Macrocyclic polymers are fascinating molecules that have triggered the curiosity of biologists, chemists and theoreticians since the discovery of cyclic DNA in living cells, more than 50 years ago [1, 2]. The topological restriction imposed by the cyclic architecture and the absence of chain ends in ring polymers result in original properties, some of which have yet to be completely elucidated. For example, it has been shown that cyclic polymers have smaller hydrodynamic volumes and radii and are less viscous than their linear analogues. Other specific properties such as diffusion and viscoelastic behaviors, which should also be strongly influenced by the cyclic topology, have been only marginally explored due to the limited availability of the corresponding high molar mass macrocycles.

Much less is known about more complex ring topologies such as knotted and catenated macromolecular rings (Scheme 1) that are also found in nature. Their mechanism of formation and their function are still unclear, and increasing efforts are being conducted to tentatively prepare and investigate their specific characteristics and properties.

Scheme 1.

Some cyclic polymer structures: a ring, b knotted ring, c catenated ring

Various examples of cyclized and pluri-cyclized DNA macromolecules have been reported in the literature since the pioneer work of Clayton [3] who identified circular forms of mitochondrial DNA in extracts of human leukemic leucocytes, both in the form of circular dimers and as catenanes made up of interlocked rings.

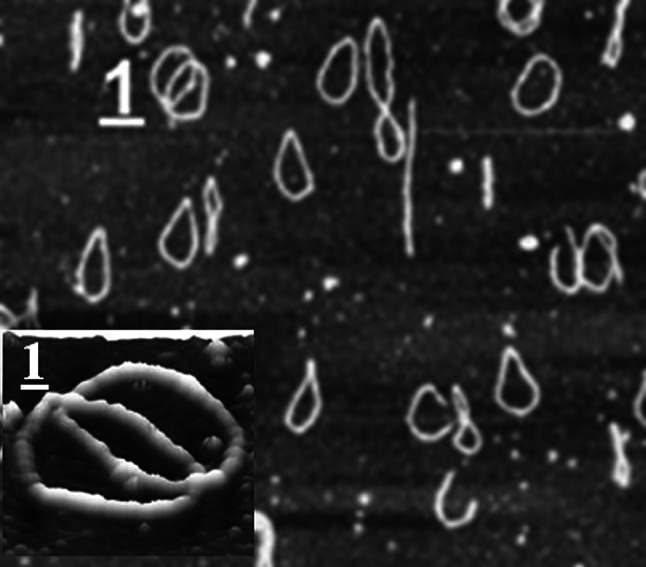

The winding of DNA in higher-order forms such as knots and catenanes was also shown on electron micrographs of DNA molecules coated with Echerichia coli RecA protein. It was found that DNA topoisomerase I of E. coli generates an equal mixture of (+) and (−) duplex DNA knots, as well as catenanes [4]. Together, RecQ helicase and topoisomerase III (Topo III) of E. coli comprise a potent DNA strand passage activity that can catenate covalently closed DNA [5]. The structure of the catenated DNA species formed by RecQ helicase and Topo III was directly assessed using atomic force microscopy (AFM) [6] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

DNA rings and catenane from [6]

The mechanism by which topoisomerase mediates knotting of supercoiled DNA was investigated by Wasserman [7]. Knotting was explained by DNA contacts stabilized by enzyme molecules.

DNA catenanes and large circular DNA have also been prepared by the reaction of T4 DNA ligase with linear DNA in the presence of nicked DNA [8, 9].

In addition to naturally occurring macrocycles and the investigation of their formation mechanisms, the preparation and the study of well-defined synthetic ring polymers as models of natural rings, has been implemented. Preliminary studies were first oriented towards polymer systems bearing reactive functions on the backbone chain, such as polydimethylsiloxanes [10], polyethers [11], polyesters [12], and so forth.

The synthesis of cyclic polymers by end-to-end coupling of chains, first proposed by Casassa [13], was experimentally performed in 1980 [14, 15] by the ring closure of living α, ω-difunctional polymer chains in the presence of a difunctional coupling agent, under very dilute conditions. Cyclization, which is a bimolecular process, leads generally in the case of large macromolecules to low yields, and fractionation procedures are required to remove residual linear chains and polycondensates. An alternative and more efficient route based on a unimolecular ring closing process has also been proposed [16–18]. It involves the end-to-end coupling of α,ω-heterodifunctional linear chains bearing mutually reactive end functions activated in the presence of a catalyst under diluted conditions.

Various other ways to prepare polymer rings have been recently explored [19–23], but again the preparation of relatively low molar mass macrocycles, typically less than 10,000 g/mol, is almost exclusively reported. Several reviews containing further details on the preparation methods of macrocycles can be found in the literature [24–26].

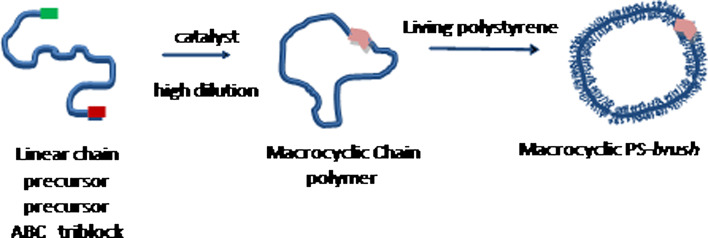

We have recently developed a new strategy to synthesize large polymer macrocycles and to investigate them by direct molecular imaging [27, 28]. The synthesis is based on the preparation of triblock copolymers, in which a long central block constituted of up to 1,000 chloroethyl vinyl ether (CEVE) monomer units is extended by two short sequences bearing mutually reactive functions, (Scheme 2). In a second step, the external sequences are selectively activated under high dilution to allow their intramolecular coupling and to form the corresponding macrocycles. Finally, in order to enlarge the macromolecular rings, oligomer chains are grafted onto the backbone ring to obtain the corresponding circular combs (Scheme 2). This can be readily achieved by reacting living anionic chains, such as polystyryl lithium, onto the chloride functions of the CEVE units.

Scheme 2.

Strategy for the preparation of large polymer rings and their conversion into comb macrocycles

Thanks to their large ring size and comb structure, the macrocyclic polymers can be directly analyzed by atomic force microscopy (AFM) as isolated molecular objects. Figure 2 shows AFM images of a series of cyclic PS combs in admixture with linear combs resulting from uncyclized PCEVE precursors. Their relative proportion corresponds to cyclization yields ranging from 60 to 70%. In addition, we can also notice the presence of noticeable amounts of various dimer structures corresponding to linear (LD) and cyclic (CD) dimers, tadpole (TD), and eight shape bicycles (BD).

Fig. 2.

AFM images of cyclic PS combs in admixture with linear and of secondary comb structures: linear dimer (L D) cyclic dimer (C D), tadpole (T D) and eight shape bicycles (B D)

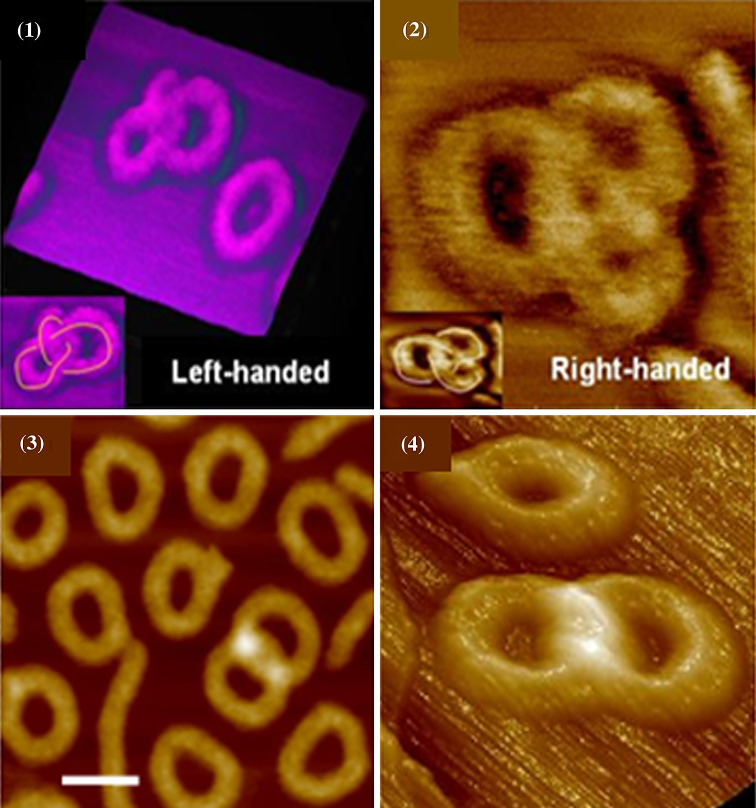

AFM molecular analysis can be pushed further by investigating molecule-by-molecule large sets of macromolecules. This permits the characterization of secondary polymer architectures that form in very small proportions (<1%). This approach allowed us to collect fascinating images of trefoil knotted rings and catenanes [29–32] and, by quantifying their relative amount, to establish their probable formation mechanism.

Knotted macromolecular rings, in the form of right and left topological diastereoisomers and [2] catenanes, are shown in Fig. 3. As emphasized on the inset of images (1) and (2), the path of the knot crosses three times over itself, which corresponds to the simplest trefoil knotted rings. Catenanes are constituted of two interlocked rings with two crossing points of greater eights that appear as two white spots on images (3) and (4).

Fig. 3.

(1) and (2) AFM phase images of trefoil knotted macromolecular rings. (3) and (4) AFM topographic images of [2] catenanes. The initial ring macromolecules were magnified by grafting polystyrene oligomers

Conclusion

Circular polymers are intriguing naturally occurring macromolecules that are found as single rings but also in the form of more complex structures such as knotted rings and catenanes.

Although some of their mechanisms of formation have been elucidated, it is still unclear whether their formation is a random and accidental process or if their original architecture is justified by specific properties developed by the corresponding circular structure. The recent progress in the synthesis and in the methods of investigation of well-defined synthetic ring polymers, which are interesting models of natural macrocycles, will contribute to a better understanding of the specific role of this fascinating class of macromolecules.

References

- 1.Vinograd J, Lebowitz J, Radloff R, Watson R, Laipis P. The twisted circular form of polyoma viral DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1965;53:1104–1111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.53.5.1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubelcco R, Vogt M. Evidence for a ring structure of polyoma virus DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1963;50:236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.50.2.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clayton DA, Vinograd J. Circular dimer and catenate forms of mitochondrial DNA in human leukaemic leucocytes. Nature. 1967;216:652–657. doi: 10.1038/216652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krasnow MA, Stasiak A, Spengler SJ. Determination of the absolute handedness of knots and catenanes of DNA. Nature. 1983;304:559–560. doi: 10.1038/304559a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harmon FG, DiGate RJ, Kowalczykowski SC. RecQ helicase and topoisomerase III comprise a novel DNA strand passage function: a conserved mechanism for control of DNA recombination. Mol Cell. 1999;3:611–620. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80354-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harmon FG, Brockman JP, Kowalczykowski SC. RecQ Helicase stimulates both dna catenation and changes in dna topology by topoisomerase III. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42668–42678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302994200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wasserman SA, Cozzarelli NR. Supercoiled DNA-directed knotting by T4 topoisomerase. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:20567–20573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamaguchi H, Kubota K, Harada A. Preparation of DNA catenanes and observation of their topological structures by atomic force microscopy. Nucleic acids symp ser. 2000;44:229–230. doi: 10.1093/nass/44.1.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamaguchi H, Kubota K, Harada A. Direct observation of DNA catenanes by atomic force microscopy. Chem Lett. 2000;4:384–385. doi: 10.1246/cl.2000.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Semlyen JA, Wright PV. Equilibrium ring concentrations and the statistical conformations of polymer chains I-oligomeric dimethylsiloxanes. Polymer. 1969;10:543–553. doi: 10.1016/0032-3861(69)90068-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivin KJ, Leonard J. The equilibrium polymerization of monomers which are solvents for their polymers: case of tetrahydrofuran. Polymer. 1965;6:621–624. doi: 10.1016/0032-3861(65)90057-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper DR, Semlyen JA. Equilibrium ring concentrations and the statistical conformations of polymer chains: part 11. Cyclics in poly (ethylene terephthalate) Polymer. 1973;14:185–192. doi: 10.1016/0032-3861(73)90045-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casassa EF. Some statistical properties of flexible ring polymers. J Polym Sci A. 1964;3:605–614. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geiser D, Höcker H. Synthesis and investigation of macrocyclic polystyrene. Macromolecules. 1980;13:653–656. doi: 10.1021/ma60075a032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hild G, Kohler A, Rempp P. Synthesis of ring-shaped macromolecules. Eur Polym J. 1980;16:525–527. doi: 10.1016/0014-3057(80)90136-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rique-Lurbet L, Schappacher M, Deffieux A. A new strategy for the synthesis of cyclic polystyrenes: principle and application. Macromolecules. 1994;27:6318–6324. doi: 10.1021/ma00100a014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schappacher M, Deffieux A. α-acetal-ω-bis (hydroxymethyl) heterodifunctional polystyrene: synthesis, characterization, and investigation of intramolecular end-to-end ring closure. Macromolecules. 2001;34:5827–5832. doi: 10.1021/ma0100955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schappacher M, Deffieux A. Synthesis, characterization, and intramolecular end-to-end ring closure of α-isopropylidene-1, 1-dihydroxymethyl-ω-diethylacetal polystyrene-block-polyisoprene block copolymers. Macromol Chem Phys. 2002;203:2463–2469. doi: 10.1002/macp.200290033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tezuka Y, Mori K, Oike H. Efficient synthesis of cyclic poly (oxyethylene) by electrostatic self-assembly and covalent fixation with telechelic precursor having cyclic ammonium salt groups. Macromolecules. 2002;35:5707–5711. doi: 10.1021/ma020182c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tezuka Y, Oike H. Topological polymer chemistry. Prog Polym Sci. 2002;27:1069–1122. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6700(02)00009-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bielawski CW, Benitez D, Grubbs RH. An “endless” route to cyclic polymers. Science. 2002;297:2041–2044. doi: 10.1126/science.1075401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eugene DM, Grayson SM. Efficient preparation of cyclic poly (methyl acrylate)-block-poly (styrene) by combination of atom transfer radical polymerization and click cyclization. Macromolecules. 2008;41:5082–5084. doi: 10.1021/ma800962z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laurent BA, Grayson SM. An efficient route to well-defined macrocyclic polymers via “click” cyclization. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:4238–4239. doi: 10.1021/ja0585836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deffieux A, Borsali R. Controlled synthesis and properties of cyclic polymers. Weinheim: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roovers J. Cyclic polymers. Dordrecht: Kluwer; 2000. pp. 347–360. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hogen-Esch TE. Synthesis and characterization of macrocyclic vinyl aromatic polymers. J Polym Sci A. 2006;44:2139–2155. doi: 10.1002/pola.21331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deffieux A, Schappacher M, Hirao A, Watanabe T. Synthesis and AFM structural imaging of dendrimer-like star-branched polystyrenes. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5670–5672. doi: 10.1021/ja800881k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schappacher M, Deffieux A. Synthesis of macrocyclic copolymer brushes and their self-assembly into supramolecular tubes. Science. 2008;319:1512–1515. doi: 10.1126/science.1153848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amabilino DB, Stoddart JF. Interlocked and intertwined structures and superstructures. Chem Rev. 1995;95:2725–2828. doi: 10.1021/cr00040a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dietrich-Buchecker C, Colasson BX, Sauvage JP. Molecular knots. Top Curr Chem. 2005;249:261–283. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dobrowolski JC. Classification of topological isomers: knots, links, Rotaxanes, etc. Croat Chem Acta. 2003;76:145–152. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frisch HL, Wasserman E. Chemical topology. J Am Chem Soc. 1961;83:3789–3795. doi: 10.1021/ja01479a015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]