Abstract

Research involving estrogen and progesterone receptors (ER and PR) have greatly contributed to our understanding of cell signaling and transcriptional regulation. In addition to the classical ER and PR nuclear actions, new signaling pathways have recently been identified due to ER and PR association with cell membranes and signal transduction proteins. Bio-informatics has unveiled how ER and PR recognize their ligands, selective modulators and co-factors, which has helped to implement them as key targets in the treatment of benign and malignant tumors. Knowledge regarding ER and PR is vast and complex; therefore, this review will focus on their isoforms, signaling pathways, co-activators and co-repressors, which lead to target gene regulation. Moreover it will highlight ER and PR involvement in benign and malignant diseases as well as pharmacological substances influencing cell signaling and provide established and new structural insights into the mechanism of activation and inhibition of these receptors.

Keywords: Estrogen and progesterone receptors, SERMs and tamoxifen, Crystal structures, Breast and endometrial carcinoma

The nuclear receptor superfamily

Estrogen receptors and progesterone receptors are members of the nuclear receptor (NR) superfamily, which most likely arose from a common ancestor (Fig. 1a). This superfamily consists of 18 receptor members, which are divided into class I and class II NR (Fig. 1b). Class I NR include the steroid hormone receptors: estrogen receptor α and β (ERα/β), progesterone receptor A and B (PRA/B), glucocorticoid receptor (GR), mineralocorticoid receptor (MR), and the androgen receptor (AR). Class II NR represents the retinoic acid receptor (RARα/β/γ), retinoid X receptor (RXRα/β/γ), vitamin D receptor (VDR), peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPARα/γ/δ) and the thyroid receptor (TRα/β). All receptors of the NR superfamily are inducible transcription factors, which become active upon binding their cognate ligand.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of the nuclear receptor superfamily based on human protein sequences. a Schematic shows the 18 nuclear receptor (NR) members and common ancestor (CA). b Unrooted tree showing evolutionary distances between the members of the nuclear receptor superfamily. Distances in both trees correlate directly to evolutionary distances and inversely to sequence identity of the proteins analyzed, including estrogen receptor α and β (ERα/β), glucocorticoid (GR), mineralocorticoid (MR), progesterone (PR), androgen (AR), retinoic acid (RARα/β/γ), retinoid X (RXRα/β/γ), vitamin D (VDR), peroxisome proliferator activated (PPARα/γ/δ) and thyroid receptor (TRα/β). In addition to the 18 NR members several orphan receptors have been described, which are not represented in the schematics. One of these orphan receptor subgroups is called NR3B, where ERRα is most abundantly expressed, followed by ERRγ and then ERRβ. ERRs are also described as transcription factors, with the ERR isoforms binding to a number of co-regulator proteins also shared by other NRs [1]

Estrogen and progesterone receptors

17β-Estradiol (E2) is the main ligand binding to ERα/β (Fig. 2a). E2 is secreted into the bloodstream by the adrenal cortex and gonads and plays a prominent role in mediating sexual development and behavior, reproductive functions, proliferation and differentiation of various tissues via ER. For example, E2/ERα interaction is responsible for E2-induced proliferation of breast and uterine tissue. ERα was first isolated in 1962, the corresponding gene cloned in the same year [6] and subsequently located to the long arm of chromosome 6 (6q24–q27; today 6q25.1) [7]. Three decades later, in 1993, the first ERα knockout mouse was created and led to the discovery that development was possible without ERα [8]. At that time, ERα was thought to be the only receptor mediating responses to E2, but in 1996 ERβ was cloned [9] and located to chromosome 14 (14q23.2) [10]. In addition to the ERα single knock-out mouse the ERβ single and ERα/β double knock-out mice demonstrated severely impaired reproduction functions [11].

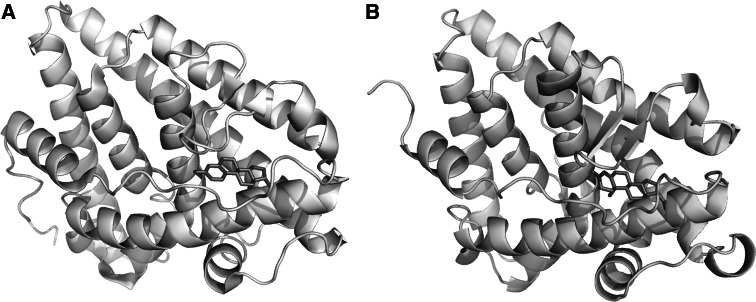

Fig. 2.

Molecular structures of ERα and PR bound to E2 and progesterone. Ligand Binding Domain of ERα (a) and PR (b) complexed to E2 and progesterone, respectively. Note that both proteins share a high degree of conservation concerning their three-dimensional structure. Images were based on the X-ray structures for a Gangloff et al. [2], available in the protein databank, access code pdb1qku and b Williams et al. [3], access code pdb1a28. Visualization was performed using STRAP [4] and PyMol [5]

E2 binds with a high affinity to ER, whereas metabolic products of E2, like estrone and estriol, bind with a lower affinity. Estrogenic action can be influenced pharmacologically by anti-estrogens and selective estrogen receptor modulators called SERMs. The first SERM clinically tested was tamoxifen in the 1970s and still today tamoxifen shows remarkable effects in the adjuvant therapy of ER positive breast cancer in pre- and postmenopausal women [12, 13], and for breast cancer in men [14]. Not only is tamoxifen used to prevent the original tumor from relapsing, but also helps to prevent cancer development in the contralateral breast. Presently, tamoxifen is also available in the United States for the reduction of breast cancer incidence in high-risk premenopausal and postmenopausal women [15], where a 50% decrease in the incidence of breast cancer was demonstrated. Despite the positive clinical outcome following treatment of breast cancer with tamoxifen, one negative risk factor includes the development of endometrial carcinoma due to tamoxifen’s pro-estrogenic effects in uterine tissue [16, 17]. In addition, tamoxifen was also found significantly associated with the occurrence of various benign pathological endometrial tissues, including hyperplasia and polyps, which have been proposed as stages in EnCa progression [16].

The physiological ligand for PR is progesterone (Fig. 2b), whose effects include differentiation of endometrium, control of implantation, maturation of mammary epithelium and modulation of GnRH pulsatility. PR was discovered in 1970 as a high affinity binding partner for progesterone with the corresponding gene locating to the long arm of chromosome 11 (11q22.1) [18]. Mice lacking a functional PR gene displayed pleiotropic reproductive abnormalities including the inability to ovulate, uterine dysplasia and inflammation, severely limited mammary gland development, and impaired thymic function and sexual behaviour [19]. In 1981, Philibert et al. [20] described a PR and GR antagonist, mifepristone (RU486), which was the first antagonist to be an effective abortifacient and postcoital contraceptive. In the following years, mifepristone has also been implemented in treatment of the most common smooth muscle benign uterine tumors, leiomyomas, occuring in 25% of women in the reproductive age and more rarely postmenopausal [21]. Leiomyoma size or location can cause severe clinical phenotypes resulting in abnormal uterine bleeding, pelvic pain or pressure and reproductive problems. Even though both ERα and PR represent the dominant protein species over expressed in leiomyomas compared to normal myometrium, targeting PR alone with mifepristone can inhibit and control tumor growth supporting a key role for PR in myoma etiology [22]. In endometriosis, another common benign gynecological disease affecting 10–15% of women in the reproductive age, both ER and PR have also been implicated in disease progression [21, 23]. The endometriotic lesion is described as a steroid hormone-dependent endometrium-like tissue consisting of glands and stroma, which mainly establishes growth outside the uterine cavity, especially the ovary and peritoneum. Although GnRH agonists and antagonists are frequently used to treat endometriosis patients, mifepristone treatment at low doses demonstrated a mean regression of the lesion after a 6 month treatment [24].

Estrogen and progesterone receptor protein structure

Steroid hormone receptors share a high level of sequence homology, conservation of three-dimensional structure and protein domains particularly regarding domains responsible for ligand binding, dimerization, DNA binding and transcriptional activation (Figs. 1a, 2, 3) [25].

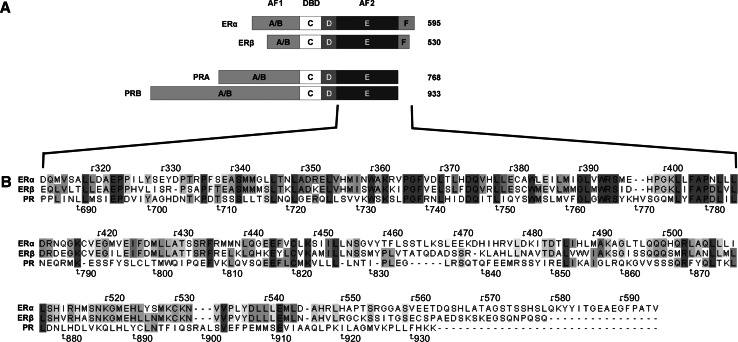

Fig. 3.

Steroid hormone receptor domains. a Steroid hormone receptors are composed of a variable N-terminal domain (A/B), an AF1 protein domain which is weakly conserved (<15%) among NR members and a highly conserved DNA-binding domain (DBD) or C-domain (96%), which in the case of ERα/β binds EREs (5′-AGGTCAnnnTGACCT-3′). The palindromic character of this sequence supports ER binding as a dimer. Steroid hormone receptors also have a flexible hinge region (D) and a C-terminal E-domain, containing the ligand-dependent AF2 region. ERα and ER β contain an additional F-domain at their carboxy-terminal ends. Numbers on the right represent the length of each receptor protein in amino acids. b ERα, ERβ and PR amino acid alignment of the AF2 domain demonstrating single or regions of amino acids in different shading patterns (dark grey amino acid identical in all three receptors, light grey identical amino acids in two receptors)

A/B-domain (amino acids 1–180)

The A/B domain, also called activation function 1 (AF1), resembles a domain responsible for protein-protein interactions and transactivation (Fig. 3). Most importantly, AF1 functions independently of ligands, in contrast to the C-terminal domain AF2, which is ligand-dependent. Concerning ERs, different splice variants of AF1 may modulate transcriptional activity by repressing AF1-mediated transactivation upon heterodimerization with full-length ER. Interestingly, in contrast to ERα, ERβ AF1 contains a repressor domain that decreases overall receptor transcriptional activity by masking transactivation of the amino terminal domain and only functions in the context of a full-length receptor [26]. There are two PR protein isoforms described, PRA and PRB (Fig. 3), where evidence supports that PRA can act as a trans-dominant inhibitor of PRB and even inhibit other members of the NR superfamily including ER, AR, MR and GR. The N-terminal 165 amino acids of PRB AF1, known as the B-upstream segment BUS or AF3, have been described to have activation function [27]. In addition, the PRB BUS domain can suppress PRB’s inhibitory domain and render PR antagonists (PA) ineffective [21]. This BUS domain may also influence receptor action on PA by exerting an effect on PRA and its inhibitory domain [21].

C-domain (amino acids 181–263)

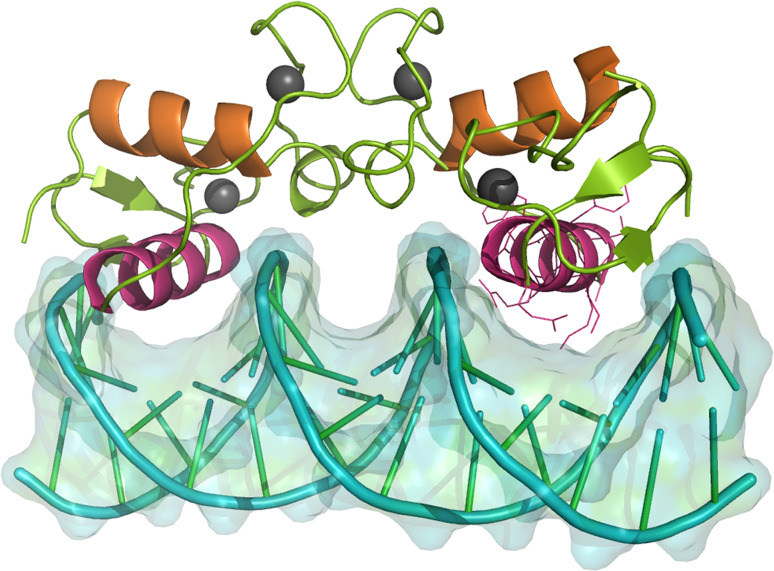

The C-domain of NR consists of a DNA-binding domain (DBD), which is highly homologous (Fig. 3). This domain features two zinc-finger motifs, which are not only responsible for DNA-binding, but also for the dimerization of the receptors, allowing the formation of homo- and heterodimers. In addition to these prominent zinc fingers, there are also two alpha-helical motifs within the DNA binding domain, where the first helix directly interacts with the DNA major groove, while the second helix stabilizes the complex (Fig. 4) [29]. ERα and ERβ dimers bind DNA with comparable affinities as either homo- or heterodimers to the same estrogen response elements (EREs) and regulate similar sets of genes [30]. PR and the remaining steroid receptors recognize a different DNA consensus sequence called progesterone response elements (PRE) [29].

Fig. 4.

DNA binding domain dimer of the human PR bound to its cognate DNA response element. The Zn2+-ions (depicted as grey spheres) maintain zinc finger shape. Helix 1 of the DBD is colored purple. These helices make up direct contacts with bases of the major groove at a PRE (5′-AGAAACAnnnTGTTTCT-3′) (see right helix 1 for amino acid residues contacting the DNA). Helix 2 (orange) overlays helix 1 and stabilizes the entire complex. The image was based on the X-ray structures by Roemer et al. [28], available in the protein databank, access code pdb2c7a. Visualization was performed using STRAP89 [4] and PyMol [5]

D-domain (amino acids 264–302)

The D-domain is also referred to as the Hinge-region and contains a serine residue (S305) that can be phosphorylated in ERs; however, the exact function of the hinge-region in PRs is not yet known.

E and F-domains (amino acids 303–552 and 553–595)

The carboxy terminal E domain (also called AF2) represents a ligand binding domain (LBD) and an interaction site for peptides named co-activators and co-repressors. The carboxy terminal F domain represents the last 45 amino acids in ERα and approximately the last 30 amino acids in ERβ where it possibly functions to internally restrain dimerization of ER, thus protecting against improper ligand activation [31, 32]. The AF2 ligand binding pocket of the ER binds a wide range of compounds, including estrogens, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, phthalates, pesticides and a class of estrogen-like substances termed xenoestrogens [33]. The ligand-binding cavities as well as the interaction site with co-activators are both formed by 12 α-helices [34]. Exposed protein AF2 interaction surfaces are especially important and mediated by helices 3–5 and 12. As discussed later, Helix 12 (H12) has the most prominent role in ER, exhibiting different orientations when bound to E2 or tamoxifen [35]. It has been reported that covering of the interaction site by H12 hindered interaction with co-activators, possibly explaining the antagonistic effects of tamoxifen in the breast [36]. However, this model fails to completely explain why tamoxifen features pro-estrogenic effects in uterine tissue. Furthermore, AF1 and AF2 are known to act synergistically in activating transcription, with the highest level obtained when AF1 is fully active and an agonist is bound to AF2. AF1 or AF2 can also exert independent effects on target gene transcription, depending on the cell type and promoter context. For example, AF2 function of the ER may not be required on all promoters. Instead, a second transcription factor could substitute for AF2 and activate transcription even with antagonists or modulators bound to AF2, as long as AF1 is active [37].

The structure of the PR AF2 ligand binding domain was first described in high resolution in 1998 [3]. In contrast to ER, the PR AF2 domain has ten α-helices, where helix 2 is absent, but helix 10 and 11 are condensed into a contiguous unit called H12 due to ER protein homology. To date, the PR AF2 domain has not yet been crystallized complexed to a co-activator, so it is difficult to describe the exact nature of the interaction. Nonetheless, structural comparisons between ER and PR suggest that H12 of PR also participates in the process of co-activator binding [38].

Estrogen and progesterone isoforms

With eight total ERα coding exons, up to five different ERα transcript isoform/variants have been noted in humans due to alternative usage of eight 5′ untranslated exons, exonic duplications, alternative splicing and intronic exons [39]. The length of human ERα correlates mainly with 595 amino acids, where in different cell lines protein variants derived from mRNA splice products have been confirmed, e.g. human ERα-36 (hERα-36 kDa), hERα-46 kDa and hERα-66 kDa [40, 41]. Interestingly, the hERα-36 lacks both transcriptional activation domains (AF1+2) and contains an exon coding for myristoylation sites, thus predicting an interaction with the plasma membrane [41]. The hERα-46 kDa also lacks AF1 and demonstrates an antagonizing activity on the proliferative action of the hERα-66 kDa species in MCF-7 cells [42]. The length of human ERβ comprising exons 1–7 has been revised several times based upon further upstream translational start codons and reports of new sequence information, altering the predicted length of the N-terminus. Like ERα, ERβ also displays several transcriptional isoforms/variants, including seven untranslated 5′ exons, alternative exonic splicing, and intronic exons [39].

Recent evidence suggests a regulatory role of ERβ on ERα transcriptional activity [43] and a misregulation of the ERα/β-ratio in the development of benign and malignant tumors, where tumor growth is driven by E2/ERα while ERβ functions as a tumor suppressor gene [44]. As demonstrated for normal mammary, ovary, prostate and colon tissues, ERβ is dominantly expressed over ERα, supporting that specific receptor ratios are important for normal growth control [44]. In contrast, a common event in breast, ovarian, prostate, colon and astrocytic tumors is a striking increase of ERα expression but a loss of ERβ [44, 45]. For example, progression of non-proliferative benign breast disease to proliferative benign breast disease demonstrated reduced ERβ protein levels [46]. Furthermore, decreasing ERβ levels have been considered as a marker for malignant progression and associated with a poorer prognosis in breast neoplasia [47] and a subgroup of ovarian granulosa cell tumors [48]. In addition, increased ER levels along with loss of ERβ expression were noted in a small cohort of endometrial stromal sarcomas [49]. In premenopausal leiomyomas compared to matched normal myometrium expression levels of ERα presided over ERβ [50].

On the other hand, ERβ over expression was commonly found in ovarian granulosa cell tumors and in 45.8% of non-small cell lung cancers [51–54]. Kovacs et al. [55] demonstrated that ERβ protein levels increased compared to normal myometrium in postmenopausal myomas. Furthermore, ERβ gene expression levels were significantly higher compared to ERα levels, thus supporting that ERβ up-regulation occurred at the transcriptional level [56]. In our most recent study comparing endometrial carcinoma to both endometrial control tissues and benign pathological endometrial tissues (hyperplasias, polyps) both ERα and ERβ expression levels were significantly increased along with a higher ERα/ERβ ratio ([57] and unpublished results). Furthermore, over expressed ERβ levels were also found in benign endometrial tissue progression to EnCa from breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen [57]. Finally, PR over expression also occurred in early endometrial benign tissue stages as well as EnCa [57]. All of the above findings support that a deregulation of ERα and ERβ ratios is a common event found in tumors, supporting the importance of ratios not only in benign disease progression to a malignant state but also in tumor maintenance.

The human PR gene comprises eight exons, where alternate transcriptional start sites in the promoter and introns, exonic splicing and ‘intronic’ exon insertions have resulted in four different isoforms [39]. For example, the isoforms PRA and PRB are differentially controlled by independent transcriptional start sites within the same gene promoter and also by independent translational start sites. In addition to both PRA/B transcriptional start sites, a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) called PR+331G/A creates a new TATA element, which results in additional PRB transcription [58]. Using transiently transfected PR constructs, PRA expression leads mainly to gene repression, whereas PRB correlated with gene activation [59, 60]. A comparison of both isoforms showed that PRA was N-terminally truncated by 165 amino acid residues resulting in a protein size of 94 kDa compared to PRB with 116 kDa (Fig. 3) [61]. In addition, PRA is mostly located in the nucleus, whereas PRB distributes between the nucleus and cytoplasm [59]. PRA and PRB are co-expressed in many cell types where they appear to be synthesized in equal proportions. Like ERα/β, changes in PRA/B ratios have been implicated in both malignant and benign diseases where the PR+331G/A SNP has been genotypically analyzed in association with endometrial, breast and ovarian carcinoma, deep infiltrating endometriosis, leiomyoma and patients undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF) [58, 62–69]. For example, in most studies involving breast cancer patients no correlation with the +331G/A SNP and disease risk was found [65, 68]. In another study, De Vivo et al. found a significant association of endometrial carcinoma patients with the +331G/A SNP along with a greater body mass index (>28 kg/m2), fewer overall children and a family history of endometrial or colorectal cancer compared to a control cohort [58].

Selective knock-out models have proven that PR isoforms play different roles regarding the target tissue [70]. In PRA knock-out mice, the remaining PRB isoform functions in a tissue-specific manner to mediate a subset of the reproductive functions of PRs. In these mice, PRA ablation does not affect responses of the mammary gland or thymus to progesterone, but results in severe abnormalities in ovarian and uterine function and infertility. PRB knock-out mice have no effect regarding ovarian, uterine, or thymic responses to progesterone but rather exhibit reduced mammary ductal morphogenesis. Thus, both isoforms mediate their progesterone-dependent responses through activation of different subsets of genes where PRA is both necessary and sufficient for reproductive fertility functions, while PRB has more of a role in mammary development [71].

Furthermore, both PR and ER isoforms exhibit repressive function on the other. As ERβ effectively dimerizes with ERα, and the mixed dimer shows an identical subnuclear distribution as the homodimer, mouse knock-outs of either receptor showed completely opposing phenotypes due to the repressive function of ERβ [72]. Regarding PR, PRB is the transcriptionally most active isoform, which can be repressed by PRA. With reporter constructs containing a single palindromic PRE, PRA displayed similar transactivation activity to PRB. However, when more complex response elements such as the mouse mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat and PRE2TATAtk constructs were used, PRA acted as a transdominant inhibitor of PRB [73].

Co-activators and Co-repressors

The binding of agonistic ligands and/or phosphorylations within the ER, PR AF1 domains are the first steps for activating target gene transcription. However, the process of transcriptional activation or repression also depends on additional proteins named co-activators and co-repressors that modify the chromatin state and recruit or hinder the basal transcriptional machinery. The co-activators and co-repressors discussed here provide a short overview over a rapidly emerging field (Table 1).

Table 1.

Nuclear co-activators and co-repressors. In the literature, more than 300 co-regulators have been described [74], which led to the differentiation between the so-called primary cofactors that directly interact with nuclear receptors, and secondary cofactors that lack direct contact to a nuclear receptor, but modulate the actions of primary cofactors in a complex

| Type | Name | Other names | Interacting transcription factors | Initial description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-activator | SRC-1 | NCoA1 | ER, PR, GR, RXR, PPAR, TR | Oñate et al. [187] |

| SRC-2 | GRIP1, TIF2, NCoA2 | ER, GR, RXR | Voegel et al. [188] | |

| SRC-3 | RAC3, p/CIP, ACTR, AIB1, TRAM1, NCoA3 | ER, RXR, TR | Discovered independently by different groups, reviewed by Leo and Chen [189] | |

| PELP1 | MNAR | ERα/β, PR, GR, AR, RXRα, STAT3, and as co-repressor on NFκB, AP-1, TCF/SRF | Vadlamudi et al. [85] | |

| SRA/SRAP | ERα/β, PR, GR, AR, RAR, VDR, PPARδ, TRα/β, | Lanz et al. [190] | ||

| E6-AP | ER, PR, GR, AR | Nawaz et al. [191] | ||

| L7/SPA | ER, PR | Jackson et al. [192] | ||

| PIAS | ER, PR, GR, AR | Kotaja et al. [193] | ||

| DRIP205 | PPARBP, TRAP220, TRIP2 | ER, RAR, VDR, TR | Rachez et al. [88] | |

| Co-repressor | NCoR1 | ER, PR, RXR, PPAR, TR | Hörlein et al. [194] | |

| NCoR2 | SMRT | ER, PR, RXR, PPAR, TR | Chen and Evans [195] |

SRC-1 was the first co-activator identified and has been shown to interact with different nuclear receptors [76] Two splice variants of SRC-1 were identified with similar C- but different N-termini, providing differential regulation [77]. SRC-2, also termed glucocorticoid receptor-interacting protein 1 (GRIP1), transcriptional intermediary factor 2 (TIF2) or nuclear receptor co-activator 2 (NCoA2), binds to AF2 of specific nuclear receptors (Table 1). Although not considered a co-activator, the MUC1 oncoprotein not only bound directly to ERα at promoters, but also increased the recruitment of SRC-1 and SRC-2, thus enhancing ER mediated transcription following E2 stimulation of breast cancer cells [78].

The third member of this family SRC-3 was identified and described as retinoic acid receptor interacting protein (RAC3), mouse homolog CBP-interacting protein (p/CIP), hRARβ-stimulatory protein (ACTR), amplified in breast cancer (AIB1) and TR-interacting protein (TRAM1) (Table 1). p/CIP and the human isoform (RAC3/ACTR/AIB1/TRAM1) are involved in cellular proliferation, differentiation, migration and up-regulated in breast cancer [79, 80]. The demonstration of an interaction of SRC family members (also called the p160 family) with the CREB binding protein (CBP) and its homolog p300 has provided further insight into the molecular mechanisms [81]. Importantly, the co-activators exert their actions in at least two ways: on the one hand interacting with components of the transcriptional machinery (TBP, TFIIB and RNA polymerase II) [76] and on the other hand recruiting p300/CBP, which possesses both intrinsic and associated histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activities [82], thus promoting transcription by opening the chromatin structure. All members of the SRC family feature a common motif that is termed NR box [83, 84] and is defined by a conserved motif, LXXLL, where L is Leucine and X is any amino acid. Three to four motifs are present in every member of the SRC family, and site-directed mutagenesis experiments proved that this motif is required for efficient binding to liganded nuclear receptors via AF2.

In 2001, a novel co-activator PELP1 (proline, glutamic acid and leucine-rich protein) was identified that is not related to the three members of the SRC family [85]. PELP1 also interacts with CBP and p300 to enhance transcription, and additionally affects cell cycle progression, as it associates with pRb, leading to persistent hyperphosphorylation in an E2 dependent manner [86]. This suggests that PELP1 contributes to E2 mediated cell cycle progression. PELP1 was also described to be involved in histone modification, especially in the displacement of H1 [87]. Another class of co-activators called vitamin D receptor protein (DRIP), ARC or TRAP comprises of a multiprotein complex interacting with ligand bound nuclear receptors like ERα or ERβ via the DRIP205/TRAP220/PPARBP subunit [88].

Evidence supports that antagonist-mediated inhibition of ERα not only blocks co-activator recruitment but also facilitates the recruitment of a variety of co-repressors to ERα [75, 89–91]. The nuclear receptor co-repressor (NCoR1) and silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid receptor (SMRT or NCoR2) are found in complexes with histone-deacetylases supporting their role in chromatin modification into a transcriptionally less active state [92]. Interestingly, ER does not interact with co-repressors in the absence of a ligand, but only interacts when antagonists or modulators of estrogenic action (e.g. tamoxifen) are bound [93].

Estrogen and progesterone receptor signaling

The most well-characterized steroid hormone receptor signaling occurs via a cellular genomic response where lipophilic ligands diffuse through the cellular membrane, bind to ER or PR, induce a conformational change and release heat shock proteins (hsp) (Fig. 5) [94, 95]. Upon unveiling a nuclear localization signal (NLS), ligand bound receptor dimers translocate to the nucleus and along with a variety of cofactors result in transcriptional regulation of target genes. In addition to freely diffusing steroids, Hammes et al. demonstrated that megalin, an endocytic receptor in reproductive tissues, may provide an active transport mechanism for cellular uptake of biologically active androgens and estrogens [98]. Also mediated by ligand binding and even independent of ligands, activation of membrane associated steroid hormone receptors can signal via a rapid cellular but non-genomic response occurring in seconds or minutes where activation of signal transduction pathways or second messenger signaling results in target gene activation [35].

Fig. 5.

Model of ER-signaling: the main ER-signaling in cells occurs via a genomic response after binding of steroid hormones (like E2) or analogues. Following ligand binding and release from the chaperones heat shock proteins (hsp) 70 and/or hsp90 [94, 95], ER dimers (middle grey striped oval circle) translocate to the nucleus where they regulate target genes, which ultimately results in specific cellular outcomes. In addition, dependent or independent of ligands, membrane associated ER can signal via a rapid response leading to cellular fates [96]. ER membrane association can occur following different membrane receptor activations, like IGF-1R, EGFR or Her2 via PI3-K (p85 and p110) (grey stick receptor) and lead to further signal transduction of AKT or with Shc via MAPK pathway. In addition, palmitoylated ER was also found at specific membrane domains, called caveolae (far right) associated with caveolin 1 (Cav 1), which inhibits adenylcyclase (AC) via Gαi and results in ER dissociation from the membrane after ligand binding through de-palmitoylation [97]. Black diamond E2, cross palmitoylation, P phosphorylation, IRS Insulin receptor substrate, PM plasma membrane

Non-genomic estrogen signaling

The model of non-genomic responses arose from studies demonstrating that E2 repeatedly exerted effects that were too fast to be based on transcriptional events. The ER membrane form is predicted as a full-length ER [99], an isoform [41, 100] or a completely distinct receptor [101]. ERs harbor neither transmembrane nor intrinsic kinase domains, which could explain membranous signaling events, thus specific modifications like myristoylation, palmitoylation and protein interactions are most likely involved to target and maintain ER at the plasma membrane. The adaptor protein Shc and the Insulin-like growth factor I receptor (IGF-IR) were shown to be necessary for membrane localization of ER by siRNA knock-down assays [102]. Additionally, ER was shown targeted to lipid rafts within the plasma membrane by interaction with caveolin-1 [103] and palmitoylation occurring on a specific cysteine (C447) ER residue (Fig. 5) [104]. Not only steroid hormone receptors bind E2 and mediate cell signaling. For example, E2 bound transmembrane G-protein-coupled receptor GPR30 activated p44/42 MAPK through transactivation of EGFR [105, 106]. In addition, GPR30 also bound tamoxifen, ICI 182,780 and genistein, but not progesterone [107]. Importantly, non-genomic E2 mediated GPR30 signaling occurred in ovarian, endometrial and breast cancer cells and specifically correlated with ER expression, Her2/neu over expression, tumor size, and metastasis in breast cancer [105, 107]. Therefore, other proteins than steroid hormone receptors have to be considered for E2 and SERM signaling, despite ER expression.

Activation of ER by phosphorylation was demonstrated in a hormone-dependent as well as hormone-independent manner and is an integral regulatory mechanism of non-genomic responses (Fig. 5). Previously it was thought that a transcriptionally active ER was solely dependent on an agonistic ligand; however, newer studies demonstrated that extensive phosphorylation led to a pool of ER molecules that were transcriptionally active even in the absence of E2. For example, E2 but not progesterone treatment of MCF-7 breast cancer cells increased ER phosphorylation fourfold within the first hour of treatment [108]. Phosphorylation of the ER serine residue118 (ER-S118), induced by E2, was shown to occur independently of p44/42 MAPK in MCF-7 cells, whereas in the absence of E2, ER-S118 was phosphorylated in response to EGF and the phorbol ester PMA, which are known inducers of the p44/42 MAPK pathway [109]. This non-E2 mediated ER-S118 phosphorylation led to a transcriptionally active ER via the N-terminal AF1 but not the C-terminal AF2 domain. Interestingly, ER-S118 is located within the sequence PPQLSPFLQ, which has a high degree of homology with the optimal peptide substrate identified for p44 MAPK [110]. But importantly, non-E2 mediated ER phosphorylation could be blocked separately while leaving the E2-mediated induction unaffected. This result further supports that a kinase other than p44/42 MAPK must be involved in E2-induced ER-S118 phosphorylation, which may be linked to the hormone-induced change in ER conformation [111]. Evidence supports that this E2-dependent phosphorylation could be mediated by cyclin-dependent kinase 7 (Cdk7) [112]. Interestingly, SRC-2 is also phosphorylated by p44/42 MAPK at S736 and was shown necessary for complete co-activator function and transcriptional activation [113].

In addition to MAPK mediated ER phosphorylation, other specific protein kinases phosphorylate ER at S104, S106 and S118. Mutant ERs featuring S104A, S106A and S118A were tested with reporter constructs and showed a 40% reduction in transcriptional activity, whereas one mutation alone reduced activity by approximately 15% [114]. ER-S167 was identified as another major E2-dependent phosphorylation site in MCF-7 cells, and as a substrate of casein kinase II in vitro [115, 116]. Interestingly, ER-S167 phosphorylation increased the ability of the ER to bind EREs. Martin et al. demonstrated for the first time the involvement of AKT, also called Protein Kinase B, in phosphorylation of ERα [117]. AKT becomes activated by growth factors binding to tyrosine-kinase receptors which signal via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K). Major regulatory proteins for AKT regulation in the signaling pathway are phosphatase with tensin homology (PTEN) and target of Rapamyicn (mTOR). PTEN is a lipid phosphatase specific for 3′phosphorylated inositol phosphates and inhibits AKT phosphorylation, whereas the mTOR kinase is essential for AKT phosphorylation [118]. Upon phosphorylation and activation AKT functions in two ways, on the one hand augments transcription of ERα, and on the other hand increases ER activity by phosphorylating AF1 on different residues, namely ER-S104, -S106, -S118 and -S167. Increased protein phosphorylation of both AKT and PTEN along with PTEN gene mutations, deletions or loss of expression have been detected in hormone responsive tumors, which would lead to an enhancement of ER signaling. For example, in prostate cancer, loss of heterozygosity at 10q23, the PTEN locus, has been associated with cancer progression in 30–60% of cases where increasing frequency correlated with tumor grade and stage [119]. Loss of PTEN is also frequently found in ovarian carcinomas, endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas [120], approximately 20% of endometrial hyperplasias, and in 50% of endometrial carcinomas [121]. We recently demonstrated in both benign and malignant endometrial tissues from breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen [57], that hyperphosphorylation of PTEN-S380, mTOR-S2448, AKT (AKT-T308, AKT-S473) and ERα (ERα-S118) was enhanced, supporting a regulatory role for tamoxifen in protein phosphorylation and a linkage between AKT and ER signaling. PTEN-S380 phosphorylation renders PTEN inactive, thus augmenting AKT phosphorylation and ER signaling. Following tamoxifen treatment of RL95-2, an endometrial carcinoma cell line, a 4.2 and twofold phosphorylation increase of AKT-T308 and ERα-S118, respectively, occurred within 10 min along with up-regulation of the envelope gene of the human endogenous retrovirus (HERV)-W, Syncytin-1 gene expression, a recently identified ER target gene [57, 122]. Taken together these findings point out the various ways ER signaling can be enhanced in tumor cells and demonstrate tamoxifen’s role in AKT activation, ERα phosphorylation and target gene expression in benign progression to endometrial carcinoma via a non-genomic response.

Protein Kinase A (PKA) is also involved in regulating ERα transcriptional activity by phosphorylation of ER-S236 in one zinc-finger of the DBD. This modification was found to inhibit dimerization and DNA-binding and had attenuating effects [123]. Cholera toxin, a G-protein activator, in combination with 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, and Dopamine have all been demonstrated to increase intracellular cAMP levels and activate PKA. Treatment of primary uterine cells in culture with these pharmacological agents resulted in an increase of ER-reporter genes [124]. Transient transfection studies indicated that cAMP activation of ERα required neither ER-S118 phosphorylation nor the receptor’s A/B domain [125]. The involvement of PKA in ER phosphorylation remains controversial and cannot explain the enhancement of transcription by itself. While some researchers claim that a contribution could also be due to phosphorylation of SRC-1 by PKA on the amino acid residues T1179 and S1185 [126], others state that the co-activator SRC-1 cannot be phosphorylated directly by PKA [127]. Recent evidence suggests that phosphorylation of ER-S305, within the D-Domain of ERα, leads to an altered orientation between ER and its co-activator SRC-1. This phosphorylation is mediated by PKA and renders the transcription complex active in the presence of tamoxifen [128], resulting in tamoxifen resistance [129].

Nonetheless, the discussion of potential kinase candidates to phosphorylate ER remains controversial. What has been described above follows a consensus, but in contrast to the above, Arnold et al. [115] support a specific involvement of only DNA-PK, MAPK and CK-II in ER phosphorylation.

Non-genomic progesterone signaling

Like ER, PR non-genomic responses have also been described, especially in breast cancer cells. To date, three major models exist to describe PR at the membrane. Based upon cDNA homologies, mRNA cellular injection experiments and antibodies using Xenopus oocytes and breast cancer cells support a membrane PR isoform [130–132]. Similar to ERα, the membrane localization of PRs in human breast cancer cells support palmitoylation, where a distinct palmitoylation motif was identified within the ligand binding domain of PR [133]. In addition, a specific polyproline motif in the PR N-terminus was identified and mediated direct interaction of the receptor with SH3 domains of various cytoplasmic signaling molecules, including c-Src tyrosine kinases. Activation of c-Src and the downstream MAPK in mammalian cells was shown to be dependent on PR-SH3 domain interaction, but not on the transcriptional activity of PR [134]. In human breast cancer cells progesterone induction demonstrated that upregulation of selected target genes including Cyclin D1 and entry into S phase was dependent on MAPK [132]. Using mutant PRs confirmed that the above breast cancer proliferative response due to progesterone receptor agonists, called progestins, stemmed from PR activation of p44/42 MAPKs. Thus, progesterone receptor non-genomic responses are important in breast cancer signaling. Other examples of PR interactions with signaling molecules include PI3K, where both proteins were co-precipitated with PI3K in its active form. The PI3K inhibitor wortmannin resulted in delaying the progesterone-induced response, indicating that the association of PR with PI3K was functionally important [135].

Using cDNA libraries and antibodies, Zhu et al. identified a hormonally regulated membrane PR called mPR in spotted seatrout ovaries that featured a 7-transmembrane structure, with similarities to G-protein coupled receptors [136]. To date, three mPRs are known, mPRα, mPRβ and mPRγ, which have been grouped into a unique receptor class called the progestin and adiponectin receptor (PAQR) family. Both mPRα and mPRβ share a high level of homology (sequence identity 49%) across a broad range of species [137]. The mPRγ is more divergent and features less sequence homology (about 30%) to mPRα and mPRβ. All mPR subtypes were found expressed in human MCF-7 and SK-BR-3 breast cancer cells as well as primary tissues, where mPRα gene expression was higher in breast tumors compared with patient matched normal breast tissue [138].

Cross talk between the mPRs and signal transduction pathways is also prevalent. For example, both mPRα and mPRβ were found coupled to the inhibitory Gi protein in myometrial cells where upon activation an inhibition of adenyl cyclase, a subsequent reduction of cAMP levels and an increased phosphorylation of myosin light chain occurred, which resulted in myometrial contraction. Furthermore, activation of mPRs led to increased phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, but not p44/42 MAPK. Moreover, PRB nuclear transactivation occurred, thus representing the first evidence for cross-talk between membrane and nuclear PRs [139]. In MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells transfected with either mPRα or mPRβ and treated with the progesterone agonist 4-pregnen-17,20β-diol-3-one (17,20β-DHP), a significant activation of MAPK was found, thus demonstrating direct signal transduction via mPRs [140]. Concerning mPRγ, Nutu et al. [141] suggested a common role of this receptor in the regulation of ciliary activity during gamete transport in mammals as well as demonstrated its expression outside the reproductive tract of mice, e.g. in lung and liver.

Transcription of target genes

There is a wealth of knowledge concerning target genes of ER and PR [142]. Besides ER binding directly to EREs, another mechanism for target gene regulation is the ‘tethering’ mechanism, where ER does not contact DNA but recruits the transcriptional machinery by interacting with e.g. SP1 at promoter Sp1-sites. Using deletion mutants and chimeric receptors, Saville et al. [143] proved that interaction with SP1 is dependent on amino acids 79–117 of the ERα AF1 domain, whereas in contrast, ERβ AF1 did not evoke a comparable transactivational response. Examples of target genes via the tethering mechanism of activation include c-fos, cathepsin D, retinoic acid receptor 1α (RAR1α), adenosine desaminase, E2F1, bcl-2, the Insulin-like growth factor binding protein (IGFBP-4) and possibly the newly identified paired box gene 2 (PAX2) [143, 144].

In the case of ER target gene transactivation occurring at AP-1 binding sites, ER interacts directly with a Jun/Fos heterodimer. Target genes regulated via ER-AP-1 sites include ovalbumin [145] and IGF-I [146]. Though the isolated LBD together with AF2 is a strong estrogen-dependent activator of AP-1 target genes, this activation also requires AF1, since mutations in AF1 severely compromise estrogen activation of AP-1 [147]. In contrast, Kushner et al. [147] proved that an ERα lacking AF1 was a potent activator of AP-1 target genes in the presence of SERMs. The observation that ERβ which lacks an active AF1 function is also able to induce a comparable response in the presence of SERMs led to the theory that AP-1 mediated responses in the presence of E2 are AF1 and AF2 dependent. However, they occurred independently of both AF1 and AF2 when SERMs were liganded to the ER. Moreover, with raloxifene ERβ was tenfold more efficient in activating AP-1 targets than ERα with E2 [148], which demonstrated that certain subsets of target genes are differently regulated by distinct ligands and the present isoforms of the receptor.

SERMS and anti-estrogens

Breast cancer is not only the most common cancer among women with more than 180,000 new cases reported in the United States in 2008, but also the leading cause of cancer deaths, accounting for 40,000 deaths in the United States 2008, and approximately 502,000 deaths per year worldwide [149, 150]. Although rare, the breast cancer incidence for men in the United States in 2008 was 1,990 with estimated deaths at 450 [149]. Tamoxifen is by far the most well studied SERM, which has been implemented world wide for breast cancer treatment (Table 2). The association between a higher risk for developing endometrial cancer and tamoxifen treatment was discovered during the 1980s and confirmed in the following years. For example, the ALERT study in 2000 reported a 6.9-fold increase of endometrial cancer incidence with a 5-year tamoxifen treatment [152]. Many studies throughout the years have confirmed a clear association of tamoxifen use and an increase of benign endometrial growth. In one larger study involving 700 breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen, benign endometrial changes were observed in 38.85%, including 23.14% polyps, 8% hyperplasia, 3% metaplasia and 4.71% endometrial carcinoma [16, 17]. Importantly, many ERα gene targets have been identified by us and others as key genes induced by E2 and/or tamoxifen, which promoted growth of endometrial carcinoma cells [57, 122, 144]. Some recent examples include the IGF1, PAX2 and Syncytin-1 genes where over expression occurred in a stepwise manner in prior pathological endometrial stages to EnCa [57, 122, 144].

Table 2.

SERMS and progestins. SERMs belong to four structural classifications: triphenlyethylenes, benzothiophenes, benzopyrans, and naphthalenes

| SERM | Brand name | Formula, class | Clinical target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clomiphene | Clomid® | C26H28ClNO chloroethylene | Infertility |

| Tamoxifen | Novaldex® | C26H29NO triphenylethylene | Metastatic breast cancer |

| Toremifene | Fareston® | C26H28ClNO triphenylethylene | Breast cancer |

| Ospemifene | Ophena® | C24H23ClO2 triphenylethylene | Vaginal atrophy |

| Raloxifene | Evista® | C28H27NO4S benzothiophene | Osteoporosis, breast cancer |

| Lasofoxifene | Fablyn® | C28H31NO2 naphtalene | Osteoporosis, vaginal atrophy |

| Fulvestrant (ICI 182,780) | Faslodex® | C32H47F5O3S steroidal | Breast cancer |

| Bazedoxifene | Viviant® | C30H34N2O3 indole | Osteoporosis |

| Arzoxifene (LY353381) | C28H29NO4S benzothiophene | Endometrial and breast cancer | |

| Acolbifene (EM-652 + prodrug EM-800) | C29H31NO4 benzpyran | Breast and endometrial cancer | |

| Pipendoxifene (ERA-923) | C29H32N2O3 indole | Metastatic breast cancer | |

| Progestins | |||

| Norgestimate | Ortho Cyclen-21® | C23H31NO3 phenanthren | Contraceptive, menopause |

| Norgestrel | Alesse® | C21H28O2 phenanthren | Contraceptive, endometriosis |

| Drospirenone | Yasmin® (with ethinylestradiol) | C24H30O 3 | Contraceptive, menopause |

| Progesterone antagonist | |||

| Mifepristone, RU38486 | Mifegyne® | C29H35NO2 phenanthren | Emergency contraceptive, hypercortisolism |

| Onapristone, ZK98299 | C29H39NO3 phenanthren | Contraceptive | |

| SPRM | |||

| Asoprisnil | C28H35NO4 phenanthren | Uterine fibroids | |

Tamoxifen, a triphenylethylene, is the prototypical first generation SERM. Other benzothiophene SERMs include raloxifene analogs such as LY117018 (6-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl) benzothiophene), and arzoxifene (LY353381). Benzopyrans (levormeloxifene, acolbifene), and the naphthalenes (trioxifene and lasofoxifene) have also been recently formulated. Individual columns represent from top (selective estrogen receptor modulators or SERMS) to bottom (progestins or [PR agonists], progesterone antagonist [PAs] and selective progesterone receptor modulators or SPRM) and left to right: brand name, formula, class, clinical target [151]. For more chemical information go to Pubchem substance (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez)

Raloxifene is a second-generation SERM that was admitted in clinical trials for prevention of osteoporosis in 1997 and was found to function similarly to tamoxifen in breast tumors but was also anti-estrogenic in endometrium (Table 2) [153–155]. Moreover, raloxifene lowers low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol without elevating triglycerides [156]. In 2007, the United States Food and Drug Administration approved raloxifene for reducing the risk of invasive breast cancer in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis and in postmenopausal women at high risk for invasive breast cancer [157]. In addition to raloxifene, several other SERMs like arzoxifene and EM-652 are under current investigation to determine their potential in treating breast cancer while leaving the endometrium unaffected [158] (Table 2). In the United States, the most common malignancy in men is prostate cancer with an incidence of 186,320 and the second leading cause for deaths [149]. Due to the importance of E2/ER signaling in prostate cancer and the acquired tumor resistance to androgen therapies in disease progression, SERMS have been tested. For example, in androgen resistant prostate cell lines, raloxifene induced apoptosis and inhibited growth [159]. Using human prostate xenograft-rat models, interestingly, raloxifene treatment significantly inhibited tumor growth but not regression [160]. Although phase II clinical trials have been performed with raloxifene treatment of prostate cancer patients with androgen-resistant tumors, and test results appeared to stabilize disease progression, more studies need to be performed on larger patient groups [160].

Fulvestrant or ICI 182,780 (Faslodex®), and the related compound ICI 164,384 are considered as “pure” anti-estrogens without any agonistic activities. These compounds compete with E2 for binding to the ER, inhibit both AF1 and AF2, prevent ER dimerization and impede its nuclear localization [161]. They also down regulate ER by reducing the half-life of the protein and increasing its turnover [162]. Nonetheless, by completely inactivating ER, ICI 182,780 and ICI 164,384 not only abolish E2 mediated proliferative stimuli, but also bone protection and furthermore promote menopause-like symptoms.

As a natural substance from soy beans, genistein, a phytoestrogen, is a bioflavonoid compound that has a ninefold higher affinity for ERβ than ERα and has been considered an alternative to conventional hormone replacement therapy [163]. It has been hypothesized that genistein exerts its estrogenic activity through its higher affinity to ERβ whereas synthetic and natural E2 have the same affinity to both ERα and ERβ. The molecular mechanism for this ERβ selectivity, however, is not yet fully understood, but leads to a lower incidence of menopausal symptoms, osteoporosis cardiovascular disease and possibly breast and EnCa [164].

SPRMS and progesterone antagonists

Several compounds targeting PR have been synthesized and used clinically, exhibiting a biological range from progestins to selective PR modulators called SPRMs, pure PR antagonists (PA), or even compounds with mixed agonist–antagonist activity. Currently, all drugs sharing the suffix “pristone” are regarded as PR antagonists (e.g., mifepristone, onapristone) whereas substances with the suffix “isnil” are selective progesterone receptor modulators or SPRMs (e.g. asoprisnil) (Table 2).

It was found that a combination treatment using different PR antagonists or PR modulators along with different SERMs or anti-estrogens (tamoxifen, droloxifen, ICI 164,384), showed greater anti-tumor efficacy than treatment with each drug alone as tested in animal models [165]. These studies were based in part on the following findings in breast ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and in invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC): (1) a decreased expression of PRA was shown compared to PRB [166] and, (2) a significant positive correlation using immunohistochemistry scores existed between PRA and ERα in IDC and DCIS but not for PRB and ERα [166]. Thus, PRA/PRB ratios and the relationship with ERs within a breast lesion are likely to be important as effectors of tumor growth and possibly markers for therapy.

Following the initial development of mifepristone for its abortive role in contraception, as discussed previously, mifepristone also has preventative contraceptive potential. At low doses, mifepristone blocked the LH surge, preventing implantation into endometrium. At higher doses during early luteal phase mifepristone was highly effective in preventing pregnancy with minimal disturbance of hormonal parameters or the menstrual cycle, whereas in mid and late luteal phases doses above 25 mg were effective in inducing endometrial cell shedding and bleeding [167].

Regarding treatment of uterine leiomyomas the efficacy of mifepristone is probably due to the growth stimulating function of progesterone [168]. Earlier studies demonstrated progestins combined with gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) analoga treatment did not result in tumor reduction [169–171]. Estrogen plus progestin treatment also resulted in increased uterine leiomyoma proliferation [171, 172]. However, in contrast, a significant shrinkage of approximately 50% leiomyoma tumor size was noted during treatment with mifepristone, further supporting a role for progesterone in leiomyoma growth and tumor maintenance [22]. Besides mifepristone treatment of endometriosis lesions [24], a comparative study between PA like onapristone and ZK 136 799 was also implemented and exhibited antiproliferative effects in ectopic but not eutopic endometrium via mechanisms, which remain to be established [173]. Nonetheless, PAs and SPRMs exhibit anti-proliferative effects in the uterus, rendering them useful especially in treating uterine leiomyoma and endometriosis.

Steroid hormone receptors, their natural ligands and synthetic modulators: a structural analysis

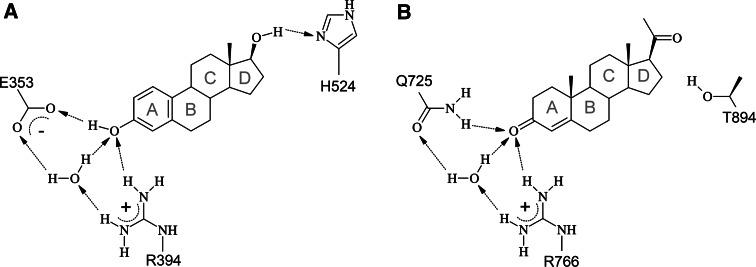

E2 and progesterone exhibit similar structural properties, raising the question how these two ligands are specifically recognized by their target receptors. Structural comparison of E2-bound ER [2, 38] and progesterone-bound PR [3] reveals that several hydrogen bonds differ between both complexes (Fig. 6). A key role for the discrimination between the two ligands can be attributed to E353 of ER, which interacts with the hydrogen atom of the ring A hydroxyl group of E2 (Fig. 6a). A second specific hydrogen bond is present between the 17-hydroxyl of E2 and the Nδ-atom of H524. These interactions described above cannot be formed by the keto-group present in progesterone, thus explaining the binding preference of ER for E2. Binding specificity of PR for progesterone is mainly due to Q725 of PR, which is present at the same spatial position as E353 in ER (Figs. 3, 6). The sidechain amide group of Q725 forms a hydrogen bond to the 3-keto position of the A ring of progesterone. For the 20-keto position there was no tight hydrogen bond observed in the crystal structure [38]. The hydroxyl group of T894, however, is located at a distance of 2.8 Å and possibly forms at least weak polar interactions that additionally contribute to PR binding specificity. In addition to the polar contacts, both ligands form a number of hydrophobic interactions, which rather contribute to binding affinity than to binding specificity. Interestingly, the ER ligand binding cavity is nearly twice the volume of its cognate ligand [174], allowing other substances to bind which have additional moieties that occupy these regions [34]. The binding of E2 and progesterone also has structural consequences for the receptors. Most prominently, H12 of the AF2 region positions itself across the entrance of the ligand binding pocket. In this so-called “agonist conformation” H12 also constitutes a key part of the co-activator binding interface, thus coupling agonist binding to subsequent activation processes.

Fig. 6.

Amino acids determining ligand binding specificity of ER for E2 (a) and of PR for progesterone (b). The ligands are shown as schematic presentation and the rings are labelled with grey letters. Amino acids of the receptor and water molecules that form polar interactions with the ligand are indicated and hydrogen bonds are shown as dotted arrows. See text for the details of the interactions. Figure prepared with MDL ISIS/Draw 2.5

Structural effects of antagonist binding to ER

Orally administered tamoxifen is rapidly converted by CYP2D6 to 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (4-OHT) to establish full potency. Due to this conversion, introduction of a hydroxyl group in ring A also renders the biophysical properties of tamoxifen more similar to those of the physiological ligand E2, which also contains a hydroxyl group in ring A (Fig. 6). As shown in Fig. 7a, b, superimposition of the three-dimensional complex structures reveals that E2 and 4-OHT occupy identical positions for their A-rings, competing for the same interactions within the binding pocket. Consequently, ring A of E2 and 4-OHT form highly similar interactions with ER, including three hydrogen bonds with E353, R394, and one water molecule (Fig. 6). The rest of the E2 molecule exhibits a nearly planar configuration due to its derivation from the common steroid structure that renders contortions impossible.

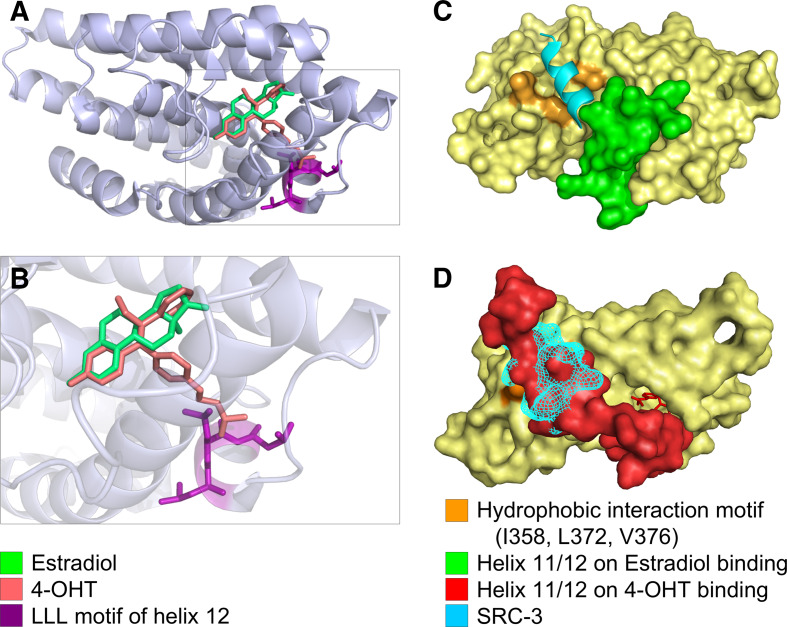

Fig. 7.

a E2 and 4-OHT bind to the ER ligand binding domain almost congruently. E2 (green) and 4-OHT (red) occupy similar positions within the ER ligand binding pocket. b Enlarged view of the binding pocket showing that the dimethyl-aminoethyl sidegroup of 4-OHT sticks out of the ligand binding pocket. The close proximity of the LLL motif in H12 to the polar side group of 4-OHT causes steric clashes and is energetically unfavorable. The agonistic orientation of H12 can, thus, not be maintained in the presence of 4-OHT. c E2 binding positions H12 (green) in an agonistic orientation that allows binding of co-activators (SRC-3 = cyan), whereas in d binding of 4-OHT repositions H12 towards the antagonistic orientation that overlaps with the co-activator binding site, leading to a competition between H12 and the co-activator molecule. Images were based on a 3D-superimposition of different X-ray structures [2, 34, 175]. Structures are available in the protein databank, access codes pdb1qku, pdb3ert, pdb1x7r. Visualization was performed using STRAP [4] and PyMol [5]

Although 4-OHT exhibits a phenolic A-ring like E2, the rest of the molecule is quite different. 4-OHT contains two additional aromatic rings, which are not condensed and thus exhibit a larger degree of conformational freedom. One of these rings can be accommodated within the binding pocket at a similar spatial position as ring D of E2 and forms numerous hydrophobic interactions with ER (Fig. 7a, b). The remaining aromatic ring, however, sticks out of the binding pocket between helices 3 and 11 and its dimethyl-aminoethyl sidegroup is oriented towards H12 of the LBD (Fig. 7a, b). As a result, the conformation observed for H12 in agonist-bound ER is no longer stable, resulting in a repositioning of H12. From a structural point of view, this displacement most likely can be attributed to steric clashes between the dimethyl-aminoethyl sidechain of 4-OHT and L540 of H12 (Fig. 7b). An additional destabilizing effect may arise from burying the polar dimethylamino group by the highly hydrophobic LLL motif (L539, L540, L541) of H12 [34]. Figure 7c displays the “agonist conformation” of H12 in green, which is switched to the “antagonist conformation” upon 4-OHT binding (Fig. 7d; in red).

ER interaction with co-activators

As evident from the complex crystal structure of ER with the steroid-receptor co-activator-3 (SRC-3) [175], the co-activator is bound in the immediate vicinity of H12 on the ER surface (Fig. 7c) and forms key contacts to the hydrophobic residues I358 (helix 3), L372 and V376 (helix 5) of ER. The importance of these amino acids for co-activator binding was also independently confirmed by site-directed mutagenesis proving that mutation of these residues resulted in down regulation of E2/ER mediated transcriptional activity [176]. In addition, residues L539, E542, and M543 of H12 in the agonist conformation also form direct contacts with the co-activator SRC-3. Thus, H12 in the “agonist conformation” (Fig. 7c) also constitutes a key part of the co-activator binding interface. The ER binding site also forms hydrophobic interactions with the co-activator highly conserved LXXLL motif within the NR-box [85, 177]. This NR-box motif is both necessary and sufficient to promote hydrophobic interactions of the co-activator with ER. Importantly, when E2 is bound to ER in an “agonistic configuration” involving the LBD and H12 (Fig. 7c), H12 does not overlap with the SRC-3 co-activator binding site. However, when 4-OHT binds to the LBD, H12 is repositioned and covers the key amino acids of helix 3 and 5 required for co-activator binding (Fig. 7d). Thus, in this “antagonist conformation” H12 competes with SRC-3 for identical interactions on the ER surface. This competition is further enhanced by the following mechanisms: First, H12 exhibits an LLEML motif that is quite similar to the LXXLL motif of the co-activators, which also forms an α-helix. Thus, H12 can directly interact with the hydrophobic surface in a highly similar fashion to that of co-activators (molecular mimicry). Second, as H12 is directly attached to the rest of the LBD, it will always be located in close proximity to the interaction site, whereas a co-activator in aqueous solution has to diffuse to its target and find its interaction partner.

The importance of H12 for ER activation is further emphasized by the fact that deletion or mutation of L540 within the LXXLL motif can abolish ER activity [178, 179], which may be due to the loss of specific binding of the SWI/SNF2 protein [180]. SWI/SNF2 is an ATP driven DNA helicase and a key protein in nucleosome remodeling. In this context, the effect of H12 rearrangement upon 4-OHT binding is twofold: First, SWI/SNF2 can no longer bind to H12, since the LLEML interaction motif is now blocked by intramolecular interactions. Second, SRC family members and PELP1 can no longer bind to their physiological interaction site on the ER surface, since this position is occupied by H12 in the “antagonist conformation”.

Earlier studies also demonstrated that LXXLL peptides can be used to inhibit estrogen-mediated activation in cells when co-expressed with either ERα or ERβ [181]. Due to prevention of co-activator recruitment to AF2, the binding sites of the receptors are occupied by the LXXLL peptides, thus supporting that co-activator recruitment depends on equilibrium of ligands competing for similar binding sites.

ER interactions with co-repressors

The binding of co-repressors is generally very complex and yet not fully understood [75, 91]. Co-repressors show a great variability in sequence and only a few of them, like NCoR1 and SMRT/NCoR2 exhibit NR box-related conserved bipartite interaction domains (NRID) [182] that contain sequences termed CoRNR box [183]. Heldring et al. [91] proposed to group co-repressors into four major classes: (1) class I co-repressors like NCoR1 and NCoR2/SMRT contain a classical CoRNR-box as described above; (2) class II co-repressors contain an LXXLL motif and are recruited in an estrogen-dependent manner acting as anti-co-activators; (3) class III co-repressors have less defined interaction mechanisms that differ from class I/II co-repressors; (4) class IV co-repressors have indirect effects and are possibly recruited via protein complexes.

H12 of ER was shown to contain an extended CoRNR box sequence that resembles the LXXXIXXXL consensus motif of NR co-repressors. Thus, H12 was able to occupy the co-repressor binding site and to prevent unwanted interactions, thereby providing a structural explanation for the poor ability of ER to directly interact with classical co-repressors [91]. This role of H12 was further substantiated from analysis of H12 deletion mutants (ERαΔH12), which showed a significantly enhanced binding of co-repressor peptides like NCoR1 and NCoR2/SMRT [184]. The problem of poor co-repressor binding is partially compensated by ligands which exhibit functional groups that can directly interact with the co-repressor. One example is the ER-raloxifene complex [184], in which the side chain of raloxifene is directly involved in co-repressor binding by contacting a Leucine residue of the co-repressor (Fig. 8a). With raloxifene bound to ER, co-repressor binding is facilitated, and several hydrophobic amino acid residues of a synthetic co-repressor peptide were shown to make direct contacts with L354, I358, K363, F367, L372, V376, E380, and W383 [184].

Fig. 8.

Raloxifene (a, red) and asoprisnil (b, red) both interact with co-repressor molecules (orange) via their side chains. All molecules are shown in the orientation when bound to the LBD of the cognate receptor (ER and PR, respectively). Peptide chains of the LBDs were omitted. a The terminal piperidine ring of the side chain of raloxifene comes in close proximity (3.7 Å) to a leucine residue of the co-repressor peptide, suggesting an interaction. b The terminal end of the asoprisnil side chain also comes into close proximity to a Leucine residue of the co-repressor molecule (4.1 Å and 3.2 Å) images were based on different X-ray structures (a [184]; b [185]). Structures are available in the protein databank, access codes pdb2jfa, pdb2ovh). Visualization was performed using STRAP [4] and PyMol [5]

PR interaction with co-repressors

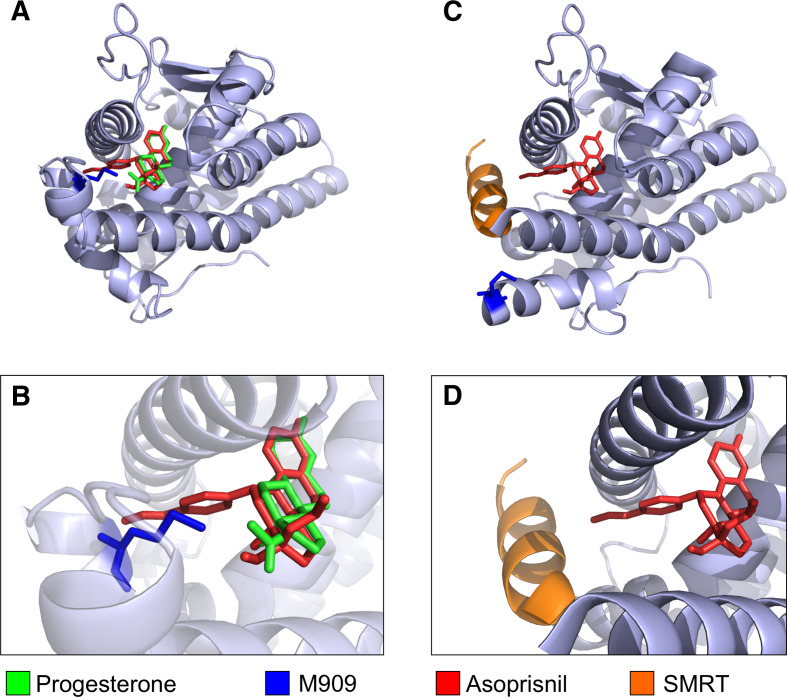

Like E2 and SERMs binding to ER, progesterone and the SPRM asoprisnil also bind to similar positions within the PR LBD (Fig. 9a, b). Asoprisnil induces conformational changes in PR mainly as a consequence of steric clashes between 11β-benzaldoxime group of asoprisnil and M909, which is located in H12 of PR (Fig. 9b). This mechanism for the displacement of H12 by asoprisnil is highly similar to that observed for 4-OHT upon ER binding (Fig. 7b), although the resulting position of H12 differs between both complexes.

Fig. 9.

a Progesterone (green) and asoprisnil (red) binding to the LBD of PR. b Enlarged view of the binding pocket. Asoprisnil exhibits a side chain that sticks out of the ligand binding pocket, colliding with M909 of PR (blue). These steric clashes lead to a change in the tertiary structure of PR and c allow access of co-repressor molecules. The bound SMRT fragment is depicted in orange. Note that M909 changed its position due to asoprisnil binding. d Enlarged view. Images were based on a 3D-superimposition of different X-ray structures [3, 185], available in the protein databank, access codes pdb1a28, pdb2ovh. Visualization was performed using STRAP [4] and PyMol [5]

In the asoprisnil complex, H12 was shown to adopt an alternative conformation [185] (Fig. 9c), allowing for the co-repressor peptide to come into close contact to the asoprisnil side chain (Figs. 8b, 9c, d). This H12 movement leads to two consequences: (1) it makes room for the longer co-repressor helix, and (2) it displaces E911, a residue observed to be critical for co-activator binding [185, 186]. Interestingly, the 11β-benzaldoxime group of asoprisnil is only 3.2 Å away from the interacting Leucine in the SMRT co-repressor molecule [185] (Fig. 8b), suggesting a direct interaction in analogy to the ER-raloxifene complex, where the raloxifene sidechain is 3.7 Å apart from the repressor molecule (Fig. 8a). In addition to the interaction with the asoprisnil side chain, the co-repressor peptide also forms specific polar interactions with residues of PR-740 on the loop between helix 3 and helix 4, K734 on helix 3, and E752 on helix 4, as well as hydrophobic interactions that stabilize co-repressor binding [185]. The SPRM mifepristone differs from asoprisnil in that a less polar dimethyl amine replaces the benzaldoxime substituent. This replacement allows for a potentially stronger hydrophobic interaction between mifepristone and the co-repressor that may account for increased co-repressor recruitment [185].

The fact that co-repressor molecules in contrast to co-activator molecules make direct contact to SERMs/SPRMs suggests the possibility that synthetic ligands can be designed to specifically influence cofactor binding. It must be noted that all analyses and calculations presented here refer to the isolated ligand binding domains of ER and PR. To date, it has not been possible to crystallize full-length ER or PR, impeding the prediction of interaction surfaces of dimerized receptor molecules. Moreover, structural information on cofactors is limited to their binding motifs. Fig. 7c, d for instance shows only a fragment of SRC-3 containing the NR-box, SRC-3 is actually a 160 KDa protein, with a 2.4-fold higher mass than ERα (66 kDa). The same is true for PR and the interacting molecules. Due to these limitations one has to keep in mind that the interactions presently known might reflect the situation only in parts, as residues of other protein domains might also be involved in modulating protein-protein interactions.

Acknowledgments

Our research was supported in part by the Interdisciplinary Centre for Clinical Research (IZKF) at the University Hospital of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg to P.L.S. and R.S. and from the Deutsche Krebshilfe to R.S. Thanks to Anselm Horn (Institute of Bioinformatics) for help with Fig. 6.

Contributor Information

Reiner Strick, Phone: +49-9131-8536671, FAX: +49-9131-8536670, Email: reiner.strick@uk-erlangen.de.

Pamela L. Strissel, Phone: +49-9131-8536671, FAX: +49-9131-8536670, Email: pamela.strissel@uk-erlangen.de

References

- 1.Tremblay AM, Giguere V. The NR3B subgroup: an overrview. Nucl Recept Signal. 2007;5:e009. doi: 10.1621/nrs.05009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gangloff M, Ruff M, Eiler S, Duclaud S, Wurtz JM, Moras D. Crystal structure of a mutant hERalpha ligand-binding domain reveals key structural features for the mechanism of partial agonism. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:15059–15065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009870200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams SP, Sigler PB. Atomic structure of progesterone complexed with its receptor. Nature. 1998;393:392–396. doi: 10.1038/30775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gille C, Frommel C. STRAP: editor for structural alignments of proteins. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:377–378. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.4.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. CA: Palo Alto; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greene GL, Gilna P, Waterfield M, Baker A, Hort Y, Shine J. Sequence and expression of human estrogen receptor complementary DNA. Science. 1986;231:1150–1154. doi: 10.1126/science.3753802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gosden JR, Middleton PG, Rout D. Localization of the human oestrogen receptor gene to chromosome 6q24–q27 by in situ hybridization. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1986;43:218–220. doi: 10.1159/000132325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lubahn DB, Moyer JS, Golding TS, Couse JF, Korach KS, Smithies O. Alteration of reproductive function but not prenatal sexual development after insertional disruption of the mouse estrogen receptor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11162–11166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuiper GG, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5925–5930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Grandien K, Lagercrantz S, Lagercrantz J, Fried G, Nordenskjold M, Gustafsson JA. Human estrogen receptor beta-gene structure, chromosomal localization, and expression pattern. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:4258–4265. doi: 10.1210/jc.82.12.4258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krege JH, Hodgin JB, Couse JF, Enmark E, Warner M, Mahler JF, Sar M, Korach KS, Gustafsson JA, Smithies O. Generation and reproductive phenotypes of mice lacking estrogen receptor beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15677–15682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ward HW. Anti-oestrogen therapy for breast cancer: a trial of tamoxifen at two dose levels. Br Med J. 1973;1:13–14. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5844.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riggs BL, Hartmann LC. Selective estrogen-receptor modulators–mechanisms of action and application to clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:618–629. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nordman IC, Dalley DN. Breast cancer in men: should aromatase inhibitors become first-line hormonal treatment? Breast J. 2008;14:562–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2008.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jordan VC. Chemoprevention of breast cancer with selective oestrogen-receptor modulators. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:46–53. doi: 10.1038/nrc2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flototto T, Djahansouzi S, Glaser M, Hanstein B, Niederacher D, Brumm C, Beckmann MW. Hormones and hormone antagonists: mechanisms of action in carcinogenesis of endometrial and breast cancer. Horm Metab Res. 2001;33:451–457. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-16936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deligdisch L, Kalir T, Cohen CJ, de Latour M, Le Bouedec G, Penault-Llorca F. Endometrial histopathology in 700 patients treated with tamoxifen for breast cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;78:181–186. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sherman MR, Corvol PL, O’Malley BW. Progesterone-binding components of chick oviduct I. Preliminary characterization of cytoplasmic components. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:6085–6096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Funk CR, Mani SK, Hughes AR, Montgomery CA, Jr, Shyamala G, Conneely OM, O’Malley BW. Mice lacking progesterone receptor exhibit pleiotropic reproductive abnormalities. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2266–2278. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.18.2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Philibert D, Deraedt R and Teutsch G (1981) RU 38486: a potent antiglucocorticoid in vivo. In: Proceedings of the VII International Congress of Pharmacology, Tokyo, Japan

- 21.Leonhardt SA, Boonyaratanakornkit V, Edwards DP. Progesterone receptor transcription and non-transcription signaling mechanisms. Steroids. 2003;68:761–770. doi: 10.1016/S0039-128X(03)00129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy AA, Kettel LM, Morales AJ, Roberts VJ, Yen SS. Regression of uterine leiomyomata in response to the antiprogesterone RU 486. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:513–517. doi: 10.1210/jc.76.2.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364:1789–1799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kettel LM, Murphy AA, Morales AJ, Yen SS. Preliminary report on the treatment of endometriosis with low-dose mifepristone (RU 486) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:1151–1156. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(98)70316-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nilsson S, Makela S, Treuter E, Tujague M, Thomsen J, Andersson G, Enmark E, Pettersson K, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Mechanisms of estrogen action. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1535–1565. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.4.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall JM, McDonnell DP. The estrogen receptor beta-isoform (ERbeta) of the human estrogen receptor modulates ERalpha transcriptional activity and is a key regulator of the cellular response to estrogens and antiestrogens. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5566–5578. doi: 10.1210/en.140.12.5566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sartorius CA, Melville MY, Hovland AR, Tung L, Takimoto GS, Horwitz KB. A third transactivation function (AF3) of human progesterone receptors located in the unique N-terminal segment of the B-isoform. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:1347–1360. doi: 10.1210/me.8.10.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roemer SC, Donham DC, Sherman L, Pon VH, Edwards DP, Churchill ME. Structure of the progesterone receptor-deoxyribonucleic acid complex: novel interactions required for binding to half-site response elements. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:3042–3052. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bain DL, Heneghan AF, Connaghan-Jones KD, Miura MT. Nuclear receptor structure: implications for function. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:201–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.031905.160308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klinge CM. Estrogen receptor interaction with estrogen response elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2905–2919. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.14.2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skafar DF, Koide S. Understanding the human estrogen receptor-alpha using targeted mutagenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;246:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang J, Singleton DW, Shaughnessy EA, Khan SA. The F-domain of estrogen receptor-alpha inhibits ligand induced receptor dimerization. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;295:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bolger R, Wiese TE, Ervin K, Nestich S, Checovich W. Rapid screening of environmental chemicals for estrogen receptor binding capacity. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106:551–557. doi: 10.2307/3434229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shiau AK, Barstad D, Loria PM, Cheng L, Kushner PJ, Agard DA, Greene GL. The structural basis of estrogen receptor/coactivator recognition and the antagonism of this interaction by tamoxifen. Cell. 1998;95:927–937. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norman AW, Mizwicki MT, Norman DP. Steroid-hormone rapid actions, membrane receptors and a conformational ensemble model. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:27–41. doi: 10.1038/nrd1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pike AC, Brzozowski AM, Hubbard RE. A structural biologist’s view of the oestrogen receptor. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;74:261–268. doi: 10.1016/S0960-0760(00)00102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tzukerman MT, Esty A, Santiso-Mere D, Danielian P, Parker MG, Stein RB, Pike JW, McDonnell DP. Human estrogen receptor transactivational capacity is determined by both cellular and promoter context and mediated by two functionally distinct intramolecular regions. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:21–30. doi: 10.1210/me.8.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanenbaum DM, Wang Y, Williams SP, Sigler PB. Crystallographic comparison of the estrogen and progesterone receptor’s ligand binding domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5998–6003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.5998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirata S, Shoda T, Kato J, Hoshi K. Isoform/variant mRNAs for sex steroid hormone receptors in humans. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2003;14:124–129. doi: 10.1016/S1043-2760(03)00028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]