Abstract

Keratan sulphate (KS) is the predominant glycosaminoglycan (GAG) in the cornea of the eye, where it exists in proteoglycan (PG) form. KS-PGs have long been thought to play a pivotal role in the establishment and maintenance of the array of regularly-spaced and uniformly-thin collagen fibrils which make up the corneal stroma. This characteristic arrangement of fibrils allows light to pass through the cornea. Indeed, perturbations to the synthesis of KS-PG core proteins in genetically altered mice lead to structural matrix alterations and corneal opacification. Similarly, mutations in enzymes responsible for the sulphation of KS-GAG chains are causative for the inherited human disease, macular corneal dystrophy, which is manifested clinically by progressive corneal cloudiness starting in young adulthood.

Keywords: Keratan sulphate, Proteoglycan, Glycosaminoglycan, Cornea, Collagen

Introduction

Keratan sulphate (KS) is the major glycosaminoglycan (GAG) in the cornea. First discovered in the tissue by Meyer and associates [1], KS has long been believed to play a central role in corneal homeostasis, not least because it is altered when the cornea becomes opaque because of injury or disease [2, 3]. KS-GAGs in cornea are complexed to one of three core proteins—lumican, keratocan or mimecan—and, thus, exist as proteoglycans (PGs) [4–6]. A number of comprehensive review articles have evaluated the roles of GAGs and PGs in connective tissues [7–12], including publications which have highlighted the importance of KS-PGs in cornea [12–16]. Kao and Liu, in particular, have described the biochemistry, molecular biology, expression patterns and genomic structures of the lumican and keratocan core proteins, each of which contains a signal peptide, a negatively-charged N-terminal peptide, tandem leucine-rich repeats, and a carboxyl terminal peptide [16]. In this article, we will review current knowledge pertaining to the biochemistry, sulphation pathways and molecular relationships of KS-GAGs in the cornea.

Corneal structure and function

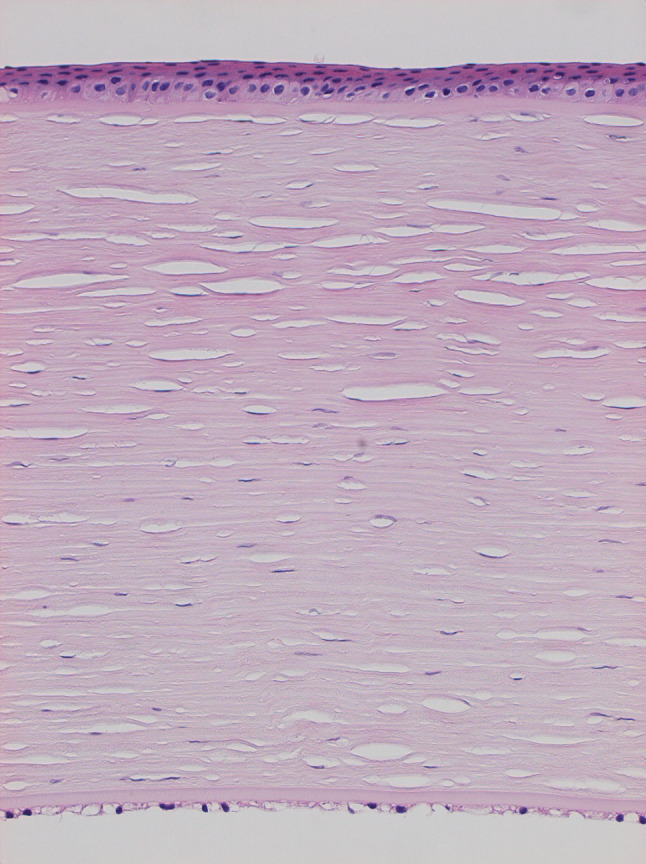

The cornea is comprised of a multi-layered cellular epithelium which supports the tear film at the front of the eye, a connective tissue stroma, of which Bowman’s layer is an acellular anterior modification, and an endothelial monolayer with its own basement membrane, Descemet’s membrane (Fig. 1). The stroma makes up the bulk of the cornea and is comprised of uniform diameter collagen fibrils organised into a stacked lamellar array. In humans, the cornea is approximately 550 μm thick, and the stroma is made up of about 200–250 lamellae [17], which typically are thinner and more interwoven in the anterior sub-epithelial third of the tissue, and thicker and more stratified in deeper regions [18] (Fig 1). Collagen fibrils in the corneal stroma have remarkably regular diameter, measuring approximately 30 nm in humans when the cornea is hydrated [19], and around 25 nm in the fixed, dehydrated tissue when visualised in the transmission electron microscope using routine methods [20], although some preparative regimes result in less lateral shrinkage of the collagen fibril [21].

Fig. 1.

Histologic image of a human cornea in sagittal section, after formalin fixation, paraffin wax embedding, and section staining with H&E; original magnification ×20. The stroma, which is about 500 μm thick, is bound superficially by the multicellular corneal epithelium and posteriorly by the endothelial monolayer and Descemet’s membrane, and forms the bulk of the tissue. Nuclei are stained blue, and splits in the stroma are artefacts of the preparative process. (Figure courtesy of Dr Hidetoshi Tanioka, Department of Ophthalmology, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Japan)

The cornea is unique amongst collagen-rich connective tissues because it is transparent to visible light. In this key respect, it differs from tissues such as tendon, cartilage or even the adjacent white sclera which forms the remainder of the eye’s outer tunic. Clearly, corneal transparency is essential for vision, and is believed to be, at least in part, structural and dependent upon a precise and characteristic spatial arrangement of collagen fibrils. Theories of corneal light transmission contend that collagen fibrils scatter light in such a way that destructive interference occurs in all directions other than the forward direction [22]. This transparency model has been embraced by the scientific community [23–28], and while a strict lattice of collagen fibrils is not seen as an absolute requirement for corneal transparency, some level of structural order is. Keratocytes are stromal fibroblasts which are interspersed with collagen in the cornea at an estimated density of between 4.6 × 104 and 6.2 × 104 cells/mm3 in humans, with higher densities peripherally and in younger individuals [29, 30]. The use of stereological techniques to examine electron micrographs of adult rabbit cornea determined a percentage cell volume of keratocytes in the stroma of around 10% [31]. As Jester and colleagues discovered, keratocytes contribute to corneal transparency because they contain unusually high cytoplasmic levels of two water-soluble proteins (transketolase and aldehyde dehydrogenase class 1, also known as corneal crystallins) which serve to minimise refractive index inhomogeneities in the keratocyte cytoplasm, with most of the scattered light from cells arising from the nuclei [32, 33].

Small leucine-rich PGs in the corneal stroma—of which KS-containing PGs are the most prevalent—are believed to help govern the size and arrangement of collagen fibrils. The accepted view of collagen–PG interactions in cornea contends that associations occur via the core protein domains of the PGs, with the hydrophilic, sulphated GAG chains occupying the interfibrillar space where they help define the swelling properties of the stroma [34–36] as well as the diameter [37] and spatial organisation of the collagen fibrils [38]. Consequently, these hybrid protein–carbohydrate molecules are seen as vitally important for the maintenance of corneal ultrastructure and light transmission.

KS biochemistry

KS-GAG is a linear carbohydrate chain that consists of repeating disaccharides composed of galactose (Gal) and N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) with sulphation at the 6-O positions on the saccharides. The structure of KS-GAG is relatively simple when compared with other GAGs such as chondroitin sulphate (CS) or heparan sulphate (HS), which have multiple sulphation residues and isomeric structures. Another difference is that KS-GAG is attached to its core protein by linkages that are commonly observed in secreted and membrane-bound glycoproteins, whereas CS and HS-GAGs are attached to their core proteins via a unique tetrasaccharide linker (GlcA-Gal-Gal-Xyr-O-Ser) (GlcA, glucronic acid; Xyr, xyrose). From this standpoint, the glycosylation of KS is similar to that of glycoproteins in general, rather than to CS and HS. Indeed, the elongation step of KS-GAG is catalysed by glycosyltransferases that also act on glycoproteins and glycolipids, while CS and HS-GAGs are elongated by their own special enzyme complexes.

Numerous biochemical investigations have analysed KS in cornea, with much information being derived from the extensive experiments, using column chromatography, of Oeben and colleagues who worked on KS-GAG structure in pig cornea [39]. Tai and associates subsequently studied bovine and human corneal KS-GAG structures by HPLC separation followed by NMR structural determination and found a variety of capping structures on the non-reducing terminal of KS [40, 41]. Plaas and co-workers subsequently analysed the composition of repeating disaccharide units of human corneal KS by fluorophore-assisted carbohydrate electrophoresis (FACE) and proposed a structure for the linearly elongated part of the GAG chain [42]. Based on the aforementioned studies, the standard corneal KS structure is viewed as a bi-antennary complex-type N-glycan that carries a linear KS-GAG chain on one branch and a sialylated N-acetyllactosamine (LacNAc) on the other [39] (Fig 2). There may be some modifications to this structure, such as sialylation on the non-reducing terminus of the KS-GAG [40, 41]; however, not all studies agree with this hypothesis [39, 42]. A fucose modification is also found on the N-glycan core structure in cornea, but not in the GAG chain [39, 42, 43]. KS-GAGs from tissues other than cornea have different linkage structures and a variety of carbohydrate modifications when compared to corneal KS, but these will not be commented on in this article because they have been comprehensively discussed by Funderburgh in previous publications [11, 12].

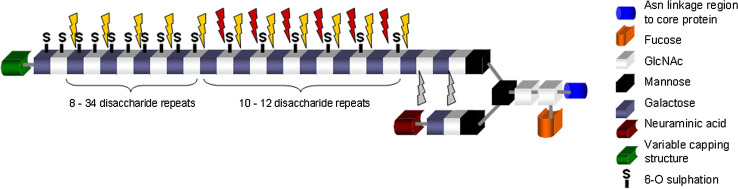

Fig. 2.

A schematic depicting the generic structure of corneal KS and the actions of various KS-degrading enzymes. The disaccharide structure of KS can be either di-, mono- or unsulphated on the repeating disaccharide units. Disulphated structures occur towards the non-reducing terminal, monosulphated disaccharides towards the middle of the structure and unsulphated disaccharides towards the linkage region of the chain. Keratanase cleaves at β1-4 galactosidic linkages in which unsulphated galactose and sulphated N-acetyl glucosamine (GlcNAc) residues participate (red arrows). Keratanase II cleaves at β1-3 glucosaminidic linkages to galactose where the disaccharide structure can be either mono- or disulphated (yellow arrows). Endo-β-galactosidase cleaves at β1-4 galactosidic linkages where both the galactose and the GlcNAc residues are not sulphated (grey arrows). It can also cleave at the same sites as Keratanase but at a much lower reaction rate. (Figure courtesy of Dr Melody Liles, School of Optometry and Vision Sciences, Cardiff University, UK)

Sulphation is a major modification on corneal KS, which is neither uniformly nor randomly distributed in the linear GAG chain. In pig cornea, for example, the reducing terminal region of KS-GAG, which is closest to the N-glycan core, is not sulphated for several units of repeating disaccharides [39]. The adjacent region, comprising about 10 repeating disaccharide units, is sulphated only at the 6-O positions of GlcNAc, whereas a non-reducing terminal region extending over 7–34 disaccharide repeats is fully-sulphated at the 6-O positions of both GlcNAc and Gal [39]. HPLC/NMR analysis of bovine and human corneal KS indicated a similar carbohydrate chain length with about 32 disaccharide repeat units, on average, in an N-glycan molecule [40, 41]. FACE [42] disclosed a much shorter chain length for human corneal KS-GAG of about 14 disaccharide repeats in a linear chain, but revealed that the ratio of fully-sulphated, GlcNAc-sulphated and non-sulphated disaccharides—estimated as 54, 42 and 4%, respectively—is in agreement with other studies. The production of these identifiable domain structures which are distinguished by their degree of sulphation is a result of the biosynthetic pathway of KS-GAG in cornea, which is discussed later in this article. Sulphation of KS in cornea is important because sulphate residues are negatively charged, and as a consequence, highly-sulphated KS-GAG is more hydrophilic than poly-N-acetyllactosamine (polyLacNAc)—i.e. non-sulphated KS-GAG. This has implications for corneal extracellular matrix structure, collagen organisation and tissue transparency.

For structural analysis of KS-GAG, monoclonal antibodies and endo-glycosidases are commonly used. The best-characterised anti-KS antibody is 5D4, a mouse monoclonal antibody produced by Caterson and colleagues that recognises highly sulphated KS [44]. The minimum epitope for 5D4 is a pentasulphated hexasaccharide structure [45]. 5D4 is also reactive to cartilage and serum KS, and its use in the 1980s and since was central to the discovery that most patients with the inherited disease, macular corneal dystrophy, have no highly sulphated KS in their cornea or serum [46], of which more later in this article. More recently, Caterson’s group have also made an antibody called BKS-1 which recognises a keratanase-generated neoepitope [N-acetyl-glucosamine-6-sulphate (GlcNAc-6-S)] at the non-reducing terminal of corneal and skeletal KS-GAG chains, and this has been used to study human cornea in health and disease [47, 48]. Other anti-KS antibodies are also available, although their specific epitope structures are unknown.

Endo-glycosidases are also frequently used for structural analysis of KS-GAG (Fig 2). Endo-β-galactosidase is isolated from Escherichia freundii, and hydrolyses internal Galβ1-4GlcNAc linkages in KS [49, 50]. The presence or absence of GlcNAc sulphation does not affect the enzyme’s activity; however, sulphation on Gal blocks its enzymatic hydrolysis. Thus, endo-β-galactosidase degrades non-sulphated KS (polyLacNAc) as well as GlcNAc-sulphated KS, but not KS chains in which both GlcNAc and Gal are sulphated. Keratanase is an enzyme, isolated from Pseudomonas sp., which digests a linkage of Galβ1-4GlcNAc that possesses sulphate on GlcNAc, but not on Gal [51]. This substrate specificity means that keratanase only hydrolyses GlcNAc-sulphated KS. A third KS-degrading enzyme (called keratanase II) is isolated from Bacillus sp. and is actually an endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase which cuts GlcNAcβ1-3Gal linkages [52]. It requires substrates to be sulphated on GlcNAc, but hydrolyses them with or without sulphation on Gal. Therefore, keratanase II hydrolyses both highly-sulphated KS-GAGs and GlcNAc-sulphated KS-GAGs. So far, there is no enzyme reported to hydrolyse Gal-sulphated polyLacNAc structures. The endo-glycosidases are commonly used to degrade KS-GAG chains into oligosaccharides, whose structures are readily determined by HPLC, gel electrophoresis and mass spectrum analyses.

Sulphotransferases and KS chain elongation

Corneal KS synthesis basically follows the common N-glycan biosynthetic pathway, especially for core structure processing. High-mannose type oligosaccharide clusters are transferred on nascent core proteins during polypeptide synthesis-coupled translocation at the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER). In the RER and Golgi-apparatus, N-glycan core structure is processed by a series of glycosidases and glycosyltransferases to achieve a complex-type, bi-antennary structure. The core structure is then processed to carry a linearly elongated KS-GAG carbohydrate. Four enzymes are involved in KS-GAG synthesis, β1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (β3GnT), β1,4-galactosyltransferase (β4GalT), N-acetylglucosamine 6-O sulphotransferase (Gn6ST) and galactose 6-O sulphotransferase (G6ST). Sulphotransferases required for KS-GAG sulphation are corneal Gn6ST (CGn6ST, also known as GST4β/GlcNAc6ST-5) and KS G6ST (KSG6ST). These transfer sulphate on the 6-O positions of GlcNAc and Gal, respectively [53, 54], and have high homology to each other, as well as to other carbohydrate 6-O sulphotransferases such as chondroitin 6-O sulphotransferase [55]. Although CGn6ST and KSG6ST are paralogous enzymes, their substrate specificity is not overlapping because CGn6ST transfers sulphate specifically on the non-reducing terminal GlcNAc, whereas KSG6ST transfers sulphate on both internal and non-reducing terminal Gal [53, 56]. As a result of the substrate specificity of CGn6ST, the sulphation of GlcNAc is believed to be coupled to elongation of the KS-GAG chain, which is consistent with the fact that most of the GlcNAc in KS is sulphated [39, 42]. It has also been reported that KSG6ST transfers sulphate on Gal that is located next to a sulphated GlcNAc more efficiently than it does on Gal which neighbours a non-sulphated GlcNAc [57]. This suggests that Gal sulphation occurs after production of GlcNAc-sulphated KS-GAG; however, it is yet to be confirmed whether or not GlcNAc sulphation needs to precede Gal sulphation during KS production in vivo.

The β3GnT and β4GalT families have nine and seven members, respectively. All the enzymes in the β4GalT family (β4GalT1-7) are homologous, whereas the nine β3GnT enzymes include eight homologous enzymes (β3GnT2-9) plus one distinct protein, β3GnT1 (also known as i-GnT). All these enzymes have activity to transfer a sugar to a non-reducing terminus of a carbohydrate chain, but each has its own substrate specificity. Seko and associates analysed the activity of these glycosyltransferases over sulphated carbohydrate substrates in vitro and reported that β3GnT7 and β4GalT4 have efficient glycosyltransferase activity for sulphated substrates, suggesting that they act on the elongation of the KS chain [58, 59]. Using soluble-form recombinant enzymes, it was shown that a mixture of three enzymes—β3GnT7, β4GalT4 and CGn6ST—catalysed to produce GlcNAc-sulphated KS chains in vitro. Further treatment of the products by KSG6ST resulted in the generation of highly-sulphated KS-GAG, indicating that the four enzymes are sufficient to produce highly-sulphated KS [60]. Moreover, reduced expression of a glycosyltransferase gene by a specific siRNA resulted in the suppression of highly-sulphated KS-GAG in cultured human corneal cells, confirming that β3GnT7 and β4GalT4 are indeed essential for its production [60].

In the proposed structure of KS-GAG, the carbohydrate chain is attached to the N-glycan core structure via non-sulphated LacNAc repeats, which suggests that the production of the initial LacNAc repeats might be catalysed by glycosyltransferases other than β3GnT7 and β4GalT4. One candidate is β3GnT2, which is thought to be influential in N-linked polyLacNAc (i.e. unsulphated KS) production [61]. However, the amount of corneal KS in the β3GnT2-deficient mouse is unchanged compared to normal (Akama, T.O., unpublished observations), thus the contribution of β3GnT2 for corneal KS-GAG production may be negligible. It is also conceivable that β3GnT7 may act on the production of the initial LacNAc structure, given that the enzyme has significant glycosyltransferase activity for non-sulphated carbohydrate substrates [60].

Structural associations with collagen

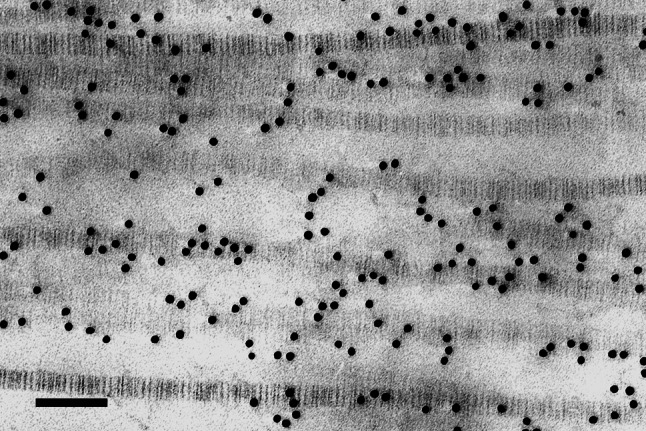

The development of the cationic dyes, Cuprolinic blue and Cupromeronic blue, by Scott in the 1980s greatly aided research into the structural associations between collagen fibrils and PGs in a range of connective tissues [62]. The KS glycan chains of KS-PGs can be visualised by transmission electron microscopy following incubation of corneal tissue with the enzyme chondroitinase ABC, which selectively removes chondroitin sulphate/dermatan sulphate (CS/DS) GAGs from the tissue, prior to staining with the cationic dye. The dye binds to and precipitates negatively charged GAG chains which can then be contrast-enhanced with tungstate ions to appear as electron dense filaments, and thus reveals their spatial associations with collagen fibrils. Collagen fibrils are typically contrasted with uranyl acetate alone, or in combination with other heavy metal salts such as phosphotungstic acid, so that the 65-nm axial D-periodic repeat becomes visible in electron micrographs (Fig. 3). Scott and his colleagues used Cuprolinic and Cupromeronic blue to locate with high precision the likely binding sites of KS-PGs, via their core proteins, on (rabbit) corneal collagen fibrils. They discovered that PGs substituted with KS-GAG chains bound at the “a” and “c” staining bands in the overlap region of the collagen fibril [63]. CS/DS-PGs, on the other hand, associated with collagen in the gap region of the collagen axis, at the “d/e” staining bands, thus implying separate roles for the two main PG sub-classes in cornea. Synchrotron X-ray diffraction experiments by Meek and associates confirmed that the binding of KS-PGs to fibrillar collagen in bovine cornea occurred at the “a” and “c” bands [64].

Fig. 3.

Collagen fibrils in longitudinal section in the stroma of bovine cornea swollen in 0.15 M saline. The characteristic 65-nm D-periodic repeat along the collagen axis is clearly visible after contrasting with uranyl acetate. Gold particles, 10-nm in diameter, indicate sites of highly-sulphated KS-GAG labelled with monoclonal antibody 5D4. Bar 100 nm

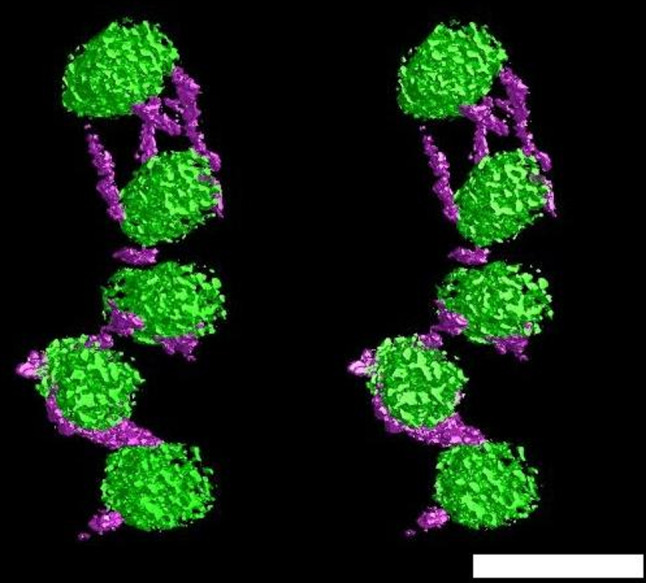

The advent of these electron histochemical labels permitting high resolution observation of specific PGs opened up a new approach to investigate the organisation of tissue components in the corneal matrix. Hitherto, the model of Maurice [65] invoking six PG molecules radiating circumferentially from each collagen fibril to connect with six nearest neighbours, thus creating an hexagonal superstructure, had remained unchallenged. Comparative morphometric studies of the lengths and diameters of Cupromeronic blue-stained PG filaments in both isolated populations and in tissue sections from rabbit and bovine cornea subsequently enabled Scott to propose a more detailed model for corneal PG–collagen interactions [66]. In this scheme, glycan chains of paired KS-PGs formed antiparallel duplexes which either wrapped around fibrils, extending equatorially around one-half of the fibril circumference, or acted as bridges between adjacent collagen fibrils. The CS/DS-PGs extended in a linear fashion, duplexing with PGs on adjacent fibrils, forming altogether longer structures with the potential to link multiple fibrils. This model has since been questioned on the grounds that it was based on measurements from corneas that may have been swollen, and it was suggested that PGs may link fibrils by next-nearest-neighbour associations [67]. Current work in our laboratory using new techniques of electron tomography to obtain 3D reconstructions of collagen-PG interactions in the cornea (Fig. 4) supports the overall concept of Scott with KS-PGs contributing to short-range stability between fibrils and CS/DS-PGs extending across several fibrils throughout lamellae [68, 69]. We are also attempting to better preserve native structure in the corneal stroma by subjecting freshly dissected, physiologically hydrated tissue to high-pressure cryofixation under conditions that should preferentially create vitreous or microcrystalline ice, and have had some initial success visualising collagen as well as structures in the interfibrillar space which are believed to represent PGs (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Stereo pair of transverse section of collagen fibrils (green) interconnected by histochemically stained KSPG filaments (purple). Reconstruction obtained from anterior central portion of bovine corneal stroma treated with chondroitinase ABC. Bar 50 nm. (Figure courtesy of Drs Carlo Knupp, Philip Lewis and Christian Pinali, School of Optometry and Vision Sciences, Cardiff University, Wales, UK)

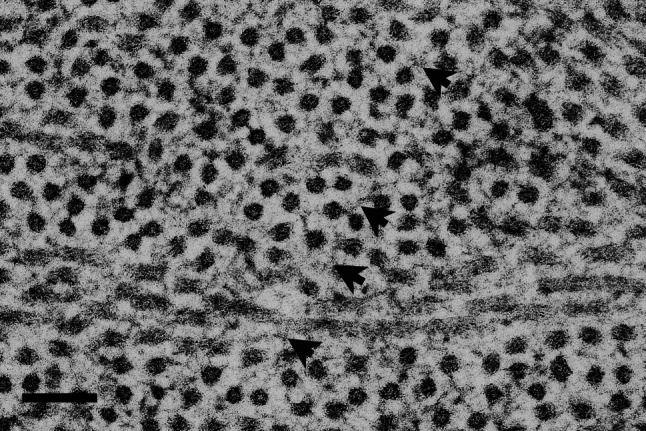

Fig. 5.

Diffuse structures, presumed to be PGs (arrowheads), are preserved between collagen fibrils in transverse section, in the absence of cationic staining. This micrograph is of mouse corneal stroma prepared by cryofixation using liquid nitrogen in a Leica EMPACT2 high pressure freezer, followed by freeze-substitution in acetone with osmium tetroxide, to better preserve native matrix architecture. Bar 100 nm

The pattern of KS-PG associations with collagen is different in the corneas of different animal species, and it is of interest to note that electron microscopical investigations locating stained PG filaments in the corneas of mice found few readily identifiable structures at the “a” and “c” bands [70]. Rather, preferential binding occurred at the “d/e” bands, where CS/DS-PGs ordinarily bind. The conclusion of this work is that mouse cornea does not possess as many sulphated KS-PG filaments as are seen in the corneas of other species examined in the same manner, precisely because the “a” and “c” bands of collagen are generally unoccupied. Also, it appears that CS/DS-PGs do not associate with collagen at the “a” and “c” binding sites reserved for KS-PGs. More recently, immunohistochemical analyses have supported the concept of a mouse cornea with low levels of sulphated KS [71]. While the highly sulphated form of KS appears predominant in the mature cornea of most mammalian species, antibodies to PG core proteins showed low sulphated KS, as well as DS-PG, to be associated with type VI collagen filaments located in the space between the main interstitial stromal fibrils in foetal rabbit cornea [72].

Distribution of corneal KS

There have been many attempts to plot the distribution of KS-GAGs using biochemical analysis or histochemical localisation techniques in cornea [70, 73, 74], and also articular cartilage [75–77], both of which are avascular, relatively acellular connective tissues. The pattern of KS-GAG deposition throughout the depth of the corneal stroma appears to alter distinctly during embryonic development, whereas in adult corneas of different animal species, a striking gradation in the abundance of sulphated KS is apparent, particularly in larger animals [74]. The thin corneal stroma of the mouse, at around 60–80 μm, contains little detectable KS-GAG and this is mostly undersulphated. Cow and rabbit corneas, on the other hand, contain considerable amounts of highly sulphated KS-GAG. In bovine cornea, with a stromal thickness around 800 μm, sulphated KS-GAG increases markedly from anterior to posterior stromal regions [70, 73]. As this increase was seen mainly in the oversulphated domain of KS-GAG chains, and was associated with an increased presence of “a” band occupancy of PG filaments on collagen fibrils, the suggestion was made that the ‘a’ band was the preferential binding site for more highly sulphated isoforms of KS-PGs, with lesser sulphated KS-PGs located at the “c” band [63, 70, 78]. Increasing KS-GAG in the posterior stroma mirrors an increased abundance of lumican and dermatopontin (also called TRAMP, tyrosine-rich acidic matrix protein), a molecule first identified associated with decorin, which may reflect a functional association between these molecular components of the stroma [79].

These discoveries followed earlier analyses of articular cartilage which had showed a similarly increased incidence of KS-GAG in thicker cartilages and its progressive abundance in deeper layers [76, 77]. Those observations and correlations with morphometric analysis of cellular organelles prompted Scott and Stockwell to suggest that KS biosynthesis, in preference to that of CS/DS, was pre-eminent at tissue locations with low oxygen availability. NAD-dependent oxidation of the glucose precursor, uridine diphosphate glucuronic acid, to galactose in KS-GAG is not oxygen dependent, unlike its conversion to glucuronic acid in CS-GAG which thus cannot proceed under hypoxic conditions. NADH inhibits the oxidation step and so NAD:NADH ratios and cellular oxygen levels may regulate KS versus CS production.

The oxygen-lack hypothesis for KS-GAG biosynthesis has stood the test of time. Conformational similarities between KS and CS add weight to the view that they may be interchangeable structures fulfilling an equivalent functional role in provision of polyanionic matrix at tissue locations with different levels of nutrient supply [80–82]. Further support comes from pathological and clinical cases where corneal inflammation and neovascularisation have been found to involve reduction in KS-GAG in preference to CS/DS secretion [83, 84]. Also, KS biosynthetic activity by keratocytes in vitro is soon lost, again perhaps in response to increased oxygen availability. Subtle changes in oxygen concentration at increasing stromal depths may be a factor influencing different keratocyte subpopulations throughout the cornea [85]. Recently, considerable attention has focused on the corneal hypoxia known to be induced by contact lens wear primarily to facilitate the development of new materials with less influence upon corneal homeostasis [86, 87].

Matrix changes in gene-targeted KS null-mutants

In recent years, researchers have produced a number of gene-targeted mice with null mutations in KS-PG core proteins [88–91] or enzymes involved in the sulphation pathways of KS-GAGs [92]. Even though mouse cornea is not an ideal model for humans because it contains KS-GAG that is comparatively undersulphated [70, 71], investigations of the corneas of these animals have shown that mutations in various KS-PG core proteins can result in an altered collagen fibril assembly, with matrix changes most prevalent in the lumican-null genotype [93–95]. Structural changes in the corneas of lumican-null mice are manifest, and are pronounced in the deep stroma where they correspond to reduced corneal transparency. Notable in the lumican-null cornea is the appearance of pockets of abnormally large and irregularly-shaped collagen fibrils [93], lending weight to the argument that KS-PGs in the cornea associate with the fibril surface and help prevent collagen fibril aggregation. However, because keratocan expression is regulated by lumican expression, it is difficult to assign specific structural roles for different KS-PGs [96].

The mouse cornea is well formed at birth, and lumican is present in the early postnatal period [97]. Changes in stromal thickness, cell density and light scattering happen either side of eyelid opening (around postnatal day 12) in the normal mouse cornea [98]. The cornea of the lumican-null mouse, however, is thinner than normal [93], and transient stromal thickness changes at eye opening are not seen in this genotype [98], supporting the case for a role for lumican in normal developmental events leading to the establishment of the mature stroma in the mouse. Structural matrix differences have also been reported between wild-type and lumican-null mouse corneas at postnatal days 8 and 14 [99]. Furthermore, the defects in collagen fibril assembly seen in mature lumican-null mice [88, 93] are present at postnatal day 10, with the frequency of appearance of structurally abnormal collagen fibrils increasing by postnatal days 30 and 90 [97]. Thus, stromal abnormalities in lumican-null corneas are not late-evolving phenomena, but are early events in development that persist into adulthood.

Attempts have been made to rescue phenotype in the corneas of mice with KS-PG mutations, and some success has been had. Crossing lumican-null mice with mice which over-expressed lumican under the control of the keratocan promoter, for example, resulted in a small yet significant reduction of corneal haze, less structural matrix disturbance, and fewer large collagen fibrils as compared to the lumican-null situation, although a full return to the normal stromal structure was not achieved [100]. Cell-based therapy has also been investigated after it was shown that stem cells isolated from adult human corneal stroma were well tolerated when injected into the corneas of wild-type mice and remained viable for several months without fusing with host cells or eliciting an immune T-cell response [101]. Lumican and keratocan, moreover, were found to accumulate in these stem cell-injected corneas. Injection of human stromal stem cells into lumican-null mouse corneas minimised the collagen fibril alterations, and resulted in stromal thickness and transparency measurements which were within normal limits [101].

Studies have been initiated to try and uncouple the possible structural roles of the intact KS-PG and the sulphated GAG side chain. Genetically modified mice lacking a gene called Chst5, which encodes a mouse version of the human sulphotransferase enzyme (CGn6ST) that adds sulphate groups to KS [54], have been produced and analysed [92]. Mutant corneas possessed lumican core protein, but lacked immunochemically identifiable KS-GAG and were deficient in small fibril-associated KS-PG filaments. Corneas were thinner than normal and exhibited structural alterations which included a lower overall collagen fibril spacing and a more spatially disorganised fibrillar array, thus identifying the enzymatic sulphation of KS chains as instrumental in the establishment of the properly formed corneal stroma [92]. Biochemical analysis of corneal KS-GAG in the Chst5 sulphotransferase-deficient mouse cornea suggests that the length of the chain is reduced (Akama, T.O., unpublished observations), which, given the proposed influence of KS on stromal ultrastructure, might help explain the lower-than-normal average collagen fibril spacing.

KS in corneal development

KS has long been held to play an instrumental role in corneal embryogenesis. Anseth reported substantial changes in the chemical and physico-chemical properties of chick corneal GAGs around developmental day 14 [102]. Subsequent studies, including immunolocalisation with antibodies against specific sulphation motifs on KS-GAG [103–105], indicated that it is synthesised from as early as days 5–8 in development, with both low- and high-sulphated KS-GAG epitopes present. High- and low-sulphate epitopes may be present within single KS-GAG chains, and a switch in production of unsulphated to sulphated KS has been reported between developmental days 12 and 15 [106], and with the greatest increase in highly sulphated KS-GAG occurring around day 14 and afterwards [107].

Increasing KS-GAG sulphation during corneal development has been linked to increases in the activity of galactose-transferase, an enzyme involved in KS chain elongation [108], and to increases in concentrations of the KS sulphate donor, 3’-phosphoadenosine-5’-phosphosulphate (PAPS) [109]. The increase in highly sulphated KS-GAG in the final week of chick development before hatching was recently found to be disproportionate to the respective increase in collagen synthesis, measured by hydroxyproline content [110]. Collagen fibrils deposited in the extracellular space at cell surfaces are probably already decorated with sulphated KS-PGs as shown by immunoelectron microscopy [105], perhaps with full occupancy of binding sites, but at early developmental stages KS-GAG chains have not attained full length or full sulphation status. Increasing sulphation may be a reflection of continued addition of sulphate to specific residues on KS poly-N-acetyllactosamine following elongation of KS chains [54, 56, 111]. The highly sulphated KS-GAG epitope identified by antibody 5D4 can be detected in chick cornea in association with collagen fibrils from developmental day 10, increasing to day 18, and surpassing a lower sulphated epitope identified by antibody 1B4 [105, 110]. Similarly, more detailed analysis by electrospray ionisation tandem mass spectrometry revealed increased disulphated disaccharides over monosulphated disaccharides of KS-GAG during this period [112].

Sulphation of KS-GAG will directly affect the polarity of KS-PG molecules, influencing their water-binding properties and thus tissue hydration. These accumulated studies have given rise to the idea that KS-PG sulphation might influence the structural reorganisation of the stromal matrix as it first swells, then dehydrates, thins and becomes transparent [110]. The changing levels of KS-PGs and changing sulphation patterns of KS-GAGs during development are also likely to be influenced significantly by temporal alterations in mRNA levels for the different KS-PG core proteins. This is evidenced mainly through a substantial increase in the sulphation of lumican between days 12 and 15 of development [106, 113]. Changes in KS-GAG sulphation with development in the chick do not appear to happen uniformly across the corneal thickness, however, and conflicting evidence exists in the literature, with some workers suggesting an anterior-to-posterior accumulation of sulphated KS-GAG based on immunohistochemistry [103], and other groups disputing this [114]. It seems likely that these discrepancies may derive at least in part from the technical challenges associated with the detection of KS disaccharide chains which, in addition to their highly variable sulphation patterns, can exhibit considerable heterogeneity in disaccharide composition (explained in [115]).

The respective roles in corneal development of sulphated KS-GAG associated with lumican, keratocan and mimecan core proteins, as potential regulators of stromal hydration and collagen fibril spacing, remain unclear. Sulphated KS on lumican progressively accumulates by embryonic day 15 in the chick cornea [106], even though lumican mRNA expression remains high throughout development [113]. Keratocan is substituted with three KS-GAG chains in (bovine) cornea, compared to only one on lumican and mimecan [116], and may be capable pro rata of supporting a higher local sulphate concentration than lumican. However, in mature tissue, lumican is by far the more abundant KS-PG and is thought to carry most of the sulphated KS-GAG [113]. Keratocan protein is present in the chick cornea throughout development, where it is restricted to the anterior stroma and absent from Bowman’s layer, perhaps suggesting a link with the formation of the distinctive matrix architectures in these specialised regions of the cornea [117].

KS in stromal wound healing

The PG complement of the rabbit corneal stroma resembles that of the human [118], and much of the initial contemporary evidence regarding stromal wound healing is derived from the work of Cintron and colleagues in their studies of the regeneration of full-thickness penetrating wounds in rabbit corneas [119–127]. Two weeks after injury collagen fibrils in the opaque, healing rabbit cornea were in disarray, but thereafter progressively regained a semblance of spatial order as transparency returned [120–122]. Biochemical analyses indicated that 2-week-old corneal scars lacked intact KS-GAG, and contained hyaluronic acid as well as CS-PGs with normally sized, but overly sulphated, GAG chains [123]. At 4 months, low but detectable levels of intact KS-PGs were found as the PG population recovered, although even 1 year after wounding the biochemistry indicated that KS levels had not been restored entirely to normal. Subsequent immunoanalysis of PGs in full-thickness rabbit wounds 2, 6 and 8 weeks after injury, however, indicated the presence of KS-GAG in early scar tissue, and also showed that the chains were likely associated with the same core protein as were the chains in normal corneal KS-PG [124]. Nevertheless, changes in the antigenic properties of KS were seen in the scars, and this was interpreted as a structural change in KS-GAGs with wounding, most likely a decreased sulphation of the KS chains [124]. Electron histochemical analyses of full-thickness scars in the weeks after wounding also provided evidence for chemically altered, probably undersulphated, KS-PGs [125], and this appeared to be the case, too, after a superficial wound [126]. Similarities with PG changes seen in the developing cornea led Cintron and associates to suggest that the healing adult cornea partially recapitulated the chemical composition of PGs in embryogenesis [125, 127]. The results of work on corneal scar tissue are supported and enhanced by in vitro cell culture studies which showed that KS synthesised by fibroblasts and myofibroblasts had shorter GAG chains and a lesser degree of sulphation compared to KS synthesised by quiescent keratocytes [128]. Experiments on corneal healing in mice show that epithelial resurfacing was complete 2–5 days after a partial epithelial debridement or an alkali burn, whereas conjunctival resurfacing occurred 2 weeks after a total epithelial scrape [129]. After both types of wound a decrease in keratocan and lumican expression was noted 6 weeks after injury which increased at the 12-week timepoint, implying that the cells repopulating the injured stroma regain the characteristic function of keratocytes [128, 129]. In wounded mouse cornea, too, lumican is understood to affect cell proliferation and apoptosis [130] and the nature of immune or inflammatory signals to cells [131].

It is of potential clinical relevance to understand corneal healing dynamics after corrective laser surgery [132, 133], and several studies have examined PGs after photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) and laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK). Unusually large PG filaments have been observed in lamellar wounds in rabbits 2 weeks after surgery [134], as well as in human corneas several years after LASIK [135, 136], but these are believed to be CS/DS-PGs. This would be consistent with several observations, including the higher charge density of DS-PGs in rabbit corneal scars [126], the increased chain length and sulphation status of CS/DS-GAGs in primary cultures of fibroblasts with a wound healing phenotype [128], and reports that immunohistochemically-detectable KS-GAG was present at normal or reduced levels at and around the LASIK scar [136]. One week after anterior surface excimer laser photoablation of monkey corneas designed to mimic myopic PRK corrections of between −2 and −8 Diopters, sulphated KS-GAG was identified in the stroma when examined immunohistochemically. Two weeks later, however, there was an absence of positive signal for KS-GAG. Six and 12 weeks after laser treatment, KS immunoreactivity had returned and was judged to be more intense than before surgery in a narrow subepithelial band [137]. Tissue obtained by laser capture microdissection from the stromal graft-host interface of postmortem human corneas 4–6.5 years after LASIK and analysed by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry disclosed that concentrations of monosulphated GlcNAc(6S)-beta-1,3-Gal and disulphated Gal (6S)-beta-1,4-GlcNAc(6S) disaccharides of KS were significantly lower than normal [138]. No difference, however, was found in levels of non-sulphated KS disaccharides. These findings, aligned to those of others, led the investigators from Conrad’s laboratory [138] to speculate that the reduction of sulphated KS-GAG at the LASIK wound margin, and the attendant increase in CS/DS-GAG, might serve to alter the local hydration of the stroma which is seen at the graft–host interface after LASIK [139].

As well as roles in stromal wound healing, KS-PGs play a role in the wound healing properties of the corneal epithelial and endothelial cell layers [140–144].

There is an emerging body of work concentrated on attempts to bioengineer corneal stroma substitutes for future use in corneal surgery, either alone or in conjunction with ex vivo expanded epithelial or endothelial cell layers. There is probably not a pressing need to engineer a full thickness cornea with both epithelial and endothelial layers attached because lamellar surgeries are proving increasingly successful. Bio-engineered epithelial cell constructs are already in clinical use [145], and endothelial constructs are close to use [146, 147]. The production of a usable partial thickness corneal stroma is proving more challenging, however, owing to the need to generate a strong transparent matrix. Collagen hydrogels have useful transparency characteristics [148], but efforts are underway to generate constructs, often seeded with keratocytes, to mimic corneal behaviour [149–151], and inclusion of functional KS-GAG in such tissue replacements is presumably desirable. Sizeable challenges remain, however, in this regard, not least because the biosynthesis of KS-GAG in vitro and its ability to function and interact with collagen is influenced by a multitude of extraneous factors. Amongst these, the nature of the matrix or substratum in/on which keratocytes are cultured, the presence of agents such as ascorbate and insulin [152, 153], as well as a complexity of growth factors and signalling molecules [154–159] are already recognised as important.

KS and corneal disease

Reduction of highly-sulphated KS-GAG levels in the stroma associated with corneal pathologies and inflammatory conditions is well documented [83, 160], supporting the view that proinflammatory mediators serve an important role in suppression of KS biosynthesis [11]. Recent studies showed that one route for downregulation of KS may be through the Wnt signalling pathway, with nuclear translocation of ß-catenin, following disruption of functional Cadherin11-containing adherens junctions between keratocytes [161].

A spectrum of inherited diseases—the mucopolysaccharidoses—is characterised by progressive opacification of the cornea and excessive storage of GAGs. These arise most commonly from deficiencies in enzymes involved in the degradation or synthesis of carbohydrates. Morquio syndrome is a rare autosomal-recessive mucopolysaccharidosis, first identified in 1929 [162], in which reduced activity of N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulphate-sulphatase or beta-galactosidase leads to KS and CS-6-sulphate accumulation in connective tissues, including cornea [163]. Several ultrastructural studies on corneas of these patients have revealed membranous inclusions within keratocytes and dense pericellular fibrogranular deposits, plus disrupted lamellae [164–166]. Some PGs, localised with the cationic dye Cuprolinic blue, appeared twice their normal length [167], although it is unknown whether these are KS-containing structures. Liver-accumulated KS in Morquio syndrome type A exhibited enlarged oligosaccharides with galactosamine accounting for 10% of hexosamine [168]. In another of the mucopolysaccharidoses with KS involvement (type VI; Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome type B), the cornea of a patient examined after penetrating keratoplasty showed high levels of immunohistochemically identifiable KS-GAG in the deep stroma as well as in vacuolated keratocytes, presumably as a consequence of a deficiency of aryl sulphatase B [169].

In humans, there are two known genetic diseases resulting from the failure of normal corneal KS-GAG production. One is cornea plana caused by mutations on KERA [170], a gene encoding keratocan [171]; the other is macular corneal dystrophy (MCD) caused by mutations on CHST6, which encodes CGn6ST [172]. Both conditions seem to arise from loss-of-function mutations in the genes based on the recessive inheritance patterns in the affected families. Cornea plana patients have hazy corneas which are less convex, and thus possess less refractive power, than normal. Experiments with keratocan-null mice indicated that keratocan core protein has a role in the establishment of a properly formed stroma [91, 95], but it is not understood from a functional point of view why mutations in KERA in humans lead to the clinical phenotype seen in cornea plana. It is, of course, possible that the disease may be caused by dysfunction of the core protein itself or some knock-on effects of that, rather than an abnormal KS-GAG production.

In MCD, affected individuals develop progressive corneal clouding, normally with coalescing focal opacities [173, 174]. Onset is typically around puberty and progressive loss of vision often necessitates a corneal graft. By immunological analyses, MCD has been categorised into three main groups, type I, type IA and type II. Sulphated KS-GAG which is present in the corneas of healthy individuals can be detected by the 5D4 monoclonal antibody on immunohistochemical analyses of postoperative corneal tissue biopsies. It is also detectable by ELISA in the serum, in which the majority of KS-GAG derives from cartilage. KS-GAG, however, is absent from serum and cornea in majority of MCD patients, and these are categorised as MCD type I [46]. A minor subset of patients are categorised as MCD type II based on detectable-to-normal levels of 5D4-positive KS-GAG in their serum and cornea [175]. MCD type IA patients have no detectable KS-GAG in their serum, but on immunohistochemistry show 5D4-positive signal in the cornea which is restricted to keratocytes and not evident in the extracellular matrix [176]. The immunochemical differences in MCD are not distinguishable in the disease’s clinical presentation, which is confined to the cornea, with no apparent symptoms in other tissues such as cartilage. Collagen fibrils in MCD corneas are more closely spaced than normal, which might contribute to the thin cornea reported clinically [177, 178]. Perhaps a truncated KS-GAG underlies this anomaly in a similar way that short GAG chains in Chst5-null mice might lead to a closer-than-normal fibril spacing [92]. It is also of interest to note that, even though collagen intermolecular spacing within the fibril is not altered in MCD [179], occasional pockets of large diameter collagen fibrils are seen in the stroma in MCD type I and type II [180–182]. The molecular mechanisms which lead to the clinical presentation of MCD are yet to be fully elucidated, but work is ongoing using various KS-GAG markers to help our understanding of this disease [47, 183, 184].

Summary

KS was first discovered in cornea, and despite the fact that it is now known to be a constituent of a number of other tissues, interest in its role in cornea continues unabated to this day. Primarily, this is because of the undoubted influence of KS-GAG on corneal structure and function. The intricacies of KS-GAG chain elongation, sulphation status, enzymatic processing, interactions with collagen, and the likely symbiotic relationship with CS/DS-GAGs are important matters which are yet to be fully resolved.

Acknowledgments

Our research programmes are funded by BBSRC Project Grant BB/D001919/1 (UK), NIH/NEI Research Grant EY014620 (USA), MRC Programme Grant G0600755 (UK), and EPSRC Project Grant EP/F034970/1 (UK).

References

- 1.Meyer K, Linker A, Davidson EA, Weissmann B. The mucopolysaccharides of bovine cornea. J Biol Chem. 1953;205:611–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassell JR, Newsome DA, Krachmer JH, Rodrigues MM. Macular corneal dystrophy: failure to synthesize a mature keratan sulfate proteoglycan. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:3705–3709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hassell JR, Cintron C, Kublin C, Newsome DA. Proteoglycan changes during restoration of transparency in corneal scars. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983;222:362–369. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blochberger TC, Vergnes JP, Hempel J, Hassell JR. cDNA to chick lumican (corneal keratan sulfate proteoglycan) reveals homology to the small interstitial proteoglycan gene family and expression in muscle and intestine. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:347–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corpuz LM, Funderburgh JL, Funderburgh ML, Bottomley GS, Prakash S, Conrad GW. Molecular cloning and tissue distribution of keratocan. Bovine corneal keratan sulfate proteoglycan 37A. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9759–9763. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Funderburgh JL, Corpuz LM, Roth MR, Funderburgh ML, Tasheva ES, Conrad GW. Mimecan, the 25-kDa corneal keratan sulfate proteoglycan, is a product of the gene producing osteoglycin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28089–28095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.28089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poole RA. Proteoglycans in health and disease: structures and functions. Biochem J. 1986;236:1–14. doi: 10.1042/bj2360001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Funderburgh JL, Funderburgh ML, Mann MM, Conrad GW. Physical and biological properties of keratan sulphate proteoglycan. Biochem Soc Trans. 1991;19:871–876. doi: 10.1042/bst0190871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardingham TE, Fosang AJ. Proteoglycans: many forms and many functions. FASEB J. 1992;6:861–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott JE. Supramolecular organization of extracellular matrix glycosaminoglycans, in vitro and in the tissues. FASEB J. 1992;6:2639–2645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Funderburgh JL. Keratan sulphate: structure, biosynthesis, and function. Glycobiology. 2000;10:951–958. doi: 10.1093/glycob/10.10.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Funderburgh JL. Keratan sulphate biosynthesis. IUBMB Life. 2002;54:187–194. doi: 10.1080/15216540214932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chakravarti S. Functions of lumican and fibromodulin: lessons from knockout mice. Glycoconj J. 2002;19:287–293. doi: 10.1023/A:1025348417078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chakravarti S. Focus on molecules: keratocan (KERA) Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:183–184. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kao WW, Funderburgh JL, Xia Y, Liu CY, Conrad GW. Focus on molecules: lumican. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kao WW, Liu CY. Roles of lumican and keratocan on corneal transparency. Glycoconj J. 2002;19:275–285. doi: 10.1023/A:1025396316169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hogan MJ, Alvarado JA, Weddell JE (1971) The cornea. In: Histology of the human eye. An Atlas and textbook, chapter 3. Saunders, Philadelphia, p 89

- 18.Komai Y, Ushiki T. The three-dimensional organization of collagen fibrils in the human cornea and sclera. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:2244–2258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meek KM, Leonard DW. Ultrastructure of the corneal stroma: a comparative study. Biophys J. 1993;64:273–280. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81364-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quantock AJ, Meek KM, Fullwood NJ, Zabel RW. Scheie’s syndrome: the architecture of corneal collagen and distribution of corneal proteoglycans. Can J Ophthalmol. 1993;28:266–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craig AS, Robertson JG, Parry DA. Preservation of corneal collagen fibril structure using low-temperature procedures for electron microscopy. J Ultrastruct Mol Struct Res. 1986;96:172–175. doi: 10.1016/0889-1605(86)90018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maurice DM. The structure and transparency of the corneal stroma. J Physiol. 1957;136:263–286. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1957.sp005758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hart RW, Farrell RA. Light scattering in the cornea. J Opt Soc Am. 1969;59:766–774. doi: 10.1364/josa.59.000766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benedek GB. Theory and transparency of the eye. Appl Opt. 1971;10:459–473. doi: 10.1364/AO.10.000459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sayers Z, Whitburn SB, Koch MHJ, Meek KM, Elliott GF. Synchrotron X-ray diffraction study of corneal stroma. J Mol Biol. 1982;160:593–607. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90317-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Worthington CR. The structure of the cornea. Quart Rev Biophys. 1984;17:423–451. doi: 10.1017/s003358350000487x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Worthington CR, Inouye H. X-ray diffraction study of the cornea. Int J Biol Macromol. 1985;7:2–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freund DE, McCally RL, Farrell RA. Direct summation of fields for light scattering by fibrils with applications to normal corneas. Appl Opt. 1986;25:2739–2746. doi: 10.1364/ao.25.002739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Møller-Pedersen T, Ehlers N. A three-dimensional study of the human corneal keratocyte density. Curr Eye Res. 1995;14:459–464. doi: 10.3109/02713689509003756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Møller-Pedersen T. A comparative study of human corneal keratocyte and endothelial cell density during aging. Cornea. 1997;16:333–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaye GI. Stereologic measurement of cell volume fraction of rabbit corneal stroma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1969;82:792–794. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1969.00990020784013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jester JV, Møller-Pedersen T, Huang J, Sax CM, Kays WT, Cavangh HD, Petroll WM, Piatigorsky J. The cellular basis of corneal transparency: evidence for ‘corneal crystallins’. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:613–622. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.5.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jester JV. Corneal crystallins and the development of cellular transparency. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bettelheim FA, Plessy B. The hydration of proteoglycans of bovine cornea. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;381:203–214. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(75)90202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bettelheim FA, Goetz D. Distribution of hexosamines in bovine cornea. Invest Ophthalmol. 1976;15:301–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castoro JA, Bettelheim AA, Bettelheim FA. Water gradients across bovine cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1988;29:963–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rada J, Cornuet PK, Hassell JR. Regulation of corneal collagen fibrillogenesis in vitro by corneal proteoglycan (lumican and decorin) core proteins. Exp Eye Res. 1993;56:635–648. doi: 10.1006/exer.1993.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borcherding MS, Blacik LJ, Sittig RA, Bizzell JW, Breen M, Weinstein HG. Proteoglycans and collagen fibre organization in human corneoscleral tissue. Exp Eye Res. 1975;21:59–70. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(75)90057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oeben M, Keller R, Stuhlsatz HW, Greiling H. Constant and variable domains of different disaccharide structure in corneal keratan sulphate chains. Biochem J. 1987;248:85–93. doi: 10.1042/bj2480085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tai GH, Huckerby TN, Nieduszynski IA. Multiple non-reducing chain termini isolated from bovine corneal keratan sulfates. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23535–23546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tai GH, Nieduszynski IA, Fullwood NJ, Huckerby TN. Human corneal keratan sulfates. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28227–28231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plaas AH, West LA, Thonar EJ, Karcioglu ZA, Smith CJ, Klintworth GK, Hascall VC. Altered fine structures of corneal and skeletal keratan sulfate and chondroitin/dermatan sulfate in macular corneal dystrophy. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39788–39796. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103227200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nilsson B, Nakazawa K, Hassell JR, Newsome DA, Hascall VC. Structure of oligosaccharides and the linkage region between keratan sulfate and the core protein on proteoglycans from monkey cornea. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:6056–6063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caterson B, Christner JE, Baker JR. Identification of a monoclonal antibody that specifically recognises corneal and skeletal keratan sulfate. Monoclonal antibodies to cartilage proteoglycan. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:8848–8854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mehmet H, Scudder P, Tang PW, Hounsell EF, Caterson B, Feizi T. The antigenic determinants recognised by three monoclonal antibodies to keratan sulphate involve sulphated hepta- or larger oligosaccharides of the poly(N-acetyllactosamine) series. Eur J Biochem. 1986;157:385–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thonar EJ, Meyer RF, Dennis RF, Lenz ME, Maldonado B, Hassell JR, Hewitt AT, Stark WJ, Stock EL, Kuettner KE, Klintworth GK. Absence of normal keratan sulfate in the blood of patients with macular corneal dystrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;102:561–569. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(86)90525-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Young RD, Akama TO, Liskova P, Ebenezer ND, Allan B, Kerr B, Caterson B, Fukuda MN, Quantock AJ. Differential immunogold localisation of sulphated and unsulphated keratan sulphate proteoglycans in normal and macular dystrophy cornea using sulphation motif-specific antibodies. Histochem Cell Biol. 2007;127:115–120. doi: 10.1007/s00418-006-0228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Akhtar S, Kerr BC, Hayes AJ, Hughes CE, Meek KM, Caterson B. Immunochemical localization of keratan sulfate proteoglycans in cornea, sclera, and limbus using a keratanase-generated neoepitope monoclonal antibody. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2424–2431. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fukuda MN, Matsumura G. Endo-beta-galactosidase of Escherichia freundii. Purification and endoglycosidic action on keratan sulfates, oligosaccharides, and blood group active glycoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:6218–6225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakagawa H, Yamada T, Chien JL, Gardas A, Kitamikado M, Li SC, Li YT. Isolation and characterization of an endo-beta-galactosidase from a new strain of Escherichia freundii . J Biol Chem. 1980;255:5955–5959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakazawa K, Suzuki N, Suzuki S. Sequential degradation of keratan sulfate by bacterial enzymes and purification of a sulfatase in the enzymatic system. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:905–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakazawa K, Ito M, Yamagata T, Suzuki S (1989) Substrate specificity of keratan sulphate-degrading enzymes (endo-ß-galactosidase, keratanase and keratanase II) from microorganisms. In: Greiling H, Scott JE (eds) Keratan sulphate: chemistry, biology, chemical pathology. Biochemical Society, London, pp 99–110

- 53.Fukuta M, Inazawa J, Torii T, Tsuzuki K, Shimada E, Habuchi O. Molecular cloning and characterization of human keratan sulfate Gal-6-sulfotransferase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32321–32328. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Akama TO, Nakayama J, Nishida K, Hiraoka N, Suzuki M, McAuliffe J, Hindsgaul O, Fukuda M, Fukuda MN. Human corneal GlcNac 6-O-sulfotransferase and mouse intestinal GlcNac 6-O-sulfotransferase both produce keratan sulfate. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16271–16278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009995200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fukuda M, Hiraoka N, Akama TO, Fukuda MN. Carbohydrate-modifying sulfotransferases: structure, function, and pathophysiology. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47747–47750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100049200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akama TO, Misra AK, Hindsgaul O, Fukuda MN. Enzymatic synthesis in vitro of the disulfated disaccharide unit of corneal keratan sulfate. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42505–42513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207412200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Torii T, Fukuta M, Habuchi O. Sulfation of sialyl N-acetyllactosamine oligosaccharides and fetuin oligosaccharides by keratan sulfate Gal-6-sulfotransferase. Glycobiology. 2000;10:203–211. doi: 10.1093/glycob/10.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seko A, Dohmae N, Takio K, Yamashita K. Beta 1, 4-galactosyltransferase (beta 4GalT)-IV is specific for GlcNAc 6-O-sulfate. Beta 4GalT-IV acts on keratan sulfate-related glycans and a precursor glycan of 6-sulfosialyl-Lewis X. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9150–9158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211480200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seko A, Yamashita K. beta1, 3-N-Acetylglucosaminyltransferase-7 (beta3Gn-T7) acts efficiently on keratan sulfate-related glycans. FEBS Lett. 2004;556:216–220. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01440-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kitayama K, Hayashida Y, Nishida K, Akama TO. Enzymes responsible for synthesis of corneal keratan sulfate glycosaminoglycans. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30085–30096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703695200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shiraishi N, Natsume A, Togayachi A, Endo T, Akashima T, Yamada Y, Imai N, Nakagawa S, Koizumi S, Sekine S, Narimatsu H, Sasaki K. Identification and characterization of three novel beta 1, 3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferases structurally related to the beta 1, 3-galactosyltransferase family. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3498–3507. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004800200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scott JE, Orford CR, Hughes EW. Proteoglycan-collagen arrangements in developing rat tail tendon. An electron microscopical and biochemical investigation. Biochem J. 1981;195:573–581. doi: 10.1042/bj1950573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Scott JE, Haigh M. ‘Small’-proteoglycan:collagen interactions: keratan sulphate proteoglycan associates with rabbit corneal collagen fibrils at the ‘a’ and ‘c’ bands. Biosci Rep. 1985;5:765–774. doi: 10.1007/BF01119875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meek KM, Elliott GF, Nave C. A synchrotron X-ray diffraction study of bovine cornea stained with cupromeronic blue. Coll Relat Res. 1986;6:203–218. doi: 10.1016/s0174-173x(86)80026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maurice D. Clinical physiology of the cornea. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1962;2:561–572. doi: 10.1097/00004397-196210000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Scott JE. Morphometry of cupromeronic blue-stained proteoglycan molecules in animal corneas, versus that of purified proteoglycans stained in vitro, implies that tertiary structures contribute to corneal ultrastructure. J Anat. 1992;180:155–164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Muller LJ, Pels E, Schurmans LRHM, Vrensen GFJM. A new three-dimensional model of the organization of proteoglycans and collagen fibrils in the human corneal stroma. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:493–501. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Knupp C, Pinali C, Lewis PN, Parfitt GJ, Young RD, Meek KM, Quantock AJ (2009) The architecture of the cornea and structural basis of its transparency. Adv Prot Chem Struct Biol (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Lewis PN, Pinali C, Young RD, Meek KM, Quantock AJ, Knupp C (2010) Structural interactions between collagen and proteoglycans are elucidated by three-dimensional electron tomography of bovine cornea. Structure (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Scott JE, Bosworth TR. A comparative biochemical and ultrastructural study of proteoglycan-collagen interactions in corneal stroma. Biochem J. 1990;270:491–497. doi: 10.1042/bj2700491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Young RD, Tudor D, Hayes AJ, Kerr B, Hayashida Y, Nishida K, Meek KM, Caterson B, Quantock AJ. Atypical composition and ultrastructure of proteoglycans in the mouse corneal stroma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:1973–1978. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takahashi T, Cho HI, Kublin CL, Cintron C. Keratan sulphate and dermatan sulphate proteoglycans associate with trype VI collagen in fetal rabbit cornea. J Histochem Cytochem. 1993;41:1447–1457. doi: 10.1177/41.10.8245404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Haigh M, Gibson S, Scott JE. Keratan sulphate and the ultrastructure of the cornea: a comparison of rabbit, rat and mouse. Biochem Soc Trans. 1987;15:711–712. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Scott JE, Haigh M, Ali P. Keratan sulphate is unevenly distributed from back to front of bovine cornea. Biochem Soc Trans. 1988;16:333–334. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stockwell RA. Changes in the acid glycosaminoglycan content of the matrix of ageing human articular cartilage. Ann Rheum Dis. 1970;29:509–515. doi: 10.1136/ard.29.5.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stockwell RA. Morphometry of cytoplasmic components of mammalian articular chondrocytes and corneal keratocytes: species and zonal variations of mitochondria in relation to nutrition. J Anat. 1991;175:251–261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stockwell RA, Scott JE. Observations on the acid glycosaminoglycan (mucopolysaccharide) content of the matrix of aging cartilage. Ann Rheum Dis. 1965;24:341–350. doi: 10.1136/ard.24.4.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Scott JE. Proteoglycan-fibrillar collagen interactions. Biochem J. 1988;252:313–323. doi: 10.1042/bj2520313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cooper LJ, Bentley AJ, Nieduszynski IA, Talabani S, Thomson A, Utani A, Shinkai H, Fullwood NJ, Brown GM. The role of dermatopontin in the stromal organization of the cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3303–3310. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Scott JE, Haigh M. Keratan sulphate and the ultrastructure of cornea and cartilage: a ‘stand-in’ for chondroitin sulphate in conditions of oxygen lack? J Anat. 1988;158:95–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Scott JE. Chondroitin sulphate and keratan sulphate are almost isosteric. Biochem J. 1991;275:267–268. doi: 10.1042/bj2750267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Scott JE. Keratan sulphate—a ‘reserve’ polysaccharide. Eur J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1994;32:217–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Funderburgh JL, Funderburgh ML, Rodrigues MM, Krachmer JH, Conrad GW. Altered antigenicity of keratan sulfate proteoglycan in selected corneal diseases. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31:419–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rodrigues M, Nirankari V, Rajagopalan S, Jones K, Funderburgh JL. Clinical and histopathologic changes in the host cornea after epikeratoplasty for keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;114:161–170. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73980-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hahnel C, Somodi S, Weiss DG, Guthoo RF. The keratocyte network of human cornea: a three-dimensional study using confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscopy. Cornea. 2000;19:185–193. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200003000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Alvord LA, Hall WJ, Keyes LD, Morgan CF, Winterton LC. Corneal oxygen distribution with contact lens wear. Cornea. 2007;26:654–664. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31804f5a22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fink B, Hill RM. Corneal oxygen uptake—a review of polarographic techniques, applications and variables. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2006;29:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chakravarti S, Magnuson T, Lass JH, Jepsen KJ, LaMantia C, Carroll H. Lumican regulates collagen fibril assembly: skin fragility and corneal opacity in the absence of lumican. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1277–1286. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.5.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Saika S, Shiraishi A, Liu CY, Funderburgh JL, Kao CW, Converse RL, Kao WW. Role of lumican in the corneal epithelium during wound healing. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2607–2612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tasheva ES, Koester A, Paulsen AQ, Garrett AS, Boyle DL, Davidson HJ, Song M, Fox N, Conrad GW. Mimecan/osteoglycin-deficient mice have collagen fibril abnormalities. Mol Vis. 2002;8:407–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liu C-Y, Birk DE, Hassell JR, Kane B, Kao WW-Y. Keratocan-deficient mice display alterations in corneal structure. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21672–21677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301169200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hayashida Y, Akama TO, Beecher N, Lewis P, Young RD, Meek KM, Kerr B, Hughes CE, Caterson B, Tanigami A, Nakayama J, Fukada MN, Tano Y, Nishida K, Quantock AJ. Matrix morphogenesis in cornea is mediated by the modification of keratan sulfate by GlcNAc 6-O sulfotransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13333–13338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605441103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chakravarti S, Petroll WM, Hassell JR, Jester JV, Lass JH, Paul J, Birk DE. Corneal opacity in lumican-null mice: defects in collagen fibril structure and packing in the posterior stroma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:3365–3373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Quantock AJ, Meek KM, Chakravarti S. An x-ray diffraction investigation of corneal structure in lumican-deficient mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1750–1756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Meek KM, Quantock AJ, Boote C, Liu CY, Kao WW-Y. An x-ray scattering investigation of corneal structure in keratocan-deficient mice. Matrix Biol. 2003;22:467–475. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(03)00081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Carlson EC, Liu C-Y, Chikama T-I, Hayashi Y, Kao CW-C, Birk DE, Funderburgh JL, Jester JV, Kao WW. Keratocan, a cornea-specific keratan sulphate proteoglycan, is regulated by lumican. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25541–25547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500249200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chakravarti S, Zhang G, Chervoneva I, Roberts L, Birk DE. Collagen fibril assembly during postnatal development and dysfunctional regulation in the lumican-deficient murine cornea. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:2493–2506. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Song J, Lee YG, Houston J, Petroll WM, Chakravarti S, Cavanagh HD, Jester JV. Neonatal corneal stromal development in the normal and lumican-deficient mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:548–557. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Beecher N, Chakravarti S, Joyce S, Meek KM, Quantock AJ. Neonatal development of the corneal stroma in wild-type and lumican-null mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:146–150. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Meij JT, Carlson EC, Wang L, Liu CY, Jester JV, Birk DE, Kao WW. Targeted expression of a lumican transgene rescues corneal deficiencies in lumican-null mice. Mol Vis. 2007;13:2012–2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Du Y, Carlson EC, Funderburgh ML, Birk DE, Pearlman E, Guo N, Kao WW, Funderburgh JL. Stem cell therapy restores transparency to defective murine corneas. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1635–1642. doi: 10.1002/stem.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Anseth A. Glycosaminoglycans in the developing corneal stroma. Exp Eye Res. 1961;1:116–121. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(61)80016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Funderburgh JL, Caterson B, Conrad GW. Keratan sulfate proteoglycan during embryonic development of the chicken cornea. Dev Biol. 1986;116:267–277. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Takahashi I, Nakamura Y, Hamada Y, Nakazawa K. Immunohistochemical analysis of proteoglycan biosynthesis during early development of the chicken cornea. J Biochem. 1999;126:804–814. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Young RD, Gealy EC, Liles M, Caterson B, Ralphs JR, Quantock AJ. Keratan sulfate glycosaminoglycan and the association with collagen fibrils in rudimentary lamellae in the developing avian cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3083–3088. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cornuet PK, Blochberger TC, Hassell JR. Molecular polymorphism of lumican during corneal development. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:870–877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hart GW. Biosynthesis of glycosaminoglycans during corneal development. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:6513–6521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cai CX, Gibney E, Gordon MK, Marchant JK, Birk DE, Linsenmayer TF. Characterization and developmental regulation of avian corneal-1, 4-galactosyltransferase mRNA. Exp Eye Res. 1996;63:193–200. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Conrad GW, Woo ML. Synthesis of 3’-phosphoadenosine-5’-phosphosulfate (PAPS) increases during corneal development. J Biol Chem. 1979;255:3086–3091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Liles M, Palka BP, Harris A, Kerr B, Hughes CE, Young RD, Meek KM, Caterson B, Quantock AJ (2009) Differential relative sulphation of keratan sulfate glycosaminoglycan in the chick cornea during embryonic development. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 111.Keller R, Stuhlsatz HW, Greiling H. Sulphation, chain elongation and chain termination in keratan sulphate biosynthesis. In: Greiling H, Scott JE, editors. Keratan sulphate: chemistry, biology and chemical pathology. London: The Biochemical Society; 1989. pp. 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhang Y, Schmack I, Dawson DG, Grossniklaus HE, Conrad AH, Kariya Y, Suzuki K, Edelhauser HF, Conrad GW. Keratan sulfate and chondroitin/dermatan sulfate in maximally recovered hypocellular stromal interface scars of postmortem human LASIK corneas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2390–2396. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Dunlevy JR, Beales MP, Berryhill BL, Cornuet PK, Hassell JR. Expression of the keratan sulfate proteoglycans lumican, keratocan and osteoglycin/mimecan during chick corneal development. Exp Eye Res. 2000;70:349–362. doi: 10.1006/exer.1999.0789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Nakazawa K, Suzuki S, Wada K, Nakazawa K. Proteoglycan synthesis by corneal explants from developing embryonic chicken. J Biochem. 1995;117:707–718. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Scott JE, Caterson B. Postscript on possum cartilage and oxygen; what is keratan sulphate? J Anat. 1998;192:299–301. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1998.19220299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Funderburgh JL, Funderburgh ML, Mann MM, Conrad GW. Arterial lumican. Properties of a corneal-type keratan sulfate proteoglycan from bovine aorta. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:24773–24777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gealy EC, Kerr BC, Young RD, Tudor D, Hayes AJ, Hughes CE, Caterson B, Quantock AJ, Ralphs JR. Differential expression of the keratan sulphate proteoglycan, keratocan, during chick corneal embryogenesis. Histochem Cell Biol. 2007;128:551–555. doi: 10.1007/s00418-007-0332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gregory JD, Coster L, Damle SP. Proteoglycans of rabbit corneal stroma. Isolation and partial characterization. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:6965–6970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cintron C, Schneider H, Kublin CL. Corneal scar formation. Exp Eye Res. 1973;17:251–259. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(73)90176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Cintron C, Kublin CL. Regeneration of corneal tissue. Dev Biol. 1977;61:346–357. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Cintron C, Hassinger LC, Kublin CL, Cannon DJ. Biochemical and ultrastructural changes in collagen during corneal wound healing. J Ultrastruct Res. 1978;65:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(78)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Rawe IM, Meek KM, Leonard DW, Takahashi T, Cintron C. Structure of corneal scar tissue: an X-ray diffraction study. Biophys J. 1994;67:1743–1748. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80648-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hassell JR, Cintron C, Kublin C, Newsome DA. Proteoglycan changes during restoration of transparency in corneal scars. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983;222:362–369. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Funderburgh JL, Cintron C, Covington HI, Conrad GW. Immunoanalysis of keratan sulfate proteoglycan from corneal scars. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci. 1988;29:1116–1124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Cintron C, Covington HI, Kublin CL. Morphologic analyses of proteoglycans in rabbit corneal scars. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31:1789–1798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Rawe IM, Tuft SJ, Meek KM. Proteoglycan and collagen morphology in superficially scarred rabbit cornea. Histochem J. 1992;24:311–318. doi: 10.1007/BF01046162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Cintron C, Gregory JD, Damle SP, Kublin CL. Biochemical analysis of proteoglycans in rabbit corneal scars. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31:1975–1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Funderburgh JL, Mann MM, Funderburgh ML. Keratocyte phenotype mediates proteoglycan structure: a role for fibroblasts in corneal fibrosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45629–45637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303292200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]