Abstract

An increase in the concentration of cytosolic free Ca2+ is a key component regulating different cellular processes ranging from egg fertilization, active secretion and movement, to cell differentiation and death. The multitude of phenomena modulated by Ca2+, however, do not simply rely on increases/decreases in its concentration, but also on specific timing, shape and sub-cellular localization of its signals that, combined together, provide a huge versatility in Ca2+ signaling. Intracellular organelles and their Ca2+ handling machineries exert key roles in this complex and precise mechanism, and this review will try to depict a map of Ca2+ routes inside cells, highlighting the uniqueness of the different Ca2+ toolkit components and the complexity of the interactions between them.

Keywords: Ca2+ stores, Mitochondria, Ca2+ releasing channels, Ca2+ pumps, Sub-cellular signaling, Ca2+ microdomains

Introduction

In both excitable and non-excitable cells, rises in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) depend on Ca2+ release from intracellular stores and/or Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane (PM), though the relative importance of these pathways can vary depending on the cell type and the stimulus. As to the first mechanism, tens of different isoforms of Ca2+-permeable channels are expressed on the PM of all cells. The specific repertoire of Ca2+ channels of the PM depends on the cell type, the developmental stage and the subcellular domain of the PM [1]. As far as Ca2+ release is concerned, in non-muscle cells it is most often triggered by the activation of phospholipase C (PLC, different isoforms), which produces inositol 1,4,5 trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol. IP3 interacts with Ca2+ channels located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus (GA), causing their opening and the release of Ca2+ into the cytosol. Ca2+ release from stores is most often accompanied by Ca2+ influx through PM channels (Capacitative Ca2+ Entry, CCE), whose nature and mechanism of opening were recently defined [2, 3]. The Ca2+ signal is terminated by the combined activities of the Ca2+ extrusion mechanisms (the PM Ca2+ ATPase, PMCA and the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, NCX) or the sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) and the secretory pathway Ca2+ ATPase (SPCA) of the GA, and other acidic compartments, that re-accumulate the cation in the organelles’ lumen [4]. Apart from the classical IP3 molecule, other intracellular messengers, such as cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR) and nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP), are now emerging as key players in the Ca2+ saga, though their role in different cell types is still under investigation (see [5] and [6] for recent reviews). The specific interactions among these different messengers, and the precise localization of the [Ca2+]i increases selectively activated by these second messengers, are the subject of intense study as it is clear that cellular Ca2+ dynamic is often non-homogeneous in terms of speed, amplitude and spatio-temporal patterns. On this aspect, the role of different intracellular organelles on cytosolic Ca2+ handling should be carefully taken into account: ER, GA, endosomes, lysosomes, peroxisomes, secretory granules and mitochondria, with their specific ability in accumulating Ca2+, can all contribute to the overall cytosolic Ca2+ response (Fig. 1).

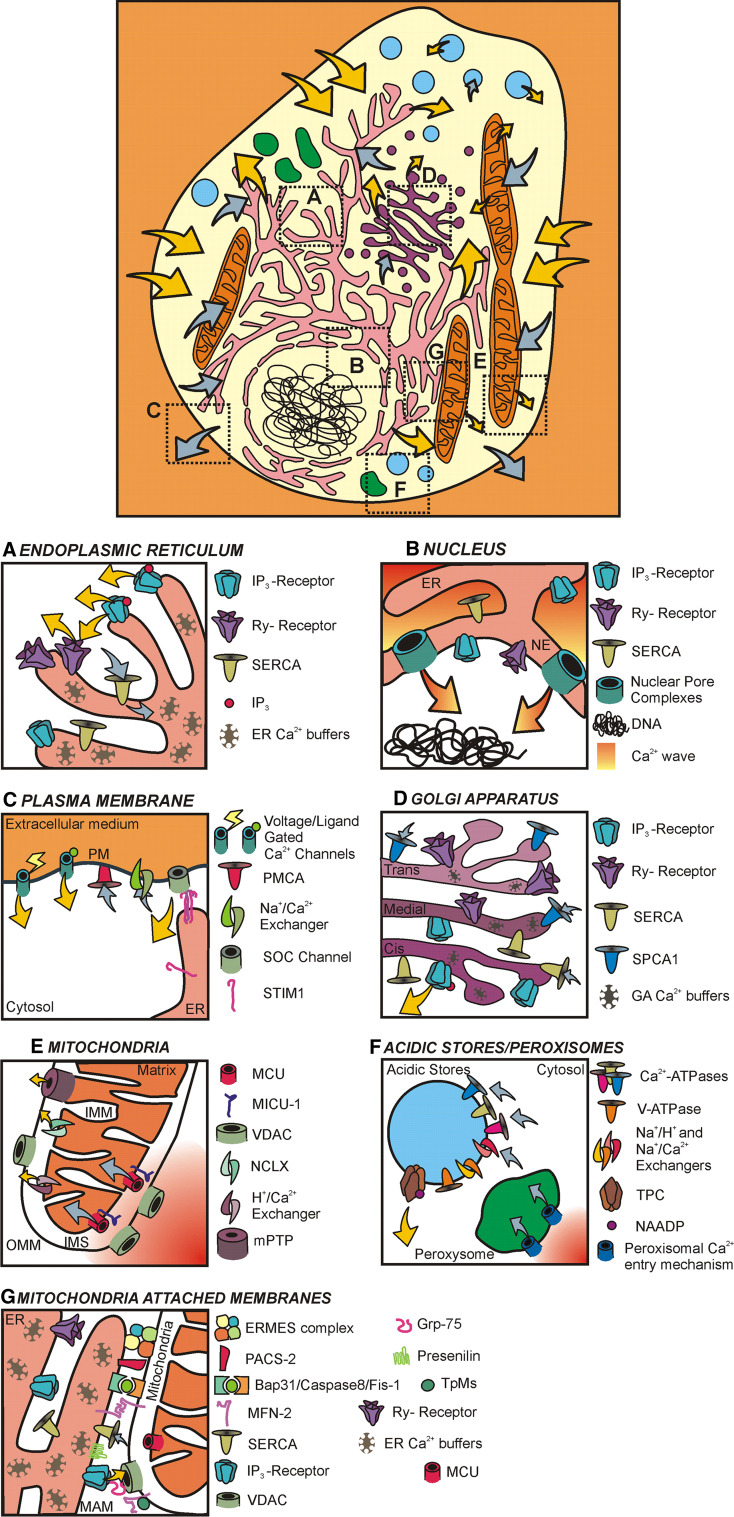

Fig. 1.

Ca2+ handling organelles and molecular toolkit. Schematic representation of a typical cell with its several organelles involved in Ca2+ homeostasis: endoplasmic reticulum (pink), mitochondria (orange), Golgi apparatus (purple), acidic stores (light blue) and peroxisomes (green). Possible contributions to cytosolic [Ca2+] changes are pictured by arrows: yellow/grey arrows indicate events leading to an increase/decrease in [Ca2+]cyt, respectively, and their relative dimensions mirror the estimated relevance of each contribution in global cell Ca2+ signal. Insets a–g illustrate, in better details, each sub-compartment’s Ca2+ handling characteristics. a Endoplasmic reticulum (ER): note Ca2+ buffers inside the organelle lumen, IP3 and ryanodine receptors (IP3- and Ry-receptors) releasing Ca2+ upon stimulation, and SERCAs refilling the store. b Nucleus: nuclear envelope (NE) is an ER sub-domain and is thus endowed with ER Ca2+ handling molecules (i.e., IP3Rs, RyRs and SERCAs); note the large nuclear pore complex (NPC), allowing the diffusion of cytosolic Ca2+ waves into the nucleoplasm; c plasma membrane (PM): this critical site for Ca2+ handling is here extremely simplified, underscoring the presence of extrusion mechanisms (e.g., PM Ca2+ ATPase, Na+/Ca2+ exchangers) and Ca2+ channels (e.g., voltage- and ligand- gated Ca2+ channels); store-operating Ca2+ entry (SOCE) mechanism is also depicted, showing the SOC channel generation induced by Orai-1 units’ oligomerization induced by the ER-resident Stim-1 clustering in “punctae.” d Golgi apparatus (GA): GA heterogeneity in terms of Ca2+ handling is represented by the differential distribution of IP3Rs, RyRs and Ca2+ ATPase (i.e., SERCA and SPCA-1) in its sub-compartments (cis-, medial-, trans-Golgi); e mitochondria: cytosolic Ca2+ easily permeates the outer mitochondria membrane (OMM) through large VDAC channels, and once in the inter-membrane space (IMS) is sensed by MICU-1 and captured by the recently identified MCU into mitochondrial matrix; Ca2+ extrusion mechanisms from this site comprise exchangers (NCLX, H+/Ca2+ exchanger) and mPTP. f As depicting the whole multitude of intracellular acidic stores is impossible, we here limit ourselves to stress the existence of several mechanisms allowing Ca2+ entry into acidic stores, including Ca2+ ATPases and exchangers; as major Ca2+ releasing mechanism, the recently identified TPC channels gated by NAADP are depicted; considering peroxisomes, their Ca2+-entry mechanism remains still elusive; thus we only underscore their capability of taking up Ca2+ from cytosol. g Mitochondria-attached membranes (MAMs): due to their key role in Ca2+ homeostasis, these domains of close interaction between ER and mitochondria need special consideration; in the cartoon several proteins involved in modulating ER-mitochondria interactions are emphasized, i.e., mitofusin-2, IP3R/grp75/VDAC complex, Bap31/Fis-1 complex (with Caspase-8), PACS-2, tichoplein/mitostatin (TpMs), presenilin-2 and ERMES complex. See text for details

In this review, we discuss how Ca2+ is compartmentalized both physically and functionally within the endomembrane system and describe how each organelle has its own distinct Ca2+-handling properties with particular emphasis on the final coordinated event that is to shape and tune cellular Ca2+ signal.

The endoplasmic reticulum

The ER is an organelle diffused throughout the whole cytoplasm of nucleated eukaryotic cells. Apart from being indispensable for the synthesis, folding, post-translational modifications and transport of proteins to their target locations (reviewed in [7] and [8]), the ER is also the largest and most controllable intracellular Ca2+ store within the cell.

Although originally the ER and its muscle-specialized version, the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), were considered as the same cytological entity, namely the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum (SR/ER, [9]), now they are instead viewed as morphologically and functionally distinct, with the latter considered an ER-derived reticular network progressively evolved into a unique, highly specialized morpho-functional structure of the striated muscle fibers. Indeed, in recent years, ER itself has emerged as a complex and dynamic structure, and several distinct and specialized sub-domains have been identified [10].

In this contribution, we will focus on the ER of non-muscle cells, while we will only briefly mention a few specific characteristics of the SR. On this latter issue, the interested reader is referred to recent reviews for more detailed information (see for example [11, 12]).

The ER is a complex organelle composed of membrane sheets that enclose the nucleus (the nuclear envelope, NE) and an elaborate interconnected tubular network in the cytosol. This highly dynamic and elaborate structure is the result of a constant remodeling process that involves the formation of new tubules, their transport along the cytoskeleton and homotypic fusion events [13, 14]. Morphologically, the ER is sub-divided into three major, distinct domains: the smooth ER, the rough ER and the nuclear membrane [15]. The major feature commonly used to distinguish rough and smooth ER is the presence (in the first one) of bound ribosomes, while the nuclear membrane has ribosomes bound only to the outer surface, it contains the nuclear pores and the inner surface has a unique protein composition and function. For this reason the nuclear compartment, in regard to Ca2+ handling, will be discussed separately (see below).

The ER plays a major role in cell Ca2+ homeostasis and signaling (Fig. 1a): it contains ATP-driven pumps, for Ca2+ uptake (the so-called SERCAs), Ca2+-binding proteins, for Ca2+ storage within the lumen, and channels for Ca2+ release (the ubiquitous IP3 receptors, IP3Rs, and, in many cells, also the ryanodine receptors, RyRs; see below). Some of these molecular components (and their different isoforms) are non-randomly distributed within ER membranes concurring to a sort of heterogeneity in Ca2+ storage [16], Ca2+ uptake [17] or Ca2+ release [18, 19] of different ER sub-compartments. In different in vitro systems it has been shown that distinct Ca2+ pools, sensitive to different agonists [20, 21] and with different levels of Ca2+ in their lumen [22, 23], can coexist within the ER, although these data were never confirmed in vivo. The concept that distinct sub-compartments exist within the ER is thus still debated, and, in particular, it is unclear how this separation in distinct sub-pools could be maintained. Indeed, more conclusive evidence for a structural and functional ER continuity has been reached by different methodologies: experiments of fluorescence photobleaching in cells expressing an ER-located GFP show that both membrane and lumen are continuous throughout the ER network [23–25]; similar results were also obtained by using a photoactivable GFP expressed in neurons and astrocytes of organotypic brain slices by lentiviral infection [26]; functionally, a continuity in the ER lumen was shown in different cell types with respect to Ca2+ handling and tunneling [27–30], as reviewed also in [31]. Based on these considerations, it is tempting to speculate that the ER is a continuous membrane network and, in steady state, its Ca2+ level is homogeneous, but the heterogeneous distribution of SERCAs and Ca2+ channels may however result in transient local changes of Ca2+ concentration within the organelle.

Overall, the Ca2+ content of the ER from different cell types, estimated by electron microscopic techniques (X-ray microanalysis; energy loss spectroscopy), has been found to be in the range of 5–50 mM, with the highest values in the terminal cisternae of the SR [32]. As to the free Ca2+ concentration within the ER lumen ([Ca2+]ER), different values have been reported, from low μM range to 1–3 mM, depending on the techniques employed [28]. Generally, values above 100 μM are seen in unstimulated cells [33, 34], and a number of reports suggest that in the majority of cells the [Ca2+]ER is between 300 and 800 μM [23, 35–38]. The high [Ca2+]ER facilitates the chaperone action of a number of foldase proteins, and its variations can modulate the ER stress-induced defense mechanisms (e.g., the unfolded protein response, UPR) or activate the apoptotic cell death pathway [39]. Most important, ER luminal Ca2+ is rapidly released in the cytosol upon cell stimulation, by activation of gated ion channels, the IP3Rs and RyRs (see below), present in its membranes. Furthermore, the ER acts as a powerful intracellular Ca2+ buffer, essential for the rapid removal of Ca2+ from the cytosol during physiological stimulation. The steady-state ER Ca2+ level is a dynamic parameter that reflects an equilibrium between ER Ca2+ release (and Ca2+ leak, see below) and ER Ca2+ uptake. Different molecules contribute to reach and maintain the correct steady-state ER Ca2+ content: Ca2+ pumps and Ca2+ releasing channels within ER membranes, as well as Ca2+-binding proteins located in its lumen. Considering the vast multiplicity and variability that characterize this molecular tollkit, it will be discussed in a separated paragraph (see below).

Apart from the well-known pathways responsible for ER Ca2+ uptake and release (see below), the two most enigmatic features linked to ER Ca2+ homeostasis have long been: (1) the mechanism responsible for store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE, also known as CCE) [40], and (2) the nature of the constitutive Ca2+ leak across the ER membrane [41].

As to SOCE (Fig. 1c), i.e., the Ca2+ influx from the extracellular milieu upon ER Ca2+ depletion, it not only allows Ca2+ entry in the cytosol, thus permitting effective refilling of Ca2+ stores, but several data also suggest that SOCE has an important signaling function of its own, by amplifying the short-lasting Ca2+ release from stores and contributing to the regulation of the amplitude and frequency of Ca2+ oscillations [42].

For many years the molecular identity of PM channels involved in SOCE and the functional link between [Ca2+]ER depletion and their activation remained mysterious. In 2005 two independent groups [43, 44] eventually discovered the identity of the [Ca2+]ER sensor(s), i.e., the stromal interaction molecule, STIM1. STIM1 is an ER and PM trans-membrane protein; it possesses a single predicted trans-membrane domain and one EF hand Ca2+-binding domain exposed to the ER lumen. Upon the decrease in [Ca2+]ER, STIM molecules oligomerize in the ER membrane forming aggregates in defined structures called “punctae” in close proximity to PM [45]. Soon after, it was discovered that Orai-1 is the pore subunit forming the SOCs [46–50]. STIM1 molecules, clustered in punctae, directly interact and induce the oligomerization of Orai-1 channels in the PM [51]. A second ER Ca2+-sensor highly homologous to STIM1 was identified and named STIM2 [52]: this molecule is however sensitive to smaller decreases in [Ca2+]ER and is thus presumably involved in the fine tuning of ER Ca2+ content.

On the other side, the molecular identity of the pathway controlling ER Ca2+ leak is still enigmatic. The basal Ca2+ leak is an essential component of the dynamic equilibrium between the rate of Ca2+ uptake and release determining, in the end, the steady state [Ca2+]ER [53]. Several candidates probably contribute directly or indirectly to control this elusive yet fundamental process, including the ribosomal-translocon complex [54–56], channels of the transient receptor potential (TRP) family, such as polycystin-2 (TRPP2) [57], proteins related to neurodegenerative diseases, such as presenilins (PSs) [58], members of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 [37] and Bcl-2-associated X protein-inhibitor-1 families [59] and hemichannel-forming proteins, such as pannexins [60]. The spontaneous activity of the two classical ER Ca2+ release channels, RyRs and IP3Rs, also contributes to the basal ER Ca2+ leak, and some of the above-mentioned molecules (PSs, Bcl-2, BclX, etc., see [61–66]) probably affect ER Ca2+ leak by modulating the basal opening probability of these latter channels. Thus, despite it physiological relevance, the mechanism of ER Ca2+ leak still remains an open question.

ER Ca2+ handling molecular components: pumps, channels and Ca2+-binding proteins

ER Ca2+ uptake depends on the SERCA pump that, in mammals, is coded by three distinct genes (ATP2A1, ATP2A2, ATP2A3). Moreover, each of the three transcripts gives rise, by alternative mRNA splicing, to different isoforms that show a pattern of expression that varies during development and tissue differentiation. SERCA1a and SERCA1b are expressed in adult and neonatal fast-twitch skeletal muscles, respectively. SERCA2a is selectively expressed in heart and slow-twitch skeletal muscles, while the SERCA2b variant is expressed ubiquitously and is thus considered the housekeeping isoform. SERCA3 is only expressed in a limited number of non-muscle cells [4].

The SERCA pump is a 110-kDa protein organized in the membrane as a single polypeptide with ten transmembrane helical domains (M1-M10) and transports two Ca2+ ions per ATP molecule hydrolysed. There are different pharmacological drugs that block SERCA activity and several cellular proteins able to modulate its activity. Among the first, the most used SERCA-specific inhibitors are thapsigargin (TG, isolated from the plant Thapsia garganica), cyclopiazonic acid (CPA, a fungal metabolite from Aspergillus and Penicillum) and the synthetic compound 2,5-di(t-butyl)hydroquinone (tBHQ). CPA and tBHQ have lower affinity for the pump than TG and are reversible in their action, while TG is an irreversible blocker. The three SERCA isoforms and their spliced variants are all similarly sensitive to these drugs, and the inhibition leads to an almost complete ER Ca2+ depletion [67].

SERCA activity can be physiologically regulated by the interaction with different cellular proteins. One of the best studied is phospholamban which interacts with SERCA2a, inhibiting its activity. Protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent phosphorylation of phospholamban relieves this inhibitory effect. In fact, beta adrenergic stimulation of heart cells, via PKA activation, increases Ca2+ uptake by the SR and heart contractility [68]. PS2, but not PS1, on the contrary, inhibits SERCA2b activity [69]. SERCA is also regulated from “inside” the ER lumen. For example, SERCA2b, but not SERCA2a, seems to be regulated by the ER chaperon calreticulin (CRT), shaping IP3-induced Ca2+ oscillations in Xenopus oocytes [70].

As mentioned above, ER Ca2+ release relies on two main gated ion channels: the ubiquitous IP3Rs, and, in many cells, the RyRs. IP3Rs are coded by three different genes, and alternatively spliced isoforms have been identified in mammalian cells; the three full-length sequences are 60–80% homologous, and have distinct and overlapping patterns of expression that vary during differentiation, with most cells expressing more than one isoform [71]. The different isoforms are probably involved in shaping different types of signaling events and, in particular, isoform 3 is thought to be the one mostly involved in the apoptotic process [72, 73].

The IP3R is a ligand-gated ion channel controlled by the second messenger IP3 generated by enzymes of the PLC family, which includes distinct isoforms differing in their activation mechanism. PLCβ is stimulated by G-protein-coupled receptors, while receptor tyrosine kinases, such as the growth factor receptors for epidermal, fibroblast or insulin-like growth factors, activate PLCγ [71]. An additional PLCε, activated by the cAMP-regulated guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor (Epac), has been also identified in several cells [74].

The IP3R consists of a large protein of more than 2,700 residues that can be present as homo- or hetero-tetramers, with a cytoplasmic N-terminus, comprising ~85% of the protein, a hydrophobic region predicted to contain six membrane-spanning helices and a relatively short cytoplasmic C-terminus [75]. At the N-terminus there are both the IP3-binding domain and a more distal “regulatory” domain. Binding of IP3 gates the channel open, and the opening of the channel is modulated by the linker region. The latter contains consensus sequences for phosphorylation, proteolytic cleavage and binding by different protein modulators and ATP, integrating different cellular signaling pathways or metabolic states with the IP3R functionality. All these structure-function relationships have been thoroughly investigated, and several recent reviews have been published on this topic (see for example [71, 75, 76]). Moreover, several molecules—such as homer, protein phosphatases (PP1, PP2A), RACK1, chromogranin, Na+/K+-ATPase, carbonic anhydrase-related protein (CARP) and IRBIT—interact with the IP3Rs and modulate their activity, suggesting that the receptor can form multi-molecular complexes, different from cell type to cell type, and functioning as a center for signaling cascades [75]. The more essential regulator of IP3Rs is however cytosolic Ca2+ itself: modest increases in [Ca2+]i potentiate the responses to IP3, while more substantial increases inhibit them [71]. The accepted view is that IP3 and Ca2+ are the physiological agonists of IP3R and that IP3 binding does not gate the channel per se, but tunes it to respond to Ca2+. IP3Rs seem to be also regulated by pH, Ca2+ concentration and redox state within the ER lumen mediated by the resident ER protein of the thioredoxin family, ERp44 [77].

The IP3R channel selects rather poorly between cations, but this is compensated by the fact that Ca2+ is the only permeant ion with an appreciable concentration gradient across the ER membrane; moreover, the channel has a large conductance, and even the opening of a single IP3R can generate a physiologically significant Ca2+ signal [71]. These features allow IP3R to generate local and, through the propagation of the signal between neighboring IP3Rs, widespread Ca2+ signals, inducing different elementary Ca2+ release events, such as Ca2+ blips, puffs and waves [78]. Generally, by the opening of a single (or very few) IP3Rs, the smallest of these Ca2+ signals (a Ca2+ blip), is generated, while a Ca2+ puff (larger but still spatially restricted) has been estimated to depend on the simultaneous recruitment of between 5 and 70 receptors. As the stimulus intensity increases still further, puffs become frequent enough to allow the activation of many IP3R clusters and the propagation of regenerative Ca2+ waves that can invade the whole cell [79]. Since all these events depend on the spacing of IP3Rs, several studies have been focused on what the molecular determinants are and/or on interactions that cause IP3R to be expressed with different densities in specific sub-cellular locations (see [79] for a recent review). IP3-generating agonists themselves can evoke IP3R clustering on ER membranes that seem to correlates with cytosolic IP3 concentrations and Ca2+ increases, inducing a conformational change in the receptor [80–83], providing further flexibility to IP3-mediated signaling.

The other major Ca2+-releasing channel in the ER membranes is the RyR (from the name of the plant alkaloid ryanodine, which binds to the receptor with high affinity and specificity, used to evaluate the functional state of the channel). Also RyRs exist in three isoforms (RyR1, -2 and -3), 65% identical in sequence, coded by three distinct genes with different patterns of expression within tissues: RyR1 is primarily expressed in skeletal muscles, RyR2 is the cardiac isoform (but it is also expressed at high levels in Purkinje cells of cerebellum and in neurons of the cerebral cortex), while RyR3, initially referred to as the brain isoform, is ubiquitously expressed at low levels. No spliced variant is known. In skeletal and cardiac muscle, RyR1 and RyR2, respectively, are responsible for the release of Ca2+ from the SR during excitation-contraction coupling, either by mechanical coupling to dihydropyridine receptor, DHPR, in skeletal muscle [84] or by Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) in cardiac muscle [85]. RyRs also play important roles in signal transduction in the nervous system where they contribute to secretion, synaptic plasticity, learning and apoptosis [86, 87].

The channel is formed by homo-tetramers, reaching a molecular mass of >2 MDa (each subunit is >550 kDa), representing the largest known ion channels. The channel activity is modulated directly or indirectly by several molecules and ions, such as PKA, FK506-binding proteins (FKBP12 and 12.6), calmodulin (CaM), Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinase II, calsequestrin (CSQ), triadin, junctin, Ca2+ and Mg2+ (see [88] and [89] for recent reviews). Its structure has been the subject of several studies leading to the conclusion that more than 4,000 amino acids at the N-terminus comprise its enormous cytosolic domain (where most of the RyRs modulators interact), while the trans-membrane domain of the receptor, forming the ion conducting pore, is contained in the C-terminal ~800 residues [90].

While in skeletal muscle RyR1 opening is primarily (or exclusively) due to the electromechanical coupling with DHPR, the major gating mechanism of RyR2 and RyR3 is CICR: in this case, the opening of RyRs is due to the local Ca2+ increase occurring in the proximity of PM Ca2+ channels, as initially demonstrated for cardiac muscle cells [85, 90]; CICR can be also induced by Ca2+ release from neighboring ER channels, such as IP3Rs or RyRs, in a regenerative wave. RyRs can be gated also by other agents and, among these, the most prominent is cADPR, a metabolite of the co-enzyme β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD). cADPR is generated by the activation of enzymes called ADP-ribosyl cyclases, in particular the ectoenzyme CD38 [91]. The cADPR gating of RyRs (in particular RyR-2 and/or -3; [92]) was first demonstrated in sea urchin egg homogenates [93, 94] and then shown to be effective in many other cell types [95]. Its capacity in inducing Ca2+ release was demonstrated using different approaches, i.e., by perfusion into cells using a patch pipette or by light-dependent uncaging; this capacity is blocked by pre-treating cells with TG and dantrolene [96] (but see also [97] and [98] for recent reviews); it is still unclear, however, whether cADPR interacts with RyR directly or via the RyR-interacting protein FK506-binding protein 12.6 [99–101]. cADPR-mediated Ca2+ signaling appears particularly relevant in smooth muscle cells [102], pancreatic acinar cells [103] and in the nervous system [104].

Inside the ER, Ca2+ is bound by a number of luminal Ca2+-binding proteins, most of them acting both as buffers and protein chaperones [105, 106], such as CRT, CSQ, GRP78, GRP94 and Calnexin (see below). These proteins possess a variable number of Ca2+-binding sites (from 1 to ~50 per molecule), while their relatively low affinity for the cation ensures, on the one side, its rapid diffusion through the organelle and, on the other, its prompt release upon opening of the release channels.

More than 50% of the total ER Ca2+ content is bound to CRT [107]: a 46-kDa protein with a large Ca2+-binding capacity (1 mol of CRT can bind 25 mol of Ca2+) and low affinity (K d around 2 mM, but it has one high-affinity Ca2+-binding site) [108]; accordingly, conditions that increase/decrease CRT levels strongly affect ER Ca2+ storing capacity [109–112]. The 90-kDa Calnexin shares high homology with CRT but is an integral membrane protein [113].

Bip/GRP78 [114] and GRP94 [115, 116] are two ER molecular chaperones also acting as ER Ca2+ buffers. Also some oxido-reductases in ER lumen have Ca2+-binding properties, e.g., protein-disulfide isomerase (PDI) [117] and ERCalcistorin/PDI [118].

The 44-kDa CSQ [119]) is, instead, the main Ca2+-binding protein within the SR (it is selectively located in the terminal cysternae), and, similarly to CRT, it possesses a large Ca2+-binding capacity (1 mol of protein binds around 50 mol of Ca2+) and relatively low affinity (1 mM); interestingly, CSQ can also act as an intralumenal Ca2+ sensor by changing its conformation according to [Ca2+] (it forms fibrils when [Ca2+]SR increases) and it can modulate RyRs gating [120]. Two isoforms of CSQ are known, a cardiac and a skeletal isoform. CSQ is expressed not only in striated muscle, but also in some smooth muscles and in avian cerebellar Purkinje neurons [121, 122]. Other SR-specific Ca2+-binding proteins are the 53-kDa sarcalumenin, capable of binding around 35 mol of Ca2+ for 1 mol of protein [123], and the 165-kDa histidine-rich Ca2+-binding protein [124].

Finally, it is noteworthy to stress that the feedback circle of ER Ca2+ homeostasis is completed by the major regulation of its Ca2+-filling and -releasing mechanisms by [Ca2+]ER itself. Both SERCA and IP3R/RyR activities are indeed modulated by the free Ca2+ within ER lumen: low ER Ca2+ levels accelerate Ca2+ pumps and inhibit Ca2+-releasing channels, while high [Ca2+]ER does the opposite [71, 89, 125].

ER Ca2+ handling and human diseases

Maintaining the correct [Ca2+] within the ER is of crucial importance for cell viability and, for that purpose, the orchestrated activity of all the ER Ca2+ handling molecules is required. Several human diseases, indeed, are known to be linked to specific dysfunctions of many of them.

The importance of a correct SERCA pump activity, for example, is underlined by the fact that mutations in its genes or alterations in its level of expression are associated with different diseases, ranging from the autosomal dominant skin disorder Darier’s disease (with more than 130 mutations in the SERCA2 gene; [126]), the recessive myopathy Brody’s disease (due to SERCA1 gene mutations; [127]), to different models of heart failure where a decreased level of SERCA pump as well as a reduced SR Ca2+ transport and SR Ca2+ content have been detected (see [128] for a recent review). In addition, a relationship between cancer and SERCA pump dysfunctions has been reported [129], whereas an association of specific sequence variants of the pump with type II diabetes has suggested a possible contribution of SERCA to this disease’s susceptibility [130]. Recently, an altered SERCA2b pump activity was proposed to contribute to Ca2+ dysregulation induced by PS mutations linked to familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD) [69, 131]. The pump was shown to physically interact with wild-type endogenous PS2 [131], which behaves physiologically as a SERCA brake [69]. Moreover, the finding that pharmacological and genetic modulation of SERCA pump activity altered amyloid-β production suggests a possible role for this pump in the pathogenesis of AD [131].

Because of its ubiquitous expression and its key role in regulating diverse cell physiological processes in many cell types, also the IP3R has been involved in the pathogenesis of several diseases, although to date the only known human diseases that have been definitively linked to a mutation(s) in its genes are spinocerebellar ataxias 15 and 16 [132–134] (perhaps due to the functional redundancy of multiple IP3R isoforms expressed in most cells). On the other hand, IP3R activity can be affected by the expression of several disease-associated proteins, such as huntingtin (Htt) and Htt-associated protein1 in Huntington’s Disease [135] and PS mutants linked to FAD [63, 64]. In both cases an enhanced IP3 sensitivity of the receptor has been reported that may contribute to the progression of the diseases by exaggerated Ca2+ release-dependent neuronal death.

IP3Rs are indeed directly involved in apoptosis: cytochrome c, a key component of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, once released from mitochondria, is able to bind to the receptor abolishing its Ca2+-dependent inhibition and thus keeping it open in the presence of increased [Ca2+]i [136]. The IP3R-cytochrome c complex was shown to be important for sustained oscillatory cytosolic Ca2+ release with complete depletion of ER Ca2+ stores, finally resulting in apoptosis [136]. Moreover, recent studies indicate that different members of the large family of apoptosis-regulating proteins, the Bcl-2 family, can interact with the IP3R Ca2+ channel on the ER membrane and regulate its activity, thereby modulating pro-apoptotic sustained Ca2+ elevation (see [137] and [138] for recent reviews). Interestingly, IP3Rs have been found to be present in mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs; [139, 140]) and, through interaction with different ER and mitochondrial proteins, involved in ER-mitochondria interplay, a key feature that modulates cell death, mitochondrial activation and spatio-temporal tuning of cellular Ca2+ responses [141].

As to RyRs, different mutations in their genes are associated with human disorders such as catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (RyR2), central core disease and malignant hyperthermia (RyR1) [142]. Furthermore, alterations in RyR post-translational modifications and remodeling of the RyR channel macromolecular complexes are associated with acquired muscle pathologies including skeletal muscle fatigue and heart failure [143, 144]. Similarly to IP3Rs, also RyRs have been reported to be involved in AD pathogenesis and, in particular, an enhanced release of Ca2+ through these gated channels has been suggested as a possible pathogenic mechanism linked to PS mutations in FAD. This might be due to an increased expression of RyR isoforms (RyR2) in FAD animal model brains [145–147], as well as to a facilitated gating of these receptors [65, 66]. The upregulation of RyR3 type in cortical neurons, however, has been shown to be neuroprotective in a specific transgenic AD mouse model [148].

The Golgi apparatus

The GA is an intracellular organelle with a key role in lipid and protein post-translational modification and sorting. Its structure is quite unique, and, in higher eukaryotes, it can be schematically viewed as being composed of three main compartments: the cis-, medial and trans-Golgi. All its flattened cisternae are arranged in polarized stacks, with a cis-side associated with a tubular reticular network of membranes (cis-Golgi network, CGN), a medial area of disc-shaped cisternae and a trans-side associated with another tubular reticular network (trans-Golgi network, TGN) [149]. This peculiar architecture is very dynamic and depends on the balance of anterograde and retrograde vesicle traffic through the Golgi, between ER and the GA, and between this latter and the other cellular compartments.

A similar polarization has also been found in some GA functions: the majority of GA enzymes, for example, acting on proteins through the biosynthetic pathway, are indeed strictly compartmentalized (cis- or medial or trans-GA cisternae), according to their sequential and complementary actions on the maturating protein [150].

Numerous direct and indirect evidence supported the idea that the GA also plays a key role as an intracellular Ca2+ store. In the 1990s, using both ion microscopy [151] and electron energy loss spectroscopy [22], it was shown that the Golgi can store high amounts of Ca2+ and that specific functions of the GA, as well as the activity of several resident enzymes, are critically dependent on Golgi Ca2+ content [152–155]. As soon as a methodology became available to monitor directly the free Ca2+ concentration in the Golgi lumen of living cells [an aequorin (Aeq)-based Ca2+ probe fused to the first 69 AA of the Golgi resident protein sialyl-transferase; [67]], it became clear that the GA represents a dynamic Ca2+-storing organelle, capable of releasing Ca2+ into the cytosol upon cell activation with an IP3-generating agonist. Moreover, these authors also demonstrated that the GA maintains, under resting conditions, high [Ca2+] in its lumen due to the activity of a typical ER Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) and of another Ca2+ pump, with distinct pharmacological properties, the SPCA1 [156]. The accrued data [157–163] indicate that the GA is an IP3-sensitive, rapidly mobilizable, intracellular Ca2+ store with a potential role also in shaping cytosolic Ca2+ responses.

Molecularly, the GA contains all the essential features of a Ca2+-storage organelle (Fig. 1d): pumps for Ca2+ uptake, channels for Ca2+ release and Ca2+-binding proteins for Ca2+ storage. As to the first, SERCA Ca2+ pumps have been demonstrated to be present and functional at the Golgi level [67, 157, 159–162, 164, 165]. As mentioned above, in addition to that, data from different laboratories [67, 157, 161, 166] clearly indicate the presence of another ATP-dependent Ca2+-pumping mechanism (not expressed at significant levels within the ER) in this cell compartment: the SPCA1 (see [156] for a recent review). This molecule (present in humans in two isoforms: SPCA1, ubiquitously expressed [167]; SPCA2, more restricted to brain cells [168, 169]) is a single subunit trans-membrane protein containing, unlike SERCA, only one high-affinity Ca2+-binding site. SPCAs also transport Mn2+ with high affinity, and this property represents a major functional difference as compared to SERCAs.

The two types of Ca2+-ATPases, SERCA2 and SPCA1, contribute differentially to the total uptake of Ca2+ into the GA [159, 166] and appear to be localized in different GA sub-compartments: in keratinocytes the SERCA2 was found to be enriched in the cis-Golgi membrane fractions, while SPCA1 was mainly present in the trans-Golgi membranes [170]. SPCA1 immunoreactivity has been found also in dense-core secretory vesicles of pancreatic β-cells [171], suggesting the possibility that this latter pump is predominantly expressed in later compartments of the secretory pathway. As to SPCA2, its sub-cellular localization is not clear, although a partial co-localization with the trans-Golgi marker TGN38 has been reported in hippocampal neurons [168].

The GA is also equipped with Ca2+-releasing channels: as already mentioned, the presence of IP3Rs was demonstrated by different groups [67, 158–162, 164, 172], while the other major intracellular Ca2+-releasing channel, the RyR, was initially suggested to be expressed in this compartment only on the basis of its staining with a fluorescent ryanodine derivative [173], but more recently, its activation (by caffeine or Ca2+) has been shown to cause a drop in the [Ca2+] of the trans-Golgi in cardiac myocytes (see below and [174]).

As far as luminal Ca2+-binding proteins are concerned, the GA contains several proteins (Cab45, CALNUC, p54/NEFA and calumenin); with the exception of Cab45, none of these have been found also in the ER lumen [175]. Among these, the most abundant and better characterized is CALNUC, an EF-hand, Ca2+-binding resident protein of the CGN and cis-Golgi cisternae [176] with low Ca2+-binding capacity. Studies in cells over-expressing this protein suggest that CALNUC plays a major role in the Ca2+ buffering within the IP3-sensitive Golgi compartment(s) [157].

All the molecular components necessary for the function of a Ca2+ store are, thus, present within the GA. Additional works, however, suggested that distinct Golgi sub-compartments could be endowed with different molecular components, supporting the idea that the GA is heterogeneous in terms of Ca2+ handling properties. In particular, the SPCA1-containing GA sub-compartment seems insensitive (or mildly sensitive) to IP3-generating agonists [161, 164], and some kinetic features of Ca2+ release from the GA are clearly distinguished from those of the ER with a faster termination of the event in the former case [160]. These indirect hints of Golgi Ca2+ handling heterogeneity were finally directly confirmed using a new fluorescent Ca2+ indicator specifically targeted to the trans-Golgi (Fig. 2e) [174]. By this means, measuring at the single cell level the [Ca2+] within this compartment in a quantitative and dynamic way, it was possible to show that the trans-Golgi does not use SERCA pumps, but only SPCA1, and does not release Ca2+ in response to IP3 generation. On the other hand, caffeine and KCl stimulation (i.e., cytosolic Ca2+ rise), by activating RyRs, caused a decrease in cardiomyocytes’ trans-Golgi [Ca2+], making this particular GA sub-compartment very similar to insulin-secreting granules of pancreatic β cells [177].

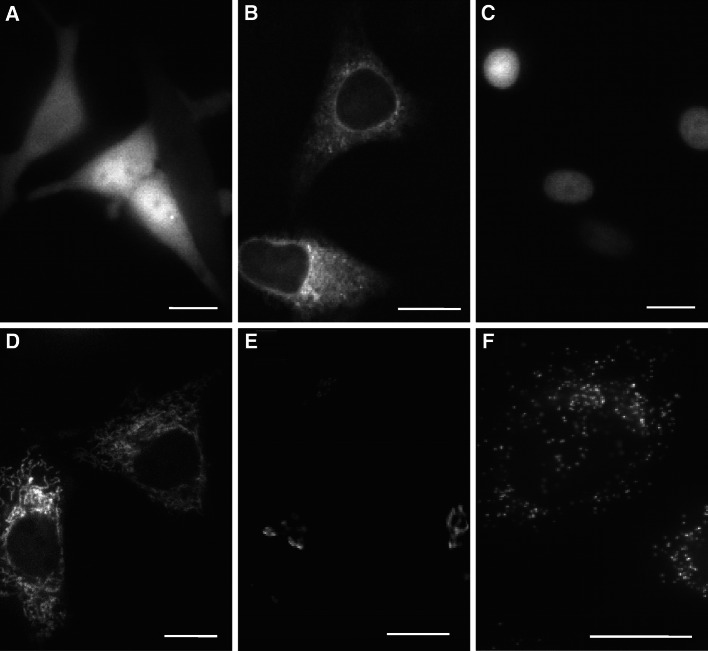

Fig. 2.

Sub-cellular targeting of different Cameleon Ca2+ probes. Representative images collected with an epifluorescence microscope (excitation 430 nm, emission 530 nm). Panel a the cytosolic D1cpv probe [210] homogeneously stains the cytoplasm of SH-SY5Y cells; panel b the ER-D1 probe is localized within the ER of SH-SY5Y cells; panel c the H2B-D1cpv probe [210, 290] is targeted to the nucleoplasm of SH-SY5Y cells; panel d the 4mt-D1cpv probe [290] is expressed in the mitochondrial matrix of SH-SY5Y cells; panel e the Go-D1cpv probe [169] localizes in the trans-Golgi compartment of HeLa cells; panel f the KVK-SKL-D3cpv probe [357] is selectively targeted to the peroxisomal matrix of HeLa cells. All these probes have been successfully used to monitor Ca2+ dynamics in their specific sub-cellular compartments. Scale bars 10 μm

Concerning the other GA sub-compartments, our laboratory is presently testing another Cameleon Ca2+ indicator [178] fused to the cis-Golgi-targeting sequence of the enzyme β1,6 N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase [179]. The new probe co-localizes with the cis-Golgi marker GM130, and preliminary results indicate that this compartment is heterogeneous in terms of [Ca2+] at rest, sensitivity to IP3-generating stimuli as well as mechanisms of Ca2+ uptake (Lissandron et al. unpublished results).

Thus, even with still incomplete data on the finer heterogeneity in GA Ca2+ handling, it is possible to conclude that this organelle is composed of sub-compartments that are spatially very close, and in very rapid equilibrium with each other, but still able to maintain quite substantial differences in terms of Ca2+ concentration and response to external stimuli.

It has been known for many years that [Ca2+] within the GA is fundamental for several processes occurring in the organelle [152, 180, 181], and more recently it has also been shown that SPCA1 downregulation affects markedly both the morphology and the functionality of the entire GA [174, 182]. In humans, mutations in one allele for SPCA1 cause the blistering dermatosis called Hailey-Hailey disease. Keratinocytes of patients show several defects in protein sorting, increased cytosolic Ca2+ levels and impaired Ca2+ signaling [156, 183, 184]. In some cases, Hailey-Hailey skin lesions eventually evolve into squamous carcinomas [185]. Of interest, recently an association between cancer and SPCA1 has been reported, although of opposite nature: significantly elevated SPCA1 levels have been described in basal-like breast cancers, while the inhibition of SPCA1 in a breast cancer cell line led to a pronounced alteration in cell growth, morphology and in the processing of insulin-like growth factor receptors, with their functional levels significantly reduced [186]. Thus, changes in SPCA1 expression can affect, presumably by altering GA (but also secretory vesicles, see below) Ca2+ handling, the processing of proteins important in tumor progression.

The nucleus

The nucleus represents the eucaryotic cell site in which genomic material is separated from the cytosolic compartment. This allows the DNA, encoding the genes responsible for the determination of cell fate, and the molecular machineries, responsible for its organization and transcription, to be protected and to be regulated by specific signals that must cross a physical barrier, the NE, to become effective. From a structural point of view, the nucleus is no longer considered as an homogeneous organelle in which DNA is processed and organized, but it is rather a complex and dynamic compartment with different sub-regions, including nucleolus, “chromosome territories,” Cajal bodies, promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies and SC35 domains (reviewed in [187]).

As universal second messenger, Ca2+ is also involved in the regulation of nuclear functions, as demonstrated by the fact that cytosolic Ca2+ transients modulate the transcription of several genes [188–190], and, thus, the control of Ca2+ homeostasis at the nuclear level is of great interest.

The critical issue in addressing nuclear Ca2+ handling is understanding whether nuclear Ca2+ signals come from cytosolic waves crossing the NE or from independent signaling events originating within the nucleus itself [191]. On this aspect, the nature of the NE plays a key role, since its permeability to, or, vice-versa, its capability of filtering, cytosolic Ca2+ signals is critical in rendering the nucleus an autonomous and independent Ca2+ signaling compartment.

The NE is organized as a double membrane—the outer nuclear membrane (ONM), exposed to the cytosol, and the inner nuclear membrane (INM), facing the nucleoplasm-isolating the perinuclear space (PNS) that indeed is in continuity with the lumen of the ER: thus, the NE is commonly considered as a specialized sub-compartment of the ER (reviewed in [192]). Indeed, the NE is reported to be endowed with Ca2+ signaling players similar to those present in ER membranes (Fig. 1b) (i.e., SERCA pumps, IP3Rs, RyRs, as well as NAADP receptors; see below), thus with a complete toolkit to actively modulate Ca2+ dynamics [193–205]. The NE is also equipped with large protein pores (Nuclear Pore Complex, NPC) that span both the outer and inner nuclear membranes and mediate the transport of macromolecules (proteins, RNAs) between the nucleus and cytoplasm [206]. Although molecules larger than 50–70 kDa require energy-dependent transport across NPCs, these large protein complexes are thought to be freely permeable to molecules (including ions) smaller than 20 kDa [207]. Consequently, Ca2+ ions should be able to diffuse freely through NPCs and thus to cross the NE very rapidly [208, 209].

As discussed below, the most accepted view, at least in mammalian cells, is that Ca2+ very rapidly diffuses across the NE, and, thus, nuclear Ca2+ elevations mirror cytosolic Ca2+ changes. On the other hand, however, independent nuclear Ca2+ signaling events (originating from the NE or from other specialized structures within the nucleus itself) have been described by some groups [210, 211] (see also [212]).

As to the first possibility, strong evidence comes from works demonstrating that nuclear Ca2+ kinetics closely follow cytosolic changes [35, 213–216]. Interestingly, most of these reports are based on genetically encoded Ca2+ probes, with a specific targeting to the nucleoplasmic compartment (Fig. 2c) or on nuclear-trapped dextran-bound Ca2+ indicators [217], allowing the measurement of Ca2+ changes without any interference by off-target signals. Other groups drew similar conclusions also employing common Ca2+ indicators but evaluating Ca2+ kinetics in recognizable nuclear sub-regions [218–224]. Of interest, when high-resolution kinetic analysis was employed, it was revealed that a short delay exists between the rise in cytosolic and nuclear [Ca2+], about 100–200 ms. This delay was better appreciated with protein-based Ca2+ indicators or dextran-bound dyes, confirming that small Ca2+ probes increase the apparent diffusion rate of Ca2+.

According to other groups, the NE, at least under some conditions, represents a substantial barrier to Ca2+ diffusion from the cytoplasm: it permits the rapid equilibration of Ca2+ between cytosol and nucleoplasm at low cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, but it is able to filter large cytosolic Ca2+ increases [225–228]. Other groups reported that only sustained Ca2+ increases in the cytosol are able to permeate the NE [229]. The basis for hypothesizing a barrier role of the NE to Ca2+ diffusion is the knowledge that NPC permeability can be modulated by different cell parameters such as cytosolic Ca2+, ATP levels and Ca2+ content in the NE lumen [230–233]. However, it should be stressed that these parameters have been shown to alter the NE permeability to large molecules (MW >20 kDa) and not to small ions (see for example [234]).

Finally, it should also be mentioned that Ca2+ release from the NE, as well as its diffusion from cytosol to the nucleoplasm, could be facilitated by structural features, such as invaginations of the NE, creating “tunnels” deep inside the nucleus [235–237]. The presence of a fine intra-nuclear branching of NE, the “nucleoplasmic reticulum,” endowed with IP3Rs and RyRs has also been reported [203, 238–240]. Some reports have even hypothesized the existence in the nucleoplasm of a pool of small vesicles containing chromogranin B and IP3Rs capable of accumulating and releasing Ca2+ upon stimulation [241, 242].

Independently from their source, nuclear Ca2+ rises could have increased duration and/or amplitude compared to cytosolic ones because of the different nuclear Ca2+-buffering capacity that leads to slower recovery after a Ca2+ rise and rapid diffusion within the entire compartment [218, 219, 243, 244]. This property probably allows the nucleus to act as an integrator of cytosolic Ca2+ signals: if single cytosolic Ca2+ events occur with sufficient frequency and amplitude, in the nucleoplasmic compartment they would sum up, leading to longer-lasting Ca2+ increases [223, 245].

Mitochondria

Mitochondria are formed by two membranes, an outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), facing the cytosol and with a loose permeability to ions and small molecules, and an inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM), forming several invaginations (“cristae”) that increase its total surface area (and can isolate some regions of the inter-membrane space, IMS); the IMM encloses the mitochondrial matrix, where mitochondrial DNA and enzymes accounting for the main mitochondrial functions are isolated from the rest of the cell [246, 247]. Mitochondria are the cell powerhouses since in their IMM and matrix operate the reactions responsible for the production of large amount of ATP generated by Krebs cycle and aerobic respiration. Thus, mitochondria provide cells with the major part of the ATP required to maintain cell homeostasis. On the other hand, mitochondria are also a critical site for the initiation of programmed cell death (apoptosis). It is noteworthy that both these opposite functions (and the fine balance between them) are tightly modulated by Ca2+ signals reaching the mitochondrial matrix, and it is thus not surprising that mitochondria are key players in Ca2+ homeostasis [248, 249].

Although mitochondria are often simplistically depicted as individual double-membrane organelles, in most of the cells they constitute an interconnected network of elongated organelles that continuously undergoes morphological modifications and movements [247, 250]. In particular, the shape of the organelle is a balance of fusion and fission events regulated by different proteins (see [250] for a recent review). Although mitochondrial fission is often observed during the apoptotic process [251], it does not represent per se a detrimental phenomenon: actually, it is a common way to increase the number of mitochondria (e.g., during mitosis) and, even during a toxic event, it can be seen as an attempt to avoid irreversible damage, i.e., the impaired mitochondria undergo fission and detach themselves from the network limiting the spread of an insult to the entire cell [252].

For a long time it was believed that mitochondria did not participate in physiological Ca2+ handling, but today it is unquestionable that mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis is crucial in modulating several fundamental functions, from cell energetics to apoptosis.

First of all, mitochondrial movement and localization within the cell are dependent on localized Ca2+ signals with the molecular machinery responsible for mitochondrial movement regulated by Ca2+ itself [253]. Mitochondria are transported along microtubules and are also subject to actin-dependent fine adjustments of their position [254]. The anterograde transport of mitochondria along microtubules is mediated by specific kinesins [255], bound to a molecular adaptor, e.g., Milton [256] and Miro; Miro, in particular, possesses two EF domains that render the protein sensitive to Ca2+: mitochondrial transport is normally stopped when high [Ca2+] is sensed by Miro [257, 258] possibly in order to ensure efficient local ATP synthesis and Ca2+ buffering capacity to a region in need of them. This phenomenon may be of particular importance in neurons, where regions that require energy supply and high Ca2+ buffering capacity (the synapses) can be at long distances from the site of mitochondria biogenesis (the soma)[259] (also reviewed in [260]).

Secondly, Ca2+ modulates mitochondria metabolism (Fig. 3b). Rises in matrix Ca2+ are able to regulate the activity of some enzymes involved in providing reducing equivalent to the respiratory chain (and thus to fuel ATP production), in particular three dehydrogenases (pyruvate-, α-ketoglutarate- and isocitrate-dehydrogenases); a fourth one, glycerophosphate dehydrogenase, whose activity is Ca2+-dependent, is localized in the IMM, with its catalytic domain exposed to the IMS [261]. Given that the IMS is in rapid equilibrium with cytosolic Ca2+ [262], activation of glycerophosphate dehydrogenase does not require, unlike the matrix enzymes, the uptake of the cation into the matrix. Similarly, the Ca2+ concentration in the IMS regulates the activity of the aspartate/glutamate carriers [263, 264].

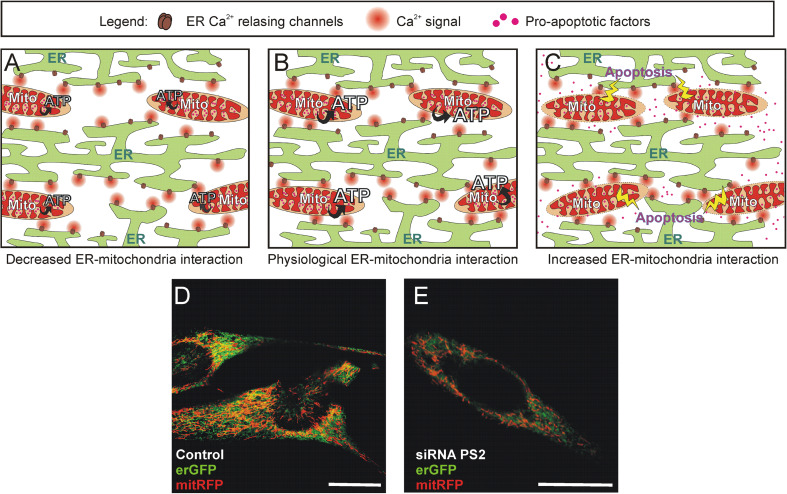

Fig. 3.

ER-mitochondria interaction and Ca2+ cross-talk. a–c Schematic representation of possible effects due to variations in ER-mitochondria interaction. In physiological conditions (panel b) mitochondria sense Ca2+ releasing events from ER that tune their metabolic activity (i.e., ATP production); if ER-mitochondria interaction is decreased (panel a), ER signals reaching mitochondria are less and less intense; thus mitochondrial activity is under-stimulated; an increase in ER-mitochondria interaction (panel c) can expose mitochondria to excessive Ca2+ stimulations, enhancing the probability of triggering the apoptotic cascade. d–e Confocal images of SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells showing the effects of a decreased expression of presenilin-2, a protein able to modulate ER-mitochondria interaction. Cells were co-transfected with a green fluorescent protein targeted to the ER (erGFP) and a red fluorescent protein located in the mitochondria matrix (mitRFP), and treated with control (panel d) or presenilin-2 (panel e) siRNAs. The merge images are shown, and yellow pixels (overlapping of green and red fluorescences) indicate the proximity of the two organelles: decreased yellow pixels can be observed in cells in which presenilin-2 levels were down-regulated by specific siRNAs (panel e). Scale bars 10 μm

Finally, mitochondria are clearly linked to the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, and also this latter process is modulated by Ca2+. The organelles are endowed with several proteins involved in cell apoptosis, such as Bcl-2 family members and pro-apoptotic soluble factors (e.g., cytochrome c, AIF, etc.). Bcl-2 family members are localized on the cytosolic surface of the OMM, while the pro-apoptotic mitochondrial proteins are trapped either in the IMS or in the matrix. These factors can thus be released in the cytosol either through the formation of pores on the OMM (cytochrome c) or when the permeability of both the OMM and IMM are drastically increased by the opening of the so-called permeability transition pore (mPTP). In this latter case, not only cytochrome c, but also the matrix pro-apoptotic factors are released into the cytoplasm and activate the caspase cascade (Fig. 3c). A number of toxic insults lead to mPTP opening, most commonly when the mitochondrial matrix is overloaded with Ca2+ or when a “normal” mitochondrial Ca2+ increase is combined with another sub-threshold toxic insult [141, 265, 266]. This latter feature renders mitochondria a sort of “coincidence detectors” of pro-apoptotic signals: intra-mitochondrial Ca2+ rises, that in themselves would be simply modulators of mitochondrial activity, become deadly if combined with another mild toxic event [141, 265–268].

Ca2+ uptake and release in mitochondria: the role of cell architecture and the molecular components of the organelle Ca2+ toolkit

The discovery of the capacity of isolated mitochondria to take up Ca2+ from the medium dates back to the early 1960s [269, 270], but the molecular identity of the proteins involved in mitochondria Ca2+ uptake and extrusion has remained elusive until a few months ago.

Concerning the Ca2+ entry into mitochondria (Fig. 1e), the critical barrier is formed by the IMM, since OMM is substantially freely permeable to Ca2+, through the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) [271]. The driving force for Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria is the IMM potential (Δψm), which is negative (−180 mV) on the inner side of the membrane because of the activity of the respiratory chain (reviewed in [246, 248]). This huge driving force should bring into the mitochondrial matrix massive amounts of Ca2+ also under resting conditions, but the existence of extrusion mechanisms (see below) and the low affinity for Ca2+ (K d around 10–20 μM) of the molecule required for its entry (the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter, MCU, see below) ensures that mitochondrial [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]m) in living cells remains low at rest, similar to the [Ca2+]i, i.e., around 100 nM [272–274]. In addition, the low MCU Ca2+ affinity, as estimated in isolated mitochondria, for a long time suggested that mitochondria could hardly take up Ca2+ in physiological conditions, since bulk cytosolic Ca2+ rises never reach values compatible with the low K d of the MCU. However, when it became possible to measure selectively the dynamics of [Ca2+]m in living cells (through genetically encoded Ca2+ probes specifically targeted to the mitochondrial matrix; Fig. 2d), it was immediately clear that, in living cells, upon relatively modest cytosolic Ca2+ rises (1–2 μM), mitochondria can instead take up Ca2+ rapidly reaching values in the matrix as high as tens or even hundreds micromolar [275]. This paradox was solved by hypothesizing that local high [Ca2+]i can be transiently generated in the proximity of open Ca2+ channels (in the ER or the PM). Strategically localized mitochondria can sense these microdomains of high [Ca2+] and, consequentially, take up Ca2+ transiently, but very efficiently [276]. The “Ca2+ microdomain hypothesis” [277, 278] was supported by the finding that mitochondria are indeed located within living cells in close proximity to ER membranes [262, 274], i.e., in juxtaposition with the ER Ca2+-releasing channels IP3Rs and RyRs. A variety of indirect evidence supported this hypothesis, but only very recently it was possible to directly demonstrate the existence of such Ca2+ microdomains: by employing FRET-based Ca2+ probes targeted to the cytosolic side of OMM, it was demonstrated that, upon cell stimulation and Ca2+ release from the ER, mitochondria are indeed exposed to local [Ca2+] hot spots [215, 279].

The existence of high Ca2+ microdomains in proximity to mitochondria is thus the prerequisite for allowing mitochondria to take up Ca2+ very rapidly. As mentioned above, the molecular nature of the MCU was investigated for many years, and several proteins have been proposed to be involved in this molecular complex, including the uncoupling proteins UCP2 and UCP3, a mitochondrial RyR and the Ca2+/H+ antiporter Letm1, although their identity as MCU was highly controversial (reviewed in [248], but see also [280]). One key paper by Kirichov et al. [281], however, directly demonstrated, by patch clamping of isolated mitoplasts (mitochondria without the OMM), what had been suggested several years ago [282], i.e., that the MCU is a gated Ca2+ channel. Recently, combining bioinformatics and genomics approaches the group of Mootha identified a molecule (MICU1), located in the IMM and possessing two EF hands, whose downregulation strongly inhibits efficient mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. Although the authors themselves argued that MICU1 could not be the MCU itself, the data suggested that it may represent the Ca2+ sensor of a multimeric complex responsible for mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake [283]. Only a few months ago, the group of Rizzuto and that of Mootha independently demonstrated that a 40-kDa protein present in the IMM is the long-searched-for MCU. The first group also showed that this MCU expressed in bacteria forms ion channels when incorporated in black lipid films, with electrophysiological characteristics similar to those described in the intact organelles by Clapham and colleagues [281], and is sensitive to the well-known MCU inhibitor Ruthenium Red. Both groups concluded that this protein is the channel-forming unit of the MCU [284, 285]. Baughman et al. showed also that MCU and MICU1 co-precipitate, suggesting a close interaction between the two proteins [284].

The privileged interaction between ER and mitochondria, and their Ca2+ cross-talk, has important consequences for cell life [136] (Fig. 3): in particular, it has been recently demonstrated that, even in resting condition, a constitutive Ca2+ transfer from the ER to mitochondria is critical for maintaining the organelle’s proper functions and to ensure the ATP production required for cell activities [286]; on the other hand, excessive Ca2+ signals from the ER towards mitochondria are pro-apoptotic. For this reason, mitochondria can be juxtaposed to ER by specific linkers and kept at a given distance (between 10 and 25 nm). It has been shown that decreasing the distance between ER and mitochondria enhances apoptotic susceptibility of the cell [287] or can help the cell in overcoming stress conditions by ensuring higher ATP supply [288]. The proteins mediating or influencing ER-mitochondria interactions are the subject of great interest, and their number is progressively increasing (Fig. 1g): the grp75 chaperone was reported to link IP3Rs and VDAC on the OMM [289], while the mitochondrial fusion protein mitofusin2 (Mfn2) was shown to tether ER to mitochondria by homotypic interactions, being expressed on both the OMM and ER membranes [290]. The interaction between the ER resident protein Bap31 and the OMM protein Fis-1 has also been shown to contribute to link ER and mitochondria [291], in addition to a Mfn2-dependent modulation of ER-mitochondria juxtaposition that relies on trichoplein/mitostatin (TpMs) [292]. Moreover, the multifunctional protein PACS-2 controls the apposition of rod-like mitochondria to the ER, influencing multiple organelle-specific functions, such as mitochondrial fusion-fission events, lipid metabolism and apoptosis [293]. Likewise, a molecular complex involved in ER-mitochondria contact and lipid exchange has been identified in yeast and named “ERMES”, although its orthologues in mammals are still unknown [294]. Interestingly, the FAD linked protein PS2 [295] has been demonstrated to modulate the interaction between the two organelles (Fig. 2d, e) as well as their Ca2+ cross-talk, thus possibly contributing to the Ca2+ dysregulation that characterizes this disease [296].

The majority of these proteins have been found in the so-called MAMs, domains of close contacts through which ER communicates with mitochondria [139, 140]. These membrane domains are enriched in metabolic enzymes, such as the phosphatidylserine synthase 1 and the long-chain coenzyme-A ligase 4, as well as in channels, pumps and proteins involved in Ca2+ homeostasis (Fig. 1g), such as SERCAs and IP3Rs (IP3R3, in particular), molecular chaperones like CRT, calnexin and the recently discovered sigma-1 receptor (see [297] for a comprehensive review), suggesting that these domains have a pivotal role not only in metabolic linkage, but also in Ca2+ shuttling between ER and mitochondria [246, 265, 298].

As far as mitochondrial Ca2+ efflux is concerned, several mechanisms are known to be present. A Na+/Ca2+ antiporter extrudes 1 Ca2+ from mitochondria, exchanging it with 3(4) Na+, similarly to the NCX on the PM; the mitochondrial exchanger has been recently identified as NCLX, a protein located in cristae whose overexpression/downregulation increases/decreases mitochondrial Na+-dependent Ca2+ efflux [299]. Another extrusion mechanism, Na+-independent, exchanges Ca2+ with 2(3) H+ [300] (see also [280] for a recent review).

Cytosolic Ca2+ signals are extremely important in tuning mitochondrial activity, but they are themselves finely shaped by mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering activity that contributes in modulating their amplitude, duration and propagation. ATP supplied by mitochondria is required by all the mechanisms involved in terminating cytosolic Ca2+ signals, i.e., ATPases located at the PM (and exchangers whose activity depends on ion gradients created by other ATPases, like NCX, which relies on Na+ gradient maintained by NA+/K+ ATPases) and on intracellular stores, like SERCA and SPCA pumps. Thus, mitochondria are ultimately critical for the termination of any Ca2+ signals. Apart from this, they can contribute to finely shaping any Ca2+ signal inside the cells. The effects of mitochondria Ca2+ buffering on single Ca2+ signaling events can vary from the type of event and the cell under investigation [301]. However, considering bulk cytosolic Ca2+ responses, it is noteworthy that mitochondria can contribute to decreasing acute cystolic Ca2+ rises by buffering Ca2+ and can also prolong them by releasing, in a second step, the accumulated Ca2+ [302]; alternatively, this secondary Ca2+ release by mitochondria can also contribute to fast Ca2+ oscillations linked to Ca2+ release from the ER: the slightly increased [Ca2+]i provided by mitochondria would facilitate the following Ca2+ release events by increasing the open probability of channels on ER membrane [303] and also favor the refilling of proximal ER regions [304]. Moreover, it has been reported that, in polarized cells, mitochondria can act as a buffering barrier confining Ca2+ signals in specific regions of the cell [305].

Altogether these results highlight the intimate liaison among mitochondria, ER and Ca2+, and underline the key role of mitochondria in cellular Ca2+ homeostasis.

Acidic compartments

Beside the ER and the GA, which represent the main intracellular Ca2+ deposits, mammalian cells store Ca2+ also in a variety of acidic organelles, such as endosomes, lysosomes and secretory granules. In fact, the Golgi complex itself should be considered an acidic Ca2+ store, as its luminal pH has been estimated to range between 6.8 and 5.9 [174, 306, 307]. Unlike the GA, however, the other acidic organelles mainly show Ca2+ uptake and release mechanisms molecularly distinct from those of the ER, and therefore they represent unique intracellular Ca2+ pools linked to the activation of specific cell functions (Fig. 1f).

The mechanism of Ca2+ uptake and release by acidic organelles is still poorly understood and probably different in the heterogeneous group of organelles lumped together under the name of “acidic Ca2+ stores.” Below, we briefly summarize the different and often contradictory proposals published in the last years.

As far as Ca2+ uptake is concerned, evidence has been provided suggesting that acidic Ca2+ stores take up Ca2+ from the cytoplasm using a SERCA-type Ca2+ ATPase (described in acidic stores of human platelets [308]; large dense core granules in PC12 cells [309]; insulin storage granules in mouse pancreatic beta cells [310] and bovine adrenal chromaffin granules [311]) and an SPCA-based system, present in dense core secretory vesicles of neuroendocrine cells [177]. Some acidic organelles, such as lysosomes from different cell types [312, 313], show an additional ATP-dependent Ca2+ uptake mechanism, whose molecular nature has not yet been identified. However, the large proton concentration gradient across their membranes (maintained by a vacuolar proton ATPase, V-ATPase) appears essential for their Ca2+ uptake: accordingly, the existence of a Ca2+/H+ exchanger has been proposed. Such activity has been measured in isolated melanosomes from retinal pigment epithelial cells [314] and large dense core granules in PC12 cells [309]. In the latter cell type, however, as well as in many other cells, our group failed to measure a ΔH+-dependent intracellular Ca2+ accumulation (see for example [315]), raising doubts on the functional relevance of this type of Ca2+ uptake mechanism. Noteworthy, Ca2+/H+ exchangers have been found thus far only in protist, yeast and plant vacuoles (see [316] for a recent review); a possible indirect pathway could involve the concerted activity of Na+/H+ and Na+/Ca2+ exchangers, reported to be present in these organelles [309, 317].

Regarding the Ca2+ content within these organelles, a distinction has to be made between the different structures. The free Ca2+ concentration within newly formed endosomes, for example, is thought to be that of the extracellular medium (~1 mM), although rapidly after their acidification (or because of that) it falls to around 3 μM [318]. The luminal Ca2+ seems however necessary for late endosome-lysosome heterotypic fusion [319], and it was more recently reported to be higher (40 μM) in enlarged endosome-like structures formed in stimulated pancreatic acinar cells [320].

Secretory granules of many cell types and the related synaptic vesicles of neurons show a remarkably high total Ca2+ content (tens of mM) (see, for example, [321]), thus representing a major Ca2+ store in the cell. Their free Ca2+ luminal concentration, however, has been estimated, by rather indirect means, to be considerably lower, i.e., 10–40 μM in mast cell and chromaffin cell granules [322, 323] and, by direct measuring with a selectively targeted Aeq, 100–200 μM in insulin granules [177]. This markedly different concentration is due to the existence of a very strong Ca2+ buffer within these organelles: Ca2+-binding proteins such as chromogranins and secretogranins are known to be highly concentrated in the lumen of these granules [324]. Moreover, these organelles in some cells are able to take up Ca2+ and release it upon specific cell stimulation (see below), and thus might function as Ca2+ sinks or sources particularly important in the generation of local Ca2+ signals involved in secretion [177, 309, 325–328].

Finally, lysosomes and lysosome-related organelles, such as melanosomes, lytic granules in lymphocytes, major histocompatibility complex class II compartments in antigen-presenting cells, platelet dense granules, basophilic granules and neutrophil azurophil granules [329], can be very rich in Ca2+. Although a direct lysosomal luminal Ca2+ measurement is difficult, due to their very acidic and proteolytic environment, recent data, obtained with a specifically localized fluorescent indicator, report a very high free Ca2+ concentration (~500 μM) in their lumen [330]. As far as lysosome-related organelles are concerned, an example of Ca2+ store is made by platelet-dense granules that have a pH of ~5.4 and a total Ca2+ concentration of 2.2 M [331]. These latter organelles are particularly interesting acidic stores because they resemble acidocalcisomes, organelles present in both prokaryotes and in eukaryotes, such as Trypanosoma and Plasmodia, which contain high Ca2+ concentrations at mM levels and serve several functions, including storage of cations and phosphorus, polyphosphate metabolism, maintenance of intracellular pH homeostasis and osmoregulation [332].

As to the Ca2+ release mechanism from acidic stores, all the classical Ca2+ releasing messengers have been reported to deplete these organelles: IP3 from secretory vesicles of different cells [321]; cADPR from zymogen granules or a closely associated acidic organelle of exocrine pancreatic acinar cells [326], and dense core vesicles of a clonal pancreatic beta cell line [177]. Additionally, caffeine (a pharmacological activator of RyRs) was shown to mediate Ca2+ release from isolated melanosomes [314]. But the most potent Ca2+-mobilization messenger of acidic stores is NAADP [91]. The first demonstration of its action was made in sea urchin eggs [333], where the newly identified (by high-resolution mass measurements) NAADP was able to mediate a Ca2+ release with a kinetics significantly faster than the cADPR-sensitive one, making it the most effective Ca2+ release activator in sea urchin eggs. Moreover, the putative NAADP receptor was postulated to be different from those for IP3 and cADPR because specific blockers of the latter had no effect on the NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ release [333]. Afterwards, it was demonstrated that a NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ release was present also in different cell types [334] and was blocked by the drug glycyl-l-phenylalanine-naphthylamide (GPN), a lysosome-disrupting cathepsin-C substrate, and also by bafilomycin-A1, an inhibitor of V-type ATPases [335]. The latter result led to the suggestion that, in general, all the acidic organelles could be NAADP-sensitive. Indeed, similarly to IP3 and cADPR, which generally mobilize ER and/or Golgi Ca2+ stores (see above), NAADP has been shown to mobilize Ca2+ also from endosomes [336], lysosomes in pancreatic acinar and beta cells [337], and secretory granules [325]. Although the physiological route of NAADP synthesis is not clear [338, 339], it can be synthesised by the same enzyme that is responsible for the synthesis of cADPR (see above) from NADP and nicotinic acid. Also the intracellular pathway that links extracellular stimulation to messenger synthesis remains uncertain, mainly due to the fact that the best studied ADP-ribosyl cyclases are largely ectocellular, creating the so-called ‘topological paradox’ discussed in [340]. As to the molecular identity of the channel(s) responsible for the NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release from acidic stores, the issue is still subject to debate (see [341] for a recent review). A non-selective cation channel, the transient receptor potential mucolipin 1 (TRP-ML1), that is present in lysosomes, has first emerged as a potential candidate for the NAADP receptor [342]. Although other authors support the view that NAADP may induce Ca2+ release, in some cell types, by directly activating RyRs [343, 344], recent clear data indicate the existence of a new family of channels that mediate Ca2+ release from acidic organelles upon activation by NAADP, the so-called two pore channels (TPC) (reviewed in [345]). TPCs are widely distributed in mammalian cells [346–348] in three subtypes, TPC1 to -3, with TPC2 being targeted mainly to lysosomes and TPC1/TPC3 to endosomes. Significantly, NAADP-induced Ca2+ release via TPC2 appears to serve as a trigger for a sequential activation of IP3Rs and/or RyRs from the ER to evoke a propagating Ca2+ wave. On the other hand, Ca2+ release from endosomal TPC1 leads to a restricted Ca2+ signal, not amplified by CICR from the ER [5]. Thus, Ca2+ released from these stores can either produce local or propagating global signals, being able, in the latter case, to couple, via CICR, to the ER/Golgi Ca2+ store.

In conclusion, many aspects of the Ca2+ release and uptake mechanisms in acidic Ca2+ stores remain to be clarified, and we predict major news on this topic in the years ahead.

Peroxisomes

Peroxisomes are single membrane organelles with a high matrix protein concentration that includes at least 50 different enzymes involved in several pathways; among these, the best known are enzymes involved in fatty acid β-oxidation, scavenging of hydrogen peroxide, functions that in animal cells are partially shared by mitochondria, and the synthesis of etherphospholipids [349, 350]. In particular, peroxisomes are endowed with several enzymes capable of disposing of oxygen peroxide (generated in large amount by the oxidative reactions occurring in the organelles), e.g., catalase, glutathione peroxidase and peroxiredoxin V (for an exhaustive review on peroxisomal biochemistry see [351]).

These organelles are numerous and dispersed within the entire cytosol, and they can rapidly adapt to cellular demand by increasing their size or numbers; the increase in their number is mainly triggered by lipids, through the activation of a ligand-dependent transcription factor (peroxisome proliferator activated receptor, PPAR), and mainly mediated by a fission process similar to that described for mitochondria [349]. In addition, some evidence suggests that ER can contribute to the generation of peroxisomes [352]; however, other authors proposed that this process would represent just a way to supply dividing peroxisomes with membrane constituents [353] (reviewed also in [354]). Interestingly, a population of vesicles derived from mitochondria has been shown to fuse with peroxisomes [355], and indeed some similarities in fission machinery [356] and metabolic functions [350] suggest a correlation between the two organelles closer than expected [357].

Apart from their metabolic functions, peroxisomes have emerged as organelles important in determining cell fate, contributing to regulating cell differentiation as well as embryo development and morphogenesis [358]. The lipids synthesized by peroxisomes can indeed be targeted to the nucleus by specific binding proteins, and there activate lipid-dependent transcription factors (including PPARs) that regulate the expression of several genes involved in differentiation and development [359]. The key role of peroxisomes in cell life and development is highlighted by the existence of several (about 20) human disorders linked to defects in their biogenesis or to deficiencies of one of their enzymes; this second kind of disease causes primarily specific biochemical abnormalities, but the ultimate symptoms mimic those of peroxisome biogenesis diseases; among these, the most known is Zellweger syndrome, characterized by liver disease, delay in neurodevelopment, weakness and perceptive deafness, which often lead to death before the age of 1 year [360].

Contrarily to what would be expected, peroxisomes are quite impermeable organelles and use several carriers to take up different metabolites [351]. Regarding peroxisomal Ca2+ handling, an issue potentially very interesting to understand possible regulatory signals for their metabolic activity, the information available is scarce and contradictory, suggesting that these organelles may have different behaviors due to their heterogeneity, possibly linked to a different biogenesis.

A first attempt to characterize peroxisomal Ca2+ handling was made in 2006 in purified peroxisomes [361]: according to these authors, the organelles contain Ca2+ and show a vanadate-sensitive Ca2+ ATPase in their membranes. This study, however, was not performed on living cells, and the peroxisomal fraction could be contaminated by other membranes.

In the following years, two groups generated two different Ca2+ probes targeted specifically to peroxisomes, thus allowing direct Ca2+ measurement within the organelles in intact cells. By employing two new FRET-based Cameleon probes (with different affinity for Ca2+; [178]; Fig. 2f), the first group [362] carried out single cell analysis of Ca2+ dynamics in peroxisomal lumen, showing that the organelles have a [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]perox) similar to the resting cytosolic one and that only large cytosolic Ca2+ increases can be mirrored by concomitant peroxisomal Ca2+ increases. These latter are mediated neither by a Ca2+ ATPase nor by a chemical gradient of H+ or Na+ and show slow kinetics, suggesting that the peroxisomal membrane probably acts as a low pass filter, enabling these organelles to be reached only by Ca2+ signals with an amplitude and/or a duration large enough to overcome this barrier (Fig. 1f).