Abstract

Sulindac is a non-selective inhibitor of cyclooxygenases (COX) used to treat inflammation and pain. Additionally, non-COX targets may account for the drug’s chemo-preventive efficacy against colorectal cancer and reduced gastrointestinal toxicity. Here, we demonstrate that the pharmacologically active metabolite of sulindac, sulindac sulfide (SSi), targets 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO), the key enzyme in the biosynthesis of proinflammatory leukotrienes (LTs). SSi inhibited 5-LO in ionophore A23187- and LPS/fMLP-stimulated human polymorphonuclear leukocytes (IC50 ≈ 8–10 μM). Importantly, SSi efficiently suppressed 5-LO in human whole blood at clinically relevant plasma levels (IC50 = 18.7 μM). SSi was 5-LO-selective as no inhibition of related lipoxygenases (12-LO, 15-LO) was observed. The sulindac prodrug and the other metabolite, sulindac sulfone (SSo), failed to inhibit 5-LO. Mechanistic analysis demonstrated that SSi directly suppresses 5-LO with an IC50 of 20 μM. Together, these findings may provide a novel molecular basis to explain the COX-independent pharmacological effects of sulindac under therapy.

Keywords: Cyclooxygenase, Leukotrienes, Leukocytes, NSAIDs, Off-target effect

Introduction

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most commonly used medication for the treatment of pain and inflammation. Traditional NSAIDs, such as diclofenac, indomethacin, or sulindac inhibit both cyclooxygenase (COX) isoforms, which are the key enzymes in the conversion of arachidonic acid (AA) to prostaglandins (PGs). The constitutively expressed COX-1 primarily maintains homeostasis, whereas COX-2 functions as an induced response to growth factors and cytokines [1].

Although NSAIDs share COX-1 and COX-2 as common molecular targets, each drug possesses an individual pharmacodynamic profile. These differences extend to adverse drug reactions and blood pressure increases, as well as to beneficial pharmacological actions, such as a chemopreventive activity against colorectal cancer [2] and may partly relate to COX-independent mechanisms.

Sulindac is an extensively investigated low-ulcerogenic NSAID that possesses strong anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and anti-pyretic effects. It also efficiently prevents precancerous colorectal polyps in humans by interacting with COX-independent targets [3]. Sulindac is a prodrug that is reversibly metabolized by the liver into the metabolite sulindac sulfide (SSi), which inhibits COX. Metabolism into the sulfone derivative (SSo), which does not inhibit COX, is irreversible [4]. Although the sulfide metabolite primarily imparts the chemopreventive activity [5], an anti-neoplastic efficacy against certain tumor types has also been attributed to SSo [6].

Similarly to PGs, leukotrienes (LTs) derive from AA and exert pivotal biological functions as well as pathogenic effects in inflammation, cancer, and atherosclerosis [7]. In the first step of LT biosynthesis, AA is metabolized by 5-LO to LTA4, which serves as a precursor for bioactive LTs, such as LTB4 and the cysteinyl-LTs C4, D4, and E4 [8]. In view of the combination of the exceptional pharmacological profile of sulindac and the pathophysiological effects of LTs, we investigated the possibility of an interference of LT biosynthesis by the pharmacologically active metabolite of sulindac, i.e., SSi.

Materials and methods

Reagents used for the experiments

Sulindac, SSi, SSo, BWA4C, MK-886, indomethacin, diclofenac, calcium ionophore A23187, GSH (glutathione), arachidonic acid, LPS (lipopolysaccharide), and fMLP (N-formyl- methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Munich, Germany) and Ada (adenosine desaminase) was purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, USA). Merck Frosst (Canada) kindly provided MK-591.

Isolation of human neutrophil granulocytes from venous blood

Human polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNL) were freshly isolated from leukocyte concentrates obtained from St. Markus Hospital (Frankfurt, Germany) or from the Blood Center, University Hospital, Tuebingen, Germany. In brief, venous blood was collected from fasted, adult, healthy volunteers, with consent. The subjects had no apparent inflammatory conditions and had not taken anti-inflammatory drugs for at least 10 days prior to blood collection. The blood was centrifuged at 4,000g and RT for 20 min for preparation of leukocyte concentrates. PMNL were promptly isolated by dextran sedimentation, centrifugation on Nycoprep cushions (PAA Laboratories, Linz, Austria), and hypotonic lysis of erythrocytes as described previously [9]. PMNL (7 × 106 cells ml−1; purity >96–97%) were finally resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline pH 7.4 (PBS) plus 1 mg ml−1 glucose and 1 mM CaCl2 (PGC buffer).

Expression and purification of 5-LO from Escherichia coli

5-LO was expressed in E. coli Bl21 (DE3) cells, transformed with pT3–5LO, and purification of 5-LO was performed as described previously [10]. In brief, E. coli were harvested and lysed in 50 mM triethanolamine/HCl, pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA, soybean trypsin inhibitor (60 μg/ml−1), 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 mM DTT and lysozyme (1 mg/ml), homogenized by sonication (6 × 10 s) and centrifuged at 10,000g for 15 min followed by centrifugation at 100,000g for 70 min at 4°C. The supernatant was then applied to an ATP-agarose column (Sigma A2767; Deisenhofen, Germany), and the column was eluted as described previously [11]. Partially purified 5-LO was immediately used for in vitro activity assays.

Determination of 5-LO product formation of intact cells

For determination in intact cells, 7 × 106 freshly isolated PMNL were resuspended in 1 ml PGC buffer. After pre-incubation with the test compounds or vehicle (DMSO) at 37°C for 10 min, 5-LO product formation was started by the addition of the stimuli, that is, 2.5 μM A23187, 10 μM sodium arsenite (SA), 300 mM sodium chloride (SC) together with or without AA as indicated. After 10 min at 37°C, the reaction was stopped by addition of 1 ml ice-cold methanol and 5-LO metabolites formed were extracted and analyzed by HPLC as described previously [12]. For stimulation with fMLP, cells were primed with 1 μg/ml LPS/0.2 U/ml Ada 30 min prior to the incubation with 1 μM fMLP for 5 min. Test compounds or vehicle (DMSO) were added 10 min before treatment with fMLP. The further procedure was performed as described for the other stimuli.

Determination of product formation of recombinant 5-LO

For determination of the activity of recombinant 5-LO, partially purified 5-LO (~0.5 μg producing ~800 ng 5-LO products in control) was added to 1 ml of a 5-LO reaction mix (PBS, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM ATP, 5 mM GSH). After incubation with the test compounds or vehicle (DMSO) for 15 min at 4°C, samples were pre-warmed for 30 s at 37°C and 2 mM CaCl2 and 20 μM AA were added. The reaction was stopped after 10 min by the addition of 1 ml ice-cold methanol and 5-LO products formed were analyzed by HPLC as described above.

Western blot analysis of 5-LO in subcellular fractions of PMNL

Subcellular localization of 5-LO in PMNL by cell fractionation was investigated as described previously [13]. In brief, freshly isolated PMNL (3 × 107) in 1 ml PGC buffer were pre-incubated with the compounds or vehicle (DMSO) for 15 min at 37°C. Then, 2.5 μM A23187 was added, the samples were further incubated for 5 min, and subsequently chilled on ice to stop the reaction. Nuclear and non-nuclear fractions were obtained after cell lysis by 0.1% NP-40. Aliquots of these fractions were immediately mixed with the same volume of 2 × SDS–PAGE sample loading buffer, heated for 6 min at 95°C, and analyzed for 5-LO protein by SDS–PAGE and Western blotting using the 5-LO anti-serum 1551, AK-7 (raised in rabbit, diluted 1:25) that was kindly provided by Dr. Olof Rådmark, Stockholm, Sweden.

Determination of 5-LO product synthesis and formation of 12-HHT in human whole blood

For assays in whole blood, freshly withdrawn blood was obtained by venipuncture and collected in monovettes containing 16 IE heparin/ml. Aliquots of 2 ml (A23187) or 3 ml (LPS and fMLP) were pre-incubated with the test compounds or with vehicle (DMSO) for 10 min at 37°C, as indicated, and formation of 5-LO products and of 12(S)-hydroxy-5-cis-8,10-trans-heptadecatrienoic acid (12-HHT) was either started by addition of fMLP (1 μM) following priming of blood with 1 μg/ml LPS, or by addition of A23187 (30 μM). The reaction was stopped on ice after 15 (LPS priming and stimulation with fMLP) or 10 (stimulation with A23187) min and the samples were centrifuged (600g, 10 min, 4°C). Aliquots of the resulting plasma (500 μl) were then mixed with 2 ml of methanol and 200 ng PGB1 were added as internal standard. The samples were placed at −20°C for 2 h and centrifuged again (600g, 15 min, 4°C). The supernatants were collected and diluted with 2.5 ml PBS and 75 μl 1 N HCl. Formed 5-LO metabolites and 12-HHT were extracted and analyzed by HPLC as described for intact PMNL.

Determination of COX-2 product synthesis in human whole blood

Aliquots of heparinized human whole blood (500 μl) were incubated with LPS (10 μg/ml) plus test compound or vehicle (DMSO) for 24 h at 37°C. Platelet COX-1 activity was halted by the addition of aspirin (100 μM). Plasma was separated by centrifugation at 1,000g and 4°C for 15 min and PGE2 in the plasma supernatant was analyzed by LC–MS/MS (liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry) using an API 4000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany) as described previously [14].

Determination of 12-H(P)ETE formation in human washed platelets

Freshly isolated platelets (108/ml PBS containing 1 mM CaCl2) were pre-incubated with the test compounds for 5 min at room temperature. After addition of 5 μM AA and further incubation for 5 min at 37°C, the reaction was stopped by addition of 1 ml ice-cold methanol and 12-H(P)ETE was extracted and analyzed by HPLC as described [15].

Statistics

All data are presented as mean + SEM. GraphPad Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Data were subjected to one-way ANOVA coupled with two-sided Tukey’s post test for multiple comparisons. The IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 and a sigmoid concentration–response curve-fitting model with a variable slope.

Results

Sulindac sulfide inhibits the formation of 5-LO products in isolated PMNL

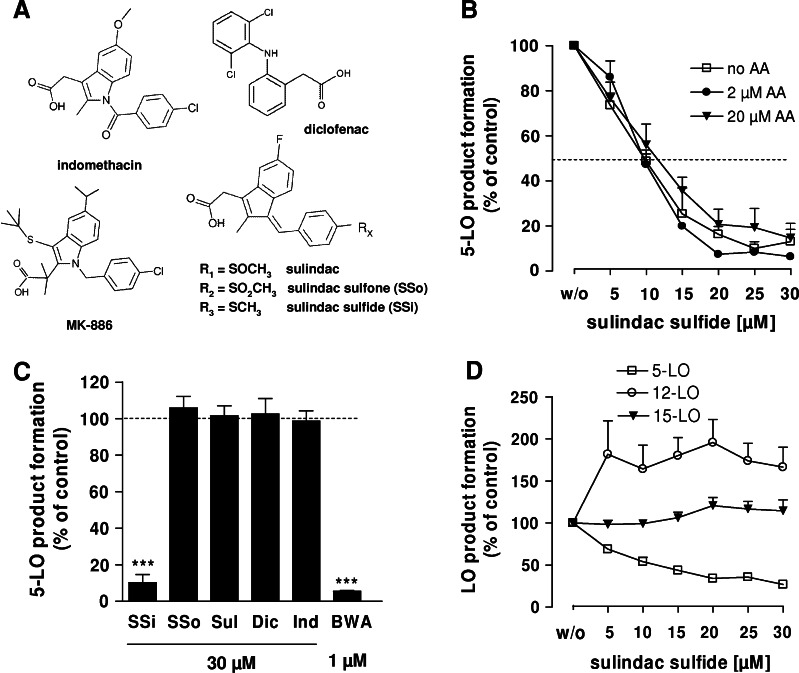

Sulindac is reversibly metabolized to SSi or irreversibly metabolized to SSo when administered orally (Fig. 1a). The effects of sulindac and its metabolites on 5-LO product (LTB4, its all-trans isomers, and 5-H(P)ETE) formation were analyzed in human PMNL, the major 5-LO product-forming cells in peripheral blood [16]. The first series of experiments utilized A23187 as a stimulus, in order to activate 5-LO directly by increase of intracellular Ca2+ to circumvent receptor signaling (e.g., receptor-mediated MAPK activation leading to phosphorylation of 5-LO). Exogenous AA (2 and 20 μM) as a supplement ensured ample substrate supply for 5-LO. Both measures were taken to exclude interference of the compounds with signaling pathways and AA release. Concentration–response studies revealed that SSi potently inhibited 5-LO product formation in A23187-stimulated PMNL in the absence as well as in the presence of exogenously added AA (2 and 20 μM), without significant differences in the potencies (IC50 = 9–10.6 μM; Fig. 1b). Furthermore, sulindac, SSo, indomethacin (a structural analog of SSi), and diclofenac (30 μM each; Fig. 1a) failed to inhibit 5-LO activity. BWA4C, a well-recognized 5-LO inhibitor, was used as control (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Effect of SSi and related compounds on LO product formation in intact PMNL and platelets. The experimental procedures were performed as described in “Materials and methods”. All results are mean + SEM comparatively to vehicle control (100%). a Chemical structures of sulindac, SSi, SSo, indomethacin, diclofenac, and MK-886. b Effect of SSi on 5-LO product formation in intact PMNL evoked by 2.5 μM A23187 in absence or presence of AA (2 or 20 μM). 5-LO product formation in untreated control was 152.9 ± 30.2 ng (no AA), 255 ± 12.3 ng (2 μM AA), and 1,181.3 ± 192 ng (20 μM AA); n ≥ 3 c 5-LO-inhibitory effect of the indicated concentrations of SSi, SSo, sulindac, diclofenac, indomethacin, and BWA4C in intact PMNL stimulated with 2.5 μM A23187 + 20 μM AA; n ≥ 3. ***p ≤ 0.001. d Effect of SSi on 5-, 12-, and 15-LO product formation. For analysis of 5-LO and 15-LO, PMNL preparations were incubated with increasing concentrations of SSi and stimulated with 40 μM AA and 2.5 μM A23187. For analysis of 12-LO, human platelets were pre-treated with SSi and incubated with 5 μM AA; n ≥ 3. Product formation in controls (100%) was 979.4 ± 139.4 ng (5-LO products), 136.9 ± 31.4 ng (15-HETE), and 844.6 ± 176.2 ng (12-HETE). BWA BWA4C, Dic diclofenac, Ind indomethacin, SSi sulindac sulfide, SSo sulindac sulfone, Sul sulindac

Since PMNL preparations (purity > 95%) contain eosinophils expressing 15-LO-1, we also analyzed the effects of SSi on the concomitant formation of 15-H(P)ETE. In contrast to 5-LO synthesis, formation of 15-H(P)ETE was hardly affected by SSi (Fig. 1d). In addition, the effect of SSi on platelet-type 12-LO was investigated. 12-H(P)ETE product formation was elicited in platelets by 5 μM AA. SSi up to 30 μM failed to suppress, but rather increased 12-H(P)ETE product formation (Fig. 1d). SSi therefore selectively inhibited cellular 5-LO, but not 12- or 15-LO.

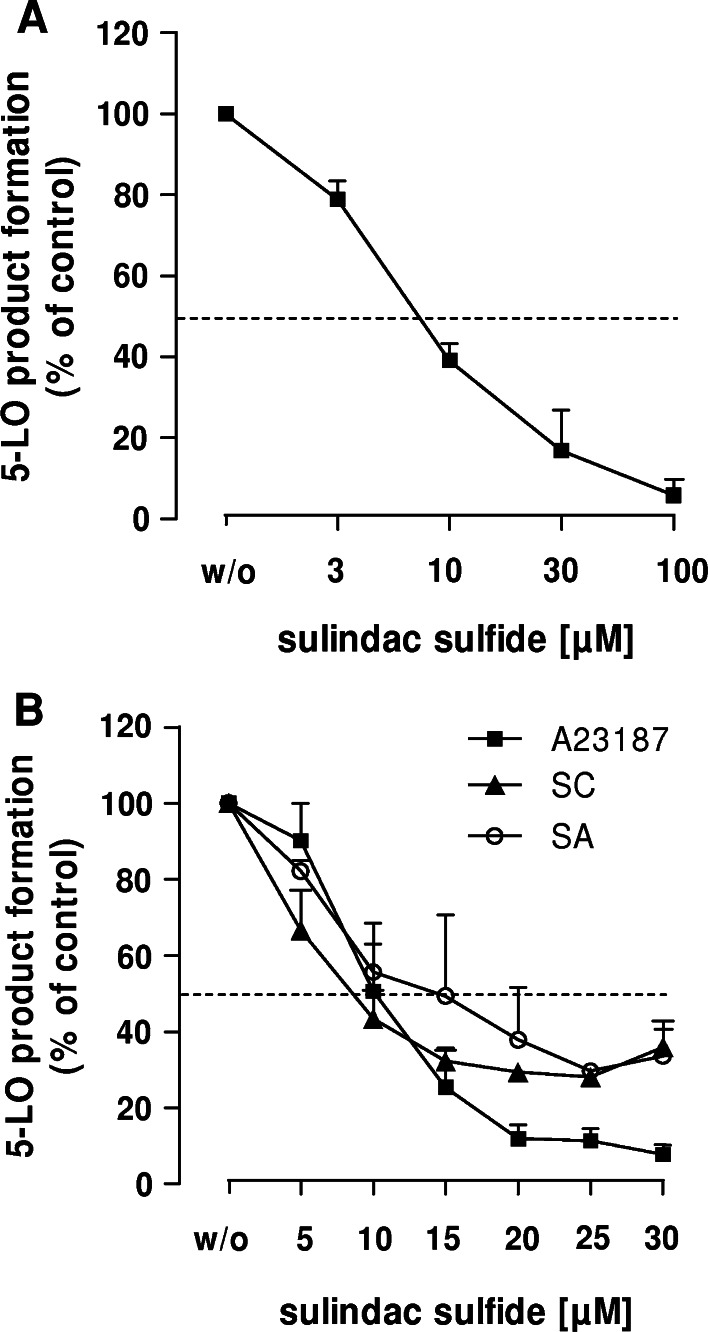

In a second series of experiments, PMNL were primed with LPS in the presence of Ada and then challenged by the natural chemoattractant fMLP. These assay conditions were designed to closely mimic pathophysiological conditions in the body [16] and therefore offer an estimate of the efficacy of 5-LO inhibitors in vivo [17]. Generation of 5-LO products in PMNL following stimulation with fMLP (after priming with LPS/Ada) was potently suppressed by SSi with an IC50 = 7.7 μM (Fig. 2a). Previous studies showed that the type of stimulus and the signal transduction pathways mediating 5-LO activation can lead to different efficacies of 5-LO inhibitors in PMNL [10]. Hence, we compared the potencies of SSi in PMNL stimulated with A23187, hyperosmotic shock (0.3 M SC) and genotoxic stress using SA [9]. All incubations contained exogenous AA (20 μM). IC50 values ranged between 8.6 and 14 μM (Fig. 2b), but in contrast to A23187-activated cells, SSi failed to completely reduce 5-LO product synthesis in PMNL challenged by cell stress, reaching a plateau where approximately 30% 5-LO activity still remained.

Fig. 2.

Effect of SSi on 5-LO product formation of intact PMNL triggered by different stimuli. The experimental procedures were performed as described in “Materials and methods”. All results are mean + SEM comparatively to vehicle control (100%). a Effect of SSi in intact PMNL stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS/Ada 0.2 U/ml/1 μM fMLP; n ≥ 3. 5-LO product formation in untreated control was 10.2 ng/107 cells. b Effect of SSi in intact PMNL stimulated with SA, SC and A23187. Cells were preincubated with SSi at the indicated concentrations for 15 min at 37°C. SA (10 μM) and SC (300 mM) were added 3 min prior to the addition of 20 μM AA, ionophore A23187 (2.5 μM) was added together with 20 μM AA; n = 3. 5-LO product formation in controls (100%) was 1,143.5 ± 74.7 ng (A23187), 361.1 ± 13.2 ng (SC), and 313.4 ± 86.8 ng (SA). SA Sodium arsenite, SC sodium chloride

SSi directly inhibits the activity of 5-LO in a cell-free assay

We next investigated whether SSi directly interferes with the catalytic activity of 5-LO. Recombinant human 5-LO, expressed in E. coli and purified by ATP-affinity chromatography, was pre-incubated with SSi, and 20 μM AA was added as substrate. Indomethacin and BWA4C were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. SSi significantly inhibited 5-LO product formation with an IC50 = 20 μM (Fig. 3a). Incubation with SSo led to a moderate but non-significant reduction of 5-LO activity. Treatment with sulindac showed no suppressive effects. These data demonstrate that SSi is a direct inhibitor of purified 5-LO, although with a somewhat lower potency compared with intact PMNL (IC50 = 7.7–14 μM). Also, in contrast to BWA4C (Fig. 3b), SSi did not entirely reduce 5-LO activity in the cell-free assay and about 30% of the activity remained at 50 μM SSi.

Fig. 3.

Effect of SSi and control agents on recombinant 5-LO product formation. The experimental procedures were performed as described in “Materials and methods”. All results are mean + SEM comparatively to vehicle control (100%). a Inhibition of partially purified human recombinant 5-LO by SSi compared to sulindac and SSo; n = 4. b Effect of SSi, SSo, sulindac, indomethacin and BWA4C at the concentrations indicated on recombinant 5-LO activity. 5-LO product formation in controls (100%) was 774.3 ± 118 ng; n ≥ 3. ***p ≤ 0.001. BWA BWA4C, Ind indomethacin, SSi sulindac sulfide, SSo sulindac sulfone, Sul sulindac

Sulindac sulfide suppresses 5-LO translocation and inhibits 5-LO product synthesis in an additive manner with the FLAP inhibitor MK-886

Since SSi was more effective in the context of intact PMNL than purified recombinant 5-LO, the inhibitor may affect additional 5-LO stimulatory mechanisms in intact cells, such as FLAP (5-lipoxygenase-activating protein). In fact, sulindac exhibits structural similarity to the FLAP inhibitor MK-886 (Fig. 1a). FLAP inhibitors share the ability to reverse agonist-induced translocation of 5-LO from the cytosol to the nuclear envelope in PMNL [18]. SSi (10–100 μM), but not SSo or Sul, partially reversed 5-LO redistribution from the cytosol to the nucleus in PMNL evoked by A23187 with an efficacy comparable to MK-886 (100 nM). As observed in previous experiments [19], the 5-LO inhibitor BWA4C did not affect A23187-induced 5-LO redistribution (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effect of SSi and other control agents on A23187-induced subcellular redistribution of 5-LO in intact PMNL. Cells were preincubated with the compounds for 15 min at 37°C, A23187 (2.5 μM) was added and nuclear and non-nuclear fractions were prepared by mild detergent (0.1% NP-40) lysis and analyzed for 5-LO expression using western blot as described in “Materials and methods”. A representative out of three independent experiments is shown. BW BWA4C, MK MK-886, non-nuc non-nuclear, nuc nuclear, SSi sulindac sulfide, SSo sulindac sulfone, Sul sulindac

To gain further understanding of the inhibitory mechanism of SSi, its ability to suppress cellular 5-LO product formation in an additive manner with MK-886 was investigated. PMNL were incubated with 5 μM MK-886 and subsequently stimulated with a mixture of A23187 and 40 μM AA. In the presence of ample exogenous AA (40 μM), the effectiveness of FLAP inhibitors is typically reduced [20] and even high concentrations of MK-886 (5 μM) failed to completely inhibit 5-LO product formation, and approx. 45% 5-LO activity still remained (Fig. 5). This basal activity is considered a FLAP-independent conversion of AA by 5-LO. In line, the failure of co-incubation of MK-886 and the FLAP inhibitor MK-0591 (IC50 = 3.1 nM [21]) to further reduce 5-LO product formation demonstrated this independence. By contrast, co-incubation of SSi (≥10 μM) together with MK-886 further suppressed 5-LO product synthesis suggesting that SSi has molecular targets other than FLAP. Co-incubation of MK-886 with zileuton, a well-known direct 5-LO inhibitor, also reduced activity to a near zero level (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effects of SSi and related compounds on A23187-induced 5-LO product formation in PMNL in presence of MK-886. Cells were preincubated with the compounds and 5 μM MK-886 for 10 min and the reaction was started by addition of 40 μM AA and 2.5 μM A23187. 5-LO product formation was assayed as described in “Materials and methods” and expressed relatively to vehicle control (100%). Results are mean + SEM; n = 3–6. Total 5-LO product formation in the control (100%) was 717 + 100.2 ng. ***p ≤ 0.001

SSi inhibits the formation of 5-LO products in human whole blood

Several inhibitors of LT biosynthesis have demonstrated high potency in isolated leukocytes but failed to efficiently interfere with 5-LO product formation in whole blood, due to plasma protein binding or to competition with other molecules, such as fatty acids [22]. Thus, the ability of a given compound to suppress LT formation in the whole blood assay may provide some perspective of its efficacy in vivo. SSi was therefore added to venous blood from healthy volunteers at concentrations achieved under standard oral therapy with sulindac (up to 40 μM [4]). After 10 min, the blood was either pre-incubated with LPS for 30 min and then stimulated with 1 μM fMLP or stimulated with A23187 alone. The formation of 5-LO products was concentration-dependently inhibited by SSi with IC50 values of 18.7 (fMLP) and 41.4 μM (A23187) (Fig. 6a). Both sulindac and SSo failed to significantly inhibit 5-LO product formation at concentrations up to 100 μM, whereas the 5-LO inhibitor BWA4C (3 μM; control) did suppress 5-LO, as expected (Fig. 6b). Furthermore, the formation of 12-H(P)ETE in the same samples of A23187-challenged blood was only moderately inhibited (34.5 ± 14% at 100 μM SSi, data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Effect of SSi on 5-LO product formation triggered by different stimuli in human whole blood. The experimental procedures were performed as described in “Materials and methods”. All results are mean + SEM comparatively to vehicle control (100%). a Effect of SSi on 5-LO product formation in human venous whole blood stimulated with A23187 (30 μM) or the combination of LPS 1 μg/ml and 1 μM fMLP; n ≥ 3. 5-LO product formation in untreated plasma was 234.1 ng/ml (A23187) and 59.2 ng/ml (LPS/fMLP). b Inhibitory effect of SSi, SSo, sulindac and BWA4C on 5-LO product formation in human whole blood; n ≥ 3. ***p ≤ 0.001, *p ≤ 0.05. BWA BWA4C, SSi sulindac sulfide, SSo sulindac sulfone, Sul sulindac

In order to compare the inhibiting potency of SSi towards 5-LO and COX enzymes, human whole blood was incubated with SSi, stimulated with LPS for 24 h and analyzed for prostanoids by LC–MS/MS. 12-HHT (mainly formed via the COX-1 pathway) and PGE2 synthesis (COX-2-derived) were effectively suppressed by SSi with IC50 values of 3 and 3.9 μM, respectively (Fig. 7a). The IC50 value for 5-LO product formation was 18.7 μM. In addition, COX product formation was not or only moderately inhibited by sulindac and SSo, an observation which is in line with the reported lack of inhibition of 5-LO by these molecules (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7.

Effect of sulindac, SSo and SSi on eicosanoid formation in human whole blood. The experimental procedures were performed as described in “Materials and methods”. All results are mean + SEM comparatively to vehicle control (100%). a Effect of SSi on the formation of COX-2-derived PGE2, COX-1-derived 12-HHT and 5-LO products in human venous whole blood; n ≥ 3. Eicosanoid formation in control plasma (100%) was 123.2 ng/ml (12-HHT), 59.2 ng/ml (5-LO products), and 32.76 ng/ml (COX-2 derived PGE2). b Comparison of inhibition of 12-HHT and PGE2 synthesis by SSi, SSo, and sulindac in human whole blood; n ≥ 3. ***p ≤ 0.001, *p ≤ 0.05. SSi Sulindac sulfide; SSo sulindac sulfone, Sul sulindac

Discussion

Sulindac is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug that also possesses analgesic, anti-pyretic, and chemopreventive activities. However, its molecular mode of action is only partly understood and may involve mechanisms outside suppression of COX enzymes. In the present study, we demonstrate that clinically relevant concentrations of SSi suppress 5-LO product synthesis in different cellular assays including human isolated PMNL, triggered not only by the physiological stimuli LPS/fMLP but also by A23187 or by cell stress, as well as in LPS/fMLP- and A23187-stimulated human whole blood.

5-LO is a tightly controlled enzyme with multiple regulatory mechanisms. Suppression of cellular product formation by an inhibitor could be caused by interaction at any of the multiple regulatory nodes. Hence, in addition to direct inhibition of 5-LO, cellular components or mechanisms, such as cPLA2, FLAP, MAPKs, and Ca2+ mobilization, interaction with coactosin-like protein and nuclear membrane association modulate 5-LO activity [23] and thus represent potential targets for SSi. SSi inhibited 5-LO product synthesis in PMNL equipotently regardless of whether AA was provided from endogenous sources via cPLA2 or exogenously, excluding interference of SSi with AA supply. However, inhibition of FLAP remains an alternative mechanism because (1) SSi was more potent against intact cells than purified 5-LO, (2) SSi exhibits structural similarity to the FLAP inhibitor MK-886, and (3) SSi suppressed the translocation of 5-LO in PMNL from the cytosol to the nuclear envelope, an established feature of FLAP inhibitors [18]. However, when FLAP was efficiently blocked by MK-886, SSi still inhibited (FLAP-independently) 5-LO product formation in intact PMNL. SSi may also suppress cellular 5-LO product synthesis by blocking the activation of MAPK, which phosphorylate and thereby stimulate 5-LO [23]. Interference with MAPK signaling by SSi is unlikely, however, since PMNL activation with the Ca2+-ionophore A23187 essentially circumvents receptor-coupled signaling and thus causes MAPK/phosphorylation-independent 5-LO activation [9]. On the other hand, SSi was most potent against 5-LO when product synthesis was induced by receptor-coupled pathways (using fMLP and/or LPS) mediated by MAPKs. Hence, under these conditions, an interference of the drug with the downstream receptor signaling pathways or the release of AA cannot be excluded. Notably, strong radical scavenging activities against various reactive oxygen species have been reported for SSi [24, 25], which may contribute to the drug’s anti-inflammatory activity. Considering that the 5-LO enzyme activity in intact cells as well as in cell-free systems shows distinctive redox dependency [26, 27], possible radical scavenging actions may therefore contribute to inhibition of 5-LO by SSi. Collectively, the present data suggest that SSi suppresses cellular 5-LO product formation via direct inhibition of 5-LO, with the possible contribution of additional mechanisms, such as inhibition of 5-LO translocation or radical scavenging. The hypothesis of a direct interaction of SSi with human 5-LO is further supported by previous findings of Piazza et al. [28], who observed inhibition of 5-LO from rat by SSi at concentrations similar to those used in the present study.

Numerous COX-independent molecular mechanisms of SSi have been observed in vitro, which may explain the drug’s peculiar and beneficial pharmacological profile. Inhibition of the NF-κB activation by 200 μM SSi, disruption of PPAR-δ signaling by 100 μM SSi, upregulation of 15-LOX-1 expression in colon cancer cells at 150 μM SSi or disturbance of the Ras-Raf-1-kinase interaction by SSi (10–50 μM) represent notable examples, but that mostly require concentrations >100 μM [29]. The in vivo relevance of these mechanisms is debated because SSi plasma concentrations >100 μM are not achieved in humans [29]. After ingestion of 400 mg (the recommended dose for treatment of arthritis), plasma drug concentrations reach a maximum of 38.6 μM, depending on the dosing procedure [4]. Notably, inhibition of cellular 5-LO product synthesis occurred at lower SSi concentrations with an IC50 ≈ 8–10 μM. This value is similar to IC50 values of SSi for COX-2 (11–14 μM) in transfected COS-1 cells [30], and the potency of SSi to suppress COX-2 (IC50 ≈ 4 μM) in whole blood was verified. Accordingly, 5-LO is a SSi target with almost equivalent susceptibility as COX-2 supported by our whole blood data, where SSi suppressed the LPS-induced 5-LO product formation with an IC50 of 18.7 μM closely to the published IC50 values for COX-2 (10.43 μM) [31]. The inhibition data in conjunction with the pharmacokinetic data suggest that standard dosage regimes of sulindac could reduce 5-LO product formation by more than 50%. Notably, pharmacokinetic studies demonstrated a prominent accumulation of SSi in colonic epithelial cells raising the possibility of still even greater 5-LO suppression in these tissues [32].

The literature provides indirect evidence supporting the hypothesis of inhibition of 5-LO by SSi in humans. For example, SSi displays strong chemopreventive activities against colorectal cancer, which may be only partly attributed to inhibition of PG synthesis [33]. Moreover, 5-LO products participate in crucial tumor development events, and pharmacological inhibition of 5-LO attenuates the growth of adenomatous colonic polyps in animals [34] and potently induces antiproliferation of cultured tumor cells [35]. Sulindac is classified as a low-ulcerogenic NSAID that causes markedly less gastrointestinal toxicity as compared to related unselective COX inhibitors, such as diclofenac, indomethacin, or naproxen [36]. In this regard, it was shown that increased LTC4 production in gastrointestinal tissues was a determinant for NSAID-induced ulcerogenicity, and concomitant application of a 5-LO inhibitor abolished the indomethacin-induced gastrotoxicity in pigs [37]. Thus, the favorable gastrointestinal profile of sulindac may also relate to its 5-LO-inhibitory activity. In addition, the superior efficacy of SSi against acute gout [38] may be associated with the drug’s 5-LO suppressive activity since urate crystals stimulate the release of LTs from PMNL [39] and may thereby contribute to the pathogenesis of the inflammatory reaction.

Considerable efforts have been made in order to develop safe and efficient 5-LO inhibitors. However, many compounds failed under in vivo conditions either due to adverse effects (interference with other biological processes or production of reactive radicals) [40] or a loss of efficacy due to increased oxidative state and/or phosphorylation of 5-LO in inflamed tissues [41]. Currently, according to our data, sulindac represents the first functional COX/5-LO inhibitor on the market with a proven 5-LO suppressive efficacy in whole blood at clinically relevant concentrations and a favorable tolerability in humans. Elucidation of the binding mode of SSi to 5-LO is of high interest and warrants investigation, from which may emerge high affinity, selective, and safe inhibitors of 5-LO with in vivo efficacy.

In conclusion, we show that the pharmacologically active metabolite of sulindac, SSi, suppresses 5-LO product synthesis in leukocytes and in human whole blood at clinically relevant concentrations through direct interference with 5-LO activity. Suppression of 5-LO product formation may contribute to the pharmacodynamic profile of sulindac in animals and humans. Clinical studies that address the effects of sulindac on LT biosynthesis in patients at standard dosage regimes for prolonged periods would be a helpful expansion of the pharmacological actions of this drug.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the “Landes Offensive zur Entwicklung Wissenschaftlich Ökonomischer Exzellenz” (LOEWE), Lipid Signaling Forschungszentrum Frankfurt (LiFF) and the German Excellence Cluster “Cardio-Pulmonary System” (ECCPS). The authors thank Dr. Wesely Mcginnstraub, California, USA, for the linguistic revision of the manuscript. The authors declare no conflicting financial interests. C.P. received a Carl Zeiss stipend.

Abbreviations

- AA

Arachidonic acid

- Ada

Adenosine deaminase

- COX

Cyclooxygenase

- cPLA2-alpha

Cytosolic phospholipase A2-alpha

- FLAP

5-Lipoxygenase-activating protein

- fMLP

N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine

- 5-HETE

5(S)-hydroxy-8,11,14-cis-6-trans-eicosa-tetraenoic acid

- 12-HETE

12(S)-hydroxy-5,8-cis-10-trans-14-cis-eicosatetraenoic acid

- 15-HETE

15(S)-hydroxy-5,8,11-cis-13-trans-eicosatetraenoic acid

- 12-HHT

12(S)-hydroxy-5-cis-8,10-trans-heptadecatrienoic acid

- LC–MS/MS

Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry

- 5-LO

5-Lipoxygenase

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- LT

Leukotriene

- NSAID

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- PGE2

Prostaglandin E2

- SA

Sodium arsenite

- SC

Sodium chloride

- SSi

Sulindac sulfide

- SSo

Sulindac sulfone

- Sul

Sulindac

Footnotes

S. D. Steinbrink and C. Pergola contributed equally.

References

- 1.Parente L, Perretti M. Advances in the pathophysiology of constitutive and inducible cyclooxygenases: two enzymes in the spotlight. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65:153–159. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(02)01422-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grosch S, Maier TJ, Schiffmann S, Geisslinger G. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)-independent anticarcinogenic effects of selective COX-2 inhibitors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:736–747. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haanen C. Sulindac and its derivatives: a novel class of anticancer agents. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2001;2:677–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies NM, Watson MS. Clinical pharmacokinetics of sulindac. A dynamic old drug. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;32:437–459. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199732060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams CS, Goldman AP, Sheng H, Morrow JD, DuBois RN. Sulindac sulfide, but not sulindac sulfone, inhibits colorectal cancer growth. Neoplasia. 1999;1:170–176. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goluboff ET. Exisulind, a selective apoptotic antineoplastic drug. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2001;10:1875–1882. doi: 10.1517/13543784.10.10.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science. 2001;294:1871–1875. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werz O, Steinhilber D. Therapeutic options for 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;112:701–718. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Werz O, Burkert E, Samuelsson B, Radmark O, Steinhilber D. Activation of 5-lipoxygenase by cell stress is calcium independent in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Blood. 2002;99:1044–1052. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.3.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer L, Szellas D, Radmark O, Steinhilber D, Werz O. Phosphorylation- and stimulus-dependent inhibition of cellular 5-lipoxygenase activity by nonredox-type inhibitors. FASEB J. 2003;17:949–951. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0205com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brungs M, Radmark O, Samuelsson B, Steinhilber D. Sequential induction of 5-lipoxygenase gene expression and activity in Mono Mac 6 cells by transforming growth factor beta and 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:107–111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Werz O, Steinhilber D. Selenium-dependent peroxidases suppress 5-lipoxygenase activity in B-lymphocytes and immature myeloid cells. The presence of peroxidase-insensitive 5-lipoxygenase activity in differentiated myeloid cells. Eur J Biochem. 1996;242:90–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0090r.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Werz O, Klemm J, Samuelsson B, Radmark O. Phorbol ester up-regulates capacities for nuclear translocation and phosphorylation of 5-lipoxygenase in Mono Mac 6 cells and human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Blood. 2001;97:2487–2495. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.8.2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maier TJ, Tausch L, Hoernig M, Coste O, Schmidt R, Angioni C, Metzner J, Groesch S, Pergola C, Steinhilber D, Werz O, Geisslinger G. Celecoxib inhibits 5-lipoxygenase. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;76:862–872. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albert D, Zundorf I, Dingermann T, Muller WE, Steinhilber D, Werz O. Hyperforin is a dual inhibitor of cyclooxygenase-1 and 5-lipoxygenase. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;64:1767–1775. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(02)01387-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Surette ME, Palmantier R, Gosselin J, Borgeat P. Lipopolysaccharides prime whole human blood and isolated neutrophils for the increased synthesis of 5-lipoxygenase products by enhancing arachidonic acid availability: involvement of the CD14 antigen. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1347–1355. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.4.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siemoneit U, Pergola C, Jazzar B, Northoff H, Skarke C, Jauch J, Werz O. On the interference of boswellic acids with 5-lipoxygenase: mechanistic studies in vitro and pharmacological relevance. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;606:246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rouzer CA, Ford-Hutchinson AW, Morton HE, Gillard JW. MK886, a potent and specific leukotriene biosynthesis inhibitor blocks and reverses the membrane association of 5-lipoxygenase in ionophore-challenged leukocytes. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1436–1442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feißt C, Pergola C, Rakonjac M, Rossi A, Koeberle A, Dodt G, Hoffmann M, Hoernig C, Fischer L, Steinhilber D, Franke L, Schneider G, Radmark O, Sautebin L, Werz O. Hyperforin is a novel type of 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor with high efficacy in vivo. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:2759–2771. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0078-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer L, Hornig M, Pergola C, Meindl N, Franke L, Tanrikulu Y, Dodt G, Schneider G, Steinhilber D, Werz O. The molecular mechanism of the inhibition by licofelone of the biosynthesis of 5-lipoxygenase products. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152:471–480. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brideau C, Chan C, Charleson S, Denis D, Evans JF, Ford-Hutchinson AW, Fortin R, Gillard JW, Guay J, Guevremont D, et al. Pharmacology of MK-0591 (3-[1-(4-chlorobenzyl)-3-(t-butylthio)-5-(quinolin-2-yl-methoxy)- indol-2-yl]-2, 2-dimethyl propanoic acid), a potent, orally active leukotriene biosynthesis inhibitor. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1992;70:799–807. doi: 10.1139/y92-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Werz O. 5-lipoxygenase: cellular biology and molecular pharmacology. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2002;1:23–44. doi: 10.2174/1568010023344959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radmark O, Werz O, Steinhilber D, Samuelsson B. 5-Lipoxygenase: regulation of expression and enzyme activity. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:332–341. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costa D, Gomes A, Reis S, Lima JL, Fernandes E. Hydrogen peroxide scavenging activity by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Life Sci. 2005;76:2841–2848. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santos F, Teixeira L, Lucio M, Ferreira H, Gaspar D, Lima JL, Reis S. Interactions of sulindac and its metabolites with phospholipid membranes: an explanation for the peroxidation protective effect of the bioactive metabolite. Free Radic Res. 2008;42:639–650. doi: 10.1080/10715760802270326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egan RW, Gale PH. Inhibition of mammalian 5-lipoxygenase by aromatic disulfides. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:11554–11559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riendeau D, Denis D, Choo LY, Nathaniel DJ. Stimulation of 5-lipoxygenase activity under conditions which promote lipid peroxidation. Biochem J. 1989;263:565–572. doi: 10.1042/bj2630565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piazza GA, Alberts DS, Hixson LJ, Paranka NS, Li H, Finn T, Bogert C, Guillen JM, Brendel K, Gross PH, Sperl G, Ritchie J, Burt RW, Ellsworth L, Ahnen DJ, Pamukcu R. Sulindac sulfone inhibits azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis in rats without reducing prostaglandin levels. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2909–2915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soh JW, Weinstein IB. Role of COX-independent targets of NSAIDs and related compounds in cancer prevention and treatment. Prog Exp Tumor Res. 2003;37:261–285. doi: 10.1159/000071377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meade EA, Smith WL, DeWitt DL. Differential inhibition of prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase (cyclooxygenase) isozymes by aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6610–6614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oshima M, Murai N, Kargman S, Arguello M, Luk P, Kwong E, Taketo MM, Evans JF. Chemoprevention of intestinal polyposis in the Apcdelta716 mouse by rofecoxib, a specific cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1733–1740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duggan DE, Hooke KF, Hwang SS. Kinetics of the tissue distributions of sulindac and metabolites. Relevance to sites and rates of bioactivation. Drug Metab Dispos. 1980;8:241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huls G, Koornstra JJ, Kleibeuker JH. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and molecular carcinogenesis of colorectal carcinomas. Lancet. 2003;362:230–232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13915-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melstrom LG, Bentrem DJ, Salabat MR, Kennedy TJ, Ding XZ, Strouch M, Rao SM, Witt RC, Ternent CA, Talamonti MS, Bell RH, Adrian TA. Overexpression of 5-lipoxygenase in colon polyps and cancer and the effect of 5-LOX inhibitors in vitro and in a murine model. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6525–6530. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romano M, Claria J. Cyclooxygenase-2 and 5-lipoxygenase converging functions on cell proliferation and tumor angiogenesis: implications for cancer therapy. FASEB J. 2003;17:1986–1995. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0053rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rainsford KD. The comparative gastric ulcerogenic activities of non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs. Agents Actions. 1977;7:573–577. doi: 10.1007/BF02111132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rainsford KD. Leukotrienes in the pathogenesis of NSAID-induced gastric and intestinal mucosal damage. Agents Actions. 1993;39(Spec No):C24–C26. doi: 10.1007/BF01972709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cronstein BN, Terkeltaub R. The inflammatory process of gout and its treatment. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(Suppl 1):S3. doi: 10.1186/ar1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serhan CN, Lundberg U, Weissmann G, Samuelsson B. Formation of leukotrienes and hydroxy acids by human neutrophils and platelets exposed to monosodium urate. Prostaglandins. 1984;27:563–581. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(84)90092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ford-Hutchinson AW, Gresser M, Young RN. 5-Lipoxygenase. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:383–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Werz O, Steinhilber D. Development of 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors—lessons from cellular enzyme regulation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;70:327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]