Abstract

We uncovered an interaction between a choanoflagellate and alga, in which porphyran, a polysaccharide produced by the red alga Porphyra umbilicalis, induces multicellular development in the choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta. We first noticed this possible interaction when we tested the growth of S. rosetta in media that was steeped with P. umbilicalis as a nutritional source. Under those conditions, S. rosetta formed multicellular rosette colonies even in the absence of any bacterial species that can induce rosette development. In biochemical purifications, we identified porphyran, a extracellular polysaccharide produced by red algae, as the rosette inducing factor The response of S. rosetta to porphyran provides a biochemical insight for associations between choanoflagellates and algae that have been observed since the earliest descriptions of choanoflagellates. Moreover, this work provides complementary evidence to ecological and geochemical studies that show the profound impact algae have exerted on eukaryotes and their evolution, including a rise in algal productivity that coincided with the origin of animals, the closest living relatives of choanoflagellates.

Introduction:

The choanoflagellate, Salpingoeca rosetta, exemplifies the ability of unicellular eukaryotes to integrate complex environmental cues into their life history. Like many eukaryotes, nutrient availability drives life history transitions in S. rosetta1, including their sexual cycle2. Their main food source, bacteria, can produce another set of independent cues for choanoflagellates to detect, such as glycosyl lyases,4 that trigger mating and lipids5,6 that induce the development of multicellular rosettes through serial cell divisions (Fig. 1A). The roles of bacteria in the developmental transitions of choanoflagellates and their closest living relatives, the animals, have underscored that the evolution of both choanoflagellates and animals has been shaped by their intimate relationships with bacteria7–10.

Figure 1: Growth media prepared from Porphyra umbilicalis induces multicellular development of the choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta.

(A) S. rosetta senses environmental cues to develop into multicellular rosettes. Upon sensing lipids from the bacterium Algoriphagus machipongonensis, S. rosetta develops into rosettes through serial cell divisions while secreting an adhesive protein, Rosetteless (green), at the basal end of cells. Here we show that the red macroalga P. umbilicalis also induces rosette development.

(B) A medium prepared from the red alga P. umbilicalis induces rosette development. We optimized preparation of media enriched with P. umbilicalis at low (25°C) and high (80°C) temperatures (Fig. S1). We compared rosette induction with (+) or without (–) bacterial lipids in media prepared from P. umbilicalis, the green alga Ulva spp., and Cereal Grass. Rosette induction was quantified by counting the number of single swimmers and cells in rosettes for a total of 500 cells. Independent triplicates of those counts (black dots) are shown with their mean and standard deviation (lines). Only media prepared from P. umbilicalis at 80°C induced rosette development in the absence of bacterial lipids delivered in outer membrane vesicles from A. machipongonensis.

(C) S. rosetta secretes Rosetteless into the interior of multicellular rosettes induced with bacterial lipids or media enriched with P. umbilicalis. Immunofluorescent microscopy of rosettes induced with bacterial lipids or media enriched with P. umbilicalis visualizes the multicellular architecture of rosettes through an anti-alpha tubulin antibody (DM1A), which highlights, microtubules (grey), and phalloidin, which highlights filamentous actin (magenta). An antibody raised against Rosetteless (refs levin and rutaganira) shows the localization of this protein (green) in the interior of rosettes where the basal ends of cells meet. Scale bars denote 10 µm.

In marine environments, bacteria not only grow in the water column but also densely colonize surfaces of algae11–15. Macroalgae (also called seaweeds) harbor diverse microbial communities composed of both bacteria and microeukaryotes16–18. The interactions between these microbes and their macroalgal hosts is often specific. Some bacteria only grow on certain species of seaweeds, determined by enzymes that bacteria possess to break down polysaccharides that form algal cell walls19–22. For example, one bacterium, Zobellia galactonorivans colonizes Porphyra umbilicalis23, a red macroalga, and secretes an enzyme to degrade the excreted polysaccharide porphyran19,20. Similarly, microeukaryotes associate with particular types of macroalgae16 and take advantage of nutrients diffusing from macroalgae24. Algae may have long served as attractors for diverse microbial communities, for geochemical evidence indicates that algae became more abundant during important epochs in eukaryotic evolution25, including the origin of animals26.

Fascinated by the influence that algae can exert on microbial communities and historical descriptions of choanoflagellates attached to algae27–29, we decided to test if we could prepare media from macroalgae to foster the growth of S. rosetta in the laboratory. In these experiments, we were surprised to find that S. rosetta developed into multicellular rosettes in media prepared from P. umbilicalis even in the absence of bacteria that produce rosette-inducing cues. Through a biochemical approach, we found that the inducing factor was porphyran, showing that polysaccharides from algae can serve as environmental cues for choanoflagellate life history transitions.

Results

S. rosetta develops into multicellular rosettes in media prepared from red algae

We initially set out to improve media for culturing S. rosetta by enriching seawater with macroalgae, for we previously observed that small alterations in media formulations increased the maximal cell density of S. rosetta in culture30. We reasoned that macroalgae may provide better nutritional support for the growth of S. rosetta and/or their bacterial prey, which is their obligate food source, because macroalgae accumulate high concentrations of essential nutrients from their environment31–33. Nutrients derived from macroalgae may also be more ecologically relevant for choanoflagellates because they and the bacteria that influence the life histories of choanoflagellates have previously been isolated from macroalgae28,19,5. Therefore, we prepared medias enriched with a red alga (Porphyra umbilicalis), a green algae (Ulva spp.), or a brown alga (Saccharina latissima) by steeping dried fronds of each macroalga in synthetic seawater (Table S1). After acclimating cultures of S. rosetta feeding on Echnicola pacifica to each media over three or more passages, we compared the proliferation of S. rosetta in media prepared from macroalgae to a traditional growth medium prepared from cereal grass34,35 (Fig. S1A). Medias prepared with P. umbilicalis and Ulva spp. both supported choanoflagellate growth as well as cereal grass media; whereas, S. rosetta grew more slowly and to a lower density in media prepared from S. latissima.

To our great surprise, we also observed that S. rosetta sporadically developed into multicellular, rosette colonies. Previous work found that rosettes only develop in the presence of inducing cues produced by bacteria, of which the most intensively studied are sulfonolipids from Algoriphagus machipongonensis, but the only bacterium in our culture was E. pacifica, which does not produce rosette inducing factors2,6,36. Intrigued by the infrequent appearance of rosettes in our cultures, we decided to optimize the preparation of red algae media for more reliable rosette induction (Fig. S1 and Table S1) and better cell proliferation (Fig. S2 and Table S2). In this optimization, media prepared at higher temperatures (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1B) or with a larger mass of P. umbilicalis (Fig. S1C) led to a higher proportion of S. rosetta developing into rosettes, but the same conditions did not result in rosettes developing in media prepared from Ulva spp. The absence of rosettes in media prepared from Ulva spp. or in media steeped with P. umbilicals at low temperatures is most likely due to the lack of inductive cues rather than deficient growth conditions, as the addition of rosette inducing factors from outer membrane vesicles of A. machipongonensis still caused rosette development in those medias.

We further confirmed that S. rosetta developed into rosettes by fluorescently staining colonies with an antibody that recognizes a secreted protein, Rosetteless, necessary for rosette development36,37. This antibody staining showed that rosettes grown in media prepared from P. umbilicalis contain Rosetteless at the basal ends of individual cells that point toward the interior of the rosette, just as in rosettes induced with bacterial cues (Fig. 1C). Altogether, these data show that media prepared from P. umbilicalis induces rosette development similarly to bacterial signals.

A polysaccharide, porphyran, purified from P. umbilicalis induces rosette development

What factor in the media prepared from P. umbilicalis induces S. rosetta to develop into rosettes? We first thought the factor may come from a bacterium, for only bacterial cues have previously been described to induce rosette development38,5,6,4,39. Furthermore, P. umbilicalis can harbor the epiphytic bacteria Z. galactanivorans that induces rosette development5. To test if bacteria may have been the source of the inductive cue in our media preparation, we isolated bacteria from the dried fronds of P. umbilicalis that were used to make media. We found species from the genera Microbacterium, Pseudomonas, Aureimonas, and Aeromicrobium associated with the dried fronds. However, none of the isolated bacteria induced rosettes when added to cultures of S. rosetta feeding on E. pacifica. Although this negative result cannot completely exclude bacteria as the source of the inducing factor, we began to consider that the factor may come from P. umbilicalis. In support of this hypothesis, we also found that media prepared from other species of red algae, Palmaria palmata and Chondrus crispus, induced rosette development (Fig. S1D), indicating that the inducing factor may be a molecule commonly shared among those algae.

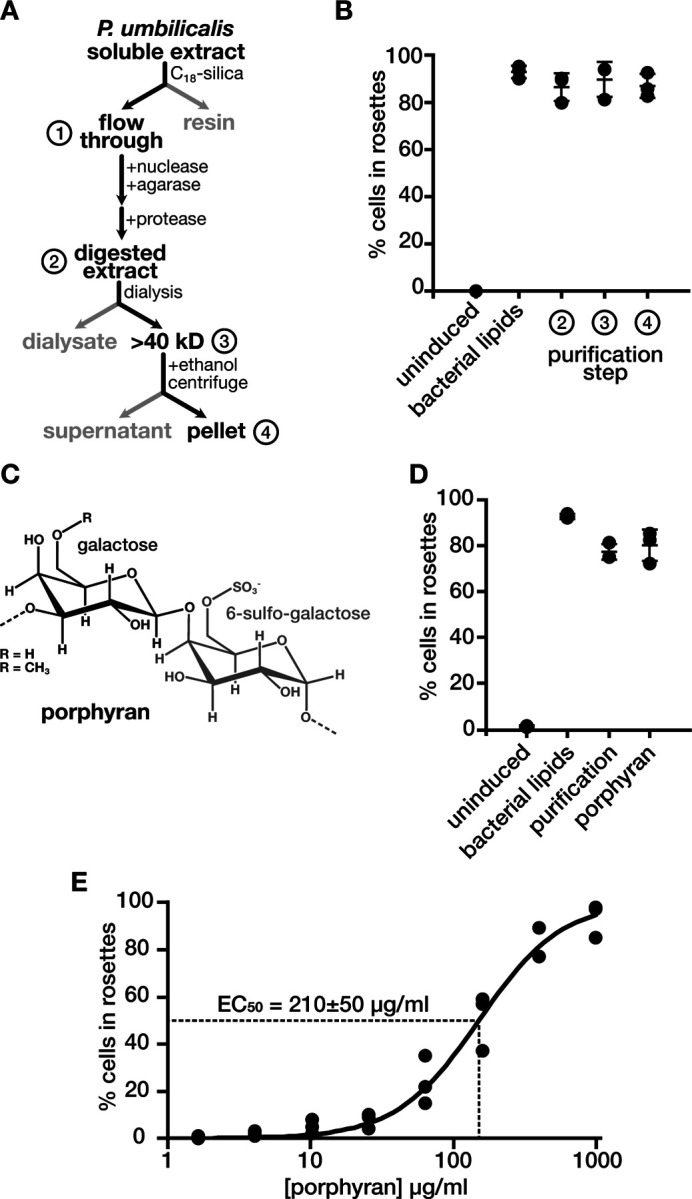

The observation that high temperature preparations of media more frequently induced rosettes encouraged us to biochemically purify a rosette-inducing factor from P. umbilicalis (Fig. 2A). Inspired by previous studies that identified rosette-inducing factors from bacteria5,6, we tested rosette induction for each step of the biochemical purification (Fig. 2B). After obtaining a soluble extract from P. umbilicalis with potent rosette induction, we first used a hydrophobic resin (silica functionalized with octadecyl moieties) to test if the inducing factor from P. umbilicalis was a lipid like the previously described bacterial cues, yet the rosette-inducing activity remained in solution after passing through the hydrophobic resin, indicating that the inducing factor from P. umbilicalis was hydrophilic and probably not a lipid. Next, we added a battery of enzymes to digest any proteins or nucleic acids that may have persisted in the purification and to degrade agar, which was making the extract more viscous. None of the enzymes, however, reduced rosette induction. We next wanted to know if the inducing factor was a large or small molecule, so we next dialyzed the extract with membranes that had a 40 kD molecular weight cutoff. The retention of rosette inducing activity in the dialysis bag indicated that the inducing factor was a macromolecule larger than 40 kD. In later purifications, we also varied the order of purification steps to place the hydrophobic resin at the end, which still produced a simplified extract that induced rosette development.

Figure 2: Porphyran, a sulfated galactan from P. umbilicalis, induces rosette development.

(A and B) The purification of rosette inducing activity from P. umbilicalis extracts. (A) The purification scheme for rosette inducing activity started with the preparation of a soluble extract from P. umbilicalis. A hydrophobic resin (C18-silica) retained hydrophobic molecules while hydrophilic molecules passed through the resin in the ‘flow through,’ to which we added enzymes that degrade nucleic acids, agar, and proteins to produce the ‘digested extract.’ In this sample, we measured rosette inducing activity (as described in Fig. 1B) to confirm that the ‘digest extract’ retained rosette inducing activity (B). Likewise, rosette inducing activity remained after dialyzing the ‘digested extract’ in a membrane with a 40 kD molecular weight cutoff. To this dialyzed sample, the addition of ethanol formed precipitates that were pelleted by centrifugation. The dissolved pellet retained rosette inducing activity.

(C) The chemical structure of porphyran. Porphyran consists of linked galactose molecules with either a sulfonate or methyl functional group on the sixth carbon of alternating monosaccharides.

(D) Porphyran induces multicellular rosette development. Porphyran purchased from a commercial source induces rosettes to the same extent as the purified rosette inducing activity from P. umbilicalis (labeled purification) and bacterial lipids from A. machipongonensis. Rosette induction was quantified as described in Figure 1B.

(E) Rosette induction is directly proportional to the concentration of porphyran. Across a serial dilution, the effective concentration of porphyran that induces 50% of cells to form rosettes (EC50) is 210±50 µg/ml, an average calculated from fitting the hill equation (line) to independent triplicates of the dilution series (dots).

We reasoned that polysaccharides were the most likely type of macromolecule to still induce rosette development after the addition of enzymes and the depletion of hydrophilic molecule(s). After precipitating polysaccharides from the purified extract by adding ethanol, we found that molecules dissolved from the pellet induced rosettes (Fig. 2B). A carbohydrate analysis of this pellet showed that it was composed of galactose and sulfur (Fig. S3). This composition mirrors that of porphyran, a major extracellular polysaccharide from P. umbilicalis that is made of alternating subunits of galactose and 6-sulfo-galactose (Fig. 2C). To independently confirm that porphyran was the inducing molecule, we obtained porphyran from a commercial source and tested its ability to induce rosettes. This commercial source of porphyran induced rosettes to the same extent as our own preparation (Fig. 2D). We also characterized the potency of porphyran to induce rosette development in a dilution series, finding that the effective concentration for fifty-percent induction (EC50) was 210±50 µg/ml. Assuming a minimum molecular weight of 40 kD for porphyran, this potency would correspond to a micromolar concentration of porphyran, which approaches the potency of rosette inducing lipids from A. machipongonensis6.

Because bacteria are an obligate food source for S. rosetta, we cannot yet discern if porphyran directly induces rosette development or acts through a bacterial intermediate. More mechanistic work is necessary to distinguish among these possibilities, yet we suspect that S. rosetta directly recognizes porphyran. In support of this hypothesis, we purified outer membrane vesicles from E. pacifica that had been grown in rosette inducing media, and those vesicles failed to induce rosettes when added to cultures of S. rosetta grown in non-inducing media (Fig. S4B). Moreover, the E pacifica genome40 lacks the family of glycosyl hydrolases for ingesting porphyran, and the addition of the constituent monosaccharides of porphyran to cultures of S. rosetta and E. pacifica failed to induce rosettes (Fig. S4A). Regardless of the exact induction mechanism, porphyran now provides a biochemical probe to further investigate how S. rosetta perceives this cue to induce rosette development.

Discussion:

The realization that red algae can influence the multicellular development of S. rosetta began with a search for improved media to grow choanoflagellates. Bacterivorous protists, like choanoflagellates, proliferate in enriched media that promote the growth of prey bacteria and deliver nutrients that neither protists nor their bacterial prey can produce34. For example, media prepared with lemon peel provides the limiting nutrient ubiquinone for the growth of the dinoflagellate Oxyrrhis marina41. We could only find one previous example of using macroalgae as a component in a growth medium34, so our work adds macroalgae to the repertoire of enrichments for protist growth media. To demonstrate the generality of macroalgae as media enrichments, we grew a variety of choanoflagellate species in media prepared from red or green algae (Table S3).

We identified porphyran as the molecule from red algal media that induces multicellular development in S. rosetta. This discovery provides a biochemical insight into the associations between choanoflagellates and algae. These interactions were evident in the earliest descriptions of choanoflagellates, in which algae were sometimes used as bait to collect choanoflagellates that can directly attach to macroalgae27,28. In those direct connections, we can now appreciate that algae may not only have been convenient landing pads for choanoflagellates but also a source of signaling cues that direct life history transitions. Proximity is likely a key factor for a freely swimming choanoflagellate to detect cues from algae and their epiphytic bacterial communities, for large macromolecules like proteins, vesicles, and porphyran only slowly diffuse from their initial source. Alternatively, large molecules could accumulate in enclosed environments such as ephemeral pools near coastlines. In fact, on a field trip near Waquoit Bay, Massachusetts, we found an example of a puddle on a jetty in which a piece of red algae laid (Fig. S5B). The water in this puddle was teaming (~104 cells/ml) with a choanoflagellate species that formed chain colonies (Fig. S5C). Similarly, splash pools in Curaçao support the growth of another colony-forming choanoflagellate, Choanoeca flexa42,43.

Algae may emit a variety of cues into their environment to mold their surrounding microbial community. For example, Asterionellopsis glacialis, a diatom, by altering the secretion of metabolites44. Small metabolites can also attract phagotrophic protists to graze on phytoplankton45. During phytoplankton blooms, diatoms secrete copious quantities of the polysaccharides laminarin46 and fucoidan47, which may provide food and/or environmental cues for bacteria and microeukaryotes. The liberation of porphyran and other polysaccharides from macroalgae, however, may often depend on epiphytic bacteria that can break down polysaccharides that form algal cell walls20, and seasonal48 and life history49 variations in polysaccharide modifications may make the degradation of cell walls more or less efficient. Tidal forces and desiccation between tides may further contribute to the release of those polysaccharides. All of these possible variations emphasize how a multiplicity of environmental factors can converge to alter the interactions within the habitats formed by algae. The work presented here emphasizes that S. rosetta is a suitable model system to investigate how the confluence of bacterial, algal, and physical factors influence the responses of microeukaryotes to complex environmental cues.

Materials and Methods:

Preparation of seawater media enriched with algae (Table S1)

(Note: All recipes for preparing media are in Table S1)

Media for culturing choanoflagellates is prepared from a concentrated stock of artificial seawater enriched with algae. To prepare this concentrated stock, 10 g of dried algae fragments (Maine Coast Sea Vegetables) is homogenized in 1 l of artificial seawater (ASTM D 1141, Ricca Cat No. 8363–5) by stirring at 400–500 rpm on a plate stirrer for 3 h and at the following temperatures: 80°C to prepare rosette inducing media from P. umbilicalis or 40°C for general cell culture media with minimal rosette induction activity. Afterwards, we removed large debris by first filtering algae/seawater mixture through two layers of Miracloth (EMD Millipore, Cat No. 475855-1R) and then once through a standard coffee filter and then twice through a Buchner funnel lined Whatman Grade 1 Filter Paper (Cytivia, Cat No. 1001–090). Note that the coffee filter is optional but highly recommended to increase the speed of filtration through the buchner funnel. Finally, the crudely filtered extract is vacuum filtered through a sterile 0.22 µm polyethersulfone (PES) membrane connected to a sterile flask (Fisherbrand ,Cat No. FB12566504). This final filtrate is called 100% Algae Stock.

We dilute the concentrated stock of algae into artificial seawater along with mineral, trace metal, and vitamin supplements to prepare a final media for cell culture. To do so we dilute stocks of 100% Algae Stock, 1000x (Potassium Iodide, Sodium Nitrate, Sodium Phosphate), 1,000x L1 vitamins54, and 1,000x L1 trace metals54 in artificial seawater to yield a final 1x concentration of each component. A 1,000x Sodium Silicate stock can also be added for organisms, like loricate choanoflagellates and diatoms, that require silicate for growth. After all of the components are combined, the media is vacuum filtered through a 0.22 µm PES filter connected to a sterile flask. The resulting media is called 25% Algae Media.

Maintaining Cultures of Salpingoeca rosetta

Strains of S. rosetta were co-cultured with Echinicola pacifica bacteria (SrEpac; American Type Culture Collection [ATCC], Manassas, VA, Cat. No. PRA-390)2 in media enriched with dried cereal grass or seaweeds as described above and Table S1. To maintain cultures of rapidly proliferating cells at 27°C, we passaged S. rosetta from cultures that reached ~105 cells/ml into fresh media at dilutions of ~1/50 (daily) or ~1/100 (every two days). The timing and dilution factor were adjusted according to growth parameter measurements for each media condition (Table S2). Cultures were maintained in vented, treated culture flasks and in media volumes that corresponded to 0.24 ml per cm2 of culture flask surface area. To characterize the phenotypic effect of bacteria isolated from P. umbilicalis on S. rosetta, added the isolated bacteria to SrEpac and passed these cultures three times before assessing the level of rosette induction (as described below).

Preparation of rosette inducing factors (Figures 1, 2, S1, and S4)

Outer membrane vesicles from A. machipongonensis (ATCC BAA-2233) or E.pacifica were prepared from the supernatant of bacterial cultures as previously described with a few modifications. First, bacteria were grown in different sources media prepared from P. umbilicalis or Ulva spp. Second, after harvesting outer membrane vesicles from the filtered supernatant by centrifugation for 3 h at 150,000 x g and 4°C, the membrane pellet was transferred to a tared microcentrifuge tube for determining the crude mass of the outer membrane vesicles. A buffer of 50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4 was added to the outer membrane vesicles to achieve a final concentration of 10 mg/ml. After resting overnight at 4°C, the solution of outer membrane vesicles was filtered through a sterile 0.45 µm polyethersulfone syringe filter and stored at 4°C for later use. Solutions of porphyran either purified from P. umbilicalis (see below) or purchased from Biosynth (Cat. No.YP157502) were resuspended in 50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4 to a final concentration of 20 mg/ml and then sterile filtered in a 0.45 µm polyethersulfone syringe filter. In the same manner, we prepared solution of D-galactose-6-O-sulphate (Biosynth, Cat. No. MG00761) and D-galactose (Fisher Bioreagents, Cat. No. G1-100).

Rosette-Induction Assays (Figures 1, 2, S1, and S4)

Inducing cues were added to samples of SrEpac that were seeded at a density of 104 cells/ml for S. rosetta in each well of a 12-well culture plate with 1 ml of culture per well. After 22–36 h from induction, cells were immobilized by adding 10 M LiCl to 500 µl sample of SrEpac for a final concentration of 500mM, and chains of slow swimmers or cellular aggregates were disrupted by vortexing. To quantify percent rosette induction, we counted a total of 500 cells (Bright-Line hemacytometer, Hausser Scientific) and scored them as single cells or cells within rosettes. Rosettes were defined as groups of four or more cells that resisted agitation (vortexing) and were centrally organized around their basal ends6. Each induction experiment was performed as independent triplicates.

Quantifying the growth dynamics of S. rosetta (Figures S1 and S2 and Table S2)

SrEpac was inoculated into fresh media at a density of 104 cells/ml for S. rosetta. The freshly inoculated cultures were distributed in 0.5 ml aliquots into each well of a 24-well plate. At each time point over a time course, one of the wells was homogenized and then fixed with the addition of 20 µl of 37.5% formaldehyde. This sample was then loaded into the hemocytometer (Bright-Line hemacytometer, Hausser Scientific) to determine the cell density. An independent triplicate was taken for each time point. We calculated the doubling time (D), maximal density (M), and lag time (T) for each time course by fitting the data with a least absolute deviation algorithm to a modified version of a logistic growth equation that explicitly models the lag time with a heaviside step function:

where P(t) is the cell density at a given time (t) and P0 is the initial cell density.

Immunofluorescent staining (Figure 1)

We adapted this method from one developed by Fredrick Leon55. A day before imaging SrEpac was seeded 104 cells/mL of S. rosetta in media prepared from either P. umbilicalis or Ulva spp., which were supplemented with outer membrane vesicles from A. machipongonensis. The cells were grown at 27°C for one day. On the day of imaging, chambered glass coverslips (ibidi, Cat.No: 81507) were coated with 10mg/mL Poly D-lysine hydrobromide (MP Biomedicals, Cat. No. 102694) and then washed 3 times with 50uL of filtered artificial seawater (ASW). With a wide-bore pipette tip, 70 µl of rosettes were pipetted into a well of the coated coverslip and allowed to settle for 15 minutes. Afterwards, 50 µl of the liquid was removed, leaving 25 µl behind to avoid damaging delicate cell structures by drying the coverslip. The cells were first fixed by gently adding 50 µl of cytoskeleton buffer56,57 (10 mM MES, pH 6.1; 138 KCl, 3 mM MgCl2; 2 mM ethylene-glycol-bis(β-aminoethylether)-N,N,N’,N’-tetraacetic acid [EGTA]-KOH; 15% (w/v) sucrose) that also contained 3% paraformaldehyde (PFA). After incubating for 5 min at room temperature, 50 µl was removed. Cells were additionally fixed by adding 50 µl of the same fixation buffer that was now supplemented with a low concentration to Tween-20 (Cytoskeleton Buffer with 3% PFA and 0.07% Tween-20), which we found to improve the the preservation of cellular structures throughout subsequent step. Cells were incubated for 5 min at room temperature before removing 50 µl of the liquid. The fixation was quenched with the addition of 50 µl of quench buffer (Cytoskeleton Buffer with 0.3M glycine, pH 6.1). Immediately after, 50 µl was removed, and 50 µl of permeabilization buffer (LICOR Intercept PBS Blocking Buffer [LI-COR Biosciences Cat. No. 927–70001]; 8% (v/v) methanol, and 1% (v/v) Tween-20) was added to the coverslip and incubated for 30 minutes. Afterwards, wells were washed by replacing 50 µl of the liquid with antibody buffer (LICOR Intercept PBS Blocking Buffer with 1% (v/v) Tween-20), and we repeated this step for a total of two washes. Afterwards, 50 µl of an antibody mixture diluted in antibody buffer was added to the well. The antibodies were diluted as follow: 1:200 of 200 U/ml phalloidin-Alexa488, 1:500 mouse anti-αTubulin Monoclonal Antibody (DM1A) (Invitrogen, Cat. No. 62204), 1:1000 alpaca anti-mouse IgG1-Alexa555, 1:500 rabbit anti-Rosetteless (generously provided by Nicole King and Flora Rutaganira), and 1:1000 alpaca ant-rabbit IgG-Alexa647. The antibodies were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature and in the dark. Afterwards, the well was washed twice with 1x PEM (100 mM PIPES, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgSO4, pH 6.9 with KOH) before imaging.

Widefield Microscopy (Figure 1)

We visualized immunofluorescent samples on a Nikon Eclipse Ti2-E inverted microscope outfitted with a D-LEDI light source, Chroma 89401 Quad Filter Cube, and 60x CFI Plan Apo VC NA1.2 water immersion objective. Z-stacks of samples were imaged with two-fold binning (120 µm/pixel) on a Nikon Digital Sight 50 M Camera with 100–500 msec exposure times for each channel and variable illumination intensities to extend the dynamic range of signal without photobleaching samples. Images were processed in FIJI by projecting the maximal intensity of a central section of the rosette, subtracting the background (8 pixel, sliding paraboloid radius), and enhancing the contrast (saturating 0.2–0.4% of the pixels).

Purification of rosette inducing activity from P. umbilicalis (Figure 2)

Dried algae was finely ground by flash freezing in liquid nitrogen and then grinding in a mortar and pestle chilled with liquid nitrogen. Into 200 ml of 50mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 g of finely ground dried algae was stirred for 1 h at 400–500 rpm and 80°C. The homogenate was clarified by filtration through two layers of miracloth and then by centrifugation at 16,000 x g at 4°C for 40 minutes in a fixed angle centrifuge. Nucleic acids and agar were degraded in the clarified extracted by adding benzonase (35 units/ml, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. 88700) and agarase (0.2 units/ml, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. EO0461) and then incubating at 42°C for 1 hour. To degrade proteins, we treated the filtrate with pronase (10mg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 hour at 37°C). Afterward, enzymes were heat-inactivated at 90°C for 20 minutes. The digested extract was dialyzed through a 20kD or 40 kD membrane (Slide-A-Lyzer, Cat. No. 66003) against ultrapure water for 24 h at 4°C . To deplete lipophilic contents, we flowed the dialyzed extract through a hydrophobic resin (Sep-pak Plus Short tC18, Waters Corp, Cat. No. 50-818-646). To prepare the resin, we first passed a 2:1 ratio of methanol and chloroform, then equilibrated it in 50 mM Tris pH 8.0). To precipitate rosette inducing activity from the flow-through, 4 volumes of ethanol were added incubated overnight at −20°C. Afterward the pellet was recovered by centrifuging at 16,000 x g for 40 min at 4°C. The pellet was dried for 30 minutes at room temperature and then resuspended in 50mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 to 10 mg/ml. Samples were flash-frozen with nitrogen and stored at −80°C for later use.

Carbohydrate Content Analysis (Figure nd S3):

Carbohydrate content of the purified pellet from P. umbilicalis extracts was performed by the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center Analytical Services at the University of Georgia. The carbohydrate analysis was performed by derivatizing samples with O-trimethylsilyl (TMS) for characterization by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC-MS)58,59. Lyophilized samples were hydrolyzed using 1 M methanolic HCl for 16 h at 80 °C and then cooled to room temperature before drying with N2 gas. 8 drops of methanol, 4 drops of pyridine, 4 drops of and acetic anhydride were added for N-acetylation, and the samples were heated at 100 °C for approximately 30 min. Once cooled, the samples were dried again, then 15 drops of Tri-Sil was added and incubated at 80 °C for 30 min. The samples were dried down one last time, before adding 150 μL of hexane to each. Each was briefly vortexed and centrifuged, then the contents of each sample transferred to GC-MS vials. 1 μL of each was injected into the GC-MS for analysis.

Sulfate analysis was performed by first creating a standard curve with a 1-mg/mL sodium sulfate (Na2SO4)/hydrochloric acid (HCl) solution (Fig. S3B). In addition, a 0.83-mg/mL solution of the sample was made with 200 μg (40 μL) of Porphyra umbilicalis from a 5-mg/mL sample solution, and 200 μL of 1.5 M HCl. The sample and standards were made in glass screw-cap tubes and incubated overnight at 80 °C. A gelatin solution was made by dissolving 0.5 g gelatin and 100 mL of water at 60 °C. Once dissolved, the solution was cooled to room temperature, and 2.5 mL of 6 M HCl and 0.5 g of barium chloride (BaCl2) were added and stirred/mixed with the gelatin solution overnight. The next day, the samples were removed from the heating block and cooled to room temperature. Once cool, 467 μL of the barium chloride-gelatin solution was added to 200 μL of each sample/standard. The solutions were vortexed to mix, and then 200 μL of each was added to a 96-well plate. The samples were allowed to incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes. The absorbance was read at 360 nm, blanking with the first point of the standard curve.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank the following individuals for insights and support that helped advance this work: Susan Brawley (U Maine), Hilary Morrison (Marine Biological Laboratory), Nicole King (HHMI/UC Berkeley) and Flora Rutaganira (Stanford U) for generously sharing antibodies and choanoflagellate strains. We are grateful to Fredrick Leon, Vicki Deng, and Ben Larson for providing critical advice and feedback as well as supporting early stages of the project. We thank the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center at the University of Georgia for performing glycosyl composition analysis, which was supported by NIH Grant R24GM137782. This work was supported by awards to DSB from the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub, the UCSF Sandler Program for Breakthrough Biomedical Research, a David and Lucile Packard Foundation Fellowship in Science and Engineering, and a Marine Biological Laboratory Whitman Center Fellowship sponsored by Nikon Inc. GV was a fellow in the UCSF IMSD Fellow and supported by a training grant for the UCSF Tetrad Graduate Program Training Grant T32GM139786.

References:

- 1.Dayel M.J., Alegado R.A., Fairclough S.R., Levin T.C., Nichols S.A., McDonald K., and King N. (2011). Cell differentiation and morphogenesis in the colony-forming choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta. Dev. Biol. 357, 73–82. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levin T.C., and King N. (2013). Evidence for Sex and Recombination in the Choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta. Curr. Biol. 23, 2176–2180. 10.1016/j.cub.2013.08.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woznica A., Gerdt J.P., Hulett R.E., Clardy J., and King N. (2017). Mating in the Closest Living Relatives of Animals Is Induced by a Bacterial Chondroitinase. Cell 170, 1175–1183.e11. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ireland E.V., Woznica A., and King N. (2020). Synergistic Cues from Diverse Bacteria Enhance Multicellular Development in a Choanoflagellate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 86, e02920–19. 10.1128/AEM.02920-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alegado R.A., Brown L.W., Cao S., Dermenjian R.K., Zuzow R., Fairclough S.R., Clardy J., and King N. (2012). A bacterial sulfonolipid triggers multicellular development in the closest living relatives of animals. eLife 1, e00013. 10.7554/eLife.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woznica A., Cantley A.M., Beemelmanns C., Freinkman E., Clardy J., and King N. (2016). Bacterial lipids activate, synergize, and inhibit a developmental switch in choanoflagellates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113, 7894–7899. 10.1073/pnas.1605015113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McFall-Ngai M., Hadfield M.G., Bosch T.C.G., Carey H.V., Domazet-Lošo T., Douglas A.E., Dubilier N., Eberl G., Fukami T., Gilbert S.F., et al. (2013). Animals in a bacterial world, a new imperative for the life sciences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 3229–3236. 10.1073/pnas.1218525110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alegado R.A., and King N. (2014). Bacterial Influences on Animal Origins. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 6, a016162. 10.1101/cshperspect.a016162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woznica A., and King N. (2018). Lessons from simple marine models on the bacterial regulation of eukaryotic development. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 43, 108–116. 10.1016/j.mib.2017.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woznica A. (2024). What choanoflagellates can teach us about symbiosis. PLOS Biol. 22, e3002561. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3002561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pringsheim E.G. (1956). Micro-Organisms from Decaying Seaweed. Nature 178, 480–481. 10.1038/178480a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wahl M., Goecke F., Labes A., Dobretsov S., and Weinberger F. (2012). The Second Skin: Ecological Role of Epibiotic Biofilms on Marine Organisms. Front. Microbiol. 3. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egan S., Harder T., Burke C., Steinberg P., Kjelleberg S., and Thomas T. (2013). The seaweed holobiont: understanding seaweed–bacteria interactions. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37, 462–476. 10.1111/1574-6976.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dang H., and Lovell C.R. (2015). Microbial Surface Colonization and Biofilm Development in Marine Environments. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 80, 91–138. 10.1128/mmbr.00037-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Florez J.Z., Camus C., Hengst M.B., and Buschmann A.H. (2017). A Functional Perspective Analysis of Macroalgae and Epiphytic Bacterial Community Interaction. Front. Microbiol. 8. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemay M.A., Martone P.T., Hind K.R., Lindstrom S.C., and Wegener Parfrey L. (2018). Alternate life history phases of a common seaweed have distinct microbial surface communities. Mol. Ecol. 27, 3555–3568. 10.1111/mec.14815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lemay M.A., Chen M.Y., Mazel F., Hind K.R., Starko S., Keeling P.J., Martone P.T., and Parfrey L.W. (2021). Morphological complexity affects the diversity of marine microbiomes. ISME J. 15, 1372–1386. 10.1038/s41396-020-00856-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramírez-Puebla S.T., Weigel B.L., Jack L., Schlundt C., Pfister C.A., and Mark Welch J.L. (2022). Spatial organization of the kelp microbiome at micron scales. Microbiome 10, 52. 10.1186/s40168-022-01235-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hehemann J.-H., Correc G., Barbeyron T., Helbert W., Czjzek M., and Michel G. (2010). Transfer of carbohydrate-active enzymes from marine bacteria to Japanese gut microbiota. Nature 464, 908–912. 10.1038/nature08937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbeyron T., Thomas F., Barbe V., Teeling H., Schenowitz C., Dossat C., Goesmann A., Leblanc C., Oliver Glöckner F., Czjzek M., et al. (2016). Habitat and taxon as driving forces of carbohydrate catabolism in marine heterotrophic bacteria: example of the model algae-associated bacterium Zobellia galactanivorans DsijT. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 4610–4627. 10.1111/1462-2920.13584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin J.D., Lemay M.A., and Parfrey L.W. (2018). Diverse Bacteria Utilize Alginate Within the Microbiome of the Giant Kelp Macrocystis pyrifera. Front. Microbiol. 9. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin M., Barbeyron T., Martin R., Portetelle D., Michel G., and Vandenbol M. (2015). The Cultivable Surface Microbiota of the Brown Alga Ascophyllum nodosum is Enriched in Macroalgal-Polysaccharide-Degrading Bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 6. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miranda L.N., Hutchison K., Grossman A.R., and Brawley S.H. (2013). Diversity and Abundance of the Bacterial Community of the Red Macroalga Porphyra umbilicalis: Did Bacterial Farmers Produce Macroalgae? PLOS ONE 8, e58269. 10.1371/journal.pone.0058269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armstrong E., Rogerson A., and Leftley J.W. (2000). The Abundance of Heterotrophic Protists Associated with Intertidal Seaweeds. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 50, 415–424. 10.1006/ecss.1999.0577. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brocks J.J., Nettersheim B.J., Adam P., Schaeffer P., Jarrett A.J.M., Güneli N., Liyanage T., van Maldegem L.M., Hallmann C., and Hope J.M. (2023). Lost world of complex life and the late rise of the eukaryotic crown. Nature 618, 767–773. 10.1038/s41586-023-06170-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brocks J.J., Jarrett A.J.M., Sirantoine E., Hallmann C., Hoshino Y., and Liyanage T. (2017). The rise of algae in Cryogenian oceans and the emergence of animals. Nature 548, 578–581. 10.1038/nature23457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manual of the infusoria, including a description of all known flagellate, ciliate, and tentaculiferous protozoa, British and foreign and an account of the organization and affinities of the sponges by Saville Kent W., 3 vol (1881). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leadbeater B.S.C., and Thomsen H.A. (2000). Choanoflagellida. In The Illustrated Guide to the Protozoa (Allen Press Inc.), pp. 14–38. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leadbeater B.S.C. (2015). The choanoflagellates: evolution, biology, and ecology (Cambridge University Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Booth D.S., and King N. (2020). Genome editing enables reverse genetics of multicellular development in the choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta. eLife 9, e56193. 10.7554/eLife.56193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Croft M.T., Lawrence A.D., Raux-Deery E., Warren M.J., and Smith A.G. (2005). Algae acquire vitamin B12 through a symbiotic relationship with bacteria. Nature 438, 90–93. 10.1038/nature04056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wells M.L., Potin P., Craigie J.S., Raven J.A., Merchant S.S., Helliwell K.E., Smith A.G., Camire M.E., and Brawley S.H. (2017). Algae as nutritional and functional food sources: revisiting our understanding. J. Appl. Phycol. 29, 949–982. 10.1007/s10811-016-0974-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brawley S.H., Blouin N.A., Ficko-Blean E., Wheeler G.L., Lohr M., Goodson H.V., Jenkins J.W., Blaby-Haas C.E., Helliwell K.E., Chan C.X., et al. (2017). Insights into the red algae and eukaryotic evolution from the genome of Porphyra umbilicalis (Bangiophyceae, Rhodophyta). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, E6361–E6370. 10.1073/pnas.1703088114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee J.J., and Soldo A.T. (Anthony T.) (1992). Protocols in protozoology (Society of Protozoologists; ). [Google Scholar]

- 35.King N., Young S.L., Abedin M., Carr M., and Leadbeater B.S.C. (2009). Starting and Maintaining Monosiga brevicollis Cultures. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2009, pdb.prot5148. 10.1101/pdb.prot5148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levin T.C., Greaney A.J., Wetzel L., and King N. (2014). The Rosetteless gene controls development in the choanoflagellate S. rosetta. eLife 3. 10.7554/eLife.04070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Booth D.S., and King N. (2020). Genome editing enables reverse genetics of multicellular development in the choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta. eLife 9, e56193. 10.7554/eLife.56193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fairclough S.R., Dayel M.J., and King N. (2010). Multicellular development in a choanoflagellate. Curr. Biol. 20, R875–R876. 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peng C.-C., Dormanns N., Regestein L., and Beemelmanns C. (2023). Isolation of sulfonosphingolipids from the rosette-inducing bacterium Zobellia uliginosa and evaluation of their rosette-inducing activity. RSC Adv. 13, 27520–27524. 10.1039/D3RA04314B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mukherjee S., Seshadri R., Varghese N.J., Eloe-Fadrosh E.A., Meier-Kolthoff J.P., Göker M., Coates R.C., Hadjithomas M., Pavlopoulos G.A., Paez-Espino D., et al. (2017). 1,003 reference genomes of bacterial and archaeal isolates expand coverage of the tree of life. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 676–683. 10.1038/nbt.3886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Droop M.R., and Doyle J. (1966). Ubiquinone as a Protozoan Growth Factor. Nature 212, 1474–1475. 10.1038/2121474a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brunet T., Larson B.T., Linden T.A., Vermeij M.J.A., McDonald K., and King N. (2019). Light-regulated collective contractility in a multicellular choanoflagellate. Science 366, 326–334. 10.1126/science.aay2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ros-Rocher N., Reyes-Rivera J., Foroughijabbari Y., Combredet C., Larson B.T., Coyle M.C., Houtepen E.A.T., Vermeij M.J.A., King N., and Brunet T. (2024). Mixed clonal-aggregative multicellularity entrained by extreme salinity fluctuations in a close relative of animals. Preprint at bioRxiv, 10.1101/2024.03.25.586565 10.1101/2024.03.25.586565. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shibl A.A., Isaac A., Ochsenkühn M.A., Cárdenas A., Fei C., Behringer G., Arnoux M., Drou N., Santos M.P., Gunsalus K.C., et al. (2020). Diatom modulation of select bacteria through use of two unique secondary metabolites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 27445–27455. 10.1073/pnas.2012088117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shemi A., Alcolombri U., Schatz D., Farstey V., Vincent F., Rotkopf R., Ben-Dor S., Frada M.J., Tawfik D.S., and Vardi A. (2021). Dimethyl sulfide mediates microbial predator–prey interactions between zooplankton and algae in the ocean. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 1357–1366. 10.1038/s41564-021-00971-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Becker S., Tebben J., Coffinet S., Wiltshire K., Iversen M.H., Harder T., Hinrichs K.-U., and Hehemann J.-H. (2020). Laminarin is a major molecule in the marine carbon cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 6599–6607. 10.1073/pnas.1917001117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vidal-Melgosa S., Sichert A., Francis T.B., Bartosik D., Niggemann J., Wichels A., Willats W.G.T., Fuchs B.M., Teeling H., Becher D., et al. (2021). Diatom fucan polysaccharide precipitates carbon during algal blooms. Nat. Commun. 12, 1150. 10.1038/s41467-021-21009-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanz V., Torres M.D., Domínguez H., Pinto I.S., Costa I., and Guedes A.C. (2023). Seasonal and spatial compositional variation of the red algae Mastocarpus stellatus from the Northern coast of Portugal. J. Appl. Phycol. 35, 419–431. 10.1007/s10811-022-02863-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lipinska A.P., Collén J., Krueger-Hadfield S.A., Mora T., and Ficko-Blean E. (2020). To gel or not to gel: differential expression of carrageenan-related genes between the gametophyte and tetasporophyte life cycle stages of the red alga Chondrus crispus. Sci. Rep. 10, 11498. 10.1038/s41598-020-67728-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gf B., Jm G., P R., Ph G., and F M. (1996). Quantifying the short-term temperature effect on light-saturated photosynthesis of intertidal microphytobenthos. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 134, 309–313. 10.3354/meps134309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Noll P., Lilge L., Hausmann R., and Henkel M. (2020). Modeling and Exploiting Microbial Temperature Response. Processes 8, 121. 10.3390/pr8010121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dowd W.W., King F.A., and Denny M.W. (2015). Thermal variation, thermal extremes and the physiological performance of individuals. J. Exp. Biol. 218, 1956–1967. 10.1242/jeb.114926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Torres P.B., Nagai A., Jara C.E.P., Santos J.P., Chow F., and Santos D.Y.A.C. dos (2021). Determination of sulfate in algal polysaccharide samples: a step-by-step protocol using microplate reader. Ocean Coast. Res. 69, e21021. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hallegraeff G.M., Anderson D.M., Cembella A.D., and Enevoldsen H.O. (2004). Manual on harmful marine microalgae (UNESCO; ). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leon F., Esparza J., Deng V., Coyle M.C., and Espinoza S. (2024). Cell-type-specific gene expression enables the choanoflagellate S. rosetta to utilize of colloidal iron. unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Symons M.H., and Mitchison T.J. (1991). Control of actin polymerization in live and permeabilized fibroblasts. J. Cell Biol. 114, 503–513. 10.1083/jcb.114.3.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cramer L.P., and Mitchison T.J. (1995). Myosin is involved in postmitotic cell spreading. J. Cell Biol. 131, 179–189. 10.1083/jcb.131.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Merkle R.K., and Poppe I. (1994). [1] Carbohydrate composition analysis of glycoconjugates by gas-liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. In Methods in Enzymology Guide to Techniques in Glycobiology. (Academic Press; ), pp. 1–15. 10.1016/0076-6879(94)30003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heiss C., Wang Z., Thurlow C.M., Hossain M.J., Sun D., Liles M.R., Saper M.A., and Azadi P. (2019). Structure of the capsule and lipopolysaccharide O-antigen from the channel catfish pathogen, Aeromonas hydrophila. Carbohydr. Res. 486, 107858. 10.1016/j.carres.2019.107858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.