Abstract

Transgenic plants of Arabidopsis bearing the spinach (Spinacia oleracea) nitrite reductase (NiR, EC 1.7.7.1) gene that catalyzes the six-electron reduction of nitrite to ammonium in the second step of the nitrate assimilation pathway were produced by use of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter and nopaline synthase terminator. Integration of the gene was confirmed by a genomic polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Southern-blot analysis; its expression by a reverse transcriptase-PCR and two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis western-blot analysis; total (spinach + Arabidopsis) NiR mRNA content by a competitive reverse transcriptase-PCR; localization of NiR activity (NiRA) in the chloroplast by fractionation analysis; and NO2 assimilation by analysis of the reduced nitrogen derived from NO2 (NO2-RN). Twelve independent transgenic plant lines were characterized in depth. Three positive correlations were found for NiR gene expression; between the total NiR mRNA and total NiR protein contents (r = 0.74), between the total NiR protein and NiRA (r = 0.71), and between NiRA and NO2-RN (r = 0.65). Of these twelve lines, four had significantly higher NiRA than the wild-type control (P < 0.01), and three had significantly higher NO2-RN (P < 0.01). Each of the latter three had one to two copies of spinach NiR cDNA per haploid genome. The NiR flux control coefficient for NO2 assimilation was estimated to be about 0.4. A similar value was obtained for an NiR antisense tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum cv Xanthi XHFD8). The flux control coefficients of nitrate reductase and glutamine synthetase were much smaller than this value. Together, these findings indicate that NiR is a controlling enzyme in NO2 assimilation by plants.

NO2, a major air pollutant that causes acid rain, reacts with volatile organic compounds in the atmosphere, producing photooxidants, including ozone. A 1980 estimate put the total natural and anthropogenic emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx) at 150 million tons per year, more than one-half of which were from natural sources (Yunus et al., 1996). Road transport, the major anthropogenic source of NOx in most developed countries, in 1984 accounted for as much as 75% of the NOx in some metropolitan cities, and the percentage has continued to rise with increases in road traffic volume. In many developing countries as well, petro-fueled motor vehicles are the principal source of NOx (Yunus et al., 1996).

Plants take up NO2 (Hill, 1971) and assimilate its nitrogen through a primary nitrate assimilation pathway (Zeevaart, 1976; Yoneyama and Sasakawa, 1979a; Kaji et al., 1980; Rowland et al., 1985; Wellburn, 1990; Morikawa et al., 1998; Ramge et al., 1993). Moreover, nitrate reductase (NR, EC 1.6.6.1) and nitrite reductase (NiR, EC 1.7.7.1) activities in leaves frequently are enhanced by exposure to NO2 (Zeevaart, 1974; Yoneyama and Sasakawa, 1979a; Wellburn et al., 1981; Murray and Wellburn, 1985; Takeuchi et al., 1985; Wingsle et al., 1987; Yu et al., 1988), as when nitrate is supplied. Apart from the study by Rowland-Bamford et al. (1989), which showed that the rate of NO2 uptake in NR-deficient barley mutants was similar to that in non-mutated plants, little is known about the role of these enzymes of the primary nitrate assimilation pathway in NO2 assimilation.

Nitrite ions, considered toxic to plant cells (Shimazaki et al., 1992; Vaucheret et al., 1992; Duncanson et al., 1993; Lea, 1993), are increased in leaf cells of a variety of plant species after fumigation with NO2 (Zeevaart, 1976; Yoneyama and Sasakawa, 1979a; Takeuchi et al., 1985; Yu et al., 1988; Shimazaki et al., 1992; Morikawa et al., 1998), sometimes resulting in visible leaf injury (Yoneyama et al., 1979b; Shimazaki et al., 1992). Plants that have high NiR activity (NiRA) are considered to have a high tolerance for NO2 (Yoneyama et al., 1979b; Shimazaki et al., 1992). We speculated that NiR is a controlling enzyme in NO2 assimilation and that overexpression of the NiR gene and an increase in the amount of NiR enzyme produced by genetic engineering would improve the ability of plants to assimilate NO2.

Ferredoxin-dependent NiR, which catalyzes the six-electron reduction of nitrite (oxidation state +3) to ammonium (oxidation state −3) in the second step of the nitrate assimilation pathway, is localized in the chloroplast and its gene is nuclear encoded. NiR cDNAs of various higher plant species have been cloned: spinach (Back et al., 1988), maize (Lahners et al., 1988), birch (Friemann et al., 1992), tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum cv Xanthi XHFD8; Vaucheret et al., 1992; Kronenberger et al., 1993), Arabidopsis (Tanaka et al., 1994), rice (Terada et al., 1995), kidney bean (Sander et al., 1995), and beet (Schneider et al., 1999).

With an eventual aim to produce “NO2-philic” plants that can grow with NO2 as sole nitrogen source, we have been studying the metabolism of NO2 in plants (Morikawa et al., 1998). As far as we are aware, only one study by Crété et al. (1997) on NiR overexpressors has been reported, but no reports on the analysis of NO2 assimilation by transgenic plants have been published. Here we produced transgenic plants of Arabidopsis bearing chimeric spinach NiR gene, characterized the integration of the transgene in the genome and its expression in those plants by various methods such as Southern blot, quantitative reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR and two-dimensional PAGE western-blot analyses, and analyzed NO2 assimilation in transgenic plants by fumigation with 15N-labled NO2 followed by Kjeldahl digestion and mass spectrometry. Moreover, results were compared with those of transformants in which NR and Gln synthetase (GS) genes are overexpressed.

RESULTS

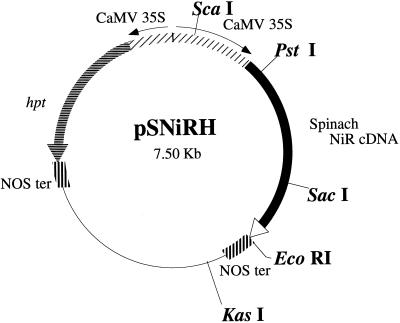

Plasmid pSNIRH bearing spinach NiR cDNA controlled by the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter, nopaline synthase (NOS) terminator, and the chimeric hpt expression cassette (Fig. 1) was introduced to root sections of Arabidopsis by particle bombardment. Putative transgenic calli were selected on hygromycin-containing medium. Thirty-seven shoots, which developed from these independent hygromycin-resistant calli and which had a 352-bp band in a PCR with primers specific to spinach NiR cDNA, were allowed to mature and set seeds. The T2 to T4 plants obtained by self-pollination were randomly chosen. About 20 seedlings per each line were first tested for segregation of the 325-band specific to spinach NiR cDNA. Homozygous lines for the transgene as determined by the presence of the 325-bp PCR band were called “hm” lines and heterozygous ones that segregated the band were called “ht” ones. Those plants bearing the introduced spinach NiR cDNA were analyzed further.

Figure 1.

Diagram of plasmid pSNIRH. CaMV 35S, CaMV 35S promoter; NOS ter, NOS terminator; hpt, hygromycin phosphotransferase.

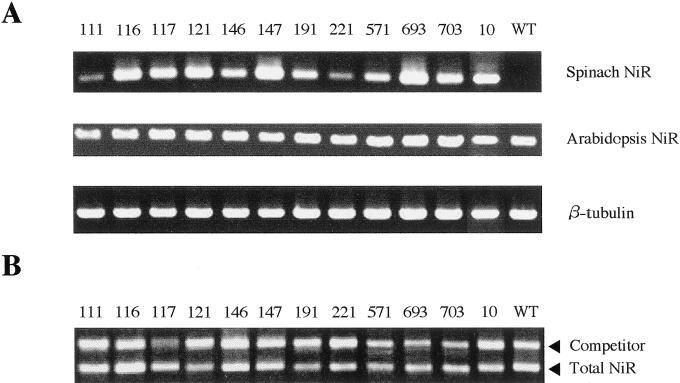

Typical RT-PCR analysis results for expressions of the introduced spinach NiR cDNA and endogenous NiR gene in the 12 transgenic lines of Arabidopsis are shown in Figure 2A. Their mRNA extracts were analyzed by the use of primers specific to spinach NiR and Arabidopsis NiR (see “Materials and Methods”). All the transgenic plants had the 352-bp band specific to spinach NiR cDNA (lanes 1–12), whereas no wild-type ones had it (lane WT). The fact that both bands specific to spinach and Arabidopsis NiR are present in all the transgenic plants indicates that both NiR genes are expressed in all of them. Total (spinach + Arabidopsis) NiR mRNAs were quantified by the competitive RT-PCR (Fig. 2B; see also Table I), in which a 1,668-bp intron-containing DNA fragment of NiR gene was used as the competitor (see “Materials and Methods”). In Figure 2B, PCR signals of the competitor that showed were closest to those of the target cDNA are shown. Quantitative results, based on the competitive RT-PCR analysis, of the total NiR mRNA content of each transgenic line will be discussed below.

Figure 2.

RT-PCR analysis of NiR mRNA from transgenic (lanes 111–10) and wild-type (lane WT) Arabidopsis plants. A, Without competitor DNAs. Product sizes are 352 bp for the introduced spinach NiR cDNA (top), 219 bp for Arabidopsis NiR gene (middle), and 1,563 bp for the β-tubulin of Arabidopsis (bottom). B, Typical results of competitive RT-PCR for quantification of total (spinach + Arabidopsis) NiR mRNAs. Product sizes are 1,314 bp for total NiR cDNAs and 1,668 bp for competitor. The amount of the competitor varied from 2.5 × 105 to 5 × 106 copies per the PCR reaction mixture (see “Materials and Methods”).

Table I.

Copy number of spinach NiR cDNA, total NiR mRNA, total NiR protein, NiRA, and NO2-RN in transgenic Arabidopsis plants carrying spinach NiR cDNA under control of the CaMV 35S promoter and NOS terminator

| Line No. | Copy No. | Total NiR mRNA | Total NiR Protein | NiRA | Reduced Nitrogen Derived from NO2 (NO2-RN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nmol NO2− min−1 mg−1 protein | mg nitrogen g−1 dry wt | ||||

| Wild type | 100.0 ± 75.1 [3] | 100.0 ± 0 [3] | 124.7 ± 19.0 (100) [3] | 1.18 ± 0.08 (100) [3] | |

| 693 hm | 1 | 967.7 ± 0 [3] | 142.2 ± 11.8 [3] | 192.1 ± 2.2* (154) [3] | 1.65 ± 0.14* (140) [3] |

| 116 hm | ≧5 | 145.2 ± 68.4 [3] | 119.1 ± 22.8 [3] | 134.2 ± 13.8 (108) [3] | 1.68 ± 0.33 (142) [2] |

| 10 hm | 1 | 709.7 ± 365.0 [3] | 150.0 ± 12.1 [3] | 197.0 ± 2.6* (158) [2] | 1.55 ± 0.04* (131) [3] |

| 117 hm | ≧4 | 145.2 ± 68.4 [3] | 108.9 ± 43.1 [3] | 196.7 ± 7.4* (158) [3] | 1.39 ± 0.22 (118) [2] |

| 121 hm | 2 | 483.9 ± 0 [3] | 176.6 ± 4.1 [3] | 226.2 ± 9.9* (181) [3] | 1.47 ± 0.06* (125) [3] |

| 191 hm | ≧6 | 80.6 ± 22.8 [2] | 82.1 ± 4.0 [3] | 102.6 ± 9.4 (82) [3] | 1.20 ± 0.10 (102) [3] |

| 147 ht | 1 | 806.5 ± 228.1 [3] | 132.4 ± 22.3 [3] | 143.0 ± 9.8 (115) [5] | 0.92 ± 0.08 (78) [2] |

| 571 ht | ≧5 | 129.0 ± 45.6 [3] | 82.8 ± 26.8 [3] | 112.6 ± 18.0 (90) [5] | 0.98 ± 0.11 (83) [3] |

| 146 ht | ≧2 | 80.6 ± 22.8 [3] | 123.9 ± 48.9 [3] | 121.9 ± 15.1 (98) [5] | 1.06 ± 0.05 (90) [2] |

| 703 ht | ≧3 | 129.0 ± 45.6 [3] | 116.8 ± 4.7 [3] | 103.3 ± 11.2 (83) [3] | 1.18 ± 0.33 (100) [2] |

| 111 ht | ≧1.5 | 80.6 ± 22.8 [3] | 91.7 ± 9.3 [3] | 162.4 ± 26.3 (130) [5] | 1.31 ± 0.04 (111) [3] |

| 221 ht | ≧4.5 | 80.6 ± 22.8 [2] | 75.9 ± 34.5 [3] | 108.4 ± 13.9 (87) [3] | 1.02 ± 0.15 (86) [3] |

hm Lines did not segregate the PCR band specific to spinach NiR cDNA, whereas ht lines segregated this band (see text for details). Values are means ± sd of more than two independent experiments. One experiment consisted of a sample prepared from a 5- to 6-week-old plant of transgenic or wild-type Arabidopsis. Nos. in parentheses are NiRA- or NO2-derived reduced nitrogen relative to the value for wild-type plants. Nos. in brackets are the no. of experiments. Values with asterisks (P < 0.01) are significantly different as determined by ANOVA with Dunnett's test. Copy no. of spinach NiR cDNA per haploid genome was determined by Southern-blot analysis of genomic DNA with spinach NiR cDNA as the probe. Total mRNA was determined by competitive RT-PCR with primers specific to spinach NiR and Arabidopsis NiR. Total NiR protein content was determined by western-blot analysis with anti-spinach NiR antibody. NO2-RN was determined after fumigation with 4 μL L−1 NO2 for 8 h followed by Kjeldahl digestion of the leaves, as described in “Materials and Methods.”

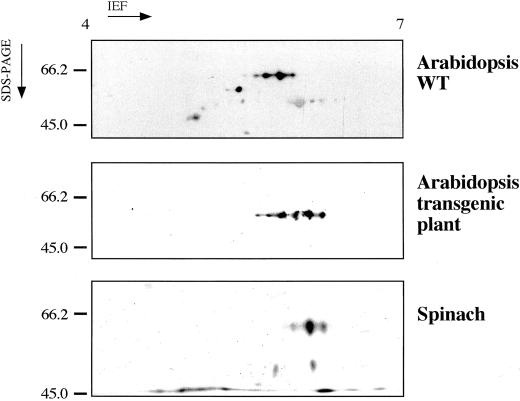

Figure 3 shows typical results of two-dimensional PAGE western-blot analysis with anti-spinach NiR antibody of the protein extract from a transgenic line (line 121, which had the highest NiRA among the 12, see Table I), together with results for wild-type Arabidopsis and spinach. The transgenic plants gave six spots at about the molecular mass of 60 kD and pIs ranging from 5 to 6. In contrast, wild-type Arabidopsis gave four (acidic pIs) and spinach gave three (basic pIs) spots that had similar molecular masses. Three to four of the acidic pI spots of the transgenic plants corresponded to the spots of wild-type Arabidopsis, and the remaining two to three basic pI spots to those of spinach, evidence that the introduced spinach NiR cDNA was successfully expressed and translated in the transgenic plants. Arabidopsis NiR protein has an estimated molecular mass of 63 kD and a pI of 5.6, based on cDNA sequence data (Tanaka et al., 1994), and spinach NiR protein had a molecular mass of 63 kD and a pI of 5.9, based on its NiR cDNA sequence data (Back et al., 1988) obtained with DNASIS software (Hitachi Software Engineering Co., Yokohama, Japan). Ida and Mikami (1986) previously reported the molecular mass of spinach NiR polypeptide as 63 kD. These values all are consistent with ours found by western-blot analysis.

Figure 3.

Western-blot analysis of NiR proteins from transgenic and wild-type Arabidopsis and spinach plants. Two-dimensional PAGE was done with a polyclonal antibody raised against spinach NiR.

Based on quantification of the NiR protein spots on the two-dimensional gels as shown in Figure 3, the contribution of the transgene in the total NiR proteins in the line 121 was estimated to be about 50%.

The introduced spinach NiR cDNA had the 5′ transit peptide for chloroplastic targeting. Whether this peptide functions in transgenic Arabidopsis cells needed to be clarified. Protoplasts were isolated from transgenic and wild-type Arabidopsis leaves and were ruptured by osmotic treatment to isolate chloroplasts. Western-blot analysis with anti-lettuce GS antibody (provided by Dr. Go Takeba, Kyoto Prefectural University) showed that the chloroplast fraction had only chloroplastic, and no cytosolic GS—evidence that this fraction is free of cytosol contamination (data not shown). NiRA in the chloroplast fraction was determined next and the value was compared with the total NiRA of the intact leaf. Results are shown in Table II. Based on recovery of the RBCS from the chloroplast fraction, chloroplast yields (intensity of the RBCS, band of the chloroplast fraction/intensity of RBCS, band in the intact leaf) were estimated as 34.7% for the transgenic and 39.2% for the wild-type plants (Table II). The NiRA in the chloroplast fraction (NiRA in isolated chloroplasts/chloroplast yield) was 157.2 for the transgenic and 81.9 (nmol NO2− min−1 mg−1 chlorophyll) for the wild-type plants. The former value was 97.5% of the total NiR leaf activity in the transgenic and 90.3% in the wild-type Arabidopsis plants, a clear indication that the chloroplast transit peptide derived from spinach functions in the cells of Arabidopsis in the transport of ectopically expressed spinach NiR translates to the chloroplast.

Table II.

NiR activity in chloroplast fractions from transgenic and wild-type Arabidopsis plants

| NiRA

|

Relative Intensity of Small Rubisco Subunit (RBCS) Band

|

NiRA (calc.) in Chloroplasts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole leaf | Chloroplast fraction | Whole leaf | Chloroplast fraction | ||

| nmol NO2− × min−1 mg−1 chlorophyll | nmol NO2− × min−1 mg−1 chlorophyll | ||||

| Wild type | 90.7 | 28.4 | 100 | 34.7 | 81.9 (90.3) |

| 121 | 161.3 | 61.6 | 100 | 39.2 | 157.2 (97.5) |

Values in parentheses are for chloroplast NiRA relative to the total NiRA in intact leaves. Protoplasts were isolated from wild-type and transgenic plants (line 121) of Arabidopsis. Chloroplasts were isolated as described in “Materials and Methods.” NiRAs were measured in extracts from intact leaves and from isolated chloroplasts. Chloroplast yield was estimated by a comparison of the intensity of the RBCS band in the SDS-PAGE gel after silver staining of the intact leaf sample with that of the corresponding chloroplast fraction band. NiRA (calc.) in the chloroplast fraction = [NiRA of chloroplast fraction/(RBCS band intensity in the chloroplast fraction/RBCS band intensity in RBCS in the intact leaf)] × 100 was estimated from these two values. Experiments were repeated twice. The deviation of NiRA (calc.) was less than 10%. One experiment used all leaves from 10 plants of a transgenic line or non-transformed plant.

Table I shows the copy number of the introduced spinach NiR cDNA per haploid genome of Arabidopsis, total (spinach + Arabidopsis) NiR mRNA content as determined by the competitive RT-PCR, total NiR protein content as determined by western-blot analysis, NiRA, and NO2-RN of the 12 transgenic lines. Six “hm” lines (693, 116, 10, 117, 121, and 191) did not segregate the 325-bp band specific to spinach NiR cDNA when tested as described above. Each of six “ht” lines (147, 571, 146, 703, 111, and 221) segregated the band. The copy number of spinach NiR cDNA per haploid genome varied from one to six or more. The segregation ratio varied from 16:4 to 17:3, which is very close to a Mendelian 3:1 ratio, suggesting that the transgenes are located in a single locus in these transgenic lines. In general, lines with a low copy number had higher total NiR mRNA content. The relative total NiR mRNA content of the transgenic lines varied markedly from 80.6% to 967.7%, where the average signal intensity of the competitive PCR band corresponding to the total NiR mRNA of the control wild-type plants being taken as 100. Lines 693, 10, 121, and 147, all of which had a low copy number of the transgene, had high total mRNA (more than or close to 500% of the control). On the other hand, those lines having multiple copies of the transgene such as lines 191 and 221 had low total NiR mRNA. These results suggest that cosuppression of NiR expression may have occurred at least in some plants of these transgenic lines. The total NiR protein content of the transgenic plants was also not always greater than that of the wild-type control, where the average signal intensity of the two-dimensional western band corresponding to the NiR protein of the control wild-type plants being taken as 100. This value varied in a rather narrow range (from 75.9%–176.6% of the controls) even though the total NiR mRNA of the transgenic plants varied by a factor of more than 10 times. This suggests that post-transcriptional regulation is active in NiR gene expression, which is consistent with previous results (Crété et al., 1997). A positive correlation, however, was obtained for the total NiR mRNA and total NiR protein contents (r = 0.75).

Another positive correlation existed between the total NiR protein content and NiRA (r = 0.71). The NiRA of the transgenic plants ranged from 82% to 181% of the values for the wild-type controls. A Dunnett's test for two samples of different sizes showed that four of the transgenic lines (121, 10, 117, and 693) had significantly higher NiRA than the controls (P < 0.01). Except for line 117, all had high NiR protein contents. Based on quantification of the NiR protein spots on the two-dimensional gels (Fig. 3), the contribution of the transgene in the total NiR proteins was estimated to be about 50% (see above). It is conceivable that the transgene may make a similar contribution to the observed NiRA in line 121. Further study is needed to address whether this estimation is applicable to other transgenic lines.

A third positive correlation was found between NiRA and NO2-RN (r = 0.65). The NO2-RN of the transgenic plants was 78% to 142% the values for the controls. A similar Dunnett's test as described above showed that except for 117, the lines (121, 10, and 693) had higher NO2-RN values than the controls (P < 0.01). Each of the three had one to two copies of spinach NiR cDNA per haploid genome.

Four lines bearing low copy number of the transgene (lines 693, 10, 121, and 147) had high levels in four parameters; total NiR mRNA content, total NiR protein content, NiRA (except for 147), and NO2-RN (except for 147). As described above, NiRA and NO2-RN values of the three lines 693, 10, and 121 were statistically significant over the wild-type control. It should also be note that all of these three lines are homozygous in the transgene, as described above. Although the reason(s) why line 147 having a high NiR protein content showed a low NiRA and NO2-RN values is not clear, it is likely that homozygous transgenic plants bearing low copy number of NiR transgene have a high level of NiR enzyme activity and high ability to assimilate NO2. Lines 116 and 117 are somewhat unique because both appeared to have multiple copies of the transgene, but had increased levels of total NiR mRNA, total NiR protein, NiRA, and NO2-RN, although their NO2-RN values were statistically not significant over the wild-type control. Line 111 is also unique because although it is not low in the copy in the transgene or high in the level of total NiR mRNA, it had increased levels of NiRA and NO2-RN (but statistically not significant). Line 146 had a high NiR protein content, but had low NiRA and NO2-RN values. Taken together, in addition to the copy number of the transgene and homozygosity of the transgene locus, other factors also control NiRA and thereby the ability of plants to assimilate NO2.

The flux control coefficient, a measure of the effect of change in a single enzyme activity on the flux (Kacser and Porteous, 1987; Stitt and Sonnewald, 1995), of NiR for NO2 assimilation, estimated as reported elsewhere (Runquist and Kruger, 1999) from the data for the 12 lines (Table I) was about 0.4. We presume that the conversion of nitrite ions to ammonia is a controlling step in the NO2 assimilation pathway.

To determine whether this is so we analyzed the assimilation of NO2 in a transgenic tobacco line (clone 271) in which NiR antisense mRNA is expressed, NiRA therefore being greatly reduced (Vaucheret et al., 1992) (see “Materials and Methods”). Results are shown in Table III. The NiRA of the transgenic tobacco leaf was 3.5% and the corresponding NO2-RN value was 62.1% that of the wild-type control. The estimated flux control coefficient of NiR was 0.4, a value very close to that obtained with the NiR sense transformants as described above.

Table III.

NiRA and NO2-RN in transgenic (clone 271) and wild-type tobacco plant leaves fumigated with 4 μL L−1 15N-labeled NO2 for 8 h

| NiRA | NO2−-RN | |

|---|---|---|

| μmol NO2− h−1 g−1 fresh wt | ||

| Wild type | 102 ± 7 | 0.63 ± 0.07 |

| 271 | 3.6 ± 2.4 | 0.39 ± 0.05 |

Values are mean ± sd of three independent experiments. One experiment consisted of a sample prepared from a 10-week-old plant of transgenic or wild-type tobacco.

Using particle bombardment we produced transgenic Arabidopsis plants bearing chimeric tobacco NR cDNA (Vincentz and Caboche, 1991) and plants bearing chimeric cDNAs for the GSs (GS1 and GS2) from Arabidopsis (M. Takahashi, Y. Sasaki, S. Ida, and H. Morikawa, unpublished data). All these cDNAs were under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter and NOS terminator. GS1 and GS2 cDNAs had a sense or antisense orientation in their respective expression vectors. Ten transgenic plant lines were analyzed for enzyme activity by the NR method of Wray and Fido (1990) and 25 were analyzed by the GS transferase assay (Rhodes et al., 1975). NR transformants had NR activity that was, at the most, about twice that of the non-transformed control. Similar results were obtained for the GS transformants. These findings are very similar to those for the NiR transformants given earlier (Table I). NO2-RN values were determined for the NR and GS transformants, as described above. No significant increase in the ability to assimilate NO2 was found for these transformants; the percentage of NO2-RN of the non-transformed control (mean of three plants ± sd) at the most was 111.8 ± 6.0 for the NR- and 99.0 ± 5.8 for the GS transformants. Based on the analysis of five NR- and eight GS-transformants, the respective flux control coefficients of NR and GS for NO2 assimilation were −0.01 and −0.1. These values are much smaller than those for NiR, another indication that among the genes for primary nitrogen metabolism, NiR controls the assimilation of NO2 by plants.

DISCUSSION

Plants convert the nitrogen of NO2 taken from the atmosphere to organic nitrogen (Hill, 1971; Zeevaart, 1976; Yoneyama and Sasakawa, 1979a; Kaji et al., 1980; Rowland et al., 1985; Wellburn, 1990; Morikawa et al., 1998; Ramge et al., 1993). The function of acting as a sink for this air pollutant is very important. Molecular physiological studies on the controlling steps in the NO2 assimilation pathway of plants are required to improve the ability of plants to incorporate NO2. The primary nitrate assimilation pathway is considered to have a key role in the assimilation of NO2 (Zeevaart, 1976; Yoneyama and Sasakawa, 1979a; Kaji et al., 1980; Rowland et al., 1985; Wellburn, 1990; Morikawa et al., 1998; Ramge et al., 1993). We, therefore, produced transgenic plants that bear chimeric expression vectors for NR, NiR, and GS cDNA and analyzed gene expression and NO2 assimilation in them. Of these three genes, NiR is the controlling gene in NO2 assimilation for the following reasons.

In transgenic Arabidopsis plants bearing chimeric spinach NiR cDNA, four parameters, total NiR mRNA content, total NiR protein content, NiRA, and NO2-RN, were positively correlated. An increase in NiR gene transcription therefore increases NO2 assimilation.

Of the 12 NiR-transformant lines studied, four had significantly higher NiRA than the wild-type control (P < 0.01), and three had significantly higher NO2-RN than that control (P < 0.01). Each of the latter three had one to two copies of spinach NiR cDNA per haploid genome. Two lines had 140% NO2-RN, higher than the control value. NR transformants had NR activity that was, at most, about twice that of the non-transformed control. Similar results were obtained with the GS transformants. The NR and GS transformants did not show a significant increase in NO2-RN.

The flux control coefficient of NiR for NO2 assimilation was estimated as about 0.4, based on analyses of the NiR sense and antisense transformants. Estimations based on the results for the transgenic plants gave NR and GS flux control coefficients of −0.01 and −0.1.

Elsewhere, we showed that among the 217 taxa of naturally occurring plants, there is more than a 600-fold variation in the ability to assimilate NO2 (Morikawa et al., 1998). The molecular biological causes of this variation, however, have yet to be determined. Species that show the highest assimilation may have genes for the efficient incorporation of NO2 and/or for metabolizing it in such physiological processes as stomatal conductance, cell wall and membrane transport, or nitrogen and carbon metabolite sensing in their primary and secondary metabolisms. We are currently investigating which regulatory genes (“NO2-philic genes”) are responsible for high NO2 assimilation using differential analysis of genes of species with the highest and lowest abilities. The availability of roadside trees transformed with such genes and enriched with the NiR gene will be central to improving the ability of roadside vegetation in developed and developing countries to clean up air pollution in situ.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of the NiR cDNA Expression Vector

The chimeric gene construct pCIB400 (Back et al., 1988) that carries the expression cassette of spinach (Spinacia oleracea) NiR cDNA was a gift from Dr. S. Rothstein (University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada). The 2.0-kb EcoRI fragment bearing spinach NiR cDNA was excised from pCIB400 and was ligated into the deletion plasmid derived from pBI221 in which the 1.9-kb SstI/BamHI fragment of the β-glucuronidase gene had been deleted and end-filled to produce plasmid pSNIR. To obtain plasmid pCaMVH, the 1.0-kb BamHI fragment carrying the neomycin phosphotransferase gene in plasmid pCaMVNEO (Fromm et al., 1986) was replaced by a 1.3-kb BamHI fragment that had the hygromycin phosphotransferase (hpt) gene excised from pCH (Goto et al., 1993). The 1.8-kb HindIII fragment of the hpt expression cassette was excised from plasmid pCaMVH, end-filled, and ligated into the filled SphI sites of pSNIR to produce plasmid pSNIRH (Fig. 1).

Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants

Root sections of Arabidopsis ecotype C24 were bombarded with pSNIRH by means of a pneumatic particle gun device. Transformed shoots were selected for hygromycin resistance as reported elsewhere (Takahashi and Morikawa, 1996). Shoots that developed from independent hygromycin-resistant calli and that had a band at 352 bp in the PCR with primers specific to spinach NiR cDNA (see below) were transferred to rock fiber cubes (Nittoboseki Co., Tokyo) and were allowed to mature (T0 plants) and set seeds (T1 seeds).

Seeds of the progenies of the transgenic Arabidopsis plants were sown in vermiculite and perlite (1:1, v/v) in plastic pots and grown at 22°C for 5 to 6 weeks under continuous fluorescent light (70 μmol m−2 s−1) and 70% humidity in a growth chamber (model ER-20-A; Nippon Medical and Chemical Instruments, Osaka). Plants were irrigated every 4 d with a one-half-strength solution of the inorganic salts used in Murashige-Skoog medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) containing 10.3 mm NH4NO3 and 9.4 mm KNO3 (Cheng et al., 1991). A tiny piece of a leaf was taken from plants of each transgenic line and was analyzed by a PCR (Takahashi and Morikawa, 1996) with primers that define a 352-bp fragment in the 5′ region of spinach NiR cDNA. The primer sequences used in the analysis of spinach NiR cDNA were 5′-AGCCGAGAGTGGAGGAGAGA-3′ and 5′-TACATCCGCACATCCATCTTTTCC-3′, which define a 352-bp fragment in the 5′ region of this cDNA (Back et al., 1988). The 5- to 6-week-old plants that showed this band were used for further analyses.

Transgenic Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum cv Xanthi XHFD8) Plants

Seeds of wild-type plants (provided by Dr. Michel Caboch, Laboratoire de Biologie Cellulaire, Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, Versailles, France) and transgenic plant clone 271, which expressed the NiR antisense mRNA from tobacco under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter, which lacks NiRA (Vaucheret et al., 1992), were surface sterilized and sown in vitro on B-medium adjusted to pH 5.6, which contained 20 mm KNO3 as the sole nitrogen source (Vaucheret et al., 1992). Two weeks after sowing, plants were transferred to B-medium containing 10 mm ammonium succinate as the sole nitrogen source and were grown for 4 weeks. After transfer to soil in a growth chamber and growth at 22°C and 70% humidity for 4 weeks under continuous fluorescent light (100 μmol m−2 s−1) in B-medium containing 10 mm ammonium succinate as the sole nitrogen source, the plants were analyzed for their NiRA and ability to assimilate NO2. For determination of NiRA, a sample of crude enzyme extract was prepared from the youngest fully expanded leaf (500 mg) taken from the 10-week-old plant. For determination of NO2-RN, a sample powder was prepared from the youngest and second youngest fully expanded leaves (total of about 1 g) taken from the 10-week-old plants before and after fumigation was used.

Southern Hybridization Analysis

Total DNAs from the whole shoots of a 5- to 6-week-old plant (approximately 100 mg) of transgenic line or wild-type control plant were isolated according to Murray and Thompson (1980) as modified by Rogers and Bendich (1985). The isolated DNA (2 μg) was digested with EcoRI/PstI (which produces a 1.8-kb fragment of the spinach NiR cDNA from pSNIRH), SacI (which has a unique site in the NiR cDNA of pSNIRH), SalI (which has no site in pSNIRH), or KasI/ScaI (which produces a 3.1-kb fragment of the spinach NiR cDNA expression cassette). Digests were electrophoresed in a 1% (w/v) agarose gel and were then transferred to a Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) and hybridized at 65°C with a gene probe labeled with [α-32P]dCTP and a T7QuickPrime Kit (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) in a solution (Sambrook et al., 1989) containing 5× sodium chloride/sodium phosphate/EDTA, 0.5% [w/v] SDS, 200 mg L−1 denatured salmon sperm DNA, and 5× Denhardt's solution (50× Denhardt's solution containing 1% [w/v] Ficoll, 1% [w/v] polyvinylpyrrolidone [PVP], and 1% [w/v] bovine serum albumin). The 1.8-kb fragment of spinach NiR cDNA excised from pSNIRH by EcoRI/PstI digestion was the gene probe. Final washes were done at 65°C in 0.5× sodium chloride/sodium phosphate/EDTA and 0.1% (w/v) SDS. Hybridization signals were made visible by autoradiography with an intensifying screen at −80°C for 1 to 2 d.

Total RNA and Reverse Transcription

Total RNAs from the whole shoots of a 5- to 6-week-old plant (approximately 100 mg) of transgenic line or those of wild-type control plants were extracted according to Verwoerd et al. (1989). Reverse transcription of the total RNA was done with oligo-dT as the primer: Total Arabidopsis RNA (1 μg) was mixed with the oligo-dT, incubated at 70°C for 10 min, then cooled on the ice, after which 10 mm dithiothreitol, 0.5 m dNTPs, RT buffer (Gibco-BRL, Cleveland), and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Gibco-BRL) were added. This reaction mixture (20 μL) first was incubated at 42°C for 50 min and then at 70°C for 15 min. After being cooled, RNase H was added, and the mixture incubated at 37°C for 20 min. This RT reaction mixture was used for RT-PCR analysis.

RT-PCR Analysis of Spinach, Arabidopsis, and Total NiR mRNAs

For the analysis of mRNAs of transgene spinach NiR and endogenous Arabidopsis NiR genes, the PCR mixture contained 20 μm dNTPs, PCR buffer (Takara Shuzo, Shiga, Japan), rTaq (Takara Shuzo), the primers, and 0.5 μL of the RT reaction mixture for a total volume of 20 μL. This mixture was heated to 95°C for 3 min, amplified for 30 cycles at 95°C for 1 min, then at 63°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 2 min. The primer sequences were 5′-AGCCGAGAGTGGAGGAGAGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TACATCCGCACATCCATCTTTTCC-3′ (reverse) for amplification of the NiR cDNA from the introduced spinach NiR cDNA (Back et al., 1988), 5′-TGCTTGTGGGAGGATTCTTTAGTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTGGCATTCTCTTCTCTACCTCAG-3′ (reverse) for amplification of the Arabidopsis NiR cDNA (Tanaka et al., 1994), and 5′-TTCATATCCAAGGCGGTCAATGTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCATGCCTTCTCCTGTGTACCAA-3′ (reverse) for amplification of the Arabidopsis β-tubulin cDNA (Marks et al., 1987). The PCR products were electrophoresed in 1.8% (w/v) agarose gels that then were stained with ethidium bromide. The resulting bands were quantified by a Gel Documentation System (Gel Doc 2000, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and software (Quantity One, PDI, Inc., New York).

For the quantitative analysis of total (spinach + Arabidopsis) NiR mRNAs, the PCR mixture contained 20 μm dNTPs, PCR buffer (Takara Shuzo), rTaq (Takara Shuzo), the primers, 1 μL of competitors (dilution series of 2.5 × 105 to 5 × 106 copies/μL, see below), and 0.5 μL of the RT reaction mixture for a total volume of 20 μL. The competitor (1,668 bp) consisted of a partial Arabidopsis NiR genomic clones containing three (the first to third) introns (Tanaka et al., 1994) that were prepared by PCR using 500 ng of genomic DNA of Arabidopsis as the template and 0.5 pmol of primers for total NiR cDNA listed below, as described elsewhere (Takahashi and Morikawa, 1996) after which competitor DNAs were purified by the Suprec-02 column according to the manufacturer's instruction (Takara Shuzo). The mixture was then heated to 95°C for 5 min, amplified for 30 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, then at 63°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 1 min. The primers used for total NiR cDNAs were 5′-GTTAGACTCAAGTGGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-ATGCGAGTCACTTCCT-3′ (reverse). The PCR products were electrophoresed, stained with ethidium bromide, and the resulting bands were quantified as described above. Different concentrations of the competitor were tested so that total NiR mRNA contents were determined from the intersection of curves depicting the levels of product from the competitor and levels of product from the target cDNAs.

Protein Extraction and Western-Blot Analysis

Whole shoots from a 5- to 6-week-old plant (approximately 100 mg) of a transgenic line or wild-type control plant were frozen in liquid nitrogen and then ground in a mortar with a pestle to which 0.3 mL of extraction buffer (per 100 mg of tissue) containing 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 μm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 5 mg PVP had been added. The homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000g and 4°C for 5 min, and the resulting supernatant (protein extract) used for western-blot analysis. The protein content of the extract was measured by the method of Bradford (1976) with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

An extract sample containing 10 μg of protein was layered on a 12% (w/v) acrylamide slab gel (Laemmli, 1970) and was electrophoresed for 3 h at 35 mA. NiR bands were detected with a polyclonal antibody raised against spinach NiR (Ida, 1987) and were quantified by an enhanced chemiluminescence western-blot analysis system and a detection kit (Renaissance, NEN Life Science Products, Boston).

Two-Dimensional PAGE

Two-dimensional PAGE was done as described by Görg et al. (1985). An approximate 200 μg of extracted protein was loaded on the first-dimension gel (Immobiline Dry Plate, pH 4–7, Pharmacia Biotech). Isoelectric focusing was done horizontally with a Multiphor II apparatus (Pharmacia Biotech) for 4 h at 300 V and 18 h at 3,500 V. The isoelectric focusing gel was equilibrated for 30 min in SDS sample buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 30% (w/v) glycerol, and 1% (w/v) SDS and was then mounted on a 12% (w/v) polyacrylamide-SDS slab gel and was electrophoresed for 3 h at 35 mA. Proteins that separated in the two-dimensional gels were transferred to a membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore, Bedford, MA) by an electroblotter (Trans-Blot SD, Bio-Rad). Immunodetection was done with polyclonal antibody raised against spinach NiR (Ida, 1987), as described above.

Chloroplast Isolation

The 5- to 6-week-old Arabidopsis plants were kept in the dark for 24 h before chloroplast isolation, as described by Somerville et al. (1981). Leaves of 10 such plants (approximately 1,000 mg) of a transgenic line or wild-type control plant were used for protoplast isolation. The lower leaf epidermis was scratched on ice with a razor. The scratched leaves were floated on 0.5 m sorbitol, 10 mm MES [2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid, pH 5.5], 1 mm CaCl2, 1.6% (w/v) Macerozyme R-10 (Yakult Honsha, Tokyo), and 1.6% (w/v) Cellulase Onozuka R-10 (Yakult Honsha) in a Petri dish and shaken at 40 rpm for 1.5 h. After removal of the medium, the protoplasts on the bottom of the Petri dish were washed several times with cold washing medium containing 0.5 m sorbitol, 10 mm MES (pH 6.0), 1 mm CaCl2, and 1 mm PMSF and were then transferred to a new tube containing washing medium. After centrifugation at 100g at 4°C for 4 min, the pellet was resuspended in the cold washing medium. The protoplast suspension obtained was layered on a base of 0.42 m sorbitol, 60% (v/v) Percoll, 10 mm MES (pH 6.0), 1 mm CaCl2, and 1 mm PMSF and was then centrifuged at 100g at 4°C for 4 min. The protoplasts were collected and ruptured by resuspension in 0.3 m sorbitol, 50 mm HEPES [4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid , pH 7.5], 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm MnCl2, 2 mm EDTA, 30 mm KCl, 0.25 mm KH2PO4, and 1 mm PMSF. The chloroplasts released were recovered by centrifugation at 270g for 35 s at 4°C and were ruptured by resuspension in 50 mm phosphate buffer, 1 mm EDTA, 0.07% (w/v) 2-mercaptoethanol, and 1 mm PMSF. This ruptured chloroplast preparation, which contained 10 μg of chlorophyll as determined by the method of Mackinney (1941), was layered on a 12% (w/v) polyacrylamide-SDS gel and electrophoresed as described above. The intact leaf homogenate (see below) was similarly analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The gels were silver-stained with a detection kit (Daiichi Pure Chemicals, Tokyo). RBCS band intensities in the chloroplast and intact leaf gels were quantified as described above. The chloroplast yield (intensity of RBCS band of chloroplast fraction/intensity of RBCS band of intact leaf) was estimated from these two values. The chloroplast and intact leaf NiRAs were measured as described below, and the NiRA in the chloroplast fraction (NiRA in isolated chloroplasts/chloroplast yield) was calculated.

NiR Enzyme Activity Analysis

Whole shoots of a 5- to 6-week-old plant (approximately 100 mg) of transgenic line or wild-type control plant were frozen in liquid nitrogen then ground in a mortar with a pestle. The powdered tissues were added to 0.3 mL of extraction buffer (per 100 mg of tissue) containing 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 μm PMSF, and 5 mg PVP and were then homogenized. The homogenate was centrifuged and the supernatant (crude enzyme solution) was used for the NiRA analysis. In an alternate manner, the chloroplasts were ruptured and centrifuged, as described above, and the supernatant was used for the NiRA analysis.

NiRA was assayed as reported by Wray and Fido (1990), with modification, to measure the decrease of nitrite ion in the assay mixture. A 45-μL sample of the crude enzyme solution was transferred to a 1.5-mL centrifuge tube, and 195 μL of assay solution containing 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 1 mm NaNO2, and 1 mm methyl viologen was added. The reaction was started by the addition of 60 μL of 57.4 mm Na2S2O4 in 290 mm NaHCO3 (final Na2S2O4 concentration in the assay solution was 11.5 mm), and the reaction was run for 5 min at 30°C. A 20-μL sample was transferred to a new tube containing 480 μL of water, and the whole was vigorously mixed to stop the reaction, after which 500 μL of 1% (w/v) sulfanilamide in 3 n HCl and 500 μL of 0.02% (w/v) N-1-naphthylethylenediameine dihydrochloride was added. The absorbance of this mixture at 540 nm was measured.

NO2 Assimilation Analysis

The 5- to 6-week-old plants of a transgenic line or wild-type control plant, grown as described above, were fumigated with 15N-labeled NO2 (4.0 ± 0.1 μL L−1, 51.9 atom percentage of 15N) in a fumigation chamber (model NC1000-SC, Nippon Medical and Chemical Instruments) for 8 h during the day (9 am–5 pm) in light (70 μmol m−2 s−1). The chamber was maintained at 22.0°C ± 0.3°C, with a relative humidity of 70% ± 4% and an atmospheric level CO2 concentration (0.03%–0.04%), as described elsewhere (Morikawa et al., 1998). Whole shoots were harvested from the 15NO2-fumigated plants, washed with distilled water, lyophilized for 12 h after which they were ground into fine powder in a mortar with a pestle, and the powder digested by the Kjeldahl method. (A sample for the NO2 assimilation analysis experiment was prepared from whole shoots harvested from one fumigated plant of transgenic line or wild-type one.) Preparation of the reduced nitrogen fraction was essentially as described elsewhere (Morikawa et al., 1998), except that the reducing agents (CuSO4 and K2SO4) were omitted from the digestion mixture. The 15N in the reduced nitrogen fraction was measured with a mass spectrometer (Delta C; Finnigan MAT, Bremen, Germany) connected directly to an elemental analyzer (EA/NA; Fisons Instrument, Milano, Italy) to determine the amount of NO2-RN in the fumigated leaf sample.

Statistical Analysis

All results for Arabidopsis are, except for Table II, reported in the form of means ± sd of at least two independent experiments. Each experiment consisted of the result of the whole shoots isolated from a 5- to 6-week-old Arabidopsis plant (approximately 100 mg) of transgenic line or wild-type control plant, except that in chloroplasts isolation experiment (Table II), 10 identical plants were used. For results for tobacco in Table III, details are described in “Materials and Methods.” A linear regression to calculate the correlation coefficient (r) and Dunnett's test for two samples of different sizes were made using Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Significant differences over the control non-transformed wild-type plants were estimated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Junko Uchiyama and Orie Mori for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the program Research for the Future from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (no. JSPS–RFTF96L00604) and by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas (no. 05266213) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sports, Japan. We also gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Naito Foundation and Electric Technology Research Foundation of Chugoku.

LITERATURE CITED

- Back E, Burkhart W, Moyer M, Privalle L, Rothstein S. Isolation of cDNA clones coding for spinach nitrite reductase: complete sequence and nitrate induction. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;212:20–26. doi: 10.1007/BF00322440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C-L, Acedo GN, Dewdney J, Goodman HM, Conkling MA. Differential expression of the two Arabidopsis nitrate reductase genes. Plant Physiol. 1991;96:275–279. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.1.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crété P, Caboche M, Meyer C. Nitrite reductase expression is regulated at the post-transcriptional level by the nitrogen source in Nicotiana plumbaginifolia and Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1997;11:625–634. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.11040625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncanson E, Gilkes AF, Kirk DW, Sherman A, Wray JL. nir1, a conditional-lethal mutation in barley causing a defect in nitrite reduction. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;236:275–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00277123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friemann A, Brinkmann K, Hachtel W. Sequence of a cDNA encoding nitrite reductase from the tree Betula pendula and identification of conserved protein regions. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;231:411–416. doi: 10.1007/BF00292710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromm ME, Taylor LP, Walbot V. Stable transformation of maize after gene transfer by electroporation. Nature. 1986;319:791–793. doi: 10.1038/319791a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Görg A, Postel W, Günther S, Weser J. Improved horizontal two-dimensional electrophoresis with hybrid isoelectric focusing in immobilized pH gradients in the first dimension and laying-on transfer to the second dimension. Electrophoresis. 1985;6:599–604. [Google Scholar]

- Goto F, Toki S, Uchimiya H. Inheritance of a cotransferred foreign gene in the progenies of transgenic rice plants. Transgenic Res. 1993;2:300–305. [Google Scholar]

- Hill AC. Vegetation: a sink for atmospheric pollutants. J Air Pollut Contr Assoc. 1971;21:341–346. doi: 10.1080/00022470.1971.10469535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ida S. Immunological comparisons of ferredoxin-nitrite reductases from higher plants. Plant Sci. 1987;49:111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ida S, Mikami B. Spinach ferredoxin-nitrite reductase: a purification procedure and characterization of chemical properties. Biochim Biophysica Acta. 1986;871:167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Kacser H, Porteous JW. Control of metabolism: what do we have to measure? Trends Biochem Sci. 1987;12:5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kaji M, Yoneyama T, Totsuka T, Iwaki H. Absorption of atmospheric NO2 by plants and soils: VI. Transformation of NO2 absorbed in the leaves and transfer of the nitrogen through the plants. Res Rep Natl Inst Environ Stud. 1980;11:51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberger J, Lepingle A, Caboche M, Vaucheret H. Cloning and expression of distinct nitrite reductases in tobacco leaves and roots. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;236:203–208. doi: 10.1007/BF00277113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Science. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahners K, Kramer V, Back E, Privalle L, Rothstein S. Molecular cloning of complementary DNA encoding maize nitrite reductase. Plant Physiol. 1988;88:741–746. doi: 10.1104/pp.88.3.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea PJ. Nitrogen metabolism. In: Lea PJ, Leegood RC, editors. Plant Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 1993. pp. 155–180. [Google Scholar]

- Mackinney G. Absorption of light by chlorophyll solutions. J Biol Chem. 1941;140:315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Marks MD, West J, Weeks DP. The relatively large beta-tubulin gene family of Arabidopsis contains a member with an unusual transcribed 5′ non-coding sequence. Plant Mol Biol. 1987;10:91–104. doi: 10.1007/BF00016147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa H, Takahashi M, Irifune K. Molecular mechanism of the metabolism of nitrogen dioxide as an alternative fertilizer in plants. In: Satoh K, Murata N, editors. Stress Responses of Photosynthetic Organisms. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1998. pp. 227–237. [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Murray AJS, Wellburn AR. Differences in nitrogen metabolism between cultivars of tomato and pepper during exposure to glasshouse atmospheres containing oxides of nitrogen. Environ Pollut. 1985;39:303–316. [Google Scholar]

- Murray MG, Thompson WF. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:4321–4325. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.19.4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramge P, Badeck F-W, Plöchl M, Kohlmaier GH. Apoplastic antioxidants as decisive elimination factors within the uptake process of nitrogen dioxide into leaf tissues. New Phytol. 1993;125:771–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1993.tb03927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes D, Rendon GA, Stewart GR. The control of glutamine synthetase level in Lemna minor L. Planta. 1975;125:201–211. doi: 10.1007/BF00385596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SO, Bendich AJ. Extraction of DNA from milligram amounts of fresh, herbarium and mummified plant tissues. Plant Mol Biol. 1985;5:69–76. doi: 10.1007/BF00020088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland A, Murray AJS, Wellburn AR. Oxides of nitrogen and their impact upon vegetation. Rev Environ Health. 1985;5:295–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland-Bamford AJ, Lea PJ, Wellburn AR. NO2 flux into leaves of nitrate reductase-deficient barley mutants and corresponding changes in nitrate reductase activity. Environ Exp Bot. 1989;29:439–444. [Google Scholar]

- Runquist M, Kruger NJ. Control of gluconeogenesis by isocitrate lyase in endosperm of germinating castor bean seedlings. Plant J. 1999;19:423–431. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Ed 2. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sander L, Jensen PE, Back LF, Stummann BM, Henningsen KW. Structure and expression of a nitrite reductase gene from bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) and promoter analysis in transgenic tobacco. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;27:165–177. doi: 10.1007/BF00019188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider K, Borchardt DC, Schafer-Pregl R, Nagl N, Glass C, Jeppsson A, Gebhardt C, Salamini F. PCR-based cloning and segregation analysis of functional gene homologues in Beta vulgaris. Mol Gen Genet. 1999;262(3):515–524. doi: 10.1007/s004380051113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazaki K, Yu S, Sakaki T, Tanaka K. Differences between spinach and kidney bean plants in terms of sensitivity to fumigation with NO2. Plant Cell Physiol. 1992;33:267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Somerville CR, Somerville SC, Ogren WL. Isolation of photosynthetically active protoplasts and chloroplasts from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Sci Lett. 1981;21:89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M, Sonnewald U. Regulation of metabolism in transgenic plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1995;46:341–368. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Morikawa H. High frequency stable transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana by particle bombardment. J Plant Res. 1996;109:331–334. [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi Y, Nihira J, Kondo N, Tezuka T. Change in nitrate-reducing activity in squash seedlings with NO2 fumigation. Plant Cell Physiol. 1985;26:1027–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Ida S, Irifune K, Oeda K, Morikawa H. Nucleotide sequence of a gene for nitrite reductase from Arabidopsis thaliana. DNA Seq. 1994;5:57–61. doi: 10.3109/10425179409039705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada Y, Aoki H, Tanaka T, Morikawa H, Ida S. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of a leaf ferredoxin-nitrite reductase cDNA of rice. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1995;59:2183–2185. doi: 10.1271/bbb.59.2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaucheret H, Kronenberger J, Lepingle A, Vilaine F, Boutin J-P, Caboche M. Inhibition of tobacco nitrite reductase activity by expression of antisense RNA. Plant J. 1992;2:559–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verwoerd TC, Dekker BM, Hoekema A. A small-scale procedure for the rapid isolation of plant RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:2362. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.6.2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincentz M, Caboche M. Constitutive expression of nitrate reductase allows normal growth and development of Nicotiana plumbaginifolia plants. EMBO J. 1991;10:1027–1035. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama T, Sasakawa H. Transformation of atmospheric NO2 absorbed in spinach leaves. Plant Cell Physiol. 1979a;20:263–266. [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama T, Sasakawa H, Ishizuka S, Totsuka T. Absorption of atmospheric NO2 by plants and soils. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 1979b;25:267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Yu S, Li L, Shimazaki K. Response of spinach and kidney bean plants to nitrogen dioxide. Environ Pollut. 1988;55:1–13. doi: 10.1016/0269-7491(88)90155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunus M, Singh N, Iqbal M. Global status of air pollution: an overview. In: Yunus M, Iqbal M, editors. Plant Response to Air Pollution. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1996. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wellburn AR. Why are atmospheric oxides of nitrogen usually phytotoxic and not alternative fertilizers? New Phytol. 1990;115:395–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1990.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellburn AR, Higginson C, Robinson D, Walmsley C. Biochemical explanations of more than additive inhibitory effects of low atmospheric levels of sulfur dioxide plus nitrogen dioxide upon plants. New Phytol. 1981;88:223–237. [Google Scholar]

- Wingsle G, Näholm T, Lundmark T, Ericsson A. Induction of nitrate reductase in needles of Scots pine seedlings by NOx and NO3−. Physiol Planta. 1987;70:399–403. [Google Scholar]

- Wray JL, Fido RJ. Nitrate reductase and nitrite reductase. In: Dey PM, Harborne JB, editors. Methods in Plant Biochemistry. Vol. 3. London: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 241–256. [Google Scholar]

- Zeevaart AJ. Induction of nitrate reductase by NO2. Acta Bot Neerl. 1974;23:345–346. [Google Scholar]

- Zeevaart AJ. Some effects of fumigating plants for short periods with NO2. Environ Pollut. 1976;11:97–108. [Google Scholar]