Abstract

Acoustic biosensors offer the possibility to analyse cell attachment and spreading. This is due to the offered speed of detection, the real-time non-invasive approach and their high sensitivity not only to mass coupling, but also to viscoelastic changes occurring close to the sensor surface. Quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) and surface acoustic wave (Love-wave) systems have been used to monitor the adhesion of animal cells to various surfaces and record the behaviour of cell layers under various conditions. The sensors detect cells mostly via their sensitivity in viscoelasticity and mechanical properties. Particularly, the QCM sensor detects cytoskeletal rearrangements caused by specific drugs affecting either actin microfilaments or microtubules. The Love-wave sensor directly measures cell/substrate bonds via acoustic damping and provides 2D kinetic and affinity parameters. Other studies have applied the QCM sensor as a diagnostic tool for leukaemia and, potentially, for chemotherapeutic agents. Acoustic sensors have also been used in the evaluation of the cytocompatibility of artificial surfaces and, in general, they have the potential to become powerful tools for even more diverse cellular analysis.

Keywords: Quartz crystal microbalance, Surface acoustic wave, Love wave, Cell adhesion, Cell/substrate interactions, Cytoskeleton, Two-dimensional affinity

Introduction

Under in vivo conditions, cells are in constant communication with their environment via molecules anchored to or embedded in the cell membrane. These membrane-bound receptors have evolved for cell attachment and cell-cell intercommunication, and play a pivotal role in numerous physiological and developmental conditions, such as tissue formation [1], leukocyte adhesion and rolling [2–5], and cell-mediated immune reactions [6–8]. In response to binding of specific ligands, cell surface receptors can mediate signal transduction to the cell interior and regulate phenomena such as cytoskeleton rearrangements or gene expression. Generally, cells interact with surfaces, either in vivo or in vitro, only via molecules of the cell membrane. Membrane proteins, the major class of which is called integrins, specifically interact with extracellular adhesive proteins. There are also non-specific interactions, e.g., based on electrostatic interactions between ionic or polar groups at the cell surface and the substrate. The adhesion of cells to surfaces is a requirement for their survival. Also, the interaction of cells with artificial surfaces is of significant importance to both basic and applied biomedical research, e.g., in the development and modification of biomaterials for implants. Therefore, assays capable of monitoring the establishment and dynamics of cell-substrate contacts would be extremely useful in many areas of interest.

In order to better understand the binding mechanisms between membrane molecules and their ligands, the interactions should be probed in conditions as close as possible to in vivo conditions. Moreover, these interactions are membrane-associated events that are difficult to study with techniques that do not probe the cell membrane directly. Also, from a mechanical point of view, adherent cells represent a multilayer system, with complex viscoelastic properties in each layer and elaborate mechanical interactions between them. Relatively few methods can be employed in the study of these events. Such cell-based assays can monitor the activities and health of living cells and extract information that would be lost using the traditional biochemical techniques. Most cell-based assays measure a specific cellular event, such as reporter gene expression, fluorescent target translocation or second messenger generation, and in the process one can extract information about the mode of action, signaling pathway activation and phenotypic response of cells mediated by external stimuli [9, 10]. However, the above cell-based techniques require manipulations that could compromise cell physiology. Thus, it is important to develop novel assays that would provide non-invasive and real-time monitoring of cellular processes with high sensitivity. Piezoelectric techniques offer a unique possibility to study such complex phenomena. In this review, we are going to briefly present the acoustic systems that are employed in studies with animal cells, report their applications in the understanding of cellular physiology so far and discuss their potential for the future.

Principles of acoustic sensing

Acoustic biosensors have the potential to study cell-substrate binding events because they are sensitive not only to mass coupling, but also to viscoelastic changes occurring close to the sensor surface [11]. The principle of acoustic measurements is that the propagation of the acoustic wave through the solid substrate of the sensor is affected by changes in the adjacent medium containing the analyte of interest. In a typical biosensing experiment, a receptor molecule is immobilised on the sensor surface, and the ligand is offered from solution or vice versa [12]. If there is molecular recognition and binding, a shift in the resonance frequency of the crystal is induced. Adsorbed mass on the device surface has a linear relationship with the change in the wave velocity and can be determined by monitoring the wave phase of frequency change. In the case of a solid elastic layer, the mass deposited on the device surface is linearly related to frequency change, based on the known Sauerbrey equation [11]. On the other hand, the insertion loss is a measure of the extent to which energy is dissipated as the wave travels across the surface and is a function of viscous/viscoelastic losses. If a viscous film is in contact with the device, a simple relationship can be obtained between the viscosity-density product and the drop in the efficiency of the signal transmission. This dampening factor offers the possibility to detect not only mass changes but also viscoelastic and conformational changes of interactions.

The acoustic signal is very sensitive to properties of the contacting liquid medium, i.e., temperature, pressure, viscosity or ionic strength, as well as specific biological interactions with the sensor surface. Liquid in contact with the sensor surface will couple with the oscillating surface. The thickness of the oscillating liquid layer, termed penetration depth, is given by δ = (ηρ/2πf)1/2, where η is the interface viscosity, ρ is the liquid density, and f is the operating frequency. The outer boundary of the layer is taken to be the point where the wave amplitude has decayed to 1/e of its initial value. So, depending on the frequency, the penetration depth is adjusted accordingly for the same values of viscosity and density; with increasing frequency, the penetration depth decreases.

Acoustic sensors have been used in the label-free detection of numerous analytes of a broad range, from interfacial chemistries and lipid membranes to small molecules and whole cells [13], providing a unique method for observing in real-time contact mechanics, interfacial dynamics, surface roughness, viscoelasticity, density and mass. The information collected from acoustic biosensors is beyond that offered by more widely adopted optical techniques, such as surface plasmon resonance (SPR) sensors. SPR sensors are still not very suitable for measurements that involve cells since they only detect mass adsorbed on the sensor surface [14]. In the case of cell binding, the signal of SPR sensors is dominated by the contribution from the main cell body present in the evanescent field. So, they have mostly been used to measure responses of attached cell layers to soluble factors [15–18].

Acoustic sensors and cell adhesion

Two types of shear acoustic wave devices have been used for the study of cellular events: quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) resonators, operated in the thickness shear mode (TSM), and surface acoustic wave (SAW) sensors, operated in the Love-wave configuration.

Quartz crystal microbalance sensors

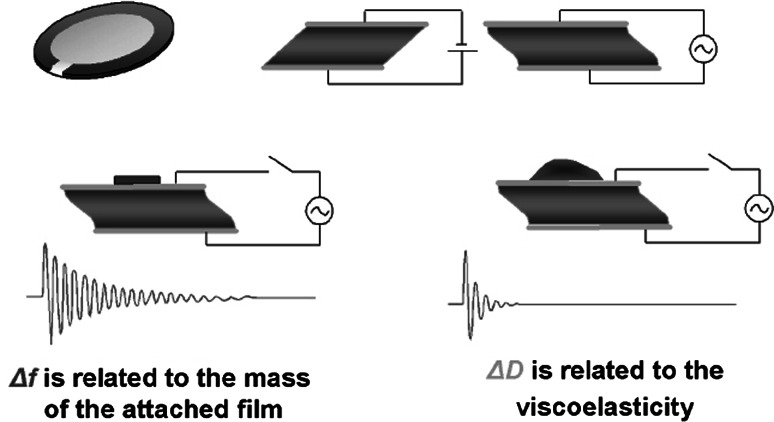

The QCM is the most commonly used acoustic sensor type, mostly due to its simple geometry [19]. QCM devices consist of a piezoelectric substrate (quartz) of thicknesses less than 0.5 mm with two electrodes in the form of gold patches deposited on the opposite sides of the substrate. An oscillating electrical potential difference between the two surface electrodes induces a mechanical oscillation and vice versa. Commercially available QCM sensors operate in the range of 5–27 MHz as the basic frequency and can also monitor simultaneously other harmonics, up to 81 MHz (e.g., Q-sense: www.q-sense.com, or Initium: www.initium2000.com). In this operating range, QCM sensors are very sensitive to mass deposition and are comparable to SPR sensors [20]. The corresponding measured quantities are the frequency, F, and the insertion loss of the acoustic wave, the later recorded either as dissipation of the acoustic wave, D, or as resistance in the equivalent electric circuit, R (Fig. 1). When the sensor is used as culture substrate for animal cells, it serves as a transducer that monitors mechanical cell/substrate interactions. Moreover, the upper electrode of the QCM sensor can also function as the working electrode in an electrochemical cell [20]. This arrangement, termed electrochemical QCM (EQCM), allows electrochemical processes to be carried out in a controlled fashion at an applied potential, while mass and energy dissipation changes are simultaneously recorded.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the QCM-D principle of operation. The frequency of the oscillating crystal is related to the total oscillating mass, while the energy dissipation is related to the viscoelastic properties of the oscillating mass. Thus, changes in the mass induced upon adsorption of a rigid protein provide a change in frequency only, while if the mass is not rigid, which is often the case for biomolecules, there is a clear detectable change in the energy dissipation of the oscillating system. (Source: http://www.q-sense.com)

Surface acoustic wave sensors

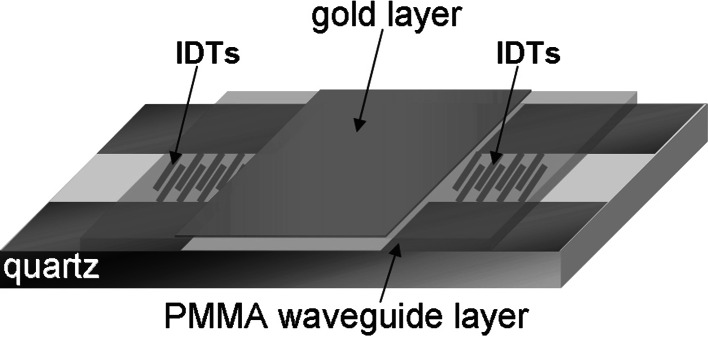

SAW devices use piezoelectric materials (e.g., quartz or lithium tantalate) to generate an acoustic wave. Surface acoustic waves are acoustic, mechanical waves that propagate confined to the surface of a piezoelectric crystal. In a SAW device, an electrical signal is converted at interdigital transducers into polarised waves that travel parallel to the sensing surface, utilising the piezoelectric properties of the substrate. Most often, SAW sensors operate at frequencies ranging from 25 to 500 MHz. Coupling of any medium contacting the surface strongly affects the velocity and/or the amplitude of the wave and the sensitivity of SAW sensors increases by the square root of the operating frequency. They are less frequently used for biomolecular analysis compared to QCM sensors, since they are not yet commercially available [21]. One SAW sensor configuration with high potential for biomolecular interactions [22] is the Love-wave sensor (Fig. 2). In this configuration, the transmitted acoustic wave is confined to an independent guiding layer, termed the waveguide layer, deposited on top of the piezoelectric substrate; the acoustic energy is concentrated there rather than in the bulk of the piezoelectric material, resulting in enhanced sensitivity to surface-binding events [21, 23]. To monitor interactions that occur as a function of time on the device surface, data can be collected at one operating frequency by measuring the change in phase, ΔPh, in degrees and the insertion loss or amplitude of the acoustic wave, ΔA, in dB. The change in phase is directly proportional to the adsorbed mass for continuous elastic films such as metal layers deposited on the device surface.

Fig. 2.

Schematic illustration of the acoustic Love-wave biosensor. The surface of the quartz-based acoustic-wave device, where two interdigitated transducers (IDTs) are deposited, is covered with a polymer guiding layer, in our case from poly-methylmethacrylate (PMMA). A thin layer of gold is deposited on top of the waveguide layer and between the IDTs. (Source: Saitakis et al. [41])

Adhesion of cells on surfaces

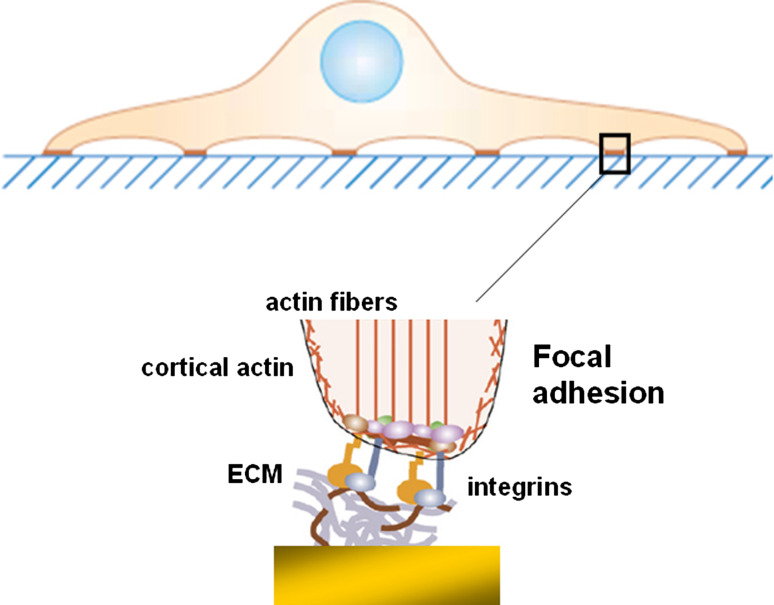

Cell adhesion is pivotal for the survival, the proliferation and the differentiation of animal cells. Moreover, attachment and spreading of cells to a surface are complex processes and require the establishment of specific molecular interactions between cell membrane receptors and surface-immobilised ligands. The most prominent cell surface receptors are integrins, which bridge the gap between cell and substrate. Usually, integrins tend to cluster, forming a point of focal adhesion [24]; these focal adhesions are sites of close contact between the cell and the substrate. Moreover, the cell body may be further away from the surface in other places of the contact area besides the focal adhesions. So, the contact area of a cell with a surface can vary in either the molecular composition of the cell-surface bonds and/or the width and distance between the cell and the surface (Fig. 3). The mechanical properties of living cells now are determined by the cytoskeleton, i.e., an intracellular network of protein filaments. There are two major classes of filaments that constitute the dynamic part of the eukaryotic cytoskeleton: actin microfilaments and microtubules [25], which are formed by polymerisation of actin or tubulin molecules, respectively. The actin microfilaments determine the mechanical properties of the cell membrane, since they form a network under the membrane that stabilises it, called the cortical actin. Moreover, the attachment of cells to protein-coated surfaces is mediated by the integrins, which are intracellularly connected to cortical actin [26]. These interactions of cell membrane molecules with their ligands are distinct from the binding interactions that occur when soluble molecules are used. Techniques that can offer analysis of these interactions would be very useful to study the function of cell adhesive molecules in their native environment, i.e., the membrane of living cells.

Fig. 3.

Focal adhesion of a cell on extracellular matrix proteins. Binding is mediated by integrins, which are intracellularly connected to the actin cytoskeleton

Applications of acoustic sensors to cell studies

Monitoring of cell attachment to surfaces

QCM sensors have been used for the study of eukaryotic cell adhesion. These studies took advantage of the sensor properties to detect mass adsorption in liquid and differences in viscoelasticity of the probed biological layer, and tried to provide new information on cell behavior in real time. Particularly, various cell types were seeded at various numbers and under various conditions on top of sensor surfaces covered with protein layers (Table 1), and the process of cell adhesion was monitored in real-time, via the change in frequency, non-invasively, and providing information about different molecular mechanisms responsible for cell attachment and spreading. The experimental setup in some studies incorporated a temperature-controlled cage containing the sensor holder and device. From the reported experiments, it was shown that there was a linear relationship between surface coverage with cells and the change in resonance frequency of the quartz crystal [27–32]. This frequency change was proportional to fractional surface coverage. and when the surface was fully covered in cells, no additional signal change was observed. Moreover, scanning electron microscopy observation of cell spreading showed that it was closely correlated with the observed shift in frequency [32].

Table 1.

Attachment and spreading of mammalian cell types monitored in real time by the QCM sensor

| Cell type | Surface type | References |

|---|---|---|

| Neonatal rat calvaria osteoblasts | Gold adsorbed serum proteins | Redepenning et al. [28] |

| African green monkey kidney (Vero) cells | Gold adsorbed serum proteins | Gryte et al. [27] |

| Canine MDCK-I, MDCK-II epithelial cells | Gold adsorbed serum proteins | Janshoff et al. [34] |

| Canine MDCK-I, MDCK-II epithelial and murine Swiss 3T3 fibroblast cells | Gold adsorbed serum proteins | Wegener et al. [29] |

| Canine MDCK-I, MDCK-II epithelial, porcine choroid plexus epithelial, murine Swiss 3T3 fibroblast and bovine aortic endothelial | Gold adsorbed serum proteins | Wegener et al. [30] |

| Bovine aortic endothelial cells | Gold adsorbed serum proteins | Zhou et al. [35], Marx et al. [59] |

| African green monkey kidney TC7, human ovarian cancer HeLa, human lung carcinoma A549 cells | Gold adsorbed serum proteins | Galli Marxer et al. [42] |

| Canine MDCK-II cells | Gold adsorbed serum proteins | Reiss et al. [46], |

| Human ovarian cancer OV-MZ-6 cells | Gold adsorbed fibronectin, vitronectin and laminin | Li et al. [44] |

| Bovine aortic endothelial and human breast cancer MCF-7 cells | Gold adsorbed serum proteins | Marx et al. [68] |

| Bovine aortic endothelial cells | Gold adsorbed gelatine and poly-d-lysine | Hong et al. [65] |

| Rat liver epithelial WB F433 and human lung melanoma B16F10 cells | Gold adsorbed vitronectin and laminin | Fohlerova et al. [36] |

| Canine MDCK-II, rat epithelial-like NRK-52E and murine fibroblast NIH-3T3 cells | Gold adsorbed gelatin | Heitmann and Wegener [45] |

| Human skin fibroblast cells | Gold adsorbed fibronectin | Li et al. [53] |

| Murine pre-osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells | Gold adsorbed serum proteins | Li et al. [37] |

| Human breast cancer MCF-7 cells | Gold adsorbed serum proteins | Tan et al. [48] |

| Human B-lymphoblastoid LG2 cells | Gold adsorbed protein G and antibody | Saitakis et al. [49] |

Interestingly, the frequency shifts observed for cell attachment to the sensor surface did not obey the Sauerbrey equation [33], which provides quantification of surface-deposited elastic mass. This suggested that the signal was mostly due to viscoelastic changes close to the surface. Therefore, for more detailed information related to cell/surface interactions, it was necessary to measure additional parameters such as the resistance R or the dissipation D of the acoustic wave. Janshoff et al. [34] were the first to show that the presence of a cell layer mainly increased damping of the acoustic wave. The cells, therefore, did not exhibit pure mass-load behaviour, meaning that adherent cells behave more like a viscoelastic material than a rigid mass film with considerable dissipation of energy [29, 30, 35–37].

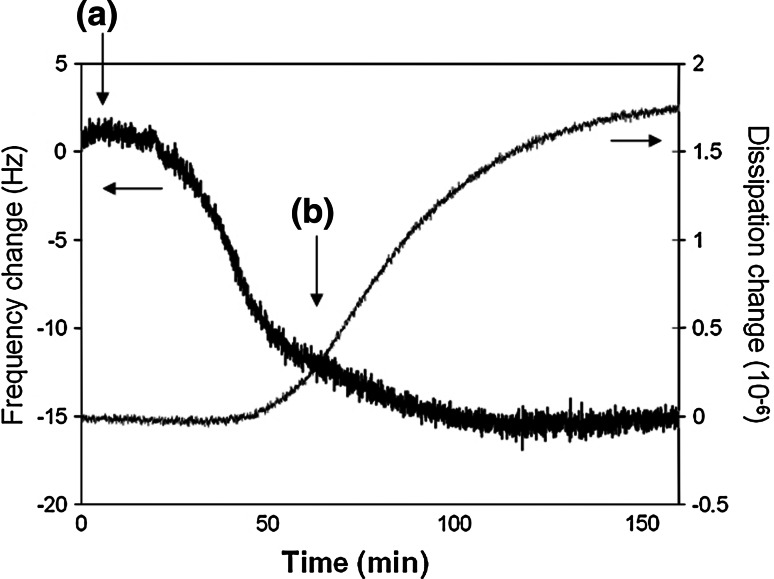

In general, attachment and spreading of cells on the sensor surface yield a sigmoidal acoustic profile in both frequency and dissipation/resistance (Fig. 4). This response shows the steps of cell adhesion on artificial surfaces, i.e., initial diffusion and capture (lag phase), isotropic bond formation between cell membrane receptors and the abundant surface immobilised ligands (log phase) and anisotropic stabilisation of cell/substrate contacts and/or focal adhesion formation (final phase) [38–41]. In case of cell death, reversibility of the acoustic signal is observed, since the dead cells become more spherical and may detach from the sensor surface [42, 43]. However, the attachment and growth of cells on surfaces are rather complicated processes consisting of several successive steps, including the contact of cells with substrate surface, the secretion of extracellular matrix (ECM), the rearrangement of cytoskeleton, the integrin-mediated connection of ECM with cytoskeleton network, the spreading and migration of cells for increasing contacting surface and cell division. The goal of further studies then was to identify the individual contributions of various parameters.

Fig. 4.

Real-time frequency and dissipation change of the QCM sensor during the addition of HLA-expressing human lymphoblastoid cells over an anti-HLA antibody-modified gold surface. a Addition of cell sample (106 cells ml−1), b wash with buffer

As mentioned above and presented in Table 1, most cell studies involved adhesion of cells to QCM gold electrodes covered with a protein layer. These specific protein/protein binding interactions were mediated by cell membrane receptors interacting with ECM or other surface-immobilised proteins. When the adhesion of different cell lines was investigated under identical experimental conditions, each cell line caused unique individual shifts of the resonance frequency [29]. Moreover, a comparison of surfaces coated with various adhesive ECM proteins (e.g., fibronectin, vitronectin, laminin) confirmed the role of these molecules in mediating cell adhesion to the quartz surface via specific interactions with integrin molecules at the cell membrane [30, 36, 44, 45]. Only specific interactions lead to the observed frequency changes, whereas the sole presence of the cellular body in close vicinity to the quartz surface is barely detectable [33]. Therefore, the QCM technique offered very high sensitivity to processes limited to the region where the actual adhesion occurs, including the corresponding molecular interactions. This was also confirmed with the use of soluble peptides as inhibitors for the binding of integrins to their ligands. These anti-adhesive peptides (with RGDS or GRGDS amino acid sequences) inhibited, in a concentration-dependent manner, the interaction of integrins with the surface-attached adhesive proteins, so the cells were unable to form attachment points and thus focal adhesions with the sensor surface. A comparison was also made between cells and lipid vesicles concerning their attachment to the QCM sensor surface [46]. Results showed that although changes in frequency are very similar for intact liposomes and mammalian cells, the energy dissipation due to viscoelasticity is significantly higher when cells attach and spread on the sensor surface.

In other studies, the chemical and morphological properties of the surface, such as hydrophilicity, hydrophobicity and surface roughness, were found to be important to the attachment and spreading of cells on QCM sensors [47, 48]. In such studies, kinetic information and mechanical properties of the attached cell layers were obtained from plotting dissipation versus frequency for the adhesion experiments. Another way to express acoustic measurements is via the acoustic ratio of ΔD/ΔF. This ratio represents the energy loss per unit of attached mass and provides both qualitative and quantitative information on the intrinsic properties and morphology of the sensed interface. Particularly, the ΔD/ΔF ratio would depend on the deposited mass, its viscoelastic properties and the shape and structure of the cells as a function of time [47, 49–51]. When ΔD/ΔF ratios between different biomolecules were compared, cells displayed a nearly purely viscous behavior, similar to the one obtained for the application of glycerol solutions to the QCM device surface [49, 52].

Real-time detection of the effect of soluble factors on cell layers at the sensor surface

When cell layers are attached on the surface of an acoustic sensor, they can be subjected to various soluble factors that affect their physiology, such as inhibitors of the adhesion process, substances that perturb the cytoskeleton or agents that promote cell signaling or apoptosis. There have been several reports of real-time treatments of cells already attached to the sensor surface with various soluble factors (Table 2). In fact, any small drug molecule or larger biomolecule (e.g., protein) that has an effect on the viscoelastic/mechanical properties of the attached cells can be potentially detected by the acoustic sensors.

Table 2.

Soluble factors added over cell layers

| Soluble factor | Cell layer | References |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-adhesive peptides (GRGDS, RGD, SDGRG) | Canine MDCK-I, MDCK-II epithelial and murine Swiss 3T3 fibroblast cells | Wegener et al. [29] |

| Anti-adhesive peptides (GRGDS, SDGRG), cytochalasin D | Canine MDCK-I, MDCK-II epithelial, porcine choroid plexus epithelial, murine Swiss 3T3 fibroblast and bovine aortic endothelial cells | Wegener et al. [30] |

| Fibroblast growth factor | Bovine aortic endothelial cells | Zhou et al. [35] |

| Nocodazole | Bovine aortic endothelial cells | Marx et al. [59] |

| Cytochalasin D, latrunculin B, jaspakinolide, nocodazole, paclitaxel | African green monkey kidney TC7, human ovarian cancer HeLa, human lung carcinoma A549 cells | Galli Marxer et al. [42] |

| Paclitaxel, docetaxel | Human breast cancer MCF-7 and MD-MBA-231 cells | Braunhut et al. [43] |

| Nocodazole, taxol | Bovine aortic endothelial and human breast cancer MCF-7 and MD-MBA-231 cells | Marx et al. [60] |

| Gold nanoparticles and paclitaxel | Human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells | Wei et al. [76], |

| Cytochalasin D | Human skin fibroblast cells | Li et al. [53] |

| Fluorescent polystyrene microspheres | Human oral epithelial H376 cells | Elsom et al. [62] |

| Concanavalin A, wheat germ agglutinin | Human hepatic normal (L-02) and cancer (Bel7402) cells | Tan et al. [63] |

| Glutaraldehyde, t-butylhydroperoxide | Human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells | Kang and Muramatsu [64], |

| Adriamycin, selenium nanoparticles | Human hepatic cancer Bel7402 cells | Tan et al. [48] |

| Cytochalasin D | Human B-lymphoblastoid LG2 cells | Saitakis et al. [49] |

| Selenium-ferroferric oxide nanocomposites | Human osteoblast-like MG-63 cells | Zhou et al. [78] |

Cellular response was monitored in real time by the QCM sensor

Acoustic sensors have been used to probe changes in the actin cytoskeleton close to the basal cell membrane and determine their effect on the overall mechanical properties of cell layers. Experiments usually employed a cell layer attached to the sensor surface via integrin/ligand binding. This attached cell layer was then subjected to various concentrations of actin cytoskeleton-tampering drugs [30, 42, 53], such as cytochalasin D (CytD), jasplakinolide (Jas) or latrunculin B (LatB). CytD and LatB disrupt the actin cytoskeleton by inhibiting actin polymerisation into filaments [54, 55], while Jas induces polymerisation of actin and stabilisation of filaments [56]. The effects of these drugs on the cell layer were an increase in cell stiffness and cytosolic viscocity and the eventual desorption of cells from the surface [30, 42, 53], despite their opposite effect on actin cytoskeleton. The QCM sensor detected the above events in a dose-dependent fashion by the reversion of frequency change upon CytD, LatB and Jas treatment of the cell layer.

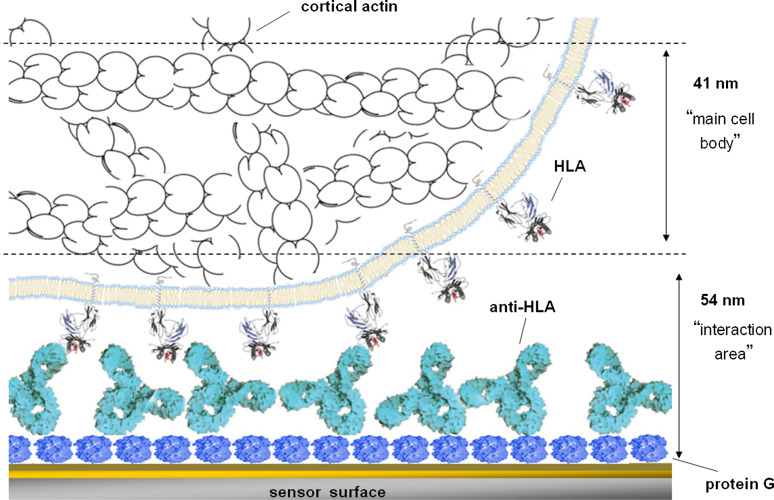

Furthermore, the resistance or dissipation of the QCM sensor displayed a reversion of the signal upon CytD treatment [49, 53], which can be attributed to loss of strong adhesion of cells with the substrate and the subsequent cell shape changes due to the cytoskeleton disruption. The changes in cell shape were confirmed after microscopic observation, which showed that CytD treatment caused cells to adopt a more spherical shape on the sensor surface compared to the untreated adhesion profile [49, 53]. The response of the QCM sensor to CytD was recently compared to a Love-wave sensor [49]. The amplitude signal of the Love-wave sensor, equivalent to dissipation measurements of the QCM sensor, did not detect the mechanical changes induced by CytD treatment of an attached cell layer. It was shown that this difference in response between the two types of acoustic sensors could be mainly attributed to the different penetration depths; the QCM penetration depth of 95 nm detected the disruption of cortical actin while the Love-wave penetration depth of 54 nm was apparently too short to sense it (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Schematic illustration of the sensor interface for cells interacting via membrane HLA-A2 molecules with surface-immobilised antibodies. Inside the cell, cortical actin microfilaments are shown. The two dashed lines indicate the penetration depths for the Love-wave (54 nm) and the QCM sensor (95 nm) (not drawn to scale). (Source: Saitakis et al. [41])

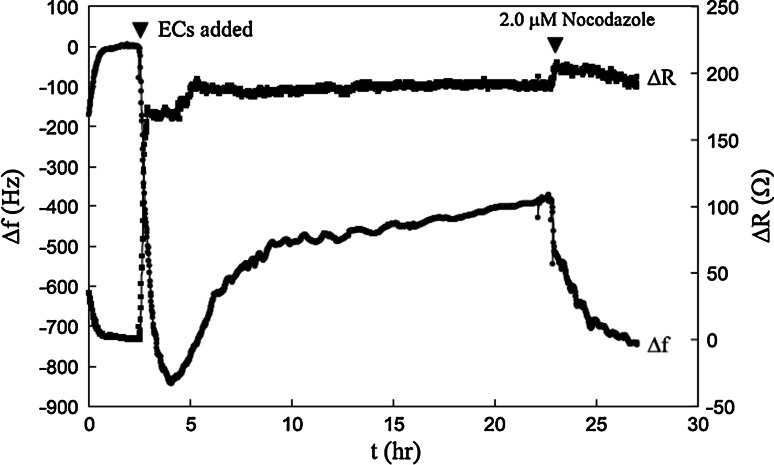

The other dynamic component of the cytoskeleton, the microtubule network, has also been investigated with QCM sensors. The drugs nocodazole (Noc) and taxol were employed for this task. Noc leads to microtubule depolymerisation [57], while taxol induces microtubule stabilisation [58]. Confluent layers of endothelial cells were subjected to various concentrations of these drugs [59, 60]. The QCM sensor detected significant dose-dependent frequency and resistance changes in response to Noc treatment (Fig. 6), which were the result of complete disruption of intracellular microtubules. This caused a loss in the spread shape of the cells and a concomitant loss in viscoelastic behaviour. A different response was produced by taxol treatment, which exhibited little signal change, behaviour consistent with its hyperstabilisation effect on microtubules [60]. The kinetics of frequency change for Noc treatment were also well fitted by a single first-order exponential time decay relationship. This suggested that, as a result of Noc treatment, the QCM sensor detected a single dynamic sensing system, the microtubule network within the attached cells. The above experiments demonstrate that the QCM sensor can provide important information on the condition of the cytoskeleton.

Fig. 6.

Time-dependent behavior of the Endothelial Cell QCM biosensor created by the addition of 2 × 104 endothelial cells (first arrowhead). The frequency (Δf) and resistance (ΔR) changes were recorded continuously until steady-state condition. Nocodazole was added to a final 2 μM concentration (second arrowhead). (Source: Marx et al. [59])

Further applications of the QCM device for studying the behaviour of attached cell layers have been reported. These included the real-time detection of endothelial cell stimulation by fibroblast growth factor via frequency change [35]; the frequency and dissipation monitoring of exocytosis and endocytosis of attached cells [61]; the recording of responses of viable human oral epithelial cells to microspheres under conditions of flow [62]; the real-time monitoring via frequency and resistance changes of the agglutination process of normal and tumour cells by lectins (concanavalin A and wheat germ agglutinin), resulting in the discrimination of normal and tumour cells [63]; and the investigation of the effect of the chemical stressors glutaraldehyde and t-butylhydroperoxide to an attached cell layer [64].

Measurement of cell/substrate interactions mediated by specific protein/protein binding

Current techniques for evaluating cell spreading and cell adhesion strength are labour intensive and destructive (e.g., flow detachment assay). Moreover, they are not sufficient for providing the detailed kinetics of the adhesion process. Acoustic biosensors have the potential to study cell membrane molecule interactions in their native environment, taking advantage of both the frequency (or phase) and the dissipation (or amplitude) measurements for the analysis of cell/substrate interactions.

The QCM sensor has been used to monitor specific, integrin-mediated adhesion of human cancer cells to distinct extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, fibronectin, vitronectin, laminin [44] and gelatine [65, 66] immobilised on the device gold surface. The operating frequency was routinely between 5 and 35 MHz. Impedance analysis was used to detect the attachment of cells and showed that the induced increase in viscoelasticity (measured as resonance bandwidth, equivalent to dissipation) was reproducible and proportional to cell numbers, while frequency shifts were much less regular [44]. The particular cells used expressed the integrin αvβ3. Acoustic experiments showed that the cells displayed strong adhesion to fibronectin- and vitronectin-coated gold surfaces and weak binding to laminin. The QCM sensor also distinguished between cells expressing αvβ3 at a standard and at a ten-fold amount on the cell surface, where the higher integrin-expressing cells displayed higher overall bandwidth change but only when vitronectin was used as a coating ECM protein.

As mentioned above, anti-adhesive peptides, such as GRGDS, RGDS or RGD, can be used to affect the adhesion behavior of cells on the surface of a QCM sensor [29, 30, 44, 65]. The peptides were added in solution over an already established cell layer and competitively interacted with the integrin receptors on the cell membrane, thus blocking integrin binding on the surface of the sensor. The cell adhesion sites were also titrated by using different concentrations of the RGDS peptide in acoustic experiments, yielding a sigmoidal curve for the attachment of epithelial cells (measured as overall frequency change) as a function of peptide concentration. This allowed the calculation of half-maximal efficiency of the RGDS peptide [67]. The titration of cell adhesion sites can also be performed when detachment is measured at a cell layer. The addition of peptides in solution resulted in the displacement of integrin binding to the soluble peptides rather than the surface immobilised adhesive proteins, which in turn loosened the overall cell/substrate contacts [44, 67]. Similar results were obtained when the cell layers where treated with chelator factors such as EDTA or EGTA, which sequestered bivalent cations necessary for integrin/ligand binding and resulted in the reversion of frequency and resistance shifts [68]. These experiments were feasible because of the high sensitivity of the QCM sensor. However, the cell/substrate system is still too complicated to be completely analysed with an acoustic sensor at the molecular level. Such complexity could be the result of the nature of cell attachment, where the blocking of integrin/ligand interactions may lead to the binding on the surface via a different molecular receptor, such as glycans of the cell surface or cadherins.

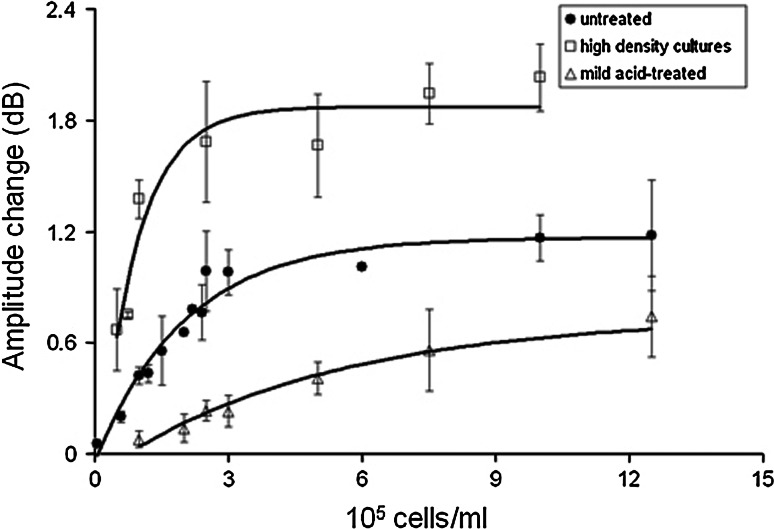

The above-mentioned reports mostly studied the cell/substrate interaction in an indirect fashion by measuring the molecular binding per se. So, in a different approach, the molecular interaction itself was under investigation using both the QCM and the Love-wave sensors [41, 49]. The class I major histocompatibility complex molecule HLA-A2 was used as a cell membrane receptor, and an anti-HLA antibody was used as the immobilised ligand. Cells were also manipulated prior to the experiments to present different numbers of the cell membrane HLA molecules. The combination of the QCM and the Love-wave sensor confirmed that the acoustic signal is mostly sensitive to the cell/substrate contacts and that the presence of the cells in the vicinity of the sensor surface does not produce a signal change. Moreover, there were differences in the acoustic readout of the two sensor systems. In the case of the Love-wave sensor, amplitude change was very sensitive and could be used to differentiate between different cell numbers and different numbers of cell membrane receptors (Fig. 7), while phase change was less sensitive and did not provide consistent results [41, 49]. In the case of the QCM sensor, both frequency and dissipation could detect differences in cell numbers, but not in numbers of cell membrane receptors [49]. This was mainly attributed to the different operating frequencies, hence the penetration depth of the sensors. The QCM sensor, with a penetration depth of 95 nm, probed a larger part of the cell body. So, frequency could not resolve the type of sensed cells because of the small mass change contributed by the difference in the numbers of cell membrane HLA molecules (which were doubled between samples). Moreover, energy dissipation due to the HLA/anti-HLA bonds was less dominant in the overall dissipation shift. Instead, the Love-wave sensor has a penetration depth of 54 nm, which corresponds to the depth of the interaction interface between cell and substrate. Therefore, the Love-wave sensor detected the formation of cell membrane receptor/immobilised ligand bonds via the energy flow from the acoustic wave to the attached cells. This resulted in a quantitative method to discriminate between cells with different receptor numbers and to measure cell/substrate bonds by acoustic damping of the Love-wave sensor. Since the amplitude signal change was found to be a measure for the formation of cell/substrate bonds, kinetic information could be deduced from the real-time binding curves. Therefore, the real-time amplitude change data were fitted by a single first-order exponential time decay relationship and were correlated with the two-dimensional surface densities of the cell membrane HLA molecules to derive the kinetic parameters of the HLA/anti-HLA interaction [41]. This was an interaction in two dimensions (2D), so it yielded the 2D kinetic constants and the 2D affinity constant [69] of the interaction.1 The 2D binding parameters were for the first time calculated using a biosensor system, providing a novel means of better understanding the binding mechanisms of membrane molecule interactions. Another conclusion of the above studies is that the QCM and the Love-wave sensor can potentially answer important questions in cell biology if used in a complementary fashion.

Fig. 7.

Amplitude change of the Love-wave sensor at equilibrium as a function of human lymphoblastoid cells added over the sensor surface (error bars correspond to standard deviation, n = 3 or 4) for three different numbers of the cell membrane HLA molecules. The values were: 3.7–5.7 × 105 HLA molecules per untreated cell, 1–10 × 104 molecules per mild acid-treated cell and 9.7–10.0 × 105 per cell from a high density culture. (Source: Saitakis et al. [49])

In other studies, acoustic sensors were employed to assess the effect of surface charge and the membrane glycocalyx on the cell adhesion process. The glycocalyx is a layer formed on the cell surface by the glycan moieties of glycoproteins and glycolipids. It constitutes a negatively charged “cloud” originating from heparan sulfate and sialic acid residues of the glycans [70]. In QCM sensor experiments, bovine endothelial cells were treated with the enzyme heparinase III [65, 66], which cleaves heparan sulfate residues from cell membrane glycans, prior to their addition over a positively charged poly-d-lysine (PDL) coated sensor surface, and the cell adhesion process was followed in real time. PDL does not support integrin binding and focal adhesion formation, so the cells attached via non-specific electrostatic bonds between the positively charged immobilised PDL and the negatively charged cell membrane heparan sulphate proteoglycans. Heparinase-treated cells, which were less negatively charged, displayed lowered adhesion to the PDL-coated surface than untreated cells as indicated by lower frequency and resistance shifts. In Love-wave sensor experiments, HLA-expressing human lymphoblastoid cells were treated with the enzyme neuraminidase, which cleaves sialic acid residues from cell membrane glycans prior to their addition over an anti-HLA coated sensor surface [71]. The cell adhesion efficiency as a function of glycocalyx condition was evaluated by the calculation of 2D binding parameters of the HLA/anti-HLA interaction from the real-time amplitude data, with or without enzyme treatment. Results showed that binding was facilitated by neuraminidase treatment, yielding a 3.6-fold higher 2D binding affinity constant due to the presence of a less dense and less negatively charged glycocalyx at the cell/substrate interface.

Clinical applications

The potential of acoustic sensors as tools for the detection of clinically important samples has been tested by the use of an integrated QCM sensor array, employed in the immunophenotyping of acute leukaemia [72–74]. This QCM array employed 5-MHz operating sensors and took advantage of immobilised antibody fragments to detect surface markers of acute leukemic lineages. The frequency shift of the QCM sensor was used to detect target cells in patient blood samples in acceptable agreement with those clinically classified by current techniques, such as immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry and fluoroimmunoassay [72]. An optimisation of the technique, which employed antibodies attached to protein A-conjugated nanogold particles on the sensor surface, showed improved results with regard to signal response and biocompatibility [74]. This array method provides a direct and simple analytical procedure without multiple labelling and separation steps, and has the potential to become an alternative technique applicable for clinical immunophenotyping of leukaemias. Further optimisations of this technique used immunomagnetic or aptamer-conjugated particles [73, 75] to selectively enrich target cells in clinical samples.

The QCM sensor also offers the potential to test the response of tumour cells to chemotherapeutic agents. In literature, this was shown by testing the response of human tumour cells to the taxane molecules paclitaxel and docetaxel [43], a combination of a paclitaxel and gold nanoparticles [76], the drug adriamycin and selenium nanoparticles [77] and paramagnetic Se-Fe3O4 nanoparticles [78]. The QCM sensor recorded frequency and resistance changes as a result of taxane treatment of the tumour cells and revealed a two-phase mechanism of action for apoptosis induction [43]. It was also shown by frequency measurements from the QCM sensor that the combination of paclitaxel and gold nanoparticles [76] and that of adriamycin with selenium nanoparticles [77] enhanced the induction of apoptosis of tumour cells in a synergistic fashion. The effect of paramagnetic Se-Fe3O4 nanoparticles on tumour cells was tracked with or without induction of an external magnetic field, revealing an increase in tumour cell apoptosis with the external magnetic field [78]. These experiments present the QCM sensor as a powerful diagnostic tool for detecting, distinguishing and measuring the effectiveness of drugs on tumour cell treatment.

Determination of biomaterial compatibility with cells

The continuous gathering of novel information and increasing understanding of the mechanisms of cell/cell and cell/substrate interactions provides a driving force for development of biomaterials in medical implant and tissue engineering applications. Current biomaterial research is limited by the availability of rapid and versatile tools for the evaluation of real-time cell/surface interactions in vitro, since it is generally accepted that the biocompatibility of a material is closely connected with cell adhesion onto an artificial surface. The acoustic sensors have proven to be such a tool for monitoring cell adhesion and, hence, have been used for assessment of biomaterials. The QCM sensor was usually employed to monitor via frequency and dissipation measurements the attachment and spreading of various types of cells on potential biocompatible surfaces (Table 3).

Table 3.

Surfaces tested for cell attachment and spreading by the QCM sensor

| Surface type | Cell type | References |

|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene (hydrophobic or hydrophilic) | Monkey kidney epithelial and Chinese hamster ovary epithelial cells | Fredriksson et al. [47] |

| Supported lipid bilayers on SiO2 | Rat pancreatoma AR4-2 J and murine mammary epithelial HC11cells | Andersson et al. [86] |

| Tantalum and oxidised polystyrene coated with albumin, fibronectin and serum proteins | Murine NIH-3T3 fibroblast cells | Lord et al. [31] |

| Tantalum and chromium | Murine pre-osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells | Modin et al. [32] |

| Poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methacrylate) with poly-l-lysine and biotin | Chinese hamster ovary epithelial cells | Lee et al. [53] |

| Polyporfyrin-modified gold | Human breast cancer MCF-7 cells | Guo et al. [82] |

| Poly(ethyleneimine), poly(sodium-4-styrenesulfonate), poly(allylamine-hidrochloride) | Human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells | Saravia and Toca-Herrera [83] |

| Fibronectin-peptide modified gold | Human fibroblast McCoy cells | Satriano et al. [84] |

| Hydroxyapatite and gold coated with osteopontin | Human bone mesenchymal cells | Jensen et al. [80] |

The potential of biomaterial surfaces for supporting osteogenic differentiation and tissue integration requires the attachment and spreading of bone-forming cells. The QCM sensor was used to compare the adhesion of pre-osteoblastic cells on tantalum and chromium surfaces [32] and displayed higher frequency and dissipation shifts on the tantalum modified surface, meaning more efficient cell attachment on tantalum. The signal change for frequency and dissipation was also used to indicate fibroblast attachment on tantalum and oxidised polystyrene surfaces coated by various serum proteins [31]. Results detected distinct cell behaviour on the different surfaces. One protein with potential to induce high osteoconductivity is osteopontin [79], which may act as a functional coating on orthopaedic implants. Osteopontin adsorption on hydroxyl-apatite and gold was investigated, as well as the promotion of the attachment of human mesenchymal cells [80]; cell attachment and spreading were found to be more efficient on the osteopontin/hydroxyapatite surface than on the osteopontin/gold surface and bare hydroxyapatite or gold surfaces.

For the fabrication of cell-based biosensors, it is important to seed the cells onto a surface with excellent protein and cellular compatibility. Synthetically formed surfaces, such as poly-electrolyte films, were shown to promote the attachment and spreading of cells [81]. The suitability of electropolymerised porphyrin [82], poly-ethyleimine and poly-sodium-styrenesulfonate [83] and peptide-modified poly-siloxane [84] was assessed. Poly-porphyrin was found to be a good substrate for the attachment of cells and the subsequent real-time acoustic monitoring of cell response to cytotoxic mercury chloride [82]. The QCM sensor, employed in parallel with optical microscopy and atomic force microscopy, provided real-time information on the attachment and spreading of cells on the poly-electrolyte-modified surfaces, with higher frequency decrease and dissipation increase on poly-ethyleimine [83]. Moreover, the combination of techniques allowed integrated analysis of the cell adhesion process, displaying the potential of using various techniques that can complement each other. Satriano et al. [84] prepared artificial surfaces presenting a fibronectin-derived peptide adsorbed to poly-siloxane. The attachment and spreading of fibroblast cells was monitored, revealing different kinetics for the cell/substrate interaction.

Supported lipid bilayers have been shown to possess protein and cell repellent properties when unmodified, so they are considered as a useful model to study membrane molecules at their native molecular environment. The QCM sensor was used to monitor the formation of supported lipid bilayers on the sensor surface [85–87]. This lipid layer was further tested towards its ability to promote or inhibit cell attachment [86]; little or no attachment of cells on plain phosphatidyl-choline bilayers was observed, suggesting potential applications of promoting the biocompatibility of materials.

Other cell studies with acoustic sensors

The QCM sensor was used to detect the contraction of an attached layer of smooth muscle cells [88], its growth on different protein coated surfaces [89] and its response to various ions and hydrogen peroxide [90]. These experiments highlight the potential of the sensor for the development and screening cardiovascular drugs. Another application was the real-time monitoring of neuronal adhesion on artificial surfaces [91, 92]. Neurons differ in patterns of adhesion, growth and networking on artificial substrates compared to other cells, and the sensor displayed sufficient sensitivity to monitor neuronal growth [91], while the responses of neurons to electrolyte solutions were measured by frequency and resistance changes [92].

A novel approach regarding acoustic sensors is using the device not only as a sensor, but also as an actuator to induce oscillations of the surface, an approach called rupture event scanning [45]. By using the QCM device in this dual mode, Heitmann and Wegener [45] reported the adhesion of mammalian cells as a function of lateral shear amplitude, which could retard or omit adhesion to the quartz surface. Also, the use of the same device in tandem with electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) showed that the sensor can assess the dynamics of the adherent cells and that these techniques provide different results, so they can be used in a complementary fashion to each other [93]. Finally, frequency and dissipation measurements were used to detect subtle fluctuations of the cell bodies as an indicator for micromotility, an assay for the detection of malignant cells [94].

Comparison to other techniques

A traditional way to monitor the attachment and spreading of cells on surfaces and study cell/substrate interactions in a quantitative manner would be the measurement of cell detachment strength by employing laminar shear flow or centrifugal forces and determining the fraction of cells capable of remaining on the substrate for a given mechanical stress. Acoustic sensors provide a very powerful alternative to such methods [95]. The QCM sensor can reliably report on the number of cells on the surface, as compared to cytological techniques, and is able to detect subtle mechanical differences of adhering cells that are not detectable by fluorescence microscopy [67].

Acoustic sensors can indeed monitor and analyse mechanical changes of the attached cell layers. However, this analysis is an averaging of the phenomena over a cell population on the surface rather than a laterally resolved image within a cell layer or within different regions of a single cell, which can be achieved by better suited techniques, such as scanning force microscopy. On the other hand, acoustic sensors provide better time resolution and non-invasive measurements compared to other mechanical techniques. This may have important applications. For instance, they could be used in cell cultures to constantly monitor the numbers and condition of the cultured cells, where the real-time analysis can occur without cell manipulation and removal from the cell culture environment [67]. Moreover, it is important to note that while scanning force microscopy provides the mechanical properties of the upper (apical) cell membrane, an acoustic sensor is sensitive to mechanical changes at the lower (basal) cell membrane. So, these techniques can also be used in a complementary fashion to analyse cell mechanics. Another technique to monitor cell attachment and spreading in cell cultures is time-lapse videomicroscopy, which, however, is labour-intensive and does not provide quantitative information.

The QCM sensor has been used for studying drug effects on living cells. It was suggested that it offers certain advantages over other techniques, since it detects the response of whole cellular compartments upon addition of a drug. This is a form of signal amplification by the cells and cell layers, where the intact metabolic and signalling pathways respond to the drug, instead of the localised drug response measured by optical biosensors on specific targets [20].

Acoustic “visualisation” of cell footprints on the surface is yet another possibility. Techniques that can also monitor the basal side of cells with high sensitivity are reflection interference contrast microscopy (RICM) and fluorescence interference constrast microscopy (FLIC). RICM and FLIC can be used in parallel to QCM to provide information of contact area formation [67, 96], since they detect proximity to the surface. Although acoustic sensors cannot achieve the sensitivities of these optical techniques, which require labelling with chromophores specifically chosen for optimisation and detection, they offer the advantage of non-invasiveness without the need for labels, hence providing broader applicability.

It was recently shown that the Love-wave sensor can offer a measure of cell/substrate bonds via acoustic damping [41]. This led to the calculation of 2D binding parameters for the molecular interaction [41, 71], which are considered more biologically relevant to the function of membrane proteins [69]. Using the Love-wave sensor for the calculation of 2D kinetic and affinity constants presents several advantages over the currently employed fluorescence and mechanical techniques. Fluorescence techniques were used to derive 2D binding affinities during the application of receptor-expressing cells on a glass-supported lipid bilayer with fluorescently tagged ligands [97–100]. Mechanical techniques, such as the flow chamber assay [4] and the micropipette method [101, 102], are based on the fact that two surfaces, e.g., cell/cell or cell/substrate, are cross-linked via the formation of receptor/ligand bonds. These methods were used to determine the 2D dissociation rate constant from measurements of the lifetime of single-molecule-mediated adhesion. A combination of these methods can provide both the 2D kinetics and affinity for an interaction, but such an approach would be labour-intensive and difficult to miniaturise in order to apply to multiple sensing platforms. As a result, the direct measurement of the number of cell/substrate bonds offered by the Love-wave sensor presents a significant advantage for 2D binding parameter calculation. However, it is not possible to discriminate the effect of lateral diffusion of membrane molecules and contact area formation on cell/substrate bond formation with the Love-wave sensor. This is in contrast to the fluorescence technique, which offers direct observation of the established contact areas [103, 104]. Therefore, these techniques can be used in a complementary fashion to isolate and elucidate different mechanisms of the biophysics of cell adhesion.

Conclusions

The most important advantages of acoustic biosensors in the analysis of cell attachment and spreading are the speed of detection, the real-time non-invasive approach and the in-depth analysis based on integrated information of mass and mechanical properties. From this literature survey, it is apparent that acoustic sensors detect cells mostly via their sensitivity in viscoelasticity and mechanical properties. The sensors are sensitive to the basal membrane of the cells and the adhesion proteins on the surface. They can directly detect the effect of small molecules on established cell layers. The QCM sensor, in particular, detects cytoskeletal rearrangements caused by specific drugs. The Love-wave sensor can directly measure cell/substrate bonds via acoustic damping and provide 2D kinetic and affinity parameters. Combination of these acoustic systems can provide important insight into interactions occurring in any cell/substrate interface, such as binding of immune cells and receptors to their ligands, where not only binding per se but also the affinity, the extent or the half-life of binding are of importance. Acoustic sensors can be extremely useful in evaluating the cytocompatibility of artificial surfaces, as required for the development of medical implants and tissue engineering. The only limitation seems to be the prerequisite to use a pre-adsorbed material film that is of limited thickness and does not produce significant acoustic damping. As shown above, the exceptional response of acoustic sensors to soluble factors can be used as a diagnostic tool for chemotherapy agents or other membrane active compounds. Therefore, the acoustic sensors have the potential to become automated monitoring devices to be used for high-throughput screening of novel drugs targeting the cell membrane. In this format, the sensors could be employed in arrays and would either detect the many different cell/substrate interactions or act as support for whole-cell biosensors, where the cells form the sensory element to detect soluble factors. Further advances in microfluidics can soon make these acoustic arrays feasible [105, 106]. The acoustic sensors also have the potential to be integrated into cell cultures or bioreactors to provide a real-time feed of the number and/or condition of the cultured cells. Finally, novel developments are on the way to advance the applicability of acoustic biosensors. These improvements would include: increase in mass sensitivity, design of hybrid devices, i.e., SPR or ellipsometry combined with SAW or QCM [107], easier determination of kinetics, application of cells as sensory elements and improved software for automated control and data analysis [108]. Acoustic biosensor systems could then fulfill their potential as powerful tools in cellular analysis, and become more accessible and user-friendly to cell biologists.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. A. Tsortos for helpful discussions and for critically reading the manuscript. ELKE-University of Crete is acknowledged for financial support (research grant K.A. 2732).

Abbreviations

- QCM

Quartz crystal microbalance

- SAW

Surface acoustic wave

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- HLA

Human leukocyte antigen

Footnotes

Interactions of molecules in apposed surfaces are analysed differently from interactions of soluble molecules. The main difference is that soluble molecules are treated as molar concentrations of molecules, while the surface-tethered molecules are considered surface densities. As a result, the surface-associated events, such as binding of membrane molecules, are governed by two-dimensional kinetics and affinity [69], where association rate (k a) and binding affinity (K A) constants are expressed in μm2 s−1 per molecule and μm2 per molecule, respectively, instead of the traditional k a in M−1 s−1 and K A in M−1.

References

- 1.Gumbiner BM. Cell adhesion: the molecular basis of tissue architecture and morphogenesis. Cell. 1996;84(3):345–357. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alon R, Hammer DA, Springer TA. Lifetime of the P-selectin-carbohydrate bond and its response to tensile force in hydrodynamic flow. Nature. 1995;374(6522):539–542. doi: 10.1038/374539a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berg EL, Goldstein LA, Jutila MA, Nakache M, Picker LJ, Streeter PR, Wu NW, Zhou D, Butcher EC. Homing receptors and vascular addressins: cell adhesion molecules that direct lymphocyte traffic. Immunol Rev. 1989;108:5–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1989.tb00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen S, Springer TA. Selectin receptor-ligand bonds: formation limited by shear rate and dissociation governed by the Bell model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(3):950–955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Juliano RL. Membrane receptors for extracellular matrix macromolecules: relationship to cell adhesion and tumor metastasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;907(3):261–278. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(87)90009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huppa JB, Davis MM. T-cell-antigen recognition and the immunological synapse. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(12):973–983. doi: 10.1038/nri1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Springer TA. Adhesion receptors of the immune system. Nature. 1990;346(6283):425–434. doi: 10.1038/346425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Merwe PA, Davis SJ. Molecular interactions mediating T cell antigen recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:659–684. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abraham VC, Taylor DL, Haskins JR. High content screening applied to large-scale cell biology. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22(1):15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor DL, Woo ES, Giuliano KA. Real-time molecular and cellular analysis: the new frontier of drug discovery. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2001;12(1):75–81. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(00)00180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ballantine DS, White RM, Martin SJ, Ricco AJ, Zellers ET, Frye GC, Wohltjen H. Acoustic wave sensors. San Diego: Academic Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gizeli E, Lowe CR. Biomolecular sensors. London: Taylor & Francis Inc.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper MA, Singleton VT. A survey of the 2001 to 2005 quartz crystal microbalance biosensor literature: applications of acoustic physics to the analysis of biomolecular interactions. J Mol Recognit. 2007;20(3):154–184. doi: 10.1002/jmr.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper MA, Whalen C. Profiling molecular interactions using label-free acoustic screening. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2005;2(3):241–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang Y, Ferrie AM, Fontaine NH, Yuen PK. Characteristics of dynamic mass redistribution of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in living cells measured with label-free optical biosensors. Anal Chem. 2005;77(17):5720–5725. doi: 10.1021/ac050887n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang Y, Ferrie AM, Fontaine NH, Mauro J, Balakrishnan J. Resonant waveguide grating biosensor for living cell sensing. Biophys J. 2006;91(5):1925–1940. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.077818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yanase Y, Suzuki H, Tsutsui T, Hiragun T, Kameyoshi Y, Hide M. The SPR signal in living cells reflects changes other than the area of adhesion and the formation of cell constructions. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;22(6):1081–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Endo T, Yamamura S, Kerman K, Tamiya E. Label-free cell-based assay using localized surface plasmon resonance biosensor. Anal Chim Acta. 2008;614(2):182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodahl M, Hook F, Krozer A, Brzezinski P, Kasemo B. Quartz-crystal microbalance setup for frequency and Q-factor measurements in gaseous and liquid environments. Rev Sci Instrum. 1995;66(7):3924–3930. doi: 10.1063/1.1145396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marx KA. The quartz crystal microbalance and the electrochemical QCM: applications to studies of thin polymer films, electron transfer systems, biological macromolecules, biosensors, and cells. In: Steinem C, Janshoff A, editors. Piezoelectric sensors. Berlin: Springer; 2007. pp. 371–424. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gronewold TM. Surface acoustic wave sensors in the bioanalytical field: recent trends and challenges. Anal Chim Acta. 2007;603(2):119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2007.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gizeli E. Acoustic transducers. In: Gizeli E, Lowe CR, editors. Biomolecular sensors. London: Taylor & Francis Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gizeli E, Bender F, Rasmusson A, Saha K, Josse F, Cernosek R. Sensitivity of the acoustic waveguide biosensor to protein binding as a function of the waveguide properties. Biosens Bioelectron. 2003;18(11):1399–1406. doi: 10.1016/S0956-5663(03)00080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110(6):673–687. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doherty GJ, McMahon HT. Mediation, modulation, and consequences of membrane-cytoskeleton interactions. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:65–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bray JJ, Fernyhough P, Bamburg JR, Bray D. Actin depolymerizing factor is a component of slow axonal transport. J Neurochem. 1992;58(6):2081–2087. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb10949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gryte DM, Ward MD, Hu WS. Real-time measurement of anchorage-dependent cell-adhesion using a quartz crystal microbalance. Biotechnol Progr. 1993;9(1):105–108. doi: 10.1021/bp00019a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Redepenning J, Schlesinger TK, Mechalke EJ, Puleo DA, Bizios R. Osteoblast attachment monitored with a quartz-crystal microbalance. Anal Chem. 1993;65(23):3378–3381. doi: 10.1021/ac00071a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wegener J, Janshoff A, Galla HJ. Cell adhesion monitoring using a quartz crystal microbalance: comparative analysis of different mammalian cell lines. Eur Biophys J. 1998;28(1):26–37. doi: 10.1007/s002490050180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wegener J, Seebach J, Janshoff A, Galla HJ. Analysis of the composite response of shear wave resonators to the attachment of mammalian cells. Biophys J. 2000;78(6):2821–2833. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76825-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lord MS, Modin C, Foss M, Duch M, Simmons A, Pedersen FS, Milthorpe BK, Besenbacher F. Monitoring cell adhesion on tantalum and oxidised polystyrene using a quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation. Biomaterials. 2006;27(26):4529–4537. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Modin C, Stranne AL, Foss M, Duch M, Justesen J, Chevallier J, Andersen LK, Hemmersam AG, Pedersen FS, Besenbacher F. QCM-D studies of attachment and differential spreading of pre-osteoblastic cells on Ta and Cr surfaces. Biomaterials. 2006;27(8):1346–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sauerbrey G. Verwendung von Schwingquartzen zur Wagung dunner Schichten und zur microwagung. Z Phys. 1959;155:206–222. doi: 10.1007/BF01337937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janshoff A, Wegener J, Sieber M, Galla HJ. Double-mode impedance analysis of epithelial cell monolayers cultured on shear wave resonators. Eur Biophys J. 1996;25(2):93–103. doi: 10.1007/s002490050021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou T, Marx KA, Warren M, Schulze H, Braunhut SJ. The quartz crystal microbalance as a continuous monitoring tool for the study of endothelial cell surface attachment and growth. Biotechnol Prog. 2000;16(2):268–277. doi: 10.1021/bp000003f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fohlerova Z, Skladal P, Turanek J. Adhesion of eukaryotic cell lines on the gold surface modified with extracellular matrix proteins monitored by the piezoelectric sensor. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;22(9–10):1896–1901. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li F, Wang JH, Wang QM. Thickness shear mode acoustic wave sensors for characterizing the viscoelastic properties of cell monolayer. Sensor Actuat B Chem. 2008;128:399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2007.06.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dubin-Thaler BJ, Giannone G, Dobereiner HG, Sheetz MP. Nanometer analysis of cell spreading on matrix-coated surfaces reveals two distinct cell states and STEPs. Biophys J. 2004;86(3):1794–1806. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74246-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reinhart-King CA, Dembo M, Hammer DA. The dynamics and mechanics of endothelial cell spreading. Biophys J. 2005;89(1):676–689. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.054320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cuvelier D, Thery M, Chu YS, Dufour S, Thiery JP, Bornens M, Nassoy P, Mahadevan L. The universal dynamics of cell spreading. Curr Biol. 2007;17(8):694–699. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saitakis M, Dellaporta A, Gizeli E. Measurement of two-dimensional binding constants between cell-bound major histocompatibility complex and immobilized antibodies with an acoustic biosensor. Biophys J. 2008;95(10):4963–4971. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.132118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galli Marxer C, Collaud Coen M, Greber T, Greber UF, Schlapbach L. Cell spreading on quartz crystal microbalance elicits positive frequency shifts indicative of viscosity changes. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2003;377(3):578–586. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-2080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braunhut SJ, McIntosh D, Vorotnikova E, Zhou T, Marx KA. Detection of apoptosis and drug resistance of human breast cancer cells to taxane treatments using quartz crystal microbalance biosensor technology. Assay Drug Dev Techn. 2005;3(1):77–88. doi: 10.1089/adt.2005.3.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li J, Thielemann C, Reuning U, Johannsmann D. Monitoring of integrin-mediated adhesion of human ovarian cancer cells to model protein surfaces by quartz crystal resonators: evaluation in the impedance analysis mode. Biosens Bioelectron. 2005;20(7):1333–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heitmann V, Wegener J. Monitoring cell adhesion by piezoresonators: impact of increasing oscillation amplitudes. Anal Chem. 2007;79(9):3392–3400. doi: 10.1021/ac062433b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reiss B, Janshoff A, Steinem C, Seebach J, Wegener J. Adhesion kinetics of functionalized vesicles and mammalian cells: a comparative study. Langmuir. 2003;19(5):1816–1823. doi: 10.1021/la0261747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fredriksson C, Kihlman S, Rodahl M, Kasemo B. The piezoelectric quartz crystal mass and dissipation sensor: a means of studying cell adhesion. Langmuir. 1998;14(2):248–251. doi: 10.1021/la971005l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan L, Xie Q, Jia X, Guo M, Zhang Y, Tang H, Yao S. Dynamic measurement of the surface stress induced by the attachment and growth of cells on Au electrode with a quartz crystal microbalance. Biosens Bioelectron. 2009;24(6):1603–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saitakis M, Tsortos A, Gizeli E. Probing the interaction of a membrane receptor with a surface-attached ligand using whole cells on acoustic biosensors. Biosens Bioelectron. 2010;25(7):1688–1693. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsortos A, Papadakis G, Gizeli E. Shear acoustic wave biosensor for detecting DNA intrinsic viscosity and conformation: a study with QCM-D. Biosens Bioelectron. 2008;24(4):836–841. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Papadakis G, Tsortos A, Gizeli E. Acoustic characterization of nanoswitch structures: application to the DNA holliday junction. Nano Lett. 2010;10(12):5093–5097. doi: 10.1021/nl103491v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Melzak K, Tsortos A, Gizeli E. Use of acoustic sensors to probe the mechanical properties of liposomes. Methods Enzymol. 2009;465:21–41. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)65002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li F, Wang JH, Wang QM. Monitoring cell adhesion by using thickness shear mode acoustic wave sensors. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;23(1):42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cooper JA. Effects of cytochalasin and phalloidin on actin. J Cell Biol. 1987;105(4):1473–1478. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.4.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coue M, Brenner SL, Spector I, Korn ED. Inhibition of actin polymerization by latrunculin A. FEBS Lett. 1987;213(2):316–318. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81513-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakano MY, Boucke K, Suomalainen M, Stidwill RP, Greber UF. The first step of adenovirus type 2 disassembly occurs at the cell surface, independently of endocytosis and escape to the cytosol. J Virol. 2000;74(15):7085–7095. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.15.7085-7095.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoebeke J, Van Nijen G, De Brabander M. Interaction of oncodazole (R 17934), a new antitumoral drug, with rat brain tubulin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976;69(2):319–324. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(76)90524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schiff PB, Fant J, Horwitz SB. Promotion of microtubule assembly in vitro by taxol. Nature. 1979;277(5698):665–667. doi: 10.1038/277665a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marx KA, Zhou T, Montrone A, Schulze H, Braunhut SJ. A quartz crystal microbalance cell biosensor: detection of microtubule alterations in living cells at nM nocodazole concentrations. Biosens Bioelectron. 2001;16(9–12):773–782. doi: 10.1016/S0956-5663(01)00219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marx KA, Zhou T, Montrone A, McIntosh D, Braunhut SJ. A comparative study of the cytoskeleton binding drugs nocodazole and taxol with a mammalian cell quartz crystal microbalance biosensor: different dynamic responses and energy dissipation effects. Anal Biochem. 2007;361(1):77–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cans AS, Hook F, Shupliakov O, Ewing AG, Eriksson PS, Brodin L, Orwar O. Measurement of the dynamics of exocytosis and vesicle retrieval at cell populations using a quartz crystal microbalance. Anal Chem. 2001;73(24):5805–5811. doi: 10.1021/ac010777q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elsom J, Lethem MI, Rees GD, Hunter AC. Novel quartz crystal microbalance based biosensor for detection of oral epithelial cell-microparticle interaction in real-time. Biosens Bioelectron. 2008;23(8):1259–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tan L, Jia X, Jiang XF, Zhang YY, Tang H, Yao SZ, Xie QJ. Real-time monitoring of the cell agglutination process with a quartz crystal microbalance. Anal Biochem. 2008;383(1):130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kang HW, Muramatsu H. Monitoring of cultured cell activity by the quartz crystal and the micro CCD camera under chemical stressors. Biosens Bioelectron. 2009;24(5):1318–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2008.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hong S, Ergezen E, Lec R, Barbee KA. Real-time analysis of cell-surface adhesive interactions using thickness shear mode resonator. Biomaterials. 2006;27(34):5813–5820. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ergezen E, Hong S, Barbee KA, Lec R. Real time monitoring of the effects of Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycan (HSPG) and surface charge on the cell adhesion process using thickness shear mode (TSM) sensor. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;22(9–10):2256–2260. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heitmann V, Reiss B, Wegener J. The quartz crystal microbalance in cell biology: basics and applications. In: Steinem C, Janshoff A, editors. Piezoelectric sensors. Berlin: Springer; 2007. pp. 303–338. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marx KA, Zhou T, Montrone A, McIntosh D, Braunhut SJ. Quartz crystal microbalance biosensor study of endothelial cells and their extracellular matrix following cell removal: evidence for transient cellular stress and viscoelastic changes during detachment and the elastic behavior of the pure matrix. Anal Biochem. 2005;343(1):23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dustin ML, Bromley SK, Davis MM, Zhu C. Identification of self through two-dimensional chemistry and synapses. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:133–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shaw AS, Dustin ML. Making the T cell receptor go the distance: a topological view of T cell activation. Immunity. 1997;6(4):361–369. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Saitakis M, Gizeli E. Quantification of the effect of glycocalyx condition on membrane receptor interactions using an acoustic wave sensor. Eur Biophys J. 2011;40(2):209–215. doi: 10.1007/s00249-010-0632-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang H, Zeng H, Liu Z, Yang Y, Deng T, Shen G, Yu R. Immunophenotyping of acute leukemia using an integrated piezoelectric immunosensor array. Anal Chem. 2004;76(8):2203–2209. doi: 10.1021/ac035102x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang H, Zeng H, Shen G, Yu R. Immunophenotyping of acute leukemias using a quartz crystal microbalance and monoclonal antibody-coated magnetic microspheres. Anal Chem. 2006;78(8):2571–2578. doi: 10.1021/ac051286z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zeng H, Wang H, Chen F, Xin H, Wang G, Xiao L, Song K, Wu D, He Q, Shen G. Development of quartz-crystal-microbalance-based immunosensor array for clinical immunophenotyping of acute leukemias. Anal Biochem. 2006;351(1):69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pan YL, Guo ML, Nie Z, Huang Y, Pan CF, Zeng K, Zhang Y, Yao SZ. Selective collection and detection of leukemia cells on a magnet-quartz crystal microbalance system using aptamer-conjugated magnetic beads. Biosens Bioelectron. 2010;25(7):1609–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wei XL, Mo ZH, Li B, Wei JM. Disruption of HepG2 cell adhesion by gold nanoparticle and Paclitaxel disclosed by in situ QCM measurement. Colloid Surface B. 2007;59(1):100–104. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tan L, Jia XE, Jiang XF, Zhang YY, Tang H, Yao SZ, Xie QJ. In vitro study on the individual and synergistic cytotoxicity of adriamycin and selenium nanoparticles against Bel7402 cells with a quartz crystal microbalance. Biosens Bioelectron. 2009;24(7):2268–2272. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2008.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhou YP, Jia XE, Tan L, Xie QJ, Lei LH, Yao SZ. Magnetically enhanced cytotoxicity of paramagnetic selenium-ferroferric oxide nanocomposites on human osteoblast-like MG-63 cells. Biosens Bioelectron. 2010;25(5):1116–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lee YJ, Park SJ, Lee WK, Ko JS, Kim HM. MG63 osteoblastic cell adhesion to the hydrophobic surface precoated with recombinant osteopontin fragments. Biomaterials. 2003;24(6):1059–1066. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(02)00439-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jensen T, Dolatshahi-Pirouz A, Foss M, Baas J, Lovmand J, Duch M, Pedersen FS, Kassem M, Bunger C, Soballe K, Besenbacher F. Interaction of human mesenchymal stem cells with osteopontin coated hydroxyapatite surfaces. Colloid Surface B. 2010;75(1):186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lakard S, Herlem G, Valles-Villareal N, Michel G, Propper A, Gharbi T, Fahys B. Culture of neural cells on polymers coated surfaces for biosensor applications. Biosens Bioelectron. 2005;20(10):1946–1954. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Guo M, Chen J, Zhang Y, Chen K, Pan C, Yao S. Enhanced adhesion/spreading and proliferation of mammalian cells on electropolymerized porphyrin film for biosensing applications. Biosens Bioelectron. 2008;23(6):865–871. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Saravia V, Toca-Herrera JL. Substrate influence on cell shape and cell mechanics: HepG2 cells spread on positively charged surfaces. Microsc Res Tech. 2009;72(12):957–964. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]