Abstract

The proteasome is a multi-catalytic protein complex whose primary function is the degradation of abnormal or foreign proteins. Upon exposure of cells to interferons (IFNs), the β1i/LMP2, β2i/MECL-1, and β5i/LMP7 subunits are induced and incorporated into newly synthesized immunoproteasomes (IP), which are thought to function solely as critical players in the optimization of the CD8+ T-cell response. However, the observation that IP are present in several non-immune tissues under normal conditions and/or following pathological events militates against the view that its role is limited to MHC class I presentation. In support of this concept, the recent use of genetic models deficient for β1i/LMP2, β2i/MECL-1, or β5i/LMP7 has uncovered unanticipated functions for IP in innate immunity and non-immune processes. Herein, we review recent data in an attempt to clarify the role of IP beyond MHC class I epitope presentation with emphasis on its involvement in the regulation of protein homeostasis, cell proliferation, and cytokine gene expression.

Keywords: Immunoproteasomes, Protein homeostasis, Cell proliferation, Cell signaling

Introduction

First discovered more than 30 years ago, proteasomes have since been the subject of intense investigations across the fields of molecular, cellular, and developmental biology. The 26S proteasome is a 2.5-MDa multi-protein complex responsible for degradation of poly-ubiquitylated proteins in eukaryotic cells. Structurally, it consists of a 670-kDa catalytic 20S core particle and at least one 900-kDa regulatory 19S subunit attached to one of the core end that recognizes and unfolds substrates prior to degradation. The 20S core particle is a 28-subunit barrel-like particle composed of two outer α-rings and two inner β-rings which are each made up of seven structurally similar α- and β-subunits, respectively [1, 2]. Importantly, three of the seven β subunits (i.e., β1, β2, and β5) are fully processed during assembly and maturation and expose their N-terminal threonine residues, which serve as catalytic nucleophiles for peptide bond hydrolysis [3]. These β1, β2 and β5 subunits are responsible for the three major enzymatic activities of the eukaryotic 20S proteasome by exhibiting caspase-like, tryptic-like, and chymotryptic-like activities, respectively. The 19S regulatory subunit serves as the gate into the interior of the 20S core protease. It can be divided into two sub-structures, namely the base and the lid. The base caps the α-ring of the 20S core complex and is composed of 6 ATPases (Rpt1-Rpt6) and 2 Rpn subunits (Rpn1 and Rpn2). The lid contains up to ten non-ATPase subunits and is responsible for recognition and binding of protein substrates through their poly-ubiquitin chains [4–6]. As one of the main protein-destroying apparatuses, the 26S proteasome is involved in the regulation and maintenance of many essential cellular processes including cell growth, cell differentiation, cell signaling, DNA repair, gene transcription, apoptosis, and the generation of antigenic peptides presented by major histocompatibility (MHC) class I cell surface molecules to CD8+ T cells [1, 7–9].

IP molecular structure and subunit composition

Two decades ago, an alternative form of proteasomes was observed in WEHI-3 cells treated with IFN-γ. Interestingly, it was originally referred to as a “low-molecular-weight polypeptide (LMP)” complex, as it distinguished itself from the so-far-described standard form of proteasome by exhibiting a reactivity for the so-called LMP antigens [10, 11]. Historically, the LMP antigens were identified as a set of approximately 20 proteins ranging from 20 to 30 kDa that “co-precipitate” with MHC class I molecules [12]. The term LMP was specifically used to discriminate these proteins from the MHC molecules, as they all were much smaller in molecular size when loaded on a two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Further studies have revealed that such ‘LMP complex’ was structurally very similar to the standard proteasome (SP) complex except for at least two proteins identified as β1i/LMP2 and β5i/LMP7 [11, 13–15]. Importantly, in contrast to the other proteasome genes, which are dispersed throughout the genome, the β1i/LMP2 and β5i/LMP7 genes are concentrated in the MHC class II region of the chromosome 6 (6p21.3) immediately upstream of each of the transporter-associated genes TAP-1 and TAP-2 [12, 16–18]. Like MHC class I and II cell-surface molecules, both of these two subunits are polymorphic (albeit to a lesser extent) and strongly inducible by the cytokine IFN-γ [17]. When expressed, β1i/LMP2 and β5i/LMP7 are incorporated into proteasomes in detriment of their homologous standard counterparts β1 and β5, respectively (originally designated X and Y), which are down-regulated by a post-transcriptional mechanism [19–22]. The observation that both β1i/LMP2 and β5i/LMP7 were encoded by MHC genes immediately stimulated interest in the possible function of these subunits in the regulation of the immune response by optimization of MHC class I-antigen processing. This possibility gained first support from in vitro digestion studies showing that incorporation of β1i/LMP2 and β5i/LMP7 qualitatively and quantitatively altered the set of peptides emerging from a 25-mer polypeptide containing the IE pp89 Ld-restricted YPHFMPTNL naturally processed dominant antigenic peptide [23]. Hence, to better reflect their potential function in the cellular immune response, it was proposed to rename such β1i/LMP2- and β5i/LMP7-positive complexes ‘immunoproteasomes’ [24]. A role for IP in the modulation of the pool of peptides available for MHC class I antigen presentation is also strengthened by biochemical data showing that β1i/LMP2 and β5i/LMP7 enhance substrate cleavage after basic and hydrophobic amino acid residues [25–27]. Besides, the critical involvement of these two inducible subunits in the improved generation of MHC class I ligands has been evidenced in β1i/LMP2- and β5i/LMP7-deficient mice [28, 29]. The absence of either β1i/LMP2 or β5i/LMP7 has also been reported to be frequently associated with impaired presentation of bacterial- or viral-derived epitopes to CD8+ cytotoxic T cells [30–32], supporting the notion that correct antigen processing requires the incorporation of these two inducible subunits into fully mature IP. A few years later, a third and last IFN-γ inducible abundant protein in IP was identified as β2i/MECL-1 and was found to replace the homologous standard subunit β2 [33, 34]. Unlike β1i/LMP2 and β5i/LMP7, β2i/MECL-1 is not linked to the MHC class II region and is encoded by a gene which is found on human chromosome 16 [35]. The contribution of β2i/MECL-1 together with β1i/LMP2 and β5i/LMP7 to the production of MHC class I epitopes has also been mostly documented in viral models [36, 37]. Since its discovery, the catalytic and peptide cleavage properties of the inducible subunits have been the main—if not the only—focus of a large number of studies all of which coming to the general conclusion that IP complexes are, in most instances, more efficient than SP in generating antigenic peptides.

Tissue expression, distribution, and regulation of IP

In immune cells

In line with the so-far-described role of the inducible subunits β1i/LMP2, β2i/MECL-1, and β5i/LMP7 in shaping the MHC class I-restricted peptide repertoire, it has been shown that the spleen has the highest IP expression and activity of any tissue [38]. This is in agreement with the observation that IP are primarily found in hematopoietic cells in vivo including professional antigen-presenting cells such as macrophages [39] and activated or resting B cells [40]. Likewise, and in contrast to most solid tumors, malignant cell lines of hematopoietic origin such as EBV-transformed B cells or multiple myeloma-derived cells are systematically enriched with the β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7, and/or β2i/MECL-1 subunits [41, 42]. Constitutive expression of IP has also been reported in monocyte-derived dendritic cells (DC), although there is disagreement with respect to its regulation in response to pathogens or inflammatory stimuli. Early reports argued that immature DC carry equal amounts of SP and IP, while mature DC contain only IP [43, 44]. Nonetheless, it was shown later that the relative abundance of the inducible subunits β1i/LMP2, β2i/MECL-1, and β5i/LMP7 was similar in both immature and mature DC [45, 46]. Other reports even described a down-regulation of the IP content in maturing DC following treatment with pro-inflammatory cytokines [47]. One can argue that some of the issues leading to confusion with respect to the IP expression profile in DC may be related to the lack of highly specific antibodies against the inducible subunits at the time the experiments were carried out. Recently, an interesting study re-evaluated the IP expression pattern in various cell types including DC by means of ELISA assays using specific monoclonal antibodies directed against each of the β1i/LMP2, β2i/MECL-1, and β5i/LMP7 subunits. In this work, the authors show that immature DC were mostly endowed with IP as well as with intermediate LMP7(β5i)-β1-β2 and LMP7(β5i)-LMP2(β1i)-β2 complexes whose levels remain unchanged following stimulation with either LPS or a combination of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and PGE2 [48]. In our hands, β1i/LMP2, β2i/MECL-1, and β5i/LMP7 were only inducible at the mRNA level following engagement of Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists such as LPS or Poly-IC through an IFN-β autocrine loop [49]. In agreement with the above-mentioned study, the increased transcription of the inducible subunits was not followed by a parallel rise in maturing DC at the protein level (Ebstein et al., unpublished observations). The unchanged β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7, and β2i/MECL-1 protein levels following maturation are surprising in light of the increased β1i/LMP2 and β5i/LMP7 levels in response to LPS and/or Poly-IC, as measured by quantitative real-time PCR. However, the finding may have several explanations, including increased breakdown of LMP2 (β1i)/LMP7 (β5i)/MECL-1 (β2i) in addition to increased synthesis. In any case, it is highly unlikely that the constitutive presence of IP in hematopoietic cells is the result of a persistent stimulation by pro-inflammatory cytokines in vivo, since these cells maintain their IP content in vitro in the absence of extra-cellular stimuli. The notion that the basal expression of the inducible subunits in these cells is independent of external signaling requirements is further supported by the observation that the spleen of IFN-γ-deficient mice exhibit similar levels of IP to wild-type mice [50]. The constitutive and basal expression of the inducible subunits may be explained by intracellular signaling mechanisms including a predominant unphosphorylated form of Stat1 in these cells. Indeed, it has been shown that unphosphorylated Stat1 binds IRF1 to form a complex which permanently occupies the GAS sequences of the LMP2 promoter to support transcription [51]. As part of spleen cells, it is generally thought that natural killer (NK) cells, basophils, or neutrophils express the inducible subunits in a constitutive way, although no or very little information is available in this regard.

In non-immune cells

As alluded to earlier, it was long assumed that most of the tissues of non-hematopoietic origin were normally devoid of IP, unless these tissues or those of their environment become confronted with immunological challenges, which ultimately lead to the up-regulation of each of the inducible subunits via autocrine or paracrine production of IFN-α/β or IFN-γ. Over the past few years, however, the classical paradigm of IP solely as means to an immunological end is becoming outdated, as an increasing number of studies have redefined IP expression in a wide array of non-immunological cells and organs (Table 1). This begins with the observation that the inducible subunit β5i/LMP7 is constitutively expressed in normal tissues including small intestinal epithelial cells [52], colon [53], liver [38, 54, 55], umbilical vein cells [56] as well as in placenta [57]. In addition, a fully matured IP containing all three subunits could also be purified from human kidney [58]. Noteworthy, in both colon and liver, LMP7 is accompanied by the up-regulation of the two other inducible subunits LMP2 and MECL-1 during the course of pathologies including Crohn’s disease [53] and cirrhosis [55], respectively, as a result of an alteration of the local inflammatory milieu. The nature of the stimulus leading to the basal and persistent expression of one or more of the three inducible subunits in these tissues under healthy conditions remains unclear. One could argue that such IP expression in vivo may depend on extra-cellular signals. Noteworthy, none of these cell types is a strong producer of IFN-γ, thereby excluding the possibility that the formation of IP is driven by permanent autocrine stimulation. It is more conceivable in this case that the prolonged expression of β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7, and/or β2i/MECL-1 in these tissues relies on the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines by neighboring cells such as resident macrophages and infiltrating T cells or NK cells, which secrete high levels of IFN-γ as well as infected fibroblasts producing type I IFN. However, the fact that the expression is sustained would imply a continuous secretion of IFN-γ by infiltrating DC or macrophages, making this possibility under non-pathological or non-inflammatory conditions very unlikely. Therefore, and as for hematopoietic cells, the constitutive expression of the IP subunits in these non-immune tissues may reflect a permanent activation of intracellular signaling pathways, rather than a response to changes in cytokine environment, although such notion remains to be formally addressed.

Table 1.

Tissue distribution of the inducible subunits β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7, and β2i/MECL-1 under normal conditions or following pathological events

| Tissue/cell type | Stimulus/disease | Constitutively expressed and/or induced subunits | Determined at | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat spleen | None | LMP2, LMP7, and MECL1 | Protein level | Noda et al. [38] |

| Human thymus | None | LMP2, LMP7, and MECL1 | Protein level | Oh et al. [121] |

| Human macrophages | None | LMP2 and LMP7 | Protein level | Haorah et al. [39] |

| Human B cells | None | LMP2 and LMP7 | Protein level | Frisan et al. [40] |

| Transformed B cells | NNS | LMP2 and LMP7 | Protein level | Arima et al. [78] |

| Human PBMC | Sjögren’s syndrome | LMP7 | mRNA level | Egerer et al. [122] |

| IgA nephropathy | LMP7 and MECL1 | mRNA level | Coppo et al. [123] | |

| Human monocytes | Atopic dermatitis | LMP7 | mRNA level | Nagata et al. [124] |

| Human monocyte-derived DC | LPS, CD40L | LMP2, LMP7, and MECL1 | Protein level | Macagno et al. [43] |

| MALP-2 | LMP2, LMP7, and MECL1 | Protein level | Link et al. [44] | |

| LPS, Poly-IC | LMP2, LMP7, and MECL1 | mRNA level | Ebstein et al. [49] | |

| None | LMP2, LMP7, and MECL1 | Protein level | Guillaume et al. [48] | |

| Mouse D1 DC cell line | None | LMP2, LMP7, and MECL1 | Protein level | Ossendorp et al. [46] |

| Human small intestine | None | LMP2 and MECL1 | Protein level | Visekruna et al. [125] |

| Mouse small intestine | None | LMP2, LMP7, and MECL1 | Protein level | Kuckelkorn et al. [126] |

| Human colon | None | LMP7 | Protein level | Visekruna et al. [53] |

| Crohn disease | LMP2 and MECL1 | Protein level | Visekruna et al. [52] | |

| Inflammation | LMP2 | Protein level | Fitzpatrick et al. [127] | |

| Human liver | None | LMP7 | Protein level | Visekruna et al. [125] |

| Mouse liver | LPS | LMP7 | Protein level | Seifert et al. [74] |

| Human liver | Cirrhosis, chronic liver disease | LMP2, LMP7 | Protein level | Vasuri et al. [55] |

| Human liver | Steatohepatitis | LMP2, LMP7, and MECL1 | Protein level | French et al. [77] |

| Rat liver | Refeeding following fasting | LMP2 and LMP7 | Protein level | Ushiama et al. [128] |

| None | LMP2, LMP7, and MECL1 | Protein level | Noda et al. [38] | |

| Mouse liver | DCC-induced MDB | LMP2, LMP7, and MECL1 | Protein level | Bardaf-Gorce et al. [129] |

| Human umbilical veins | None | LMP7 | mRNA level | Loukissa et al. [56] |

| Human placenta | None | LMP7 | mRNA level | Roby et al. [57] |

| Human kidney | None | LMP2, LMP7, and MECL1 | Protein level | Baldovino et al. [58] |

| Rat lung | None | LMP7 | Protein level | Noda et al. [38] |

| Mouse retina | Injury | LMP2 and LMP7 | Protein level | Ferrington et al. [61] |

| Human retina | Age-related macular degeneration | LMP2 and LMP7 | Protein level | Ethen et al. [130] |

| Mouse brain | EAE | LMP7 | Protein level | Seifert et al. [74] |

| Mouse brain | Injury | LMP2 and LMP7 | Protein level | Ferrington et al. [61] |

| Human brain | HIV Infection human | LMP2 | Protein level | Gelman et al. [131] |

| Glioblastoma human | LMP2 | Protein level | Piccinini et al. [62] | |

| Human neurons | Alzheimer disease | LMP7, LMP2 | Protein level | Mishto et al. [63] |

| LMP7, MECL1 | Protein level | Nijholt et al. [64] | ||

| Aging | LMP7, LMP2 | Protein level | Mishto et al. [63] | |

| Multiple sclerosis | LMP7, LMP2 | Protein level | Mishto et al. [132] | |

| Epilepsy | LMP7, LMP2 | Protein level | Mishto et al. [133] | |

| Mouse neurons | Huntington’s disease | LMP7, LMP2 | Protein level | Diaz-Hernandez et al. [65] |

| LMP7, LMP2 | Protein level | Diaz-Hernandez et al. [66] | ||

| Rat neurons | Aging | LMP7 | Protein level | Gavilan et al. [67] |

| Human muscle | Myofibrillar myopathy | LMP7, LMP2, and MECL1 | Protein level | Ferrer et al. [76] |

| Rat muscle | Aging | LMP7, LMP2 | Protein level | Husom et al. [134] |

| Human endothelial cells | NO | LMP7, LMP2 | Protein level | Kotamraju et al. [135] |

| Mouse ocular lens | None | LMP7, LMP2, and MECL1 | mRNA level | Singh et al. [59] |

| Human skin | JASL | LMP7(G197V) | Protein level | Kitamura et al. [79] |

| Mouse heart | Enterovirus (CVB3) | LMP7, LMP2 | Protein level | Opitz et al. [80] |

Tissue distribution of the inducible subunits β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7 and β2i/MECL-1 under normal conditions or following pathological events

Most surprisingly, IP has been reported to be found or induced in immune-privileged sites including the eye [59–61] and the brain [62], although the literature on the precise cellular distribution of the inducible subunits in these organs remains somehow conflicting (Table 1). In particular, the capacity of neurons to induce or to form IP is still a matter of debate. Earlier studies originally suggested that IP are absent in neurons under normal conditions but may be formed over the course of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer [63, 64] and Huntington [65, 66]. This notion is further supported by subsequent reports emphasizing that the increased expression of each of the inducible subunits in neurons is a classical feature of brain aging [63, 67, 68]. It was later shown that IP formation in the brain in response to infection with LCMV occurs in microglia cells but not in neurons [69]. In this work, Kremer and colleagues demonstrate that, although being induced at a transcriptional level, β1i/LMP2, β2i/MECL-1, and β5i/LMP7 accumulate as precursors in inflamed neurons without being incorporated into mature IP. The basis of these discrepancies is unclear and might in part be related to the nature of the stimulus and/or disease. For instance, because of the increased reactivity of microglia, astrocytes and innate immune cells of the brain that occurs during normal aging [70], it is argued that chronic neuroinflammation involving the continuous production of multiple cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, and TGF-β is the main underlying cause of IP induction in neurons over the course of neurodegenerative diseases. The inability of neurons to assemble the up-regulated β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7, and β2i/MECL-1 precursors into fully mature IP following LCMV infection is intriguing. Although the authors in this study did not find any substantial impairment of the expression level of the critical IP assembly factor POMP in these cells, these data suggest that neurons still lack other yet unidentified partners required for proper IP formation under LCMV infection. Alternatively, one could also argue that such defect may be seen as a unique feature of LCMV infection rather than a characteristic of neurons. In any case, the observation that IP are formed in neurons following chronic inflammation but not following LCMV infection suggests a role for the inducible subunits beyond MHC class I processing.

Functions of IP in innate immunity and non-immune processes

While classically linked to MHC class I antigen presentation, recent evidence from knockout mice and inhibition studies on the role of the β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7, and β2i/MECL-1 inducible subunits have substantially expanded the functional repertoire of IP. Indeed and as listed in Table 2, an involvement of these subunits has been described in unexpected cellular processes such as protein homeostasis, cell proliferation, and cell signaling (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of the so-far reported functions for the inducible subunits β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7, and β2i/MECL-1, which are not directly connected to MHC class I antigen processing

| Function | Cell type/tissue | Implicated subunit (s) | Shown in/by | Phenotype | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein homeostasis | Brain and liver | LMP2 | LMP2-/− mice | Increased level of protein oxidation | Ding et al. [93] |

| Endothelial cells | LMP2 and LMP7 | LMP2 and LMP7 antisense oligonucleotides | NO accumulation | Kotamraju et al. [135] | |

| Retina cells | MECL1 and LMP7 | MECL1−/− and LMP7−/− mice | Oxidation-induced cell death | Hussong et al. [60] | |

| MEF/brain/liver | LMP7 | LMP7−/− mice | Accumulation of oxidized and poly-ubiquitylated proteins | Seifert et al. [74] | |

| MEF | LMP2 | LMP2 siRNA | Accumulation of oxidized proteins | Pickering et al. [92] | |

| NNS fibroblasts | LMP7 | Endogenous expression of a PSMB8 (G201V) mutant | Accumulation of oxidized and poly-ubiquitylated proteins | Arima et al. [78] | |

| Transformed B cells | LMP7 | Endogenous expression of a PSMB8 (G197V) mutant | Accumulation of poly-ubiquitylated proteins | Kitamura et al. [79] | |

| Cardiomyocytes/heart muscle | LMP7 | LMP7−/− mice | Accumulation of oxidized and poly-ubiquitylated proteins | Opitz et al. [80] | |

| Cytokine production | BM-derived DC | LMP2 | LMP2−/− mice | Impaired production of IFN-α, IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α upon infection | Hensley et al. [113] |

| PBMC from patients with RA | LMP7 | LMP7-specific inhibitor (PR-957) | Decreased production of IL-23, IL-6 and TNF-α | Muchamuel et al. [114] | |

| Macrophages | LMP2, LMP7, and MECL1 | LMP2−/−, LMP7−/−, MECL1−/− and LMP7/MECL1−/− mice | Reduced NO levels following LPS stimulation | Reis et al. [117] | |

| Colon from mice with DSS-induced colitis | LMP7 | DSS-induced colitis in LMP7−/− mice | Reduced expression of inflammatory cytokines mediated by NF-κB | Schmidt et al. [82] | |

| LMP7 | LMP7-specific inhibitor (PR-957) | Impaired production of IL-23 and IL-1β | Basler et al. [81] | ||

| LMP2, MECL1, and LMP7 | LMP2−/−, MECL1−/− and LMP7−/− mice | Impaired induction of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-23 and IL-17. | Basler et al. [81] | ||

| Serum from patients with NNS | LMP7 | Missense mutation G201V | Increased production of IL-6 | Arima et al. [78] | |

| Skin from patients with NNS | LMP7 | Missense mutation G197V | Increased production of IL-6 | Kitamura et al. [79] | |

| Blood from patients with CANDLE syndrome | LMP7 | Nonsense mutation C135X | Increased induction of IP-10, MCP-1 and RANTES | Liu et al. [118] | |

| Cell proliferation | T cells | MECL1 and LMP7 | MECL1−/− and LMP7−/− mice | Hyperproliferation in vitro in response to mitogens | Caudill et al. [105] |

| MECL1 | MECL1−/− mice | Enhanced CD4/CD8 T-cell ratios | Zaiss et al. [100] | ||

| LMP2, MECL1, and LMP7 | LMP2−/−, MECL1−/− and LMP7−/− mice | Hypoproliferation in WT hosts | Moebius et al. [102] | ||

| Multiple myeloma cells | LMP2 | LMP2-specific inhibitor (IPSI-001) | Decreased cell proliferation | Kuhn et al. [103] | |

| LMP7 | LMP7-specific inhibitor (PR-924) | Decreased cell growth | Singh et al. [104] | ||

| Cardiac muscle regulation | Myocytes | LMP2 | LMP2−/− mice | Diabetic cardiomyopathy | Zu et al. [136] |

| Heart | LMP2 | LMP2−/− mice | Lower cardiac mass and heart rate | Cai et al. [137] | |

| Brain function | Brain | LMP2 | LMP2−/− mice | Increased degree of motor function | Martin et al. [138] |

| Vision transmission | Retina | MECL1 and LMP7 | MECL1−/− and LMP7−/− mice | Bipolar cell responses defects | Hussong et al. [139] |

| Apoptosis | Atherosclerotic lesion-derived cells | LMP7 | LMP7 siRNA | Increased sensitivity to apoptosis to IFN-γ | Yang et al. [110] |

List of the so-far-reported functions for the inducible subunits β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7, and β2i/MECL-1, which are not directly connected to MHC class I antigen processing

A role for IP in the disposal of accumulating damaged proteins upon inflammation and/or cell stress

By removing abnormal proteins or proteins that are no longer needed in the cell, proteasomes play an essential role in the regulation of cellular proteostasis. As such, aberrant proteins often tend to aggregate when proteasome function is impaired, thereby leading to intracellular accumulation of large ubiquitin-positive structures in the cytoplasm. Although prolonged protein aggregation is a hallmark of aging or age-related diseases such as Alzheimer [63, 64], transient protein aggregation is a physiological process that takes place in various cell types following cytokine stimulation or cell stress. This is particularly obvious in professional antigen-presenting cells including DC and macrophages whose maturation programs following microbial stimuli are characterized by a transient accumulation of large cytosolic ubiquitin aggregates (also referred to as DALIS for dendritic cell aggresome-like induced structures) [71, 72]. A similar tendency was observed in response to stress and starvation in non-immune cells including fibroblasts whose accumulating ubiquitin protein-conjugates in this case were referred to as aggresome-induced like structures (ALIS) to distinguish them from DALIS [73]. Importantly, both DALIS and ALIS require protein synthesis and it is assumed that their formation occurs as a consequence of excess levels of defective ribosomal products (DRiPs) that temporary exceed the degradation capacity of proteasomes. For many years, the respective roles of SP and IP in the degradation of DRiPs remained unclear and it is only recently that increasing evidence supports the concept that IP are more efficient than SP at eliminating damaged ubiquitylated cellular proteins that accumulate upon physiological and/or pathological stimuli. Indeed, we have recently shown that mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEF) from β5i/LMP7−/− mice are less prone than those of their wild-type counterparts in clearing ALIS following IFN-γ stimulation [74]. In this study, we demonstrate that the increased capacity of IP to cope with ALIS essentially relied on its higher ability to degrade K48-linked poly-ubiquitylated substrates, when compared to SP. Up to now, the mechanisms by which the incorporation of the inducible subunits allows IP to degrade ubiquitin substrates faster than SP are unclear and warrant further investigations. One possible explanation may be the increased chymotryptic activity observed following incorporation of β5i/LMP7. This, in turn, might be due to a conformational change that in a way favors the entry of poly-ubiquitylated substrates into the catalytic core, as previously suggested [75]. In any case, our findings point to an unexpected role for IP in the accelerated degradation of poly-ubiquitylated substrates, which implies that IP-expressing tissues are better protected from disruption of protein homeostasis than tissues endowed with SP.

The observation that DC and macrophages are enriched with the inducible subunits even at the immature stage is of high interest and does not necessarily reflect a predisposing role in the adaptive immune response by generating MHC class I peptides. Indeed, DC and macrophages establish the first line of defense against microbial pathogens and, as such, are frequently confronted with pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP), which initiate maturation and DALIS formation following their binding to Toll-like receptors. It is tempting to speculate that the constitutive presence of IP even before any stimulation allows these cells to rapidly cope with DALIS following activation. This notion is reinforced by the fact that DALIS are apparently cleared much faster in DC than ALIS in MEF, which need to up-regulate IP [71, 74]. In spite of the availability of numerous knockout models for the three inducible subunits, the role for IP in the removal of DALIS remains elusive and has to be formally addressed. The fundamental role of the IP in innate immunity by preserving protein homeostasis upon infection or insult is also strengthened by the fact that B and T cells, which have a very limited role in the generation of MHC class I epitopes, constitutively express β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7, and β2i/MECL-1. An increasing number of studies have documented a correlation between IP over-expression and a flurry of diseases characterized by accumulations of abnormal proteins including myofibrillar myopathy [76] or steatohepatitis [77]. It is conceivable that the increased expression of the inducible subunits over the course of such diseases reflects the permanent need of the damaged tissues to restore protein homeostasis. Supporting this notion, we recently showed that mice lacking β5i/LMP7 fail to clear protein aggregates that accumulate in the brain following induction of experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE) and in the liver in response to LPS [74]. Further evidence also includes the recent report of a missense mutation in the β5i/LMP7 gene (PSMB8) (G197V and G201V in the isoforms E1 and E2, respectively), which is associated with IP formation disturbance and concomitant increased accumulation of poly-ubiquitylated proteins in patients with Nakajo-Nishimura syndrome (NNS) (also refereed as to Japanese auto-inflammatory syndrome with lipodystrophy, JASL) [78, 79]. Similar observations were made in other experimental diseases including viral models, whereby infection of β5i/LMP7−/− mice with coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) results in an exacerbated myocarditis, which occurs as a consequence of a lack of protection against CVB3-mediated protein damage [80]. These studies appear to be in conflict with earlier reports showing that IP deficiency is associated with attenuation of disease progression in an experimental colitis auto-immune model [81, 82]. These contrasting data suggest that, depending on both disease model and tissue-specificity, IP can exert either beneficial or negative effects.

Binding of PAMP to TLR stimulates not only the release of specific cytokines by DC and/or macrophages but also reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO) [83]. Due to their high abundance in the cell, proteins are major targets for such oxidative stress and become irreversibly modified through amino acid carbonylation, disulfide bond cross-linking and peptide backbone cleavage [84]. Of note, oxidative stress is not restricted to immune cells but occurs per se in all tissues at a basal level, mostly because of the side reactions of the mitochondrion electron transport that occur with molecular oxygen, thereby generating ROS such as superoxide anions (O2 −), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and hydroxyl radicals (HO) [85]. The removal of oxidized proteins by proteasomes is clearly established [86–91], and recent work suggests that IP are more prone than SP at eliminating them [92]. An important observation is also made in the brain and the liver of β1i/LMP2−/− mice exhibiting higher levels of protein carbonyls upon aging than those of their wild-type littermates of the same genetic background [93]. An additional insight in this field has emerged from our recent study showing that protein carbonyls accumulating following IFN-γ treatment are simultaneously subjected to poly-ubiquitylation [74]. Interestingly, this notion is somehow in conflict with other reports arguing that the proteasome-mediated degradation of oxidized proteins may occur independently of that of poly-ubiquitylated substrates [92, 94, 95]. The basis for these discrepancies may be explained by the co-existence of distinct pools of oxidized proteins. However, the mechanisms whereby such substrates are sorted into either the 20S- or the 26S-dependent degradation pathway remain ill-defined. Most likely, the particularly short half-life of IFN-γ-induced oxidized proteins does not constitute a critical criterion for their targeting to the 26S complex, as short-lived oxidant-damaged proteins have also been shown to be efficiently degraded by 20S complexes [96–98]. Rather, the fate of oxidized proteins may be determined by the nature and/or strength of the stimulus itself. It is, indeed, conceivable that IFN-γ favors the breakdown of protein carbonyls by 26S proteasomes because of the concomitant increased activation of the ubiquitin-conjugation system in response to this cytokine. In any case, the precise contribution of each pathway to the disposal of these substrates warrants further investigations. Finally, a protective role of β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7 and β2i/MECL-1 against cellular oxidative damage is also reinforced by the observation that these subunits are constitutively expressed in cells which are frequently challenged with reactive oxygen radicals such as phagocytic cells (i.e., DC and macrophages) during the respiratory burst process.

A role for IP in cell growth and differentiation

Although it is clearly established that ubiquitin- and proteasome-dependent proteolysis is one of the key mechanisms underlying cell cycle control, the influence of the incorporation of β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7, and/or β2i/MECL-1 in this process remained relatively understudied over the past 10 years. It is only recently that gene knockout studies in mice have revealed a complex and unexpected role of the inducible subunits β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7, and β2i/MECL-1 in regulating cell proliferation and differentiation. This is particularly obvious in cells and tissues that constitutively express IP including hematopoietic cells such as T cells. A prime example of the involvement of IP in cell proliferation originally comes from the observation that both β1i/LMP2- and β2i/MECL-1-deficient mice exhibit significant decreased numbers of naive CD8+ T cells, when compared to their wild-type counterparts [29, 99]. The assumption that the inducible subunits intrinsically regulate T-cell expansion is further supported by the detection of enhanced CD4/CD8 T-cell ratios in β2i/MECL-1−/− mice [100]. Subsequent studies have also shown that T cells from β1i/LMP2−/−, β5i/LMP7−/− or β2i/MECL-1−/− mice fail to proliferate and survive when transferred into virus-infected wild-type mice [99, 101, 102], thereby suggesting that IP expression may be required for expansion and maintenance of T cells. In line with the notion that IP favor cell proliferation is the fact that β5i/LMP7, β1i/LMP2 and to a lesser extent β2i/MECL-1 are often over-expressed in various tumors of both hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic origin [48]. These findings even provided a rationale for targeting the inducible subunits β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7, or β2i/MECL-1 as a potential therapeutic strategy for several types of IP-positive tumors. Indeed, the use of the β1i/LMP2 specific inhibitor (IPSI-001) showed some success in diminishing cell proliferation in myeloma patient samples in vitro [103]. Interestingly, similar observations were made in vivo when inhibiting the β5i/LMP7 subunit with the PR-924 inhibitor [104], confirming the close correlation between mammalian IP expression and carcinogenesis. Nevertheless, the view that IP expression unconditionally supports cell proliferation is hampered by an earlier report showing that T cells from double knockout mice lacking both β2i/MECL-1 and β5i/LMP7 hyperproliferate in vitro in response to polyclonal mitogens [105]. These findings are not necessarily conflicting, since depending on their target substrates, proteasomes may realize negative as well as positive control of cell cycle [106]. The eukaryotic cell cycle is precisely orchestrated and regulated by multiple cyclin and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK) which form cyclin/CDK complexes that are negatively regulated by a number of CDK inhibitors including p27Kip1 and p21Cip1/WAF1 [107]. Proteasomes are involved in this process by regulating the protein turnover of the CDK inhibitors whose degradation favors the prolongation of cell cycle progression [108]. Given that IP destroy poly-ubiquitylated substrates and protein carbonyls faster than SP, it is highly likely that CDK inhibitors exhibit a particularly high protein turnover in cells and tissues constitutively expressing the inducible subunits, thereby resulting in increased susceptibility to cell proliferation. This notion is in agreement with the observation that defects or down-regulation of p21 have been linked to the development of various cancers and contribution to tumor progression [109]. Another major characteristic of malignant transformation of epithelial cells is the inactivation or down-regulation of p53, which is associated with the loss of cell cycle control and apoptosis evasion. To date, the role of IP in the breakdown of p53 remains unknown, but since p53 undergoes poly-ubiquitylation and/or is susceptible to oxidation, it is conceivable that it is degraded more quickly in tumor cells over-expressing β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7, and β2i/MECL-1, thereby participating in cell growth. The decreased capacity of cells expressing IP to undergo cell cycle arrest is also supported by a recent report showing that β5i/LMP7 gene silencing facilitates atherosclerotic lesion-derived cells to enter apoptosis in response to IFN-γ [110]. A high protein turnover in proliferating precursor cells also seems to be a major characteristic of the cell differentiation process. Indeed, it has been shown that rapid protein turnover of ERK3 by 26S proteasomes is required to achieve successful differentiation of PC12 and C2C12 cells into the neuronal and muscle lineage, respectively [111]. Such a finding suggests that IP may facilitate this process, a concept that would be in line with the fact that the high expression levels of β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7, and β2i/MECL-1 are maintained in fully differentiated cells such as DC and macrophages.

A role for IP in cell signaling and the regulation of cytokine production

A couple of studies hint at an unexpected role for the inducible subunits β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7 and β2i/MECL-1 in the regulation of the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Visekruna and colleagues have shown that the prominent expression of IP found in intestinal tissue from patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis was associated with enhanced activation of the NF-κB cell signaling pathway [53]. The transcription factor NF-κB is a well-known master regulator of many inflammatory cytokine genes and its activation by proteasomes is clearly established. Indeed, NF-κB is actively inhibited and sequestered in the cytoplasm when bound to proteins of the IκB family IκBα, β and γ. NF-κB activation involves phosphorylation of IκB which promotes its K48-linked poly-ubiquitylation and degradation by the 26S proteasome, thereby unmasking a nuclear targeting sequence of the NF-κB protein [112]. The role of the inducible subunits in this process has long remained unclear but the findings of the above-mentioned study leads to the hypothesis that IP may degrade IκB proteins faster than SP resulting in enhanced nuclear translocation of NF-κB. In our recent study, we could confirm that the protein turnover of IκB was much higher in cells over-expressing the three inducible subunits β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7, and β2i/MECL-1 than cells expressing predominantly SP [74]. Moreover, this notion is further strengthened by the observation that bone marrow-derived DC from β1i/LMP2-deficient mice exhibit substantial reduced levels of IFN-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α upon infection with influenza A virus [113]. Likewise, an impaired activation of NF-κB has been observed in β5i/LMP7−/− mice over the course of CVB3 infection [80]. Such results are of high interest, as they confirm our previous observations implying that the increased capacity of IP to breakdown K48-linked poly-ubiquitylated proteins is not restricted to IFN-γ-induced DRiPs and ALIS but can be extended to other proteasomal substrates. In addition, it was shown that the specific disruption of the β5i/LMP7 subunit by the PR-957 inhibitor results in a block of the secretion of IL-23, TNF-α, and IL-6 from stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), which is further accompanied by attenuation of the pathological symptoms and disease progression in a mouse model of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [114]. Surprisingly, and in spite of the fact that NF-κB regulates multiple critical cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of RA [115, 116], the authors failed to detect any impairment of the NF-κB signaling pathway in mice treated with PR-957. A role for β5i/LMP7 in the regulation of cytokine gene expression in a NF-κB-independent manner is also supported by a later study in which β5i/LMP7 disruption correlates with impaired production of IL-23 and IL-1β in a DSS-induced colitis model [81]. These results, however, are in contrast to other reports where the impaired production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in β5i/LMP7−/− mice was clearly associated with a substantial defect in the activation of NF-κB [80, 82]. Possible explanations why these studies have conflicting findings might be the tissue-specific contribution to different IP-functions or the simultaneous activation of multiple signaling pathways by β5i/LMP7. In line with the latter concept, it has recently been shown that each of the inducible subunits is capable of influencing regulatory signaling molecules other than NF-κB including TRIF and TRAM [117]. Both proteins are adaptor molecules, which play an essential role in the MyD88-independent signaling of TLR-4 and, as such, are critical regulators of the LPS response. In this study, macrophages from β1i/LMP2−/−, β5i/LMP7−/−, β2i/MECL-1−/− and LMP7−/−(β5i)/MECL-1−/−(β2i) knockout mice were far less able to produce NO in response to LPS, when compared to macrophages from wild-type mice. Therefore, the authors argued that the decreased activation of this pathway in IP-deficient mice is the result of a decreased degradation rate of both TRIF and TRAM, although this assumption remains to be proven. Interestingly, recent data also suggest a potential implication of IP in the regulation of the IFN signaling pathway, as determined by the elevated transcription of the IP-10, MCP-1, and RANTES genes detected in patients with CANDLE syndrome, a disease that has recently been associated with a nonsense mutation in the PSMB8 gene [118]. In addition, it seems that IP are also capable of influencing the p38 signaling pathway, as shown by increased phosphorylation of p38 and subsequent induction of IL-6 in response to PMA/ionomycin in cells over-expressing a non-functional β5i/LMP7 mutant [78, 79]. Again, the mechanisms whereby β5i/LMP7 regulates IL-6 production via p38 are far from being elucidated. It is proposed that, in contrast to the NF-κB pathway, the alteration of the p38 pathway is an indirect rather than a direct effect of β5i/LMP7 deficiency. Because p38 is influenced by the intracellular redox homeostasis [119], the investigators of this study suggest that the promotion of IL-6 via p38 occurs as a consequence of the inability of β5i/LMP7-deficient 20S and/or 26S proteasomes to cope with oxidized proteins. Taken together, these studies emphasize the role of the inducible subunits in the optimal activation of various signal transduction pathways by increasing the protein turnover of critical signaling factors. In this regard, and since IκBα is faster degraded by IP than by SP, it is tempting to speculate that the constitutive presence of IP in DC or macrophages allow these cells to quickly react to external stimuli by engaging rapidly the NF-κB transduction pathway. This, in turn, leads to the rapid secretion of NF-κB-dependent cytokines in response to pathogens. Another role of the inducible subunits in the acceleration of signal transduction may include T-cell activation which requires signaling through the T-cell receptor (TCR) and CD28 co-stimulatory receptor. Indeed, CD28 co-stimulation results in the poly-ubiquitylation and subsequent degradation of Cbl-β, which eliminates the negative regulators and allows the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and their receptors [120]. It is likely that such signaling is facilitated by the constitutive presence of IP in T cells, which quickly eliminate Cbl-β, thereby favoring rapid T-cell activation.

Summary and conclusion

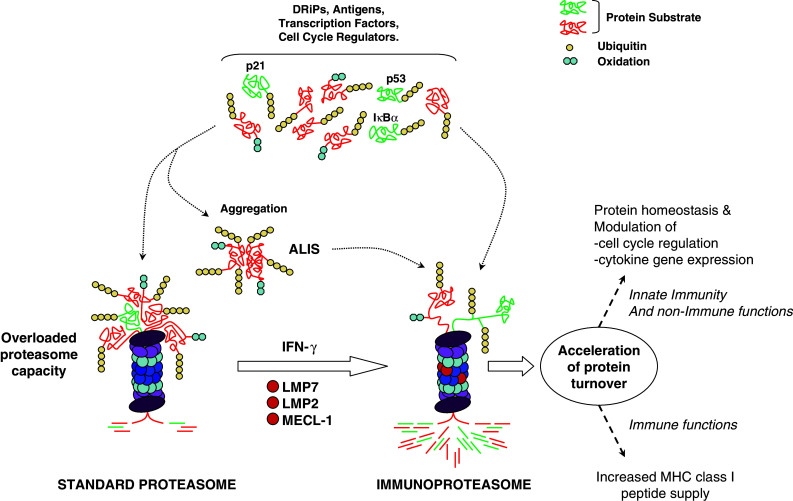

Collectively, the findings summarized in this review highlight a critical role for each of the inducible subunits β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7, and β2i/MECL-1 far beyond simple MHC class I antigen processing, as originally assumed. Indeed, IP are involved in all functions already fulfilled by SP including the regulation of protein homeostasis, cell proliferation, cell differentiation, cell signaling, gene transcription, and MHC class I antigen processing. The important observation that IP are more efficient than SP at degrading poly-ubiquitylated proteins has considerably expanded our understanding of how the incorporation of the inducible subunits into proteasome-complexes can modulate these functions. As illustrated in Fig. 1, by accelerating the degradation rate of all poly-ubiquitylated substrates, IP do not only promote the supply of MHC class I peptides but also induce remarkable changes in various other cellular functions by affecting the protein turnover of critical regulators such as IκBα. Depending on the influence of the degradation of such substrates, IP may represent positive or negative regulators. As such, the β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7, and β2i/MECL-1 subunits become attractive targets for therapeutic purposes against the development of pathologies including cancer, viral diseases, and neurodegenerative diseases. A particular high degree of complexity in the regulation of the half-life of poly-ubiquitylated proteins is brought by the existence of IP intermediate types containing one or two of the three inducible subunits. Therefore, further studies will need to be conducted in order to elucidate the precise role of each inducible subunit in these processes.

Fig. 1.

Immune and non-immune functions of the incorporated β1i/LMP2, β5i/LMP7, and β2i/MECL-1 inducible subunits. The proteasomal degradation of misfolded proteins (DRiPs) as well as regulator factors involved in cell cycle and cell signaling is a permanent ongoing process. The SP is less efficient than the IP at eliminating poly-ubiquitylated substrates and its capacity can be overloaded, thereby resulting in the accumulation of harmful protein aggregates (ALIS). The constitutive presence of IP (or its formation in response to IFN-γ) is accompanied by an acceleration of the degradation rate of all poly-ubiquitylated proteins which restores (or preserves) protein homeostasis. The increased protein turnover is not limited to DRiPs but also deals with other poly-ubiquitylated proteins including IκBα, p53 and/or p21 cip1/WAF1 whose increased degradation rate has impacts on cell cycle regulation and cytokine gene expression

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft: SFB/TR 84 to P.M.K., U.S., Kr 1914/4-1 to E.K., U.S., SFB 740 to E.K., P.M.K., KL421/15 to P.M.K., E.K., SFB TRR19 to P.M.K., SFB TRR 43 to E.K., P.M.K.

Abbreviations

- ALIS

Aggresome-like induced structures

- BM

Bone marrow

- CVB3

Coxsackievirus B3

- DALIS

Dendritic aggresome-like induced structures

- DC

Dendritic cells

- DSS

Dextran sulfate sodium

- EAE

Experimental autoimmune encephalitis

- EBV

Epstein–Barr virus

- IP

Immunoproteasome

- JASL

Japanese auto-inflammatory syndrome with lipodystrophy

- LCMV

Lymphochoriomeningitis virus

- LMP

Low-molecular-weight polypeptide

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- MEF

Mouse embryo fibroblasts

- NO

Nitric oxide

- NNS

Nakajo-Nishimura syndrome

- PA28

Proteasome activator 28

- PAMP

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- POMP

Proteasome maturation protein

- RA

Rheumatoid arthritis

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SP

Standard proteasome

- TAP

Transporter associated with antigen processing

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

Contributor Information

Elke Krüger, Email: elke.krueger@charite.de.

Ulrike Seifert, Phone: +49-30-450528186, FAX: +49-30-450528921, Email: ulrike.seifert@charite.de.

References

- 1.Coux O, Tanaka K, Goldberg AL. Structure and functions of the 20S and 26S proteasomes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:801–847. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumeister W, Walz J, Zuhl F, Seemüller E. The proteasome: paradigm of a self-compartmentalizing protease. Cell. 1998;92(3):367–380. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80929-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groll M, Bochtler M, Brandstetter H, Clausen T, Huber R. Molecular machines for protein degradation. Chembiochem. 2005;6(2):222–256. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pickart CM. Mechanisms underlying ubiquitination. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:503–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weissman AM. Themes and variations on ubiquitylation. Natl Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(3):169–178. doi: 10.1038/35056563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glickman MH, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway: destruction for the sake of construction. Physiol Rev. 2002;82(2):373–428. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kloetzel PM. The proteasome and MHC class I antigen processing. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1695(1–3):225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niedermann G, Butz S, Ihlenfeldt HG, Grimm R, Lucchiari M, Hoschutzky H, Jung G, Maier B, Eichmann K. Contribution of proteasome-mediated proteolysis to the hierarchy of epitopes presented by major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Immunity. 1995;2(3):289–299. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rock KL, Gramm C, Rothstein L, Clark K, Stein R, Dick L, Hwang D, Goldberg AL. Inhibitors of the proteasome block the degradation of most cell proteins and the generation of peptides presented on MHC class I molecules. Cell. 1994;78(5):761–771. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(94)90462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monaco JJ. A molecular model of MHC class-I-restricted antigen processing. Immunol Today. 1992;13(5):173–179. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90122-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown MG, Driscoll J, Monaco JJ. Structural and serological similarity of MHC-linked LMP and proteasome (multicatalytic proteinase) complexes. Nature. 1991;353(6342):355–357. doi: 10.1038/353355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monaco JJ, McDevitt HO. Identification of a fourth class of proteins linked to the murine major histocompatibility complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79(9):3001–3005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.9.3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez CK, Monaco JJ. Homology of proteasome subunits to a major histocompatibility complex-linked LMP gene. Nature. 1991;353(6345):664–667. doi: 10.1038/353664a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ortiz-Navarrete V, Seelig A, Gernold M, Frentzel S, Kloetzel PM, Hämmerling GJ. Subunit of the ‘20S’ proteasome (multicatalytic proteinase) encoded by the major histocompatibility complex. Nature. 1991;353(6345):662–664. doi: 10.1038/353662a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Y, Waters JB, Früh K, Peterson PA. Proteasomes are regulated by interferon gamma: implications for antigen processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(11):4928–4932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.4928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monaco JJ, McDevitt HO. H-2-linked low-molecular weight polypeptide antigens assemble into an unusual macromolecular complex. Nature. 1984;309(5971):797–799. doi: 10.1038/309797a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monaco JJ, McDevitt HO. The LMP antigens: a stable MHC-controlled multisubunit protein complex. Hum Immunol. 1986;15(4):416–426. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(86)90019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho S, Attaya M, Brown MG, Monaco JJ. A cluster of transcribed sequences between the Pb and Ob genes of the murine major histocompatibility complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(12):5197–5201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akiyama K, Yokota K, Kagawa S, Shimbara N, Tamura T, Akioka H, Nothwang HG, Noda C, Tanaka K, Ichihara A. cDNA cloning and interferon gamma down-regulation of proteasomal subunits X and Y. Science. 1994;265(5176):1231–1234. doi: 10.1126/science.8066462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Früh K, Gossen M, Wang K, Bujard H, Peterson PA, Yang Y. Displacement of housekeeping proteasome subunits by MHC-encoded LMPs: a newly discovered mechanism for modulating the multicatalytic proteinase complex. EMBO J. 1994;13(14):3236–3244. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belich MP, Glynne RJ, Senger G, Sheer D, Trowsdale J. Proteasome components with reciprocal expression to that of the MHC-encoded LMP proteins. Curr Biol. 1994;4(9):769–776. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heink S, Ludwig D, Kloetzel PM, Krüger E. IFN-gamma-induced immune adaptation of the proteasome system is an accelerated and transient response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(26):9241–9246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501711102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boes B, Hengel H, Ruppert T, Multhaup G, Koszinowski UH, Kloetzel PM. Interferon gamma stimulation modulates the proteolytic activity and cleavage site preference of 20S mouse proteasomes. J Exp Med. 1994;179(3):901–909. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanaka K. Role of proteasomes modified by interferon-gamma in antigen processing. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;56(5):571–575. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaczynska M, Rock KL, Goldberg AL. Gamma-interferon and expression of MHC genes regulate peptide hydrolysis by proteasomes. Nature. 1993;365(6443):264–267. doi: 10.1038/365264a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaczynska M, Rock KL, Spies T, Goldberg AL. Peptidase activities of proteasomes are differentially regulated by the major histocompatibility complex-encoded genes for LMP2 and LMP7. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(20):9213–9217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toes RE, Nussbaum AK, Degermann S, Schirle M, Emmerich NP, Kraft M, Laplace C, Zwinderman A, Dick TP, Müller J, Schönfisch B, Schmid C, Fehling HJ, Stevanovic S, Rammensee HG, Schild H. Discrete cleavage motifs of constitutive and immunoproteasomes revealed by quantitative analysis of cleavage products. J Exp Med. 2001;194(1):1–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fehling HJ, Swat W, Laplace C, Kühn R, Rajewsky K, Müller U, von Boehmer H. MHC class I expression in mice lacking the proteasome subunit LMP-7. Science. 1994;265(5176):1234–1237. doi: 10.1126/science.8066463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Kaer L, Ashton-Rickardt PG, Eichelberger M, Gaczynska M, Nagashima K, Rock KL, Goldberg AL, Doherty PC, Tonegawa S. Altered peptidase and viral-specific T cell response in LMP2 mutant mice. Immunity. 1994;1(7):533–541. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strehl B, Joeris T, Rieger M, Visekruna A, Textoris-Taube K, Kaufmann SH, Kloetzel PM, Kuckelkorn U, Steinhoff U. Immunoproteasomes are essential for clearance of Listeria monocytogenes in nonlymphoid tissues but not for induction of bacteria-specific CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177(9):6238–6244. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sibille C, Gould KG, Willard-Gallo K, Thomson S, Rivett AJ, Powis S, Butcher GW, De Baetselier P. LMP2+ proteasomes are required for the presentation of specific antigens to cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Curr Biol. 1995;5(8):923–930. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(95)00182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cerundolo V, Kelly A, Elliott T, Trowsdale J, Townsend A. Genes encoded in the major histocompatibility complex affecting the generation of peptides for TAP transport. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25(2):554–562. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Groettrup M, Kraft R, Kostka S, Standera S, Stohwasser R, Kloetzel PM. A third interferon-gamma-induced subunit exchange in the 20S proteasome. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26(4):863–869. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nandi D, Jiang H, Monaco JJ. Identification of MECL-1 (LMP-10) as the third IFN-gamma-inducible proteasome subunit. J Immunol. 1996;156(7):2361–2364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larsen F, Solheim J, Kristensen T, Kolsto AB, Prydz H. A tight cluster of five unrelated human genes on chromosome 16q22.1. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2(10):1589–1595. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.10.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sijts AJ, Standera S, Toes RE, Ruppert T, Beekman NJ, van Veelen PA, Ossendorp FA, Melief CJ, Kloetzel PM. MHC class I antigen processing of an adenovirus CTL epitope is linked to the levels of immunoproteasomes in infected cells. J Immunol. 2000;164(9):4500–4506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwarz K, van Den Broek M, Kostka S, Kraft R, Soza A, Schmidtke G, Kloetzel PM, Groettrup M. Overexpression of the proteasome subunits LMP2, LMP7, and MECL-1, but not PA28 alpha/beta, enhances the presentation of an immunodominant lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus T cell epitope. J Immunol. 2000;165(2):768–778. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noda C, Tanahashi N, Shimbara N, Hendil KB, Tanaka K. Tissue distribution of constitutive proteasomes, immunoproteasomes, and PA28 in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;277(2):348–354. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haorah J, Heilman D, Diekmann C, Osna N, Donohue TM, Jr, Ghorpade A, Persidsky Y. Alcohol and HIV decrease proteasome and immunoproteasome function in macrophages: implications for impaired immune function during disease. Cell Immunol. 2004;229(2):139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frisan T, Levitsky V, Masucci MG. Variations in proteasome subunit composition and enzymatic activity in B-lymphoma lines and normal B cells. Int J Cancer. 2000;88(6):881–888. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20001215)88:6<881::AID-IJC7>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frisan T, Levitsky V, Polack A, Masucci MG. Phenotype-dependent differences in proteasome subunit composition and cleavage specificity in B cell lines. J Immunol. 1998;160(7):3281–3289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Altun M, Galardy PJ, Shringarpure R, Hideshima T, LeBlanc R, Anderson KC, Ploegh HL, Kessler BM. Effects of PS-341 on the activity and composition of proteasomes in multiple myeloma cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65(17):7896–7901. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Macagno A, Gilliet M, Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A, Nestle FO, Groettrup M. Dendritic cells up-regulate immunoproteasomes and the proteasome regulator PA28 during maturation. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29(12):4037–4042. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199912)29:12<4037::AID-IMMU4037>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Link C, Gavioli R, Ebensen T, Canella A, Reinhard E, Guzman CA. The Toll-like receptor ligand MALP-2 stimulates dendritic cell maturation and modulates proteasome composition and activity. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34(3):899–907. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Macagno A, Kuehn L, de Giuli R, Groettrup M. Pronounced up-regulation of the PA28alpha/beta proteasome regulator but little increase in the steady-state content of immunoproteasome during dendritic cell maturation. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31(11):3271–3280. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200111)31:11<3271::AID-IMMU3271>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ossendorp F, Fu N, Camps M, Granucci F, Gobin SJ, van den Elsen PJ, Schuurhuis D, Adema GJ, Lipford GB, Chiba T, Sijts A, Kloetzel PM, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Melief CJ. Differential expression regulation of the alpha and beta subunits of the PA28 proteasome activator in mature dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2005;174(12):7815–7822. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li J, Schuler-Thurner B, Schuler G, Huber C, Seliger B. Bipartite regulation of different components of the MHC class I antigen-processing machinery during dendritic cell maturation. Int Immunol. 2001;13(12):1515–1523. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.12.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guillaume B, Chapiro J, Stroobant V, Colau D, Van Holle B, Parvizi G, Bousquet-Dubouch MP, Theate I, Parmentier N, Van den Eynde BJ. Two abundant proteasome subtypes that uniquely process some antigens presented by HLA class I molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(43):18599–18604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009778107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ebstein F, Lange N, Urban S, Seifert U, Krüger E, Kloetzel PM. Maturation of human dendritic cells is accompanied by functional remodelling of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41(5):1205–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barton LF, Cruz M, Rangwala R, Deepe GS, Jr, Monaco JJ. Regulation of immunoproteasome subunit expression in vivo following pathogenic fungal infection. J Immunol. 2002;169(6):3046–3052. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chatterjee-Kishore M, Wright KL, Ting JP, Stark GR. How Stat1 mediates constitutive gene expression: a complex of unphosphorylated Stat1 and IRF1 supports transcription of the LMP2 gene. EMBO J. 2000;19(15):4111–4122. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.15.4111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Visekruna A, Slavova N, Dullat S, Grone J, Kroesen AJ, Ritz JP, Buhr HJ, Steinhoff U. Expression of catalytic proteasome subunits in the gut of patients with Crohn’s disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24(10):1133–1139. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0679-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Visekruna A, Joeris T, Seidel D, Kroesen A, Loddenkemper C, Zeitz M, Kaufmann SH, Schmidt-Ullrich R, Steinhoff U. Proteasome-mediated degradation of IkappaBalpha and processing of p105 in Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(12):3195–3203. doi: 10.1172/JCI28804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen M, Tabaczewski P, Truscott SM, Van Kaer L, Stroynowski I. Hepatocytes express abundant surface class I MHC and efficiently use transporter associated with antigen processing, tapasin, and low molecular weight polypeptide proteasome subunit components of antigen processing and presentation pathway. J Immunol. 2005;175(2):1047–1055. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vasuri F, Capizzi E, Bellavista E, Mishto M, Santoro A, Fiorentino M, Capri M, Cescon M, Grazi GL, Grigioni WF, D’Errico-Grigioni A, Franceschi C. Studies on immunoproteasome in human liver. Part I: absence in fetuses, presence in normal subjects, and increased levels in chronic active hepatitis and cirrhosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;397(2):301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.05.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Loukissa A, Cardozo C, Altschuller-Felberg C, Nelson JE. Control of LMP7 expression in human endothelial cells by cytokines regulating cellular and humoral immunity. Cytokine. 2000;12(9):1326–1330. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roby KF, Yang Y, Gershon D, Hunt JS. Cellular distribution of proteasome subunit Lmp7 mRNA and protein in human placentas. Immunology. 1995;86(3):469–474. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baldovino S, Piccinini M, Anselmino A, Ramondetti C, Rinaudo MT, Costanzo P, Sena LM, Roccatello D. Structural and functional properties of proteasomes purified from the human kidney. J Nephrol. 2006;19(6):710–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singh S, Awasthi N, Egwuagu CE, Wagner BJ. Immunoproteasome expression in a nonimmune tissue, the ocular lens. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;405(2):147–153. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hussong SA, Kapphahn RJ, Phillips SL, Maldonado M, Ferrington DA. Immunoproteasome deficiency alters retinal proteasome’s response to stress. J Neurochem. 2010;113(6):1481–1490. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06688.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ferrington DA, Hussong SA, Roehrich H, Kapphahn RJ, Kavanaugh SM, Heuss ND, Gregerson DS. Immunoproteasome responds to injury in the retina and brain. J Neurochem. 2008;106(1):158–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05345.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Piccinini M, Mostert M, Croce S, Baldovino S, Papotti M, Rinaudo MT. Interferon-gamma-inducible subunits are incorporated in human brain 20S proteasome. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;135(1–2):135–140. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5728(02)00439-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mishto M, Bellavista E, Santoro A, Stolzing A, Ligorio C, Nacmias B, Spazzafumo L, Chiappelli M, Licastro F, Sorbi S, Pession A, Ohm T, Grune T, Franceschi C. Immunoproteasome and LMP2 polymorphism in aged and Alzheimer’s disease brains. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27(1):54–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nijholt DA, de Graaf TR, van Haastert ES, Oliveira AO, Berkers CR, Zwart R, Ovaa H, Baas F, Hoozemans JJ, Scheper W. Endoplasmic reticulum stress activates autophagy but not the proteasome in neuronal cells: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18(6):1071–1081. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Diaz-Hernandez M, Hernandez F, Martin-Aparicio E, Gomez-Ramos P, Moran MA, Castano JG, Ferrer I, Avila J, Lucas JJ. Neuronal induction of the immunoproteasome in Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci. 2003;23(37):11653–11661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-37-11653.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Diaz-Hernandez M, Martin-Aparicio E, Avila J, Hernandez F, Lucas JJ. Enhanced induction of the immunoproteasome by interferon gamma in neurons expressing mutant Huntingtin. Neurotoxic Res. 2004;6(6):463–468. doi: 10.1007/BF03033282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gavilan MP, Castano A, Torres M, Portavella M, Caballero C, Jimenez S, Garcia-Martinez A, Parrado J, Vitorica J, Ruano D. Age-related increase in the immunoproteasome content in rat hippocampus: molecular and functional aspects. J Neurochem. 2009;108(1):260–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mishto M, Santoro A, Bellavista E, Bonafe M, Monti D, Franceschi C. Immunoproteasomes and immunosenescence. Ageing Res Rev. 2003;2(4):419–432. doi: 10.1016/S1568-1637(03)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kremer M, Henn A, Kolb C, Basler M, Moebius J, Guillaume B, Leist M, Van den Eynde BJ, Groettrup M. Reduced immunoproteasome formation and accumulation of immunoproteasomal precursors in the brains of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-infected mice. J Immunol. 2010;185(9):5549–5560. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Godbout JP, Johnson RW. Age and neuroinflammation: a lifetime of psychoneuroimmune consequences. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2009;29(2):321–337. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lelouard H, Gatti E, Cappello F, Gresser O, Camosseto V, Pierre P. Transient aggregation of ubiquitinated proteins during dendritic cell maturation. Nature. 2002;417(6885):177–182. doi: 10.1038/417177a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Canadien V, Tan T, Zilber R, Szeto J, Perrin AJ, Brumell JH. Cutting edge: microbial products elicit formation of dendritic cell aggresome-like induced structures in macrophages. J Immunol. 2005;174(5):2471–2475. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Szeto J, Kaniuk NA, Canadien V, Nisman R, Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Bazett-Jones DP, Brumell JH. ALIS are stress-induced protein storage compartments for substrates of the proteasome and autophagy. Autophagy. 2006;2(3):189–199. doi: 10.4161/auto.2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Seifert U, Bialy LP, Ebstein F, Bech-Otschir D, Voigt A, Schröter F, Prozorovski T, Lange N, Steffen J, Rieger M, Kuckelkorn U, Aktas O, Kloetzel PM, Krüger E. Immunoproteasomes preserve protein homeostasis upon interferon-induced oxidative stress. Cell. 2010;142(4):613–624. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sijts AJ, Ruppert T, Rehermann B, Schmidt M, Koszinowski U, Kloetzel PM. Efficient generation of a hepatitis B virus cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope requires the structural features of immunoproteasomes. J Exp Med. 2000;191(3):503–514. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ferrer I, Martin B, Castano JG, Lucas JJ, Moreno D, Olive M. Proteasomal expression, induction of immunoproteasome subunits, and local MHC class I presentation in myofibrillar myopathy and inclusion body myositis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63(5):484–498. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.5.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.French BA, Oliva J, Bardag-Gorce F, French SW. The immunoproteasome in steatohepatitis: its role in Mallory-Denk body formation. Exp Mol Pathol. 2011;90(3):252–256. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Arima K, Kinoshita A, Mishima H, Kanazawa N, Kaneko T, Mizushima T, Ichinose K, Nakamura H, Tsujino A, Kawakami A, Matsunaka M, Kasagi S, Kawano S, Kumagai S, Ohmura K, Mimori T, Hirano M, Ueno S, Tanaka K, Tanaka M, Toyoshima I, Sugino H, Yamakawa A, Tanaka K, Niikawa N, Furukawa F, Murata S, Eguchi K, Ida H, Yoshiura K. Proteasome assembly defect due to a proteasome subunit beta type 8 (PSMB8) mutation causes the autoinflammatory disorder, Nakajo-Nishimura syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(36):14914–14919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106015108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kitamura A, Maekawa Y, Uehara H, Izumi K, Kawachi I, Nishizawa M, Toyoshima Y, Takahashi H, Standley DM, Tanaka K, Hamazaki J, Murata S, Obara K, Toyoshima I, Yasutomo K. A mutation in the immunoproteasome subunit PSMB8 causes autoinflammation and lipodystrophy in humans. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(10):4150–4160. doi: 10.1172/JCI58414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Opitz E, Koch A, Klingel K, Schmidt F, Prokop S, Rahnefeld A, Sauter M, Heppner FL, Volker U, Kandolf R, Kuckelkorn U, Stangl K, Krüger E, Kloetzel PM, Voigt A. Impairment of immunoproteasome function by beta5i/LMP7 subunit deficiency results in severe enterovirus myocarditis. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(9):e1002233. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Basler M, Dajee M, Moll C, Groettrup M, Kirk CJ. Prevention of experimental colitis by a selective inhibitor of the immunoproteasome. J Immunol. 2010;185(1):634–641. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schmidt N, Gonzalez E, Visekruna A, Kühl AA, Loddenkemper C, Mollenkopf H, Kaufmann SH, Steinhoff U, Joeris T. Targeting the proteasome: partial inhibition of the proteasome by bortezomib or deletion of the immunosubunit LMP7 attenuates experimental colitis. Gut. 2010;59(7):896–906. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.203554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Frohner IE, Bourgeois C, Yatsyk K, Majer O, Kuchler K. Candida albicans cell surface superoxide dismutases degrade host-derived reactive oxygen species to escape innate immune surveillance. Mol Microbiol. 2009;71(1):240–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Levine RL. Carbonyl modified proteins in cellular regulation, aging, and disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32(9):790–796. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00765-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Teoh CY, Davies KJ. Potential roles of protein oxidation and the immunoproteasome in MHC class I antigen presentation: the ‘PrOxI’ hypothesis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;423(1):88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Grune T, Reinheckel T, Joshi M, Davies KJ. Proteolysis in cultured liver epithelial cells during oxidative stress. Role of the multicatalytic proteinase complex, proteasome. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(5):2344–2351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Grune T, Reinheckel T, Davies KJ. Degradation of oxidized proteins in K562 human hematopoietic cells by proteasome. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(26):15504–15509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Grune T, Reinheckel T, Davies KJ. Degradation of oxidized proteins in mammalian cells. Faseb J. 1997;11(7):526–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ullrich O, Reinheckel T, Sitte N, Hass R, Grune T, Davies KJ. Poly-ADP ribose polymerase activates nuclear proteasome to degrade oxidatively damaged histones. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(11):6223–6228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ullrich O, Sitte N, Sommerburg O, Sandig V, Davies KJ, Grune T. Influence of DNA binding on the degradation of oxidized histones by the 20S proteasome. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;362(2):211–216. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Davies KJ. Degradation of oxidized proteins by the 20S proteasome. Biochimie. 2001;83(3–4):301–310. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9084(01)01250-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pickering AM, Koop AL, Teoh CY, Ermak G, Grune T, Davies KJ. The immunoproteasome, the 20S proteasome and the PA28alphabeta proteasome regulator are oxidative-stress-adaptive proteolytic complexes. Biochem J. 2010;432(3):585–594. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ding Q, Martin S, Dimayuga E, Bruce-Keller AJ, Keller JN. LMP2 knock-out mice have reduced proteasome activities and increased levels of oxidatively damaged proteins. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8(1–2):130–135. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shringarpure R, Grune T, Mehlhase J, Davies KJ. Ubiquitin conjugation is not required for the degradation of oxidized proteins by proteasome. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(1):311–318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206279200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Inai Y, Nishikimi M. Increased degradation of oxidized proteins in yeast defective in 26 S proteasome assembly. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;404(2):279–284. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00336-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sahakian JA, Szweda LI, Friguet B, Kitani K, Levine RL. Aging of the liver: proteolysis of oxidatively modified glutamine synthetase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;318(2):411–417. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Grune T, Blasig IE, Sitte N, Roloff B, Haseloff R, Davies KJ. Peroxynitrite increases the degradation of aconitase and other cellular proteins by proteasome. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(18):10857–10862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.10857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ferrington DA, Sun H, Murray KK, Costa J, Williams TD, Bigelow DJ, Squier TC. Selective degradation of oxidized calmodulin by the 20 S proteasome. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(2):937–943. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005356200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Basler M, Moebius J, Elenich L, Groettrup M, Monaco JJ. An altered T cell repertoire in MECL-1-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2006;176(11):6665–6672. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zaiss DM, de Graaf N, Sijts AJ. The proteasome immunosubunit multicatalytic endopeptidase complex-like 1 is a T-cell-intrinsic factor influencing homeostatic expansion. Infect Immun. 2008;76(3):1207–1213. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01134-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chen W, Norbury CC, Cho Y, Yewdell JW, Bennink JR. Immunoproteasomes shape immunodominance hierarchies of antiviral CD8(+) T cells at the levels of T cell repertoire and presentation of viral antigens. J Exp Med. 2001;193(11):1319–1326. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.11.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Moebius J, van den Broek M, Groettrup M, Basler M. Immunoproteasomes are essential for survival and expansion of T cells in virus-infected mice. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40(12):3439–3449. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kuhn DJ, Hunsucker SA, Chen Q, Voorhees PM, Orlowski M, Orlowski RZ. Targeted inhibition of the immunoproteasome is a potent strategy against models of multiple myeloma that overcomes resistance to conventional drugs and nonspecific proteasome inhibitors. Blood. 2009;113(19):4667–4676. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-171637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]