Abstract

The physiological state of eukaryotic DNA is chromatin. Nucleosomes, which consist of DNA in complex with histones, are the fundamental unit of chromatin. The post-translational modifications (PTMs) of histones play a critical role in the control of gene transcription, epigenetics and other DNA-templated processes. It has been known for several years that these PTMs function in concert to allow for the storage and transduction of highly specific signals through combinations of modifications. This code, the combinatorial histone code, functions much like a bar code or combination lock providing the potential for massive information content. The capacity to directly measure these combinatorial histone codes has mostly been laborious and challenging, thus limiting efforts often to one or two samples. Recently, progress has been made in determining such information quickly, quantitatively and sensitively. Here we review both the historical and recent progress toward routine and rapid combinatorial histone code analysis.

Keywords: Histone code, Mass spectrometry, Combinatorial, Modification, Proteomic, Methylation, Acetylation, Histone

Introduction

Eukaryotic nuclear DNA is nominally compacted into chromatin fibers. Nucleosomes, consisting of an approximately 150-base pair section of DNA wrapped around an octameric protein complex, are the common building block of these chromatin fibers [1]. The core protein complex is made up of highly conserved histone proteins, and ultimately these proteins play an important role in controlling access to the underlying DNA. This forms a system of gene regulation, the development of which was likely a major evolutionary advancement resulting in much of the biodiversity observable today [2]. There are no truly multicellular life forms without a chromatin-based system. The fundamental features of this system, especially the histone amino acid sequences, are nearly identical from lower eukaryotes, such as yeast, to humans, suggesting little evolution since its inception. Thus, chromatin and the core histones are a critical and near universal aspect of higher organisms that are deserving of intensive study. At the same time, histones are some of the most challenging biomolecules to characterize and have been a focus of analytical sciences, including separation sciences and more recently mass spectrometry.

There are four families of core histone proteins: H2A, H2B, H3 and H4. Each histone consists of a structured domain at the center of the nucleosome and an outward-facing structurally dynamic N-terminal tail. The N-terminal regions of histone proteins are exceptionally basic and prone to a variety of post-translational modifications (PTMs) at a set of unusually close sites, frequently in complex combinations. Certain histones also have unstructured C-terminal tails that are similarly prone to PTM. The core regions of histones can also be modified, although these PTMs occur less densely and frequently. The commonly observed histone PTMs include lysine acetylation, lysine (mono-, di- and tri-) methylation, arginine (mono- and di-) methylation, and serine and threonine phosphorylation. Other less abundant modifications include ADP ribosylation, proline isomerization, arginine deimination, ubiquitylation/ubiquitination and sumoylation (see Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 for a summary of the histone modifications reported in the literature to date). Clearly when these modifications are considered in combination, not only is the potential complexity great, but the potential information content is astounding.

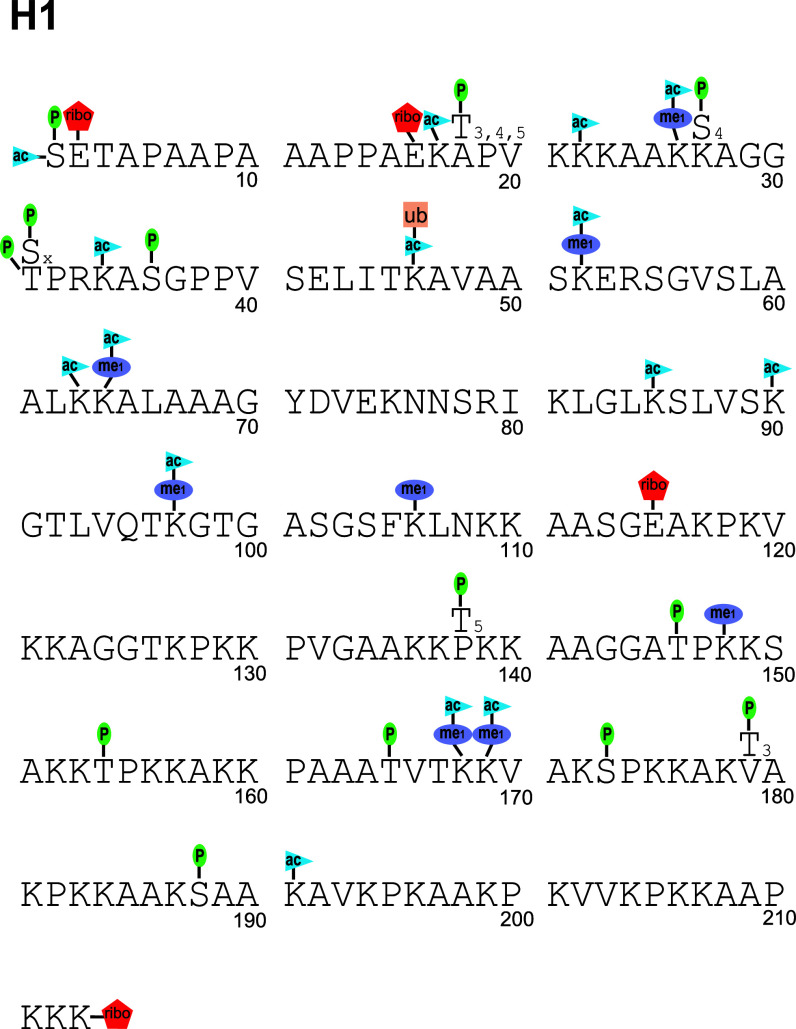

Fig. 1.

The post-translational modifications of histone H1 reported in the literature (ac acetylation, me1 monomethylation, P phosphorylation, ribo ADP ribosylation, ub ubiquitination/ubiquitylation). Unlike other histones, the numbering of H1 has generally included the N-terminal methionine; thus, we start sequence numbering at two. The sequence and numbering scheme for human histone H1.2 is shown, and PTMs of other variants are adjusted to their homologous H1.2 site. Sequence-specific PTMs of other variants not consistent with the H1.2 sequence are shown by including the alternate amino acid above the sequence. The variants for which this alternate amino acid occur at a homologous point are shown in the subscript on the alternate amino acid. Not all modifications are well validated, and there are substantial gaps in our knowledge of which PTMs occur on which variants. Some have only been observed on one or two variants, but are assumed to occur on other variants due to homology. The acetylation at S2 is N-terminal. The ribosylation at K213 is C-terminal

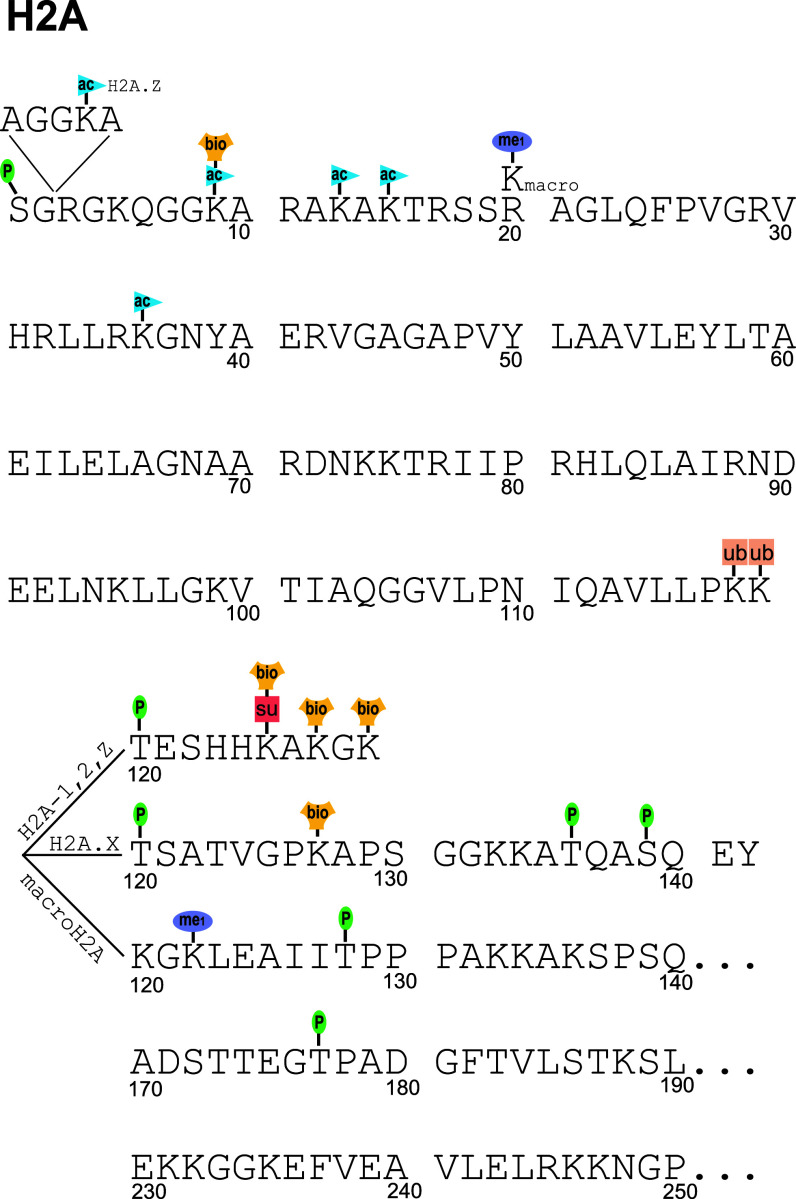

Fig. 2.

The post-translational modifications of histone H2A reported in the literature (ac acetylation, me1 monomethylation, P phosphorylation, ribo ADP ribosylation, ub ubiquitination/ubiquitylation, bio biotinylation). The core sequence and numbering scheme for human histone H2a.1 is shown, and PTMs of other variants are adjusted to their homologous H2a.1 site. Divergent sequences of other variants at the termini are shown as such. Sequence-specific PTMs of other variants not consistent with the H2a.1 sequence are shown by including the alternate amino acid above the sequence. The variants for which this alternate amino acid occurs at a homologous point are shown in the subscript on the alternate amino acid. Not all modifications are well validated, and there are substantial gaps in our knowledge of which PTMs occur on which variants. Some have only been observed on one or two variants, but are assumed to occur on other variants due to homology

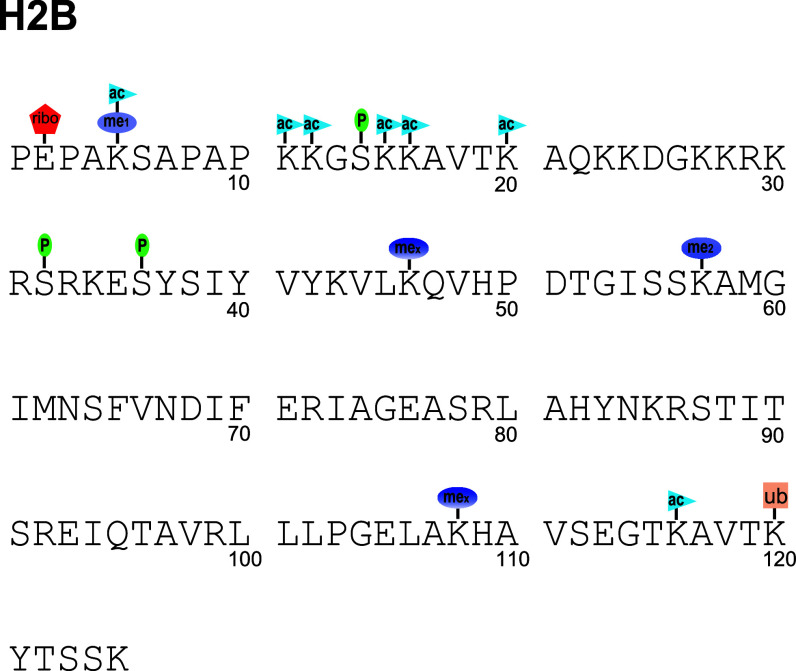

Fig. 3.

The post-translational modifications of histone H2B reported in the literature (ac acetylation, me1 monomethylation, me2 dimethylation, mex unspecified methylation degree, P phosphorylation, ribo ADP ribosylation, ub ubiquitination/ubiquitylation). The sequence and numbering scheme for human histone H2b.1 is shown, and PTMs of other variants are adjusted to their homologous H2b.1 site. Sequence-specific PTMs of other variants not consistent with the H2b.1 sequence are shown by including the alternate amino acid above the sequence. The variants for which this alternate amino acid occurs at a homologous point are shown in the subscript on the alternate amino acid. Not all modifications are well validated, and there are substantial gaps in our knowledge of which PTMs occur on which variants. Some have only been observed on one or two variants, but are assumed to occur on other variants due to homology

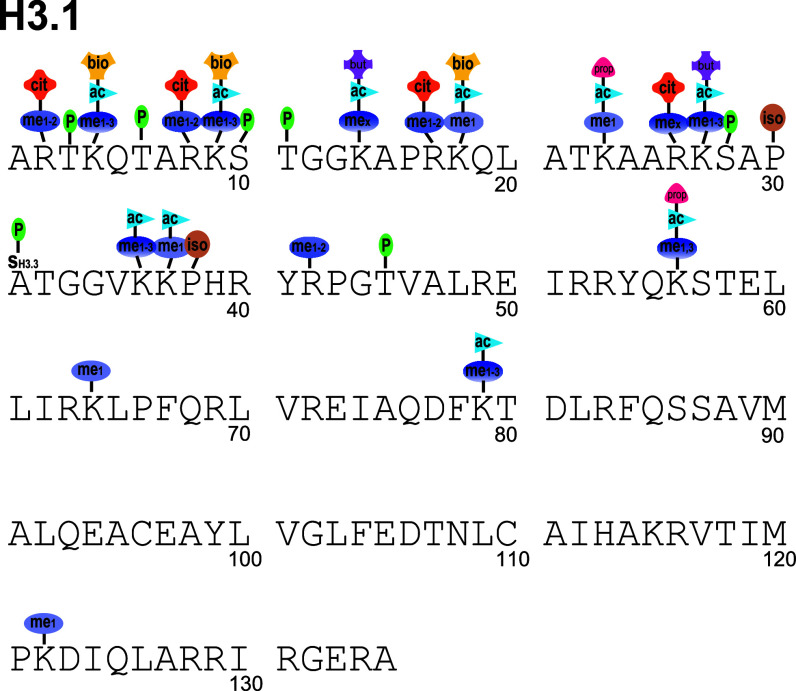

Fig. 4.

The post-translational modifications of histone H3 reported in the literature [ac acetylation, me1 monomethylation, me1–2 mono- and dimethylation, me1–3 mono-, di- and trimethylation, me1,3 mono- and trimethylation (di- likely but unreported), mex unspecified methylation degree, P phosphorylation, bio biotinylation, iso proline isomerization, prop proprionylation, cit citrulination, but butylation). The sequence and numbering scheme for human histone H3.1 is shown, and PTMs of other variants are adjusted to their homologous H3.1 site. The one sequence-specific PTM of H3.3S31ph is shown by including the alternate amino acid above the sequence. Not all modifications are well validated, and there are substantial gaps in our knowledge of which PTMs occur on which variants. Some have only been observed on one or two variants, but are assumed to occur on other variants due to homology

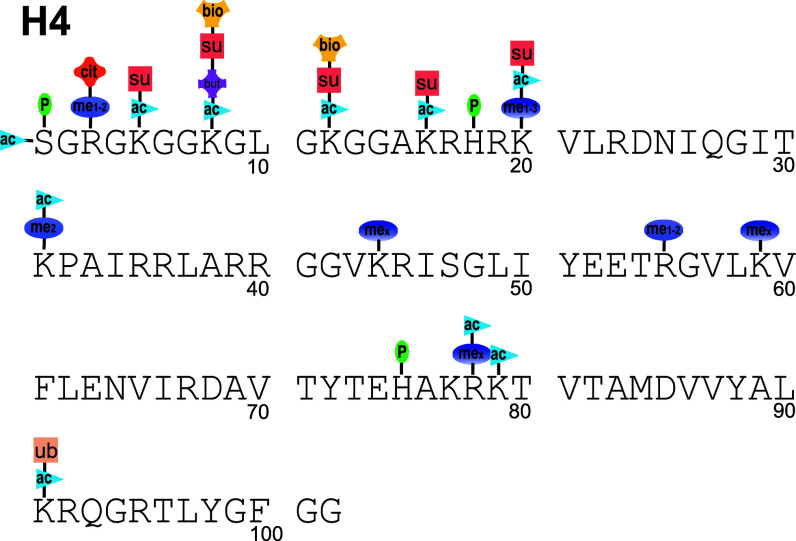

Fig. 5.

The post-translational modifications of histone H4 reported in the literature (ac acetylation, me2 dimethylation, me1–2 mono- and dimethylation, me1–3 mono-, mex unspecified methylation degree, P phosphorylation, bio biotinylation, cit citrulination, but butylation, ub ubiquitination/ubiquitylation, su sumoylation). Unlike the other histones, there is only a single variant of histone H4. Not all modifications listed are well validated

Each histone can be reversibly modified at multiple sites by specific histone-modifying enzymes, and many have multiple sequence variants. Permutations of all the individual sites and types of modifications previously observed on a site-by-site basis result in millions of distinct multiply-modified histone forms. These modifications and the combinations thereof constitute an epigenetic code, the histone code, which acts as an information-rich signal readable by effector molecules involved in a variety of DNA processes ultimately controlling gene transcription levels and cellular phenotypes [3–6]. Epigenetics is the primary means by which multicellular organisms differentiate specialized cells despite each cell containing essentially identical genetic material [7]. Conversely, the deliberate manipulation of epigenetics is the key to the production of stem cells from adult tissue and tissue engineering [7]. Epigenetic regulation also plays other roles, such as adaptation to environment, while epigenetic dysregulation of cells impacts diseases such as cancer [7]. Thus, the complete characterization of biologically encoded epigenetic information with the goal of understanding the underlying epigenetic code and the eventual sequencing of epigenomes is a goal of modern biology.

As will be shown, the analytical challenges of characterizing histone PTMs, particularly when considered in combination (i.e., modifications that co-exist on the same molecule), are great and have created a new challenge for chromatin researchers. Yet, all indications are that histone modifications are central to many aspects of eukaryotic biology, and understanding this enigmatic code could potentially yield great returns scientifically and even biomedically. The ability to determine which PTMs co-exist on a given histone molecule has only recently been developed, and the capacity to do so rapidly and accurately is presently emergent. In this review article we will cover the fundamentals that enable high-throughput-combinatorial histone code analysis (HT-CHCA) methods (such as physical separations and peptide sequencing). We will review work that has contributed to the evolution of HT-CHCA and recent HT-CHCA methods. We will also review computational approaches to cope with the inherent complexity of HT-CHCA proteomic data.

Do combinations of histone post-translational modifications matter?

The analysis of histone modifications and their role in biology has been an area of active and intense research for more than 40 years. Many biological roles have been attributed to individual modifications at specific sites on a given histone using a variety of means. It is beyond the scope of this review to comprehensively cover all of the evidence linking biological functions to individual histone modifications, and there are recent reviews that cover aspects of this in great detail [5, 8–10]. The distributions of where individual histone modifications reside within genomes have also been intensively studied recently using ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq technologies (Chromatin Immunopreciptiation-DNA microarrray chip and Chromatin Immunopreciptiation-DNA sequencing, respectively) [11]. It has been hypothesized for many years that these modifications may function in concert rather than simply as independent signals [4]. There have been an increasing number of reports demonstrating specific combinatorial functions of sets of modifications. Also, the analysis of data sets that consider all observed modifications globally, despite being measured independently and en masse, appear to distinguish between specific biological states, such as cancer progression [12–15].

Nucleosomal/genomic evidence for combinatorial histone codes

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) is a powerful means of enriching chromatin for targeted epitopes using antibodies toward either specific histone modifications or other chromatin-associated proteins. This has been used in conjunction with either DNA micro-array technology (ChIP-chip) or “next generation sequencing,” such as Illumina’s Solexa or 454 Life Science’s sequencing technology, (ChIP-seq), to read the DNA sequences associated with the precipitated chromatin. This provides information on the genomic localization of histone modifications and other targeted proteins as well as the placement of the nucleosome within the genome with a resolution greater than the number of base pairs occupied by a nucleosome. This approach has been revolutionary to understanding chromatin and epigenetics. It has also provided significant, although somewhat circumstantial, evidence for the combinatorial nature of histone codes. By analyzing for multiple histone modifications on a given sample, the genomic localizations of modifications can be correlated. Within this data is strong evidence of the importance of combinatorial effects in the histone code. Dion et al. investigated the combinatorial nature of acetylations on the histone H4 tail in budding yeast by mutation of the amino acid sequence to mimic either a fixed acetylated residue or fixed unmodified residue in many possible combinations. The effect on gene expression was measured by DNA microarray. Lysine 16 appeared to have a specific effect on a small set of genes largely independent of the other acetylation states, whereas the other sites (K5, K8 and K12) appeared to have a broader and cumulative effect [16]. The occurrence of combinations involving 12 histone modifications on thousands of nucleosomes in actively growing Saccharomyces cerevisiae was investigated by Liu et al. using high-resolution ChIP-chip. These data showed a sharply defined domain of two hypo-acetylated nucleosomes, adjacent to the transcriptional start site, which appeared unrelated to transcription levels. Within the coding region of the gene, modifications occurred in gradients in a pattern that was associated with transcription. They concluded that nucleosomes from different parts of the gene are distinct in their modification patterns. They did not find evidence of distinct deterministic codes, but rather a more continuous scale where somewhat redundant modifications are additive in their effect [17]. Kurdistani et al. analyzed 11 lysines in the four core histones of S. cerevisiae with ChIP-chip and found patterns of acetylation that define groups of biologically related genes. They also demonstrated how certain acetylation patterns serve as a means of recruiting specific proteins such as transcription factors, a process that may coordinate gene expression patterns among related genes. Interestingly, transcription factor Bdf1 appeared to have an affinity for deacetylated H4K16, making the point that combinatorial patterns are also encoded by the absence of variable modifications as well [18]. Another study analyzed 39 histone modifications in human CD4+ T cells and found patterns of histone modifications associated with promoters and enhancers. They identified a module of 17 modifications that tend to co-localize in the genome at promoters and correlate with each other at an individual nucleosome. The expression levels of genes with this module, as determined by microarray, were generally high and could be further enhanced by additional modifications. Although this type of data does not provide any direct evidence of coexistence on a single nucleosome per se, it is concluded based on the preponderance of correlative evidence that modifications have a cooperative effect, acting not as independent signals, but rather in a combinatorial manner [19].

However convincing the evidence for combinatorial effects based on these genomic lines of evidence, the nature of all of these experiments are often correlative and typically represent an average of multiple cells. Such measurements do not localize two modifications on a single histone molecule, and usually neighboring reads are not necessarily on the same strand of DNA. A few studies, however, have reasonably localized modifications to individual nucleosomes by use of sequential ChIPs (aka ChIP-reChIP) [20, 21]. The future of such approaches is promising and actually provides complementary information to molecular level combinatorial PTM information. Overall, clearly these experiments have elucidated vast information on how histone modifications likely function in concert.

Linking combinatorial histones codes to biological function

In the past few years there have been multiple studies designed to link patterns of multiple histone modifications measured in parallel to biological function. Cancer histological studies have been very successful in correlating the overall observed histone modification state to clinical outcome, but mostly without revealing the underlying reason such patterns are observed in these pathologies. On the other hand, a number of recent studies have determined specific roles of combinatorial histone modifications in certain biological processes, sometimes with great detail.

Many very compelling studies done with the goals of improving cancer diagnostics and treatment plans have shown the importance of combinatorial histone codes in disease processes. One study was able to find global histone modification patterns with clinical diagnostic and predictive capacity in prostrate cancer patients. They identified two disease subtypes that exhibited different tumor recurrence rates. The identified histone modification patterns used to distinguish subtypes were predictive of outcome independently of other commonly used measures of recurrence risk [15]. Barlesi et al. used immunohistochemistry on non-small-cell lung cancer samples to again measure global histone modification patterns using modification-specific antibodies and recursive partitioning analysis on the whole panel of modifications. They reported excellent predictive value, particularly in the combined H3K4me2 and H3K9ac data (both generally considered transcriptionally active marks) [12]. Another immunohistochemistry study evaluated the patterns of acetylation and trimethylation on both histone H3 and histone H4 in gastric adenocarcinomas. They found strong evidence of the diagnostic potential of H3K9 trimethylation alone and the overall modification patterns collectively [22]. Human breast carcinomas were studied by similar histological methods along with clustering analysis of the samples with respect to the panel of histone modifications studied [13]. This analysis revealed three groups showing distinct histone modification patterns, and these correlated well with other prognostic indicators and clinical outcome. Overall, the potential of such histone PTM biomarkers has drawn significant attention particularly because these results are interrelated to promising pharmaceutical treatment approaches that target histone modifying enzymes such as histone deacetylase inhibitors [9].

Despite the challenges of studying processes involving multiple modifications functioning in concert, a rapidly increasing number of studies have demonstrated very specific roles for certain combinations of histone modifications. Many of these studies use mass spectrometry-based combinatorial histone code analysis. Jiang et al. [23] showed through top-down mass spectrometry (sequencing of intact proteins by mass spectrometry) and gene knockdown that histone H3K4 trimethylation appears linked to acetylation of H3 at K14, K18 and K23 on the same H3 tail, thus suggesting that these known transcriptionally active marks function in concert to promote gene expression. It has recently been shown that the combination of H3T3ph, H3K4me3 and H3R8me2 serves a special purpose in mitotic cells and may signal rapid clearance of this region of chromatin through the metaphase–anaphase checkpoint [24]. Using synthetic combinatorially modified histone H3 tails, a unique interplay has been revealed between methylated lysines 9 and 27, and acetylated lysine 14 on histone H3 in the binding of the silent chromatin associated protein heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) [25]. Most interestingly, lysine 14 acetylation could dramatically enhance HP1 binding in concert with lysine 9 methylation, but showed no affinity for HP1 when present alone. Kirmizis et al. [26] showed that H3R2 dimethylation occludes Spp1, a Set1 methyltransferase subunit necessary for trimethylation of H3K4. A relationship between histone code-reading proteins and histone-writing enzymes was elucidated by Taverna et al. [27] by showing that the binding of Yng1 to H3K4me3 via its PHD (plant homeodomain) domain promotes HAT activity at H3K14 and selective transcription of certain genes. Another study focused on cellular transformation discovered a similar process involving ING4, again through a PHD domain interacting with H3K4me3, mediating crosstalk between H3K4me3 and general H3 acetylation [28]. It has also been shown that H3S10 phosphorylation plays an important role in ejecting HP1 from binding K9 trimethylated histones during M phase, acting as a binary switch [29]. A similar binary switch was found on histone H1 at K26me and S27ph by Daujat et al [30]. A library of combinatorially modified H4 tails has been used to probe the binding of JMJD2A to these tails, and it was found that K20 methylation was the primary determinant for binding, but that phosphorylation and acetylation of neighboring sites attenuated the interaction [31]. Although much of the above work clearly demonstrates the biological relevance of combinatorial histone codes, the direct physical mechanisms by which the combinatorial nature of these codes are incorporated into a biological pathway are not well characterized.

Do combinatorial histone code-reading proteins/complexes exist?

The most convincing case for the combinatorial nature of histone codes would be evidence of the direct physical interaction of a protein or protein complex with multiple PTMs, which serves an essential role in a biological process. A simple analysis of the amino acid sequences of chromatin-related proteins reveals that many contain multiple regions homologous to known PTM-recognizing domains, suggesting at least the possibility of such direct combinatorial interactions. For example, BRD4 contains two bromodomains (a protein domain that recognized acetylated lysines), and CHD5 contains two chromodomains (a protein domain that recognizes methylated lysines) as well as two PHD domains. Furthermore, when known binding partners are considered, the potential for combinatorial PTM reading is even greater as many complexes contain multiple proteins with PTM-recognizing domains. Although such evidence appears to point to a system specifically designed to be combinatorial, demonstrating combinatorial function is very challenging; however, in the past 3 years several such lines of evidence have been demonstrated. Li et al. [32] showed that the Rpd3S complex, which serves an essential role in transcription and contains both a chromodomain (in its Eaf3 subunit) and a PHD finger (in its Rco1 subunit), recognizes H3K36 methylation by combination of these two domains. These protein subunits do not recognize this PTM alone, or as members of other complexes, and in fact recognize other PTMs. Thus, the reading specificity of such complexes is itself combinatorial in nature. It has been demonstrated that targeting of the HBO1 HAT complexes to the coding region of genes occurs through multiple PHD finger interactions in a complex combinatorial manner involving both specificity to different degrees of H3K4 methylation and to H3K36 methylation [33]. Saksouk et al. conclude that this serves as a means of regulating the acetylation activity in a subtle way across the coding region of genes based on the existing methylation gradients. Interestingly, combinatorial readout does not require multiple PTM-binding domains in a given protein or complex. How a single bromodomain can read a combinatorial histone code was demonstrated by Moriniere et al. [34]. They showed that two acetylations on the histone H4 tail cooperate to specifically bind the bromodomain of Brdt. A study of malignant-brain-tumor (MBT) protein L3MBTL1 found that it recognizes mono- or dimethylation of H4K20 and H1K26. The recognition of these two sites involves binding at least two nucleosomes simultaneously. Through this combinatorial PTM recognition and the resulting complex formation, repression of transcription is induced for a specific subset of genes [35]. Ruthenburg et al. [36] make an excellent presentation of evidence in their review article on how different subunits that recognize distinct chromatin modifications link together to create multivalent interactions, which they argue is more the rule than the exception in chromatin biology.

Trans-histone code crosstalk

There are also a growing number of examples of trans-histone codes or combinatorial histone codes that span more than one of the core histones. These types of combinatorial codes are harder to analyze since they are not covalently linked. For example, Sims et al. [37] found a H4K20me1H3K9me1 trans-histone code in silent chromatin. Another instance of trans crosstalk between histone proteins on neighboring nucleosomes has also been observed in experiments analyzing the salt-dependent folding of chromatin. In particular, studies have provided strong evidence for the existence of internucleosomal contacts between unacetylated N-terminal H4 and the carboxyl-terminal alpha-helices of H2A on adjacent nucleosomes to mediate salt-dependent chromatin compaction, where the acetylation of H4K16 was demonstrated to inhibit this process [38]. It has also been shown that ubiquitination of H2B is necessary for the methylation of H3K79, and this interplay is important for gene silencing mechanisms [39]. Work presented by Lee et al. [40], where they elucidate some details of the molecular interactions that underlay this relationship, essentially revealed that H2BK123ub is involved in recruiting the machinery to methylate H3K79. Additionally, this study showed H2BK123ub has an effect on H3K4 methylation status as well. In an apparent trans-histone combinatorial code spanning three different histone modifications on three different histones, H4K20me2 and H3K79 methylations both appear to be involved in the relocation of 53BP1 to sites of DNA DSBs, and H2AX phosphorylation has been implicated in its retention [8, 41, 42].

The challenges of combinatorial histone PTM analysis

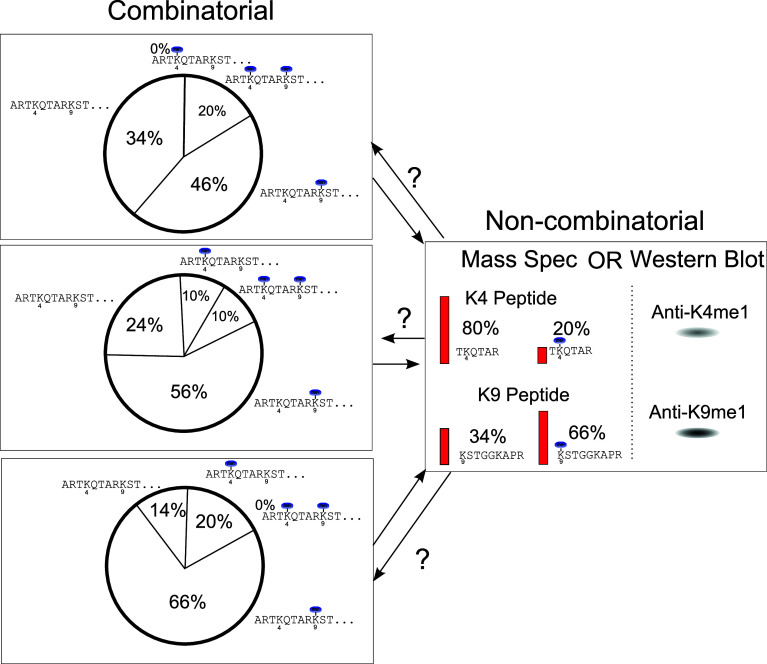

Combinatorial PTM analysis refers to the simultaneous analysis of multiple histone modifications while maintaining the molecular connectivity relationships between these modifications. That is, rather than quantitating each modification separately, each combination of modifications is detected and quantitated. As shown in Fig. 6, the relationship between these two types of data is not simple. There is a one-to-one relationship from the combinatorial data to non-combinatorial data, but not in the opposite direction. Any given combinatorial data set can be mapped to one and only one non-combinatorial result. However, a given non-combinatorial data set can result from an infinite set of combinatorial realities. Thus, the combinatorial data are more specific. As shown above, this combinatorial information does matter in biology. It is also fundamentally capable of encoding substantially more information. Non-combinatorial data, such as Western blots, are traditionally thought about as a degree of modification at each site (e.g., in Fig. 6, two sites are considered: H3K4 and H3K9). The combinatorial data, however, consist of four data points (including the doubly unmodified peptide). A system of 10 binary modifications will result in 10 non-combinatorial data points and 1,024 combinatorial data points. In the case of the plethora of modifications on histone H3, this inflates to over a trillion data points when considering all reported modifications. Essentially, combinatorial data allow us to understand how combinations of modifications on a single protein might function to transduce a different meaning than the same two modifications occurring on separate protein molecules. As detailed in previous sections, there is no reason to assume that biology does not work in this way. The complexity of combinatorial data is great and thus the separation, identification and quantitation of all of these combinatorial species is challenging. These combinatorial data are, however, much more representative of the actual modification state of a given protein.

Fig. 6.

The relationship between combinatorial data sets, such as those generated by HT-CHCA, and traditional non-combinatorial approaches, such as bottom-up mass spectrometry and Western blot analysis. For each combinatorial data set, there is exactly one corresponding non-combinatorial result. The reverse relationship is not one-to-one, and there are infinite and widely varying possible combinatorial explanations for the non-combinatorial data. The example used is of histone H3 K4 and K9 methylation. These are signals known to be of opposite meaning (gene activating and silencing, respectively), and the dimethylated form will thus have a meaning distinct from either of the monomethylated forms. Even if they act in superposition and cancel each other, this would mean that the top left example would have all gene-activating signals obliterated, while the lower left example would have a full 20% of H3 activated

Antibodies by nature measure modifications independently and are not capable of obtaining combinatorial data. These individual measurements may be considered, ex post facto, as a single concatenated data set, and some combinatorial correlations may be drawn from such an approach, but it is not truly combinatorial. Antibodies also suffer from cross-reactivity. For example, an antibody designed to recognize a particular PTM on a given residue may also recognize, at least to some degree, the same PTM on a different residue. Although many high-quality anti-histone modification antibodies are now available, they are not completely devoid of such problems. Combinatorial modifications also present a source of potential error in antibody-based methods. Neighboring modifications may occlude the epitope that the antibody recognizes despite the presence of the modification it is designed to measure. Also the signal derived from most antibodies is dependent on the affinity of the antibody for the epitope it recognizes, and thus the signal between each independent channel is not comparable on an absolute scale. Similarly, traditional bottom-up mass spectrometry, which sequences small peptides from enzymatic (most often tryptic) digests, loses most combinatorial information since the molecular connectivity is physically cleaved early in the process.

Any biological sample of histones consists of a complex mixture of remarkably physically similar combinatorially modified histone forms (combinatorial histone codes). Adding incredible challenge to an already difficult analysis is that many of these combinatorial histone codes are positional isomers of each other. There is great analytical difficulty in interrogating such a mixture. Positional isomers have identical masses and are nearly identical in all other regards, including chromatographic behavior. Some of the more common modifications on histones are methylations and acetylations, and three methyl groups have the same nominal mass as an acetyl (Δm = 0.036 Da). These modifications are difficult but not impossible to distinguish by mass alone. Perhaps the greatest difficulty of such analyses is the interrelated issues of dynamic range and sample complexity. As more sites and types of modifications are present in combination, the concentration of any given combinatorial histone code on average decreases, and the proportion of the mixture that any one makes up also decreases. The concentration and relative abundance of any analyte molecule are inversely related to the challenge of accurately and sensitively detecting it and quantitating its abundance. Combinatorial samples present us with a very complex mixture of large biomolecules that are extremely closely related and do not separate well by mass or by physical characteristics. This has until recently limited investigations into the function of histone modifications to a site-by-site basis, abrogating all direct information about the total modified state of histones.

There have been three major challenges to overcome for efficacious and efficient combinatorial histone code analysis: (1) good physical separation of forms, (2) maintenance of the connectivity information on the molecular level, and (3) sufficient throughput to perform the many requisite experiments for a biologically meaningful result. For these reasons, the analysis of histone modifications in combination on each individual molecule, referred to as combinatorial histone code analysis, has been an aspiration in the field for many years. Recently technologies have emerged and methods have been developed that make such analysis possible and even relatively high throughput. Thus, HT-CHCA is a currently emerging, yet still developing, means of probing the role of histone PTMs acting in concert in eukaryotic biology. Similar to how the current high-throughput DNA sequencers can rapidly analyze genomes, it is hoped that high-throughput combinatorial histone code analysis can eventually rapidly analyze epigenomes, or at the least contribute a significant component to such a possibility.

The separation and analysis of combinatorial histone codes

Separation of intact histones, histone variants and modified isomers

Combinatorial histone code analysis is sufficiently difficult that HT-CHCA methods benefit greatly from separation of the histones and their variants before the HT-CHCA begins. This is also beneficial as a clean-up step from other non-histone proteins that are co-purified in the acid extraction. In some cases, such as with top-down analyses, these separations are used as the primary means of chromatographic separation.

Gel electrophoresis methods have been used to separate histones for over 50 years [43]. Significant improvements and truly impressive results have been achieved, especially with AU-PAGE (acetic acid-urea-PAGE) [44], the related TAU-PAGE (AU-PAGE with added triton detergent for enhanced resolution) [45]. These related electrophoretic techniques can also be used in a 2D gel separation for even greater resolution [46]. Although the above approaches are the first to truly provide good resolution of these particularly challenging analytes, such gel-based methods are difficult to incorporate into high throughput methods as they are both labor intensive and not very compatible with other critical analytical tools in HT-CHCA, particularly mass spectrometry.

Capillary electrophoresis (HPCE) is a powerful separation technique with many distinct advantages, and significant work has been done on HPCE histone separations throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. One of the major challenges of analyzing histones by such methods is that the basic histone tails interact strongly with the surface of the fused silica tubing used in HPCE. Thus, much work has been done in minimizing this effect often by coating the capillary surface primarily with hydrophobic modifiers [47–51]. Most relevant to HT-CHCA is the work of Aguilar et al. [52], in which they used hydropropylmethylcellulose (HPMC)-coated capillaries and an MS-compatible solvent system to perform capillary electrophoresis-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (CE-ESI-MS) on calf thymus histones. Such an approach definitely continues to have potential in HT-CHCA; however, little work has followed up on this possibility. Some of the other HPCE-based histone separations that bear relevance in their methodology to later HT-CHCA work include the studies of Wiktorowicz and Colburn as well as Mizzen and McLachlan. Wiktorowicz [53] used a charge reversal strategy to repel histones from the capillary surface to achieve separation of differentially acetylated forms of H4 for the first time by HPCE. The work of Mizzen [54] introduces some degree of cation exchange behavior to the capillary surface. Related concepts arise later in liquid chromatography separations. Overall, HPCE provides excellent histone separations and has the capacity to be used on-line with mass spectrometry, making it potentially high-throughput; however, recent work in HT-CHCA has primarily focused on liquid chromatography approaches.

Reversed phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) is commonly used for the initial separation of intact histone family members and some histone variants in most of the CHCA methods in the literature today [55–58]. The reversed phase separations of histones and histone variants were extensively studied in the 1980s, first by Certa and von Ehrenstein [59] but primarily by Gurley [60–63] and Lindner [64–68]. During this time and into the 1990s, the separations thereof were extensively refined. The general trend was that stationary phases with large pores, shorter chain hydrocarbons (such as C4, C8 or even C3 and CN) with better end capping of the residual silica as well as the addition of chaotropic and ion pairing mobile phase additives generally resulted in better separations and sample recovery. This is primarily attributed to the extreme basicity of the histone tails and their strong tendency to interact with residual silanols. Some histone variants separate well by reversed phased methods (notably to current HT-CHCA methods the H3 variants), and methods can, to some degree, be designed toward the separation of specific variants. Overall, RP-HPLC of histones is a simple and useful first-step in histone analyses, but the capacity of RP-HPLC to separate histones is limited. For example, such approaches never separate modification states, at least on the whole protein level. RP-HPLC has many advantages, but fundamentally it is not well suited for highly basic analytes such as histone tails, and it is at these basic residues where most of the PTM activity takes place.

The approaches that might come to the mind of the experienced chromatographer to separate highly basic compounds are cation exchange chromatography or some sort of normal phase chromatography. Cation exchange chromatography has indeed been used as early as 1959 for such purposes [69]. Normal phase chromatography suffered from poor resolution and reproducibility until the relatively recent introduction of bonded normal phases. These bonded normal phases have been termed hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC). This chromatography pioneered by Andrew Alpert [70] at PolyLC has also been used very successfully to separate intact histone variants with some resolution by the degree of modification [71, 72]. As will be detailed below, HILIC separations, often at the peptide level, in conjunction with mass spectrometry approaches have been essential to many methods that thoroughly and effectively characterize combinatorial histone codes [56, 73–77]. Some of these, notably the PolyCatA-based methods, have some ion exchange character in a mixed mode with hydrophilic mechanisms. All of the above-mentioned HILIC methods, however, rely on a non-volatile mobile phase additive, such as a chaotropic agent to improve resolution, and/or salt gradients for elution of the histone forms. This makes the most effective separation not directly compatible with mass spectrometry, which is the most effective means to sequence and quantitate the separated combinatorial histone codes. Recently, we have resolved this long-standing problem in histone analysis by creating a mass spectrometry-compatible weak cation exchange-HILIC method (WCX-HILIC) [78]. We removed all non-volatile components from the mobile phase and used a pH gradient to neutralize the cation exchange character of the stationary phase. This was done in conjunction with a decreasing organic solvent gradient for elution based on purely HILIC mechanisms. In this way, we achieved very effective WCX-HILIC-based separation, which is also directly compatible with mass spectrometry.

Mass spectrometry-based readout of histone modifications

Mass spectrometry plays an essential role in any CHCA method. Particularly, electron capture dissociation (ECD) [79] and electron transfer dissociation (ETD) [80] provide gas phase fragmentation that can both preserve and detect PTMs and provide sequencing of long peptides. Although the mechanisms are not completely understood, ECD and ETD both work by transferring an unpaired low energy electron to the peptide being analyzed. This induces fragmentation along the peptide backbone with little bias as to amino acid content or modifications. Fragmentation at the N-terminal side of proline, however, is expected due to its ring structure. For comparison, the more common collision-induced dissociation imparts vibrational energy into the peptide. This tends to result in more bias to the site of fragmentation and is less effective at fragmenting longer and more highly charged peptides. Histones are very basic proteins that are highly charged when ionized and the PTMs being analyzed exist over relatively long sequences, making ETD/ECD fragmentation preferential for histone analysis.

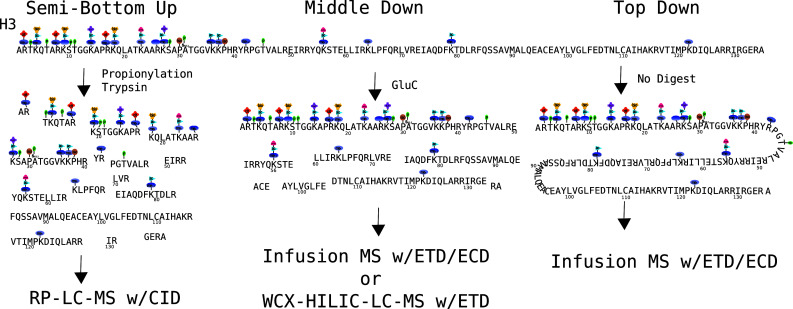

It should be noted that one complication in mass spectrometry analysis of histone PTMs is that the commonly observed modifications of trimethylation and acetylation have the same nominal mass. Mass spectrometry methods can distinguish between these in two different ways. Today, the resolution and mass accuracy of some mass spectrometers are sufficient such that these modifications can be distinguished by mass alone [81, 82]. This, however, is not always the most convenient way to achieve this, particularly when considering throughput, as such high resolution experiments often come at the cost of time or sensitivity. An alternative means of distinguishing between trimethylation and acetylation is through physical separation before detection. This novel approach is fundamental to the current procedure used in our laboratory (see below) [78]. Given a relatively pure single histone variant with many modified forms, there are fundamentally three approaches to read the information therein: bottom-up, middle-down and top-down mass spectrometry. Bottom-up mass spectrometry typically involves the use of trypsin endoprotease to digest the protein of interest to a size suitable for collision-induced dissociation. With arginine- and lysine-rich histones, these peptides are very small, difficult to analyze by any means and do not produce substantial combinatorial information. A variant on this used to generate bottom-up-like information on histones utilizes propionylation to block lysines from digestion, producing a semi-bottom-up ArgC-like digest. Top-down analysis introduces the whole protein into the gas phase, whereas middle-down analysis involves some limited enzymatic digestion of the histone into a more manageable size (see Fig. 7). Note in Fig. 7, with respect to the histone H3 example, the vast majority of combinatorial information is preserved in middle-down analysis. The semi-bottom-up approach, while effective for individual PTMs, cannot be considered a truly combinatorial method, despite showing some limited combinatorial connectivity. Thus, we will primarily focus on top-down and middle-down methods. There are advantages, disadvantages and practical considerations to both approaches as will be discussed.

Fig. 7.

The various approaches to analyzing histone H3. The semi-bottom-up approach involves an ArgC-like digest using trypsin but blocking digestion at lysines with a proprionylation reaction. The middle-down approach typically uses GluC digestion to obtain a large 50-amino acid N-terminal peptide, which contains the vast majority of known modification sites. The top-down approach analyzes the undigested protein, maintaining all connectivity, but at the cost of sensitivity, time and, most importantly, confident connectivity information. The semi-bottom-up analysis usually uses reversed phase and collision-induced dissociation mass spectrometry (RP-LC–MS). Both middle-down and top-down analyses use electron transfer dissociation (ETD) or electron capture dissociation (ECD). These samples are usually fractionated by off-line HPLC, but recently on-line methods have been used (WCX-HILIC–LC–MS), dramatically improving throughput and sensitivity

Bottom-up mass spectrometry

First, however, it should also be noted that bottom-up mass spectrometry, which involves a more extensive digestion of the histone, in some cases can provide very limited combinatorial information. Some important early examples of the combinatorial nature of the histone code were in fact shown by such methods. For example, Fischle et al. blocked lysine residues of histone H3 by propionylation and trypsin digested to achieve reproducible ArgC-like peptides. The LC-MS/MS thereof identified that the release of heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1)-alpha, -beta and -gamma from chromatin during mitosis is regulated by the simultaneously occurring combinatorial modifications H3K9me3 and H3S10ph. They showed that HP1, which normally binds the silencing mark H3K9me3, is released from chromatin during mitosis by phosphorylation of the adjacent S10 residue [29]. Also an analysis of phosphorylations on histone H1 from Tetrahymena thermophila using ion metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) found as many as three phosphorylations on a single small peptide [83]. For our purposes here, we will focus on top down and middle down since the loss of combinatorial information is too great by bottom-up methods.

Top-down mass spectrometry

In theory, top-down methods preserve the maximum combinatorial information, but currently much of this information is lost for several reasons, and generally these approaches are not currently amenable to high-throughput analysis. By preserving the maximum combinatorial PTM possibilities, the number of combinatorial histone codes quickly approaches staggering numbers. This dilutes signal essentially exponentially with the number of included modifications and also generally results in extensively mixed spectra, which in turn results in both ionization suppression and the obfuscation of which forms are actually present and in what amount. Once the problem becomes complex enough and there are enough ions to support multiple combinatorial histone codes, more than one set of possible codes usually can be used to explain the data. There have been many efforts, as detailed below, using a pure top-down approach for CHCA, usually employing some of the whole protein separations mentioned above.

Top-down mass spectrometry coupled with two-dimensional liquid chromatography was used by Pesavento et al. [84] to quantitatively analyze combinatorial modifications on histone H4 leading to the quantitative characterization of 42 uniquely modified forms containing methylations and acetylations, some of which were determined to be cell cycle-specific combinations. A top-down analysis of intact yeast histones H2A, H2B, H4 and H3 characterized over 50 distinct total histone forms [23]. Subsequent experiments using methyltransferase knockout strains revealed the co-interdependence of histone H3 acetylation with H3K4 methylation as well. ECD mass spectra for intact Tetrahymena histone H2B found 13 versions of this protein (including protein variants and their modifications) [85]. Top-down characterization of the human version of the same protein rendered evidence for the presence of seven unmodified H2B variants in addition to one monomethylated isoform [86]. A similar analysis on H2A found at least 14 forms of this protein expressed in human cells. These experiments also detected the presence of an H2A-ubiquitin-conjugated protein [87]. Multiple approaches, including a top-down analysis, were used in one study to reveal the modifications of histone H4 [88]. Lastly, top-down characterization of human histone H3 allowed for the description of histone H3.1, H3.2 and H3.3 modification site occupancy. Histone H3 was found to be mostly and pervasively post-translationally modified as less than 3% of the unmodified protein was found for all three H3 variants [89]. Again, none of these methods can be considered high throughput, as they involve both extensive off-line prefractionation and the subsequent analysis of many fractions. Progress has been made towards top-down analysis on a chromatographic time scale, including some characterization of histone H4 combinatorial forms in the process [90]. Such an approach is very appealing, but there remain technical challenges to overcome before on-line top-down LC-MS will be the most effective approach. Although not truly a top-down approach, recently Kelleher and coworkers [91] have taken an LC-FTMS profiling approach to studying histone modifications. This is rapid and effective, but significant combinatorial information is lost.

Middle-down mass spectrometry

Middle-down CHCA methods generally use an up-front whole protein separation as detailed above, followed by a targeted enzymatic digestion. In the case of H3, GluC endoprotease is generally used to obtain the first 50 amino acids of the N-terminal tail. For histone H4, typically AspN endoprotease is used to obtain the first 23 amino acids. These peptides contain the majority of modification sites and the sites that are thought, due to their close proximity and other factors, to be the most likely to operate in a combinatorial manner. The shorter but still highly charged peptides are ideal for thorough analysis by ETD or ECD sequencing analysis. However, the physical separation of these smaller, but still substantial, peptides is a significantly more tractable problem. In essence, the middle-down approach to CHCA is what currently is feasible as a thorough and reasonably high-throughput method. The challenges associated, however, are still very large.

Until very recently, middle-down methods have, similar to top-down methods, utilized primarily off-line separations followed by analysis of fractions. This was largely motivated by developments in the capacity of mass spectrometers to efficiently and rapidly fragment ions by ETD and ECD. Again, the maintenance of molecular connectivity over even these shorter peptides has only been possible for the last few years, but has until recently required large amounts of sample and minutes to hours for the analysis of a single polypeptide. With such off-line separations, the analysis of all fractions of a single sample representing one biological state could take more than 100 h of analysis time. Yet these still relatively new approaches have led the way toward more high-throughput approaches.

Pesavento et al. [92] performed middle-down analyses on histones without up-front separation and were able to achieve reasonable results on the relatively simple H4 system. Fundamentally, such an approach is prone to ambiguity particularly for certain modification states and ratios (e.g., several modified forms that contain two acetylated lysines), and they soon improved on this by fractionating with HILIC chromatography [76]. Reversed phase and PolyCAT A-based HILIC separations have been used to fractionate out the H3-(1–50) peptide from Tetrahymena into distinct acetylation states before ETD analysis on a modified Orbitrap [77]. This identified over 40 modified forms of histone H3 from this lower eukaryote. Garcia et al. identified over 150 unique modified forms of the histone H3.2-(1–50) peptide in asynchronously grown and butyrate-treated HeLa cells using off-line weak cation HILIC. The separation occurs first by separating isoforms by acetylation status (weak cation exchange) and then by a second mode of separation based on the methylation (HILIC). HILIC fractions were statically infused into an FTICR mass spectrometer, and fragmentation was induced using ECD [56].

The last requirement of HT-CHCA in combination with good on-line separation and ETD capable of operating efficiently on the chromatographic time scale has only recently been achieved. Unclear what is the last requirement? A step in this direction was taken in 2008 where Phanstiel et al. approached the problem by using reverse-phase LC-MS/MS using a custom-built ETD-capable quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometer. They deciphered 74 discrete combinatorial codes on the tail of histone H4 from human embryonic stem (ES) cells [93]. Most of the combinatorial forms, however, co-eluted with others and had to be deconvoluted by mathematical analysis, making quantitation impossible for some forms because of the limitations of such mathematical analysis. (See below for issues surrounding data analysis.) Similarly, Nicklay et al. analyzed both H3 and H4 from Xenopus laevis, but only the H4 was analyzed by middle-down methods. They also used on-line reversed phase LC-MS methods in conjunction with ETD on the H4 1–23aa tail [94]. Thus, the mass spectrometry but not the chromatographic limitations was largely solved.

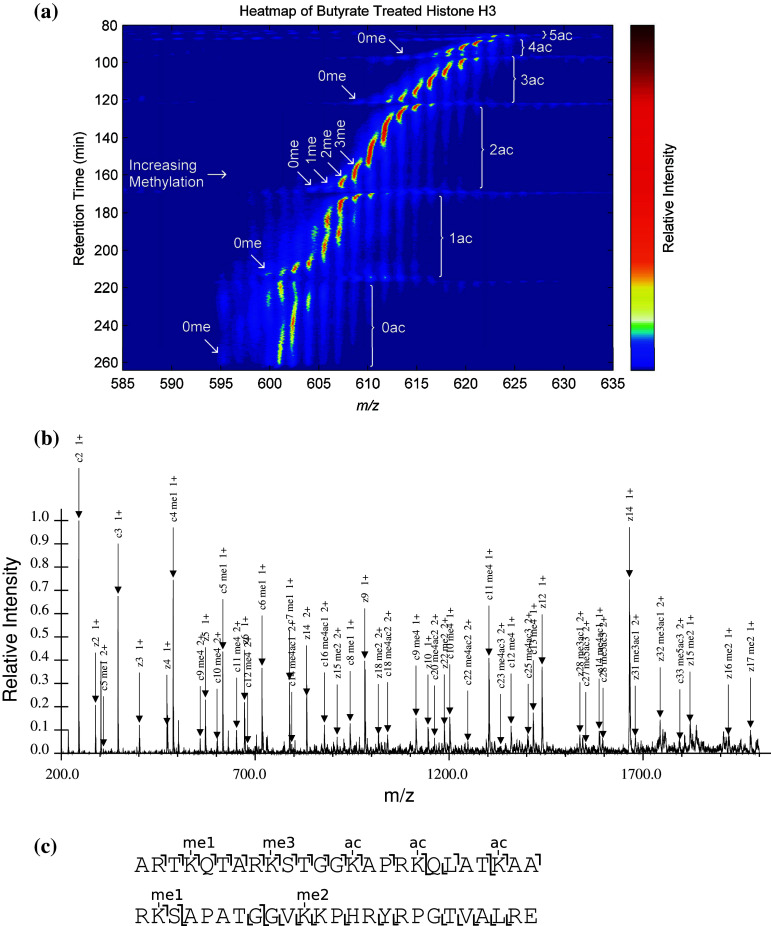

We (Young et al.) recently developed a HT-CHCA method utilizing a pH gradient to elute histone codes from a weak cation exchange hydrophilic interaction nanoflow liquid chromatography column directly into a mass spectrometer using electron transfer dissociation to identify and quantitate combinatorial histone codes (see Fig. 8). This was demonstrated on the histone H3 and histone H4 N-terminal peptide (first 50 and 23 amino acids, respectively). With this approach, we demonstrated remarkably effective, but not necessarily complete, chromatographic separation of the structural isomers. This method was used to characterize over 200 modified forms of histone H3.2 in one LC-MS/MS experiment and over 70 modified forms from histone H4 [78]. As can be seen in Fig. 8a, acetylation is the major determinant of the chromatographic separation. Of importance is that the trimethylated species that share the same nominal mass with an acetylation are well separated from the corresponding acetyl forms and thus distinguishable by retention time. This was a dramatic improvement over previous approaches that required weeks worth of work to produce similar data. There remains room for improvement in this current state of HT-CHCA, yet it is truly a high-throughput method, and the quality and confidence in the data are greater than previous lower throughput methods.

Fig. 8.

An example of a high throughput combinatorial histone code analysis. On-line pH gradient-based weak cation exchange-hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (WCX-HILIC) is used for chromatographic separation, and electron transfer dissociation (ETD) is used to sequence eluting combinatorial histone codes. a An LC-MS heatmap is shown. How PTMs effect separation are indicated. Increasing acetylation significantly decreases retention time, while methylation modulates retention time more subtly. b An example of an eluting combinatorial histone code being identified on the millisecond time scale. c The ion map corresponding to (b). Quantitation may be achieved on all of the combinatorial histone codes identified using both the precursor ion intensity and the fraction of the spectrum that each combinatorial histone code represents determined computationally for mixed spectra. In this manner, the entire complement of combinatorial histone codes may be identified and quantified relative to each other for a sample in a matter of hours

Cation exchange HILIC chromatography had been used previously, but with non-volatile buffers, and was based on an ionic strength gradient [56]. This in turn was based on previous work that showed good separation with HILIC [71, 72]. The critical step to convert this chromatography into a high-throughput on-line LC-MS method was the use of a pH gradient to take advantage of the weak cation exchange properties of the PolyCAT A stationary phase. In this manner, the cation exchange retention mechanism could be disrupted while being compatible with directly introducing the eluent into the mass spectrometer. The mass spectrometry-based sequencing, which allows the identification and quantitation of the CHCs, is commercially available and moderately priced.

Bioinformatics for reading the histone code

Although the data from HT-CHCA methods have been recently much improved, the interpretation of this data still remains a unique challenge. The tandem mass spectra that sequence, indentify and allow quantitation of CHCs are still partially mixed, at least for the more complex histones such as H3. Furthermore, the commercially available mass spectrometry analysis software is generally not well suited to deal with mixed spectra or combinatorially modified peptides.

The emergence of bottom-up mass spectrometry as a high-throughput proteomics platform around 15 years ago served as an impetus for the development of a battery of bioinformatics algorithms. These algorithms were designed to address specific problems encountered in bottom-up MS, such as (1) peptide identification using MS and/or CID tandem MS, (2) subsequent protein identification using the identified peptides and (3) peptide/protein quantification, as derived from either label-free or metabolically/chemically labeled samples. The majority of these computational methods deal with the difficult task of identifying the primary sequence of the peptide using tandem mass spectrometry data, also known as the “peptide identification problem.” These methods can range from purely de novo (i.e., methods that only use the experimental tandem mass spectrum to derive sequence information) to database approaches (i.e., methods that utilize existing databases of known protein sequences) and combinations thereof (also known as hybrid approaches).

The vast majority of these bottom-up peptide identification algorithms are inherently unable to handle a large number of PTMs due to the combinatorial explosion of the resulting search space, though several effective attempts have been made in an effort to reduce to this computational burden [95–100]. It is also important to note that simply allowing for several modifiable residues in a database search substantially increases the number of potential false-positive identifications, and users should be careful when interpreting and reporting such results. For instance, efforts to estimate this false-positive rate using reverse database searches should enforce that the same set of variable modifications is allowed to exist on the reversed protein sequences. If and when existing peptide identification approaches do become able to rigorously handle the existence of several modifications on a single peptide sequence, they must still be modified to address other imperative issues that arise in high-throughput combinatorial histone code analysis.

As previously mentioned, one critical technical issue associated with the analysis of any highly modified protein system, including the combinatorial histone code, is the existence of mixed tandem mass spectra. Even when employing the best chromatographic approaches available for on-line separation, it is still commonly observed that a limited number of isobaric modified forms (i.e., modified peptides having the same nominal mass but differing in the isomeric position of the modification sites) co-elute and thus fragment in the same tandem mass spectrum. It is a nontrivial task to not only identify which forms are present in the mixed spectrum, but to also deconvolute which peaks belong to these forms for quantitating their relative abundances. It should be noted here that all existing bottom-up peptide identification algorithms cannot currently address mixed spectra and are only able to identify the most abundant form. Furthermore, since isobaric modified forms share a significant percentage of the same theoretical ion peaks, these approaches can fail to localize a particular site of modification in the absence of supporting experimental fragment ion peaks.

Recent attempts have utilized linear regression to deconvolute the contributions of the modified forms present in mixed spectra corresponding to histone proteins [93, 101]. While linear regression is without question an excellent tool for determining the best fit (in terms of minimum error) of a model to noisy experimental data, it assumes the experimentally observed data values randomly follow a Gaussian distribution around the actual values. This inherent assumption may not be accurate for the ETD fragmentation of highly modified proteins, as the low m/z regions typically have a better S/N ratio, the middle range of the spectrum is often subject to ion peak interferences, and the intensity of the ion peaks is observed to follow an inverse parabolic distribution (e.g., the intensity of the ion peaks is greatest in the low and high m/z regions of the spectrum). However, if given an appropriate distribution that accurately reflects the deviation of the observed from the actual values, regression techniques could potentially address the problem of interpreting mixed spectra.

Another important (but often overlooked) task is to integrate the chromatographic information available from an on-line analysis into the peptide/protein identifications. With the exception of a few studies, most peptide identification methods do not incorporate the chromatography as another source of information or confidence into their predictions. Some approaches will provide higher confidence identifications for peptides assigned to multiple spectra in the same dataset, but ignore the temporal characteristics associated with a physically meaningful elution of the peptides. For instance, higher confidence identifications should be provided for a peptide that was assigned to five tandem MSs within a narrow time range (and preferentially following an approximate Gaussian distribution in precursor abundance) in contrast to another peptide that was assigned to five tandem MSs that were randomly distributed over the time interval of the experiment.

Within the context of high-throughput combinatorial histone code analysis, chromatographic information has been shown to be invaluable in correlating the modified forms as a function of their m/z and relative retention time values. For instance, it was recently shown that the m/z and retention time values for modified histone H3 proteins can be correlated with the number and position of acetylation modifications [102]. This information not only resulted in significantly higher confidence PTM identifications, but also facilitated the identification of partially interpreted tandem mass spectra due to incomplete fragmentation by inferring the modification sites in the absence of other evidence. Of equal importance is the ability to correctly average neighboring tandem MS scans in order to increase the signal-to-noise ratio and enhance the signal for low intensity ion peaks. This is particularly important for detecting lower level forms that are chromatographically buried by abundant species.

Although progress has been made towards the development of bioinformatics algorithms for the high-throughput analysis of highly modified proteins, the continued development and refinement of these approaches will be absolutely critical in the expedition of progress in this field. Thus, appropriate data analysis and informatics approaches are not just necessary for the correct and confident interpretation of HT-CHCA data, but it also serves an essential role in leveraging all of the information and inherent advantages gained by such methods.

Conclusion and future outlook

Clearly, the biological importance of combinatorial histone codes and recent advances in mass spectrometry-based high-throughput combinatorial histone code analysis should result in both a forthcoming understanding of the biology of this complex system and continued improvement in methods to achieve such data. Although still limited to laboratories with a high level of expertise, the equipment to achieve this data is now moderately priced compared to the very high-end mass spectrometer required just a couple years ago. The computational methods required still require development and are not commercially available. Indubitably, these methods will become more accessible in the next few years and open new approaches to understanding eukaryotic biology.

One of the future developments essential to understanding the biology of combinatorial histone codes is to connect them back to specific genomic locations in a manner similar to how ChIP-seq technologies are able to with single modifications. One approach to this is to try to correlate CHCA data to ChIP-seq data or even to physically spilt the sample after the ChIP and apply both DNA sequencing and HT-CHCA to the same sample. The use of ChIP in conjunction with MS was used by Loyola et al., but the ChIP was against the H3 variants rather than histone modifications, and the modification data were non-combinatorial and not extensively analyzed [103]. A more extensive use of such an approach in conjunction with HT-CHCA would clearly be very compelling. Also the use of specific DNA sequences to pull out defined sections of DNA would be very useful in understanding many aspects of how chromatin and epigenetics of individual genes function. Such technologies have been developed and used to observe the proteins associated with particular sections of chromatin. Particularly notable in this regard is the work of Dejardin et al. [104]; however, this was against telomeres, which have the distinct advantage of being long and repetitive sequences.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Princeton University, an NSF Early Faculty CAREER award, NSF grant (CBET-0941143) and a NJCCR SEED grant to B.A.G.; N.L.Y. and P.A.D. also gratefully acknowledge funding from NIH F32 NRSA postdoctoral fellowships.

References

- 1.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997;389(6648):251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prohaska SJ, Stadler PF, Krakauer DC. Innovation in gene regulation: the case of chromatin computation. J Theor Biol. 2010;265(1):27–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293(5532):1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strahl BD, Allis CD. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature. 2000;403(6765):41–45. doi: 10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128(4):693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner BM. Cellular memory and the histone code. Cell. 2002;111(3):285–291. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allis CD, Jenuwein T, Reinberg D. Overview and concepts. In: Allis CD, Jenuwein T, Reinberg D, Caparros ML, editors. Epigenetics. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 2007. pp. 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iizuka M, Smith MM. Functional consequences of histone modifications. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13(2):154–160. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(03)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma S, Kelly TK, Jones PA. Epigenetics in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(1):27–36. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suganuma T, Workman JL. Crosstalk among histone modifications. Cell. 2008;135(4):604–607. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park PJ. ChIP-seq: advantages and challenges of a maturing technology. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(10):669–680. doi: 10.1038/nrg2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barlesi F, Giaccone G, Gallegos-Ruiz MI, Loundou A, Span SW, Lefesvre P, Kruyt FA, Rodriguez JA. Global histone modifications predict prognosis of resected non small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(28):4358–4364. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elsheikh SE, Green AR, Rakha EA, Powe DG, Ahmed RA, Collins HM, Soria D, Garibaldi JM, Paish CE, Ammar AA, Grainge MJ, Ball GR, Abdelghany MK, Martinez-Pomares L, Heery DM, Ellis IO. Global histone modifications in breast cancer correlate with tumor phenotypes, prognostic factors, and patient outcome. Cancer Res. 2009;69(9):3802–3809. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seligson DB, Horvath S, McBrian MA, Mah V, Yu H, Tze S, Wang Q, Chia D, Goodglick L, Kurdistani SK. Global levels of histone modifications predict prognosis in different cancers. Am J Pathol. 2009;174(5):1619–1628. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seligson DB, Horvath S, Shi T, Yu H, Tze S, Grunstein M, Kurdistani SK. Global histone modification patterns predict risk of prostate cancer recurrence. Nature. 2005;435(7046):1262–1266. doi: 10.1038/nature03672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dion MF, Altschuler SJ, Wu LF, Rando OJ. Genomic characterization reveals a simple histone H4 acetylation code. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(15):5501–5506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500136102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu CL, Kaplan T, Kim M, Buratowski S, Schreiber SL, Friedman N, Rando OJ. Single-nucleosome mapping of histone modifications in S. cerevisiae . PLoS Biol. 2005;3(10):e328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurdistani SK, Tavazoie S, Grunstein M. Mapping global histone acetylation patterns to gene expression. Cell. 2004;117(6):721–733. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Z, Zang C, Rosenfeld JA, Schones DE, Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Peng W, Zhang MQ, Zhao K. Combinatorial patterns of histone acetylations and methylations in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2008;40(7):897–903. doi: 10.1038/ng.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, Kamal M, Huebert DJ, Cuff J, Fry B, Meissner A, Wernig M, Plath K, Jaenisch R, Wagschal A, Feil R, Schreiber SL, Lander ES. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125(2):315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greaves IK, Rangasamy D, Ridgway P, Tremethick DJ. H2A.Z contributes to the unique 3D structure of the centromere. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(2):525–530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607870104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park YS, Jin MY, Kim YJ, Yook JH, Kim BS, Jang SJ. The global histone modification pattern correlates with cancer recurrence and overall survival in gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(7):1968–1976. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9927-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang L, Smith JN, Anderson SL, Ma P, Mizzen CA, Kelleher NL. Global assessment of combinatorial post-translational modification of core histones in yeast using contemporary mass spectrometry. LYS4 trimethylation correlates with degree of acetylation on the same H3 tail. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(38):27923–27934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markaki Y, Christogianni A, Politou AS, Georgatos SD. Phosphorylation of histone H3 at Thr3 is part of a combinatorial pattern that marks and configures mitotic chromatin. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(Pt 16):2809–2819. doi: 10.1242/jcs.043810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang TJ, Yuzawa S, Suga H. Expression of histone H3 tails with combinatorial lysine modifications under the reprogrammed genetic code for the investigation on epigenetic markers. Chem Biol. 2008;15(11):1166–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirmizis A, Santos-Rosa H, Penkett CJ, Singer MA, Vermeulen M, Mann M, Bahler J, Green RD, Kouzarides T. Arginine methylation at histone H3R2 controls deposition of H3K4 trimethylation. Nature. 2007;449(7164):928–932. doi: 10.1038/nature06160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taverna SD, Ilin S, Rogers RS, Tanny JC, Lavender H, Li H, Baker L, Boyle J, Blair LP, Chait BT, Patel DJ, Aitchison JD, Tackett AJ, Allis CD. Yng1 PHD finger binding to H3 trimethylated at K4 promotes NuA3 HAT activity at K14 of H3 and transcription at a subset of targeted ORFs. Mol Cell. 2006;24(5):785–796. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hung T, Binda O, Champagne KS, Kuo AJ, Johnson K, Chang HY, Simon MD, Kutateladze TG, Gozani O. ING4 mediates crosstalk between histone H3 K4 trimethylation and H3 acetylation to attenuate cellular transformation. Mol Cell. 2009;33(2):248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fischle W, Tseng BS, Dormann HL, Ueberheide BM, Garcia BA, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Funabiki H, Allis CD. Regulation of HP1-chromatin binding by histone H3 methylation and phosphorylation. Nature. 2005;438(7071):1116–1122. doi: 10.1038/nature04219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daujat S, Zeissler U, Waldmann T, Happel N, Schneider R. HP1 binds specifically to Lys26-methylated histone H1.4, whereas simultaneous Ser27 phosphorylation blocks HP1 binding. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(45):38090–38095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500229200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garske AL, Craciun G, Denu JM. A combinatorial H4 tail library for exploring the histone code. Biochemistry. 2008;47(31):8094–8102. doi: 10.1021/bi800766k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li B, Gogol M, Carey M, Lee D, Seidel C, Workman JL. Combined action of PHD and chromo domains directs the Rpd3S HDAC to transcribed chromatin. Science. 2007;316(5827):1050–1054. doi: 10.1126/science.1139004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saksouk N, Avvakumov N, Champagne KS, Hung T, Doyon Y, Cayrou C, Paquet E, Ullah M, Landry AJ, Cote V, Yang XJ, Gozani O, Kutateladze TG, Cote J. HBO1 HAT complexes target chromatin throughout gene coding regions via multiple PHD finger interactions with histone H3 tail. Mol Cell. 2009;33(2):257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moriniere J, Rousseaux S, Steuerwald U, Soler-Lopez M, Curtet S, Vitte AL, Govin J, Gaucher J, Sadoul K, Hart DJ, Krijgsveld J, Khochbin S, Muller CW, Petosa C. Cooperative binding of two acetylation marks on a histone tail by a single bromodomain. Nature. 2009;461(7264):664–668. doi: 10.1038/nature08397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trojer P, Li G, Sims RJ, 3rd, Vaquero A, Kalakonda N, Boccuni P, Lee D, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Nimer SD, Wang YH, Reinberg D. L3MBTL1, a histone-methylation-dependent chromatin lock. Cell. 2007;129(5):915–928. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruthenburg AJ, Li H, Patel DJ, Allis CD. Multivalent engagement of chromatin modifications by linked binding modules. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(12):983–994. doi: 10.1038/nrm2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sims JK, Houston SI, Magazinnik T, Rice JC. A trans-tail histone code defined by monomethylated H4 Lys-20 and H3 Lys-9 demarcates distinct regions of silent chromatin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(18):12760–12766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513462200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campos EI, Reinberg D. Histones: annotating chromatin. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:559–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.032608.103928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Briggs SD, Xiao T, Sun ZW, Caldwell JA, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Allis CD, Strahl BD. Gene silencing: trans-histone regulatory pathway in chromatin. Nature. 2002;418(6897):498. doi: 10.1038/nature00970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee JS, Shukla A, Schneider J, Swanson SK, Washburn MP, Florens L, Bhaumik SR, Shilatifard A. Histone crosstalk between H2B monoubiquitination and H3 methylation mediated by COMPASS. Cell. 2007;131(6):1084–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du LL, Nakamura TM, Russell P. Histone modification-dependent and -independent pathways for recruitment of checkpoint protein Crb2 to double-strand breaks. Genes Dev. 2006;20(12):1583–1596. doi: 10.1101/gad.1422606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huyen Y, Zgheib O, Ditullio RA, Jr, Gorgoulis VG, Zacharatos P, Petty TJ, Sheston EA, Mellert HS, Stavridi ES, Halazonetis TD. Methylated lysine 79 of histone H3 targets 53BP1 to DNA double-strand breaks. Nature. 2004;432(7015):406–411. doi: 10.1038/nature03114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neelin JM, Connell GE. Zone electrophoresis of chicken-erythrocyte histone in starch gel. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1959;31(2):539–541. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(59)90030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panyim S, Chalkley R. High resolution acrylamide gel electrophoresis of histones. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1969;130(1):337–346. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(69)90042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Franklin SG, Zweidler A. Non-allelic variants of histones 2a, 2b and 3 in mammals. Nature. 1977;266(5599):273–275. doi: 10.1038/266273a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonner WM, West MH, Stedman JD. Two-dimensional gel analysis of histones in acid extracts of nuclei, cells, and tissues. Eur J Biochem. 1980;109(1):17–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb04762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gurley LR, London JE, Valdez JG. High-performance capillary electrophoresis of histones. J Chromatogr. 1991;559(1–2):431–443. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(91)80091-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lindner H, Helliger W, Dirschlmayer A, Jaquemar M, Puschendorf B. High-performance capillary electrophoresis of core histones and their acetylated modified derivatives. Biochem J. 1992;283(Pt 2):467–471. doi: 10.1042/bj2830467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lindner H, Helliger W, Dirschlmayer A, Talasz H, Wurm M, Sarg B, Jaquemar M, Puschendorf B. Separation of phosphorylated histone H1 variants by high-performance capillary electrophoresis. J Chromatogr. 1992;608(1–2):211–216. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(92)87126-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lindner H, Helliger W, Sarg B, Meraner C. Effect of buffer composition on the migration order and separation of histone H1 subtypes. Electrophoresis. 1995;16(4):604–610. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150160197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lindner H, Wurm M, Dirschlmayer A, Sarg B, Helliger W. Application of high-performance capillary electrophoresis to the analysis of H1 histones. Electrophoresis. 1993;14(5–6):480–485. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150140174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aguilar C, Hofte AJ, Tjaden UR, van der Greef J. Analysis of histones by on-line capillary zone electrophoresis–electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2001;926(1):57–67. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)00962-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]