Abstract

Snakebite envenoming remains a devastating and neglected tropical disease, claiming over 100,000 lives annually and causing severe complications and long-lasting disabilities for many more1,2. Three-finger toxins (3FTx) are highly toxic components of elapid snake venoms that can cause diverse pathologies, including severe tissue damage3 and inhibition of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) resulting in life-threatening neurotoxicity4. Currently, the only available treatments for snakebite consist of polyclonal antibodies derived from the plasma of immunized animals, which have high cost and limited efficacy against 3FTxs5,6,7. Here, we use deep learning methods to de novo design proteins to bind short- and long-chain α-neurotoxins and cytotoxins from the 3FTx family. With limited experimental screening, we obtain protein designs with remarkable thermal stability, high binding affinity, and near-atomic level agreement with the computational models. The designed proteins effectively neutralize all three 3FTx sub-families in vitro and protect mice from a lethal neurotoxin challenge. Such potent, stable, and readily manufacturable toxin-neutralizing proteins could provide the basis for safer, cost-effective, and widely accessible next-generation antivenom therapeutics. Beyond snakebite, our computational design methodology should help democratize therapeutic discovery, particularly in resource-limited settings, by substantially reducing costs and resource requirements for development of therapies to neglected tropical diseases.

Snakebite envenoming represents a public health threat in many developing regions, notably impacting on low resource settings in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, Papua New Guinea, and Latin America2. With over two million annual cases, snakebite results in 100,000 fatalities and 300,000 permanent disabilities1. In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) listed snakebite envenoming as a highest priority neglected tropical disease8. Nonetheless, limited resources have been dedicated to improving current antivenom treatments2. These therapies rely on plasma-derived polyclonal antibodies from hyperimmunized animals, complemented by medical and surgical care9. While instrumental in saving lives, antivenom accessibility is hindered by high production costs and inadequate cold chain infrastructure in remote areas9. Serious adverse effects, including hypersensitivity (such as anaphylaxis) and pyrogenic reactions represent additional challenges during antivenom administration2,10,11. Furthermore, these treatments are often ineffective in counteracting neurotoxicity and tissue necrosis due to suboptimal concentrations of neutralizing antibodies against three-finger toxins (3FTxs)5,6,7. This inefficacy stems from the limited immunogenicity of 3FTxs in the antivenom production animal, resulting in a failure to elicit a strong antibody response12. Additional issues arise due to delayed administration of antivenom treatment13. Antibody14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 and non-antibody-based therapeutics23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30 have been tested in preclinical studies, but the development of these types of molecules require either immunization of animals or development of large libraries that require extensive selection, screening, and optimization efforts31.

We reasoned that de novo design approaches could have advantages over traditional methods of antivenom development. First, de novo protein design does not rely on animal immunization, and yields proteins that can be manufactured using recombinant DNA technology, thereby creating a source for continuous production of product with limited batch-to-batch variation. Second, computational design enables the creation of binding proteins with high affinity and specificity without needing extensive experimental screening programs that often rely on pure toxins, which can be challenging to isolate from whole venoms or generate via recombinant expression32,33. Third, the small size of designed proteins could offer enhanced tissue penetration34 compared to large antibodies, enabling rapid toxin neutralization and thereby potentially be particularly effective in neutralizing non-systemic toxicities, such as those leading to local tissue damage. Fourth, designed proteins can have high thermal stability35 and can be produced using low-cost microbial fermentation strategies, which could help enable the development and deployment of new antivenom therapeutics at reduced cost36. Hence, we set out to use the deep learning based RFdiffusion method35 to design antivenoms for short- and long-chain α-neurotoxins and cytotoxins from the 3FTx snake venom toxin family.

Design of α-neurotoxin binding proteins

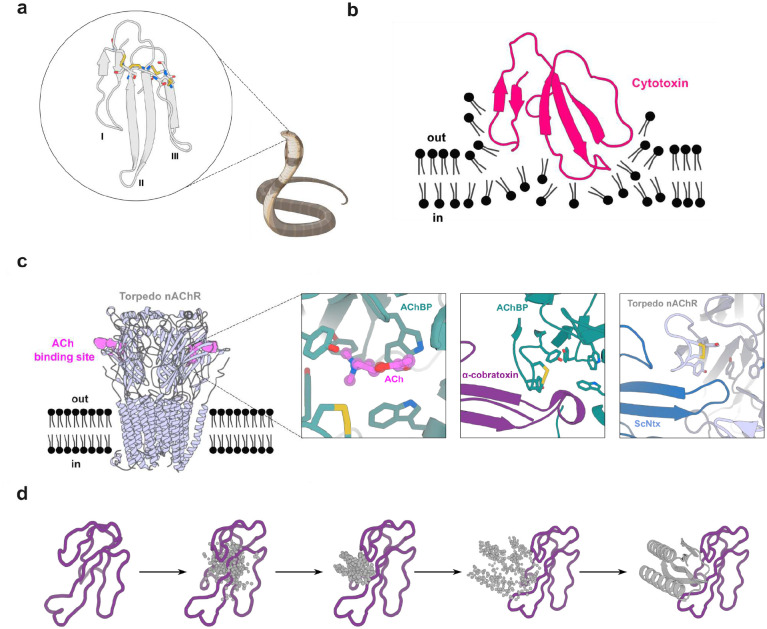

α-neurotoxins, a prominent subclass of 3FTxs, adopt a multi-stranded β-structure with three extended loops protruding from a hydrophobic compact core stabilized by highly-conserved disulfide bridges37,38 (Figure 1a). Short-chain and long-chain α-neurotoxins differ in length and number of disulfide bonds. Despite sequence homology, α-neurotoxins display distinct pharmacological profiles across nAChR subtypes: short- and long-chain α-neurotoxins inhibit muscle-type nAChRs, but only long-chain α-neurotoxins strongly bind to neuronal α7 nAChRs39 (Figure 1c). As many elapid snake species possess venoms that derive their lethal effect from these toxins, it is crucial to neutralize both types of α-neurotoxins to achieve therapeutic efficacy and prevent venom-induced lethality in victims envenomed by these snakes.

Figure 1. Targets of 3 finger snake toxins (3FTxs).

(a) Structure of 3FTxs60 (PDB ID: 1QKD). Highly conserved cysteine residues are highlighted in sticks and each of the three fingers indicated (I-III). (b) Representation of a type IA cytotoxin61 (dark pink) (PDB ID: 5NQ4) interacting with a lipid bilayer. (c) Muscle acetylcholine (Torpedo) receptor (light blue) (PDB ID: 7Z14)39. Acetylcholine (ACh) binding site is depicted in violet. Left inset: Close-up of the acetylcholine binding protein (AChBP) (teal) (PDB ID: 3WIP) bound to Ach62 (violet). A set of aromatic residues form a cage around the neurotransmitter. Middle: Close-up of α-cobratoxin (dark purple) blocking access to the ACh binding site in AChBP (teal) (PDB ID: 1YI5)63. Right: Close-up of ScNtx (dark blue) blocking access to the ACh binding site in the Torpedo receptor (light blue) (PDB ID: 7Z14)39. (d) Schematic showing α-cobratoxin binder design using RFdiffusion. Starting from a random distribution of residues around the specified β-strands in the target toxin (dark purple), successive RFdiffusion denoising steps progressively remove the noise leading at the end of the trajectory to a folded structure interacting with α-cobratoxin β-strands. Panels (a), (b), and (c) were created with BioRender.com

We chose to target our design efforts against the neurotoxin edge β-strands (previously discovered monoclonal antibodies in contrast mimic the nAChR binding site14,21,22), focusing on binding modes blocking neurotoxin binding to nAChRs through steric hindrance. Secondary structure and block adjacency tensors were provided to the RFdiffusion model to specify desired β-strand interactions between the designed binder and target α-neurotoxins (see Methods). For each secondary structure tensor, interactions between one binder β-strand and a target neurotoxin β-strand were encoded in a block adjacency tensor, preconditioning RFdiffusion towards β-strand pairing complexes. Following backbone generation through RFdiffusion denoising trajectories, sequence design was carried out using ProteinMPNN, the resulting designs were filtered based on AF2 initial guess40 and Rosetta metrics, and the most promising candidates selected for experimental characterization.

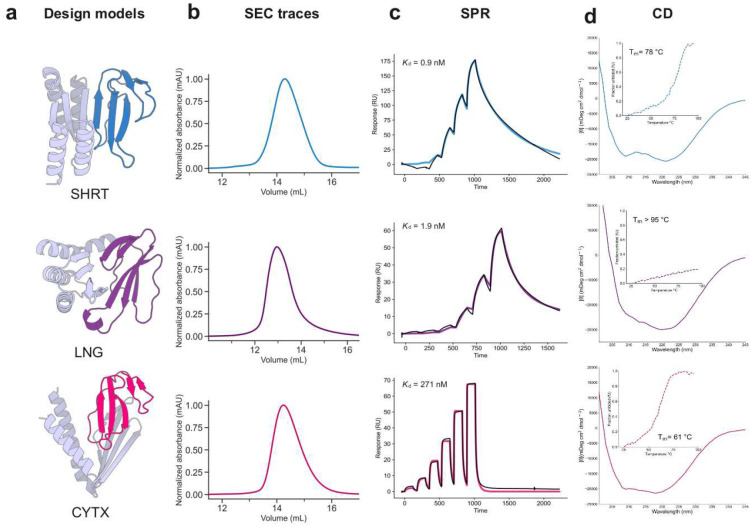

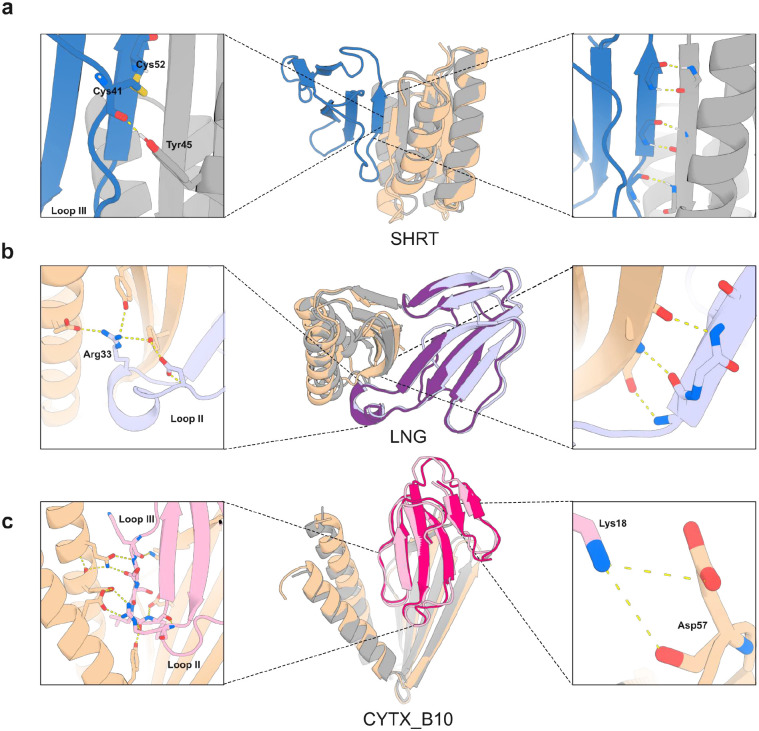

We targeted short-chain α-neurotoxins using a previously designed consensus toxin derived from elapid snakes (ScNtx)41 as a representative template. Synthetic genes encoding 44 designs targeting ScNTx were screened via yeast surface display (YSD), and one candidate was identified to bind to ScNTx with a dissociation constant (Kd) of 842 nM as confirmed by bio-layer interferometry (BLI) (Supplementary Figure S1). Partial diffusion optimization42 improved the binding affinity of the ScNTx binder (SHRT) to 0.9 nM, as determined by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) following the screening of 78 designs (Figure 2c, top row; a very similar value of 0.7 nM was obtained by BLI (Supplementary Figure S2)). The optimized binder displayed a single monomeric peak on size exclusion chromatography (SEC), characteristic αβ-protein circular dichroism (CD) spectra, and thermal stability with a melting temperature (Tm) of 78 °C (Figure 2d, top row). Using X-ray crystallography, we determined the structure of the SHRT design in the apo state, which closely matched the computational design model (2.58 Å resolution; 1.04 Å RMSD) (Figure 3a).

Figure 2. Experimental characterization of 3FTx binding proteins.

(a) Design models of protein binders (gray) bound to their 3FTx targets (dark blue: ScNtx, dark purple: α-cobratoxin, dark pink: consensus cytotoxin). (b) SEC traces of purified proteins. (c) SPR binding affinity measurements. Colored solid lines represent fits using the heterogeneous ligand model, with dissociation constant (Kd) values derived from these fits. (d) CD data confirms the presence of αβ-secondary structure in the 3FTx binding proteins and their thermal stability (inset).

Figure 3. Crystal structures of 3FTx binding proteins closely match design models.

(a) Apo-state crystal structure of SHRT design. Left: Hydrogen bonding between the carbonyl oxygen of Cys41 in ScNtx (dark blue) and the side chain of Tyr45 in the SHRT design model (gray). Middle: Overlay of SHRT design model (gray) with crystal structure (wheat). Right: Backbone hydrogen bonding between the SHRT design model (gray) and ScNtx (dark blue) β strands. (b) Crystal structure of LNG design in complex with α-cobratoxin. Left: Cross-interface hydrogen-bond network involving Arg33 at loop II in α-cobratoxin (light purple) and Glu69, Tyr40, and Tyr49 in LNG crystal structure (wheat). Middle: Overlay of LNG design model (gray) bound to α-cobratoxin (dark purple) with crystal structure of binder (wheat) bound to toxin (light purple). Right: Backbone hydrogen bonding between crystal structure of designed binder (wheat) and α-cobratoxin (light purple) β strands. (c) Crystal structure of CYTX_B10 design in complex with Naja pallida cytotoxin. Left: Cross-interface electrostatic interaction network between loops III and II of Naja pallida cytotoxin (light pink) and binder crystal structure (wheat). Middle: Overlay of CYTX_B10 design model (gray) bound to toxin (dark pink) with crystal structure of binder (wheat) bound to Naja pallida cytotoxin (light pink). Right: Salt bridge between positively charged Lys18 in cytotoxin (light pink) and Asp57 in the binder crystal structure (wheat).

As a representative long-chain α-neurotoxin, we chose α-cobratoxin from Naja kaouthia, one of the most extensively characterized toxins from the 3FTx family43 (Figure 1). From 42 RFdiffusion designs against α-cobratoxin, one candidate had a binding affinity of 1.3 μM using BLI (Supplementary Figure S3). We again used partial diffusion to optimize the binding interface, and of 38 protein designs tested, the highest affinity binder (LNG) had a Kd of 1.9 nM measured by SPR (Figure 2c, middle row; BLI yielded a value of 6.7 nM (Supplementary Figure S4)). CD melting experiments revealed very high thermal stability (Tm > 95°C; Figure 2d, middle row).

Using X-ray crystallography, we determined the structure of the α-cobratoxin binder in complex with the target, which closely matched the computational design model (2.68 Å resolution; 0.42 Å RMSD over design, 0.61 Å over toxin; there is a slight deviation in the positioning of the toxin relative to the binder). As in the design model, the binder interacts with the central loop II of the neurotoxin, which is crucial for interaction of the toxin with muscle-type and neuronal α7 nAChRs44,45. This interaction is primarily mediated by backbone hydrogen bonding between a β strand in the designed binder and a β strand in the toxin (Fig. 3b). An arginine residue at position 33, located at the tip of loop II of α-cobratoxin, makes extensive electrostatic interactions with the binder (Fig 3b, left inset).

Design of cytotoxin binding proteins

Cytotoxins, a prominent functional group within the 3FTx family found in cobra venoms, exert cytotoxic effects and induce local tissue damage by destabilizing phospholipid membranes46 (Figure 1b). Neutralizing these toxins is crucial to prevent severe sequelae, such as limb deformity, amputation, and lasting disabilities in snakebite victims47.

For targeting cytotoxins, we hypothesized that relying solely on β-strand pairing interactions might not adequately prevent cytotoxin insertion into membranes due to the critical role of their three-finger loops in membrane interaction and disruption48,49,50,51 (Figure 1d). Instead, we focused on binding directly to the cytotoxin three-finger loops by generating RFdiffusion-based protein backbones with hotspot residues defined within these regions (Figure 2a, bottom row). To increase the breadth of neutralization, we targeted a consensus sequence derived from 86 different snake cytotoxins (Type IA cytotoxin sub-subfamily; see Methods). Following ProteinMPNN and AF2 screening, partial diffusion was used to further optimize designs with the best metrics. A total of 55 protein designs were recombinantly expressed using Escherichia coli, and following SEC purification, the 18 designs with monomeric populations were tested in a luminescent cell viability assay. Of these, one protein binder (CYTX) had high solubility, with a single monomeric peak in SEC and had high neutralization activity against Naja pallida and Naja nigricollis whole venoms, known for their high cytotoxin content52 (Supplementary Figure S5). The Kd for the cytotoxin from Naja pallida was determined to be 271 nM via SPR (Figure 2c, bottom row). CYTX exhibited characteristic αβ-protein CD spectrum and was thermostable, with a Tm of 61°C (Figure 2d, bottom row).

Few designed binders have targeted loops, and hence we sought to solve the crystal structure of CYTX in complex with Naja pallida cytotoxin (Fig 3c). To reduce flexibility to favor crystallization, a disulfide bond was introduced within a flexible loop connecting the β-sheet segment to the two α-helices of CYTX, yielding a candidate (CYTX_B10) with improved thermal stability (Tm= 70.3°C) and monomeric profile during SEC, but a slightly weaker Kd of 740 nM for Naja pallida cytotoxin (Supplementary Fig.S6). The structure of CYTX_B10 in complex with the target closely matched the computational design model (resolution: 2.0 Å; RMSD: 1.32 Å over design, 0.58 Å over toxin), revealing extensive electrostatic interactions involving side chain–main chain hydrogen bonds between cytotoxin loops II and III and the CYTX_B10 binder (Figure 3c, left inset). The unusual open fold of CYTX_B10 highlights the power of RFdiffusion to custom generate scaffolds shape-matched with protein targets, and the power of proteinMPNN to stabilize structures which violate common rules of protein structure (in this case lacking a central hydrophobic core).

In vitro neutralization

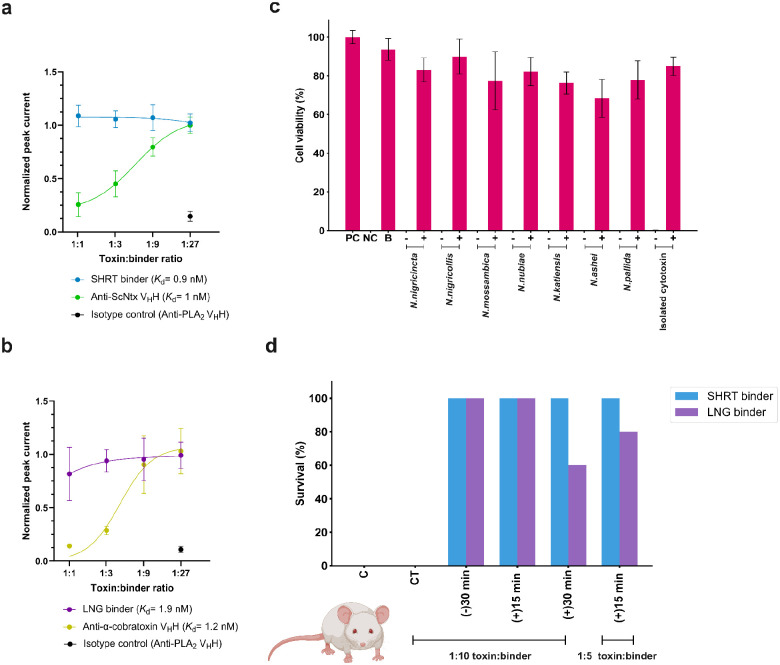

We assessed the ability of the designs to functionally neutralize α-neurotoxins in patch-clamp experiments using a human-derived rhabdomyosarcoma cell line expressing muscle-type nAChRs. When preincubated with ScNtx, the SHRT design achieved complete neutralization at a 1:1 molar ratio (toxin:binder), better than a previously characterized ScNtx nanobody (TPL1163_02_A01)53 (Figure 4a; a control nanobody targeting phospholipase A2 (PLA2) had no effect). Similarly, the LNG design had better neutralizing efficacy than a previously characterized α-cobratoxin nanobody (TPL1158_01_C09)53, achieving full protection at a 1:1 molar ratio (toxin:binder) (Figure 4b).

Figure 4. In vitro and in vivo efficacy of designed proteins against snake venom toxins.

(a) Concentration-response curves comparing SHRT binder and anti-ScNtx VHH efficacy in preventing nAChR blocking by 1 IC80 of ScNtx. Data represent the toxin’s inhibition of ACh response, normalized to full ACh response, averaged within each group (n=16). (b) Concentration-response curves comparing the efficacy of LNG binder and anti-α-cobratoxin VHH in preventing nAChR blocking by 1 IC80 of α-cobratoxin. (c) Neutralization of the cytolytic effects of whole venoms from seven different Naja (N.) species and isolated cytotoxin by the CYTX binder. 2 IC50 of the whole venoms or toxin were pre-incubated with CYTX at a 1:5 molar ratio (toxin:binder). Keratinocyte media was used as a positive control (PC). Triton X-100 was used as a negative control (NC). CYTX binder (B) was used as a positive control. (−) denotes 2 IC50 of the whole venoms without binder, and (+) denotes venoms incubated with binder. Experiments were performed in triplicates, and results are expressed as mean ± SD. (d) Mice survival following lethal neurotoxin challenge (n=5). 3 LD50s of ScNtx or α-cobratoxin were preincubated for 30 minutes (−30 min) with the corresponding protein binders at 1:10 ratios and then administered IP into groups of five mice. Toxins administered IP following IP administration of binders at 1:10 or 1:5 molar ratios (toxin:binder) either after 15 (+15 min) or 30 minutes (+30 min) post-toxin injection. Controls included mice receiving toxins alone (C). Specificity was assessed via cross-treatment (CT) experiments, where non-target binders were preincubated with 3 LD50s of ScNtx or α-cobratoxin and administered IP. Signs of toxicity were observed, and deaths were recorded for a period of 24 hours. (d) was created with BioRender.com.

We used a cytotoxicity assay to evaluate the cross-reactivity of the CYTX design against various cobra whole venoms. Immortalized human keratinocytes (N/TERTs) were exposed to venoms from seven different Naja (N.) species, which prior proteomic analyses suggest consist primarily (~70%) of cytotoxins54. Pre-incubating CYTX with venoms (2 IC50s) at a 1:5 molar ratio (toxin:binder) provided 70–90% protection against venom-induced cytotoxicity (Figure 4c). Similarly, pre-incubation of the cytotoxin binder with isolated cytotoxin from N. pallida (2 IC50s) at a 1:5 molar ratio (toxin:binder) gave 85% protection against cytotoxicity (Figure 4c). However, preliminary studies indicated that the CYTX design, in 1:1, 1:2.5, and 1:5 molar ratios (toxin:binder), did not significantly decrease the size of the dermonecrotic lesions induced by intradermal N. nigricollis venom administration in a murine model55 (Supplementary Fig.S7); the affinity of CYTX likely needs to be further optimized for full in vivo neutralization of cytotoxins.

In vivo protection

Given the encouraging in vitro neutralization for our anti-neurotoxin designs, we proceeded to in vivo studies. We determined the mean lethal dose (LD50) values for α-neurotoxins in male non-Swiss albino (NSA) mice via intraperitoneal (IP) administration; α-cobratoxin had an LD50 of 0.098 μg/g and ScNtx had an LD50 of 0.087 μg/g, in agreement with prior intravenous LD50s doses of these toxins (0.1 μg/g)56. We evaluated the in vivo neutralizing capacity of our neurotoxin-targeting protein binders by assessing survival over a 24-hour period following lethal neurotoxin challenge (3 LD50s) (Figure 4d). The SHRT binder provided complete protection (100%) to mice when pre-incubated and administered intraperitoneally with the corresponding short-chain neurotoxin at a 1:10 molar ratio of toxin to binder, but as expected did not neutralize the non-target α-cobratoxin. The LNG binder exhibited comparable efficacy, completely neutralizing α-cobratoxin but not the non-target ScNtx (Figure 4d, left). In rescue assays better mimicking a real-life snakebite scenario, complete protection (100%) was achieved when short-chain or long-chain α-neurotoxin binders were administered intraperitoneally at a 1:10 molar ratio (toxin:binder) 15 minutes after a lethal α-neurotoxin challenge (3 LD50s) (Figure 4d, middle). Administering the SHRT binder 30 minutes post-toxin injection also provided 100% protection against ScNtx, while the LNG binder conferred 60% protection against α-cobratoxin (Figure 4d, right). All surviving mice showed no evidence of limb or respiratory paralysis. At a 1:5 molar ratio (toxin:binder), IP administration of the SHRT design 15 minutes after toxin injection (3 LD50s) resulted in 100% survival, while the LNG binder provided 80% protection. Mice injected with the binder alone showed no negative effects at 24 and 48 hours post-injection, nor up to two weeks post-injection.

DISCUSSION

Antivenoms based on animal-derived polyclonal antibodies have long been the cornerstone of snakebite envenoming therapy, but their application is hampered by their limited efficacy against toxins with low immunogenicity, their propensity to cause severe adverse reactions, and the inherent batch-to-batch variations and high production costs associated with their manufacture57. Thus, there has been a search for alternatives, with recombinant human monoclonal antibodies and nanobodies presenting a solution that can help overcome some of these limitations58. Our designed neurotoxin binders demonstrate comparable potency to the best immunoglobulin G antibodies and nanobodies reported in literature58, are highly stable and readily producible in microbial systems, and their small size (~100 amino acids) may possibly enable them to penetrate rapidly into deep tissue34. More generally, our in silico design approach avoids animal immunization and/or construction and multiple rounds of selection and/or screening of large libraries, providing a low-cost methodology for rapid development of toxin binders to the many components of snake venom when structural or sequence data exists for these targets. De novo designed proteins have high stability and are amenable to low cost manufacturing, which is key to effectively addressing snakebite envenoming as a neglected tropical disease. From the design perspective, the crystal structure of our cytotoxin binder highlights the ability of RFdiffusion to custom design scaffolds to match almost any target shape, and to generate binders to loop regions of proteins, with the inhibitory activity of the anti-cytotoxin designs directly supporting a role for the loops in membrane disruption.

Advancing the field to provide effective solutions for snakebite victims requires a collaborative effort involving the scientific community, the pharmaceutical industry, public health systems, and governments2. While traditional antivenoms will likely remain a therapeutic cornerstone in snakebite treatment for the immediate future, our de novo designed binders could potentially be used as fortifying agents to improve the efficacy of antivenoms; this would be particularly beneficial in the treatment of elapid envenomings, where low-molecular mass toxins with limited immunogenicity, but high medical importance, dominate the toxic effects of the venoms (and therefore must be neutralized)59. Beyond fortification, generative binder design could be used to generate neutralizing proteins against other medically relevant toxins, thereby expediting the discovery of antivenoms with broader species coverage. More generally, as in silico protein design is less resource intensive than traditional antibody development, our approach could aid in the democratization of drug design and discovery, enabling researchers residing in low and middle-income countries to better contribute to the development of effective treatments for snakebite envenoming and other neglected tropical diseases.

METHODS

Cytotoxin consensus sequence design

Amino acid sequences for cytotoxins were collected from the UniProt website using family:”snake three-finger toxin family Short-chain subfamily Type IA cytotoxin sub-subfamily” as a query. The resultant 86 unique CTX sequences thereafter underwent multiple sequence alignment (MSA) in Clustal Omega1. Using these alignments a consensus sequence was designed to represent the most common amino acids at each position across the aligned sequences. In this process, each column of the sequence alignment was analyzed to select the most frequent amino acid. In scenarios where no single amino acid dominated, a consensus symbol was used to represent a group of similar amino acids based on properties like charge or hydrophobicity. This approach allowed for the representation of conserved biochemical properties rather than specific amino acid identities at positions with high variability.

Secondary structure and block adjacency tensors

In order to generate desired binder-target β-strand pairing interactions using RFdiffusion, fold-conditioning tensors describing single binder β-strands interacting with target β-strands in a matrix format were supplied to RFdiffusion at inference. This information is supplied via two tensors: a [L,4] secondary one-hot tensor (0=α-helix, 1=β-strand, 2=loop, 3=masked secondary structure identity) to indicate the secondary structure classification of each residue in the binder-target complex, and an [L,L,3] adjacency one-hot tensor (0=non-adjacent, 1=adjacent, 2=masked adjacency) to indicate interacting partner residues for each residue in the binder-target complex. For the design of the binders described here, the secondary structure tensor indicated an entirely masked binder structure with the exception of binder residues set to β-strand identities, while the adjacency tensor indicated a masked adjacency between binder-target residues with the exception of the pre-defined strand residues being adjacent to the defined target strand residues.

De novo 3FTX binder design using RFdiffusion

The crystal structures of ScNtx (PDB ID: 7Z14) and α-cobratoxin (PDB ID: 1YI5) served as input for RFdiffusion. In the case of the consensus cytotoxin, its AF2 model was utilized. A total of approximately two thousand diffused designs were generated for each target, employing secondary structure and block adjacency tensors in the RFdiffusion model. The resulting backbone libraries underwent sequence design using ProteinMPNN, followed by FastRelax and AF2 + initial guess2. The resulting libraries were filtered based on AF2 PAE <10, pLDDT > 80, and Rosetta ddg < −40.

Partial diffusion to optimize binders

The AF2 models of the highest-affinity designs for each toxin target were used as inputs to partial diffusion. The models were subjected to 10 and 20 noising timesteps out of a total of 50 timesteps in the noising schedule, and subsequently denoised (“diffuser.partial_T” input values of 10 and 20). Approximately two thousand partially diffused designs were generated for each target. The resulting library of backbones were sequence designed using ProteinMPNN after Rosetta FastRelax, followed by AF2+initial guess2. The resulting libraries were filtered based on AF2 PAE <10, pLDDT > 80, and Rosetta ddg < −40.

Recombinant expression of ScNtx

ScNtx was recombinantly expressed from the methylotrophic yeast Komagataella phaffii (formerly known as Pichia pastoris). The ScNtx sequence was codon-optimized for expression in yeast and included a N-terminal His6 tag, followed by a Biotin Acceptor Peptide, and a Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) proteolytic site. The expression was performed as previously described3. The culture media was dialyzed overnight against a wash buffer (50 mM Sodium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0, 20 mM imidazole). Purification was carried out using an NGC™ chromatography system (Bio-Rad) with a 5 mL IMAC Nickel column (Bio-Rad). After loading, the column was washed with 5 column volumes of wash buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins. The protein was then eluted using a gradient of 250 mM imidazole over 10 column volumes. Fractions with high absorbance at 280 nm were pooled, dialyzed against 50 mM Sodium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0. Purity was assessed on SDS-PAGE to confirm the size. The protein solution was aliquoted, and stored at −20°C for further use.

Toxins

α-cobratoxin (L8114) was obtained from Latoxan (Portes lés Valence, France). Cytotoxin from Naja pallida was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (217503).

Venoms

Whole venoms for initial neutralization screening from Naja nigricollis (CV01089563VEN) and Naja pallida (CV01089566VEN) were obtained in lyophilized form from Amerigo Scientific. Catalog numbers are provided in parentheses.

For in vitro neutralization experiments in human keratinocytes, whole venoms from Naja nigricollis (L1327), Naja nigricincta (L1368), Naja mossambica (L1376), Naja nubiae (L1342), Naja katiensis (L1317), Naja ashei (L1375), and Naja pallida (L1321) were purchased in lyophilized form from Latoxan (Portes lés Valence, France). Catalog numbers are provided in parentheses.

For the anti-cytotoxin in vivo study, Naja nigricollis venom was sourced from wild-caught Tanzanian specimens housed in the herpetarium of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

Gene construction of 3FTX binders

The designed protein sequences were optimized for expression in E. coli. Linear DNA fragments (eBlocks, Integrated DNA Technologies) encoding the design sequences contained overhangs suitable to cloning into the pETcon3 vector for yeast display (deposited in Addgene as #45121) and LM627 vector for protein expression (Addgene #191551) via Golden Gate cloning.

Yeast display screening

For the yeast transformation, 50–60 ng of pETcon3, digested with NdeI and XhoI restriction enzymes, and 100 ng of the insert (eBlocks, Integrated DNA Technologies) were transformed into S. cerevisiae EBY100 following the protocol in4. EBY100 cultures were cultivated in C-Trp-Ura medium with 2% (w/v) glucose (CTUG). To induce expression, yeast cells initially grown in CTUG were transferred to SGCAA medium with 0.2% (w/v) glucose and induced at 30 °C for 16–24 h. After induction, cells were washed with PBSF (PBS with 1% (w/v) BSA) and labeled for 40 minutes with biotinylated toxin targets at room temperature using the without-avidity labeling condition4. Subsequently, cells were washed, resuspended in PBSF, and individually sorted based on each unique design using a 96-well compatible autosampler in the Attune NxT Flow Cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Protein expression and purification in E. coli for 3FTX binders

Protein expression was conducted in 50 mL of Studier autoinduction media supplemented with kanamycin, and cultures were grown overnight at 37°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min and resuspended in lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 50 mM imidazole) supplemented with Pierce™ Protease Inhibitor Tablets (EDTA-free). Cell lysis was achieved by sonication using a Qsonica Q500 instrument with a 4-pronged horn for 2:30 min ON total, at an amplitude of 80%. Soluble fractions were clarified by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 40 minutes and subsequently purified by affinity chromatography using Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen) on a vacuum manifold. Washes were performed using Low-salt buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 50 mM imidazole) and High-salt buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 1000 mM NaCl, 50 mM imidazole) before elution with Elution buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole). Eluted protein samples were filtered and injected into an autosampler-equipped Akta pure system on a Superdex S75 Increase 10/300 GL column at room temperature, using SEC running buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, pH 8). Monodisperse peak fractions were pooled, concentrated using Spin filters (3 kDa molecular weight cutoff, Amicon, Millipore Sigma), and stored at 4°C before downstream characterizations. Protein concentrations were determined by absorbance at 280 nm using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) using the molecular weights and extinction coefficients obtained from their amino acid sequences using the ProtParam tool.

Bio-layer Inferometry (BLI) Binding Experiments

BLI experiments were performed on an Octet Red96 (ForteBio) instrument, with streptavidin coated tips (Sartorius Item no. 18–5019). Buffer comprised 1X HBS-EP+ buffer (Cytiva BR100669) supplemented with 0.1% w/v bovine serum albumin. Tips were pre-incubated in the buffer for at least 10 minutes before use. Tips were then sequentially incubated in biotinylated toxin target, buffer, designed binder, and buffer.

Affinity measurements by surface plasmon resonance (SPR)

SPR experiments were conducted using a Biacore™ 8K instrument (Cytiva) and analyzed with the accompanying evaluation software. Biotinylated α-cobratoxin was immobilized on a streptavidin sensor chip (Cytiva). For ScNtx and Naja pallida’s cytotoxin, immobilization involved the activation of carboxymethyl groups on a dextran-coated chip through reaction with N-hydroxysuccinimide. The ligands were then covalently bonded to the chip surface via amide linkages, and excess activated carboxyls were blocked with ethanolamine (doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-523-7_20). Increasing concentrations of protein binders were flown over the chip in 1X HBS-EP+ buffer (Cytiva BR100669).

Circular dichroism (CD)

Secondary structure content was evaluated by CD in a Jasco J-1500 CD spectrometer coupled to a Peltier system (EXOS) for temperature control. The experiments were performed on quartz cells with an optical path of 0.1 cm, covering a wavelength range from 200–260 nm. CD signal is reported as molar ellipticity [θ]. The thermal unfolding experiments were followed by a change in the ellipticity signal at 222 nm as a function of temperature. Proteins were denatured by heating the proteins at 1°C/min from 20 to 95°C.

Crystallization and Structure Determination

Crystallization experiments for the binder complex were conducted using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method. Crystallization trials were setup in 200 nL drops using 96-well format by Mosquito LCP from SPT Labtech. Crystals drops were imaged using the UVEX crystal plate hotel system by JANSi. Diffraction quality crystals for LNG binder-complex appeared in 1.5 M Ammonium Sulfate and 25% (v/v) glycerol in 2 weeks. Diffraction quality crystals for SHRT binder appeared in 0.08 M Sodium acetate trihydrate pH 4.6, 1.6 M Ammonium sulfate and 20% (v/v) glycerol. For CYTX_B10-complex diffraction quality crystals appeared in 0.1 M MES pH 6, 0.01 M Zinc chloride, 20% (w/v) PEG 6000 and 10 % (v/v) Ethylene glycol. Crystals were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen before shipping to the synchrotron for diffraction experiment.

Diffraction data were collected at the NSLS2 beamline AMX (17-ID-1). X-ray intensities and data reduction were evaluated and integrated by XDS5 and merged/scaled by Pointless/Aimless in the CCP4i2 program suite6. Structure determined by molecular replacement using a designed model using Phaser7. Following molecular replacement model was improved and refined by Phenix8. Model building was performed by COOT9 in between refinement cycles. Final model was evaluated by MolProbity10. Data collection and refinement statistics were reported in the Supplementary Table X. Final atomic coordinates, mmCIF and structure factors were deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with accession codes 9BK5, 9BK6 and 9BK7.

In vitro neutralization using electrophysiology

Human-derived Rhabdomyosarcoma RD cells (American Type Culture Collection, ATCC), endogenously expressing the muscle-type nAChR were used for electrophysiology experiments11. Planar whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were conducted on a QUBE automated electrophysiology platform (Sophion Bioscience), with 384-channel patch chips (patch hole resistance 2.00 ± 0.02 MΩ), following the protocol detailed in11. Protein binders were preincubated with approximately 1 IC80 of α-cobratoxin or ScNtx at various toxin to binder molar ratios (1:1, 1:3, 1:9, and 1:27) and then added to the cells. The toxin’s ability to inhibit an acetylcholine (ACh, 70 μM) response, in the presence or absence of binders was normalized to the full ACh response and averaged within each group (n=16), and represented in a non-cumulative concentration-response plot. Data analysis was performed using Sophion Analyzer v6.6.70 (Sophion Bioscience) and GraphPad Prism v10.1.1 (GraphPad Software).Data analysis was performed using Sophion Analyzer v6.6.70 (Sophion Bioscience) and GraphPad Prism v10.1.1 (GraphPad Software).

Initial neutralization screening of whole venoms using cell viability assay

HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium, Gibco) medium with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C and 5% and CO2. Cells were subjected to commercial whole venoms from Naja pallida (34 μg/mL) and Naja nigricollis (42 μg/mL) either in the absence or presence of 1:1 or 5:1 molar ratio of toxin:binder. Buffer and binder-only controls were run in parallel and all samples were pre-incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature before addition to the HEK293T cells. To determine the percentage of viable cells, the RealTime-Glo™ MT Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Experiments were performed in triplicates, and results were expressed as mean ± SD.

In vitro neutralization of whole venoms using cell viability assay

N/TERT immortalized keratinocytes were cultured as previously described12. After determining the IC50 for seven venoms of Afronaja snakes, N/TERT cells were subjected to 2X the IC50 of each venom either in the absence or presence of a 1:5 molar ratio of venom:binder. Buffer and binder-only controls were run in parallel and all samples were pre-incubated (30 min at 37 °C) before addition to the N/TERT cells. To determine the percentage of viable cells, the CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Experiments were performed in triplicates, and results were expressed as mean ± SD.

LD50 determinations for α-neurotoxins

All assays used male NSA mice (20–30 g) and all doses were mass adjusted. Toxins assayed were α-cobratoxin (7820 Da, from Naja kaouthia venom obtained from Latoxan SAS, France) and short-chain neurotoxin ScNtx (8944 Da, recombinantly expressed). Toxins were solubilized in PBS at 1.0 mg/mL and then diluted in PBS as needed. For toxin LD50 determinations, five doses with 3 mice/dose were used, and a 100 μL bolus was injected IP in the right lower abdominal region; controls received only PBS. Injected mice were observed for the first 2 hours and then again at 24 hours; LD50 values were calculated using the “Quest Graph™ LD50 Calculator”13 (AAT Bioquest, Inc.; https://www.aatbio.com/tools/ld50-calculator).

In vivo neurotoxicity protein binder protection assays

Toxins were used at 3X the LD50 (α-cobratoxin– 0.294 μg/g mouse; ScNtx – 0.261 μg/g mouse). In pre-incubation experiments, toxins were individually combined with a 10-fold molar excess of each protein binder (designed to bind each toxin specifically) in PBS and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes. Mice (groups of 5) were injected with the binder:toxin protein as indicated above, observed for 2 hours and then again at 24 hours. For rescue-type experiments, toxins were IP administered (3X LD50) either 15 or 30 minutes before corresponding binder administration, either at 10- or 5-fold molar excess. Protection from toxin effects was scored as 24 hour percent mortality.

In vivo dermonecrosis protein binder protection assays

Animal experiments were conducted under protocols approved by the Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Boards of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and the University of Liverpool, and under project licence P58464F90 approved by the UK Home Office in accordance with the UK Animal (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.

CD1 male mice (Charles River, 18–20 g) were acclimated for one week before experimentation in specific pathogen-free conditions. Holding room conditions were 23°C with 45–65% humidity and 12/12 hour light cycles (350 lux). Mice were housed in Techniplast GM500 cages (floor area 501 cm2) containing 120 g Lignocell wood fibre bedding (JRS, Germany), Z-nest biodegradable paper-based material for nesting and environmental enrichment (red house, clear polycarbonate tunnel and loft). Mice had ad lib access to irradiated PicoLab food (Lab Diet, USA) and reverse osmosis water in an automatic water system. Animals were split into cages (experimental units) upon arrival and no further randomisation was performed.

All mice were pre-treated with 5 mg/kg morphine (injected subcutaneously) before receiving intradermal injections in a 100 μL volume into the ventral abdominal region (rear side flank region). A venom-only control group of 5 mice received 63 μg of Naja nigricollis (Tanzania) venom (dissolved in PBS). For protection assays, crude venom was pre-incubated (30 min at 37 °C) with varying cytotoxin:binder ratios of 1:1, 1:2.5 and 1:5 prior to injection (n=3) (ratios estimated from the proportion of cytotoxin in the venom). Prior to this, a control group (N=3) received injections of cytotoxin binder alone (278 μM, equivalent to the 1:5 cytotoxin:binder dose) to check tolerance of the cytotoxin binder. For sample size, N of 3 was used for groups receiving cytotoxin binder as this was a pilot experiment. N of 5 was used for the venom-only control group due to variation in lesion size, and this is the size recommended by WHO. In total 17 mice were used. No inclusion or exclusion criteria were used during the experiment, and all data points were used in the analysis. No strategy was used to control for confounders. All experimenters were aware of the group allocation during the experiment and analysis.

After 72 hours, mice were euthanized by rising concentrations of CO2 and the lesions were excised. The outcome measured was the lesion size. Photographs of lesions were taken using a digital camera immediately after excision and the severity and size of dermonecrotic lesions was determined using VIDAL14.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics.

| LNG binder (holo) (PDB ID: 9BK5) | B10_CYTX binder (holo) (PDB ID: 9BK6) | SHRT_binder (apo) (PDB ID: 9BK7) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution range | 34.06 – 2.68 (2.85 – 2.68) | 33.17 – 2.00 (2.05 – 2.00) | 32.17 – 2.58 (2.84 – 2.58) |

| Space group | I 41 2 2 | P 21 21 21 | I 41 2 2 |

| Unit cell | 77.79, 77.79, 173.52; 90, 90, 90 | 34.56, 63.66, 77.72; 90, 90, 90 | 75.33, 75.33, 108.34; 90, 90, 90 |

| Unique reflections | 9109 (1483) | 12102 (864) | 5179 (1262) |

| Multiplicity | 24.3 (25.8) | 6.4 (6.2) | 24.6 (25.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.86 (99.53) | 99.7 (99.7) | 99.83 (99.92) |

| Mean I/sigma(I) | 17.12 (1.08) | 10.4 (2.6) | 13.30 (4.13) |

| Wilson B-factor | 82.46 | 33.64 | 60.21 |

| R-merge | 0.105 (3.172) | 0.088 (0.599) | 0.246 (1.069) |

| R-pim | 0.022 (0.631) | 0.041 (0.281) | 0.051 (0.215) |

| CC* | 0.999 (0.522) | 0.994 (0.929) | 0.999 (0.982) |

| Reflections used in refinement | 7836 (1264) | 12047 (2928) | 5179 (1262) |

| R-work | 0.2387 (0.3049) | 0.2496 (0.3301) | 0.1970 (0.2954) |

| R-free | 0.2681 (0.3349) | 0.2850 (0.4167) | 0.2235 (0.3560) |

| Number of non-hydrogen atoms | 1118 | 1298 | 739 |

| macromolecules | 1118 | 1241 | 739 |

| solvent | 0 | 57 | 0 |

| Protein residues | 146 | 161 | 102 |

| RMS(bonds) | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.004 |

| RMS(angles) | 0.55 | 0.45 | 0.62 |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 92.25 | 96.82 | 97.00 |

| Ramachandran allowed (%) | 7.75 | 2.55 | 3.00 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0.0 | 0.64 | 0.00 |

| Average B-factor | 101.38 | 48.62 | 67.50 |

| macromolecules | 101.38 | 48.61 | 67.50 |

| solvent | n/a | 48.81 | n/a |

The highest-resolution shell are shown in parentheses.

Acknowledgements

We thank Amijai Saragovi, Fatima A. Davila Hernandez, Ljubica Mihaljević, Yensi Flores Bueso and Kathryn Shelley for helpful discussions on this work. This work was supported with funds provided by the Open Philanthropy Project Improving Protein Design Fund (S.V.T., R.J.R. and D.B.), the Washington State General Operating Fund supporting the Institute for Protein Design (I.S.), the Audacious Project at the Institute for Protein Design (A.P., M.A., H.L.H., and D.B.), and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (D.B.). E.M. was supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation (GR032004). T.P.J. acknowledges support from the Alliance programme under the EuroTech Universities agreement. M.B.V. has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 899987. N.R.C. acknowledges support from Wellcome Trust grants 221708/Z/20/Z and 223619/Z/21/Z. S.P.M. acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation grant 2307044. This research was funded in part by the Wellcome Trust. For the purpose of open access, the authors have applied a CC BY public copyright license to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission. The authors acknowledge use of the Biomedical Services Unit provided by Liverpool Shared Research Facilities, Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, University of Liverpool. We are grateful to Paul Rowley (LSTM) for the care of, and venom extraction from, some of the snakes used in this study. Crystallographic data collected at the National Synchrotron Light Source II beamline AMX (17-ID-1). The Center for Bio-Molecular Structure (CBMS) is primarily supported by the NIH-NIGMS through a Center Core P30 Grant (P30GM133893), and by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research (KP1607011). NSLS2 is a U.S.DOE Office of Science User Facility operated under Contract No. DE-SC0012704. This publication resulted from the data collected using the beamtime obtained through NECAT BAG proposal # 311950. A.H.L. is supported by a grant from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program [850974] and a grant from Wellcome [221702/Z/20/Z].

Footnotes

Supplementary Files

References

- 1.GBD 2019 Snakebite Envenomation Collaborators et al. Global mortality of snakebite envenoming between 1990 and 2019. Nat. Commun. 13, 6160 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gutiérrez J. M. et al. Snakebite envenoming. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 3, 17063 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Royte L. & Sawarkar A. Snake bite - cytotoxic effects of snake venom: a rare clinical image. Pan Afr. Med. J. 44, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barber C. M., Isbister G. K. & Hodgson W. C. Alpha neurotoxins. Toxicon 66, 47–58 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deka A., Gogoi A., Das D., Purkayastha J. & Doley R. Proteomics of Naja kaouthia venom from North East India and assessment of Indian polyvalent antivenom by third generation antivenomics. J. Proteomics 207, 103463 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laustsen A. H. et al. Snake venomics of monocled cobra (Naja kaouthia) and investigation of human IgG response against venom toxins. Toxicon 99, 23–35 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan K. Y., Tan C. H., Fung S. Y. & Tan N. H. Venomics, lethality and neutralization of Naja kaouthia (monocled cobra) venoms from three different geographical regions of Southeast Asia. J. Proteomics 120, 105–125 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chippaux J.-P. Snakebite envenomation turns again into a neglected tropical disease! J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Trop. Dis. 23, 38 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamza M. et al. Clinical management of snakebite envenoming: Future perspectives. Toxicon X 11, 100079 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone S. F. et al. Immune Response to Snake Envenoming and Treatment with Antivenom; Complement Activation, Cytokine Production and Mast Cell Degranulation. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7, e2326 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warrell D. A. & Williams D. J. Clinical aspects of snakebite envenoming and its treatment in low-resource settings. The Lancet 401, 1382–1398 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thumtecho S., Burlet N. J., Ljungars A. & Laustsen A. H. Towards better antivenoms: navigating the road to new types of snakebite envenoming therapies. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Trop. Dis. 29, e20230057 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silva A., Hodgson W. & Isbister G. Antivenom for Neuromuscular Paralysis Resulting From Snake Envenoming. Toxins 9, 143 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khalek I. S. et al. Synthetic development of a broadly neutralizing antibody against snake venom long-chain α-neurotoxins. Sci. Transl. Med. 16, eadk1867 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laustsen A. H. et al. In Vivo Neutralization of Myotoxin II, a Phospholipase A 2 Homologue from Bothrops asper Venom, Using Peptides Discovered via Phage Display Technology. ACS Omega 7, 15561–15569 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sørensen C. V. et al. Antibody-dependent enhancement of toxicity of myotoxin II from Bothrops asper. Nat. Commun. 15, 173 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bailon Calderon H. et al. Development of Nanobodies Against Hemorrhagic and Myotoxic Components of Bothrops atrox Snake Venom. Front. Immunol. 11, 655 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wade J. et al. Generation of Multivalent Nanobody-Based Proteins with Improved Neutralization of Long α-Neurotoxins from Elapid Snakes. Bioconjug. Chem. 33, 1494–1504 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tulika T. et al. Phage display assisted discovery of a pH -dependent anti-α-cobratoxin antibody from a natural variable domain library. Protein Sci. 32, e4821 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laustsen A. H. et al. In vivo neutralization of dendrotoxin-mediated neurotoxicity of black mamba venom by oligoclonal human IgG antibodies. Nat. Commun. 9, 3928 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ledsgaard L. et al. Discovery and optimization of a broadly-neutralizing human monoclonal antibody against long-chain α-neurotoxins from snakes. Nat. Commun. 14, 682 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glanville J. et al. Venom protection by broadly neutralizing antibody from a snakebite subject. Preprint at 10.1101/2022.09.26.507364 (2022). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alomran N., Chinnappan R., Alsolaiss J., Casewell N. R. & Zourob M. Exploring the Utility of ssDNA Aptamers Directed against Snake Venom Toxins as New Therapeutics for Snakebite Envenoming. Toxins 14, 469 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anand A. et al. Complex target SELEX-based identification of DNA aptamers against Bungarus caeruleus venom for the detection of envenomation using a paper-based device. Biosens. Bioelectron. 193, 113523 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y.-J., Tsai C.-Y., Hu W.-P. & Chang L.-S. DNA Aptamers against Taiwan Banded Krait α-Bungarotoxin Recognize Taiwan Cobra Cardiotoxins. Toxins 8, 66 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruno J. G., Phillips T. & Montez T. Preliminary Development of DNA Aptamers to Inhibit Phospholipase A2 Activity of Bee and Cobra Venoms. J. Bionanoscience 9, 270–275 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Savchik E. Yu. et al. Aptamer RA36 Inhibits of Human, Rabbit, and Rat Plasma Coagulation Activated with Thrombin or Snake Venom Coagulases. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 156, 44–48 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dhiman A. et al. Rational truncation of aptamer for cross-species application to detect krait envenomation. Sci. Rep. 8, 17795 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jenkins T. et al. Toxin Neutralization Using Alternative Binding Proteins. Toxins 11, 53 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romanovskis P., Rosenberry T. L., Cusack B. & Spatola A. F. By-Product Formation During SPPS of Linear, Cyclic, and Novel Bicyclic Peptides as AChE Inhibitors. in Peptides: The Wave of the Future (eds. Lebl M. & Houghten R. A.) 85–86 (Springer; Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2001). doi: 10.1007/978-94-010-0464-0_36. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laustsen A. H., Greiff V., Karatt-Vellatt A., Muyldermans S. & Jenkins T. P. Animal Immunization, in Vitro Display Technologies, and Machine Learning for Antibody Discovery. Trends Biotechnol. 39, 1263–1273 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Damsbo A. et al. A comparative study of the performance of E. coli and K. phaffii for expressing α-cobratoxin. Toxicon 239, 107613 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rivera-de-Torre E. et al. Strategies for Heterologous Expression, Synthesis, and Purification of Animal Venom Toxins. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9, 811905 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nessler I. et al. Increased Tumor Penetration of Single-Domain Antibody–Drug Conjugates Improves In Vivo Efficacy in Prostate Cancer Models. Cancer Res. 80, 1268–1278 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watson J. L. et al. De novo design of protein structure and function with RFdiffusion. Nature 620, 1089–1100 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laustsen A. H. et al. Pros and cons of different therapeutic antibody formats for recombinant antivenom development. Toxicon 146, 151–175 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Utkin Y. N. Last decade update for three-finger toxins: Newly emerging structures and biological activities. World J. Biol. Chem. 10, 17–27 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalogeropoulos K. et al. A comparative study of protein structure prediction tools for challenging targets: Snake venom toxins. Toxicon 238, 107559 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nys M. et al. The molecular mechanism of snake short-chain α-neurotoxin binding to muscle-type nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Nat. Commun. 13, 4543 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bennett N. R. et al. Improving de novo protein binder design with deep learning. Nat. Commun. 14, 2625 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De La Rosa G., Corrales-García L. L., Rodriguez-Ruiz X., López-Vera E. & Corzo G. Short-chain consensus alpha-neurotoxin: a synthetic 60-mer peptide with generic traits and enhanced immunogenic properties. Amino Acids 50, 885–895 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vázquez Torres S. et al. De novo design of high-affinity binders of bioactive helical peptides. Nature 626, 435–442 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miersch S. et al. Synthetic antibodies block receptor binding and current-inhibiting effects of α-cobratoxin from Naja kaouthia. Protein Sci. 31, e4296 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bekbossynova A., Zharylgap A. & Filchakova O. Venom-Derived Neurotoxins Targeting Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Molecules 26, 3373 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Antil-Delbeke S. et al. Molecular Determinants by Which a Long Chain Toxin from Snake Venom Interacts with the Neuronal α7-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 29594–29601 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hiu J. J. & Yap M. K. K. The myth of cobra venom cytotoxin: More than just direct cytolytic actions. Toxicon X 14, 100123 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chong H. P., Tan K. Y., Liu B.-S., Sung W.-C. & Tan C. H. Cytotoxicity of Venoms and Cytotoxins from Asiatic Cobras (Naja kaouthia, Naja sumatrana, Naja atra) and Neutralization by Antivenoms from Thailand, Vietnam, and Taiwan. Toxins 14, 334 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hiu J. J., Fung J. K. Y., Tan H. S. & Yap M. K. K. Unveiling the functional epitopes of cobra venom cytotoxin by immunoinformatics and epitope-omic analyses. Sci. Rep. 13, 12271 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dubovskii P. V., Lesovoy D. M., Dubinnyi M. A., Utkin Y. N. & Arseniev A. S. Interaction of the P‐type cardiotoxin with phospholipid membranes. Eur. J. Biochem. 270, 2038–2046 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li F., Shrivastava I. H., Hanlon P., Dagda R. K. & Gasanoff E. S. Molecular Mechanism by Which Cobra Venom Cardiotoxins Interact with the Outer Mitochondrial Membrane. Toxins 12, 425 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.G. Konshina A., V. Dubovskii P. & G. Efremov R. Structure and Dynamics of Cardiotoxins. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 13, 570–584 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kazandjian T. D. et al. Convergent evolution of pain-inducing defensive venom components in spitting cobras. Science 371, 386–390 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jensen Anna. Design of Consensus Toxins and Their Use for the Discovery of Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies.

- 54.Petras D. et al. Snake Venomics of African Spitting Cobras: Toxin Composition and Assessment of Congeneric Cross-Reactivity of the Pan-African EchiTAb-Plus-ICP Antivenom by Antivenomics and Neutralization Approaches. J. Proteome Res. 10, 1266–1280 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bartlett K. E. et al. Dermonecrosis caused by spitting cobra snakebite results from toxin potentiation and is prevented by the repurposed drug varespladib. Preprint at 10.1101/2023.07.20.549878 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Modahl C. M., Mukherjee A. K. & Mackessy S. P. An analysis of venom ontogeny and prey-specific toxicity in the Monocled Cobra (Naja kaouthia). Toxicon 119, 8–20 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jenkins T. P. & Laustsen A. H. Cost of Manufacturing for Recombinant Snakebite Antivenoms. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 703 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Laustsen A. H. Recombinant snake antivenoms get closer to the clinic. Trends Immunol. 45, 225–227 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laustsen A. H., Lohse B., Lomonte B., Engmark M. & Gutiérrez J. M. Selecting key toxins for focused development of elapid snake antivenoms and inhibitors guided by a Toxicity Score. Toxicon 104, 43–45 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nastopoulos V., Kanellopoulos P. N. & Tsernoglou D. Structure of Dimeric and Monomeric Erabutoxin a Refined at 1.5 Å Resolution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54, 964–974 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dubovskii P. V. et al. Impact of membrane partitioning on the spatial structure of an S-type cobra cytotoxin. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 36, 3463–3478 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Olsen J. A., Balle T., Gajhede M., Ahring P. K. & Kastrup J. S. Molecular Recognition of the Neurotransmitter Acetylcholine by an Acetylcholine Binding Protein Reveals Determinants of Binding to Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. PLoS ONE 9, e91232 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bourne Y., Talley T. T., Hansen S. B., Taylor P. & Marchot P. Crystal structure of a Cbtx–AChBP complex reveals essential interactions between snake α-neurotoxins and nicotinic receptors. EMBO J. 24, 1512–1522 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 1.Sievers F. et al. Fast, scalable generation of high‐quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 539 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett N. R. et al. Improving de novo protein binder design with deep learning. Nat. Commun. 14, 2625 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damsbo A. et al. A comparative study of the performance of E. coli and K. phaffii for expressing α-cobratoxin. Toxicon 239, 107613 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao L. et al. Design of protein-binding proteins from the target structure alone. Nature 605, 551–560 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winn M. D. et al. Overview of the CCP 4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 235–242 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCoy A. J. et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams P. D. et al. PHENIX : a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emsley P. & Cowtan K. Coot : model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams C. J. et al. MolProbity: More and better reference data for improved all‐atom structure validation. Protein Sci. 27, 293–315 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ledsgaard L. et al. Discovery and optimization of a broadly-neutralizing human monoclonal antibody against long-chain α-neurotoxins from snakes. Nat. Commun. 14, 682 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pucca M. B. et al. Unity Makes Strength: Exploring Intraspecies and Interspecies Toxin Synergism between Phospholipases A2 and Cytotoxins. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 611 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.AAT Bioquest, Inc. Quest Graph™ LD50 Calculator.

- 14.Laprade W. et al. Machine-learning guided Venom Induced Dermonecrosis Analysis tooL: VIDAL. Sci. Rep. 13, 21662 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]