Abstract

Background

Hypersexuality (HS) accompanying neurological conditions remains poorly characterized despite profound psychosocial impacts.

Objective

We aimed to systematically review the literature on HS in patients with neurological disorders.

Study selection and analysis

We conducted a systematic review to identify studies that reported HS in neurological disorders. HS was defined as a condition characterized by excessive and persistent preoccupation with sexual thoughts, urges, and behaviors that cause significant distress or impairment in personal, social, or occupational functioning. Data on demographics, assessment techniques, associated elements, phenotypic manifestations, and management strategies were also extracted.

Findings

The final analysis included 79 studies on HS, encompassing 32 662 patients across 81 cohorts with neurological disorders. Parkinson's disease was the most frequently studied condition (55.6%), followed by various types of dementia (12.7%). Questionnaires were the most common assessment approach for evaluating HS, although the techniques varied substantially. Alterations in the dopaminergic pathways have emerged as contributing mechanisms based on the effects of medication cessation. However, standardized treatment protocols still need to be improved, with significant heterogeneity in documented approaches. Critical deficiencies include risks of selection bias in participant sampling, uncontrolled residual confounding factors, and lack of blinded evaluations of reported outcomes.

Conclusions and clinical implications

Despite growth in the last decade, research on HS remains limited across neurological conditions, with lingering quality and methodological standardization deficits. Key priorities include advancing assessment tools, elucidating the underlying neurobiology, and formulating management guidelines.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42017036478.

Keywords: Impulse control disorders, Sexual and gender disorders

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Hypersexuality is an understudied behavioural complication across neurological conditions, with limited characterisation of phenotypes, assessments and treatment.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This systematic integration of evidence delineates hypersexuality as a consistent phenomenon across disorders, signifying underlying neural pathway dysfunction rather than just behavioural roots.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

This investigation identifies research priorities, including optimising diagnostic techniques, elucidating neurological underpinnings and evaluating personalised management, to provide an evidence base for policymakers seeking care standards for this patient safety issue arising from risky sexual behaviours, distressing and potentially harmful situations and distressing and potentially harmful situations, leading to social isolation, stigma and potential legal consequences.

Introduction

Hypersexuality (HS) is a complex and poorly understood condition characterised by excessive sexual thoughts, urges and behaviours that can lead to significant distress and impairment in personal, social and occupational functioning.1 Despite its association with various neurological disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease (PD), Alzheimer’s disease and traumatic brain injury, the definition, diagnostic criteria and psychopathological features of HS remain a topic of ongoing debate and controversy.2–5

Pathological forms of sexual behaviour, also known as problematic or compulsive sexual behaviour, refer to sexual thoughts, urges or behaviours that are excessive, persistent and cause significant distress or impairment in personal, social or occupational functioning.6 These behaviours may include compulsive masturbation, excessive pornography use, frequent sexual encounters with multiple partners and engaging in risky or inappropriate sexual activities.7 However, despite the historical recognition and profound personal and societal implications of such disinhibited and deviant behaviours, the scientific study of abnormal sexuality secondary to neuropathology has received relatively limited attention compared with other neuropsychiatric domains.1

The inherent complexity surrounding human sexuality, spanning biological, psychological, interpersonal, sociocultural and moral dimensions, poses conceptual challenges for pathological characterisation.8 In recent decades, issues surrounding excessive, intrusive sexual drive, termed ‘HS’, have gained prominence in mainstream neuropsychiatric models.9 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) categorises conditions related to HS under the umbrella of ‘Impulse-Control Disorders Not Elsewhere Classified’, although it does not explicitly include HS as a distinct diagnosis.10 However, the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11) has recently included ‘Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder’ (CSBD) as a new diagnostic category.7

Understanding the mechanisms by which putative brain lesions or dysfunction results in sexual overactivity remains in its early stages.1 Consequently, HS categorisation schemes are heterogeneous; qualitative descriptors range from ambiguous ‘disinhibited sexuality’ to ostensibly pathologising ‘sexual addiction’ used interchangeably, and the diagnostic criteria for hypersexual disorders, even among ostensibly healthy individuals, remain disputed.11 Empirical findings on HS-related phenomena have emerged across various conditions from dementia12–15 to traumatic brain injury.16–18

At the clinical level, characterising HS manifestations is important given their profound personal consequences, such as relationship dissolution or legal prosecutions, as well as the transmission of sexually transmitted infections.5 19 The psychopathological aspects of HS involve complex interplay between emotional, cognitive and biological factors. Individuals may use sexual activity as a means of managing or escaping negative emotions such as anxiety, depression or stress, indicating a potential coping mechanism. Neurobiological studies suggest that HS may share common pathways with other addictive behaviours, including altered dopamine transmission, which plays a crucial role in the reward and pleasure systems.20 Furthermore, HS is often comorbid with other psychiatric conditions, such as mood, anxiety and substance use disorders, complicating its diagnosis and treatment.21

Despite the accelerating recognition of neuropsychiatric problems, spanning mood, psychotic, compulsive and personality disorders, as sequelae of the disorder or iatrogenic effects, HS remains a relatively overlooked domain that deserves dedicated scientific scrutiny.1 The discordance in terminology, diagnostic characteristics and prevalence rates highlights fundamental knowledge gaps surrounding sexual alterations associated with neurological dysfunction.8 22

Consequently, the current evidence on HS prevalence, associated behaviours, predictive factors and treatment outcomes remains fragmented across various neurological conditions without systematic integration.23–26 Given the significant knowledge gaps, this systematic review aimed to evaluate studies that specifically document hypersexual manifestations secondary to primary neurological disorders. Specific aims included summarising documented phenotypes and presenting symptoms, identifying demographic and medication-related variables and detailing interventions targeting these comorbid expressions.

Methodology

Data sources and searches

This systematic review adhered to systematic reviews and preferred the reporting item meta-analysis guidelines for conducting and reporting reviews.27 The authors developed the review protocol and registered it in the PROSPERO database (registration number: CRD42017036478), available at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO. Several databases were searched, including Embase (1974 to 17 August 2023), MEDLINE (1946 to 17 August 2023) and PsycINFO (1806 to 17 August 2023). The comprehensive search strategy combined terms related to HS and various neurological disorders, including PD, dementia and multiple sclerosis. Online supplemental appendix 1 provides the typical search terms.

bmjment-2024-300998supp001.pdf (23.4KB, pdf)

Definition of HS

The DSM-5 does not categorise HS or compulsive sexual behaviour as distinct diagnostic category.10 28 However, the ICD-11 introduced CSBD as a new diagnosis. CSBD is characterised by an individual’s inability to control intense and recurrent sexual impulses or urges, leading to repetitive sexual behaviours that result in significant distress or impairment across various domains of life, including personal, familial, social, educational and occupational functioning.7 An inclusive approach was employed for article selection to capture diverse manifestations of HS in the context of neurological disorders. Articles were included that used a range of terms to describe HS, such as ‘HS’, ‘compulsive sexual behavior’, ‘sexual disinhibition’, ‘inappropriate sexual behavior’ or ‘paraphilias’, provided that these behaviours were reported in association with a neurological condition. By adopting this broad approach, we sought to comprehensively examine the full spectrum of HS presentation in individuals with neurological disorders.

Eligibility criteria

This systematic review included original observational studies examining the occurrence, symptoms and treatment methods of HS in patients with neurological disorders. Several exclusion criteria were applied to ensure the quality and relevance of the included studies. Review articles, commentaries, editorials, conference abstracts and unpublished full-text articles were also excluded. Additionally, only studies published in English and those that differentiated HS from other impulse control disorders were considered. Animal studies were also excluded as the focus of the review was explicitly on HS in the context of neurological conditions.

Study screening and selection

NT and PB independently screened titles and abstracts, focusing on studies on HS prevalence, phenomenology and management of neurological disorders. Any discrepancies were resolved with JP as an adjudicator.

Data extraction and management

The full text of the selected abstracts was retrieved for further assessment by NT and PB using criteria similar to the initial screening. Data extraction for the included studies was performed between 16 September 2023 and 4 October 2023. The extracted data included publication year, study type, demographic data of participants, neurological disorders, HS evaluation tools and management options. The extracted data were stored in separate Excel sheets for each reviewer.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes assessed were (1) prevalence of HS, (2) clinical manifestations of HS and (3) ameliorating management for HS. Secondary outcomes included contributing factors and assessment tools.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias assessment for the included studies was conducted between 5 October 2023 and 12 November 2023. Both reviewers assessed the risk of bias for quantitative studies using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) quality assessment tool, which resulted in a Global Rating Score.29

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the study results. Frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables, such as HS assessment methods and diagnoses. Continuous variables, such as prevalence rates and mean ages, were reported using measures of central tendency (means, medians) and dispersion (ranges, SDs) across studies. The study periods were categorised by decade to analyse the research output over time. Given the descriptive nature of the review and the heterogeneity of study designs, meta-analytic pooling was not performed. The analysis was designed to synthesise key data, including the prevalence, manifestations, contributing factors and management approaches related to HS accompanying neurological conditions.

Results

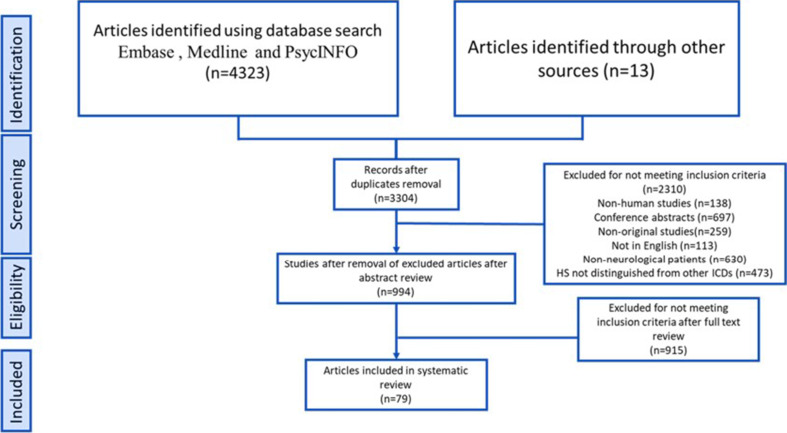

The initial search of the database yielded 4323 records. After removing 1019 duplicates, the number of records was reduced to 3304. Screening of titles and abstracts led to the exclusion of 2310 irrelevant records, categorising them based on factors such as non-human studies, conference abstracts, lack of original research, language barriers and duplication. During the full-text assessment, 915 articles were further excluded for reasons such as conference abstracts, not being available in English or full text or not focusing on the analysis of HS in neurological patients. Ultimately, 79 studies4 12–18 22 30–99 were identified that provided relevant data on the prevalence of HS (figure 1). The characteristics of the included studies are summarised for PD (online supplemental table S1), dementia (online supplemental table S2) and other neurological disorders (online supplemental table S3).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram showing literature screening and selection. HS, hypersexuality; ICDs, impulse control disorders.

bmjment-2024-300998supp002.pdf (89.5KB, pdf)

bmjment-2024-300998supp003.pdf (59.1KB, pdf)

bmjment-2024-300998supp004.pdf (56.8KB, pdf)

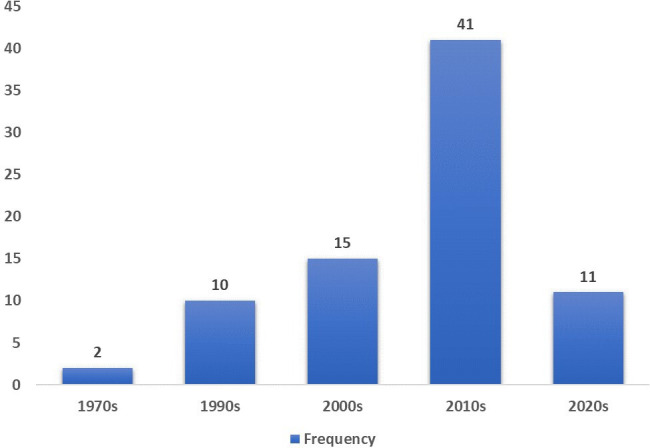

Temporal trends in HS research

Examination of temporal trends has led to a substantial increase in research attention on elucidating HS in the context of primary neurological disorders over the past 20 years (figure 2). The included studies were initially scarce, with only 12 covering three decades from the 1970s to 1990s, indicating limited early formal inquiry.14 15 18 69 79 83 86–88 94 96 99 However, publications accelerated in the 2000s (n=15 studies)13 17 22 36 39 44 56 65 70 75 76 85 89 91 93 before markedly expanding during the 2010–2020 period, which contributed more than three times as many relevant studies (n=52).12 16 31–35 37 38 40 41 43 46 48 49 51–55 59–62 64 66–68 71–74 77 78 80 81 84 92 95 97 98 With 11 articles published in the early 2020s, interest appeared to have remained strong.4 30 42 45 47 50 57 58 63 82 90

Figure 2.

Frequency of included studies investigating hypersexuality in neurological disorders by decade of publication.

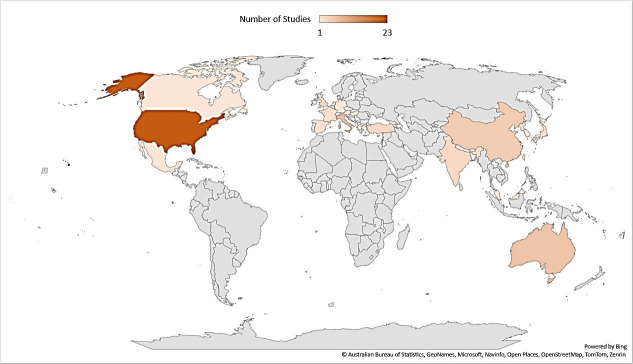

Geographical distribution of included studies

The included studies were from 24 countries (Australia, Belgium, Canada, China, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, India, Israel, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, the Netherlands, the Republic of China, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland, Taiwan, Turkey, the UK and the USA) covering North America, Europe, Asia and Oceania. The USA had the highest representation with 25 studies,13 15 22 36 46 54–56 60 63 65 69 72–74 76 80 83 85–87 91 92 97 99 followed by Italy with 7 studies,12 30 31 52 61 66 67 Australia with 6,16–18 53 82 90 China39 50 71 98 and India,57 58 64 96 the UK62 70 79 94 with 4 and France with 3.38 40 59 North American and European countries comprised the majority, with approximately 75% of studies originating from these regions (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution of countries represented across the included studies investigating hypersexuality in neurological disorders.

Study characteristics

These 79 studies produced 81 relevant analysis sets (two studies included more than one neurological disorder56 59), representing 32 662 patients. The average number of patients per study was 403.2 (range, 8–14 043), and female participants had a pooled mean of 42.1% (range, 7.3–79.2%). The pooled mean patient age was 60.9 years (range 15.1–81.1 years).

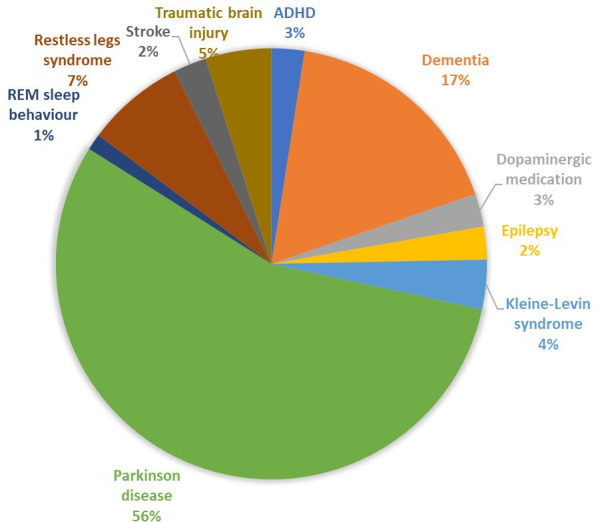

Distribution of studies by neurological disorders

The most common condition was PD (n=45, 55.6%),4 22 30–53 55–59 61–74 followed by dementia (n=14, 17.3%),12–15 54 60 75 79 83 84 88 91–93 99 restless legs syndrome (n=6, 7.4%)56 80 81 85 95 97 and traumatic brain injury (n=4, 4.9%).16–18 86 Less frequent conditions included Kleine-Levin syndrome,76 89 98 attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,77 78 epilepsy,94 96 conditions related to neuroendocrine disorders treated with dopaminergic medication,82 84 rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder90 and stroke59 87 (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Distribution of studies investigating hypersexuality stratified by the neurological disorders. ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; REM, rapid eye movement.

Duration of neurological disorders

In addition to the type of neurological disorder, the duration of these conditions in patients was an essential aspect of our analysis. ‘Duration of neurological disorder’ refers to the length of time an individual has been affected by the neurological disorder in question. Of the 79 included studies, 42 provided specific data on the mean duration of neurological disorders in their cohort.18 22 31–35 37–44 46 48–53 55–59 61–68 71 74 79 83 85 88 92 The average duration was approximately 8.26 years, with a range of variability, as indicated by an SD of 4.15 years. The shortest and longest recorded durations were 2.8 and 24 years, respectively.

Study designs and methods used to evaluate HS

Most of the included studies used a cross-sectional design (n=42, 53.16%).4 12 13 15 16 30 34 35 37 43 46 49 51–53 56–59 61 63–65 67 68 70–72 75 77–79 81–85 88 90 92 93 97 The cohort studies represented 26.58% (n=21)14 18 22 31–33 36 45 47 50 55 60 66 69 74 86 87 94 95 98 99 and case–control studies 21.25% (n=16).17 38–42 44 48 54 62 73 76 80 89 91 96

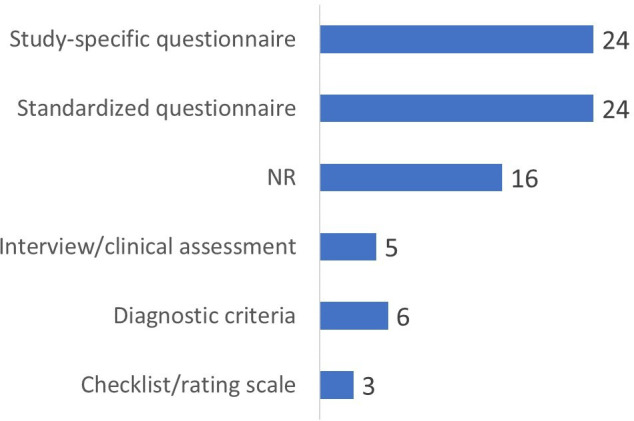

Frequency analysis was used to categorise the HS assessment methods used in the included studies (figure 5). The most common method was a study-specific questionnaire, which was used in 25 studies.12 15 16 31–33 38 39 43 49 60 65 69–72 74 76 79 81 83 85 87 93 95 Standardised questionnaires were almost as common and were used in 23 studies.4 30 34 35 40 50–53 57–59 61 63 64 68 73 77 78 82 84 90 16 studies did not specify the techniques used to evaluate HS.13 14 17 18 36 46 54 55 75 86 89 91 92 94 98 99 Diagnostic criteria were applied in six studies.22 37 48 62 80 97 Interviews and clinical assessments represented the HS categorisation method in five studies.44 56 66 96 Checklists or rating scales were less common, evident in three studies (3.85%).41 67 88 In terms of specific tools, the most frequently used standardised assessment was the Questionnaire for Impulsive-Compulsive Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease (QUIP) in its different versions. Other common standardised questionnaires include the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2, Neuropsychiatric Inventory and Sexual Compulsiveness Scale. A minority of studies have established hypersexual disorder diagnoses based on formal criteria, such as the Voon criteria. Other less common approaches include structured interviews, general behavioural checklists or symptom rating scales, or a combination of multiple evaluation methods.

Figure 5.

Distribution of approaches used across studies to evaluate hypersexual behaviour. NR, not reported.

Prevalence of HS

In the reviewed studies, the reported prevalence of HS varied widely across the neurological conditions. The mean prevalence was highest in Kleine-Levin syndrome at 40.3% (range 18–53%), reflecting its characteristic symptom triad, including HS.76 89 98 Comparatively, the prevalence was 8.6% (range 1–42.4%) in PD4 22 30–53 55–59 61–74 and 11.0% (range 1.9–17.9%) in dementias.12–15 54 60 75 79 83 84 88 91–93 99 Prevalence reached 14.3% in patients with restless legs syndrome treated with dopamine agonists (DA).95

Clinical phenomenology of HS

HS manifests in various ways in neurological disorders, including public masturbation and extramarital sexual encounters. No clear phenotypic differences were observed under any of these conditions. However, some differences have emerged between the HS associated with PD and dementia. In PD, sexual compulsivity/impulsivity predominated.22 36 39 48 62 67 In dementia, sexual disinhibition was the most frequent,12 13 54 75 83 88 92 93 99 although compulsivity also occurred.15 60

Contributing factors

The documented factors potentially contributing to HS among the 81 cases included dopaminergic medication in 34.57% (n=28),32 34 36 39 41–44 46 48 49 51 55 56 59 61 62 65 68 70 72 80–82 84 85 95 97 neurodegenerative disease in 28.40% (n=23),12–15 33 35 40 53 54 58 60 66 67 69 74 75 79 83 88 91–93 99 brain injury or other neurological conditions in 11.11% (n=9),16–18 76 86 89 94 96 98 neurodevelopmental disorder in 2.47% (n=2)77 78 and explicit demographic factors in 1.23% (n=1).22 No clear contributing factor was reported in 22.22% (n=18) of the cases exhibiting hypersexual behaviour.4 30 31 37 38 45 47 50 52 56 57 59 63 64 71 73 87 90

Ameliorating management options of HS

Among the 81 cohorts in the included 79 studies, ameliorating management options for HS was infrequently reported, with 82.72% (n=67) of cases with no explicit documentation. The most common interventions were medication adjustments (8.64%, n=7),33 36 39 46 80 81 95 psychotherapy/counselling (6.17%, n=5)13 69 86 92 96 and brain stimulation (2.47%, n=2).31 55

Risk of bias of included studies

Throughout the four decades of research, systemic quality issues persisted regarding selection bias, confounding variables and blinding (online supplemental table S4). Most studies, including older ones (eg, ref 79 96) and more recent publications (eg, ref 50 63), tend towards weak or moderate ratings in these areas, increasing the risk of bias. However, several studies (eg, ref 55 73) have demonstrated a stronger overall methodology, although limitations related to selection, confounding factors and blinding remain. Even more rigorous studies rarely show adequate control of biases in sampling, variables or appropriate blinding techniques. By contrast, several studies (eg, ref 85 85) received weak ratings across multiple assessment categories. In general, research over time has revealed a prevailing pattern of quality deficits centred on the systematic control of selection, confounders and blinding.

bmjment-2024-300998supp005.pdf (54.8KB, pdf)

Discussion

HS is a complex and not yet fully understood issue that is associated with various mental health conditions.3 This systematic review provides a comprehensive examination of HS in neurological disorders, integrating 79 studies with a pooled sample of more than 32 000 patients. HS manifests differently across neurological disorders, with sexual compulsivity and impulsivity predominating in PD,22 36 39 48 62 67 and inappropriate sexual behaviours are more common in dementia,12 13 54 75 83 88 92 93 99 indicating phenomenological distinctions.1 23 This review reveals the complexity of HS in neurological conditions, including its heterogeneous prevalence, assessment challenges and intricate management approaches. Despite these challenges, our review provides evidence for the diagnosis, assessment and treatment of HS.100 The specifics of these aspects are discussed in the following paragraphs.

HS clearly manifests as a part of various neurological disorders with varying prevalence rates.1 101 It was the highest among patients with Kleine-Levin syndrome, with an average rate of 40%.76 89 98 In contrast, the average rates were approximately 11% for PD 22 30–53 55–59 61–74 and dementia.12–15 54 60 75 79 83 84 88 91–93 99 For PD, these values align with those of a previous systematic review of 10 studies by Nakum and Cavanna, reporting an 8–11% average rate of HS in patients with PD on dopaminergic therapy.23 However, it is important to note that HS is often under-recognised and under-reported in neurological conditions owing to its sensitivity to sexual behaviours.8 36 101–103 Such heterogeneity, along with comorbidities, complicates the phenotypic presentation and analysis.

Consequently, HS still ignites debate regarding diagnosis and epidemiology.1 The DSM-5 categorises conditions related to HS under the umbrella of ‘Impulse-Control Disorders Not Elsewhere Classified’, although it does not explicitly include HS as a distinct diagnosis.7 Additionally, the conceptualisation and diagnosis of HS have been debated, both for compulsive sexual behaviours in healthy populations and for HS in neurological conditions. The sexual desire disorder model has been proposed as a potential solution.104 By offering a multidimensional framework that incorporates psychological, physiological and social factors, this model aimed to improve the understanding and treatment of abnormal sexual desires. However, the lack of clear categorisation reflects the ongoing debate and research on whether HS should be viewed as a behavioural addiction, symptom of other psychiatric disorders or a stand-alone condition.

Currently, HS assessments are primarily based on clinical observations, caregiver interviews and questionnaires.51 64 This review found that self-reported questionnaires, both study specific and standardised, such as QUIP (S or RS), were the primary methods for evaluating HS in the literature.4 30 34 35 40 50–53 57–59 61 63 64 68 73 77 78 82 84 90 On the contrary, structured diagnostic criteria and clinical interviews were rarely used despite defining manifestations and severity.22 37 48 62 80 97 This over-reliance on subjective self-reporting raises concerns about the reliability and transparency of quantifying the prevalence of HS. Social desirability and poor insight often under-report sensitive sexual symptoms. Standardised questionnaires promote consistency but remain vulnerable to response bias. Specifically, questionnaires can ascertain the prevalence of sensitive sexual behaviours due to patient reluctance to disclose sensitive sexual behaviours.23 Severity assessment also lacks a widely accepted standardised approach.28

The psychopathological aspects of HS involve complex interplay between emotional, cognitive and biological factors.2 36 82 Pathological forms of sexual behaviour, also known as problematic or compulsive sexual behaviour, refer to sexual thoughts, urges or behaviours that are excessive, persistent and cause significant distress or impairment in personal, social or occupational functioning. These behaviours may include compulsive masturbation, excessive pornography use, frequent sexual encounters with multiple partners and engaging in risky or inappropriate sexual activity. The literature on the pathological forms of sexual behaviour has documented various manifestations and associated factors. Studies have reported associations between compulsive sexual behaviour and psychiatric comorbidities, such as depression, anxiety, substance use disorders and personality disorders.82 Traumatic experiences, including childhood sexual abuse, have also been identified as potential risk factors for the development of problematic sexual behaviours.16–18 86

Treatment approaches for pathological forms of sexual behaviour have primarily focused on psychotherapeutic interventions, such as cognitive–behavioural therapy and mindfulness-based therapies.5 6 11 100 These interventions aim to help individuals develop coping strategies, regulate emotions and modify problematic thoughts and behaviours related to sexuality.13 69 86 92 96 Dopaminergic drugs, particularly DAs frequently used in Parkinson’s treatment, along with antiepileptics, cholinesterase inhibitors and tranquillisers, have been identified as pharmacological triggers. Brain stimulation31 55 and reducing or discontinuing suspected medications often lead to a decrease in symptoms, particularly in the context of PD and its treatment. The most common medication adjustments involve dose reduction, discontinuation or switching to dopaminergic medication, which is suspected to contribute to HS symptoms.33 36 39 46 80 81 95 Reduction or cessation of rotigotine and DAs has been reported as a successful intervention in patients with restless legs syndrome. For individuals with PD, several approaches have been mentioned, including reduction or cessation of dopamine replacement therapy and DAs,39 tapering of ropinirole and addition of L-dopa or entacapone,36 cessation of DAs or changing to another drug, and use of clozapine.69 Intramuscular Depo-Provera injections and counselling have been reported as successful management strategies for traumatic brain injury.86

It should be noted that HS may arise as an unintended consequence of treatment, rather than as a purely disease manifestation in some patients. As medication and disease effects are often intertwined, careful mapping of the complex pathophysiology requires concerted efforts. Multimodal strategies incorporating neuroimaging, behavioural assays that evaluate impulsivity, pharmacological challenge probes and neurochemical measurements could help elucidate the underlying mechanisms. Beyond medications, tailored non-pharmacological modalities such as cognitive–behavioural psychotherapy, group/couple therapy, caregiver coping training and environmental modifications may also prove efficacious for certain patients. The optimal management strategy for HS likely represents a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions customised according to a specific clinical profile, including the dimensions of symptoms, cognitive status and underlying neurological diagnosis.105 106

Study limitations

A fundamental constraint that permeates the literature is the inconsistency in the terminology and definitions used to characterise HS across studies. The absence of standardised nomenclature or consensus criteria for defining clinical manifestations and diagnostic features reduces the comparability between prevalence rates, reported symptoms and the proposed explanatory models. The lack of a universally accepted definition or diagnostic criteria for HS poses significant challenges for synthesising and interpreting evidence. Studies have employed a wide range of terms to describe similar or overlapping constructs, such as ‘HS’, ‘compulsive sexual behavior’, ‘sexual addiction’, ‘sexual impulsivity’ or ‘out-of-control sexual behavior’. These terms may reflect different theoretical or conceptual frameworks and diagnostic or assessment approaches. Even when studies use the same term, such as ‘HS’, there may be significant variations in how this construct is operationalised and measured. Some studies may use self-report questionnaires or diagnostic interviews, whereas others rely on clinical judgement or behavioural observations. Establishing unified definitions and diagnostic criteria through consensus building is imperative to address this limitation.

Another predominant methodological limitation is the heterogeneity of study designs, sampling techniques, sample compositions and analytical approaches. This heterogeneity limits the comparability of the studies and the generalisability of our findings. Varying case definitions, small non-random samples and inadequately controlled analyses increase the potential for bias and constrain the synthesis of findings. Moreover, many of the included studies lacked appropriate comparators, which further complicates the interpretation of the results and the assessment of the effectiveness of the interventions studied. Addressing such methodological variability through increased rigour in sampling procedures, adjustment for confounders and standardisation of case classifications are crucial for enhancing the reliability and validity of the results. The diverse array of non-standardised assessment tools used to evaluate HS further restricts consistency and measurement validity. Few psychometrically validated instruments exist to quantify symptoms, and most studies rely on unvalidated clinical impressions or idiosyncratic questionnaires. Constructing, validating and uniformly adopting standardised measures represent key imperatives for strengthening research in this emerging domain at the neuropsychiatric intersection.

We acknowledge that the inability to perform meta-regression analyses due to the heterogeneity of included studies and the limited number of studies reporting on certain outcomes is another limitation of our review. Meta-regression analyses could have provided valuable insights into potential sources of heterogeneity and the impact of specific study characteristics on observed effects. Furthermore, although we excluded studies clearly stated to be secondary analyses or performed in the same cohort as others, we determined the possibility of duplicate data in cases of larger multicentre studies, as patients could also have been included in smaller single-centre studies from the same countries. We used the EPHPP quality assessment tool instead of the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB2) assessment tool. While RoB2 is a widely accepted tool for randomised controlled trials, we chose the EPHPP tool for its applicability to a broader range of study designs. However, we acknowledge that using RoB2 could have provided a more standardised assessment of the risk of bias in the included randomised controlled trials. We also recognise that the exclusion of grey literature and non-English records may have resulted in the loss of potentially relevant studies and limited the generalisability of our findings. We acknowledge that the inclusion of non-English studies and grey literature could have increased the comprehensiveness of our review and potentially reduced the impact of resource constraints and language barriers. The omission of non-English studies may have introduced language bias and limited the global representativeness of our findings, particularly in regions where English is not the primary language of scientific publication. However, given the time and resource constraints of our research team, focusing on high-quality, peer-reviewed, English language studies was necessary to ensure the feasibility and reliability of our review. Moreover, the over-representation of Western sources in our review may have introduced geographical bias, further limiting the generalisability of our findings and potentially overlooking important cultural perspectives. Future reviews may benefit from a more inclusive approach that incorporates non-English studies to capture a more comprehensive and diverse range of evidence.

Conclusions

This first systematic review synthesises evidence from 79 studies to elucidate HS accompanying neurological disorders, an under-recognised phenomenon in the neurology-psychiatry nexus. Despite the predominant methodological limitations regarding terminology, tools and study designs, crucial insights have emerged regarding this multidimensional syndrome. These findings demonstrate that HS manifests itself in various neurological conditions with a generally low prevalence, excluding specific groups exposed to medications. However, quantifying prevalence remains challenging without the use of standardised instruments tailored for various disorders. Reported clinical manifestations range from paraphilias to compulsive behaviours, with qualitative distinctions that may arise between predominant sexual compulsivity in PD and disinhibition in dementia, partially aligned with the hypothesised differential pathologies. However, formal comparative research is lacking. Elucidating the distinctive features that accompany particular disorders can inform the development of pathogenesis models. The aetiology is likely to involve medications, surgeries and hypothalamic modulation, although definitive evidence is lacking. With regard to treatment, cessation or reduction of medications appears to be effective. However, controlled interventional studies are lacking in this regard. The development of evidence-based management guidelines should be a research priority through synergistic efforts in neurology, neurosurgery and psychiatry.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kate Brunskill, a librarian at the Queen Square Library at University College London, for helping develop the search syntax and running the searches in the databases.

Footnotes

Contributors: NT: conception, data extraction, data analysis, manuscript writing. PB: data extraction, manuscript review. JP: project organisation, review and critique, manuscript review. NT acts as a guarantor.

Funding: JP is supported in part by funding from the UK's Department of Health NIHR University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre funding scheme.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on this map does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. This map is provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Latella D, Maggio MG, Andaloro A, et al. Hypersexuality in neurological diseases: do we see only the tip of the iceberg J Integr Neurosci 2021;20:477–87. 10.31083/j.jin2002051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baird AD, Wilson SJ, Bladin PF, et al. Neurological control of human sexual behaviour: insights from lesion studies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007;78:1042–9. 10.1136/jnnp.2006.107193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rees PM, Fowler CJ, Maas CP. Sexual function in men and women with neurological disorders. Lancet 2007;369:512–25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60238-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kinateder T, Marinho D, Gruber D, et al. Sexual dysfunctions in Parkinson’s disease and their influence on partnership-data of the PRISM study. Brain Sci 2022;12:25. 10.3390/brainsci12020159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Antons S, Engel J, Briken P, et al. Treatments and interventions for compulsive sexual behavior disorder with a focus on problematic pornography use: a preregistered systematic review. J Behav Addict 2022;11:643–66. 10.1556/2006.2022.00061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Leppink EW, Grant JE. Behavioral and pharmacological treatment of compulsive sexual behavior/problematic hypersexuality. Curr Addict Rep 2016;3:406–13. 10.1007/s40429-016-0122-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kraus SW, Krueger RB, Briken P, et al. Compulsive sexual behaviour disorder in the ICD-11. World Psychiatry 2018;17:109–10. 10.1002/wps.20499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Oliveira L, Carvalho J. The link between boredom and hypersexuality: a systematic review. J Sex Med 2020;17:994–1004. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Calabrò RS, Cacciola A, Bruschetta D, et al. Neuroanatomy and function of human sexual behavior: a neglected or unknown issue? Brain Behav 2019;9:e01389. 10.1002/brb3.1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Krueger RB. Diagnosis of hypersexual or compulsive sexual behavior can be made using ICD-10 and DSM-5 despite rejection of this diagnosis by the American psychiatric association. Addiction 2016;111:2110–1. 10.1111/add.13366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Karila L, Wéry A, Weinstein A, et al. Sexual addiction or Hypersexual disorder: different terms for the same problem? A review of the literature. Curr Pharm Des 2014;20:4012–20. 10.2174/13816128113199990619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Canevelli M, Lucchini F, Garofalo C, et al. Inappropriate sexual behaviors among community-dwelling patients with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017;25:365–71. 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wiseman SV, McAuley JW, Freidenberg GR, et al. Hypersexuality in patients with dementia: possible response to cimetidine. Neurology 2000;54:2024. 10.1212/wnl.54.10.2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tsai SJ, Hwang JP, Yang CH, et al. Inappropriate sexual behaviors in dementia: a preliminary report. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1999;13:60–2. 10.1097/00002093-199903000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miller BL, Darby AL, Swartz JR, et al. Dietary changes, compulsions and sexual behavior in Frontotemporal degeneration. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1995;6:195–9. 10.1159/000106946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Simpson GK, Sabaz M, Daher M. Prevalence, clinical features, and correlates of inappropriate sexual behavior after traumatic brain injury: a multicenter study. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2013;28:202–10. 10.1097/HTR.0b013e31828dc5ae [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Simpson G, Tate R, Ferry K, et al. Social, Neuroradiologic, medical, and Neuropsychologic correlates of sexually aberrant behavior after traumatic brain injury: a controlled study. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2001;16:556–72. 10.1097/00001199-200112000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Simpson G, Blaszczynski A, Hodgkinson A. Sex offending as a Psychosocial Sequela of traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 1999;14:567–80. 10.1097/00001199-199912000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bubola Lima N, Nisida I, Sant’Ana do Amaral M, et al. 270 sexually transmitted infections in sexually compulsive women. J Sex Med 2022;19:S229–30. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2022.03.523 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stark R, Klucken T, Potenza MN, et al. A current understanding of the behavioral Neuroscience of compulsive sexual behavior disorder and problematic pornography use. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep 2018;5:218–31. 10.1007/s40473-018-0162-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jardin C, Garey L, Sharp C, et al. Acculturative stress and risky sexual behavior: the roles of sexual compulsivity and negative affect. Behav Modif 2016;40:97–119. 10.1177/0145445515613331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cooper CA, Jadidian A, Paggi M, et al. Prevalence of hypersexual behavior in Parkinson’s disease patients: not restricted to males and dopamine agonist use. Int J Gen Med 2009;2:57–61. 10.2147/ijgm.s4674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nakum S, Cavanna AE. The prevalence and clinical characteristics of Hypersexuality in patients with Parkinson’s disease following dopaminergic therapy: a systematic literature review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016;25:10–6. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Parra‐Díaz P, Chico‐García JL, Beltrán‐Corbellini Á, et al. Does the country make a difference in impulse control disorders? A systematic review. Movement Disord Clin Pract 2021;8:25–32. 10.1002/mdc3.13128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schultz K, Hook JN, Davis DE, et al. Nonparaphilic hypersexual behavior and depressive symptoms: a meta-analytic review of the literature. J Sex & MaritTherapy 2014;40:477–87. 10.1080/0092623X.2013.772551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Codling D, Shaw P, David AS. Hypersexuality in Parkinson’s disease: systematic review and report of 7 new cases. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2015;2:116–26. 10.1002/mdc3.12155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tugwell P, Tovey D. Prisma 2020. J Clin Epidem 2021;134:A5–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.04.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reid RC. How should severity be determined for the DSM-5 proposed classification of hypersexual disorder J Behav Addict 2015;4:221–5. 10.1556/2006.4.2015.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, et al. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2004;1:176–84. 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Amami P, De Santis T, Invernizzi F, et al. Impulse control behavior in GBA-mutated parkinsonian patients. J Neurol Sci 2021;421:117291. 10.1016/j.jns.2020.117291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Amami P, Dekker I, Piacentini S, et al. Impulse control Behaviours in patients with Parkinson’s disease after Subthalamic deep brain stimulation: de novo cases and 3-year follow-up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015;86:562–4. 10.1136/jnnp-2013-307214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ávila A, Cardona X, Bello J, et al. Impulse control disorders and punding in Parkinson’s disease: the need for a structured interview. Neurologia 2011;26:166–72. 10.1016/j.nrl.2010.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ávila A, Cardona X, Martín-Baranera M, et al. Impulsive and compulsive behaviors in Parkinson’s disease: a one-year follow-up study. J Neurol Sci 2011;310:197–201. 10.1016/j.jns.2011.05.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Azmin S, et al. Impulse control behaviours in a malaysian parkinson’s disease population. Neurol Asia 2016;21:137–43. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Baumann-Vogel H, Valko PO, Eisele G, et al. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease: don't set your mind at rest by self-assessments. Eur J Neurol 2015;22:603–9. 10.1111/ene.12646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bostwick JM, Hecksel KA, Stevens SR, et al. Frequency of new-onset pathologic compulsive gambling or hypersexuality after drug treatment of idiopathic Parkinson disease. Mayo Clin Proc 2009;84:310–6. 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60538-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chiang HL, et al. Are therze ethnic differences in impulsive/compulsive behaviors in Parkinson’s disease? Eur J Neurol 2012;19:494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. de Chazeron I, Llorca P-M, Chéreau-Boudet I, et al. Hypersexuality and pathological gambling in Parkinson’s disease: a cross-sectional case-control study. Mov Disord 2011;26:2127–30. 10.1002/mds.23845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fan W, Ding H, Ma J, et al. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease in a Chinese population. Neurosci Lett 2009;465:6–9. 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.06.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fantini ML, Macedo L, Zibetti M, et al. Increased risk of impulse control symptoms in Parkinson’s disease with REM sleep behaviour disorder. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015;86:174–9. 10.1136/jnnp-2014-307904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Farnikova K, Obereigneru R, Kanovsky P, et al. Comparison of personality characteristics in Parkinson disease patients with and without impulse control disorders and in healthy volunteers. Cogn Behav Neurol 2012;25:25–33. 10.1097/WNN.0b013e31824b4103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. García-Rubio MI, Otero-Cerdeira ME, Toledo-Lozano CG, et al. Analysis of impulse control disorders (Icds) and factors associated with their development in a Parkinson’s disease population. Healthcare (Basel) 2021;9:24:1263. 10.3390/healthcare9101263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gescheidt T, Losada VILY, Menšíková K, et al. Impulse control disorders in patients with young-onset Parkinson’s disease: a cross-sectional study seeking associated factors. Basal Ganglia 2016;6:197–205. 10.1016/j.baga.2016.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Giladi N, Weitzman N, Schreiber S, et al. New onset heightened interest or drive for gambling, shopping, eating or sexual activity in patients with Parkinson’s disease: the role of dopamine agonist treatment and age at motor symptoms onset. J Psychopharmacol 2007;21:501–6. 10.1177/0269881106073109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gunduz A, Çiftçi T, Erbil AC, et al. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease: a retrospective analysis of 1824 patients in a 12-year period. Neurol Sci 2024;45:171–5. 10.1007/s10072-023-07006-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hassan A, Bower JH, Kumar N, et al. Dopamine agonist-triggered pathological behaviors: surveillance in the PD clinic reveals high frequencies. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2011;17:260–4. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kapsomenakis A, Kasselimis D, Vaniotis E, et al. Frequency of impulsive-compulsive behavior and associated psychological factors in Parkinson’s disease: lack of control or too much of it. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023;59:11. 10.3390/medicina59111942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kenangil G, Ozekmekçi S, Sohtaoglu M, et al. Compulsive behaviors in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurologist 2010;16:192–5. 10.1097/NRL.0b013e31819f952b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lee J-Y, Kim J-M, Kim JW, et al. Association between the dose of dopaminergic medication and the behavioral disturbances in Parkinson disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2010;16:202–7. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2009.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Liang K, Li X, Ma J, et al. Predictors of dopamine dysregulation syndrome in patients with early Parkinson’s disease. Neurol Sci 2023;44:4333–42. 10.1007/s10072-023-06956-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lim S-Y, Tan ZK, Ngam PI, et al. Impulsive-compulsive behaviors are common in Asian Parkinson’s disease patients: assessment using the QUIP. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2011;17:761–4. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lo Monaco MR, Petracca M, Weintraub D, et al. Prevalence of impulsive-compulsive symptoms in elderly Parkinson’s disease patients: a case-control study. J Clin Psychiatry 2018;79:17m11612. 10.4088/JCP.17m11612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Maréchal E, Denoiseux B, Thys E, et al. Impulsive-compulsive behaviours in Belgian-Flemish Parkinson’s disease patients: a questionnaire-based study. Parkinsons Dis 2019;2019:7832487. 10.1155/2019/7832487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mendez MF, Shapira JS. “Kissing or "osculation" in frontotemporal dementia”. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2014;26:258–61. 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13060139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Merola A, Romagnolo A, Rizzi L, et al. Impulse control behaviors and subthalamic deep brain stimulation in Parkinson disease. J Neurol 2017;264:40–8. 10.1007/s00415-016-8314-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ondo WG, Lai D. Predictors of Impulsivity and reward seeking behavior with dopamine agonists. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2008;14:28–32. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Paul BS, Aggarwal S, Paul G, et al. Impulse-control disorders and restless leg syndrome in Parkinson’s disease: association or coexistence. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2023;26:161–6. 10.4103/aian.aian_940_22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Paul BS, Singh G, Bansal N, et al. Gender differences in impulse control disorders and related behaviors in patients with Parkinson’s disease and its impact on quality of life. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2020;23:632–7. 10.4103/aian.AIAN_47_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Perez-Lloret S, Rey MV, Fabre N, et al. Prevalence and pharmacological factors associated with impulse-control disorder symptoms in patients with Parkinson disease. Clin Neuropharmacol 2012;35:261–5. 10.1097/WNF.0b013e31826e6e6d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Perry DC, Sturm VE, Seeley WW, et al. Anatomical correlates of reward-seeking behaviours in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain 2014;137:1621–6. 10.1093/brain/awu075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Poletti M, Logi C, Lucetti C, et al. A single-center, cross-sectional prevalence study of impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease: association with dopaminergic drugs. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2013;33:691–4. 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3182979830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Politis M, Loane C, Wu K, et al. Neural response to visual sexual cues in dopamine treatment-linked hypersexuality in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2013;136:400–11. 10.1093/brain/aws326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Scott BM, Eisinger RS, Sankar R, et al. Online vs face-to-face administration of impulse control disorder questionnaires in Parkinson disease: does method matter Neurol Clin Pract 2022;12:e93–7. 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000200074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sharma A, Goyal V, Behari M, et al. Impulse control disorders and related behaviours (ICD-RBS) in Parkinson’s disease patients: assessment using "questionnaire for impulsive-compulsive disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2015;18:49–59. 10.4103/0972-2327.144311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Singh A, Kandimala G, Dewey RB, et al. Risk factors for pathologic gambling and other compulsions among Parkinson’s disease patients taking dopamine agonists. J Clin Neurosci 2007;14:1178–81. 10.1016/j.jocn.2007.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Solla P, Cannas A, Floris GL, et al. Behavioral, neuropsychiatric and cognitive disorders in Parkinson’s disease patients with and without motor complications. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2011;35:1009–13. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Solla P, Cannas A, Ibba FC, et al. Gender differences in motor and non-motor symptoms among Sardinian patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci 2012;323:33–9. 10.1016/j.jns.2012.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Tanaka K, Wada-Isoe K, Nakashita S, et al. Impulsive compulsive behaviors in Japanese Parkinson’s disease patients and utility of the Japanese version of the questionnaire for impulsive-compulsive disorders in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci 2013;331:76–80. 10.1016/j.jns.2013.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Trosch RM, Friedman JH, Lannon MC, et al. Clozapine use in Parkinson’s disease: a retrospective analysis of a large Multicentered clinical experience. Mov Disord 1998;13:377–82. 10.1002/mds.870130302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Voon V, Hassan K, Zurowski M, et al. Prevalence of repetitive and reward-seeking behaviors in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2006;67:1254–7. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000238503.20816.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wang XP, Wei M, Xiao Q. A survey of impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease patients in Shanghai area and literature review. Transl Neurodegener 2016;5:4. 10.1186/s40035-016-0051-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Weintraub D, Koester J, Potenza MN, et al. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease: a cross-sectional study of 3090 patients. Arch Neurol 2010;67:589–95. 10.1001/archneurol.2010.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Weintraub D, Papay K, Siderowf A, et al. Screening for impulse control symptoms in patients with de novo Parkinson disease: a case-control study. Neurology 2013;80:176–80. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827b915c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Zahodne LB, Susatia F, Bowers D, et al. Binge eating in Parkinson’s disease: prevalence, correlates and the contribution of deep brain stimulation. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2011;23:56–62. 10.1176/jnp.23.1.jnp56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Alagiakrishnan K, Lim D, Brahim A, et al. Sexually inappropriate behaviour in demented elderly people. Postgrad Med J 2005;81:463–6. 10.1136/pgmj.2004.028043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Arnulf I, Lin L, Gadoth N, et al. Kleine-Levin syndrome: a systematic study of 108 patients. Ann Neurol 2008;63:482–93. 10.1002/ana.21333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Bijlenga D, Vroege JA, Stammen AJM, et al. Prevalence of sexual dysfunctions and other sexual disorders in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder compared to the general population. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 2018;10:87–96. 10.1007/s12402-017-0237-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bőthe B, Koós M, Tóth-Király I, et al. Investigating the associations of adult ADHD symptoms, Hypersexuality, and problematic pornography use among men and women on a Largescale, non-clinical sample. J Sex Med 2019;16:489–99. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.01.312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Burns A, Jacoby R, Levy R. Behavioral abnormalities and psychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: preliminary findings. Int Psychogeriatr 1990;2:25–36. 10.1017/s1041610290000278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Cornelius JR, Tippmann-Peikert M, Slocumb NL, et al. Impulse control disorders with the use of dopaminergic agents in restless legs syndrome: a case-control study. Sleep 2010;33:81–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Dang D, Cunnington D, Swieca J. The emergence of devastating impulse control disorders during dopamine agonist therapy of the restless legs syndrome. Clin Neuropharmacol 2011;34:66–70. 10.1097/WNF.0b013e31820d6699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. De Sousa SMC, Baranoff J, Rushworth RL, et al. Impulse control disorders in dopamine agonist-treated hyperprolactinemia: prevalence and risk factors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020;105:01. 10.1210/clinem/dgz076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Devanand DP, Brockington CD, Moody BJ, et al. Behavioral syndromes in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr 1992;4 Suppl 2:161–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Dogansen SC, Cikrikcili U, Oruk G, et al. Dopamine agonist-induced impulse control disorders in patients with Prolactinoma: A cross-sectional multicenter study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019;104:2527–34. 10.1210/jc.2018-02202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Driver-Dunckley ED, Noble BN, Hentz JG, et al. Gambling and increased sexual desire with dopaminergic medications in restless legs syndrome. Clin Neuropharmacol 2007;30:249–55. 10.1097/wnf.0b013e31804c780e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Emory LE, Cole CM, Meyer WJ. Use of Depo-Provera to control sexual aggression in persons with traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabili 1995;10:47–58. 10.1097/00001199-199506000-00005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Hainline B, Devinsky O, Reding M. Behavioral problems in stroke rehabilitation patients: a prospective pilot study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 1992;2:131–5. 10.1016/S1052-3057(10)80221-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Hwang JP, Yang CH, Tsai SJ, et al. Behavioural disturbances in psychiatric Inpatients with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type in Taiwan. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997;12:902–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Kesler A, Gadoth N, Vainstein G, et al. Kleine Levin syndrome (KLS) in young females. Sleep 2000;23:563–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Marques A, Roquet D, Matar E, et al. Limbic Hypoconnectivity in idiopathic REM sleep behaviour disorder with impulse control disorders. J Neurol 2021;268:3371–80. 10.1007/s00415-021-10498-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Mendez MF, Chen AK, Shapira JS, et al. Acquired sociopathy and frontotemporal dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2005;20:99–104. 10.1159/000086474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Mendez MF, Shapira JS. Hypersexual behavior in frontotemporal dementia: a comparison with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Sex Behav 2013;42:501–9. 10.1007/s10508-012-0042-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Onishi J, Suzuki Y, Umegaki H, et al. Behavioral, psychological and physical symptoms in group homes for older adults with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 2006;18:75–86. 10.1017/S1041610205002917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Saunders M, Rawson M. Sexuality in male epileptics. J Neurol Sci 1970;10:577–83. 10.1016/0022-510x(70)90189-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Schreglmann SR, Gantenbein AR, Eisele G, et al. Transdermal rotigotine causes impulse control disorders in patients with restless legs syndrome. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2012;18:207–9. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Shukla GD, Srivastava ON, Katiyar BC. Sexual disturbances in temporal lobe epilepsy:a controlled study. Br J Psychiatry 1979;134:288–92. 10.1192/bjp.134.3.288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Voon V, Schoerling A, Wenzel S, et al. Frequency of impulse control behaviours associated with dopaminergic therapy in restless legs syndrome. BMC Neurol 2011;11:117. 10.1186/1471-2377-11-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Wang JY, Han F, Dong SX, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid orexin A levels and autonomic function in Kleine-Levin syndrome. Sleep 2016;39:855–60. 10.5665/sleep.5642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Zeiss AM, Davies HD, Tinklenberg JR. An observational study of sexual behavior in demented male patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1996;51:M325–9. 10.1093/gerona/51a.6.m325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Kaplan MS, Krueger RB. Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of hypersexuality. J Sex Res 2010;47:181–98. 10.1080/00224491003592863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Latella D, Maggio MG, Maresca G, et al. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review on risk factors and pathophysiology. J Neurol Sci 2019;398:101–6. 10.1016/j.jns.2019.01.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Montgomery-Graham S. Conceptualization and assessment of hypersexof hypersexual disorder: a sysual disorder: a systematic review of the literature. Sex Med Rev 2017;5:146–62. 10.1016/j.sxmr.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Grubbs JB, Hoagland KC, Lee BN, et al. Sexual addiction 25 years on: a systematic and methodological review of empirical literature and an agenda for future research. Clin Psychol Rev 2020;82:101925. 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Kingston DA, Firestone P. Problematic hypersexuality: a review of conceptualization and diagnosis. Sex Addic & Compul 2008;15:284–310. 10.1080/10720160802289249 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Torrisi M, Cacciola A, Marra A, et al. Inappropriate behaviors and Hypersexuality in individuals with dementia: an overview of a neglected issue. Geriatrics Gerontology Int 2017;17:865–74. 10.1111/ggi.12854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Marshall LE, Briken P. Assessment, diagnosis, and management of hypersexual disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2010;23:570–3. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32833d15d1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjment-2024-300998supp001.pdf (23.4KB, pdf)

bmjment-2024-300998supp002.pdf (89.5KB, pdf)

bmjment-2024-300998supp003.pdf (59.1KB, pdf)

bmjment-2024-300998supp004.pdf (56.8KB, pdf)

bmjment-2024-300998supp005.pdf (54.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.