Abstract

Apoptotic cell (AC)-derived factors alter the physiology of macrophages (MΦs) towards a regulatory phenotype, characterized by reduced nitric oxide (NO) production. Impaired NO formation in response to AC-conditioned medium (CM) was facilitated by arginase II (ARG II) expression, which competes with inducible NO synthase for l-arginine. Here we explored signaling pathways allowing CM to upregulate ARG II in RAW264.7 MΦs. Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) was required and acted synergistically with a so far unidentified factor to elicit high ARG II expression. S1P activated S1P2, since S1P2 knockdown prevented ARG II upregulation. Furthermore, ERK5 knockdown attenuated CM-mediated ARG II protein induction. CREB was implicated as shown by EMSA analysis and decoy-oligonucleotides scavenging CREB in RAW264.7 MΦs, which blocked ARG II expression. We conclude that AC-derived S1P binds to S1P2 and acts synergistically with other factors to activate ERK5 and concomitantly CREB. This signaling cascade shapes an anti-inflammatory MΦ phenotype by ARG II induction.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00018-010-0537-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Macrophage polarization, Apoptotic cells, Lipid mediators, S1P2, Signal transduction

Introduction

Macrophages (MΦs) are versatile immune cells that, depending on environmental signals, acquire diverse functional states. As professional phagocytes, MΦs engulf apoptotic cells (ACs) to prevent them from undergoing secondary necrosis, thereby protecting the surrounding tissue from being exposed to inflammatory constituents. Moreover, ACs induce MΦ polarization towards an anti-inflammatory, regulatory phenotype [1]. Recently, we demonstrated that arginase II (ARG II) upregulation attenuated nitric oxide (NO) production in RAW264.7 MΦs exposed to apoptotic Jurkat cells or apoptotic Jurkat cell-derived mediators. This effect was also recapitulated in human MΦ-like THP-1 cells [2]. ARG II competes with inducible NO synthase for the common substrate l-arginine [3]. This finding corroborated other studies reporting modulation of NO production in MΦs by ARG II [4, 5].

There are two arginase (ARG) isoforms in mammals [3], which catalyze the hydrolysis of l-arginine to l-ornithine and urea. Although their amino acid sequences are 58% identical and their enzymatic properties are similar, transcriptional regulation as well as their tissue, cellular and subcellular distributions is different. In hepatocytes ARG I is mainly expressed in the cytosol and catalyzes the last step of urea synthesis. In contrast, ARG II is located in mitochondria and has wide tissue distribution, with expression in kidney, brain, small intestine and in MΦs [6–8]. Because of its close proximity to ornithine aminotransferase in mitochondria, ARG II is considered to be primarily involved in the production of ornithine as a precursor of proline [3]. Even though the two ARG isoforms mostly occur individually, some cell types like MΦs express both of them [9].

ARG II has been tied to a series of vascular diseases including asthma and hypertension [10, 11], since these pathophysiological conditions result from arginase-mediated impaired NO production. Furthermore, there is accumulating evidence for a role of ARG II in tumor biology, as it is highly expressed in kidney, lung, breast and prostate cancer cells [12–15]. ARG II metabolizes l-arginine, thereby supplying the tumor with l-ornithine needed for its rapid growth, at the same time inducing T-cell dysfunction [14]. Based on these findings, ARG II seems to be a promising therapeutical target and thus understanding molecular pathways of its regulation is necessary. It was previously described that ARG II can be induced by interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3), cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or interleukin 10 (IL-10)/isoproterenol [8, 9, 16, 17]. Marathe et al. reported that in MΦs ARG II is a direct target of liver X receptor (LXR), a transcription factor mediating anti-inflammatory actions [18]. Considering this rudimentary information, we characterized the signaling pathway used by AC-derived mediators to upregulate ARG II in MΦs.

Materials and methods

Materials

Staurosporine, proteinase K, NVP231, NS398, anti-actin and anti-α-tubulin antibodies (Abs) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). n-Oleoyl-ethanolamine (NOE), GW4896 and the Janus kinase (Jak) inhibitor I were purchased from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany). U0126, PD98059, SB203580 and LY294002 were ordered from Alexis Biochemical (Lörrach, Germany). S1P came from Avanti (Alabaster, AL). JTE013 was from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Cell culture supplements and FCS were ordered from PAA Laboratories (Cölbe, Germany). Oligonucleotides were bought from Biomers (Ulm, Germany). CREB decoy oligonucleotides (wt and mutated) were ordered from Metabion (Martinsried, Germany). Restriction enzymes (BglII, EcoRV, HindIII, SmaI) were purchased from New England Biolabs (Frankfurt am Main, Germany). Anti-ARG II, anti-CREB-1 and anti-S1P2 (EDG-5) Abs came from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-ERK1/2 and anti-ERK5 Abs were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). The monoclonal anti-HA.11 Ab was provided by Covance (Emeryville, CA). The anti-FLAG Ab was obtained from Rockland (Gilbertsville, PA). The siGENOME SMARTpool siRNA against ERK5, S1P2 and siControl nontargeting siRNA were from Dharmacon RNAi Technologies (Bonn, Germany). All chemicals were of the highest grade of purity and commercially available.

Cell culture

The mouse monocyte/macrophage cell line RAW264.7, the human Jurkat T cell line and the human MCF-7 breast carcinoma cell line were maintained in RPMI 1640. Human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) high glucose. Each medium was supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 10% heat-inactivated FCS. All cell lines were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were regularly tested to be mycoplasma free.

Generation of apoptotic Jurkat and MCF-7 cells

MCF-7 or Jurkat cells were treated for 2.5 h with 0.5 μg/ml staurosporine in FCS free RPMI 1640 supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, washed three times with medium and incubated for another 5 h in full medium to generate apoptotic cell (AC)-conditioned medium (CM) (2.5 × 106 ACs/ml medium). Cell death was confirmed by flow cytometry, using annexin V and propidium iodide staining (Immunotech, Marseille, France). ACs were centrifuged for 10 min at 1,000×g to collect the medium. The supernatant of ACs was passed through a 0.2-µm cellulose syringe filter (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) to remove remaining cells and debris. The filtrate was taken as CM. Taking into consideration that CMs from different apoptotic cells show similar effects on MΦs [19, 20], we used either CM from MCF-7 (CM-M) or Jurkat cells (CM-J). In all experiments, the concentration of CM-M corresponded to the ratio of 1 MΦ to 2 ACs (ratio 1 MΦ:2ACs), whereas CM-J was used at a ratio of 1 MΦ to 5 ACs (ratio 1 MΦ:5ACs).

Preparation of modified conditioned media

Jurkat cells were pre-incubated with the sphingomyelinase (SMase) inhibitor GW4896 [10 μM] or the ceramidase (CDase) inhibitor n-oleoyl-ethanolamine (NOE) (50 μM), while MCF-7 cells were pre-incubated for 30 min with the ceramide kinase (CERK) inhibitor NVP231 (200 nM), followed by induction of apoptosis as described. CM was obtained by incubating ACs in fresh full medium without inhibitors. CM from viable MCF-7 cells was obtained by incubating appropriate cell numbers in fresh culture medium. Necrosis was induced by heating cells at 56 C for 30 min, followed by collecting their CM. In order to digest and denaturate proteins, CM was incubated with 50 μg/ml proteinase K at 37 C for 1 h, followed by incubations at 100 C for 1 h.

Generation of a stable sphingosine kinase 2 knockdown in MCF-7 cells

For sphingosine kinase 2 (SK2) knockdown, pSilencer-siSK2 was stably transfected into MCF-7 cells (MCF-7-siSK2) using Nucleofector technology (Amaxa, Köln, Germany) as described [20, 21]. MCF-7-Neo cells were generated by nucleofection of MCF-7 cells with the pSilencer 4.1-CMV neo control vector (Ambion, Darmstadt, Germany).

Western blot analysis

Expression of ARG II, ERK5 and phospho-ERK5, phospho-ERK1/2, HA1-tag, FLAG1-tag, α-tubulin and actin was analyzed by Western blot analysis; 2 × 106 RAW264.7 MΦs were cultured in 10-cm dishes 1 day prior to experiments. Cells were starved over night when stimulated with authentic S1P. Following individual treatments, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, scraped off, lysed in 200 μl lysis buffer A (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, 1× PhosphoStop, 1× protease inhibitor mix (Roche), pH 7.5), incubated on ice for 20 min, sonified, vortexed and kept on ice for 20 min, followed by centrifugation (15,000×g, 30 min). Proteins (60–100 μg/sample) were resolved on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes by a semidry transfer cell. Polyclonal rabbit anti-ARG II (1:1,000), rabbit anti-ERK5 (1:1,000), rabbit anti-phospho-ERK5 (1:1,000), rabbit anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (1:1,000), rabbit anti-FLAG-tag (1:1,000) or monoclonal mouse anti-HA.11-tag Ab (1:1,000) were added and incubated overnight at 4°C. Polyclonal rabbit anti-actin (1:2,000) or monoclonal mouse anti-α-tubulin Ab (1:1,000) was incubated for 2 h. Afterwards, membranes were washed three times for 7 min each with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS. For protein detection by ECL, blots were incubated with a HRP-labeled goat anti-rabbit (1:2,000) or anti-mouse secondary Ab (1:2,000). For alternative protein detection, membranes were incubated with IRDye infrared secondary antibodies (1:6,000). Proteins were visualized with the Odyssey infrared imaging system from LI-COR Biosciences (Bad Homburg, Germany).

Arginase II promoter deletion constructs, transient transfection and reporter assay

An ARG II luciferase reporter plasmid (pGL3-Basic-mpARG II) containing the murine ARG II promoter (mpARG II) upstream of the luciferase gene was generated as described [2] to follow ARG II promoter activity. MΦs were transfected using jetPEI™ cationic polymer transfection reagent (Biomol, Hamburg, Germany) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Briefly, 5 × 105 cells were seeded per well in 24-well plates. They were allowed to adhere for 4 h followed by transfection. Incubations continued for 24 h, followed by individual stimulation. Luciferase activity was measured 15 h later. To obtain ARG II promoter deletion constructs, the pGL3-basic-mpARG II plasmid was digested with restriction enzymes and re-ligated. Double digestion with EcoRV in combination with BglII, HindIII or SmaI produced a −1,359 bp to −1 bp, a −442 bp to −1 bp or a −262 bp to −1 bp construct of mpARG II. Successful cloning of the deletion constructs was verified by sequencing.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Nuclear extracts from RAW264.7 MΦs were prepared and analyzed by EMSA as described [20, 22]. Individual double-stranded oligonucleotides containing a fragment of mpARG II, including the consensus sequence of the CREB binding site (boldface letters), were ordered and labeled with IRDye700. The sequences were as follows: forward 5′-IRDye700-AGA TGC TG A C GT CAC AGG GCG GTG-3′ and reverse 5′-IRDye700-CAC CGC CCT GTG AC G T CA GCA TCT CTC-3′. Resultant protein-DNA complexes were resolved on native 4% polyacrylamide gels, and the intensity of the bands, corresponding to specific CREB-DNA binding, was determined using the Odyssey infrared imaging system from LI-COR Biosciences (Bad Homburg, Germany). The reaction mixture for EMSA contained 2 μg poly (dI-dC) from Amersham Biosciences (Freiburg, Germany), 2 μl buffer D (20 mM HEPES/KOH, 20% glycerol, 100 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.25% Nonidet P-40, 2 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, pH 7.9), 4 μl buffer F (20% Ficoll-400, 100 mM HEPES/KOH, 300 mM KCl, 10 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, pH 7.9) and 10 μg nuclear proteins in a final volume of 20 μl. Supershift analysis was performed by adding 4 μg of anti-CREB-1 for 30 min followed by 250 fmol 5’-IRDye700-labeled oligonucleotides and further incubations for 20 min at room temperature. The competition assay was performed by adding 25-, 50- or 100-fold unlabeled oligonucleotides (sequences as indicated above) or with a mutated CREB binding site. The mutation was obtained by replacing AC (underlined) by TG.

CREB decoy experiment

CREB decoy-oligonucleotides were used as described before [23]. RAW264.7 cells were transiently transfected with CRE-oligonucleotides containing the CRE-consensus site derived from mpARG II and oligonucleotides with a mutated site as a control. Phosphothiorate stabilized 5′-terminal fluorescein labeled oligonucleotides were used. The sequences were as follows: forward 5′-GAG AGA TGC TG A C GT CAC AGG GCG GTG-3′ and reverse 5′-CAC CGC CCT GTG AC G T CA GCA TCT CTC-3′. Mutated oligonucleotides were obtained by replacing AC (underlined) by TG. One day before transfection cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 106 cells in 6-cm dishes. Oligonucleotides (3 μM) were added 24 h prior to cell stimulation. After changing the medium, cell stimulation was performed as indicated. Transfection efficiency was determined by counting labeled cells by fluorescence microscopy and/or FACS analysis.

Overexpression of MEK5 and ERK5

To analyze the impact of CM on ERK5 phosphorylation, we used plasmids kindly provided by Prof. Eisuke Nishida (Kyoto University, Japan). pcDNA3-HA1 and pcDNA3-FLAG1, as well as ERK5N, MEK5 WT and MEK5D, were described previously [24, 25]. ERK5N encoded a truncated form of ERK5 (residues 1–407) containing the TEY activation motif, MEK5 WT the wild-type form of its direct upstream kinase MEK5 and MEK5D the constitutive active form of MEK5, where serine 311 and threonine 315 were replaced by aspartic acid.

Overexpression of HA1-ERK5N, FLAG1-MEK5 WT and FLAG1-MEK5D was performed in HEK293 cells. Compared to MΦs, transfection of HEK293 cells can be achieved with high efficiency. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected using jetPEI™ cationic polymer transfection reagent (Biomol, Hamburg, Germany) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Briefly, 0.8 × 106 cells were seeded in 10-cm dishes. The next day, they were transfected with pcDNA3-HA1-ERK5N in combination with pcDNA3-FLAG1-MEK5 WT or pcDNA3-FLAG1-MEK5D (5 μg of each plasmid) and starved overnight, followed by individual stimulation.

Real-time PCR

2 × 106 RAW264.7 MΦs were cultured in 10-cm dishes 1 day prior to experiments. Following individual treatments, total RNA was isolated using PeqGold RNAPure (PeqLab Biotechnologie, Erlangen, Germany). Reverse transcription was performed with 1 μg RNA using iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany). Real-time PCR was achieved with Absolute QPCR SYBR Green mix (ABgene, Hamburg, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Amplification and analysis were performed using the Bio-Rad MyiQ iCylcer system. Relative mRNA expression was calculated with the BIO-RAD GeneEx gene expression macro based on the ddCt method and normalized to 18S ribosomal RNA. Following primer pairs were used for real-time PCR: murine ARG II sense—5′-ACA GGG TTG CTG TCA GCT CT-3′; antisense—5′-TGA TCC AGA CAG CCA TTT CA-3′, murine VEGF; sense—5′-TGT CAC CAC CAC GCC ATC A-3′; antisense—5′-GGA ATC CCA GAA ACA ACC CTA ATC-3′; 18S rRNA sense—5′-GTA ACC CGT TGA ACC CCA TT-3′; antisense—5′-CCC ATC CAA TCG GTA GTA GCG-3′; murine IL-10 and CD206—QuantiTect Primer Assay (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

Griess assay

To follow NO formation we measured nitrite, which is a stable oxidation product. Nitrite was determined in the supernatant of RAW264.7 MΦs; 2 × 106 RAW264.7 were seeded on 10-cm dishes 1 day prior to stimulation. Cells were incubated with CM or CM in combination with inhibitors for 16 h. Thereafter, the medium was changed, and incubations continued for 24 h with or without the addition of 100 U/ml IFNγ. Nitrite concentrations in the supernatants were determined by the Griess assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Heidelberg, Germany) and calculated in comparison to standard concentrations of NaNO2 dissolved in culture medium.

Statistical analysis

Data represented in graphs are means ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was done using the paired Student’s t test and considered significant (*) at p ≤ 0.05, (**) at p ≤ 0.005 and (***) at p ≤ 0.0005. Western blots are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Results

S1P from AC activates S1P2 to upregulate ARG II in MΦs

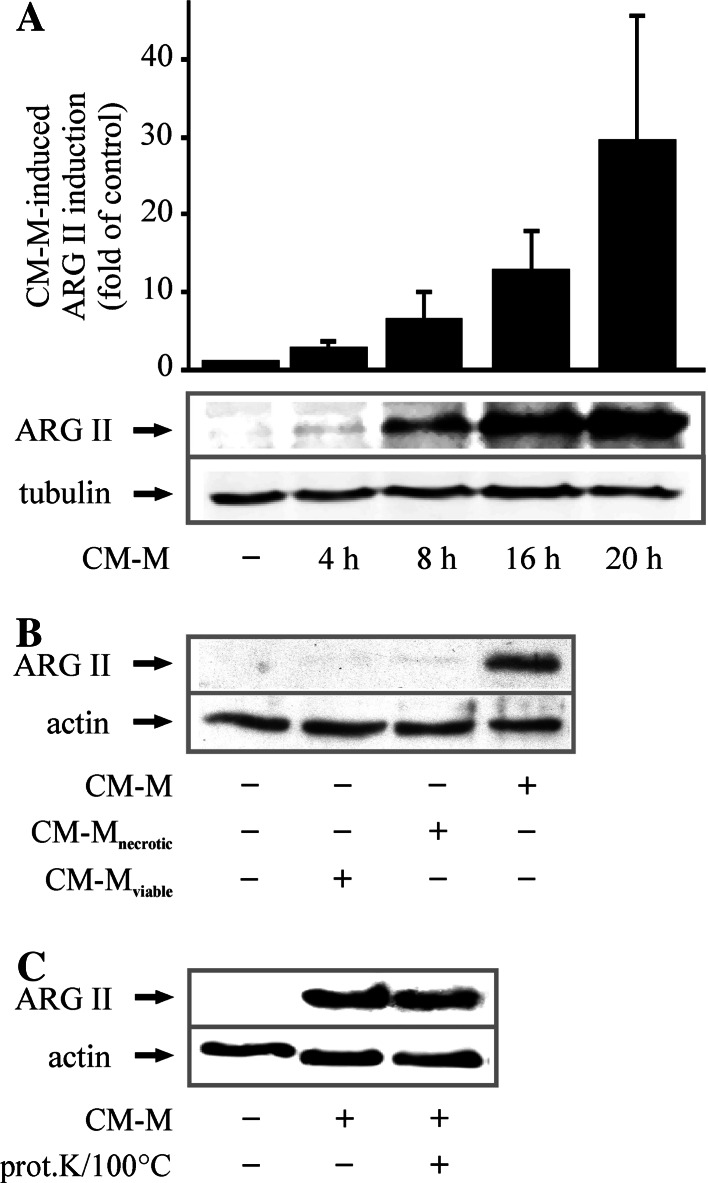

We demonstrated that apoptotic Jurkat cells as well as their conditioned medium (CM-J) induced ARG II protein expression in MΦs [2]. As conditioned medium derived from apoptotic MCF-7 cells (CM-M) also induced ARG II, this indicated that its expression is independent of the apoptotic cell type being used. However, a detailed analysis of the signaling mechanism was missing. To provide information on transducing pathways, we time-dependently determined induction of ARG II in response to CM-M in RAW264.7 MΦs. ARG II protein expression was already detectable after 4 h, followed by a steady increase up to 20 h of incubation (Fig. 1a). ARG II expression was specific for CM from ACs, since neither necrotic nor viable cell CM induced ARG II (Fig. 1b). To characterize the soluble factor(s) involved, we digested and denaturated proteins in the CM-M with 50 μg/ml proteinase K (at 37 C for 1 h), followed by incubation at 100 C for 1 h. This CM-M, lacking functional proteins, still allowed ARG II induction in MΦs (Fig. 1c), excluding AC-derived proteins as potential inducers.

Fig. 1.

CM-M upregulates ARG II in RAW264.7 MΦs. a MΦs were incubated for the indicated times with CM-M. The graph shows quantification of CM-M-mediated ARG II protein expression, n ≥ 4. b Cells were incubated for 16 h with CM-M or CM from necrotic (CM-Mnecrotic) or viable MCF-7 cells (CM-Mviable), n ≥ 3. c RAW264.7 MΦs were stimulated with CM-M or CM-M treated with 50 μg/ml proteinase K (prot.K) at 37 C for 1 h, followed by 1 h at 100 C, n ≥ 3. ARG II expression in RAW264.7 cells was determined by Western blot analysis

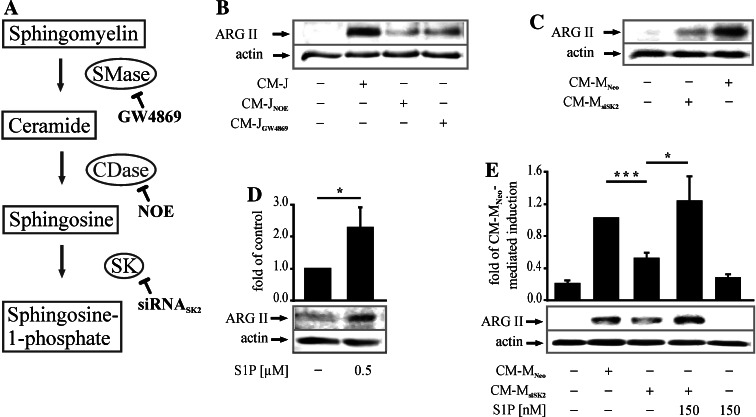

Taking into account that the glycerophospholipid and the sphingolipid metabolism are active in ACs and further considering their metabolites to be involved in differentiation, immunity and survival of MΦs [19, 26, 27], we approached their potential role in ARG II expression. Pharmacological inhibition of glycerophospholipid metabolizing enzymes phospholipase A2 and phospholipase C before inducing apoptosis in Jurkat cells did not affect CM-J-mediated ARG II upregulation (data not shown). On the contrary, consecutive inhibition of the sphingolipid metabolizing enzymes (Fig. 2a) before inducing apoptosis in Jurkat or MCF-7 cells allowed generating modified conditioned media, which were less active in ARG II upregulation. In fact, the SMase inhibitor GW4869 or the CDase inhibitor NOE in apoptotic Jurkat cells reduced the potential of CM-Js to upregulate ARG II (Fig 2b). This pointed to the importance of the sphingolipid mediator S1P for ARG II expression, since ceramide and sphingosine, produced by SMase and CDase, respectively, are S1P precursors. We excluded an impact of GW4869 and NOE on apoptosis per se by performing a FACS analysis with annexin V staining (Supplemental Fig. 1). Previously we generated a stable SK2 knockdown MCF-7 cell line, whose CM (CM-MsiSK2) showed a reduced S1P content compared to CM-MNeo (4 ng/ml S1P vs. 0.65 ng/ml S1P in the supernatants of 2 × 105 apoptotic MCF-7-Neo vs. MCF-7-siSK2 cells), with the further notion that a SK2 knockdown did not affect apoptosis initiation/execution in these cells [20]. We used CM-MsiSK2 to demonstrate the requirement of S1P for ARG II induction. As expected, CM-MsiSK2 was less potent in ARG II upregulation compared to CM-MNeo (Fig. 2c), thus corroborating a role of S1P for ARG II upregulation. Moreover, 0.5 μM authentic S1P had a significant, yet minor effect on ARG II protein expression. Expression increased 2.3-fold compared to controls (Fig. 2d), while CM-M provoked a 13-fold upregulation at 16 h as seen in Fig. 1a. This suggested the requirement of another, yet unidentified factor(s) for robust ARG II expression. Furthermore, stimulation of RAW264.7 cells with CM-MsiSK2 only induced 50% of ARG II protein compared to CM-MNeo. Application of CM-MsiSK2 in combination with 150 nM S1P restored ARG II expression to levels similar to those of CM-MNeo (Fig. 2e). Apparently, while glycerophospholipids do not seem to be involved, the sphingolipid S1P was indispensable for ARG II induction.

Fig. 2.

AC-derived S1P is required for ARG II induction in RAW264.7 MΦs. a Scheme of the sphingolipid metabolism with inhibitors used in this study. b Cells were incubated for 16 h with CM-J or modified conditioned media from Jurkat cells with SMase being inhibited with GW4869 or CDase with NOE, n ≥ 3. c MΦs were stimulated for 16 h with CM-MNeo from MCF-7 cells with a pSilencer 4.1-CMV neo control vector or CM-MsiSK2 from MCF-7 cells with a knockdown of SK2, n = 9. d RAW264.7 cells were treated with authentic S1P for 16 h. The graph quantifies ARG II expression. Asterisk marks statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05, n = 5). e MΦs were stimulated as in (c). Additionally, CM-MsiSK2 was combined with 150 nM S1P or cells were stimulated with 150 nM S1P alone. The graph shows quantification of ARG II expression. Asterisks mark statistically significant differences. (*p ≤ 0.05 and ***p ≤ 0.0005, n ≥ 4). ARG II expression in RAW264.7 cells was determined by Western blot analysis

It is well established that S1P signals by binding to S1P receptors (S1P1-5). Since S1P1 and S1P2 predominate in murine MΦs [27, 28], we employed specific inhibitors at effective concentrations to clarify which receptor signals ARG II upregulation [29, 30]. We previously confirmed the efficiency of VPC23019, a S1P1,3 antagonist, to block CM-mediated HIF-1α expression in RAW264.7 MΦs [31]. As shown in Fig. 3a, VPC23019 did not antagonize CM-M-mediated ARG II expression, while the S1P2 antagonist JTE013 at doses of 10 and 20 μM was highly effective (Fig. 3b). Of note, CM-mediated ARG II mRNA expression was already affected by 0.1 μM JTE013 (Supplemental Fig. 2). These results were underscored by siRNA knockdown of S1P2 in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 3c). A significant S1P2 knockdown to 60% (black bars) substantially reduced CM-M-dependent ARG II induction to 70% (white bars) compared to controls. Furthermore, the impact of S1P2 antagonism by JTE013 on ARG II expression was strengthened when using CM-MNVP231, depleted in C1P (Fig. 3d, e). A similar inhibition of ARG II upregulation was achieved through the combination of JTE013 with the cyclooxygenase inhibitor NS398 (Fig. 3f). These observations indicated that C1P as well as autocrine PGE2 might cooperate with S1P to induce ARG II.

Fig. 3.

S1P signals through S1P2. a, b Cells were incubated for 16 h with CM-M with or without the specific S1P1,3 antagonist VPC23019 or the S1P2 antagonist JTE013 at the indicated concentration. Antagonists were pre-incubated for 45 min, n ≥ 3. c MΦs were transfected with siRNA against S1P2 3 days prior to stimulation with CM-M for 16 h. ARG II expression and S1P2 knockdown in RAW264.7 cells were determined by Western blot analysis. The graph shows quantification of the S1P2 knockdown and ARG II expression. Asterisks mark statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05, n ≥ 4). d Scheme of the conversion of sphingomyelin to ceramide-1-phosphate with inhibitors used in this study. e Cells were incubated for 16 h with CM-M or modified conditioned media from apoptotic MCF-7 cells with CERK being inhibited with NVP231. The antagonist JTE013 was added to MΦs in the presence of CM-M or CM-MNVP231 (n ≥ 3). f RAW264.7 MΦs were incubated for 16 h with CM-M with or without JTE013 and NS398 (n ≥ 5). In e, f ARG II expression was determined by Western blot analysis. The graphs show quantification of ARG II expression. Asterisks mark statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05)

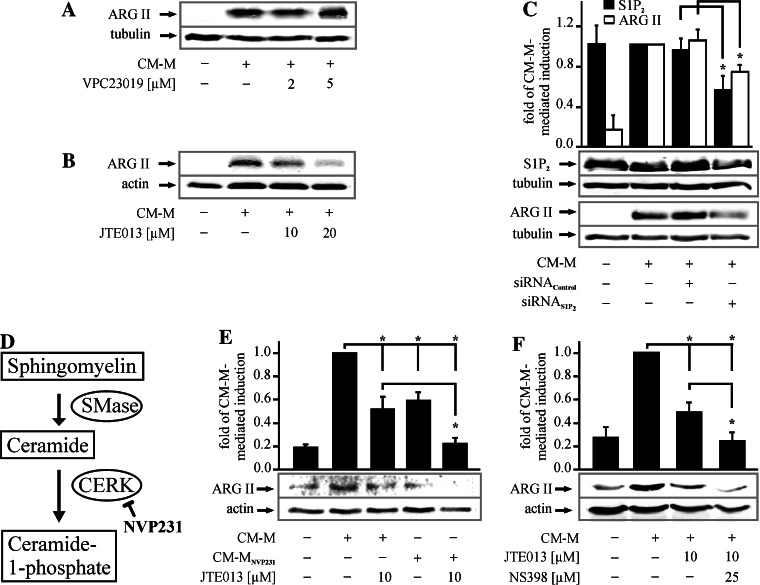

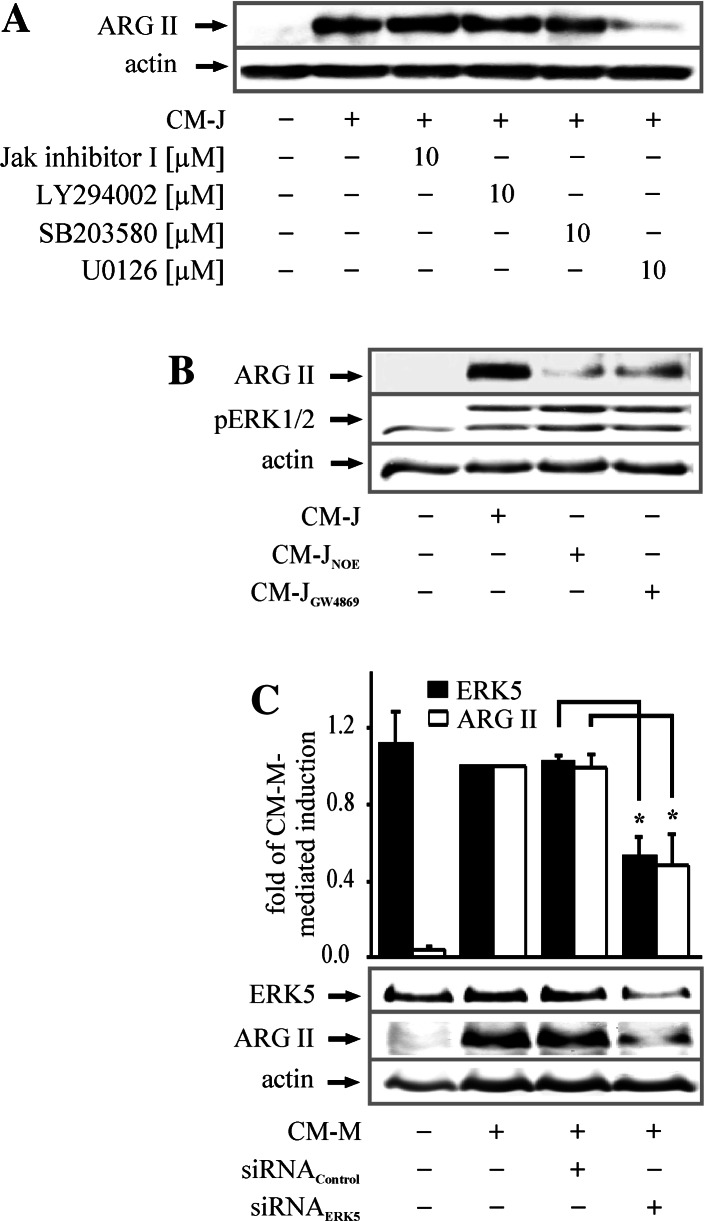

ERK5 signaling contributes to CM-mediated ARG II upregulation in MΦs

To determine the signaling pathway activated by S1P2 in more detail, we used specific inhibitors of protein kinases that are downstream effectors of receptor signaling [32–34]. Inhibition of Jak, p38 and PI3K, by the Jak inhibitor 1, SB203580 or LY294002, did not alter ARG II expression, while U0126, a MEK1/2/5 inhibitor, strongly reduced CM-J-induced ARG II protein (Fig. 4a). MEK1/2 are upstream kinases of ERK1/2, while MEK5 directly activates ERK5. To discriminate between ERK1/2 and ERK5 signaling involved in ARG II upregulation, we treated RAW264.7 cells with CM-J from apoptotic Jurkat cells where SMase or CDase were inhibited with GW4869 or NOE. Although these modified conditioned media failed to induce ARG II protein, they still induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, high concentrations of the ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 (50 μM) attenuated CM-M-dependent ARG II upregulation, while lower doses (10 μM) had no effect, despite inhibiting ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Supplemental Fig. 3). These observations ruled out the involvement of ERK1/2 and suggested ERK5 to upregulate ARG II. Having shown that CM-M time-dependently induced ERK5 phosphorylation in RAW264.7 MΦs starting at 2 h and peaking at 6 h (Supplemental Fig. 4), we corroborated the importance of ERK5 in ARG II regulation by siRNA knockdown of ERK5, which was verified by Western blot analysis. A significant reduction of ERK5 by roughly 50% (black bars) considerably diminished CM-M-mediated ARG II protein expression to approximately 50% (white bars) (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

ERK5 signaling induces ARG II. a RAW264.7 cells were incubated for 16 h with CM-J and CM-J in combination with the Jak inhibitor I, the PI3 K inhibitor LY294002, the p38 inhibitor SB203580 or the MEK1/2/5 inhibitor U0126 at the indicated concentration. Inhibitors were pre-incubated for 45 min, n ≥ 3. b Cells were incubated for 16 h with CM-J or modified conditioned media from Jurkat cells with SMase or CDase being inhibited with GW4869 or NOE, n ≥ 3. c Transiently transfected RAW264.7 cells (with siRNA against ERK5) were stimulated with CM-M for 16 h. ARG II expression, ERK1/2 phosphorylation and ERK5 knockdown in RAW264.7 MΦs were determined by Western blot analysis. The graph shows quantification of the ERK5 knockdown and ARG II expression. Asterisks mark statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05, n ≥ 4)

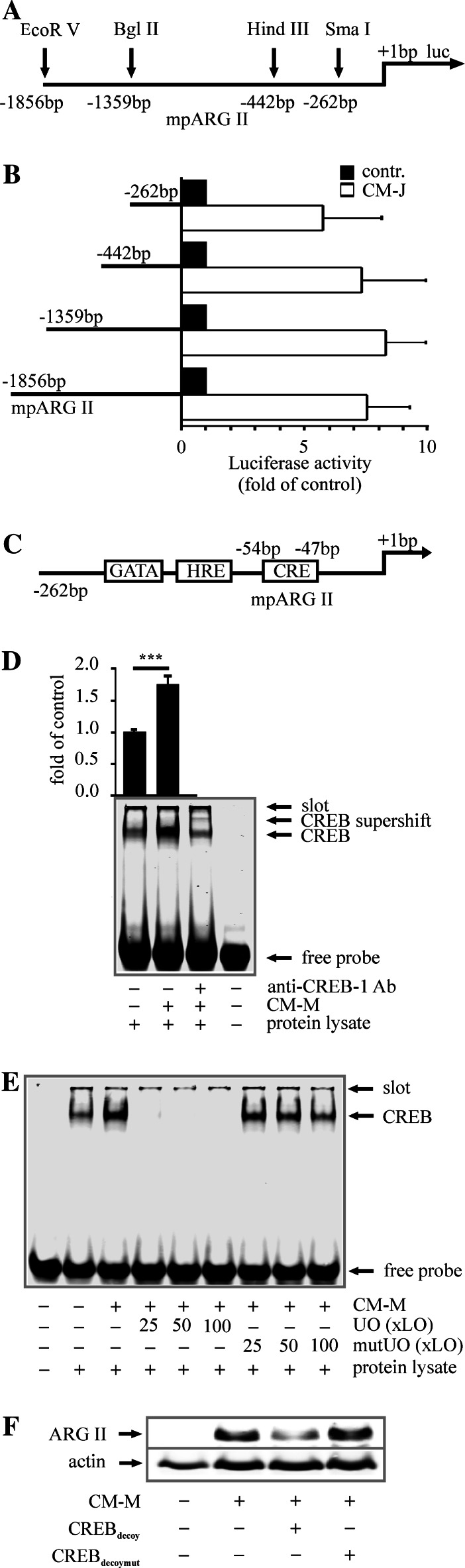

CREB facilitates CM-mediated ARG II upregulation in MΦs

As protein induction of ARG II by CM-M became detectable after 4 h and increased constantly up to 20 h (Fig. 1a), we assumed transcriptional regulation to be involved. To verify this presumption and to identify a possible transcription factor, we performed an mpARG II analysis based on luciferase reporter assays. For this purpose, we generated mpARG II constructs by serial deletion of fragments using different restriction enzymes (Fig. 5a). RAW264.7 MΦs were transfected with the respective mpARG II constructs (mpARG II−1,856 bp, −1,359 bp, −442 bp or −262 bp), further cultured for 24 h and stimulated with CM-J prior to reporter analysis. CM-J induced mpARG II activity about eightfold compared to unstimulated controls. Interestingly, the 262-bp promoter construct still displayed CM-J-mediated activity (Fig. 5b). In silico analysis of this 262-bp fragment revealed, among others, a CREB binding site (Fig. 5c). Considering that this transcription factor can in fact be activated by ERK5 [35, 36], we decided to analyze the effect of CM on CREB DNA-binding. For this purpose, we incubated RAW264.7 cells with CM-M for 16 h and isolated nuclear proteins, followed by EMSA analysis [20, 22]. CM-M significantly enhanced CREB binding (1.8-fold compared to controls) to oligonucleotides containing the mpARG II CRE site. This result was reinforced by supershift analysis using an anti-CREB-1 Ab (Fig. 5d). In accompanying competition assays, an excess of unlabeled oligonucleotides (25-, 50- or 100-fold excess of unlabeled vs. labeled oligonucleotides) completely abolished binding, while unlabeled oligonucleotides containing a mutation in the CRE site had no effect (Fig. 5e). Finally, to demonstrate the involvement of CREB in ARG II induction, we used a decoy approach to scavenge active CREB in RAW264.7 MΦs prior to its promoter binding to target genes. We transfected RAW264.7 cells with 3-μM oligonucleotides with the sequence of mpARG II, containing a mutated vs. a non-mutated CREB binding site. After resting for 48 h, RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with CM-M for 16 h, and ARG II was subsequently analyzed by Western blot analysis. Indeed, decoy oligonucleotides blocked CM-M-mediated ARG II protein induction, while the mutated decoy oligonucleotides did not alter ARG II expression (Fig. 5f).

Fig. 5.

CREB provokes ARG II induction. a Scheme of mpARG II indicating the restriction enzymes used to generate promoter constructs. b mpARG II activity was measured by luciferase reporter assay. Therefore, transfected RAW264.7 cells were stimulated for 16 h with CM-J, n ≥ 3. c Scheme of a 262 bp fragment of mpARG II containing a GATA-1, HIF-1 and CREB binding site. d, e CM-M-mediated CREB binding to mpARG II-oligonucleotides was analyzed by EMSA. d Cells were stimulated for 16 h with CM-M. A supershift was performed with an anti-CREB-1 Ab. The graph shows quantification of CREB binding to respective oligonucleotides. Asterisks mark statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.0005, n ≥ 8). e Competition assays were performed with non-mutated (UO) or mutated unlabeled oligonucleotides (mutUO) in 25-, 50- or 100-fold excess over labeled ones (xLO), n ≥ 4. f Cells were transiently transfected with mutated or non-mutated CREB decoy oligonucleotides 48 h prior to stimulation with CM-M for 16 h. ARG II expression was detected by Western blot analysis, n ≥ 3

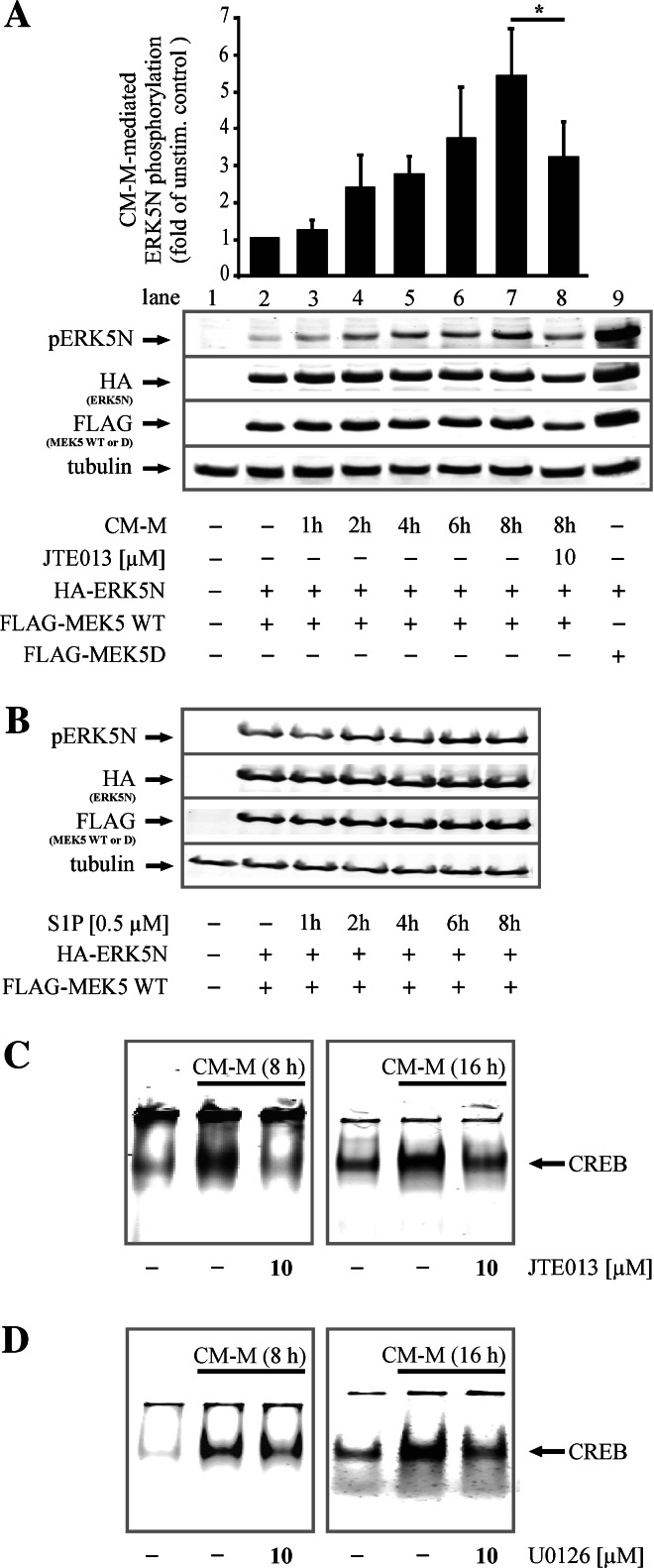

S1P2 and ERK5 are required for CREB activation and subsequent ARG II expression

To investigate a possible connection between S1P2 signaling and ERK5 phosphorylation in the cascade provoking ARG II upregulation, we analyzed the effect of the S1P2 antagonist JTE013 on CM-mediated ERK5 activation/phosphorylation. Since endogenous ERK5 phosphorylation in RAW264.7 MΦs is difficult to follow (see Supplemental Fig. 3), we overexpressed HA-tagged ERK5N, FLAG-tagged MEK5 WT and MEKD in HEK293 cells. Compared to MΦs they are easy to transfect and appropriate for these studies because, like MΦs, HEK293 cells express S1P1-3 [37]. Overexpression of HA-ERK5N, FLAG-MEK5 WT and FLAG-MEK5D was confirmed by Western blot analysis. Co-expression of HA-ERK5N, which is a truncated form containing the TEY activation motif targeted by MEK5, and FLAG-MEK5D, which is a constitutive active form, was used as a positive control and resulted in the strongest phosphorylation of ERK5N (Fig. 6a, lane 9). HEK293 cells co-expressing HA-ERK5N and FLAG-MEK5 WT were stimulated with CM-M. CM-M time-dependently induced ERK5N phosphorylation, starting at 1 h and increasing up to 8 h (Fig. 6a, lane 3–7). ERK5N phosphorylation was normalized to the sum of the expression of ERK5N and MEK WT [pERK5/(MEK5 + ERK5)]. ERK5N phosphorylation was initiated by S1P2 because the specific antagonist JTE013 (10 μM) significantly reduced CM-M-mediated ERK5N phosphorylation (Fig. 6a lane 8). Furthermore, 0.5 μM authentic S1P also induced ERK5N phosphorylation, which peaked after 6 h of stimulation (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of S1P2 or MEK5 prevents CM-M-mediated phosphorylation of ERK5 and CREB binding. a, b HEK293 cells were transiently co-transfected with pcDNA3-HA1-ERK5N and pcDNA3-FLAG1-MEK5 WT or pcDNA3-FLAG1-MEK5D and kept in FCS-free medium overnight. a Cells were incubated with CM-M for the indicated time with or without the S1P2 antagonist JTE013, which had been pre-incubated for 45 min. The graph shows quantification of CM-M-mediated ERK5N phosphorylation normalized to the sum of the expression of ERK5N and MEK WT [pERK5/(MEK5 + ERK5)]. Asterisk marks statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05, n ≥ 3). b Cells were stimulated with 0.5 μM authentic S1P for the indicated time period. ERK5N phosphorylation, HA-tag and FLAG-tag overexpression were analyzed by Western blot analysis, n ≥ 3. c, d CREB DNA-binding was determined by EMSA. RAW264.7 MΦs were incubated with CM-M with or without the S1P2 antagonist JTE013 or the MEK inhibitor U0126 at the indicated concentration for 8 h or 16 h. Antagonists or inhibitors were pre-incubated for 45 min, n ≥3. For details, see Materials and methods

The link between S1P2, ERK5 and CREB activation was then confirmed by EMSA analysis. The S1P2 antagonist JTE013 and U0126, the inhibitor of the upstream kinase of ERK5, reduced CREB binding to oligonucleotides containing the mpARG II CRE site after 8 h as well as 16 h (Fig. 6c, d).

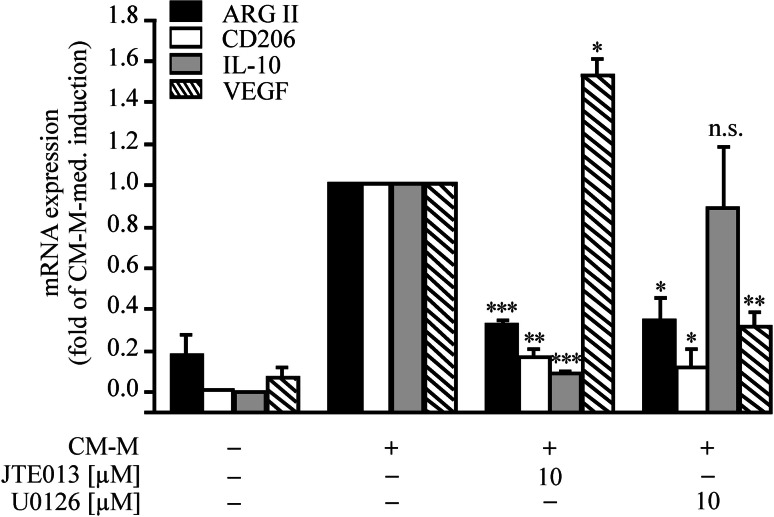

Impact of S1P2 and ERK5 antagonism/inhibition on MΦ M2-markers

Finally, we analyzed the contribution of S1P2 and ERK5 on regulating other M2 markers in order to see how far effects can be generalized. mRNA levels of ARG II, the mannose receptor (CD206), IL-10 and VEGF were significantly induced by CM-M (Fig. 7). IL-10 and VEGF are induced by distinct pathways compared to ARG II, since pharmacological inhibition/antagonism of ERK5 by U0126 and S1P2 by JTE013 neither consistently prevented IL-10 nor VEGF expression. VEGF mRNA was even significantly increased by JTE013. This observation corroborates a previous study reporting a S1P2-dependent negative regulation of angiogenesis in endothelial cells [38]. On the contrary, CM-M-dependent CD206 induction was significantly reduced by JTE013 as well as U0126, indicating that this polarization marker might be regulated in parallel to ARG II. Furthermore, neither S1P2 nor ERK5 antagonism/inhibition affected iNOS protein expression, but restored, at least in part, IFNγ-dependent NO formation in MΦs pre-incubated with CM-M (Supplemental Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Impact of S1P2 and MEK5 inhibition on MΦ polarization markers. Cells were incubated for 16 h with CM-M with or without the S1P2 antagonist JTE013 or the MEK inhibitor U0126 at the indicated concentration. Antagonists or inhibitors were pre-incubated for 45 min. The expressions of ARG II, CD206, IL-10 and VEGF were analyzed by real-time PCR and normalized to 18S rRNA, n ≥ 3

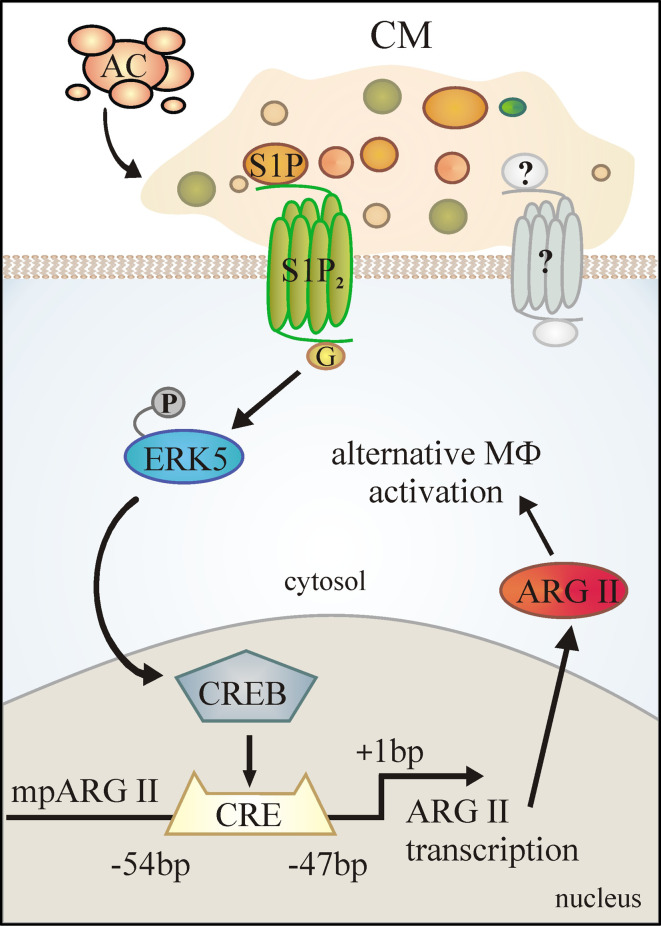

We conclude that S1P in CM activates S1P2 on MΦs, with ERK5 signaling, CREB activation and subsequent ARG II upregulation being downstream signaling events (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Schematic summary of ARG II upregulation by CM. S1P in CM contributes to ARG II induction by binding to S1P2 to activate ERK5 and subsequently CREB. Besides S1P, a second factor, possibly C1P, is required for ARG II upregulation and may induce signaling upstream or downstream of ERK5. ARG II contributes to alternative MΦ activation by impairing NO production

Discussion

Recently, we reported that pre-incubation of MΦs with CM impaired IFNγ-mediated NO production by an increase in ARG II expression, which competed with inducible NO synthase for the common substrate l-arginine [2]. Considering the lack of information on the molecular mechanisms of ARG II expression, we aimed at understanding how CM induced ARG II. First, we excluded a protein factor to modulate ARG II expression. However, bioactive glycerophospholipids and sphingolipids, such as lysophosphatidylcholine, lysophosphatidic acid, ceramide, C1P, sphingosine or S1P, are involved in cellular signaling [39, 40], some of which are released from ACs [19, 26]. To characterize the potential ARG II promoting lipid factor present in CM, we sequentially inhibited lipid metabolizing enzymes in apoptotic cells. Specifically, blocking sphingolipid metabolism in ACs attenuated ARG II expression, thus pointing to the importance of sphingolipids and in particular S1P. The contribution of S1P was underscored by using CM from MCF-7 cells with a SK2 knockdown, which contained reduced S1P amounts in comparison to normal CM [20]. Indeed, induction of ARG II by CMsiSK2 was minor, but could be restored by substituting 150 nM authentic S1P. Moreover, 0.5 μM authentic S1P induced ARG II protein expression by itself. This was weak compared to the action of CM and suggests a second factor secreted/released from ACs to be involved. This unidentified factor either directly amplifies S1P signaling or indirectly stimulates autocrine signaling by MΦs. To this end we used a suboptimal concentration of CM, which only marginally induced ARG II. Substituting increasing doses of authentic S1P failed to restore ARG II expression compared to active CM (Supplemental Fig. 5). This experiment underscores the role of the postulated second factor, since its dilution could not be rescued by S1P. Based on pharmacologic inhibition of SK with dimethylsphingosine (DMS), we originally excluded S1P as a mediator of ARG II expression [2]. Since DMS is rather unspecific and, for example, causes activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor [42], which in turn can activate ERK5 signaling [43], the use of DMS could have led to deceiving assumptions.

Five S1P G protein-coupled receptors (S1P1–5) are identified, and murine MΦs predominantly express S1P1 and S1P2 [27, 28]. Antagonizing S1P2 with JTE013 and its siRNA knockdown suggested that this receptor signals towards ARG II induction. The specificity of JTE013 in CM-mediated ARG II upregulation was underscored since it had no effect on other ARG II upregulating stimuli such as forskolin or PGE2 (data are not shown). The relevance of S1P2 signaling was strengthened when JTE013 blocked CM-mediated ARG II upregulation in primary murine peritoneal MΦs from C57BL/6 mice (Supplemental Fig. 6). Similar to our observations, Jiang et al. [44] reported that S1P signals through S1P2 in RAW264.7 MΦs, thereby enhancing cAMP accumulation triggered by isoproterenol and PGE2, while having a minor effect by itself. Thus, synergistic signaling of S1P with other mediators does not seem unusual. C1P could be another factor since it acts synergistically with S1P in human alveolar epithelial cells. S1P and C1P, while having minor effects by themselves, potentiated the production of PGE2 [41]. Initial experiments towards the identification of secondary factors were successful. In our case CMNVP231, depleted in C1P, was less effective in inducing ARG II compared to ordinary CM. This suggests that like in epithelial cells, S1P and C1P may synergize to enhance PGE2 production in MΦs, which subsequently contributes to ARG II expression. Along this line, blocking cyclooxygenase with NS398 reinforced JTE013-dependent inhibition of CM-induced ARG II expression.

Pharmacologic inhibition of established downstream effector kinases of S1P revealed that inhibition of MEK1/2/5, which are direct upstream kinases of ERK1/2/5, prevented CM-mediated ARG II induction. A direct role of ERK1/2 was excluded, since modified conditioned media that failed to induce ARG II still allowed ERK1/2 phosphorylation and the ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 that prevented CM-mediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation did not attenuate ARG II expression (Supplemental Fig. 3). Therefore, we assumed ERK5 to be important and used a ERK5 siRNA knockdown to prove this. Beside similarities in their activation motif (threonine-glutamic acid-tyrosine), ERK5 and ERK1/2 share some actions in regulating cell proliferation and differentiation. Unlike other MAP kinases, ERK5 not only transmits signals by phosphorylation, but also contains a C-terminal transcriptional activation domain [24]. Although ERK5-mediated cellular responses in cancer cells [45, 46], cell survival or cell proliferation [35, 43] are reported, little is known about its role in MΦs. One study reported LPS-mediated activation of ERK1/2, c-Jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase, p38 and ERK5 to synergize in TNF-α gene expression in MΦs [47]. Furthermore, ERK5 is indispensable for optimal colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1)-induced survival and proliferation of monocytes/macrophages [48]. Thus, our results suggest a so far unappreciated role of ERK5 in regulatory MΦ activation that is characterized by impaired NO production. The simultaneous upregulation of ERK5 and ARG II in breast and prostate cancer might suggest ERK5-mediated induction of ARG II also in these cases [12, 15, 45, 46]. A further hint for the importance of ERK5 in alternative MΦ activation was provided when AC induced PPARδ [49]. Since a ERK5/PPARδ association enhanced PPARδ transcriptional activity in a myoblast cell line [50], one could speculate that ERK5-dependent PPARδ activation contributes to regulatory MΦ polarization. These reports, along with our data, point to a crucial role of ERK5 in developing and maintaining a regulatory MΦ phenotype.

Transcriptional ARG II regulation was substantiated by mpARG II promoter analysis. Promoter deletion pointed to a 262-bp fragment upstream of the start codon to sufficiently drive luciferase reporter expression. In silico analysis of this fragment predicted binding sites for several transcription factors, including HIF-1, GATA-1 and CREB. There have been reports showing that CREB is activated by ERK5 [35, 36]. Watson et al. reported that the ERK5 pathway, triggered by neurotrophins was necessary for CREB-mediated survival of neurons. Expression of a dominant-negative MEK5 prevented ERK5 activation as well as CREB phosphorylation. Stimulated by these observations, we investigated the impact of CREB in CM-mediated ARG II upregulation. Indeed, EMSA, including competition assays and supershift analysis, as well as a CREB decoy-oligonucleotide approach, demonstrated its importance for CM-mediated ARG II induction. Previous studies reported that ARG II mRNA is upregulated by 8-bromo-cAMP [8]. Even though molecular mechanisms were not elucidated, studies may imply a cAMP/CREB axis. We upregulated ARG II in RAW264.7 MΦs via cAMP, by activating adenylate cyclase with 100 μM forskolin (Supplemental Fig. 7), which further implies a contributing role of CREB. Interestingly, authentic S1P induced ERK5 phosphorylation, and S1P in CM may directly bind to S1P2. This receptor couples to Gq and G12 proteins [51], which are known to activate ERK5 [52]. Our findings go along with previous studies showing that S1P activates CREB in, e.g., vascular smooth muscle [32] and breast cancer cells [53]. In vascular smooth muscle cells, CREB activation was proposed to be ERK1/2-mediated based on the use of PD98059 and U0126 [32]. Meanwhile, it became evident that these inhibitors, originally assumed to be specific for MEK1/2, also inhibit the MEK5/ERK5 pathway. Thus, there is room for speculation that in vascular smooth muscle S1P also triggers CREB activation via ERK5.

Our study suggests that CM contributes to establishing a regulatory MΦ phenotype by activating ERK5/CREB and subsequent ARG II upregulation, which attenuates NO production. This pathway may contribute to inducing other macrophage activation markers such as CD206, and thus its analysis contributes to better understanding MΦ phenotype characteristics.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplemental Figure 1. Pharmacological inhibition of SMase, CDase and CERK with GW4869, NOE and NVP231 did not interfere with staurosporine-mediated apoptosis of MCF-7 cells. MCF-7 cells were pre-incubated with 10 µM GW4869, 50 µM NOE or 0.2 µM NVP231 for 45 minutes before inducing apoptosis for 2.5 hours with staurosporine (sts) in FCS-free medium. Cell death was quantified by AnnexinV staining using FACS analysis (according to Lauber et al., Cell, Vol. 113, 717-730, 2003). Asterisk marks statistically significant differences. * p ≤ 0.05, n.s. (not significant), n ≥ 3 (JPEG 259 kb)

Supplemental Figure 2. CM-M-dependent ARG II mRNA expression in RAW264.7 MΦs is mediated by S1P2. MΦs were incubated for 16 hours with CM-M with or without the S1P2 antagonist JTE013 (0.1 µM). The antagonist was pre-incubated for 45 minutes. ARG II mRNA expression was determined by quantitative real-time PCR. n = 4 (JPEG 210 kb)

Supplemental Figure 3. ERK1/2 signaling does not mediated ARG II up-regulation by CM-M. RAW264.7 cells were incubated for 16 hours with CM-M with or without the specific ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 at the indicated concentrations. PD98059 was pre-incubated for 45 minutes. ARG II expression and ERK1/2 phosphorylation were determined by Western analysis. n ≥ 3 (JPEG 579 kb)

Supplemental Figure 4. CM-M induces ERK5 phosphorylation in RAW264.7 MΦs. Cells were incubated with CM-M for indicated time periods. ERK5 phosphorylation was determined by Western analysis. n = 3 (JPEG 597 kb)

Supplemental Figure 5. Sub-optimal concentrations of CM-J cannot be rescued by S1P to restore ARG II up-regulation. RAW264.7 cells were incubated for 16 hours with CM-J at a ratio of 5 ACs to 1 MΦ (5ACs:1MΦ) or 3 ACs to 1 MΦ (3ACs:1MΦ). CM-J (3ACs:1MΦ) was combined with the indicated concentrations of S1P. ARG II expression was determined by Western analysis. The graph shows quantification of ARG II expression. n ≥ 3 (JPEG 354 kb)

Supplemental Figure 6. Physiological relevance of S1P2 signaling for ARG II expression in primary MΦs. Primary murine peritoneal MΦs from C57BL/6 mice were incubated for 16 hours with CM-M with or without the specific S1P2 antagonist JTE013 (10 µM). JTE013 was pre-incubated for 45 minutes. ARG II expression was determined by Western analysis. n = 3 (JPEG 404 kb)

Supplemental Figure 7. Activation of adenylate cyclase with 100 µM forskolin induces ARG II expression in RAW264.7 MΦs. Cells were incubated for 16 hours with 100 µM forskolin. ARG II expression was determined by Western analysis. n = 3 (JPEG 366 kb)

Supplemental Figure 8. RAW264.7 MΦs were stimulated for 16 hours with CM-M with or without the S1P2 antagonist JTE013 or the MEK inhibitor U0126 at the indicated concentration. Antagonists or inhibitors were pre-incubated for 45 minutes, followed by incubation with or without 100 U/ml IFNγ for 24 hours. The supernatants were harvested and nitrite levels determined by the Griess assay. iNOS expression was determined by Western analysis. n = 4 (JPEG 317 kb)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Br 999, FOG 784, and Excellence Cluster Cardiopulmonary System), Sander Foundation and LOEWE/LiFF. We thank Prof. Eisuke Nishida (Kyoto University, Japan) for kindly providing pcDNA3-HA1-ERK5N, pcDNA3-FLAG1-MEK5 WT and pcDNA3-FLAG1-MEK5D expression plasmids.

Abbreviations

- AC

Apoptotic cell

- CM

Apoptotic cell-conditioned medium

- ARG II

Arginase II

- MΦ

Macrophage

- mpARG II

Murine ARG II promoter

- cAMP

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CREB

cAMP responsive element binding protein

- CDase

Ceramidase

- CERK

Ceramide kinase

- SMase

Sphingomyelinase

- NO

Nitric oxide

- NOE

n-oleoyl-ethanolamine

- SK2

Sphingosine kinase 2

- S1P

Sphingosine-1-phosphate

- S1P2

S1P receptor 2

- PGE2

Prostaglandin E2

- ERK5

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5

- MEK5

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 5

- C1P

Ceramide-1-phosphate

- Ab

Antibody

References

- 1.Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:958. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johann AM, Barra V, Kuhn AM, Weigert A, von Knethen A, Brune B. Apoptotic cells induce arginase II in macrophages, thereby attenuating NO production. Faseb J. 2007;21:2704. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7815com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris SM., Jr Enzymes of arginine metabolism. J Nutr. 2004;134:2743S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.10.2743S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gotoh T, Mori M. Arginase II downregulates nitric oxide (NO) production and prevents NO-mediated apoptosis in murine macrophage-derived RAW 264.7 cells. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:427. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.3.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Topal G, Brunet A, Walch L, Boucher JL, David-Dufilho M. Mitochondrial arginase II modulates nitric-oxide synthesis through nonfreely exchangeable l-arginine pools in human endothelial cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:1368. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.103747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grody WW, Dizikes GJ, Cederbaum SD. Human arginase isozymes. Isozymes Curr Top Biol Med Res. 1987;13:181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vockley JG, Jenkinson CP, Shukla H, Kern RM, Grody WW, Cederbaum SD. Cloning and characterization of the human type II arginase gene. Genomics. 1996;38:118. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris SM, Jr, Kepka-Lenhart D, Chen LC. Differential regulation of arginases and inducible nitric oxide synthase in murine macrophage cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:E740. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.275.5.E740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barksdale AR, Bernard AC, Maley ME, Gellin GL, Kearney PA, Boulanger BR, Tsuei BJ, Ochoa JB. Regulation of arginase expression by T-helper II cytokines and isoproterenol. Surgery. 2004;135:527. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu W, Kaneko FT, Zheng S, Comhair SA, Janocha AJ, Goggans T, Thunnissen FB, Farver C, Hazen SL, Jennings C, Dweik RA, Arroliga AC, Erzurum SC. Increased arginase II and decreased NO synthesis in endothelial cells of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Faseb J. 2004;18:1746. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2317fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King NE, Rothenberg ME, Zimmermann N. Arginine in asthma and lung inflammation. J Nutr. 2004;134:2830S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.10.2830S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mumenthaler SM, Yu H, Tze S, Cederbaum SD, Pegg AE, Seligson DB, Grody WW. Expression of arginase II in prostate cancer. Int J Oncol. 2008;32:357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rotondo R, Mastracci L, Piazza T, Barisione G, Fabbi M, Cassanello M, Costa R, Morandi B, Astigiano S, Cesario A, Sormani MP, Ferlazzo G, Grossi F, Ratto GB, Ferrini S, Frumento G. Arginase 2 is expressed by human lung cancer, but it neither induces immune suppression, nor affects disease progression. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1108. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tate DJ, Jr, Vonderhaar DJ, Caldas YA, Metoyer T, Patterson JRt, Aviles DH, Zea AH. Effect of arginase II on l-arginine depletion and cell growth in murine cell lines of renal cell carcinoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2008;1:14. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porembska Z, Luboinski G, Chrzanowska A, Mielczarek M, Magnuska J, Baranczyk-Kuzma A. Arginase in patients with breast cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 2003;328:105. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(02)00391-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grandvaux N, Gaboriau F, Harris J, tenOever BR, Lin R, Hiscott J. Regulation of arginase II by interferon regulatory factor 3 and the involvement of polyamines in the antiviral response. Febs J. 2005;272:3120. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corraliza I, Moncada S. Increased expression of arginase II in patients with different forms of arthritis. Implications of the regulation of nitric oxide. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:2261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marathe C, Bradley MN, Hong C, Lopez F, Ruiz de Galarreta CM, Tontonoz P, Castrillo A. The arginase II gene is an anti-inflammatory target of liver X receptor in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605237200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weigert A, Johann AM, von Knethen A, Schmidt H, Geisslinger G, Brune B. Apoptotic cells promote macrophage survival by releasing the antiapoptotic mediator sphingosine-1-phosphate. Blood. 2006;108:1635. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-014852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weigert A, Tzieply N, von Knethen A, Johann AM, Schmidt H, Geisslinger G, Brune B. Tumor cell apoptosis polarizes macrophages role of sphingosine-1-phosphate. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3810. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-12-1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johann AM, Weigert A, Eberhardt W, Kuhn AM, Barra V, von Knethen A, Pfeilschifter JM, Brune B. Apoptotic cell-derived sphingosine-1-phosphate promotes HuR-dependent cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA stabilization and protein expression. J Immunol. 2008;180:1239. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Von Knethen AA, Brune B. Delayed activation of PPARgamma by LPS and IFN-gamma attenuates the oxidative burst in macrophages. Faseb J. 2001;15:535. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0187com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Knethen A, Lotero A, Brune B. Etoposide and cisplatin induced apoptosis in activated RAW 264.7 macrophages is attenuated by cAMP-induced gene expression. Oncogene. 1998;17:387. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morimoto H, Kondoh K, Nishimoto S, Terasawa K, Nishida E. Activation of a C-terminal transcriptional activation domain of ERK5 by autophosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35449. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704079200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terasawa K, Okazaki K, Nishida E. Regulation of c-Fos and Fra-1 by the MEK5-ERK5 pathway. Genes Cells. 2003;8:263. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2003.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lauber K, Bohn E, Krober SM, Xiao YJ, Blumenthal SG, Lindemann RK, Marini P, Wiedig C, Zobywalski A, Baksh S, Xu Y, Autenrieth IB, Schulze-Osthoff K, Belka C, Stuhler G, Wesselborg S. Apoptotic cells induce migration of phagocytes via caspase-3-mediated release of a lipid attraction signal. Cell. 2003;113:717. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00422-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goetzl EJ, Wang W, McGiffert C, Huang MC, Graler MH. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and its G protein-coupled receptors constitute a multifunctional immunoregulatory system. J Cell Biochem. 2004;92:1104. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughes JE, Srinivasan S, Lynch KR, Proia RL, Ferdek P, Hedrick CC. Sphingosine-1-phosphate induces an antiinflammatory phenotype in macrophages. Circ Res. 2008;102:950. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.170779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao C, Fernandes MJ, Turgeon M, Tancrede S, Di Battista J, Poubelle PE, Bourgoin SG. Specific and overlapping sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor functions in human synoviocytes: impact of TNF-alpha. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:2323. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800143-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balthasar S, Bergelin N, Lof C, Vainio M, Andersson S, Tornquist K. Interactions between sphingosine-1-phosphate and vascular endothelial growth factor signalling in ML-1 follicular thyroid carcinoma cells. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:521. doi: 10.1677/ERC-07-0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herr B, Zhou J, Werno C, Menrad H, Namgaladze D, Weigert A, Dehne N, Brune B. The supernatant of apoptotic cells causes transcriptional activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in macrophages via sphingosine-1-phosphate and transforming growth factor-beta. Blood. 2009;114:2140. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-201889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathieson FA, Nixon GF. Sphingolipids differentially regulate mitogen-activated protein kinases and intracellular Ca2+ in vascular smooth muscle: effects on CREB activation. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:351. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kluk MJ, Hla T. Signaling of sphingosine-1-phosphate via the S1P/EDG-family of G-protein-coupled receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1582:72. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weis N, Weigert A, von Knethen A, Brune B. Heme oxygenase-1 contributes to an alternative macrophage activation profile induced by apoptotic cell supernatants. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1280. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-10-1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watson FL, Heerssen HM, Bhattacharyya A, Klesse L, Lin MZ, Segal RA. Neurotrophins use the Erk5 pathway to mediate a retrograde survival response. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:981. doi: 10.1038/nn720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma G, Goalstone ML. Dominant negative FTase (DNFTalpha) inhibits ERK5, MEF2C and CREB activation in adipogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2005;245:93. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meyer zu Heringdorf D, Lass H, Kuchar I, Lipinski M, Alemany R, Rumenapp U, Jakobs KH. Stimulation of intracellular sphingosine-1-phosphate production by G-protein-coupled sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;414:145. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(01)00789-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inoki I, Takuwa N, Sugimoto N, Yoshioka K, Takata S, Kaneko S, Takuwa Y. Negative regulation of endothelial morphogenesis and angiogenesis by S1P2 receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;346:293. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu Y, Xiao YJ, Zhu K, Baudhuin LM, Lu J, Hong G, Kim KS, Cristina KL, Song L, Elson SWF,P, Markman M, Belinson J. Unfolding the pathophysiological role of bioactive lysophospholipids. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord. 2003;3:23. doi: 10.2174/1568008033340414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:139. doi: 10.1038/nrm2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pettus BJ, Kitatani K, Chalfant CE, Taha TA, Kawamori T, Bielawski J, Obeid LM, Hannun YA. The coordination of prostaglandin E2 production by sphingosine-1-phosphate and ceramide-1-phosphate. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:330. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.008722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Igarashi Y, Kitamura K, Toyokuni T, Dean B, Fenderson B, Ogawass T, Hakomori S. A specific enhancing effect of N, N-dimethylsphingosine on epidermal growth factor receptor autophosphorylation. Demonstration of its endogenous occurrence (and the virtual absence of unsubstituted sphingosine) in human epidermoid carcinoma A431 cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:5385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scapoli L, Ramos-Nino ME, Martinelli M, Mossman BT. Src-dependent ERK5 and Src/EGFR-dependent ERK1/2 activation is required for cell proliferation by asbestos. Oncogene. 2004;23:805. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang LI, Collins J, Davis R, Lin KM, DeCamp D, Roach T, Hsueh R, Rebres RA, Ross EM, Taussig R, Fraser I, Sternweis PC. Use of a cAMP BRET sensor to characterize a novel regulation of cAMP by the sphingosine 1-phosphate/G13 pathway. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609695200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Esparis-Ogando A, Diaz-Rodriguez E, Montero JC, Yuste L, Crespo P, Pandiella A. Erk5 participates in neuregulin signal transduction and is constitutively active in breast cancer cells overexpressing ErbB2. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:270. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.1.270-285.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCracken SR, Ramsay A, Heer R, Mathers ME, Jenkins BL, Edwards J, Robson CN, Marquez R, Cohen P, Leung HY. Aberrant expression of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 in human prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:2978. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu W, Downey JS, Gu J, Di Padova F, Gram H, Han J. Regulation of TNF expression by multiple mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. J Immunol. 2000;164:6349. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rovida E, Spinelli E, Sdelci S, Barbetti V, Morandi A, Giuntoli S, Dello Sbarba P. ERK5/BMK1 is indispensable for optimal colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1)-induced proliferation in macrophages in a Src-dependent fashion. J Immunol. 2008;180:4166. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.4166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mukundan L, Odegaard JI, Morel CR, Heredia JE, Mwangi JW, Ricardo-Gonzalez RR, Goh YP, Eagle AR, Dunn SE, Awakuni JU, Nguyen KD, Steinman L, Michie SA, Chawla A. PPAR-delta senses and orchestrates clearance of apoptotic cells to promote tolerance. Nat Med. 2009;15:1266. doi: 10.1038/nm.2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woo CH, Massett MP, Shishido T, Itoh S, Ding B, McClain C, Che W, Vulapalli SR, Yan C, Abe J. ERK5 activation inhibits inflammatory responses via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta (PPARdelta) stimulation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602369200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siehler S, Manning DR. Pathways of transduction engaged by sphingosine 1-phosphate through G protein-coupled receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1582:94. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fukuhara S, Marinissen MJ, Chiariello M, Gutkind JS. Signaling from G protein-coupled receptors to ERK5/Big MAPK 1 involves Galpha q and Galpha 12/13 families of heterotrimeric G proteins. Evidence for the existence of a novel Ras AND Rho-independent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002410200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hadizadeh S, King DN, Shah S, Sewer MB. Sphingosine-1-phosphate regulates the expression of the liver receptor homologue-1. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;283:104. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Pharmacological inhibition of SMase, CDase and CERK with GW4869, NOE and NVP231 did not interfere with staurosporine-mediated apoptosis of MCF-7 cells. MCF-7 cells were pre-incubated with 10 µM GW4869, 50 µM NOE or 0.2 µM NVP231 for 45 minutes before inducing apoptosis for 2.5 hours with staurosporine (sts) in FCS-free medium. Cell death was quantified by AnnexinV staining using FACS analysis (according to Lauber et al., Cell, Vol. 113, 717-730, 2003). Asterisk marks statistically significant differences. * p ≤ 0.05, n.s. (not significant), n ≥ 3 (JPEG 259 kb)

Supplemental Figure 2. CM-M-dependent ARG II mRNA expression in RAW264.7 MΦs is mediated by S1P2. MΦs were incubated for 16 hours with CM-M with or without the S1P2 antagonist JTE013 (0.1 µM). The antagonist was pre-incubated for 45 minutes. ARG II mRNA expression was determined by quantitative real-time PCR. n = 4 (JPEG 210 kb)

Supplemental Figure 3. ERK1/2 signaling does not mediated ARG II up-regulation by CM-M. RAW264.7 cells were incubated for 16 hours with CM-M with or without the specific ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 at the indicated concentrations. PD98059 was pre-incubated for 45 minutes. ARG II expression and ERK1/2 phosphorylation were determined by Western analysis. n ≥ 3 (JPEG 579 kb)

Supplemental Figure 4. CM-M induces ERK5 phosphorylation in RAW264.7 MΦs. Cells were incubated with CM-M for indicated time periods. ERK5 phosphorylation was determined by Western analysis. n = 3 (JPEG 597 kb)

Supplemental Figure 5. Sub-optimal concentrations of CM-J cannot be rescued by S1P to restore ARG II up-regulation. RAW264.7 cells were incubated for 16 hours with CM-J at a ratio of 5 ACs to 1 MΦ (5ACs:1MΦ) or 3 ACs to 1 MΦ (3ACs:1MΦ). CM-J (3ACs:1MΦ) was combined with the indicated concentrations of S1P. ARG II expression was determined by Western analysis. The graph shows quantification of ARG II expression. n ≥ 3 (JPEG 354 kb)

Supplemental Figure 6. Physiological relevance of S1P2 signaling for ARG II expression in primary MΦs. Primary murine peritoneal MΦs from C57BL/6 mice were incubated for 16 hours with CM-M with or without the specific S1P2 antagonist JTE013 (10 µM). JTE013 was pre-incubated for 45 minutes. ARG II expression was determined by Western analysis. n = 3 (JPEG 404 kb)

Supplemental Figure 7. Activation of adenylate cyclase with 100 µM forskolin induces ARG II expression in RAW264.7 MΦs. Cells were incubated for 16 hours with 100 µM forskolin. ARG II expression was determined by Western analysis. n = 3 (JPEG 366 kb)

Supplemental Figure 8. RAW264.7 MΦs were stimulated for 16 hours with CM-M with or without the S1P2 antagonist JTE013 or the MEK inhibitor U0126 at the indicated concentration. Antagonists or inhibitors were pre-incubated for 45 minutes, followed by incubation with or without 100 U/ml IFNγ for 24 hours. The supernatants were harvested and nitrite levels determined by the Griess assay. iNOS expression was determined by Western analysis. n = 4 (JPEG 317 kb)