Abstract

The stoma is a micro valve found on aerial plant organs that promotes gas exchange between the atmosphere and the plant body. Each stoma is formed by a strict cell lineage during the early stages of leaf development. Molecular genetics research using the model plant Arabidopsis has revealed the genes involved in stomatal differentiation. Cysteine-rich secretory peptides of the EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR-LIKE (EPFL) family play crucial roles as extracellular signaling factors. Stomatal development is orchestrated by the positive factor STOMAGEN/EPFL9 and the negative factors EPF1, EPF2, and CHALLAH/EPFL6 in combination with multiple receptors. EPF1 and EPF2 are produced in the stomatal lineage cells of the epidermis, whereas STOMAGEN and CHALLAH are derived from the inner tissues. These findings highlight the complex cell-to-cell and intertissue communications that regulate stomatal development. To optimize gas exchange, particularly the balance between the uptake of carbon dioxide (CO2) and loss of water, plants control stomatal activity in response to environmental conditions. The CO2 level and light intensity influence stomatal density. Plants sense environmental cues in mature leaves and adjust the stomatal density of newly forming leaves, indicating the involvement of long-distance systemic signaling. This review summarizes recent research progress in the peptide signaling of stomatal development and discusses the evolutionary model of the signaling machinery.

Keywords: Cell differentiation, Environmental response, Plant development, Peptide signaling, Stomata

Introduction

The stoma, a micro valve found on aerial plant organs, is responsible for gas exchange. It takes in carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air and transpires moisture from the plant body. A stoma consists of a pair of guard cells, each having a lip-like shape and a pore between them. “Stoma” (plural: stomata) is derived from the Greek term meaning “mouth.” Although individual stomatal pores are extremely small, for example ~25 μm in Arabidopsis, stomatal gas exchange in the aggregate affects global water and carbon cycles [1]. Stomata allow CO2 uptake to provide a photosynthetic substrate necessary for plant growth. However, water from the plant body can be lost through the stomata. Therefore, the regulation of stomatal function is extremely important to plant survival. Plants use two types of stomatal regulation systems to adapt to environmental conditions. One is a rapid-response system, which involves the opening and closing of the stomata. Various internal and environmental factors, such as abscisic acid, Ca2+, CO2, and blue light, are involved in this mechanism [2, 3]. The other system is a longer-term response, which involves the regulation of the number or density of stomata [4, 5]. The number of stomata that develop on new budding leaves can be modulated in response to environmental signals, but the control of such stomatal development is not fully understood.

During the past 10 years, molecular genetics research using the model plant Arabidopsis has revealed the genes involved in stomatal development [6, 7] (Table 1). A series of studies has elucidated the presence of cell-to-cell communication that regulates stomatal differentiation [8]. It is believed that if stomata form adjacent to each other, they cannot function efficiently [9]. To differentiate stomata at appropriate densities and patterns, peptide signaling sorts cells into those that will become stomata and those that will become pavement cells. Once extracellular signaling is recognized by cell surface receptors, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade within the cell becomes activated, thereby regulating the transcription factors that promote stomatal development [10, 11]. In this review, we summarize recent research progress involving peptide signaling and environmental responses to stomatal development.

Table 1.

Extracellular signaling regulators of stomatal development in Arabidopsis

| Gene (symbol) | AGI code | Protein | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signaling peptides | ||||

| EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR 1 (EPF1) | At2g20875 | Secretory peptide | Negative | [26] |

| EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR 2 (EPF2) | At1g34245 | Secretory peptide | Negative | [27, 28] |

| CHALLAH (CHAL/EPFL6) | At2g30370 | Secretory peptide | Negative | [38] |

| STOMAGEN (STOMAGEN/EPFL9) | At4g12970 | Secretory peptide | Positive | [34–36] |

| Signaling receptors | ||||

| ERECTA (ER) | At2g26330 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase | Negative | [31] |

| ERECTA LIKE 1 (ERL1) | At5g62230 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase | Negative | [31] |

| ERECTA LIKE 2 (ERL2) | At5g07180 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase | Negative | [31] |

| TOO MANY MOUTHS (TMM) | At1g80080 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein | Negative | [29, 30] |

| Protease | ||||

| STOMATAL DENSITY AND DISTRIBUTION 1 (SDD1) | At1g04110 | Subtilisin-like protease | Negative | [32, 33] |

Stomatal development in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana

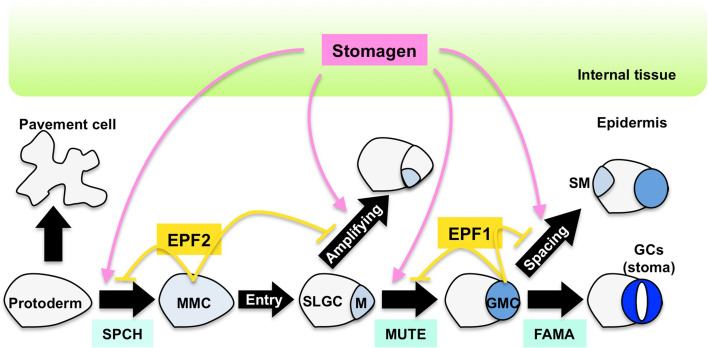

Each stoma is formed from a protodermal cell, which is an undifferentiated epidermal cell, through a strict cell lineage in the very early stages of leaf development [9, 12] (Fig. 1). First, the protodermal cell differentiates into a meristemoid mother cell (MMC), and then it undergoes asymmetric division to generate a small, triangular meristemoid and a larger sister cell. This asymmetric division is called an entry division because it is the first division necessary to enter the stomatal lineage. The meristemoid has properties similar to those of a stem cell, and it undergoes asymmetric division up to three times to generate daughter cells. These steps are collectively referred to as an amplifying division because they amplify stomatal lineage cells. The meristemoid then differentiates into a round-shaped guard mother cell (GMC). The GMC undergoes symmetric division to generate a pair of guard cells (GCs), which constitute a stoma. The sister cell of a meristemoid cell is a stomatal lineage ground cell (SLGC). The SLGC undergoes an asymmetric division called a spacing division to generate a satellite meristemoid, which does not contact a pre-existing stoma. For this reason, a stoma is not directly adjacent to other stomata. This is known as the “one cell spacing rule.” In the early stages of differentiation, almost all cells are stomatal lineage cells. As development progresses, it is believed that most cells fall out of the stomatal lineage and become pavement cells.

Fig. 1.

Stomatal development and cell-to-cell signaling in the Arabidopsis leaf. During leaf development, the protodermal cell differentiates into either a guard cell (GC) or a pavement cell. Three paralogous bHLH transcription factors, SPEECHLESS (SPCH), MUTE, and FAMA, regulate the progression of the stomatal lineage sequentially. SPCH regulates the differentiation of protodermal cells to meristemoid mother cells (MMCs). Subsequently, entry division begins to produce stomatal lineage ground cells (SLGCs) and a meristemoid (M), which is differentiated into the guard mother cell (GMC) by MUTE. FAMA regulates the symmetric division of GMC to produce GCs (i.e., a stoma). Stomatal development is regulated by cell-to-cell communication through signaling peptides including stomagen, EPF1, and EPF2. Stomagen, which is derived from internal tissues, positively regulates stomatal development at several steps as indicated. EPF2 is produced mainly in the MMC to inhibit the differentiation of protodermal cells into an MMC, whereas EPF1 is produced mainly in the GMC to inhibit the differentiation of the M into a GMC. EPF1 also regulates the direction of the spacing division to produce the satellite meristemoid (SM)

Progression of the cell lineage of stomata is regulated by two classes of basic Helix-loop-Helix (bHLH) transcription factors [13, 14]. One class contains three paralogous proteins, SPEECHLESS (SPCH), MUTE, and FAMA, each of which regulates a distinct step of stomatal development (Fig. 1). SPCH functions in the first step of stomatal development by regulating the differentiation of protodermal cells [15]. The epidermis of the spch mutant has no stoma but is occupied by pavement cells. Similarly, the mute mutant has no stoma but contains aborted meristemoids that are formed by excessive amplifying divisions [16]. Therefore, MUTE limits the frequency of asymmetric division and promotes the differentiation of meristemoids to GMCs. The third factor, FAMA, works in the final step of stomatal formation [17]. In the fama mutant, stacks of immature GCs exist that are formed by excessive division of the GMC, instead of forming stomata. The roles of FAMA involve carrying out one symmetric division of the GMC and establishing GC identity. The level of these bHLH proteins is strictly regulated at a distinct step of the stomatal lineage, allowing them to perform their functions. The second class of bHLH proteins contains SCREAM/ICE1 (SCRM) and SCRM2. A gain-of-function allele of the SCRM gene, scrm-D, results in an epidermis that is full of stomata [18]. SCRM and SCRM2 genes are expressed throughout the stomatal lineage, and their gene products influence stomatal development by forming heterodimers with SPCH, MUTE, or FAMA.

An MAPK cascade is known to be involved in the signal transduction of stomatal development. A signaling module consisting of YODA (YDA, a MAPK kinase kinase), MKK4/5/7/9 (MAPK kinases), and MPK3/6 (MAPKs) negatively regulates both MMC-to-meristemoid and meristemoid-to-GMC transitions during stomatal development [10, 19, 20]. The phosphorylation status of SPCH in MMC is regulated by the MAPK cascade [11]. In contrast, a module consisting of YDA and MKK7/9 positively regulates the GMC-to-GC transition [20]. The substrates of the MAPK cascades in meristemoids and GMCs are not known. MAPK cascades have been shown to mediate abiotic and biotic stress responses in plants [21, 22]. It is possible that the MAPK cascade integrates the developmental and environmental signals during stomatal development.

Negative feedback of stomatal development within the epidermis

In recent years, it was discovered that peptide hormones play an important role in plant morphogenesis [23, 24], and this has become an active area of plant research. The cell-to-cell signaling factors that function during stomatal development are cysteine-rich secretory peptides that belong to the EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR-LIKE (EPFL) family [8, 25] (Fig. 2). EPF1 [26] and EPF2 [27, 28] have been identified as negative factors of stomatal development (Fig. 1). Stomatal densities are elevated in mutants that have defects in these peptides. Although the amino acid sequences of EPF1 and EPF2 are similar, these peptides exhibit distinct functions in stomatal development: EPF2 regulates the differentiation of the protodermal cell to the MMC, whereas EPF1 regulates the direction of the spacing division that generates satellite meristemoids. Consistent with their functions, EPF2 and EPF1 genes have their own temporal and spatial expression patterns in the stomatal lineage: EPF2 gene is expressed in MMCs and early meristemoids, whereas EPF1 gene is expressed in GMCs and young GCs. Differentiation steps to generate MMCs and GMCs are suppressed by overexpressing EPF1 and EPF2, respectively [27]. It is likely that the secreted peptides repress the differentiation of adjacent cells by negative feedback.

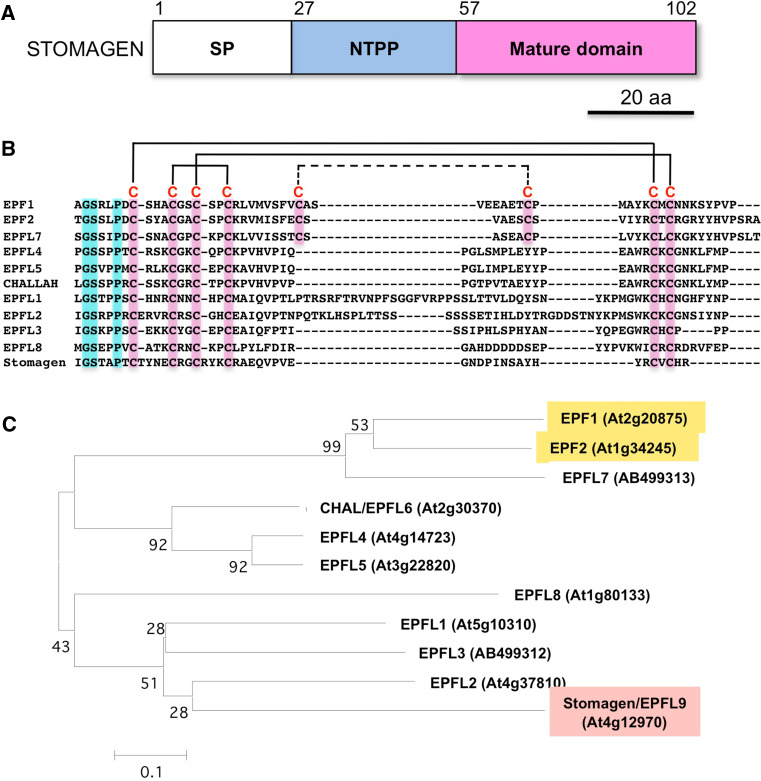

Fig. 2.

The EPFL family of signaling peptides in Arabidopsis. a Schematic illustration of the domain structure of STOMAGEN/EPFL9, which is composed of the signal peptide (SP), the N-terminal propeptide (NTPP), and the mature domain. Amino acid positions are indicated above the structure. b Amino acid sequence alignment of putative mature domains of the EPFL family. Identical amino acid residues are shaded in blue. Conserved cysteine residues (C) are shaded in red. Three disulfide bridges of stomagen are indicated by solid lines. The putative pairs of additional cysteine residues are linked by a dotted line. Sequences are aligned by Clustal W. c Phylogenetic tree of the EPFL family. Bootstrap values for 1,000 replications are indicated on each node. The phylogenetic tree is constructed by a neighbor-joining method using the alignment in b with MEGA version 4 software [49]

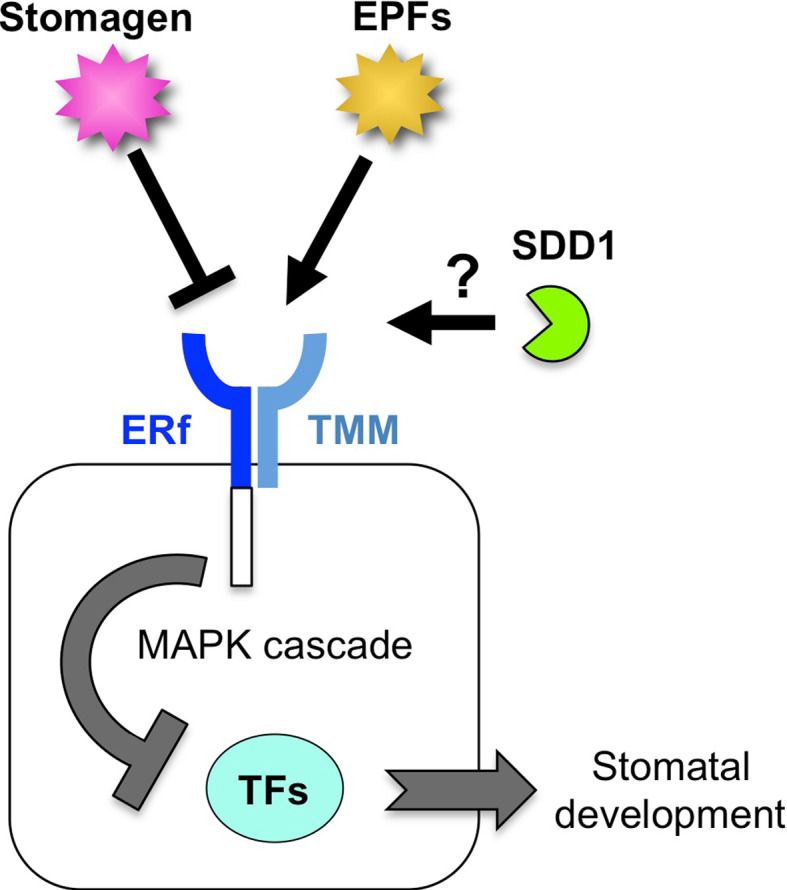

Putative receptors for the signaling peptides are the receptor-like membrane protein TOO MANY MOUTHS (TMM) [29, 30] and the ERECTA family (ERf) of receptor-like kinases [31]. These receptors contain leucine-rich-repeat motifs in their extracellular domains. The ERf is composed of three members, ERECTA, ERL1, and ERL2, each of which has distinct but overlapping functions in stomatal development. TMM and ERf are thought to associate with each other in the plasma membrane. Because TMM lacks the cytosolic kinase domain, extracellular peptide signaling is transmitted into the cell by the kinase domain of the ERf. TMM may support ERf activity. The number of stomata on the leaf epidermis is increased in mutants defective in TMM and ERf receptors, indicating that they are also negative regulators.

A subtilisin-like protease, STOMATAL DENSITY AND DISTRIBUTION 1 (SDD1), is also known as a negative regulator of stomatal development. The sdd1 mutant increases stomatal density and forms stomatal clusters [32, 33]. SDD1 is believed to proteolytically process certain negative signaling factors, such as EPF1 and EPF2. However, overexpression of each gene of EPF1 and EPF2 in the sdd1 background reduced stomatal densities as in wild-type plants, suggesting that function of these signaling peptides is independent of SDD1 [26, 27]. It is possible that negative signaling receptors (TMM and ERf) are modulated by SDD1. Another possibility is that SDD1 exerts a negative effect on stomatal development by degrading the positive regulator, stomagen, as shown below.

Peptide signaling from the inside to regulate stomatal development in the epidermis

In contrast to the factors above, STOMAGEN/EPFL9 has recently been identified as a positive signaling factor for stomatal development [34–36]. The mature form of STOMAGEN, defined as stomagen, is the C-terminal 45-amino-acid peptide with three intramolecular disulfide bonds (Fig. 2). In spite of their opposing functions, STOMAGEN and EPFs belong to the same peptide family and have the same conserved cysteine residues. Overexpression of the STOMAGEN gene increases the number of stomata, and suppression of the STOMAGEN gene decreases the number of stomata. Treatment of Arabidopsis seedlings with chemically synthesized stomagen can also induce the formation of stomata. It has been revealed that the positive signaling factor STOMAGEN also requires the negative receptor TMM [35, 36]. This observation supports an “agonist–antagonist” hypothesis in which the positive peptide, STOMAGEN, and negative peptides, EPFs, act antagonistically on the same receptor(s) during the process of stomatal development (Fig. 3). It has been shown that, during angiogenesis in animals, the two highly homologous molecules angiopoietin (ANG) 1 and ANG 2 bind antagonistically to the receptor Tie2, causing opposite actions [37]. Signals acting antagonistically on the same receptor have not been found in plants. For this reason, the control of stomatal development with STOMAGEN and EPFs may constitute a new regulatory system model in plants.

Fig. 3.

A model of the peptide signaling system during stomatal development. Stomatal development is promoted by transcription factors (TFs) in the absence of peptide signaling and MAPK cascade. ERf and TMM form the negative receptor complex at the plasma membrane. The negative signaling peptide EPFs and the positive signaling peptide stomagen interact competitively with the receptor complex. The kinase domain of ERf transmits negative signals to the MAPK cascade, which represses the function of TFs. The molecular function of the negative factor SDD1 is unknown

The STOMAGEN gene is expressed in the internal tissue of plants but not in the epidermis where stomata are formed [35, 36]. This means that the internal tissues regulate stomatal development in the epidermis through stomagen. What is the physiological advantage of this intertissue regulation? It has been shown that plants alter stomatal density to adapt to environmental changes. Although negative feedback regulation can stabilize a certain stomatal density in the epidermis as described above, it cannot modulate stomatal density in response to environmental changes. An intertissue regulation can modulate it independently of epidermal cell conditions. The intertissue regulation by stomagen might play a role in adjusting stomatal density in response to environmental changes.

Recently, a member of the EPF peptide family CHALLAH (CHAL/EPFL6) was also found to be produced in internal tissues [38]. Overexpression of CHAL has a negative effect on stomatal development that is similar to the effects of EPF1 and EPF2. CHAL function depends on the receptor-like kinase (ERf), but not on the receptor-like membrane protein (TMM). CHAL gene is expressed mainly in the hypocotyl and stem but not in the leaf or cotyledon, suggesting that CHAL is involved in the organ-specific regulation of stomatal development.

Environmental response of stomatal development

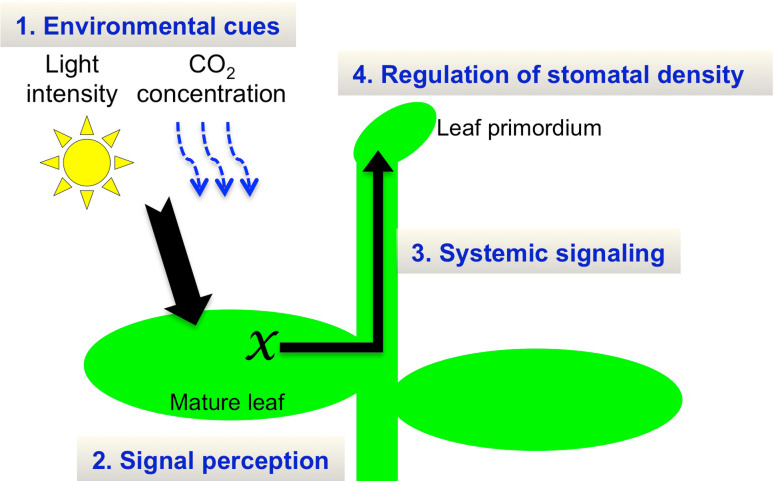

To optimize gas exchange, particularly the balance between the uptake of CO2 and loss of water, plants regulate stomatal activity in response to environmental changes. Two kinds of stomatal regulation are recognized: stomatal movement (opening and closing) and stomatal density. The mechanism of stomatal movement has been well studied [2, 3]. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying stomatal density in response to environmental conditions are poorly understood. Plants can modulate the number of stomata on newly developing leaves in response to environmental changes [4, 5] (Fig. 4). It has been reported that stomatal density has decreased in various types of plants as CO2 concentration in the air has increased since the Industrial Revolution [39]. In fact, the stomatal densities of many plant species, including Arabidopsis, have decreased in response to the increased CO2 concentration [40]. Another environmental factor that influences stomatal development is light. Stomatal density is increased by strong light irradiation [41]. Recently, it was revealed that red light is responsible for an increase in stomatal density. Moreover, genetic analysis has indicated that the red-light photoreceptor phytochrome B and its downstream transcription factor PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR 4 (PIF4) are involved in signal transduction [42].

Fig. 4.

Systemic signaling for stomatal development in response to environmental conditions. The mature leaf perceives environmental cues, such as light intensity or CO2 level, to generate an unknown systemic signal (X). The systemic signal migrates to the leaf primordium, which alters stomatal density on the developing leaf

An Arabidopsis mutant has been identified that causes defects in the response of stomatal density to CO2. The high carbon dioxide (hic) mutant exhibits increased stomatal density when grown in elevated levels of CO2 [43]. The HIC gene encodes the 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase involved in the elongation process of very long chain fatty acids in wax biosynthesis. Because the HIC gene is expressed specifically in stomata, it is suggested that a failure of density regulation is caused by the alteration of the stomatal permeability of a diffusible signal that regulates stomatal development. Where do plants sense CO2 for stomatal development? One possible site that perceives CO2 is the stoma, although mesophyll cell is a main site that assimilates CO2 for photosynthesis. A double-mutant plant in the β-carbonic anhydrases βCA1 and βCA4 has impaired CO2-regulated stomatal movement and has increased stomatal density [44]. Specific expression of the carbonic anhydrase gene in the stomata results in the complement of mutant phenotypes, suggesting that CO2 sensing for stomatal development occurs in the stomata. Systemic signaling has been suggested to be involved in the regulation of stomatal density; plants sense CO2 concentration or light intensity in mature leaves and regulate stomatal density on the newly forming leaves [45–47] (Fig. 4). Thus it is possible that plants sense CO2 at stomata of mature leaves to regulate the stomatal densities of newly forming leaves. However, the factor(s) required for systemic signaling are not fully resolved.

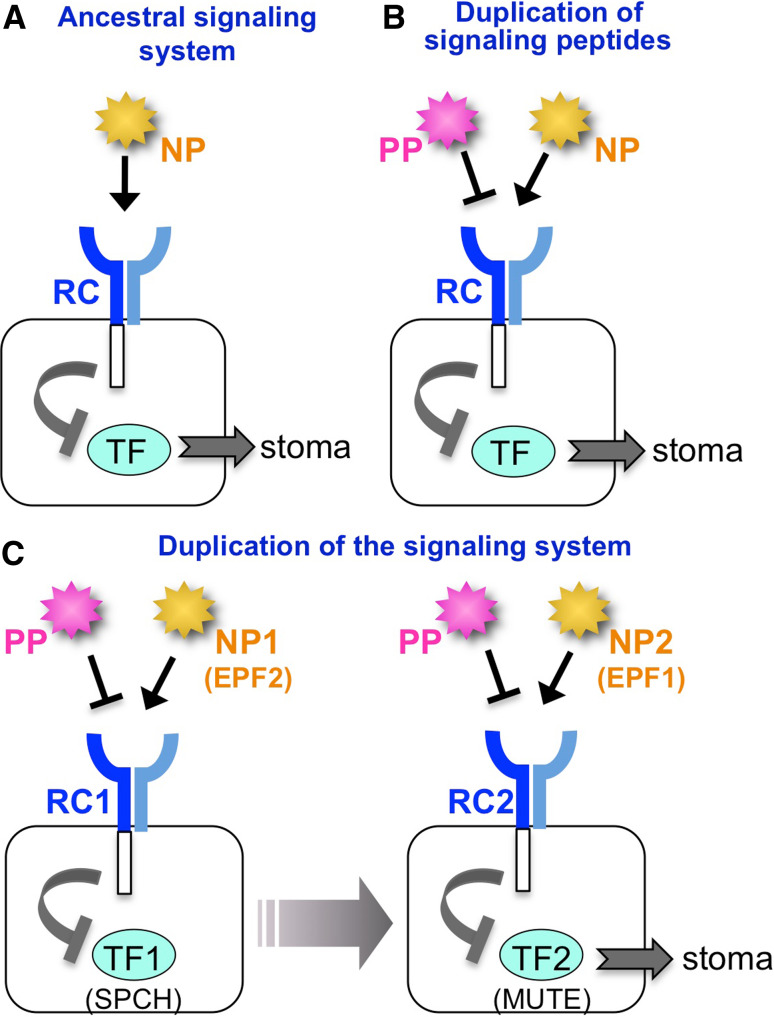

Evolutionary model of the signaling machinery and future perspectives

A rigorous cell lineage of stomatal development is comprised of several steps, each of which is regulated by cell-to-cell communication. As described above, understanding of the genes involved in stomatal development has increased. Many homologous genes, including signaling peptides, receptors, and transcription factors, are involved in each step, and each gene has a unique function. Based on this fact, an evolutionary model of the signaling machinery can be drawn. First, when a plant initially gains a stoma, stomatal development is comprised of a single step with negative signaling (Fig. 5a). For more sophisticated regulation, plants utilize a positive peptide, such as stomagen (Fig. 5b). It is assumed that STOMAGEN evolved from the negative peptide factors through gene duplication and then alteration of function. Although orthologs of STOMAGEN are present in a fern (Selaginella moellendorffii), none have been found in mosses [36].

Fig. 5.

An evolutionary model of the signaling machinery of stomatal development. a A possible ancestral signaling system in stomatal development. Stomatal development is promoted by the transcription factor (TF). The negative signaling peptide (NP) is perceived by the cell-surface receptor complex (RC), which represses the function of the TF. b Duplication of the signaling peptide. The positive signaling peptide (PP) may be generated by gene duplication of NP and subsequent conversion of negative activity to positive activity. The PP may bind competitively to the RC, but it loses signal transmission activity. c Duplication of the signaling system resulting in multiple steps of stomatal development. Each of the regulatory factors, NP, RC, and TF, is duplicated and subsequently acquires a distinct function. Stomagen is the only known PP so far

The evolutionary transition of plants from aquatic to terrestrial environments presented a number of challenges. One adaption to terrestrial conditions was gaining the ability to adjust stomatal density. It is possible that by duplication and modification of the simple lateral inhibition module with its positive and negative signals, plants evolved a stomatal developmental system with multiple regulatory modules able to more finely adjust the density and pattern of stomata in response to their environment (Fig. 5c). FAMA is considered the most basic transcription factor that establishes the identity of a guard cell. The moss Physcomitrella patens, one of the oldest terrestrial plants with stomata, has two FAMA-like genes, although neither SPCH gene nor MUTE gene was discovered in the moss genome [48]. Genome analyses of various plants would enable us to trace the changes in stomatal regulator genes and to determine how stomatal development has evolved. Further research is also required to elucidate how stomatal regulators are controlled during environmental responses to optimize gas exchange.

References

- 1.Berry JA, Beerling DJ, Franks PJ. Stomata: key players in the earth system, past and present. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2010;13:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimazaki K, Doi M, Assmann SM, Kinoshita T. Light regulation of stomatal movement. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2007;58:219–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim T-H, Böhmer M, Hu H, Nishimura N, Schroeder JI. Guard cell signal transduction network: advances in understanding abscisic acid, CO2, and Ca2+ signaling. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2010;61:561–591. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casson S, Gray JE. Influence of environmental factors on stomatal development. New Phytol. 2008;178:9–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casson SA, Hetherington AM. Environmental regulation of stomatal development. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2010;13:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nadeau JA. Stomatal development: new signals and fate determinants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2009;12:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serna L. Cell fate transitions during stomatal development. BioEssays. 2009;31:865–873. doi: 10.1002/bies.200800231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowe MH, Bergmann DC. Complex signals for simple cells: the expanding ranks of signals and receptors guiding stomatal development. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2010;13:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nadeau JA, Sack FD (2002) Stomatal development in Arabidopsis. In: Meyerowitz EM, Somerville CR (eds) The Arabidopsis book, American Society of Plant Biologists, Rockville [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Bergmann DC, Lukowitz W, Somerville CR. Stomatal development and pattern controlled by a MAPKK kinase. Science. 2004;304:1494–1497. doi: 10.1126/science.1096014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lampard GR, MacAlister CA, Bergmann DC. Arabidopsis stomatal initiation is controlled by MAPK-mediated regulation of the bHLH SPEECHLESS. Science. 2008;322:1113–1116. doi: 10.1126/science.1162263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergmann DC, Sack FD. Stomatal development. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2007;58:163–181. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.104023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pillitteri LJ, Torii KU. Breaking the silence: three bHLH proteins direct cell-fate decisions during stomatal development. BioEssays. 2007;29:861–870. doi: 10.1002/bies.20625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serna L. Emerging parallels between stomatal and muscle cell lineages. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:1625–1631. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.133090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacAlister CA, Ohashi-Ito K, Bergmann DC. Transcription factor control of asymmetric cell divisions that establish the stomatal lineage. Nature. 2007;445:537–540. doi: 10.1038/nature05491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pillitteri LJ, Sloan DB, Bogenschutz NL, Torii KU. Termination of asymmetric cell division and differentiation of stomata. Nature. 2007;445:501–505. doi: 10.1038/nature05467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohashi-Ito K, Bergmann DC. Arabidopsis FAMA controls the final proliferation/differentiation switch during stomatal development. Plant Cell. 2006;18:2493–2505. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.046136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanaoka MM, Pillitteri LJ, Fujii H, Yoshida Y, Bogenschutz NL, Takabayashi J, Zhu J-K, Torii KU. SCREAM/ICE1 and SCREAM2 specify three cell-state transitional steps leading to Arabidopsis stomatal differentiation. Plant Cell. 2008;20:1775–1785. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.060848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H, Ngwenyama N, Liu Y, Walker JC, Zhang S. Stomatal development and patterning are regulated by environmentally responsive mitogen-activated protein kinases in Arabidopsis . Plant Cell. 2007;19:63–73. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lampard GR, Lukowitz W, Ellis BE, Bergmann DC. Novel and expanded roles for MAPK signaling in Arabidopsis stomatal cell fate revealed by cell type-specific manipulations. Plant Cell. 2009;21:3506–3517. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.070110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colcombet J, Hirt H. Arabidopsis MAPKs: a complex signalling network involved in multiple biological processes. Biochem J. 2008;413:217–226. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez MC, Petersen M, Mundy J. Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2010;61:621–649. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsubayashi Y, Sakagami Y. Peptide hormones in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:649–674. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butenko MA, Vie AK, Brembu T, Aalen RB, Bones AM. Plant peptides in signalling: looking for new partners. Trends Plant Sci. 2009;14:255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rychel AL, Peterson KM, Torii KU. Plant twitter: ligands under 140 amino acids enforcing stomatal patterning. J Plant Res. 2010;123:275–280. doi: 10.1007/s10265-010-0330-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hara K, Kajita R, Torii KU, Bergmann DC, Kakimoto T. The secretory peptide gene EPF1 enforces the stomatal one-cell-spacing rule. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1720–1725. doi: 10.1101/gad.1550707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hara K, Yokoo T, Kajita R, Onishi T, Yahata S, Peterson KM, Torii KU, Kakimoto T. Epidermal cell density is autoregulated via a secretory peptide, EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR 2 in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50:1019–1031. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunt L, Gray JE. The signaling peptide EPF2 controls asymmetric cell divisions during stomatal development. Curr Biol. 2009;19:864–869. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang M, Sack FD. The too many mouths and four lips mutations affect stomatal production in Arabidopsis . Plant Cell. 1995;7:2227–2239. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.12.2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nadeau JA, Sack FD. Control of stomatal distribution on the Arabidopsis leaf surface. Science. 2002;296:1697–1700. doi: 10.1126/science.1069596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shpak ED, McAbee JM, Pillitteri LJ, Torii KU. Stomatal patterning and differentiation by synergistic interactions of receptor kinases. Science. 2005;309:290–293. doi: 10.1126/science.1109710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berger D, Altmann T. A subtilisin-like serine protease involved in the regulation of stomatal density and distribution in Arabidopsis thaliana . Genes Dev. 2000;14:1119–1131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Von Groll U, Berger D, Altmann T. The subtilisin-like serine protease SDD1 mediates cell-to-cell signaling during Arabidopsis stomatal development. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1527–1539. doi: 10.1105/tpc.001016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunt L, Bailey KJ, Gray JE. The signalling peptide EPFL9 is a positive regulator of stomatal development. New Phytol. 2010;186:609–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kondo T, Kajita R, Miyazaki A, Hokoyama M, Nakamura-Miura T, Mizuno S, Masuda Y, Irie K, Tanaka Y, Takada S, Kakimoto T, Sakagami Y. Stomatal density is controlled by a mesophyll-derived signaling molecule. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51:1–8. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugano SS, Shimada T, Imai Y, Okawa K, Tamai A, Mori M, Hara-Nishimura I. Stomagen positively regulates stomatal density in Arabidopsis . Nature. 2010;463:241–244. doi: 10.1038/nature08682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Augustin HG, Koh GY, Thurston G, Alitalo K. Control of vascular morphogenesis and homeostasis through the angiopoietin-Tie system. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:165–177. doi: 10.1038/nrm2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abrash EB, Bergmann DC. Regional specification of stomatal production by the putative ligand CHALLAH. Development. 2010;137:447–455. doi: 10.1242/dev.040931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woodward FI. Stomatal numbers are sensitive to increases in CO2 from pre-industrial levels. Nature. 1987;327:617–618. doi: 10.1038/327617a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hetherington AM, Woodward FI. The role of stomata in sensing and driving environmental change. Nature. 2003;424:901–908. doi: 10.1038/nature01843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schoch P, Zinsou C, Sibi M. Dependence of the stomatal index on environmental factors during stomatal differentiation in leaves of Vigna sinensis L.: 1. Effect of light intensity. J Exp Bot. 1980;31:1211–1216. doi: 10.1093/jxb/31.5.1211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Casson SA, Franklin KA, Gray JE, Grierson CS, Whitelam GC, Hetherington AM. Phytochrome B and PIF4 regulate stomatal development in response to light quantity. Curr Biol. 2009;19:229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gray JE, Holroyd GH, van der Lee FM, Bahrami AR, Sijmons PC, Woodward FI, Schuch W, Hetherington AM. The HIC signalling pathway links CO2 perception to stomatal development. Nature. 2000;408:713–716. doi: 10.1038/35042663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu H, Boisson-Dernier A, Israelsson-Nordström M, Böhmer M, Xue S, Ries A, Godoski J, Kuhn JM, Schroeder JI. Carbonic anhydrases are upstream regulators of CO2-controlled stomatal movements in guard cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:87–93. doi: 10.1038/ncb2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lake JA, Quick WP, Beerling DJ, Woodward FI. Plant development. Signals from mature to new leaves. Nature. 2001;411:154. doi: 10.1038/35075660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomas P, Woodward F, Quick W. Systemic irradiance signalling in tobacco. New Phytol. 2004;161:193–198. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00954.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coupe SA, Palmer BG, Lake JA, Overy SA, Oxborough K, Woodward FI, Gray JE, Quick WP. Systemic signalling of environmental cues in Arabidopsis leaves. J Exp Bot. 2006;57:329–341. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peterson KM, Rychel AL, Torii KU. Out of the mouths of plants: the molecular basis of the evolution and diversity of stomatal development. Plant Cell. 2010;22:296–306. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.072777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]