Abstract

The plasmin–antiplasmin system plays a key role in blood coagulation and fibrinolysis. Plasmin and α2-antiplasmin are primarily responsible for a controlled and regulated dissolution of the fibrin polymers into soluble fragments. However, besides plasmin(ogen) and α2-antiplasmin the system contains a series of specific activators and inhibitors. The main physiological activators of plasminogen are tissue-type plasminogen activator, which is mainly involved in the dissolution of the fibrin polymers by plasmin, and urokinase-type plasminogen activator, which is primarily responsible for the generation of plasmin activity in the intercellular space. Both activators are multidomain serine proteases. Besides the main physiological inhibitor α2-antiplasmin, the plasmin–antiplasmin system is also regulated by the general protease inhibitor α2-macroglobulin, a member of the protease inhibitor I39 family. The activity of the plasminogen activators is primarily regulated by the plasminogen activator inhibitors 1 and 2, members of the serine protease inhibitor superfamily.

Keywords: Plasmin(ogen), α2-Antiplasmin, Serine protease inhibitors (serpins), Plasminogen activators, Plasminogen activator inhibitors, α2-Macroglobulin, Multidomain serine proteases

Introduction [1]

The plasmin–antiplasmin system holds a key position in blood coagulation and fibrinolysis. A schematic representation of the fibrinolytic system with its main components is given in Fig. 1 [2]. The plasmin–antiplasmin system controls and regulates the dissolution of the fibrin polymers into soluble fragments (for details see later sections). As with every complex system, blood coagulation and fibrinolysis also have to be tightly controlled and regulated. Plasminogen (Pgn) is activated by its two main physiological activators, tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) and urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA). Plasmin (Plm) is inhibited by its main physiological inhibitor α2-antiplasmin (A2PI) and the general protease inhibitor α2-macroglobulin (α2M). The activities of tPA and uPA are regulated by their two main physiological inhibitors, the plasminogen activator inhibitors 1 and 2 (PAI-1 and PAI-2).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the main components of the fibrinolytic system (adapted from reference [2]). sc-tPA, tc-tPA single-chain, two-chain tPA; sc-uPA, tc-uPA single-chain, two-chain uPA; PAIs plasminogen activator inhibitors

The structural data for the proteins involved in the plasmin–antiplasmin system discussed in this review article are compiled in Table 1.

Table 1.

Structural data for the main proteins involved in the plasmin–antiplasmin system

| Protein (abbreviation) | UniProt entry | Sizeb | Plasma concentration (mg l−1) | Gene | Domains | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daltons | Amino acids | Name | Size (kb) | ||||

| Plasminogen (Pgn) | P00747/EC 3.4.21.7 | 88,432 | 791 | 100–200 | PLG | 52.5 | 1 NTP of Pgn, 5 K, serine protease |

| Tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) | P00750/EC 3.4.21.68 | 59,042 | 527 | 0.005–0.01 | PLAT | 32.4 | 1 EGF-like, 2 K, 1 FN1, serine protease |

| Urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) | P00749/EC 3.4.21.73 | 46,386 | 411 | 0.005–0.01 | PLAU | 6.4 | 1 EGF-like, 1 K, serine protease |

| α2-Antiplasmin (A2PI) | P08697 | 50,451 | 452 | ~70 | SERPINF2 | ~16 | |

| α2-Macroglobulin (α2M) | P01023 | 160,797 | 1,451 | ~1,200 | A2M | ~48 | |

| Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) | P05121 | 42,769 | 379 | ~0.024 (variable) | SERPINE1 | 12.2 | |

| Plasminogen activator inhibitor 2 (PAI-2) | P05120 | 46,596 | 415 | <0.01 | SERPINB2 | 16.4 | |

| Neuroserpin | Q99574 | 44,704 | 394 | not detectable | SERPINI1 | 89.8 | |

| Glia-derived nexin | P07093 | 41,865 | 379 | SERPINE2 | – | ||

bMass calculated from the amino acid sequence

Multidomain serine proteases

Many serine proteases in blood plasma are multidomain proteins, especially those involved in blood coagulation and fibrinolysis and those in the complement system. Usually, serine proteases are present in plasma in their inactive proenzyme or zymogen form. The catalytic activity is normally generated by a specific activation process involving limited proteolysis. The 3-D structure of a serine protease domain is usually characterized by two six-stranded antiparallel β-barrels surrounded by α-helical and 310-helical segments. The active site cleft with the catalytic triad His, Asp, and Ser is located at the interface of two structurally similar subdomains (see sections: Plasminogen, Tissue-type plasminogen activator, and Urokinase-type plasminogen activator). Besides the serine protease domain, multidomain serine proteases contain specific domains such as kringles, fibronectin (FN), and epidermal growth factor-like (EGF-like) domains, which mediate efficient binding to the target structures thus facilitating an efficient cleavage reaction of the serine protease which is usually strictly limited to the intended site. For instance, efficient binding of plasmin(ogen) to the fibrin blood clot is mediated by the lysine binding sites (LBS) located in the kringle domains of the molecule thus facilitating an efficient cleavage of the fibrin polymer by Plm into soluble fragments (for details see section Plasminogen). The most important structural data for the multidomain serine proteases Pgn, tPA, and uPA are summarized in Table 1.

Plasminogen [3–6]

Human Pgn (P00747, EC 3.4.21.7; concentration in plasma 100–200 mg l−1) is a single-chain, multidomain glycoprotein (about 2% CHO) of about 90 kDa (791 amino acids) and is a member of the peptidase S1 family present in blood as zymogen. Pgn is synthesized mainly in the liver as a protein 810 residues long [7], and mature Pgn, Glu-Pgn, comprises 791 amino acids generated during the secretion process by cleaving the 19-residue signal peptide [8]. Glu-Pgn is the proenzyme form of the serine protease Plm, the key component of the fibrinolytic system (Fig. 1). The gene for Pgn (PLG, 52.5 kb) is located on chromosome 6q26-6q27 and is organized into 19 exons in the range 75–387 bp [8–10]. In plasma, Pgn is partially bound to histidine-rich glycoprotein (P04196) [11]. Histidine-rich glycoprotein binds at sites of tissue injury and seems to act as a high-affinity receptor to immobilize Pgn on cell surfaces [12].

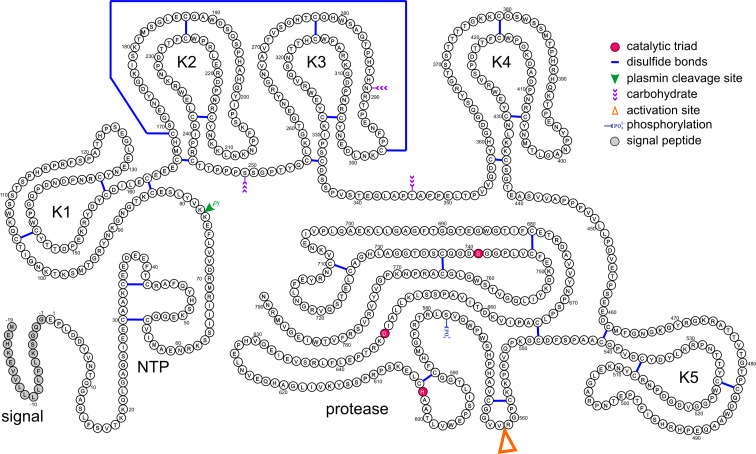

Pgn is composed of an N-terminal peptide (NTP) [13], five triple-loop structures stabilized by three intrachain disulfide bridges called kringles [14], and the trypsin-like serine protease part carrying the catalytic triad His603, Asp646, and Ser741 [15]. Human Pgn is partially N-glycosylated at Asn289 and O-glycosylated at Ser249 and Thr346 giving rise to Pgn variants I (Asn289, Thr346) and II (only Thr346), which can be readily separated by affinity chromatography [16–20]. In addition, Pgn is partially phosphorylated at Ser578 [21] with a so far unassigned function. The schematic organization of the primary structure of human Pgn is shown in Fig. 2 [2]. Two N-terminally different forms of Pgn have been identified, Glu-Pgn and Lys-Pgn. Lys-Pgn is formed by cleavage of the Lys77–Lys78 peptide bond in Glu-Pgn, releasing the NTP [22].

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of the primary structure of human Pgn (from reference [2]). The catalytic triad (His603, Asp646, and Ser741), the activation site (Arg561–Val562), the Plm cleavage site (Lys77–Lys78), the phosphorylation site (Ser578), the CHO attachment sites (Asn289, Ser249, and Thr346), and the 24 disulfide bridges as well as the signal peptide are indicated. NTP N-terminal peptide; K1–K5 kringles 1–5

Pgn is activated by the two main physiological plasminogen activators, tPA and uPA [23], to the active, two-chain Plm molecule held together by two interchain disulfide bridges (Cys548–Cys666, Cys558–Cys566) by cleavage of the Arg561–Val562 peptide bond and the release of the 77-residue NTP [24, 25]. Upon activation, Pgn undergoes an unusual conformational change usually not observed in proenzyme–enzyme pairs of the trypsin-type family [25]. Native Glu-Pgn exhibits a compact spiral shape, whereas Lys-Pgn and Plm have a more open, elongated structure. In addition to tPA and uPA, two bacteria-derived proteins, streptokinase A or C (A: P10520; C: P00779) and staphylokinase (P68802), can act as Pgn activators. They form equimolar complexes with Pgn, and this complex is able to activate Pgn [26, 27].

The heavy chain of Plm (483 amino acids) contains five homologous kringle structures, K1 (Cys84–Cys162), K2 (Cys166–Cys243), K3 (Cys256–Cys333), K4 (Cys358–Cys435), and K5 (Cys462–Cys541), with the disulfide bridges arranged in the pattern Cys1–Cys6, Cys2–Cys4, Cys3–Cys5. Kringles 2 and 3 are linked together in a clamp-like fashion by an additional interkringle disulfide bridge (Cys169–Cys297). With the exception of K3, each kringle contains a functional LBS characterized by anionic and cationic centres interspaced by a hydrophobic groove. In the case of human Pgn K1, the anionic and cationic centres contain two Asp and two Arg residues, respectively, and the hydrophobic groove is lined out with aromatic residues (one Trp, three Tyr, and one Phe) [28, 29]. The LBS mediate binding to the substrate fibrin(ogen) [30] and to its main physiological inhibitor A2PI [31–33] and to small molecules of the ω-aminocarboxylic acid type such as 6-aminohexanoic acid [34]. In addition, specific binding via kringle domain(s) to bacteria [35, 36] and to mammalian cell surfaces [37] has been described. K3 is the only kringle with a functionally inactive LBS [38, 39], but substitution of Lys311 to Asp in the anionic centre of the LBS results in a weak but distinct affinity for ω-aminocarboxylic acids [40]. The affinity of the antifibrinolytic drug 6-aminohexanoic acid for the various kringles decreases in the order K1 > K4 > K5 > K2 >> K3 [41–43].

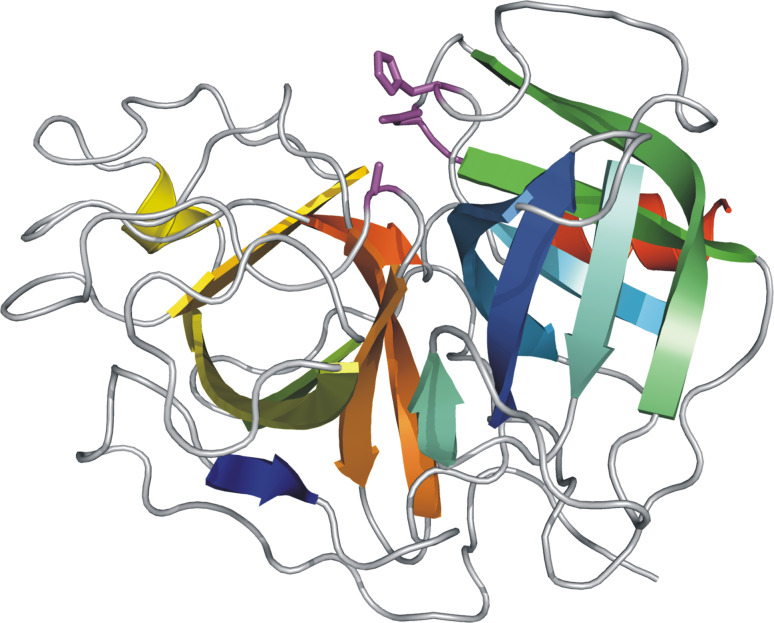

So far, no 3-D structure of complete human Pgn is available. A 3-D structural model of human Pgn based on known and overlapping 3-D structures of Pgn fragments exhibits the spiral shape shown in Fig. 3 [44], which resembles the known shape of Glu-Pgn visualized by electron microscopy [45, 46]. However, 3-D structural data for all kringle domains and of the catalytic chain are available. As an example, the 3-D structures of the triple-kringle domain K1 + 2 + 3 termed angiostatin (1KI0), determined by X-ray diffraction, is shown in Fig. 4 [47]. The kringle structures are characterized by a central cluster of four Cys residues composed of the two inner disulfide bridges (Cys2–Cys4, Cys3–Cys5), which are almost perpendicular to each other (as an example, see K2). The kringle domains have a rather low content of secondary structure with some β-strands but usually a low helical content. As an example, K1 is given in the surface representation with negatively and positively charged residues shown in red and in blue, respectively, and all other residues are shown in grey. The central Trp residue of the LBS is marked in magenta (indicated by an arrow). The binding of a ligand has little influence on the conformation but stabilizes the structure. The 3-D structure of the catalytic domain of human Pgn determined by X-ray diffraction (1DDJ) exhibits the expected trypsin-like shape, and is shown in Fig. 5 [25]. Each of the two structurally similar subdomains is characterized by an antiparallel β-barrel and the active site cleft is located at the interface of the two subdomains.

Fig. 3.

Top and bottom 3-D structural model of human Pgn based on overlapping 3-D structures of Pgn fragments (form reference [44]). Each kringle is shown in grey, the central Trp residue in each LBS is shown in magenta, the protease domain is shown in green, and the active site residues are shown in red

Fig. 4.

3-D structure of human Pgn kringles 1 + 2 + 3 (K1, K2, K3) termed angiostatin determined by X-ray diffraction (1KI0, [47]). Each kringle contains three disulfide bridges (yellow) arranged in the pattern Cys1–Cys6, Cys2–Cys4, Cys3–Cys5 exemplified in kringle 2 (K2). Kringle 1 (K1) is shown as a surface representation with negatively and positively charged residues shown in red and blue, respectively, and all other residues are shown in grey. The central Trp residue of the LBS is shown in magenta (arrow)

Fig. 5.

3-D structure of the catalytic domain of human Pgn determined by X-ray diffraction (1DDJ, [25]). The active site residues located at the interface of the two structurally similar subdomains are shown in magenta

The primary function of Plm is the cleavage of insoluble fibrin polymers at specific sites resulting in soluble fragments. A schematic representation of fibrinogen and the pattern of cleavage by Plm is shown in Fig. 6 [48]. The cleavage sites giving rise to the major fragments D and E of fibrin are indicated by black arrows. The degradation of the fibrin polymer by Plm is initiated by the cleavage of the Lys583–Met584 peptide bond in the Aα chain, followed by the cleavage of the peptide bonds Lys206–Met207 and Lys230–Ala231, also in the Aα chain, thus releasing a C-terminal 40-kDa fragment and generating fragment X (260 kDa). Cleavage of fragment X in all three chains results in one fragment Y (160 kDa) and one fragment D (100 kDa), and further cleavage of fragment Y produces a second fragment D and fragment E (60 kDa) [48].

Fig. 6.

Cleavage of human fibrinogen by Plm (from reference [48]). Schematic representation of fibrinogen, the fibrin polymer, the pattern of cleavage by Plm, and the main fragments generated. The main Plm cleavage sites are indicated by arrows. Cleavage of fibrin by Plm leads to the main fragments X (260 kDa), Y (160 kDa), D (100 kDa), and E (60 kDa)

In addition, Plm acts as a proteolytic factor in many other physiological processes such as mediation of cell migration by degrading the extracellular matrix, wound healing, tissue remodelling, angiogenesis, embryogenesis, and pathogen and tumour cell invasion [23, 49–54]. The rather broad specificity of Plm in vivo results in the inactivation and degradation of matrix proteins such as collagens, fibronectin (P02751), and laminins [55–57], and components of the blood coagulation cascade such as coagulation factor FVa, von Willebrand factor, and thrombospondin [56, 58, 59]. In vitro, Plm has a similar specificity to trypsin cleaving primarily peptide bonds after basic residues. The main physiological inhibitor of Plm is A2PI, a serpin, which is discussed in section α2-Antiplasmin or α2-plasmin inhibitor.

Defects or mutations in the PLG gene are the cause of thrombophilia (MIM 188050) [60], a form of recurrent thrombosis, and type I plasminogen deficiency (MIM 173350). Ligneous conjunctivitis (MIM 217090) is usually the most common and initial form of type I plasminogen deficiency and is a rare form of chronic conjunctivitis characterized by chronic tearing and redness of the conjunctivae [61, 62].

Plasminogen activators

There are two main physiological activators of Pgn, tPA and uPA, which are both multidomain serine proteases previously mentioned (see Table 1). Although tPA and uPA both catalyse the same reaction, namely the activation of Pgn to Plm by cleavage of the Arg561–Val562 peptide bond, and thus clearly have the same basic biological function at the molecular level, tPA and uPA have different biological roles. Whereas tPA is primarily responsible for the dissolution of the fibrin polymers by Plm and thus helps to maintain vascular haemostasis, uPA is predominantly involved in the generation of pericellular Plm activity for the degradation of the extracellular matrix and for other intercellular processes where Plm activity is required.

Tissue-type plasminogen activator

Human tPA (P00750, EC 3.4.21.68; concentration in plasma 5–10 μg l−1) is synthesized by various cell types such as endothelial cells and keratinocytes and also in the brain [63, 64]. It is a single-chain multidomain glycoprotein (about 7% CHO) of 70 kDa (527 amino acids) containing one O-glycosylation site at Thr61 and three N-glycosylation sites at Asn117, Asn184 (partial), and Asn448 [65, 66] and belongs to the peptidase S1 family [67]. The tPA gene (PLAT, 32.4 kb) is located on chromosome 8p12 and is organized into 14 exons in the range 43–914 bp [68, 69]. The single-chain form (proenzyme) itself exhibits a very high enzymatic activity compared with the fully active two-chain form of tPA, which is a unique property of the proenzyme form of serine proteases. The single-chain form is converted to the completely active, two-chain form held together by a single interchain disulfide bridge (Cys264–Cys395) upon cleavage of the Arg275–Ile276 peptide bond by Plm, kallikrein, or coagulation factor Xa [70]. The A-chain (275 amino acids) contains one FN1, one EGF-like, and two kringle domains and the B-chain (252 amino acids) comprises the serine protease part [71]. The second kringle in tPA carries an active LBS as do the kringles in Pgn [72], but kringle 1 is devoid of an active LBS. This seems to be due to the replacement of the usual Trp residue by a Ser in the hydrophobic cleft of the LBS in tPA kringle 1 [73].

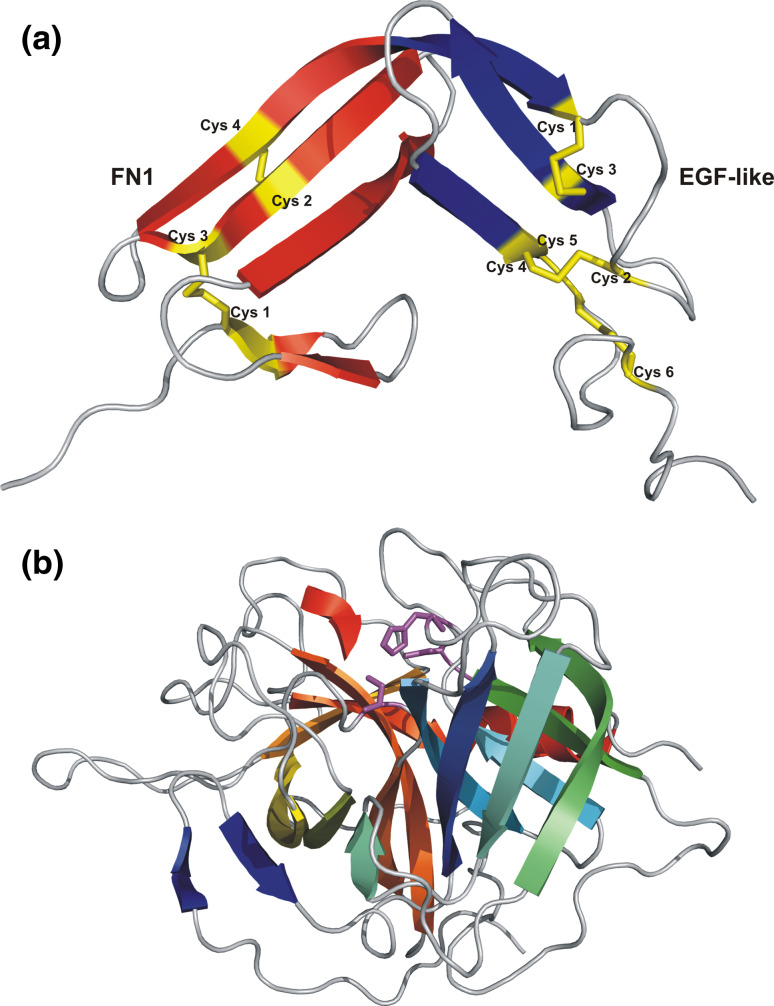

The 3-D structure of the double module FN1+EGF-like was determined by NMR spectroscopy (1TPG) and is shown in Fig. 7a [74]. The FN1 domain (43 amino acids) is characterized by two antiparallel β-sheets, a double stranded sheet and a triple-stranded sheet (shown in red), stabilized by two intrachain disulfide bridges arranged in the pattern Cys1–Cys3, Cys2–Cys4. The first disulfide bridge links the two β-sheets, the second disulfide bridge is located within the triple-stranded β-sheet. The EGF-like domain (39 amino acids) is characterized by two antiparallel, two-stranded β-sheets (shown in blue) interconnected by a loop structure. The structure is stabilized by three intrachain disulfide bridges arranged in the pattern Cys1–Cys3, Cys2–Cys4, Cys5–Cys6. It appears that the FN1+EGF-like double module, the two kringles, and the serine protease domain are involved in the interaction of tPA with fibrin [75, 76]. tPA binds with high affinity to fibrin, resulting in an enhanced activation of Pgn by tPA. Exposed C-terminal Lys and Arg residues in fibrin generated by proteolysis with Plm bind to the LBS in kringle 2 of tPA [77]. The 3-D structure of the catalytic domain of human tPA in complex with a low molecular weight (LMW) inhibitor (dansyl-EGR-chloromethyl ketone) was determined by X-ray diffraction (1RTF) and exhibits the expected trypsin-like fold (Fig. 7b) [78]. The inhibitor is covalently bound to His322 and Ser478 in the active site cleft of tPA located at the interface of the two subdomains. Lys429 forms a salt bridge with Asp477 promoting an active conformation in single-chain tPA. The single-chain, proenzyme form of tPA exhibits only a five to tenfold decreased activity compared with fully active, two-chain tPA [79]. Both forms seem to exhibit the same biological function.

Fig. 7.

a 3-D structure of the double module of human tPA comprising the fibronectin type I (FN1) domain and the epidermal growth factor-like (EGF-like) domain determined by NMR spectroscopy (1TPG, [74]). The disulfide bridges shown in yellow exhibit the following patterns: in FN1 (red) Cys1–Cys3, Cys2–Cys4, and in EGF-like (blue) Cys1–Cys3, Cys2–Cys4, Cys5–Cys6. b 3-D structure of the catalytic domain of human tPA in complex with the LMW inhibitor dansyl-EGR-chloromethyl ketone determined by X-ray diffraction (1BDA, [78]). The inhibitor shown in red is covalently bound to His322 and Ser478 in the active site cleft (magenta)

Interactions of tPA with endothelial cells and smooth muscle vascular cells lead to an increased activation of Pgn. In the case of endothelial cells, the Ca2+/phospholipid-binding protein annexin A2 (P07755) binds via its exposed C-terminal Lys and Arg residues to the kringle 2 domain of tPA [80, 81].

The main physiological inhibitors of tPA are PAI-1 and PAI-2, which are discussed in section Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 and Plasminogen activator inhibitor 2, respectively. An increased activity of tPA leads to hyperfibrinolysis (MIM 173370), an excessive bleeding disorder [82]. There are several forms of tPA in therapeutic use, among them alteplase (Activase, Genentech) and reteplase (Retavase, Centocor, and Roche), which are used to initiate fibrinolysis in the case of acute myocardial infarction, acute ischaemic stroke, and pulmonary embolism.

Urokinase-type plasminogen activator

Human uPA (P00749, EC 3.4.21.73; concentration in plasma 5–10 μg l−1) is synthesized in the lung and the kidney, but also in keratinocytes and endothelial cells [83, 84]. It is a single-chain multidomain glycoprotein (about 2% CHO) of 55 kDa (411 amino acids) [85, 86] containing one O-glycosylation site at Thr18 and one N-glycosylation site at Asn302 and two phosphorylation sites at Ser138 and Ser303 [87, 88]. The phosphorylation of Ser138/Ser303 seems to modulate the urokinase receptor (uPAR) transducing ability [88]. The uPA gene (PLAU, 6.4 kb) is located on chromosome 10q24 and is organized into 11 exons [89]. Human uPA is converted to its active, two-chain high molecular weight form held together by a single interchain disulfide bridge (Cys148–Cys279) upon cleavage of the Lys158 –Ile159 peptide bond by Plm, kallikrein, coagulation factor XIIa, or cathepsin [90]. The A-chain (157 amino acids) contains one EGF-like and one kringle domain and the B-chain (253 amino acids) comprises the serine protease part. In addition to the high molecular weight form, there is also a LMW form of uPA, the major form found in urine. The LMW form of uPA is generated by Plm or by uPA itself cleaving the Lys135–Lys136 peptide bond. Thus LMW uPA is devoid of the EGF-like and kringle domains, and the former A-chain consists only of a minichain (22 amino acids) linked to the catalytic domain by a single interchain disulfide bridge [91].

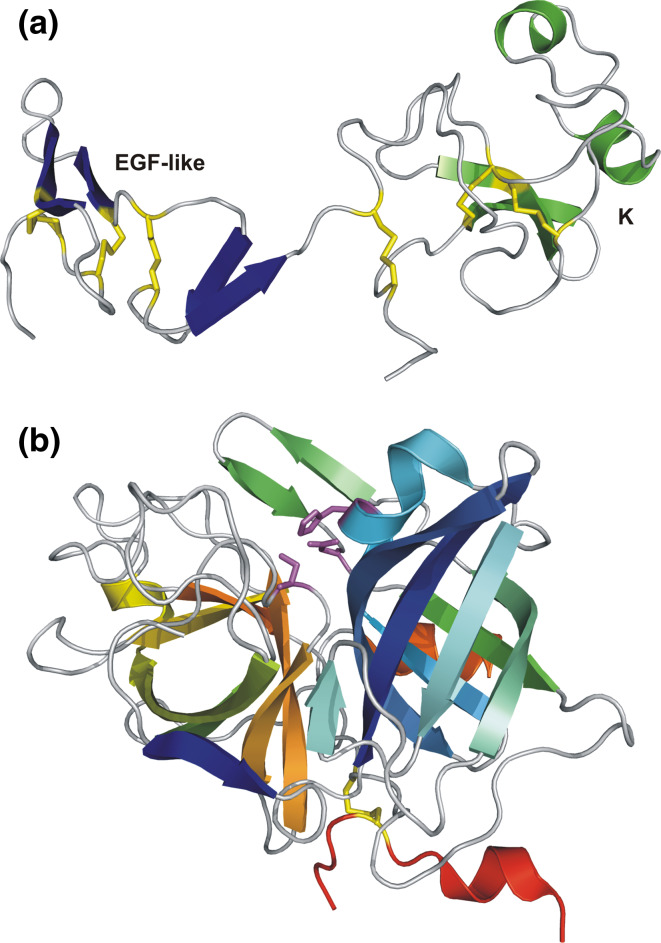

The 3-D structure of the double domain EGF-like+kringle determined by NMR spectroscopy (1URK) is shown in Fig. 8a [92]. The EGF-like module exhibits the same structural fold as the corresponding domain in tPA (Fig. 7a) and the kringle domain resembles the kringles in other kringle-containing proteins, e.g. human Pgn (Fig. 4). The kringle structure in uPA is devoid of an active LBS due to the replacement of essential residues in the cationic (Lys→Tyr) and anionic (Asp→Arg) centres and two aromatic residues in the hydrophobic groove of the LBS. Three consecutive Arg residues (Arg108–Arg110) and two His residues (His85 and His87) at the opposite ends of the kringle domain are involved in heparin binding [93, 94]. The EGF-like module mediates binding to its specific cellular receptor uPAR [95, 96]. The 3-D structure of human LMW uPA was determined by X-ray diffraction (1GJA) and is shown in Fig. 8b [97]. The serine protease part exhibits the expected trypsin-like fold with two subdomains each containing one antiparallel β-barrel and the active site cleft with the catalytic triad is located at the interface of the two subdomains. The minichain (in red) is linked to the catalytic domain by a single interchain disulfide bridge (in yellow).

Fig. 8.

a 3-D structure of the EGF-like (blue) and kringle (green) double domain of human uPA determined by NMR spectroscopy (1URK, [92]). The disulfide bridges are shown in yellow and are arranged as in Fig. 7a (EGF-like) and Fig. 4 (kringle). b 3-D structure of human LMW uPA determined by X-ray diffraction (1GJA, [96]). The minichain (red) is linked to the catalytic domain by a single interchain disulfide bridge (yellow)

The main physiological inhibitors of uPA are PAI-1 and PAI-2, which are discussed in section Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 and Plasminogen activator inhibitor 2, respectively. The uPA system consisting of the serine proteases Plm and uPA, the serpins A2PI, PAI-1, and PAI-2, and uPAR seems to play an important role in cancer metastasis [98]. uPA is available under the name Abbokinase (Abbott) and is used clinically in the treatment of thrombolytic disorders (pulmonary embolism).

Serine protease inhibitors (serpins) [99–102]

The regulation of proteolytic activity is a fundamental process in all living organisms. Serine protease inhibitors (serpins) are inhibitors (mass range 40–70 kDa) of serine proteases and more than 1,500 serpin-like genes have been identified so far in all three kingdoms of life as well as in viruses [101, 103, 104]. Serpins regulate very diverse physiological processes such as coagulation and fibrinolysis, complement activation, inflammation, angiogenesis, apoptosis, neoplasia, and viral pathogenesis.

Inhibitory serpins are different from other inhibitors in blood plasma in the sense that they are consumed in a one-to-one reaction known as ‘suicide inhibition’. The standard serpin structure is characterized by a conserved core structure usually built of three β-sheets (A, B, and C in red, green, and yellow, respectively), nine α-helices (hA–hI in grey), and the reactive centre loop (RCL in blue) containing the serine protease recognition site with the scissile peptide bond (P1–P1′). Serpins exist in different conformational states, some of which have been characterized in detail as can be seen in Fig. 9 [100]. The various conformational states carry characteristic features:

The native state: the native state is usually characterized by three β-sheets A, B, and C, nine α-helices hA–hI, and an RCL of approximately 20 amino acids located on the surface of the molecule.

The latent, inserted state: in the latent state the RCL is inserted into β-sheet A. This uncleaved, stressed state is metastable and is often compared with a spring under tension.

The cleaved state: in the cleaved state the stress is released, the scissile peptide bond P1–P1′ in the RCL is cleaved, and the N- and C-terminal ends of the cleaved peptide bond are now on either side of the molecule, often as far apart as 70 Å.

The serpin–serine protease complex: in the first step of the inhibition reaction a noncovalent Michaelis-like complex is formed between the serpin and the serine protease characterized by an interaction between the RCL of the serpin and the catalytic triad of the serine protease.

Cleaved serpin with inactivated serine protease: upon insertion of the RCL into β-sheet A the serine protease is drawn from one side of the serpin to the opposite side and the cleavage of the reactive peptide bond releases the tension. The serpin is now covalently linked to the side-chain of the serine residue in the catalytic triad of the serine protease.

Fig. 9.

Various conformational states of serpins [100]. a Native state of human α1-antitrypsin (1QLP). b Latent, inserted state of human antithrombin III (2ANT). c Cleaved state of human α1-antitrypsin (7API). d Noncovalent, Michaelis-like complex of alaserpin (from Manduca sexta) in complex with rat trypsin (1I99). e Cleaved serpin with inactivated serine protease of human α1-antitrypsin with bovine trypsin (1EZX)

The inhibition of a serine protease by a serpin is a two-stage process [105]:

The first step is a fast and reversible second-order reaction leading to a noncovalent 1:1 Michaelis-like complex of the serpin with the serine protease.

The second step is a slower and irreversible first-order reaction with the insertion of the RCL into β-sheet A and the subsequent cleavage of the reactive peptide bond P1–P1′ in the RCL, resulting in the covalent attachment of the serpin to the side-chain of the Ser residue in the catalytic triad of the serine protease.

Plasmin inhibitors

The main physiological inhibitor of Plm is the serpin A2PI which has unique N- and C-terminal extensions and as a consequence also has special biological properties. In addition, Plm activity is also regulated by the general protease inhibitor α2M.

α2-Antiplasmin or α2-plasmin inhibitor [106, 107]

Human A2PI, also termed α2-plasmin inhibitor (P08697; concentration in plasma: about 70 mg l−1), a member of the serpin superfamily, is a single-chain plasma glycoprotein (14% CHO) of about 67 kDa primarily synthesized in the liver [108, 109]. It contains four fully glycosylated N-glycosylation sites (Asn87, Asn250, Asn270, Asn277) [110, 111], a single disulfide bridge (Cys31–Cys104), two Cys residues (Cys64 and Cys113) of undefined state [112], and a sulfated Tyr residue (Tyr445) of unknown function [113]. The A2PI gene (SERPINF2, about 16 kb) is located on chromosome 17p13.3 and is organized into ten exons [114]. In human plasma, two N-terminally different forms are in circulation: (1) a form with 464 residues with Met as N-terminus (Met-A2PI), and (2) a form with 452 residues with Asn as N-terminus (Asn-A2PI) [115, 116]. Approximately 30% of mature A2PI circulates in human plasma in a C-terminally truncated form lacking at least 26 amino acids [117]. This truncated form inhibits Plm less rapidly than mature A2PI [118, 119]. The RCL contains the scissile peptide bond P1–P1′ at Arg364–Met365 [120]. So far, no 3-D structure of human A2PI is available. However, the 3-D structure of a N-terminally truncated form of murine A2PI (Q61247) sharing 71% sequence identity with human A2PI was determined by X-ray diffraction (2R9Y) [121]. As expected, murine A2PI exhibits the typical fold of the serpin core structure with three β-sheets and nine α-helices. However, the 3-D structures of the unique N- and C-terminal extensions of A2PI are still unsolved. In the N-terminal segment of A2PI Gln2 forms an isopeptide bond with Lys303 in the Aα chain of fibrin(ogen) catalysed by activated coagulation factor XIIIa [122, 123]. The unique C-terminal extension of A2PI (about 55 amino acids) containing the plasmin(ogen) binding site reveals a remarkable sequence identity between human and other species in the range 58–70%. The C-terminal extension of A2PI is characterized by four totally and two partially conserved Lys residues, of which the C-terminal Lys452 is most likely the main binding partner to the LBS in the Pgn kringle domains and Lys436 seems to exhibit a cooperative effect [32, 44]. In contrast, Wang et al. [33, 124] emphasized that Lys436 is the main binding partner and Lys452 has no significant influence on the binding to the LBS in the Pgn kringle domains.

A2PI is the main physiological inhibitor of Plm, the main component of the fibrinolytic system, but A2PI also inhibits chymotrypsin and trypsin. Kinetic data show a two-step reaction for the rapid inhibition of Plm: a reversible second order reaction (k1 about 3.8 ± 0.4 × 107 M−1s−1) followed by an irreversible first-order reaction (k2 about 4.2 ± 0.4 × 106 M−1s−1) [31, 125–128]. In the case of chymotrypsin the reactive bond in the RCL is moved one position further down to the C-terminus of A2PI, to Met365–Ser366, and the association constant (Ka) for inhibiting bovine chymotrypsin is 6.7 × 105 M−1s−1 [129].

Defects in the SERPINF2 gene result in A2PI deficiency (MIM 262850), an autosomal recessive disorder causing severe haemorrhagic diathesis, an unusual susceptibility to bleeding ([130, 131].

α2-Macroglobulin [132]

Human α2M (P01023; concentration in plasma about 1,200 mg l−1) is a member of the protease inhibitor I39 family. It is primarily synthesized in the liver [133]. The α2M gene (A2M, about 48 kb) is located on chromosome 12p13.3-p12.3 and consists of 36 exons in the range 21–229 bp [134]. Mature α2M is a large single-chain plasma glycoprotein (about 10% CHO) of 1,451 amino acids containing eight N-glycosylation sites at Asn32, Asn47, Asn224, Asn373, Asn387, Asn846, Asn968, and Asn1401 [135]. In plasma, α2M is present as a tetramer (about 720 kDa) composed of two noncovalently associated dimers oriented in an antiparallel fashion, and the two monomers in the dimers are held together covalently by two interchain disulfide bridges (Cys255–Cys408, Cys408–Cys255) [136]. Gln670 and Gln671 are potential crosslinking sites, with the side-chains of Lys residues in other proteins forming isopeptide bonds comparable to Gln2 in Asn-A2PI (see section α2-Antiplasmin or α2-plasmin inhibitor). Like the structurally related complement components C3 (P01024) and C4 (P0C0L4, P0C0L5), α2M contains a reactive isoglutamyl cysteine thioester bond Cys949–Gly–Glu–Gln952. α2M contains a ‘bait’ region of 39 amino acids (Pro667–Thr705) with three short inhibitory sequence segments (Arg681–Glu686, Arg696–Val700, Thr707–Phe712) [137].

α2M is a general inhibitor of all four types of proteases and acts as a scavenger. Limited proteolysis in the ‘bait’ region of α2M at specific cleavage sites by the active protease induces a large conformational change in α2M, resulting in the trapping of the protease in a large central cavity [135]. Concomitantly, the internal thioester bond is cleaved, which mediates the covalent binding of α2M to the protease. In the case of Plm, it appears that proteolysis and conformational changes in α2M are limited to one of the two subunits and the association constant Ka for Plm is 1.3 × 105 M−1s−1 [138].

α2M seems to be associated with Alzheimer disease (MIM 103950) and a deletion in exon 18 seems to be the cause of an increased risk of Alzheimer disease [139].

Plasminogen activator inhibitors

There are two main physiological plasminogen activator inhibitors, PAI-1 and PAI-2, which are more or less directly involved in the inhibition process of the main plasminogen activators, tPA and uPA. In addition, neuroserpin (predominantly expressed in the brain) mainly inhibits tPA, uPA, and Plm, whereas glia-derived nexin has a broader specificity, but also inhibits uPA and Plm.

Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1

Human PAI-1 (P05121; concentration in plasma about 20 μg l−1, variable) is a member of the serpin superfamily. It is produced by a variety of cells such as endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and liver cells [140]. PAI-1 is a single-chain plasma glycoprotein (13% CHO) of 50 kDa (379 amino acids) containing three N-glycosylation sites at Asn209, Asn265, and Asn329 (potential) [141]. The PAI-1 gene (SERPINE1, 12.2 kb) is located on chromosome 7q21.3-q22 and consists of nine exons [142]. The scissile peptide bond P1–P1′ is located at Arg346–Met347 [141, 143]. The 3-D structure of PAI-1 in complex with two inhibitory RCL pentapeptides (Ac-TVASS-NH2) was determined by X-ray diffraction (1A7C) and is shown in Fig. 10 [144]. The two pentapeptides (in blue) bind between the space of β-strands 3 and 5 in β-sheet A (in red). This prevents the insertion of the RCL into β-sheet A and as a consequence abolishes the inhibitory reaction with the target serine protease. This form of PAI-1 exhibits the typical structural features of cleaved serpins with the cleaved regions of the RCL on either side of the molecule (red circles) and the cleaved C-terminal region is shown in magenta.

Fig. 10.

3-D structure of human PAI-1 in complex with two inhibitory RCL pentapeptides (Ac-TVASS-NH2) determined by X-ray diffraction (1A7C, [144]). The two pentapeptides (blue) bind between β-strands 3 and 5 in β-sheet A (red). The cleaved C-terminal region is shown in magenta and the cleaved ends of the reactive peptide bond are located on either side of the molecule (red circles)

PAI-1 primarily inhibits tPA and uPA with second-order rate constants of 2.5–4 × 107 M−1s−1 for two-chain tPA and 1 × 107 M−1s−1 for uPA, thus regulating fibrinolysis by limiting the Plm production. In addition, PAI-1 also inhibits other serine proteases, but at much slower rates, e.g. thrombin (1.1 × 103 M−1s−1), Plm (6.6 × 105 M−1s−1, bovine PAI-1), trypsin (7 × 106 M−1s−1), and activated protein C [145–148]. PAI-1 is bound to vitronectin (P04004) in plasma and in the extracellular matrix [149]. Vitronectin and also heparin enhance the inhibition rate constant of PAI-1 for thrombin by a factor of up to 200-fold [150]. In the case of a vascular injury, activated platelets can increase the low plasma concentration of PAI-1 by a factor of 10 [151, 152].

Defects in the SERPINE1 gene are the cause of PAI-1 deficiency (MIM 173360), characterized by an abnormal bleeding tendency [153]. High levels of PAI-1 seem to be associated with myocardial infarction [154].

Plasminogen activator inhibitor 2 [155, 156]

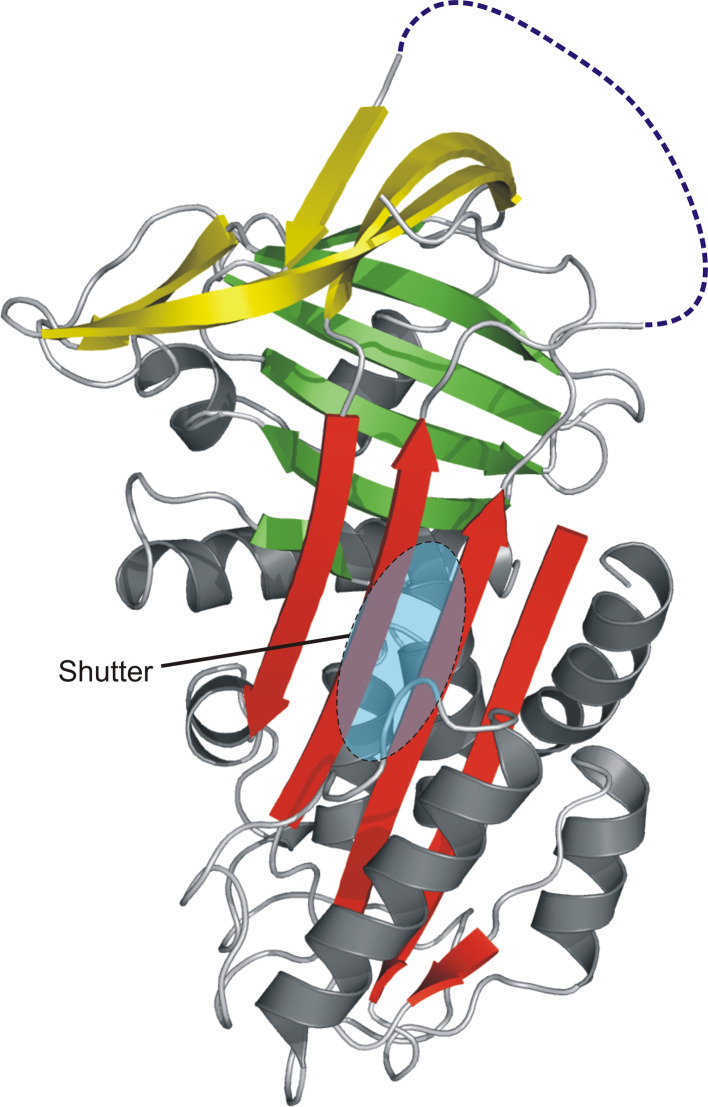

Human PAI-2 (P05120; concentration in plasma <5 μg l−1, only detectable during pregnancy [157]) is a member of the serpin superfamily. It is produced by epithelial cells, monocytes and macrophages, and keratinocytes [158–162]. Due to the lack of a proper signal sequence (it contains an inefficient internal signal sequence [163]) PAI-2 is not efficiently secreted and therefore accumulates intracellularly as a nonglycosylated 47-kDa protein [164]. A small portion of single-chain PAI-2 is secreted via a facultative translocation pathway [165] as a 60-kDa (415 amino acids) plasma glycoprotein containing three potential N-glycosylation sites at Asn75, Asn115, and Asn339, and one assigned disulfide bridge (Cys5–Cys405) [156]. The PAI-2 gene (SERPINB2, 16.4 kb) is located on chromosome 18q21.2-q22 and contains eight exons [166, 167]. The scissile peptide bond P1–P1′ is located at Arg380–Thr381 [168]. As Gln2 in A2PI, Gln83, Gln84, and Gln86 located in the C–D interhelical domain in PAI-2 (in other serpins corresponding to the C–D loop) can form isopeptide bonds with Lys residues in the Aα chain of fibrinogen, i.e. Lys148, Lys176, Lys183, Lys230, Lys413, and Lys457 catalysed by coagulation factor XIIIa [169, 170]. The 3-D structure of a deletion mutant (deletion of loop Asn66–Gln98) of PAI-2 was determined by X-ray diffraction (1BY7) and is shown in Fig. 11 [171]. This deletion mutant represents the stressed state of a serpin with a disordered structure of the RCL (the reconstructed RCL is represented as dashed, blue line). A buried cluster of polar amino acids beneath β-sheet A (in red), the so-called shutter region (indicated by a blue-shaded oval) stabilizes the stressed as well as the relaxed forms of serpins. As expected, the insertion of the RCL into β-sheet A is essential for the inhibition reaction.

Fig. 11.

3-D structure of a deletion mutant of human PAI-2 determined by X-ray diffraction (1BY7, [171]). The reconstructed RCL is shown as a dashed blue line and the shutter region located beneath β-sheet A (red) is shown as a blue-shaded oval

PAI-2 is an efficient inhibitor of tPA and uPA with second-order rate constants of 0.8–1.2 × 104 M−1s−1 for two-chain tPA and 2.4–2.7 × 106 M−1s−1 for uPA [172]. PAI-2 is only detectable in plasma during pregnancy and probably has a role in maintaining the placenta or in embryonic development [157]. As mentioned above, only a small portion of PAI-2 is secreted. Intracellular PAI-2 exhibits other functions than inhibition of uPA and tPA, e.g. PAI-2 influences cell proliferation and cell differentiation, inhibits apoptosis, and alters gene expression.

Little is known of precisely described diseases related to PAI-2 defects (MIM 173390).

Neuroserpin [173–175]

Neuroserpin (Q99574; usually not detectable in plasma) is a member of the serpin superfamily. It is predominantly expressed in the brain [176, 177]. Neuroserpin is a single-chain glycoprotein of 55 kDa (394 amino acids) containing three potential N-glycosylation sites at Asn141, Asn305, and Asn385 [178, 179]. The neuroserpin gene (SERPINI1, 89.8 kb) is located on chromosome 3q26.1 and consists of nine exons [176, 177]. The scissile peptide bond P1–P1′ is located at Arg346–Met347 [176]. The 3-D structure of uncleaved, native neuroserpin was determined by X-ray diffraction (3F5N, 3F02) and is shown in Fig. 12 [180]. It contains the expected elements of the core structure of serpins: three β-sheets (shown in red, green, and yellow), nine α-helices (in grey), and the exposed RCL (in blue).

Fig. 12.

3-D structure of uncleaved, native human neuroserpin determined by X-ray diffraction (3F5N, 3F02, [180]). Neuroserpin contains the typical structural elements of uncleaved, native serpins: three β-sheets (red, green, yellow), nine α-helices (grey), and the exposed RCL (blue)

tPA, uPA, and Plm have been identified as the main targets of neuroserpin activity [176, 180]. The corresponding association constants Ka for recombinant neuroserpin (chicken) are: (1) 1.5 ± 0.2 × 105 M−1s−1 (sc-tPA), (2) 4.7 ± 0.8 × 104 M−1s−1 (uPA), and (3) 1.1 ± 0.1 × 105 M−1s−1 (Plm) [181].

Neuroserpin seems to be involved in the formation and reorganization of synaptic connections and may be involved in the protection of neurons from cell damage by tPA. Defects in the SERPINI1 gene are the cause of familial encephalopathy characterized by neuroserpin inclusion bodies [177, 182].

Glia-derived nexin

Human glia-derived nexin (P07093) is a member of the serpin superfamily. It is synthesized by fibroblasts, heart muscle cells, and kidney epithelial cells, and also in the brain [183]. Glia-derived nexin is a single-chain plasma glycoprotein (about 6% CHO) of 43 kDa (379 amino acids) containing two potential N-glycosylation sites at Asn99 and Asn140 [184]. The scissile peptide bond P1–P1′ is located at Arg346–Ser347 [185]. The glia-derived nexin gene (SERPINE2) is located on chromosome 2q33-q35 containing nine exons [186, 187].

Glia-derived nexin has a broad specificity but it primarily inhibits trypsin, thrombin, uPA, and Plm. It seems to be the most important physiological regulator of α-thrombin in tissues [183]. The association constants Ka are: (1) 4.2 ± 0.4 × 106 M−1s−1 (trypsin), (2) 6.0 ± 1.3 × 105 M−1s−1 (thrombin), (3) 1.5 ± 0.1 × 105 M−1s−1 (uPA), and (4) 1.3 ± 0.1 × 105 M−1s−1 (Plm) [184, 185].

Diseases related to defects in the SERPINE2 gene are not very well understood (MIM 177010). However, the SERPINE2 gene seems to be associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [187].

Concluding remarks

The plasmin–antiplasmin system contains two main protein families, namely multidomain serine proteases represented by Pgn, tPA, and uPA, and serpins represented primarily by A2PI as well as PAI-1 and PAI-2. The data provide evidence that the noncatalytic domains in multidomain serine proteases such as kringles, FN1, or EGF-like domains mediate efficient binding to the target structures, facilitating an efficient cleavage reaction of the corresponding serine protease which is usually strictly limited to the intended site. Thus, the described multidomain serine proteases in the plasmin–antiplasmin system are well-adapted proteins which efficiently fulfil their tasks. The data provided show that the plasmin–antiplasmin system as a every complex system is tightly regulated by a series of physiological inhibitors, in this case primarily by serpins such as A2PI, PAI-1, and PAI-2. Also these inhibitors are very well adapted to their regulatory task.

Abbreviations

- A2PI

α2-Antiplasmin, α2-Plasmin inhibitor

- CHO

Carbohydrate

- EGF-like

Epidermal growth factor-like

- FN1

Fibronectin type I

- K

Kringle

- LBS

Lysine binding site

- LMW

Low molecular weight

- α2M

α2-Macroglobulin

- NTP

N-terminal peptide of Pgn

- PAI-1, -2

Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, 2

- Pgn

Plasminogen

- Plm

Plasmin

- RCL

Reactive centre loop

- Serpin

Serine protease inhibitor

- tPA

Tissue-type plasminogen activator

- uPA

Urokinase-type plasminogen activator

- uPAR

Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor

Footnotes

The recommended names in the UniProt Knowledgebase (SwissProt and TrEMBL) were used. The protein structures are based on the coordinates deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and were visualized as well as rendered using the software PyMOL. If not stated otherwise, the standard rainbow colour representation was used.

References

- 1.Schaller J, Gerber S, Kämpfer U, Lejon S, Trachsel C. Human blood plasma proteins: structure and function. Chichester: Wiley; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerber SS (2009) The human α2-plasmin inhibitor: functional characterization of the unique plasmin(ogen)-binding region. Inaugural dissertation, University of Bern, Switzerland

- 3.Waisman DM. Plasminogen: structure, activation, and regulation. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Syrovets T, Simmet T. Novel aspects and new roles of the serine protease plasmin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:873–885. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3348-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myöhänen H, Vaheri A. Regulation and interaction in the activation of cell-associated plasminogen. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:2840–2858. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4230-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castellino FJ, Ploplis VA. Structure and function of the plasminogen/plasmin system. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93:647–654. doi: 10.1160/TH04-12-0842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raum D, Marcus G, Alper CA, Levey R, Taylor PD, Starzl TE. Synthesis of human plasminogen by the liver. Science. 1980;208:1036–1037. doi: 10.1126/science.6990488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forsgren M, Råden B, Israelsson M, Larsson K, Hedén LO. Molecular cloning and characterization of a full-length cDNA clone for human plasminogen. FEBS Lett. 1987;213:254–260. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81501-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray JC, Buetow KH, Donovan M, Hornung S, Motulsky AG, Disteche C, Dyer K, Swisshelm K, Anderson J, Giblett E, Sadler E, Eddy R, Shows TB. Linkage disequilibrium of plasminogen polymorphisms and assignment of the gene to human chromosome 6q26–6q27. Am J Hum Genet. 1987;40:338–350. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petersen TE, Martzen MR, Ichinose A, Davie EW. Characterization of the gene for human plasminogen, a key proenzyme in the fibrinolytic system. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:6104–6111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ljinen HR, Hoylaerts M, Collen D. Isolation and characterization of a human plasma protein with affinity for the lysine binding sites in plasminogen. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:10214–10222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones AL, Hulett MD, Altin JG, Hogg P, Parish CR. Plasminogen is tethered with high affinity to the cell surface by the plasma protein, histidine-rich glycoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38267–38276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406027200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tordai H, Bányai L, Patthy L. The PAN module: the N-terminal domains of plasminogen and hepatocyte growth factor are homologous with the apple domains of the prekallikrein family and with a novel domain found in numerous nematode proteins. FEBS Lett. 1999;461:63–67. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01416-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sottrup-Jensen L, Claeys H, Zajdel M, Petersen TE, Magnusson S. The primary structure of human plasminogen: isolation of two lysine-binding fragments and one ‘mini-’ plasminogen (MW 38,000) by elastase-catalyzed-specific limited proteolysis. In: Davidson JF, Rowan RM, Samama MM, Desnoyers PC PC, editors. Progress in chemical fibrinolysis and thrombolysis, vol 3. New York: Raven Press; 1978. pp. 191–209. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Lin X, Loy JA, Tang J, Zhang XC. Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of human plasmin complexed with streptokinase. Science. 1998;281:1662–1665. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayes ML, Castellino FJ. Carbohydrate of the human plasminogen variants. I. Carbohydrate composition, glycopeptide isolation, and characterization. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:8768–8771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayes ML, Castellino FJ. Carbohydrate of the human plasminogen variants II. Structure of the asparagine-linked oligosaccharide unit. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:8772–8776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayes ML, Castellino FJ. Carbohydrate of the human plasminogen variants. III. Structure of the O-glycosidically linked oligosaccharide unit. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:8777–8780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marti T, Schaller J, Rickli EE, Schmid K, Kamerling JP, Gerwig GJ, van Halbeek H, Vliegenthart JFG. The N- and O-linked carbohydrate chains of human, bovine and porcine plasminogen. Species specificity in relation to sialylation and fucosylation patterns. Eur J Biochem. 1988;173:57–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pirie-Sheperd SR, Stevens RD, Andon NL, Enghild JJ, Pizzo SV. Evidence for a novel O-linked sialylated trisaccharide on Ser-248 of human plasminogen 2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7408–7411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H, Prorok M, Bretthauer RK, Castellino FJ. Serine-578 is a major phosphorylation locus in human plasma plasminogen. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8100–8116. doi: 10.1021/bi970328d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Violand BN, Castellino FJ. Mechanism of the urokinase-catalyzed activation of human plasminogen. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:3906–3912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danø K, Andreasen PA, Grøndahl-Hansen J, Kristensen P, Nielsen LS, Skriver L. Plasminogen activators, tissue degradation, and cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 1985;44:139–266. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(08)60028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robbins KC, Summaria L, Hsieh B, Shah RJ. The peptide chains of human plasmin. Mechanism of activation of human plasminogen to plasmin. J Biol Chem. 1967;242:2333–2342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X, Terzyan S, Tang J, Loy JA, Lin X, Zhang XC. Human plasminogen catalytic domain undergoes an unusual conformational change upon activation. J Mol Biol. 2000;295:903–914. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schick LA, Castellino FJ. Direct evidence for the generation of an active site in the plasminogen moiety of the streptokinase-human plasminogen activator complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1974;57:47–54. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(74)80355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kowalska-Loth B, Zakrzewski K. The activation by staphylokinase of human plasminogen. Acta Biochim Pol. 1975;22:327–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramesh V, Petros AM, Llinás M, Tulinsky A, Park CH. Proton magnetic resonance study of lysine-binding to the kringle 4 domain of human plasminogen. The structure of the binding site. J Mol Biol. 1987;198:481–498. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90295-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mathews II, Vanderhoff-Hanavar P, Castellino FJ, Tulinsky A. Crystal structures of the recombinant kringle 1 domain of human plasminogen in complexes with the ligands epsilon-aminocaproic acid and trans-4-(aminomethyl)cyclohexane-1-carboxylic acid. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2567–2576. doi: 10.1021/bi9521351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suenson E, Thorsen S. Secondary-site binding of glu-plasmin, lys-plasmin and miniplasmin to fibrin. Biochem J. 1981;197:619–628. doi: 10.1042/bj1970619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiman B, Lijnen HR, Collen D. On the specific interaction between the lysine-binding sites in plasmin and complementary sites in alpha2-antiplasmin and in fibrinogen. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;579:142–154. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(79)90094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frank PS, Douglas JT, Locher M, Llinás M, Schaller J. Structural/functional characterization of the α2-plasmin inhibitor C-terminal peptide. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1078–1085. doi: 10.1021/bi026917n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang H, Yu A, Wiman B, Pap S. Identification of amino acids in antiplasmin involved in its noncovalent ‘lysine-binding-site’-dependent interaction with plasmin. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:2023–2029. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ponting CP, Marshall JM, Cederhoilm Williams SA. Plasminogen: a structural review. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1992;3:605–614. doi: 10.1097/00001721-199210000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berg A, Sjöbring U. PAM, a novel plasminogen-binding protein from Streptococcus pyogenes. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:25417–25424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carlsson Wistedt A, Kotarsky H, Marti D, Ringdahl U, Castellino FJ, Schaller J, Sjöbring U. Kringle 2 mediates high affinity binding of plasminogen to an internal sequence in streptococcal surface protein PAM. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24420–24424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miles LA, Dahlberg CM, Plow EF. The cell binding domains of plasminogen and their function plasma. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:11928–11934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marti D, Schaller J, Ochensberger B, Rickli EE. Expression, purification and characterization of the recombinant kringle 2 and kringle 3 domains of human plasminogen and analysis of their binding affinities for ω-aminocarboxylic acids. Eur J Biochem. 1994;219:455–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb19959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Söhndel S, Hu C-K, Marti D, Affolter M, Schaller J, Llinås M, Rickli EE. Recombinant gene expression and 1H NMR characteristics of the kringle (2 + 3) supermodule: spectroscopic/functional individuality of plasminogen kringle domains. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2357–2364. doi: 10.1021/bi9520949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bürgin J, Schaller J. Expression, isolation and characterization of a mutated human plasminogen kringle 3 with a functional lysine binding site. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:135–141. doi: 10.1007/s000180050278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marti DN, Hu C-K, An SSA, von Haller P, Schaller J, Llinás M. Ligand preferences of kringle 2 and homologous domains of human plasminogen: canvassing weak, intermediate, and high-affinity binding sites by 1H-NMR. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11591–11604. doi: 10.1021/bi971316v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marti DN, Schaller J, Llinás M. Solution structure and dynamics of the plasminogen kringle-2-AMCHA complex: 3(1)-helix in homologous domains. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15741–15755. doi: 10.1021/bi9917378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang Y, Mochalkin I, McCance SG, Chen B, Tulinsky A, Castellino FJ. Structure and ligand binding determinants of the recombinant kringle 5 domain of human plasminogen. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3258–3271. doi: 10.1021/bi972284e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerber SS, Lejon S, Locher M, Schaller J. The human α2-plasmin inhibitor: functional characterization of the unique plasmin(ogen)-binding region. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:1505–1518. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0264-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tranqui L, Prandini M-H, Chapel A. The structure of plasminogen studied by electron microscopy. Biol Cellul. 1979;34:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weisel JW, Nagaswami C, Korsholm B, Petersen LC, Suenson E. Interactions of plasminogen with polymerizing fibrin and its derivatives, monitored with a photoaffinity cross-linker and electron microscopy. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:1117–1135. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abad MC, Arni RK, Grella DK, Castellino FJ, Tulinsky A, Geiger JH. The x-ray crystallographic structure of the angiogenesis inhibitor angiostatin. J Mol Biol. 2002;318:1009–1017. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walker JB, Nesheim ME. The molecular weights, mass distribution, chain composition, and structure of soluble fibrin degradation products released from a fibrin clot perfused with plasmin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5201–5212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.5201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mak TW, Rutledge G, Sutherland DJ. Androgen-dependent fibrinolytic activity in a murine mammary carcinoma (Shionogi SC-115 cells) in vitro. Cell. 1976;7:223–226. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strickland S, Reich E, Sherman MI. Plasminogen activator in early embryogenesis: enzyme production by trophoblast and parietal endoderm. Cell. 1976;9:231–240. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gross JL, Moscatelli D, Rifkin DB. Increased capillary endothelial cell protease activity in response to angiogenic stimuli in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:2623–2627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.9.2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ossowski L, Reich E. Antibodies to plasminogen activator inhibit human tumor metastasis. Cell. 1983;35:611–619. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nielsen LS, Kellerman GM, Behrendt N, Picone R, Danø K, Blasi F. A 55,000–60,000 Mr receptor protein for urokinase-type plasminogen activator. Identification in human tumor cell lines and partial purification. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:2358–2363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schäfer BM, Maier K, Eickhoff U, Todd RF, Kramer MD. Plasminogen activation in healing human wounds. Am J Pathol. 1994;144:1269–1280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Netzel-Arnett S, Mitola DJ, Yamada SS, Chrysovergis K, Holmbeck K, Birkedal-Hansen H, Bugge TH. Collagen dissolution by keratinocytes requires cell surface plasminogen activation and matrix metalloproteinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45154–45161. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206354200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bonnefoy A, Legrand C. Proteolysis of subendothelial adhesive glycoproteins (fibronectin, thrombospondin, and von Willebrand factor) by plasmin, leukocyte cathepsin G, and elastase. Thromb Res. 2000;98:323–332. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(99)00242-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakagami Y, Abe K, Nishiyama N, Matsuki N. Laminin degradation by plasmin regulates long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2003–2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-02003.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zeibdawi AR, Pryzdial EL. Mechanism of factor Va inactivation by plasmin. Loss of A2 and A3 domains from a Ca2+-dependent complex of fragments bound to phospholipid. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19929–19936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004711200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hamilton KK, Fretto LJ, Grierson DS, McKee PA. Effects of plasmin on von Willebrand factor multimers. Degradation in vitro and stimulation of release in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:261–270. doi: 10.1172/JCI111956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seligsohn U, Lubetsky A. Genetic susceptibility to venous thrombosis. New Engl J Med. 2001;344:1222–1231. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104193441607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ichinose A, Espling ES, Takamatsu J, Saito H, Shinmyozu K, Maruyama I, Petersen TE, Davie EW. Two types of abnormal genes for plasminogen in families with a predisposition for thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:115–119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schuster V, Seregard S. Ligneous conjunctivitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:369–388. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6257(03)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Levin EG. Latent tissue plasminogen activator produced by human endothelial cells in culture: evidence for an enzyme-inhibitor complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:6804–6808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.22.6804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sappino A-P, Madani R, Huarte J, Belin D, Kiss JZ, Wohlwend A, Vassalli J-D. Extracellular proteolysis in the adult murine brain. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:679–685. doi: 10.1172/JCI116637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pfeiffer G, Schmidt M, Strube K-H, Geyer R. Carbohydrate structure of recombinant human uterine tissue plasminogen activator expressed in mouse epithelial cells. Eur J Biochem. 1989;186:273–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harris RJ, Leonard CK, Guzzetta AW, Spellman MW. Tissue plasminogen activator has an O-linked fucose attached to threoine-61 in the epidermal growth factor domain. Biochemistry. 1991;30:2311–2314. doi: 10.1021/bi00223a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pennica D, Holmes WE, Kohr WJ, Harkins RN, Vehar GA, Ward CA, Bennett WF, Yelverton E, Seeburg PH, Heyneker HL, Goeddel DV, Collen D. Cloning and expression of human tissue-type plasminogen activator cDNA in E. coli. Nature. 1983;301:214–221. doi: 10.1038/301214a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ny T, Elgh F, Lund B. The structure of the human tissue-type plasminogen activator gene: correlation of introns and exon structures to functional and structural domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:5355–5359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.17.5355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fisher R, Waller EK, Grossi G, Thompson D, Tizard R, Schleuning W-D. Isolation and characterization of the human tissue-type plasminogen activator structural gene including its 5’ flanking region. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:11223–11230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Loscalzo J. Structural and kinetic comparison of recombinant human single- and two-chain tissue plasminogen activator. J Clin Invest. 1988;82:1391–1397. doi: 10.1172/JCI113743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Collen D, Lijnen HR. Basic and clinical aspects of fibrinolysis and thrombolysis. Blood. 1991;78:3114–3124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Byeon IJ, Llinás M. Solution structure of the tissue-type plasminogen activator kringle 2 domain complexed to 6-aminohexanoic acid, an antifibrinolytic drug. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:1035–1051. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90592-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.de Vos AM, Ultsch MH, Kelley RF, Padmanabhan K, Tulinsky A, Westbrook ML, Kossiakoff AA. Crystal structure of the kringle 2 domain of tissue plasminogen activator at 2.4 Å resolution. Biochemistry. 1992;31:270–279. doi: 10.1021/bi00116a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smith BO, Downing AK, Driscoll PC, Dudgeon TJ, Campbell ID. The solution structure and backbone dynamics of the fibronectin type I and epidermal growth factor-like pair of modules of tissue-type plasminogen activator. Structure. 1995;3:823–833. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bennett WF, Paoni NF, Keyt BA, Botstein D, Jones AJ, Presta L, Wurm FM, Zoller MJ. High resolution analysis of functional determinants on human tissue-type plasminogen activator. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:5191–5201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.de Vries C, Vaerman H, Pannekoeck H. Identification of the domains of tissue-type plasminogen activator involved in the augmented binding to fibrin after limited digestion with plasmin. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:12604–12610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hoylaerts M, Rijken DC, Lijnen HR, Collen D. Kinetics of the activation of plasminogen by human tissue plasminogen activator. Role of fibrin. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:2912–2919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lamba D, Bauer M, Huber R, Fischer S, Rudolph R, Kohnert U, Bode W. The 2.3 Å crystal structure of the catalytic domain of recombinant two-chain human tissue-type plasminogen activator. J Mol Biol. 1996;258:117–135. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Renatus M, Engh RA, Stubbs MT, Huber R, Fischer S, Kohnert U, Bode W. Lysine 156 promotes the anomalous proenzyme activity of tPA: X-ray crystal structure of single-chain human tPA. EMBO J. 1997;16:4797–4805. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.4797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hajjar KA, Jacovina AT, Chacko J. An endothelial cell receptor for plasminogen/tissue plasminogen activator I. Identity with annexin II. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21191–21197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cesarman GM, Guevara CA, Hajjar KA. An endothelial cell receptor for plasminogen/tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) II. Annexin-II mediated enhancement of t-PA-dependent plasminogen activation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21198–21203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hunt BJ, Segal H. Hyperfibrinolysis. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49:958. doi: 10.1136/jcp.49.12.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bernik MB, Kwaan HC. Plasminogen activator activity in cultures from human tissues. An immunological and histochemical study. J Clin Invest. 1969;48:1740–1753. doi: 10.1172/JCI106140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Duffy MJ. Plasminogen activators and cancer. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1990;1:681–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nielsen LS, Hansen JG, Skriver L, Wilson EL, Kaltoft K, Zeuthen J, Danø K. Purification of zymogen to plasminogen activator from human glioblastoma cells by affinity chromatography with monoclonal antibody. Biochemistry. 1982;21:6410–6415. doi: 10.1021/bi00268a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wun TC, Ossowski L, Reich E. A proenzyme form of human urokinase. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:7262–7268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Buko AM, Kentzer EJ, Petros A, Menon G, Zuiderweg ERP, Sarin VK. Characterization of posttranslational fucosylation in the growth factor domain of urinary plasminogen activator. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:3992–3996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Franco P, Iaccarino C, Chiaradonna F, Brandazza A, Iavarone C, Mastronicola MR, Nolli ML, Stoppelli MP. Phosphorylation of human pro-urokinase on Ser138/303 impairs its receptor-dependent ability to promote myelomonocytic adherence and motility. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:779–791. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.3.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Riccio A, Grimaldi G, Verde P, Sebastio G, Boast S, Blasi F. The human urokinase-plasminogen activator gene and its promotor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:2759–2771. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.8.2759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kobayashi H, Schmitt M, Goretzki L, Chucholowski N, Calvete J, Kramer M, Günzler WA, Jänicke F, Graeff H. Cathepsin B efficiently activates the soluble and the tumor cell receptor-bound form of the proenzyme urokinase-type plasminogen activator (Pro-uPA) J Biol Chem. 1991;266:5147–5152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Steffens GJ, Günzler WA, Otting F, Frankus E, Flohe L. The complete amino acid sequence of low molecular mass urokinase from human urine. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1982;363:1043–1058. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1982.363.2.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hansen AP, Petros AM, Meadows RP, Nettesheim DG, Mazar AP, Olejniczak ET, Xu RX, Pederson TM, Henkin J, Fesik SW. Solution structure of the amino-terminal fragment of urokinase-type plasminogen activator. Biochemistry. 1994;33:4847–4864. doi: 10.1021/bi00182a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stephens RW, Bokman AM, Myohanen HT, Reisberg T, Tapiovaara H, Pedersen N, Grøndahl-Hansen J, Llinás M, Vaheri A. Heparin binding to the urokinase kringle domain. Biochemistry. 1992;31:7572–7579. doi: 10.1021/bi00148a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Li X, Bokman AM, Llinás M, Smith RA, Dobson CM. Solution structure of the kringle domain from urokinase-type plasminogen activator. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:1548–1559. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Appella E, Robinson EA, Ulrich SJ, Stoppelli MP, Corti A, Cassani G, Blasi F. The receptor-binding sequence of urokinase. A biological function for the growth-factor module of proteases. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:4437–4440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ploug M, Rahbek-Nielsen H, Ellis V, Roepstorff P, Danø K. Chemical modification of the urokinase-type plasminogen activator and its receptor using tetranitromethane. Evidence for the involvement of specific tyrosine residues in both molecules during receptor-ligand interaction. Biochemistry. 1995;34:12524–12534. doi: 10.1021/bi00039a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Katz BA, Sprengeler PA, Luong C, Verner E, Elrod K, Kritley M, Janc J, Spencer JR, Breitenbucher JG, Hui H, McGee D, Allen D, Martelli A, Mackman RL. Engineering inhibitors highly selective for the S1 sites of Ser190 trypsin-like serine protease drug targets. Chem Biol. 2001;8:1107–1121. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(01)00084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Andreasen PA, Kjøller L, Christensen L, Duffy MJ. The urokinase-type plasminogen activator system in cancer metastasis: a review. Int J Cancer. 1997;72:1–22. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970703)72:1<1::AID-IJC1>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Janciauskiene S. Conformational properties of serine proteinase inhibitors (serpins) confer multiple pathophysiological roles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1535:221–235. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(01)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Silverman GA, Bird PI, Carrell RW, Church FC, Coughlin PB, Gettins PGW, Irving IA, Lomas DA, Luke CJ, Moyer RW, Pemberton PA, Remold-O’Donnell E, Salvesen GS, Travis J, Whisstock JC. The serpins are an expanding superfamily of structurally similar but functionally diverse proteins. Evolution, mechanism of inhibition, novel functions, and a revised nomenclature. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33293–33296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Law RH, Zhang Q, McGowan S, Buckle AM, Silverman GA, Wong W, Rosado CJ, Langendorf CG, Pike RN, Bird PI, Whisstock JC. An overview of the serpin superfamily. Genome Biol. 2006;7:216–226. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-5-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gettins PG, Olson ST. Exosite determinants of serpin specificity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:20441–20445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800064200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Irving JA, Pike RN, Lesk AM, Whisstock JC. Phylogeny of the serpin superfamily: implications of patterns of amino acid conservation for structure and function. Genome Res. 2000;10:845–864. doi: 10.1101/gr.GR-1478R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.van Gent D, Sharp P, Morgan K, Kalsheker N. Serpins: structure, function and molecular evolution. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35:1536–1547. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(03)00134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gettins PG. Keeping the serpin machine running smoothly. Genome Res. 2000;10:1833–1835. doi: 10.1101/gr.168900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Coughlin PB. Antiplasmin: the forgotten serpin? FEBS J. 2005;272:4852–4857. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Favier R, Aoki N, de Moerloose P. Congenital α2-plasmin inhibitor deficiencies: a review. Br J Haematol. 2001;114:4–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Saito H, Goodnough LT, Knowles BB, Aden DP. Synthesis and secretion of α2-plasmin inhibitor by established human liver cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:5684–5687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.18.5684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sumi Y, Ichikawa Y, Nakamura Y, Miura O, Aoki N. Expression and characterization of pro α2-plasmin inhibitor. J Biochem. 1989;106:703–707. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ries M, Easton RL, Longstaff C, Zenker M, Morris HR, Dell A, Gaffney PJ. Differences between neonates and adults in carbohydrate sequences and reaction kinetics of plasmin and α2-antiplasmin. Thromb Res. 2002;105:247–256. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(02)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Locher M (2004) Strukturelle und funktionelle Untersuchungen am α2-Plasmininhibitor. Inaugural dissertation, University of Bern, Switzerland

- 112.Christensen S, Valnickova Z, Thøgersen IB, Olsen EH, Enghild JJ. Assignment of a single disulphide bridge in human alpha2-antiplasmin: implications for the structural and functional properties. Biochem J. 1997;323:847–852. doi: 10.1042/bj3230847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hortin G, Fok KF, Toren PC, Strauss AW. Sulfation of a tyrosine residue in the plasmin-binding domain of α2-antiplasmin. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:3082–3085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hirosawa S, Nakamura Y, Miura O, Sumi Y, Aoki N. Organization of the human alpha 2-plasmin inhibitor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:6836–6840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Koyama T, Koike Y, Toyota S, Miyagi F, Suzuki N, Aoki N. Different NH2-terminal form with 12 additional residues of α2-plasmin inhibitor from human plasma and culture media of Hep G2 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;200:417–422. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lee KN, Jackson KW, Christiansen VJ, Chung KH, McKee PA. A novel plasma proteinase potentiates α2-antiplasmin inhibition of fibrin digestion. Blood. 2004;103:3783–3788. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sasaki T, Morita T, Iwanaga S. Identification of the plasminogen-binding site of human alpha 2-plasmin inhibitor. J Biochem. 1986;99:1699–1705. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Clemmensen I, Thorsen S, Müllertz S, Petersen LC. Properties of three different molecular forms of the α2plasmin inhibitor. Eur J Biochem. 1981;120:105–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb05675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kluft C, Los P, Jie AF, van Hinsbergh VW, Vellenga E, Jespersen J, Henny CP. The mutual relationship between the two molecular forms of the major fibrinolysis inhibitor alpha-2-antiplasmin in blood. Blood. 1986;67:616–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Holmes WE, Nelles L, Lijnen HR, Collen D. Primary structure of human α2-antiplasmin, a serine protease inhibitor (serpin) J Biol Chem. 1987;262:1659–1664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Law RH, Sofian T, Kan WT, Horvath AJ, Hitchen CR, Langendorf CG, Buckle AM, Whisstock JC, Coughlin PB. X-ray crystal structure of the fibrinolysis inhibitor alpha2-antiplasmin. Blood. 2008;111:2049–2052. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-114215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sakata Y, Aoki N. Significance of cross-linking of α2-plasmin inhibitor to fibrin in inhibition of fibrinolysis and in hemostasis. J Clin Invest. 1982;69:536–542. doi: 10.1172/JCI110479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kimura S, Aoki N. Cross-linking site in fibrinogen for α2-plasmin inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:15591–15595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wang H, Karlsson A, Sjöström I, Wiman B. The interaction between plasminogen and antiplasmin variants as studied by surface plasmon resonance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1764:1730–1734. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Christensen U, Clemmensen I. Kinetic properties of the primary inhibitor of plasmin from human plasma. Biochem J. 1977;163:389–391. doi: 10.1042/bj1630389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wiman B, Collen D. On the kinetics of the reaction between human antiplasmin and plasmin. Eur J Biochem. 1978;84:573–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wiman B, Collen D. On the mechanism of the reaction between human alpha 2-antiplasmin and plasmin. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:9291–9297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Wiman B, Boman L, Collen D. On the kinetics of the reaction between human antiplasmin and a low-molecular-weight form of plasmin. Eur J Biochem. 1978;87:143–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Potempa J, Shieh B-H, Travis J. Alpha-2-antiplasmin: a serpin with two separate but overlapping reactive sites. Science. 1988;241:699–700. doi: 10.1126/science.2456616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Miura O, Hirosawa S, Kato A, Aoki N. Molecular basis for congenital deficiency of alpha-2-plasmin inhibitor: a frameshift mutation leading to elongation of the deduced amino acid sequence. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1598–1604. doi: 10.1172/JCI114057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Lind B, Thorsen S. A novel missense mutation in the human plasmin inhibitor (alpha-2-antiplasmin) gene associated with a bleeding tendency. Br J Haematol. 1999;107:317–322. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sottrup-Jensen L. α-Macroglobulins: structure, shape, and mechanisms of proteinase complex formation. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:11539–11542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Borth W. α2-Macroglobulin, a multifunctional binding protein with targeting characteristics. FASEB J. 1992;6:3345–3353. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.15.1281457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Matthijs G, Devriendt K, Cassiman J-J, van den Berghe H, Marynen P. Structure of the human alpha-2-macroglobulin gene and its promotor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;184:596–603. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(92)90631-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sottrup-Jensen L, Stepanik TM, Kristensen T, Wierzbicki DM, Jones CM, Lønblad PB, Magnusson S, Petersen TE. Primary structure of human alpha-2-macroglobulin V. The complete structure. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:8318–8327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Jensen PE, Sottrup-Jensen L. Primary structure of human alpha-2-macroglobulin. Complete disulfide bridge assignment and localization of two interchain bridges in the dimeric proteinase binding unit. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:15863–15869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Sottrup-Jensen L, Lønblad PB, Stepanik TM, Petersen TE, Magnusson S, Jörnvall H. Primary structure of the ‘bait’ region for proteinases in α2-macroglobulin. FEBS Lett. 1981;127:167–173. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(81)80197-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Steiner JP, Migliorini M, Strickland DK. Characterization of the reaction of plasmin with α2-macroglobulin: Effect of antifibrinolytic agents. Biochemistry. 1987;26:8487–8495. doi: 10.1021/bi00399a068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Blacker D, Wilcox MA, Laird NM, Rodes L, Horvath SM, Go RCP, Perry R, Watson B, Jr, Bassett SS, McInnis MG, Albert MS, Hyman BT, Tanzi RE. Alpha-2 macroglobulin is genetically associated with Alzheimer disease. Nat Genet. 1998;19:357–360. doi: 10.1038/1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Alessi MC, Peiretti F, Morange P, Henry M, Nalbone G, Juhan-Vague I. Production of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 by human adipose tissue: possible link between visceral fat accumulation and vascular disease. Diabetes. 1997;46:860–867. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.46.5.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]