Abstract

Many drugs that serve as first-line medications for the treatment of depression are associated with severe side effects, including liver injury. Of the 34 antidepressants discussed in this review, four have been withdrawn from the market due to severe hepatotoxicity, and others carry boxed warnings for idiosyncratic liver toxicity. The clinical and economic implications of antidepressant-induced liver injury are substantial, but the underlying mechanisms remain elusive. Drug-induced liver injury may involve the host immune system, the parent drug, or its metabolites, and reactive drug metabolites are one of the most commonly referenced risk factors. Although the precise mechanism by which toxicity is induced may be difficult to determine, identifying reactive metabolites that cause toxicity can offer valuable insights for decreasing the bioactivation potential of candidates during the drug discovery process. A comprehensive understanding of drug metabolic pathways can mitigate adverse drug-drug interactions that may be caused by elevated formation of reactive metabolites. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the current state of knowledge on antidepressant bioactivation, the metabolizing enzymes responsible for the formation of reactive metabolites, and their potential implication in hepatotoxicity. This information can be a valuable resource for medicinal chemists, toxicologists, and clinicians engaged in the fields of antidepressant development, toxicity, and depression treatment.

Keywords: antidepressant, reactive metabolite, cytochrome P450, trapping agents, hepatotoxicity

1. Introduction

Antidepressants are the first-line medication for moderate to severe anxiety and depression. These drugs can improve the quality of patient life while lowering disability, morbidity, mortality, and health-care costs (Karp et al., 2009). The classes of antidepressant available on the market reflect advances in drug discovery. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), tricyclic antidepressant (TCAs), tetracyclic antidepressant (TeCAs), and serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor (SARIs) are first-generation antidepressants. Second-generation antidepressants refer to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) that have been introduced in the previous two decades (Lieberman, 2003).

Antidepressants account for 2% to 5% of clinically apparent cases of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) (Andrade et al., 2006). DILI is a leading cause of drug failures in clinical trials, black box warnings, and withdrawals for marketed drugs, but precise mechanisms are difficult to establish because it can involve the parent drug, its metabolites, and the immune system of the host, and also because it may be intrinsic or idiosyncratic (Allison et al., 2023; Hosack et al., 2023). Intrinsic DILI is seen in all patients, and usually depends on dosage, with acetaminophen being a classic example of a safe drug that becomes a hepatotoxin at higher doses. Idiosyncratic DILI is seen in some individuals at doses that are well tolerated by most patients. The inconsistent dose-toxicity relationship for isoniazid makes it a typical example of this category. Idiosyncratic DILI can be further classified into immune-allergic and metabolic-idiosyncratic reactions. Immune-allergic reactions are rare, immune-related responses to the drug itself that are characterized by fever, rash, and eosinophilia. Metabolic-idiosyncratic reactions are triggered by an indirect metabolite of the offending drug that induces. The patterns of injury are categorized as hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed based on the specific abnormalities in circulating liver enzymes seen in individual cases. Identifying liver enzymes in the serum remains the hallmark for diagnosing DILI. Hepatocellular DILI is outlined by an ALT ≥ 5 upper limit of normal (ULN) and ALT/ALP ratio (R value) ≥ 5. Cholestatic DILI is denoted by an ALP ≥ 2 ULN and R ≤ 2. Mixed DILI is characterized by ALT ≥ 3 ULN, ALP ≥ 2 ULN, and 2 < R < 5 (European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address et al., 2019; Hosack et al., 2023). Beyond these forms, other DILI forms such as cholestatic+steatosis and cholestatic+hepatitis have been described (Katarey and Verma, 2016).

Drug metabolism is implicated in drug-induced toxicity (Baillie and Rettie, 2011). In general, metabolism converts drugs to stable and more hydrophilic metabolites that are eliminated from the body without causing harmful effects. Some stable drug metabolites retain the activity of the parent drug, and some may bind non-covalently to other cellular targets and alter their function, though examples of this are relatively limited. Drug metabolism may also generate chemically reactive metabolites such as electrophiles or free radicals that can covalently bind to macromolecules, alter their functions, and cause immunologic reactions or genotoxic effects (Park et al., 2005; Attia, 2010; Park et al., 2011). While the exact etiology of DILI remains unclear, several studies have indicated that the bioactivation of drugs to reactive metabolites, in conjunction with immune-related challenges, is one of significant contributing factors (Zhang and Tang, 2018). Previous studies indicate that for some drugs, the reactive metabolites can lead to liver toxicity by covalent or noncovalent binding mechanisms (Stepan et al., 2011; Orr et al., 2012; Kalgutkar and Dalvie, 2015), including the metabolites of a number of antidepressants (Kalgutkar et al., 2005a; Argikar et al., 2011).

Reactive metabolites can be exceedingly difficult to quantify, or in some cases even detect, because their high reactivities confer very short half-lives. Trapping agents for soft and hard electrophiles are used to screen for reactive metabolites, commonly using in vitro incubations with liver microsomes or S9 liver fractions (Thompson et al., 2011). Soft electrophiles such as epoxides, quinones, quinone-imines, quinone-methides, etc. can be trapped with glutathione (GSH) or N-acetylcysteine (NAc), whereas hard electrophiles like iminiums and aldehydes can be trapped with cyanide or methoxyamine (Kalgutkar, 2017). Identifying reactive metabolites during drug development may enable medicinal chemists to block or decrease bioactivation by altering the drug. However, because the relationship between structural alerts (toxicophores) and their adverse effects on drug metabolism is extremely complicated, systematic elimination of dangerous chemical moieties from therapeutic candidates is still difficult and challenging (Stepan et al., 2011; Kalgutkar and Dalvie, 2015; Thompson et al., 2016).

Although reactive metabolites are often considered as a major DILI risk factor, the causal connections between reactive metabolites and liver injuries remain unclear. Here, our objective is to place into perspective the relationship between reactive metabolites and the liver toxicity associated with antidepressants by reviewing both the bioactivation processes and the hepatotoxicity associated with various antidepressants. We will commence by examining the experimental or theoretical studies concerning the metabolism of antidepressants and the generation of reactive metabolites, including the trapping agents and enzymes involved (Table 1). The liver toxicity score, incidence, dosage, latency, and possible reaction mechanisms that may be involved in toxicity are summarized in Table 2 across different classes of antidepressants. The 34 antidepressants reported in Table 1 were amassed from available literature data on possible reactive metabolite formation from the Web of Science, LiverTox, and PubMed databases published up to the end of 2023.

Table 1.

Summary of antidepressant reactive metabolites

| Reactive metabolite formation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | Name | Trapping agent | Adduct | Proposed RMs | Related P450 |

| MAOIs | Iproniazid | NA | NA | Nitroso | P450 (Kalgutkar et al., 2002) |

| Isocarboxazid | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Phenelzine | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Selegiline | GSH | Yes | Ketene | P450 (Shin, 1997; Sridar et al., 2012) | |

| Tranylcypromine | NA | NA | Imine or ketone | NA (Paech et al., 1980) | |

| TCAs | Amitriptyline | GSH | Yes | Epoxide | CYP1A2, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, CYP3A5 (Wen et al., 2008b) |

| Nortriptyline | GSH | Yes | Epoxide | CYP1A2, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, CYP3A5 (Wen et al., 2008b) | |

| Imipramine | GSH-EE | Yes | Epoxide | CYP2D6, CYP2D2 (Wen and Fitch, 2009) | |

| Desipramine | GSH | Yes | Epoxide | CYP2D6 (Korobkova et al., 2012) | |

| Clomipramine | GSH | Yes | Epoxide or quinone imine | CYP2D6 (Zheng et al., 2007b) | |

| Amineptine and tianeptine | NA | NA | Epoxide | NA(Stepan et al., 2011) | |

| Amoxapine | NA | NA | Epoxide | NA(Wong et al., 2012) | |

| Doxepin | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Protriptyline | NA | NA | Epoxide | NA(Hucker et al., 1975) | |

| Trimipramine | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| TeCAs | Mianserin | GSH-EE, KCN | Yes | Iminium ions | CYP2D6 (Lambert et al., 1989; Riley et al., 1990; Kalgutkar, 2017) |

| SSRIs | Paroxetine | GSH | Yes | Quinone | CYP3A4 (Zhao et al., 2007) |

| Sertraline | NA | NA | NA | CYP2B6, CYP2C19 (Obach et al., 2005; Saiz-Rodríguez et al., 2018) | |

| Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine | NA | NA | NA | NA (Bertelsen et al., 2003; Deodhar and Rihani, 2021) | |

| Citalopram | GSH | NA | NA | NA (Lassila et al., 2015) | |

| Escitalopram | NA | NA | NA | NA (Rao, 2007) | |

| Fluvoxamine | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| SNRIs | Atomoxetine | MeONH2, GSH, and NAc | Yes | Aldehydes, quinone | CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2D6 (MacKenzie et al., 2020), (You et al., 2021) |

| Venlafaxine and Desvenlafaxine | GSH | Yes | Quinone methide | CYP2D6, CYP3A4 (Li et al., 2021) | |

| Agomelatine | GSH, NAc, semicarbazide | Yes | Epoxide | CYP1A2, CYP3A4 (Jian et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2016a) | |

| Duloxetine | GSH or GSH-EE, NAc | Yes | Epoxide | CYP1A2, CYP2D6 (Wu et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2011; Qin et al., 2022a) | |

| NDRIs | Nomifensine | GSH, KCN | Yes | Quinone, quinone imines | P450 (Obach and Dalvie, 2006; Yu et al., 2010a) |

| SARIs | Nefazodone | GSH | Yes | Quinone | CYP3A4 (Kalgutkar et al., 2005b; Thompson et al., 2016; Klopčič and Dolenc, 2019) |

| Trazodone | GSH | Yes | Epoxides, quinone imine | CYP3A4 (Wen et al., 2008a) | |

| Levomilnacipran | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Milnacipran | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

NA: not available; NAc, N-acetylcystein; GSH, reduced glutathione; GSH-EE, glutathione ethyl ester; MeONH2, methoxyamine; KCN, potassium cyanide.

Table 2.

Antidepressant induced liver injury including injury type, liver toxicity score, incidence, dosage, latency, and possible mechanism.

| Class | Name | Injury types | Score* | Incidences | DILI latency | Mechanism | Dose (mg/daily)* | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAOIs | Iproniazid | Hepatocellular injury | A | Withdrawn | 3 days – 6 months | Metabolic idiosyncrasy | 25 to 150 | (Rosenblum et al., 1960) |

| Isocarboxazid | No report on hepatic injury | E | Rare | 1 – 4months | NA | 10 to 60 | (Volz and Gleiter, 1998) | |

| Phenelzine | Cholestasis | C | Less toxic than iproniazid, higher than other MAOIs | 1 – 3 months | Metabolic and genetic | 15 to 60 | (Bonkovsky et al., 1986) (Gómez-Gil et al., 1996) | |

| Selegiline | No report on hepatotoxicity | E | Black box warning | NA | NA | 6 to 12 | (Friedman and Leon, 2007) | |

| Tranylcy-promine | Less risk of hepatotoxicity | D | NA | 1 – 4 months | Metabolic idiosyncrasy | 30 to 60 | (Paech et al., 1980; Ganesan et al., 2019) | |

| TCAs | Amitriptyline | Hepatocellular, cholestasis | B | 2–10% of increased ALT | 1 – 14 months | Immuno-allergic mechanism | 75 to 300 | (Morgan, 1969), (Yon and Anuras, 1975),(Lewis, 2000) |

| Nortriptyline | Hepatocellular, cholestasis | C | 2–10% of increased ALT | 2 – 3 months | Immuno-allergic mechanism | 10 to 150 | (Pedersen and Enevoldsen, 1996) | |

| Imipramine | Hepatocellular, cholestasis | B | 1–22% of increased ALT | 1 – 8 weeks | Immuno-allergic mechanism | 10 to 150 | (Horst et al., 1980) | |

| Desipramine | Hepatocellular, cholestasis | D | NA | 1 – 8 weeks | Immuno-allergic mechanism | 10 to 200 | (Price et al., 1983),(Powell et al., 1968) | |

| Clomipramine | Less toxic than imipramine and desipramine | D | NA | 1 – 4 weeks | NA | 10 to 250 | (Korobkova et al., 2012; Limban et al., 2018) | |

| Amineptine | Cholestasis, hepatic steatosis | NA | Withdrawn | 7 days – 11 months | Immuno-allergic mechanism | 150 to 500 | (Todorović Vukotić et al., 2021),(Ricca Rosellini et al., 1990),(Lazaros et al., 1996) | |

| Tianeptine | Cholestasis, hepatic steatosis | NA | Withdrawn | 2 months | Immuno-allergic mechanism | 25 to 50 | (Larrey et al., 1990; Fromenty and Pessayre, 1995; Stepan et al., 2011) | |

| Amoxapine | Hepatocellular | E | Rare | 1 – 4 weeks | Immuno-allergic mechanism | 25 to 300 | (Patterson, 1987),(Manapany et al., 1993) | |

| Doxepin | Cholestasis, hepatitis | C | Rare | NA | NA | 10 to 300 | (Gronewold et al., 2009) | |

| Protriptyline | Hepatocellular | E | Rare | 1 – 14 months | NA | 15 to 40 | (Remy et al., 1995) | |

| Trimipramine | Hepatocellular | D | Rare | 2 – 8 weeks | NA | 25 to 200 | (Remy et al., 1995) | |

| TeCAs | Mianserin | Cholestasis, hepatocellular | A | Withdrawn | 11 days – 21 months | Metabolic idiosyncrasy | 30 to 300 | (Riley et al., 1990) |

| SSRIs | Paroxetine | Hepatocellular, hepatitis | B | Rare | 2 weeks – 12 months | Metabolic idiosyncrasy | 10 to 50 | (Benbow and Gill, 1997; de Man, 1997) |

| Sertraline | Hepatocellular | B | 0.5% upregulated in liver function | 2 – 24 weeks | Metabolic idiosyncrasy | 25 to 200 | (Lucena et al., 2003) (Hautekeete et al., 1998) | |

| Fluoxetine | Hepatocellular, cholestasis | C | 0.5% upregulated in liver function | 2 – 12 weeks | Metabolic idiosyncrasy | 10 to 90 | (Johnston and Wheeler, 1997), (Cosme et al., 1996) | |

| Norfluoxetine | Hepatocellular, cholestasis | C | NA | NA | Metabolic idiosyncrasy | NA | (Cosme et al., 1996; Johnston and Wheeler, 1997) | |

| Citalopram and Escitalopram | Cholestasis | C | 30-fold increase of ALT | 2 – 10 weeks | N/A | 20 to 40 | (López-Torres et al., 2004), (Sánchez et al., 2004) | |

| Fluvoxamine | Cholestasis | D | Rare | Few days | NA | 50 to 300 | (Todorović Vukotić et al., 2021), (Solomons et al., 2005) | |

| SNRIs | Atomoxetine | Hepatocellular | C | NA | 3 – 12 weeks | Metabolic idiosyncrasy | 10 to 100 | (Erdogan et al., 2011), (Hussaini and Farrington, 2014) |

| Venlafaxine | Cholestasis, hepatocellular | B | Rare | 1 – 3 months | Metabolic idiosyncrasy | 25 to 225 | (Park and Ishino, 2013; Phillips, 2017; Fang et al., 2021) | |

| Desvenlafaxine | Cholestasis, hepatocellular | E | Rare | 1 – 3 months | Metabolic idiosyncrasy | 25 to 100 | (Park and Ishino, 2013; Phillips, 2017; Fang et al., 2021) | |

| Agomelatine | Hepatocellular | C | Rare | NA | Metabolic idiosyncrasy | 25 to 50 | (Liu et al., 2016) | |

| Duloxetine | Hepatocellular, cholestasis | B | High | 1 – 6 months | Metabolic idiosyncrasy | 40 to 120 | (Qin et al., 2022a; Qin et al., 2022b) (Qin et al., 2022a; Qin et al., 2022b) |

|

| Milnacipran and Levo-milnacipran | NA | D | NA | NA | NA | 20 to120 | (Paris et al., 2009) | |

| NDRIs | Nomifensine | Cholestasis | A | Withdrawn | 20 days-8 weeks | Generalized hypersensitivity | 50 to 600 | (Salama and Mueller-Eckhardt, 1985), (Lee et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2019), (Yuan et al., 2020) |

| SARIs | Nefazodone | Hepatocellular, cholestasis | A | Withdrawn | 6 weeks – 8 months | Metabolic idiosyncrasy | 50 to 600 | (Thompson et al., 2016),(Aranda-Michel et al., 1999) |

| Trazodone | Hepatocellular, cholestasis | B | Withdrawn | 2 weeks – 6 months | Metabolic idiosyncrasy | 50 to 600 | (Wen et al., 2008), (Chu et al., 1983) |

NA, not available; A, well known cause; B, highly likely cause; C, possible cause; D, possible rare cause; E, unlikely cause.

From the LiverTox database and References; DILI, drug-induced liver injury.

2. Metabolic activation of antidepressants and reported adverse concerns

2.1. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

MAOIs, a large class of compounds inhibiting the activity of one or both monoamine oxidase enzymes (monoamine oxidase A, MAO-A, and monoamine oxidase B, MAO-B) were the first type of antidepressant developed. MAOIs elevate levels of monoamine neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine by preventing their inactivation (Bermingham and Blakely, 2016). Most are no longer extensively prescribed, having been replaced by tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which have better efficacy and fewer side effects (Ferguson, 2001). Currently, the MAOIs isocarboxazid, phenelzine, selegiline and tranylcypromine are still used to treat depression in clinical practice. These MAOIs can elevate serum levels of liver aminotransferase and have potential to cause clinical liver impairment (Ferguson, 2001). Several MAOIs bearing hydrazine moieties, such as iproniazid, iproclozide, mebanazine, nialamide, and phenoxypropazine, have been withdrawn from the market due to their hepatoxicity. The mechanism for RM formation by MAOIs of both the hydrazine and nonhydrazine classes are described below.

2.1.1. Iproniazid

Iproniazid is a non-selective, irreversible MAOI that was originally developed to treat tuberculosis, but was widely used as an antidepressant medication (Trenton and Currier, 2001). Hydrolysis of its amide bond by amidase produces acid 1 and N-isopropylhydrazine 2, a primary hepatotoxin in rats (Zimmerman et al., 1959; Nelson et al., 1976; Kalgutkar et al., 2002). Subsequent bioactivation of N-isopropylhydrazine 2 may result in the formation of reactive metabolites that covalently bind to liver proteins causing toxicity (Nelson et al., 1978; Kalgutkar et al., 2002). The proposed bioactivation of 2 is shown in Fig. 1: the P450 catalyzed N-hydroxylation of 2 forms N-isopropyl-N-hydroxyhydrazine intermediate 3, which eliminates water to give N-isopropyldiazine 4; homolytic cleavage across tertiary diazine nitrogen and the secondary isopropyl carbon in 4 generates the N-isopropyldiazonium ion 5 and isopropyl radical 6, respectively, as reactive intermediates that may contribute to the adverse effects of iproniazid. P450 enzymes are reported to participate in iproniazid bioactivation, but the exact isoforms are still unknown (Kalgutkar et al., 2002).

Figure 1.

Bioactivation process for iproniazid.

Due to its potential to induce severe hepatic injury, iproniazid has been discontinued for clinical administration. Hepatotoxicity of this drug is defined by hepatic necrosis with serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels 10-fold over the ULN and jaundice in 1% of cases, occurring during the first 1 – 3 months of treatment and resulting in death of up to 20% of affected patients (Rosenblum et al., 1960). It is found that N-isopropylhydrazine 4, an active metabolite of iproniazid (a rat hepatotoxin), can covalently bind to hepatic tissue and macromolecules and increase hepatic necrosis (Kalgutkar et al., 2002). However, the roles of RM in the liver injury caused by iproniazid in human subjects are still unclear.

2.1.2. Selegiline

Selegiline is a selective and irreversible inhibitor of MAO-B that increases levels of dopamine in the brain (Fowler et al., 2015) and is used for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). Selegiline is bioactivated by CYP2B6 to form a reactive intermediate that is detected as the GSH trapped adduct 10, whose formation is NADPH-dependent (Shin, 1997; Sridar et al., 2012). As shown in Fig. 2, the mechanism for the formation of the protein- (or GSH-) adduct 9 (or 10) involves initial hydroxylation of selegiline to 7, followed by oxygenation of the ethynyl group to generate the reactive ketene intermediate 8 (Sridar et al., 2012). The ketene reacts with GSH or a nucleophilic group on protein to form adducts. Selegiline was also discovered to be a mechanism-based inactivator of CYP2B6 (Sridar et al., 2012), and its mechanism-based inhibition of CYP2B6 can have major neuropsycho-pharmacological consequences for patients with schizophrenia (Shin, 1997; Sridar et al., 2012). This drug carries a black box warning for increased risk of suicide (Friedman and Leon, 2007).

Figure 2.

The bioactivation pathway of selegiline to the reactive intermediate trapped with glutathione (GSH).

Selegiline has been documented to result in elevated serum levels of liver enzymes in as many as 40% of patients receiving long-term treatment (Lee and Chen, 2007). Typically, these abnormalities are mild and resolve on their own, and it is important to note that selegiline has not been linked to cases of clinically evident acute liver injury. However, in some cases, symptoms persist with continued treatment and may necessitate the discontinuation of the drug. The role of reactive metabolites in selegiline hepatoxicity is still not clear yet (Friedman and Leon, 2007).

2.1.3. Isocarboxazid

Isocarboxazid is a non-selective, irreversible MAOI that is used to treat severe depression by increasing the levels of serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, melatonin, and phenethylamine in the brain (Volz and Gleiter, 1998). Isocarboxazid is hydrolyzed to benzylhydrazine 11 in vitro by carboxylesterase (Hosokawa and Satoh, 1988). Benzylhydrazine can react with pyridoxal to form a new hydrazine that inhibits pyridoxal kinase, as shown in Fig. 3. This prevents the cellular activation of pyridoxal to pyridoxal 5’-phosphate (PLP), thereby inhibiting numerous enzymatic reactions that depend on PLP as a cofactor (Larsen et al., 2015). The urinary hippurate 14 was detected in rats treated with isocarboxazid, indicating that benzylhydrazine can be metabolized to benzaldehyde 12, which is converted to benzoic acid 13 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Isocarboxazid metabolism and aldehyde formation. PLP, pyridoxal 5’-phosphate.

Isocarboxazid may lead to transient increases in serum aminotransferase levels in certain patients, but there have been no direct links established between isocarboxazid and instances of drug-induced liver injury. This medication has been employed rarely in clinical practice. The possible explanation for the rise in serum aminotransferases might involve the creation of hazardous intermediates, including hydrazine and benzaldehyde. Nevertheless, the exact mechanism remains undetermined.

2.1.4. Phenelzine

Phenelzine, a non-selective and irreversible MAOI of the hydrazine class, is mainly used as an antidepressant and anxiolytic. Phenelzine is among the limited number of non-selective and irreversible MAOIs that continue to be widely used in clinical practice (Sidhu and Marwaha, 2023). A hydrazine moiety is present in phenelzine and its most active metabolite phenylethylidenehydrazine (PEH). As shown in Fig. 4, phenelzine can be metabolized to phenethyldiazene 15, which can convert to diazonium 16 or phenethyl radical 17, which can generate phenylacetaldehyde 18, which is further metabolized to benzaldehyde 19 (Hidalgo and Zamora, 2019). Although these intermediates were proposed to address the formation of aldehydes 18 and 19, they have not been directly identified.

Figure 4.

The bioactivation of phenelzine.

Phenelzine may lead to temporary elevations in serum aminotransferase levels in some patients (Friedrich et al., 2016). Additionally, there have been documented cases of acute, clinically evident liver injury associated with phenelzine. This acute hepatitis-like syndrome can be severe and, in some instances, even fatal. Instances of cholestatic liver injury have also been attributed to phenelzine (Bonkovsky et al., 1986; Gómez-Gil et al., 1996). While published cases of phenelzine-induced liver injury are relatively scarce, severe jaundice and fatalities stemming from liver injury have been reported to both the FDA and the drug manufacturer (Bonkovsky et al., 1986). Aldehydes are known to be toxic and the diazonium could react with adenine to form an adduct that modifies DNA and may cause the carcinogenicity. These reactive metabolites could be responsible for the adverse effects of phenelzine, including liver toxicity.

2.1.5. Tranylcypromine

Tranylcypromine, a second generation MAOI, is a competitive inhibitor with a long duration of action comparable to an irreversible inhibitor that may due to its high affinity for an enzyme (Chaurasiya and Leon, 2022). Paech et al. claimed that tranylcypromine has an irreversible inhibitory effect on MAO, suggesting an imine or aldehyde intermediate that can possibly bond covalently with MAO protein (Paech et al., 1980). Ganesan et al. explains that this MAOI binds as a suicide substrate in the active site of monoamine oxidase (MAO) or lysine specific demethylase (LSD), and then goes through strain-induced ring opening to produce a reactive radical cation 20 (Ganesan et al., 2019). This reactive intermediate irreversibly inhibits the enzyme by covalently combining with the flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) cofactor described in Fig. 5 (Romero et al., 2018; Ganesan et al., 2019). Despite these detailed hypotheses, no trapping records of this adduct have been reported.

Figure 5.

Reaction mechanism of tranylcypromine binding upon LSD or MAO active site that undergoes oxidation to generate a reactive cation 20 that can further covalently bind to FAD. FAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide.

Rare instances of acute, clinically evident liver injury have been linked to tranylcypromine. The typical time frame for clinical onset is between 1 to 4 months, and the most common pattern of serum enzyme elevation is hepatocellular. However, there have also been reports of cholestatic injury (Bandt and Hoffbauer, 1964). The precise mechanism responsible for the elevation of serum aminotransferases induced by tranylcypromine remains unknown. Tranylcypromine is not a hydrazine derivative like other nonselective MAOIs and appears to have a reduced risk of hepatotoxicity compared to phenelzine and isocarboxazid (Atkinson and Ditman, 1965; Volz and Gleiter, 1998; 2012c; 2016). Proposed formation of imine or aldehyde intermediate in Fig. 5 by this drug has been proposed to support covalent bonding with MAO proteins that may be related to hepatotoxicity (Paech et al., 1980; Ganesan et al., 2019).

2.2. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)

TCAs are a class of medications used primarily for the management of depression named after their chemical structures, as they contain three rings. TCAs are believed to act by inhibiting the reuptake of norephinephrine and serotonin (Gillman, 2007) and include amitriptyline, nortriptyline, imipramine, desipramine, clomipramine, amineptine, tianeptine, doxepin, protriptyline, trimipramine and amoxapine. These TCAs can transiently elevate the level of serum aminotransferase to differing extents, and with different patterns of hepatotoxicity. Rare clinically apparent acute liver injury has been reported (Voican et al., 2014). Here we review the metabolic activations of TCAs.

2.2.1. Amitriptyline and nortriptyline

Amitriptyline metabolism involves hydroxylation, N-dealkylation, N-oxidation and glucuronidation (Wen et al., 2008b). Formation of the dihydrodiol metabolite 22 is quite common in amitriptyline as detected and characterized in urine (Venkatakrishnan et al., 2001; Wen et al., 2008b). Metabolite 22 is formed by nucleophilic addition of water to the reactive amitriptyline-epoxide intermediate 21, which is generated by P450-catalyzed bioactivation of an aromatic ring of amitriptyline (Fig. 6). The epoxide can be trapped as GSH-adduct 23. If the epoxide reacts with free thiol groups on the critical cellular proteins to form adduct 24, it may cause the protein function to be lost or disturbed, and further lead to toxicological response (Fig. 6). Nortriptyline is a N-demethylated amitriptyline that can be bioactivated to epoxide intermediate 25, analogous to amitriptyline (Fig. 6). The formation of epoxide 25 is catalyzed by the same P450 isoforms that oxidize amitriptyline, and epoxide 25 is ring opened by water to form dihydrodiol metabolite 26, or trapped by GSH to yield GSH-adduct 27 (Polasek and Miners, 2008; Wen et al., 2008b). The epoxide produced from nortriptyline may also form protein adduct 28 (Fig. 6), leading to adverse effects. Additionally, in vitro studies suggest that amitriptyline is a dynamic competitive inhibitor of CYP2D6 (Favreau et al., 1999; Shin et al., 2002; Hara et al., 2005).

Figure 6.

Bioactivation pathways of amitriptyline and nortriptyline.

Although amitriptyline (and nortriptyline) are bioactivated by hepatic P450s oxidation to chemically reactive epoxides that could mediate toxicity (Breyer-Pfaff, 2004; Wen et al., 2008b), amitriptyline is by far the most prescribed TCA and the incidence of hepatotoxicity is low (Koff, 1995). Amitriptyline has been associated with rare but severe hepatic injury described as idiosyncratic toxicity (Morgan, 1969; Anderson and Henrikson, 1978; Danan et al., 1984; De Craemer et al., 1991), and there have been rare reports of amitriptyline-induced cholestasis that was clinically and histologically significant, occurring 24 days - 8 months after commencing amitriptyline at dosages of 30 – 150 mg daily (Morgan, 1969; Yon and Anuras, 1975; Lewis, 2000). The exact mechanism of this hepatoxicity still need to be further elucidated that relies on the relationship between drug administration and the onset of hepatotoxicity (Yon and Anuras, 1975; Wen et al., 2008b).

Formation of epoxides is also a possible reason for nortriptyline causing hepatoxicity, including hepatitis, in susceptible patients (Pedersen and Enevoldsen, 1996; Wen et al., 2008b). In vivo human studies on amitriptyline and nortriptyline demonstrated a link between hepatotoxicity and the reactive metabolite formation where potential downstream stable metabolites were derived from further processing of reactive metabolites (Prox and Breyer-Pfaff, 1987; Pedersen and Enevoldsen, 1996).

2.2.2. Imipramine, desipramine, clomipramine, and trimipramine.

Imipramine and its active metabolite desipramine are dihydro analogs of amitriptyline and nortriptyline, respectively (Figs. 6 and 7). Both imipramine and desipramine are metabolized by P450-mediated aromatic hydroxylation (Korobkova et al., 2012; Limban et al., 2018). CYP2D6 contributes to imipramine demethylation to form desipramine (an active metabolite), to N-oxidation, and to generation of chemically reactive metabolites (Zheng et al., 2007b; Wen and Fitch, 2009; Korobkova et al., 2012). In HLM, imipramine and desipramine give glutathione ethyl ester (GSH-EE) adducts, which indicate the formation of reactive metabolites (Figs. 7A and 7B) (Zheng et al., 2007a).

Figure 7.

Bioactivation of imipramine, desipramine, and clomipramine.

These reactive metabolites are proposed to be epoxides 29 and 31, which react with GSH-EE and eliminate water to generate the adducts 30 and 32 (Figs. 7A and 7B). Other work indicates that desipramine reactive metabolites may also react with DNA (Madrigal-Bujaidar et al., 2010).

The toxicity of imipramine can be decreased by replacing the hydrogen atom at position 2 of the benzazepine ring with an electron withdrawing chlorine atom (Fig. 7C); this compound is marketed as clomipramine (Masubuchi et al., 1996; Isobe et al., 2005; Limban et al., 2018). A clomipramine GSH adduct 34 does form in HLM incubations, likely via the proposed epoxide 33 (Zheng et al., 2007a), but at much lower levels than for imipramine. Trimipramine, or 2’-methylimipramine (Fig. 7D), is a derivative of imipramine with a methyl group added to its side chain (Lapierre, 1989) that is used to treat MDD as well as reactive depression and is considered an atypical or “second-generation” TCA. Its structural similarity to imipramine (Fig. 7A) suggests that it may give similar epoxides, but there is as yet no information on GSH or GSH ester adducts formed by trimipramine.

Imipramine was recognized as a causative agent of asymptomatic liver function abnormalities in around 20% of patients shortly after its clinical use (Klerman and Cole, 1965). Imipramine is linked primarily to cases of cholestatic liver damage, which usually manifests within the first two to three weeks of using the medication at recommended levels (Horst et al., 1980). Desipramine has also been responsible for causing severe hepatitis to fatal hepatic necrosis (Powell et al., 1968; Shaefer et al., 1990; Lucena et al., 2003). For both imipramine and desipramine, the production of reactive epoxides metabolites could be the cause of liver injury (Price et al., 1983) (Powell et al., 1968). Clomipramine gives rise to less reactive epoxide in vitro and shows less toxicity, supporting the inference that the reactive metabolites are an important risk factor. In clinical trials, trimipramine did not cause increased serum aminotransferase levels, and there have been no connections to cases of visibly evident acute liver injury so far (Remy et al., 1995). Further studies are required to determine the association of reactive metabolites and their toxicities.

2.2.3. Amineptine and tianeptine

Amineptine is an atypical antidepressant of the TCA family. Several instances of severe hepatotoxicity arose after the product was introduced to the market (Ricca Rosellini et al., 1990; Lazaros et al., 1996; Todorović Vukotić et al., 2021a). Geneve et al reported that amineptine is metabolized by P450s and forms NADPH-dependent microsomal covalent adducts, but the exact P450 isozymes were not identified (Geneve et al., 1987). The reactive metabolite produced from amineptine was thought to be epoxide 35 (Fig. 8), since addition of an epoxide hydrolase inhibitor to reactions in HLM increases the degree of amineptine adduct formation (Geneve et al., 1987; Grislain et al., 1990).

Figure 8.

Epoxidation of amineptine and tianeptine.

Tianeptine, an analog of amineptine that replaces two carbons in the cycloheptanamine ring with N-methyl sulfonamide (Fig. 8), was mainly used for the treatment of MDD. Tianeptine appears to be less toxic in the clinic, although P450 bioactivation to a reactive arene oxide 36 does still occur (Larrey et al., 1990; Fromenty and Pessayre, 1995; Stepan et al., 2011). Thus, the sulfonamide group may play some role in decreasing toxicity. Structure-toxicity relationship studies of amineptine gives a possible explanation of reactive metabolite formation by P450 enzymes upon NADPH-dependent microsomal covalent binding, suggestive of a characteristic reactive epoxide hepatotoxicant of amineptine (Geneve et al., 1987). In addition, the heptanoic side chains of amineptine and tianeptine (Fig. 8) can be metabolized via mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation (Todorović Vukotić et al., 2021a). Medium and short-chain natural fatty acids accumulation was observed due to heptanoic side chains competing β-oxidation with medium and short-chain fatty acids (Schönfeld and Wojtczak, 2016).

2.2.4. Doxepin

Doxepin is a TCA that acts as a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and is used to treat anxiety or depression, as well as insomnia (Weber et al., 2010). Doxepin is converted to the active metabolite desmethyldoxepin by N-demethylation and to other inactive metabolites in liver (Ziegler et al., 1978), and CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 are the main enzymes involved in this metabolism, with CYP1A2 and CYP2C9 involved to a lesser extent (Kirchheiner et al., 2002; Gronewold et al., 2009; Weber et al., 2010). Doxepin was discovered to be an in vivo CYP2D6 inhibitor (Szewczuk-Bogusławska et al., 2004; Gronewold et al., 2009). Doxepin differs from imipramine only by substitution of an oxygen for a methylene, and as shown in Fig. 9 has the potential to be converted to an analogous epoxide 37 by P450 enzymes, but no corresponding adducts have been reported to date.

Figure 9.

Proposed formation of epoxides of doxepin.

Elevated serum aminotransferase levels have been observed in as many as 16% of patients undergoing treatment for depression with doxepin (DeSanty and Amabile, 2007) (Voican et al., 2014). However, instances where these elevations exceed three times the upper limit of normal are rare. There have been reports of recurrent jaundice and significant aminotransferase elevations upon repeated exposure to doxepin (Keegan, 1993). In most cases, these elevations have been mild, and there have been no reported fatalities resulting from acute liver failure or chronic injury. Doxepin increases serum aminotransferase in the patients and the mechanism is still unknown. As it undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism, the formation of epoxides as proposed in Fig. 9 are one possible cause of liver injury associated with doxepin. The role of doxepin metabolism still needs to be elucidated (Gronewold et al., 2009).

2.2.5. Protriptyline

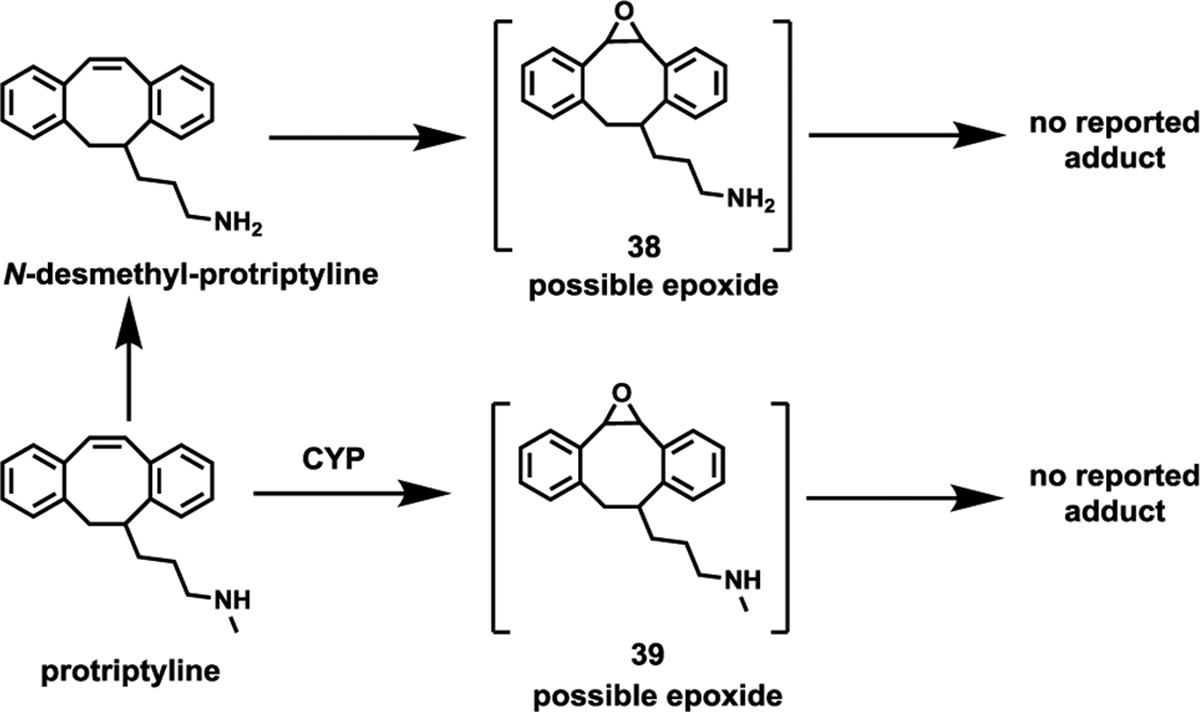

Protriptyline is a dibenzocycloheptadiene, with three fused rings and a side chain that make it structurally similar to N-dealkylated amitriptyline (Fig. 10) (Saef et al., 2022), which is known to bioactivate to epoxides. Epoxide metabolites 38 and 39 were identified in the urine of rats administered with 14C-labeled protryptyline (Fig. 10) (Hucker et al., 1975). However, adduct formation by protriptyline epoxides has not yet been reported. Protriptyline undergoes hepatic metabolism, and one possible cause of liver damage is the formation of hazardous reactive metabolic intermediates (Remy et al., 1995; 2012b).

Figure 10.

Possible epoxide formation by protriptyline.

The frequency of serum enzyme elevations occurring during protriptyline therapy has not been clearly established. Although rare cases of clinically evident acute liver injury have been documented in patients using tricyclic antidepressants, there are no reported cases directly associated with protriptyline (Remy et al., 1995).

2.3. Tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCAs)

TeCAs are a group of antidepressants that were originally made available in the 1970s, are similar to or derived from TCAs, and have similar mechanisms of action (Voican et al., 2014). Amoxapine, mianserin, and mirtazapine are TeCAs frequently used in clinical practice (Hetrick et al., 2021). Mianserin has the potential to form reactive iminoquinone or iminium metabolites.

2.3.1. Amoxapine

Amoxapine is a dibenzoxazepine and a demethylated metabolite of the neuroleptic loxapine (Ban et al., 1980). It shows strong parallels to imipramine in animal pharmacological studies, and undergoes N-oxidation as well as epoxidation to give chemically reactive 40 as proposed in Fig. 11 (Wong et al., 2012). No trapping screens have yet been performed, but CYP2D6 is the predominant liver enzyme that metabolizes amoxapine. (Abbas and Marwaha, 2022).

Figure 11.

Bioactivation of amoxapine.

The first instance of hepatotoxicity related to amoxapine was an acute cytolytic hepatitis, characterized by high level of serum alanine liver transferase (up to 24-fold the upper normal limit) (Patterson, 1987; Manapany et al., 1993). Amoxapine metabolites are a potential cause of this toxicity (Wong et al., 2012), but the exact mechanism of hepatotoxicity still needs to be determined.

2.3.2. Mianserin

Mianserin is a TeCA used to treat depression and anxiety that strongly stimulates norepinephrine release (Olianas et al., 2012). The major metabolites identified from human urine are 8-hydroxymianserin 41 and N-desmethyl-mianserin 43, whose formation are mediated by CYP2D6 and CYP1A2 (Kalgutkar, 2017). Metabolites 41 and 43 can by further oxidized by CYP2D6 to generate reactive iminoquinones 42 and 44, as shown in Fig. 12A; these can be trapped with GSH-EE to form adducts 44 and 45 (Kitteringham et al., 1988; Riley et al., 1990; Wen and Fitch, 2009). Cyano-mianserin adducts detected in HLM led to the prospoal that iminium intermediates 47, 48, and 50 form, as shown in Fig. 12B. In addition, reactive iminium species 51 and its corresponding cyano adduct 52 have been observed in incubations of mianserin with human neutrophils or with horseradish peroxidase/H2O2 (Iverson et al., 2002; Kalgutkar, 2017). Koyama et al. determined that hydroxylation of both enantiomers of mianserin was mediated by CYP2D6, while N-demethylation and N-oxidation were catalyzed by CYP1A2 (Koyama et al., 1996). CYP3A is involved in both pathways to a certain extent (Koyama et al., 1996).

Figure 12.

Proposed bioactivation of mianserin. A, Formation of iminoquinone, B, formation of iminium GSH-EE, GSH-ethyl ester; CN, cyanide

Metabolism of radiolabeled mianserin in HLMs results in the irreversible incorporation of radiolabel into microsomal protein (Kitteringham et al., 1988; Riley et al., 1988; Riley et al., 1990). Several studies indicate that formation of iminium is the putative pathway towards hepatotoxicity (Roberts et al., 1993). Interestingly, replacing the hydrogen atom at mianserin position 14b (Fig. 12B) with a methyl group significantly decreases cytotoxicity; since this modification blocks formation of the iminium species but not the imoquinone, iminium formation is inferred to be the main cause of toxicity (Kalgutkar et al., 2002).

2.4. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

SSRIs are a category of antidepressant drugs that increase serotonin levels in the brain by blocking its reuptake in synaptic clefts (Lee and Chen, 2010). Notably, SSRIs are highly selective and have minimal impact on the reuptake of norepinephrine or other neurotransmitters, resulting in a reduced risk of adverse effects compared to other antidepressant classes (Chu and Wadhwa, 2022). Today, SSRIs are among the most commonly prescribed antidepressants. The first-line medications for depression now include citalopram, escitalopram, fluvoxamine, sertraline, fluoxetine, and paroxetine (Lee and Chen, 2010). Paroxetine carries a risk of causing severe hepatotoxicity that may be linked to the formation of reactive metabolites.

2.4.1. Citalopram and escitalopram

Citalopram, marketed as a racemate, is one of the most extensively prescribed antidepressant worldwide (López-Torres et al., 2004; Sánchez et al., 2004). The pharmacological effects of citalopram are almost exclusively ascribed to the S-(+) enantiomer, named escitalopram, which is both safer and more effective (Hyttel et al., 1992). Metabolism of citalopram includes N-demethylation, with the formation of N-desmethylcitalopram 54, which is further N-demethylated to didesmethylcitalopram 55 (Fig. 13). Citalopram is mainly metabolized by CYP2C19 in the liver, but also by CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 (von Moltke et al., 1996). Studies in human liver also found that citalopram could be metabolized to citalopram acid 57, which suggests the presence of an aldehyde intermediate 56 (Rochat et al., 1998). MAOs are proposed to mediate aldehyde formation and CYP2C19 and AO are responsible for converting aldehyde to acid (Rochat et al., 1998; Tanum et al., 2010). Citalopram N-oxide 58 was also observed, and CYP2D6 mediates its formation.

Figure 13.

Proposed bioactivation of citalopram. AO, amine oxidase; MOA/MOB, monoamine oxidases A and B.

Citalopram may cause cholestasis as well as acute hepatic injury, and its hepatotoxicity may be due to reactive citalopram aldehydes (López-Torres et al., 2004; Sánchez et al., 2004; Todorović Vukotić et al., 2021a).. However, since the aldehyde can be readily converted to acid by AO as described above, aldehyde accumulation due to a deficiency (or inhibition) of AO could be a risk factor for citalopram induced liver injury. More work is required to determine the role of its bioactivation in it adverse effects.

2.4.2. Fluvoxamine

Fluvoxamine is extensively metabolized in the liver (Spigset et al., 2001) and eleven metabolites have been identified in urine (Perucca et al., 1994). Fluvoxamine acid, the major urinary metabolite (Perucca et al., 1994; Spigset et al., 2001), is generated by oxidative demethylation of the methoxy group by CYP2D6 to a fluvoxaminoalcohol intermediate that is converted by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH1A, ADH1B and ADH1C) to fluvoxamine aldehyde, and to the acid by AO (Spigset et al., 2001; Miura and Ohkubo, 2007). In vitro experiments indicate that CYP2D6 is the only CYP enzyme likely to carry out this process (Miura and Ohkubo, 2007). CYP1A2 can mediate substitution of the amino group with a hydroxyl to form 59 or removal of the entire ethanolamino group to form 60 (Perucca et al., 1994) (Spigset et al., 2001) (Fig. 14). These formation of 59 and 60 indicated the reactive aldehyde intermediates present during the metabolism of fluvoxamine.

Figure 14.

Proposed bioactivation of fluvoxamine.

A few instances of liver injury with marked elevation of serum liver enzymes accompanied by minimal or no jaundice have been reported in individuals using fluvoxamine (Solomons et al., 2005; Todorović Vukotić et al., 2021b), but there have been no documented cases of acute liver failure or long-term liver harm linked to fluvoxamine treatment. The rare and mild hepatotoxicity of fluvoxamine may be related to aldehyde intermediates in its metabolism, but the precise mechanism responsible for liver injury remains unclear.

2.4.3. Sertraline

Multiple P450 isoforms are responsible for the metabolism of sertraline. The principal pathway of metabolism is N-demethylation to desmethylsertraline 61 (Fig. 15). Several CYP enzymes in human microsomes and cDNA-expressed human P450 isoforms, including CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2B6, CYP2C19 and CYP3A4, contribute to sertraline N-demethylation. Among these five isoforms, CYP2D6 had the highest estimated intrinsic clearance, but it appears that CYP2C19 plays the most essential role in the human body, followed by CYP2B6 (DeVane et al., 2002). N-desmethylsertraline can be oxidatively deaminated in vitro by monoamine oxidases (MAOs) to form ketone 62 (Fig. 15), but this metabolic pathway has never been explored in vivo (Obach et al., 2005). There are no reports indicating that sertraline ketone is reactive or toxic. In addition to N-demethylation, sertraline can be metabolized to N-hydroxylamine 63 and further oxidized to nitroso species 64. This reaction may also occur for N-desmethylsertraline. The nitroso species can complex with heme in CYP3A4, resulting in inhibition of its catalytic activity (Masubuchi and Kawaguchi, 2013).

Figure 15.

In vitro metabolism of sertraline.

Rare instances of acute, clinically apparent episodes of liver injury with marked liver enzyme elevation with or without jaundice have been reported in patients on sertraline. The pattern of serum enzyme elevations has varied from hepatocellular to mixed and cholestatic (Hautekeete et al., 1998; Lucena et al., 2003). The mechanism by which sertraline causes liver injury is not known. The toxic nitroso species may be responsible for its liver toxicity.

2.4.4. Fluoxetine

Fluoxetine is extensively metabolized by the liver, primarily through the P450 system. CYP2D6 plays a pivotal role in the primary metabolic pathway that generates the active metabolite norfluoxetine (Lucena et al., 2003). Fluoxetine is a strong inhibitor of CYP2D6 (Deodhar and Rihani, 2021), and norfluoxetine is also a strong reversible or time-dependent CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 inhibitor, raising the possibility of clinically significant drug interactions (Cosme et al., 1996; Johnston and Wheeler, 1997). Previous studies showed that norfluoxetine can be further metabolized to the alcohol 66 and acid 67 (Johnston and Wheeler, 1997), implying the formation of intermediate aldehyde 65 as shown in Fig. 16, but the aldehyde has not been directly detected or trapped and needs to be further confirmed.

Figure 16.

Metabolic activation of fluoxetine.

The majority of patients who experience liver injury upon treatment with fluoxetine display a hepatocellular pattern of damage, but one patient has been reported to display cholestasis, and one instance involved autoimmune-like chronic hepatitis (Lucena et al., 2003). The mechanism behind this toxic impact appears to be metabolically mediated, and may be caused by reactive aldehyde, but the mechanism is not well characterized. Norfluoxetine has a primary amino group with the potential to produce toxic nitroso species; as discussed above for sertraline, these can be reactive. However, the mechanism of liver toxicity associated fluoxetine is as yet largely unknown.

2.4.5. Paroxetine

Paroxetine contains the 1,3-benzidioxole (methylenedioxyphenyl) structural alert (or toxicophore) and CYP2D6 mediates ring cleavage of 1, 3-benzidioxole to a toxic catechol reactive intermediate 68 (Fig. 17). Incubation of [3H]-paroxetine with HLM or S-9 fraction demonstrates that radioactive paroxetine covalently binds to macromolecules in an NADPH-dependent manner. In the presence of supplemented GSH, three sulfhydryl conjugates 70, 71, and 72 are formed in vitro. The proposed bioactivation pathways are shown in Fig. 17. Paroxetine is first metabolized to catechol 68 by CYP2D6. Metabolite 68 is further oxidized to the reactive O-quinone 69, which can react with either GSH to form adduct 72 or with proteins, which may lead to toxicity. Alternatively, 68 is O-methylated by catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) and further oxidized to other reactive O-quinones that form GSH adducts 70 and 71 (Zhao et al., 2007; Klopčič and Dolenc, 2019). These reactive metabolites may contribute to the paroxetine toxicity, but exact mechanism is still unknown. In addition, paroxetine is a potent inhibitor of human CYP2D6 activity (Bolton et al., 2000b; Klopčič and Dolenc, 2019).

Figure 17.

Paroxetine bioactivation and reactive metabolite formation in HLM and liver S9 fraction. COMT, catechol-O-methyltransferase.

Paroxetine has been linked to transient abnormalities in liver tests (Benbow and Gill, 1997; de Man, 1997). Four hepatocellular liver damage incidents have been documented, including one with biopsy-proven chronic active hepatitis (de Man, 1997), that may be related to formation of reactive catechol intermediates through mechanism-based inactivation of P450s. In vitro paroxetine studies have shown possible hepatotoxicity response upon covalent binding to HLMs and to S-9 proteins (Bolton et al., 2000b; Klopčič and Dolenc, 2019). However, the exact mechanism still to be explored.

2.5. Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

SNRIs are a class of antidepressant drugs used for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), chronic neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia syndrome, and menopausal symptoms. They are very effective and may have a lower risk of toxicity than TCAs (Lee and Chen, 2010). Agomelatine, atomoxetine, desvenlafaxine, venlafaxine, and duloxetine are examples of SNRIs that can cause severe adverse events that may be related to reactive metabolite formation. Reactive metabolite formation has not been reported for the SNRIs levomilnacipran and milnacipran (Paris et al., 2009; 2012a).

2.5.1. Agomelatine

Agomelatine, an analog of melatonin, is widely used in therapy of MDD in adults. Our previous studies of agomelatine metabolism in HLM revealed GSH-trapped adducts and two semicarbazide-trapped aldehydes, and three N-acetyl cysteine conjugated agomelatine adducts in mouse urine and feces (Liu et al., 2016). CYP1A2 and CYP3A4 are primary enzymes contributing to the formation of GSH adducts and hydrazones, and formation of two dihydrodiols via epoxide intermediates are mediated by CYP1A2 both in vitro and in vivo, in schemes shown in Fig. 18 (Liu et al., 2016). In HLM, agomelatine is readily converted to demethylhydroxyl-agomelatine 73, which undergoes epoxidation and GSH conjugation to form adduct 74. Hydroxylated agomelatine can also undergo epoxidation and GSH conjugation to form adduct 75. Agomelatine or demethylagomelatine are oxidized to hydroxylagomelatine or demethylhydroxyl-agomelatine 73, respectively, which give reactive aldehydes 78 and 79 as inferred from the detection of semicarbazones 80 and 81 in the presence of semicarbazide. In mice, agomelatine is oxidized in the liver to epoxides that react with GSH to form adduct 76 after loss of H2O. Further metabolism to NAc adduct 77 occurs via an array of biotransformation steps. However, further studies need to be carried out to understand the role of reactive metabolites in agomelatine-related adverse effects, and P450 inactivation.

Figure 18.

Bioactivation of agomelatine.

Agomelatine does pose a risk of liver injury (Freiesleben and Furczyk, 2015), and the mechanism underlying agomelatine-induced liver injury appears to be idiosyncratic (Gahr et al., 2013). The injury can be hepatocellular, cholestatic or mixed (Hussaini and Farrington, 2007). Reactive metabolites may cause liver toxicity via covalent modifications of biomacromolecules (Casini et al., 1985; Heijne et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2016a), but the exact mechanism is still unknown.

2.5.2. Atomoxetine

Atomoxetine is used mainly to treat ADHD. The bioactivation of atomoxetine to form aldehydes and quinones has been reported previously by our and other groups (MacKenzie et al., 2020; You et al., 2021). Atomoxetine is first oxidized to hydroxyl-atomoxetines 82 and 83 by CYP2B6 and CYP2D6. Metabolite 82 is oxidized to reactive aldehyde 84, as inferred by the detection of O-methyloxime 87 in the presence of methoxyamine (MacKenzie et al., 2020). Similarly, metabolite 85 is oxidized to reactive aldehyde 86, as inferred by the detection of O-methyl oxime 88 (MacKenzie et al., 2020). Formation of aldehydes was confirmed in human, mouse and rat liver microsomes (HLM, MLM, and RLM) using methoxyamine as trapping agent (Fig. 19A), and CYP2C8 and CYP2B6 are the major enzymes involved in these bioactivations (MacKenzie et al., 2020). Notably, CYP2B6 is involved in the synthesis of 2-hydroxyatomoxetine 82, which is a precursor to the aldehydes (Fig. 19). You et al. identified reactive metabolite para-toluquinone 90 from atomoxetine in vitro and in vivo (You et al., 2021). The metabolic activation of atomoxetine was dominated by CYP2D6. RLM and HLM supplemented with atomoxetine revealed the formation of 2-methylbenzene-1,4-diol 89 by CYP2D6-mediated O-dealkylation and oxidation. Diol 89 was further oxidized to p-toluquinone 90, which was trapped by GSH in vitro (You et al., 2021) (Fig. 19B).

Figure 19.

Atomoxetine bioactivation.

The typical pattern of liver injury in patients exhibiting when treated with atomoxetine was hepatocellular with marked increases in serum aminotransferase levels and clinical features that resembled acute viral hepatitis. Most cases have been self-limited, but instances of acute liver failure sometimes requiring emergency liver transplantation have been reported; several patients with acute injury had antinuclear antibody and at least one patient had other features that resembled autoimmune hepatitis. Multiple adverse effects associated with atomoxetine have been reported including severe liver injuries with clinical features that resembled acute viral hepatitis. Reactive metabolite in the form of aldehyde intermediate generated from atomoxetine may be involved in its induced liver toxicity (Erdogan et al., 2011; Hussaini and Farrington, 2014). The quinone metabolic products of atomoxetine are electrophilic agents that may induce toxicity by covalent modification of DNA and protein in liver (Bolton et al., 2000a). More studies are required to determine the role of reactive metabolite in atomoxetine hepatotoxicity.

2.5.3. Venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine

Venlafaxine is widely used as an antidepressant. Desvenlafaxine 93, the major bioactive metabolite of venlafaxine, has been marketed separately, and has better tolerance than venlafaxine (Chen et al., 2020). CYP2D6 mediates O-demethylation to desvenlafaxine 93 whereas CYP3A4 mediates formation of N-desmethylvenlafaxine 94 (Fig. 20). The para-alkylphenol moiety of desvenlafaxine is oxidized by CYP3A4 in HLM and MLM to the quinone methide 95, which has also been detected in the bile of rats treated with venlafaxine (Li et al., 2021). Quinone methide 95 can react with GSH or cysteine to produce adducts 96 or 97, respectively. The GSH adduct is further degraded to 99. Quinone methide 95 can be conjugated with cysteinyl sulfhydryl groups on proteins in vivo, as indicated by the dose-dependent detection of cysteine adduct 98 in acid-hydrolysed liver from mice treated with venlafaxine or desvenlafaxine. These findings may shed on new insights on the relationship between hepatotoxicity of venlafaxine and its metabolic activation.

Figure 20.

Venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine bioactivation pathways.

Venlafaxine therapy transiently elevates serum aminotransferase levels, with patterns that vary from cholestatic to hepatocellular, and in rare instances can cause acute liver injury (Park and Ishino, 2013; Phillips, 2017; Fang et al., 2021). The quinone methide intermediate from in vitro and in vivo venlafaxine metabolism may contribute to its liver toxicity as it is highly reactive to GSH and cysteine residues of hepatic protein. The proposed metabolic activation process of venlafaxine and its active metabolite desvenlafaxine is suggestive to metabolic activation-hepatotoxicity relationship described in Fig. 20. Venlafaxine does not inhibit P450 enzymes and so the possibility of idiosyncratic toxicity because of diminished drug metabolism has been excluded (von Moltke et al., 1996; Owen and Nemeroff, 1998; Li et al., 2021).

2.5.4. Duloxetine

Duloxetine (DLX) is widely used for the treatment of MDD. Wu et al. revealed various GSH-DLX conjugates in HLM supplemented with NADPH and GSH (Wu et al., 2010). Our recent study revealed N-acetyl cysteine (NAc) adducts and GSH-DLX adducts both in vitro and in vivo (Qin et al., 2022a). We proposed that the 1-naphthol moiety of DLX is oxidized to generate epoxides 100 that give GSH adducts 101 or are hydrolyzed to dihydrodiols (Fig. 21). The GSH adducts of DLX are degraded to NAc adducts 102 or 103 in a series of reactions (Qin et al., 2022a). The generation of 1-naphthol sulfate-NAc adduct 105 requires multiple steps, including the formation of naphthol sulfate 104, and the epoxidated naphthol sulfate reacts with GSH and is further degraded to NAc-naphthol-1-sulfate 105. CYP1A2 and CYP2D6 are primary enzymes contributing to the duloxetine metabolism that leads to formation of GSH adducts.

Figure 21.

Proposed metabolic bioactivation pathways of duloxetine.

Rare and serious liver injury associated with duloxetine has been reported (Qin et al., 2022a; Qin et al., 2022b). The typical pattern of serum levels of liver enzymes is primarily hepatocellular; however, mixed and cholestatic patterns have also been documented. The naphthyl group and thiophene ring in DLX are known toxicophores. Formation of reactive metabolites could potentially provide information regarding the nature of time dependent inhibition of P450 caused by duloxetine as well as mechanism of clinically observed hepatotoxicity (McIntyre et al., 2008; Chan et al., 2011). However, our recent unpublished findings suggest that blocking DLX metabolism increases its toxicity in vitro and in vivo, indicating that reactive metabolites from DLX may play a minor role in its liver toxicity. Thus, more extensive studies are essential for determining the mechanism(s) of duloxetine hepatotoxicity.

2.6. Norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs)

NDRIs work by blocking norepinephrine and dopamine transporters, which results in higher dopamine concentrations (Hillhouse and Porter, 2015). NDRIs have been used for the treatment of depression and ADHD, and for the management of Parkinson’s disease (Hetrick et al., 2021). Nomifensine is an effective NDRI antidepressant that was withdrawn by U.S. FDA because of the risk of haemolytic anaemia, liver and kidney toxicity (Pechulis et al., 2012). The bioactivation of nomifensine has been reported, and the proposed mechanism for the formation reactive metabolites is described below.

2.6.1. Nomifensine

Nomifensine is a tetrahydroisoquinoline derivative that contains aniline and arene groups considered to be potential toxicophores (Yu et al., 2010b; Klopčič and Dolenc, 2019). Nomifensine undergoes oxidative bioactivation of the aniline nitrogen to form N-hydroxylamine 106, which is converted to the more reactive nomifensine nitrosoamine 107. The nitrosoamine reacts with GSH to form an unstable mercaptal 108 that rearranges to form the GSH-based conjugate sulfinamide 109. (Alternative mechanisms of activation of the N-hydroxylamine may happen in vivo: sulfation or acetylation of the hydroxylamine would give N-O-sulfate or N-O-acetyl adducts that are excellent leaving groups, the elimination of which might lead to the generation of highly reactive nitrenium or carbonium ions, but these have not been reported as yet). Another bioactivation pathway involves aromatic oxidation para to the aniline nitrogen to form 110 and then the quinone imine 111 that can be captured by GSH to form adduct 112 (Fig. 22). An anti-CYP2B6 antibody inhibits by 63% the formation of N-hydroxylamine, indicating that CYP2B6 is the major but not sole enzyme responsible for its formation (Yu et al., 2010a).

Figure 22.

Bioactivation pathways of nomifensine in liver microsomes.

Nomifensine was withdrawn from the market because of harmful side effects including hemolytic anemia, liver, and kidney toxicity (Salama and Mueller-Eckhardt, 1985). Nomifensine can cause hepatitis (Lee et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2019) and cholestasis (Yuan et al., 2020). Reactive metabolites such as nitrenium ion or quinone imine may lead to hepatotoxicity (Obach and Dalvie, 2006) but the exact relationship between bioactivation and liver toxicity remains unclear.

2.7. Serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor (SARI)

SARIs are antidepressant medications approved for use in treating MDD that are also used off-label for treating insomnia and anxiety. They function by inhibiting serotonin receptors such as 5-HT2A and preventing the reuptake of serotonin, norepinephrine, or dopamine. Nefazodone and trazodone are SARIs that block serotonin 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors and inhibit serotonin reuptake (2013); they are linked with formation of reactive metabolites and acute liver damage (Stepan et al., 2011).

2.7.1. Nefazodone

Nefazodone is used in treating depression, panic disorder and aggressive behavior. Nefazodone undergoes a CYP3A4-catalyzed aromatic hydroxylation para to the piperazinyl nitrogen to give the major circulating metabolite hydroxynefazodone 113, which contain the well-known reactive toxicophore para-hydroxyaniline moiety. Oxidation of 113 leads to the formation of quinone imine 114 or benzoquinone 115, which can react with GSH to generate adducts 116 and 117 (Fig. 23) (Kalgutkar et al., 2005b; Bauman et al., 2008). In addition, oxidation alpha to either piperazine nitrogen generates a reactive iminium ion intermediate (Fig. 23) that is trapped by cyanide ions in rat liver microsomes (Bauman et al., 2008)(Argoti et al., 2005). Nefazodone is also a strong inhibitor of CYP3A4 and a moderate to weak inhibitor of CYP2D6 and CYP2C, and the nefazodone bioactivation pathway catalyzed by CYP3A4 can lead to time dependent inhibition.

Figure 23.

Characterized bioactivation pathways for nefazodone.

Nefazodone causes clinically apparent liver injury, some of which were fatal. Liver biopsy usually demonstrated an acute hepatitis with cholestasis and variable degrees of centrolobular necrosis. Nefazodone has a “black box” warning for hepatotoxicity and has been withdrawn from use in many countries. Formation of reactive metabolites is proposed to be the prime cause of severe hepatotoxicity by this drug. Apart from the demonstrated in vitro bioactivation, nefazodone binds to liver protein as a result of reactive metabolite formation. Nefazodone binds irreversibly to HLM proteins, S9 fractions and hepatocytes prior to causing hepatotoxicity in patients observed in biliary and mitochondrial assays (Aranda-Michel et al., 1999; Usui et al., 2009; Thompson et al., 2016). The liver toxicity of nefazodone can potentially be attributed to reactive metabolites, though the precise mechanism behind nefazodone toxicity remains elusive.

2.7.2. Trazodone

Trazodone is used in therapy of depression, panic disorder and aggressive behavior. As for nefazodone, the 3-chlorophenyl piperazine ring in trazodone can undergo hydroxylation mediated by CYP3A4 to generate para-hydroxyltrazodone, which is a major metabolite in urine (Jauch et al., 1976). As shown in Fig. 24, further oxidation forms reactive quinone imine 118. P450-mediated N-dealkylation/hydroxylation of trazodone yields the p-hydroxy-m-chlorophenylpiperazine 120, and subsequent bioactivation produces p-hydroxy m-chlorophenylpiperazine quinone imine 121 (Wen et al., 2008a). Reactive metabolites 118 and 121 readily form GSH adducts 119 and 122, respectively (Wen et al., 2008a). Another bioactivation of trazodone on the pyridine ring leads to the highly reactive epoxide 123, which gives GSH conjugate 124 or dihydrodiol 125 upon epoxide ring opening by GSH or water. Alpha-oxidation at the piperazine nitrogens of trazodone could lead to the formation of a reactive iminium ion intermediate, as discussed above for nefazodone, but there is currently no documented report for such iminium formation.

Figure 24.

CYP3A4 mediated metabolism and bioactivation pathways of trazodone.

Trazodone therapy has been linked to clinically apparent acute liver injury (Rettman and McClintock, 2001; Wen et al., 2008a). At least a dozen cases of acute liver injury, characterized by significant elevations in liver enzymes with or without jaundice, have been documented in individuals taking trazodone. The elevation pattern of serum enzymes typically presents as hepatocellular, although mixed and cholestatic forms have also been observed (Chu et al., 1983; Wen et al., 2008a). Previous studies indicated that reactive metabolites of trazodone can collapse the mitochondrial membrane potential leading to cell death (Dykens et al., 2008). The mechanism by which trazodone causes liver injury is not known, but trazodone hepatotoxicity may be mediated by reactive intermediates of its metabolism (Taziki et al., 2013).

3. Discussion

Antidepressant-induced liver injury can have grave consequences, potentially leading to severe liver failure or even death. Traditional antidepressants, including MAOIs, TCAs, and TeCAs, carry a higher risk of hepatotoxicity compared to modern SSRIs (Voican et al., 2014). Patient data indicates that approximately 0.5% to 3% of individuals may experience elevated serum aminotransferase levels and hepatotoxicity, particularly among the elderly and those with polypharmacy (Voican et al., 2014). Consequently, mitigating the risk of DILI associated with antidepressants is both a clinical and pharmaceutical priority. Understanding the mechanisms of the underlying hepatotoxicity could enable us to predict, prevent, and manage these adverse effects. It is widely acknowledged that reactive metabolites resulting from drug metabolism may play a pivotal role in DILI. This hypothesis is supported by evidence that blocking the formation of these reactive metabolites can reduce liver toxicity (Stepan et al., 2011; Kalgutkar and Dalvie, 2015; Paludetto et al., 2020). For instance, a strategic modification of nefazodone, which contains metabolically labile chloro-phenyl and phenoxy groups prone to reactive metabolite formation, results in vilazodone, a non-reactive metabolic form of nefazodone (Limban et al., 2018). Another approach to mitigate toxicity issues involves reducing electronic density, as demonstrated by the transformation of imipramine into clomipramine through the replacement of a hydrogen atom with an electron-attracting chlorine atom (Limban et al., 2018). Nevertheless, certain drugs that generate reactive metabolites, including duloxetine (data not published), show increased liver toxicity when their metabolism is blocked by P450 knockout or by chemical inhibition, suggesting that in at least some cases reactive metabolites are not the cause of these adverse effects. It must be noted that false negatives can occur in trapping assays of reactive metabolites, and this can obscure possible sources of toxicity. For instance, if a reactive metabolite reacts preferentially with other cellular nucleophiles instead of GSH, a study may incorrectly infer from the lack of GSH adducts that reactive metabolites are not made. Thus, while any given trapping assay is a valuable tool in the detection of reactive metabolites, their results must be interpreted with an understanding of the assay limitations and potential for false positives and negatives. This requires a combination of careful experimental design, use of complementary methods, and expert analysis.

The reactive metabolites associated with the metabolism of antidepressants mediated by P450 oxidation or other enzymes are discussed in detail. Table 1 summarizes the types of reactive metabolites, (e.g., quinones, epoxides, arene oxides), trapping agents, and the enzymes involved in their formation. Table 2 provides comprehensive information concerning antidepressant induced liver toxicity, including injury types, liver toxicity score, incidence, dosage, DILI latency, and possible reaction mechanisms that may be involved in toxicity. Presently, there is no definitive clinical data for reactive metabolite-forming antidepressants that can pinpoint the exact cause of hepatotoxicity. Therefore, it is essential to understand alternative metabolic pathways and detoxification mechanisms, which may vary based on daily dose and drug-metabolizing enzyme responses, to mitigate the risks of toxicity (Teo et al., 2015).

In summary, while the exact roles of reactive metabolites in antidepressant-induced liver injury remain unclear, some evidence suggests a close association between reactive metabolites and their toxicity, as seen in mianserin. Additionally, nefazodone, nomifensine, trazodone, and mianserin, known for their production of reactive metabolites, were selectively withdrawn from the market due to their frequent association with severe hepatotoxicity (Riley et al., 1990; Obach and Dalvie, 2006; Dykens et al., 2008; Wen et al., 2008a; Thompson et al., 2016). In our review of 34 antidepressants, we found that 5 of these drugs had no reports of hepatotoxicity (Fig. 25A), and among these, 2 were observed to form detectable levels of reactive metabolites (Fig. 25B). Reports of hepatocellular injury were linked to 7 drugs, and 5 of these have been shown to form reactive metabolites. Mixed injuries, combining hepatocellular injury and cholestasis, were associated with 18 drugs, constituting 53% of the drugs reviewed; 12 of these could form reactive metabolites. Clinical reports also described cholestasis+steatosis and cholestasis+hepatitis in 2 drugs each, all of which could form reactive metabolites. Among 29 drugs with reported liver toxicity, 21 (or 72%) could form reactive metabolites. Although the direct connection between reactive metabolites and DILI remains unclear, and may be partly obscured by false negatives in trapping assays, minimizing the risk of chemically reactive metabolite formation is still a promising approach in preclinical drug optimization (Brink et al., 2017; Norman, 2020).

Figure 25.

Injury pattern profile (A) and potential link between RMs and DILI associated with antidepressants (B). AD, antidepressant; RM, reactive metabolites.

To date, there has been a dearth of comprehensive assessments concerning the mechanisms through which reactive species of antidepressants trigger adverse toxic events. However, recent advancements in in silico, in vitro, and in vivo models have provided investigators in this field with enhanced tools to elucidate reactive metabolite involvement and the underlying toxicity in both human and mouse models (Choudhury et al., 2017; Ly et al., 2017; Bissig et al., 2018). Overall, a comprehensive understanding of the metabolic pathways can mitigate adverse drug-drug interactions caused by elevated reactive metabolite formation. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the current state of knowledge on antidepressant bioactivation, the metabolizing enzymes responsible for reactive metabolite formation, and their potential implication in hepatotoxicity. Reactive metabolites have been also reported implicated in other adverse effects associated with antidepressants (e.g., genotoxicity and agranulocytosis) beyond DILI. Further addressing these connections could provide deeper insights into the overall impact of these molecules on human health and would certainly be a valuable addition to the findings in this review. This information can be a valuable resource for medicinal chemists, toxicologists, and clinicians engaged in the fields of antidepressant development, toxicity, and depression treatment.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. The potential structural alerts highlighted in red for RM formation of antidepressants.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney (R01-DK121970) to Dr. Feng Li.

Abbreviations:

- TCAs

tricyclic antidepressants

- TeCAs

tetracyclic antidepressants

- SARIs

serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors

- MAOIs

monoamine oxidase inhibitors

- SSRIs

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

- SNRIs

serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

- NDRI

norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitors

- RM

reactive metabolite

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- DDI

drug-drug interactions

- DILI

drug induced liver injury

- HLM

human liver microsomes

- MLM

mouse liver microsomes

- RLM

rat liver microsomes

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

- P450

cytochrome P450

- GSH

glutathione

- GSH-EE

glutathione ethyl ester

- KCN

potassium cyanide

- NAc

N-acetylcysteine

- COMT

catechol-O-methyltransferase

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, reduced

- HRP

horse radish peroxidase

- AO

aldehyde oxidase

- CNS

central nervous system

- MAO

monoamine oxidase

- LSD

lysine specific demethylase

- FAD

flavin adenine dinucleotide

- MDD

major depressive disorder

- ADHD

attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None

References

- (2012a) Milnacipran, in: LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda (MD). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2012b) Protriptyline, in: LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda (MD). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2012c) Tranylcypromine, in: LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda (MD). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2013) Serotonin Antagonist Reuptake Inhibitors (SARIs), in: Encyclopedia of Pain (Gebhart GF and Schmidt RF eds), pp 3471–3471, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg. [Google Scholar]

- (2016) Tranylcypromine, in: Meyler’s Side Effects of Drugs (Sixteenth Edition) (Aronson JK ed), pp 111–113, Elsevier, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas S and Marwaha R (2022) Amoxapine, in: StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copyright © 2022, StatPearls Publishing LLC., Treasure Island (FL). [Google Scholar]

- Allison R, Guraka A, Shawa IT, Tripathi G, Moritz W, and Kermanizadeh A (2023) Drug induced liver injury – a 2023 update. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B 26:442–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson BN and Henrikson IR (1978) Jaundice and eosinophilia associated with amitriptyline. J Clin Psychiatry 39:730–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade RJ, Lucena MI, Kaplowitz N, García-Muņoz B, Borraz Y, Pachkoria K, García-Cortés M, Fernández MC, Pelaez G, Rodrigo L, Durán JA, Costa J, Planas R, Barriocanal A, Guarner C, Romero-Gomez M, Muņoz-Yagüe T, Salmerón J, and Hidalgo R (2006) Outcome of acute idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury: Long-term follow-up in a hepatotoxicity registry. Hepatology 44:1581–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranda-Michel J, Koehler A, Bejarano PA, Poulos JE, Luxon BA, Khan CM, Ee LC, Balistreri WF, and Weber FL Jr., (1999) Nefazodone-induced liver failure: report of three cases. Ann Intern Med 130:285–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argikar UA, Mangold JB, and Harriman SP (2011) Strategies and chemical design approaches to reduce the potential for formation of reactive metabolic species. Curr Top Med Chem 11:419–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argoti D, Liang L, Conteh A, Chen L, Bershas D, Yu CP, Vouros P, and Yang E (2005) Cyanide trapping of iminium ion reactive intermediates followed by detection and structure identification using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Chem Res Toxicol 18:1537–1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson RM and Ditman KS (1965) Tranylcypromine: a review. Clin Pharmacol Ther 6:631–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attia SM (2010) Deleterious effects of reactive metabolites. Oxid Med Cell Longev 3:238–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillie TA and Rettie AE (2011) Role of biotransformation in drug-induced toxicity: influence of intra- and inter-species differences in drug metabolism. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 26:15–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban TA, Wilson WH, and McEvoy JP (1980) Amoxapine: a review of literature. Int Pharmacopsychiatry 15:166–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandt C and Hoffbauer FW (1964) Liver Injury Associated with Tranylcypromine Therapy. Jama 188:752–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]