Abstract

The EFSA Panel on Plant Health performed a pest categorisation of Diaphania indica (Lepidoptera: Crambidae), the cucumber moth for the territory of the European Union (EU), following the commodity risk assessment of Jasminum polyanthum from Uganda, in which D. indica was identified as a pest of possible concern to the European Union. D. indica is native to South Asian countries and is now distributed in tropical and subtropical areas of the Americas, Africa, Asia and Oceania. In the EU, D. indica occurs in Madeira (Portugal). It is a polyphagous pest, feeding on 16 genera in 6 plant families, primarily on plants of the Cucurbitaceae family. Important cucurbit hosts in the EU include cucumber (Cucumis sativus), melon (Cucumis melo), pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata), summer squash (Cucurbita pepo) and watermelon (Citrullus lanatus). Plants for planting, fruits and cut flowers provide potential pathways for entry into the EU. Climatic conditions and availability of host plants in southern EU countries would most probably allow this species to successfully establish and spread. Establishment could also occur in greenhouses in the northern parts of the EU. Economic impact in cultivated hosts, especially cucurbit crops is anticipated if establishment occurs. This insect is not listed in Annex II of Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/2072. Phytosanitary measures are available to reduce the likelihood of entry and further spread. D. indica meets the criteria that are within the remit of EFSA to assess for this species to be regarded as a potential Union quarantine pest.

Keywords: Crambidae, cucumber moth, lepidoptera, pest risk, plant health, plant pest, quarantine

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background and Terms of Reference as provided by the requestor

1.1.1. Background

The new Plant Health Regulation (EU) 2016/2031, on the protective measures against pests of plants, is applying from 14 December 2019. Conditions are laid down in this legislation in order for pests to qualify for listing as Union quarantine pests, protected zone quarantine pests or Union regulated non‐quarantine pests. The lists of the EU regulated pests together with the associated import or internal movement requirements of commodities are included in Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/2072. Additionally, as stipulated in the Commission Implementing Regulation 2018/2019, certain commodities are provisionally prohibited to enter in the EU (high risk plants, HRP). EFSA is performing the risk assessment of the dossiers submitted by exporting to the EU countries of the HRP commodities, as stipulated in Commission Implementing Regulation 2018/2018. Furthermore, EFSA has evaluated a number of requests from exporting to the EU countries for derogations from specific EU import requirements.

In line with the principles of the new plant health law, the European Commission with the Member States are discussing monthly the reports of the interceptions and the outbreaks of pests notified by the Member States. Notifications of an imminent danger from pests that may fulfil the conditions for inclusion in the list of the Union quarantine pest are included. Furthermore, EFSA has been performing horizon scanning of media and literature.

As a follow‐up of the above‐mentioned activities (reporting of interceptions and outbreaks, HRP, derogation requests and horizon scanning), a number of pests of concern have been identified. EFSA is requested to provide scientific opinions for these pests, in view of their potential inclusion by the risk manager in the lists of Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/2072 and the inclusion of specific import requirements for relevant host commodities, when deemed necessary by the risk manager.

1.1.2. Terms of reference

EFSA is requested, pursuant to Article 29(1) of Regulation (EC) No 178/2002, to provide scientific opinions in the field of plant health.

EFSA is requested to deliver 53 pest categorisations for the pests listed in Annex 1A, 1B, 1D and 1E (for more details see mandate M‐2021‐00027 on the Open.EFSA portal). Additionally, EFSA is requested to perform pest categorisations for the pests so far not regulated in the EU, identified as pests potentially associated with a commodity in the commodity risk assessments of the HRP dossiers (Annex 1C; for more details see mandate M‐2021‐00027 on the Open.EFSA portal). Such pest categorisations are needed in the case where there are not available risk assessments for the EU.

When the pests of Annex 1A are qualifying as potential Union quarantine pests, EFSA should proceed to phase 2 risk assessment. The opinions should address entry pathways, spread, establishment, impact and include a risk reduction options analysis.

Additionally, EFSA is requested to develop further the quantitative methodology currently followed for risk assessment, in order to have the possibility to deliver an express risk assessment methodology. Such methodological development should take into account the EFSA Plant Health Panel Guidance on quantitative pest risk assessment and the experience obtained during its implementation for the Union candidate priority pests and for the likelihood of pest freedom at entry for the commodity risk assessment of High Risk Plants.

1.2. Interpretation of the Terms of Reference

Diaphania indica is one of a number of pests relevant to Annex 1C of the Terms of Reference (ToR) to be subject to pest categorisation to determine whether it fulfils the criteria of a potential Union quarantine pest (QP) for the area of the EU excluding Ceuta, Melilla and the outermost regions of Member States referred to in Article 355(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), other than Madeira and the Azores, and so inform EU decision making as to its appropriateness for potential inclusion in the lists of pests of Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/ 2072. If a pest fulfils the criteria to be potentially listed as a Union QP, risk reduction options will be identified.

1.3. Additional information

This pest categorisation was initiated following the commodity risk assessment of Jasminum polyanthum plants for planting from Uganda performed by EFSA (EFSA PLH Panel, 2022), in which D. indica was identified as a relevant non‐regulated EU pest which could potentially enter the EU on J. polyanthum plants.

2. DATA AND METHODOLOGIES

2.1. Data

2.1.1. Information on pest status from NPPOs

In the context of the current mandate, EFSA is preparing pest categorisations for new/emerging pests that are not yet regulated in the EU. When official pest status is not available in the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO) Global Database (EPPO, online), EFSA consults the NPPOs of the relevant MSs. To obtain information on the official pest status for D. indica, EFSA has consulted the NPPO of Portugal. The results of this consultation are presented in Section 3.2.2.

2.1.2. Literature search

A literature search on D. indica was conducted at the beginning of the categorisation in the ISI Web of Science bibliographic database, using the scientific name of the pest as search term. Papers relevant for the pest categorisation were reviewed, and further references and information were obtained from experts, as well as from citations within the references and grey literature.

2.1.3. Database search

Pest information, on host(s) and distribution, was retrieved from the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO) Global Database (EPPO, online), the CABI databases and scientific literature databases as referred above in Section 2.1.1.

Data about the import of commodity types that could potentially provide a pathway for the pest to enter the EU and about the area of hosts grown in the EU were obtained from EUROSTAT (Statistical Office of the European Communities).

The Europhyt and TRACES databases were consulted for pest‐specific notifications on interceptions and outbreaks. Europhyt is a web‐based network run by the Directorate General for Health and Food Safety (DG SANTÉ) of the European Commission as a subproject of PHYSAN (Phyto‐Sanitary Controls) specifically concerned with plant health information. TRACES is the European Commission's multilingual online platform for sanitary and phytosanitary certification required for the importation of animals, animal products, food and feed of non‐animal origin and plants into the European Union, and the intra‐EU trade and EU exports of animals and certain animal products. Up until May 2020, the Europhyt database managed notifications of interceptions of plants or plant products that do not comply with EU legislation, as well as notifications of plant pests detected in the territory of the Member States and the phytosanitary measures taken to eradicate or avoid their spread. The recording of interceptions switched from Europhyt to TRACES in May 2020.

GenBank was searched to determine whether it contained any nucleotide sequences for Diaphania indica which could be used as reference material for molecular diagnosis. GenBank® (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) is a comprehensive publicly available database that as of August 2019 (release version 227) contained over 6.25 trillion base pairs from over 1.6 billion nucleotide sequences for 450,000 formally described species (Sayers et al., 2020).

2.2. Methodologies

The Panel performed the pest categorisation for D. indica, following guiding principles and steps presented in the EFSA guidance on quantitative pest risk assessment (EFSA PLH Panel, 2018), the EFSA guidance on the use of the weight of evidence approach in scientific assessments (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2017) and the International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures No. 11 (FAO, 2013).

The criteria to be considered when categorising a pest as a potential Union QP is given in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 Article 3 and Annex I, Section 1 of the Regulation. Table 1 presents the Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 pest categorisation criteria on which the Panel bases its conclusions. In judging whether a criterion is met the Panel uses its best professional judgement (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2017) by integrating a range of evidence from a variety of sources (as presented above in Section 2.1) to reach an informed conclusion as to whether or not a criterion is satisfied.

TABLE 1.

Pest categorisation criteria under evaluation, as derived from Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants (the number of the relevant sections of the pest categorisation is shown in brackets in the first column).

| Criterion of pest categorisation | Criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union quarantine pest (Article 3) |

|---|---|

| Identity of the pest (Section 3.1 ) | Is the identity of the pest clearly defined, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible? |

| Absence/presence of the pest in the EU territory (Section 3.2 ) |

Is the pest present in the EU territory? If present, is the pest in a limited part of the EU or is it scarce, irregular, isolated or present infrequently? If so, the pest is considered to be not widely distributed |

| Pest potential for entry, establishment and spread in the EU territory (Section 3.4 ) | Is the pest able to enter into, become established in, and spread within, the EU territory? If yes, briefly list the pathways for entry and spread |

| Potential for consequences in the EU territory (Section 3.5 ) | Would the pests' introduction have an economic or environmental impact on the EU territory? |

| Available measures (Section 3.6 ) | Are there measures available to prevent pest entry, establishment, spread or impacts? |

| Conclusion of pest categorisation (Section 4 ) | A statement as to whether (1) all criteria assessed by EFSA above for consideration as a potential quarantine pest were met and (2) if not, which one(s) were not met |

The Panel's conclusions are formulated respecting its remit and particularly with regard to the principle of separation between risk assessment and risk management (EFSA founding regulation (EU) No 178/2002); therefore, instead of determining whether the pest is likely to have an unacceptable impact, deemed to be a risk management decision, the Panel will present a summary of the observed impacts in the areas where the pest occurs, and make a judgement about potential likely impacts in the EU. While the Panel may quote impacts reported from areas where the pest occurs in monetary terms, the Panel will seek to express potential EU impacts in terms of yield and quality losses and not in monetary terms, in agreement with the EFSA guidance on quantitative pest risk assessment (EFSA PLH Panel, 2018). Article 3 (d) of Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 refers to unacceptable social impact as a criterion for quarantine pest status. Assessing social impact is outside the remit of the Panel.

3. PEST CATEGORISATION

3.1. Identity and biology of the pest

3.1.1. Identity and taxonomy

Is the identity of the pest clearly defined, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and/or to be transmissible?

Yes, the identity of the pest is established and Diaphania indica (Saunders) is the accepted name.

D. indica (Saunders) (Figure 1) is an insect within the order Lepidoptera, and the family Crambidae. It is commonly known as cucumber moth, melon moth, pumpkin caterpillar and cotton caterpillar (EPPO, online). D. indica was originally described as Eudioptes indica by Saunders in 1851 (CABI, online). Other synonyms are Glyphodes indica, Hedylepta indica, Margaronia indica, Palpita indica and Phacellura indica (EPPO, online).

FIGURE 1.

Diaphania indica: (A) adult; (B) larva (Source: Fera).

The EPPO code 1 (EPPO, 2019; Griessinger & Roy, 2015) for this species is: DPHNIN (EPPO, online).

3.1.2. Biology of the pest

D. indica is a multivoltine species with four development stages: egg, larva (five larval instars), pupa and adult (Hosseinzade et al., 2014; Pilania et al., 2022). Females lay their eggs singly or in groups on the lower surface of leaves, leaf buds and young stems (Barma & Jha, 2014; Ganehiarachchi, 1997), and preferably on mature leaves rather than on younger developing leaves or aged leaves (Choi et al., 2003). The average fecundity is about 270 eggs (Ganehiarachchi, 1997) with a maximum of 1053 eggs per female during its life span (Ke et al., 1988). The average adult life span was reported to be 7 days (Rahman et al., 2023). Pre‐oviposition and oviposition periods were 2 and 6–7 days long, respectively (temperature and relative humidity range 25–37°C and 50%–100%, respectively) (Pandey, 1977).

In Bangladesh, the life cycle (from eggs to adults) of the insect took about 17.5 days (Rahman et al., 2023). In laboratory experiments at 30°C, the life cycle varied from about 18 days in a Japanese stock colony, 20 days in an Iranian colony, to 23 days in an Indian one (Hosseinzade et al., 2014). In China, no adults are found earlier than July or later than November, and the peak abundance of adults occurs from August to early September (Ke et al., 1988). D. indica has a similar phenology in South Korea (Choi et al., 2003). In Bangalore district in India, it was present throughout the year indicating overlapping generations (Sharada Devi & Venkatesha, 2022). Ke et al. (1988) recorded a maximum of 4 generations per year in China while in Hainan, China, Liu (2004) predicted that D. indica could complete 12 generations per year (Everatt et al., 2015; MacLeod, 2005).

Larvae feed mainly on the leaves, but also attack flowers and fruits (Hosseinzade et al., 2014). The first two instars feed on the lower epidermis of leaves, while the later instars (third to fifth) feed on the whole leaf (Debnath et al., 2020). In Bangladesh, the larval development lasted about 12 days under field conditions (Rahman et al., 2023). In laboratory experiments at Raichur, Karnataka, India, on bitter gourd (Momordica charantia), the larval duration was 9.5 days (Nagaraju et al., 2018).

Pupation takes place within a white silky cocoon, remaining attached to leaves which were rolled by the larvae prior to pupation (Barma & Jha, 2014). The pupal duration takes about 5 days in Bangladesh (Rahman et al., 2023) and 7–9 days in Dalugama, Sri Lanka (Ganehiarachchi, 1997).

In South Korea, D. indica was reported to overwinter as pupae in the soil (Choi et al., 2003). The biology of the pest is summarised in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Important features of the life history strategy of Diaphania indica.

| Life stage | Phenology and relation to host | Other relevant information |

|---|---|---|

| Egg |

In a laboratory study in Yemen, the average egg incubation period was found to last about 6, 4, 3 and 3.5 days at 20°C, 25°C, 30°C and 35°C, respectively (Ba‐Angood, 1979) In New Zealand eggs hatch in 7–20 days whereas in Malaysia in 2–4 days (Ali et al., 2016) |

Kinjo and Arakaki (2002) found the developmental threshold temperature for egg at 13.7°C, whereas Peter and David (1992) at 12.92°C with 52.88 degree‐days required for hatching |

| Larva |

In a laboratory experiment the average larval duration was about 15, 13, 10 and 11.5 days at 20°C, 25°C, 30°C and 35°C, respectively (Ba‐Angood, 1979). In Bangladesh, the duration of 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th larval instars was found to be about 2.8, 2.6, 2.4, 2.4 and 2.2 days, respectively (Rahman et al., 2023) whereas in Raichur, Karnataka, India, on bitter gourd was about 3.0, 2.2, 2.5, 1.5 and 1.8 days, respectively (Nagaraju et al., 2018) In New Zealand larvae take 4–6 weeks to become pupae whereas in Malaysia 2–3 weeks (Ali et al., 2016) |

Kinjo and Arakaki (2002) found the developmental threshold temperature for larva at 12.0°C, whereas Peter and David (1992) at 12.85°C with 212.76 degree‐days required for larval development |

| Prepupa‐Pupa | The average pupal period in Yemen (lab experiment) was found to be about 10, 7, 5 and 6 days at 20°C, 25°C, 30°C and 35°C, respectively (Ba‐Angood, 1979). In South Korea, larvae were found to descend from hosts and enter the soil during October and burrow to between 5 and 10 cm below the soil surface where they form pupae and overwinter (Choi et al., 2003; MacLeod, 2005) | Kinjo and Arakaki (2002) found the developmental threshold temperature for pupa at 14.90°C, whereas Peter and David (1992) at 14.11°C with 107.55 degree‐days required for pupal development |

| Adult | Females laid more eggs on pumpkin (Cucurbita spp.) and bitter gourd (Momordica charantia) when compared to ride guard (Luffa acutangula) (Sharada Devi & Venkatesha, 2022) | At 25°C, the mean adult longevity of males (21.6 days) on cucumber (Cucumis sativus) was significantly longer than that of females (16.7 days) (Kinjo & Arakaki, 2002). The number of eggs laid varied for different hosts and at different seasons of year. Ke et al. (1986) found that 510 eggs per female laid on Cucurbita pepo in August and about 340 in September |

3.1.3. Host range/species affected

D. indica is a polyphagous insect species, feeding on cultivated and wild plants in 16 genera in 6 plant families namely Brassicaceae, Cucurbitaceae, Fabaceae, Malvaceae, Musaceae and Passifloraceae (EPPO, online; CABI, online). Beans (Phaseolus spp.), bitter gourd (Momordica charantia), cajan pea (Cajanus cajan), cowpea (Vigna unguiculata), cucumber (Cucumis sativus), melon (Cucumis melo), pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata), sponge cucumber (Luffa aegyptiaca), summer squash (Cucurbita pepo) and watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) are among D. indica hosts.

In a field study, Ba‐Angood (1979) found that among three cucurbit crops, D. indica preferred to lay eggs on melon (C. melo) over watermelon (C. lanatus) and cucumber (C. sativus). In field host preference experiments in Bangladesh, Rahman et al. (2023) tested three summer cucurbit species (bitter gourd, ridge gourd and snack gourd) and found that snake gourd was the most preferred host, while bitter gourd was the least preferred one. Choi et al. (2003) ranked the larvae host preference as follows: Cucumis sativus, Lagenaria siceraria, Citrullus lanatus > Cucumis melo L. var. makuwa, 2 Sicyos angulatus > Luffa aegyptiaca, 3 Gossypium arboretum. 4

A complete list of hosts is provided in Appendix A.

3.1.4. Intraspecific diversity

No intraspecific diversity has been reported for D. indica.

3.1.5. Detection and identification of the pest

Are detection and identification methods available for the pest?

Yes, visual detection is possible, and morphological and molecular identification methods are available.

Detection

Visual examination of plants is an effective way to detect D. indica larvae as soon as they start to hatch (CABI, online). D. indica pheromone lures can be used for monitoring (Choi et al., 2009; Wakamura et al., 1998). Βucket traps or Delta traps are used as trapping and monitoring tools of adult moths (Lenin, 2011).

Symptoms

Τhe main symptoms of D. indica infestation are (Everatt et al., 2015; Patel & Kulkarny, 1956; Pilania et al., 2022):

folding or binding of leaves;

skeletonisation or lace like patches of intact small leaf veins;

damage to the inner portions of flowers can prevent fruit developing;

entry of larvae into fruit and feeding on it often makes the fruit unmarketable, particularly after suffering from secondary infection by pathogens.

Identification

The identification of D. indica requires microscopic examination and verification of the presence of key morphological characteristics. Detailed morphological descriptions for all development stages, illustrations, and keys of D. indica can be found in Clarke (1986); Clavijo (1990); Everatt et al. (2015); Mondal et al. (2020) and Neunzig (1990).

D. indica is often confused with D. hyalinata to which it is similar in external appearance. D. indica can be distinguished from D. hyalinata by the lack of an expansion of the brown marking at the tornus of the forewing, which is not found in D. hyalinata. D. indica can be distinguished from some other species of Diaphania genus by the absence of a brown spot internal to the brown band along the costa in the forewings. For a confirmed identification, male or female genitalia should be examined.

Molecular diagnostic protocols for species identification such as sequences from the DNA barcode region of the mitochondrial COI gene have been suggested by Regier et al. (2012), Ashfaq et al. (2017) and Dai et al. (2018). GenBank contains gene nucleotide sequences for D. indica (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/?term=diaphania+indica).

Description

Eggs are white or whitish. They are small, usually laid in very small clumps of around 2–6 eggs and are roughly 0.7–0.95 mm long and 0.3–0.6 mm wide in D. indica.

Larva development goes through five larval instars, with mature larvae growing up to 25 mm. The young larvae are transparent and change to green or yellow‐green as they develop. Upon maturity, two white dorsal stripes can be seen to run the length of their bodies and they may have 4 very small black spots in a square just behind the head.

Pupae are 12–20 mm long and around 3–4 mm wide and are often found in a loose cocoon formed by spinning leaves together with silk. The pupae turn from white to brown as they develop.

Adults are about 13–16 mm long, with a wingspan of 24–33 mm. The wings have a white patch that is banded by brown and exhibit a purple iridescence. A well‐developed tuft of light brown hairs at the tip of abdomen is present in females, but it is vestigial in males. The tuft is formed by long scales which are carried in a pocket on each side of the seventh abdominal segment. The head, first two thoracic segments and a section near to the tuft are generally white. The antennae in males with the two first basal segments (three in females) are fully covered by brown scales (scape with dorsal side white), the rest of the segments only with dorsal side scaled (Clavijo, 1990; Everatt et al., 2015; Mondal et al., 2020).

3.2. Pest distribution

3.2.1. Pest distribution outside the EU

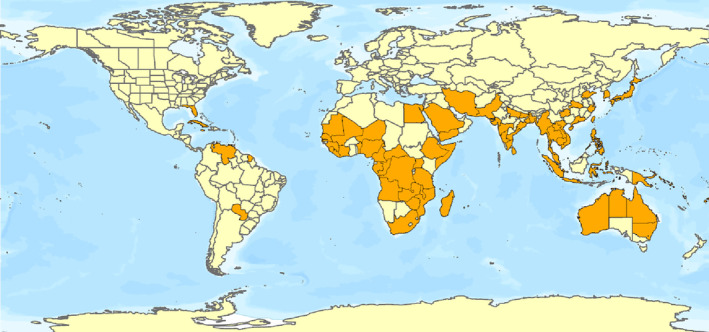

D. indica is native to south‐Asian countries (Dai et al., 2018). The present distribution of D. indica includes tropical and sub‐tropical regions in Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, Oceania and South America. It is also distributed in Florida, United States (EPPO, online) (Figure 2). In areas with cold winters such as Jiroft in Iran, Japan and South Korea, D. indica is a greenhouse pest (Hosseinzade et al., 2014; Kinjo & Arakaki, 2002; MacLeod, 2005). A record of D. indica has been reported in the UK, but it seems that it was transient, and the pest is not established in the UK (Everatt et al., 2015).

FIGURE 2.

Global distribution of Diaphania indica (data source: EPPO, online, Ashfaq et al., 2017; for details, see Appendix B). The polygons with highlighted orange colour indicate the administrative areas where D. indica is present.

3.2.2. Pest distribution in the EU

Is the pest present in the EU territory? If present, is the pest in a limited part of the EU or is it scarce, irregular, isolated or present infrequently? If so, the pest is considered to be not widely distributed.

Yes. D. indica has been recorded in the EU territory, in Madeira, Portugal.

In the EU, D. indica is known to be present only in Madeira Island in Portugal (EPPO, online; CABI, online; Aguiar & Karsholt, 2006). The Portuguese NPPO confirmed that the pest is present in Madeira for a long time with few occurrences and does not occur in Portugal mainland nor in the Azores islands. So far, no damage has been reported, and official surveys are not carried out.

3.3. Regulatory status

3.3.1. Commission Implementing Regulation 2019/2072

D. indica is not listed in Annex II of Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/2072, an implementing act of Regulation (EU) 2016/2031, or in any emergency plant health legislation.

3.3.2. Hosts or species affected that are prohibited from entering the Union from third countries

According to the Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/2072, Annex VI, introduction of D. indica hosts in the Union are not prohibited from third countries. However, soil is prohibited from third countries other than Switzerland (Table 3). According to Annex I of Regulation (EU) 2018/2019, fruits of Momordica L. originating from third countries or areas of third countries where Thrips palmi Karny is known to occur and where effective mitigation measures for that pest are lacking are considered high‐risk plants, plant products and other objects within the meaning and their introduction into the Union territory shall be prohibited pending a risk assessment. As regards fruits of Momordica charantia L., originating in Honduras, Mexico, Sri Lanka and Thailand, Momordica fruits are allowed under special requirements ((EU) 2022/853). D. indica is present in Sri Lanka and Thailand.

TABLE 3.

List of plants, plant products and other objects that are Diaphania indica hosts whose introduction into the Union from certain third countries is prohibited (Source: Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/2072, Annex VI).

| List of plants, plant products and other objects whose introduction into the Union from certain third countries is prohibited | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Description | CN code | Third country, group of third countries or specific area of third country | |

| 19. | Soil as such consisting in part of solid organic substances |

ex 2530 90 00 ex 3824 99 93 |

Third countries other than Switzerland |

3.4. Entry, establishment and spread in the EU

3.4.1. Entry

Is the pest able to enter into the EU territory? If yes, identify and list the pathways.

Diaphania indica has entered the EU territory (Madeira, Portugal). Possible pathways of entry are plants for planting, fruits, cut flowers and soil.

Comment on plants for planting as a pathway.

Plants for planting provide the most likely pathway for entry into, and spread within, the EU (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Potential pathways for Diaphania indica into the EU.

| Pathways (e.g. host/intended use/source) | Life stage | Relevant mitigations [e.g. prohibitions (Annex VI), special requirements (Annex VII) or phytosanitary certificates (Annex XI) within Implementing Regulation 2019/2072] |

|---|---|---|

| Hosts plants for planting (excluding seed) | Eggs, larvae, pupae |

Plants for planting that are hosts of D. indica are not prohibited to import from third countries (Regulation 2019/2072, Annex VI) Plants for planting from third countries require a phytosanitary certificate (Regulation 2019/2072, Annex XI, Part A) |

| Fruits and cut flowers | Eggs, larvae | Phytosanitary certificate is required to import fresh fruits into the EU (2019/2072, Annex XI, Part A) unless exempt by being listed in 2019/2072 Annex XI, Part C). However, no specific requirements are specified in relation to D. indica |

| Soil | Pupae | Soil as such consisting in part of solid organic substances is prohibited to be introduced into the EU from third countries other than Switzerland (Regulation 2019/2072, Annex VI). No requirements are specified for D. indica |

Plants for planting, fruits and cut flowers are the main potential pathways for entry of D. indica (Table 4).

Annual imports of D. indica hosts from countries where the pest is known to occur are provided in Appendix C.

Notifications of interceptions of harmful organisms began to be compiled in Europhyt in May 1994 and in TRACES in May 2020. As of December 2023, 114 interceptions of D. indica, and 5 interceptions of Diaphania spp. have been reported in the Europhyt and TRACES databases. The interceptions for the period 2005–2023 of D. indica are provided in Appendix D.

3.4.2. Establishment

Climatic mapping is the principal method for identifying areas that could provide suitable conditions for the establishment of a pest taking key abiotic factors into account (Baker, 2002). Availability of hosts is considered in Section 3.4.2.1. Climatic factors are considered in Section 3.4.2.2.

Is the pest able to become established in the EU territory?

Yes. There are climate zones in the EU that match those where D. indica occurs and hosts occur in these zones that can support establishment. The pest has already been established in Madeira, Portugal.

Many genera of D. indica host plants are present or are grown widely across the EU such as beans (Phaseolus spp.), cowpea (Vigna unguiculata), cucumber (Cucumis sativus), melon (Cucumis melo), pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata), watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) and summer squash (Cucurbita pepo), which are all important within the EU region. The main hosts of the pest cultivated in the EU between 2018 and 2022 are shown in Table 5.

TABLE 5.

Crop area of Diaphania indica key hosts in the EU in 1000 ha (Eurostat accessed on 22/1/2024).

| Crop | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common beans | 96.87 | 91.28 | 91.37 | 97.64 | 88.22 |

| Courgettes and marrows | 41.26 | 40.93 | 44.47 | 44.50 | 42.76 |

| Cucumbers | 32.65 | 33.70 | 29.33 | 29.94 | 26.36 |

| Muskmelons | 70.52 | 69.82 | 69.04 | 70.19 | 62.93 |

| Watermelons | 73.71 | 74.54 | 64.43 | 68.05 | 56.95 |

3.4.2.1. Climatic conditions affecting establishment

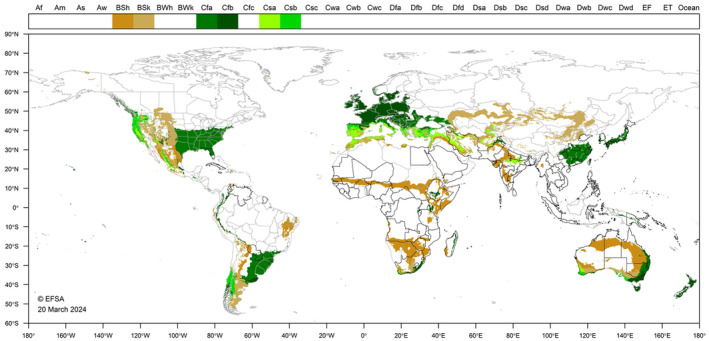

The global Köppen–Geiger climate zones (Kottek et al., 2006) describe terrestrial climate in terms of average minimum winter temperatures and summer maxima, amount of precipitation and seasonality (rainfall pattern) (EFSA PLH Panel, 2022). D. indica is currently present in tropical and sub‐tropical areas in America, Africa, Asia, Macaronesia (Madeira) and Oceania (Figure 3). Based on locations where the pest is reported in literature, D. indica may be capable of establishment outdoors in southern Europe, but it seems unable to survive in cooler climates. Low temperatures, as indicated by frost, may limit establishment to northern areas. In Japan and South Korea, D. indica is a pest in greenhouses protected from cold and wet stress, and it may be capable of living in more temperate climates in these situations (Choi et al., 2003; Kinjo & Arakaki, 2002). Moreover, in South Korea, pupae of D. indica overwinter in soil (Choi et al., 2003). There is uncertainty as to whether D. indica could establish outdoors in central Europe. Nevertheless, there is a possibility that D. indica could occur in greenhouses and indoor plantings in cooler areas.

FIGURE 3.

World distribution of Köppen–Geiger climate types that occur in the EU and which occur in countries where Diaphania indica has been reported.

FIGURE 4 shows frost free areas in the EU which could perhaps be colonised by D. indica. Data for Figure 4 represent the 30‐year period 1988–2017 and was sourced from the Climatic Research Unit high resolution gridded data set CRU TS v. 4.03 at 0.5° resolution (https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/).

FIGURE 4.

Annual frost days in the world (mean 1988–2017) (source: Climatic Research Unit, University of East Anglia, UK).

3.4.3. Spread

Describe how the pest would be able to spread within the EU territory following establishment?

Natural spread by flying adults can occur. Although adults fly, spread is unlikely to be rapid and would probably be restricted to the southern EU (MacLeod, 2005). Eggs, larvae and pupae may be moved over long distances in trade of infested plant materials, specifically plants for planting, fruits and cut flowers.

Comment on plants for planting as a mechanism of spread.

Plants for planting are the main spread mechanism for D. indica over long distances.

Plants for planting are the main spread mechanism for D. indica over long distances. There is no information on the flight capacity of the species.

3.5. Impacts

Would the pests' introduction have an economic or environmental impact on the EU territory?

Yes. If D. indica established more widely in the EU, larval feeding would probably cause an impact on cucurbit crops, but the magnitude of impact is uncertain.

D. indica feeds on the leaves; however, it was also observed to feed on tender stems, flowers and fruits of cucurbitaceous vegetables (Hosseinzade et al., 2014). After defoliation, the caterpillars also attack flowers and fruits of the plant resulting in loss of crop yield (Debnath et al., 2020).

In Madeira, Portugal, no damage is reported so far but the magnitude of impact if D. indica were to spread to areas of concentrated cucumber production, such as in the Netherlands or south‐eastern Spain, is uncertain. In India, the pest was regarded a minor pest of cucurbits in the past, but in recent years, its infestation has become significant and on a regular basis (Halder et al., 2017). In Goa, India, D. indica caused an average of about 93% damage with maximum of 97.5% on watermelon (Maruthadurai & Veershetty, 2023). In Gujarat, India, it caused 60% and 90% fruit damage in bitter gourd and little gourd, respectively, during 2003 and 2004. In pointed gourd, the foliage damage by the larvae was 25%–30% (Jhala et al., 2005). In Karnataka, India, the foliage damage by larvae ranged from 25% to 30% in pointed gourd and 3%–14% in bitter gourd (Nagaraju et al., 2018). D. indica was also found in cucumber plants in West Java, Indonesia. In cucumber plants, one larva per leaf of D. indica can cause a yield loss of 10% (Schreiner, 1991). In Bengkulu Tengah Regency, Indonesia, Nadrawati et al. (2023) observed variations in the density of D. indica larvae, and the percentage of melon leaf damage with the mean population density of larvae being 1.5 per plant, and the percentage of infected leaves 29.5. Also, in India and Sri Lanka, D. indica is an important pest of edible snake gourd (Debnath et al., 2020; Debnath et al., 2022) and gherkins (Ganehiarachchi, 1997).

3.6. Available measures and their limitations

Are there measures available to prevent pest entry, establishment, spread or impacts such that the risk becomes mitigated?

Yes. Although the existing phytosanitary measures identified in Section 3.3.2 do not specifically target D. indica, they mitigate the likelihood of its entry into, establishment and spread within the EU (see also Section 3.6.1).

3.6.1. Identification of potential additional measures

Phytosanitary measures (prohibitions) are currently applied to soil (see Section 3.3.2).

Additional potential risk reduction options and supporting measures are shown in Sections 3.6.1.1 and 3.6.1.2.

3.6.1.1. Additional potential risk reduction options

Potential additional control measures are listed in Table 6.

TABLE 6.

Selected control measures (a full list is available in EFSA PLH Panel, 2018) for pest entry/establishment/spread/impact in relation to currently unregulated hosts and pathways. Control measures are measures that have a direct effect on pest abundance.

| Control measure/risk reduction option (blue underline = Zenodo doc, blue = WIP) | RRO summary | Risk element targeted (entry/establishment/spread/impact) |

|---|---|---|

| Require pest freedom | Pest free place of production (e.g. place of production and its immediate vicinity is free from pest over an appropriate time period, e.g. since the beginning of the last complete cycle of vegetation, or past 2 or 3 cycles). Pest free production site | Entry/Spread/Impact |

| Growing plants in isolation | Place of production is insect proof originate in a place of production with complete physical isolation | Entry/Spread/Impact |

| Managed growing conditions | Used to mitigate likelihood of infestation at origin. Plants collected directly from natural habitats, have been grown, held and trained for at least two consecutive years prior to dispatch in officially registered nurseries, which are subject to an officially supervised control regime | Entry/Spread |

| Biological control and behavioural manipulation |

Pest control such as: a) biological control Many natural enemies, including predators and parasitoids, have been identified for D. indica among them Elasmus indicus (Hymenoptera: Elasmidae), Apanteles taragamae and A. machaeralis (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), Brachymeria excarinata and B. margaroniae (Hymenoptera: Chalcididae), Trichogramma confusum (Hymenoptera:Trichogrammatidae) and Scenocharops sp. (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae) (Peter & David, 1991). In Bangladesh, about 41% D. indica larvae were found parasitised by a natural parasitoid, Apanteles taragamae (Barmon et al., 2021). The entomopathogenic nematodes Heterorhabditis indica (Rhabditida: Heterorhabditidae) and Steinernema carpocapsae (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae) are considered effective biological control agents (Everatt et al., 2015; Gayathri and Nisha, 2023). Soumya et al. (2017) found that Dolichogenidea stantoni (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) is a potential biocontrol agent for D. indica b) mating disruption Sex pheromone components (E)‐11‐hexadecenal (E11‐16:Ald), (E,E)‐10,12‐hexadecadienal (EE10,12‐16:Ald) and hexadecanal (16:Ald) were identified (Choi et al., 2009; Wakamura et al., 1998) |

Spread/Impact |

| Chemical treatments on crops including reproductive material | Used to mitigate likelihood of infestation of pests susceptible to chemical treatments. In a field efficacy trial against D. indica on snake gourd and ridge gourd in Bangladesh, Barmon et al. (2021) found that the application of neem oil, deltamethrin, mahogany oil and cypermethrin reduced the infestation level compared to untreated control (23.3%, 18.8%, 30.8%, 24.2% and 37.0% leaf infestation, respectively. The efficacy of insecticides against D. indica larvae was investigated on zucchini flowers in Queensland, Australia. It was found that compared to unsprayed control, less larvae were found in Bacillus thuringiensis aizawai treatment, while only few were found in the other treatments (methomyl, emamectin benzoate, indoxacarb, bifenthrin, spinosad, novaluron and methoxyfenozide) (Kay, 2007). Laboratory experiments in Pakistan on watermelon plants revealed that treatments with emamectin benzoate, triazophos, cartap hydrochloride, dimethoate were effective (100% mortality) against D. indica caterpillars (Khanzada et al., 2021) | Entry/Establishment/Spread/Impact |

| Chemical treatments on consignments or during processing |

Use of chemical compounds that may be applied to plants or to plant products after harvest, during process or packaging operations and storage. The treatments addressed in this information sheet are:

|

Entry/Spread |

| Physical treatments on consignments or during processing |

This information sheet deals with the following categories of physical treatments: irradiation/ionisation; mechanical cleaning (brushing, washing); sorting and grading; and removal of plant parts. This information sheet does not address: heat and cold treatment (information sheet 1.14) The measure is expected to have an effect although specific info for the pest is not available |

Entry/Spread |

| Cleaning and disinfection of facilities, tools and machinery | The physical and chemical cleaning and disinfection of facilities, tools, machinery, facilities and other accessories (e.g. boxes, pots, hand tools) | Spread |

| Waste management | Treatment of the waste (deep burial, composting, incineration, chipping, production of bioenergy) in authorised facilities and official restriction on the movement of waste. The measure is expected to have an effect although specific info for the pest is not available | Establishment/Spread |

| Heat and cold treatments | Controlled temperature treatments aimed to kill or inactivate pests without causing any unacceptable prejudice to the treated material itself. Relevant treatments under this measure are: autoclaving; steam; hot water; hot air; cold treatment | Entry/Spread |

| Controlled atmosphere | Treatment of plants by storage in a modified atmosphere (including modified humidity, O2, CO2, temperature, pressure) | Entry/Spread (via commodity) |

| Post‐entry quarantine and other restrictions of movement in the importing country | Post‐entry quarantine involves temporal, spatial and end‐use restrictions in the importing country for import of relevant commodities; ‘Relevant commodities’ are plants, plant parts and other materials that may carry pests, either as infection, infestation or contamination | Establishment/Spread |

3.6.1.2. Additional supporting measures

Potential additional supporting measures are listed in Table 7.

TABLE 7.

Selected supporting measures (a full list is available in EFSA PLH Panel, 2018) in relation to currently unregulated hosts and pathways. Supporting measures are organisational measures or procedures supporting the choice of appropriate risk reduction options that do not directly affect pest abundance.

| Supporting measure (blue underline = Zenodo doc, blue = WIP) | Summary | Risk element targeted (entry/establishment/spread/impact) |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection and trapping |

ISPM 5 (FAO, 2023) defines inspection as the official visual examination of plants, plant products or other regulated articles to determine if pests are present or to determine compliance with phytosanitary regulations The effectiveness of sampling and subsequent inspection to detect pests may be enhanced by including trapping and luring techniques |

Entry/Establishment/Spread/Impact |

| Laboratory testing | Examination, other than visual, to determine if pests are present using official diagnostic protocols. Diagnostic protocols describe the minimum requirements for reliable diagnosis of regulated pests | Entry/Establishment/Spread |

| Sampling |

According to ISPM 31 (FAO, 2008), it is usually not feasible to inspect entire consignments, so phytosanitary inspection is performed mainly on samples obtained from a consignment. It is noted that the sampling concepts presented in this standard may also apply to other phytosanitary procedures, notably selection of units for testing For inspection, testing and/or surveillance purposes the sample may be taken according to a statistically based or a non‐statistical sampling methodology |

Entry |

| Phytosanitary certificate and plant passport |

According to ISPM 5 (FAO, 2023) a phytosanitary certificate and a plant passport are official paper documents or their official electronic equivalents, consistent with the model certificates of the IPPC, attesting that a consignment meets phytosanitary import requirements: a) export certificate (import) b) plant passport (EU internal trade) |

Entry/Spread |

| Certified and approved premises | Mandatory/voluntary certification/approval of premises is a process including a set of procedures and of actions implemented by producers, conditioners and traders contributing to ensure the phytosanitary compliance of consignments. It can be a part of a larger system maintained by the NPPO in order to guarantee the fulfilment of plant health requirements of plants and plant products intended for trade. Key property of certified or approved premises is the traceability of activities and tasks (and their components) inherent the pursued phytosanitary objective. Traceability aims to provide access to all trustful pieces of information that may help to prove the compliance of consignments with phytosanitary requirements of importing countries | Entry/Spread |

| Certification of reproductive material (voluntary/official) | Plants come from within an approved propagation scheme and are certified pest free (level of infestation) following testing; Used to mitigate against pests that are included in a certification scheme | Entry/Spread |

| Delimitation of Buffer zones | ISPM 5 (FAO, 2023) defines a buffer zone as 'an area surrounding or adjacent to an area officially delimited for phytosanitary purposes in order to minimize the probability of spread of the target pest into or out of the delimited area, and subject to phytosanitary or other control measures, if appropriate'. The objectives for delimiting a buffer zone can be to prevent spread from the outbreak area and to maintain a pest free production place (PFPP), site (PFPS) or area (PFA) | Spread |

| Surveillance | Surveillance to guarantee that plants and produce originate from a pest free area could be an option | Spread |

3.6.1.3. Biological or technical factors limiting the effectiveness of measures

Internal feeding in fruit with entry holes sealed make infested fruit difficult to detect unless cut open.

3.7. Uncertainty

No key uncertainties of the assessment have been identified.

4. CONCLUSIONS

D. indica satisfies all the criteria that are within the remit of EFSA to assess for it to be regarded as a potential Union quarantine pest (Table 8).

TABLE 8.

The Panel's conclusions on the pest categorisation criteria defined in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants (the number of the relevant sections of the pest categorisation is shown in brackets in the first column).

| Criterion of pest categorisation | Panel's conclusions against criterion in regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding union quarantine pest | Key uncertainties |

|---|---|---|

| Identity of the pest (Section 3.1 ) | The identity of D. indica is established | None |

| Absence/presence of the pest in the EU (Section 3.2 ) | Within the EU, D. indica is known to occur only in Madeira, Portugal | None |

| Pest potential for entry, establishment and spread in the EU (Section 3.4 ) | D. indica is able to enter, become established and spread within the EU territory especially in the southern EU MS. The main pathways are plants for planting, cut flowers and fruits | None |

| Potential for consequences in the EU (Section 3.5 ) | The introduction of the pest could cause yield and quality losses especially of cucurbit crops and reduce the value of fruits | None |

| Available measures (Section 3.6 ) | There are measures available to prevent entry, establishment and spread of D. indica in the EU. Risk reduction options include inspections, chemical and physical treatments on consignments of fresh plant material from infested countries and the production of plants for import in the EU in pest free areas | None |

| Conclusion (Section 4 ) | D. indica satisfies all the criteria that are within the remit of EFSA to assess for it to be regarded as a potential Union quarantine pest | |

| Aspects of assessment to focus on/scenarios to address in future if appropriate | ||

ABBREVIATIONS

- EPPO

European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization

- FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization

- IPPC

International Plant Protection Convention

- ISPM

International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures

- MS

Member State

- PLH

EFSA Panel on Plant Health

- PZ

Protected Zone

- TFEU

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

- ToR

Terms of Reference

GLOSSARY

- Containment (of a pest)

Application of phytosanitary measures in and around an infested area to prevent spread of a pest (FAO, 2023).

- Control (of a pest)

Suppression, containment or eradication of a pest population (FAO, 2023).

- Entry (of a pest)

Movement of a pest into an area where it is not yet present, or present but not widely distributed and being officially controlled (FAO, 2023).

- Eradication (of a pest)

Application of phytosanitary measures to eliminate a pest from an area (FAO, 2023).

- Establishment (of a pest)

Perpetuation, for the foreseeable future, of a pest within an area after entry (FAO, 2023).

- Greenhouse

A walk‐in, static, closed place of crop production with a usually translucent outer shell, which allows controlled exchange of material and energy with the surroundings and prevents release of plant protection products (PPPs) into the environment.

- Hitchhiker

An organism sheltering or transported accidentally via inanimate pathways including with machinery, shipping containers and vehicles; such organisms are also known as contaminating pests or stowaways (Toy & Newfield, 2010).

- Impact (of a pest)

The impact of the pest on the crop output and quality and on the environment in the occupied spatial units

- Introduction (of a pest)

The entry of a pest resulting in its establishment (FAO, 2023).

- Pathway

Any means that allows the entry or spread of a pest (FAO, 2023).

- Phytosanitary measures

Any legislation, regulation or official procedure having the purpose to prevent the introduction or spread of quarantine pests, or to limit the economic impact of regulated non‐quarantine pests (FAO, 2023).

- Quarantine pest

A pest of potential economic importance to the area endangered thereby and not yet present there, or present but not widely distributed and being officially controlled (FAO, 2023).

- Risk reduction option (RRO)

A measure acting on pest introduction and/or pest spread and/or the magnitude of the biological impact of the pest should the pest be present. A RRO may become a phytosanitary measure, action or procedure according to the decision of the risk manager.

- Spread (of a pest)

Expansion of the geographical distribution of a pest within an area (FAO, 2023).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

If you wish to access the declaration of interests of any expert contributing to an EFSA scientific assessment, please contact interestmanagement@efsa.europa.eu.

REQUESTOR

European Commission

QUESTION NUMBER

EFSA‐Q‐2024‐00044

COPYRIGHT FOR NON‐EFSA CONTENT

EFSA may include images or other content for which it does not hold copyright. In such cases, EFSA indicates the copyright holder and users should seek permission to reproduce the content from the original source. Figure 1: © Courtesy of Fera; Figure 4: © Courtesy of Climatic Research Unit, University of East Anglia, UK.

PANEL MEMBERS

Claude Bragard, Paula Baptista, Elisavet Chatzivassiliou, Francesco Di Serio, Paolo Gonthier, Josep Anton Jaques Miret, Annemarie Fejer Justesen, Alan MacLeod, Christer Sven Magnusson, Panagiotis Milonas, Juan A. Navas‐Cortes, Stephen Parnell, Roel Potting, Philippe L. Reignault, Emilio Stefani, Hans‐Hermann Thulke, Wopke Van der Werf, Antonio Vicent Civera, Jonathan Yuen, and Lucia Zappalà.

MAP DISCLAIMER

The designations employed and the presentation of material on any maps included in this scientific output do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the European Food Safety Authority concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

APPENDIX A. Diaphania indica host plants/species affected

A.1.

Source: CABI CPC (CABI, online) and EPPO GD (EPPO, online).

| Host name | Plant family | Common name | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benincasa hispida | Cucurbitaceae | Ash gourd, ash pumpkin, Chinese preserving melon, Chinese squash, wax gourd, white gourd, winter melon | CABI (online) |

| Brassica juncea var. juncea | Brassicaceae | Broad‐leaf mustard, Chinese mustard, Chinese turnip, India mustard, Japanese mustard, leaf mustard, spinach mustard, tuberous‐rooted, mustard, white mustard, wild mustard, brown mustard, Indian mustard | CABI (online) |

| Cajanus cajan | Fabaceae | Bengal pea, cajan pea, Congo pea, dal, pigeon pea, red gram | CABI (online) |

| Citrullus lanatus | Cucurbitaceae | Citrul, egusi melon, watermelon | CABI (online), EPPO (online) |

| Coccinia grandis | Cucurbitaceae | Ivy gourd, kovai fruit, scarlet gourd, scarlet‐fruited ivy gourd | CABI (online) |

| Cucumis melo | Cucurbitaceae | Cantaloupe, melon, muskmelon | CABI (online), EPPO (online) |

| Cucumis melo var. dudaim | Cucurbitaceae | Dudaim melon, pomegranate melon, Queen Anne's pocket melon, smellmelon | CABI (online) |

| Cucumis sativus | Cucurbitaceae | Cucumber, gherkin, timun | CABI (online) |

| Cucurbita moschata | Cucurbitaceae | Canada crookneck, cushaw, musky gourd | CABI (online) |

| Cucurbita pepo | Cucurbitaceae | Edible gourd, garden marrow, pumpkin, summer squash | CABI (online) |

| Gossypium herbaceum | Malvaceae | Asiatic cotton, Levant cotton, short‐staple cotton | CABI (online) |

| Lagenaria siceraria | Cucurbitaceae | Bottle gourd, calabash gourd, Chinese squash, monkey apple, spaghetti squash, white‐flowered gourd, cucuzzi | CABI (online) |

| Luffa acutangula | Cucurbitaceae | Angled loofah, Chinese okra, dishcloth gourd, East Indian okra, loofah, strainer vine | CABI (online) |

| Luffa aegyptiaca | Cucurbitaceae | Loofah, sponge cucumber, sponge gourd, vegetable sponge | CABI (online) |

| Momordica charantia | Cucurbitaceae | Balsam apple, balsam pear, bitter balsam apple, bitter gourd, bitter melon, paria | CABI (online) |

| Musa textilis | Musaceae | Manila hemp | CABI (online) |

| Passiflora | Passifloraceae | – | CABI (online) |

| Phaseolus | Fabaceae | – | CABI (online) |

| Trichosanthes cucumerina | Cucurbitaceae | Club gourd, serpent gourd, snake gourd, wild snake gourd | CABI (online) |

| Vigna unguiculata | Fabaceae | Black‐eyed pea, common cowpea, cowpea, long bean, southern pea | CABI (online) |

APPENDIX B. Distribution of Diaphania indica

B.1.

Distribution records based on CABI (online), EPPO (online) and Symbiota Collections of Arthropods Network (SCAN, online).

| Region | Country | Sub‐national (e.g. state) | Status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | Angola | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | |

| Benin | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Cameroon | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Central African Republic | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Comoros | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Congo, Democratic republic of the | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Cote d'Ivoire | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Ethiopia | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Gabon | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Gambia | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Guinea | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Kenya | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Liberia | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Madagascar | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Malawi | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Mali | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Mauritania | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Mauritius | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Mozambique | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Niger | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Nigeria | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Reunion | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Saint Helena | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Senegal | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Seychelles | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Sierra Leone | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Somalia | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| South Africa | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Tanzania | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Uganda | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Zambia | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Zimbabwe | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| America | Cuba | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | |

| French Guiana | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Jamaica | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Paraguay | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Puerto Rico | Absent, pest no longer present | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| United States of America | Florida | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | |

| Mississippi* | Present, no details | Symbiota Collections of Arthropods Network | ||

| South California* | Present, no details | Symbiota Collections of Arthropods Network | ||

| Texas* | Present, no details | Symbiota Collections of Arthropods Network | ||

| Venezuela | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Asia | Bangladesh | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | |

| Brunei Darussalam | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Cambodia | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| China | Guangdong | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | |

| Guizhou | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Hainan | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Hubei | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Shandong | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Shanghai | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Xianggang (Hong Kong) | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Zhejiang | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Christmas Island | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| India | Andhra Pradesh | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | |

| Bihar | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Goa | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Gujarat | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Haryana | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Karnataka | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Kerala | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Maharashtra | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Odisha | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Tamil Nadu | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Uttar Pradesh | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| West Bengal | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Indonesia | Java | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | |

| Maluku | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Sulawesi | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Sumatra | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Iran | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Japan | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| South Korea | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Laos | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Malaysia | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| West | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Maldives | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Myanmar | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Pakistan | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Philippines | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Saudi Arabia | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Singapore | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Sri Lanka | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Taiwan | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Thailand | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Vietnam | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Yemen | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| EU | Portugal | Madeira | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) |

| Oceania | American Samoa | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | |

| Australia | New South Wales | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | |

| Northern Territory | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Queensland | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Western Australia | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Fiji | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| French Polynesia | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Guam | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Kiribati | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Marshall Islands | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Micronesia | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Northern Mariana Islands | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Palau | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Papua New Guinea | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Solomon Islands | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Tonga | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) | ||

| Vanuatu | Present, no details | CABI (online), EPPO (online) |

There are no other references for the pest's presence in these States.

APPENDIX C. Import data

C.1.

TABLE C.1 Fresh or chilled pumpkins, squash and gourds 'Cucurbita spp.' imported in tonnes into the EU from regions where Diaphania indica is known to occur (Source: Eurostat accessed on 23/2/2024).

| Country | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angola | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Australia | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Bangladesh | 3945.3 | 2629.0 | 5314.1 | 7770.7 | 13,328.4 |

| Cambodia | 16.2 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 130.0 | 98.6 |

| Cameroon | 178.6 | 652.9 | 273.4 | 17.3 | 49.8 |

| China | 30,296.0 | 26,740.9 | 27,716.7 | 21,115.4 | 27,035.2 |

| Congo | 199.7 | 223.5 | 156.2 | 88.5 | 7.6 |

| Côte d'Ivoire (Ivory Coast) | 593.8 | 111.9 | 0.4 | 2.6 | 0.0 |

| Guinea‐Bissau | 1777.2 | 900.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| India | 14,333.5 | 15,140.3 | 20,794.6 | 38,255.2 | 49,935.7 |

| Iran | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1781.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Jamaica | 0.0 | 38.2 | 28.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Japan | 83.5 | 204.2 | 30.8 | 0.6 | 15.4 |

| Kenya | 694.1 | 3877.4 | 373.1 | 1054.7 | 3866.9 |

| Laos | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Madagascar | 51.6 | 206.0 | 300.0 | 49.3 | 72.0 |

| Malawi | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Malaysia | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Mali | 6.3 | 0.0 | 13.0 | 21.3 | 91.4 |

| Mauritania | 0.0 | 380.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 977.2 |

| Mauritius | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 461.8 | 581.0 |

| Nigeria | 10.1 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 74.7 | 3.1 |

| Philippines | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Senegal | 108,435.8 | 96,365.5 | 80,606.0 | 56,683.5 | 175,758.7 |

| South Africa | 555,373.8 | 1,201,220.0 | 1,727,980.5 | 1,761,379.7 | 1,284,840.5 |

| Sri Lanka | 275.1 | 2082.1 | 412.2 | 104.3 | 91.0 |

| Taiwan | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Tanzania | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 217.6 | 20.8 |

| Thailand | 2427.6 | 301.4 | 506.5 | 226.6 | 229.2 |

| Uganda | 151.3 | 242.1 | 866.2 | 1036.9 | 377.8 |

| United Kingdom | 405,739.5 | 289,800.1 | 216,022.2 | 214,451.6 | 183,248.0 |

| United States | 109.4 | 94.8 | 962.4 | 763.2 | 396.5 |

| Viet Nam | 481.2 | 255.5 | 226.9 | 1.5 | 1.3 |

| Zimbabwe | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 109.2 |

TABLE C.2 Cucumbers and gherkins, fresh or chilled imported in tonnes into the EU from regions where Diaphania indica is known to occur (Source: Eurostat accessed on 23/2/2024).

| Country | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | 194.0 | 195.5 | 108.3 | 140.8 | 142.6 |

| Cameroon | 3.0 | 170.2 | 177.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| China | 7.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| India | 1568.8 | 1774.9 | 3012.2 | 3644.1 | 4892.0 |

| Iran | 6364.6 | 21,877.8 | 1975.3 | 560.0 | 894.8 |

| Japan | 181.4 | 65.9 | 281.5 | 43.1 | 47.4 |

| Madagascar | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Malaysia | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7.6 |

| Philippines | 4.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Senegal | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 32,902.8 |

| Singapore | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| South Africa | 5.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 14.2 | 10.1 |

| Sri Lanka | 53.4 | 69.5 | 51.9 | 57.6 | 17.0 |

| Thailand | 9.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 7.3 |

| Uganda | 49.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| United Kingdom | 169,267.1 | 180,218.6 | 17,680.7 | 15,762.1 | 31,765.4 |

| United States | 10.0 | 5.6 | 189.7 | 276.4 | 45.6 |

| Viet Nam | 0.0 | 0.0 | 40.0 | 141.5 | 178.6 |

| Yemen | 0.0 | 0.0 | 70.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Mauritania | 0.0 | 380.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 977.2 |

| Mauritius | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 461.8 | 581.0 |

| Nigeria | 10.1 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 74.7 | 3.1 |

| Philippines | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Senegal | 108,435.8 | 96,365.5 | 80,606.0 | 56,683.5 | 175,758.7 |

| South Africa | 555,373.8 | 1,201,220.0 | 1,727,980.5 | 1,761,379.7 | 1,284,840.5 |

| Sri Lanka | 275.1 | 2082.1 | 412.2 | 104.3 | 91.0 |

| Taiwan | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Tanzania | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 217.6 | 20.8 |

| Thailand | 2427.6 | 301.4 | 506.5 | 226.6 | 229.2 |

| Uganda | 151.3 | 242.1 | 866.2 | 1036.9 | 377.8 |

| United Kingdom | 405,739.5 | 289,800.1 | 216,022.2 | 214,451.6 | 183,248.0 |

| United States | 109.4 | 94.8 | 962.4 | 763.2 | 396.5 |

| Viet Nam | 481.2 | 255.5 | 226.9 | 1.5 | 1.3 |

| Zimbabwe | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 109.2 |

TABLE C.3 Fresh or chilled beans 'Vigna spp., Phaseolus spp.', shelled or unshelled imported in tonnes into the EU from regions where Diaphania indica is known to occur (Source: Eurostat accessed on 23/2/2024).

| Country | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angola | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 76.2 |

| Australia | 20.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Bangladesh | 381.9 | 193.5 | 371.1 | 297.8 | 567.9 |

| Benin | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 47.5 | 0.0 |

| Cambodia | 14.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1131.6 | 399.8 |

| Cameroon | 1207.9 | 2539.6 | 2093.8 | 1536.3 | 1120.2 |

| China | 28,410.9 | 21,152.8 | 774.3 | 2393.4 | 0.0 |

| Congo | 1935.1 | 954.3 | 1229.3 | 931.9 | 849.1 |

| Côte d'Ivoire (Ivory Coast) | 68.8 | 30.4 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 1.5 |

| Ethiopia | 156,561.5 | 183,002.8 | 171,711.6 | 143,234.1 | 138,323.5 |

| Gambia | 3766.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Guam | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| India | 4131.3 | 2360.3 | 4126.9 | 2183.3 | 1213.5 |

| Indonesia | 888.6 | 173.4 | 314.5 | 151.2 | 383.1 |

| Iran | 90.8 | 1940.4 | 17.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Japan | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Kenya | 1,667,393.8 | 1,572,841.8 | 1,432,711.5 | 1,335,963.0 | 1,219,298.5 |

| South Korea | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 6.0 |

| Laos | 372.3 | 299.6 | 58.4 | 630.8 | 717.3 |

| Madagascar | 14,809.5 | 16,033.9 | 9631.3 | 27.0 | 188.3 |

| Malawi | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Malaysia | 723.7 | 2671.6 | 78.8 | 1.4 | 0.0 |

| Maldives | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Mali | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 54.4 | 45.0 |

| Mauritania | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2050.0 |

| Mauritius | 151.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Mozambique | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| Myanmar (Burma) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 200.0 | 0.9 | 1638.5 |

| Nigeria | 2607.8 | 3.9 | 3.1 | 4.4 | 14.3 |

| Philippines | 2.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.3 | 0.0 |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Senegal | 1,139,358.1 | 1,479,123.3 | 1781,200.3 | 1,692,376.2 | 1,289,908.9 |

| South Africa | 387.0 | 243.0 | 19.6 | 0.0 | 124.2 |

| Sri Lanka | 712.3 | 180.2 | 939.5 | 2402.2 | 4458.5 |

| Tanzania | 8870.8 | 10,435.3 | 23,611.4 | 36,420.0 | 19,146.6 |

| Thailand | 3708.1 | 2916.6 | 2755.6 | 2434.8 | 4027.9 |

| Uganda | 2368.1 | 2531.0 | 1856.3 | 1488.5 | 816.0 |

| United Kingdom | 268,925.7 | 250,179.2 | 35,935.7 | 27,674.3 | 28,790.2 |

| United States | 0.1 | 0.2 | 1.8 | 99.1 | 213.7 |

| Viet Nam | 717.5 | 437.4 | 308.7 | 0.0 | 20.8 |

| Zambia | 4169.8 | 953.3 | 128.0 | 1714.8 | 304.0 |

| Zimbabwe | 8584.3 | 5315.1 | 4609.5 | 3513.1 | 0.1 |

APPENDIX D. Interception data

D.1.

TABLE D.1 Interceptions of Diaphania indica in commodities imported into the EU Member States and Switzerland (Source: Europhyt accessed on 25/1/2024).

| Report year | Country of export | Plant species | Number of interceptions | Harmful organism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | Bangladesh | Momordica sp. | 2 | Diaphania indica |

| 2005 | Dominican Republic | Momordica sp. | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2005 | India | Momordica charantia | 2 | Diaphania indica |

| 2005 | India | Momordica sp. | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2005 | Kenya | Momordica charantia | 4 | Diaphania indica |

| 2006 | Dominican Republic | Momordica sp. | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2006 | India | Momordica charantia | 5 | Diaphania indica |

| 2006 | India | Momordica sp. | 2 | Diaphania indica |

| 2006 | Kenya | Momordica sp. | 7 | Diaphania indica |

| 2006 | Kenya | Momordica charantia | 14 | Diaphania indica |

| 2006 | Kenya | Momordica sp. | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2006 | Kenya | Solanum melongena | 2 | Diaphania indica |

| 2006 | Pakistan | Momordica charantia | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2007 | Bangladesh | Citrus aurantifolia | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2007 | Bangladesh | Citrus sp. | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2007 | Bangladesh | Cucurbita sp. | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2007 | Bangladesh | Momordica charantia | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2007 | Bangladesh | Momordica sp. | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2007 | India | Momordica charantia | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2007 | India | Momordica sp. | 4 | Diaphania indica |

| 2007 | Kenya | Momordica charantia | 5 | Diaphania indica |

| 2007 | Kenya | Momordica sp. | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2008 | India | Citrus aurantifolia | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2008 | India | Momordica charantia | 5 | Diaphania indica |

| 2008 | India | Momordica sp. | 5 | Diaphania indica |

| 2008 | Kenya | Momordica charantia | 3 | Diaphania indica |

| 2008 | Kenya | Momordica sp. | 5 | Diaphania indica |

| 2008 | Thailand | Momordica sp. | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2009 | Bangladesh | Momordica sp. | 2 | Diaphania indica |

| 2009 | India | Momordica charantia | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2009 | India | Momordica sp. | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2009 | Kenya | Momordica charantia | 2 | Diaphania indica |

| 2009 | Kenya | Momordica sp. | 7 | Diaphania indica |

| 2009 | Kenya | Solanum melongena | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2010 | Dominican Republic | Momordica sp. | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2010 | Kenya | Momordica charantia | 2 | Diaphania indica |

| 2010 | Kenya | Solanum melongena | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2011 | Kenya | Momordica charantia | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2011 | Kenya | Momordica charantia | 2 | Diaphania sp. |

| 2011 | Pakistan | Momordica charantia | 2 | Diaphania indica |

| 2011 | Pakistan | Momordica sp. | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2012 | Bangladesh | Momordica charantia | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2012 | Bangladesh | Momordica sp. | 4 | Diaphania indica |

| 2012 | Pakistan | Momordica sp. | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2012 | Sri Lanka | Momordica sp. | 2 | Diaphania indica |

| 2013 | Dominican Republic | Momordica charantia | 1 | Diaphania sp. |

| 2013 | India | Momordica charantia | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2013 | Pakistan | Momordica sp. | 1 | Diaphania indica |

| 2013 | Pakistan | Momordica sp. | 1 | Diaphania sp. |

| 2014 | Panama | Cucurbita maxima | 3 | Diaphania sp. |

| 2020 | Costa Rica | Sechium sp. | 1 | Diaphania sp. |

TABLE D.2 Summary of interceptions (third country source by year).

| Source\year | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2020 | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kenya | 4 | 24 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 58 | ||||

| India | 3 | 7 | 5 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 29 | |||||

| Bangladesh | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 14 | |||||||

| Pakistan | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 7 | |||||||

| Dominican Republic | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||||||

| Panama | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||

| Sri Lanka | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Costa Rica | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Thailand | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Sum | 10 | 33 | 16 | 20 | 14 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 119 |

For the years 2005–2009, 31 out of 93 interceptions were reported by the UK (Europhyt, accessed on 19.3.2024).

EFSA PLH Panel (EFSA Panel on Plant Health) , Bragard, C. , Baptista, P. , Chatzivassiliou, E. , Di Serio, F. , Gonthier, P. , Jaques Miret, J. A. , Justesen, A. F. , Magnusson, C. S. , Milonas, P. , Navas‐Cortes, J. A. , Parnell, S. , Potting, R. , Reignault, P. L. , Stefani, E. , Thulke, H.‐H. , Van der Werf, W. , Vicent Civera, A. , Yuen, J. , … MacLeod, A. (2024). Pest categorisation of Diaphania indica . EFSA Journal, 22(5), e8806. 10.2903/j.efsa.2024.8806

Adopted: 18 April 2024

Notes

An EPPO code, formerly known as a Bayer code, is a unique identifier linked to the name of a plant or plant pest important in agriculture and plant protection. Codes are based on genus and species names. However, if a scientific name is changed the EPPO code remains the same. This provides a harmonised system to facilitate the management of plant and pest names in computerised databases, as well as data exchange between IT systems (EPPO, 2019; Griessinger & Roy, 2015).

Referred to as oriental melon (Cucumis melon L. var. makuwa).

Referred to as sponge cucumber (Luffa cylindrica).

Referred to as cotton (Gossypium indicum).

REFERENCES

- Aguiar, A. M. F. , & Karsholt, O. (2006). Systematic catalogue of the entomofauna of the Madeira archipelago and Selvagens islands. Lepidoptera 1. – Boletim do Museu municipal do Funchal (Historia natural). Suplemento, 9, 1–139. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, R. , Chowdhury, S. U. M. , Md. Abdul Karim, M. M. , Hossain, A. , & Mustafi, A. A. (2016). Pest risk analysis (PRA) of cucurbits in Bangladesh. Strengthening phytosanitary capacity in Bangladesh project plant quarantine wing Department of Agricultural Extension. https://dae.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/dae.portal.gov.bd/page/902599be_5f17_4c92_9a29_676fd187c1cc/PRA%20of%20Cucurbits%2CSPCBP%2C%20PQW%2C%20DAE_2016.pdf

- Ashfaq, M. , Akhtar, S. , Rafi, M. A. , Mansoor, S. , & Hebert, P. D. N. (2017). Mapping global biodiversity connections with DNA barcodes: Lepidoptera of Pakistan. PLoS One, 12(3), e0174749. 10.1371/journal.pone.0174749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ba‐Angood, R. (1979). Bionomics of the melon worm Palpita (Diaphania) indica (Saund) (Pyralidae: Lepidoptera) in PDR of Yemen. Zeitschrift für Angewandte Entomologie, 88(1–5), 332–336. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, R. H. A. (2002). Predicting the limits to the potential distribution of alien crop pests. In Hallman G. J. & Schwalbe C. P. (Eds.), Invasive arthropods in agriculture: Problems and solutions (pp. 207–241). Science Publishers Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Barma, P. , & Jha, S. (2014). Studies on bio‐ecology and voracity of leaf roller (Diaphania indica Saunders, lepidoptera: Pyralidae) on pointed gourd (Trichosanthes dioica Roxb.). African Journal of Agricultural Research. 9(36), 2790–2798. [Google Scholar]