Abstract

Latently infected cells harbor human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) proviral DNA copies integrated in heterochromatin, allowing persistence of transcriptionally silent proviruses. It is widely accepted that hypoacetylation of histone proteins by histone deacetylases (HDACs) is involved in maintaining the HIV-1 latency by repressing viral transcription. HIV-1 replication can be induced from latently infected cells by environmental factors, such as inflammation and co-infection with other microbes. It is known that a bacterial metabolite butyric acid inhibits catalytic action of HDAC and induces transcription of silenced genes including HIV-1 provirus. There are a number of such bacteria in gut, vaginal, and oral cavities that produce butyric acid during their anaerobic glycolysis. Since these organs are known to be the major site of HIV-1 transmission and its replication, we explored a possibility that explosive viral replication in these organs could be ascribable to butyric acid produced from anaerobic resident bacteria. In this study, we demonstrate that the culture supernatant of various bacteria producing butyric acid could greatly reactivate the latently-infected HIV-1. These bacteria include Fusobacterium nucleatum (commonly present in oral cavity, and gut), Clostridium cochlearium, Eubacterium multiforme (gut), and Anaerococcus tetradius (vagina). We also clarified that butyric acid in these culture supernatants could induce histone acetylation and HIV-1 replication by inhibiting HDAC. Our observations indicate that butyric acid-producing bacteria could be involved in AIDS progression by reactivating the latent HIV provirus and, subsequently, by eliminating such bacterial infection may contribute to the prevention of the AIDS development and transmission.

Keywords: HIV-1, HDAC, Epigenetics, Butyric acid, Histone

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) is a causative agent of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and the extent of its replication or its viral load in vivo is well correlated with the rate of disease progression. The current protocol of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) consisting of combinations of antiretroviral agents targeting different steps of the virus life cycle can efficiently decrease the HIV-1 load to below the limit of detection, thus reducing mortality due to HIV-1 infection [1, 2]. However, this therapeutic strategy is often hampered because of the presence of quiescent HIV-1 reservoirs and the emergence of drug-resistant viral clones [2, 3]. In fact, for many HIV-infected patients, latently infected cells persist over the long term and harbor integrated proviruses capable of reseeding virions [1–3]. Thus, the ability of HIV-1 to establish latent infection is a crucial characteristic in causing AIDS. Therefore, further elucidation of the molecular mechanism involved in maintenance of HIV latency and its breakdown should facilitate the development of a preventive measure and a novel therapy against clinical development of AIDS.

It has been well established that extracellular stimuli such as actions of proinflammatory cytokines and co-infection of other microbes play major roles in the pathogenetic progression of HIV infection. For example, we and others have reported that proinflammatory cytokines and coinfection with other pathogens, such as mycobacterium, HTLV-1, and herpesviruses, induce viral reactivation from the latently infected cells [4–7]. It has been repeatedly reported that individuals with dual microbial infection in addition to HIV-1 could accelerate AIDS development [4, 5].

Importantly, recent evidence indicates that gut and vaginal cavities are the major site of HIV-1 replication as well as its replication [8–11]. For example, it has been demonstrated that gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) is a major site of HIV replication, and that CD4 + T-cells in GALT are considered to be the primary target of the virus [9, 12]. During the subsequent period of chronic HIV infection, loss of GALT integrity and impairment of the gut mucosal barrier have been shown to be associated with the microbial translocation [13, 14]. Although this phenomenon was previously considered to be attributable to bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [13], many other studies have clarified that LPS from bacteria of gut flora could not activate HIV-1 replication in CD4 + T lymphocyte and macrophage/monocyte cell lines [12, 15, 16]. Thus, critical factors involved in the HIV reactivation in gut and vagina have not yet been identified.

A new clue has come from our recent observations with periodontogenic bacteria, Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis) [17]. P. gingivalis is known to produce high amounts of butyric acid that inhibits histone deacetylases (HDACs) [18, 19]. We found that the culture supernatant of P. gingivalis could efficiently reactivate the latently infected HIV-1 concomitantly with the induction of Lys-acetylation of histone H3 and H4 proteins [17]. Among various short chain fatty acid (SCFA) products of this bacterium, only butyric acid exhibited such activity [17]. Others [1, 3, 20] have demonstrated that the epigenetic regulation of latent HIV-1 provirus is exerted via post-translational modification of nucleosomal histone proteins, such as by acetylation and methylation.

Knowing that such interactions of certain micro-organisms and latent HIV could positively control the efficiency of viral replication, there is an urgent need to clarify the spectrum of such microbial infections that could control the epigenetic status of HIV-1 transcription. In fact, there are a number of resident bacteria, other than P. gingivalis, that have been shown to produce butyrate during their anaerobic life-cycle [18, 21–24]. In this study, we have attempted to comprehensively examine the human resident butyric acid-producing bacteria from various tissues for their effects on the reactivation of latent HIV-1.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and HIV-1 latently infected human cell lines

Human CD4 + T lymphocyte and macrophage/monocyte cell lines harboring replication-competent latent HIV-1, including ACH-2 and OM10.1, respectively, were obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (NIAID, NIH, MD). These cell lines are the most studied models of post-integration latency [25–30]. ACH-2 is a chronically HIV-1-infected T cell line derived from the parental cell line A3.01, and is defective for the Tat–TAR axis of viral transcriptional activation by Tat, but responsive to cytokine-mediated induction of HIV-1 transcription through a host transcription factor, NF-κB [26]. OM10.1 is a chronically HIV-1-infected cell line derived from HL-60 myelomonocytic leukemic cell line containing a single integrated copy of HIV-1LAV provirus with intact Tat–TAR axis [25]. These cells were maintained at 37°C in RPMI 1640 (Sigma) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma). To maintain the latency of the HIV-1 in ACH-2 and OM10.1, 20 μM AZT (Sigma) was added in the culture medium and excluded prior to the experiments. These cells (1.0 × 106 cells/2.0 ml well) were treated with bacterial culture supernatants or butyric acid (WAKO, Osaka, Japan). The HeLa cells were grown at 37°C in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Sigma) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum.

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Bacteria examined in this study include oral bacteria: Porphyromonas gingivalis (FDC381), Fusobacterium nucleatum (ATCC 25586), Fusobacterium nucleatum (ATCC 23726), Prevotella intermedia (ATCC 25611), Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Y4), Capnocytophaga gingivalis (JCM 12953), Streptococcus salivarius (JCM 5707), Streptococcus anginosus (JCM 12993), Actinomyces naeslundii (JCM 8349) and Pseudoramibacter alactolyticus (JCM 6480); gut bacteria: Clostridium difficile (JCM 1296), Clostridium butyricum (JCM 1391), Clostridium cochlearium (JCM 1396), Eubacterium multiforme (JCM 6484), and Campirobacter jejuni subsp. jejuni (JCM 2013); and vaginal bacteria: Anaerococcus tetradius (JCM 1964), Anaerococcus vaginalis (JCM 8138), Peptoniphilus asaccharolyticus (JCM 8143), and Anaerococcus lactolyticus (JCM 8140). All bacterial cultures were maintained in the same brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (DIFCO Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 5 μg/ml hemin, and 0.4 μg/ml menadione in an anaerobic culture system (Model 1024;Forma Scientific, Marietta, OH, USA) for 48 h. The supernatant was then collected by centrifugation at 7,800g for 40 min in 4°C to remove the bacteria and then filter-sterilized through a 0.22-μm pore-size membrane filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The resulting supernatants were used at a 1:5–1:10 dilution (50-100 μl/ml of cell culture medium).

Quantitation of short chain fatty acids (SCFA)

The experimental procedures for SCFA determinations in culture supernatants of various bacteria have been reported previously [17]. Briefly, 1 ml of culture filtrate was acidified by adding 2.0 μl of phosphoric acid followed by addition of 2.0 ml acetonitrile. After centrifugation to precipitate peptides, the supernatant was injected into a gas chromatography column to detect SCFAs (Shimadzu GC-2010). The SCFAs were then separated by a Free Fatty Acid Phase capillary column (15 m long, 0.32 mm inner diameter, and 0.25 μm film thickness). Column oven temperature was programmed from 70 to 200°C at a rate of 10°C/min, and a flame ionization detector was used to measure SCFA concentrations.

Immunoblot assay

The experimental procedures for immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were performed as follows [17]: the cells were harvested with lysis buffer [25 mM HEPES–NaOH (pH 7.9), 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.3% NP-40, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride], the proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond-C; Amersham). To detect HIV-1 proteins, the cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting and reacted with collected sera from AIDS patients. In order to evaluate the level of histone acetylation, cells were treated with the lysis buffer described above, and the cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-acetylated (Ac)-H3 (Upstate Biotechnology). The nuclear protein proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) was used as an internal control, indicating that the similar amounts of nuclear proteins were analyzed [31].

Luciferase assay

The luciferase expression plasmid under the transcriptional control of HIV-1 LTR, CD12-luc (containing the HIV-1 LTR U3 and R) has been previously reported [28]. Briefly, HeLa cells (1.5 × 105 cells/1 ml well) cultured in 12-well plates were transfected using Fugene-6 transfection reagent (Roche). For the internal control, we employed pRL-TK expressing Renilla luciferase under the control of constitutive thymidine kinase promoter. The transfected cells were harvested and the extracts were subjected to luciferase assay using the Dual-Luciferase Assay System™ (Promega). All the experiments were carried out in triplicate, and the data were presented as the fold increase in luciferase activities (means ± SD) relative to the control of three independent transfections.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

ChIP assay was performed according to the manufacture’s protocol (Upstate Biotechnology) with some modifications as previously described [27, 28]. Briefly, cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, washed twice with ice-cold PBS, and lysed for 10 min at 2 × 106 cells in 200 μl of SDS lysis buffer. The cross-linked chromatin was sheared by sonication 13 times for 10 s at one-third of the maximum power of microson XL sonicator (Wakenyaku, Kyoto, Japan) with 20 s cooling on ice between each pulse. Cross-linked and released chromatin fractions were pre-cleared with salmon sperm DNA and protein A-agarose beads for 1 h, followed by immunoprecipitation with the desired antibodies overnight at 4°C. The immunoprecipitates were sequentially washed once with lysis buffer, twice with high salt buffer, twice with low salt buffer, and twice with TE buffer. After the wash, immune complexes were collected with salmon sperm DNA and protein A-agarose beads at room temperature for 1 h, and extracted with 1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3. The eluted samples were reverse cross-linked by proteinase K at 45°C for 1 h and treated with RNase at 37°C for 1 h. DNA was recovered by phenol/chloroform and chloroform extractions, and ethanol precipitation. Finally, DNA was dissolved in 30 μl of TE buffer and subjected to PCR. The precipitated DNA was analyzed by PCR (31–33 cycles) with Taq Mastermix and primers for HIV-1 LTR (–176 to +61; forward: 5′-CGA GAC CTG CAT CCG GAG TA-3′, and reverse: 5′-AGT TTT ATT GAG GCT TAA GC-3′). For each reaction, 10% of the recovered DNA was used as an input control.

Measurement of viral p24 antigen

The p24 antigen level in the cell culture supernatant was measured by a p24 antigen capture ELISA assay using a commercial kit (RETRO-TEK HIV-1 p24 Antigen ELISA kit; Zepto Metrix , Buffalo, NY, USA) [28, 32].

Results

Effects of culture supernatant of various organ bacteria on the reactivation of latent HIV-1

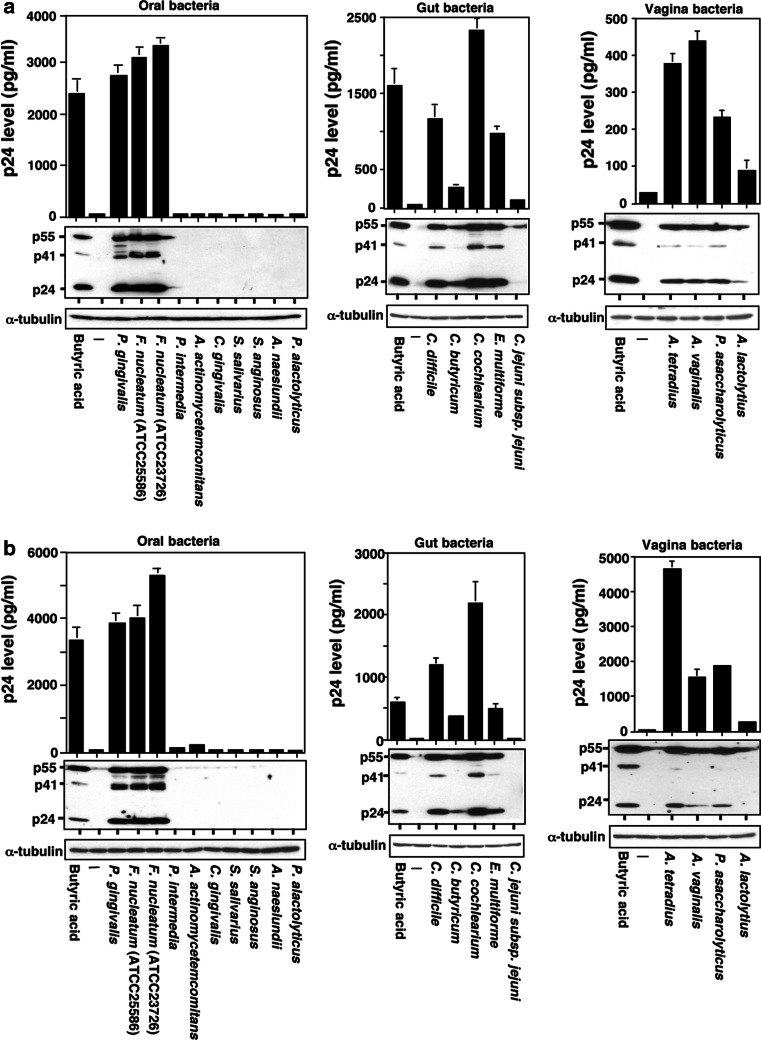

Since there are a number of resident bacteria that are known to produce butyrate during their anaerobic lifecycle in the oral cavity, gut, and vagina [18, 21–24], we have examined the effects of culture supernatants of bacteria obtained from these organs on HIV-1 replication from latently infected cells. In order to fix the culture conditions, the same culture media were utilized for cultivation of each bacteria after 48 h of incubation. Table 1 shows SCFA concentrations in the culture supernatant of bacteria obtained from the oral cavity, gut and vagina flora. In Fig. 1, these culture media were added at 1:10 ratio to the cell culture media of ACH-2 and OM10.1 cells as previously reported [17]. These cells were incubated for additional 48 h, and the cell culture media were collected to determine the viral p24 antigen concentration. The culture media from two different strains of butyrate-producing periodontogenic bacteria Fusobacterium. nucleotum, ATCC25586 and ATCC23726 strains, as well as P. gingivalis, substantially induced HIV-1 replication from the HIV-1 latently infected cells (Fig. 1, left panels). The extent of HIV-1 production were much higher even than the positive control with 2.0 mM butyric acid. As demonstrated with western blot analysis of cellular proteins (Fig. 1a, b, lower panels), induced production of various viral proteins was clearly detected in both cell lines. The SCFA measurement of F. nucleatum culture supernatant revealed that it contained butyric acids in high concentrations (from 27.4 to 33.8 mM) (Table 1). However, the culture supernatant of other periodontopathic bacteria, including Prevotella intermedia, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Capnocytophaga gingivalis, Actinomyces naeslundii, Pseudoramibacter alactolyticus, and two dental caries-causing Gram-positive bacteria, Streptococcus salivarius, and Streptococcus anginosus, lacking the ability to produce butyric acid, failed to elicit HIV-1 reactivation (Fig. 1; Table 1). No other SCFA appeared to induce HIV-1 reactivation as demonstrated previously [17].

Table 1.

Concentration of SCFA in culture supernatant of each bacterial strain

| Culture supernatants | SCFA levels (mM)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Propionic | Isobutyric | Acetic | Isovaleric | Butyric | |

| Oral | |||||

| Porphyromonas gingivalis ATCC33277 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 5.6 ± 0.1 | 11.0 ± 0.6 | 14.3 ± 0.3 | 27.4 ± 0.7 |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum ATCC25586 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | ND | 9.7 ± 0.5 | ND | 31.1 ± 1.1 |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum ATCC23726 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | ND | 10.1 ± 0.5 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 33.8 ± 1.2 |

| Prevotella intermedia ATCC25611 | ND | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 16.6 ± 0.9 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans Y4 | ND | ND | 13.2 ± 0.8 | ND | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| Capnocytophaga gingivalis JCM 12953 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | ND | 11.8 ± 1.5 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | ND |

| Streptococcus salivarius JCM 5707 | ND | ND | 4.8 ± 0.2 | ND | ND |

| Streptococcus anginosus JCM 12993 | ND | ND | 5.2 ± 0.1 | ND | ND |

| Actinomyces naeslundii JCM 8349 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | ND | 9.1 ± 0.6 | ND | ND |

| Pseudoramibacter alactolyticus JCM 6480 | ND | ND | 5.6 ± 0.4 | ND | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| Gut | |||||

| Clostridium difficile JCM 1296 | 0.8 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 23.7 ± 0.7 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 8.4 ± 0.2 |

| Clostridium butyricum JCM 1391 | ND | ND | 8.8 ± 0.1 | ND | 7.1 ± 0.1 |

| Clostridium cochlearium JCM 1396 | 1.2 ± 0.0 | ND | 10.1 ± 0.2 | ND | 27.3 ± 0.6 |

| Eubacterium multiforme JCM 6484 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | ND | 19.5 ± 0.4 | ND | 15.2 ± 0.3 |

| Campylobacter jejuni subsp. Jejuni JCM 2013 | ND | ND | 6.2 ± 0.4 | ND | ND |

| Vagina | |||||

| Anaerococcus tetradius JCM 1964 | ND | ND | 0.6 ± 0.1 | ND | 11.5 ± 0.1 |

| Anaerococcus vaginalis JCM 8138 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | ND | 0.8 ± 0.0 | ND | 7.4 ± 0.3 |

| Peptoniphilus asaccharolyticus JCM 8143 | 5.2 ± 0.0 | ND | 18.5 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 8.7 ± 0.0 |

| Anaerococcus lactolyticus JCM 8140 | ND | ND | 2.6 ± 0.3 | ND | 4.2 ± 0.6 |

ND not detectable (<0.1 mM)

aEach measurement was based on the results of three independent experiments; result are means ± SD

Fig. 1.

Effects of bacterial culture supernatants from various organs on the reactivation of latent HIV-1 induction of HIV-1 from latently infected cell lines with the culture supernatant of butyric acid-producing bacteria from oral, gut and vaginal cavities. Latent HIV-1-infected ACH-2 (a) and OM10.1 (b) cells were incubated with or without culture supernatants of commensal bacteria obtained from various tissues (100 μl/ml, i.e., 10% v/v) or butyric acid (2 mM) for 48 h. The cell culture supernatants were analyzed for p24 antigen levels by ELISA (upper panel). Experiments were carried out in triplicate, and the mean and SD values (pg/ml) are indicated. Detection of various viral proteins in the cell lysate was performed by immunoblotting with collected sera of AIDS patients (lower panel). Control bacterial culture medium (BHI) was added as a control (-). Positions of HIV-1 proteins are indicated on the left. α-tubulin was used as an internal control

Considering that F. nucleatum also resides in the gut flora [21, 23] and gut is considered to be the major site of HIV-1 replication and transmission [8, 9, 11], we have examined the effects of other major gut flora bacteria producing butyric acid on HIV-1 reactivation. The culture supernatants collected from these gut bacteria, such as Clostridium and Eubacterium species, could similarly induce HIV-1 replication (Fig. 1, central panels). There was no such effect with the culture medium from non-butyrate-producing bacteria such as Campylobacter jejuni subsp. jejuni. However, it was noted that the concentrations of butyric acid in culture supernatants of C. difficile, C. butyricum, C. cochlearium, and E. maltiforme (8.4, 7.1, 27.3, and 15.2 mM, respectably) did not completely correlate with the extents of HIV-1 reactivation. Whereas the culture supernatant of C. difficile induced HIV-1 replication a little more than E. cochlearium, the butyric acid content detected in the culture medium of C. difficile was slightly less.

It is previously known that some resident bacteria in vaginal mucous membrane produce butyric acid [22, 24]. In fact, we detected production of significant amounts of butyric acid from Anaerococcus tetradius, Anaerococcus vaginalis, Peptoniphilus asaccharolyticus, and Anaerococcus lactolyticus (Table 1). The concentrations of butyric acid in culture supernatants of four vaginal bacteria were 4.2–11.5 mM. The effects of these culture media on the HIV-1 replication from latently infected cells are demonstrated in Fig. 1 (right panels). The culture supernatants of these butyric acid-producing vaginal bacteria could reactivate the HIV-1 replication from the latenty infected cell lines.

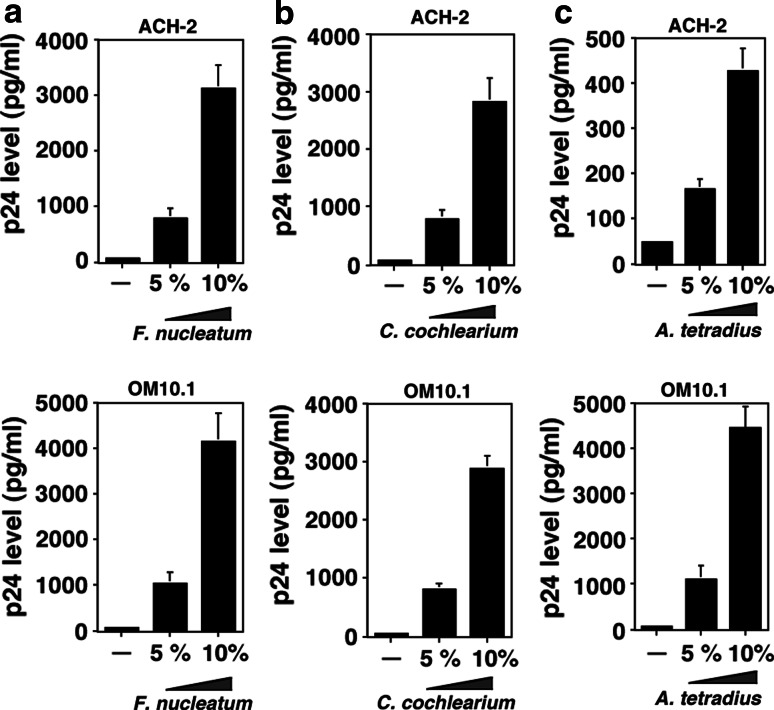

Dose-response induction of HIV-1 replication from latently infected cells by butyric acid-producing bacteria

In order to clarify the cause and effect relationships between the bacterial cultures and the extents of HIV-1 viral production from the latently infected cells, we examined the dose-dependent effect of culture supernatants from Fusobacterium nucleatum, Clostridium cochlearium, and Anaerococcus tetradius (representative butyrate-producing bacteria found in oral, gut, and vaginal cavities, respectively) at 0, 5, and 10%. As demonstrated in Fig. 2, dose-dependent induction of latent HIV-1 was observed by the treatment of cells with culture supernatants of these bacteria.

Fig. 2.

Dose-dependent induction of HIV-1 replication from latently infected cells by the culture supernatant of anaerobic bacteria obtained from oral cavity, gut, and vagina. Induction of HIV-1 replication from latently infected cells by the culture supernatant of butyric acid-producing bacteria from Fusobacterium nucleatum (a), Clostridium cochlearium (b), and Anaerococcus tetradius (c) that represent oral cavity, gut, and vagina, respectively. ACH-2 and OM10.1 cells were incubated with the bacterial culture supernatant at 50 (5% v/v) and 100 (10% v/v) μl/ml for 48 h. The determination of p24 antigen levels by ELISA was carried out as in Fig. 1. Each data point represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments

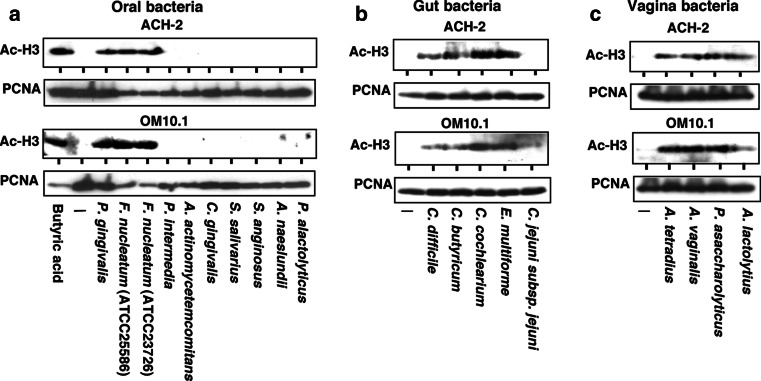

Hyperacetylation of histones by butyric acid contained in the bacterial culture media

Butyric acid is known to inhibit the enzymatic activity of HDAC by directly competing with the HDAC substrate at the catalytic center of the enzyme [19], thus it could reactivate the suppressed chromatin and induce transcription of various “silenced” genes including the latent HIV-1 provirus [30, 33]. In Fig. 3, we examined the effects of culture supernatant of each bacterial strain on the histone accetylation in HIV-1 latently infected cells examined. The extents of histone acetylation were assessed by western blotting using specific antibodies against the acetylated form of H3 histone in the cell extract prepared from ACH-2 to OM10.1 cells. As demonstrated in Fig. 3, the extents of acetylated histone H3 proteins (Ac-H3) were well correlated with the contents of butyric acid present in each bacterial culture supernatant.

Fig. 3.

Induction of histone hyperacetylation by the culture supernatant of butyric acid-producing bacteria. Induction of histone acetylation by the culture supernatant of butyric acid-producing bacteria from oral cavity (a), gut flora (b), and vagina (c). ACH-2 and OM10.1 cells were incubated with the indicated sample for 24 h and the cell lysate was analyzed for the histone acetylation by immunoblotting using specific antibody against acetylated histone 3 (Ac-H3). The nuclear protein PCNA was used as an internal control

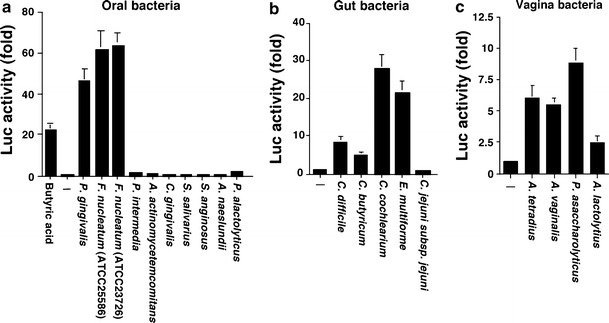

We then examined the effects of these bacterial culture supernatants on the level of gene expression from the HIV-1 LTR using transient luciferase assay [17]. As demonstrated in Fig. 4, the butyric acid-containing bacterial culture could significantly stimulate gene expression from HIV-1 LTR. In contrast, the culture supernatants of the bacteria not producing butyric acid failed to induce HIV-1 gene expression. These results suggested that the positive effect of culture supernatants from butyrate- producing bacteria on the reactivation of HIV-1 replication is exerted at the transcriptional level. The extents of induction of gene expression from HIV-1 LTR were well correlated with the amounts of butyric acid contained in each bacterial culture.

Fig. 4.

Transient luciferase assay showing that the positive effects of bacterial culture supernatant on HIV-1 replication were exerted at the transcriptional level. Transcriptional activation from the HIV-1 LTR by the culture supernatant of butyric acid-producing bacteria from oral cavity (a), gut flora (b), and vagina (c). HIV-1 luc reporter construct, expressing luciferase gene under the control of HIV-1 LTR, was transfected into HeLa cells, incubated for 24 h and stimulated with either culture supernatant of various bacteria (100 μl/ml) or butyric acid (1 mM) for additional 24 h. All the experiments were carried out in triplicate, and the data were presented as the fold increase in luciferase activities (means ± SD) relative to the control of three independent transfections

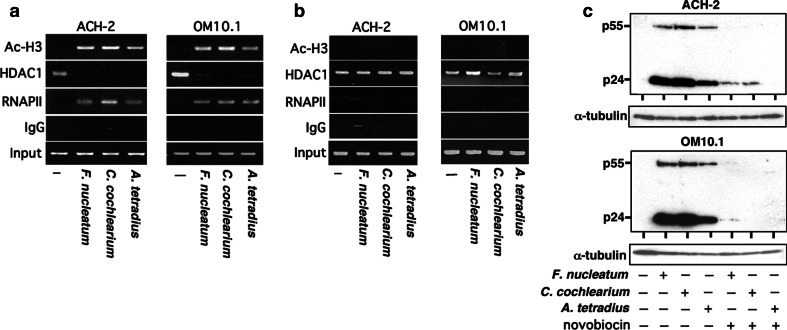

Butyric acid produced from bacteria facilitates HIV-1 reactivation via chromatin remodeling

As demonstrated above, we found that culture supernatants of various butyric acid-producing bacteria could induce histone acetylation and activate viral replication from the latently infected cells. We also showed that these effects were exerted at the step of transcription from the HIV-1 LTR. In order to further explore the dynamic recruitment of various transcription factors involved in HIV-1 transcription, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay as demonstrated in Fig. 5a. As revealed by the amounts of acetylated histone H3 (“Ac-H3”) recruited to the promoter region (from 176 to +61) of HIV-1 proviral DNA, we found that the amounts of histone acetylation were greatly augmented by the treatment of cells with culture supernatants of F. nucleatum, C. cochlearium, and A. tetradius (representative butyrate-producing bacteria found in oral, gut, and vaginal cavities, respectively). RNA polymerase II (“RNAPII”) was recruited to the vicinity of HIV-1 proviral promoter, where the transcriptional co-repressor HDAC1 was dissociated. In addition, when the culture supernatant was extensively heated at 80°C for 96 h in the presence of helium gas [17] to remove SCFA, these activities were lost (Fig. 5b). These findings indicate that the acetylation of H3 histone and ability of HIV-1 induction from latently infected cells is ascribable to butyric acid contained in the bacterial culture supernatant.

Fig. 5.

Recruitment of the acetylated histone H3 and the dependence of HIV-1 reactivation by bacterial culture supernatant on chromatin remodeling. a, b Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays detecting recruitment of acetylated histone H3 and RNAPII, and dissociation of HDAC1 on the proviral HIV-1 LTR DNA in ACH-2 and OM10.1 cells. Cells were either untreated or treated with culture supernatant of representative butyric acid-producing bacteria (100 μl/ml) for 1 h, the cell lysate was prepared and subjected to ChIP assays as described in “Materials and methods”. The bacterial culture supernatants were either heat-treated at 80°C for 96 h (b) or not (a). Note that, after the heat treatment,there was no detectable acetylation of histone H3 or recruitment of RNA polymerase II (RNAPII). The antibodies used in the ChIP assays were as indicated on the left. Input DNA (Input) represents 1.0% of the total input chromatin DNA and was used as a positive control. The immunoprecipitation with normal rabbit IgG was served as a negative control. c Abolishment of HIV-1 reactivation by novobiocin. ACH-2 and OM10.1 cells were pretreated with a topoisomerase II inhibitor, novobiocin (200 μg/ml). After 1 h of pretreatment, cells were stimulated with culture supernatant of various butyric acid-producing bacteria (100 μl/ml), incubated for an additional 48 h and the viral proteins were detected as in Fig. 1. Note that no effect was observed on the expression level of internal control such as α-tubulin

In addition, we examined whether the observed effects shown in Fig. 5a could be attributable to chromatin remodeling by using novobiocin, which is a specific and potent inhibitor of topoisomerase II responsible for the structural reorganization of nuclear chromatin, thus remodeling of nucleosomal chromatin [34, 35]. In Fig. 5c, we examined whether the activity of butyrate-containing bacterial culture could be affected by novobiocin. We found that the activity of such bacterial culture was totally abolished by novobiocin, suggesting that acetylation of H3 histone and recruitment of RNAII is associated with chromatin remodeling.

Discussion

Interactions between host and microbes often occur at the mucous membrane such as in the oral, gastrointestinal and vaginal cavities. The balance between host defense system and microbial attack is usually well maintained. However, there are many occasions when this balance is perturbed, culminating in the initiation of pathological processes. In case of HIV-1 that infects host cells and persists for many years, recent findings indicate that gut and vagina are the major sites of HIV-1 replication and transmission, and serve as sites for viral persistence [8–11]. Although bacterial LPS was initially thought to be responsible for the activation of viral replication [13], the subsequent evidence and experimental explorations did not support its role in augmenting viral replication from the latently infected cells [12, 15–17]. In this regard, we examined the role of bacterial metabolite butyric acid often produced by anaerobic bacteria during the anaerobic glycolysis [18, 21–23, 36], and found that treatment of cell lines harboring the latent HIV-1 with bacterial culture supernatant containing butyric acid could significantly upregulate HIV-1 gene expression and induce viral replication from the latency [17].

In the present study, we confirmed that the viral latency was effectively broken down by butyrate-containing bacterial culture and obtained novel evidence that not only such bacteria from oral cavity but those from gut and vaginal cavities could also exert essentially the same effects. The cell lines used in this study, ACH-2 and OM10.1, contain integrated HIV-1 provirus that is replication competent but expresses little viral mRNA, presumably due to a block at the step of transcriptional initiation [25, 26], which is similar to the virus-carrying cells in the HIV-1-infected individuals [1, 3]. We have demonstrated that histone H3 proteins in the vicinity of HIV-1 proviral DNA of these cells are deacetylated because of HDACs recruitment [27, 37–40]; however, acetylation of these histones by HDAC inhibition readily initiated viral transcription and its replication consistent with previous studies [29, 30, 32, 33, 41].

It is well established that hypoacetylation mediated by HDAC is correlated with transcriptional repression such as by LBP1/YY1 complex, p50 homodimer, and C-promoter binding factor [37–40], whereas hyperacetylation of core histone proteins adjacent to the HIV-1 proviral DNA is well correlated with its transcriptional activation [1, 20, 30]. We previously reported that activator protein-4 (AP-4) acts as a transcriptional repressor by recruiting HDAC molecules and is involved in the maintenance of viral latency [27], although no confirmatory evidence has been published using clinical materials. However, these findings indicate the involvement of HDAC activity in the maintenance of HIV latency and suggest the causal link between HDAC inhibition and the breakdown of viral latency.

Our present findings suggest that interaction between co-infected microbes such as butyric acid-producing bacteria and cells harboring latently infected HIV-1 located at the specific anatomical sites may determine the outcome of HIV-1 infection by modulating the rate of virus production. Regarding HIV-1 infection in the gut, GALT is known to be an important site for HIV-1 replication and pathogenesis. In fact, loss of GALT integrity [13, 14, 42] has often been reported in HIV-1-infected individuals. Moreover, butyrate-producing anaerobic bacteria including Fusobacterium nucleatum are often found in oral, gut and vaginal cavities where HIV-1 transmission frequently occurs [21, 23, 43]. Thus, our present findings have clinical as well as virological relevance.

In addition, some anaerobic bacteria found in the vaginal mucous membrane, such as A. tetradius, A. vaginalis, P. asaccharolyticus, and A. lactolyticus, could induce HIV-1 replication, while in addition it is known that HIV-1 infection is often associated with abnormal vaginal flora morphology and bacterial vaginosis [10, 44, 45]. Other studies suggest that bacterial vaginosis might be associated with increased HIV-1 replication and its infectivity [44–46]. Interestingly, Spiegel et al. [45] demonstrated the increase of butyrate, succinate, acetate and propionate, and the decrease of lactic acid in nonspecific vaginitis. They ascribed Peptococcus (Anaerococcus) bacterial species to the production of butyric acid.

Our findings presented here demonstrate that butyric acid produced from F. nucleatum, C. cochlearium, and P. gingivalis could promote gene expression of the latent HIV-1, thus making co-infection of these anaerobic bacteria one of the risk factors for promoting AIDS progression. In fact, high concentrations of butyric acid, ranging from 2.6 to 30 mM, were detected in human intestinal and oral cavities [47–49]. Moreover, although butyric acid concentration in blood of individuals who harbor these butyrate-producing bacteria is remarkably low, significant concentrations of butyric acid were detected in urine from patients with AIDS and correlated with the disease progression [50]. Taken together, it is likely that infection of butyric acid-producing bacteria is involved in AIDS progression and causally related to the reactivation of the latent HIV-1 provirus. This would suggest that elimination of such bacterial infection may contribute in preventing the clinical development of AIDS among HIV-1-infected individuals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Marni Cueno for critical reading of the manuscript and expert language editing, and Mr. Hiroaki togami for technical assistance. This work was supported by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, Dental Research Center, Nihon University School of Dentistry, Tokyo, the Takeda Science Foundation, the Waksman Foundation and “Strategic Research Base Development” Program for Private Universities from Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, 2010-2014 (S1001024).

Abbreviations

- AIDS

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- ChIP

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

- HDAC

Histone deacetylases

- HIV-1

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1

- LTR

Long terminal repeat

References

- 1.Colin L, Van Lint C. Molecular control of HIV-1 postintegration latency: implications for the development of new therapeutic strategies. Retrovirology. 2009;6:111. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pace MJ, Agosto L, Graf EH, O’Doherty U. HIV reservoirs and latency models. Virology. 2011;411:344–354. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marcello A. Latency: the hidden HIV-1 challenge. Retrovirology. 2006;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bafica A, Scanga CA, Schito M, Chaussabel D, Sher A. Influence of coinfecting pathogens on HIV expression: evidence for a role of Toll-like receptors. J Immunol. 2004;172:7229–7234. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mbopi-Keou FX, Belec L, Teo CG, Scully C, Porter SR. Synergism between HIV and other viruses in the mouth. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:416–424. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00317-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okamoto T, Akagi T, Shima H, Miwa M, Shimotohno K. Superinduction of trans-activation accounts for augmented human immunodeficiency virus replication in HTLV-I-transformed cells. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1987;78:1297–1301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okamoto T, Matsuyama T, Mori S, Hamamoto Y, Kobayashi N, et al. Augmentation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gene expression by tumor necrosis factor alpha. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1989;5:131–138. doi: 10.1089/aid.1989.5.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belyakov IM, Ahlers JD. Functional CD8 + CTLs in mucosal sites and HIV infection: moving forward toward a mucosal AIDS vaccine. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:574–585. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenchley JM, Douek DC. HIV infection and the gastrointestinal immune system. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1:23–30. doi: 10.1038/mi.2007.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta K, Klasse PJ. How do viral and host factors modulate the sexual transmission of HIV? Can transmission be blocked? PLoS Med. 2006;3:e79. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotler DP. HIV infection and the gastrointestinal tract. AIDS. 2005;19:107–117. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200501280-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kornbluth RS, Oh PS, Munis JR, Cleveland PH, Richman DD. Interferons and bacterial lipopolysaccharide protect macrophages from productive infection by human immunodeficiency virus in vitro. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1137–1151. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.3.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, et al. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Med. 2006;12:1365–1371. doi: 10.1038/nm1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haynes BF. Gut microbes out of control in HIV infection. Nat Med. 2006;12:1351–1352. doi: 10.1038/nm1206-1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernstein MS, Tong-Starksen SE, Locksley RM. Activation of human monocyte-derived macrophages with lipopolysaccharide decreases human immunodeficiency virus replication in vitro at the level of gene expression. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:540–545. doi: 10.1172/JCI115337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verani A, Scarlatti G, Comar M, Tresoldi E, Polo S, et al. C–C chemokines released by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated human macrophages suppress HIV-1 infection in both macrophages and T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;185:805–816. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.5.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imai K, Ochiai K, Okamoto T. Reactivation of latent HIV-1 infection by the periodontopathic bacterium Porphyromonas gingivalis involves histone modification. J Immunol. 2009;182:3688–3695. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurita-Ochiai T, Fukushima K, Ochiai K. Volatile fatty acids, metabolic by-products of periodontopathic bacteria, inhibit lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine production. J Dent Res. 1995;74:1367–1373. doi: 10.1177/00220345950740070801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riggs MG, Whittaker RG, Neumann JR, Ingram VM. n-Butyrate causes histone modification in HeLa and Friend erythroleukaemia cells. Nature. 1977;268:462–464. doi: 10.1038/268462a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bisgrove D, Lewinski M, Bushman F, Verdin E. Molecular mechanisms of HIV-1 proviral latency. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2005;3:805–814. doi: 10.1586/14787210.3.5.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macfarlane GT, Gibson GR (1995) Microbiological aspects of short chain fatty acid production in the large bowel. In: Cummings JH, Rombeau JL, Sakata T (eds) Physiological and clinical aspects of short-chain fatty acids. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 87–105

- 22.Murdoch DA. Gram-positive anaerobic cocci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:81–120. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pryde SE, Duncan SH, Hold GL, Stewart CS, Flint HJ. The microbiology of butyrate formation in the human colon. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;217:133–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson MJ, Hall V, Brazier J, Lewis MA. Evaluation of a phenotypic scheme for identification of the ‘butyrate-producing’ Peptostreptococcus species. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:747–751. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-8-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butera ST, Perez VL, Wu BY, Nabel GJ, Folks TM. Oscillation of the human immunodeficiency virus surface receptor is regulated by the state of viral activation in a CD4 + cell model of chronic infection. J Virol. 1991;65:4645–4653. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4645-4653.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Folks TM, Clouse KA, Justement J, Rabson A, Duh E, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha induces expression of human immunodeficiency virus in a chronically infected T-cell clone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2365–2368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.7.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imai K, Okamoto T. Transcriptional repression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by AP-4. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12495–12505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imai K, Togami H, Okamoto T. Involvement of histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) methyltransferase G9a in the maintenance of HIV-1 latency and its reactivation by BIX01294. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16538–16545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.103531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheridan PL, Mayall TP, Verdin E, Jones KA. Histone acetyltransferases regulate HIV-1 enhancer activity in vitro. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3327–3340. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verdin E, Paras P, Jr, Van Lint C. Chromatin disruption in the promoter of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 during transcriptional activation. EMBO J. 1993;12:3249–3259. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05994.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ando T, Kawabe T, Ohara H, Ducommun B, Itoh M, et al. Involvement of the interaction between p21 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen for the maintenance of G2/M arrest after DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42971–42977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106460200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Victoriano AF, Asamitsu K, Hibi Y, Imai K, Barzaga NG, et al. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in latently infected cells by a novel IkappaB kinase inhibitor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:547–555. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.2.547-555.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Lint C, Emiliani S, Ott M, Verdin E. Transcriptional activation and chromatin remodeling of the HIV-1 promoter in response to histone acetylation. EMBO J. 1996;15:1112–1120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu LF. DNA topoisomerase poisons as antitumor drugs. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58:351–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.002031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sorensen BS, Sinding J, Andersen AH, Alsner J, Jensen PB, et al. Mode of action of topoisomerase II-targeting agents at a specific DNA sequence. Uncoupling the DNA binding, cleavage and religation events. J Mol Biol. 1992;228:778–786. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90863-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Louis P, Flint HJ. Diversity, metabolism and microbial ecology of butyrate-producing bacteria from the human large intestine. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;294:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coull JJ, Romerio F, Sun JM, Volker JL, Galvin KM, et al. The human factors YY1 and LSF repress the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat via recruitment of histone deacetylase 1. J Virol. 2000;74:6790–6799. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.15.6790-6799.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang G, Espeseth A, Hazuda DJ, Margolis DM. c-Myc and Sp1 contribute to proviral latency by recruiting histone deacetylase 1 to the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 promoter. J Virol. 2007;81:10914–10923. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01208-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tyagi M, Karn J. CBF-1 promotes transcriptional silencing during the establishment of HIV-1 latency. EMBO J. 2007;26:4985–4995. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams SA, Chen LF, Kwon H, Ruiz-Jarabo CM, Verdin E, et al. NF-kappaB p50 promotes HIV latency through HDAC recruitment and repression of transcriptional initiation. EMBO J. 2006;25:139–149. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Golub EI, Li GR, Volsky DJ. Induction of dormant HIV-1 by sodium butyrate: involvement of the TATA box in the activation of the HIV-1 promoter. AIDS. 1991;5:663–668. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199106000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Douek DC. HIV disease: fallout from a mucosal catastrophe? Nat Immunol. 2006;7:235–239. doi: 10.1038/ni1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kantor B, Ma H, Webster-Cyriaque J, Monahan PE, Kafri T. Epigenetic activation of unintegrated HIV-1 genomes by gut-associated short chain fatty acids and its implications for HIV infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:18786–18791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905859106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sewankambo N, Gray RH, Wawer MJ, Paxton L, McNaim D, et al. HIV-1 infection associated with abnormal vaginal flora morphology and bacterial vaginosis. Lancet. 1997;350:546–550. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spiegel CA, Amsel R, Eschenbach D, Schoenknecht F, Holmes KK. Anaerobic bacteria in nonspecific vaginitis. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:601–607. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198009113031102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taha TE, Gray RH, Kumwenda NI, Hoover DR, Mtimavalye LA, et al. HIV infection and disturbances of vaginal flora during pregnancy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1999;20:52–59. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199901010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cummings JH, Pomare EW, Branch WJ, Naylor CP, Macfarlane GT. Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut. 1987;28:1221–1227. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.10.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mortensen PB, Clausen MR. Short-chain fatty acids in the human colon: relation to gastrointestinal health and disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1996;216:132–148. doi: 10.3109/00365529609094568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Niederman R, Buyle-Bodin Y, Lu BY, Robinson P, Naleway C. Short-chain carboxylic acid concentration in human gingival crevicular fluid. J Dent Res. 1997;76:575–579. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760010801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stein TP, Koerner B, Schluter MD, Leskiw MJ, Gaprindachvilli T, et al. Weight loss, the gut and the inflammatory response in aids patients. Cytokine. 1997;9:143–147. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1996.0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]