Abstract

During gene expression, multiple regulatory steps make sure that alterations of chromatin structure are synchronized with RNA synthesis, co-transcriptional assembly of ribonucleoprotein complexes, transport to the cytoplasm and localized translation. These events are controlled by large multiprotein complexes commonly referred to as molecular machines, which are specialized and at the same time display a highly dynamic protein composition. The crosstalk between these molecular machines is essential for efficient RNA biogenesis. Actin has been recently proposed to be an important factor throughout the entire RNA biogenesis pathway as a component of chromatin remodeling complexes, associated with all eukaryotic RNA polymerases as well as precursor and mature ribonucleoprotein complexes. The aim of this review is to present evidence on the involvement of actin and actin-associated proteins in RNA biogenesis and propose integrative models supporting the view that actin facilitates coordination of the different steps in gene expression.

Keywords: Actin, Myosin, Motors, Transcription, RNP, RNA transport, RNA localization

Introduction

In eukaryotic cells, RNA biogenesis is regulated at multiple levels from the gene to polysomes. The mechanisms that govern transcriptional control, RNA processing and nuclear export are integrated and influenced by the interplay between nuclear architecture, genome organization and gene expression, whereas in the cytoplasm mRNA transport and localization are important pre-requisites for efficient mRNA translation. In either case, a continuous RNA flow is maintained by multiprotein complexes that are often defined as molecular machines that undergo modifications and systematically exchange protein subunits through regulated protein–protein interactions [1].

Alterations of chromatin structure and dynamics affect gene expression in several ways. For instance transcription factories, distinct sub-nuclear foci where nascent transcription is likely to occur, depend on the establishment of intra- and inter-chromosomal connections between genomic regions with important roles in genome function [2, 3]. At the gene level, DNA accessibility for efficient replication, repair and gene transcription requires alterations of chromatin structure [4], which otherwise represents considerable hindrance for all of the above processes. For instance, in gene transcription chromatin structure alterations must be coordinated and synchronized with the transcription apparatus. Therefore, the dynamics of chromatin structure are tightly regulated through numerous mechanisms that include histone modification, chromatin remodeling, histone variant incorporation and histone eviction [5]. These mechanisms are modulated by co-transcriptional recruitment of co-activators and repressors necessary for all eukaryotic RNA polymerases in order to initiate, maintain and terminate RNA synthesis.

There is also a requirement for chromatin modification during co-transcriptional processing of nascent mRNA, and remodeling events occur to enhance the interplay between the polymerase machinery and the spliceosome [6, 7]. There is evidence that the human SWI/SNF subunit Brm is a splicing regulator [8], whereas in situ evidence for the interplay between the transcription apparatus and splicesome comes from an early study performed in the Balbiani ring (BR) genes from the dipteran Chironomus tentans [9]. Even though the spliceosome was not revealed to be a structurally well-defined unit, it could be localized in close proximity of the C-terminal domain (CTD) of the elongating RNA polymerase II [9]. Consistent with the dynamic nature of these co-transcriptional events, spliceosomal factors continuously associate and disassociate from nascent transcripts and splicing complexes during transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II, a dynamic coupling that is also important for regulation of alternative splicing [10].

During mRNA biogenesis, transcription is intimately coupled to co-transcriptional formation of messenger ribonucleoprotein particles (mRNP) and their preparation for nuclear export [11–13]. The steps leading to RNP assembly require molecular machines that display different degrees of complexity and dimensions. Capping in the 5′ end of nascent precursor (pre)-mRNA requires three enzymes; splicing requires the spliceosome comprising more than 100 proteins, whereas cleavage and polyadenylation involve between five and ten proteins. All these molecular machines interact closely with the transcription apparatus and also, to some extent, with each other [14–17]. This interplay allows a sophisticated control of the formation of mature mRNP complexes at the chromosomal level and also after release in the nucleoplasm. Emerging evidence suggests that this complex co-transcriptional regulation occurs also in rRNA biogenesis where a large set of non-ribosomal proteins is known to be required (see [18] and references therein). In either case, once the RNA transcripts are exported to the cytoplasm, they are left with the option of undergoing translation or being assembled into larger granules, which are subsequently transported to the cell periphery for translation [19]. The myelin basic protein (MBP) mRNA is probably one of the best characterized examples of transported RNPs. In oligodendrocytes, at the exit of the nuclear pore complex, the MBP mRNP is assembled into larger granules with a calculated diameter of about 400 nm. MBP mRNA granules are actively transported through oligodendrocyte processes towards the peripheral myelin compartment where the MBP mRNA is translated. Cytoplasmic RNA trafficking is, however, a general mechanism. It occurs in highly differentiated as well as cultured cells; it is important during the different steps of embryogenesis and controls gene expression and cellular function by providing asymmetric mRNA and protein distribution [19].

Multiple roles for actin in RNA biogenesis

Based on the above scenario, mRNA biogenesis requires a large set of cellular transacting factors that dynamically assemble and disassemble, making sure that during gene expression RNA synthesis and processing, nuclear export, cytoplasmic localization and translation are all synchronized and occur flawlessly. However, while many of the core components of the molecular machines implicated in transcriptional and post-transcriptional control of RNA biogenesis have been identified, the mechanisms coordinating chromatin structure modifications, transcription, RNP assembly and maturation with transport remain unclear.

Recent evidence has helped identify an important niche for actin and actin-associated proteins in modulating the crosstalk between individual phases throughout the entire RNA biogenesis pathway. In addition the extensive catalogue of nuclear actin-associated proteins involved at different levels during gene expression has contributed to placing actin under the spotlight in the biology of the cell nucleus (see Table 1). Actin has been localized to specialized subnuclear compartments, such as nucleoli and splicing speckles [20, 21]. Actin has also been implicated in chromosome movement [22, 23], in chromatin structure regulation [24], transcription [20, 25–29], RNP assembly and maturation [30, 31] as well as in the control of macromolecular transport [33, reviewed in 33, 34] (see Fig. 1). Moreover, the presence of many actin-associated proteins that are known to control actin polymerization and their involvement in nuclear function also suggest that the multiple roles of actin in gene expression may be modulated by changes in its polymerization state (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Nuclear actin-binding proteins

| Actin-associated proteins | Organism | References |

|---|---|---|

| Direct actin-binding in chromatin-modifying complexes | ||

| Helicase-SANT-associated (HSA) domain | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Szerlong et al. [124] |

| Transcription | ||

| RNA polymerase I | Mammals | Fomproix and Percipalle [20] |

| Largest subunit RPA194 | Philimonenko et al. [28] | |

| RNA polymerase II | Mammals | Hofmann et al. [26] |

| Pre-initiation complex | Kukalev et al. [29] | |

| Phosphorylated RNA polymerase II | ||

| RNA polymerase III | Mammals | Hu et al. [27] |

| RPC3 | ||

| RPABC2 | ||

| RPABC3 | ||

| MAL | Mammals | Vartiainen et al. [118] |

| RNA biogenesis | ||

| hrp36 | Chironomus tentans | Percipalle et al. [30] |

| hrp65-2 | Chironomus tentans | Percipalle et al. [25] |

| hnRNP A/B CBF-A | Mammals | Percipalle et al. [31] |

| hnRNP U | Mammals | Kukalev et al. [29] |

| p50 | Mammals | Ruzanov et al. [80] |

| RNA processing | ||

| RNA helicase II | Mammals | Zhang et al. [93] |

| Zhang et al. [94] | ||

| Export factors | ||

| Exportin 6 | Mammals | Stüven et al. [127] |

| F-actin biding proteins | ||

| Supervillin | Mammals | Pestonjamasp et al. [113] |

| Wulfkuhle et al. [114] | ||

| N-WASP | Mammals | Wu et al. [115] |

| ARP2/3 | Mammals | Yoo et al. [116] |

| Formin | Mammals | Chan and Leder [117] |

| G-actin-binding proteins | ||

| Profilin | Mammals | Skare et al. [102] |

| Cofilin | Mammals | Pendleton et al. [103] |

| β-thymosin | Mammals | Huff et al. [104] |

| Gelsolin | Xenopus laevis | Ankenbauer et al. [105] |

| Flightless | Drosophila | Davy et al. [106] |

| Seward et al. [107] | ||

| Mbh1 (severin-like and gelsolin-like) | Mammals | Prendergast and Ziff [108] |

| DNase I | Mammals | Peitsch et al. [109] |

| gCap39 | Mammals | Onoda et al. [110] |

| CapG | Mammals | De Corte et al., [111] |

| Renz and Langowski [112] | ||

| Myosin species | ||

| Nuclear myosin 1 (NM1) | Mammals | Pestic-Dragovich et al. [45] |

| Myosin VI | Mammals | Vreugde et al. [47] |

| Myosin 16b | Mammals | Cameron et al. [48] |

| Myosin Va | Mammals | Pranchevicius et al. [49] |

| Nuclear envelope proteins | ||

| Emerin | Mammals | Holaska et al. [87] |

| Spectrin repeat proteins | ||

| α-Spectrin II | Mammals | McMahon et al. [126] |

| McMahon et al. [127] | ||

| Sridharan et al. [128] | ||

| β-Spectrin II | Mammals | Tang et al. [129] |

| β-Spectrin IVΣ | Mammals | Tse et al. [130] |

| Syne/nesprin | Mammals | Mislow et al. [131] |

| Apel et al. [132] | ||

| Zhen et al. [133] | ||

| Padmakumar et al. [134] | ||

| Bpag | Mammals | Young et al. [135] |

| MAKAP | Mammals | Kapiloff et al. [136] |

| Kapiloff et al. [137] | ||

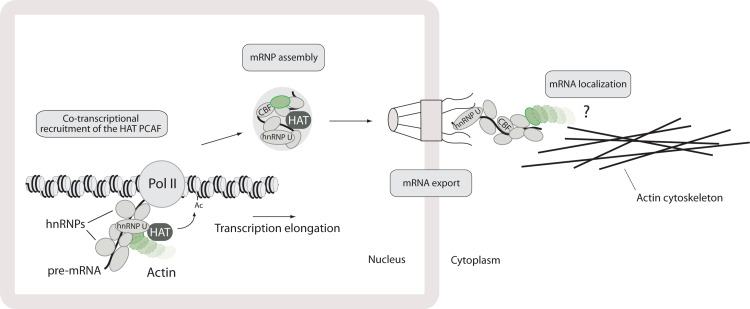

Fig. 1.

The above diagram summarizes the involvement of actin in nuclear function. Actin has been shown to be a component of chromatin remodeling complexes, to be associated with eukaryotic RNA polymerases and to be incorporated in RNP complexes. Evidence of active nucleocytoplasmic transport also suggests a functional crosstalk between nuclear and cytoplasmic actin

Here, evidence from this rapidly growing area of research is reviewed. These discoveries emphasize the key involvement of actin and actin-associated proteins in RNA biogenesis at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels and suggest new mechanistic models to integrate the different phases of gene expression.

Actin on the gene for transcription control

Early reports provided circumstantial evidence suggesting the involvement of actin in gene transcription [35, 36]. Later on, the interest in this field was considerably stimulated by the discovery that actin is also present in certain ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes [24]. However, direct evidence for a role in RNA biogenesis and, more specifically, in gene transcription came from experiments demonstrating that actin is a genuine component of pre-mRNP/mRNP particles and it is physically associated with all three eukaryotic RNA polymerases [20, 25–31, 37, 38].

In the case of RNA polymerase I, actin was found associated with both inactive and active enzyme, suggesting a dual function for actin in polymerase assembly at promoter and also during transcription activation [20, 28]. A similar scenario was depicted for RNA polymerase II where actin was found as component of the pre-initiation complex and associated with the hyperphosphorylated CTD of the elongating polymerase [26, 29, 39]. Again, these observations pointed towards multiple roles for actin in RNA polymerase II transcription, in transcription initiation as well as elongation of pre-mRNA molecules [26, 29, 39]. In the case of RNA polymerase III, the molecular interactions between actin and several of the polymerase subunits were also dissected [27]. β-actin was found to associate directly with RPC3 (RPC62), RPABC2 (RPB6) and RPABC3 (RPB8), suggesting that β-actin interacts very tightly with the RNA polymerase III complex, probably through direct protein–protein interactions with one or more subunits at the same time. Remarkably, both subunits RPABC2 and RPABC3 are common to all three RNA polymerases (for a review see [40]). Further biochemical and structural information is still required; however, these findings suggested that actin has a conserved and general mode of binding to all eukaryotic RNA polymerases, even though specific differences must be taken into consideration. For instance, one of the striking differences is that binding to the elongating RNA polymerase II occurs via its characteristic hyperphosphorylated CTD [39], whereas it is not yet known how actin interacts with elongating RNA polymerases I and III.

If actin is associated with all eukaryotic RNA polymerases, actin is also likely to be located at gene promoter. Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments indeed confirmed the presence of actin at rDNA promoter, promoters of inducible and constitutively expressed RNA polymerase II genes, as well as its association with the promoter of the RNA polymerase III U6 snRNA gene [26, 27, 39]. What is then the role of actin at the gene promoter? The present data suggest that actin could well modulate assembly of transcription competent RNA polymerases. This view is consistent with the presence of actin in the pre-initiation complex, with its association with inactive as well as active RNA polymerase I and, finally, with the observation that actin is necessary to start transcription of the U6 snRNA gene in reconstitution experiments [26–28]. The follow-up question is how does actin mediate polymerase assembly at the promoter? Is this function independent from the observation that actin is also in chromatin remodeling complexes? At the moment these questions remain formally unanswered. For instance, we do not know whether or not actin interacts with general transcription factors. However, chromatin structure modifications are required for transcription initiation, and they must synergize with the transcription apparatus (reviewed in [34]). Therefore, one interesting possibility is that actin performs a chaperone function in the molecular interplay between RNA polymerase and the machines involved in chromatin reorganization at the gene promoter to facilitate the establishment of transcription-competent RNA polymerases [34].

Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments uncovered evidence that actin is also present at the coding region of constitutively active genes, coupled to elongating RNA polymerases I and II [28, 39]. The general requirement for actin in elongation of pre-mRNA transcripts was proven in insects and mammals [25, 29, 39, 41]. In human cells, the interaction between actin and the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) hnRNP U proved to be essential for RNA polymerase II-mediated transcription elongation [29]. In a recent mechanistic study, the actin–hnRNP U complex was further shown to be necessary for recruitment to active genes of transcription co-activators, such as the histone acetyl transferase (HAT) PCAF [39], an important requirement to lower the nucleosome barrier imposed by densely packed chromatin and efficiently elongate pre-mRNA molecules. In fact, the actin–hnRNP U interaction is strictly required during the transcription elongation phase when actin, hnRNP U and PCAF are closely associated with the hyperphosphorylated CTD of the RNA polymerase II. Furthermore, even though actin and hnRNP U are present at gene promoter associated with the RNA polymerase II machinery, they interact only along the gene coding region [39]. This may be a direct consequence of CTD phosphorylation and partly driven by nascent pre-mRNA. However, post-translational modifications on either actin or hnRNP U (or both) may also be required to stabilize a functional actin–hnRNP U complex (see Fig. 2). These findings also came in support of a general model that was proposed earlier on in which actin in complex with certain hnRNPs functions as a molecular platform to facilitate recruitment of transcriptional co-activators (and perhaps repressors), enhancing the processivity of the RNA polymerase II enzyme [37]. Since similar results were obtained in mammals as well as insects, the actin–hnRNP-mediated regulation of transcription elongation is likely to be a rather conserved and general mechanism [34, 41]. The specific phosphorylation of Ser2 within the RNA polymerase II CTD heptapeptide repeats is a hallmark for transcription termination. Given that CTD binding by actin, hnRNP U and PCAF is dependent on Ser2 phosphorylation [38], the actin–hnRNP U complex may be implicated not only in the elongation of nascent pre-mRNA, but also in controlling transcription termination.

Fig. 2.

Actin accompanies mRNA transcripts from gene to polysomes. Actin cooperates with hnRNP U during the elongation of nascent pre-mRNA transcripts for recruitment of the HAT PCAF to active genes. Actin is further incorporated in pre-mRNPs/mRNPs in transit to the nuclear pore complex. Finally, there is evidence that actin follows mRNPs to the cytoplasm and may be required for mRNA export. However, at this stage there is no direct evidence that the actin-associated RNP is involved in mRNA localization on the actin cytoskeleton

Nuclear myosin species in RNA biogenesis

Actin and myosin consort as molecular motors in many cytoplasmic-based cellular functions. Therefore, the discovery that several myosin species are also present in the cell nucleus began to tickle people’s imaginations. If actin and myosin are both present in the cell nucleus, they may contribute to nuclear function as components of nuclear-based molecular motors in RNA biogenesis and even contribute to nuclear architecture. These ideas shed new lights on the biology of the cell nucleus and attracted a lot of interest, which significantly contributed to the development of this field over the past few years.

Evidence that myosin species are present in the cell nucleus dates back to early reports published in the 1970s (reviewed in [34]). Myosin, together with actin and tubulin, was found as the main non-histone component attached to chromatin, and it was therefore suggested that they could cooperate for chromosome condensation [42]. Actin and myosin were also proposed to be control elements in nucleocytoplasmic transport [43]. However, evidence that a specific form of myosin localized to the cell nucleus came from immune electron microscopy studies in mouse 3T3 cells where a general antibody to adrenal myosin 1 stained nucleoplasmic structures as well as nucleoli [44]. More recently, it has been demonstrated that there is a specific form of myosin 1 (NM1) that is localized to the cell nucleus [45]. It turns out that NM1 is an alternatively spliced variant of myosin 1 and exhibits a unique and conserved N-terminal epitope that seems to be responsible for its nuclear location [45, 46]. In the last few years, other myosin species were also identified in the cell nucleus. Myosin VI, the only member of the myosin superfamily that is known to move towards the minus end of actin filaments, was found to be required for RNA polymerase II transcription [34, 47]. On the other hand, myosin 16b and myosin Va were found to accumulate in splicing speckles in transcriptionally active cells [48, 49]. While overexpression of myosin 16b was found to affect DNA replication by inhibiting transition into S-phase, myosin Va relocalized to nucleoli upon transcription inhibition [48, 49].

Among the nuclear forms of myosin identified so far, the role of NM1 in nuclear function is the best characterized. NM1 has been shown to be directly involved in gene transcription (reviewed in [34]). In transcription of protein coding genes, there is in vitro evidence for a potential role of NM1 in the formation of the first phosphodiester bond [45, 50]. For rRNA genes, mechanistic clues came from the discovery that NM1 is a component of the chromatin remodeling complex B-WICH, required for RNA polymerase I transcription activation and maintenance [51]. Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated that NM1, similarly to actin, is located at both promoter and coding regions of rRNA genes. Since the actin–NM1 interaction and myosin-based motor activity are required for RNA polymerase I transcription [20, 52], NM1 was suggested to cooperate with actin as a molecular motor or rather as a component of fast and dynamic molecular switches for recruitment of RNA polymerase I co-activators to rRNA genes [53]. Since NM1 and WSTF are exclusively implicated in the post-initiation phases of transcription [51], the actin–NM1 interaction probably coordinates recruitment of co-activators to active rRNA genes for efficient pre-rRNA elongation (see Fig. 3) (reviewed in [34]). The recent observation that actin and NM1 are associated with transcribed as well as non-transcribed rDNA sequences further suggests an actin–NM1 synergy not only during the transcription process, but also in the establishment or maintenance of heterochromatin [52].

Fig. 3.

The role of actin and NM1 in rRNA biogenesis. a Schematic representation of the “molecular switch” model where the dynamic actin–NM1 interaction has been recently proposed to mediate recruitment of the chromatin remodeling B-WICH to active rRNA genes for efficient pre-rRNA elongation [20, 51, 53]. b Emerging evidence suggests that the B-WICH complex is added to nascent pre-rRNP complexes to facilitate rRNA remodeling [81]

Are the above mechanisms conserved in pol II transcription? At this stage, it is still an open question. However, one might envisage that multiple factors cooperate with actin throughout the elongation phase of pre-mRNA transcripts, and while the interaction between actin and the tripartite ATP-binding hnRNP U molecule is required during elongation, it is tempting to speculate that actin and NM1 may synergize as molecular motors, for instance at different stages of the transcription process.

Actin in pre-mRNP and mRNP particles

Evidence that actin is incorporated in nascent pre-mRNPs and remains associated with mature mRNPs released in the nucleoplasmic milieu came from studies performed in the dipteran insect C. tentans [30].

At the larval stage, C. tentans has large salivary glands with characteristic saddle-shaped cells arranged as monolayers. These cells contain four polytene chromosomes that can be easily isolated by microdissection techniques and used to perform in situ studies. Chromosome IV is of special interest because it exhibits three exceptionally large transcription sites, the BR genes, which display high transcriptional rates. These genes encode large salivary polypeptides that are secreted by the larvae in order to build their pupa and move on to the next developmental stage. Because of the exceptional size of the BR genes and the corresponding RNA transcripts generated, one can use immunoelectron microscopy on ultrathin sections of salivary glands or isolated chromosomes to visualize nascent BR pre-mRNA decorating the active transcription unit. Using ultrathin salivary gland sections, it is also possible to visualize mature BR mRNPs released in the nucleoplasm, those particles which are being exported through nuclear pores and the unwound RNA engaged in protein synthesis (reviewed in [54]). Several hnRNPs, splicing factors, RNA helicases and transport mediators have been identified as components of the BR RNPs, being added to nascent particles at different stages of the maturation process [55, 56]. These studies are rather important because they support the view that the fate of newly synthesized RNA is pre-determined already in the cell nucleus during assembly into RNP particles.

To test whether actin is added to the nascent RNA transcript, a polyclonal antibody was raised against a complex of actin with the monomeric G-actin-binding protein cofilin. The resulting serum against the cofilactin complex was affinity purified against actin [30]. This antibody homogeneously labeled transcription sites on isolated polytene chromosomes in an RNA-dependent manner, providing evidence that actin associates with nascent pre-mRNA. In addition, immunoelectron microscopy on ultrathin sections of C. tentans salivary glands using the same anti-actin antibody provided for the first time in situ evidence that actin associates not only with the BR pre-mRNA in status nascente, but it also becomes incorporated in nucleoplasmic BR mRNP particles [30]. These results were further corroborated by the discovery that actin is also present in the mammalian 40S pre-mRNP/mRNP fraction [31], altogether supporting the possibility that actin accompanies the mRNA through the entire RNA biogenesis pathway, from gene to polysomes (see Fig. 2 for a schematic representation). So far, there is no evidence that actin binds to the RNA directly, and therefore, if actin is assembled in RNP particles it is likely to interact with hnRNPs. In fact, a subset of actin-associated hnRNPs was recently identified both in C. tentans and in mammalian RNP particles [30, 31].

Immediately upon transcription, pre-messenger RNA molecules become associated with hnRNPs to form RNP complexes. These proteins and the message they carry have been extensively characterized [57, 58], and they are known to be involved in many aspects of RNA biogenesis. In human, for example, there are about 30 major components and a large number of minor ones [59]. For instance, they have been involved in splicing and 3′-end processing as well as nuclear RNA retention [60]. In addition a considerable subset of hnRNP proteins is known to undergo nucleocytoplasmic shuttling, hnRNP A1 probably being the best characterized example [61]. Because of these shuttling properties, it was proposed that hnRNP proteins mediate RNA transport, a view that was further substantiated by the discovery that the C. tentans hnRNP A1-like protein hrp36 travels with the RNA through the nuclear pore [62]. Subsequently, nuclear export signals, M9 in hnRNP A1 [63] and KNS in hnRNP K [64], were discovered, but it is not known whether these proteins bind directly to the nuclear pore complex or via a soluble receptor [65]. Furthermore, hnRNP proteins were also found to influence RNA stability, cytoplasmic localization and mRNA translation [66]. hnRNP C and hnRNP D affect mRNA stability by direct association with AU-rich elements [67–69], indicating an involvement of hnRNPs in mRNA turnover. For RNA targeting and localization to specific cytoplasmic locations, the Drosophila melanogaster hnRNP A1-like Squid protein (hrp40) governs the specific localization of the grk mRNA to the dorsoanterior corner of the oocyte during mid-oogenesis [70–72]. The Squid protein binds to the transcript in the cell nucleus prior to RNA transfer into the cytoplasm and is also essential for the localization of pair-rule segmentation gene transcripts to the apical cytoplasm in Drosophila blastoderm embryos [73]. In mammals, hnRNP A2 and the CArG box-binding factor CBF-A binds the MBP mRNA trafficking sequences (RTS), and they are required for cytoplasmic MBP mRNA transport to the distal ends of oligodendrocytes processes [74–76].

Altogether the above observations indicate that hnRNPs are essential transacting factors for efficient RNA biogenesis. It was therefore a significant discovery when a proteomic study performed on the 40S pre-mRNP/mRNP fraction isolated from rat liver extracts and subjected to DNase I affinity chromatography demonstrated that actin associates with the shuttling A/B-type hnRNP proteins hnRNP A2/B1, hnRNP A3, CBF-A as well as hnRNP U [29, 31]. Given the importance of hnRNPs in gene expression, these findings suggested multiple key roles for actin through the RNA biogenesis pathway, both in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm. As discussed earlier, actin and hnRNP U interact to promote recruitment of the HAT PCAF to active genes [39]. hnRNP U is a general component of nuclear RNP particles, and it is one of those hnRNPs that probably accompanies the mRNA all the way to the cytoplasm, as it is also found in cytoplasmic RNP granules isolated from adult mouse brain [77]. It is interesting to find out that another actin-associated protein, the HAT PCAF, is also associated with nuclear RNP complexes [39] (see also Fig. 2). Similarly to actin and hnRNP U, PCAF binds to nascent mRNA transcripts as revealed by chromatin RNA immunoprecipitation experiments and displays a nuclear distribution that is sensitive to RNase treatment performed on living cells [39], suggesting that actin, hnRNP U and PCAF are integrated in the same pre-mRNP and mRNP particles. These considerations emphasize that both RNA-binding proteins and non-RNA-binding proteins associate with actin for RNP assembly and packaging. The role of the RNP-associated PCAF is still unclear, but it may be important to modulate the interaction of actin with hnRNP U or other RNP components through its acetylation activity [31].

Throughout the gene expression pathway, actin is not only involved in transcription, RNP assembly and transport. There is also evidence that an intact cytoskeleton is required for cytoplasmic mRNA localization and translation [78, 79]. The direct interaction between actin and CBF-A observed both in the nucleus and cytoplasm goes along these lines since it could be important to control cytoplasmic events during RNA biogenesis. Based on the role of the shuttling hnRNP CBF-A in cytoplasmic mRNA transport and localization [76], actin and CBF-A may cooperate to control assembly of the RNA into large transported granules as well as trafficking and localization (see Fig. 2). These ideas remain to be proven, but the potential involvement of actin in these processes together with hnRNP proteins was partly suggested by the discovery that the general RNA-binding protein p50—which is added co-transcriptionally to nascent RNP particles and associates with the translational apparatus—interacts with polymeric F-actin in the cytoplasm [80].

In summary, the present data indicate that specific actin–hnRNP interactions are co-transcriptionally established, and they are important at multiple levels during RNA biogenesis from gene to polysomes. These interactions may be regulated by non-RNA-binding proteins integrated in the same pre-mRNP and mRNP complexes.

Nuclear myosin 1 in ribosomal ribonucleoprotein complexes

The presence of NM1 in ribosomal RNP complexes is also an emerging and rather attractive possibility. As mentioned earlier, chromatin immunoprecipitation assays and in vitro transcription experiments demonstrated that NM1 is present on the rRNA gene coding region, and it is required for pol I transcription elongation [28, 52]. In addition there is evidence that the intranuclear distribution of NM1 is sensitive to RNase treatment [20] and that the B-WICH complex contains precursor rRNA [51, 81]. These results altogether suggest that a considerable fraction of NM1 may be co-transcriptionally added to nascent pre-rRNA particles, remaining associated with nucleoplasmic rRNP complexes presumably with other core components of B-WICH. Similar considerations may be extended to mRNPs since NM1 and actin were also co-localized very close to active nucleoplasmic transcription sites by immune electron microscopy [82], but at this stage there is no evidence that NM1 associates with pre-mRNA molecules.

Transcription of rRNA genes occurs in nucleoli. The newly synthesized precursor RNA is modified and cleaved in the external transcribed spacer (ETS) and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences to obtain mature 18S, 5.8S and 28S rRNA. These transcripts are subsequently assembled into pre-ribosomal subunits. For many years transcription of rRNA genes and processing of the precursor molecule were considered to take place separately. However, these two steps in gene expression could occur concomitantly and, above all, be co-regulated. Studies in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae indicated that rDNA transcription requires a subset of components of the pre-rRNA processing machinery (see [18] and references therein), further supporting the view that pre-rRNA processing and RNA polymerase I transcription are coordinated events. A large proportion of cellular metabolism is dedicated to ribosome biogenesis and therefore, similarly to yeast, it is likely that co-transcriptional processing of pre-rRNA takes place also in mammals where coordination of transcription and processing may be facilitated by the large set of non-ribosomal proteins involved throughout the rRNA biogenesis pathway.

NM1 may contribute to the delicate task depicted above since it associates with active rRNA genes, it is required for RNA polymerase I transcription and interacts with 45S pre-rRNA as a core component of the B-WICH complex. One interesting possibility is that NM1 acts as a link between RNA polymerase I transcription and pre-rRNA processing, for instance by mediating structural alterations of nascent pre-rRNPs. Evidence in support of this attractive and dynamic scenario comes not only from the association of NM1 with the remodeling factors WSTF and SNF2h, but also from the discovery that B-WICH contains the RNA helicase II/GUα or DDX21 [81], a member of the DExD/H box proteins, which is involved in both transcriptional regulation and pre-rRNA processing [83]. In Xenopus laevis oocytes down-regulation of RNA helicase II/GUα was found to inhibit processing of 20S rRNA to 18S rRNA and also results in the depletion of 28S rRNA [84]. Similarly, in mammals silencing of RNA helicase II/GUα inhibited rRNA production [85]. During rRNA biogenesis, multiple factors associate transiently with pre-rRNA, including small nucleolar RNPs (snoRNPs) as well as a wide range of non-ribosomal proteins that process and modify precursor rRNA molecules (e.g., endo- and exonucleases, pseudouridine synthases or methyltransferases), mediate RNP folding/remodeling (RNA helicases, RNA chaperones) or facilitate protein association/dissociation (GTPases, AAA-ATPases). Since the RNA helicase II/GUα is also associated with the B-WICH complex, its essential role in rRNA biogenesis may be modulated by NM1 through a mechanism that facilitates loading of RNA helicases and remodeling factors on pre-rRNA for efficient processing.

If the nucleoplasmic distribution of NM1 is sensitive to RNase treatment and a fraction of NM1 associates with precursor rRNA [20, 81], one can also imagine that NM1 remains associated with mature 18S and 28S rRNA transcripts during nucleolar assembly of pre-ribosomal subunits, following them all the way to the nuclear envelope and nuclear pore complex. This hypothesis was partly suggested in a recent study performed at the ultrastructural level where it was demonstrated that NM1 is indeed added to pre-ribosomal subunits that are in transit to the nuclear pores [86]. Consistently, NM1 was identified at the nuclear envelope associated with emerin, a protein known to bind lamins and to cap the pointed ends of actin filaments [87]. Early reports also showed that certain myosin species are probably present at the nuclear pore complex [88, 89], a possibility that is suggested by initial evidence that RNA-associated NM1 localizes to the basket of the nuclear pore (own unpublished data). Therefore, it is likely that NM1 is involved in post-transcriptional events during rRNA biogenesis. In the yeast S. cerevisiae, myosin-like proteins (Mlp) have already been shown to establish a link between mRNA synthesis and nuclear export [90, 91]. In higher vertebrates, NM1 is necessary for RNA polymerase I transcription activation and elongation [51], it associates with pre-rRNA [81], it is incorporated in pre-ribosomal subunits [86], and it is present at the nuclear envelope and presumably, at the nuclear pore complex. Therefore, NM1 represents an ideal candidate to link RNA polymerase I transcription, pre-rRNA processing and export of pre-ribosomal subunits in mammals. NM1 may coordinate these different phases of rRNA biogenesis by facilitating association and disassociation of pre-rRNA processing and remodeling factors to obtain export-competent pre-ribosomal subunits, thus implementing quality control mechanisms (see Fig. 3).

In the cytoplasm, specific mRNA transcripts are asymmetrically distributed for cellular function. This property is achieved by linking the RNA to molecular motors that walk along the cytoskeleton. In S. cerevisiae RNA-motor association requires an RNA-binding adaptor protein that links a myosin motor to specific ribonucleoproteins, and, more generally speaking, certain mRNAs are transported as large granules along the cytoskeleton by the molecular motors dynein, kinesin or myosin [92]. At this stage we do not know whether in the cell nucleus NM1 binds directly to rRNA transcripts or its association with the RNA is mediated by specific RNA-binding proteins. It is also unclear whether NM1 cooperates with actin during pre-rRNA processing and ribosomal subunit biogenesis. It is, however, intriguing that both actin and NM1 associate with nuclear RNA helicases involved in rRNA processing [81, 93, 94], observations that suggest that actin and NM1 may function together not only on the rRNA gene for RNA polymerase I transcription, but also in the post-transcriptional control of rRNA biogenesis.

The above scenarios require further analysis at the molecular level. In either case, several observations presently suggest that NM1 accompanies rRNA from the gene to nuclear pore complex (Fig. 4), with the potential to link multiple phases of rRNA biogenesis.

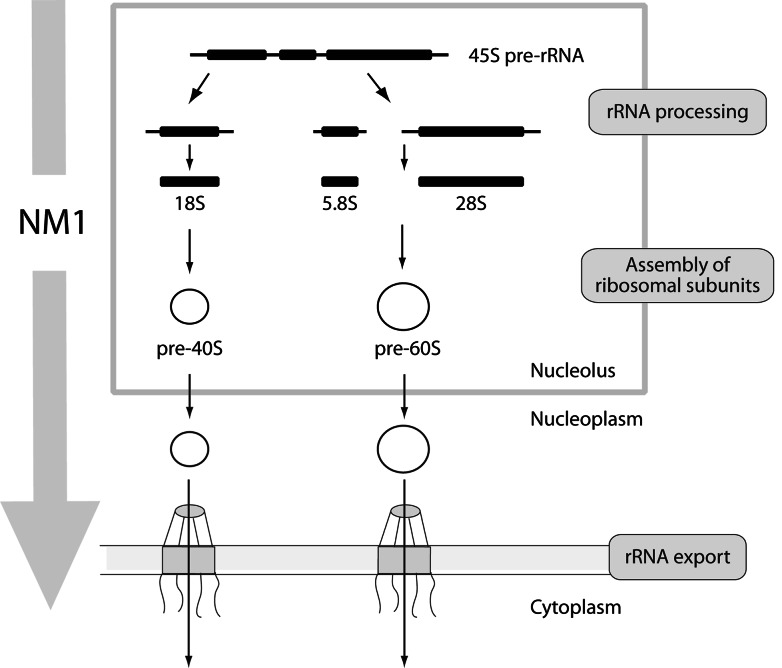

Fig. 4.

Proposed model for the involvement of NM1 in post-transcriptional control of rRNA biogenesis. After being incorporated in nascent pre-rRNA complexes, NM1 is likely to accompany the rRNA transcripts through processing, assembly into pre-ribosomal subunits and transport to the nuclear pore complex. Given its role in RNA polymerase I transcription, it is possible that NM1 links transcription with processing and transport by implementing quality control mechanisms for efficient rRNA biogenesis

Co-transcriptional assembly of actin and myosin into ribonucleoprotein particles

The discoveries that actin is a component of mRNPs and NM1 associates with pre-rRNA suggest multiple regulatory functions in post-transcriptional control of gene expression are interesting [30, 31, 39, 81], but also raise numerous questions. For instance, are actin and myosin implicated in independent functions? Do they possibly function as molecular motors or switches during maturation and nucleoplasmic transport of mRNPs and rRNPs? Currently, it is not known whether nuclear actin and myosin species co-exist in the same RNPs. Second, there is no evidence in support of synergistic actions of actin and myosin as molecular motors for active nucleoplasmic RNP transport to the nuclear pore complex. BrUTP labeling experiments performed in combination with immune electron microscopy on ultrathin sections of C. tentans salivary gland cells demonstrated that newly synthesized BR RNP particles are distributed all over in the nucleoplasm, consistent with a random type of movement in the interchromosomal space [96]. Similarly, recent quantitative analysis performed in living mammalian cells on a single mRNP particle showed that the energetic requirements of nuclear mRNP trafficking are consistent with a diffusional model [97]. Analogous conclusions were obtained when studying larger particles, such as ribosomal RNPs and pre-ribosomal subunits. It was found out that pre-ribosomal subunits moving out from nucleolus into the nucleoplasm were not transported along directed paths. They displayed low mobility consistently with random movement and anomalous diffusion [98]. Altogether these investigations speak against the possibility that actin and myosin consort as canonical molecular motors to facilitate intranuclear trafficking of RNPs.

If actin and myosin are not implicated in active RNP transport, can they really cooperate to control RNA biogenesis at the post-transcriptional level? Considering that the nucleoplasmic localization of actin is heavily sensitive to RNase treatment [39], one should not exclude the possibility that actin is also added to pre-ribosomal subunits. Should this be the case, actin and NM1 may functionally consort in the multiple maturation stages of pre-ribosomal subunits in transit to the nuclear pore when there is a continuous requirement to mediate association and disassociation of factors involved in rRNA processing and remodeling. Actin is also present in pore-linked filaments that project inward from the basket of the nuclear pore well into the nucleoplasm and have been seen to crosslink adjacent nuclear pore complexes from the nucleoplasmic side [95]. The dynamic interaction between NM1 in pre-ribosomal subunits and actin in the pore-linked filaments may contribute to the loading of export-competent pre-ribosomal subunits at the nuclear pore basket prior to CRM1-mediated nuclear export. Both scenarios are speculative. However, it likely that these mechanisms are significantly affected by dynamic changes in the polymerization states of nuclear actin.

Monomeric and polymeric actin during RNA biogenesis

The cell nucleus contains many of those factors that are known to modulate the equilibrium between monomeric and polymeric actin (see Table 1). Therefore, it is plausible that throughout the different phases of RNA biogenesis, actin exhibits alterations in its polymerization state, and these changes may well have a functional significance.

At the moment we have not identified a general framework on the equilibrium between monomeric, oligomeric and polymeric actin forms in the cell nucleus. One of the obstacles is the lack of tools that allow direct visualization of nuclear actin by light microscopy. Fluorochrome-conjugated phalloidin does not label nuclear actin structures, and it is difficult to perform experiments with GFP-actin constructs expressed in cultured cells since most of the GFP-conjugated actin is incorporated in the cytoskeleton. In either case, there is an indication that in the cell nucleus polymeric and monomeric or short oligomeric forms of actin co-exist (see [99, 100]). The presence of polymeric actin was recently investigated in living cells using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP). These experiments provided evidence that nuclear actin and actin-containing complexes have low mobility, suggesting that actin could be assembled into higher order structures. In addition, a large proportion of nuclear actin displayed properties that are consistent with polymeric actin, including a high degree of turn-over [101]. Indirect evidence for the presence of monomeric or short oligomeric actin and polymeric actin also came from the discovery that the cell nucleus hosts both G-actin-binding proteins [102–112] and F-actin-binding proteins [113–117] (see Table 1). Some of these proteins that are known to regulate actin polymerization were shown to have a direct role in certain aspects of RNA biogenesis. For instance, N-WASP and the ARP2/3 complex are known to cooperate to stabilize actin filaments and promote branching. These proteins were recently found to be important for RNA polymerase II transcription elongation [115, 116], consistent with the view that actin polymerization may be required to enhance the processivity of RNA polymerase II [34]. Roles for monomeric actin in serum response factor (SRF)-dependent RNA polymerase II transcription and for the G-actin-binding proteins profilin and cofilin in RNA polymerase I transcription were also investigated in recent studies [52, 118]. Consistent with the possibility of ongoing co-transcriptional polymerization of actin, addition of profilin to in vitro transcription assays did not affect elongation of rRNA transcripts. On the contrary, an opposite effect was observed when purified cofilin was added to the in vitro transcription reactions [52]. When interacting with G-actin, profilin is known to occupy an actin–actin contact site and sequesters actin from the pool of actin monomers. Profilin also catalyzes the exchange of ADP-actin to the polymerization competent ATP-actin. Therefore, if anything, profilin represents a source of readily polymerizing ATP-actin monomers that are fed into growing actin polymers by proteins such as WASP. Cofilin is also a G-actin-binding protein that is required for the reorganization of actin filaments. In fact, the actin depolymerizing factor (ADF)/cofilin binds G-actin monomers and stimulates depolymerization of actin filaments through severing and through increasing off-rates for actin monomers from the pointed end [119, 120]. Cofilin cooperates with ARP2/3 to reorganize actin filaments. Therefore, the finding that cofilin negatively regulates pol I transcription may be consistent with a mechanism of actin polymerization that is conserved from cytoplasm to nucleus where it is required for efficient transcription and presumably other nuclear functions.

Early studies also provided genetic evidence that formin homology (FH) proteins or formins are present in the cell nucleus [117]. In eukaryotes, formins were only believed to be molecular scaffolds that indirectly affected cellular functions through the binding of other proteins. However, recent in vitro studies demonstrated that they can function as actin nucleators in the formation of new filaments [121], altogether suggesting that there are different nuclear mechanisms that may co-exist to control actin polymerization. In either case, the presence of nuclear mechanisms that control actin polymerization is consistent with actin-based molecular motors coupled to multiple phases of RNA biogenesis (see Fig. 5) [34, 53]. This leads to the question of how nuclear actin polymerization and actomyosin complex formation are regulated. In the cytoplasm the GTPase RhoA controls actomyosin assembly, and it is important to control cytokinesis. The activated Rho stimulates myosin activation as well as actin polymerization, and it is in turn regulated by GTP exchange factors (GEFs) and several kinases. Are any of these mechanisms conserved in the cell nucleus? At this stage, this idea is rather attractive, but remains speculative. However, there is emerging evidence that RhoA- and RhoA-regulating factors are present in the nucleus. The RhoA exchange factor Net1 was recently found to modulate tumor suppressor activity [122]. Recent evidence obtained in gastric cancer cells demonstrated that RhoA is found at the cell membrane and throughout the cytosol and displays distinctive nucleolar localization that is enhanced upon induction of cellular proliferation [123]. Even though future work is required, these initial observations suggest a potential role for these factors in controlling gene expression at steady state, perhaps by regulating the polymerization state of the transcription-competent actin and assembly of the actomyosin complex (see Fig. 5). In the above scenario, it will be really interesting to determine whether actin polymerization readily occurs along active genes for efficient transcription, with the extent of actin polymerization correlating with gene expression levels.

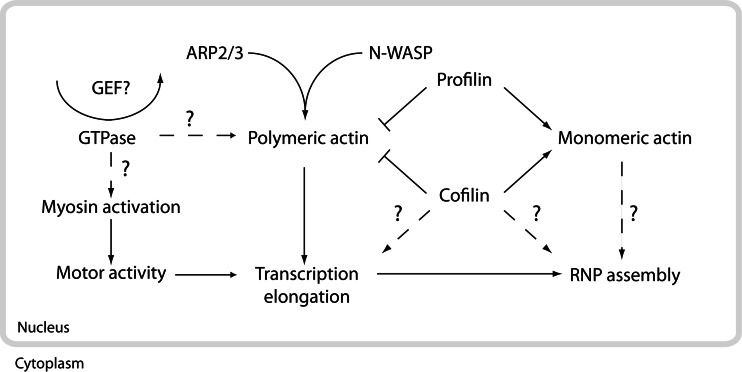

Fig. 5.

An integrative model illustrating how the different polymerization states of nuclear actin may affect nuclear function. N-WASP and ARP2/3 are likely to cooperate in order to stabilize polymeric actin during transcription elongation, while the monomeric actin pool may be continuously replenished by the combined action of cofilin and profilin. In this context the role of nuclear GTPases has not been investigated yet. However, other mechanisms should also be considered in the modulation of the fine balance between monomeric and polymeric nuclear actin, given for instance genetic evidence that formins and formin-like proteins are present in the cell nucleus

What happens then to the state of actin polymerization when the newly synthesized RNA, incorporated in RNPs, is cleaved from the gene? Immune electron microscopy experiments preformed in situ on C. tentans salivary gland ultrathin sections indeed showed that actin is incorporated in mature RNPs, but failed to provide evidence of canonical filamentous actin structures [30]. In addition, DNase I affinity chromatography precipitated actin from RNP preparations [31], suggesting that in RNPs actin is in a monomeric or short oligomeric form. Therefore, if actin polymerization is required for transcription elongation and perhaps termination, one might also anticipate an actin depolymerization mechanism that takes place upon RNP assembly and maintains actin in a depolymerised form. Within the RNP this scenario may be achieved by incorporating G-actin-binding proteins such as cofilin or by covalent modifications on the RNP-incorporated actin or actin binding proteins that impair the actin polymerization process. These are speculative models. However, there is evidence that actin binding to hnRNP U occurs only when the two proteins are on the gene coding region and are no longer sitting at the promoter [39], suggesting that covalent modifications on actin and hnRNP U may affect their abilities to bind to each other along the gene and during incorporation within the newly assembled RNP particle. This type of mechanism that has the potential to preclude actin from polymerizing in the RNP may also be used to stimulate polymerization during export and unwinding of the RNP for cytoplasmic mRNA localization.

On the importance of being promiscuous during RNA biogenesis

The multiple roles in gene expression where actin is directly involved feature dynamic associations and disassociations of multiprotein complexes or molecular machines. We like the idea that these dynamic networks are partly mediated by the regulated set of protein–protein interactions between actin and actin-binding proteins. For instance, this is the case for the transcription apparatus, which interacts with actin in multiple ways and also applies to chromatin-modifying complexes where actin and actin related proteins have been considered already for some years as histone chaperones (see [124, 125]). We can expand this scenario to the crosstalk between chromatin-modifying complexes and transcription apparatus where the interaction between actin and hnRNPs or myosin is important for co-transcriptional recruitment of HATs and chromatin remodeling complexes. Altogether this implies that actin, a rather uncommitted molecule (at least from a structural point of view), has to be able to entertain some serious “molecular talking” with many other proteins in order to become engaged in multiple regulatory functions.

We are only beginning to understand these regulatory networks in RNA biogenesis. Of course in the cytoplasm actin is engaged in complex networks of protein–protein interactions with a large number of proteins, and it is required in most cellular processes. These proteins regulate actin polymerization, and they are implicated in various intracellular signaling pathways. We propose that a similar landscape takes shape in the cell nucleus with the difference that in the nucleus RNA transcripts and their secondary structure alterations may be important to stabilize actin-mediated protein–protein interactions. Many proteins have already been identified that interact with actin for different reasons and in different contexts. The synergistic action of actin and myosin and all the proteins that regulate their motor activity has been accepted as an essential mechanism to promote RNA biogenesis at the transcriptional level. There are several open questions. We do not know how these mechanisms are regulated or deregulated, whether they are used at the post-transcriptional level, how gene expression profiles are affected locally and globally and how they are integrated into the functional architecture of the cell nucleus. There is evidence that spectrin repeat containing proteins, which bind actin and have a role in the establishment of cell structure, are also present in the nucleus [126–138]. Further analysis is required, but it is interesting to suggest that these proteins may cooperate with actin to integrate RNA biogenesis pathways within the structure of the cell nucleus.

Concluding remarks

Some of the molecular mechanisms underlying actin function in transcription have been recently unraveled, but we still have limited insights into how actin controls the later phases of gene expression and, above all, how actin polymerization is regulated from the nucleus to cytoplasm, affecting multiple phases of RNA biogenesis. Moreover, what are the mechanisms that allow nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the actin molecule? How is actin imported in the cell nucleus? We do not know whether this is an active process or perhaps actin simply remains trapped in the cell nucleus at the end of cell division through tight interactions with histones. On the other hand, while there is evidence that actin has functional nuclear export sequences [139], a somewhat conflicting report indicated that at least a fraction of nuclear actin is exported in complex with profilin in an exportin-dependent manner [140], a potential homeostatic mechanism that would guarantee the proper levels of actin in the cell nucleus. However, it is likely that the majority of nuclear actin is exported as part of cargos. This idea is supported by the fact that actin accompanies RNA from the gene to polysomes as a component of RNP complexes and anti-actin antibodies interfere with the export of viral mRNA in X. laevis oocytes [30, 32].

In this rapidly developing area of research, we have probably managed to scrape the tip of the iceberg with many questions that still need to be addressed. Perhaps one way of addressing these questions is to start identifying the nuclear actin proteome. In either case, actin is likely to contribute to the correct flow of RNA from gene to polysomes as an essential allosteric regulator of protein–protein interactions facilitating the crosstalk between the specialized molecular machines involved throughout the multiple phases of RNA biogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet) and the Swedish Cancer Society (Cancerfonden).

References

- 1.Schneider R, Grosschedl R. Dynamics and interplay of nuclear architecture, genome organization, and gene expression. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3027–3043. doi: 10.1101/gad.1604607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sexton T, Umlauf D, Kurukuti S, Fraser P. The role of transcription factories in large-scale structure and dynamics of interphase chromatin. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:691–697. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter DRF, Eskiw C, Cook P. Transcription factories. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36:585–589. doi: 10.1042/BST0360585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groth A, Rocha W, Verreault A, Almouzni G. Chromatin challenges during DNA replication and repair. Cell. 2007;128:721–733. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell. 2007;128:707–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howe KJ. RNA polymerase II conducts a symphony of pre-mRNA processing activities. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1577:308–324. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00460-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allemand E, Batsché E, Muchardt C. Splicing, transcription, and chromatin: a ménage à trois. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batsché E, Yaniv M, Muchardt C. The human SWI/SNF subunit Brm is a regulator of alternative splicing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:22–29. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wetterberg I, Zhao J, Masich S, Wieslander L, Skoglund U. In situ transcription and splicing in the Balbiani ring 3 gene. EMBO J. 2001;20:2564–2574. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kornblihtt AR. Coupling transcription and alternative splicing. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;623:175–189. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-77374-2_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neugebauer KM. On the importance of being co-transcriptional. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3865–3871. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aguilera A. Cotranscriptional mRNP assembly: from the DNA to the nuclear pore. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bentley DL. Rules of engagement: co-transcriptional recruitment of pre-mRNA processing factors. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirose Y, Manley JL. RNA polymerase II and the integration of nuclear events. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1415–1429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maniatis T, Reed R. An extensive network of coupling among gene expression machines. Nature. 2002;416:499–506. doi: 10.1038/416499a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Proudfoot NJ, Furger A, Dye MJ. Integrating mRNA processing with transcription. Cell. 2002;108:501–512. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00617-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zorio DA, Bentley DL. The link between mRNA processing and transcription: communication works both ways. Exp Cell Res. 2004;296:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Granneman S, Baserga SJ. Crosstalk in gene expression: coupling and co-regulation of rDNA transcription, pre-ribosome assembly and pre-rRNA processing. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shav-Tal Y, Singer RH. RNA localization. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4077–4081. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fomproix N, Percipalle P. An actin–myosin complex on actively transcribing genes. Exp Cell Res. 2004;294:140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saitoh N, Spahr CS, Patterson SD, Bubulya P, Neuwald AF, Spector DL. Proteomic analysis of interchromatin granule clusters. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3876–3890. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chuang CH, Carpenter AE, Fuchsova B, Johnson T, de Lanerolle P, Belmont AS. Long-range directional movement of an interphase chromosome site. Curr Biol. 2006;16:825–831. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dundr M, Ospina JK, Sung M-H, John S, Upender M, Reid T, Hager GL, Matera AG. Actin-dependent intranuclear repositioning of an active gene locus in vivo. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:1095–1103. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200710058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao K, Wang W, Rando OJ, Xue Y, Swiderek K, Kuo A, Crabtree GR. Rapid and phosphoinositol-dependent binding of the SWI/SNF-like BAF complex to chromatin after T lymphocyte receptor signaling. Cell. 1998;95:625–636. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81633-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Percipalle P, Fomproix N, Kylberg K, Miralles F, Bjorkroth B, Daneholt B, Visa N. An actin–ribonucleoprotein interaction is involved in transcription by RNA polymerase II. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6475–6480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1131933100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofmann WA, Stojiljkovic L, Fuchsova B, Vargas GM, Mavrommatis E, Philimonenko V, Kysela K, Goodrich JA, Lessard JL, Hope TJ, Hozak P, de Lanerolle P. Actin is part of pre-initiation complexes and is necessary for transcription by RNA polymerase II. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1094–1101. doi: 10.1038/ncb1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu P, Wu S, Hernandez N. A role for beta-actin in RNA polymerase III transcription. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3010–3015. doi: 10.1101/gad.1250804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Philimonenko VV, Zhao J, Iben S, Dingova H, Kysela K, Kahle M, Zentgraf H, Hofmann WA, de Lanerolle P, Hozak P, Grummt I. Nuclear actin and myosin I are required for RNA polymerase I transcription. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1165–1171. doi: 10.1038/ncb1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kukalev A, Nord Y, Palmberg C, Bergman T, Percipalle P. Actin and hnRNP U cooperate for productive transcription by RNA polymerase II. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:238–244. doi: 10.1038/nsmb904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Percipalle P, Zhao J, Pope B, Weeds A, Lindberg U, Daneholt B. Actin bound to the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein hrp36 is associated with Balbiani ring mRNA from the gene to polysomes. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:229–236. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.1.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Percipalle P, Jonsson A, Nashchekin D, Karlsson C, Bergman T, Guialis A, Daneholt B. Nuclear actin is associated with a specific subset of hnRNP A/B-type proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1725–1734. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.8.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hofmann WA, Reichart B, Ewald A, Muller E, Schmitt I, Stauber RH, Lottspeich F, Jockusch BM, Scheer U, Hauber J, Dabauvalle MC. Cofactor requirements for nuclear export of Rev response element (RRE)- and constitutive transport element (CTE)-containing retroviral RNAs. An unexpected role for actin. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:895–910. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.5.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Östlund Farrants A-K. Chromatin remodelling and actin organization. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2041–2050. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Louvet E, Percipalle P. Actin and myosin in gene transcription. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2009;272:107–147. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(08)01603-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scheer U, Hinssen H, Franke WW, Jockusch BM. Microinjection of actin-binding proteins and actin antibodies demonstrates involvement of nuclear actin in transcription of lampbrush chromosomes. Cell. 1984;39:111–122. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Egly JM, Miyamoto NG, Moncollin V, Chambon P. Is actin a transcription initiation factor for RNA polymerase B? EMBO J. 1984;3:2363–2371. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02141.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Percipalle P, Visa N. Molecular functions of nuclear actin in transcription. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:967–971. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grummt I. Actin and myosin as transcription factors. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Obrdlik A, Kukalev A, Louvet E, Farrants AK, Caputo L, Percipalle P. The histone acetyltransferase PCAF associates with actin and hnRNP U for RNA polymerase II transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6342–6357. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00766-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schramm L, Hernandez N. Recruitment of RNA polymerase III to its target promoters. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2593–2620. doi: 10.1101/gad.1018902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sjölinder M, Björk P, Soderberg E, Sabri N, Östlund Farrants A-K, Visa N. The growing pre-mRNA recruits actin and chromatin-modifying factors to transcriptionally active genes. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1871–1884. doi: 10.1101/gad.339405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Comings DE, Okada TA. Fine structure of the heterochromatin of the kangaroo rat Dipodomys ordii, and examination of the possible role of actin and myosin in heterochromatin condensation. J Cell Sci. 1976;21:465–477. doi: 10.1242/jcs.21.3.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schindler M, Jiang L-W. Nuclear actin and myosin as control elements in nucleocytoplasmic transport. J Cell Biol. 1986;102:859–862. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.3.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nowak G, Pestic-Dragovich L, Hozák P, Philimonenko A, Simerly C, Schatten G, de Lanerolle P. Evidence for the presence of myosin I in the nucleus. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17176–17181. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.17176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pestic-Dragovich L, Stojiljkovic L, Philimonenko AA, Nowak G, Ke Y, Settlage RE, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Hozak P, de Lanerolle P. A myosin I isoform in the nucleus. Science. 2000;290:337–341. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5490.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kahle M, Pridalova J, Spacek M, Dzijak R, Hozak P. Nuclear myosin is ubiquitously expressed and evolutionary conserved in vertebrates. Histochem Cell Biol. 2007;127:139–148. doi: 10.1007/s00418-006-0231-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vreugde S, Ferrai C, Miluzio A, Hauben E, Marchisio PC, Crippa MP, Bussi M, Biffo S. Nuclear myosin VI enhances RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription. Mol Cell. 2006;23:749–755. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cameron RS, Liu C, Mixon AS, Pihkala JP, Rahn RJ, Cameron PL. Myosin16b: the COOH-tail region directs localization to the nucleus and overexpression delays S-phase progression. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2007;64:19–48. doi: 10.1002/cm.20162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pranchevicius MCS, Baqui MMA, Ishikawa-Ankerhold HC, Lourenço EV, Leão RM, Banzi SR, Tavares dos Santos C, Barreira MCR, Espreafico EM, Larson RE. Myosin Va phosphorylated on Ser1650 is found in nuclear speckles and redistributes to nucleoli upon inhibition of transcription. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2008;65:441–456. doi: 10.1002/cm.20269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hofmann WA, Vargas GM, Ramchandran R, Stojiljkovic L, Goodrich JA, de Lanerolle P. Nuclear myosin I is necessary for the formation of the first phosphodiester bond during transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II. J Cell Biochem. 2006;99:1001–1009. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Percipalle P, Fomproix N, Cavellán E, Voit R, Reimer G, Krüger T, Thyberg J, Scheer U, Grummt I, Farrants AK. The chromatin remodelling complex WSTF–SNF2h interacts with nuclear myosin 1 and has a role in RNA polymerase I transcription. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:525–530. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ye J, Zhao J, Hoffmann-Rohrer U, Grummt I. Nuclear myosin I acts in concert with polymeric actin to drive RNA polymerase I transcription. Genes Dev. 2008;22:322–330. doi: 10.1101/gad.455908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Percipalle P, Östlund Farrants AK. Chromatin remodelling and transcription: be-WICHed by nuclear myosin 1. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kiesler E, Visa N. Intranuclear pre-mRNA trafficking in an insect model system. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2004;35:99–118. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-74266-1_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Daneholt B. A look at messenger RNP moving through the nuclear pore. Cell. 1997;88:585–588. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81900-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daneholt B. Assembly and transport of a premessenger RNP particle. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:7012–7017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111145498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dreyfuss G, Matunis MJ, Piñol-Roma S, Burd CG. hnRNP proteins and the biogenesis of mRNA. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:289–321. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dreyfuss G, Kim VN, Kataoka N. Messenger-RNA-binding proteins and the messages they carry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:195–205. doi: 10.1038/nrm760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krecic AM, Swanson MS. hnRNP complexes: composition, structure, and function. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:363–371. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nakielny S, Dreyfuss G. The hnRNP C proteins contain a nuclear retention sequence that can override nuclear export signals. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:1365–1373. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.6.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Piñol-Roma S, Dreyfuss G. Shuttling of pre-mRNA binding proteins between nucleus and cytoplasm. Nature. 1992;355:730–732. doi: 10.1038/355730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Visa N, Alzhanova-Ericsson AT, Sun X, Kiseleva E, Björkroth B, Wurtz T, Daneholt B. A pre-mRNA-binding protein accompanies the RNA from the gene through the nuclear pores and into polysomes. Cell. 1996;84:253–264. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80980-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Michael WM, Choi M, Dreyfuss G. A nuclear export signal in hnRNP A1: a signal-mediated, temperature-dependent nuclear protein export pathway. Cell. 1995;83:415–422. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Michael WM, Eder PS, Dreyfuss G. The K nuclear shuttling domain: a novel signal for nuclear import and nuclear export in the hnRNP K protein. EMBO J. 1997;16:3587–3598. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nakielny S, Dreyfuss G. Transport of proteins and RNAs in and out of the nucleus. Cell. 1999;99:677–690. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81666-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Svitkin YV, Ovchinnikov LP, Dreyfuss G, Sonenberg N. General RNA binding proteins render translation cap dependent. EMBO J. 1996;15:7147–7155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zaidi S, Malter JS. Nucleolin and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C proteins specifically interact with the 3′-untranslated region of amyloid protein precursor mRNA. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17292–17298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kiledjian M, DeMaria CT, Brewer G, Novick K. Identification of AUF1 (heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein D) as a component of the α-globin mRNA stability complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4870–4876. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Loflin P, Chen C-YA, Shyu A-B. Unraveling a cytoplasmic role for hnRNP D in the in vivo mRNA destabilization directed by the AU-rich element. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1884–1897. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.14.1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kelley RL. Initial organization of the Drosophila dorsoventral axis depends on an RNA-binding protein encoded by the squid gene. Genes Dev. 1993;7:948–960. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.6.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Matunis EL, Kelley RL, Dreyfuss G. Essential role for a heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) in oogenesis: hrp40 is absent form the germ line in the dorso-ventral mutant squid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2781–2784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Neuman-Silberberg FS, Schüpbach T. The Drosophila dorsoventral patterning gene gurken produces a dorsally localized RNA and encodes a TGFα-like protein. Cell. 1993;75:165–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lall S, Francis-Lang H, Flament A, Norvell A, Schüpbach T, Ish-Horowicz D. Squid hnRNP protein promotes apical cytoplasmic transport and localization of Drosophila pair-rule transcripts. Cell. 1999;98:171–180. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hoek KS, Kidd GJ, Carson JH, Smith R. hnRNP A2 selectively binds the cytoplasmic transport sequence of myelin basic protein mRNA. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7021–7029. doi: 10.1021/bi9800247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kwon S, Barbarese E, Carson JH. The cis-acting RNA trafficking signal from myelin basic protein mRNA and its cognate trans-acting ligand hnRNP A2 enhance cap-dependent translation. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:247–256. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.2.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Raju CS, Göritz C, Nord Y, Hermanson O, Lopez-Iglesias C, Visa N, Castelo-Branco G, Percipalle P. In cultured oligodendrocytes the A/B-type hnRNP CBF-A accompanies MBP mRNA bound to mRNA trafficking sequences. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:3008–3018. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-10-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Elvira G, Wasiak S, Blandford V, Tong XK, Serrano A, Fan X, del Rayo Sánchez-Carbente M, Servant F, Bell AW, Boismenu D, Lacaille JC, McPherson PS, DesGroseillers L, Sossin WS. Characterization of an RNA granule from developing brain. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:635–651. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500255-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stapulionis R, Kolli S, Deutscher MP. Efficient mammalian protein synthesis requires an intact F-actin system. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24980–24986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rodriguez AJ, Czaplinski K, Condeelis JS, Singer RH. Mechanisms and cellular roles of local protein synthesis in mammalian cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ruzanov PV, Evdokimova VM, Korneeva NL, Hershey JWB, Ovchinnikov LP. Interaction of the universal mRNA-binding protein, p50, with actin: a possible link between mRNA and microfilaments. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:3487–3496. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.20.3487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cavellan E, Asp P, Percipalle P, Östlund Farrants AK. The chromatin remodelling complex WSTF–SNF2h interacts with several nuclear proteins in transcription. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16264–16271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600233200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kyselá K, Philimonenko AA, Philimonenko VV, Janácek J, Kahle M, Hozák P. Nuclear distribution of actin and myosin I depends on transcriptional activity of the cell. Histochem Cell Biol. 2005;124:347–358. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fuller-Pace FV. DExD/H box RNA helicases: multifunctional proteins with important roles in transcriptional regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:4206–4215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yang H, Zhou J, Ochs RL, Henning D, Jin R, Valdez BC. Down-regulation of RNA helicase II/GU results in the depletion of 18S and 28S rRNAs in Xenopus oocyte. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38847–38859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302258200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Henning D, So RB, Jin R, Lau LF, Valdez BC. Silencing of RNA helicase II/Gualpha inhibits mammalian ribosomal RNA production. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52307–52314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310846200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cisterna B, Necchi D, Prosperi E, Biggiogera M. Small ribosomal subunits associate with nuclear myosin and actin in transit to the nuclear pores. FASEB J. 2006;20:1901–1903. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5278fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Holaska JM, Wilson KL. An emerin “proteome”: purification of distinct emerin-containing complexes from HeLa cells suggests molecular basis for diverse roles including gene regulation, mRNA splicing, signaling, mechanosensing, and nuclear architecture. Biochemistry. 2007;46:8897–8908. doi: 10.1021/bi602636m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Berrios M, Fisher PA. A myosin heavy chain-like polypeptide is associated with the nuclear envelope in higher eukaryotic cells. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:711–724. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.3.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Berrios M, Fisher PA, Matz EC. Localization of a myosin heavy chain-like polypeptide to Drosophila nuclear pore complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:219–223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.1.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Galy V, Gadal O, Fromont-Racine M, Romano A, Jacquier A, Nehrbass U. Nuclear retention of unspliced mRNAs in yeast is mediated by perinuclear Mlp1. Cell. 2004;116:63–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vinciguerra P, Iglesias N, Camblong J, Zenklusen D, Stutz F. Perinuclear Mlp proteins downregulate gene expression in response to a defect in mRNA export. EMBO J. 2005;24:813–823. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tekotte H, Davis I. Intracellular mRNA localization: motors move messages. Trends Genet. 2002;18:636–642. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02819-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang S, Buder K, Burkhardt C, Schlott B, Görlach M, Grosse F. Nuclear DNA helicase II/RNA helicase A binds to filamentous actin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:843–853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109393200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhang S, Köhler C, Hemmerich P, Grosse F. Nuclear DNA helicase II (RNA helicase A) binds to an F-actin containing shell that surrounds the nucleolus. Exp Cell Res. 2004;293:248–258. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kiseleva E, Drummond SP, Goldberg MW, Rutherford SA, Allen TD, Wilson KL. Actin- and protein-4.1-containing filaments link nuclear pore complexes to subnuclear organelles in Xenopus oocyte nuclei. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2481–2490. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Singh OP, Björkroth B, Masich S, Wieslander L, Daneholt B. The intranuclear movement of Balbiani ring premessenger ribonucleoprotein particles. Exp Cell Res. 1999;251:135–146. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shav-Tal Y, Darzacq X, Shenoy SM, Fusco D, Janicki SM, Spector DL, Singer RH. Dynamics of single mRNPs in nuclei of living cells. Science. 2004;304:1797–1800. doi: 10.1126/science.1099754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Politz JC, Tuft RA, Pederson T. Diffusion-based transport of nascent ribosomes in the nucleus. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:4805–4812. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-06-0395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]