Abstract

Neuropathic pain is a very complex disease, involving several molecular pathways. Current available drugs are usually not acting on the several mechanisms underlying the generation and propagation of pain. We used spared nerve injury model of neuropathic pain to assess the possible use of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) as anti-neuropathic tool. Human MSCs were transplanted in the mouse lateral cerebral ventricle. Stem cells injection was performed 4 days after sciatic nerve surgery. Neuropathic mice were monitored 7, 10, 14, 17, and 21 days after surgery. hMSCs were able to reduce pain-like behaviors, such as mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia, once transplanted in cerebral ventricle. Anti-nociceptive effect was detectable from day 10 after surgery (6 days post cell injection). Human MSCs reduced the mRNA levels of the pro-inflammatory interleukin IL-1β mouse gene, as well as the neural β-galactosidase over-activation in prefrontal cortex of SNI mice. Transplanted hMSCs were able to reduce astrocytic and microglial cell activation.

Keywords: Neuropathic pain, Human mesenchymal stem cells, Stem cell transplantation, Regenerative medicine

Introduction

Neuropathic pain is defined as pain initiated or caused by a primary lesion or dysfunction in the nervous system [1, 2], and several clinical symptoms are associated with it [3]. Due to its very complex nature, neuropathic pain does not respond to traditional analgesics, such as anti-inflammatories and some opiates. Currently, there are no drugs for the neuropathic pain treatment acting in a complete and definitive way. Neuropathic pain remains a pressing clinical problem, despite the therapeutic strategies and devices developed so far [4, 5].

Newer molecular studies support the idea that neuropathic pain is a complete disease and not only the result of another syndrome or injury. Changes in DNA expression in the neuropathic pain syndrome have been observed [6, 7]. In addition, neuropathic pain is associated with neuronal-tissue damage [8].

Stem cells hold a great potential for the regeneration of damaged tissues. They have shown capacity in limiting neuronal damage in a wide variety of experimental neurologic injuries, including Parkinson’s disease, stroke, multiple sclerosis, traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injury, and peripheral nerve damage [9–11]. As a nervous system yet incurable disease, neuropathic pain may also potentially be a candidate for stem cell therapy [12].

Two critical challenges in developing cell-transplantation therapies for injured or diseased tissues are to identify optimal cells and harmful side effects. Among the stem cell population, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), or bone marrow stromal cells, have probably the best potential for good results in pain-care research. These cells are a population of progenitor cells of mesodermal origin found in the bone marrow of adults, giving rise to muscle cells, fat, vascular and urogenital systems, and to connective tissues throughout the body [13–15]. MSCs show a high expansion potential, genetic stability, and stable phenotype, can be easily collected and shipped from the laboratory to the bedside, and are compatible with different delivery methods and formulations [16]. In addition, MSCs have two other extraordinary characteristics: they are able to migrate to sites of tissue injury and have strong immunosuppressive properties that can be exploited for successful autologous as well as heterologous transplantations without requiring pharmacological immunosuppression [17, 18].

Besides, MSCs are capable of differentiating into neurons and astrocytes in vitro and in vivo [19]. Recently, MSC injection has shown good results for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis treatment in human [20]. They are able to improve neurological deficits and to promote neuronal networks with functional synaptic transmission when transplanted into animal models of neurological disorders [21].

Mesenchymal stem cells have been observed to migrate to the injured tissues and mediate functional recovery following brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerve lesions. In addition, MSCs could modulate pain generation after sciatic nerve constriction [22], although the underlying mechanisms by which MSCs exert their actions on pain behavior is still to be clarified.

In the present study, we have used spared nerve injury (SNI) model of neuropathic pain to investigate in the mouse if transplantation of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) in the cerebral ventricle was able to decrease pain-like behaviors and to interfere with molecular mechanisms underlying pain development and maintenance.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male C57BL/6 N mice (35–40 g) were housed three per cage under controlled illumination (12:12 h; light:dark cycle; light on 0600 hours) and environmental conditions (room temperature 20–22°C, humidity 55–60%) for at least 1 week before the commencement of experiments. Mouse chow and tap water were available ad libitum. The experimental procedures were approved by the Ethic Committee of the Second University of Naples. Animal care was in compliance with the IASP and European Community (E.C. L358/1 18/12/86) guidelines on the use and protection of animals in experimental research. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to reduce the number of animals used. Behavioral testing was performed before surgery to establish a baseline for comparison with post-surgical values. Mononeuropathy was induced according to the method of Bourquin and Decosterd [23]. Mice were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg i.p.). The right hindlimb was immobilized in a lateral position and slightly elevated. Incision was made at mid-thigh level using the femur as a landmark. The sciatic nerve was exposed at mid-thigh level distal to the trifurcation and freed of connective tissue; the three peripheral branches (sural, common peroneal, and tibial nerves) of the sciatic nerve were exposed without stretching nerve structures. Both tibial and common peroneal nerves were ligated and transacted together. A micro-surgical forceps with curved tips was delicately placed below the tibial and common peroneal nerves to slide the thread (5.0 silk, Ethicon; Johnson, and Johnson Intl, Brussels, Belgium) around the nerves. A tight ligation of both nerves was performed. The sural nerve was carefully preserved by avoiding any nerve stretch or nerve contact with surgical tools. Muscle and skin were closed in two distinct layers with silk 5.0 suture. Intense, reproducible and long-lasting thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia-like behaviors are measurable in the non-injured sural nerve skin territory [23]. The SNI model offers the advantage of a distinct anatomical distribution with an absence of co-mingling of injured and non-injured nerve fibers distal to the lesion such as the injured and non-injured nerves and territories can be readily identified and manipulated for further analysis (i.e. behavioral assessment).

The sham procedure consisted of the same surgery without ligation and transection of the nerves.

Groups of mice were divided as follows:

Naïve (n = 5);

Sham-operated mice (n = 5);

SNI mice treated with vehicle (SNI/vehicle) (n = 5);

SNI mice treated with hMSCs (50 × 103 cells/5 μl) (SNI/hMSCs) (n = 5).

Nociceptive behavior

Thermal hyperalgesia was evaluated by using a Plantar Test Apparatus (Ugo Basile, Varese, Italy). On the day of the experiment, each animal was placed in a plastic cage (22 cm × 17 cm × 14 cm; length × width × height) with a glass floor. After a 60-min habituation period, the plantar surface of the hind paw was exposed to a beam of radiant heat through the glass floor. The radiant heat source consisted of an infrared bulb (Osram halogen-bellaphot bulb; 8 V, 50 W). A photoelectric cell detected light reflected from the paw and turned off the lamp when paw movement interrupted the reflected light. The paw withdrawal latency was automatically displayed to the nearest 0.1 s; the cut-off time was 20 s in order to prevent tissue damage.

Mechanical allodynia was measured by using Dynamic Plantar Anesthesiometer (Ugo Basile). Mice were allowed to move freely in one of the two compartments of the enclosure positioned on the metal mesh surface. Mice were adapted to the testing environment before any measurements were taken. After that, the mechanical stimulus was delivered to the plantar surface of the hindpaw of the mouse from below the floor of the test chamber by an automated testing device. A steel rod (2 mm) was pushed with electronical ascending force (0–30 g in 10 s). When the animal withdrawn its hindpaw, the mechanical stimulus was automatically withdrawn and the force recorded to the nearest 0.1 g. Nociceptive responses for thermal and mechanical sensitivity were expressed as thermal paw withdrawal latency (PWL) in seconds and mechanical paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) in grams.

Each mouse served as its own control, the responses being measured both before and after surgical procedures. PWL and PWT were quantified by an observer blinded to the treatment.

Motor coordination behavior

Neurological functions and motor coordination were evaluated by Rotarod motor test (Ugo Basile). This test consists of putting the mouse on a rotary cylinder in order to then measure the time (in seconds) of its equilibrium before falling. The cylinder is subdivided in five sections, allowing the screening of five animals per test (one for section), simultaneously. Below the cylinder there is a platform in its turn subdivided in five plates (in correspondence of the five sections) everyone of which it is connected to a magnet that, activated from the fall of the mouse on the plate, records the time of permanence on the cylinder. After a period of adaptation of 30 s, the spin speed gradually increased from 5 to 40g for the maximum time of 5 min. On the same day, the animals were analyzed by two separate tests with a time interval of 1 h. The experiment was performed for every group of animals: the day before the surgical procedure, the day before the behavioral tests in order to avoid useless stress, the day before the stem cell administration, and from the day 6 after SNI. The time of permanence of the mouse on the cylinder was expressed as latency (s).

Human mesenchymal stem cell cultures

Human bone marrow-derived MSCs were isolated from a small aspirate of bone marrow and in vitro expanded in basic-fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-containing medium as already described [24]. In brief, bone marrows were obtained from healthy donors after informed consent. Bone marrow aspirates were collected from iliac crests, separated on Ficoll density gradient (GE Healthcare, Italy), and the mononuclear cell fraction was harvested and washed in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Then, 1–2.5 × 105 cells per cm2 were seeded in 100-mm dishes with α-modified Eagle’s medium (α-MEM) (Lonza, Verviers, Belgium) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (EuroClone-Celbio, Milan, Italy), 2 ng/ml basic FGF (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (all Lonza) (proliferating medium). After 24–48 h, non-adherent cells were discarded, and adherent cells representing MSCs along with committed progenitors were washed twice with PBS. Cells were then incubated for 7–10 days in proliferating medium to reach confluence, and extensively propagated for further experiments. We used cells till the 4th passage, each time we plated 2 × 103 cells per cm2. The same day as the transplantation procedure, hMSCs were labeled with fluorescent Vybrant CM-DiI cell labeling solution (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

We did not characterize hMSCs by flow cytometry in order to be more reliable than the clinical trial protocols currently used (see http://www.clinicaltrials.gov). We characterized hMSCs by their adherence in culture conditions in vitro (and we performed their safety evaluations which include culture and check of pathogenic microorganisms). In addition, we stained hMSCs for CD73 specific marker after in vivo transplantation.

Human mesenchymal stem cell transplantation procedure

On the day of the transplantation, mice were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg i.p.) and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus. The skull was exposed through a longitudinal incision that allows a view of the bregma, the cranial reliquary was then drilled at the reached coordinated, and labeled hMSCs were microinjected into by using a 5-μl Hamilton syringe attached to the stereotaxic apparatus. A volume of 5 μl of solution (stem cells + vehicle) or vehicle were injected over a period of 5 min. Labeled hMSCs were suspended in PBS with 10% heparin and transplanted to neuropathic mice, while control mice were administered with 5 μl PBS with 10% heparin (vehicle solution). Each neuropathic mice received 50,000 cells/5 μl. The amount of cells to be injected was chosen on the basis of a previous study [25]. Indeed, it has been observed that a higher number of cells may cause cell cluster formation within the microinjection cannula which, in turn, may be responsible for cell damage and decreased viability. After the administration, antibiotic was applied to the exposed tissue to prevent infection. hMSCs were microinjected controlaterality to the sciatic nerve injury into the lateral cerebral ventricle of the mouse using coordinates from the Atlas of Paxinos and Watson [26]: AP = 3.5 mm and L = 1.0 mm from bregma, V = 2.5 mm below the dura.

Stem cells injection was performed 4 days after sciatic nerve surgery. Neuropathic mice were monitored 7, 10, 14, 17, and 21 days after surgery.

Fluorescence immunocytochemistry: phenotypic characterization of the human mesenchymal stem cells

Transplanted human MSCs were used for immunofluorescence analysis of the expression of surface antigen CD73. In brief, animals were perfused transcardially with 150 ml of saline solution (0.9% NaCl), and 250 ml of 4% paraformaldheyde fixative. The brain was taken out and kept in the fixative for 24 h at 4°C. The tissue was kept in 30% sucrose in PBS and frozen in cryostat embedding medium (Bio-Optica, Milan, Italy). Serial 15-μm sections of the brain were cut using a cryostat and thaw-mounted onto glass slides. After washing in PBS, non-specific antibody binding was inhibited by incubation for 30 min in blocking solution (1% BSA, 0.2% powdered skim milk, 0.3% Triton-X 100 in PBS). Primary antibodies were diluted in PBS blocking buffer and slides were incubated overnight at 4°C in primary antibodies to human monoclonal anti-CD73 (1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), to mouse monoclonal anti-NeuN (1:200; Chemicon-Millipore, Billerica, MA), to mouse poly-clonal anti-glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP, 1:1,000; Dako Cytomation, Denmark), to mouse poly-clonal anti-ionised calcium binding adapter molecule1 (Iba-1, 1:500; Wako Chemicals, Germany), and to mouse poly-clonal anti-interleukin 1β (IL-1β, 1:75; Santa Cruz Biotech, CA). Fluorescent-labeled secondary antibodies (1:500; Alexa Fluor 488, 568, Molecular Probe; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) specific to the IgG species used as a primary antibody were used to locate the specific antigens in each section. Sections were counterstained with bisbenzimide (Hoechst 33258; Hoechst, Frankfurt, Germany) and mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Fluorescently labeled sections were viewed with a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) to locate the cells and identify the brain area.

Immunofluorescence images of four stained sections were taken for each animal. 12–20 images were analyzed for each experimental group with Axiovision Rel. 4.6 software (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). For cell counting, a ×20 image of the brain was captured. The number of profiles positive for each marker were determined within three boxes measuring 104 μm2 for each section. Number quantification of NeuN-ir, GFAP-ir and Iba-1-ir profiles was performed by an observer blind to the treatment by using Axion vision rel. 4.6 software. Cell positive profile quantification was performed on each digitised image, and the reported data are the means ± SE from 25 sections per group. To avoid cell overcounting, only bisbenzimide-counterstained cells were considered as positive profiles.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase assay

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase assay was used to study neuronal cell suffering. After fixation and cutting procedure, brain sections were washed with PBS and then incubated at 37°C for at least 2 h with a staining solution [citric acid/phosphate buffer (pH6), K4Fe(CN)6, K3Fe(CN)6, NaCl, MgCl2, X-Gal]. The percentage of senescent suffering cells was calculated by the number of blue cells (β-galactosidase positive cells) out of at least 500 cells in different microscope fields.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from 5-μm tissue sections of mouse brain containing the injection site using an RNeasy FFPE kit (Qiagen, Milan, Italy) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The total RNA concentration was determined by UV spectrophotometer. The mRNA levels of the genes under analysis were measured by RT-PCR amplification, as previously reported [22]. Reverse transcriptase from avian myeloblastosis virus (AMV-RT; Promega, Madison, WI) was used. Briefly, for first-strand cDNA synthesis, 100 ng total RNA, random examers, dNTPs (Promega), AMV buffer, AMV-RT and recombinant RNasin ribonuclease inhibitor (Promega) were assembled in diethyl-pyrocarbonate-treated water to a 20-μl final volume and incubated for 10 min at 65°C and 1 h at 42°C. Aliquots of 2 μL cDNA were transferred into a 25 μl PCR-reaction mixture containing dNTPs, MgCl2 buffer, specific primers and GoTaq Flexi DNA polymerase (Promega) and amplification reactions using specific primers and conditions for mouse IL-1β and IL-10 (human and mouse) cDNAs and the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were carried out. RT minus controls were carried out to check potential genomic DNA contamination. These RT minus controls were performed without using the reverse transcriptase enzyme in the reaction mix. Sequences for the mouse mRNAs from GeneBank (DNASTAR, Madison, WI) were used to design primer pairs for RT-PCRs (OLIGO 4.05 software; National Biosciences, Plymouth, MN) (primers available on request). Each RT-PCR was repeated at least three times to achieve best reproducibility data. The mean of the inter-assay variability of each RT-PCR assays was 0.07. PCR products were resolved into 2.0% agarose gel. A semiquantitative analysis of mRNA levels was carried out by the “Gel Doc 2000 UV System” (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The measured mRNA levels were normalized with respect to GAPDH, chosen as housekeeping gene. The GAPDH gene expression did not change in neuropathic pain experimental conditions [7]. To our knowledge, there is no molecular evidence for variation in GAPDH mRNA-levels in SNI neuropathic pain model. The gene expression values were expressed as arbitrary units ± SEM. Amplification of genes of interest and GAPDH were performed simultaneously.

Statistical analysis

Behavioral and molecular data are shown as means ± SEM ANOVA, followed by Student–Neuman–Keuls post hoc test, was used to determine the statistical significance among groups. Immunocytochemical data are shown as means ± SEM ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, was used to determine the statistical significance among groups. P < 0.01 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Human mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in neuropathic mice does not affect motor function but reduces mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in neuropathic mice

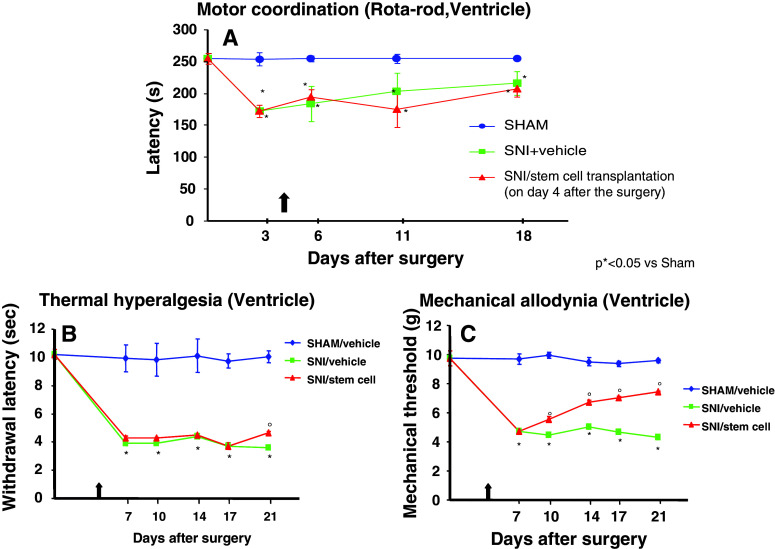

Bone marrow-derived human MSCs were transplanted in the brain lateral ventricle. Stem cell transplantation did not affect the neurological functions of the neuropathic mice, once transplanted in the ventricle area (Fig. 1a). Neither transplantation procedure or stem cells modified motor coordination. The pain model we used involves a lesion of two of the three terminal branches of the sciatic nerve (tibial and common peroneal nerves, leaving the remaining sural nerve intact); neuropathic mice are less able to walk respect to naïve mice. In order to exclude any further motor impairment that would possibly be generated by hMSCs, we applied the rotarod test to compare SNI/hMSC- with SNI/vehicle-treated mice. As shown in Fig. 1a, there is no difference in the motor coordination outcome for these two groups of animals.

Fig. 1.

a Rotarod motor testing results. The effects of human mesenchymal stem cell injection on motor performance in the rotarod test is shown. Intra-brain administration of hMSCs in ventricle of SNI-mice had no effect on motor function compared with vehicle-treated SNI-mice. Human MSCs were transplanted on day 4 after the SNI surgery. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM of the latency (s) (n = 5 mice/group). *P < 0.05 vs sham/vehicle. b Effects of human mesenchymal stem cells on reflex withdrawal responses (s, mean ± SEM) to thermal noxious stimuli in SNI mice. The onset of SNI-induced thermal hyperalgesia was evaluated in ipsilateral sides at 7, 10, 14, 17, and 21 days post-SNI. SNI mice showed a significant reduction in withdrawal latency to radiant heat in the ipsilateral paw (*P < 0.05 vs sham-operated mice). Human MSC treatment (on day 4 after SNI surgery, as indicated by the arrow) prevented the appearance of thermal hyperalgesia on day 21 after SNI (°P < 0.05 vs SNI mice). c Effects of human mesenchymal stem cells on reflex withdrawal responses (g, mean ± SEM) to mechanical noxious stimuli in SNI mice. The onset of SNI-induced mechanical allodynia was evaluated in ipsilateral sides at 7, 10, 14, 17, and 21 days post-SNI. Mice showed a significant reduction in the threshold to mechanical stimulation in the ipsilateral paw (*P < 0.05 vs sham-operated mice) after SNI surgery. Human MSC treatment (on day 4 after SNI surgery, as indicated by the arrow) prevented the appearance of mechanical allodynia at 7, 10, 14, 17, and 21 days post-SNI (°P < 0.05 vs SNI mice)

Neuropathic mice were subjected to stem cell transplantation after 4 days from sciatic nerve injury and were monitored 7, 10, 14, 17, and 21 days after surgery. We injected hMSCs when neuropathic pain was already established (4 days after SNI surgery) to assess their potential role as therapeutic tool in pain care. Human MSCs were able to reduce pain-like behaviors, such as mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia, once transplanted in the ventricle (Fig. 1b, c).

Nociceptive responses to thermal and mechanical stimuli (paw withdrawal latency, PWL and paw withdrawal threshold, PWT, respectively) were measured every 30 min for 3 h before surgery or 7, 10, 14, 17, and 21 days after sciatic nerve surgery. The mean PWL and PWT was calculated from six consecutive trials (each performed every 30 min) and averaged for each group of mice.

Sham mice treated 4 days after SNI surgery with vehicle did not show any change in PWL and PWT compared to the naïve mice (data not shown). SNI mice treated with vehicle developed mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in the ipsilateral side at 7, 10, 14, 17, and 21 days from surgery, compared to sham mice treated with vehicle (Fig. 1b, c) but not in the contralateral side (data not shown). Transplantation of hMSCs in the ventricle of SNI mice significantly reduced mechanical allodynia in the ipsilateral side (Fig. 1c) without any change in the contralateral side (data not shown) with respect to SNI mice treated with vehicle. A reduction in thermal hyperalgesia in the ipsilateral side (but not in contralateral side) of SNI mice compared with SNI mice treated with vehicle was also observed when stem cells were transplanted in the ventricle only 21 days after the sciatic nerve injury (Fig. 1b).

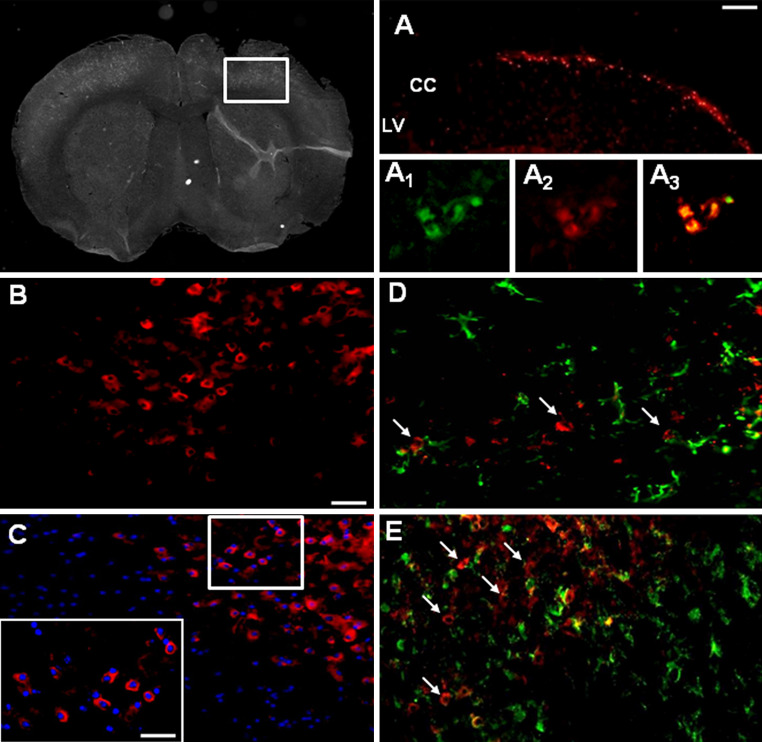

Fluorescent DiI-labeled hMSCs home neighboring to the injection site after transplantation

Brains were harvested from transplanted neuropathic mice at 21 days after SNI injury (17 days after stem cell transplantation) to verify the homing of hMSCs at the injury site. Fluorescent analysis conducted on the brain cross-sections at level of injury site revealed a preferential accumulation of labeled DiI-hMSCs close to the area of injection (Fig. 2a). No labeled DiI-hMSCs were detectable in contralateral uninjured hemispheres, thus revealing the specificity of hMSC engraftment at the injury site (Fig. 2). However, we did observe a possible stem cell migration along the corpus callosum (Fig. 2a). We found that DiI-fluorescent labeling was a successfully staining to follow stem cell homing or migration once transplanted in mouse brain. Positive DiI-labeled hMSCs were also CD73 positive cells (see following paragraph and Fig. 2: a1, a2, a3).

Fig. 2.

Representative cross-section of mouse whole midbrain area from hMSC-treated 21 days neuropathic mice. a DiI-labeled hMSCs homed at the injection site after transplantation, with a possible stem cell migration along the corpus callosum; LV lateral ventricle, CC corpus callosum. a1 Human MSCs expressed lineage-specific antigens at the time of injection in vivo. Representative fluorescent photomicrograph of hMSCs showing immunocytochemistry for CD73. CD73-positive hMSCs emitted green fluorescence. a2 DiI-labeled hMSCs emitted red fluorescence. a3 Pictures with both green and red fluorescence were merged. b Area in white rectangle inset is shown: CD73 positive hMSCs emitting red fluorescence. c The cell nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue fluorescence), the inset represents ×40 magnification of the area in white rectangle (×20 magnification). d Double labeling of GFAP and CD73 positive profiles. Arrows indicate no merging between astrocytes and hMSCs. e Double labeling of Iba-1 and CD73 positive profiles. Arrows indicate no merging between microglial cells and hMSCs. Scale bars 100 μm (a), 50 μm (b–e) and 25 μm (inset in c)

Human mesenchymal stem cells are positive for specific antigens

Transplanted hMSCs were positive for lineage-specific antigens 17 days after transplantation procedure. The expression of these antigens is a valid marker recognized as one of the criteria to identify MSCs [27]. In particular, we successfully verified by immunocytochemistry that transplanted hMSCs expressed the surface antigens CD73 (NT5E, ecto-5′-nucleotidase, E5NT, NTE) (Fig. 2b, c). The mouse anti-human CD73 antibody detects glycosyl phosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored purine salvage enzyme expressed on the surface of hMSCs. The antibody does not cross-react with other human antigens or with other mouse (host) antigens.

Transplanted human mesenchymal stem cells do not differentiate in neuronal and glial lineage but they are able to reduce astroglial and microglial positive profiles

To verify whether the anti-nociceptive effects of hMSCs seen in our study were due to a cellular differentiation, we checked for the presence of specific neuronal and glial markers in transplanted hMSCs.

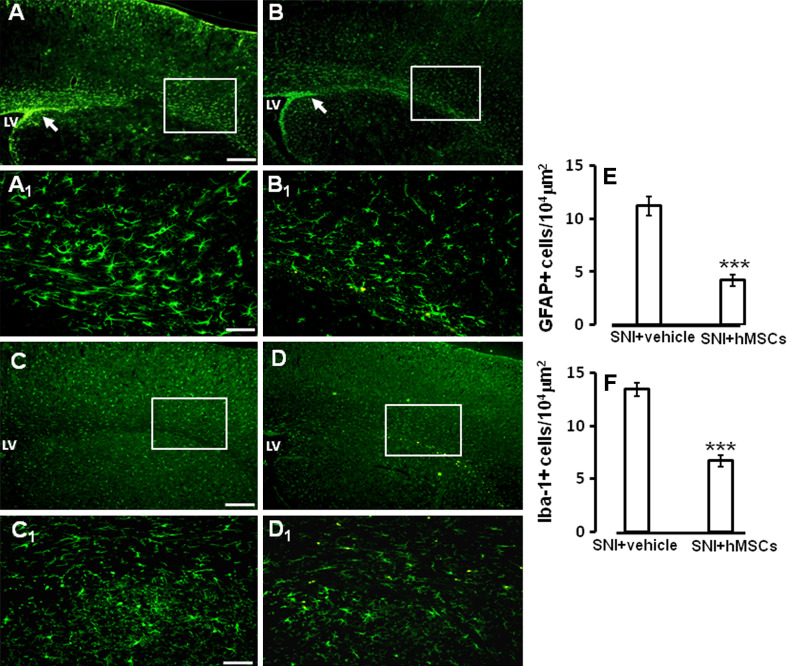

On day 21, after sciatic nerve surgery (on day 17 after stem cell treatment) transplanted hMSCs did not express either the astrocytic glial marker GFAP, or the microglial marker Iba-1 (Fig. 2d, e), or the neuronal marker NeuN (data not shown). Moreover, the number of astrocytic cells labeled using GFAP were found to be significantly reduced in SNI/hMSC-treated neuropathic mice compared to SNI/vehicle-treated neuropathic mice (Fig. 3a, a1–b, b1–e).

Fig. 3.

a GFAP labeling of ventricle and somatosensory forelimb cortex from vehicle-treated 21 days-neuropathic mice. Notice the increased staining in the periventricular area, as indicated by the arrow; LV lateral ventricle. a1 High magnification of a, showing GFAP positive astrocytes. b GFAP labeling of ventricle and somatosensory forelimb cortex from hMSC-treated 21 days-neuropathic mice. Human MSC treatment was able to decrease GFAP staining in the periventricular area, as indicated by the arrow; LV lateral ventricle. b1 High magnification of b, showing reduced GFAP positive astrocytes. c Iba-1 labeling of ventricle and somatosensory forelimb cortex from vehicle treated neuropathic mice; LV lateral ventricle. c1 High magnification of c, showing Iba-1 positive microglial cells. d Iba-1 labeling of ventricle and somatosensory forelimb cortex from hMSC-treated neuropathic mice. Human MSC treatment was able to decrease Iba-1 staining in the periventricular area; LV lateral ventricle. d1 High magnification of d, showing reduced Iba-1 positive microglial cells. Scale bars 100 μm (a,b), 50 μm (a1, b1), 100 μm (c,d), and 50 μm (c1, d1). e The number of the GFAP positive profiles, indicating a strong reduction in the number of astrocytes after hMSC transplantation in neuropathic mice as compared to vehicle treated neuropathic animals. ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, was used to determine the statistical significance among groups. ***P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. f The number of the Iba-1 positive profiles, indicating a significant reduction in the number of microglial cells after hMSC transplantation in neuropathic mice as compared to vehicle treated neuropathic animals. ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, was used to determine the statistical significance among groups. ***P < 0.01 was considered statistically significant

The number of microglial cells labeled using Iba-1 were also significantly decreased in hMSC-treated neuropathic mice compared to vehicle-treated neuropathic mice (Fig. 3c, c1–d, d1–f).

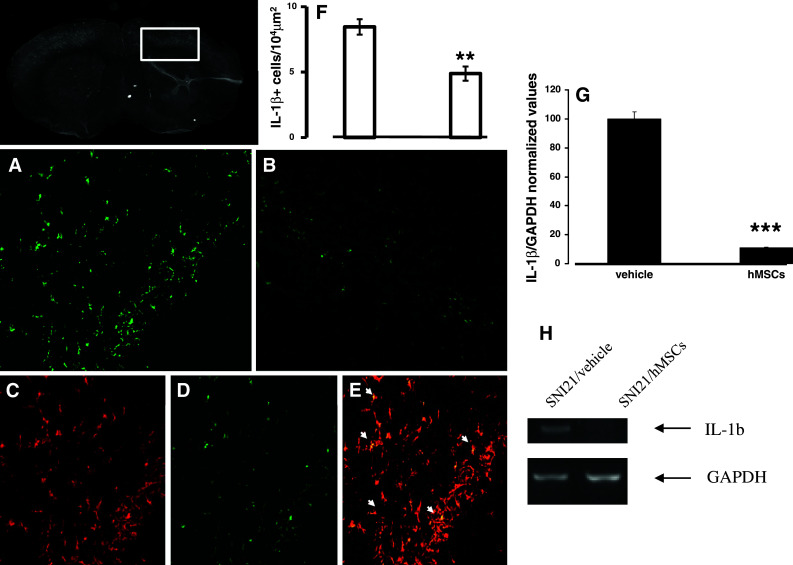

Human mesenchymal stem cells are able to reduce IL-1β pro-inflammatory gene and protein expression in neuropathic mice

In our model, transplanted hMSCs did not differentiate in any neuronal or glial cellular population; however, since they affected the mouse astrocytes and microglial cells, we hypothesized an anti-inflammatory action for stem cell anti-nociceptive mechanism.

Human MSCs were able to decrease the pro-inflammatory interleukin IL-1β positive profiles in the cortex of SNI/hMSC-treated mice compared to SNI/vehicle mice (Fig. 4a, b, f). IL-1β positive profiles were found co-localized with GFAP astrocytic marker positive profiles (Fig. 4c, d, e), but not with specific microglial or neuronal markers (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Representative cross-section of mouse whole midbrain area from hMSC-treated 21 days-neuropathic mice. a IL-1β positive profiles in the area enclosed by the white perimeter from vehicle treated 21 days-neuropathic mice. Scale bar 50 μm (a,b). b IL-1β positive profiles in the area enclosed by the white perimeter from hMSC-treated neuropathic mice, indicating a reduction in IL-1β profiles after hMSC treatment. c GFAP positive profiles in hMSC-treated neuropathic mice. d IL-1β positive profiles in hMSC-treated neuropathic mice. e Double labeling of GFAP and IL-1β positive profiles. Arrows indicate that the cells expressing IL-1β were astrocytes. f The number of the IL-1β positive profiles, indicating a significant reduction in the number of the cells expressing this interleukin after hMSC transplantation in neuropathic mice as compared to vehicle treated neuropathic animals. ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, was used to determine the statistical significance among groups. **P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. g IL-1β/GAPDH normalized values as obtained by RT-PCR analysis. Human MSC treatment (on day 4 after SNI surgery) reduced the mRNA levels of IL-1β gene in 21 days neuropathic mice (SNI21/hMSCs) respect to vehicle-treated 21 days-neuropathic mice (SNI21/vehicle). ANOVA, followed by Student–Neuman–Keuls post hoc test, was used to determine the statistical significance among groups. ***P < 0.01 was considered statistically significant. h Representative agarose gel blot analysis for IL-1β and housekeeping GAPDH mouse genes following RT-PCR. The semiquantitative analysis of mRNA levels was carried out by the “Gel Doc 2000 UV System” (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Human MSC treatment (on day 4 after SNI surgery) reduced the mRNA levels of IL-1β gene in 21 days-neuropathic mice (SNI21/hMSCs) respect to vehicle-treated 21 days-neuropathic mice (SNI21/vehicle)

The semiquantitative analysis of mRNA levels measured by RT-PCR amplification, at the same brain area of morphological analysis, showed a decrease in the pro-inflammatory IL-1β mouse gene expression (mean ± SE of arbitrary units: 0.12 ± 0.04 vs 1.10 ± 0.08 in SNI/hMSC-treated mice with respect to the SNI/vehicle mice, respectively) (Fig. 4g, h), but no change in the anti-inflammatory IL-10 gene (both human and mouse) was observed by 21 days sciatic nerve SNI (data not shown). For all genes and proteins examined, naïve and sham animals showed no differences in the expression levels (data not shown).

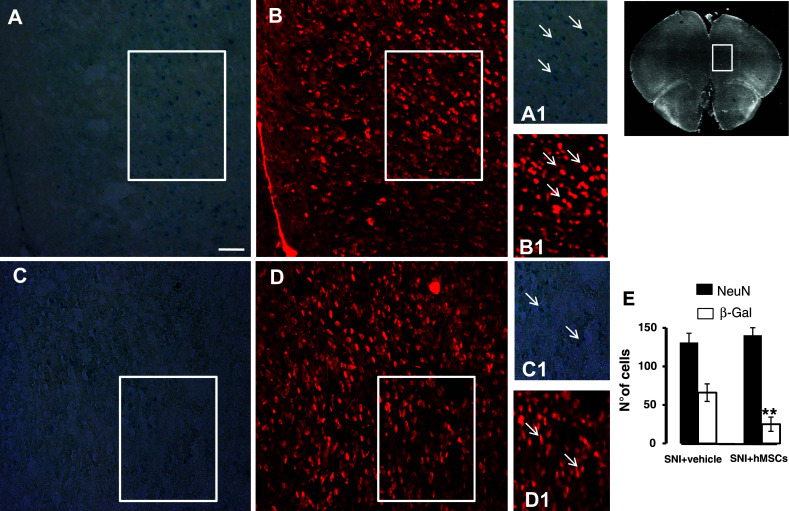

Human mesenchymal stem cells reduce β-galactosidase over-activation in prelimbic and infralimbic cortex in neuropathic mice

In our model, transplanted hMSCs did not differentiate in neurons nor increase neuronal positive profiles, but they were able to reduce premature senescence-associated neuronal suffering. Indeed, hMSCs were able to decrease the β-galactosidase over-activation positive profiles in the cortex of SNI/hMSC-treated mice compared to SNI/vehicle mice (Fig. 5). The percentage of β-galactosidase positive staining was calculated on NeuN positive cells.

Fig. 5.

Representative cross-section of mouse whole prefrontal cortex area from hMSC-treated 21 days-neuropathic mice. a β-Gal positive profiles in the pre-limbic and infra-limbic cortex area from vehicle-treated 21 days-neuropathic mice. b NeuN positive profiles in the same area from vehicle-treated neuropathic mice (a1, b1). A detail enclosed in the white square of β-Gal and NeuN, respectively; arrows indicate the β-Gal positive profiles expressed in the NeuN-labeled neuronal cells. c β-Gal positive profiles in the pre-limbic and infra-limbic cortex area from hMSC-treated 21 days-neuropathic mice. d NeuN positive profiles in the same area from hMSC-treated neuropathic mice (c1, d1). A detail enclosed in the white square of β-Gal and NeuN, respectively; arrows indicate less β-Gal positive profiles expressed in the NeuN-labeled neuronal cells. e The number of the β-Gal positive profiles, indicating a significant reduction in the number of suffering, senescent neuronal cells after hMSC transplantation in neuropathic mice as compared to vehicle-treated neuropathic animals. ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, was used to determine the statistical significance among groups. **P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Scale bar 50 μm

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that a single intra-ventricle administration of human bone marrow-derived MSCs was able to decrease neuropathic pain-associated behaviors and to trigger molecular and cellular changes. It has previously been observed that MSCs injected into the ipsilateral L4 dorsal root ganglia resulted in a reduction of neuropathic pain in animals with a sciatic nerve lesion [28]. This cell administration induced changes in neuropeptide expression in primary afferent neurons and prevented the development of mechanical and thermal allodynia.

We chose the cerebral ventricle as injection site since our study was focused on further understanding the involvement of the supraspinal centres (i.e. the circumventricular nuclei) and the anti-allodynic role and homing of stem cells in neuropathic pain condition. Indeed, there is evidence that the lateral ventricle can be a site for neurogenesis, as the circumventricular nuclei are potential neurogenic sources in the adult brain after injury [29, 30]. Moreover, transplanted cells can migrate from the ventricle towards the cortex [31, 32]. Transplantation into the lateral ventricle is the most effective to treat hypoxic-ischemic damage [33].

How the stem cells work is still controversial. In principle, stem cells can act through several possible mechanisms, i.e. stimulating the plastic response or neural activity in the host damaged tissue, secreting survival-promoting neurotrophic factors, restoring synaptic transmitter release by providing local re-innervations, integrating into existing neural and synaptic network, and re-establishing functional afferent and efferent connections [34]. Exogenously applied MSCs have been shown to home to injured tissues and repair them by producing chemokines, differentiating into specific cell types, or possibly by cell or nuclear fusion with host cells [35].

Recent evidence seems to be opening the way to explain stem cell-mediated neuroprotective effects. Stem cells could act as biologic “micro-pumps” to chronically deliver anti-nociceptive molecules close to the pain processing centres or the sites of injury, rather than their differentiation and replacement processes in pain reduction [36]. However, it could be possible to reconstitute a tissue by using stem cells. Mesenchymal stem cells have been shown to participate in the regeneration process that is activated following different types of injury of the nervous system [28]. MSCs are able to integrate into the tissue, replace damaged cells, and reconstruct neural circuitry. Injected bone marrow stromal cells into the lateral ventricle of neonatal mice adopt neural cell fates when exposed to the brain microenvironment and they are capable of producing differentiated progeny of a different dermal origin after implantation into neonatal mouse brains [25]. It has been indicated that hMSCs may facilitate recovery from spinal cord injury by re-myelinating spared white matter tracts and/or by enhancing axonal growth via differentiating into oligodendrocytes [37]. Cell replacement theory is based on the idea that replacement of degenerated neural cells with alternative functioning cells induces long-lasting clinical improvement [38]. On the other hand, after transplantation, only a few percent of MSCs expressed the neuronal, as well as astrocytic, phenotypes [39, 40]. This fact seems not enough to explain the improvement in functional outcome. In addition, these differentiated cells did not seem to develop functional interconnections with the intrinsic cells of the recipient animals. In our experimental model, transplanted hMSCs did not differentiate either in a neuronal or a glial and microglial phenotypes, indicating that the reconstruction of neural circuitry is not always a prerequisite for functional recovery. Our data highlight that it may be possible that the transplanted cells survive, integrate into the endogenous neural network, and lead to functional improvement. Indeed, intravenous administration of MSCs was able to increase the expression of some growth factors, such as nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), in the rat brain after traumatic brain injury [41]. Similarly, it has been shown that transplantation of pre-differentiated embryonic stem (ES) cells into neuronal progenitors is able to prevent the appearance of chronic pain in an experimental model of spinal cord injury in mice [42]. These pre-differentiated ES cells activate both BDNF and IL-6 signaling pathways in the host tissue leading to activation of cAMP/PKA, phosporylation of cofilin and synapsin I, and promotion of regenerative growth and neuronal survival [43]. However, it is important to consider that, apart from the different models used in those previous studies, we transplanted adult mesenchymal stem cells, but not embryonic stem cells. Also, Matsuda et al. have recently shown that ESs are responsible of tumor development in a mouse model of spinal cord injury (SCI), which in fact was blocked by MSCs. In addition, mice co-transplanted with MSCs did not show tumor development, and also showed sustained behavioral improvement [44]. Clinical transfer of cell transplantation therapy is hindered by legitimate concerns regarding the in vivo teratoma formation and uncontrollable cell proliferation of undifferentiated hESs. It has also been demonstrated that few ESs (in the order of 1 × 105 or 1 × 104 ESs) transplanted in several tissues give rise to teratoma development [45].

By contrast, adult stem cells could be transplanted directly without genetic modification or pre-treatments. They simply eventually differentiate according to cues from the surrounding tissues and do not give uncontrollable growth or tumors. MSCs show a high expansion potential, high genetic stability, and stable phenotype, can be easily collected and shipped from the laboratory to the bedside, and are compatible with different delivery methods and formulations [16, 46].

In addition, MSCs have two other extraordinary characteristics: they are able to migrate to sites of tissue injury and have strong immunosuppressive properties that can be exploited for successful autologous as well as heterologous transplantations [17]. In addition, MSCs are easily isolated from a small aspirate of bone marrow and expanded with high efficiency. In clinical application, there is no problem with immune rejection because the hMSCs can readily be isolated from the patients requiring transplant. There is also no tumor-formation on transplantation. And there is no moral objection involved.

Accordingly, we have verified in this study whether hMSCs could interfere with some specific physiological and anatomical changes occurring in neurons of prelimbic and infralimbic cortical areas in SNI mice [47]. These cortical areas are involved in chronic pain modulation, integration and maintenance, and can represent an optimal site for studying supraspinal neuropathic pain brain modifications, as emerging neuro-imaging analysis has revealed that pre-frontal cortex may be specifically involved in pain inhibition in humans [48]. Intriguingly, it has been demonstrated that gray matter density was reduced in bilateral dorsolateral pre-frontal cortex chronic pain conditions in humans [8]. To this aim, we performed experiments on β-galactosidase enzymatic activity for studying neuronal cell suffering in the prelimbic and infralimbic cortical areas. This enzyme can be considered as marker of stress-induced premature senescence, thus reflecting neuronal suffering condition [49]. We found that SNI was able to trigger β-galactosidase enzymatic activation in neurons and that hMSCs, although not changing the number of neuronal positive profiles, reduced neural β-galactosidase over-activation. Since MSCs have the capability to produce a large array of trophic and growth factors both in vivo and in vitro [50, 51], a more reasonable explanation for the functional benefit derived from MSC transplantation is that these cells are able to produce factors that activate endogenous restorative mechanisms within injured brain contributing to recovery of function lost as a result of lesions. MSCs constitutively secrete interleukins IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-11, IL-12, IL-14, IL-15, macrophage colony-stimulating factor, Flt-3 ligand, and stem-cell factor [52, 53]. According to this approach, the production of neurotrophic factors provided by transplanted MSCs supports neuronal cell survival, induces endogenous cell proliferation, and promotes nerve fibre regeneration at sites of injury. This fact could be the mechanism underlying the functional improvement in neuropathic pain seen after MSC transplantation shown in the present study. The neuroprotective effects of transplanted stem cells could be the result from a combination of neurotrophic and anti-inflammatory factors produced by transplanted stem cells. In addition, after stem cell treatment, we observed a significant decrease in the host pro-inflammatory IL-1β mouse gene expression. IL-1β is involved in the modulation of pain in both the peripheral and central nervous systems. It has been investigated that SNI triggers an increase in the expression of IL-1β gene in the brain of neuropathic rats [54]. The primers we used to perform RT-PCR analysis were designed to be specifically directed to IL-1β mouse gene, indicating that transplanted hMSCs could modulate the mRNA levels of endogenous inflammatory cytokines. In this way, through blockade of the pro-inflammatory cytokine cascade, hMSCs could affect functional recovery of the imbalance cytokine expression pattern due to the inflammatory processes associated with neuropathic pain [55, 56]. Noteworthy is the fact that we did not observe any changes in human IL-10 gene expression, nor in mouse IL-10 gene expression. We focused our attention on the endogenous balance between a pro- (IL-1β) and an anti- (IL-10) inflammatory mouse gene expression, showing a decrease in the pro-inflammatory mRNA levels after hMSC treatment. The mechanisms of action of IL-1β for inducing allodynia are not yet known, but increased evidences indicate that IL-1 is involved in the modulation of nociceptive information [57], contributing to the central sensitization associated with chronic neuropathic pain [58]. Nevertheless, we did not exclude the involvement of several other cytokines in the neuropathic pain progression, given that further molecular studies will be needed to elucidate the complete patterns of endogenous cytokines modulated by hMSCs, as well as the secreted cytokines by stem cells. In addition, further experimentation is needed to elucidate whether the effects of stem cells are due to cellular or paracrine activities.

Neuropathic pain progression may be mediated by modifications in glial responses to nociception [3, 59]. Indeed, activated glial cells are a source of central IL-1β release after peripheral injury [60]. IL-1β is able to induce the release of “endotoxins” from glial cells [61], influencing neuronal injury. In the pain model used, here we found that the cells producing the pro-inflammatory IL-1β were astrocytes (Fig. 4c, d, e). In addition, hMSC treatment was able to decrease the number of both glial and microglial cells, indicating that a possible mechanism of action of stem cells in reducing pain is by affecting the functionality of these cell types and by influencing the glial–cytokine–neuronal interactions.

Our results indicate that transplanted DiI-labeled hMSCs were able to home very close to the injection brain area. No labeled DiI-hMSCs were detectable in contralateral hemisphere. Stem cells have a strong ability to home to sites of injury by using chemokine signals [62, 63]. Besides, it has been already proposed that hMSCs homing at the injury/injection sites could exert a local and/or systemic immunosuppressive action thus limiting the inflammatory reactions and cell proliferation and migration [64–66]. In the light of our results demonstrating a strong decrease in allodynia after stem cell treatment, the cortical brain area may represent critical substrate in which analyzing specific biomarkers involved in neuropathic pain processing [67–70].

The human specificity of the marker we used to phenotypically characterize hMSCs allowed us to ensure that stem cells located in the brain area involved in neuropathic pain were heterologous transplanted stem cells. However, we cannot exclude a recruitment of homologous stem cells in the sites of injection [71].

In our study, day 21 is the starting time point that we can observe a decreased thermal hyperalgesia after hMSCs treatment. These data could indicate that hMSCs might need a longer time to exert their local effectiveness in the hyperalgesic state associated with neuropathic pain. A delay in stem cell-resolving thermal hyperalgesia has been already observed in a different model of neuropathic pain [72]. We cannot exclude a complete recovery of either allodynia or even thermal hyperalgesia after stem cell transplantation in SNI mice if a longer experimentation time was performed. This raises a critical question regarding the need of a longer time for stem cell transplantation to hopefully generate a full recovery from neuropathic pain symptoms. This may suggest that the time interval considered in this study is far too short to recognize whether: (1) stem cell merely accelerate a sort of “regeneration” but after sufficient survival time the same outcome was achieved in the vehicle-treated controls, (2) treatment can improve the final outcome after regeneration completion, or (3) both acceleration occurs and final outcome is improved. However, it is also important to consider that the SNI model is characterized by stable and persistent allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia at least for 3 months with no minimal recovery during that time, even with different vehicles systemically or intracerebrally administered [73]. Thus, it is unlikely that hMSCs can accelerate or improve any spontaneous pain resolution which in fact never happens spontaneously in the SNI model. Unfortunately, we have not had the possibility to measure allodynia or thermal hyperalgesia for a longer time (i.e. 2 or 3 months post-injury), and this was because the experimentation license for the use of laboratory animals did not permit the use of suffering animals in this study for more than 3 weeks.

In conclusion, we show here that human mesenchymal stem cells are able to reduce mechanical allodynia and to modify cellular and molecular pain mechanisms, once transplanted in the mouse cerebral ventricle, without affecting motor coordination. Our data demonstrated that hMSC treatment reduced the mRNA levels of the pro-inflammatory IL-1β mouse gene, as well as astrocytic and microglial cell activation. We suggested a possible mechanism of action of stem cells in reducing pain. Human MSCs could exert their action through a neuro-restorative “paracrine” mechanism, involving: (1) regeneration of the glial–cytokine–neuronal interactions, disrupted in neuropathic pain progression; (2) limitation of the inflammatory reactions; (3) limitation of glial/microglial cell proliferation; and (4) partial normalization of prefrontal cortex neural activity. Due to the limited success of current available drugs, new molecular strategies are needed for best approaches to neuropathic pain treatment [12]. Indeed, this study provides evidence that hMSCs injection may be a more suitable therapy than “classical” drugs to decrease neuropathic pain symptoms, supporting a therapeutic potentiality of hMSCs as anti-allodynic tool in untreatable neuropathic pain care.

References

- 1.Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain. Seattle: IASP; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siniscalco D, de Novellis V, Rossi F, Maione S. Neuropathic pain: is the end of suffering starting in the gene therapy? Curr Drug Targets. 2005;6:75–80. doi: 10.2174/1389450053344966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Novellis V, Siniscalco D, Galderisi U, Fuccio C, Nolano M, Santoro L, Cascino A, Roth KA, Rossi F, Maione S. Blockade of glutamate mGlu5 receptors in a rat model of neuropathic pain prevents early over-expression of pro-apoptotic genes and morphological changes in dorsal horn lamina II. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46:468–479. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siniscalco D, Fuccio C, de Novellis V, Rossi F, Maione S. Molecular methods for neuropathic pain treatment. J Neuropathic Pain. 2005;1(3):35–42. doi: 10.1300/J426v01n03_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galluzi KE. Management of neuropathic pain. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2005;105:12–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmermann M. Pathobiology of neuropathic pain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;429:23–37. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(01)01303-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maione S, Siniscalco D, Galderisi U, de Novellis V, Uliano R, Di Bernardo G, Berrino L, Cascino A, Rossi F. Apoptotic genes expression in the lumbar dorsal horn in a model neuropathic pain in rat. Neuroreport. 2002;13(1):101–106. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200201210-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apkarian AV, Sosa Y, Sonty S, Levy RM, Harden RN, Parrish TB, Gitelman DR. Chronic back pain is associated with decreased prefrontal and thalamic gray matter density. J Neurosci. 2004;24(46):10410–10415. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2541-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao Q, Benton RL, Whittemore SR. Stem cell repair of central nervous system injury. J Neurosci Res. 2002;68(5):501–510. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindvall O, Kokaia Z. Stem cells for the treatment of neurological disorders. Nature. 2006;441(7097):1094–1096. doi: 10.1038/nature04960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindvall O, Kokaia Z. Stem cell therapy for human brain disorders. Kidney Int. 2005;68(5):1937–1939. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siniscalco D, Rossi F, Maione S. Molecular approaches for neuropathic pain treatment. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:1783–1787. doi: 10.2174/092986707781058913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Short B, Brouard N, Occhiodoro-Scott T, Ramakrishnan A, Simmons PJ. Mesenchymal stem cells. Arch Med Res. 2003;34:565–571. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beyer Nardi N, Da Silva Meirelles L. Mesenchymal stem cells: isolation, in vitro expansion and characterization. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2006;174:249–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sethe S, Scutt A, Stolzing A. Aging of mesenchymal stem cells. Ageing Res Rev. 2006;5:91–116. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giordano A, Galderisi U, Marino IR. From the laboratory bench to the patient’s bedside: an update on clinical trials with mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211:27–35. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Blanc K, Pittenger M. Mesenchymal stem cells: progress toward promise. Cytotherapy. 2005;7:36–45. doi: 10.1080/14653240510018118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beggs KJ, Lyubimov A, Borneman JN, Bartholomew A, Moseley A, Dodds R, Archambault MP, Smith AK, McIntosh KR. Immunologic consequences of multiple, high-dose administration of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells to baboons. Cell Transplant. 2006;15:711–721. doi: 10.3727/000000006783981503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jori FP, Napolitano MA, Melone MA, Cipollaro M, Cascino A, Altucci L, Peluso G, Giordano A, Galderisi U. Molecular pathways involved in neural in vitro differentiation of marrow stromal stem cells. J Cell Biochem. 2005;94:645–655. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazzini L, Mareschi K, Ferrero I, Vassallo E, Oliveri G, Nasuelli N, Oggioni GD, Testa L, Fagioli F. Stem cell treatment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Cell Biochem. 2005;94:645–655. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bae JS, Han HS, Youn DH, Carter JE, Modo M, Schuchman EH, Jin HK. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells promote neuronal networks with functional synaptic transmission after transplantation into mice with neurodegeneration. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1307–1316. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Musolino PL, Coronel MF, Hokfelt T, Villar MJ. Bone marrow stromal cells induce changes in pain behavior after sciatic nerve constriction. Neurosci Lett. 2007;418:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bourquin AF, Süveges M, Pertin M, Gilliard N, Sardy S, Davison AC, Spahn DR, Decosterd I. Assessment and analysis of mechanical allodynia-like behavior induced by spared nerve injury (SNI) in the mouse. Pain. 2006;122:e1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Squillaro T, Hayek G, Farina E, Cipollaro M, Renieri A, Galderisi U. A case report: bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells from a Rett syndrome patient are prone to senescence and show a lower degree of apoptosis. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103:1877–1885. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kopen G, Prockop DJ, Phinney DG. Marrow stromal cells migrate throughout forebrain and cerebellum, and they differentiate into astrocytes after injection into neonatal mouse brains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10711–10716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. London: Academic; 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D, Deans R, Keating A, Dj Prockop, Horwitz E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(4):315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coronel MF, Musolino PL, Villar MJ. Selective migration and engraftment of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in rat lumbar dorsal root ganglia after sciatic nerve constriction. Neurosci Lett. 2006;405:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bennett L, Yang M, Enikolopov G, Iacovitti L. Circumventricular organs: a novel site of neural stem cells in the adult brain. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;41(3):337–347. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kinoshita MO, Shinoda Y, Sakai K, Hashikawa T, Watanabe M, Machida T, Hirabayashi Y, Furuya S. Selective upregulation of 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (Phgdh) expression in adult subventricular zone neurogenic niche. Neurosci Lett. 2009;453(1):21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang H, Huang Z, Xu Y, Zhang S. Differentiation and neurological benefit of the mesenchymal stem cells transplanted into the rat brain following intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurol Res. 2006;28(1):104–112. doi: 10.1179/016164106X91960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dayer AG, Jenny B, Potter G, Sauvain MO, Szabó G, Vutskits L, Gascon E, Kiss JZ. Recruiting new neurons from the subventricular zone to the rat postnatal cortex: an organotypic slice culture model. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27(5):1051–1060. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X, Yang YJ, Jia YJ, Yu XH, Zhong L, Xie M, Wang XL. The best site of transplantation of neural stem cells into brain in treatment of hypoxic-ischemic damage: experiment with newborn rats. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2007;87(12):847–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Capone C, Frigerio S, Fumagalli S, Gelati M, Principato MC, Storini C, Montinaro M, Kraftsik R, De Curtis M, Parati E, De Simoni MG. Neurosphere-derived cells exert a neuroprotective action by changing the ischemic microenvironment. PLoS One. 2007;2(4):e373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prockop DJ, Gregory CA, Spees JL. One strategy for cell and gene therapy: harnessing the power of adult stem cells to repair tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11917–11923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834138100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siniscalco D, Rossi F, Maione S (2008). Stem cell therapy for neuropathic pain treatment. J Stem cells Regenerative Med vol III (1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Cízková D, Rosocha J, Vanický I, Jergová S, Cízek M. Transplants of human mesenchymal stem cells improve functional recovery after spinal cord injury in the rat. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2006;26(7–8):1167–1180. doi: 10.1007/s10571-006-9093-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hess DC, Borlongan CV. Stem cells and neurological diseases. Cell Prolif. 2008;41(Suppl 1):94–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2008.00486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu D, Mahmood A, Wang L, Li Y, Lu M, Chopp M. Adult bone marrow stromal cells administered intravenously to rats after traumatic brain injury migrate into brain and improve neurological outcome. Neuroreport. 2001;12:559–563. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200103050-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahmood A, Lu D, Wang L, Li Y, Lu M, Chopp M. Treatment of traumatic brain injury in female rats with intravenous administration of bone marrow stromal cells. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:1196–1203. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200111000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mahmood A, Lu D, Chopp M. Intravenous administration of marrow stromal cells (MSCs) increases the expression of growth factors in rat brain after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:33–39. doi: 10.1089/089771504772695922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hendricks WA, Pak ES, Owensby JP, Menta KJ, Glazova M, Moretto J, Hollis S, Brewer KL, Murashov AK. Predifferentiated embryonic stem cells prevent chronic pain behaviors and restore sensory function following spinal cord injury in mice. Mol Med. 2006;12(1–3):34–46. doi: 10.2119/2006-00014.Hendricks. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glazova M, Pak ES, Moretto J, Hollis S, Brewer KL, Murashov AK. Pre-differentiated embryonic stem cells promote neuronal regeneration by cross-coupling of BDNF and IL-6 signaling pathways in the host tissue. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26(7):1029–1042. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsuda R, Yoshikawa M, Kimura H, Ouji Y, Nakase H, Nishimura F, Nonaka J, Toriumi H, Yamada S, Nishiofuku M, Moriya K, Ishizaka S, Nakamura M, Sakaki T. Co-transplantation of mouse embryonic stem cells and bone marrow stromal cells following spinal cord injury suppresses tumor development. Cell Transplant. 2009;18(1):39–54. doi: 10.3727/096368909788237122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee AS, Tang C, Cao F, Xie X, van der Bogt K, Hwang A, Connolly AJ, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Effects of cell number on teratoma formation by human embryonic stem cells. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(16):2608–2612. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.16.9353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jori FP, Melone MA, Napolitano MA, Cipollaro M, Cascino A, Giordano A, Galderisi U. RB and RB2/p130 genes demonstrate both specific and overlapping functions during the early steps of in vitro neural differentiation of marrow stromal stem cells. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:65–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Metz AE, Yau HJ, Centeno MV, Apkarian AV, Martina M. Morphological and functional reorganization of rat medial prefrontal cortex in neuropathic pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(7):2423–2428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809897106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Borckardt JJ, Smith AR, Reeves ST, Weinstein M, Kozel FA, Nahas Z, Shelley N, Branham RK, Thomas KJ, George MS. Fifteen minutes of left prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation acutely increases thermal pain thresholds in healthy adults. Pain Res Manag. 2007;12(4):287–290. doi: 10.1155/2007/741897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Volonte D, Galbiati F (2009) Inhibition of thioredoxin reductase 1 by caveolin 1 promotes stress-induced premature senescence. EMBO Rep doi:10.1038/embor.2009.215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Pisati F, Bossolasco P, Meregalli M, Cova L, Belicchi M, Gavina M, Marchesi C, Calzarossa C, Soligo D, Lambertenghi-Deliliers G, Bresolin N, Silani V, Torrente Y, Polli E. Induction of neurotrophin expression via human adult mesenchymal stem cells: implication for cell therapy in neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Transplant. 2007;16(1):41–55. doi: 10.3727/000000007783464443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pan HC, Cheng FC, Chen CJ, Lai SZ, Lee CW, Yang DY, Chang MH, Ho SP. Post-injury regeneration in rat sciatic nerve facilitated by neurotrophic factors secreted by amniotic fluid mesenchymal stem cells. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14(11):1089–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Majumdar MK, Thiede MA, Mosca JD, Moorman M, Gerson SL. Phenotypic and functional comparison of cultures of marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and stromal cells. J Cell Physiol. 1998;176:57–66. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199807)176:1<57::AID-JCP7>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eaves CJ, Cashman JD, Kay RJ, Dougherty GJ, Otsuka T, Gaboury LA, Hogge DE, Lansdorp PM, Eaves AC, Humphries RK. Mechanisms that regulate the cell cycle status of very primitive hematopoietic cells in long-term human marrow cultures, II: analysis of positive and negative regulators produced by stromal cells within the adherent layer. Blood. 1991;78:110–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Z, Wang J, Li X, Yuan Y, Fan G. Interleukin-1 beta of Red nucleus involved in the development of allodynia in spared nerve injury rats. Exp Brain Res. 2008;188(3):379–384. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1365-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Costigan M, Woolf CJ. Pain: molecular mechanisms. J Pain. 2000;1:35–44. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2000.9818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Apkarian AV, Lavarello S, Randolf A, Berra HH, Chialvo DR, Besedovsky HO, del Rey A. Expression of IL-1beta in supraspinal brain regions in rats with neuropathic pain. Neurosci Lett. 2006;407:176–181. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bianchi M, Dib B, Panerai AE. Interleukin-1 and nociception in the rat. J Neurosci Res. 1998;53(6):645–650. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980915)53:6<645::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gustafson-Vickers SL, Lu VB, Lai AY, Todd KG, Ballanyi K, Smith PA. Long-term actions of interleukin-1beta on delay and tonic firing neurons in rat superficial dorsal horn and their relevance to central sensitization. Mol Pain. 2008;4:63. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Milligan ED, Twining C, Chacur M, Biedenkapp J, O’Connor K, Poole S, Tracey K, Martin D, Maier SF, Watkins LR. Spinal glia and proinflammatory cytokines mediate mirrorimage neuropathic pain in rats. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1026–1040. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-01026.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guo W, Wang H, Watanabe M, Shimizu K, Zou S, LaGraize SC, Wei F, Dubner R, Ren K. Glial-cytokine-neuronal interactions underlying the mechanisms of persistent pain. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6006–6018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0176-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rothwell N. Interleukin-1 and neuronal injury: mechanisms, modification, and therapeutic potential. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17(3):152–157. doi: 10.1016/S0889-1591(02)00098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Corcione A, Benvenuto F, Ferretti E, Giunti D, Cappiello V, Cazzanti F, Risso M, Gualandi F, Mancardi GL, Pistoia V, Uccelli A. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate B-cell functions. Blood. 2006;107:367–372. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sze SK, de Kleijn DP, Lai RC, Tan EK, Zhao H, Yeo KS, Low TY, Lian Q, Lee CN, Mitchell W, El Oakley RM, Lim SK. Elucidating the secretion proteome of human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1680–1689. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600393-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ceradini DJ, Kulkarni AR, Callaghan MJ, Tepper OM, Bastidas N, Kleinman ME, Capla JM, Galiano RD, Levine JP, Gurtner GC. Progenitor cell trafficking is regulated by hypoxic gradients through HIF-1 induction of SCF-1. Nat Med. 2004;10:858–864. doi: 10.1038/nm1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Forte A, Finicelli M, Mattia M, Berrino L, Rossi F, De Feo M, Cotrufo M, Cipollaro M, Cascino A, Galderisi U. Mesenchymal stem cells effectively reduce surgically induced stenosis in rat carotids. J Cell Physiol. 2008;217(3):789–799. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mattsson J. Recent progress in allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2008;10:343–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhuo M. Neuronal mechanism for neuropathic pain. Mol Pain. 2007;3:14. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jasmin L, Rabkin SD, Granato A, Boudah A, Ohara PT. Analgesia and hyperalgesia from GABA-mediated modulation of the cerebral cortex. Nature. 2003;424(6946):316–320. doi: 10.1038/nature01808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Neugebauer V, Galhardo V, Maione S, Mackey SC. Forebrain pain mechanisms. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60(1):226–242. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fuccio C, Luongo C, Capodanno P, Giordano C, Scafuro MA, Siniscalco D, Lettieri B, Rossi F, Maione S, Berrino L. A single subcutaneous injection of ozone prevents allodynia and decreases the over-expression of pro-inflammatory caspases in the orbito-frontal cortex of neuropathic mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;603(1–3):42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Galvin KA, Jones DG. Adult human neural stem cells for autologous cell replacement therapies for neurodegenerative disorders. NeuroRehabilitation. 2006;21:255–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Klass M, Gavrikov V, Drury D, Stewart B, Hunter S, Denson DD, Hord A, Csete M. Intravenous mononuclear marrow cells reverse neuropathic pain from experimental mononeuropathy. Anesth Analg. 2007;104(4):944–948. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000258021.03211.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Decosterd I, Woolf CJ. Spared nerve injury: an animal model of persistent peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain. 2000;87(2):149–158. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00276-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]