed in Table 2, clones 1 and 4 were positive for nestin, msl1, notch1, pax3, pax6, hes1, cxcr4, p75 NTR , sox10, id2 and snail1, but negative for oct4, nanog, rex1, sox1, sox2, twist1, wnt1, ngn1, mash1 and foxd3. As no qualitative difference was observed between clone 1 and clone 4, we performed several quantitative RT-PCR measurements of the expression of selected genes by the two clones. In these qRT-PCR experiments, we also compared the level of expression of those genes in two other cell types : 3T3 cells as a model of immature cells of mesenchymal origin and NSC as a model of immature neuroectodermal cells. In those conditions, clone 4 over-expressed p75 NTR, pax3, pax6, cxcr4, id2, and nestin (Fig. 4). We also compared our Microarray results with Microarrays data obtained in other studies of different types of cells including cranial NCSC, embryonic fibroblasts, MAPC, neurons, astrocytes, etc., and built a dendrogram reflecting the closeness of origin of the cells. As a result, wnt1/CRE-R26R NCSC clone, clone 1 and 4 were placed in the same group confirming their common embryonic origin (Fig. 5). Altogether, those results would strongly suggest a neural crest origin for clone 1 and 4.

Table 2.

Gene expression profile

| Quant. clone 1 | Quant. clone 4 | NCSC clone | ES | NSC | 3T3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ES | ||||||

| Oct4 | – | – | – | + | – | – |

| Nanog | – | – | – | + | – | – |

| Rex1 | – | – | – | + | – | – |

| NCSC | ||||||

| SOX10 | 106 | 100 | + | – | + | – |

| P75NTR | 44.8 | 100 | + | – | + | + |

| CXCR4 | 7.3 | 100 | + | – | + | – |

| ID2 | 36.1 | 100 | + | + | + | + |

| Wnt1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Ngn1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mash1 | – | – | + | – | + | – |

| Snail1 | 114.5 | 100 | + | + | – | + |

| Twist1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| NSC | ||||||

| Notch1 | 97.1 | 100 | + | + | + | + |

| MSI1 | 89.2 | 100 | + | + | + | + |

| Pax3 | 7.7 | 100 | – | – | + | + |

| Pax6 | 2.7 | 100 | – | + | + | – |

| Sox1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sox2 | – | – | + | – | + | – |

| Nestin | 50.3 | 100 | + | + | + | – |

| Hes1 | 83.4 | 100 | + | + | + | + |

Fig. 4.

Quantitative RT-PCR characterization of selected Wnt1/BMP2 treated clones of BMSC. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed on total RNA extracted from clone 1 and clone 4, as well as from neural stem cells (NSC-positive control for neural lineage) and fibroblasts (3T3-positive control for mesenchymal lineage) that were used as controls. The results of quantitative RT-PCR measurements are expressed as percent of each gene expression in clone 4 (arbitrarily set as 100%) after normalization with the house-keeping GAPDH gene expression. Three samples of each clone or control have been processed and for each experiment, measurements are made in triplicate. Student’s t test was performed to compare clone 1 and clone 4. Significant differences are indicated as *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001

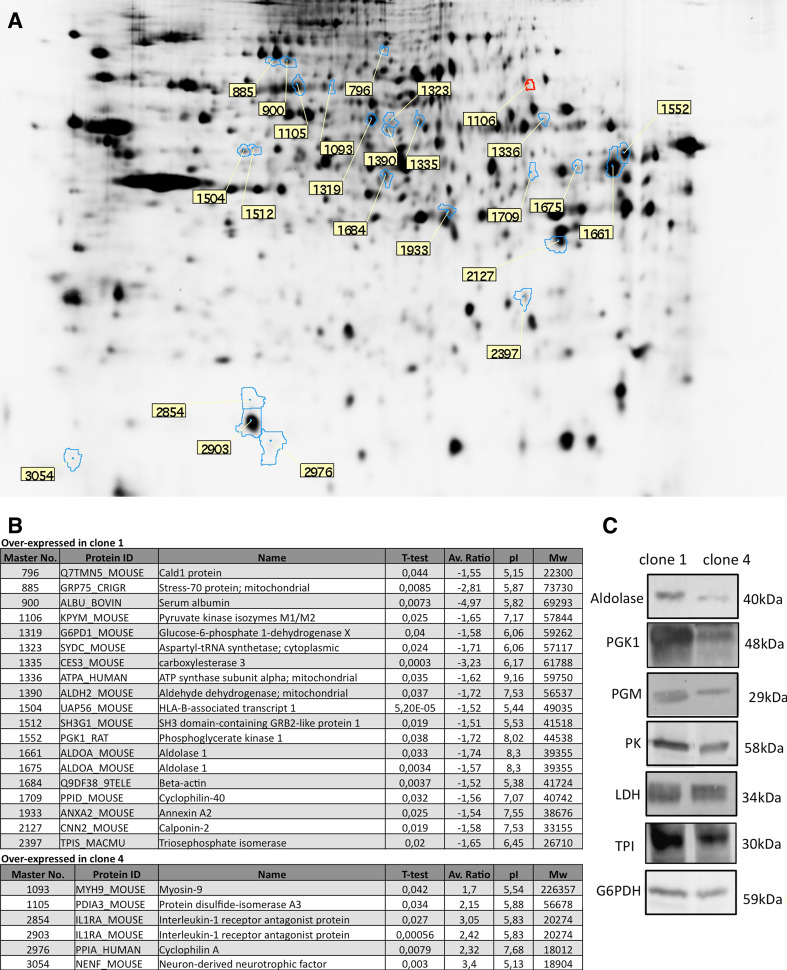

Consequence of glial versus neuronal cell fate decision

To complete our comparison between clone 1 and 4, and in an attempt to identify factors inducing neuronal or glial differentiation, we performed a proteomic analysis using 2D-DIGE based on CyDye technology. As observed in Fig. 6a, several proteins have been identified as significantly up or down-expressed in clone 4 compared to clone 1. However, although this provided no information why clone 1 would be oriented toward a glial fate while clone 4 would be oriented toward a neuronal fate, this proteomic analysis revealed a consequence of their fate decision. Indeed, one set of proteins seems particularly interesting, as they are all glycolytic enzymes overexpressed by clone 1 compared to clone 4 (Fig. 6b). We therefore analyzed aldolase, Pyruvate kinase M-type (PKM), phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK1), triosephosphate isomerase (TPI) as well as glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) expression by Western blot and confirmed the 2D-DIGE results (Fig. 6c), as those enzymes were overexpressed in clone 1 (gliogenic) compared to clone 4 (neurogenic).

Fig. 6.

Proteomic analysis of clone 1 and clone 4 using comparative 2D-DIGE technology. a, b A representative two-dimensional gel electrophoresis protein separation used for determining differentially expressed proteins in clone 1 and 4. Contoured spots correspond to proteins of interest that were picked for mass spectrometry identification. Master numbers of identified proteins from b are indicated in yellow boxes. b Lists the proteins overexpressed in clone 1 and clone 4 with their master number, Uniprot ID, name, calculated t test value for differential expression, calculated fold-expression ratio, theoretical isoelectric point and molecular mass. c Over-expression of glycolytic and carbohydrate metabolism enzymes has been confirmed by Western blotting

Discussion

In this study, we have been able to enrich NCSC population from adult bone marrow by seeding and cultivating those cells in the presence of wnt1 and BMP2, two factors known to support NCSC maintenance and proliferation [9]. In those conditions, we did observe an increase of the number of nestin-positive cells (presumable NCSC) in early passages. It has been previously shown that nestin expression was dependent on the number of passages [19, 20], which allowed nestin-positive cell population to proliferate and take-over. In this study, wnt1 and BMP2 seem to accelerate NCSC proliferation and to favor or to recruit those cells over other cell types, until reaching a plateau after four passages. More interestingly, induced cells cultivated in vitro for a maximum of two passages, were already able to differentiate into Tuj1-positive cells when untreated cells were unable to do so. Those results were consistent with a previous study showing that only nestin-positive MSC were able to differentiate into functional neurons [17]. Moreover, the same study demonstrated that nestin expression did not have any impact on glial differentiation [17] suggesting that GFAP expression could occur either in mesenchymal or in NCC. Furthermore, we demonstrated, in this study, that nestin expression was correlated with neural crest origin and consequently, to the neuronal differentiation ability of adult bone marrow cells.

Clonal analysis of cells selected in the presence of wnt1 and BMP2 confirmed the neural crest origin for these nestin/p75NTR/Sox10-positive cells as they were compared to a positive control isolated from adult bone marrow from wnt1-CRE/R26R double transgenic mice. Briefly, these double transgenic mice, in which Cre-recombinase expression was driven by wnt1 promoter, were mated to a ROSA26-LacZ or -GFP/-EYFP Cre-reporter (R26R) mouse. By this way, every NCC was permanently labeled and “followed” from embryonic stage to adulthood. Using this transgenic model, Sieber-Blum and Grim [10] demonstrated the presence of neural crest-derived cells in adult hair follicles, Wong et al. [11] identified NCC in mouse adult skin and Nagoshi et al. [12] isolated NCC from adult bone marrow.

A quantitative comparison of differentiating abilities between clones revealed that some clones were more gliogenic whereas others were more neurogenic. Quantitative RT-PCR comparison between neurogenic and gliogenic clones show that neurogenic clones (clone 4) over-expressed p75 NTR , nestin, cxcr4, id2, pax3, and pax6 genes. Those results are consistent with previous studies analyzing the implication of those genes in neuronal fate decision or orientation. Indeed, Peng et al. [21] demonstrated that CXCR4 expression was significantly up-regulated when neural progenitor cells were differentiating into neuronal precursors [21]. Id2, an inhibitor of basic helix-loop-helix factors (bHLH), has been shown to play a role in the cell fate specification of neuronal crest cells. Id2 overexpression results in overgrowth and premature neurogenesis of the dorsal neural tube [22]. There is some evidence for Pax3 involvement in regulating sensory neurogenesis in trunk NCC [23]. Likewise, Pax6 has been shown to play an important role promoting neurogenesis. In vivo, loss of Pax6 results in neural progenitors having reduced neurogenic potential [24, 25], whereas its over-expression in vitro pushes cells towards a neuronal fate [24–26]. Altogether, cxcr4, id2, pax3, and pax6 over-expression seem to be responsible for neuronal fate decision.

To complete our analysis about cell fate decision, we performed a proteomic comparison between clone 1 and clone 4, using 2D-DIGE technology. Unexpectedly, this proteomic comparison highlighted the over-expression of glycolytic enzymes by the gliogenic clone compared to the neurogenic clone, which is a consequence more than a cause of cell fate decision. Actually, neurons and glial cells are largely responsible for massive brain consumption of glucose. Under resting conditions, glial cells release 85% of the glucose they consume as lactate. Upon neuronal stimulation, glucose uptake, and lactate production are increased in neighboring glial cells. Neurons, by contrast, contribute minimally to glucose consumption by the brain, exhibiting a distinct preference for lactate utilization [28]. These data suggest that beyond the immunocytological characteristics of glial cells, gliogenic progenitors isolated from adult bone marrow are also prepared to actively support neuronal energy requirements.

In conclusion, wnt1 and BMP2 seem to be two factors recruiting neural crest-derived gliogenic and neurogenic progenitors, isolated from adult bone marrow. Those results might have a high impact on future cellular therapy protocols, as they could be used to minimize the in vitro culture time required to obtain a sufficient amount of NCSC from adult bone marrow and consequently, to lower as much as possible the risk of in vitro cell transformation [29]. However, as wnt1 and BMP2 had no distinctive effect on selecting gliogenic or neurogenic progenitors, the utilization of those cells in cellular therapy would require further cell purification.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Table S1. Gene expression profile comparison between clone 1 and clone 4. 328 genes have been identified as differentially expressed between clone 1 and 4, with a minimum of 2 fold difference

Table S2. Gene expression profile comparison between clone 1 and NCSC clone (wnt1-CRE/R26R). 3,578 genes have been identified as differentially expressed between clone 1 and 4, with a minimum of 2 fold difference

Table S3. Gene expression profile comparison between clone 4 and NCSC clone (wnt1-CRE/R26R). 3966 genes have been identified as differentially expressed between clone 4 and NCSC clone, with a minimum of 2 fold difference

Table S4. Gene expression profile of specific cell type genes: comparison between clone 1 and clone 4

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (FNRS) of Belgium, by a grant of the Action de Recherche Concertée de la Communauté Française de Belgique, and by the Belgian League against Multiple Sclerosis associated with Leon Fredericq Foundation. AG is a Marie Curie Host Fellow for Early Stage Research Training, EURON 020589 within the 6th FP of the EU, Marie Curie Actions, Human Resources and Mobility. SWG is a Postdoctoral researcher and PL is a Research Associate of the FNRS. Normalization and data filtering were performed using BRB-ArrayTools software version 3.8.1 developed by Dr. Richard Simons and BRB-ArrayTools Development Team http://linus.nci.nih.gov./BRB-ArrayTools.html.

Abbreviations

- BMP

Bone morphogenic proteins

- BMSC

Bone marrow stromal cells

- ES

Embryonic stem cells

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- MSC

Mesenchymal stem cells

- NCC

Neural crest cells

- NCSC

Neural crest stem cells

- NSC

Neural stem cells

Footnotes

B. Rogister and S. Wislet-Gendebien equally contributed to this paper.

References

- 1.Le Douarin NM, Ziller C, Couly GF. Patterning of neural crest derivatives in the avian embryo: in vivo and in vitro studies. Dev Biol. 1993;159:24–49. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker CV, Bronner-Fraser M, Le Douarin NM, Teillet MA. Early- and late-migrating cranial neural crest cell populations have equivalent developmental potential in vivo. Development. 1997;124:3077–3087. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.16.3077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teng L, Labosky PA. Neural crest stem cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;589:206–212. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-46954-6_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stemple DL, Anderson DJ. Isolation of a stem cell for neurons and glia from the mammalian neural crest. Cell. 1992;71:973–985. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90393-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sauka-Spengler T, Bronner-Fraser M. Development and evolution of the migratory neural crest: a gene regulatory perspective. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16:360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah NM, Groves AK, Anderson DJ. Alternative neural crest cell fates are instructively promoted by TGFbeta superfamily members. Cell. 1996;85:331–343. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah NM, Marchionni MA, Isaacs I, Stroobant P, Anderson DJ. Glial growth factor restricts mammalian neural crest stem cells to a glial fate. Cell. 1994;77:349–360. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrison SJ, Perez SE, Qiao Z, Verdi JM, Hicks C, Weinmaster G, Anderson DJ. Transient Notch activation initiates an irreversible switch from neurogenesis to gliogenesis by neural crest stem cells. Cell. 2000;101:499–510. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80860-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sommer L. Growth factors regulating neural crest cell fate decisions. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;589:197–205. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-46954-6_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sieber-Blum M, Grim M. The adult hair follicle: cradle for pluripotent neural crest stem cells. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2004;72:162–172. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong CE, Paratore C, Dours-Zimmermann MT, Rochat A, Pietri T, Suter U, Zimmermann DR, Dufour S, Thiery JP, Meijer D, Beermann F, Barrandon Y, Sommer L. Neural crest-derived cells with stem cell features can be traced back to multiple lineages in the adult skin. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:1005–1015. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagoshi N, Shibata S, Kubota Y, Nakamura M, Nagai Y, Satoh E, Morikawa S, Okada Y, Mabuchi Y, Katoh H, Okada S, Fukuda K, Suda T, Matsuzaki Y, Toyama Y, Okano H. Ontogeny and multipotency of neural crest-derived stem cells in mouse bone marrow, dorsal root ganglia, and whisker pad. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:392–403. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brault V, Moore R, Kutsch S, Ishibashi M, Rowitch DH, McMahon AP, Sommer L, Boussadia O, Kemler R. Inactivation of the beta-catenin gene by Wnt1-Cre-mediated deletion results in dramatic brain malformation and failure of craniofacial development. Development. 2001;128:1253–1264. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.8.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee HY, Kleber M, Hari L, Brault V, Suter U, Taketo MM, Kemler R, Sommer L. Instructive role of Wnt/beta-catenin in sensory fate specification in neural crest stem cells. Science. 2004;303:1020–1023. doi: 10.1126/science.1091611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lefebvre PP, Rogister B, Delree P, Leprince P, Selak I, Moonen G. Potassium-induced release of neuronotoxic activity by astrocytes. Brain Res. 1987;413:120–128. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okabe M, Ikawa M, Kominami K. “Green mice” as a source of ubiquitous green cells. FEBS Lett. 1997;407:313–319. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00313-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wislet-Gendebien S, Hans G, Leprince P, Rigo JM, Moonen G, Rogister B. Plasticity of cultured mesenchymal stem cells: switch from nestin-positive to excitable neuron-like phenotype. Stem Cells. 2005;23:392–402. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kléber M, Lee HY, Wurdak H, Buchstaller J, Riccomagno MM, Ittner LM, Suter U, Epstein DJ, Sommer L. Neural crest stem cell maintenance by combinatorial Wnt and BMP signaling. J Cell Biol. 2005;169((2)):309–320. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200411095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wislet-Gendebien S, Leprince P, Moonen G, Rogister B. Regulation of neural markers nestin and GFAP expression by cultivated bone marrow stromal cells. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3295–3302. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wautier F, Wislet-Gendebien S, Chanas G, Rogister B, Leprince P. Regulation of nestin expression by thrombin and cell density in cultures of bone mesenchymal stem cells and radial glial cells. BMC Neurosci. 2007;8:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-8-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng H, Kolb R, Kennedy JE, Zheng J. Differential expression of CXCL12 and CXCR4 during human fetal neural progenitor cell differentiation. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2007;2:251–258. doi: 10.1007/s11481-007-9081-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinsen BJ, Bronner-Fraser M. Neural crest specification regulated by the helix-loop-helix repressor Id2. Science. 1998;281:988–991. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5379.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koblar SA, Murphy M, Barrett GL, Underhill A, Gros P, Bartlett PF. Pax-3 regulates neurogenesis in neural crest-derived precursor cells. J Neurosci Res. 1999;56:518–530. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990601)56:5<518::AID-JNR7>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Estivill-Torrus G, Pearson H, van Heyningen V, Price DJ, Rashbass P. Pax6 is required to regulate the cell cycle and the rate of progression from symmetrical to asymmetrical division in mammalian cortical progenitors. Development. 2002;129:455–466. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.2.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faedo A, Quinn JC, Stoney P, Long JE, Dye C, Zollo M, Rubenstein JL, Price DJ, Bulfone A. Identification and characterization of a novel transcript down-regulated in Dlx1/Dlx2 and up-regulated in Pax6 mutant telencephalon. Dev Dyn. 2004;231:614–620. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corbin JG, Rutlin M, Gaiano N, Fishell G. Combinatorial function of the homeodomain proteins Nkx2.1 and Gsh2 in ventral telencephalic patterning. Development. 2003;130:4895–4906. doi: 10.1242/dev.00717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fukuda T, Kawano H, Osumi N, Eto K, Kawamura K. Histogenesis of the cerebral cortex in rat fetuses with a mutation in the Pax-6 gene. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2000;120:65–75. doi: 10.1016/S0165-3806(99)00187-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bolanos JP, Almeida A, Moncada S. Glycolysis: a bioenergetic or a survival pathway? Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez R, Rubio R, Masip M, Catalina P, Nieto A, de la Cueva T, Arriero M, San Martin N, de la Cueva E, Balomenos D, Menendez P, Garcia-Castro J. Loss of p53 induces tumorigenesis in p21-deficient mesenchymal stem cells. Neoplasia. 2009;11:397–407. doi: 10.1593/neo.81620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Gene expression profile comparison between clone 1 and clone 4. 328 genes have been identified as differentially expressed between clone 1 and 4, with a minimum of 2 fold difference

Table S2. Gene expression profile comparison between clone 1 and NCSC clone (wnt1-CRE/R26R). 3,578 genes have been identified as differentially expressed between clone 1 and 4, with a minimum of 2 fold difference

Table S3. Gene expression profile comparison between clone 4 and NCSC clone (wnt1-CRE/R26R). 3966 genes have been identified as differentially expressed between clone 4 and NCSC clone, with a minimum of 2 fold difference

Table S4. Gene expression profile of specific cell type genes: comparison between clone 1 and clone 4