Abstract

Green fluorescent protein (GFP) is a powerful tool for studying gene expression, protein localization, protein–protein interactions, calcium concentrations, and redox potentials owing to its intrinsic fluorescence. However, GFP not only contains a chromophore but is also tightly folded in a temperature-dependent manner. The latter property of GFP has recently been exploited (1) to characterize the translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane and (2) to discriminate between protein transport across and into biomembranes in vivo. I therefore suggest that GFP could be a valuable tool for the general analysis of protein transport machineries and pathways in a variety of organisms. Moreover, results from such studies could be important for the interpretation and optimization of classical experiments using GFP tagging.

Keywords: Green fluorescent protein, Protein translocase, Protein transport machineries, Protein localization, GFP tagging

Introduction: versatility and properties of GFP

Osamu Shimomura, Martin Chalfie, and Roger Tsien won the Noble Prize in Chemistry 2008 “for the discovery and development of the green fluorescent protein, GFP” (http://nobelprize.org/). In fact, GFP from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria has become one of the most valuable tools for the analysis of molecular processes in vivo [1–3]:

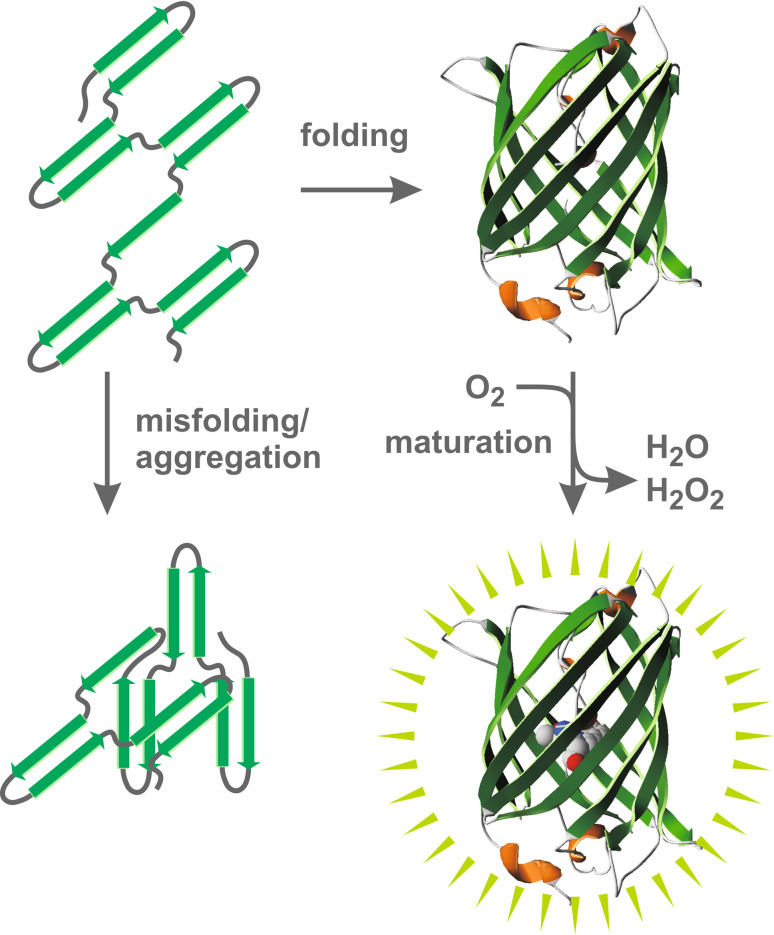

The protein is widely used for organelle-, cell- and tissue-specific expression and localization studies [1–3]. Furthermore, GFP-fusion constructs serve as indicators for protein–protein interactions, Ca2+-levels [1, 2], pH values [4, 5], and redox potentials [6–9]. All of these methods are based on the fluorescence of the GFP chromophore, which is autocatalytically formed after the protein has established an 11-stranded beta-barrel as the near-native tertiary structure (Fig. 1) [2, 10, 11]. Chromophore maturation occurs without additional factors. The reaction solely requires molecular oxygen as well as residues Ser/Thr65, Tyr66, and Gly67. A nucleophilic attack of the Gly67 amide nitrogen atom at the Ser/Thr65 carbonyl carbon atom reversibly yields a cyclic imidazolone structure. After this backbone cyclization reaction, the conjugated double bonds of the chromophore are formed by irreversible oxidation and dehydration [2, 10]. Since protein denaturation abolishes GFP fluorescence [12], the correct tertiary structure is essential for both, the initial formation of the chromophore and its fluorescence once formed [10].

Fig. 1.

Properties of GFP. Newly synthesized GFP establishes a stable, near-native tertiary structure at a lower temperature. The protein subsequently matures in the presence of oxygen, yielding the fluorescent chromophore in the center of the beta-barrel. Alternatively, at a higher temperature, GFP tends to misfold and/or to form non-fluorescent aggregates

Apart from fluorescence, further important properties of GFP include (1) its temperature-dependent folding kinetics, (2) the intrinsic tendency to aggregate, and (3) the stability of the mature protein (Fig. 1) [1, 2, 13]. Folding of GFP was estimated to require several minutes in vitro and in vivo and therefore seems to be rather slow [2, 11, 13]. Moreover, GFP folding depends on the type of organism, presumably due to the availability of certain chaperones [2]. At a temperature above 25°C, wild-type GFP misfolds, resulting in aggregates in vitro and in Escherichia coli [1, 2, 12]. For example, at 35°C, the in vitro folding and aggregation rates of wild-type GFP (and presumably some other commonly used GFP variants) are comparable. This could explain why mature wild-type GFP cannot be obtained in high yields from E. coli at 37°C [12] (in contrast to so-called “folding mutants” [10, 12, 13]). Once folded, mature GFP is a very stable protein, even at a temperature up to at least 65°C [1]. Unfolding in vitro requires rather harsh conditions and is usually very slow [12, 13]. For example, GFP can be incubated overnight in up to 3.5 M guanidine hydrochloride at 25°C without significant denaturation [12]. Recently, as outlined below, the unique folding/aggregation/unfolding properties of GFP were used for studying protein passage across and into the outer mitochondrial membrane [14]. Here, I would like to suggest that the latter technique could also be suited for studying protein transport across and into biomembranes in a more general context. Thus, before describing the technique for mitochondria, I will first continue with a brief general overview on protein transport machineries.

Protein transport across and into biomembranes

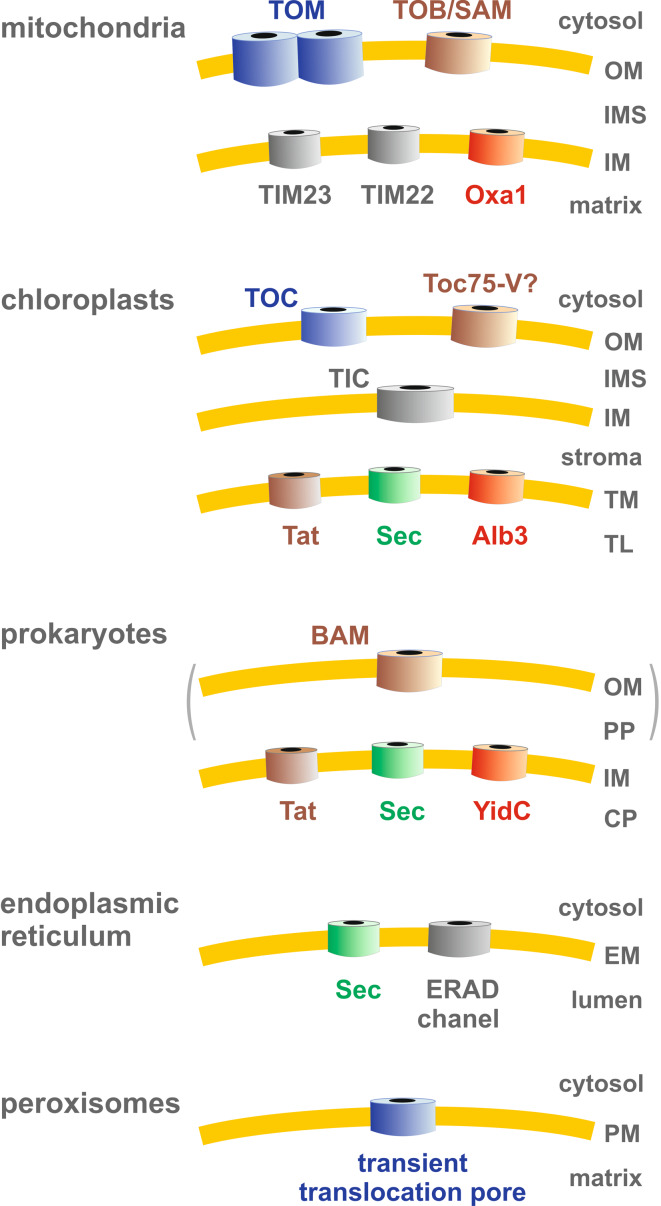

The transport of proteins across and the insertion of proteins into biomembranes are both essential processes for all life forms. Accordingly, several transport machineries are highly conserved in the course of evolution (Fig. 2): For example, Sec translocases are found in the plasma membrane of prokaryotes, in the thylakoid membrane of chloroplasts [15], and in the endoplasmic reticulum of all eukaryotes [16]. Owing to numerous crystallographic and mutational analyses, the Sec translocase is presumably the best-understood protein transport and insertion machinery. All Sec translocases are homologous and mediate the transport of proteins across and into biomembranes [15, 16]. Prokaryotes and chloroplasts furthermore have a highly dynamic Tat system for the transport of folded proteins across the plasma membrane or the thylakoid membrane, respectively [15, 17]. The insertion of selected proteins from an internal compartment into the surrounding membrane is mediated by Oxa1 in mitochondria, Alb3 in chloroplasts, and YidC in bacteria [15, 18]. Again, all three insertases Oxa1/Alb3/YidC are homologous [18]. Another example for a highly conserved protein sorting pathway is the insertion of beta-barrel proteins into the outer membranes of mitochondria and Gram-negative bacteria. This function is exerted by the TOB/SAM complex and the BAM complex, respectively [19, 20].

Fig. 2.

Overview of selected protein transport machineries and their subcellular or suborganellar localizations. TOM, translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane; TOB/SAM, topogenesis of mitochondrial outer membrane beta-barrel/sorting and assembly machinery; TIM23 and TIM22, translocases of the inner mitochondrial membrane; Oxa1, oxidase assembly insertase; TOC and TIC, translocases of the outer and inner chloroplast envelope; Toc75-V, further member of the Omp85 family; Tat, twin-arginine translocation system; Sec, Sec (secretory) translocase complex; Alb3, albino3 translocase; BAM, beta-barrel assembly machinery; YidC, membrane protein insertase; ERAD, endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation machinery. OM, outer membrane; IMS, intermembrane space; IM, inner membrane; TM, thylakoid membrane; TL, thylakoid lumen; PP, periplasmic space; CP, cytoplasm; EM, ER membrane; PM, peroxisomal membrane

In contrast to these conserved transport machineries, there are also more specialized, organelle-specific protein transport machineries (e.g., Fig. 2): In plants, another member of the Omp85 family, Toc75-V, might insert beta-barrel proteins using an alternative insertion pathway [21]. Nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins usually pass the outer mitochondrial membrane via the TOM complex. Subsequent protein transport across and into the inner mitochondrial membrane is mediated by the TIM23 complex as well as the evolutionary related TIM22 complex [22–24]. In analogy, the TOC and TIC machineries channel proteins across the outer and inner envelope of chloroplasts [24].

Despite significant advances in the field, many puzzling translocases and protein transport pathways remain to be studied in much more detail (e.g., Fig. 2): For example, it is still neither known which pore-forming machinery exports misfolded or aggregated proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum [25], nor how (folded) proteins exactly pass the membrane of peroxisomes as well as specialized related organelles such as glycosomes in trypanosomes and glyoxysomes in plants and fungi [26]. Candidates for the protein-conducting channel in the endoplasmic reticulum are, e.g., the Sec61 translocon or oligomeric Derlins [25]. In yeast peroxisomes, Pex5p and Pex14p are, according to recent models, the core components of the transient translocation pore of a highly dynamic receptor-cycle-mediated protein import machinery [26]. Last but not least, we are just beginning to understand the specialized protein transport of pathogenic (intracellular) bacteria [27, 28] and parasitic protists [29, 30]. Deciphering these machineries and pathways will not only be interesting for biologists but could also have important medical implications.

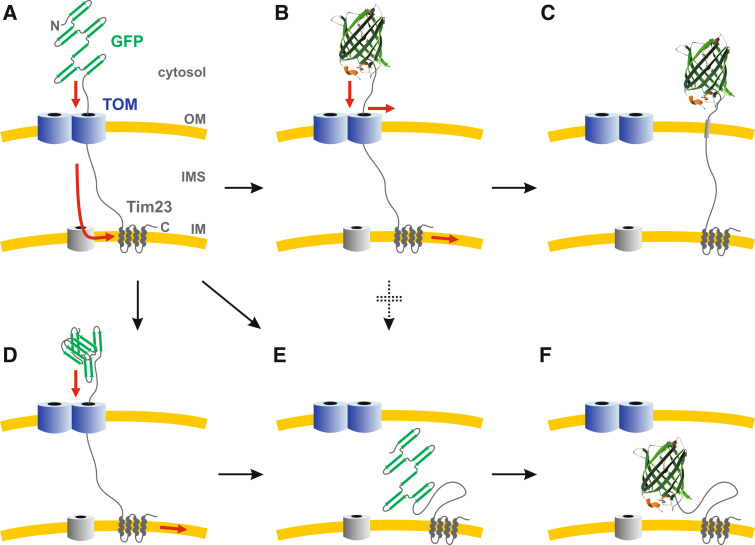

GFP-Tim23 as a novel tool for studying the TOM and the TIM23 complex

N-terminal GFP tagging of yeast Tim23, one core component of the TIM23 complex in mitochondria (Fig. 2), had been previously shown to anchor the N-terminus of Tim23 in the outer mitochondrial membrane [31]. Therefore, Max Harner established GFP-Tim23 as a marker for permanent contact sites between the inner and outer mitochondrial membrane for proteomic studies. However, when performing protease susceptibility assays as controls, he observed that the topology of GFP-Tim23 highly depended on the growth conditions. In particular, at a growth temperature above 30°C, the GFP moiety of GFP-Tim23 was transported across the outer mitochondrial membrane into the intermembrane space, whereas at 25°C, the GFP moiety faced the cytosol [14]. Thus, the competing kinetics for GFP folding and protein translocation were affected differently by the variation of the growth conditions, providing a temperature-dependent topology switch (Fig. 3). Having just re-read a review on the TOM complex by Doron Rapaport [32], I therefore suggested to use the versatility of GFP-Tim23 for studying the potential lateral release of protein segments from the TOM pore. This approach resulted in the discovery that the TOM pore is able to release the hydrophobic transmembrane segments of Tim23, Mim1, and Tom22 into the outer mitochondrial membrane (Fig. 3) [14]: In brief, the N-terminal segment of Tim23 was replaced by a random hydrophilic peptide, fused to GFP, and trapped in the outer mitochondrial membrane at a growth temperature of 25°C. The resulting blockage of the TOM pore (Fig. 3b) was revealed by (1) a severe growth phenotype, (2) a generally impaired protein transport across the TOM complex, and (3) a permanent interaction between Tim23 and the TOM complex. In contrast, when the N-terminus of Tim23 in GFP-Tim23 comprised the hydrophobic transmembrane segment of Tim23, Mim1, or Tom22, the growth and protein transport defects as well as the interaction with the TOM complex were lost, indicative for a lateral release into the outer mitochondrial membrane (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Model of the temperature-dependent topology of GFP-Tim23. a After protein synthesis in the cytosol, the C-terminal transmembrane segments of GFP-Tim23 are inserted into the IM via the TOM/TIM22 pathway. b At a lower temperature (e.g., 25°C), GFP folding is faster than protein import. Thus, depending on the hydrophobicity of the OM-spanning segment, threaded GFP-Tim23 either clogs the TOM pore (b) or is laterally inserted into the membrane (c). d At a higher temperature (e.g., 37°C), GFP does not rapidly adopt a stable tertiary structure. Partially folded or aggregated proteins are pulled into the IMS. e Thus, at a higher temperature, the ratios of the GFP-folding-/aggregation-/import-kinetics favor the import of GFP into the IMS. Noteworthy, at a lower temperature, unfolding of the GFP moiety and subsequent import does not seem to occur (as indicated by the dotted arrow), which is in accordance with the stability of GFP in vitro [1, 12, 13]. f Once located in the IMS, GFP-fusion constructs have enough time to adopt a stable conformation

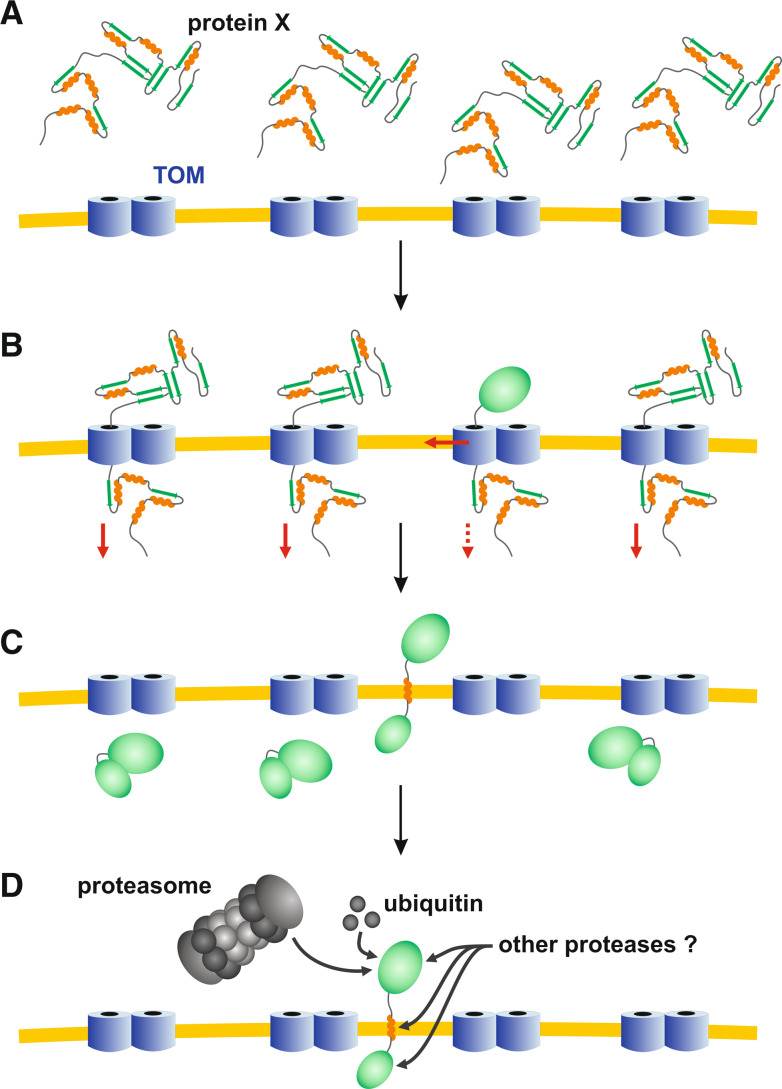

At the current stage, the mechanism and the physiological role of the lateral release from the TOM pore remain to be analyzed in more detail. Two plausible, mutually non-exclusive hypotheses on the physiological relevance are: (1) The TOM complex could indeed act as an insertase for selected outer membrane proteins (in addition to alternative insertion pathways or machineries [20]). (2) The lateral release might be a prerequisite for maintaining the functionality of the TOM complex (Fig. 4): Several proteins are presumably (partially) folded when they enter the TOM pore. Thus, depending on the stability of the folded structure, such proteins could accidentally clog the pore, particularly if they are simultaneously arrested in the matrix, the inner membrane, or in the intermembrane space (e.g., due to chaperone association, membrane insertion, or disulfide bond formation, respectively). A non-specific lateral release of hydrophobic segments would therefore be a kind of rescue mechanism for clogged TOM pores. The released proteins could be subsequently degraded by proteases (e.g., the proteasome [33]) in analogy to the ERAD machinery (Fig. 4). In order to address both hypotheses, GFP tagging of other mitochondrial proteins might be a promising approach.

Fig. 4.

Lateral release as a putative physiological rescue mechanism. a Proteins reach the TOM complex in a partially folded state. b Upon protein translocation some proteins might adopt a stable fold before completion of transport. c A lateral release of (random) hydrophobic peptide segments could immediately rescue such clogged TOM pores. Otherwise, the pore would become non-functional (which might result in the necessity to replace the translocase). d A subsequent quality control of outer membrane proteins coupled to proteolytic degradation could remove the mistargeted proteins. One hypothetical advantage of such a mechanism over a direct proteolytic degradation of proteins that remain stuck in the TOM pore is that other (slowly) imported proteins are not accidentally cleaved

Regarding hypotheses on the mechanism of the lateral release, the TOM pore could be either formed between different Tom40 subunits or at the center of a single beta-barrel structure. In the first scenario, the transmembrane segment is released when the subunits move apart. In the second scenario, lateral release can only occur when the pore-forming beta-barrel partially unfolds [14, 32]. Although the first scenario seems more likely for energetic reasons, the second scenario cannot be excluded. In fact, the long-chain fatty acid transporter FadL in the outer membrane from E. coli provides an example for conformational changes of a beta-barrel protein upon lateral release of a hydrophobic substrate [34].

Whether the membrane insertion of the N-terminus of yeast Tim23 has a functional role for protein translocation remains controversial: While the topology of wild-type Tim23 was shown to depend on the activity of the TIM23 complex [35], anchoring the N-terminus in the outer mitochondrial membrane had no effect on mitochondrial import [14]. Furthermore, in one study, deletion of the N-terminus of yeast Tim23 (1) did not significantly influence the growth phenotype, (2) protein translocation contact sites were still formed, and (3) mitochondrial protein import was just slightly impaired [36], in contrast to a previous study using a similar truncation construct that was C-terminally His-tagged [37]. Noteworthy, potential isofunctional Tim23 homologs from other opisthokonts including Neurospora crassa (accession number AAK26640) and mammals [38, 39] are missing an insertion at the N-terminus. The N-termini of these proteins are therefore probably located in the intermembrane space. A corresponding topology was also found for Tim23 from Arabidopsis thaliana [40]. In summary, if the outer membrane topology of the N-terminus of yeast Tim23 has a functional role, it seems to be rather unique. Nevertheless, GFP-Tim23 is the first example for using the temperature-dependent properties of GFP in order to characterize a translocase. I therefore suggest that GFP tagging could also be suited for the analysis of some of the aforementioned protein transport machineries in other cellular compartments and organisms.

Comparison with other protein tags

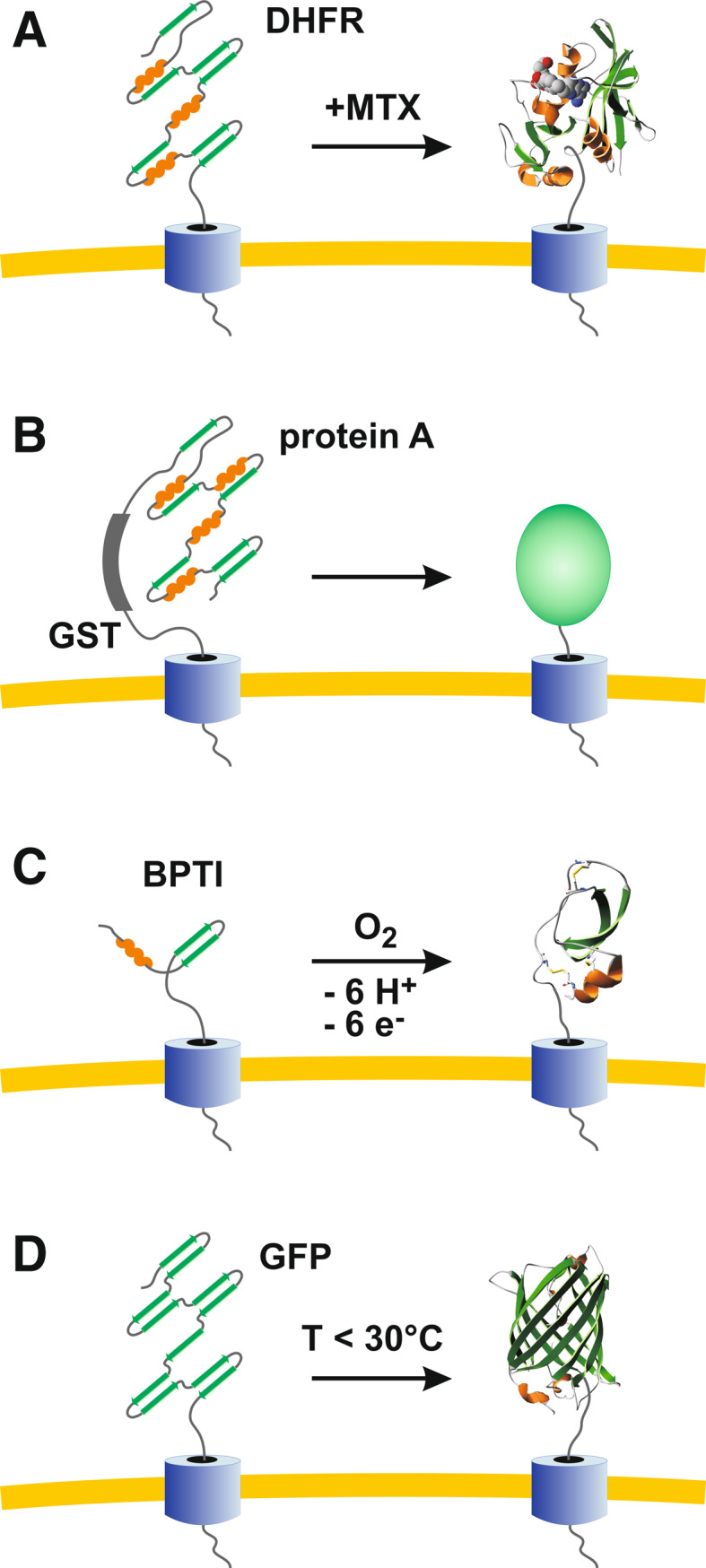

Protein tagging is a common technique for studying protein transport machineries and pathways. In order to analyze the membrane insertion of substrates, it is sometimes necessary to prevent protein translocation across the membrane. This can be achieved by tagging substrates with bulky proteins (Fig. 5). In addition, protein tags are often used to arrest the transport of substrates across membranes at defined stages (e.g., for the analysis of the composition or conformation of a translocase upon import/export). I will therefore discuss the advantages and disadvantages of selected protein tags in the mitochondrial research field and compare them to GFP tagging:

Fig. 5.

Comparison of selected protein tags for the analysis of protein transport machineries by blocking protein translocation. a DHFR tagging is highly flexible owing to reversible, MTX-induced stabilization of the protein [41, 42]. b Protein A-tagging (e.g., in combination with GST tagging) is less flexible but allows efficient purification owing to affinity chromatography [46, 47]. c BPTI tagging requires the formation of disulfide bonds and is therefore restricted to oxidizing compartments or in vitro experiments [48]. d GFP tagging (e.g., in combination with His tagging) is flexible owing to temperature-dependent folding kinetics and does not require expensive ligands

The most frequently used protein tag for studying mitochondrial protein transport is mouse dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) [35, 36, 41–43]. DHFR becomes tightly folded in the presence of methotrexate (MTX) or related compounds such as aminopterin. Accordingly, the transport of DHFR-fusion constructs across membranes is blocked by MTX (Fig. 5a) [41]. A subsequent removal of MTX (e.g., in a pulse-chase experiment) destabilizes DHFR and mitochondrial protein import can continue as long as ATP provides enough energy for protein unfolding and transport [42]. Thus, the most significant advantage of DHFR tagging is the extreme flexibility due to reversible, ligand-induced protein stabilization in vitro and in vivo. However, the prize of MTX or aminopterin can become a disadvantage, particularly for in vivo studies with large cell culture volumes. Furthermore, in addition to the endogenous enzyme of mammalian cells, DHFR is in some organisms (e.g., malaria parasites [29, 30]) the most commonly used selection marker for genetic manipulation. Thus, the application of the DHFR/MTX system for the analysis of protein translocation might become problematic depending on the experimental setup. Alternative ligand-induced systems are, e.g., metallothionein tagging and copper [44] or avidin tagging and biotin [45].

A cost-effective ligand-independent approach is to generate fusion constructs with protein A (Fig. 5b). For example, Norbert Schülke and coworkers applied protein A tagging to zipper mitochondrial protein translocation contact sites in vivo and to subsequently purify the inhibited TOM/TIM23 supercomplex [46, 47]. The biggest advantage of protein A tagging is certainly the IgG-based affinity chromatography, in particular regarding the identification of novel translocase components. However, the approach lacks the flexibility of the DHFR system and can be only controlled at the transcription level. Another ligand-independent method is to genetically tag or chemically cross-link translocase substrates with bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (BPTI) (Fig. 5c). Owing to three intramolecular disulfide bonds, BPTI folding is irreversible in the absence of thiols. Thus, proteins that are tagged with folded BPTI cannot pass the membrane [48]. Since the cytosol is a highly reducing environment, the application of BPTI tagging is restricted to oxidizing compartments or to in vitro import experiments.

GFP tagging and temperature-dependent folding (Fig. 5d) provide a highly flexible system allowing control at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional level without expensive ligands. Depending on the fusion construct, the growth temperature could furthermore facilitate the separate analysis of protein translocation across or protein insertion into a biomembrane (Figs. 2, 3). Thus, GFP tagging is particularly suited for studying bi-functional protein transport machineries. Moreover, folded GFP is highly protease-resistant and therefore allows stable protein tagging in vivo [14]. Noteworthy, the addition of a His-tag to the GFP moiety of fusion constructs does not seem to alter the folding properties of GFP [14]. Such constructs as well as engineered GFP variants with internal tandem tags (composed of a His-tag, a streptavidin-binding peptide tag, and/or a c-Myc tag) can then be used for affinity chromatography [14, 49, 50]. Alternatively, unmodified GFP can be also directly used for affinity chromatography with the help of specific antibodies [50]. Another potential advantage of GFP tagging could be the visualization of protein transport and the quantification of import kinetics based on the chromophore formation. However, the corresponding methodology remains to be established. The biggest disadvantage in comparison to the DHFR system is that folded GFP cannot be easily destabilized again. Thus, the GFP system lacks the reversibility of the DHFR system. In conclusion, GFP tagging could become a valuable tool for studying protein transport machineries in general, extending the application spectrum of one of the most important proteins in science.

Potential future applications and pitfalls of the methodology

Regarding the protein transport machineries depicted in Fig. 2, which components and organisms might be analyzed by GFP tagging in analogy to the yeast TOM complex and GFP-Tim23? To answer this question, the following aspects might be worth considering.

1. The organism, the growth conditions, and the GFP variant: The chosen model system should be susceptible to genetic manipulation. In addition, the establishment of protocols for organelle isolation, protease susceptibility assays and protein import are required. Depending on the selected organism and protein transport machinery, it might be necessary to test other growth conditions than alternative temperatures to obtain the desired GFP topology. If GFP folding is too slow or inefficient, e.g., for mammalian and pathogen cell cultures requiring higher growth temperatures, it might be advantageous to use one of the numerous well-characterized GFP “folding mutants” to determine the optimal experimental conditions [1, 10, 12, 13].

2. The substrate: The identification of a suited substrate for protein transport is an important prerequisite for the methodology. Which substrate can be GFP tagged yielding the required topology without masking import signals or affecting protein stability? Furthermore, if a blockage of the transport process owing to the bulky GFP tag is desired, the import kinetics of the substrate should be similar or slower than the GFP folding kinetics. Hence, GFP-tagged substrates that are co-translationally translocated—e.g., luminal proteins of the endoplasmic reticulum—are presumably inappropriate to study transport machineries such as the Sec translocases. In these cases, substrates with a transmembrane segment/stop-transfer signal are probably a better choice for GFP tagging. With respect to the analysis of the TOM complex, a matrix-targeted substrate might have been disadvantageous for two reasons: First, matrix precursor proteins usually possess fast import kinetics. Second, owing to ATP-powered heat-shock proteins at the import motor, some precursor proteins can be dragged across the TIM23 complex even in a folded state [22, 23, 42]. In contrast, GFP-Tim23 is imported by the TIM22 complex in a motor-independent manner (Fig. 3), and the insertion of the multiple transmembrane segments might slow down the overall import. Noteworthy, not only the TIM23 complex in mitochondria but also the intermembrane space and the stroma of chloroplasts both contain heat-shock proteins [24]. Thus, to analyze the TIM23 complex in mitochondria or the TOC or TIC machineries in chloroplasts, it might be beneficial to attach the GFP moiety to a membrane protein instead of a soluble protein that is targeted to the matrix, the intermembrane space or the stroma, respectively (Fig. 2). Such membrane protein candidates for GFP tagging are, e.g., cytochrome b 2 and d-lactate dehydrogenase in the inner membrane of yeast mitochondria, or Tic110, Tic20, and APG1 in the inner envelope of chloroplasts.

3. The linker and the transmembrane domain: A potential lateral release or clogging of the transport machinery requires a protein segment that is able to either span the translocation pore or to insert into the surrounding membrane. Thus, the addition or replacement of a transmembrane segment or a linker sequence between the substrate and the GFP moiety can be necessary. In some cases, it might be essential to elongate the linker sequence, for example, if two complexes or membranes are joined by the construct in analogy to the TIM23/TOM supercomplex, e.g., for tethering TIC/TOC or Sec/BAM in the inner/outer membrane of chloroplasts or Gram-negative bacteria, respectively. Please note that the length and the composition of the linker also influence the import kinetics and the stability of the fusion construct (unpublished observations). Concerning the origin of the transmembrane segment, it is advantageous to insert transmembrane segments from natural substrates of the investigated transport machinery if available. Furthermore, the orientation of the segment inside the membrane should match the desired topology of the fusion construct. Noteworthy, some translocases—such as the Tat system in prokaryotes and chloroplasts, or the transient translocation pore of peroxisomes—are able to transport folded and bulky substrates and therefore cannot be blocked by a GFP tag.

General implications for GFP studies

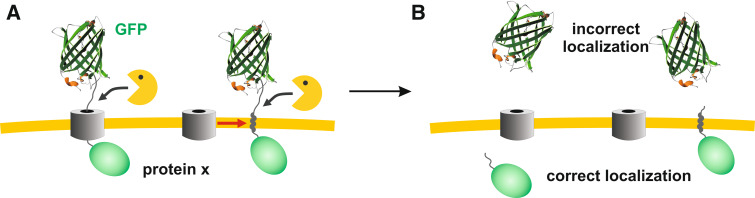

For most GFP applications, a correct subcellular or even suborganellar localization of the protein is crucial. Thus, in order to determine a protein–protein interaction, the Ca2+ concentration, the pH value or the redox potential with the help of GFP, the protein has to reach the expected compartment within the cell. Since negative results usually remain unpublished, it is difficult to estimate how often GFP ends up in the wrong compartment. My impression from numerous personal communications is that the aforementioned experiments are far more often dubious (or even fail) than expected. A semi-quantitative estimation from the mitochondrial research field might exemplify my impression: Two global localization analyses of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteome were performed using either epitope-tagged proteins [51] or C-terminally GFPS65T-tagged proteins [52]. Subsequent integrative analyses of the mitochondrial proteome confirmed the results of both studies to a large extent, but also revealed that some data are ambiguous. Moreover, roughly 25% of the expected mitochondrial proteins in yeast could not have been annotated at all [53]. One plausible reason for some of the observed discrepancies is the usage of protein tags masking localization signals or inhibiting protein translocation across membranes, for example, if the chosen experimental conditions affect the ratio between the GFP folding and protein transport kinetics. In fact, the TOM complex was blocked by a wild-type-like GFP variant [14] containing Thr65 for a simplified and increased fluorescence and the “innocuous” mutation Arg80 [1]. Mutations reducing the aggregation rate and/or increasing the folding rate [1, 13] were absent in GFP-Tim23. Such a GFP variant was also used in the global localization study [52]. Since GFP folding was faster at 25°C than the import of the GFP moiety of GFP-Tim23 (Fig. 3), I assume that some other GFP-fusion constructs of global localization studies also never pass the TOM pore or other translocases with comparable properties and kinetics. If such fusion constructs are partially degraded, the protease-resistant GFP moiety will result in a cytosolic signal and the protein will be incorrectly annotated (Fig. 6). Moreover, if targeted GFP-fusion constructs are used as sensors under conditions that favor the GFP folding kinetics over the protein transport kinetics, the measured redox potential, pH value, Ca2+ concentration, or protein interaction might be averaged from different subcellular compartments. I therefore suggest to determine the localization (and topology) of GFP-tagged proteins at alternative growth conditions including, e.g., the medium composition and the growth temperature. Such controls will reveal whether the ratio between the GFP folding and transport kinetics is affected by the chosen experimental conditions. The approach could be valuable in determining the correct localization and topology of proteins in yeast and other organisms and in solving or avoiding conflicting data obtained by GFP tagging.

Fig. 6.

Potential pitfall using GFP tagging. a Premature folding of GFP-tagged proteins before complete protein translocation might result in membrane-spanning constructs in analogy to GFP-Tim23 (Fig. 3). Such constructs could then be susceptible to endogenous proteases. b The tightly folded GFP moiety, which is highly protease-resistant, subsequently ends up in the wrong compartment, leading, for example, to a cytosolic GFP signal of a mitochondrial protein

Acknowledgments

I thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) for financial support of my work on mitochondrial protein transport (Grant DE 1431/2). I would also like to thank Max Harner for his extraordinary work on the TOM complex.

References

- 1.Tsien RY. The green fluorescent protein. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:509–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmer M. Green fluorescent protein (GFP): applications, structure, and related photophysical behavior. Chem Rev. 2002;102(3):759–781. doi: 10.1021/cr010142r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giepmans BN, Adams SR, Ellisman MH, Tsien RY. The fluorescent toolbox for assessing protein location and function. Science. 2006;312(5771):217–224. doi: 10.1126/science.1124618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llopis J, McCaffery JM, Miyawaki A, Farquhar MG, Tsien RY. Measurement of cytosolic, mitochondrial, and Golgi pH in single living cells with green fluorescent proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(12):6803–6808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuyama S, Llopis J, Deveraux QL, Tsien RY, Reed JC. Changes in intramitochondrial and cytosolic pH: early events that modulate caspase activation during apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(6):318–325. doi: 10.1038/35014006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjornberg O, Ostergaard H, Winther JR. Measuring intracellular redox conditions using GFP-based sensors. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8(3–4):354–361. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gutscher M, Pauleau AL, Marty L, Brach T, Wabnitz GH, Samstag Y, Meyer AJ, Dick TP. Real-time imaging of the intracellular glutathione redox potential. Nat Methods. 2008;5(6):553–559. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer AJ, Dick TP. Fluorescent protein-based redox probes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13(5):621–650. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ostergaard H, Henriksen A, Hansen FG, Winther JR. Shedding light on disulfide bond formation: engineering a redox switch in green fluorescent protein. EMBO J. 2001;20(21):5853–5862. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.5853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craggs TD. Green fluorescent protein: structure, folding and chromophore maturation. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38(10):2865–2875. doi: 10.1039/b903641p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reid BG, Flynn GC. Chromophore formation in green fluorescent protein. Biochemistry. 1997;36(22):6786–6791. doi: 10.1021/bi970281w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuda H, Arai M, Kuwajima K. Folding of green fluorescent protein and the cycle3 mutant. Biochemistry. 2000;39(39):12025–12032. doi: 10.1021/bi000543l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu ST, Blaser G, Jackson SE. The folding, stability and conformational dynamics of beta-barrel fluorescent proteins. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38(10):2951–2965. doi: 10.1039/b908170b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harner M, Neupert W, Deponte M. Lateral release of proteins from the TOM complex into the outer membrane of mitochondria. EMBO J. 2011;30(16):3232–3241. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalbey RE, Wang P, Kuhn A. Assembly of bacterial inner membrane proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:161–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060409-092524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimmermann R, Eyrisch S, Ahmad M, Helms V. Protein translocation across the ER membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808(3):912–924. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robinson C, Matos CF, Beck D, Ren C, Lawrence J, Vasisht N, Mendel S. Transport and proofreading of proteins by the twin-arginine translocation (Tat) system in bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808(3):876–884. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Funes S, Kauff F, van der Sluis EO, Ott M, Herrmann JM. Evolution of YidC/Oxa1/Alb3 insertases: three independent gene duplications followed by functional specialization in bacteria, mitochondria and chloroplasts. Biol Chem. 2011;392(1–2):13–19. doi: 10.1515/BC.2011.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hagan CL, Silhavy TJ, Kahne D. β-Barrel membrane protein assembly by the Bam complex. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:189–210. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061408-144611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dukanovic J, Rapaport D. Multiple pathways in the integration of proteins into the mitochondrial outer membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808(3):971–980. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sommer MS, Daum B, Gross LE, Weis BL, Mirus O, Abram L, Maier UG, Kuhlbrandt W, Schleiff E. Chloroplast Omp85 proteins change orientation during evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(33):13841–13846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108626108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chacinska A, Koehler CM, Milenkovic D, Lithgow T, Pfanner N. Importing mitochondrial proteins: machineries and mechanisms. Cell. 2009;138(4):628–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Endo T, Yamano K. Multiple pathways for mitochondrial protein traffic. Biol Chem. 2009;390(8):723–730. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schleiff E, Becker T. Common ground for protein translocation: access control for mitochondria and chloroplasts. Natl Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12(1):48–59. doi: 10.1038/nrm3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bagola K, Mehnert M, Jarosch E, Sommer T. Protein dislocation from the ER. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808(3):925–936. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meinecke M, Cizmowski C, Schliebs W, Kruger V, Beck S, Wagner R, Erdmann R. The peroxisomal importomer constitutes a large and highly dynamic pore. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(3):273–277. doi: 10.1038/ncb2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bleves S, Viarre V, Salacha R, Michel GP, Filloux A, Voulhoux R. Protein secretion systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a wealth of pathogenic weapons. Int J Med Microbiol. 2010;300(8):534–543. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simeone R, Bottai D, Brosch R. ESX/type VII secretion systems and their role in host-pathogen interaction. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12(1):4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Koning-Ward TF, Gilson PR, Boddey JA, Rug M, Smith BJ, Papenfuss AT, Sanders PR, Lundie RJ, Maier AG, Cowman AF, Crabb BS. A newly discovered protein export machine in malaria parasites. Nature. 2009;459(7249):945–949. doi: 10.1038/nature08104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spork S, Hiss JA, Mandel K, Sommer M, Kooij TW, Chu T, Schneider G, Maier UG, Przyborski JM. An unusual ERAD-like complex is targeted to the apicoplast of Plasmodium falciparum. Eukaryot Cell. 2009;8(8):1134–1145. doi: 10.1128/EC.00083-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vogel F, Bornhovd C, Neupert W, Reichert AS. Dynamic subcompartmentalization of the mitochondrial inner membrane. J Cell Biol. 2006;175(2):237–247. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rapaport D. How does the TOM complex mediate insertion of precursor proteins into the mitochondrial outer membrane? J Cell Biol. 2005;171(3):419–423. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karbowski M, Youle RJ. Regulating mitochondrial outer membrane proteins by ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23(4):476–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hearn EM, Patel DR, Lepore BW, Indic M, van den Berg B. Transmembrane passage of hydrophobic compounds through a protein channel wall. Nature. 2009;458(7236):367–370. doi: 10.1038/nature07678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Popov-Celeketic D, Mapa K, Neupert W, Mokranjac D. Active remodelling of the TIM23 complex during translocation of preproteins into mitochondria. EMBO J. 2008;27(10):1469–1480. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chacinska A, Rehling P, Guiard B, Frazier AE, Schulze-Specking A, Pfanner N, Voos W, Meisinger C. Mitochondrial translocation contact sites: separation of dynamic and stabilizing elements in formation of a TOM-TIM-preprotein supercomplex. EMBO J. 2003;22(20):5370–5381. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donzeau M, Kaldi K, Adam A, Paschen S, Wanner G, Guiard B, Bauer MF, Neupert W, Brunner M. Tim23 links the inner and outer mitochondrial membranes. Cell. 2000;101(4):401–412. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80850-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishihara N, Mihara K. Identification of the protein import components of the rat mitochondrial inner membrane, rTIM17, rTIM23, and rTIM44. J Biochem. 1998;123(4):722–732. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bauer MF, Gempel K, Reichert AS, Rappold GA, Lichtner P, Gerbitz KD, Neupert W, Brunner M, Hofmann S. Genetic and structural characterization of the human mitochondrial inner membrane translocase. J Mol Biol. 1999;289(1):69–82. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murcha MW, Lister R, Ho AY, Whelan J. Identification, expression, and import of components 17 and 23 of the inner mitochondrial membrane translocase from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003;131(4):1737–1747. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.016808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eilers M, Schatz G. Binding of a specific ligand inhibits import of a purified precursor protein into mitochondria. Nature. 1986;322(6076):228–232. doi: 10.1038/322228a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eilers M, Hwang S, Schatz G. Unfolding and refolding of a purified precursor protein during import into isolated mitochondria. EMBO J. 1988;7(4):1139–1145. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rassow J, Guiard B, Wienhues U, Herzog V, Hartl FU, Neupert W. Translocation arrest by reversible folding of a precursor protein imported into mitochondria. A means to quantitate translocation contact sites. J Cell Biol. 1989;109(4 Pt 1):1421–1428. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.4.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen WJ, Douglas MG. The role of protein structure in the mitochondrial import pathway. Unfolding of mitochondrially bound precursors is required for membrane translocation. J Biol Chem. 1987;262(32):15605–15609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Endo T, Nakayama Y, Nakai M. Avidin fusion protein as a tool to generate a stable translocation intermediate spanning the mitochondrial membranes. J Biochem. 1995;118(4):753–759. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schulke N, Sepuri NB, Gordon DM, Saxena S, Dancis A, Pain D. A multisubunit complex of outer and inner mitochondrial membrane protein translocases stabilized in vivo by translocation intermediates. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(32):22847–22854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schulke N, Sepuri NB, Pain D. In vivo zippering of inner and outer mitochondrial membranes by a stable translocation intermediate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(14):7314–7319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vestweber D, Schatz G. A chimeric mitochondrial precursor protein with internal disulfide bridges blocks import of authentic precursors into mitochondria and allows quantitation of import sites. J Cell Biol. 1988;107(6 Pt 1):2037–2043. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kobayashi T, Morone N, Kashiyama T, Oyamada H, Kurebayashi N, Murayama T. Engineering a novel multifunctional green fluorescent protein tag for a wide variety of protein research. PLoS One. 2008;3(12):e3822. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhuang R, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Song C, Yang K, Yang A, Jin B. Purification of GFP fusion proteins with high purity and yield by monoclonal antibody-coupled affinity column chromatography. Protein Expr Purif. 2008;59(1):138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kumar A, Agarwal S, Heyman JA, Matson S, Heidtman M, Piccirillo S, Umansky L, Drawid A, Jansen R, Liu Y, Cheung KH, Miller P, Gerstein M, Roeder GS, Snyder M. Subcellular localization of the yeast proteome. Genes Dev. 2002;16(6):707–719. doi: 10.1101/gad.970902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huh WK, Falvo JV, Gerke LC, Carroll AS, Howson RW, Weissman JS, O’Shea EK. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature. 2003;425(6959):686–691. doi: 10.1038/nature02026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prokisch H, Scharfe C, Camp DG, 2nd, Xiao W, David L, Andreoli C, Monroe ME, Moore RJ, Gritsenko MA, Kozany C, Hixson KK, Mottaz HM, Zischka H, Ueffing M, Herman ZS, Davis RW, Meitinger T, Oefner PJ, Smith RD, Steinmetz LM. Integrative analysis of the mitochondrial proteome in yeast. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(6):e160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]