Abstract

Reverse transcription is a critical step in the life cycle of all retroviruses and related retrotransposons. This complex process is performed exclusively by the retroviral reverse transcriptase (RT) enzyme that converts the viral single-stranded RNA into integration-competent double-stranded DNA. Although all RTs have similar catalytic activities, they significantly differ in several aspects of their catalytic properties, their structures and subunit composition. The RT of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1), the virus causing acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), is a prime target for the development of antiretroviral drug therapy of HIV-1/AIDS carriers. Therefore, despite the fundamental contributions of other RTs to the understanding of RTs and retrovirology, most recent RT studies are related to HIV-1 RT. In this review we summarize the basic properties of different RTs. These include, among other topics, their structures, enzymatic activities, interactions with both viral and host proteins, RT inhibition and resistance to antiretroviral drugs.

Keywords: Reverse transcription, Retroviruses, DNA and RNA-dependent DNA synthesis, Ribonuclease H, RT inhibitors, HIV, Drug resistance

Historical perspective and overview

The breakthrough discovery of reverse transcriptase (RT) by Temin and Baltimore in 1970 had an immense impact on life sciences. The identification of a previously unknown new enzyme, an RNA-dependent DNA polymerase in RNA tumor viruses, has markedly challenged the prevailing central dogma, according to which, the genetic information flows from DNA to RNA and subsequently to proteins (or in the case of RNA viruses from RNA to RNA and proteins). Since the new enzyme transcribes nucleic acids from RNA to DNA, which was considered at that time “in reverse” to the existing dogma, it was dubbed “reverse transcriptase.” Following studies showed that RT had in fact three activities: an RNA-dependent DNA polymerase (RDDP), a DNA-dependent DNA polymerase (DDDP) as well as a ribonuclease H (RNase H) that cleaved the RNA strand of an RNA-DNA heteroduplex. As all RT activities could not have been described by a simple designation, the original name of the enzyme was kept. Accordingly, the RT-harboring viruses that were initially called “RNA tumor viruses” were renamed as “retroviruses.” Later on, the retrovirus-related movable elements were also discovered and termed “retroelements” and “retrotransposons” [1–3].

The discovery of RT enabled also a substantially better understanding of malignant transformation that is induced by RNA tumor viruses (retroviruses). A major mechanism suggested for this process was the ability of some retroviruses to acquire a cellular proto-oncogene during reverse transcription (RTN) [1]. RT is also required for the mobility of retroelements into new positions that may be upstream to cellular proto-oncogenes. Both processes can induce cellular genetic changes and may lead to malignancies. Historically, the first oncogenes were discovered as part of the genetic material carried by retroviruses.

During the last decades, RT has become a key tool in molecular biology, for the synthesis of complementary DNA (cDNA) from messenger RNA (mRNA). This application has largely expanded our knowledge of numerous cellular regulatory mechanisms. Moreover, combining RT activity with PCR amplification has long become a gold standard as the first step in cloning the coding region of any gene of interest. Evidently, RTs have been critical in advancing molecular biology, genetics and medicine to their current stage. Even nowadays, the development of biotechnology heavily relies on the availability of efficient RTs, in applications, such as the microarrays of reverse transcribing mRNA that are then analyzed by high throughput techniques.

A revival of RT research was triggered by the discovery, in the early 1980s, of a new human retrovirus that was later named human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the pathogenic agent of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in humans [1, 3, 4]. Evidently, the already-known information on retroviruses and RTs has helped enormously in identifying and rapidly advancing the studies of this novel human pathogen. High rates of morbidity and mortality in AIDS patients have directly led to a massive search towards antiretroviral interventions that identified HIV RT as a prime target for virus inhibition. To achieve this aim, an intensive research of HIV RT has been conducted. Indeed, azidothymidine (AZT, or zidovudine by its commercial name), which effectively inhibits the DNA polymerase activity of HIV-1 RT, was the first anti-retroviral drug used (in 1987) to treat HIV-1 carriers. Since then, RT inhibitors have been a major component in the drug combinations used to combat HIV-1. In addition, numerous HIV-1 RT drug-resistant mutations were characterized and extensively studied. This translated into a huge number of publications on the different functions and structures of RTs that turn RT altogether to one of the most studied enzymes.

The enormous potential of reverse transcription processes to affect cell and developmental biology, human genetics and medicine has been recently revealed after sequencing the entire human genome. It is now estimated that nearly 50% of all sequences found in this genome were initially introduced through RTN. Moreover, about 8% of the human genome is composed of endogenous retroviruses.

Due to its outstanding importance, several review articles (for example, [5, 6]) as well as special issues and books (e.g., [1–3]) have been dedicated to RT. In this review, we summarize the functions and structures of different RTs, with a concise and up-to-date description of the major topics surrounding them. As most recent studies on RTs were performed with HIV-1 RT, it will be considered in this review as the prototype RT, and, whenever it is not otherwise stated, we will refer to this RT. Obviously, cardinal contributions were also made prior to the identification of HIV in studies performed with other RTs, mainly those of murine leukemia virus (MLV) and avian sarcoma/leukemia virus (ASLV). A detailed review, written by us, that summarizes the unique properties of RTs other than those of HIV-1 and MLV can be found in the recent special issue dedicated to reverse transcriptase [7].

Introduction

Retroviruses have evolved by selecting a complex and unique strategy to replicate inside target cells. Upon entry into the host cell, the viral single-stranded RNA is copied in the cell cytoplasm by the viral RT into a double-stranded linear viral DNA molecule. Subsequently, the generated DNA is translocated into the nucleus, where it is inserted into the host genome by the retroviral integrase (IN). The integrated viral DNA, designated provirus, can then direct the synthesis of both viral genomic RNA (to be packed in the viral progeny) and viral mRNA species, required for synthesizing all viral proteins. The different RNAs are exclusively synthesized by the host DNA-dependent RNA polymerase II. However, in order to use the synthesized genomic RNA in the next round of infection, RT has to overcome a substantial obstacle. The synthesis of genomic RNA does not transcribe the viral promoter, located at the 5′-end of the long terminal repeat (LTR) of the provirus and the synthesized sequences beyond the poly(A) signal (at the 3′-end LTR) are removed during processing of the mRNA, similar to all other cellular mRNAs (see below and Fig. 2). As a result, the viral RNA genome contains only partial LTR sequences at both ends. These sequences must be extended during the generation of the proviral DNA in the next round of infection to contain the regulatory elements required for transcription and processing of the viral mRNA (Fig. 2). For that reason, retroviral RTs have evolved to assemble these regulatory elements during RTN by duplicating viral sequences found within their RNA genome, and, therefore, their activity is much more complex than simply copying the viral RNA. Generation of the double-stranded DNA is done in several steps. Initially, the RDDP activity copies the viral RNA template into the complementary (−) DNA strand. Concomitantly, the RNA strand of the nascent RNA-DNA heteroduplex is hydrolyzed by the inherent RNase H activity of RT. This is followed by DDDP activity that synthesizes the second (+) DNA strand, using the already synthesized (−) DNA strand as a template. These three interconnected activities enable the transfer of the genetic data stored in the viral genome into a double-stranded DNA and the assembly of the LTR regulatory elements in both sides of the double-stranded viral DNA.

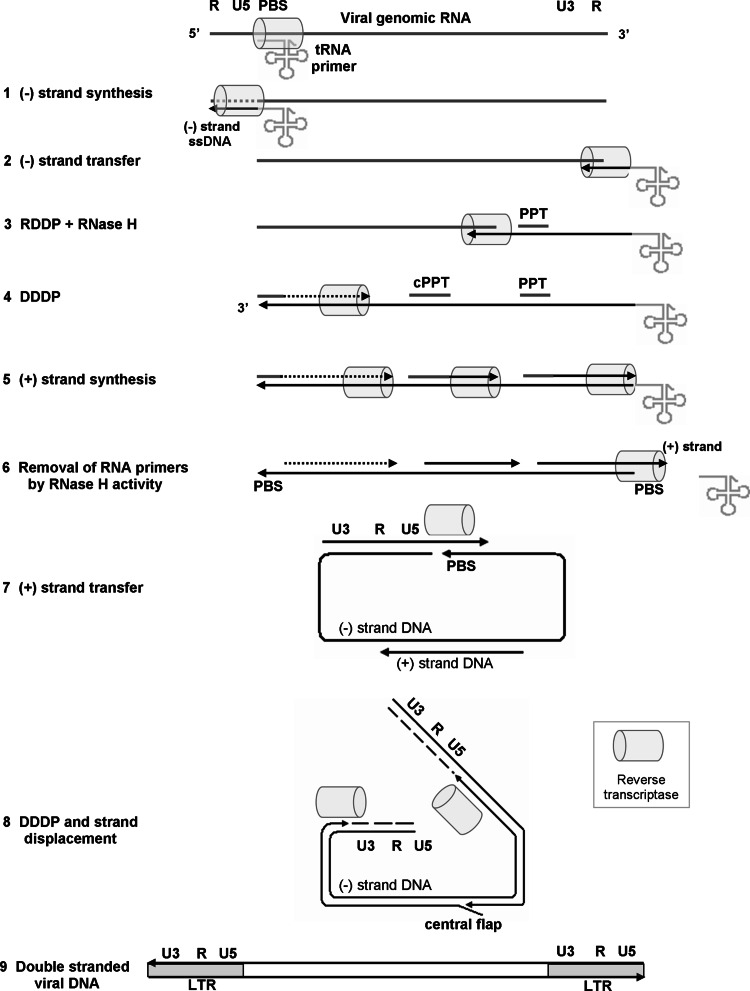

Fig. 2.

The reverse transcription process. A schematic description of the different steps of the RTN process, drawn not to scale. See the text for a detailed description. RNA is depicted in grey and DNA in black. The direction of DNA synthesis is marked by the arrowheads. In various retroviruses (+) DNA synthesis can potentially be initiated from multiple RNA primers. The initiation of (+) DNA synthesis from the cPPT and 3′-PPT is shown in this scheme as straight black arrows (step 7), as these are the main initiation sites of the RTN of HIV-1. An additional potential site is shown upstream as a dotted arrow

Biogenesis of RTs

Retroviruses can be subdivided into several groups (genus) according to their evolutionary relatedness (Table 1). All groups carry the gag, pol and env coding domains, whereas the complex retroviruses (such as the lentiviruses and deltaretroviruses) carry additional genes that partially overlap the former genes and encode (after alternative splicing of the mRNAs) small regulatory proteins. The RT sequences reside within the pol coding domain. RTs from the different groups of retroviruses share similar activities but can differ in various parameters, such as: structure and subunit composition, molecular weights, catalytic properties, biochemical and biophysical characteristics and sensitivity to different inhibitors [1, 2, 7].

Table 1.

Subunit organization of RTs from various groups of retroviruses

| Genus | Representative virus | RT | Additional viruses | Genomea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subunit organization | Putative size (kDa) | ||||

| Alpharetroviruses | ASLV | Heterodimer (the larger β-subunit contains also IN) | 94/62 | RSV, AMV | Simple |

| Betaretroviruses | MMTV | Monomer | 66 | MPMV | |

| Gammaretroviruses | MLV | Monomer | 75 | PERV | |

| Deltaretroviruses | BLV | Monomer | 64 | HTLV-1 | Complex |

| Lentiviruses | |||||

| Primate | HIV-1 | Heterodimer | 66/51 | HIV-2, SIV | |

| Non-primate | BIV | Heterodimer | 64/51 | EIAV, FIV | |

| Spumaviruses | HFV | Monomer | 80–81 | BSV | |

Epsilonretroviruses were omitted due to limited available data

aA simple genome, as in all orthoretroviruses, contains the gag, pro,pol and env genes, encoding for viral proteins. The complex genome of the other groups encodes in addition several viral regulatory proteins

RSV Rous sarcoma virus, AMV avian myeloblastosis virus, MPMV Mason-Pfizer monkey virus, HFV human foamy virus, BSV bovine syncytial virus [1]

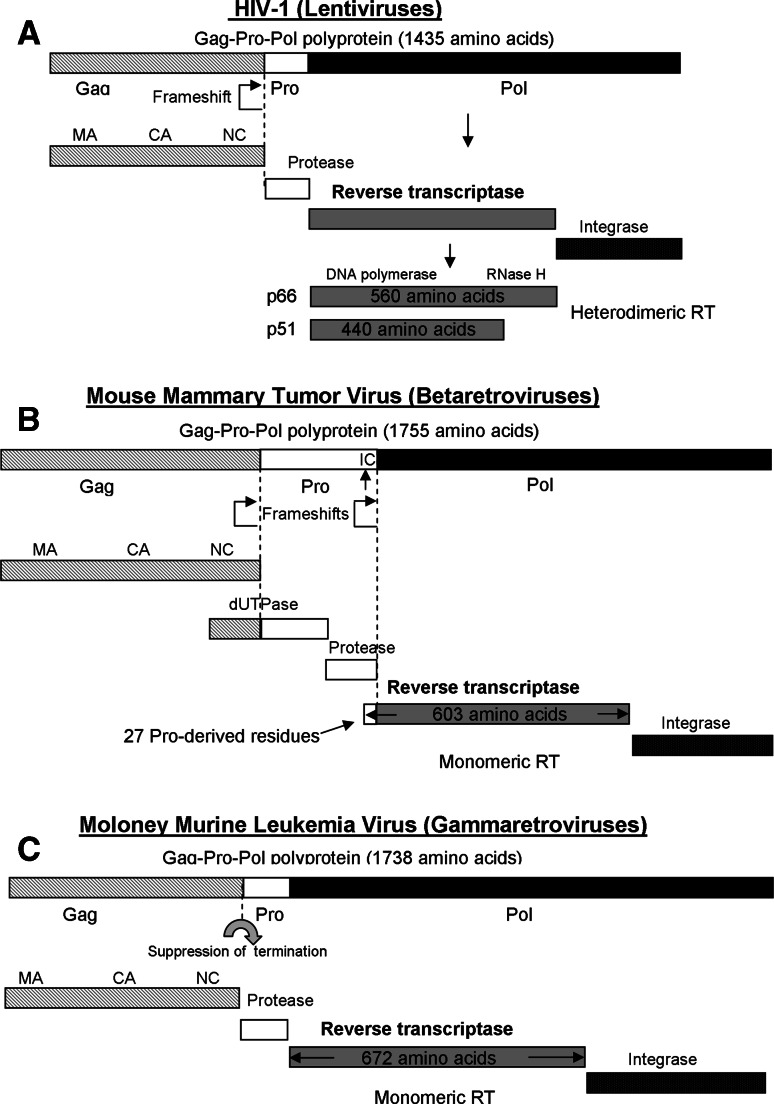

In all retroviruses, the viral pol gene encodes the Pol precursor protein that consists both RT and IN proteins. The fused protein is synthesized as part of a larger Gag-Pro-Pol polyprotein, from which the mature RT and IN proteins are cleaved out during virus assembly by the viral protease (PR) (encoded by the pro gene) (Fig. 1). Although the order of the gag, pro, pol and env genes is invariant in retroviruses, their reading frames are quite different. The Gag and Gag-Pro-Pol polyproteins are translated from identical mRNA, but in the latter there is either a termination suppression or a frameshift by one nucleotide (−1 frameshifting) that tightly regulates the ratio of Gag to Gag-Pro-Pol synthesis. In the most common organization, epitomized by lentiviruses, the pro and pol are in the same reading frame, and synthesis of Gag-Pro-Pol requires only a single frameshift event relative to the gag reading frame. As a result, the PR, RT and IN proteins are in equimolar ratios, and the amount of each is about 20-fold less than the amount of the Gag molecules. In ASLV (an alpharetrovirus) there is also a single −1 frameshift event before the pol gene; therefore, the pro gene is in the same reading frame as gag. Therefore, Pro is synthesized as part of the Gag polyprotein, and the ratio of PR to Pol is much higher compared to lentiviruses (where they are in equimolar ratios). A different arrangement of two consecutive frameshifting-associated events exists in mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) (a betaretrovirus) and in human T-cell leukemia virus-1 (HTLV-1) or bovine leukemia virus (BLV) (both are deltaretroviruses). In this case, the pro gene, which stands in its own reading frame, is in a −1 reading frame relative to gag, and the pol gene is in a −1 reading frame relative to the pro gene (Fig. 1). Frameshifting at each site is relatively efficient, with up to 30% of the translations, to ensure that a sufficient level of the final Gag-Pro-Pol polyprotein is made after the two serial shifts. Interestingly, an entirely different frameshift-independent arrangement is found in MLV (epitomizing gammaretroviruses), where the pro and pol genes are in the same reading frame as gag, but are separated by a stop codon (Fig. 1). The synthesis of Pro and Pol proteins is a product of an in-frame read-through suppression of the termination codon at the end of the gag gene. Frameshifting and read-through have probably evolved as strategies to provide the proper ratios of Gag, Gag-Pro and Gag-Pro-Pol polypeptides in the infected cell. Fusion of the viral enzymes to the Gag polyprotein also provides a means for incorporating these enzymes into the new progeny virions during assembly. Finally, spumaviruses (foamy viruses) markedly differ from all other previously described retroviruses, which are termed collectively orthoretroviruses. The RT of spumaviruses is generated from a separate spliced mRNA instead of the Gag-Pro-Pol polyprotein precursor, and infectious particles contain double-stranded DNA, similar to full length cDNA of the orthoretroviruses (see below). This suggests that RTN of spumaviruses takes place during the packaging of viral particles and before the virions enter the new target cells in a process reminiscent of the life cycle of hepadnaviruses [7–9].

Fig. 1.

The biogenesis of RTs in selected retroviral groups. Retroviral RTs are cleaved from the Gag-Pro-Pol polyprotein precursor. In lentiviruses the Gag-Pro-Pol polyprotein is synthesized after a single translational frameshift event. a In HIV-1, the resulting RT, which is cleaved from the polyprotein, is a heterodimer with the molecular weight of p66/p51. b In MMTV, the Gag-Pro-Pol is generated by two subsequent events of translational frameshift. The resulting RT is a monomer with 603 amino acids, of which 576 derived from the pol gene and 27 from the C-terminal portion of the Pro protein. Therefore, there is a putative internal cleavage site (IC) at this position within the Pro. The Gag-Pro polyprotein is generated by a single frameshift event and may be also the source for all the Gag and Pro derived proteins. c MLV uses a completely different strategy in which the Gag-Pro-Pol polyprotein is generated by an in-frame suppression of the stop codon. In the case of MLV, the scheme shows the protein lengths of the Moloney strain. This schematic description was not drawn to scale

Despite the clear separation between the pro and pol genes, there are some variations in the processing of RT by PR in different retroviral groups. These differences affect the final assembly of the proteins, the sequences incorporated into RTs and their molecular arrangements and structures. All known RTs are either monomeric or heterodimeric in structure, as summarized in Table 1. The smaller subunit in the heterodimeric RTs is produced by a proteolytic cleavage of the larger subunit. This activity removes the C-terminus of the large subunit that usually corresponds to the RNase H domain of RT. However, in alpharetroviruses, such as ASLV, the larger subunit (designated β) is a fused RT-IN polypeptide, while the shorter one (designated α) lacks the IN sequences but still retains the RNase H domain. In ASLV virions a free enzymatically active IN is also found [1, 7]. Generation of heterodimeric RT requires cleavage of the Gag-Pro-Pol polyprotein to liberate the large subunits of RT that are then associated into a homodimeric protein (e.g., p66/p66 in the case of HIV-1 RT and β/β in ASLV). A further PR-directed processing yields the final heterodimeric RT versions of p66/p51 and β/α in these two retroviruses, respectively [7, 10, 11]. Interestingly, several isoforms of RT can be found in ASLV virions including the major “mature” β/α, the β/β and the monomeric α isoforms, all of which are fully active, with some notable differences in their enzymatic activity [12, 13]. In HIV-1 RT, only minor differences were reported between the catalytic activities of p66/p51 versus p66/p66 isoforms [14, 15], whereas the p51 subunit by itself is nearly devoid of any enzymatic activity [16].

All monomeric RTs (e.g., those of gammaretroviruses or betaretroviruses) have both DNA polymerase and RNase H domains, and their N-terminal may contain, in some cases, residues from the upstream PR protein. In MMTV the approximately 27 residues that appear at the C-terminus of PR are also present in the RT enzyme (Fig. 1) [17, 18]. This means that cleavages at alternative sites in Gag-Pro-Pol liberate either the full length PR or RT, and the 27-residue segment has a dual function as both the C-terminus of the PR and the N-terminus of RT. In BLV RT, the N-terminal 26-residue segment of RT is also derived from the pro gene (in the second reading frame). However, in this case, the mature PR ends upstream to the 3′-end of the pro gene, and there are not any overlapping sequences between RT and PR [7]. The rest of the BLV RT sequence is derived from the pol gene after −1 frameshifting into the third reading frame [7, 19].

The process of reverse transcription

RTN is initiated after the association of RT with genomic viral RNA and a primer. The primer is required for copying the template RNA by all RTs, and, in most cases, DNA synthesis is initiated from a transfer RNA (tRNA) primer that is supplied by the host cell. A tRNAlys3 is used by lentiviruses and betaretroviruses, tRNApro by gammaretroviruses and tRNAtrp by alpharetroviruses. The tRNA contains 18 nucleotides (nts) at its 3′-end that are complementary to the primer binding site (PBS), located close to the 5′-end of the viral RNA genome (in HIV-1, the PBS is located 180 nts from this end). This enables the hybridization of the tRNA to the PBS [1, 20, 21] (see Fig. 2). In rare cases, as in the LTR retrotransposon Tf1, priming is tRNA-independent and results from an 11-nt self-complementarity between the sequence, located at the 5′-terminus of the genomic RNA and the PBS located further downstream. In this instance, the RNA is nicked at the 3′-end of the primer by the RNase H activity of Tf1 RT, to generate a functional 11-nt self-primer for DNA synthesis [22, 23].

RTN catalyzed by all LTR retroelements and retroviruses is initiated by the synthesis of the first (−) DNA strand that is complementary to the viral (+) strand RNA genome. This synthesis starts by extending the 3′-OH terminus of the RNA primer (either tRNA or self-primer) while copying the 5′-end of the viral RNA genome that contains the unique 5′-end sequence (U5) and the 5′-end repeat (R) region (Fig. 2, step 1). The synthesized DNA strand and the viral RNA produce an RNA–DNA hybrid in which the RNA strand is then hydrolyzed by the RT-associated RNase H activity. This activity, which utilizes the DNA 3′-end-directed cleavage mode to hydrolyze the RNA (see below), leaves the nascent (−) DNA strand as single stranded that is designated (−) strand strong stop DNA (sssDNA). Nonetheless, the RTs of HIV-1 and MLV cleave on average only once for every polymerized 100–120 nts that is insufficient to completely hydrolyze the RNA. Therefore, multiple internal cleavages are probably required to generate gaps that allow a further degradation by the RNA 5′-end-directed mode of RNase H cleavage [1, 2, 24, 25] (see below). The generated (−) sssDNA segment contains a sequence that is complementary to the identical repeat (R) sequences, located at both the 5′ and 3′ -ends of the viral RNA genome (Fig. 2). The length of the R region varies in different retroviruses and ranges from 12 nts (in MMTV) to 235 nts (in BLV), with 98 nts in HIV-1 and 68 nts in MLV [1, 2]. As a result of the duplicated R regions, the (−) sssDNA can hybridize to the R sequences, located at the 3′-end of the viral RNA molecule. Since there are two such RNA molecules in each virion, this template switching step, or first (−) strand transfer (Fig. 2, step 2), can be either intermolecular, by switching to the second RNA molecule, or intramolecular, by switching to the other end of the same RNA molecule. Evidently, these two alternative switches occur at similar frequencies during (−) strand transfer [26, 27]. Interestingly, (−) strand transfer can occur before the synthesis of the (−) sssDNA has been completed. After the nascent DNA hybridizes to 3′-end R region (−) strand DNA synthesis proceeds along the viral RNA, while the RNase H concomitantly degrades the already copied RNA (Fig. 2, step 3).

Most cleavages by RNase H are not sequence-specific; however, specific purine-rich sequences (designated poly-purine tracks, PPTs) show high resistance to RNase H hydrolysis. The major PPT, which is located close to the 3′ end of the viral RNA (hence designated 3′ PPT) and is quite diverse in different retroviruses, serves as a major primer for the second (+) strand DNA synthesis after removing other RNA sequences [28]. Nevertheless, other RNA segments that are left after partial RNA degradation can also serve as minor primers for (+) strand DNA synthesis [2, 6] (Fig. 2, step 4 and 5). Thus, although all retroviruses initiate (+) strand synthesis using the 3′ PPT as a primer [28], some retroviruses, such as HIV-1, equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV), feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) and ASLV, as well as the retrotransposon Ty1, begin (+) strand DNA synthesis from additional RNA priming sites. The most notable site for a second PPT is located in the center of the viral genome in the IN-encoding sequence and termed central PPT (cPPT) [2, 29, 30]. Potentially, all (+) DNA versions, which are primed by different RNA segments, may play some roles in the following steps of RTN (Fig. 2, steps 4 and 5).

Synthesis of (+) DNA strand continues until RT starts copying the tRNA primer (Fig. 2, step 5). The first 18 nts at the 3′-end, which are complementary to the viral PBS, are copied by RT, but the next nucleotide in the tRNA is a modified “rA” and cannot serve as a template for DNA synthesis. The synthesized DNA strand and the 3′-end of the tRNA generates a new RNA-DNA hybrid that can serve as substrate for the RNase H activity. In most retroviruses, the RT-associated RNase H removes the complete tRNA segment, while in HIV-1 the RNase H activity of RT cleaves exactly one nucleotide from the junction between tRNA and DNA, thus leaving an extra “rA” at the 5′ end of the (−) DNA strand. The newly formed second DNA strand is designated (+) strand strong stop DNA (sssDNA).

At this stage, the R region, the U5 sequence and the unique viral RNA sequence, located at the 3′-end (U3), have been brought all together to form the 3′ LTR of the (+) strand DNA (Fig. 2, step 6). The (+) strand is discontinuous and is annealed to nearly a full length (−) DNA strand. Subsequently, a second template switch, or second (+) strand DNA transfer, is catalyzed by RT. This strand transfer is mainly intramolecular [26] and is mediated by annealing of the single-stranded DNA form of the PBS sequence, located at the (+) sssDNA, to the complementary region at the 3′ of the (−) DNA (Fig. 2, step 7). This results in the transfer of the 3′-end of the (+) DNA strand to the 3′-terminus of the (−) DNA strand, or the generation of a circular DNA molecule. Once the second transfer occurs, both DNA strands can be further extended by the DDDP activity of RT (Fig. 2, step 8). DNA synthesis may require the strand displacement activity of RT to remove annealed DNA strands (Fig. 2, step 8, and see below) or possibly may involve the DNA repair activity of host cell enzymes. The complete process eventually leads to a full length, integration-competent, double-stranded DNA with two identical LTRs, one at each end.

Further analysis of unintegrated retroviral DNA in cells infected by different retroviruses has suggested that the generation of the full length (+) DNA strand during RTN may have additional complexities. Both MLV and MMTV appear to have large gaps in their (+) DNA strand. In contrast, (+) DNA strand of HIV-1 contains a central DNA tail or flap in which there are two overlapping (+) strand segments. Such an element is created after the second strand transfer, when (+) strand DNA synthesis that was initiated at the 3′-end PPT proceeds downstream and partially displace an already synthesized (+) DNA strand extending from the cPPT (Fig. 2, step 8). During this process, the cPPT-extended DNA strand is dislocated by the strand displacement activity of RT to allow synthesis of DNA and generation of the flap. The DNA flaps are more abundant in ASLV (+) strands and may also facilitate recombination between two genomic viral RNAs (see below). The size and position of the DNA flaps are determined by the site of DNA initiation and a specific termination sequence located further downstream. The position of this termination sequence in HIV-1 creates a DNA flap (88 or 98 nts-long) that is located downstream to the cPPT, while in Ty1 the flap is up to 130 nts. The viral nucleocapsid (NC) protein (see below) increases the rate of DNA synthesis, as it was suggested that this protein stabilizes structural fluctuations within the central flap [30]. One theory suggests that the central flap is required to introduce flexibility into the center of the DNA duplex, thus helping with the formation of a pre-integration complex (PIC). The PIC, which is composed of the fully complete linear double-stranded viral DNA, the viral proteins, RT, IN, NC, viral protein R (Vpr) and cellular proteins, undergoes nuclear localization in non-dividing cells [31, 32]. Nevertheless, the importance of this single-stranded central flap is yet not fully settled, as an HIV-1 mutant that carries a disrupted central DNA flap can be still pathogenic in vivo [33, 34]. In addition, altering the central flap had little effect on the efficiency of nuclear localization of the PIC [35].

There are still several additional complexities in the RTN process, and we will further highlight some of them. Since the viral DNA, synthesized during RTN, is a substrate for integration by IN, the ends of the linear viral DNA must be reasonably accurate. The RNase H cleavage of the tRNA primer defines the U5 end, and the removal of the PPT primer defines the U3 end of this DNA. Although the RNase H activity does not usually recognize specific sequences, it performs these particular cleavages with a high accuracy; therefore, the ends of the linear viral DNA are well defined to the precise nucleotide. The presence of two identical (or almost identical in case of mutations) copies of the viral RNA genome in each virion may also be important for productive infections. Such a virion can survive even if one of the RNA molecules contains single breaks, as RTN that was initiated on this strand can proceed by transferring the nascent DNA to the second RNA template (by a mechanism designated forced strand transfer, see below [36]). Theoretically, when two copies of the RNA genome are present, a complete DNA copy can be made even if both RNA molecules are extensively nicked, provided that there are no identical nicked sites at both RNA molecules. The effects on genetic recombinations might be another possible reason for the presence of two RNA copies. In host cells that contain two different integrated proviral DNA genomes, virions with two related RNA genomes but with different sequences can be produced. Switches between these two RNA templates can then generate a recombinant genome that is composed of different segments of the two parental sequences. Evidently, in cells that contain only one integrated DNA genome, the two RNA copies will be identical (unless errors occur during transcription), and, therefore, template switches will not bear any noteworthy consequences. This may have fundamental consequences. For instance, as frequently happens in HIV-1, recombination can lead to viruses that are resistant to multiple drugs, in contrast to the parental viruses that are resistant to just a single drug.

The three-dimensional structure of RTs

As described above, three enzymatic activities of RTs are required to generate the double-stranded DNA from the viral single-stranded RNA genome. DNA synthesis generates either the (−) or (+) viral DNA, whereas RNA degradation removes both the viral RNA and the tRNA initially used for priming the (−) DNA strand [1, 2]. To enable parallel, multi-functional activity during the RTN process, RT must adopt a well-defined structure in solution. Similar to the structures of all studied DNA polymerases, the DNA polymerase domain of all studied RTs forms a structure resembling a right hand conformation that is linked to the C-terminal RNase H domain (Fig. 3). Both catalytic domains are spatially separated. The polymerase domain of RTs can be further divided into fingers, palm, thumb and connection subdomains (the connection is linked to the RNase H domain), each having a unique role in nucleotide incorporation during DNA synthesis. Most of our knowledge on structural features of RTs is based on the many crystal structures of HIV-1 RT, both the wild-type protein and drug-resistant mutants. Many of these studies determined the crystal structures of HIV-1 RT in complex with the DNA–RNA substrate and/or with RT inhibitors. Additional information is available from a few crystal structures of HIV-2 RT and MLV RT, thus allowing the comparison of structures from different RTs in order to highlight structural elements common to all RTs.

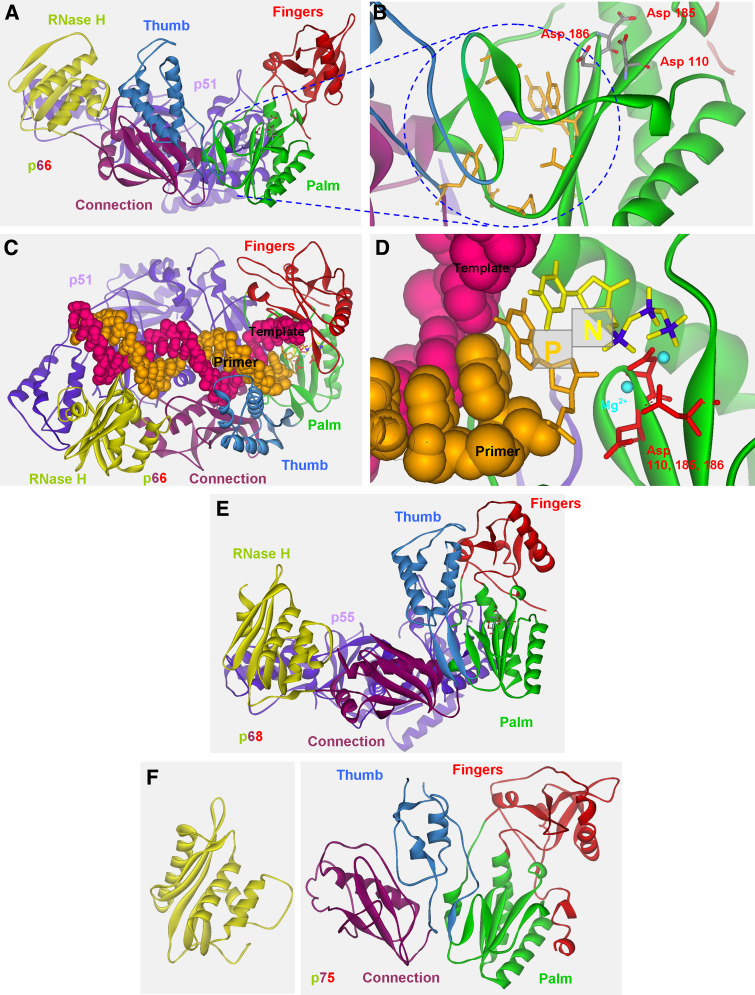

Fig. 3.

The 3-dimensional structures of HIV-1, HIV-2 and MLV RTs. a Spatial structure of wild-type HIV-1 RT (PDB entry 1FK9) with its defined subdomains. HIV-1 RT was co-crystallized with the inhibitor efavirenz and is displayed from the side view after removing the inhibitor. b Magnification of the NNRTI hydrophobic pocket from a along with the three aspartic acids that form the catalytic site of the DNA polymerase domain. a, b Adapted with permission from Herschhorn et al. [201]. c The catalytic complex of HIV-1 RT together with a primer-template and dTTP (PDB entry 1RTD) from a top view. RT is displayed as solid ribbon, the template-primer as CPK (Corey, Pauling, and Kultin), and the 3′ nucleotide of the primer as well as the dTTP are displayed as a stick model. d Magnification of the N and P sites (marked as N and P) adjacent to the DNA polymerase sites from c and their position in relation to the three Asp catalytic residues. In c and d a hydroxyl was added to the 3′ position of the ribose in the P site to illustrate the presence of dNTP during DNA synthesis (the original complex was co-crystallized with ddNTP nucleotide). e The structure of HIV-2 RT (PDB entry 1MU2). f The structure of MLV RT was resolved in detail as two fragments, one for DNA polymerase domain (PDB entry 1RW3, right side) and the second for the RNase H domain (PDB entry 2HB5, left side). In all panels, the fingers subdomain is depicted in red, palm subdomain in green, thumb subdomain in light blue, connection subdomain in purple and RNase H domain in yellow (all of the large subunit or the only subunit in the case of MLV). All structures were displayed with Accelrys Discovery Studio Visualizer v1.6 (Accelrys Software Inc.)

HIV-1 RT

HIV-1 RT is an asymmetric heterodimer that is composed of two subunits. The larger p66 subunit is 560 residues long and exhibits all the enzymatic activities of RT. The DNA polymerase domain of HIV-1 RT adopts in solution the right hand conformation with four defined subdomains [37]. The fingers are located at residues 1–85 and 118–155, the palm at residues 86–117 and 156–236, the thumb at residues 237–318, and the connection to the RNase H is located at residues 319–426 [37, 38]. The RNase H domain extends approximately beyond residue 440. The smaller p51 subunit is about 440 residues long and is identical to the N-terminal portion of the p66. The p51 is cleaved from a p66 subunit by the viral PR after association of two p66 subunits to generate p66/p66 homodimers [11] (see above). For the most part, the p51 subunit stabilizes the heterodimer but may also participate in binding the tRNA primer [1, 2]. This subunit can also affect the RNase H activity [39, 40]. The fingers, palm, thumb and connection subdomains in the p51 subunit (except for the C-terminus of the connection, [1]) fold similarly to the corresponding subdomains in the p66. However, the spatial organization of each subdomain relative to the others differs substantially in the two RT subunits [37]. As a result, p51 is more tightly packed, with the connection rotated to cover the palm and displacing the thumb [1]. Interestingly, though the sequence of p51 is identical to the N-terminal portion of p66, the tertiary structures of the two subunits are considerably different. This unique case shows that similar primary and secondary structures do not necessarily lead to similar tertiary protein structures.

All p66 subdomains, along with the thumb and connection subdomains of p51, participate in binding the nucleic acids, but the RNase H domain plays only a minor role in this binding. The connection subdomains of both subunits, together with the thumb of the p51 portion, form the “floor” of the binding cleft [38]. HIV-1 RT binds the nucleic acid substrate in a configuration that places the substrate in direct contact simultaneously with both the DNA polymerase and RNase H active sites. The distance between the two active sites is about 60 Å [41]. This allows positioning the substrate so that 17 nts (for DNA–DNA) or 18 nts (for RNA–DNA) separate the two sites on the nucleic acid substrate. DNA synthesis is an ordered reaction in which RT first binds its primer-template substrate and places the 3′-OH group of the primer terminus at the priming site (P site) that is located next to the polymerase active site (Fig. 3) [38, 42]. Comparison of crystal structures of the unliganded RT with structures of RT bound to its nucleic acid substrate shows that the binding results in a change of the position of the p66 thumb from “close” to “open” conformation [43, 44]. The flexibility of the thumb allows movements from the “close” position, in which the thumb touches the tip of the fingers to the “open” position, in which the thumb moves about 30° away from the fingers. A contradictory report observed a conformation similar to the “open” state for the unliganded RT, but this was probably due to growing the RT crystals with a weakly binding non-nucleoside RT inhibitor (NNRTI) that was later soaked out from the crystal [45]. The conformational change associated with binding to the primer template is followed by a second binding of a dNTP to the nucleotide binding site (N site) to form a ternary complex (Fig. 5) [42]. The active site environment facilitates the trans-esterification reaction that leads to the incorporation of the incoming dNTP into the primer (see below). The nucleic acid substrate must then translocate relative to RT to free the N site for the next dNTP. Accordingly, RT is actually moving along the nucleic acid substrate and adding the next nucleotide in each cycle of processive synthesis.

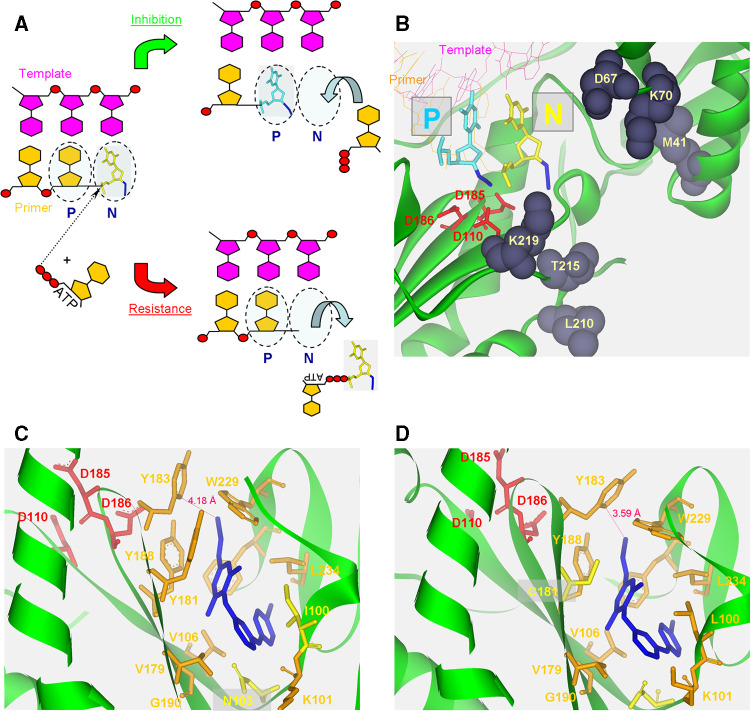

Fig. 5.

HIV-1 RT inhibitors and drug-resistant RT mutants. a Incorporation of AZT-TP into the nascent DNA strand by HIV-1 RT can lead to two alternatives. Translocation of the incorporated NRTI into the P site (P) may be followed by binding of the next dNTP to the N site, resulting in the formation of a dead-end complex and inhibition of any further DNA synthesis. Conversely, excision of the chain terminator, AZT-MP, which is mediated by ATP as a pyrophosphate donor, releases the incorporated NRTI and consequently reverses inhibition. b The three-dimensional structure of the incorporated AZT-MP at the end of the primer at either the N site (N, yellow) or the P site (P, cyan). The pre- and post-translocation structures of HIV-1 RT are from PDB entries 1N6Q and 1N5Y, respectively. The coordinates of AZT-MP at the P site were taken from the post-translocation structure and were used to insert this molecule into the pre-translocation structure. This was done to indicate the general orientation of AZT-MP, and it does not necessary represent the exact position of AZT-MP in the P site. Residues that are associated with increased resistance to AZT are displayed in CPK style and are labeled. The primer and template are displayed in line style and the AZT-MP in stick style (yellow for the N site and cyan for the P site). HIV-1 RT is displayed as a solid ribbon in green. c, d The hydrophobic pocket of HIV-1 RT that binds NNRTIs in two structures of RT mutants. HIV-1 RTs with different mutations, which are associated with resistance to classical NNRTIs, were co-crystallized with the TMC278 NNRTI, a broad-range inhibitor of many mutant RT variants. The double mutant L100I + K103N is shown in (c) and the double mutant K103N + Y181C in (d). The highly potent inhibitor is flexible and can accommodate and interact with different residue in different mutants. Inhibiting the K103N + Y181C double mutant is mediated at least partially by interacting with Y183 that leads to its movement and the repositioning by 1.5 Å in the conserved Y183 MDD [194]. Residues of the hydrophobic pocket are displayed in orange and the mutant ones in yellow. All residues are presented as stick model and labeled. The distance between Y183 and the cyano group of TMC278 in both structures is also shown. All structures were displayed with Accelrys Discovery Studio Visualizer v1.6 (Accelrys Software Inc.)

The DNA polymerase active site is composed of three highly conserved Asp residues at positions 110, 185 and 186, located within the palm subdomain of p66. The carboxylate moieties bind two metal ions, probably Mg+2 in vivo, facilitating the incorporation of new dNTPs into the primer. The precise alignment of the catalytic residues of RT, the 3′-OH group of the primer and the α phosphate of the incoming dNTP allows a nucleophilic attack of the 3′-OH on the α phosphate group, consequently liberating a pyrophosphate molecule that leaves the active site as the fingers open. Structural differences between the pre- and post-translocation complexes have shown that the conserved YMDD loop may act as a “springboard” during translocation to move the primer terminus from the N to the P site after dNMP incorporation [46]. There is also evidence that the pyrophosphate of the added nucleotide is released before translocation takes place [47, 48]. Specific roles in the polymerization reaction are associated with several defined regions and motifs within the DNA polymerase subdomains of HIV-1 RT. The catalytic Asp at positions 185 and 186 are also part of the YMDD motif of HIV-1 RT. This motif is highly conserved among RTs; however, the Met is replaced by Val, Leu or Ala in other RTs. The “primer grip” at the p66 β12–β13 (β-sheet12–β-sheet13, residues 227–235) hairpin in HIV-1 RT facilitates the exact position of the 3′-OH of the primer within the primer site [38]. The “template grip” at β4 (residues 73–77), αB (α-helix B, residues 78–83), β5a (residues 86–90) and the β8–αE (residues 141–174) connecting the loop portions of the p66 palm and fingers is closely associated with the template strand [1]. In addition, the β3–β4 loop is involved in many RT activities including processivity [49], fidelity of DNA synthesis [50] and strand displacement synthesis [51]. The helixes αH (residues 255–268) and αI (residues 278–286) of the p66 thumb extensively contact the primer template [38]. There are also several conserved residues in the N site of HIV-1 RT, including Tyr115, which facilitate deoxyribose ring binding of the incoming dNTP and functions as a steric gate discriminating between rNTPs and dNTPs (see below) [52–54], Arg72 and Lys64, which coordinate the triphosphate group of the incoming dNTP phosphates, and Gln151 that binds the 3′-OH of the incoming dNTP [42]. Many crystal structures of HIV-1 RT complexed with different NNRTIs demonstrate that the inhibitors bind a specific hydrophobic pocket, located about 10 Å underneath the catalytic active site of the DNA polymerase domain (Fig. 3). This pocket is rich in aromatic residues, such as Tyr188 and Tyr181, and will be discussed in detail below (in the section on inhibitors of RT and drug resistant RT variants).

The RNase H activity of HIV-1 RT degrades the RNA strand in the RNA-DNA heteroduplex during DNA synthesis. In addition to the removal of the template RNA and the primer tRNA, it also produces the PPTs for the (+) DNA strand synthesis and eventually hydrolyses them (see above) [55]. The structure of HIV-1 RT RNase H shows a high structural similarity to E. coli RNase H, most remarkably in the catalytic cores [56]. This is quite surprising, since the primary sequence identity between the two proteins is merely about 20% [1]. It should be emphasized that the specific activity of the bacterial enzyme is at least 100-fold higher than that of the complete retroviral RTs. Moreover, the isolated HIV-1 RT RNase H domain is by far less active than the intact RT molecule [57, 58]. This is probably due to the inherent low capacity of the RNase H to bind the primer-template substrate that is mostly bound during synthesis by the DNA polymerase domain. This suggestion is further supported by evidence that the activity of the isolated HIV-1 RNase H domain can be restored. Restoration of this activity can be accomplished by inserting a basic loop, present only in the bacterial RNase H and not in HIV-1 RNase H, into the isolated RNase H domain [59, 60]. Alternatively, the RNase H activity can be restored by mixing in trans the isolated HIV-1 RT RNase H domain with the polymerase domain of the same RT [61, 62] (see also below).

The HIV-1 RT RNase H domain folds into a five-stranded mixed beta sheet, flanked by four alpha helices. The active site is surrounded by a cluster of four conserved acidic residues: Asp443, Glu478, Asp498 and Asp549 [56]. In the original crystal, the acidic residues interacted with two Mn2+ ions located 4 Å from each other, but it is likely that in vivo both metal ions are Mg+2 [6]. The two metal ions are asymmetrically coordinated in the active site and have distinct roles in activating the nucleophile and stabilizing the transition state [55].

The co-crystals of HIV-1 RT, prepared with duplex DNA, showed that the DNA in the vicinity of the polymerase active site is more close in structure to an A-form helix, whereas the DNA near the RNase H site is more structurally close to a B-form, with an angle of about 40°–45° (forming a “kink”) between the helical axes of the two forms [38]. All three RNA-RNA, RNA-DNA and DNA-DNA duplexes are used during RTN and have to be properly positioned in the binding cleft. However, RNA-RNA duplexes cannot assume a B-form structure and, therefore, the DNA substrate in the DNA polymerase site may be constrained to assume the A form to give a relatively uniform structure to all template primers used for synthesis [1]. The nucleic acid structure near the RNase H site has a minor groove about 9 Å wide. This may contribute to the cleavage specificity of RT as substrates with narrower width are poorly cleaved. Cleavage specificity is also controlled by the RNase H primer grip. This structural element consists of several amino acids that interact with the DNA primer strand near the RNase H active site. The specific residues are: Lys395 and Glu396 of p51, Gly359, Ala360 and His361 from the p66 connection subdomain and Thr473, Asn474, Gln475, Lys476, Tyr501 and Ile505 from the p66 RNase H domain [41]. The amino acid distribution in several domains highlights the existence of tight cross interactions between residues located in different domains of HIV-1 RT (in this case, residues in the p51 subunit and residues in the DNA polymerase and the connection of the p66 subunit, affect the RNase H activity).

HIV-2 RT

Like HIV-1 RT and probably all other lentiviral RTs (for example, the RTs of FIV [63, 64], bovine immunodeficiency virus (BIV) [65] and EIAV [15, 66, 67]), HIV-2 RT is an asymmetric heterodimer composed of two subunits. The large p68 subunit, which is 559 residues long, is similar to the p66 of HIV-1 RT, whereas the smaller subunit (that was found in different studies to be either p55 or p54) is analogous to the HIV-1 p51 subunit. The amino acid sequence of HIV-2 RT shows a significant homology to the sequence of HIV-1 RT [68]. The smaller subunit of HIV-2 RT lacks the RNase H domain, similar to HIV-1 RT, and the remaining fingers, palm, thumb and connection subdomains are more tightly packed than there are in the p68 subunit. Interestingly, the HIV-2 RT smaller subunit, produced by HIV-2 protease, is 484 residues long, while the comparable p51 subunit of HIV-1 RT is only 440 residues long, resulting in a significantly longer connection subdomain in HIV-2 RT [69]. In contrast, the large subunits of HIV-2 and HIV-1 RTs differ in length by only a single residue (559 amino acids in HIV-2 RT and 560 in HIV-1 RT). The disparity in the processing of the large subunits of the two HIV RTs to form the smaller subunits is attributed to the distinct specificities of the two HIV proteases. Accordingly, bacterial proteases, with yet a different specificity, have produced a substantially shorter version of the small HIV-2 RT subunit that is only 427 residues long [70]. The structure of HIV-2 RT has the greatest similarity to the unliganded HIV-1 RT structure when comparing the different structures of HIV-1 RT. The thumb subdomain of p68 in unliganded HIV-2 RT is rotated by 8° relative to the unliganded HIV-1 RT [71]. HIV-2 RT also forms a more stable heterodimer than HIV-1 RT does [72].

The most significant structural differences between HIV-2 RT and HIV-1 RT are located in the NNRTI binding pocket, near the DNA polymerase active site (Fig. 3) [71]. The conformation of Ile181 in HIV-2 RT, instead of Tyr181 in HIV-1 RT, can contribute to the resistance of HIV-2 RT to many commonly used NNRTIs. In addition, residue 188, which is a Leu in HIV-2 and Tyr in HIV-1 RT, as well as the lack of the aromatic side chains at positions 181 and 188 of HIV-2 RT, abolish the effect of ring stacking interactions with many NNRTIs. Also, the positions of several conserved residues are modified in HIV-2 RT relative to HIV-1 RT and thus can further affect binding to inhibitors.

MLV RT

MLV RT represents a group of monomeric retroviral RTs that includes also the RTs of MMTV, BLV, porcine endogenous retrovirus (PERV) and of the LTR retrotransposon, Tf1 [7]. The crystal structure of the full length enzyme, which is composed of 671 residues (75 kDa), was determined at a 3 Å resolution [73] and provided the first resolved structure of a monomeric RT. To obtain suitable crystals for structure determination, Das et al. [73] had to improve the solubility of MLV RT by a deletion of the first 23 amino acids and by substituting Leu435 by a Lys residue. This MLV variant still retained full enzymatic activity and required for crystallization the presence of a 14 nts DNA duplex that is rich in A and T nucleotides. The single polypeptide contains the known polymerase subdomains: fingers, palm, thumb and connection, followed by the RNase H domain. The four subdomains were determined from a well-ordered electron density, whereas the RNase H could be only generally positioned, and thus its exact structure was independently determined [74] and its coordinates were used for the whole RT structure. The fingers and palm subdomains of MLV RT fold into a rigid and stable structure that is independent of the rest of the enzyme. The structures of these subdomains, when expressed as the N-terminal portion of the enzyme, are nearly identical for both the unliganded fingers-palm segment and the one complexed with DNA. They are also remarkably similar to the same subdomains in the full-length MLV RT structure [73].

The structures of HIV-1 RT and MLV RT have been recently compared in detail [75], and, therefore, we will only briefly describe the major differences and similarities between the two enzymes. There are several conserved elements that are common to the two enzymes. The polymerase active site in MLV RT is located in the palm subdomain, composed of three aspartic acids at positions 150, 224 and 225 that are analogs to the corresponding residues at positions 110, 185 and 186 of HIV-1 RT. The highly conserved YXDD motif, which includes two of the three catalytic aspartic acids, is similar in both enzymes, where X is a Val in MLV RT and a Met in HIV-1 RT. These two RTs share a conserved positively charged patch on their surface that may contribute to the recognition and binding of the nucleic acid substrate. In addition, the conserved sequence LPQG appears at residues 188–191 in MLV RT and 151–154 in HIV-1 RT. Lys65 and Arg72 of HIV-1 RT, which contribute to dNTPs binding, are located in MLV RT at positions 103 and 110, respectively. The RNase H domain of both enzymes carries identical catalytic residues that are Asp524, Glu562, Asp583 and Asp653 in MLV RT and Asp443, Glu478, Asp498 and Asp549 in HIV-1 RT [75]. In addition, sequence alignment of the RNase H domains of HIV-1, HIV-2 and MLV RTs suggests that residues that form the RNase H primer grip are significantly conserved [41].

There are also considerable differences between the structures of the two RTs. The MLV RT polypeptide is longer by 111 residues than the comparable p66 subunit of HIV-1 RT. Structure-based sequence alignments suggest that these additions are distributed mainly in three different regions of MLV RT [75]. At the N-terminal portion there are an additional 40 amino acids. Another 32 residues that are positioned between the connection and RNase H may represent a highly flexible region with an unstructured pattern. In addition, there is a short segment that folds into a putative C-helix (amino acids 594–601) and a loop region. Both are also missing in HIV-1 RT and the C-helix was deliberately deleted from the isolated MLV RT RNase H domain that was used for crystallization. Interestingly, a similar motif is present in E. coli RNase H, and it is part of the basic helix loop. When this segment was inserted into the RNase H domain of HIV-1 RT, it could restore the RNase H activity of the isolated RNase H domain (as discussed above). This motif may strengthen the binding of the RNase H domain to DNA and contribute to its independent catalytic activity. Both E. coli RNase H and the isolated RNase H domain of MLV are fully enzymatically active. This is in contrast to the HIV-1 RNase H domain that is highly dependent for its catalytic activity on the fused DNA polymerase domain. The relative positions of the thumb, connection subdomains as well as the RNase H domains of MLV RT give rise to a more compact structure with a clamp shape in comparison to the structure of HIV-1 RT [73]. Notably, the polypeptide linking the connection and RNase H is the most significant difference between MLV RT and HIV-1 RT. In both proteins, this linking peptide exits the connection subdomain in a different and opposite direction. Some differences were also observed in the “minor grove binding track” motif that is located within the thumb subdomain and supports the translocation of the substrate during polymerization. Important residues in the “minor grove binding track” of HIV-1 RT such as Gln258, Gly262 and Trp266 are not conserved in MLV and correspond in this enzyme to Arg298, Glu302 and Thr306 according to structure-based alignments [73, 76]. These residues are part of an α helix that has a different path and length in the two RTs [73].

The biochemistry of RTs

All retroviral RTs produce an integration-competent, double-stranded DNA from the single-stranded viral RNA genome, combining both polymerizing and hydrolytic functions to synthesize about 18,000 phosphodiester bonds in a single RTN cycle. As shown above, the RTN cycle requires the precise combination in time and space of both RT-associated DNA polymerase and RNase H activities. Genetic, structural and biochemical studies as well as protein sequence alignments have all indicated that a single DNA polymerase active site is responsible for the RDDP and DDDP functions, while the RNase H activity is provided by a separate active site; still both sites are located on the same polypeptide. The DNA polymerase domain is located in the N terminus of the large subunit of RT, occupying about two-third of the subunit, whereas the RNase H domain is positioned on the C-terminal portion of this polypeptide (Fig. 3). Despite the spatial separation, there are both functional and structural mutual interactions between the two catalytic activities [1, 2].

The first methodical studies of RTs were performed with enzymes purified from relatively large quantities of purified virions, obtained from either infected animals or from virus grown in vitro in cell cultures. Lysis of the virions in buffers containing mild non-ionic detergents, such as Triton X-100 or NP-40, has led to the release of a soluble, enzymatically active and relatively stable enzyme that could be purified to homogeneity by a combination of ion exchange and affinity chromatography columns. In fact, early efforts to show an RDDP activity in virions owe their success, at least in part, to the use of such detergents in the enzyme preparations.

Almost none of the RTs undergo post-translational modifications. The only exception is ASLV RT that undergoes phosphorylation in the IN-related sequence close to the C-terminus of the β subunit (probable on Ser854) and may have some effect on the enzyme’s activity [7, 77, 78] (see also above). Comparative analyses of various RTs did not reveal significant differences between recombinantly expressed RTs and those released from viruses. As the technology to produce recombinant protein became widely available, a variety of highly active RTs could be expressed in substantial amounts as recombinant proteins, mostly in bacteria. Consequently, almost all structural and enzymatic studies of RTs in the last 2 decades were performed with the recombinant proteins, taking advantage of the ability to get large amounts of proteins and the simplicity to generate mutant variants. Consequently, almost all studies mentioned in this review were carried out, unless otherwise stated, with recombinantly expressed RTs.

The DNA polymerase activity of RT

General properties

RTs can be considered for the most part as a DNA polymerase that, based on structure and many of its catalytic features, is similar in many respects to other cellular and viral DNA polymerases. However, unlike other DNA polymerases (that are all DNA-dependent), RTs can copy RNA as efficiently as DNA. As a result of numerous biochemical, genetic and structural studies, which were performed mostly with HIV-1 and MLV RTs, the mechanisms of DNA synthesis of RTs are reasonably well understood. Similar to other DNA polymerases, RTs require both a primer and a template. Thus, they perform a template-directed extension of DNA or RNA primers by dNTPs incorporation according to Watson and Crick base pairing. Polymerization is done by extending the 3′-end hydroxyl of the primer by one nucleotide at a time, while forming a 3′–5′ phosphodiester bond that is accompanied by a pyrophosphate release. Accordingly, primers that lack a free 3′-OH, or nascent DNA molecules with an incorporated dNTP analog lacking the 3′-OH, cannot be extended [1, 3]. Based on this mode of action, many of the nucleoside/nucleotide analogs, routinely used to inhibit HIV-1 RT in AIDS patients, terminate DNA chain elongation as they lack the 3′-OH (see below). The polymerization reaction is reversible, and under special conditions that lead to synthesis arrest, excision of the 3′-terminal nucleotide can also occur in the presence of either pyrophosphate or ATP as phosphate donors (by a process of pyrophosphorolysis that is discussed in detail below).

As described above, the polymerization reaction is ordered in sequence, starting with the binding of RT to the template-primer substrate and followed by binding of the incoming dNTP to the N site. The binding rates of the correct versus incorrect incoming dNTPs are quite similar and are diffusion limited. Yet, the correct dNTP is bound better than the incorrect dNTP, due to the preferential hydrogen bonding with its complementary template nucleotide. Other interactions also participate in selecting the correct nucleotide, including: base stacking and residues that form the N site (see above). In addition, the geometry of the base pair formed was found to be even more important than the correct hydrogen bonding between the incoming dNTP and the template nucleotide [79]. Still, misincorporation of a wrong nucleotide is quite recurrent in RTs, especially in lentiviral RTs (see below). Since all RTs are deficient in the 3′ → 5′ exonucleolytic activity, which is common to many other DNA polymerases, the resulting lack of proofreading largely contributes to the high error rates observed for RTs. The rate-limiting step in a single nucleotide incorporation is the conformational change that accompanies the movement of the finger subdomain of p66 to close down on the incoming dNTP in order to properly align its α-phosphate with the 3′-OH of the primer (or the nascent DNA strand) and the polymerase active site. The incorporated new nucleotide is then translocated from the N to the P site of the RT (for details, see above). Yet, the overall polymerization by RTs is limited by the relatively low dissociation rate from the nucleic acid substrate [80, 81].

All RTs require divalent cations for DNA synthesis; Mg+2 appears to be the preferred one in vitro and probably also in vivo. Nonetheless, the RTs of MLV and other gammaretroviruses show an in vitro preference to Mn++ with several substrates. Two divalent cations molecules are required to coordinate the oxygen atoms of all three phosphates of the incoming dNTP and the side chains of the three catalytic aspartic acid residues (at positions 110, 185 and 186 in HIV-1 RT, Fig. 3). This interaction activates the 3′-OH of the primer and facilitates the nucleophilic attack on the α phosphate of the incoming dNTP. Additionally, the charges of the reaction intermediates are also stabilized by the two divalent cations.

The rates of polymerization in vitro by RTs are fairly slow relative to other DNA polymerases. The in vitro-measured rates depend substantially on the nature of substrate and the assay conditions. Reported rates varied from 1 to 15 nts per second, depending on the conditions of the performed study. Since it takes about 4 h from infection by HIV-1 to the first appearance of a full viral double-stranded DNA (of about 9 kb), even after considering the complexity of the RTN process, RT-directed DNA synthesis is definitely slow. Although the viral heteropolymeric RNA is the natural substrate for RTs, synthetic homopolymeric heteroduplexes of RNA–DNAs serve in vitro as better substrates. Accordingly, poly(rA)-oligo(dT) and poly(rC)-oligo(dG) are highly sensitive template-primers for testing the RDDP activity of almost all RTs, and the poly(2′-O-methyl-C)-oligo(dG) is considered to be highly specific for this activity. The different substrates for assaying DDDP activity are usually less efficiently used, with poly(dA)-oligo(dT) and poly(dC)-oligo(dG) the most efficient ones for in vitro synthesis.

Unlike other DNA polymerases, all RTs show a relatively low specificity to the templates, as they are capable of copying both RNA and DNA. However, similar to other DNA polymerases, RTs are highly specific in synthesizing only DNA and not RNA. Yet, this property can be modified by mutating an aromatic residue of RT, which is located in the nucleotide-binding pocket of the DNA polymerase domain, and this leads to an RT variant with a significant RNA polymerase activity. Consequently, it was proposed that the aromatic rings of F155, Y115 and F119, in MLV, HIV-1 RT and MMTV RT, respectively, act directly as a “steric gate” that allows the incorporation of dNTPs (that have a hydrogen atom at the 2′-position on the ribose) and discriminates against the incorporation of rNTPs with the larger 2′-OH group [53, 82, 83]. Replacing the bulky aromatic side chains of these residues by smaller amino acids causes the “gate” to open up and allows the larger rNTPs to be incorporated into the nascent polynucleotide chain (see above). Nonetheless, even these mutated RTs are at least as effective in DNA synthesis as in RNA synthesis.

As described above for RTN, during DNA synthesis from the viral RNA, RT must pause at four linear template ends (Fig. 2). In addition, the retroviral genomes are frequently nicked. As a result, RTs may encounter multiple template ends during each replication cycle. Several studies have indicated that RTs can further modify these template ends in vitro by adding non-templated nucleotides to the 3′-ends of the nascent DNA strand, similar to other DNA polymerases that lack 3′ → 5′ exonuclease activity [84–86]. However, in the case of retroviral RTs, such polymerization at template ends requires usually high ratios of RT over template primer, and it is achieved at very high dNTP concentrations that are beyond physiological conditions. Moreover, non-templated nucleotides are added poorly by HIV-1 RT under intracellular dNTP concentrations (5–10 μM), in a rate that is at least 10,000-times slower than templated synthesis. It was also suggested that such additions to blunt-ended DNA by HIV-1 RT can lead to a non-specific strand transfer if the formed non-templated 3′-end overhangs are complementary to 3′-end sequences of the acceptor DNA strand. Since this non-specific strand transfer is achieved at a very high excess (70-fold) of the acceptor strand, the biological relevancy of this finding is still questionable [85]. A much higher capacity to perform non-templated addition of nucleotides in vitro has been recently shown for the RT of the LTR retrotransposon Tf1 [86]. A surprisingly large portion of cDNA molecules of Tf1, produced in vivo in cells, have random, presumably non-templated sequences on both U3 and U5 ends [87]. Therefore, it is likely that the ability of Tf1 RT to incorporate non-templated nucleotides into the nascent DNA strands represents a unique and biologically relevant RT feature.

Processivity of DNA synthesis

The processivity in vitro of various RTs is quite poor relative to other DNA polymerases, as RTs do not stay attached to the growing DNA strand for many successive cycles of dNTP additions [88]. Despite their ability to polymerize up to a few hundred nucleotides in a single synthesis round, RTs tend to fall off in vitro at specific sequences or structures, defined as “strong stops.” Although not all of these sequences are well defined, it was found that several RNA structures (e.g., pseudo-knots) are mostly difficult to copy, thus raising their potential use as RT inhibitors [1]. In addition, some mutations in HIV-1 RT were shown to affect the processivity of the enzyme. More interestingly, a correlation was found in several HIV-1 RT mutants between their increased resistance to nucleoside/nucleotide RT inhibitors (NRTIs) and both the decreased processivity and increased fidelity of DNA synthesis in vitro [89, 90]. Specifically, a decrease in the ability to incorporate nucleoside analogs (which is manifested by an increase in drug resistance) is accompanied by a reduction in both the processivity of DNA synthesis and the capacity to misincorporate dNTPs and extend the formed mismatches (see below) [79, 91–94]. Still, it is not clear whether these findings reflect also a low in vivo processivity in infected cells. It is likely that other factors may be more relevant to the in vivo activity, as it is one of the driving forces behind the rapid mutagenic processes that accompany retroviral replication.

Fidelity of DNA synthesis

As mentioned above, the lack of the 3′ → 5′ exonucleolytic proofreading function can contribute by itself to the low fidelity in synthesizing DNA by RTs. However, other features of RT can also increase the tendency to introduce errors while synthesizing DNA. The accuracy of DNA synthesis has been measured in many in vitro studies, employing both synthetic polynucleotide substrates as well as “natural” DNA or RNA substrates [79, 95, 96]. Base substitutions were detected at high frequencies, due to nucleotide misinsersions as well as the subsequent mispair extensions, all revealing that RTs are much more error prone (by factors ranging from 10 to 103) than cellular DNA polymerases. Interestingly, RTs of lentiviruses (including those of HIV-1 and HIV-2) were found to be less accurate than most of other RTs studied [95–100], highlighting the effects of specific RT sequences on the level of fidelity. Certain dNTP-binding residues, various residues that interact with the template or the primer strands, as well as RT residues in the minor groove-binding track, were all shown to play major roles in the fidelity of retroviral RTs [101]. The sensitivity of RT to NRTIs can be seen as a manifestation of the inherent low fidelity of RT, as the enzyme misincorporates NRTIs instead of the correct dNTPs. Hence, drug-resistant variants of HIV-1 RT may evolve to distinguish better than the wild-type RT between these competitive NRTI and the correct dNTPs (see below). Consequently, in several of these mutants (e.g., E89G, M184V or M184L and Q181I), the reduced sensitivity to NRTIs is accompanied by an enhanced discrimination between the mispaired (but unmodified) nucleotides and the correct nucleotides [79, 93]. The type of nucleic acid copied (RNA vs. DNA) does not seem to affect misinsertion and mispair extension frequencies, while the specific sequences by themselves have substantial effects on the fidelity of each RT tested. This suggests that the fidelity of a given RT is sequence-dependent and enzyme related [99].

The frequencies of base substitutions that are formed by a given RT may vary and depend on the created mispairs. However, misinsertions and the resulting mispair extensions are not the only ways to produce errors during RTN. An error can be introduced by a slippage of the primer strand over the template strand that may result in either nucleotide deletions or insertions. More complex alternatives, such as dislocation mutagenesis, were also proposed [95] and can operate over large distances, thus leading to massive consequences. The in vivo rates, by which retroviruses undergo mutations, are estimated to be between 10−4 and 10−5 mutations per nucleotide. Several studies have tested the correlation between in vivo mutation rates and the in vitro fidelity of RT, using the forward mutagenesis assay with either phage or plasmid DNA with a reporter gene [79, 95, 96]. Correlation to the RTN process is only partial, since it is apparent that this process is much more complex, due to the consecutive strand transfer steps (vide supra) as well as the involvements of other viral and cellular proteins (vide infra). Therefore, it is possible that some of the systems utilized to measure in vitro fidelity of DNA synthesis are valid for mainly comparative purposes, i.e., to evaluate how different enzymes and various RT mutants behave under identical conditions.

The viral RT is not the only factor contributing to the high mutation rates observed in retroviruses. Cellular RNA polymerase II, which has a relatively low fidelity and transcribes the viral DNA into RNA of the progeny virions, also affects retroviral mutation rates. Furthermore, other viral and cellular proteins can also indirectly influence retroviral mutations rates. These include the retroviral dUTPase, the regulatory protein Vpr of HIV-1 [102] and the cellular APOBEC3 [103], all of which are described in detail below.

Initiation of RT-directed DNA synthesis

In almost all cases, the initiation of (−) strand DNA synthesis in RTN depends on a tRNA primer (see above). Elaborate inter- and intramolecular tRNA-genomic RNA interactions appear to be the hallmark of initiating (−) strand DNA synthesis [20]. In addition, the involvement of chaperone activity of HIV-1 NC protein in forming the initiation complexes was well documented as part of multimolecular functional interactions between NC, RT and the tRNAlys3 primer [104–106]. Once initiation complex is generated, the RT-directed (−) DNA strand synthesis takes place in two steps. First, there is an initiation step where up to 6 nts are added to the 3′-end of the primer in a non-processive manner. Afterwards, there is an increase in the affinity of RT towards the substrate that is accompanied by a huge increase of the polymerization rate (by approximately 3,000-fold). This represents a transition from the initiation step to elongation that probably depends on structural features of the tRNAlys3, such as modified bases at the anti-codon domain [20]. Concurrent with the synthesis of (−) sssDNA, the RNase H activity of RT degrades the RNA template with the help of the viral NC that can unwind 8–12-nts-long double-stranded sequences [104–106] (see also below). Non-specific initiation events, which are likely also to take place (due to nicks in the genomic RNA), are repressed by NC that coats the RNA and unwinds unstable RNA duplexes.

Synthesis of (+) strand DNA is initiated from the 3′ PPT and some additional RNA primers, which are relatively resistant to the degradation by RNase H during partial removal of the (+) RNA strand (see above). In HIV-1 RT (+) strand synthesis is initiated also from both the cPPT and the 3′ PPT (vide supra). Although the 3′ PPT is the major (+) strand initiation site, in several lentiviruses the presence of the cPPT was shown to be critical for an efficient replication. The (+) strand DNA priming is much more efficient with PPT primers than extending non-PPT RNA primers annealed to DNA. Since PPTs are generated by precise cleavages of the viral RNA that is annealed to the (−) strand DNA by the RNase H activity, the initiation and elongation of (+) strand DNA requires a high coordination between both RT-associated activities, as described below (for review, see [28]).

Strand transfer activity

As outlined above, during RTN there are two strand transfer events, also referred to as template switches (Fig. 2). In both cases, there is a switch of either the 3′-end of the elongated primer, or the 3′-end of the nascent (+) DNA strand to an acceptor template. These switches depend on sequence complementarity usually found at the 3′-end of both the donor and acceptor strands (for a recent comprehensive review, see [36]). Retroviral virions carry two similar (+) RNA copies of the viral genome. Therefore, (−) strand transfer can be potentially either intermolecular or intramolecular, and both types were observed with similar frequencies. As the acceptor template is the (+) RNA genome, which is present in two copies in each virion, equal ratios of inter- or intra-molecular strand transfer may actually represent the probability to encounter a single RNA strand. On the other hand, (+) strand transfer is predominantly intramolecular [26, 27]. This could be expected, as intermolecular strand transfer would require the less likely scenario of two (−) strand DNA copies. Additional strand transfer events were suggested in the forced copy choice model. According to this model, RT initiates (−) DNA strand synthesis on a single genomic RNA molecule, but upon reaching a break in this template it switches to the second RNA molecule, which was co-packaged in the same virion, to continue the synthesis. This mechanism was supported by in vivo studies conducted with viruses containing a relatively large amount of cleaved genomic RNA. Since these viruses were fairly infectious, it is likely that strand transfer rescued the viruses with damaged genomes. A different model is the copy choice model that expands the alternative of (−) strand template switching to include intact templates rather than nicked ones. In both models, there is a requirement for high sequence homology between the donor and acceptor template molecules. Evidently, during DNA synthesis the nascent DNA strand reaches a region, in which the synthesis on the second strand is more favorable than synthesis on the current strand, leading to a strand transfer. This can be enhanced by specific sequences that are mostly pausing sites, but additional factors may also affect strand transfer. Theses include the delicate balance between the DNA polymerase and RNase H activities of RT [36] (see below) and the chaperone activity of the viral NC protein, which facilitates the annealing of the acceptor RNA to the (−) strand DNA via their complementary sequences (see below). An additional model, designated the dynamic copy-choice model for retroviral recombination, was proposed. Here, the steady states between the rates of polymerization and RNA degradation determine the frequency of template switching by RT [107].

Strand displacement activity

This activity is common to all RTs and absent in most other DNA polymerases. Strand displacement is required during (+) DNA strand synthesis, when the synthesis has been initiated from multiple primers (Fig. 2). This activity is mediated by the RT-associated helicase activity that enables the enzyme to unwind the double-stranded DNA during strand displacement synthesis. Displacement of a downstream (+) DNA strand may assist the removal of discontinuous (+) DNA segments in order to generate the complete double-stranded DNA that is vital for a successful integration into the host genome. This activity can also generate the central DNA flap, as described above. Although the rates of both displacement and non-displacement DNA synthesis vary for different sites over the template, strand displacement synthesis is, on the average, slower by a factor of 3–4 than regular synthesis [108, 109]. Displacement activity during (+) strand DNA synthesis was shown in permeabilized virions, supporting its biological significance [110]. RTs have also been shown to displace in vitro RNA segments, which are too long to be removed by the RNase H activity and are annealed ahead of the primer terminus during (+) strand DNA synthesis [108, 111]. Such RNA displacing DNA synthesis may be required for removing stably annealed genomic RNA fragments after (−) strand DNA synthesis. The fingers subdomain of RTs is involved in DNA-DNA displacement synthesis through interactions with either the template or non-templated strands. Mutations in this domain were found to affect the strand-displacement activity of RT but not the processivity of DNA synthesis [51, 112].

The RNase H activity of RT

The RT-associated RNase H activity functions as a processive endonuclease that hydrolyzes the RNA in RNA-DNA heteroduplexes (for recent detailed reviews, see [24, 25]). Unlike conventional ribonuclease, the RNase H activity hydrolyses phosphodiester bonds to produce a 3′-OH and a 5′-phosphate ends. This property is critical for RTN, as the oligo-ribonuceotides formed by RNase H must prime (+) strand DNA synthesis (see above). The RNase H domain of RT is separated from the DNA polymerase domain by the connection domain (Fig. 3); however, there are mutual critical contacts between the two domains. The hydrolytic cleavage by the retroviral RNases H activity involves a two-Mg+2-ion catalytic mechanism, described above [24, 25, 113]. In HIV-1 RT, the RNase H active site is rich in acidic residues, including Asp443, Glu478, Asp498 and Asp549. The catalysis continues in a two-metal ion-dependent trans-esterification reaction, similar to the one that has been proposed for DNA polymerases. However, the RNase H activity is mediated by a nucleophilic attack of a water molecule on the scissile phosphate, breaking the bond between two adjacent ribonucleosides in the RNA strand (instead of the nucleophilic attack of 3′-OH of the primer on the α phosphate of the incoming dNTP during DNA synthesis). This involves activation of the nucleophilic water by one of the divalent cations, with transition-state stabilization apparently mediated by both Mg+2 ions.

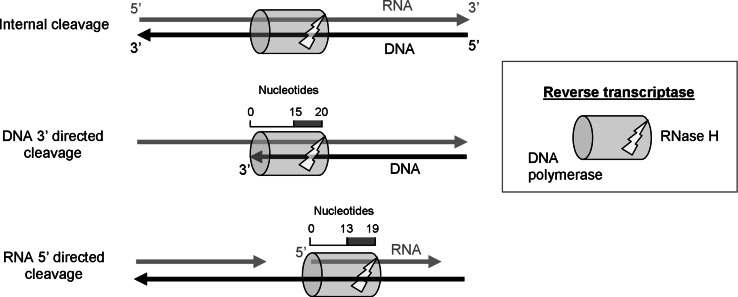

Three distinct modes of RNase H cleavages were characterized based on the interactions between RT and the RNA–DNA substrate (for further details, see Fig. 4 and [24, 25]). The first mode is a DNA 3′-end directed cleavage, where the DNA polymerase domain of RT is bound to the 3′-end of nascent DNA strand, which is annealed to the longer RNA template. This mode positions the RNase H active site towards the 3′-end of the RNA template (behind the 3′-end of the growing strand), so that the two RT domains are separated by 15–20 nucleotides on the RNA strand. Further cleavages of the RNA, at distances corresponding to about 8 nts from the 5′-end of the nascent DNA strand, may take place due to repositioning of the RT on the DNA–RNA substrate. These cleavages can occur either during DNA polymerization or independent of any polymerization. This mode of cleavage takes place during (−) strand DNA synthesis to facilitate strand transfer. When it is tightly linked to DNA polymerization, the DNA 3′-end directed cleavage correlates also with the pausing sites, caused by secondary structures encountered during the RDDP process. However, the polymerization rate of RT is greater than the hydrolysis rate of the enzyme. Therefore, the polymerization-dependent RNase H activity is insufficient to fully remove the genomic RNA template, and other modes of RNA degradation are required as well.

Fig. 4.