Abstract

Therapy approaches based on lowering levels of pathogenic autoantibodies represent rational, effective, and safe treatment modalities of autoimmune diseases. The neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) is a major factor regulating the serum levels of IgG antibodies. While FcRn-mediated half-life extension is beneficial for IgG antibody responses against pathogens, it also prolongs the serum half-life of IgG autoantibodies and thus promotes tissue damage in autoimmune diseases. In the present review article, we examine current evidence on the relevance of FcRn in maintaining high autoantibody levels and discuss FcRn-targeted therapeutic approaches. Further investigation of the FcRn-IgG interaction will not only provide mechanistic insights into the receptor function, but should also greatly facilitate the design of therapeutics combining optimal pharmacokinetic properties with the appropriate antibody effector functions in autoimmune diseases.

Keywords: Autoimmunity, Autoantibody, Engineered IgG, IgG homeostasis, Immunoapheresis, Therapeutic IgG

Introduction

Although autoimmunity can occur in healthy people, autoaggressive events may lead to pathology characteristic of numerous diseases [1]. The group of autoimmune diseases consists of numerous chronic disabling disorders, which may involve almost every system in the body. The sites that may be targeted by autoimmunity include the nervous system, gastrointestinal, endocrine, skin, skeletal, and vascular tissues. Collectively, autoimmune diseases affect currently 5–8% of the general population, but their prevalence is likely to be underestimated. Falling infection rates in the developed world are being matched by a rapidly rising incidence of allergic and autoimmune inflammatory diseases [2]. However, the cause(s) of autoimmunity, its regulation, and the transition to autoimmune diseases are complex, not yet fully understood, and in many cases there is no effective therapy.

While autoimmune diseases are characterized by the presence of both cellular and humoral immune responses, autoantibodies are primarily responsible for tissue damage in a subgroup of these conditions [3, 4]. Thus, the T cell-dependent production of pathogenic autoantibodies underpins the pathology in various diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, myasthenia gravis, acquired neuromyotonia, pemphigus, pemphigoids, antiphospholipid syndrome, Graves’ disease, autoimmune anemia, idiopathic trombocytic purpura, and Goodpasture’s syndrome [5–10]. The pathogenicity of autoantibodies in these conditions has been mainly demonstrated by the passive transfer of IgG specific for the autoantigens from patients or immunized animals.

The development of experimental disease models by the passive transfer of autoantibodies not only allowed for classifying them as autoimmune disorders, but also provided the rationale for therapeutic approaches aimed at reducing the levels of pathogenic autoantibodies. Currently, the mainstay of the therapy in these autoimmune diseases is still represented by corticosteroids associated with other immunosuppressive agents, which are encumbered by the need to balance efficacy with unwanted side-effects. There is a considerable need for the identification of selective therapeutic agents that target critical events in disease progression. Therefore, decreasing the autoantibody levels by removing them from the circulation or by targeting B cells are rationale therapeutic approaches, which are increasingly used in the management of autoimmune diseases. The extracorporeal immunoadsorption is very effective in removing IgG (auto)antibodies from the circulation and gradually gains acceptance as a treatment in the acute phase of the disease [11]. However, an obstacle to a wider use of immunoadsorption is its high cost and the fact that this procedure is laborious and time intensive. Reducing autoantibody levels by accelerating the endogenous catabolism of IgG (auto)antibodies by modulating the function of the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) is a promising alternative to the immunoapheresis. In addition, further therapeutic approaches involving FcRn, including engineering therapeutic antibodies with longer half-life or antigen-targeting to antigen-presenting cells for induction of tolerogenic responses, may be of benefit in patients with IgG-mediated autoimmune diseases.

Below we review the existing data on the role of the neonatal Fc receptor in maintaining autoantibody levels and discuss FcRn-targeted therapeutic approaches.

IgG antibodies

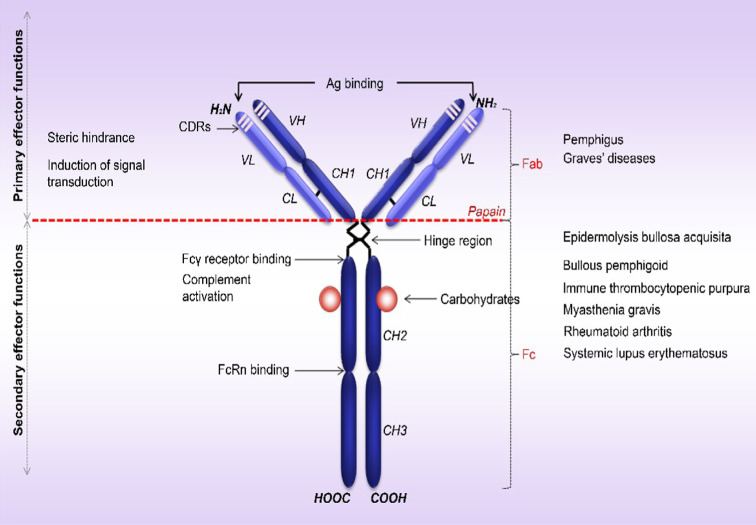

Antibodies are essential components of adaptive immunity that couple specific antigen recognition to different effector mechanisms of the immune system. B cells and plasma blasts express five classes of immunoglobulins: IgA, IgD, IgE, IgG and IgM [12]. IgG molecules are composed of four polypeptide chains, two identical copies of each a light chain (L) and heavy chain (H) that are covalently linked by disulfide bonds. A single N-linked carbohydrate is attached to the IgG heavy chains in position 297, strongly influencing IgG function [13]. Hypervariable complementarity determining regions (CDRs) that define the specificity of the antibody lie in the amino-terminal domains of L and H (Fig. 1) [14]. IgG can be cleaved into three functionally fragments by limited digestion with papain, which cuts on the amino-terminal side of disulfide bonds located in the hinge region [15]. While the two released Fab (fragment, antigen-binding) fragments retain the antigen-recognition activity, the Fc (fragment, crystallizable) region mediates specific functions, such as binding complement and specialized receptors on immune cells (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Structure of human IgG and mechanisms of autoantibody-induced tissue damage. Human IgG molecule contains two identical (H) heavy chains (50 kDa) covalently linked to two (L) light chains (23 kDa) by disulfide bonds. Each chain is organized in constant (C) and variable (V) structural domains. The heavy chain has three constant domains (CH1, CH2, CH3) and one variable domain (VH), while the associated light chain has one constant (CL) and one variable domain (VL). The variable domains of the heavy chain (VH) and the light chain (VL) have three complementarity determining regions (CDRs; CDR1, CDR2 and CDR3) with major contribution to the antigen binding site. Papain cleaves the IgG molecule above the hinge region, giving rise to two Fab fragments (fragment, antigen-binding) involved in antigen recognition and one Fc fragment (fragment, crystallizable), which binds to the C1q, FcγRs and FcRn and mediates the activation of complement and/or immune cells and IgG trafficking at various sites, respectively

IgG is the most prevalent Ig isotype in the serum and extravascular space, showing the longest circulating serum half-life [12]. As discussed in more detail below, the protective function that ensures the long presence of IgG in the circulation, by rescuing it from lysosomal degradation, has been attributed to the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn).

IgG-mediated autoimmune diseases

B cells are characterized by a high degree of antigen receptor diversification that is necessary for immune protection. However, the downside of producing enormous random diversity in the antibody repertoire is the generation of autoantibodies, which are associated with numerous diseases, but may also be detected in healthy persons [16, 17]. High-affinity IgG autoantibodies are likely to be the inducers of tissue damage in several of these diseases (Table 1). The development of experimental disease models in animals furthered our understanding of disease pathogenesis and ultimately allowed their classification as antibody-mediated autoimmune diseases (Table 2).

Table 1.

Human autoimmune diseases likely mediated by IgG antibodies

| Disease | Autoantigen(s) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Diseases associated with autoantibodies against tissue-specific antigens | ||

| Myasthenia gravis | Acethylcholine receptor, muscle-specific tyrosine kinase | [109, 110] |

| Guillain–Barré syndrome | Gangliosides | [111] |

| Epilepsy | Voltage-gated potassium channels | [112] |

| Autoimmune limbic encephalitis | Voltage-gated potassium channels | [113] |

| Spinal cord injury | Central nervous system (CNS) or non CNS antigens | [114] |

| Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infection (PANDAS) | Central nervous system (CNS) proteins (basal-ganglia antigens) | [115] |

| Neuromyotonia (Isaac’s syndrome) | Voltage-gated potassium channels | [116] |

| Morvan syndrome | Voltage-gated potassium channels | [117] |

| Multiple sclerosis | Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) | [118] |

| Pemphigus vulgaris | Desmosomal cadherins (e.g., desmoglein 3) | [119] |

| Pemphigus foliaceus | Desmoglein 1 | [120] |

| Bullous pemphigoid | Collagen XVII/BP180, BP230 | [121, 122] |

| Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita | Collagen VII | [123] |

| Pemphigoid gestationis | Collagen XVII/BP180, BP230 | [124, 125] |

| Mucous membrane pemphigoid | Type XVII collagen/BP180, laminin 332, α6β4 integrin | [126–128] |

| Lichen sclerosus | Extracellular matrix protein (ECM) 1 | [129] |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome | Cardiolipin and β2 glycoprotein I | [130] |

| Relapsing polychondritis | Type II collagen, Type IX and XI collagen, matrilin 1 and 3 | [131, 132] |

| Autoimmune anemia | Red blood cells (Band 3, Band 4.1, glycophorin A) | [133, 134] |

| Idiopathic trombocytic purpura | Platelets membrane glycoproteins IIB-IIIa, Ib-IX | [135] |

| Autoimmune Grave’s disease | Thyroid stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR) | [136] |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | β1-adrenoreceptor (β1R), Troponin I (TnI), Muscarinic receptor (M2), Myosin, Na-K-ATPase | [137] |

| Vasculitis | Myeloperoxidase, proteinase 3 | [138, 139] |

| Goodpasture’s syndrome | Collagen IV | [140] |

| Idiopathic membranous nephropathy | M-type phospholipase A2 receptor | [141] |

| Diseases associated with autoantibodies against ubiquitous antigens | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Fc of IgGs, citrullinated proteins, collagen II, IX, XI, Heat shock proteins (HSP)-65,70, 90, immunoglobulin binding protein (BiP) | [142, 143] |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Chromatin, U1 and Sm small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP) particles and the Ro/SSA and La/SSB RNP complexes and cell membrane phospholipid components | [144] |

Table 2.

Experimental IgG antibody-mediated diseases

| Autoantigen/autoantibodies | Modeled disease | Model system | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diseases induced by the passive transfer of antibodies | |||

| Acethylcholine receptor | Myasthenia gravis | Mice injected with patient IgG | [145] |

| Patients’ autoantibodies | Pemphigus vulgaris | Mice injected with patient IgG | [146] |

| Patients’ autoantibodies | Pemphigus foliaceus | Mice injected with patient IgG | [147] |

| BP180/Type XVII collagen | Pemphigoid diseases | Mice injected with IgG specific to BP180/ collagen XVII | [148] |

| Type VII collagen | Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita | Mice injected with IgG specific to collagen VII | [149] |

| Type II collagen | Rheumatoid arthritis | Mice injected with IgG specific to collagen II (CAIA) | [150] |

| Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI) | Rheumatoid arthritis | Passive transfer of IgG from K/BxN transgenic mice to wild type mice | [151] |

| Cardiolipin and β2 glycoprotein I | Anti-phospholipid syndrome | Mice injected with monoclonal/ polyclonal aPL Abs from mouse/human | [152] |

| Anti-DNA idiotype | Systemic lupus erythematosus | Balb/c mice injected with monoclonal antibodies expressing 16/6 Id | [153] |

| Red blood cells | Autoimmune anemia | Mice injected with anti-red blood cells (RBC) monoclonal antibodies | [154] |

| Glycoproteins IIB-IIIa, Ib-IX | Idiopathic trombocytic purpura | Mice injected with monoclonal antibodies against glycoprotein GPIIb-IIIa, GPIb-IX | [155] |

| β1 adrenoreceptor | Dilated cardiomyopathy | Passive transfer of anti-β1-ECII antibodies into rats | [156] |

| Muscarinic receptor | Dilated cardiomyopathy | Mice injected with IgG against β1-adreno- and muscarinic receptor antibodies | [157] |

| Myeloperoxidase (MPO) | Vasculitis | Mice injected with IgG against mieloperoxidase or bone marrow cells | [158] |

| Collagen IV | Goodpasture’s syndrome | Passive transfer of rabbit anti-glomerular basement membrane | [159] |

| Extracellular matrix protein (ECM) 1 | Lichen sclerosus | Mice injected with purified hIgG from patients with Lichen sclerosus | [160] |

| Central nervous system proteins (basal ganglia antigens) | Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infection (PANDAS) | Passive transfer of IgG from mice immunized with N-acetyl-β-D-glucosamine-immunodominant epitope of GABSH (Group A β-hemolytic streptococcos) into naïve mice | [161] |

| Antibasement membrane | Mucous membrane pemphigoid | Rabbits injected with a monoclonal antibody (MAb 63) against basement of stratified squamous epithelium | [162] |

| Potassium channels | Acquired neuromyotonia (Isaac’s syndrome) | Passive transfer of human IgG into mice | [163] |

| Central nervous system (CNS) or non- CNS antigens | Spinal cord injury (SCI) | Mice injected with purified mouse SCI IgG | [164] |

| Morvan syndrome | Passive transfer of human IgG into mice | [163] | |

| Epilepsy | Passive transfer of human IgG into mice | [163] | |

| Diseases induced by immunization with the autoantigen | |||

| Acethylcholine receptor | Myasthenia gravis | Rabbits immunized with the autoantigen | [165] |

| Muscle-specific tyrosine kinase | Myasthenia gravis | Mice immunized with the autoantigen | [166] |

| Collagen VII | Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita | Mice immunized with the autoantigen | [167] |

| Collagen II | Rheumatoid arthritis | Mice immunized with the autoantigen (CIA) | [168] |

| Cardiolipin and β2 glycoprotein I | Anti-phospholipid syndrome | Adoptive transfer of autoimmunity (bone marrow transplantation) | [169] |

| Desmoglein 3 | Pemphigus vulgaris | Adoptive transfer of splenocytes from the immunized Dsg3 –/– mice into Rag-2 –/– immunodeficient mice expressing Dsg3 | [170] |

| Cardiolipin and β2 glycoprotein I | Anti-phospholipid syndrome | Mice immunized with anti-phospholipid antibodies | [171] |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Balb/c mice immunized with activated lymphocyte-derived DNA (ALD-DNA) | [172] | |

| Red blood cells | Autoimmune anemia | Mice immunized with rat erythrocytes | [173] |

| Thyroid stimulating hormone receptor | Autoimmune Grave’s disease | Mice immunized with fibroblasts transfected with the thyrotropin receptor and MHC-class II molecule | [174] |

| β1-adrenoreceptor | Dilated cardiomyopathy | Rats immunized against β1-ECII | [175] |

| Troponin I | Dilated cardiomyopathy | Mice immunized with monoclonal antibodies to cardiac troponin I | [176] |

| Muscarinic receptor | Dilated cardiomyopathy | Rabbits immunized with β1 adrenoreceptor and M2-muscarinic receptor peptides | [177] |

| Myosin | Dilated cardiomyopathy | Mice immunized with murine cardiac myosin | [178] |

| Na-K-ATP-ase | Dilated cardiomyopathy | Rabbits immunized with Na-K-ATPase | [179] |

| Proteinase (PR) 3 | Vasculitis | Mice immunized with human proteinase 3(105-201) or synthetic antisense PR-3 | [180] |

| GM1ganglioside | Guillain–Barré syndrome | Rabbits immunized with bovine brain ganglioside mixture or purified GM1 | [181] |

| Collagen IV | Goodpasture’s syndrome | Rabbits or mice immunized with α3(IV) NC1 | [182] |

| Matrilin I | Relapsing polychondritis | Rats/mice immunized against matrilin I | [183] |

| Collagen II | Relapsing polychondritis | Rats immunized against type II collagen | [184] |

| Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein | Multiple sclerosis | Mice immunized with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein; passive transfer of autoreactive B cells and autoantibodies in B cell-deficient mice | [185] |

| Spontaneous and genetically engineered animal models | |||

| Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI) | Rheumatoid arthritis | K/BxN spontaneous mouse model | [186] |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) |

MRL/lpr, BXBS (NZBxNZW) F1 mice which spontaneously develop SLE Bcl2t, IFN-γ transgenic mice |

[187–191] | |

| Red blood cells | Autoimmune anemia | Transgenic mice carrying the Ig genes encoding an anti-murine erythrocyte autoantibody derived from the hybridoma 4C8 | [192] |

| Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) | Multiple sclerosis | TCR transgenic mice carrying a TCR specific for MOG peptide 92-106 | [193] |

| Collagen II | Relapsing polychondritis | HLA-DQ6/8 transgenic mice immunized against type II collagen | [194] |

CIA collagen-induced arthritis, CAIA collagen antibody-induced arthritis

Although the mechanisms triggered by binding of autoantibodies to their targets are multiple, several common patterns emerge (Fig. 1). In organ-specific autoimmune diseases, autoantibodies generally induce direct injury of the target organs. In systemic autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, they can also bind to different ubiquitous intracellular antigens and cause disease through the formation of immune complexes. The effector mechanisms of antibodies may be divided into direct mechanisms (primary effector functions), which are mediated by the antibody’s variable regions, including steric hindrance and signal transduction, and indirect mechanisms (secondary effector functions) which are triggered by the constant regions of antibodies. For the latter, (auto)antibodies typically interact through their Fc portions with factors of the innate immune system, including the complement system and FcγR on inflammatory cells. Steric hindrance or activating signaling transduction pathways by the IgG variable fragments are characteristic for pemphigus diseases, while typically effector interactions mediated by the Fc portion of the IgG such as activation of complement cascade or Fc receptors expressed on immune cells, are associated with rheumatoid arthritis, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, bullous pemphigoid, and myasthenia gravis. The pathogenic potential of IgG autoantibodies—regardless of antibody specificity or pathogenetic mechanisms—is in direct relation to their concentration, which is regulated by FcRn.

The neonatal Fc receptor

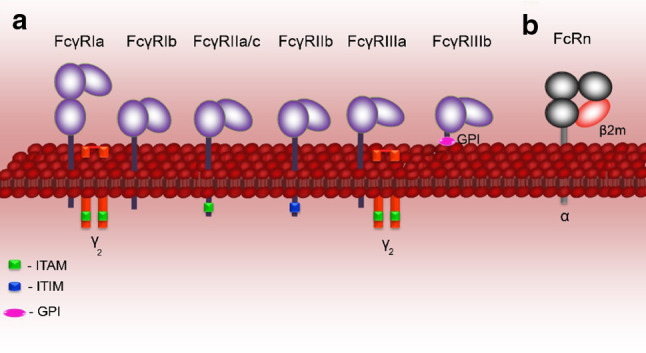

Receptors for the Fc domain of IgG link the humoral immune response to effector cellular mechanisms instrumental in immunity and autoimmune tissue damage. By cross-linking the Fcγ receptors, IgG may activate a variety of biological responses, including phagocytosis, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, and release of cytokines. These reactions are mediated by several types of activating Fcγ receptors expressed on leucocytes, which in humans include FcγRI, FcγRIIa, FcγRIIc, and FcγRIII (Fig. 2a) [18]. These cellular responses may be in turn downregulated by the inhibitory FcγRIIb [19]. In the last decades, various polymorphisms in the FcγR family of proteins have been revealed, ranging from single nucleotide- to gene copy number polymorphisms. These polymorphisms, reviewed elsewhere, have been implicated in various infections and autoimmune diseases in opposing ways [20]. In contrast to these Fc receptors primarily expressed on immune cells, FcRn also showing a strong affinity for the Fc portion of IgG is widely expressed in endothelial, epithelial, and hematopoietic cells [21–23].

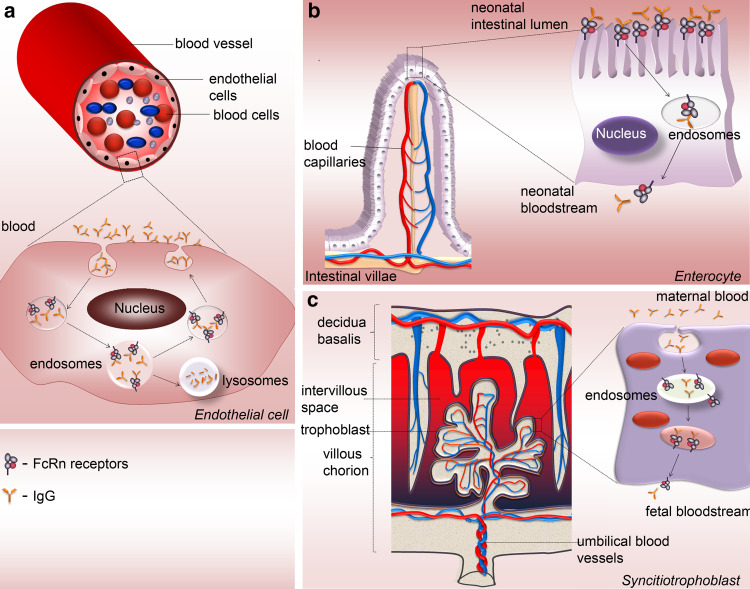

Fig. 2.

Human Fc receptors for IgG. The Fc region of IgG binds several types of Fc receptors, including activatory and inhibitory Fcγ receptors and the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn). a Human Fcγ receptors, termed FcγRI (CD64), FcγRII (CD32), FcγRIII (CD16) are cell-surface molecules primarily expressed on immune cells. Structurally, these receptors share a highly homologous extracellular region composed of immunoglobulin-like domains, but they show major differences in the organization of the transmembrane and cytoplasmic regions, hence their different effector functions. With the exception of FcγRIIb, which is associated with the cytoplasmic immune receptor thyrosine-based inhibtion motif (ITIM), FcγRI, and FcγRIIIa associate with the Fc-Receptor γ-chain (FcRγ-chain) that possess a cytoplasmic immune receptor thyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM), whereas FcγRIIa and FcγRIIc contain their own cytoplasmic ITAM. The ITAM- and the ITIM-containing FcγR elicit different and at times opposing types of intracellular signaling mechanisms. b The neonatal Fc receptor for IgG, is structurally similar to the MHC-class I molecules, rather then the Fcγ family, consisting of a transmembrane glycosylated alpha chain non-covalently coupled to β2-microglobulin. Unlike classical Fcγ receptors, FcRn binds IgG at low pH, mediating the transfer of these antibodies from mother to young, and preserving it in the circulation during the adult life. FcRn is expressed in endothelial, epithelial, and hematopoietic cells. In myeloid cells, in addition to contributing to IgG homeostasis, FcRn modulates IgG-mediated phagocytosis and antigen presentation

FcRn was initially identified and purified from the brush borders of rat intestinal epithelial cells [24, 25]. Cloning of the FcRn several years later revealed its homology to the MHC class I family of proteins, consisting of an α heavy chain of approximately 50 kDa non-covalently associated with β2 microglobulin [26, 27]. The α chain has a large ectodomain comprising three subdomains, a transmembrane region, and a short cytoplasmic tail that encodes for a highly conserved signaling motif important for intracellular trafficking of FcRn (Fig. 2b) [21, 26, 28, 29]. The gene encoding FcRn is located outside the MHC gene complex and, unlike the classical MHC class I proteins, the MHC peptide-binding groove is obstructed in FcRn [26, 30, 31]. Subsequent studies documented the expression of FcRn in several other species, including human and mouse [30, 32–38].

The interaction site for IgG on FcRn has been characterized by crystallization of the rat FcRn-rat IgG2a complex [31, 39]. The residues important for the IgG binding to FcRn are highly conserved in mammals and are located within the CH2–CH3 interface in the constant region (Fc) of IgG antibodies (Fig. 1) [31, 40–43]. Mammalian FcRn is specific for IgG and does not bind IgA, IgM, IgE, or avian IgY. FcRn binds to Fc with nanomolar affinity at pH <6.5 but does not bind IgG measurably at physiological pH.

FcRn plays a major role in IgG homeostasis by mediating a salvage pathway (Fig. 3a) that prevents lysosomal degradation of IgG, thus contributing to a long half-life in the circulation, compared to other serum proteins. Other major specific functions of FcRn include the passive delivery of IgG from mother to young via the neonatal intestine, in rodents (Fig. 3b), across the maternal–fetal barrier in humans (Fig. 3c), and modulation of IgG traffic across absorptive epithelia from mammary gland, liver, lung, kidney, and adult intestine.

Fig. 3.

FcRn functions. a In adult life, FcRn is responsible for the regulation of IgG persistence in the circulation. IgGs are internalized by endothelial cells by fluid phase pinocytosis. At the low pH of the acidic endosomes FcRn binds IgG, transports it back to the cell surface where, due to the neutral pH, complex stability decreases and IgG is released/recycled. Unbound IgG is catabolized in the lysosomes. FcRn also controls the transfer of antibodies from b mother’s milk to neonates in the gut and from c maternal plasma through the placenta to fetus in most mammals. IgG-FcRn interaction is pH dependent, occurring efficiently at an acidic pH 6 (as found in intestinal lumen or endosomes). Binding of FcRn to IgG becomes progressively weaker as the pH raises to near neutral, until at around pH 7.4 it is negligible. Receptor-bound IgGs are then transcytosed across the epithelial intestinal cells (b) or syncitiotrophoblasts (c) being released from this complex in the neonatal or fetus tissues/bloodstream upon exposure to the neutral pH-7.4 of these millieu

FcRn serves to deliver IgGs bidirectionally across polarized epithelial barriers throughout life. The FcRn-dependent mechanisms of trafficking of IgGs and IgG-antigen complexes across epithelial cells have been dissected in cell lines and in adult animals, including mice and non-human primates [44–52]. These studies provided a basis for the design of novel approaches to deliver therapeutic proteins in form of IgG or Fc-fused therapeutic complexes in an FcRn-dependent mode across the lung epithelium of adult mice and nonhuman primates [44, 51, 53, 54]. With regard to the transport of IgG across intestinal epithelia, it is noteworthy that the pattern of FcRn expression in the gut differs between human and rodents. While the expression of rodent FcRn peaks on the intestinal epithelial cells during the neonatal period and declines rapidly after weaning, in humans, FcRn is expressed by intestinal epithelial cells in both the fetus and adult. To circumvent this problem, Blumberg and colleagues used mice that expressed human FcRn in the intestinal epithelial cells to address the previously underestimated role of IgG and FcRn in mucosal immunity [50, 55]. These functions of FcRn have been addressed in recent extensive review articles and will not be discussed here [21, 22, 56, 57]. The expression of FcRn in highly specialized cell types, including antigen-presenting cells, phagocytes, and podocytes suggested further possible functions of this receptor [58–62]. Indeed FcRn appears to be involved in both IgG-dependent phagocytosis and antigen presentation by directing immune complexes into lysosomes [23, 60, 63]. Since functional FcRn is needed to remove IgG from the glomerular basement membrane, its contribution to the pathology of IgG-mediated glomerulonephritis should be further explored [59].

FcRn is essential for maintaining IgG serum levels

Although the existence of a specialized receptor was postulated by Brambell in the 1960s to explain the long half-life of IgG and its transfer from mother to young, it took several decades to obtain direct evidence for its function [64–66]. Experimental support for this hypothesis came initially from the observation that β2 microglobulin-deficient mice show significantly lower serum half-life and serum levels of IgG [65–67]. Subsequent studies using mice with targeted deletion of the FcRn gene confirmed and extended these findings and provided direct evidence that perinatal IgG transport and protection of IgG from catabolism are indeed mediated by FcRn [68]. These functions are relevant for IgG homeostasis, essential for generating a potent IgG response to foreign antigens, and the basis of enhanced efficacy of Fc-IgG-based therapeutics. These studies established FcRn as a promising therapeutic target for enhancing protective humoral immunity, treating autoimmune diseases, and improving drug efficacy.

FcRn maintains autoantibody levels and thus promotes autoimmune diseases

The identification of the FcRn as central regulator of IgG serum levels ignited sustained interest in its involvement in controlling the levels of autoantibodies. Thus, in several independent studies, an effect of FcRn deficiency/blockade has been documented over the last years in experimental models of various autoimmune diseases, including pemphigus, bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, myasthenia gravis, idiopathic trombocytic purpura, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus [69–76].

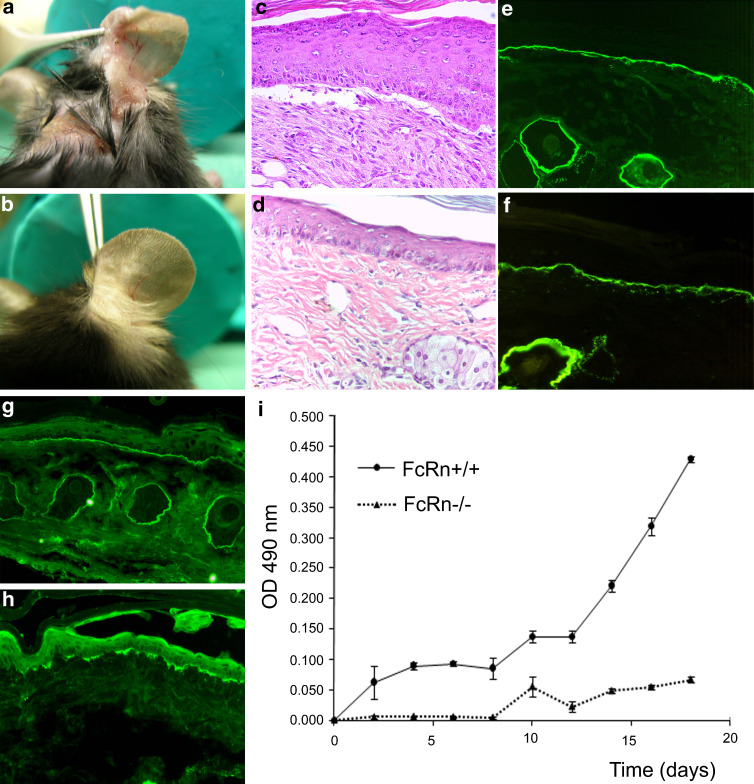

Initial studies showed that β2 microglobulin-deficient mice, which also lack FcRn, are protected from induction of blistering by the passive transfer of antibodies against BP180/type XVII collagen [69]. These effects were assigned to significantly lower levels of pathogenic antibodies in the knock-out mice, which was presumably due to accelerated catabolism of IgG in the animals [69]. The generation of FcRn heavy chain-deficient mice allowed this question to be more directly addressed in experimental models of rheumatoid arthritis, pemphigus, pemphigoids, and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita [71, 72, 74]. As hypothesized, a common finding of these studies was that circulating levels of pathogenic IgG in FcRn-deficient mice were significantly reduced compared to those in wild-type mice. Thus, FcRn deficiency conferred either partial or complete protection in the arthritogenic serum transfer and the more aggressive genetically determined K/BxN autoimmune arthritis models as well as in the passive transfer mouse models of pemphigus, pemphigoid, and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (Fig. 4) [71, 72, 74]. The protective effects of the FcRn deficiency could be overridden by administering higher amounts of pathogenic IgG antibodies [71, 72]. These findings suggested that FcRn allows, by prolonging the life span of IgG, pathogenic IgG autoantibody concentration to achieve a threshold that enables triggering a cascade of downstream inflammatory mechanisms, including complement activation and leukocyte recruitment, and activation [71, 72]. The benefits conferred by functional FcRn deficiency may be overcome if the autoantibody concentration exceeds a critical level. Although not formally shown yet, it is likely that this mechanism also applies for other IgG-mediated diseases, including pemphigus or myasthenia gravis.

Fig. 4.

FcRn-deficiency protects from tissue injury in experimental epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Mice were injected every second day with 5 mg of pathogenic rabbit antibodies against murine type VII collagen (mCVII) [72]. Characteristic blisters, erosions, and crusts were detected 18 days after the first injection in a wild-type animals, while no cutaneous lesions were observed in b FcRn-/- mice. Histological and immunopathological examination of skin biopsies obtained from wild-type mice showed c subepidermal blisters and accumulation of neutrophils as wells as deposition of e IgG and g C3 at the dermal-epidermal junction. d No histological changes were detected in an FcRn-/- mouse injected with rabbit anti-collagen VII IgG. Immunofluorescence analysis of skin biopsies of the FcRn-/- mice revealed positive staining for f rabbit IgG and discrete focal deposition of h murine C3 at the dermal–epidermal junction (magnification ×200). i Serum samples obtained from experimental animals were analyzed by ELISA to measure the levels of antibodies to type VII collagen. Compared to wild-type mice, FcRn-/- mice showed significantly lower levels of circulating pathogenic IgG

In addition to inhibiting FcRn by the targeted gene disruption, the pharmacological blockade of the receptor yielded a similar phenotype in mouse models of induced myasthenia gravis and rheumatoid arthritis [73, 76]. In one of these studies, the 1G3 mouse monoclonal antibody, specific for the heavy chain of FcRn, was used to block the receptor’s function in models of experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis in rats [73, 77]. Experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis was induced in rats by the passive transfer of an anti-acetylcholine receptor monoclonal antibody or by immunization with the acetylcholine receptor. Treatment of these animals with 1G3 resulted in dose-dependent reduction of the pathogenic IgG levels and in amelioration of the disease symptoms [73]. These results directly showed that pharmacological FcRn blockade is a feasible approach for an effective reduction of IgG autoantibody levels.

Collectively, current evidence suggests that disease does not occur when FcRn inhibition is able to restrain pathogenic antibodies below a particular threshold. When this threshold is exceeded, however, pathogenic IgG precipitate a cascade of events that eventually results in tissue damage. These studies established FcRn, which links the initiation of the humoral autoimmune response and the autoantibody-mediate tissue damage, as a promising therapeutic target in IgG-mediated autoimmune diseases [71–74].

Current therapeutic approaches involving FcRn

Although no approach specifically targeting FcRn is currently approved for the treatment of IgG-mediated autoimmune diseases, existing therapies may exert their effects partly by modulating the FcRn function as discussed below.

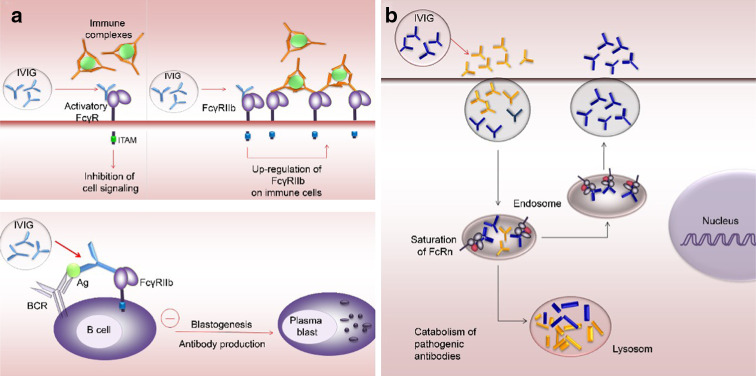

High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin therapy (IVIG) is an established and effective (albeit expensive) treatment of numerous inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, including antibody-mediated autoimmune diseases (Table 3). The mechanisms underlying its therapeutic benefit are intensely debated and have been attributed to various factors, including activation of the inhibitory Fc gamma receptor (Fig. 5a) and FcRn inhibition (Fig. 5b). Mechanisms of IVIG action (Table 4), which are surely complex and are probably dependent on the main pathogenic events of the specific disease, have been discussed in extenso in recent review articles [78, 79]. Nevertheless, results from several laboratories support the view that saturation of FcRn leading to an increased catabolism of endogenous IgG is the main mechanism underlying IVIG effects in IgG-mediated autoimmune diseases [69–76, 80–83].

Table 3.

Diseases with established efficacy of IVIG treatment

| Disease | Reference |

|---|---|

| Pemphigus vulgaris | [195] |

| Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura | [196] |

| Guillain–Barré syndrome | [197] |

| Myasthenia gravis | [198] |

| Multifocal motor neuropathy | [199] |

| Kawasaki’s disease | [200] |

| Prevention of graft-versus-host disease | [201] |

| Chronic idiopathic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy | [202] |

Fig. 5.

Major Fc-dependent mechanisms of action for IVIG in IgG-mediated autoimmune diseases. a Blocking of activating FcγRs and up-regulation of inhibitory FcγRs. In IgG-mediated inflammatory diseases, activation of FcγR expressed on immune cells may essentially contribute to tissue destruction. Antibodies found in IVIG compete with antigen-IgG complexes for binding the activating FcγRs, thus limiting or inhibiting their ability to trigger cell signaling events. In addition, IVIG interaction with the FcγRIIb increases its expression on immune effector cells, therefore, triggering the activating FcγR requires higher concentration of immune complexes. This “inhibition” appears to be mainly responsible for the anti-inflammatory activity proposed of IVIG. Upon co-ligation of the B-cell antigen receptor (BCR) with the FcγRIIb, IVIG activates an inhibitory signaling pathway on B lymphocytes, impairing blastogenesis and IgG synthesis. b Saturation of FcRn. IgG in IVIG formulations binds to and saturates the FcRn leading to accelerated the catabolism of pathogenic antibodies and thereby lowering their levels in the circulation below the threshold required for disease progression

Table 4.

Main immunoregulatory effects of intravenous immune globulin (IVIG)

| Blockade of activatory Fcγ receptors on immune cells |

| Up-regulation of inhibitory FcγRIIb |

| Induction of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity |

| Saturation of FcRn |

| Neutralization of autoantibodies by anti-idiotypic activity |

| Inhibition of blastogenesis and IgG production |

| Modulation of cytokines production |

| Neutralization of superantigens (Sag) |

| Inhibition of lymphocyte proliferation |

| Regulation of Fas-induced apoptosis |

| Prevention of complement-mediated immune damage |

| Inhibition of activation of endothelial cells |

The systemic administration of corticosteroids still represents the mainstay of the therapy in most autoimmune diseases. Although corticosteroids were shown to reduce the levels of serum autoantibodies in patients and different experimental settings, an FcRn-dependent mechanism has not yet been formally demonstrated. However, a previous study showed that exogenous corticosteroids and L-thyroxine hormone inhibit Ig transport and steady-state duodenal Fc receptor mRNA levels in suckling rats [84]. Further work demonstrated that dexamethasone exposure for 72 h decreases the steady-state level of mRNA for the FcRn alpha-subunit in rat alveolar epithelial cell monolayers [85]. Therefore, in addition to their pleiotropic effects on immune or antibody target cells, corticosteroids may influence the levels of autoantibodies by regulating the expression of the FcRn receptor in different cell types. In addition to a direct effect on the FcRn expression, corticosteroid treatment and other anti-inflammatory medications may also influence its expression and/or activity through modulation of cytokines.

Development of new FcRn-targeted therapies

Detailed knowledge on the biochemistry of FcRn and on its interaction with IgG as well as the generation of FcRn knock-out and human FcRn transgenic mice significantly accelerated the development of new and ingenious therapeutic approaches.

Inhibition of IgG-FcRn interaction to lower endogenous IgG levels

Since the long plasma half-life of the IgG is dependent on FcRn, blocking of the IgG-FcRn interaction is a rationale approach aimed at reducing autoantibody levels in autoimmune diseases. Although recombinant soluble human FcRn can be produced in bacteria in high amounts, the recombinant receptor reproduces the characteristic pH-dependent reversible binding to IgG at pH 6.0, with almost undetectable binding at neutral pH [86]. Experimental evidence demonstrating its transfer into intracellular acidic compartments of endosomes where IgG binding to FcRn should occur, are lacking. Inhibition of the IgG-FcRn interaction is probably best achieved by using FcRn-specific blocking monoclonal antibodies, engineered IgG with higher binding affinity to FcRn, or peptide inhibitors of the receptor. In addition, modulation of FcRn expression may be considered as an option for developing new therapeutic approaches.

Blocking FcRn-specific monoclonal antibodies

Initial hints that monoclonal antibodies specific to FcRn may be effective for the treatment of IgG-mediated autoimmune conditions have been provided by pharmacokinetic studies in rats [87].

As mentioned above, the therapeutic effects of the FcRn-specific monoclonal antibody 1G3 were recently investigated using rat models of myasthenia gravis [73]. Passive experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis was induced by administration of a monoclonal antibody specific for the acetylcholine receptor (AChR), and it was shown that treatment with 1G3 resulted in dose-dependent amelioration of the disease symptoms. In addition, the concentration of pathogenic antibody in the serum was significantly reduced. The effect of 1G3 was also studied in an active model of experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis in which rats were immunized with AChR. Treatment with 1G3 significantly reduced the severity of the disease symptoms as well as the levels of total IgG and anti-AChR IgG relative to untreated animals [73]. These results suggested that FcRn blockade is an effective way to treat IgG-mediated autoimmune diseases and stimulated further research endeavors to develop improved FcRn inhibitors.

Engineered IgG with higher binding affinity to FcRn (Abdegs)

IgG engineered by Ward and colleagues to have higher binding affinity to FcRn, also termed Abdegs (antibodies that enhance IgG degradation), were shown to modulate endogenous IgG levels in vivo [88, 89]. A further study extended these findings using human IgG1 antibodies with enhanced binding to FcRn in mice expressing human FcRn. When injected into FcRn-humanized mice at a concentration sufficient to partially saturate hFcRn, the engineered IgG1 mutants with an extended serum half-life were most effective in reducing the half-life of a tracer hIgG1 antibody. Importantly, administration of mutant with high binding to hFcRn ameliorated arthritis induced by passive transfer with human pathogenic plasma [76]. Abdegs with irrelevant specificity or their Fc fragments act as competitive inhibitors with endogenous IgG for FcRn binding, may enhance the clearance of IgG and thus could mimic the effects of the IVIG. However, both Abdegs (Fc binding) and anti-FcRn blocking monoclonal antibodies (Fab binding) have themselves short in vivo half-lives [87, 89, 90]. As a consequence, the administration of Abdegs results in a reduction of serum IgG levels that lasts for several days until it rebounds to their initial levels [88].

FcRn-binding synthetic peptides or peptidomimetics

Synthetic peptides inhibiting the binding of IgG to FcRn have been developed and their effects on the levels of endogenous IgG were studied in cynomolgus monkeys [91]. A 26-amino acid peptidomimetic dimer, identified using phage display peptide libraries, was capable of potent in vitro inhibition of the hIgG–hFcRn interaction. Administration of the peptide to mice transgenic for hFcRn induced an increase in the rate of catabolism of hIgG in a dose-dependent manner. Treatment of cynomolgus monkeys with the inhibitory peptide led to a reduction of IgG by up to 80%. Noteworthy, the administration of this peptide did not affect the levels of serum albumin, which has been also shown to bind an epitope on FcRn that is spatially separated from the IgG-binding epitope [91, 92]. This study represents a proof of concept that small molecules can be generated for the specific therapeutic inhibition of the IgG-FcRn interaction.

FcRn inhibitory peptides would have the advantage of being more specific in their action compared with monoclonal antibodies or engineered IgG, which may induce also other FcγR-dependent effects. An outstanding example is the upregulation of FcγRIIB expression by the monomeric IgG in IVIG preparations [93, 94]. However, this broader mechanism of action of engineered therapeutic IgG, including anti-inflammatory effects, may provide more benefit to patients with IgG-mediated inflammatory diseases compared with FcRn peptide inhibitors.

Down-regulation of FcRn expression

Modulation of the FcRn expression may offer additional perspectives for controlling the IgG autoantibody levels. In vitro studies provided evidence that treatment of intestinal epithelial cell lines, macrophage-like THP-1, and freshly isolated human monocytes with TNF-α and IL-1β up-regulated FcRn gene expression [95]. This effect, which may be especially relevant in the setting of inflammatory autoimmune diseases, was suggested to depend on NF-kappaB signaling [95]. Interestingly, activation of the JAK/STAT-1 signaling pathway by IFN-γ was shown to down-regulate functional expression of FcRn [96]. The regulation of FcRn expression by immunological and inflammatory events clearly needs further investigation. However, in addition to siRNA and/or antisense nucleotides, using agents modulating the activity of pro-inflammatory cytokines or of their signaling molecules/pathways may be considered for developing therapeutic approaches to regulate FcRn expression and function in autoimmune disease.

FcRn-dependent modulation of the autoimmune response

Engineered therapeutic IgG with modified binding affinity to FcRn

Therapeutic IgG antibodies targeting various inflammatory cytokines or immune cells, including antigen-presenting cells, T and B lymphocytes, gained wide acceptance in the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Engineering therapeutic antibodies or Fc-fusion proteins for enhancing their binding to FcRn may increase the half-life of these reagents. This improved feature would be of significant benefit in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases because of the resulting sustained serum concentrations, decreased dosing frequency, and/or lower costs of therapeutic antibodies [97, 98]. Indeed the use of protein engineering combined with knowledge of FcRn-IgG interactions allowed developing approaches for the modulation of the serum half-lives of therapeutic antibodies [90, 97, 99–101].

FcRn-targeted antigen delivery to antigen-presenting cells

The development of safe and effective antigen-specific therapies is of great importance for the management of patients with autoimmune diseases. These therapies must allow for the specific tolerization of self-reactive immune cells without altering host immunity to infectious insults [102]. An alternative therapeutic approach for autoimmune diseases involving FcRn has been explored by targeting antigen delivery to antigen-presenting cells using engineered Fc fragments [60, 63]. This approach takes advantage of the fact that the presentation of antigens in IgG-containing immune complexes by dendritic cells is dependent on FcRn [60, 63]. For this study, recombinant Fc fusion proteins containing the N-terminal epitope of myelin basic protein were generated with distinct binding properties for FcRn resulting in differences in intracellular trafficking and in vivo half-lives. Fc fragments with increased affinities for FcRn resulted in enhanced proliferation of CD4 T cells in vivo [60]. While not lowering the autoantibody levels by accelerating IgG catabolism, a modification of this therapeutic approach may be utilized to modulate the production of pathogenic autoantibodies in an antigen-specific specific manner.

Pre-clinical systems for FcRn-targeted therapy development

As discussed above, numerous promising FcRn-based treatment modalities currently being developed may eventually constitute valuable additions to the therapeutic armamentarium of antibody-mediated autoimmune diseases. Currently, efforts are being made for translating the plethora of therapeutic approaches developed in animals into effective treatments in patients with autoimmune diseases. Due to the similarities between human and primate FcRn, cynomolgus and rhesus monkeys were used to asses the in vivo pharmacokinetics and effects of FcRn-targeted agents [91, 103–106]. However, experimentation on primates is expensive and is also associated with ethical issues. Therefore, the development of adequate models in rodents or other small animals is of great importance. Mouse models may be not best suited to evaluate therapeutic human IgG molecules mainly due to evolutionary cross-species differences in FcRn-IgG binding. The generation of mice lacking endogenous FcRn and transgenically expressing its human ortholog represents an important step towards addressing this problem [22, 76]. Since these mice have low endogenous IgG levels due to poor binding of mouse IgG to human FcRn, this model could be further improved by crossing with mice expressing human IgGs [22, 57, 107, 108].

Conclusions and perspectives

Through sustained research of the past decades, many aspects of FcRn function have been elucidated. The experimental evidence accumulated demonstrated conclusively that FcRn plays a central role in the regulation of serum IgG levels in mammals. Further, it has become clear that by controlling the serum IgG levels, FcRn may essentially influence the humoral immune response. Although significant advances have been made in the development of several FcRn-targeted therapies, translating these treatment modalities from bench to bedside has remained difficult. Pre-clinical studies using FcRn-targeted therapies to accelerate the catabolism of IgG autoantibodies should be further improved and will hopefully soon reach the stage of clinical trials in patients. The translational process may essentially benefit from the generation of new inhibitors with improved pharmacokinetic and safety profiles as well as from tailoring the Fc region of therapeutic IgG to suit the specific therapeutic goals. It is worth considering FcRn as an additional target for immunomodulatory interventions. Such approaches aimed at re-establishing T and B cell tolerance and curbing the aberrant autoimmune response may set out to engineering Fc fragment-epitope fusions for improved targeting of antigen-presenting cells. Further investigation of the FcRn-IgG interaction will not only provide mechanistic insights into the receptor function but may also be exploited for the design of therapeutics combining optimal pharmacokinetic properties with the appropriate antibody effector functions in autoimmune diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support by the Excellence Initiative of the German Federal and State Governments and grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SI-1281/2-1, SI1281/4-1 and EXC 294 BIOSS-B13 to CS) and from the Medical Faculty of the University of Freiburg (to CS). We thank Kinga Csorba, Florina Florea, Emilia Licarete, Vasile Feldrihan, and Vlad Vuta, Freiburg, Germany, for critical reading of the manuscript and colleagues who have contributed to our studies on the FcRn involvement in IgG-mediated autoimmune diseases.

References

- 1.Sinha AA, Lopez MT, McDevitt HO. Autoimmune diseases: the failure of self tolerance. Science. 1990;248:1380–1388. doi: 10.1126/science.1972595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bach J. The effect of infections on susceptibility to autoimmune and allergic diseases. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:911–920. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drachman DB. How to recognize an antibody-mediated autoimmune disease: criteria. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1990;68:183–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rose NR, Bona C. Defining criteria for autoimmune diseases (Witebsky’s postulates revisited) Immunol Today. 1993;14:426–430. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90244-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stassi G, De Maria R. Autoimmune thyroid disease: new models of cell death in autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:195–204. doi: 10.1038/nri750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irani S, Lang B. Autoantibody-mediated disorders of the central nervous system. Autoimmunity. 2008;41:55–65. doi: 10.1080/08916930701619490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conti-Fine BM, Milani M, Kaminski HJ. Myasthenia gravis: past, present, and future. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2843–2854. doi: 10.1172/JCI29894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mihai S, Sitaru C. Immunopathology and molecular diagnosis of autoimmune bullous diseases. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11:462–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards JCW, Cambridge G. B-cell targeting in rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:394–403. doi: 10.1038/nri1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin F, Chan AC. B cell immunobiology in disease: evolving concepts from the clinic. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:467–496. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hershko AY, Naparstek Y. Removal of pathogenic autoantibodies by immunoadsorption. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1051:635–646. doi: 10.1196/annals.1361.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manz RA, Hauser A, Hiepe F, Radbruch A. Maintenance of serum antibody levels. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:367–386. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jefferis R, Lund J, Pound JD. IgG-Fc-mediated effector functions: molecular definition of interaction sites for effector ligands and the role of glycosylation. Immunol Rev. 1998;163:59–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edelman GM. Antibody structure and molecular immunology. Scand J Immunol. 1991;34:1–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1991.tb01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamaguchi Y, Kim H, Kato K, Masuda K, Shimada I, Arata Y. Proteolytic fragmentation with high specificity of mouse immunoglobulin G. Mapping of proteolytic cleavage sites in the hinge region. J Immunol Methods. 1995;181:259–267. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elkon K, Casali P. Nature and functions of autoantibodies. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jankovic M, Casellas R, Yannoutsos N, Wardemann H, Nussenzweig MC. RAGs and regulation of autoantibodies. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:485–501. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Fc gamma receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:34–47. doi: 10.1038/nri2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takai T, Ono M, Hikida M, Ohmori H, Ravetch JV. Augmented humoral and anaphylactic responses in Fc gamma RII-deficient mice. Nature. 1996;379:346–349. doi: 10.1038/379346a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Sorge NM, van der Pol W, van de Winkel JGJ. Fc gammaR polymorphisms: Implications for function, disease susceptibility and immunotherapy. Tissue Antigens. 2003;61:189–202. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2003.00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghetie V, Ward ES. Multiple roles for the major histocompatibility complex class I- related receptor FcRn. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:739–766. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roopenian DC, Akilesh S. FcRn: the neonatal Fc receptor comes of age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:715–725. doi: 10.1038/nri2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vidarsson G, Stemerding AM, Stapleton NM, Spliethoff SE, Janssen H, Rebers FE, de Haas M, van de Winkel JG. FcRn: an IgG receptor on phagocytes with a novel role in phagocytosis. Blood. 2006;108:3573–3579. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodewald R, Kraehenbuhl JP. Receptor-mediated transport of IgG. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:159s–164s. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.1.159s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simister NE, Rees AR. Isolation and characterization of an Fc receptor from neonatal rat small intestine. Eur J Immunol. 1985;15:733–738. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830150718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simister NE, Mostov KE. An Fc receptor structurally related to MHC class I antigens. Nature. 1989;337:184–187. doi: 10.1038/337184a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bjorkman PJ, Parham P. Structure, function, and diversity of class I major histocompatibility complex molecules. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:253–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.001345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wernick NLB, Haucke V, Simister NE. Recognition of the tryptophan-based endocytosis signal in the neonatal Fc Receptor by the mu subunit of adaptor protein-2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7309–7316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410752200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newton EE, Wu Z, Simister NE. Characterization of basolateral-targeting signals in the neonatal Fc receptor. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2461–2469. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahouse JJ, Hagerman CL, Mittal P, Gilbert DJ, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Simister NE. Mouse MHC class I-like Fc receptor encoded outside the MHC. J Immunol. 1993;151:6076–6088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burmeister WP, Huber AH, Bjorkman PJ. Crystal structure of the complex of rat neonatal Fc receptor with Fc. Nature. 1994;372:379–383. doi: 10.1038/372379a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kandil E, Noguchi M, Ishibashi T, Kasahara M. Structural and phylogenetic analysis of the MHC class I-like Fc receptor gene. J Immunol. 1995;154:5907–5918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Story CM, Mikulska JE, Simister NE. A major histocompatibility complex class I-like Fc receptor cloned from human placenta: possible role in transfer of immunoglobulin G from mother to fetus. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2377–2381. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adamski FM, King AT, Demmer J. Expression of the Fc receptor in the mammary gland during lactation in the marsupial Trichosurus vulpecula (brushtail possum) Mol Immunol. 2000;37:435–444. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(00)00065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kacskovics I, Wu Z, Simister NE, Frenyó LV, Hammarström L. Cloning and characterization of the bovine MHC class I-like Fc receptor. J Immunol. 2000;164:1889–1897. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kacskovics I, Mayer B, Kis Z, Frenyó LV, Zhao Y, Muyldermans S, Hammarström L. Cloning and characterization of the dromedary (Camelus dromedarius) neonatal Fc receptor (drFcRn) Dev Comp Immunol. 2006;30:1203–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayer B, Zolnai A, Frenyó LV, Jancsik V, Szentirmay Z, Hammarström L, Kacskovics I. Redistribution of the sheep neonatal Fc receptor in the mammary gland around the time of parturition in ewes and its localization in the small intestine of neonatal lambs. Immunology. 2002;107:288–296. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01514.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schnulle PM, Hurley WL. Sequence and expression of the FcRn in the porcine mammary gland. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2003;91:227–231. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(02)00294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin WL, West APJ, Gan L, Bjorkman PJ. Crystal structure at 2.8 A of an FcRn/heterodimeric Fc complex: mechanism of pH-dependent binding. Mol Cell. 2001;7:867–877. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim JK, Tsen MF, Ghetie V, Ward ES. Identifying amino acid residues that influence plasma clearance of murine IgG1 fragments by site-directed mutagenesis. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:542–548. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim JK, Firan M, Radu CG, Kim CH, Ghetie V, Ward ES. Mapping the site on human IgG for binding of the MHC class I-related receptor. FcRn. Eur. J. Immunol. 1999;29:2819–2825. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199909)29:09<2819::AID-IMMU2819>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Medesan C, Radu C, Kim JK, Ghetie V, Ward ES. Localization of the site of the IgG molecule that regulates maternofetal transmission in mice. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2533–2536. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vaughn DE, Milburn CM, Penny DM, Martin WL, Johnson JL, Bjorkman PJ. Identification of critical IgG binding epitopes on the neonatal Fc receptor. J Mol Biol. 1997;274:597–607. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bitonti AJ, Dumont JA, Low SC, Peters RT, Kropp KE, Palombella VJ, Stattel JM, Lu Y, Tan CA, Song JJ, Garcia AM, Simister NE, Spiekermann GM, Lencer WI, Blumberg RS. Pulmonary delivery of an erythropoietin Fc fusion protein in non-human primates through an immunoglobulin transport pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9763–9768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403235101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dickinson BL, Badizadegan K, Wu Z, Ahouse JC, Zhu X, Simister NE, Blumberg RS, Lencer WI. Bidirectional FcRn-dependent IgG transport in a polarized human intestinal epithelial cell line. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:903–911. doi: 10.1172/JCI6968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dickinson BL, Claypool SM, D’Angelo JA, Aiken ML, Venu N, Yen EH, Wagner JS, Borawski JA, Pierce AT, Hershberg R, Blumberg RS, Lencer WI. Ca2 +-dependent calmodulin binding to FcRn affects immunoglobulin G transport in the transcytotic pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:414–423. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-07-0658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haymann J, Delarue F, Baud L, Sraer J. Aggregated IgG bind to glomerular epithelial cells to stimulate urokinase release through an endocytosis-independent process. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2004;98:e13–e21. doi: 10.1159/000079928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sakagami M, Omidi Y, Campbell L, Kandalaft LE, Morris CJ, Barar J, Gumbleton M. Expression and transport functionality of FcRn within rat alveolar epithelium: a study in primary cell culture and in the isolated perfused lung. Pharm Res. 2006;23:270–279. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-9226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kobayashi N, Suzuki Y, Tsuge T, Okumura K, Ra C, Tomino Y. FcRn-mediated transcytosis of immunoglobulin G in human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;282:F358–F365. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.0164.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoshida M, Claypool SM, Wagner JS, Mizoguchi E, Mizoguchi A, Roopenian DC, Lencer WI, Blumberg RS. Human neonatal Fc receptor mediates transport of IgG into luminal secretions for delivery of antigens to mucosal dendritic cells. Immunity. 2004;20:769–783. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spiekermann GM, Finn PW, Ward ES, Dumont J, Dickinson BL, Blumberg RS, Lencer WI. Receptor-mediated immunoglobulin G transport across mucosal barriers in adult life: functional expression of FcRn in the mammalian lung. J Exp Med. 2002;196:303–310. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tzaban S, Massol RH, Yen E, Hamman W, Frank SR, Lapierre LA, Hansen SH, Goldenring JR, Blumberg RS, Lencer WI. The recycling and transcytotic pathways for IgG transport by FcRn are distinct and display an inherent polarity. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:673–684. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dumont JA, Bitonti AJ, Clark D, Evans S, Pickford M, Newman SP. Delivery of an erythropoietin-Fc fusion protein by inhalation in humans through an immunoglobulin transport pathway. J Aerosol Med. 2005;18:294–303. doi: 10.1089/jam.2005.18.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bitonti AJ, Dumont JA. Pulmonary administration of therapeutic proteins using an immunoglobulin transport pathway. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:1106–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoshida M, Kobayashi K, Kuo TT, Bry L, Glickman JN, Claypool SM, Kaser A, Nagaishi T, Higgins DE, Mizoguchi E, Wakatsuki Y, Roopenian DC, Mizoguchi A, Lencer WI, Blumberg RS. Neonatal Fc receptor for IgG regulates mucosal immune responses to luminal bacteria. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2142–2151. doi: 10.1172/JCI27821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ghetie V, Ward ES. Transcytosis and catabolism of antibody. Immunol Res. 2002;25:97–113. doi: 10.1385/IR:25:2:097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ward ES, Ober RJ. Chapter 4: multitasking by exploitation of intracellular transport functions the many faces of FcRn. Adv Immunol. 2009;103:77–115. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(09)03004-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu X, Meng G, Dickinson BL, Li X, Mizoguchi E, Miao L, Wang Y, Robert C, Wu B, Smith PD, Lencer WI, Blumberg RS. MHC class I-related neonatal Fc receptor for IgG is functionally expressed in monocytes, intestinal macrophages, and dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:3266–3276. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Akilesh S, Huber TB, Wu H, Wang G, Hartleben B, Kopp JB, Miner JH, Roopenian DC, Unanue ER, Shaw AS. Podocytes use FcRn to clear IgG from the glomerular basement membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:967–972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711515105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mi W, Wanjie S, Lo S, Gan Z, Pickl-Herk B, Ober RJ, Ward ES. Targeting the neonatal fc receptor for antigen delivery using engineered fc fragments. J Immunol. 2008;181:7550–7561. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Montoyo HP, Vaccaro C, Hafner M, Ober RJ, Mueller W, Ward ES. Conditional deletion of the MHC class I-related receptor FcRn reveals the sites of IgG homeostasis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2788–2793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810796106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim H, Fariss RN, Zhang C, Robinson SB, Thill M, Csaky KG. Mapping of the neonatal Fc receptor in the rodent eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2025–2029. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qiao S, Kobayashi K, Johansen F, Sollid LM, Andersen JT, Milford E, Roopenian DC, Lencer WI, Blumberg RS. Dependence of antibody-mediated presentation of antigen on FcRn. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9337–9342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801717105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brambell FW, Hemmings WA, Morris IG. A theoretical model of gamma-globulin catabolism. Nature. 1964;203:1352–1354. doi: 10.1038/2031352a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Junghans RP, Anderson CL. The protection receptor for IgG catabolism is the beta2-microglobulin-containing neonatal intestinal transport receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5512–5516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ghetie V, Hubbard JG, Kim JK, Tsen MF, Lee Y, Ward ES. Abnormally short serum half-lives of IgG in beta 2-microglobulin-deficient mice. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:690–696. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Israel EJ, Wilsker DF, Hayes KC, Schoenfeld D, Simister NE. Increased clearance of IgG in mice that lack beta 2-microglobulin: possible protective role of FcRn. Immunology. 1996;89:573–578. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-775.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roopenian DC, Christianson GJ, Sproule TJ, Brown AC, Akilesh S, Jung N, Petkova S, Avanessian L, Choi EY, Shaffer DJ, Eden PA, Anderson CL. The MHC class I-like IgG receptor controls perinatal IgG transport, IgG homeostasis, and fate of IgG-Fc-coupled drugs. J Immunol. 2003;170:3528–3533. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu Z, Roopenian DC, Zhou X, Christianson GJ, Diaz LA, Sedmak DD, Anderson CL. Beta2-microglobulin-deficient mice are resistant to bullous pemphigoid. J Exp Med. 1997;186:777–783. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.5.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marino M, Ruvo M, Falco SD, Fassina G. Prevention of systemic lupus erythematosus in MRL/lpr mice by administration of an immunoglobulin-binding peptide. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:735–739. doi: 10.1038/77296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Akilesh S, Petkova S, Sproule TJ, Shaffer DJ, Christianson GJ, Roopenian D. The MHC class I-like Fc receptor promotes humorally mediated autoimmune disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1328–1333. doi: 10.1172/JCI18838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sesarman A, Sitaru AG, Olaru F, Zillikens D, Sitaru C. Neonatal Fc receptor deficiency protects from tissue injury in experimental epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. J Mol Med. 2008;86:951–959. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0366-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu L, Garcia AM, Santoro H, Zhang Y, McDonnell K, Dumont J, Bitonti A. Amelioration of experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis in rats by neonatal FcR blockade. J Immunol. 2007;178:5390–5398. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li N, Zhao M, Hilario-Vargas J, Prisayanh P, Warren S, Diaz LA, Roopenian DC, Liu Z. Complete FcRn dependence for intravenous Ig therapy in autoimmune skin blistering diseases. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3440–3450. doi: 10.1172/JCI24394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Deng R, Balthasar JP. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling of IVIG effects in a murine model of immune thrombocytopenia. J Pharm Sci. 2007;96:1625–1637. doi: 10.1002/jps.20828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Petkova SB, Akilesh S, Sproule TJ, Christianson GJ, Al Khabbaz H, Brown AC, Presta LG, Meng YG, Roopenian DC. Enhanced half-life of genetically engineered human IgG1 antibodies in a humanized FcRn mouse model: potential application in humorally mediated autoimmune disease. Int Immunol. 2006;18:1759–1769. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Raghavan M, Chen MY, Gastinel LN, Bjorkman PJ. Investigation of the interaction between the class I MHC-related Fc receptor and its immunoglobulin G ligand. Immunity. 1994;1:303–315. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kazatchkine MD, Kaveri SV. Immunomodulation of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases with intravenous immune globulin. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:747–755. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra993360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Anti-inflammatory actions of intravenous immunoglobulin. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:513–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hansen RJ, Balthasar JP. Intravenous immunoglobulin mediates an increase in anti-platelet antibody clearance via the FcRn receptor. Thromb Haemost. 2002;88:898–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hansen RJ, Balthasar JP. Effects of intravenous immunoglobulin on platelet count and antiplatelet antibody disposition in a rat model of immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2002;100:2087–2093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hansen RJ, Balthasar JP. IVIG effects on autoantibody elimination. Allergy. 2004;59:1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00479_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hansen RJ, Balthasar JP. Mechanisms of IVIG action in immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Clin Lab. 2004;50:133–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Martín MG, Wu SV, Walsh JH. Hormonal control of intestinal Fc receptor gene expression and immunoglobulin transport in suckling rats. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2844–2849. doi: 10.1172/JCI116528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim K, Fandy TE, Lee VHL, Ann DK, Borok Z, Crandall ED. Net absorption of IgG via FcRn-mediated transcytosis across rat alveolar epithelial cell monolayers. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L616–L622. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00121.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Andersen JT, Justesen S, Berntzen G, Michaelsen TE, Lauvrak V, Fleckenstein B, Buus S, Sandlie I. A strategy for bacterial production of a soluble functional human neonatal Fc receptor. J Immunol Methods. 2008;331:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Getman KE, Balthasar JP. Pharmacokinetic effects of 4C9, an anti-FcRn antibody, in rats: implications for the use of FcRn inhibitors for the treatment of humoral autoimmune and alloimmune conditions. J Pharm Sci. 2005;94:718–729. doi: 10.1002/jps.20297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vaccaro C, Zhou J, Ober RJ, Ward ES. Engineering the Fc region of immunoglobulin G to modulate in vivo antibody levels. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1283–1288. doi: 10.1038/nbt1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vaccaro C, Bawdon R, Wanjie S, Ober RJ, Ward ES. Divergent activities of an engineered antibody in murine and human systems have implications for therapeutic antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18709–18714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606304103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dall’Acqua WF, Cook KE, Damschroder MM, Woods RM, Wu H. Modulation of the effector functions of a human IgG1 through engineering of its hinge region. J Immunol. 2006;177:1129–1138. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mezo AR, McDonnell KA, Hehir CAT, Low SC, Palombella VJ, Stattel JM, Kamphaus GD, Fraley C, Zhang Y, Dumont JA, Bitonti AJ. Reduction of IgG in nonhuman primates by a peptide antagonist of the neonatal Fc receptor FcRn. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2337–2342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708960105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chaudhury C, Mehnaz S, Robinson JM, Hayton WL, Pearl DK, Roopenian DC, Anderson CL. The major histocompatibility complex-related Fc receptor for IgG (FcRn) binds albumin and prolongs its lifespan. J Exp Med. 2003;197:315–322. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bruhns P, Samuelsson A, Pollard JW, Ravetch JV. Colony-stimulating factor-1-dependent macrophages are responsible for IVIG protection in antibody-induced autoimmune disease. Immunity. 2003;18:573–581. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Samuelsson A, Towers TL, Ravetch JV. Anti-inflammatory activity of IVIG mediated through the inhibitory Fc receptor. Science. 2001;291:484–486. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5503.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Liu X, Ye L, Christianson GJ, Yang J, Roopenian DC, Zhu X. NF-kappaB signaling regulates functional expression of the MHC class I-related neonatal Fc receptor for IgG via intronic binding sequences. J Immunol. 2007;179:2999–3011. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu X, Ye L, Bai Y, Mojidi H, Simister NE, Zhu X. Activation of the JAK/STAT-1 signaling pathway by IFN-gamma can down-regulate functional expression of the MHC class I-related neonatal Fc receptor for IgG. J Immunol. 2008;181:449–463. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dall’Acqua WF, Woods RM, Ward ES, Palaszynski SR, Patel NK, Brewah YA, Wu H, Kiener PA, Langermann S. Increasing the affinity of a human IgG1 for the neonatal Fc receptor: biological consequences. J Immunol. 2002;169:5171–5180. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Presta LG. Molecular engineering and design of therapeutic antibodies. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:460–470. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ghetie V, Popov S, Borvak J, Radu C, Matesoi D, Medesan C, Ober RJ, Ward ES. Increasing the serum persistence of an IgG fragment by random mutagenesis. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:637–640. doi: 10.1038/nbt0797-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lazar GA, Dang W, Karki S, Vafa O, Peng JS, Hyun L, Chan C, Chung HS, Eivazi A, Yoder SC, Vielmetter J, Carmichael DF, Hayes RJ, Dahiyat BI. Engineered antibody Fc variants with enhanced effector function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4005–4010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508123103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zalevsky J, Chamberlain AK, Horton HM, Karki S, Leung IWL, Sproule TJ, Lazar GA, Roopenian DC, Desjarlais JR (2010) Enhanced antibody half-life improves in vivo activity. Nat Biotechnol. doi:10.1038/nbt.1601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 102.Miller SD, Turley DM, Podojil JR. Antigen-specific tolerance strategies for the prevention and treatment of autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:665–677. doi: 10.1038/nri2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hinton PR, Johlfs MG, Xiong JM, Hanestad K, Ong KC, Bullock C, Keller S, Tang MT, Tso JY, Vásquez M, Tsurushita N. Engineered human IgG antibodies with longer serum half-lives in primates. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6213–6216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Dall’Acqua WF, Kiener PA, Wu H. Properties of human IgG1 s engineered for enhanced binding to the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23514–23524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604292200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yeung YA, Leabman MK, Marvin JS, Qiu J, Adams CW, Lien S, Starovasnik MA, Lowman HB. Engineering human IgG1 affinity to human neonatal Fc receptor: impact of affinity improvement on pharmacokinetics in primates. J Immunol. 2009;182:7663–7671. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Datta-Mannan A, Witcher DR, Tang Y, Watkins J, Wroblewski VJ. Monoclonal antibody clearance. Impact of modulating the interaction of IgG with the neonatal Fc receptor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1709–1717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607161200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Jakobovits A, Amado RG, Yang X, Roskos L, Schwab G. From XenoMouse technology to panitumumab, the first fully human antibody product from transgenic mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1134–1143. doi: 10.1038/nbt1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Scott CT. Mice with a human touch. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1075–1077. doi: 10.1038/nbt1007-1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lindstrom JM, Seybold ME, Lennon VA, Whittingham S, Duane DD. Antibody to acetylcholine receptor in myasthenia gravis. Prevalence, clinical correlates, and diagnostic value. Neurology. 1976;26:1054–1059. doi: 10.1212/wnl.26.11.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hoch W, McConville J, Helms S, Newsom-Davis J, Melms A, Vincent A. Auto-antibodies to the receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK in patients with myasthenia gravis without acetylcholine receptor antibodies. Nat Med. 2001;7:365–368. doi: 10.1038/85520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kusunoki S, Iwamori M, Chiba A, Hitoshi S, Arita M, Kanazawa I. GM1b is a new member of antigen for serum antibody in Guillain–Barré syndrome. Neurology. 1996;47:237–242. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.McKnight K, Jiang Y, Hart Y, Cavey A, Wroe S, Blank M, Shoenfeld Y, Vincent A, Palace J, Lang B. Serum antibodies in epilepsy and seizure-associated disorders. Neurology. 2005;65:1730–1736. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187129.66353.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Thieben MJ, Lennon VA, Boeve BF, Aksamit AJ, Keegan M, Vernino S. Potentially reversible autoimmune limbic encephalitis with neuronal potassium channel antibody. Neurology. 2004;62:1177–1182. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000122648.19196.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hayes KC, Hull TCL, Delaney GA, Potter PJ, Sequeira KAJ, Campbell K, Popovich PG. Elevated serum titers of proinflammatory cytokines and CNS autoantibodies in patients with chronic spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2002;19:753–761. doi: 10.1089/08977150260139129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Singer HS, Loiselle CR, Lee O, Minzer K, Swedo S, Grus FH. Anti-basal ganglia antibodies in PANDAS. Mov Disord. 2004;19:406–415. doi: 10.1002/mds.20052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Vernino S, Lennon VA. Ion channel and striational antibodies define a continuum of autoimmune neuromuscular hyperexcitability. Muscle Nerve. 2002;26:702–707. doi: 10.1002/mus.10266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Barber PA, Anderson NE, Vincent A. Morvan’s syndrome associated with voltage-gated K + channel antibodies. Neurology. 2000;54:771–772. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.3.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lebar R, Lubetzki C, Vincent C, Lombrail P, Boutry JM. The M2 autoantigen of central nervous system myelin, a glycoprotein present in oligodendrocyte membrane. Clin Exp Immunol. 1986;66:423–434. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]