Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes, a foodborne pathogen, exhibits high adaptability to adverse environmental conditions and is common in the food industry, especially in ready-to-eat foods. L. monocytogenes strains pose food safety challenges due to their ability to form biofilms, increased resistance to disinfectants, and long-term persistence in the environment. The aim of this study was to evaluate the presence and genetic diversity of L. monocytogenes in food and related environmental products collected from 2014 to 2022 and assess antibiotic susceptibility and biofilm formation abilities. L. monocytogenes was identified in 13 out of the 227 (6%) of samples, 7 from food products (meat preparation, cheeses, and raw milk) and 6 from food-processing environments (slaughterhouse-floor and catering establishments). All isolates exhibited high biofilm-forming capacity and antibiotic susceptibility testing showed resistance to several classes of antibiotics, especially trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and erythromycin. Genotyping and core-genome clustering identified eight sequence types and a cluster of three very closely related ST3 isolates (all from food), suggesting a common contamination source. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) analysis revealed resistance genes conferring resistance to fosfomycin (fosX), lincosamides (lin), fluoroquinolones (norB), and tetracycline (tetM). In addition, the qacJ gene was also detected, conferring resistance to disinfecting agents and antiseptics. Virulence gene profiling revealed the presence of 92 associated genes associated with pathogenicity, adherence, and persistence. These findings underscore the presence of L. monocytogenes strains in food products and food-associated environments, demonstrating a high virulence of these strains associated with resistance genes to antibiotics, but also to disinfectants and antiseptics. Moreover, they emphasize the need for continuous surveillance, effective risk assessment, and rigorous control measures to minimize the public health risks associated to severe infections, particularly listeriosis outbreaks. A better understanding of the complex dynamics of pathogens in food products and their associated environments can help improve overall food safety and develop more effective strategies to prevent severe health consequences and economic losses.

Keywords: Listeria monocytogenes, food safety, antimicrobial resistance, genetic diversity, biofilm formation

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, public health has increasingly focused on foodborne diseases, in which microbiologically contaminated foods play an important role [1]. Among foodborne pathogens, bacteria are the most common ones, causing many diseases in humans and animals. Common bacteria found in foods include Salmonella species, Shigella species, Listeria monocytogenes, Bacillus species, Yersinia species, Campylobacter species, Clostridium botulinum, Clostridium perfringens, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Vibrio cholera [2,3].

Listeria monocytogenes is a foodborne pathogen isolated from food and food processing environments that is known for its high adaptability to adverse environmental conditions [4] such as low temperature, low pH, high pressure, and high salt concentrations [5] and for being widespread in the environment, including water, soil, and wastewater [6]. This adaptability not only allows for L. monocytogenes to grow in a variety of environmental conditions, but also contributes to antimicrobial resistance and biofilm formation on a wide range of surfaces found in food production environments, allowing for L. monocytogenes to survive and proliferate [7,8,9]. In the food processing context, incorrect handling during production, processing, storage, and transportation can cause food-borne illness [10], indicating the possibility of L. monocytogenes contamination of foods during and after processing [11].

L. monocytogenes, an opportunistic human pathogen, is a significant public health problem as it is associated with frequent hospitalizations and widespread outbreaks of foodborne illness [12,13]. This pathogen is responsible for the spread of listeriosis, primarily through the ingestion of contaminated food. The disease can cause serious complications such as meningitis and septicemia [10] and is associated with a high morbidity and mortality [14], especially among populations at risk such as the elderly, pregnant women, newborns, and immunocompromised people [4,7]. Although the incidence of listeriosis is relatively low, mortality rate is high, affecting approximately 20–25% of patients [15,16].

The food production environment promotes bacterial development by providing continuous source of nutrients [6]. Pathogens have properties such as the ability to form and persist in biofilms, making it difficult to manage the contamination situation in food production facilities [6,17,18]. L. monocytogenes is prevalent in the food industry, particularly in ready-to-eat (RTE) foods, such as in milk [19], cheese [20], smoked fish, ice cream, patés, and vegetables [21]. This is due to its ability to colonize food processing environments through biofilm formation, resistance to sanitizing chemicals, and high tolerance to adverse conditions [17,22,23]. Antimicrobial resistance in microorganisms isolated from various foods is also a major concern. Antibiotics such as aminopenicillin (ampicillin or amoxicillin), benzylpenicillin (penicillin G and gentamicin, often used in combination with aminoglycosides), trimethoprim alone or in combination with sulfamethoxazole, erythromycin, and tetracyclines can treat L. monocytogenes infections [22]. L. monocytogenes was found to have low activity against cephalosporins, fosfomycin, and macrolides [17,22].

In recent years, whole-genome sequencing (WGS) has become increasingly important in determining the characteristics and relationships of diverse L. monocytogenes strains isolated in many food productions [1,14] and in linking them to human disease. Bacterial WGS technology is used to accurately identify pathogens and genotypes through techniques such as multiloccus sequence typing (MLST), clonal complex (CC) identification, core genome MLST (cgMLST9, CRISPR-Cas), and serogrouping. It can also detect genetic determinants of antimicrobial resistance, virulence genes, plasmids and mobile genetic elements (MGE), and provide other relevant data to improve our understanding of the pathogen epidemiology, ecology, and evolution [24,25]. High-resolution clustering improves linking cases to detect specific outbreaks, builds confidence in identifying their microbial source, and detect antimicrobial resistance reservoirs. Nowadays, WGS has evolved to the point of common use in research and reference laboratories handling L. monocytogenes, allowing real-time routine genomic surveillance and outbreak investigation [24,25,26].

The aim of this study was to perform phenotypic and genomic characterization, as well as evaluate the antimicrobial resistance and properties of L. monocytogenes strains obtained from food products and food-associated processing environments. This work provides important information of genetic diversity and illustrates the utility of WGS in improving food safety management by establishing relationships between strains and highlights the critical need for improved detection and control methods by directly linking the high morbidity and mortality rates of listeriosis to the imperative for enhanced safety measures in food management.

2. Results

2.1. Prevalence and L. monocytogenes Identification

In this present study, 227 samples obtained from food products or food-processing environments were collected and analyzed for the presence of L. monocytogenes. All the presumptive L. monocytogenes isolates obtained using Oxford medium appeared as gray-to-black-color colonies surrounded by a black halo. Green-to-blue colonies were observed in CHROM agar. A series of biochemical tests, catalase reaction, Gram-stain, hemolysis assessment, and carbohydrate were performed to confirm and differentiate L. monocytogenes. The tests confirmed the presence of L. monocytogenes through various tests such as Gram-stain, catalase reaction, and hemolysis test. The bacteria appeared as small rods with rounded ends and showed characteristics like narrow β-hemolysis, positive rhamnose fermentation, and negative mannitol and xylose fermentation. The overall positivity of L. monocytogenes was 6% (13/227), similarly distributed among food products (n = 7) and food-associated environments (n = 6). Taxonomic identification of the 13 presumptive L. monocytogenes isolates was confirmed by DNA sequencing of the PCR-amplified 16S rDNA (99.8–100% identity).

2.2. Antibiogram of L. monocytogenes Isolates from Food Products and Food Associated Environments

Table 1 summarizes the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of the 13 L. monocytogenes from food products and food-associated environments. Resistance to 12 antimicrobial agents, belonging to β-lactams (meropenem and ampicillin), quinolones (ciprofloxacin), lincosamides (clindamycin), macrolides (erythromycin), aminoglycosides (kanamycin and gentamicin), penicillins (penicillin G), rifampicins, glycopeptides (vancomycin), sulfonamides (trimethroprim-sulphamethoxazol), and oxazolidinones (linezolin) was observed. Among the L. monocytogenes strains tested, the highest level of resistance observed was for trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, with 38.4% (5/13) of isolates showing resistance, followed by erythromycin, of which 15.5% (2/13) isolates showed antimicrobial resistance. Particularly, 7.6% (one isolate) exhibited a multidrug resistance phenotype, indicating resistance to at least three distinct classes of antibiotics.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial resistance profiles from L. monocytogenes strains and sequence types identified in L. monocytogenes isolates.

| Strain | Isolation Year | Source | Antibiotics Tested | Multi-Resistance Profile | Sequence Type | cgMLST | Clonal Complex | Lineage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistant | Susceptible | ||||||||

| A | 2021 | Meat preparation | STX | MRP-AMP-CIP-DA-E-K-CN-P-RD-VA-LNZ | No | ST3207 | CC121 | II | |

| B | 2022 | Alheira | DA-SXT | MRP-AMP-CIP-E-K-CN-P-RD-VA-LNZ | No | ST9 | CC9 | II | |

| C | 2022 | Turkey kebab with chorizo and peppers | P | MRP-AMP-CIP-DA-E-K-CN-P-RD-VA-LNZ-SXT | No | ST155 | CC155 | II | |

| D | 2014 | Alheira pasta packaged in aerobiosis | P | MRP-AMP-CIP-DA-E-K-CN-P-RD-VA-LNZ-SXT | No | ST3 | cluster_1 (≤7 ADs) | CC3 | I |

| E | 2014 | Alheira dough in vacuum | - | MRP-AMP-CIP-DA-E-K-CN-P-RD-VA-LNZ-SXT | No | ST9 | CC9 | II | |

| F | 2014 | Alheira pasta packaged in aerobiosis | P | MRP-AMP-CIP-DA-E-K-CN-P-RD-VA-LNZ-SXT | No | ST3 | cluster_1 (≤7 ADs) | CC3 | I |

| G | 2014 | Fresh alheira pasta | - | MRP-AMP-CIP-DA-E-K-CN-P-RD-VA-LNZ-SXT | No | ST3 | cluster_1 (≤7 ADs) | CC3 | I |

| H | 2019 | Slaughterhouse floor | E-SXT | MRP-AMP-CIP-DA- K-CN-P-RD-VA-LNZ | No | ST121 | CC121 | II | |

| I | 2018 | Catering establishments | - | MRP-AMP-CIP-DA-E-K-CN-P- | No | ST8 | CC8 | II | |

| J | 2018 | Catering establishments | - | MRP-AMP-CIP-DA-E-K-CN-P-RD-VA-LNZ-SXT | No | ST3 | CC3 | I | |

| K | 2018 | Catering establishments | MRP-DA-E-CN-RD-VA-SXT-LNZ | AMP-CIP-K-P | Yes | ST87 | CC87 | I | |

| L | 2018 | Catering establishments | SXT | MRP-AMP-CIP-DA-E-K-CN-P-RD-VA-LNZ | No | ST121 | CC121 | II | |

| M | 2018 | Catering establishments | - | MRP-AMP-CIP-DA-E-K-CN-P-RD-VA-LNZ-SXT | No | ST1 | CC1 | I | |

Legend: cgMLST—core-genome clustering analysis; ST—sequence type; MRP—meropenem; AMP—ampicillin; CIP—ciprofloxacin; DA—clindamycin; E—erythromycin; K—kanamycin; CN—gentamicin; P—penicillin G; VA—vancomycin; SXT—trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole; LNZ—linezolin.

2.3. L. monocytogenes Typing and Core-Genome Clustering Analysis

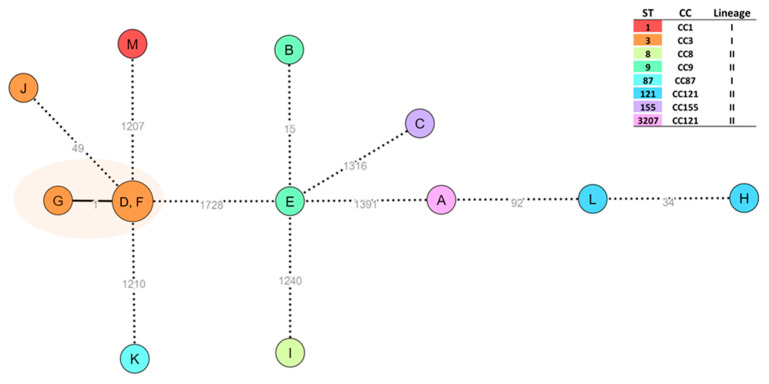

Among the 13 L. monocytogenes isolates, eight sequence types (ST) were identified: ST1 (n = 1), ST3 (n = 4), ST8 (n = 1), ST9 (n = 2), ST87 (n = 1), ST121 (n = 2), ST155 (n = 1), and ST3207 (n = 1). A core-genome clustering analysis by cgMLST was performed. The results revealed one genetic cluster of three high closely related ST3 isolates (D, F, and G), with a maximum of one AD between them (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Core-genome clustering analysis of L. monocytogenes (thirteen isolates). The Minimum Spanning Tree (MST) was constructed based on the cgMLST 1748-loci Pasteur schema [27]. Each circle (node) contains the sample code and represents a unique allelic profile, with numbers on the connecting lines representing allelic distances (ADs) between nodes. Cluster analysis was conducted with ReporTree v.2.0.3 [28] and data visualization was adapted from the GrapeTree (MSTreeV2 method) dashboard [29]. Straight and dotted lines reflect nodes linked with allelic distances (ADs) below and above a threshold of seven ADs, which can provide a proxy to the identification of genetic clusters with potential epidemiological concordance [30]. Nodes are colored according to the sequence type (ST), with clonal complex (CC) and lineage also presented. The surrounding orange shadow highlights a cluster supported by ≤7 ADs.

2.4. Whole-Genome Sequencing (Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Genes)

The genome assembly were characterized by an average sequencing depth of 103.9x, with the number of contigs ranging from 15 to 41 and genome sizes between 2,881,182 and 3,153,118 nucleotides. The complete draft genome sequences of the 13 L. monocytogenes isolates analyzed in this study are deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) database under the ENAProject number PRJEB31216. The individual accession numbers for these sequences range from ERS18961302 to ERS18961314.

Among the 13 isolates studied by WGS, all carried the fosX gene, which confers resistance to fosfomicin. Subsequently, the lin gene, associated with resistance to lincosamides, was identified in 12 different isolates, except isolate E. Additionally, the norB gene associated with resistance to fluoroquinolones was detected in five isolates (isolates A, B, F, H, and L). Additionally, tetM, detected in isolate L, confers resistance to tetracycline. The qacJ gene, known for conferring an efflux mechanism and resistance to disinfectants and antiseptics, was detected in two isolates (isolate H and isolate L).

Analysis of virulence factors identified 92 associated genes, and all the strains had the following 58 genes: AgrA (regulator of accessory gene regulator (agr) system), FlaA (encodes flagellin A, a component of flagella involved in motility), FlgC and FlgE (involved in flagellar assembly), GadB and GadC (part of acid resistance system), Gmar (glyoxalase/bleomycin resistance protein/dioxygenase), OppA (oligopeptide transport system substrate-binding protein), OrfX and OrfZ (proteins), Rli55 and Rli60 (RNAIII-inhibiting peptide, involved in RNA regulation), Rsbv (regulatory factor involved in stress response), bilE (resistance protein E), bsh and btlB (salt hydrolase), codY (global regulator of metabolism and virulence genes), ctaP (copper transporter ATPase), dal (D-alanine-D-alanine ligase, involved in cell wall biosynthesis), degU (transcriptional regulator, involved in biofilm formation and motility), dltA (D-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid biosynthesis protein, involved in cell wall modification), fbpA (ructose–bisphosphate aldolase, involved in glycolysis), hly (hemolysin), inlC (internalin C: cell invasion), lgt (galactosyl transferase, involved in lipoteichoic acid biosynthesis), lhrC (lipoprotein), lipA (lipoate synthase), lisK, lisR, stp, tcsA, virR, and mogR (virulence regulation), lmo0610, lmo2085 and uHpt (proteins), lpeA and lplA1 (lipoprotein), lsp (signal peptidase, involved in protein secretion), mpl (zinc–metalloprotease), mprf (phosphatidylglycerol lysyltransferase, involved in membrane composition), per, pgdA (deacetylates: cell wall modification), pgla (phospholipase), plcA (phosphadidylinositol phosphodiesterase (PI-PLC), prfA (regulation), prsA2 and tig (chaperone, involved in protein folding and secretion), pycA (pyruvate carboxylase, involved in metabolism), recA (recombinase A, involved in DNA repair and recombination), relA (involved in stress response), secA2 (protein translocase subunit, involved in protein secretion), sigB (sigma factor B, involved in stress response and virulence gene regulation), sipX and sipZ (putative effector protein), sod (involved in oxidative stress response), srtA and srtB (involved in cell wall anchoring of surface proteins), and svpA (secreted virulence protein). Other virulence genes were also identified, such as ActA (n = 4), Ami (n = 8), Aut (n = 11), Eut_operon (n = 8), lap (n = 12), lapB (n = 8), OatA (n = 7), chiA (n = 12), ClpB (n = 3), ClpC (n = 4), ClpE (n = 11), ClpP (n = 12), ctsR (n = 12), fri (n = 7), fur (n = 12), gtcA (n = 12), hfg (n = 13), hupC (n = 12), iap (n = 5), inlA (n = 12), inlB (n = 7), lmo0610 (n = 8), murA (n = 7), plcB (n = 7), vip (n = 6), GadA (n = 8), htrA (n = 9), inlF (n = 4), inlH (n = 6), inlJ (n = 5), inlK (n = 4), lm0514 (n = 2), lm2026 (n = 3), and intA (n = 7).

2.5. Evaluation of the Biofilm Formation of L. monocytogenes Isolates

To ensure greater consistentcy in the comparison of the results, these were normalized against L. monocytogenes ATCC 7973. As shown in Figure 2, all strains were observed to have a high biofilm-forming capacity, with no significant differences between strains originating from food products and strains from food-related environments. Strain C, isolated from a turkey skewer with chorizo and chili peppers, had the lowest biofilm-forming ability, followed by strains L and M, obtained from a food production facility.

Figure 2.

% Biofilm formation capacity (expressed as % in comparison to reference strain) of L. monocytogenes isolated from different food products and food-associated environments. Statistical significance was determined using Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

3. Discussion

Monitoring the prevalence, antimicrobial resistance, and genetic diversity of L. monocytogenes in foods is important for risk assessment, source identification, and establishment of control measures, as well as for building an effective surveillance system for this pathogen. The importance of L. monocytogenes for public health is emphasized by its frequent contamination of various food products [13,31]. When compared to global reports, there is high variability and different range of prevalence rates for L. monocytogenes in different countries. RTE food samples in Poland [32] had a higher prevalence of 13.5%, while semi-finished meat products in Russia [33] had 12% positivity. Turkey [34] and Estonia [35] had lower rates at 5% and 3.6%, respectively, and in Northern Greece [36], analysis of raw meat, raw meat preparations, ready-to-eat meat products, processing surfaces, and the environment showed a prevalence of 3.96%. When it comes to livestock, especially beef, pork and chicken, a study in China found an incidence of 7.1%, while in Europe the incidence was slightly higher at 8.3% [37]. Regional variations in food safety are influenced by a variety of factors such as differences in food safety regulations, surveillance intensity, and reporting practices. Different measures and the implementation of good agriculture practices can be applied in farming and food of animal production stages to prevent or reduce food safety hazards. The EU and the US have adopted preventive approaches to improve food quality assessment, including monitoring the food industry environmental microbiome [38], preventing cross-contamination in food processing, rotation disinfectants to reduce persister strains, and testing for the presence of L. monocytogenes regularly [39].

In our study, although L. monocytogenes isolates were found to be susceptible to a wide range of antibiotics, some strains showed to be susceptible to antibiotics such as meropenem, ampicillin, vancomycin, rifampicin, and ciprofloxacin. The highest resistance was to trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, to which 38.4% of the isolates were resistant, followed by erythromycin and meropenem, to which 15.5% and 7.6% of the isolates were resistant. L. monocytogenes has developed acquired natural resistance to a wide range of β-lactams and cephalosporins [40]. As such, based on the antimicrobial resistance profiles observed in the present study, the detection of reduced susceptibility to first-line antibiotics, such as penicillin, ampicillin, and trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole, is of concern. The resistance of L. monocytogenes to these antibiotics is likely due to the overuse of antibiotics in livestock for both growth promotion and treatment of bacterial infections [41].

This study also identified the presence of five resistance genes, including genes conferring resistance to fosfomycin (fosX), lincosamides (lin), fluoroquinolones (norB), and tetracycline (tetM). In addition, two isolates carried the qacJ gene, which is associated with the efflux mechanisms conferring resistance to disinfecting agents and antiseptics. This resistance complicates eradication efforts, especially in the food production environment. This two L. monocytogenes were isolated from different environments, such as slaughterhouse floor and catering establishments, which suggests that these genes are widely distributed in food and food environments. The evidence of sanitizer tolerance, resistance, and an enhanced ability to form biofilms suggests that we are in the presence of a strain classified as persistent. It has been documented that L. monocytogenes strains possess the capability to adapt to biocides, specifically ammonium quaternary compounds (referred to as quats or QACs), and a potential association between this adaptation and the development of resistance to the fluoroquinolone antibiotic ciprofloxacin has been suggested [42].

In recent years, L. monocytogenes has shown an increase in resistance to antibiotics, particularly in geographic regions with varied antimicrobial use [43]. While widespread resistance was not observed in our study, resistance to antibiotics like penicillin and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole was noted in food (sample A and sample B) and environmental samples (sample H, sample K, and sample L) over time. This highlights the potential for antibiotic efficacy loss in the future. The detection of multidrug-resistant strains in various food or food-related samples is a major concern worldwide, as showed in studies conducted in Spain [43] and South Africa [44]. In Spain, poultry preparation samples found that 49.1% of isolates exhibited an MDR phenotype, and in South Africa, resistance against various antibiotics was also reported, namely against sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, and erythromycin. Regarding the presence of multidrug-resistant strains, 38.10% were found to have an MDR phenotype [44]. Similarly, a study in China [41] found low resistance rates in isolates from food, livestock, and clinical samples, with tetracycline showing the highest resistance. The high prevalence of antimicrobial resistance observed in these studies may be strongly related to the widespread use of these drugs in veterinary medicine. Therefore, MDRs typically pose challenges in effectively treating the infections they cause, which can lead to higher hospital costs and prolonged antibiotic treatment [43,44].

Regarding L. monocytogenes typing, we found considerable diversity as eight STs were identified, ST9, ST155, ST3, ST121, ST8, ST87, ST1, and ST3207, with ST3 and ST121 being the most common. Moreover, the MDR isolate belonged to ST87. Notably, we detected a cluster of three very closely related ST3 isolates from 2014, suggesting a common contamination source. A common food denominator of these three samples is “alheira”, which is a traditional smoked naturally fermented meat sausage produced in the north of Portugal. This observation suggests that outbreaks are often linked to contamination from processing and handling environments and sanitation failures [45]. External factors like poor hygiene practices and ineffective disinfectants contribute to continued exposure. Specific genes in certain L. monocytogenes strains contribute to their persistence. Addressing residual strains is a major challenge for food manufacturers, as they can cause cross-contamination and be difficult or impossible to remove [7]. In the Czech Republic, ST3 is prevalent in RTE foods and is a dominant clone globally, found in both human cases and food sources [46]. Studies in Brazil [47] and Poland [48] also found ST3 in environmental samples, cheese products, and RTE foods. Our results are consistent with results obtained in other studies. The ST121 strain was found in food products in 2014 and food establishments in 2018, highlighting its prevalence and distribution in different geographical regions. A study in China [41] showed ST121 in food isolates, indicating its presence in that region. In Switzerland [49], studies revealed that within the food isolate category, ST121 had a lower incidence of human listeriosis. This suggests that ST121 is common in food-related contexts but less harmful clinically [41]. CC121 clonal complexes are often associated with food origins and are characterized by hypovirulence and increased susceptibility to infection in people with severe immunodeficiency diseases. Also, CC121 was observed to persist in food production environments. A study by Maury et al., involving 6641 CC121 food isolates from 2005–2016, found that 4.4% of the samples originated from dairy products, 53.2% were meat-related, and 21.2% were seafood-related based on 6641 isolates [50]. In our study, the presence of ST121 was detected in both food and environmental samples over different time periods. CC121 strains were found in a catering establishment sample (sample K) in 2018 and a slaughterhouse floor sample (sample H) in 2019. In 2021, meat preparation sample (sample A) showed a unique ST designated 3207 belonging to CC121. ST9 [50], which is commonly found in food, was also found in two samples. Studies in China [51] showed that ST9 is more prevalent in food isolates, suggesting an association with food and processing environments. In Latvia [52], certain sequence types including ST9 are frequently identified, with associations to food, food-processing environments, and ruminant farms. Various studies have found ST8, ST87, and ST1 in food preparation environments, particularly in ready-to-eat foods [53]. ST8 is common and known to be persistent in food samples [41,54], linked to foodborne listeriosis outbreaks [41]. Between May and September 2017, ST8 was associated with the consumption of ready-to-eat cold-smoked salmon produced in Poland. This multi-country outbreak of 12 cases of listeriosis caused by L. monocytogenes ST8 was reported in three EU/EEA countries: in Denmark (six cases), Germany (five cases) and France (one case) [55]. Our ST8 L. monocytogenes isolate was obtained in 2018 from catering establishments; it belongs to CC8 and lineage II. It has been previously shown that L. monocytogenes ST8 strains demonstrate strong viability in food processing plants, with potential for transfer between different food businesses via raw food materials. This phenomenon may contribute to the persistent presence of specific clones of L. monocytogenes in environmental niches and facilitate their transmission between food establishments [53]. ST1 and ST87 have been detected in food products, such as raw milk cheeses in Portugal [56] and South Africa [57]. Another study conducted in Switzerland [49] found ST1 to be the most prevalent sequence type in human strains. The diverse sequence types of L. monocytogenes identified in our study underscore the dynamic nature of strains in various environments and highlight the diverse roles and associations of these sequence types in food safety and public health.

All the isolates harbored adherence and invasive genes LIPI-1 (Listeria Pathogenicity Island 1), LIPI-2 (Listeria Pathogenicity Island 2), and LIPI-3 (Listeria Pathogenicity Island 3), and L. monocytogenes virulence is directly related to invasiveness and its capability to multiply in a wide range of eukaryotic cells. The presence and prevalence of virulence genes can reflect the risk levels of different L. monocytogenes strains, and it is suggested that persistent strains may be better adapted to grow under stressful conditions, such as temperature, NaCl concentration, and acidity [58]. The utilization of WGS has emerged as a promising and predictive method for assessing the virulence potential and functional characteristics of virulence factors and aids in comprehending virulence mechanisms and strategies but also holds the potential to monitor the risk of listeriosis outbreaks [59]. The significant presence of virulence factors observed in our study correlates with the biofilm formation capacity of the analyzed strains. This connection is evident through the detection of virulence factors associated with biofilm formation, suggesting that the strains can be classified as persistent.

Biofilms are aggregates of microbial cells that are interconnected and adhere tightly to each other or to a surface. Encased in an extracellular multicellular matrix, they play an important role in microbial survival in harsh environments by providing phenotypic flexibility and ecological benefits [60]. L. monocytogenes is resilient and can colonize and survive in food processing facilities. The ability to form biofilms promotes its growth and proliferation in harsh environments [44,61]. In our study, the evaluation of 13 strains of L. monocytogenes from food products and environments related to food production demonstrated the potential to form biofilms. All strains had a strong biofilm-forming ability, and there were no significant differences between strains obtained from food products and strains from environments associated with food production. The high production of biofilms observed in L. monocytogenes strains may also be due to the presence of the DegU virulence gene, which plays a role in biofilm formation and is associated with biofilm formation. Several studies have evaluated biofilm formation. In one of them, samples of food products were used [44], including milk and milk products, and in another study, samples were obtained from the environment [61]. In these studies, 95.2% of the strains isolated from milk and 68.4% of the strains isolated from environment samples showed the ability to form biofilm [44,61].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Collection and Processing

A total of 227 samples obtained from food products (meat preparation, cheeses, and raw milk) and food-associated environments (slaughterhouse floor and catering establishments) were collected from 2014 to 2022. Ten grams per sample were used, and all the samples were collected aseptically and diluted with 90 mL of sterile buffered peptone water (0.1% w/v) and homogenized in a stomacher (Lab Blender, West Sussex, UK) for 30 s at room temperature. Further dilutions (1:10) were obtained in sterile peptone water (0.1% w/v) (BPW, Biokar diagnostics, Allonne, France) and inoculated in triplicate [62].

4.2. Isolation and Identification of L. monocytogenes

According to ISO 11290-1 [63], half Fraser broth (VWR Chemicals, Radnor, PA, USA) was used as the main enrichment medium, followed by incubation at 30 °C for 24 h. Then, 0.1 mL of the aliquots were transferred to Fraser broth (VWR Chemicals) and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. Cultures obtained from half Fraser broth/Fraser broth were then subjected to further analysis: 0.1 mL aliquots were placed on supplemented Oxford agar (VWR Chemicals) and supplemented Palcam agar (VWR Chemicals), incubated at 37 °C for 24–48 h. To confirm the colonies, a series of tests including catalase reaction, Gram-stain, hemolysis assessment, and carbohydrate utilization were performed according to ISO 11290-1 [64]

4.3. Taxonomic Identification of Bacterial Isolates

Total bacterial DNA from the 13 presumptive L. monocytogenes isolates was extracted using the InstaGene Matrix (BioRad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instruction. The 16S rDNA gene was amplified by PCR and then sequenced. PCR amplifications were performed using 25 μL of DreamTaq Hot Start PCR Master Mix 2x (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 0.5 μM fD1 (5′-AGAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′), 0.5 μM rD2 (5′-TAAGGAGGAGGTGATCCAGCC-3′), 50–100 ng of purified DNA and 19 μL of molecular biology-grade water (Thermo Scientific). PCR mixtures were subjected to several amplification cycles, starting with an initial denaturation cycle (95 °C, 3 min), followed by 35 cycles of denaturation (95 °C, 30 s), hybridization (60 °C, 30 s), elongation (72 °C, 1 min), and ending with a final elongation cycle (72 °C, 5 min) in a thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The resulting amplicons were then purified using the Nucleospin Gel and PCR Clean-up kit (Macherey-NagelTM, Düren, Germany) and sent to Eurofins Genomics (Ebersberg, Germany) for DNA sequencing. To determine their taxonomic identification, the nucleotide sequences were analyzed using the BLAST nucleotide server of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 28 February 2024).

4.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Antibiotic susceptibility testing was conducted using the Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method as recommended by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Briefly, 5–6 overnight colonies were suspended in 1 mL of a 0.9% NaCl solution, and the turbidity of this suspension was adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard, corresponding approximately to 1–2 × 108 CFU/mL. The suspension was used to inoculate Mueller–Hinton blood agar. The isolates were tested against a panel of twelve antimicrobial agents with relevance to human and animal health. The diameter of the zones exhibiting complete inhibition was measured. The following panel of antimicrobial disks and concentrations was used: meropenem (MRP-10 μg), ampicillin (AMP-10 μg), ciprofloxacin (CIP-5 μg), clindamycin (CD-2 μg), erythromycin (E-15 μg), kanamycin (KAN-30 μg), gentamicin (CN-10 μg), penicillin G (PEN-10 IU), rifampicin, vancomycin (VA-30 μg), trimethroprim-sulphamethoxazol (SXT-1.25 μg/23.75 μg), and linezolin (LZ-10 μg) [65,66]. Data interpretation was performed according to the recommendation of EUCAST guidelines; in cases where the EUCAST guidelines lacked resistance criteria for Listeria, the guidelines followed were those recommended for Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus spp. by CLSI guidelines [15].

4.5. L. monocytogenes Whole-Genome Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from fresh cultures of all L. monocytogenes using the ISOLATE II Genomic DNA Kit (Bioline, London, UK) and quantified in the Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) with the dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was then prepared using the NexteraXT library preparation protocol (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), and then cluster generation and sequencing (2 × 150 bp) on a NextSeq 2000 instrument (Illumina) were performed. Quality control, trimming, and de novo genome assembly were performed with the INNUca pipeline v4.2.2 “https://github.com/BUMMI/INNUca”, accessed on 28 February 2024 [67] using default parameters. In brief, FastQC v0.11.5 “http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/”, accessed on 28 February 2024 and Trimmomatic v0.38 [68] were used for reads of quality control and improvement. De novo genome assembly was performed with SPAdes v3.14 [69]; reads were aligned with Bowtie v2.2.9 [70] and the assembly was polished with Pilon v1.23 [71] as integrated in INNUca v4.2.2. Species confirmation/contamination screening was performed with Kraken2 v2.0.7 [72]. ST determination was performed with mlst v2.18.1 “https://github.com/tseemann/mlst”, accessed on 28 February 2024. To assess the genomes for acquired antibiotic resistance genes and VFs, ResFinder and VirulenceFinder v2.0 (Center for Genomic Epidemiology, Technical University of Denmark, Lyngby, Denmark) servers were used. The Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) was used to search the genome for acquired antibiotic resistance genes.

ResFinder and VirulenceFinder was firstly employed with cut-offs of 95% percentage of identity (ID) and 60% for the minimum length of coverage. The genome sequences were aligned against the protein sequences from ARG using the default parameters and the Perfect, Strict and Loose hits criteria from the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD), only hits with >70% ID were retained for analysis.

4.6. Core-Genome Clustering Analysis of L. monocytogenes Isolates

For L. monocytogenes strains, allele calling was performed on polished genome assemblies with chewBBACA v2.8.5 [73] using the core-genome Multi Locus Sequence Typing (cgMLST) Pasteur schema built from the 1748 loci [27] available at the Chewie-NS website “https://chewbbaca.online”, accessed on 28 February 2024 [74]. cgMLST clustering analysis was performed with ReporTree v.2.0.3, available via this GitHub repository: “https://github.com/insapathogenomics/ReporTree”, accessed on 28 February 2024 [28] using GrapeTree (MSTreeV2 method) [29], with clusters of closely related isolates identified and characterized at a distance thresholds of 1, 4, 7, and 15 allelic differences (ADs). A threshold of seven ADs may provide a proxy for identifying genetic clusters with potential epidemiological concordance (i.e., “outbreaks”) [30]. Interactive phylogenetic tree visualization was conducted with GrapeTree [29].

4.7. Biofilm Formation Assay

The biofilm formation assay was conducted according to a previously described protocol [75]. In brief, two colonies from a fresh culture were transferred into tubes containing 3 mL of Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB, Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) and incubated at 37 °C for approximately 16 ± 1 h with continuous shaking at 120 rpm, utilizing the ES-80 Shaker-incubator from Grant Instruments (Cambridge, UK). After this incubation period, the bacterial suspension was adjusted to an optical density equivalent to 1 × 106 colony-forming units. Subsequently, 200 μL of bacterial suspensions from different isolates were added to individual wells of a 96-well microplate. A positive control, Listeria ATCC 7973, was included in all plates, and a fresh uninoculated medium was used as a negative control. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h without shaking. Each experiment was performed with seven replicates and performed three times. Biofilm volume assessment was performed using Crystal Violet (CV) staining, following the procedure described by Peeters et al. (2008) [76] with some modifications. After the incubation period, the plates were washed twice with 200 μL of distilled water to remove non-adherent bacterial cells. The plates were then air-dried at room temperature for approximately 2 h to fix the microbial biofilm; then, 100 μL of methanol (VWR International Carnaxide, Portugal) was added to each well and incubated for 15 min. Then, the methanol was removed, and the plates were air-dried again at room temperature for 10 min. To dissolve CV, 100 µL of 33% (v/v) acetic acid was added, and absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Bio Tek elX808U, Winooski, VT, USA) [75]. Biofilm formation results for each isolate were presented as a percentage of the results obtained for the reference strain.

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics including mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) were used where appropriate. Skewness and kurtosis coefficients were calculated to assess univariate normality. The relationship between biofilm formation in different samples from different sources was analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test and independent samples t-test. All statistical analyzes were performed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics 26), and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

The growing threat of antimicrobial resistance in L. monocytogenes is of concern and might pose significant challenges in effectively treating listeriosis in the future, highlighting the need for systematic and inter-sectorial surveillance strategies. Analysis of antimicrobial resistance revealed resistance to important antibiotics, including penicillin, ampicillin, and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, commonly used as a first-line treatment for listeriosis. In this study, we identified different STs of L. monocytogenes strains and characterized their dynamic properties in different environments. The identification of STs such as ST8, ST87, and ST1 in food preparation environments and the presence of STs in foods highlights the potential for cross-contamination and persistence within the food processing and handling continuum. These STs play various roles in food safety and the presence of STs in food and food-processing environments. Educating consumers, food handlers, and food industry professionals about proper handling practices, hygiene protocols, and the consequences of antimicrobial overuse can contribute to safer food production and consumption practices. Comprehensive surveillance is essential to understand the dynamic nature of antimicrobial resistance in L. monocytogenes obtained from food products and food-associated processing environments and to develop strategies to minimize the potential public health risks associated with antibiotic-resistant L. monocytogenes and adopting integrated food safety management systems.

Acknowledgments

This work received support and help from FCT/MCTES (LA/P/0008/2020 DOI 10.54499/LA/P/0008/2020, UIDP/50006/2020 DOI 10.54499/UIDP/50006/2020, and UIDB/50006/2020 DOI 10.54499/UIDB/50006/2020), through national funds. Adriana Silva is grateful to FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia) for financial support through the PhD grant SFRH/BD/04576/2020.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and V.S.; validation, P.P., V.B. and J.P.G.; investigation, V.S., A.S., A.C., R.B., A.E., C.S., D.C. and L.D.-F.; data curation, V.S., V.B., L.M.C. and Â.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S. and V.S.; writing—review and editing, A.S., V.B. and J.P.G.; supervision, G.I., V.B., J.P.G. and P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Sequencing data generated within this study are deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) database under the ENAProject number PRJEB31216.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the projects UIDB/00772/2020 (Doi:10.54499/UIDB/00772/2020), funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT).

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Wartha S., Bretschneider N., Dangel A., Hobmaier B., Hörmansdorfer S., Huber I., Murr L., Pavlovic M., Sprenger A., Wenning M., et al. Genetic Characterization of Listeria from Food of Non-Animal Origin Products and from Producing and Processing Companies in Bavaria, Germany. Foods. 2023;12:1120. doi: 10.3390/foods12061120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elbehiry A., Abalkhail A., Marzouk E., Elmanssury A.E., Almuzaini A.M., Alfheeaid H., Alshahrani M.T., Huraysh N., Ibrahem M., Alzaben F., et al. An Overview of the Public Health Challenges in Diagnosing and Controlling Human Foodborne Pathogens. Vaccines. 2023;11:725. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11040725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bintsis T. Department of International Trade, TEI of West Macedonia, Kastoria, Greece Foodborne Pathogens. AIMS Microbiol. 2017;3:529–563. doi: 10.3934/microbiol.2017.3.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiśniewski P., Zakrzewski A.J., Zadernowska A., Chajęcka-Wierzchowska W. Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes Strains Isolated from Food and Food Processing Environments. Pathogens. 2022;11:1099. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11101099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiktorczyk-Kapischke N., Skowron K., Grudlewska-Buda K., Wałecka-Zacharska E., Korkus J., Gospodarek-Komkowska E. Adaptive Response of Listeria monocytogenes to the Stress Factors in the Food Processing Environment. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:710085. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.710085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grudlewska-Buda K., Bauza-Kaszewska J., Wiktorczyk-Kapischke N., Budzyńska A., Gospodarek-Komkowska E., Skowron K. Antibiotic Resistance in Selected Emerging Bacterial Foodborne Pathogens—An Issue of Concern? Antibiotics. 2023;12:880. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12050880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osek J., Lachtara B., Wieczorek K. Listeria monocytogenes—How This Pathogen Survives in Food-Production Environments? Front. Microbiol. 2022;13:866462. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.866462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mafuna T., Matle I., Magwedere K., Pierneef R.E., Reva O.N. Whole Genome-Based Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes Isolates Recovered From the Food Chain in South Africa. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:669287. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.669287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matereke L.T., Okoh A.I. Listeria monocytogenes Virulence, Antimicrobial Resistance and Environmental Persistence: A Review. Pathogens. 2020;9:528. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9070528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ulusoy B.H., Chirkena K. Two Perspectives of Listeria monocytogenes Hazards in Dairy Products: The Prevalence and the Antibiotic Resistance. Food Qual. Saf. 2019;3:233–241. doi: 10.1093/fqsafe/fyz035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bahrami A., Moaddabdoost Baboli Z., Schimmel K., Jafari S.M., Williams L. Efficiency of Novel Processing Technologies for the Control of Listeria monocytogenes in Food Products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020;96:61–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2019.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dos Santos J.S., Biduski B., Dos Santos L.R. Listeria monocytogenes: Health Risk and a Challenge for Food Processing Establishments. Arch. Microbiol. 2021;203:5907–5919. doi: 10.1007/s00203-021-02590-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdeen E.E., Mousa W.S., Harb O.H., Fath-Elbab G.A., Nooruzzaman M., Gaber A., Alsanie W.F., Abdeen A. Prevalence, Antibiogram and Genetic Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes from Food Products in Egypt. Foods. 2021;10:1381. doi: 10.3390/foods10061381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nwaiwu O., Onyeaka H., Rees C. Probing the Evolution of Genes Associated with DNA Methylation in Listeria monocytogenes. bioRxiv. 2023 doi: 10.1101/2023.11.04.565605. preprint . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andriyanov P.A., Zhurilov P.A., Liskova E.A., Karpova T.I., Sokolova E.V., Yushina Y.K., Zaiko E.V., Bataeva D.S., Voronina O.L., Psareva E.K., et al. Antimicrobial Resistance of Listeria monocytogenes Strains Isolated from Humans, Animals, and Food Products in Russia in 1950–1980, 2000–2005, and 2018–2021. Antibiotics. 2021;10:1206. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10101206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLauchlin J., Grant K.A., Amar C.F.L. Human Foodborne Listeriosis in England and Wales, 1981 to 2015. Epidemiol. Infect. 2020;148:e54. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820000473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kayode A.J., Okoh A.I. Assessment of the Molecular Epidemiology and Genetic Multiplicity of Listeria monocytogenes Recovered from Ready-to-Eat Foods Following the South African Listeriosis Outbreak. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:20129. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-20175-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tao Q., Wu Q., Zhang Z., Liu J., Tian C., Huang Z., Malakar P.K., Pan Y., Zhao Y. Meta-Analysis for the Global Prevalence of Foodborne Pathogens Exhibiting Antibiotic Resistance and Biofilm Formation. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13:906490. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.906490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niamah A.K. Detection of Listeria monocytogenes Bacteria in Four Types of Milk Using PCR. Pak. J. Nutr. 2012;11:1158–1160. doi: 10.3923/pjn.2012.1158.1160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jobori K.M.A., Aboodi A.H. Detection of Salmonella Spp. and Listeria monocytogenes in Soft White Cheese Using PCR Assays. Int. J. Orig. Res. 2015;1:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silva A., Silva V., Cintas L.M., Pereira E., Maltez L., Rahman T., Igrejas G., Valentão P., Falco V., Poeta P. Listeria monocytogenes in Livestock and Derived Food-Products: Insights from Antibiotic-Resistant Prevalence and Genomic Analysis. J. Bacteriol. Mycol. 2024;11:1216. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kayode A.J., Okoh A.I. Antibiotic Resistance Profile of Listeria monocytogenes Recovered from Ready-to-Eat Foods Surveyed in South Africa. J. Food Prot. 2022;85:1807–1814. doi: 10.4315/JFP-22-090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiktorczyk-Kapischke N., Wałecka-Zacharska E., Skowron K., Kijewska A., Bernaciak Z., Bauza-Kaszewska J., Kraszewska Z., Gospodarek-Komkowska E. Comparison of Selected Phenotypic Features of Persistent and Sporadic Strains of Listeria monocytogenes Sampled from Fish Processing Plants. Foods. 2022;11:1492. doi: 10.3390/foods11101492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calero-Cáceres W., Ortuño-Gutiérrez N., Sunyoto T., Gomes-Dias C.-A., Bastidas-Caldes C., Ramírez M.S., Harries A.D. Whole-Genome Sequencing for Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in Ecuador: Present and Future Implications. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública. 2023;47:1. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2023.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parra-Flores J., Holý O., Bustamante F., Lepuschitz S., Pietzka A., Contreras-Fernández A., Castillo C., Ovalle C., Alarcón-Lavín M.P., Cruz-Córdova A., et al. Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Listeria monocytogenes Strains Isolated From Ready-to-Eat Foods in Chile. Front. Microbiol. 2022;12:796040. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.796040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ronholm J., Nasheri N., Petronella N., Pagotto F. Navigating Microbiological Food Safety in the Era of Whole-Genome Sequencing. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2016;29:837–857. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00056-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moura A., Criscuolo A., Pouseele H., Maury M.M., Leclercq A., Tarr C., Björkman J.T., Dallman T., Reimer A., Enouf V., et al. Whole Genome-Based Population Biology and Epidemiological Surveillance of Listeria monocytogenes. Nat. Microbiol. 2016;2:16185. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mixão V., Pinto M., Sobral D., Pasquale A.D., Gomes J.P., Borges V. ReporTree: A Surveillance-Oriented Tool to Strengthen the Linkage between Pathogen Genetic Clusters and Epidemiological Data. Genome Med. 2022;15:43. doi: 10.1186/s13073-023-01196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou Z., Alikhan N.-F., Sergeant M.J., Luhmann N., Vaz C., Francisco A.P., Carriço J.A., Achtman M. GrapeTree: Visualization of Core Genomic Relationships among 100,000 Bacterial Pathogens. Genome Res. 2018;28:1395–1404. doi: 10.1101/gr.232397.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Walle I., Björkman J.T., Cormican M., Dallman T., Mossong J., Moura A., Pietzka A., Ruppitsch W., Takkinen J. European Listeria WGS typing group Retrospective Validation of Whole Genome Sequencing-Enhanced Surveillance of Listeriosis in Europe, 2010 to 2015. Eurosurveillance. 2018;23:1700798. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.33.1700798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen J., Zhang G., Yang J., Zhao L., Jiang Y., Guo D., Wang X., Zhi S., Xu X., Dong Q., et al. Prevalence, Antibiotic Resistance, and Molecular Epidemiology of Listeria monocytogenes Isolated from Imported Foods in China during 2018 to 2020. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022;382:109916. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2022.109916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szymczak B., Szymczak M., Trafiałek J. Prevalence of Listeria Species and Listeria monocytogenes in Ready-to-Eat Foods in the West Pomeranian Region of Poland: Correlations between the Contamination Level, Serogroups, Ingredients, and Producers. Food Microbiol. 2020;91:103532. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2020.103532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Psareva E.K., Liskova E.A., Razheva I.V., Yushina Y.K., Grudistova M.A., Gladkova N.A., Potemkin E.A., Zhurilov P.A., Sokolova E.V., Andriyanov P.A., et al. Diversity of Listeria monocytogenes Strains Isolated from Food Products in the Central European Part of Russia in 2000–2005 and 2019–2020. Foods. 2021;10:2790. doi: 10.3390/foods10112790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arslan S., Özdemir F. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Resistance of Listeria Species and Molecular Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes Isolated from Retail Ready-to-Eat Foods. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2020;367:fnaa006. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnaa006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koskar J., Kramarenko T., Meremäe K., Kuningas M., Sõgel J., Mäesaar M., Anton D., Lillenberg M., Roasto M. Prevalence and Numbers of Listeria monocytogenes in Various Ready-to-Eat Foods over a 5-Year Period in Estonia. J. Food Prot. 2019;82:597–604. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-18-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Papatzimos G., Kotzamanidis C., Kyritsi M., Malissiova E., Economou V., Giantzi V., Zdragas A., Hadjichristodoulou C., Sergelidis D. Prevalence and Characteristics of Listeria monocytogenes in Meat, Meat Products, Food Handlers and the Environment of the Meat Processing and the Retail Facilities of a Company in Northern Greece. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2022;74:367–376. doi: 10.1111/lam.13620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang H., Luo X., Aspridou Z., Misiou O., Dong P., Zhang Y. The Prevalence and Antibiotic-Resistant of Listeria monocytogenes in Livestock and Poultry Meat in China and the EU from 2001 to 2022: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Foods. 2023;12:769. doi: 10.3390/foods12040769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schirone M., Visciano P. Trends of Major Foodborne Outbreaks in the European Union during the Years 2015–2019. Hygiene. 2021;1:106–119. doi: 10.3390/hygiene1030010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vidovic S., Paturi G., Gupta S., Fletcher G.C. Lifestyle of Listeria monocytogenes and Food Safety: Emerging Listericidal Technologies in the Food Industry. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024;64:1817–1835. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2119205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bouymajane A., Rhazi Filali F., Oulghazi S., Lafkih N., Ed-Dra A., Aboulkacem A., El Allaoui A., Ouhmidou B., Moumni M. Occurrence, Antimicrobial Resistance, Serotyping and Virulence Genes of Listeria monocytogenes Isolated from Foods. Heliyon. 2021;7:e06169. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anwar T.M., Pan H., Chai W., Ed-Dra A., Fang W., Li Y., Yue M. Genetic Diversity, Virulence Factors, and Antimicrobial Resistance of Listeria monocytogenes from Food, Livestock, and Clinical Samples between 2002 and 2019 in China. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022;366:109572. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2022.109572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lakicevic B.Z., Den Besten H.M.W., De Biase D. Landscape of Stress Response and Virulence Genes Among Listeria monocytogenes Strains. Front. Microbiol. 2022;12:738470. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.738470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Panera-Martínez S., Rodríguez-Melcón C., Serrano-Galán V., Alonso-Calleja C., Capita R. Prevalence, Quantification and Antibiotic Resistance of Listeria monocytogenes in Poultry Preparations. Food Control. 2022;135:108608. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.108608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kayode A.J., Okoh A.I. Assessment of Multidrug-Resistant Listeria monocytogenes in Milk and Milk Product and One Health Perspective. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0270993. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0270993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bland R., Brown S.R.B., Waite-Cusic J., Kovacevic J. Probing Antimicrobial Resistance and Sanitizer Tolerance Themes and Their Implications for the Food Industry through the Listeria monocytogenes Lens. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safe. 2022;21:1777–1802. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gelbíčová T., Karpíšková R. Population Structure of Listeria monocytogenes Isolated from Human Listeriosis Cases and from Ready-to-Eat Foods in the Czech Republic. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2019;58:2. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oxaran V., Lee S.H.I., Chaul L.T., Corassin C.H., Barancelli G.V., Alves V.F., De Oliveira C.A.F., Gram L., De Martinis E.C.P. Listeria monocytogenes Incidence Changes and Diversity in Some Brazilian Dairy Industries and Retail Products. Food Microbiol. 2017;68:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kurpas M., Osek J., Moura A., Leclercq A., Lecuit M., Wieczorek K. Genomic Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes Isolated from Ready-to-Eat Meat and Meat Processing Environments in Poland. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:1412. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ebner R., Stephan R., Althaus D., Brisse S., Maury M., Tasara T. Phenotypic and Genotypic Characteristics of Listeria monocytogenes Strains Isolated during 2011–2014 from Different Food Matrices in Switzerland. Food Control. 2015;57:321–326. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.04.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maury M.M., Bracq-Dieye H., Huang L., Vales G., Lavina M., Thouvenot P., Disson O., Leclercq A., Brisse S., Lecuit M. Hypervirulent Listeria monocytogenes Clones’ Adaption to Mammalian Gut Accounts for Their Association with Dairy Products. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2488. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10380-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen M., Cheng J., Zhang J., Chen Y., Zeng H., Xue L., Lei T., Pang R., Wu S., Wu H., et al. Isolation, Potential Virulence, and Population Diversity of Listeria monocytogenes From Meat and Meat Products in China. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:946. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Šteingolde Ž., Meistere I., Avsejenko J., Ķibilds J., Bergšpica I., Streikiša M., Gradovska S., Alksne L., Roussel S., Terentjeva M., et al. Characterization and Genetic Diversity of Listeria monocytogenes Isolated from Cattle Abortions in Latvia, 2013–2018. Vet. Sci. 2021;8:195. doi: 10.3390/vetsci8090195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wieczorek K., Bomba A., Osek J. Whole-Genome Sequencing-Based Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes from Fish and Fish Production Environments in Poland. IJMS. 2020;21:9419. doi: 10.3390/ijms21249419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu B., Yang J., Gao C., Li D., Cui Y., Huang L., Chen X., Wang D., Wang A., Liu Y., et al. Listeriosis Cases and Genetic Diversity of Their Listeria monocytogenes Isolates in China, 2008–2019. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021;11:608352. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.608352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.European Food Safety Authority. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Multi-country Outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes Sequence Type 8 Infections Linked to Consumption of Salmon Products. EFS3. 2018;15:1496E. doi: 10.2903/sp.efsa.2018.EN-1496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Praça J., Furtado R., Coelho A., Correia C.B., Borges V., Gomes J.P., Pista A., Batista R. Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli and Coagulase Positive Staphylococci in Cured Raw Milk Cheese from Alentejo Region, Portugal. Microorganisms. 2023;11:322. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11020322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matle I., Mafuna T., Madoroba E., Mbatha K.R., Magwedere K., Pierneef R. Population Structure of Non-ST6 Listeria monocytogenes Isolated in the Red Meat and Poultry Value Chain in South Africa. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1152. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8081152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vilchis-Rangel R.E., Espinoza-Mellado M.D.R., Salinas-Jaramillo I.J., Martinez-Peña M.D., Rodas-Suárez O.R. Association of Listeria monocytogenes LIPI-1 and LIPI-3 Marker llsX with Invasiveness. Curr. Microbiol. 2019;76:637–643. doi: 10.1007/s00284-019-01671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shi D., Anwar T.M., Pan H., Chai W., Xu S., Yue M. Genomic Determinants of Pathogenicity and Antimicrobial Resistance for 60 Global Listeria monocytogenes Isolates Responsible for Invasive Infections. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021;11:718840. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.718840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferreira V., Wiedmann M., Teixeira P., Stasiewicz M.J. Listeria monocytogenes Persistence in Food-Associated Environments: Epidemiology, Strain Characteristics, and Implications for Public Health. J. Food Prot. 2014;77:150–170. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kayode A.J., Semerjian L., Osaili T., Olapade O., Okoh A.I. Occurrence of Multidrug-Resistant Listeria monocytogenes in Environmental Waters: A Menace of Environmental and Public Health Concern. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021;9:737435. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2021.737435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saraiva C., Silva A.C., García-Díez J., Cenci-Goga B., Grispoldi L., Silva A.F., Almeida J.M. Antimicrobial Activity of Myrtus Communis L. and Rosmarinus Officinalis L. Essential Oils against Listeria monocytogenes in Cheese. Foods. 2021;10:1106. doi: 10.3390/foods10051106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection and Enumeration of Listeria monocytogenes and of Listeria spp.—Part 1: Detection Method. ISO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moura-Alves M., Machado C., Silva J.A., Saraiva C. Shelf-life Determination of an Egg-based Cake, Relating Sensory Attributes Microbiological Characteristics and Physico-chemical Properties. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2022;57:6580–6590. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.16001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.de Vasconcelos Byrne V., Hofer E., Vallim D.C., de Castro Almeida R.C. Occurrence and Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of Listeria monocytogenes Isolated from Vegetables. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2016;47:438–443. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2015.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morobe I.C., Obi C.L., Nyila M.A., Gashe B.A., Matsheka M.I. Prevalence, Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles of Listeria monocytogenes from Various Foods in Gaborone, Botswana. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2009;8:6383–6387. doi: 10.5897/AJB2009.000-9486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Llarena A., Ribeiro-Gonçalves B.F., Nuno Silva D., Halkilahti J., Machado M.P., Da Silva M.S., Jaakkonen A., Isidro J., Hämäläinen C., Joenperä J., et al. INNUENDO: A Cross-sectoral Platform for the Integration of Genomics in the Surveillance of Food-borne Pathogens. EFS3. 2018;15:1498. doi: 10.2903/sp.efsa.2018.EN-1498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Prjibelski A., Antipov D., Meleshko D., Lapidus A., Korobeynikov A. Using SPAdes De Novo Assembler. CP Bioinform. 2020;70:e102. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Langmead B. Aligning Short Sequencing Reads with Bowtie. CP Bioinform. 2010;32:11.7.1–11.7.14. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1107s32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Walker B.J., Abeel T., Shea T., Priest M., Abouelliel A., Sakthikumar S., Cuomo C.A., Zeng Q., Wortman J., Young S.K., et al. Pilon: An Integrated Tool for Comprehensive Microbial Variant Detection and Genome Assembly Improvement. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e112963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wood D.E., Salzberg S.L. Kraken: Ultrafast Metagenomic Sequence Classification Using Exact Alignments. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R46. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-3-r46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Silva M., Machado M.P., Silva D.N., Rossi M., Moran-Gilad J., Santos S., Ramirez M., Carriço J.A. chewBBACA: A Complete Suite for Gene-by-Gene Schema Creation and Strain Identification. Microb. Genom. 2018;4:e000166. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mamede R., Vila-Cerqueira P., Silva M., Carriço J.A., Ramirez M. Chewie Nomenclature Server (Chewie-NS): A Deployable Nomenclature Server for Easy Sharing of Core and Whole Genome MLST Schemas. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D660–D666. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Silva V., Correia E., Pereira J.E., González-Machado C., Capita R., Alonso-Calleja C., Igrejas G., Poeta P. Exploring the Biofilm Formation Capacity in S. Pseudintermedius and Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Species. Pathogens. 2022;11:689. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11060689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Peeters E., Nelis H.J., Coenye T. Comparison of Multiple Methods for Quantification of Microbial Biofilms Grown in Microtiter Plates. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2008;72:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Sequencing data generated within this study are deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) database under the ENAProject number PRJEB31216.