Abstract

The central dogma in radiation biology is that nuclear DNA is the critical target with respect to radiosensitivity. In accordance with the theoretical expectations, and in the absence of a conclusive model, the general consensus in the field has been to view chromatin as a homogeneous template for DNA damage and repair. This paradigm has been called into question by recent findings indicating a disparity in γ-irradiation-induced γH2AX foci formation in euchromatin and heterochromatin. Here, we have extended those studies and provide evidence that γH2AX foci form preferentially in actively transcribing euchromatin following γ-irradiation.

Keywords: Euchromatin, Heterochromatin, Histone methylation, γH2AX, Double strand break, γ-Radiation

Introduction

Phosphorylation of the H2A histone variant, H2AX, at Ser-139 to form γH2AX is a rapid response to the formation of DNA double-strand breaks (DSB) [1]. This phosphorylation event is mediated by members of the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase-like kinase family of serine/threonine protein kinases, including ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM), ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3 related (ATR), and DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) [2]. For example, within minutes following exposure to γ-radiation, γH2AX forms discrete nuclear foci, which spread over megabase chromatin domains surrounding the DNA lesion, reaching a maximal size in 30 min [2]. Importantly, these foci are easily detectable using immunofluorescence-based assays. Indeed, microscopic quantitation of γH2AX foci has become an important biological tool for investigating DNA damage and repair, and has provided new insights relating to these processes in the context of chromatin.

Without immediately realizing the impact (the aim of the study was to examine the effect of the histone deacetylase inhibitor, Trichostatin A, on radiosensitivity), we previously established an asymmetric response to γ-irradiation in euchromatin and heterochromatin in human erythroleukemic, K562 cells [3]. Using γH2AX as a molecular marker of DSBs and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays, we demonstrated that heterochromatic sites represented by satellite 2 juxtacentromeric and α-satellite centromeric sequences are resistant to γH2AX accumulation, compared to active (serum albumin, glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) euchromatic compartments [3]. Similarly, in another study, ChIP analysis following the induction of a site-specific DSB indicated that γH2AX is largely excluded from heterochromatic loci in budding yeast [4].

Examination of our own and published immunofluorescence microscopic images in which 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) is used to stain the nuclei indicates the deficiency of γH2AX foci in heterochromatin (assumed to be reflected by brightly stained DAPI regions), highlighting the generality of the ChIP findings. A striking example of the exclusion of γH2AX in brightly stained DAPI regions has been illustrated using DSB repair-deficient LIG4−/−MEF cells irradiated with 16 Gy [5]. Furthermore, in an elegant study, the non-histone chromatin protein, HP1α, and histone H3 trimethylated at lysine 9 (H3K9Me3) were used as markers of heterochromatic regions to demonstrate that γH2AX foci form preferentially in euchromatin, following irradiation of MCF7 breast carcinoma cells [6]. This was the first study to demonstrate the disparity of radiation-induced γH2AX formation in euchromatin and heterochromatin by immunofluorescence.

Here, we extended these studies using a panel of antibodies to either mono-, di- or tri-methylated histone H3 at lysine 9 (H3K9Me1, H3K9Me2, H3K9Me3) and lysine 4 (H3K4Me1, H3K4Me2, H3K4Me3). More specifically, we used immunofluorescence microscopy to investigate the spatial relationship between γ-radiation-induced γH2AX formation and the epigenetic markers in K562 cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and immunofluorescence

K562 cells were grown in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine and 20 μg/ml gentamicin in a humidified 5% CO2 environment. Cells were either unirradiated or irradiated with 2 Gy using a 137Cs source (Gammacell 1000 Elite irradiator; Nordion International, ON, Canada; 1.6 Gy/min) on ice and were immediately returned to 37°C for a 60-min incubation. Aliquots (7 × 104) of cells were cytospun onto polysine slides, fixed by exposure to 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min and permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min. Following three 5-min washes with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), samples were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min. Cells were then exposed to primary antibodies against γH2AX (mouse monoclonal anti-phospho histone H2AX antibody; Upstate, New York, USA) or with one of the epigenetic markers: H3K9Me, H3K9Me2, H3K9Me3, H3K4Me, H3K4Me2, H3K4Me3 (rabbit polyclonal; Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Primary antibodies were used at a 1:500 dilution and incubated for 2 hr in a dark humidified environment on a rotating platform at room temperature. Slides were washed with PBS as described above and a 1:500 dilution of Alexa-488 conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody or Alexa-546 conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Molecular Probes, OR, USA) was added and the cells were incubated in the dark on a rotating platform for 1 h. Slides were washed as above and then 1:1,000 diluted TO-PRO-3 (Molecular Probes) was added and incubated in the dark for 5 min on a rotating platform and slides were rinsed with PBS. Slides were mounted after an overnight incubation with Prolong Gold antifade (Molecular Probes).

Using a ×63 oil plan–apochromat objective (NA = 1.40), images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta laser confocal microscope fitted with a Z-stage motor. Images were acquired with a step size of 0.25 μ and in a 2,048 × 2,048 pixel format using Argon (Alexa 488) and HeNe (Alexa-546 and TO-PRO-3) lasers. Twelve to fifteen consecutive Z-sections were acquired. Images were exported as TIFF files and analysed using Metamorph (Molecular Probes) to create Z-projections from image stacks. For line scan analysis, a straight line was drawn across cell nuclei using Metamorph software, and the overlap of each channel was measured as the distance versus gray levels, and relative fluorescence intensities were plotted.

Results and discussion

It is well established that methylated H3K9, particularly H3K9Me3, is a hallmark of constitutive heterochromatin, and that H3K9Me and H3K9Me2 are associated with transcriptional silencing [7, 8]. Methyl groups on the K9 residue are substrates for the chromodomain of HP1 [7]. In contrast, methylation of H3K4 has been associated with transcriptionally active genes [9]. More specifically, H3K4Me3 is most prominent in regions that are actively transcribed by polymerase II (5′ end of genes), H3K4Me2 is spread throughout genes and is more pronounced in the middle of coding regions, and H3K4Me largely localizes at the 3′ ends of genes [9].

Our findings indicate, as expected, that in untreated K562 cells H3K9Me3 is enriched in brightly stained chromatin regions, in contrast to methylated H3K4 which is distributed largely in euchromatin. The localization of H3K9Me and H3K9Me2 is not as explicit (Fig. 1). Furthermore, our results clearly indicate that 60 min following 2 Gy irradiation, γH2AX foci are predominantly formed in regions consisting of enhanced methylated H3K4 and are excluded from regions containing relatively high levels of methylated H3K9 (Fig. 2). Interestingly, our data show γH2AX foci overlapping with H3K4Me, H3K4Me2 and H3K4Me3 suggesting that the degree of methylation is not of significant influence (Fig. 1).

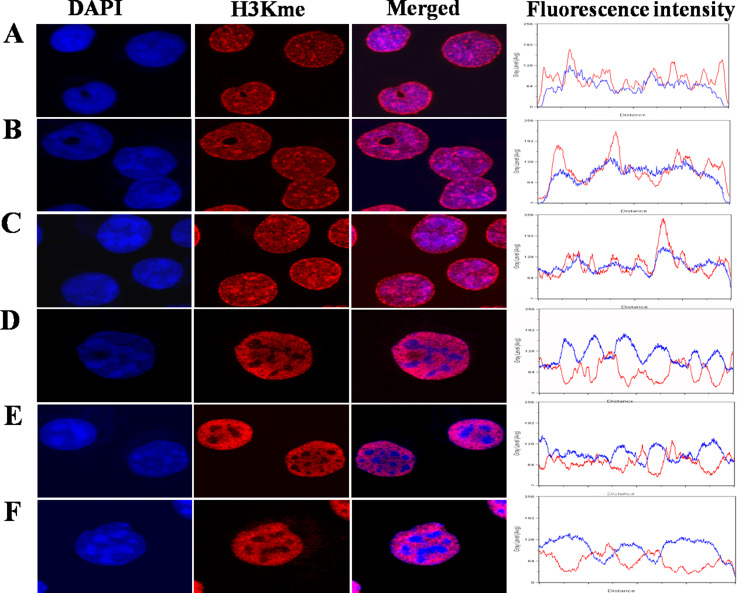

Fig. 1.

Relationship between chromatin staining and methylated H3K9 and methylated H3K4 in K562 cells immunofluorescence analysis of the nuclear distribution of H3K9Me [Me (A), Me 2 (B), Me 3 (C)] representing constitutive heterochromatin or H3K4 [Me (D), Me2 (E), Me3 (F)], an epigenetic mark of euchromatin (red). DNA was stained with TOPPRO3 (blue). Relative fluorescence intensity plots were generated from the merged images with the lines drawn through the brightest H3K9Me or H3K4Me regions

Fig. 2.

γH2AX foci form predominantly in actively transcribing euchromatin. Immunofluorescence analysis of γH2AX formation (green) in human erythroleukemic K562 cells, 60 min after γ-irradiation (2 Gy). γH2AX foci are shown in relation to either H3K9Me [Me (A), Me 2 (B), Me 3 (C)] representing constitutive heterochromatin and gene silencing or H3K4 [Me (D), Me2 (E), Me3 (F)], an epigenetic mark of euchromatin (red). DNA was stained with TOPPRO3 (blue). Relative fluorescence intensity plots were generated from the merged images with the lines drawn through the brightest H3K9Me or H3K4Me regions

Given that methylated H3K9 is an epigenetic imprint of constitutive heterochromatin and transcriptional silencing and methylated H3K4 is tightly correlated with euchromatic gene transcription, our findings demonstrate, to our knowledge for the first time, a close correlation between γ-radiation-induced γH2AX formation and actively transcribing euchromatic regions. This is consistent with the prevailing ideas regarding the structural organization of chromatin and the processes of DNA damage and repair. Collectively, our results together with the emerging reports highlight that chromatin is a heterogenous template with heterochromatin being refractory to γH2AX modification and DSB repair [10]. Although the mechanisms accounting for this disparity are not yet defined, the most tempting hypothesis is that the highly compacted nature of heterochromatin inhibits responses to DNA damage. Undoubtedly, the central importance in oncology dictates that further studies aimed at unraveling the relationship between chromosomal subdomains and DNA damage and repair will be intensely pursued.

Acknowledgments

The support of the Australian Institute of Nuclear Science and Engineering is acknowledged. T.C.K. was the recipient of AINSE awards and is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (566559). R.V. is supported by a Melbourne Research Scholarship from the University of Melbourne.

Footnotes

R. S. Vasireddy and T.C. Karagiannis contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Rogakou EP, Pilch DR, Orr AH, Ivanova VS, Bonner WM. DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5858–5868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogakou EP, Boon C, Redon C, Bonner WM. Megabase chromatin domains involved in DNA double-strand breaks in vivo. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:905–916. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.5.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karagiannis TC, Harikrishnan KN, El-Osta A. Disparity of histone deacetylase inhibition on repair of radiation-induced DNA damage on euchromatin and constitutive heterochromatin compartments. Oncogene. 2007;26:3963–3971. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JA, Kruhlak M, Dotiwala F, Nussenzweig A, Haber JE. Heterochromatin is refractory to gamma-H2AX modification in yeast and mammals. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:209–218. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinner A, Wu W, Staudt C, Iliakis G. Gamma-H2AX in recognition and signaling of DNA double-strand breaks in the context of chromatin. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:5678–5694. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowell IG, Sunter NJ, Singh PB, Austin CA, Durkacz BW, Tilby MJ. gammaH2AX foci form preferentially in euchromatin after ionising-radiation. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin C, Zhang Y. The diverse functions of histone lysine methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:838–849. doi: 10.1038/nrm1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters AH, Mermoud JE, O’Carroll D, Pagani M, Schweizer D, Brockdorff N, Jenuwein T. Histone H3 lysine 9 methylation is an epigenetic imprint of facultative heterochromatin. Nat Genet. 2002;30:77–80. doi: 10.1038/ng789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruthenburg AJ, Allis CD, Wysocka J. Methylation of lysine 4 on histone H3: intricacy of writing and reading a single epigenetic mark. Mol Cell. 2007;25:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodarzi AA, Noon AT, Deckbar D, Ziv Y, Shiloh Y, Lobrich M, Jeggo PA. ATM signaling facilitates repair of DNA double-strand breaks associated with heterochromatin. Mol Cell. 2008;31:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]