Abstract

Various intracellular organelles, such as lysosomes, mitochondria, nuclei, and cytoskeletons, change during replicative senescence, but the utility of these changes as general markers of senescence and their significance with respect to functional alterations have not been comprehensively reviewed. Furthermore, the relevance of these alterations to cellular and functional changes in aging animals is poorly understood. In this paper, we review the studies that report these senescence-associated changes in various aging cells and their underlying mechanisms. Changes associated with lysosomes and mitochondria are found not only in cells undergoing replicative or induced senescence but also in postmitotic cells isolated from aged organisms. In contrast, other changes occur mainly in cells undergoing in vitro senescence. Comparison of age-related changes and their underlying mechanisms in in vitro senescent cells and aged postmitotic cells would reveal the relevance of replicative senescence to the physiological processes occurring in postmitotic cells as individuals age.

Keywords: Replicative senescence, Postmitotic cell, Aging, Fibroblast, Lysosomes, Mitochondria, Senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF), Telomere dysfunction-induced focus (TIF)

Introduction

Replicative senescence is defined as a state where normal somatic cells lose their replicative capacity in vitro after prolonged division in culture, an occurence which results in irreversible growth arrest. Normal somatic cells, such as fibroblasts, endothelial cells, keratinocytes, chondrocytes, and lymphocytes, commonly have low telomerase activity, and it is thought that the shortened and unprotected telomeres accompanying the serial cell divisions and subsequent DNA damage response are responsible for replicative senescence [1]. In addition to losing the ability to divide, cells in the senescent state exhibit dramatic alterations in morphology, mass, and dynamics of their subcellular organelles, and thereby display structural and functional differences compared to proliferating cells. These differences include an enlarged and flat cellular morphology, increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and the accumulation of resultant ROS-mediated damage products such as: (1) lipofuscins and granular particles, (2) altered mass and functionality of mitochondria and lysosomes, and (3) certain cytosolic and nuclear markers such as senescence associated-β-galactosidase activity (SA-β-Gal) and senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF). These phenotypic changes are frequently taken as indications for cellular senescence, but detailed underlying mechanisms and their close relevance to senescence have only recently been discussed (e.g., [2]).

Normal somatic cells also enter a state of senescence upon overexpression of oncogenic Ras or Raf protein (oncogene-induced senescence) [3, 4]. This phenomenon implies that some oncogenes may have paradoxical functions of inducing irreversible growth arrest (i.e., senescence) in addition to their cell-transforming ability, probably depending on the cellular and molecular environments. The majority of human cancer cells possess high telomerase activity and strong proliferation capacity, but can also be destined to a state of senescence when exposed to certain levels of oxidative stress or DNA damaging assaults [5]. These observations lead to speculation that tumorigenesis includes a process to overcome the senescence barrier raised by the activation of oncoproteins or other cellular environmental stresses. Indeed, cells expressing senescence phenotypes are often detected in tumor masses of animals, thus supporting the notion that cellular senescence is a spontaneous organismal defense mechanism against tumor progression [6]. However, the possibility that any of the senescence phenotypes that develop during tumorigenesis may contribute positively to cancerous activity cannot be excluded [7].

Other than its prominent role in tumor suppression, the physiological relevance of cellular senescence in aging is only supported in a limited number of cases (for example, senescent cells are found in the vascular endothelium of aged individuals [8]) despite substantial progress made on mechanisms underlying senescence. Certain senescence phenotypes have been observed in aged human tissues, but its generality, reproducibility, and its relevance to aging has been questioned [8]. Some of the senescence phenotypes, including SA-β-Gal activity, cell enlargement, and increased fibronectin expression, have been found in human tissues, but most were in the cells of certain disease conditions related to aging. Examples include fibroblasts cultured from a venous ulcer biopsy [9], endothelial cells from an atherosclerotic coronary artery [10], and cultured chondrocytes taken from sites near osteoarthritis [11]. Moreover, a decreased proliferation capacity of fibroblasts during human aging has been reported [12, 13], but this finding is also challenged by the observation that young- and centenarian-explanted fibroblasts have similar proliferation capacities and responses to growth factors [14, 15]. Therefore, current consensus is that cellular senescence (or senescence phenotypes), as defined in vitro, may not represent what is taking place during the aging process in situ of the human body. It is expected, however, that future technical advancements will help correctly define senescent cells in vivo, and promote a better understanding on the cell biological aging process. It is noteworthy that, by using a novel technique [telomere dysfunction-induced focus (TIF), see below], an accumulation of cells with features indicative of cellular senescence was found in mitotic but not in postmitotic tissues of baboons of advanced age [16].

Normal somatic cells have long been employed by researchers studying aging due to their easy availability for in vitro experiments and their applicability for senescence-associated growth control. Consequently, most senescence phenotypes reported to date were from in vitro mitotic cells. Although these cells are the preferred system to explore the mechanisms involved in the senescence-linked irreversible growth arrest, they may not be suitable for the elucidation of mechanisms underpinning other progressive changes that occur during aging. Meanwhile, nearly all postmitotic cells do not divide, i.e., regenerate, after reaching maturity and would survive as long as the host organism is alive. This means that the age of an isolated postmitotic cell is likely similar to that of the donor, and the changes that took place in the cell would be preserved without being diluted by cell division. Therefore, both passive and active changes would be more dramatic and representative in postmitotic cells. However, the phenotypic changes occurring in postmitotic cells during aging have not been vigorously explored, let alone the molecular mechanisms occurring during this process, probably because of their intrinsic incapability to proliferate.

In this paper, we attempted to review most of major publications reporting changes in whole cells or subcellular organelles associated with replicative senescence (or senescence induced by either oncogenic stimulation or exogenous stresses), and hope to provide a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the expression of certain senescence-associated traits. The traits of somatic cells undergoing replicative senescence were compared to those of the postmitotic cells from aged individuals, though available information is limited. Efforts were made to cover the major cellular changes such as: (1) change in cell volume and morphology, (2) cytoskeleton-mediated changes, and (3) alterations associated with subcellular organelles such as lysosomes, mitochondria, and nuclei. Even though these changes are well recognized as a ‘general trait’ of senescence, it is clear that not all studies agree in regard to the phenomenon itself nor its underlying mechanisms.

More specifically, this review focused mainly on four different types of cells, namely, cells undergoing or in replicative senescence (in this review, referred to as senescent cells), normal or cancer cells induced to senescence (by oncogenic Ras in normal cells and by oxidative stress or DNA damage in cancer cells), fibroblasts isolated in aged individuals, and postmitotic cells in tissue from old individuals.

Cell volume

One of the most pronounced morphological changes occurring in cellular senescence of fibroblasts is an increase in cell surface area (Figs. 1, 3). In human fetal fibroblasts, the cell surface area measured in one study is fairly homogeneous at less than 1,000 μm2 at early passages, while that of the cells at their terminal stages of in vitro life span is large and extremely heterogeneous (ranging from 1,000 to 9,000 μm2) [17]. Fibroblasts also change their morphology from small spindle-fusiform to large flat spread, and the increase in the surface area is therefore attributed in part to changes in the cytoskeleton. There is also a marked increase in the volume of fibroblasts undergoing senescence [18, 19]. Various cancer cells undergoing DNA damage-induced senescence also experience a dramatic enlargement ([20]; and Fig. 1a). These increases in volume are usually about fourfold [21, 22]. For example, under normal conditions, the volume of most early passage IMR-90 fibroblasts is less than 1 × 10−5 mm3; however, that of the cells undergoing replicative senescence or H2O2-induced senescence ranges from 4 to 7 × 10−5 mm3 [21].

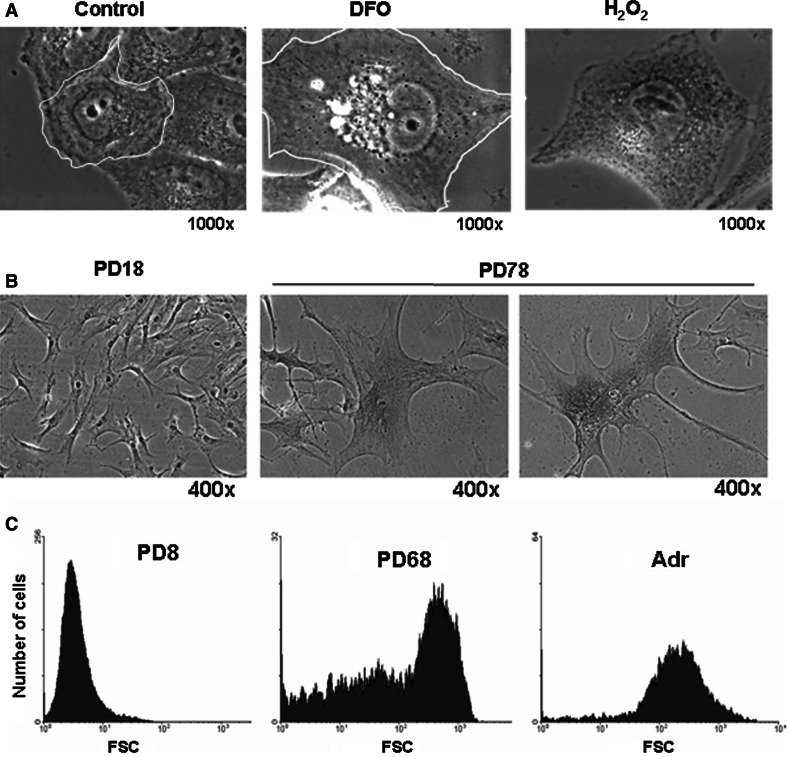

Fig. 1.

Increase in cell size during senescence. a Senescence was induced by exposing Chang cells to 200 μM deferoxamine (DFO) or H 2 O 2 for 3 days as in [100]. Phase contrast images were obtained and the margin of a single cell was outlined. b Replicative senescence was developed by serial passage of human fibroblasts obtained from the foreskin of a 5-year-old boy. Numbers of population doublings are indicated. Two smaller cells are located next to a larger one (middle panel). c Early passage (PD8) and senescent (PD68) human fibroblasts derived from the foreskin of a new-born as well as the early passage fibroblasts induced to senesce by treatment with 0.5 μM adriamycin [203] were trypsinized and subjected to FACS analysis. Cell distribution was plotted against forward scattering (FSC; x axis). While the cells induced to senesce by adriamycin treatment show rather homogenous FSC, the cells undergoing replicative senescence show high heterogeneity in FSC

Fig. 3.

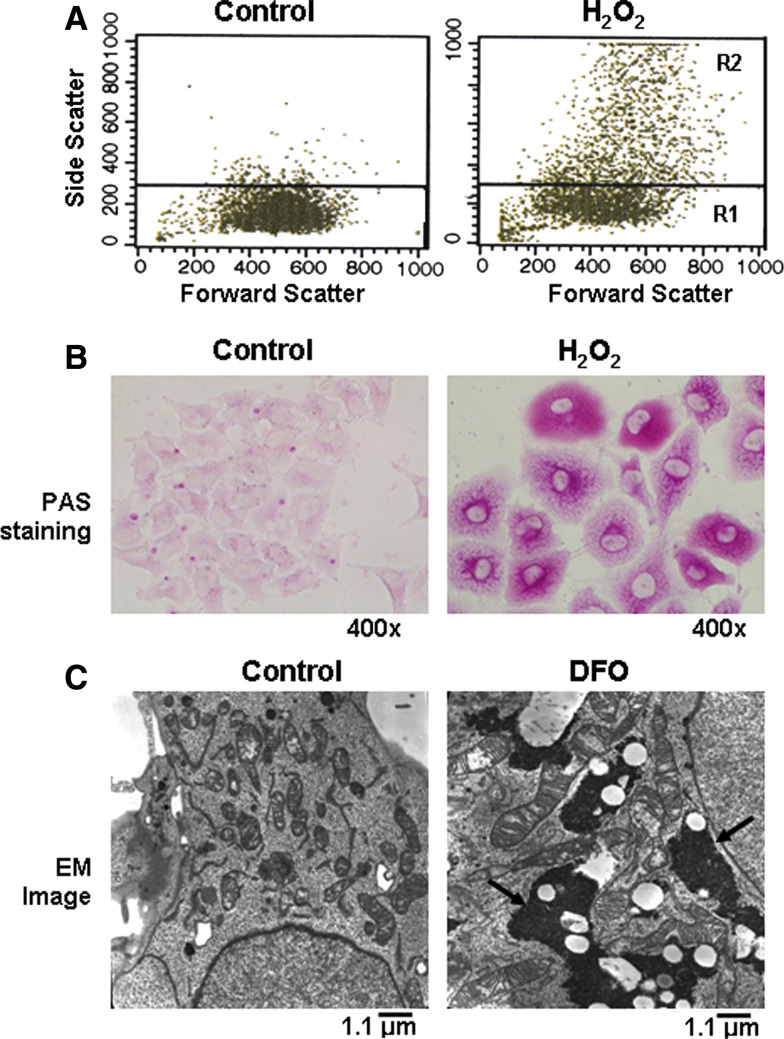

Increase of cellular granularity (granule content) and glycogen particles. Chang cells were exposed to 200 μM DFO or H2O2 for 3 days to induce senescence. a Cells were subjected to FACS analysis to assess their granularity and cell distribution was plotted for FSC (x axis) and SSC (y axis). b Glycogen accumulation was demonstrated by staining cells with periodic acid schiff (PAS) reagent. c Glycogen particles in the cytosol were visualized by electron microscopy. Dense spots (arrows) indicate glycogen particles

As a culture of primary fibroblasts goes through repeated passages, the population doubling is progressively delayed while the number of cells with a larger volume steadily increases. It is widely accepted that individual cells in a culture enter replicative senescence at different time points and that this varied timing contributes to a steady decrease in the rate of population doubling and a similar increase in mean size of the cells. The heterogeneity of cell volumes that is displayed in a population of cells which has reached the end of their proliferation capacity is an intriguing phenomenon. When cultured human fibroblasts at early passage are subjected to FACS analysis, forward scattering (FSC), which indicates cell size, gives rise to a single sharp peak at a low value. FSC of cells in late-passage culture, however, yield a broad shoulder with a small peak of a high value instead of two peaks (a small one with a low value and another with a high value) (Fig. 1c). This heterogeneity, however, is less prominent in fibroblasts undergoing adriamycin-induced senescence where growth arrest would occur simultaneously in all the cells of the culture (Fig. 1c). This suggests that the heterogeneity may be related to differences in the timing of growth-arrest pathway-activation, an event driven by the DNA damage signaling triggered by the shortening of telomeres [23, 24]. As has been proposed, the difference in telomere shortening rate in individual cells may cause differences in the timing of DNA damage signaling being triggered [23]. It still remains unanswered, however, why the cells have different sizes. As individual cells continue to proliferate, they may steadily divide at lower rates with continuous enlargement until they reach a terminal phase of proliferation. Or, individual cells that have been dividing at a rather constant rate may suddenly arrest and start to enlarge for some time, and therefore, depending on whether or not they are in the irreversible arrest state, the cell volumes may become different. The former is not a highly likely possibility since cells are known to have a so-called size check point function, a cell size-sensing mechanism, ensuring that a cell maintain a constant volume [35], although it is not known whether this function is intact throughout the cellular lifespan. It was also reported that cells with a larger volume generally return to their initial size within a cell cycle [36]. Meanwhile, Blagosklonny [25] speculated on a reason for the increased volume of senescent cells in favor of the latter possibility. In growth factor-induced cell proliferation, both cell cycle progression and macromolecule synthesis are required. A major regulator for cellular protein synthesis is mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which, upon activation, phosphorylates eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) to allow formation of a translation initiation complex at cap-containing mRNA [26]. The expression of a phosphorylation-defective mutant of 4E-BP1, which is able to constitutively bind to eIF4E, causes a decrease in cell size, demonstrating the importance of this pathway in maintaining proper cell size [27]. In quiescence, a state where the cell cycle is arrested at G0 phase, the absence of mitogen shuts down both the cell cycle progression and protein synthesis, and cell cycle arrest is therefore coordinated with the cessation of new macromolecular production. Blagosklonny speculates, however, that, during senescence, which occurs in the presence of mitogen, mTOR activity is high and so is protein synthesis [41]. As a consequence, cell protein content as well as the volume would increase. This is a plausible explanation, and there are papers that report on an upregulated activity of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), an upstream activator of mTOR, independently of the growth-inhibitory pathway in fibroblasts undergoing premature senescence after exposure to H2O2 [28, 29]. There is also evidence indicating that the rate of protein synthesis is lower in senescent cells [30]. For instance, Razin et al. [31] compared the rates of incorporation of the radio-labeled precursors of DNA, RNA, protein, and lipids and found that all declined in senescent WI-38 fibroblasts. In addition, mitogen signaling may not be intact in cellular senescence [32]. It seems clear that more systematic studies are needed to determine why cells increase in size and why that happens heterogeneously as cells approach the terminal state of proliferation.

In primary fibroblasts and postmitotic cells isolated from aged donors, increased cell volume and surface area are also seen. Fibroblast culture derived from a 66-year-old donor (as compared to an 8-week-old) has a greater percentage of cells with higher surface area at the initial period of in vitro culture [33]. A more than twofold increase in the volume, and similar but less pronounced increases in protein content during aging were found in hepatocytes isolated from BN/BiRij rats [34]. The important question as to why the volume of postmitotic cells increases has not been adequately addressed. Many earlier studies carried out during the 1970s and 1980s suggested an age-related slow down in the rates of RNA and bulk protein synthesis in aged fruit fly, Caenorhabditis elegans, rats, and various human tissues [35–37]. Therefore, protein synthesis in the postmitotic cells of aged organisms is expected to be low. As expected from the change in replicative senescence of fibroblasts, the increased protein content (and cell volume) in cells from old animals may also in large part be attributed to a decrease in the rate of protein degradation. However, there are also reports showing either no change or even an increase in protein synthesis in tissues during aging [34].

Cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton functions in the formation and maintenance of cell morphology, intracellular trafficking, polarity, motility, and division. Because senescent cells cease to divide and have marked changes in morphology, motility, and mechanical strength, the integrity of cytoskeletons is expected to be modified in not only the structure but also the compositional protein levels and signaling mediated by them.

Intermediate filaments

Among many cytoskeletal proteins, quantitative and structural changes of an intermediate filament protein, vimentin, are most prominently found in many different types of senescent cells and aged tissues. In senescent fibroblasts derived from skin, lung, and gingiva of humans, the amount of the 57-kDa vimentin protein is found at much higher level than that in actively growing early-passaged fetal or immortalized fibroblasts [38]. In late-passage fibroblasts, vimentin filaments form thick, long and dense bundles that transverse from one end of the cell to the other, while they form irregular and small fur-like networks of thin and short filaments in cells at early passage [33, 38]. Interestingly, overexpression of EGFP-tagged vimentin in the early-passage cells induces formation of long-bundled vimentin filaments and enlarged and non-uniform cell shapes similar to that of the cells in senescent culture [38]. These changes suggest that the increased level of vimentin plays a causative role in determining senescent morphology, a hypothesis that needs further confirmation with other cell types. Meanwhile, overexpression of vimentin in transformed BHK cells (hamster kidney cell line) caused a morphological change (from round to flat and elongated shape) and reversion of the transformed phenotype to that of normal BHK without affecting cell growth [39]. Therefore, vimentin level is most likely associated with the morphological change but not with the altered growth property of the senescent cells. It is of interest to determine whether senescent fibroblasts in which vimentin expression is knocked down are still able to exhibit the flat and large cell morphology. It is worth pointing out that primary embryo fibroblasts from vimentin-knockout mice underwent replicative senescence at a much earlier passage than did normal MEF [40], suggesting a protective function of vimentin against certain damage that induces senescence independent of telomere shortening. This result may also indicate the importance of a fine balance in the level of vimentin protein.

Vimentin is also known to play an important role in cell motility. In senescent fibroblasts, vimentins are responsible for limited locomotion of senescent fibroblasts because of large bundles of thick and crossed-bridged filaments [33]. Interestingly, vimentin overexpression caused an enhanced migration of breast cancer cells [41], indicating that a higher level of vimentin does not necessarily cause the reduced motility of senescent cells. Meanwhile, the question as to why vimentin is upregulated in senescent cells has not been adequately addressed. The vimentin promoter is activated by NF-kB [42], and it is therefore possible that NF-kB, which is generally activated during cellular senescence [43], causes an increase in vimentin expression.

A similar increase in vimentin has not been reported in primary fibroblasts or postmitotic cells isolated from old animals or aged human subjects. An increase in vimentin levels has been observed in tissues such as testis tubules of old subjects [44], and astrocytes [45] and articular disc cells [46] of old rats. Vimentin is vulnerable to modification by advanced glycation endproduct (AGE) as evidenced by glycated vimentin that was found to form an abundance of perinuclear aggresomes in skin fibroblasts [47]. Furthermore, vimentin accumulation is associated with cataract appearance [48], and likewise, higher levels of vimentin or glycated vimentin may contribute to certain aging-associated pathological conditions.

Actin filaments

Since actin stress fiber is a key factor determining cell shape and motility, a change in its abundance and localization may be causatively related to the enlarged and round shape as well as the decreased motility of senescent fibroblasts. The status of actin filaments has been reported to change during replicative senescence as well as during aging, but the findings are mostly based on simple microscopic observation not supported by quantitative data and, in some cases, contradictory to each other. In IMR-90 human lung fibroblasts undergoing replicative or H2O2-induced senescence, no significant change in actin protein level was observed, but actin stress fibers were visually thicker transversing the large cell body [21]. Meanwhile, in other studies, the actin protein level (detected by the same antibody) was substantially reduced in senescent fibroblasts [49] and the foreskin of aged individuals [50]. In addition, actin stress fibers were fewer and thinner and mostly localized close to the cell periphery in senescent fibroblasts [49] and in the fibroblasts from Achilles tendon of 24-month-old mice [51]. Although the reason for this discrepancy is unclear, attention should be drawn to the possibility that actin isoforms may be regulated differently in different tissues and at different ages [52]. Because genes in skin are subject to hormonal regulation that changes substantially throughout life and under various physiological conditions, a simple comparison of two age groups (i.e., young vs. old) may not be adequate to claim a change during aging, and better-controlled studies are warranted for establishing the status of actin filaments in aging.

Meanwhile, nuclear accumulation of G-actin as well as dephosphorylated (active) cofilin, an actin depolymerizing factor, in senescent fibroblasts and certain cancer cells were reported [53]. Nuclear actin accumulation is also found in cells under stresses such as heat shock, ATP-depletion, DMSO treatment, and during certain disease conditions [54]. At present, whether cellular senescence shares a common mechanism with these various stress conditions is not known. Interestingly, treatment with 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA), also known as phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), a strong activator of protein kinase C, whose activity has been reported to be low in senescent fibroblasts [55], caused nuclear export of actin molecules and resumption of DNA synthesis, suggesting the reversion of the senescence phenotype. Since similar nuclear accumulation of G-actin was observed in non-senescent conditions [54], however, this is likely due to an event accompanying growth arrest rather than senescence.

Microtubules

Microtubules control various cellular functions including cell division, polarity, and intracellular transport, which are in general altered during senescence and aging. Wang and Gundersen [17] showed that, accompanied by the increase in intermediate filament, microtubules increase in abundance during senescence with some cells containing an increased number of microtubule organizing center (MTOC), the site of microtubule nucleation. Despite these findings, the molecular mechanism and function of the microtubule abundance during cellular senescence remain undefined. Tubulin polymerization can be driven by an increase in the size of the unpolymerized monomer pool, but there no report has been found describing an increase in tubulin expression in senescent or aged cells. In fact, some studies reported the opposite [49, 50]. To date, the impact of these changes in microtubules on intracellular trafficking of various organelles and materials has not been well established. The presence of multiple MTOC was poorly documented and not well explained, and it could be simply the consequence of the absence of cell division in the presence of active synthesis of proteins and cellular organelles.

Cell adhesion

Senescent fibroblasts migrate poorly and are less readily detached from culture substratum. In addition to a larger surface area, other factors appear to be involved in this stronger substrate adhesion of cells at senescence. In actively proliferating fibroblasts, adhesion foci containing vinculin and paxillin preferentially localize at the edge, but they are heavily localized in the cytoplasm of senescent and senescence-induced IMR-90 fibroblasts [21]. Because increased vinculin foci contributes to the increase in cell surface area [56, 57], this may provide insight into why senescent cells appear flattened. No significant increase was found in the level of these proteins in senescent cells suggesting that some other mechanisms, rather than the mere presence of abundant focal proteins, may be involved in altered regulation of focal adhesion in senescence.

Expression levels of β3-integrin and focal adhesion kinase (FAK), other key components in focal adhesion, were not significantly altered in senescent fibroblasts, but c-Src (oncogenic tyrosine kinase) expression was found to be lower [49]. Activated c-Src protein phosphorylates FAK and paxillin, and thereby transmits the adhesion-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling [58]. Therefore, reduced c-Src levels may contribute to the decreased proliferation and migration of senescent cells. However, there is a paper reporting increased phosphorylation of FAK as well as paxillin in senescent fibroblasts [59]. Certainly, molecular details on the alteration of focal adhesion formation and the signaling from and to the adhesion foci in senescent cells need to be further elucidated. Meanwhile, tendon fibroblasts from old mice adhere less efficiently [51]. This phenomenon may be due to poor formation of adhesion plaques, since most FAK, paxillin, and talin proteins are found in the cytoplasm rather than at the surface. It should be noted that these tendon fibroblasts did not show other phenotypic changes indicative of senescence.

Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) is a factor that links cell adhesion to the cytoskeleton and signaling proteins, and therefore plays an important role in the arrangement and expression of cytoskeletal proteins [60]. The level of ILK is substantially higher in cardiac fibroblasts and renal cells from old rats [53]. Importantly, ILK overexpression causes expression of a senescence-like phenotype (e.g., cytoplasmic enlargement, SA-β-Gal activity, lower cell proliferation, and increased levels of p53 and p21 proteins) in cardiac fibroblasts from 3-month-old rats, and its knockdown abolishes expression of these phenotypes in the cells from aged rats. Modulation of ILK levels also causes a change in the level of smooth muscle α-actin bundle and vimentin fibers that are abundantly present in the cardiac fibroblasts of old rats [53]. Therefore, the increase in ILK may contribute to fibrosis found in old hearts and kidneys. Meanwhile, total and phosphorylated levels of FAK and other focal adhesion-associated proteins, such as FAK-related non-kinase (FRNK), c-Src, Ras homolog gene family member A (RhoA), and paxillin increase in aged rat aortas, suggesting increased focal adhesion signaling in aortic tissue during aging [61]. Upregulation of some of these factors (c-Src, FAK, and paxillin) is infrequently observed in senescent fibroblasts, and the status of these factors therefore needs more careful examination, and their roles in aged aortic tissue should be addressed.

In senescent fibroblasts and certain organs of old rats, the level of caveolin-1 protein and the number of caveolae, the membrane domain where caveolin proteins abundantly localize, are substantially higher [77]. A possible role for increased caveolin-1 levels in the increased adhesion of senescent fibroblasts has been suggested [59]. Caveoloin-1 knockdown in senescent cells resulted in disrupted focal adhesion and actin stress fibers via the inactivation of FAK and caused a morphological change to the young cell-like spindle shape.

Fibronectin expression increases during serial passage of fetal lung and skin fibroblasts, and umbilical vein endothelial cells [62, 63]. Also, the expression of fibronectin substantially increases during aging in skin tissues and aortic endothelial cells in vivo [62]. Whether the increased presence of fibronectin in the extracellular matrix (ECM) contributes to increased adhesion of senescent cells was not determined experimentally. Meanwhile, fibronectin is degraded by members of the matrix metalloproteinase family, and the degradation products are detected in blood of old subjects with chronic pathology, but, interestingly, not in the blood from centenarians [64]. Some of these fragments are known to exert certain pro-aging effects such as collagenolytic activity.

Lysosomal content

Increased lysosomes and lipofuscin accumulation

The increase in lysosome number and size is one of the most characteristic changes observed with microscopic examination of late-passage fibroblasts ([65–67]; and Fig. 2a). A marked increase in the volume of lysosomes during aging is also consistently observed in postmitotic cells like cardiac myocytes and hepatocytes of rat and human subjects [68–70]. Therefore, the increase in lysosomal mass is a hallmark of both in vitro senescent somatic cells and in vivo aged postmitotic cells. In contrast, primary fibroblasts from aged subjects show an increase in lysosomal number only after a serial passage in vitro, but not during the initial passage, indicating that the fibroblasts in aged individuals have low lysosomal mass [71]. It is still possible, however, that the fibroblasts in old individuals may not be out of their replicative potential or have not accumulated enough oxidative damage.

Fig. 2.

Increase in lysosomal content and SA-β-Gal activity. a Early passage and senescent human fibroblasts (as in Fig. 1) cultured on chamber slides were incubated for 30 min in the presence of Lysotracker Red DND-99 (5 ng/ml) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), washed in PBS, and mounted. Imaging of cells was performed using the 100× oil objective (numerical aperture 1.4) of an LSM 510 confocal microscope equipped with a Zeiss axiovert 100 M base (Zeiss MicroImaging, Thornwood, USA). Sections with maximum nuclear contrast were selected and photographed. b Early passage and senescent human fibroblasts were stained in situ for SA-β-Gal activity. Pictures were taken under bright field illumination (Kindly provided by Drs. Kimberly Johung and Daniel DiMaio, Yale University)

The increase in lysosomal mass is so extensive that often a large part of cytoplasm is occupied by lysosomes [71]. This increase in both the senescent fibroblasts and the aged postmitotic cells is largely attributed to an increase in the number of lysosomes that contain indigestible autofluorescent materials like lipofuscin. These lysosomes are sometimes referred as residual bodies or dense bodies [72]. It is postulated that the shift of the population of lysosomes from functional primary ones to the non-functional lipofuscin-loaded ones in the aged cells causes a waste of newly produced lysosomal enzymes leading to reduced turnover of damaged organelles like mitochondria. This, in turn, leads to enhanced production of ROS, thereby forming a vicious pro-aging cycle [73]. However, this ‘mitochondria-lysosome axis theory of aging’ has recently been challenged by the finding of extended longevity of mice with reduced mCLK-1 activity of co-enzyme Q7, a mitochondrial enzyme necessary for ubiquinone synthesis, despite high level mitochondrial oxidative stress [74]. Regardless, lipofuscin accumulation is associated with a number of aging-associated degenerative disorders including Alzheimer’s disease, and it is therefore of great importance to better understand the cell biology of the formation and removal of these residual bodies.

The number of lipofuscin-loaded lysosomes has also been shown to increase in proliferating cells upon a temporal growth arrest by contact inhibition [75]. Therefore, lipofuscin accumulation is not an event occurring exclusively in senescent or aged cells. Still, a general consensus is that the accumulation of these autofluorescent materials represents a hallmark of cellular senescence and aging.

Lysosome biogenesis

Cytopathological examination revealed the presence of unaltered primary lysosomes in late-passaged cells, indicating the continuous generation of nascent lysosomes. Immunohistochemical and biochemical examinations clearly documented that levels of certain lysosomal enzymes increase in late-passage fibroblasts or certain types of cells from old organs [71, 76–78]. Whether there is an increase in lysosomogenesis during cellular aging in vivo and in vitro, however, has not been systematically explored. It was observed that mRNA levels of a large number of lysosomal enzymes increased to varying degrees in fibroblasts undergoing replicative senescence and senescence-induced fibroblasts and HeLa cells [67]. In addition, in a microarray analysis on the induced senescence of HeLa cells, the expression of 45 lysosomal enzyme genes increased significantly [79]. These results suggest that lysosomogenesis may also be increased during cellular senescence. Although different lysosomal genes were found to be induced to different levels [67, 79], a transcription factor common to a school of the lysosomal genes may exist and be activated for simultaneous induction of a majority of lysosomal genes.

Activities of some but not all the lysosomal enzymes has been detected in blood of aged animals and humans [78]. Cytosolic localization of certain lysosomal enzymes such as cathepsin D in tissues of aged rats was also noticed [80]. This observation, however, is probably not due to lysosomal rupture or leakage since the activities of other lysosomal enzymes do not increase in the cytosolic fraction. Intracellular sorting of certain lysosomal proteins or their post-translational modification could be altered during cellular senescence and aging.

Finally, lysosomes are thought to be vulnerable to oxidative stress and may undergo rupture as a result. High content of metal ions found in lysosomes could facilitate Fenton reaction to produce hydroxyl radicals, which, in turn, disrupt the integrity of the lysosomal membranes [81–83]. Although lysosomal rupture has been found to be associated with apoptosis and necrotic cell death [81], its occurrence during aging was not firmly established.

β-Galactosidase activity

β-Galactosidase activity can be detected at pH 6.0 in many cultured cells undergoing replicative and induced senescence (Fig. 2b), but is absent from actively proliferating cells, and was therefore named senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) activity [84]. By virtue of the simple assay method, SA-β-Gal activity has been the most extensively utilized biomarker of cells aged in vitro and in vivo without much understanding of its cellular or biochemical nature. SA-β-Gal-positive cells were detected in organs of old individuals and animals, and, thereby, inspired the belief that senescent cells accumulate with age in body and that cellular senescence is a feature of organismal aging (e.g., [84–87]). It also facilitated aging research at the organismal level in various model animals including C. elegans, Drosophila, and zebrafish [88], not to mention mammals. Although the use of SA-β-gal as a biomarker of senescence is popular, its suitability and dependability were often challenged [8, 89–95]. Several laboratories reported that β-galactosidase activity can be detected at pH 6.0 in cells under various non-senescent conditions. Examples include: (1) extended incubation of fibroblasts in low serum [94], (2) extended culture of certain cancer cell lines in normal medium [92], (3) culture of normal as well as immortal IMR90 fibroblasts at high density [8, 94], (4) culture of WI-38 fibroblasts treated with C6-deramide [90], and (5) in vitro-differentiated neuroendocrine cells from human prostate epithelium [93]. In the case of the fibroblasts cultured with low serum, SA-β-gal activity disappeared when the medium was replenished with 10% serum. There are also conflicting reports regarding the presence of SA-β-gal activity in aged tissues. For example, fibroblast cultures established from donors of different ages showed SA-β-gal positivity as a function of in vitro replicative age, but not the donor’s age. Furthermore, the activity was found only in the lumen of hair follicles and no age-associated increase was detected in skin sections of 53 individuals of various ages [8].

There are strong genetic evidences to indicate that SA-β-Gal activity originates from lysosomal β-galactosidase. Senescent human GM1-gangliosidosis fibroblasts lacking lysosomal β-galactosidase fail to express SA-β-gal activity, and the activity is greatly reduced in senescent cells when the concentration of GLB1 mRNA is reduced by RNA interference [77]. Together with some biochemical evidence showing a good correlation between the β-galactosidase activities at pH 4.0 and pH 6.0 [94, 96–98], this demonstrates that SA-β-Gal activity is lysosomal β-galactosidase activity that increases enough in senescent cells to be detected even at suboptimal pH (6.0). It further indicates that SA-β-gal activity is a surrogate marker for increased lysosomal number or activity, a change found in replicative senescence and organismal aging as mentioned previously. Therefore, it seems clear that SA-β-gal activity is not an exclusive marker of cellular senescence or a marker of organismal aging but an indicator of the presence of cells with high lysosomal activity. If this is the case, one can predict that the conditions characterized by increased lysosomal content will also display elevated β-galactosidase activity at pH 6.0, and, conversely, that other lysosomal proteins are likely to increase during senescence. It is also of interest to see whether the putative lysosomal transcription factor aforementioned responds to any kind of the stress that causes induction of SA-β-gal.

Granule content

Cellular granule is the general term for intracellular electron-dense particles detected by transmission electron microscopy. Their existence and components are different from cell to cell, such as alpha granules in platelets, secretary vesicles in granulocytes, and glycogen granules in muscle and liver. Levels of cellular granularity can be estimated by an increase of side scatter parameter, a measurement of the amount of laser beam (488 nm) that bounces off particulates inside cells, with FACS analysis. Interestingly, during replicative as well as induced senescence, side scattering (SSC) of light increases as does FSC (Fig. 3a). It is not clear why cell granularity increases or what is contained within the granules observed in senescent cells. The increased number of lysosome containing lipofuscins should largely be responsible for the increased granule content [99], but the levels of other granular matters, including subcellular organelles, storage granules, and large inclusion bodies may also increase.

The accumulation of glycogen aggregates is detected in senescent human fibroblasts and in senescence-induced Chang cells ([71, 100]; and Fig. 3b). Glycogen granules also accumulate in myelinated axons [101] and liver tissues of aged rats [100], and are found to form inclusion bodies in the cytoplasm of the cerebral cortex and the underlying white matter of a significant portion of people older than 60 years of age [102]. A direct involvement of glycogen synthesis or a metabolic pathway involving glycogenesis in senescence modulation was demonstrated. In cells undergoing either replicative or induced senescence, the inactivating phosphorylation on GSK3, a negative regulator of glycogen synthesis, increases, while that of glycogen synthase (GS) decreases [100]. Treatment with GSK3 inhibitors, siRNA, or a dominant-negative mutant induce a senescence phenotype, while GS knockdown attenuates the expression of the phenotype [100]. GSK3β is also a key negative regulator of Wnt signaling [103], in which β-catenin activates expression of genes responsible for cell proliferation that is important in stem cell maintenance, neurogenesis, and regeneration of hair and bone in adult mice [104]. Importantly, activation of Wnt signaling through expression of constitutively active β-catenin in MEF [105], or inhibition of GSK3β in bovine endothelial cells, accelerated expression of the senescence phenotype [106]. However, the increase in glycogenesis due to decreased activity of GSK3 and its direct relationship to senescence is still questionable since deletion of GSK3β in murine embryonic fibroblasts (which expresses activated Ras), induced transformation rather than senescence [107]. The in vivo significance of this finding is not conclusive. Activities of GS and glycogen phosphorylase were low in liver homogenates [108] and skeletal muscle [109] of aged rats compared to young or adult rats. Also, glycogen deposition in the livers of old rats after a complete depletion by starvation was significantly slower [110].

Meanwhile, a positive role of GSK3β in cellular senescence has also been quite well demonstrated. Contrary to the effect of GSK3β mentioned above, overexpression of GSK3β promotes replicative senescence in human fibroblasts [111]. During cellular senescence of human fibroblasts, Wnt signaling is downregulated due to decreased Wnt expression, and the addition of Wnt3a delays cellular senescence [112]. In addition, inactivation of Wnt signaling or activation of GSK3β has been shown to be essential in SAHF formation, a well-established marker of senescence [112] (see below). Wnt signaling may influence cellular senescence in two opposite directions, depending on the β-catenin interaction with its target transcription factor, either TCF/LEF or FOXO [113, 114]. TCF/LEF is typical downstream effector of Wnt signaling [115], while FOXO is an inducer of the genes responsible for cell cycle arrest in response to oxidative stress [116]. The activity and nuclear localization of FOXO is negatively controlled by phosphorylation and acetylation modifications [117, 118]. For these reasons, signaling that modulates nuclear abundance of the active form of FOXO may play a key role in determining the impact of Wnt signaling on senescence.

Mitochondria

Mammalian cells contain hundreds to thousands of mitochondria, and the mitochondrial mass is subject to change during cell growth and differentiation, and under certain physiological conditions such as endurance exercise. Mitochondria also undergo qualitative changes during replicative senescence and aging. Deterioration in mitochondrial respiratory chain function is found in most postmitotic cells during human aging [119, 120], and accelerated mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) were also shown to be associated with aging and certain age-related diseases in animals [121, 122]. The mitochondrial dysfunction in aging is attributed to its aberrant ROS generation [123]. In addition to activating several stress signaling pathways, overproduced mitochondrial ROS can also accelerate the rate of telomere shortening, thereby contributing to cellular senescence [124, 125]. Therefore, it is important for a cell to efficiently remove damaged mitochondria to retard the aging process. Increased mass and size of mitochondria are commonly observed in cells aged in vivo and in vitro, implying their causative role in aging.

Increased mitochondria mass in cellular senescence

Hayflick [30] and others [126] reported the increased appearance of long, thin, and irregularly shaped mitochondria in human fibroblasts approaching the end of their replicative life span. Recently, an increase in mitochondria mass was reported during replicative senescence of MRC-5 human lung fibroblasts [127, 128]. Increased mtDNA content was also observed in cells isolated from aged human subjects (see below for detail). The increase in mitochondrial mass and mtDNA was proposed to be a feedback response to compensate for the functional decline of mitochondria caused by ROS damage [129, 130]. Such a notion is supported by several similar observations on ROS-dependent increases in mRNA of mitochondrial proteins. For instance, treatment with antimycin A, an inhibitor of the cytochrome bc1 complex, caused an increase in cytochrome b and c1 mRNA in a manner sensitive to antioxidant N-acetylcysteine [131]. Also, a higher level of ROS produced in mtDNA-depleted (ρ0) HeLa cells seems to increase the levels of NRF-1 and TFAM, transcription factors responsible for mitochondrial protein expression in the nucleus and mitochondria, respectively [132]. Treatment with H2O2 or buthionine sulphoximine, which imposes oxidative stress by depleting cellular glutathione, causes an increase in mitochondrial mass as well as mtDNA in MRC-5 cells [133]. More recently, it was reported that DNA damage (including that caused by H2O2 treatment) induces mitochondrial biogenesis through activated ATM, a major signaling molecule in response to double-strand DNA breaks. ATM, in turn, activates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), resulting in the induction of the mitochondrial biogenesis factors PGC-1α, NRF-1, and TFAM [134]. Also, in human skeletal muscle tissues, the level of TFAM and NRF-1 mRNA as well as their proteins or DNA binding activity increased substantially in aged subjects [135]. Therefore, cells approaching senescence may produce more mitochondria to compensate for the increasing number of mitochondria damaged by the oxidative stress.

Mitochondrial mass may also increase as a consequence of changes in mitochondria turnover. Mitochondrial degradation is largely mediated by autophagy [136], and it seems that the level of mitochondrial autophagy in a cell is determined by two different factors: (1) the state of the substrate, and (2) the integrity of the autophagic pathway. Conceivably, smaller mitochondrion may be a better substrate of autophagy as suggested by one study [136]. The number of small mitochondria increased dramatically while that of large ones changed only slightly when autophagocytosis was inhibited by 3-methyladenine (3-MA). However, expression of Fis1, one of the mitochondrial fission modulators (see below), as well as the fission activity are downregulated during cellular senescence [137]. Decreased mitochondrial fission would lead to reduced autophagic turn-over resulting in an increase in mitochondrial mass. Importantly, it was recently demonstrated that autophagy accompanied by coordinated mitochondrial fission and fusion selectively removes damaged (depolarized) mitochondria that are abundantly present in senescent and aged cells [138]. It is also shown that Parkin, whose loss-of function mutation is linked to familial Parkinson’s disease [139], is recruited to depolarized mitochondria and promotes the selective elimination of depolarized mitochondria [140]. It is of importance to determine the correlation between the status of Parkin-mediated selective mitophagy and the altered level of dysfunctional mitochondria in senescent and aged cells.

Decreased macroautophagic activity was observed in cells from aged animals [141], and has also been considered as an important reason for the accumulation of altered (or damaged) mitochondria in aged cells [142, 143]. The decline of macroautophagy can be attributed to a decrease in autophagosome formation and a delay in autophagosome elimination (through fusion with lysosomes) [144]. The molecular mechanisms for the decreased activities have not been studied extensively, but, in certain models of cellular senescence, the latter problem was attributed to lysosomal permeabilization. In HUVEC cells, exposure to a high level of AGE promoted lysosomal permeabilization leading to inefficiency of autophagy. This inefficient autophagy could be due to reduced digestion as well as the inability of lysosomes to fuse with autophagosomes to form autophagolysosomes resulting in premature senescence and apoptosis [145].

The importance of autophagosomal elimination of the ROS-hypergenerating organelles was evidenced by anti-aging effects of pharmacological intensification of autophagy using an antilipolytic agent [146]. In addition, caloric restriction, the most potent anti-aging strategy, also activates autophagy as an essential part of the anti-aging mechanism [142]; however, a similar decrease in autophagic activity has not been demonstrated in cells undergoing replicative senescence.

In summary, there are multiple ways that could lead to the increased mitochondrial mass in senescent cells, including increased biogenesis, decreased fission, decreased autophagosome formation, and elimination. However, the increased biogenesis and the decreased removal of damaged mitochondria could certainly result in totally different levels of mitochondrial function. In senescent fibroblasts, ATP levels are quite low [147], and decreased turn-over rather than increased biogenesis is therefore more likely the reason for the increase in mitochondrial mass in senescent cells. Defective or poor control of mitochondrial quality could trigger and accelerate cellular senescence as well as certain age-associated disorders. Conversely, the better maintained mitochondrial quality would likely help cells manage a healthier cellular life and deter age-associated disorders.

Altered mitochondrial fission and fusion

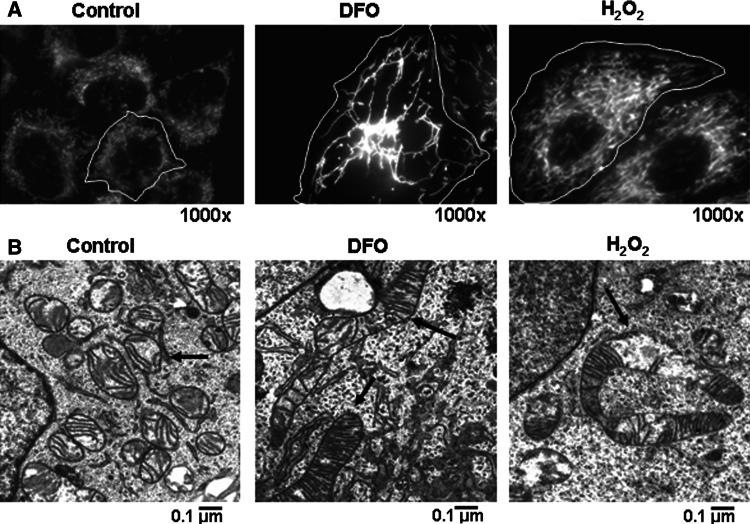

It appears that mitochondrial fission and fusion not only direct mitochondrial morphology and density but are also associated with the expression of senescence phenotype. Blocking fission activity leads to the formation of elongated mitochondria, a high level of ROS, and the appearance of a senescence-like state [77, 137]. Conversely, overexpression of Fis1 delays expression of the senescence phenotype [137]. Furthermore, exposure to subcytotoxic dose of H2O2 [137] induces a state of senescence while causing a reduction in mitochondrial fission and development of elongated giant mitochondria (Fig. 4). From these findings, an alteration in the balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion during cellular senescence and aging is expected. The work of Jendrach et al. [148] showed that, in senescent HUVEC cells, large aggregates of mitochondria with low membrane potential were frequently observed, and the fission and fusion activities as scored by number of filmed events were substantially lower in late-passage cells. Fibroblasts cultured at low oxygen (1–5% instead of 20% O2) proliferate with significantly extended population doubling capacity [149–151], and it would be interesting to determine the status of mitochondrial fusion and fission dynamics in these cells. Mitochondrial fission and fusion in mammals are mediated by a family of proteins, Drp1 and Fis1 for fission, Mfn1, Mfn2 and Opa1 for fusion [152], and it is of importance to determine whether the levels of these proteins and their activities are regulated during cellular senescence and in aged tissues. Drp1 activity is positively regulated by multiple factors through phosphorylation, and phosphorylation by cyclin B/Cdk1 has been proposed as a mechanism for mitochondrial fragmentation during mitosis [153]. It is of interest to know whether low cyclinB/Cdk1 activity is responsible for the formation of long filamentous or giant mitochondria in senescent cells and postmitotic cells in aged tissues.

Fig. 4.

Changes of mitochondrial morphology and mass in stress-induced cellular senescence. a Chang cells induced to senesce by treatment with DFO or H 2 O 2 as in Fig. 1 were stained with MitoTracker Red and visualized with an Apo Plan 100× oil-immersion objective (numerical aperture 1.4) on an Axiovert 200 M fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Gottingen, Germany). Highly interconnected mitochondria with increased mass are shown. b Elongated (in DFO) or elongated and defective (in H 2 O 2) mitochondrion is visualized in images obtained by electron microscopy (see arrows)

Decreased fission or increased fusion may have some beneficial effect for maintaining ATP production at a later stage of cell proliferation since complementation between damaged dysfunctional components in the electron transport chain complexes may be allowed. Evidence has been provided for such complementation between fused mitochondria, possibly providing a chance to dilute defects in the electron transport proteins as well as innermembrane and genetic components [148, 154–156]. For example, when two cells expressing differently labeled subunits of complex I were fused, colocalization of the different label was easily detected. Importantly, the mitochondrial dynamics is significantly altered in senescent HUVEC cells [148]. In order for cells to maintain efficient ATP generation, both the fission-mediated removal of defective mitochondrion and the fusion-mediated complementation are needed, but somehow the latter might prevail in senescent cells as mentioned above.

Enlarged mitochondria in cells of old animal

A decreased number but increased size of mitochondria is observed in fibroblasts from old individuals [157]. Mitochondria are in a similar state in postmitotic cells from old animals. In old mice livers, mitochondria show a 60% increase in mean size [158], and in hepatocytes from human subjects over 60 years of age, the number of mitochondria is decreased, but each mitochondrion has a higher level of cristae and is much larger in size [159]. In cardiac myocytes of aged rats, there is a dramatic increase in mitochondrial volume that is accompanied with degenerative morphology and function such as swelling, partial loss of cristae, accumulation of mtDNA mutation, low mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), and decreased ATP production [160–162].

Transcription of mitochondrial protein genes during aging is reduced [163, 164], although the copy number of mtDNA is found to be higher in lung, brain, and skeletal muscle of elderly subjects [163, 165, 166]. This indicates that biogenesis for intact mitochondria may be compromised in aged tissue, and that the accumulation of mitochondria in cells of old animals and humans may therefore be attributed to defective autophagic recycling [167, 168]. In addition, although the reason for mitochondrial enlargement is not yet well understood, oxidative stress is suggested to be involved. Myocytes from neonatal rats, during a 3-month-long in vitro culture at 20% oxygen condition, progressively accumulated lipofuscin-loaded secondary lysosomes. This change was blocked by treatment with 3-MA, indicating that the increased lysosomal mass in large part is possibly residual bodies derived from autophagolysosomes that were not removed by autophagolysis [72]. During this 3-month in vitro culture, enlarged mitochondria with low MMP also became abundant, possibly linking the emergence of the giant mitochondria causally to oxidative stress. This notion is supported by other findings in which a similar mitochondrial change (enlargement as well as structural abnormality and low MMP) developed much faster in cells cultured under hyperoxic conditions [72]. Therefore, it looks as though oxidative stress likely plays a key role in the increase of the mitochondrial size and mass in both mitotic as well as postmitotic cells.

Mitochondrial function actually declines during aging. When the skin fibroblasts from different age groups are compared, there is a dramatic decrease in ATP content in the cells from aged individuals, especially those above 40 years old. This may relate to the significantly decreased rate of mitochondrial biogenesis in combination with an accumulation of defective mtDNA [169]. Large-scale deletion of mtDNA is a well-characterized change occurring in cells from old animals [170]. These deletions frequently correlate with abnormal electron transport chain activity (hypoactivity of cytochrome c oxidase and hyperactivity of succinate dehydrogenase) and are blamed as a contributing factor for age-related sarcopenia [171].

Heterochromatin foci

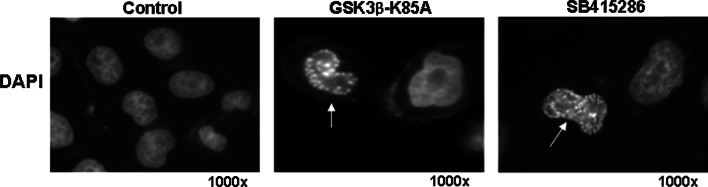

Severe chromatin condensation is one of the most conspicuous nuclear changes that occurs during cellular senescence. Upon staining with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), condensed chromatin in the senescent nuclei give rise to large fluorescent punctae which are called SAHF [172]. This phenomenon is in contrast to the uniform fluorescence distribution in nuclei of proliferating cells. SAHF appears in fibroblasts undergoing replicative senescence or senescence induced by expression of oncogenic Ras or chemotherapeutic drugs ([172]; and Fig. 5), and also in senescent cells in the tumor mass in an animal model [173]. In heterochromatin foci, DNA is associated with numerous proteins found in heterochromatin, such as HP1 (heterochromatin protein 1) and histone H3 methylated on Lys 9 (H3K9m), and seems transcriptionally incompetent [172, 174]. Genes that appear to be embedded in the SAHF, and are thereby transcriptionally suppressed, include E2F-responsive genes, most of which are required for cell cycle progression such as Cyclin A and E [172]. Ectopic overexpression of E2F1 in senescent cells cannot activate the expression of its target genes [172]. The SAHF’s role in this irreversible suppression of proliferation-promoting genes supports the postulation that SAHF is a mechanism responsible for the irreversible exit from cell cycle in senescence. Each senescence-associated heterochromatin focus is quite large and probably contains an entire single chromosome, but there is still a possibility for redistribution of euchromatin and heterochromatin regions. The DNA regions such as pericentromeres and telomeres are typically in heterochromatin in proliferating cells, but appear to be excluded from the SAHF [175–177]. In addition, apparently, many other promoters are not affected or even activated in senescence.

Fig. 5.

SAHF. Chang cells were induced to senesce by forced overexpression of a GSK3β-K85A inactive mutant or exposure to 12.5 μg/ml SB415286 (GSK3 specific inhibitor) for 3 days [100]. Images were taken by fluorescence microscopy after staining cells with DAPI. A nucleus with SAHF is indicated by an arrow

Certain DNA binding proteins play a direct role in SAHF formation. Overexpression of high-mobility group A (HMGA), non-histone proteins that bind to the AT-rich minor groove of DNA, and Asf1a and HIRA, the chaperone proteins that deposit histone H3.3 into nucleosomes, induce SAHF and a senescence-like phenotype in human fibroblasts, while their knockdown prevents SAHF induction by oncogenic Ras expression [174, 178]. It was also shown that both the transit of HIRA at PML bodies, and the formation of a trimeric complex between the modified HIRA, Asf1a, and histone H3, are required for chromosome condensation [177].

An upstream event that triggers SAHF formation has been proposed. As mentioned earlier, in replicative or the Ras-induced senescence of certain cell types, canonical Wnt signaling is repressed and the activity of the downstream negative regulator, GSK3β, is higher [112]. Active GSK3β phosphorylates HIRA and thereby induces its localization in PML bodies, a prerequisite event for SAHF formation, indicating that inactivation of Wnt signaling or activation of GSK3β is an event that triggers SAHF formation [112]. However, downregulation of Wnt signaling does not always lead to irreversible growth arrest or senescence in all cell types (E.H. Jho, personal communication). Therefore, it is of interest to determine if SAHF formation occurs in all cells where Wnt signaling is blocked. SAHF formation in WI38 and IMR90 human fibroblasts is pronounced, but not in BJ human fibroblasts [172, 179]. Whether this difference originates from different status of Wnt signaling is worth investigating.

Interestingly, SAHF is formed during an early stage of tumor development in vivo. Using K-Ras-induced tumor models in transgenic mice, Collado et al. [180] showed that cells of premalignant adenomas give rise to high level SAHFs along with other senescence markers, whereas cells of malignant adenocarcinoma do not. Similar observations were made in other mouse models [173, 181] and in humans as well [182]. These results, along with the finding that HMGA knockdown blocks SAHF formation and senescence but stimulates cell transformation by oncogenic Ras [178], provide strong evidence that cellular senescence is a cellular program that restricts cancer progression.

Meanwhile, the occurrence of SAHF-positive cells in tissues of aged animals has not yet been shown. Nevertheless, it was suggested that similar events occur in aging baboons. The number of nuclei containing increased levels of HIRA protein, an event found before the onset of other senescence phenotypes [174], is high in aged baboons. Furthermore, the number of such nuclei shows a striking correlation with the age of the donor baboons [16, 183].

Telomere dysfunction-induced focus

Telomere dysfunction-induced focus has emerged as a marker for senescence triggered by telomere shortening. As they proliferate, telomeres in cells with low telomerase activity get shortened. Short telomeres lose a protective structure composed of a variety of proteins including double- and single-strand binding proteins as well as certain repair proteins. Unprotected telomeres trigger a DNA damage response which eventually activates a DNA damage checkpoint enforced by p53 and Rb. A DNA damage response ongoing at short telomeres is demonstrated by the presence of DNA damage response factors such as 53BP1, γ-H2AX (phosphorylated histone H2AX), Rad17, ATM, and Mre11 at chromosome ends; this response occurs in an ATM-dependent manner [184]. The structure of a telomere end associated with these DNA damage response factors was termed TIF, and TIF is considered a genuine marker for telomere dysfunction. Importantly, γ-H2AX, which forms en masse at the sites of DNA double-strand breaks [185], was shown to associate with telomeres in senescent human fibroblasts [186]. Recently, an immuno-FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization) technique combining immunofluorescence for either 53BP1 or γ-H2AX and in situ hybridization for telomere sequence was developed [187, 188], and successfully documented the relationship between TIF and cellular senescence. Very few γ-H2AX foci localize to telomeres in early passage cells, but the number of γ-H2AX foci and its colocalization with telomeres increases dramatically in late-passage cells. Furthermore, the technique demonstrated a higher incidence of TIF-posititivity (as determined when 50% or more of DNA damage foci colocalized with telomere) in skin biopsies of an old baboon [16]. TIFs are also found in mouse tissues with slow but steady turnover such as skin, liver, lung, and kidney, and their frequency increases with animal aging (J. Sedivy, personal communication). Therefore, TIF may potentially be used as a reliable marker for telomere shortening-induced senescence in vitro as well as in tissue, although it remains to be determined what type of cells are TIF-positive in mouse and baboon tissues. It was shown that postmitotic cells, such as skeletal muscle cells, have a very low frequency of DNA damage foci and TIF positivity in a very old baboon [16]. This indicates that postmitotic cells rarely suffer from the double-strand DNA break and telomere dysfunction or that they do not utilize the DNA damage signaling that functions in mitotic cells. Interestingly, treatments such as exposure to high fat diets, oxidative stress, or resveratrol were found to alter the TIF frequency in mouse tissues (J. Sedivy, personal communication). Once a higher frequency of TIF is found in tissues from aged human subjects, this marker can be applied to help study the effect of various physiological conditions on senescence in different organs.

Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome-like nuclear defects

Individuals with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria, a severe premature aging syndrome, have mutations in lamin A (LMNA), a nuclear lamina protein, which typically leads to aberrant nuclear localization of the protein (the mutants commonly contain a 50-amino acid internal deletion, and are collectively called progerin or prelamin A) [189]. Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) cells have various defects in nuclear structure and function [190, 191] including dysmorphic nuclear structure, increased DNA damage, and decreased levels of nuclear proteins such as HP1, LAP2 (lamin A-associated protein 2), and H3 lysine-9 tri-methylation (H3K9me3). Importantly, in HGPS fibroblasts, the DNA damage checkpoint is persistently activated as evidenced by the increase in H2AX foci [191]. This suggests that, in HGPS nucleus, DNA damage may be augmented; however, a reason for this has not yet been suggested. Lamin A is a farnesylated protein, and inhibition of prelamin farnesylation reverses the aberrant nuclear shape but does not suppress the DNA damage response in HGPS cells [192].

Importantly, a large fraction of the skin fibroblast population from old individuals was shown to have HGPS-like nuclear phenotype [193], and the number of such cells increases with passaging. Furthermore, the slope is much steeper during the passage of cells from old individuals. Cells from old individuals and HGPS patients commonly suffer from increased levels of unrepaired DNA damage, as indicated by the elevated level of γ-H2AX foci. As mentioned, this increase in H2AX foci has also been observed in aged mice and baboons [183, 188]. These findings, therefore, suggest that HGPS-like nuclear alterations can be considered a possible nuclear marker for aged cells in vitro and in vivo; however, the association of this phenotype with aging should be verified in other cell types and organisms.

Significance of the traits of cellular senescence

In Table 1, the status of cellular changes observed in cells undergoing cellular senescence, and in fibroblasts and postmitotic cells from aged organisms, is summarized. Several points need to be addressed for the significance of these traits. First, many cellular constituents undergo changes in replicative or induced senescence, but not in the primary fibroblasts isolated from aged individuals. It is possible that, in aged bodies, somatic cells never, or rarely, proliferate long enough to reach the state of senescence. Alternatively, since cells in vivo reside in an environment with lower oxygen, they may not accumulate as significant an amount of damaged materials (lower level passive traits), and do not therefore exhibit active traits which may be induced in response to the accumulation of passive traits. Although other possibilities still exist, each of these are sufficient to explain why certain changes, like SA-β-gal activity, are not being reproducibly detected in fibroblasts (or tissues) from aged subjects.

Table 1.

Summary of senescence-associated changes in cells isolated from aged subjects

| Cell factor | Changes |

|---|---|

| Cell volume | Increased cell volume and surface area in senescence |

| For postmitotic cells, an increase in hepatocytes from aging rats has been reported [34] | |

| Decreased protein degradation may be a major cause [199] | |

| Cytoskeleton | Increase in vimentin protein and vimentin filaments in senescence |

| In postmitotic cells, vimentin status not known | |

| Increased level in certain tissues of old subjects [44–46] and in age-associated diseases [200] has been reported. It may be related with its susceptibility to AGE modification [47] | |

| Lower actin protein level and fewer and thinner actin fibers in senescence (but, a report on the presence of thicker and longer fibers in senescent cells also exists [21]) | |

| In postmitotic cells, status not known | |

| Lower protein level in the foreskin of an aged individual [50] and fibroblasts from the Achilles tendon of aged mice [51] | |

| Cell adhesion | More focal adhesions present in senescence (ILK activity is associated with the expression of senescence phenotype [53]. And, increased fibronectin expression may also be a contributing factor [62, 63]) |

| In postmitotic cells, status not known | |

| Tendon fibroblasts from old mice form poor focal adhesions [51] | |

| Lysosome content | Dramatic increase in number in senescence (mostly due to the increase in lipofuscin-loaded residual bodies) |

| In postmitotic cells, a marked increase in lysosome volume is well documented [68–70] | |

| Lysosomes (the lipofuscin-loaded bodies) also accumulate in temporally growth-arrested early passage fibroblasts [75] and long-term incubated postmitotic cells [201] | |

| Lysosome biogenesis also occurs during senescence [67], but it is not known to occur in aging postmitotic cells | |

| SA-β-Gal activity | The most widely cited marker of senescence (but, also expressed under other conditions. Likely a surrogate marker of the increase in lysosome content) |

| In postmitotic cells, status not known | |

| Glycogen granule content | High in cells undergoing replicative or induced senescence (a decrease in GSK3 activity may be involved [100]) |

| In postmitotic cells, status not known | |

| High in certain tissues of aged rats and an old individual [100–102] | |

| Mitochondria morphology and function | Increased mitochondria mass in senescence (likely due to increased biogenesis and reduced turn-over) |

| In postmitotic cells, mitochondrial enlargement is well documented (also likely due to defective autophagic turn-over, but possibility for biogenesis is low [72]) | |

| Mitochondrial enlargement and MMP loss also occur during in vitro long-term culture of young rat myocytes reflecting an induction by oxidative stress [72] | |

| Mitochondrial elongation and network formation and low MMP in senescence | |

| In postmitotic cells, both elongation and low MMP are apparent [160–162, 202] | |

| Similar observation reported in fibroblasts from old subjects [157] | |

| SAHF | One of the most prominent cellular traits of senescence |

| In postmitotic cells, status not known | |

| Found in senescent cells from a tumor mass [173] | |

| Higher levels of HIRA, a component of SAHF, is detected in aging baboons [16] | |

| TIF | A key factor responsible for irreversible growth arrest in senescence |

| Status not known, but not expected to be detected in postmitotic cells | |

| Higher number of TIF-positive cells detected in aged baboons [16] | |

| HGPS-like nucleus | Fraction of cells with the HGPS-like nucleus increases with passage in vitro and the slope is steeper during the passage of fibroblasts from an old individual [193] (does not appear to be directly caused by oxidative damage) |

| In postmitotic cells, status not known | |

| Higher percentage of dermal fibroblasts from an aged individual is positive for the HGPS-like phenotype [193] |

There are traits of cellular senescence also displayed in postmitotic cells from aged individuals (Table 1). Lipofuscin accumulation is the best known example of these traits, but others, such as increased lysosomal content, changes in mitochondrial mass, and morphological and functional change of mitochondria, are also quite dramatic in postmitotic cells. It appears as though the observed lysosomal and mitochondrial changes occur in similar manners in senescent cells or in aged postmitotic cells, e.g., increased biogenesis and decreased removal of the organelles. The changes in senescent cells may be both passive (e.g., accumulation of lipofuscin-loaded residual bodies and a decrease in mitochondrial turn-over) and active (biogenesis of lysosomes and mitochondria), but so far those in the postmitotic cells appear to be primarily passive. In senescent and postmitotic cells, putative stress-inducing materials or damage products are neither lost nor diluted out through cycles of cell division, thereby explaining why passive traits are commonly expressed in both cell types. Therefore, understanding the underlying mechanisms of these observations in postmitotic cells may be facilitated by studying cells at replicative senescence.

Finally, most traits of senescence need further investigation to be properly evaluated for their significance in vitro and in vivo. It seems clear from this review that current knowledge on changes in cellular constituents during senescence and aging is limited and that consensus has not been reached in many cases. This is well exemplified by the fact that many conclusions have been made on the status of cytoskeletons with limited data. Furthermore, many studies have been performed with limited numbers of cell lines and in some cases without the proper controls. For factors like vimentin and ILK, which apparently play important roles in expression of a senescent cell morphology, their significance should be determined by using a large number of senescent cells in better-controlled settings. Meanwhile, further studies detailing these and their underlying mechanisms would broaden our understanding of not only their relevance to aging, but also the cell biology of related phenomenon. Studies on the increase in lysosome content in senescence would provide information on lysosome biogenesis and residual body trafficking, topics about which our understanding is quite limited. In addition, the importance of the dynamics of mitochondria morphology in senescence and aging has only recently been recognized. The possible involvement of mitochondrial sirtuin proteins, such as SIRT3, 4, and 5 [194–198], and the regulation of mitochondrial fusion and fission in coordination with cell division, damage response, and cellular metabolic homeostasis, await further investigation. The SAHF and HGPS-like nuclei are potentially important in many aspects of cell biology and medicine, and, for this reason, their molecular details warrant further thorough investigation. It may be possible to intervene in aging or age-associated functional decline and diseases by modulating some of these cellular changes. Maintenance of high quality mitochondria through the activation of mitochondria turn-over and suppression of HGPS-like phenotype through modulation of progerin localization may be good candidates for such approaches.

Concluding remarks

Although studying senescent cells in a culture dish may provide valuable information about aging eventually, more work using this model needs to be done. In aging human tissues, the presence of somatic cells with traits of senescence have only rarely been reported; however, there are studies which suggest the presence of cells with senescent nuclear phenotypes such as SAHF [16, 183], TIF [20], and HGPS-like nucleus [172] in aged animals and human subjects. These observations encourage us to look for additional cellular changes related to senescence and use them to detect cells showing senescence traits in aged subjects. The in vivo relevance of certain senescence traits can be critically evaluated if more sensitive assay methods are developed and a generalization of the traits is established. For instance, the HGPS-like phenotype appears at a readily detectable level in fibroblasts isolated from aged individuals. If other senescence traits also appear in cells displaying this phenotype, and if the phenotype appears in a diversity of cell types undergoing senescence, it can be accepted as a genuine marker for aging somatic cells in the body.

For postmitotic cells, there is a significant sparseness of data concerning the phenomena of senescence and the phenotypes displayed. Although certain prominent cellular changes have been documented in postmitotic cells from aged subjects, the terminal arrest state of these cells has limited the characterization of putative changes in various cellular constituents, and reduced our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of these changes. A better understanding of the cellular traits associated with cellular senescence can potentially help overcome this limitation in certain cases. Observations made crudely in postmitotic cell cultures can be assured by analogy to the results obtained from the study of senescent cells. In particular, traits associated with changes in mitochondrial status would be good candidates. Finally, it is noteworthy that senescence induced by oncogenic Ras or DNA damage would serve the purpose quite well, since: (1) the growth-arrest state is easily and homogenously induced, and (2) cells can be cultured for long periods of time in the postmitotic state (irreversibly arrest state) allowing for time course studies of the phenotype.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Byung Pal Yu at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio for the time and effort he generously devoted to improve the quality of the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Daniel DiMaio at Yale University for helpful discussion and correction of English. This work was supported by a grant from the Research Program of Dual Regulation Mechanisms of Aging and Cancer from the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation) (M10756040001-08N5604-00110) and by the Korea Research Foundation Grant (MOEHRD, Basic Research Promotion Fund) (KRF-2007-314-C00229).

References

- 1.Campisi J, Kim SH, Lim CS, Rubio M. Cellular senescence, cancer and aging: the telomere connection. Exp Gerontol. 2001;36:1619–1637. doi: 10.1016/S0531-5565(01)00160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muller M. Cellular senescence: molecular mechanisms, in vivo significance, and redox considerations. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:59–98. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D, Lowe SW. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell. 1997;88:593–602. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu J, Woods D, McMahon M, Bishop JM. Senescence of human fibroblasts induced by oncogenic Raf. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2997–3007. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]