Abstract

Neutrophils are an essential component of the innate immune response and a major contributor to inflammation. Consequently, neutrophil homeostasis in the blood is highly regulated. Neutrophil number in the blood is determined by the balance between neutrophil production in the bone marrow and release from the bone marrow to blood with neutrophil clearance from the circulation. This review will focus on mechanisms regulating neutrophil release from the bone marrow. In particular, recent data demonstrating a central role for the chemokines CXCL12 and CXCL2 in regulating neutrophil egress from the bone marrow will be discussed.

Keywords: Neutrophils, Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), CXCR4, CXCR2, CXCL12 (stromal derived factor-1; SDF-1), CXCL1, CXCL2, Leukocyte trafficking, WHIM syndrome

Introduction

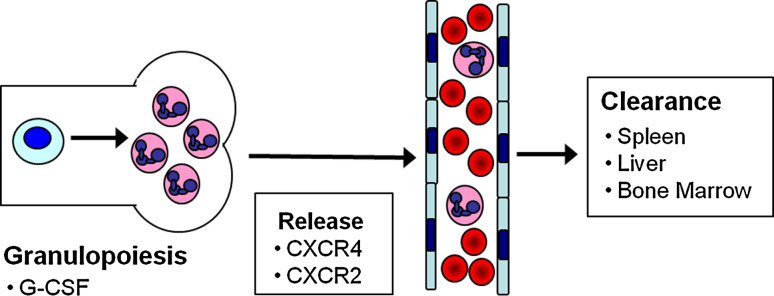

Neutrophils play an essential role in the innate arm of the immune system as the first responders to bacterial and fungal pathogens. Persistent neutropenia is associated with an increased risk of mostly bacterial infections. On the other hand, excessive neutrophil infiltration and activation contributes to tissue damage in certain inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis. Moreover, there is accumulating evidence that inflammatory markers, including blood neutrophil counts, predict ischemic events such as stroke [1] and myocardial infarction [2]. Not surprisingly, neutrophil number in the blood is tightly regulated. Neutrophil homeostasis in the blood is maintained by balancing neutrophil production (granulopoiesis) and release from the bone marrow with neutrophil clearance (Fig. 1). This review will focus on recent developments in our understanding of neutrophil release with only a brief summary of granulopoiesis and neutrophil clearance.

Fig. 1.

Neutrophil homeostasis: neutrophil number in the blood reflects a balance between neutrophil production (granulopoiesis) in the bone marrow and release into the blood with clearance from the blood in the spleen, liver and bone marrow. G-CSF is the principal cytokine driving granulopoiesis. Neutrophil release from the bone marrow is regulated by the opposing actions of CXCR4 and CXCR2 signaling. CXCR4 also contributes to neutrophil clearance from the blood

Granulopoiesis

Under normal conditions, neutrophils are produced exclusively in the bone marrow, where it is estimated that 1011 are generated on a daily basis in humans [3]. At baseline, the great majority (>98% in mice) of neutrophils are located in the bone marrow [4], providing a reservoir of neutrophils to respond to acute stresses, such as infection. Granulopoiesis is regulated by a series of external signals (cytokines) and internal signals (transcription factors). Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) is the principal cytokine regulating granulopoiesis. Mice lacking G-CSF or the G-CSF receptor (G-CSFR) display chronic severe neutropenia that is mainly due to impaired granulopoiesis [5, 6]. Studies of mice lacking other cytokines indicate a lesser role for interleukin-6, GM-CSF, and stem cell factor in regulating basal and stress granulopoiesis [7–9]. Granulocytic differentiation is regulated by the coordinated expression of a number of key myeloid transcription factors, including PU.1, members of the CCAAT enhancer binding protein family (CEBPα, CEBPβ, and CEBPε), and GFI-1. The contribution of these and other transcription factors to the regulation of granulopoiesis has been reviewed previously and will not be covered here [10].

Neutrophil clearance

Neutrophil clearance has traditionally been measured by ex vivo labeling of neutrophils and then measuring their clearance from the blood after autologous transplantation. These studies suggested a circulating lifespan of 6–8 h for murine and human neutrophils [11, 12]. Recent work by Pillay et al. [13] utilizing in vivo neutrophil labeling has called this long-standing estimate into question. While the lifespan of murine neutrophils in the circulation (18 h) was similar to that previously reported, the circulatory lifespan of human neutrophils was much longer (5.4 days), suggesting that ex vivo manipulation of human neutrophils may artificially increase neutrophil clearance from the blood.

Neutrophil clearance, typically via macrophage-mediated phagocytosis, occurs at multiple locations, including spleen, liver, bone marrow, and sites of inflammation (recently reviewed in [14]). Models in which radiolabeled neutrophils were injected into healthy donors indicate that under steady-state conditions the bone marrow, liver, and spleen contribute approximately equally to total neutrophil clearance [15–17]. The chemokine receptor CXCR4 plays an important role in the homing of aged neutrophils back to the bone marrow for clearance. Cell surface expression of CXCR4 on neutrophils increases with the age of the cell, and increased expression is associated with enhanced migration in response to CXCR4 stimulation [18, 19]. Blocking antibodies to CXCR4 impede bone marrow homing [16, 19, 20], while homing of CXCR4-deficient neutrophils to the bone marrow is reduced [21]. However, since clearance of CXCR4-deficient neutrophils is comparable to wild-type neutrophils, there likely is redundancy among the various clearance sites [21].

General features of neutrophil trafficking from the bone marrow

Neutrophils are released in a regulated fashion from the bone marrow, such that under normal conditions only mature neutrophils (and not neutrophil precursors) are released. Migration out of the bone marrow requires movement through the sinus wall, composed of endothelial cells, a basement membrane, and a layer of adventitial cells [22, 23]. Migration occurs through, rather than between, endothelial cells lining the sinusoids [24] in regions known as diaphragmatic fenestrae, where the endothelial luminal and abluminal cell membranes are fused [22, 25].

The bone marrow provides a large reservoir of mature neutrophils that can be readily mobilized in response to infection. In mice, only 1–2% of the total number of mature neutrophils is found in the blood, with the great majority remaining in the bone marrow [4]. A broad range of substances has been shown to induce neutrophil release from the bone marrow, including chemokines, cytokines, microbial products, and various other inflammatory mediators (e.g., C5a) [26].

Adhesion molecules regulating neutrophil trafficking

The essential role of certain integrins and selectins in the emigration of neutrophils from the blood to sites of inflammation is well established. Indeed, humans carrying genetic defects in β2-integrins or selectin biosynthesis present with leukocyte adhesion deficiency, a syndrome manifested by neutrophilia but a paucity of neutrophils at sites of infection (recently reviewed in [27]). Based on these observations, several groups have examined the role of integrins and selectins in neutrophil release from the bone marrow.

α4-Integrins

Bone marrow neutrophils express the α4-integrin VLA-4 (α4β1-integrin), and cell surface expression of α4-integrin is increased on mobilized neutrophils. Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), a major ligand for VLA-4, is expressed on bone marrow stromal cell populations, including bone marrow sinusoidal endothelium [28, 29]. Conditional deletion of α4-integrin in hematopoietic cells had no discernable effect on neutrophil trafficking [30], suggesting that α4-integrin signaling is dispensable for basal neutrophil release. On the other hand, α4-integrin may contribute to neutrophil release under stress conditions. In particular, Burdon and colleagues [31] showed that neutralizing antibodies to or antagonists of α4-integrin attenuated neutrophil mobilization by the chemokine CXCL2 (MIP2).

β2-Integrins

Neutrophils express high levels of the CD18/β2-integrins LFA-1 (αLβ2) and Mac-1 (αMβ2), which mediate adhesion to intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) [32]. Treatment of mice with neutralizing antibodies to β2-integrins augments neutrophil release in response to the chemokine CXCL2 [31], while neutrophil mobilization in response to LPS, C5a, or TNF-α is unaffected [33]. Though β2-integrin-deficient mice are neutrophilic [34], a series of elegant studies convincingly demonstrated that this is mostly secondary to a non-cell autonomous mechanism [35, 36]. Namely, the failure of β2-integrin-deficient neutrophils to emigrate into tissue initiates a feedback loop that includes IL-17 and G-CSF that, in turn, stimulates granulopoiesis and neutrophil release. Collectively, these data suggest that, in contrast to their essential role in mediating neutrophil emigration from the blood to inflammatory sites, β2-integrins appear to play only a minor role in regulating neutrophil trafficking from the bone marrow.

L-selectin

L-selectin is a member of the selectin family of adhesion molecules that contribute to the emigration of neutrophils from the blood to sites of inflammation. L-selectin expression on circulating neutrophils is lower than that on bone marrow resident neutrophils. Indeed, L-selectin is shed during neutrophil mobilization from the bone marrow to blood [37, 38]. These observations suggested that L-selectin may serve as a retention signal for neutrophils in the bone marrow. However, neutrophil trafficking is normal in L-selectin-deficient mice [39, 40], demonstrating a non-essential role for L-selectin, at least in mice.

Proteases

Bone marrow proteases have also attracted interest as potential mediators of neutrophil trafficking from the bone marrow. Neutrophil mobilization in response to interleukin-8 or G-CSF is associated with increased levels of proteases in the bone marrow, including matrix metalloprotease MMP-9, neutrophil elastase, and cathepsin G [25]. In vitro, these proteases are capable of cleaving molecules important for hematopoietic cell mobilization, including c-Kit, VCAM-1, and CXCL12 [25, 41–44]. However, several lines of evidence suggest that proteases are dispensable in neutrophil trafficking. Mice deficient in MMP-9, cathepsin G, neutrophil elastase, or dipeptidyl peptidase I (a molecule required for the processing of many serine proteases) all mobilize neutrophils normally in response to G-CSF [45]. Likewise, broad-spectrum inhibition of matrix metalloprotease activity does not impair mobilization in response to G-CSF [45] or CXCL2 [24].

CXCR4 signaling

The chemokine CXCL12/SDF-1α and its main receptor CXCR4 are key regulators of neutrophil trafficking in the bone marrow. CXCL12 is constitutively expressed at high levels in the bone marrow by several stromal cell populations, including osteoblasts, CXCL12-abundant reticular cells, and endothelial cells. CXCL12 is a potent chemoattractant for many hematopoietic cell types, including neutrophils [46–52]. Bone marrow neutrophils express low but detectable surface expression of CXCR4 and high intracellular levels, suggesting constitutive internalization of CXCR4 in vivo [19]. CXCL12 also has an additional receptor, CXCR7, which is believed to act as a decoy receptor to sequester the ligand; however, CXCR7 does not appear to play a major role in hematopoiesis [53, 54].

There is considerable evidence showing that CXCR4 signaling provides a key retention signal for neutrophils in the bone marrow. Cxcr4 −/− and Cxcl12 −/− mice die perinatally with hypocellular bone marrow [55–58]. Cxcr4 −/− bone marrow chimeras exhibit constitutive mobilization of mature and immature neutrophils into the circulation [47, 59]. Moreover, in mice carrying a myeloid-specific deletion of Cxcr4, there is constitutive neutrophilia and impaired neutrophil mobilization in response to G-CSF or infection with L. monocytogenes [21]. Likewise, conditional deletion of Cxcl12 is associated with neutrophilia [60]. Finally, treatment of humans or mice with a CXCR4 antagonist results in rapid neutrophil mobilization [61, 62].

WHIM syndrome

Genetic studies in patients with WHIM (warts, hypogammaglobulinemia, infections, and myelokathexis) syndrome confirm a crucial role for CXCR4 signaling in neutrophil trafficking from the bone marrow. A defining feature of WHIM syndrome is myelokathexis, which is characterized by severe neutropenia despite normal or increased numbers of neutrophils in the bone marrow. Truncation mutations in Cxcr4 have been identified in the majority of patients with WHIM syndrome [63]; in a recent review, 24 of 26 patients with WHIM syndrome had a Cxcr4 mutation [64]. These mutations are heterozygous and truncate a variable portion of the cytoplasmic tail of CXCR4. Two recent studies provide independent corroboration that CXCR4 mutations are causative of WHIM syndrome. Kawai and colleagues [65] showed that healthy human CD34+ cells transduced with truncated CXCR4 (but not wild-type CXCR4) developed a myelokathexis-like phenotype upon xenotransplantation into immunodeficient mice. Walters and colleagues [66] developed transgenic zebrafish expressing WHIM CXCR4 mutations. These zebrafish had neutrophil retention in hematopoietic tissue that was rescued by knock-down of CXCL12.

There is strong evidence that the truncation mutations of CXCR4 found in WHIM syndrome are gain-of-function mutations. WHIM neutrophils display enhanced chemotaxis to CXCL12 that likely is related to impaired receptor internalization and desensitization [67–69]. Signaling studies with WHIM-related CXCR4 truncation mutations suggest that the recruitment and/or activation of β-arrestins and G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) may be altered. Lagane et al. [70] showed that enhanced chemotaxis and Erk1/2 activation by WHIM-related CXCR4 truncations was dependent on β-arrestin-2. On the other hand, McCormick et al. [71] showed that β-arrestin-2 recruitment to a WHIM-related CXCR4 mutant was delayed. Moreover, they showed that recruitment of GRK6 but not GRK3 was impaired to mutant CXCR4. This is relevant, since GRK6 is responsible for serine phosphorylation of specific residues of the CXCR4 cytoplasmic domain and negatively regulates CXCR4-induced calcium mobilization [72].

CXCR2 signaling

Recent data implicate a second chemokine signaling pathway regulating neutrophil release from the bone marrow. The chemokines CXCL1 (KC) and CXCL2 (GROβ/MIP-2) are potent chemoattractants and activators of neutrophils, and are known to play a crucial role in the emigration of neutrophils from the blood to sites of inflammation [26, 73, 74]. CXCL1 and CXCL2 are constitutively expressed in the bone marrow by endothelial cells, megakaryocytes, and, to a lesser extent, osteoblasts [75, 76]. Administration of CXCL1 or CXCL2 results in the rapid (within 15 min) mobilization of neutrophils into the circulation [24, 31, 77]. These data suggest that CXCL1 and CXCL2 may serve to direct neutrophil release from the bone marrow.

The sole receptor (in mice) for CXCL1 and CXCL2 is CXCR2. Initial studies of Cxcr2 −/− mice provided conflicting data as to the role of CXCR2 signaling in neutrophil egress from the bone marrow. Whereas Cxcr2 −/− mice housed under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions are neutrophilic [78], mice housed under gnotobiotic conditions have normal levels of peripheral neutrophils [79, 80]. This discrepancy has been attributed to subclinical infection secondary to the well-known defect in the emigration of Cxcr2 −/− neutrophils from the blood to sites of infection. To address this issue more definitively, we generated bone marrow chimeras containing both wild-type and Cxcr2 −/− hematopoietic cells. In this way, the cell autonomous effects of the loss of CXCR2 signaling on neutrophil trafficking from the bone marrow were assessed. We showed that CXCR2-deficient neutrophils are selectively retained in the bone marrow, reproducing a myelokathexis-like phenotype [75]. Of interest, Diaz and colleagues recently identified a family with myelokathexis that carried homozygous loss-of-function Cxcr2 mutations (A.L. O’Shaughnessy, Q. Sun, and G.A. Diaz, unpublished observations). These data provide strong evidence that CXCR2 signaling directs neutrophil release from the bone marrow.

Tug-of-war model

The studies of Cxcr4 −/− and Cxcr2 −/− mice suggest that these chemokine axes provide apposing signals regulating neutrophil egress from the bone marrow. Whereas CXCR4 provides a retention signal for neutrophils in the bone marrow, CXCR2 signaling directs neutrophil release. RNA expression profiling and immunostaining of bone marrow sections suggest differential spatial expression of chemokines in the bone marrow. CXCL12 is expressed at the highest levels in osteoblasts and CAR cells. In contrast, CXCL1 and CXCL2 are expressed at high levels in bone marrow endothelial cells and megakaryocytes. Collectively, these data suggest a “tug-of-war” model wherein endothelial-derived chemokines (e.g., CXCL1 and CXCL2) direct neutrophil chemotaxis toward the vasculature for entry into the circulation, while endosteal osteoblasts produce chemokines (primarily CXCL12) that promote neutrophil retention (Fig. 2). Under basal conditions, the balance of chemokine production favors neutrophil retention in the bone marrow.

Fig. 2.

Tug-of-war model: CXCL12 (pink diamonds) expression from endosteal osteoblasts and other bone marrow stromal cells promotes the retention of neutrophils in the bone marrow, while endothelial and megakaryocytic CXCL2 (yellow circles) promotes the entry of neutrophils into the circulation. Under basal conditions, the balance of these chemokines favors neutrophil retention, with only a small fraction of neutrophils released into the circulation. In myelokathexis, mutations enhancing CXCR4 signaling or decreasing CXCR2 signaling result in abnormal bone marrow retention of neutrophils. G-CSF treatment alters the balance of chemokines in the bone marrow by both increasing CXCL2 expression from the endothelium and decreasing CXCL12 expression from osteoblast lineage cells. The net result of these changes is neutrophil mobilization into the circulation

In response to infectious stress, the expression of inflammatory cytokines, most notably G-CSF, is increased, leading to neutrophil mobilization into the blood [81]. G-CSF administration is associated with a marked suppression of endosteal osteoblasts, resulting in decreased CXCL12 expression in the bone marrow. G-CSF also is associated with cleavage of CXCR4 on neutrophils, further disrupting CXCR4 signaling [4, 49, 52]. On the other hand, G-CSF administration leads to increased CXCL2 expression in bone marrow endothelial cells and megakaryocytes [75, 76]. The net effect of G-CSF signaling is a shift in the balance of chemokine production to the endothelium, thereby promoting neutrophil release from the bone marrow.

A recent study addressed the contribution of CXCR2 and CXCR4 signaling during stress-induced neutrophil mobilization [82]. Specially, Delano and colleagues used a cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) model to induce sepsis and neutrophil mobilization. They showed that CXCL12 mRNA expression falls while CXCL1 expression increases in the bone marrow within 12 h of CLP. Studies with neutralizing antibodies suggested that CXCR4 but not CXCR2 signaling was required for efficient neutrophil mobilization. Thus, in this model of infectious stress, modulation of CXCR4 signaling plays a dominant role in regulating neutrophil release from the bone marrow.

Interactions between CXCR2 and CXCR4 signaling

There is accumulating evidence for cross talk between chemokine receptors. For example, treatment of neutrophils with CXCL1 or CXCL2 (CXCR2 ligands) results in heterologous desensitization of CXCR4 and decreased surface expression [20, 21, 83]. Thus, disruption of one chemokine signaling pathway may augment signaling of another chemokine receptor. In this way, the effect of small changes in CXCL12 and CXCL1/CXCL2 expression on neutrophils may be amplified. Consistent with this observation, pharmacologic blockade of CXCR4 signaling results in enhanced CXCR2 ligand-induced neutrophil mobilization in mice [19, 20, 77].

Studies of Cxcr4 −/−, Cxcr2 −/−, and doubly deficient Cxcr4 −/− × Cxcr2 −/− neutrophils suggest that CXCR4 signaling is dominant over CXCR2 signaling in regulating neutrophil trafficking in the bone marrow. As noted previously, Cxcr2 −/− neutrophils are selectively retained in the bone marrow, while Cxcr4 −/− neutrophils are constitutively mobilized [21, 75]. If CXCR2 and CXCR4 co-dominantly regulate neutrophil trafficking, then an intermediate phenotype is predicted. However, neutrophils lacking both CXCR4 and CXCR2 display constitutive mobilization to a similar degree as singly CXCR4 deficient neutrophils. Consistent with this observation, CXCL2 administration does not induce further neutrophil mobilization in mice lacking CXCR4 expression in neutrophils [21].

Summary and future directions

Current studies suggest that CXCR4 and CXCR2 signaling plays an important and antagonistic role in regulating neutrophil release from the bone marrow. Whereas CXCR4 signaling serves to retain neutrophils in the bone marrow, CXCR2 signaling promotes their release. The importance of these chemokines axes in neutrophil homeostasis in humans is established by the presence of gain-of-function CXCR4 mutations or loss-of-function CXCR2 mutations in patients with myelokathexis.

There are several outstanding questions about the role of CXCR4 and CXCR2 signals in the regulation of neutrophil trafficking. In mice lacking both CXCR4 and CXCR2, constitutive neutrophil mobilization is present [75]. Is there a second (CXCR2-independent) signal directing neutrophil egress or is complete CXCR4 disruption sufficient? G-CSF treatment induces neutrophil mobilization in large part by altering CXCL12 and CXCL2 expression in bone marrow stromal cells. Yet, the G-CSFR is not expressed on stromal cells, suggesting a non-cell autonomous mechanism by which G-CSF alters chemokine expression by stromal cells. Though the signals that mediate this response are currently unknown, a recent report showed that G-CSFR signals in bone marrow monocytes/macrophages were sufficient to decrease expression of bone marrow CXCL12 [84]. Finally, this model predicts that signals that modulate CXCR4 and/or CXCR2 responsiveness in neutrophils will affect neutrophil trafficking from the bone marrow. Consistent with this hypothesis, a recent study suggested that reduced expression of GRK3, which modulates CXCR4 signaling, may contribute to the pathogenesis of neutrophil retention in those rare patients with myelokathexis who do not have CXCR4 or CXCR2 mutation [85].

There are important clinical implications of this work. In particular, the data suggest that treatment with a CXCR4 antagonist would reverse the accentuated CXCR4 signaling present in most patients with WHIM syndrome. Indeed, plerixaflor (AMD3100), a CXCR4 antagonist that is FDA approved for hematopoietic stem cell mobilization, induces neutrophil mobilization in healthy volunteers. Two clinical trials of plerixafor for the treatment of patients with WHIM syndrome or myelokathexis are underway. Conversely, CXCR2 antagonism may prove useful for the treatment of inflammatory conditions characterized by excessive neutrophil infiltration. Small molecule antagonists of CXCR2 have been shown in clinical trials to decrease neutrophil recruitment and activation in airway inflammation [86–88].

There is considerable interest in the use of CXCR4 and CXCR2 antagonists to target the microenvironment in leukemia and other cancers (recently reviewed in [89], [90]). Although short-term use of CXCR4 and CXCR2 antagonists is well tolerated [87, 88, 91, 92], the effects of these agents on neutrophil trafficking may be associated with significant long-term toxicities. CXCR4 antagonists, by inducing neutrophil release from the bone marrow and blocking neutrophil clearance in the bone marrow, may exacerbate inflammatory diseases. While some murine models of inflammatory diseases are indeed exacerbated by CXCR4 antagonists [93], other models show decreased inflammation [94–96]. CXCR2 antagonists, by blocking neutrophil release from the bone marrow and by inhibiting neutrophil extravasation to inflammatory sites, may increase the risk of infection; in fact, two recent studies have documented transient drops in absolute neutrophil counts following administration of CXCR2 antagonists [87, 88]. Since there are significant differences in human and murine neutrophil trafficking and chemokine receptor expression, clinical trials in humans will ultimately be needed to define the toxicities of long-term CXCR4 and CXCR2 antagonist use.

References

- 1.Grau AJ, Boddy AW, Dukovic DA, Buggle F, Lichy C, Brandt T, Hacke W. Leukocyte count as an independent predictor of recurrent ischemic events. Stroke. 2004;35(5):1147–1152. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000124122.71702.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madjid M, Awan I, Willerson JT, Casscells SW. Leukocyte count and coronary heart disease: implications for risk assessment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(10):1945–1956. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demetri GD, Griffin JD. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and its receptor. Blood. 1991;78(11):2791–2808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Semerad CL, Liu F, Gregory AD, Stumpf K, Link DC. G-CSF is an essential regulator of neutrophil trafficking from the bone marrow to the blood. Immunity. 2002;17(4):413–423. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lieschke GJ, Grail D, Hodgson G, Metcalf D, Stanley E, Cheers C, Fowler KJ, Basu S, Zhan YF, Dunn AR. Mice lacking granulocyte colony-stimulating factor have chronic neutropenia, granulocyte and macrophage progenitor cell deficiency, and impaired neutrophil mobilization. Blood. 1994;84(6):1737–1746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu F, Wu HY, Wesselschmidt R, Kornaga T, Link DC. Impaired production and increased apoptosis of neutrophils in granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor-deficient mice. Immunity. 1996;5(5):491–501. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80504-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molineux G, Migdalska A, Szmitkowski M, Zsebo K, Dexter TM. The effects on hematopoiesis of recombinant stem cell factor (ligand for c-kit) administered in vivo to mice either alone or in combination with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Blood. 1991;78(4):961–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seymour JF, Lieschke GJ, Grail D, Quilici C, Hodgson G, Dunn AR. Mice lacking both granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (CSF) and granulocyte-macrophage CSF have impaired reproductive capacity, perturbed neonatal granulopoiesis, lung disease, amyloidosis, and reduced long-term survival. Blood. 1997;90(8):3037–3049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu F, Poursine-Laurent J, Wu HY, Link DC. Interleukin-6 and the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor are major independent regulators of granulopoiesis in vivo but are not required for lineage commitment or terminal differentiation. Blood. 1997;90(7):2583–2590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosmarin AG, Yang Z, Resendes KK. Transcriptional regulation in myelopoiesis: hematopoietic fate choice, myeloid differentiation, and leukemogenesis. Exp Hematol. 2005;33(2):131–143. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cartwright GE, Athens JW, Wintrobe MM. The kinetics of granulopoiesis in normal man. Blood. 1964;24:780–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dancey JT, Deubelbeiss KA, Harker LA, Finch CA. Neutrophil kinetics in man. J Clin Invest. 1976;58(3):705–715. doi: 10.1172/JCI108517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pillay J, Braber I, Vrisekoop N, Kwast LM, Boer RJ, Borghans JA, Tesselaar K, Koenderman L. In vivo labeling with 2H2O reveals a human neutrophil lifespan of 5.4 days. Blood. 2010;116(4):625–627. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-259028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rankin SM. The bone marrow: a site of neutrophil clearance. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88(2):241–251. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0210112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thakur ML, Lavender JP, Arnot RN, Silvester DJ, Segal AW. Indium-111-labeled autologous leukocytes in man. J Nucl Med. 1977;18(10):1014–1021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suratt BT, Young SK, Lieber J, Nick JA, Henson PM, Worthen GS. Neutrophil maturation and activation determine anatomic site of clearance from circulation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281(4):L913–L921. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.4.L913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furze RC, Rankin SM. Neutrophil mobilization and clearance in the bone marrow. Immunology. 2008;125(3):281–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02950.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagase H, Miyamasu M, Yamaguchi M, Imanishi M, Tsuno NH, Matsushima K, Yamamoto K, Morita Y, Hirai K. Cytokine-mediated regulation of CXCR4 expression in human neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71(4):711–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin C, Burdon PCE, Bridger G, Gutierrez-Ramos JC, Williams TJ, Rankin SM. Chemokines acting via CXCR2 and CXCR4 control the release of neutrophils from the bone marrow and their return following senescence. Immunity. 2003;19(4):583–593. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suratt BT, Petty JM, Young SK, Malcolm KC, Lieber JG, Nick JA, Gonzalo J-A, Henson PM, Worthen GS. Role of the CXCR4/SDF-1 chemokine axis in circulating neutrophil homeostasis. Blood. 2004;104(2):565–571. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eash KJ, Means JM, White DW, Link DC. CXCR4 is a key regulator of neutrophil release from the bone marrow under basal and stress granulopoiesis conditions. Blood. 2009;113(19):4711–4719. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-177287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell FR. Ultrastructural studies of transmural migration of blood cells in the bone marrow of rats, mice and guinea pigs. Am J Anat. 1972;135(4):521–535. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001350406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inoue S, Osmond DG. Basement membrane of mouse bone marrow sinusoids shows distinctive structure and proteoglycan composition: a high resolution ultrastructural study. Anat Rec. 2001;264(3):294–304. doi: 10.1002/ar.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burdon PCE, Martin C, Rankin SM. Migration across the sinusoidal endothelium regulates neutrophil mobilization in response to ELR + CXC chemokines. Br J Haematol. 2008;142(1):100–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lévesque JP, Hendy J, Takamatsu Y, Williams B, Winkler IG, Simmons PJ. Mobilization by either cyclophosphamide or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor transforms the bone marrow into a highly proteolytic environment. Exp Hematol. 2002;30(5):440–449. doi: 10.1016/S0301-472X(02)00788-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Opdenakker G, Fibbe WE, Van Damme J. The molecular basis of leukocytosis. Immunol Today. 1998;19(4):182–189. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(97)01243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Etzioni A. Genetic etiologies of leukocyte adhesion defects. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21(5):481–486. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simmons PJ, Masinovsky B, Longenecker BM, Berenson R, Torok-Storb B, Gallatin WM. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expressed by bone marrow stromal cells mediates the binding of hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 1992;80(2):388–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schweitzer KM, Dräger AM, van der Valk P, Thijsen SF, Zevenbergen A, Theijsmeijer AP, van der Schoot CE, Langenhuijsen MM. Constitutive expression of E-selectin and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 on endothelial cells of hematopoietic tissues. Am J Pathol. 1996;148(1):165–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scott LM, Priestley GV, Papayannopoulou T. Deletion of alpha4 integrins from adult hematopoietic cells reveals roles in homeostasis, regeneration, and homing. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(24):9349–9360. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.9349-9360.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burdon PCE, Martin C, Rankin SM. The CXC chemokine MIP-2 stimulates neutrophil mobilization from the rat bone marrow in a CD49d-dependent manner. Blood. 2005;105(6):2543–2548. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, Nourshargh S. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(9):678–689. doi: 10.1038/nri2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larangeira AP, Silva AR, Gomes RN, Penido C, Henriques MG, Castro-Faria-Neto HC, Bozza PT. Mechanisms of allergen- and LPS-induced bone marrow eosinophil mobilization and eosinophil accumulation into the pleural cavity: a role for CD11b/CD18 complex. Inflamm Res. 2001;50(6):309–316. doi: 10.1007/PL00000249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scharffetter-Kochanek K, Lu H, Norman K, van Nood N, Munoz F, Grabbe S, McArthur M, Lorenzo I, Kaplan S, Ley K, Smith CW, Montgomery CA, Rich S, Beaude AL. Spontaneous skin ulceration and defective T cell function in CD18 null mice. J Exp Med. 1998;188(1):119–131. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forlow SB, Schurr JR, Kolls JK, Bagby GJ, Schwarzenberger PO, Ley K. Increased granulopoiesis through interleukin-17 and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in leukocyte adhesion molecule-deficient mice. Blood. 2001;98(12):3309–3314. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.12.3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stark MA, Huo Y, Burcin TL, Morris MA, Olson TS, Ley K. Phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils regulates granulopoiesis via IL-23 and IL-17. Immunity. 2005;22(3):285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rogowski O, Sasson Y, Kassirer M, Zeltser D, Maharshak N, Arber N, Halperin P, Serrov J, Sorkin P, Eldor A, Berliner S. Down-regulation of the CD62L antigen as a possible mechanism for neutrophilia during inflammation. Br J Haematol. 1998;101(4):666–669. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kassirer M, Zeltser D, Gluzman B, Leibovitz E, Goldberg Y, Roth A, Keren G, Rotstein R, Shapira I, Arber N, Berliner AS. The appearance of L-selectin (low) polymorphonuclear leukocytes in the circulating pool of peripheral blood during myocardial infarction correlates with neutrophilia and with the size of the infarct. Clin Cardiol. 1999;22(11):721–726. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960221109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robinson SD, Frenette PS, Rayburn H, Cummiskey M, Ullman-Culleré M, Wagner DD, Hynes RO. Multiple, targeted deficiencies in selectins reveal a predominant role for P-selectin in leukocyte recruitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(20):11452–11457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arbonés ML, Ord DC, Ley K, Ratech H, Maynard-Curry C, Otten G, Capon DJ, Tedder TF. Lymphocyte homing and leukocyte rolling and migration are impaired in L-selectin-deficient mice. Immunity. 1994;1(4):247–260. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heissig B, Hattori K, Dias S, Friedrich M, Ferris B, Hackett NR, Crystal RG, Besmer P, Lyden D, Moore MAS, Werb Z, Rafii S. Recruitment of stem and progenitor cells from the bone marrow niche requires MMP-9 mediated release of kit-ligand. Cell. 2002;109(5):625–637. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00754-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petit I, Szyper-Kravitz M, Nagler A, Lahav M, Peled A, Habler L, Ponomaryov T, Taichman RS, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Fujii N, Sandbank J, Zipori D, Lapidot T. G-CSF induces stem cell mobilization by decreasing bone marrow SDF-1 and up-regulating CXCR4. Nat Immunol. 2002;3(7):687–694. doi: 10.1038/ni813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lévesque J-P, Hendy J, Winkler IG, Takamatsu Y, Simmons PJ. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor induces the release in the bone marrow of proteases that cleave c-KIT receptor (CD117) from the surface of hematopoietic progenitor cells. Exp Hematol. 2003;31(2):109–117. doi: 10.1016/S0301-472X(02)01028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lévesque J-P, Hendy J, Takamatsu Y, Simmons PJ, Bendall LJ. Disruption of the CXCR4/CXCL12 chemotactic interaction during hematopoietic stem cell mobilization induced by GCSF or cyclophosphamide. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(2):187–196. doi: 10.1172/JCI15994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Levesque J, Liu F, Simmons PJ, Betsuyaku T, Senior RM, Pham C, Link DC. Characterization of hematopoietic progenitor mobilization in protease-deficient mice. Blood. 2004;104(1):65–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aiuti A, Webb IJ, Bleul C, Springer T, Gutierrez-Ramos JC. The chemokine SDF-1 is a chemoattractant for human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells and provides a new mechanism to explain the mobilization of CD34+ progenitors to peripheral blood. J Exp Med. 1997;185(1):111–120. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawabata K, Ujikawa M, Egawa T, Kawamoto H, Tachibana K, Iizasa H, Katsura Y, Kishimoto T, Nagasawa T. A cell-autonomous requirement for CXCR4 in long-term lymphoid and myeloid reconstitution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(10):5663–5667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shirozu M, Nakano T, Inazawa J, Tashiro K, Tada H, Shinohara T, Honjo T. Structure and chromosomal localization of the human stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF1) gene. Genomics. 1995;28(3):495–500. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Semerad CL, Christopher MJ, Liu F, Short B, Simmons PJ, Winkler I, Levesque J, Chappel J, Ross FP, Link DC. G-CSF potently inhibits osteoblast activity and CXCL12 mRNA expression in the bone marrow. Blood. 2005;106(9):3020–3027. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ara T, Nakamura Y, Egawa T, Sugiyama T, Abe K, Kishimoto T, Matsui Y, Nagasawa T. Impaired colonization of the gonads by primordial germ cells in mice lacking a chemokine, stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(9):5319–5323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730719100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Noda M, Nagasawa T. Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity. 2006;25(6):977–988. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Christopher MJ, Liu F, Hilton MJ, Long F, Link DC. Suppression of CXCL12 production by bone marrow osteoblasts is a common and critical pathway for cytokine-induced mobilization. Blood. 2009;114(7):1331–1339. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sierro F, Biben C, Martínez-Muñoz L, Mellado M, Ransohoff RM, Li M, Woehl B, Leung H, Groom J, Batten M, Harvey RP, Martínez-A C, Mackay CR, Mackay F. Disrupted cardiac development but normal hematopoiesis in mice deficient in the second CXCL12/SDF-1 receptor, CXCR7. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(37):14759–14764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702229104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berahovich RD, Zabel BA, Penfold MET, Lewén S, Wany Y, Miao Z, Gan L, Pereda J, Dias J, Slukvin II, McGrath KE, Jaen JC, Schall TJ. CXCR7 protein is not expressed on human or mouse leukocytes. J Immunol. 2010;185(9):5130–5139. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nagasawa T, Hirota S, Tachibana K, Takakura N, Nishikawa S, Kitamura Y, Yoshida N, Kikutani H, Kishimoto T. Defects of B-cell lymphopoiesis and bone-marrow myelopoiesis in mice lacking the CXC chemokine PBSF/SDF-1. Nature. 1996;382(6592):635–638. doi: 10.1038/382635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zou YR, Kottmann AH, Kuroda M, Taniuchi I, Littman DR. Function of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in haematopoiesis and in cerebellar development. Nature. 1998;393(6685):595–599. doi: 10.1038/31269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tachibana K, Hirota S, Iizasa H, Yoshida H, Kawabata K, Kataoka Y, Kitamura Y, Matsushima K, Yoshida N, Nishikawa S, Kishimoto T, Nagasawa T. The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is essential for vascularization of the gastrointestinal tract. Nature. 1998;393(6685):591–594. doi: 10.1038/31261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ma Q, Jones D, Borghesani PR, Segal RA, Nagasawa T, Kishimoto T, Bronson RT, Springer TA. Impaired B-lymphopoiesis, myelopoiesis, and derailed cerebellar neuron migration in CXCR4- and SDF-1-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(16):9448–9453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ma Q, Jones D, Springer TA. The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is required for the retention of B lineage and granulocytic precursors within the bone marrow microenvironment. Immunity. 1999;10(4):463–471. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tzeng Y, Li H, Kang Y, Chen W, Cheng W, Lai D. Loss of Cxcl12/Sdf-1 in adult mice decreases the quiescent state of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells and alters the pattern of hematopoietic regeneration after myelosuppression. Blood. 2011;117(2):429–439. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-266833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liles WC, Broxmeyer HE, Rodger E, Wood B, Hübel K, Cooper S, Hangoc G, Bridger GJ, Henson GW, Calandra G, Dale DC. Mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells in healthy volunteers by AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. Blood. 2003;102(8):2728–2730. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Broxmeyer HE, Orschell CM, Clapp DW, Hangoc G, Cooper S, Plett PA, Liles WC, Li X, Graham-Evans B, Campbell TB, Calandra G, Bridger G, Dale DC, Srour EF. Rapid mobilization of murine and human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells with AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. J Exp Med. 2005;201(8):1307–1318. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hernandez PA, Gorlin RJ, Lukens JN, Taniuchi S, Bohinjec J, Francois F, Klotman ME, Diaz GA. Mutations in the chemokine receptor gene CXCR4 are associated with WHIM syndrome, a combined immunodeficiency disease. Nat Genet. 2003;34(1):70–74. doi: 10.1038/ng1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kawai T, Malech HL. WHIM syndrome: congenital immune deficiency disease. Curr Opin Hematol. 2009;16(1):20–26. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32831ac557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kawai T, Choi U, Cardwell L, DeRavin SS, Naumann N, Whiting-Theobald NL, Linton GF, Moon J, Murphy PM, Malech HL. WHIM syndrome myelokathexis reproduced in the NOD/SCID mouse xenotransplant model engrafted with healthy human stem cells transduced with C-terminus-truncated CXCR4. Blood. 2007;109(1):78–84. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-025296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Walters KB, Green JM, Surfus JC, Yoo SK, Huttenlocher A. Live imaging of neutrophil motility in a zebrafish model of WHIM syndrome. Blood. 2010;116(15):2803–2811. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gulino AV, Moratto D, Sozzani S, Cavadini P, Otero K, Tassone L, Imberti L, Pirovano S, Notarangelo LD, Soresina R, Mazzolari E, Nelson DL, Notarangelo LD, Badolato R. Altered leukocyte response to CXCL12 in patients with warts hypogammaglobulinemia, infections, myelokathexis (WHIM) syndrome. Blood. 2004;104(2):444–452. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Balabanian K, Lagane B, Pablos JL, Laurent L, Planchenault T, Verola O, Lebbe C, Kerob D, Dupuy A, Hermine O, Nicolas J, Latger-Cannard V, Bensoussan D, Bordigoni P, Baleux F, Le Deist F, Virelizier J, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Bachelerie F. WHIM syndromes with different genetic anomalies are accounted for by impaired CXCR4 desensitization to CXCL12. Blood. 2005;105(6):2449–2457. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kawai T, Choi U, Whiting-Theobald NL, Linton GF, Brenner S, Sechler JMG, Murphy PM, Malech HL. Enhanced function with decreased internalization of carboxy-terminus truncated CXCR4 responsible for WHIM syndrome. Exp Hematol. 2005;33(4):460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lagane B, Chow KYC, Balabanian K, Levoye A, Harriague J, Planchenault T, Baleux F, Gunera-Saad N, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Bachelerie F. CXCR4 dimerization and beta-arrestin-mediated signaling account for the enhanced chemotaxis to CXCL12 in WHIM syndrome. Blood. 2008;112(1):34–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-102103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McCormick PJ, Segarra M, Gasperini P, Gulino AV, Tosato G. Impaired recruitment of Grk6 and beta-Arrestin 2 causes delayed internalization and desensitization of a WHIM syndrome-associated CXCR4 mutant receptor. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(12):e8102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Busillo JM, Armando S, Sengupta R, Meucci O, Bouvier M, Benovic JL. Site-specific phosphorylation of CXCR4 is dynamically regulated by multiple kinases and results in differential modulation of CXCR4 signaling. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(10):7805–7817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.091173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Laterveer L, Lindley IJ, Hamilton MS, Willemze R, Fibbe WE. Interleukin-8 induces rapid mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells with radioprotective capacity and long-term myelolymphoid repopulating ability. Blood. 1995;85(8):2269–2275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.King AG, Horowitz D, Dillon SB, Levin R, Farese AM, MacVittie TJ, Pelus LM. Rapid mobilization of murine hematopoietic stem cells with enhanced engraftment properties and evaluation of hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization in rhesus monkeys by a single injection of SB-251353, a specific truncated form of the human CXC chemokine GRObeta. Blood. 2001;97(6):1534–1542. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.6.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Eash KJ, Greenbaum AM, Gopalan PK, Link DC. CXCR2 and CXCR4 antagonistically regulate neutrophil trafficking from murine bone marrow. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(7):2423–2431. doi: 10.1172/JCI41649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Köhler A, De Filippo K, Hasenberg M, van den Brandt C, Nye E, Hosking MP, Lane TE, Männ L, Ransohoff RM, Hauser AE, Winter O, Schraven B, Geiger H, Hogg N, Gunzer M. G-CSF-mediated thrombopoietin release triggers neutrophil motility and mobilization from bone marrow via induction of Cxcr2 ligands. Blood. 2011;117(16):4349–4357. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-308387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wengner AM, Pitchford SC, Furze RC, Rankin SM. The coordinated action of G-CSF and ELR + CXC chemokines in neutrophil mobilization during acute inflammation. Blood. 2008;111(1):42–49. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cacalano G, Lee J, Kikly K, Ryan AM, Pitts-Meek S, Hultgren B, Wood WI, Moore MW. Neutrophil and B cell expansion in mice that lack the murine IL-8 receptor homolog. Science. 1994;265(5172):682–684. doi: 10.1126/science.8036519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shuster DE, Kehrli ME, Ackermann MR. Neutrophilia in mice that lack the murine IL-8 receptor homolog. Science. 1995;269(5230):1590–1591. doi: 10.1126/science.7667641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Broxmeyer HE, Cooper S, Cacalano G, Hague NL, Bailish E, Moore MW. Involvement of Interleukin (IL) 8 receptor in negative regulation of myeloid progenitor cells in vivo: evidence from mice lacking the murine IL-8 receptor homologue. J Exp Med. 1996;184(5):1825–1832. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kawakami M, Tsutsumi H, Kumakawa T, Abe H, Hirai M, Kurosawa S, Mori M, Fukushima M. Levels of serum granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in patients with infections. Blood. 1990;76(10):1962–1964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Delano MJ, Kelly-Scumpia KM, Thayer TC, Winfield RD, Scumpia PO, Cuenca AG, Harrington PB, O’Malley KA, Warner E, Gabrilovich S, Mathews CE, Laface D, Heyworth PG, Ramphal R, Strieter RM, Moldawer LL, Efron PA. Neutrophil mobilization from the bone marrow during polymicrobial sepsis is dependent on CXCL12 signaling. J Immunol. 2011;187(2):911–918. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Richardson RM, Tokunaga K, Marjoram R, Sata T, Snyderman R. Interleukin-8-mediated heterologous receptor internalization provides resistance to HIV-1 infectivity: Role of signal strength and receptor desensitization. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(18):15867–15873. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211745200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Christopher MJ, Rao M, Liu F, Woloszynek JR, Link DC. Expression of the G-CSF receptor in monocytic cells is sufficient to mediate hematopoietic progenitor mobilization by G-CSF in mice. J Exp Med. 2011;208(2):251–260. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Balabanian K, Levoye A, Klemm L, Lagane B, Hermine O, Harriague J, Baleux F, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Bachelerie F. Leukocyte analysis from WHIM syndrome patients reveals a pivotal role for GRK3 in CXCR4 signaling. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(3):1074–1084. doi: 10.1172/JCI33187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bradley ME, Bond ME, Manini J, Brown Z, Charlton SJ. SB265610 is an allosteric, inverse agonist at the human CXCR2 receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(1):328–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Holz O, Khalilieh S, Ludwig-Sengpiel A, Watz H, Stryszak P, Soni P, Tsai M, Sadeh J, Magnussen H. SCH527123, a novel CXCR2 antagonist, inhibits ozone-induced neutrophilia in healthy subjects. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(3):564–570. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00048509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lazaar AL, Sweeney LE, Macdonald AJ, Alexis NE, Chen C, Tal-Singer R. SB-656933, a novel CXCR2 selective antagonist, inhibits ex vivo neutrophil activation and ozone-induced airway inflammation in humans. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72(2):282–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03968.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Burger JA, Peled A. CXCR4 antagonists: targeting the microenvironment in leukemia and other cancers. Leukemia. 2009;23(1):43–52. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lazennec G, Richmond A. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: new insights into cancer-related inflammation. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16(3):133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hendrix CW, Flexner C, MacFarland RT, Giandomenico C, Fuchs EJ, Redpath E, Bridger G, Henson GW. Pharmacokinetics and safety of AMD-3100, a novel antagonist of the CXCR-4 chemokine receptor, in human volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44(6):1667–1673. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.6.1667-1673.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hendrix CW, Collier AC, Lederman MM, Schols D, Pollard RB, Brown S, Jackson JB, Coombs RW, Glesby MJ, Flexner CW, Bridger GJ, Badel K, MacFarland RT, Henson GW, Calandra G. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and antiviral activity of AMD3100, a selective CXCR4 receptor inhibitor, in HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37(2):1253–1262. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000137371.80695.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McCandless EE, Wang Q, Woerner BM, Harper JM, Klein RS. CXCL12 limits inflammation by localizing mononuclear infiltrates to the perivascular space during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2006;177(11):8053–8064. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.8053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Matthys P, Hatse S, Vermeire K, Wuyts A, Bridger G, Henson GW, De Clercq E, Billiau A, Schols D. AMD3100, a potent and specific antagonist of the stromal cell-derived factor-1 chemokine receptor CXCR4, inhibits autoimmune joint inflammation in IFN-gamma receptor-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2001;167(8):4686–4692. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lukacs NW, Berlin A, Schols D, Skerlj RT, Bridger GJ. AMD3100, a CxCR4 antagonist, attenuates allergic lung inflammation and airway hyperreactivity. Am J Pathol. 2002;160(4):1353–1360. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62562-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xia X-M, Wang F-Y, Xu W-A, Wang Z-K, Liu J, Lu Y-K, Jin X-X, Lu H, Shen Y-Z. CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 attenuates colonic damage in mice with experimental colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(23):2873–2880. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i23.2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]